Background: Sickle cell disease is a collection of compound heterozygote hemoglobinopathies, including sickle cell anemia (1). The heterozygote hemoglobinopathies are characterized by erythrocyte deformation with hemolysis; immune and coagulation dysfunction; and chronic complications, including pulmonary hypertension and cardiac failure (1, 2). Sickle cell trait is a carrier status for sickle cell disease. Given the established susceptibility to other viral infections and the ethnic “patterning” of sickle cell disorders, affected persons may have increased risks for severe COVID-19. Evidence about COVID-19 risks in sickle cell disorders mostly derives from studies of hospitalized persons or selective registries (3–5). Robust quantification of risks in sickle cell disorders at a population level may be informative for public health strategies.

Objective: To evaluate the risks for COVID-19–related hospitalization and death in children and adults with sickle cell disorders (disease and trait, separately) using a population-level database of linked electronic health care records.

Methods and Findings: A cohort study of 12.28 million persons aged 0 to 100 years was done using QResearch, a primary care database covering approximately 18% of the English population. The cohort comprised 1317 general practices with individual-level linkage to SARS-CoV-2 test results from Public Health England, hospital admissions data, and the Office for National Statistics death register. Follow-up was from 24 January 2020 to 30 September 2020 (hospitalization) and 18 January 2021 (death). Cause-specific Cox regression models stratified by individual general practice were used to estimate hazard ratios (HRs) with 95% CIs for COVID-19–related hospitalization and COVID-19–related death associated with sickle cell disease (genotypes SC, SD, or SE; sickle cell anemia; thalassemia with hemoglobin S; sickle thalassemia; or not otherwise specified) and sickle cell trait. Models were adjusted for age, sex, and ethnicity. Hospitalization related to COVID-19 was defined as confirmed or suspected COVID-19 as reason for admission (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, code U07.1 or U07.2) or admission within 14 days of a positive SARS-CoV-2 test result. Death related to COVID-19 was defined as confirmed or suspected COVID-19 on the death certificate (International Classification of Diseases, 10th Revision, code U07.1 or U07.2) or death of any cause within 28 days of confirmed SARS-CoV-2 infection. Missing ethnicity data were handled using multiple imputation (10 imputed data sets); the imputation model included end points and all variables in the Table. Analyses used Stata, version 16 (StataCorp).

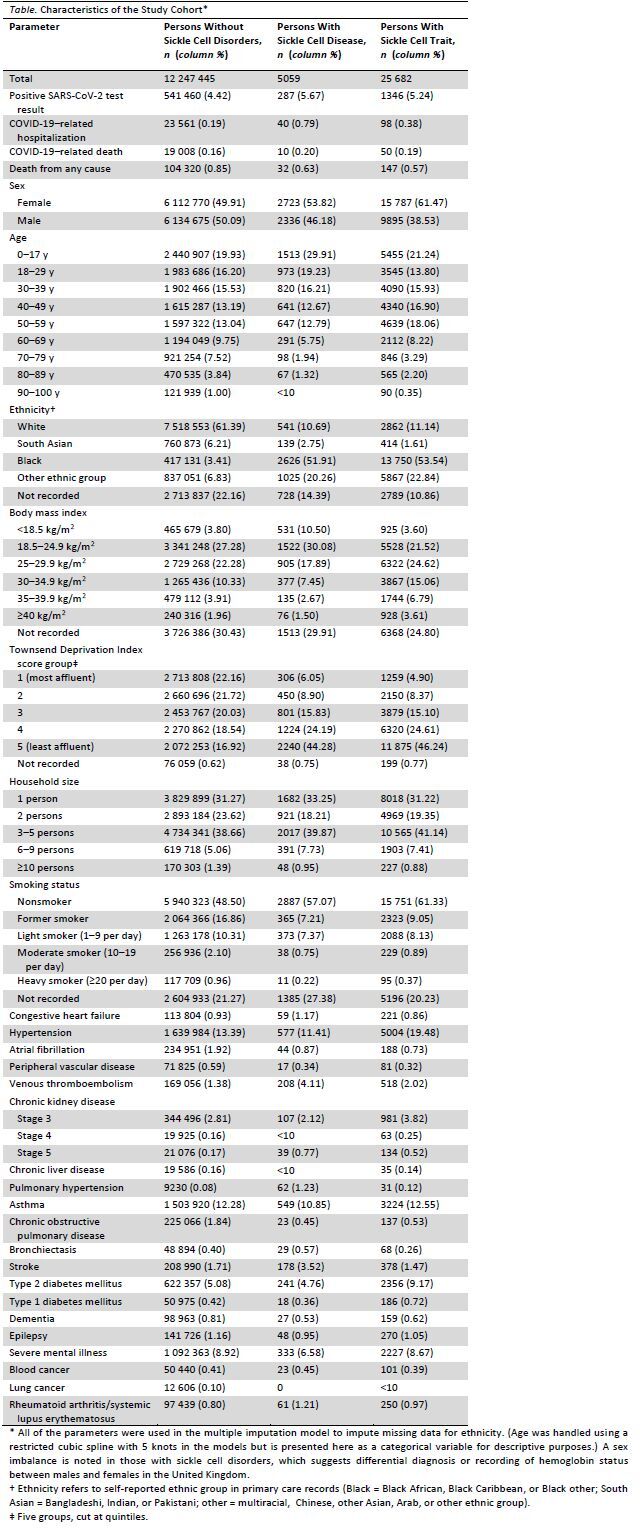

Table.

Characteristics of the Study Cohort

The Table describes the study cohort. There were 5059 (0.04%) persons with sickle cell disease and 25 682 (0.21%) persons with sickle cell trait. During the study, there were 23 699 COVID-19–related hospitalizations, 19 068 COVID-19–related deaths, and 104 499 deaths from any cause.

There were fewer than 5 COVID-19–related hospitalizations in children with sickle cell disorders but no COVID-19–related deaths. Adults with sickle cell disease had 40 (0.79%) hospitalizations and 10 (0.20%) deaths. In the cohort, sickle cell disease was associated with increased risks for COVID-19–related hospitalization (HR, 4.11 [95% CI, 2.98 to 5.66]) and death (HR, 2.55 [CI, 1.36 to 4.75]) (Figure). E-values for HRs for COVID-19–related hospitalization and death were 7.69 (lower limit of the CI, 5.41) and 4.54 (lower limit of the CI, 2.06), respectively, suggesting robustness to residual confounding.

Figure. Adjusted HRs with 95% CIs for the observed associations between sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait with COVID-19–related hospitalization and COVID-19–related death; the reference group is persons without any sickle cell disorder.

![Figure. Adjusted HRs with 95% CIs for the observed associations between sickle cell disease and sickle cell trait with COVID-19–related hospitalization and COVID-19–related death; the reference group is persons without any sickle cell disorder. Cause-specific Cox regression models were stratified by individual general practice and adjusted for age (restricted cubic spline with 5 knots), sex, and self-reported ethnicity (White, South Asian, Black, and other [including Chinese, multiracial, and Arab]). We did post hoc analyses restricted to those with sickle cell disorders. For COVID-19–related hospitalization, compared with persons with sickle cell trait, those with sickle cell disease had an adjusted HR of 3.00 (95% CI, 1.99 to 4.52). For COVID-19–related death, persons with sickle cell disease had an adjusted HR of 1.37 (CI, 0.62 to 3.02) compared with those with sickle cell trait. HR = hazard ratio.](https://cdn.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pmc/blobs/907e/8343340/a6b33a9a0909/aim-olf-M211375-M211375ff1.jpg)

Cause-specific Cox regression models were stratified by individual general practice and adjusted for age (restricted cubic spline with 5 knots), sex, and self-reported ethnicity (White, South Asian, Black, and other [including Chinese, multiracial, and Arab]). We did post hoc analyses restricted to those with sickle cell disorders. For COVID-19–related hospitalization, compared with persons with sickle cell trait, those with sickle cell disease had an adjusted HR of 3.00 (95% CI, 1.99 to 4.52). For COVID-19–related death, persons with sickle cell disease had an adjusted HR of 1.37 (CI, 0.62 to 3.02) compared with those with sickle cell trait. HR = hazard ratio.

Persons with sickle cell trait had 98 (0.38%) hospitalizations and 50 (0.19%) deaths. In the cohort, sickle cell trait was also associated with higher risks for COVID-19–related hospitalization (HR, 1.38 [CI, 1.12 to 1.70]) and death (HR, 1.51 [CI, 1.13 to 2.00]). E-values for COVID-19–related hospitalization and death were 2.1 (lower limit of the CI, 1.49) and 2.39 (lower limit of the CI, 1.51), respectively.

Discussion: Our analysis estimated a 4-fold increased risk for COVID-19–related hospitalization and a 2.6-fold increased risk for COVID-19–related death for sickle cell disease. Sickle cell trait was also associated with increased risks for both outcomes, albeit to a lesser extent. Several aspects of sickle cell phenotypes overlap with the pathophysiology of severe COVID-19 (1, 2), which could be relevant mechanisms worthy of further study, as should the directionality of infection and sickle crisis.

Study limitations include the potential underdiagnosis of sickle cell trait in the population, the rarity of outcomes limiting extended adjustments and sickle subtype–specific or age- or sex-specific analyses, the lack of information on symptoms or presentation, and that the HRs do not possess a direct causal interpretation.

Given that sickle cell disease affects approximately 15 000 persons in the United Kingdom, 100 000 persons in the United States, and 8 million to 12 million persons globally, we believe our results are relevant to policymakers and decision making about vaccination prioritization for potentially high-risk groups.

Appendix: Members of the International Investigator Group for Ethnicity and COVID-19

Members of the International Investigator Group for Ethnicity and COVID-19 who contributed to this work but did not author it: Dr. Pui San Tan, Dr. Martina Patone, Dr. Francesco Zaccardi, Dr. Baiju R. Shah, Professor Simon J. Griffin, and Professor Kamlesh K. Khunti.

Footnotes

This article was published at Annals.org on 20 July 2021.

* For members of the International Investigator Group for Ethnicity and COVID-19, see the Appendix.

Contributor Information

Collaborators: Francesco Zaccardi, Baiju R. Shah, Simon J. Griffin, and Kamlesh K. Khunti

References

- 1. Kato GJ , Piel FB , Reid CD , et al. Sickle cell disease. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2018;4:18010. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2018.10 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Kato GJ , Steinberg MH , Gladwin MT . Intravascular hemolysis and the pathophysiology of sickle cell disease. J Clin Invest. 2017;127:750-760. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1172/JCI89741 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. McCloskey KA , Meenan J , Hall R , et al. COVID-19 infection and sickle cell disease: a UK centre experience [Letter]. Br J Haematol. 2020;190:e57-e58. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1111/bjh.16779 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Panepinto JA , Brandow A , Mucalo L , et al. Coronavirus disease among persons with sickle cell disease, United States, March 20-May 21, 2020. Emerg Infect Dis. 2020;26:2473-2476. [PMID: ] doi: 10.3201/eid2610.202792 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Arlet JB , de Luna G , Khimoud D , et al. Prognosis of patients with sickle cell disease and COVID-19: a French experience. Lancet Haematol. 2020;7:e632-e634. [PMID: ] doi: 10.1016/S2352-3026(20)30204-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]