Abstract

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) disease is a serious pandemic that put the world on an exceptional sanitary alert. It is a multifaceted disease, since it can affect the lung, the cardiovascular system and the central nervous system at the same time. A 66-year-old man, diabetic, hypertensive, admitted to the emergency room for medical management of acute dyspnea, diagnosed with COVID-19 infection. The evolution is marked by respiratory distress as well as new onset atrial fibrillation and a severe ischemic stroke of the brainstem. COVID-19 disease is associated with very serious thromboembolic complications of high incidence, and this is explained by the coagulopathy secondary to the alteration of the microcirculation after the hyper-inflammatory state. Ischemic stroke is one of these complications. The occurrence of new onset atrial fibrillation during COVID-19 infection makes the incidence of ischemic stroke very high and the prognosis more severe. The treatment is mainly based on antithrombotic therapy. Thromboembolic complications remain a real problem to manage in COVID-19 patients given the several mechanisms that promote this situation.

Keywords: Brainstem, Stroke, Covid-19, Coronavirus, New onset atrial fibrillation, Coagulopathy, Mechanical Thrombectomy

Abbreviations: ACE, Angiotensin Converting Enzyme; RF, Respiratory Frequency; BMI, Body Mass Index; RT-PCR, Reverse Transcription Polymerase Chain Reaction; CT, Computed Tomography; HR, Heart Rate; BP, Blood Pressure; GCS, Glasgow Coma Scale; MRI, Magnetic Resonance Imaging; NIHSS, National Institutes Of Health Stroke Scale; CRP, C-Reactive Protein

Introduction

Coronavirus disease (COVID-19) is a viral infection caused by Severe Acute Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus-2. Apart from pulmonary involvement, COVID-19 is accompanied by multiple organ dysfunction [1]. We report the case of a 66-year-old man, admitted for a medical management of a COVID-19 infection. After 5 days of his admission, he presented a new onset atrial fibrillation (NOAF) which was complicated by a fatal ischemic stroke of the brainstem.

Case presentation

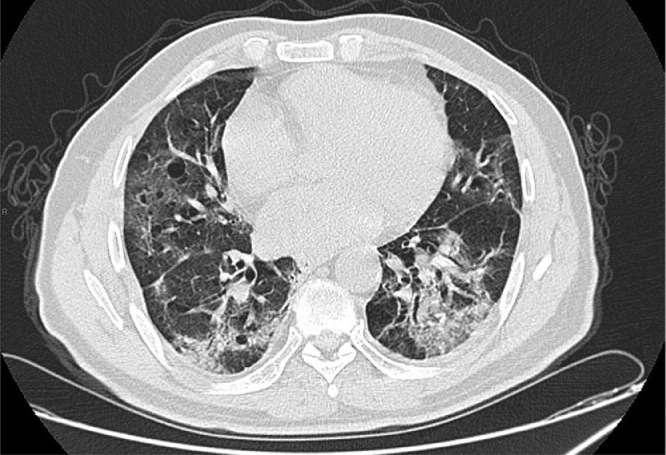

We report the case of a 66-year-old man, with 3 years of well-controlled hypertension on an angiotensin-converting-enzyme inhibitor, well-controlled diabetes for 7 years on metformin 850 mg/d, with the last HbA1c = 6.3%, admitted to the emergency room for the management of acute respiratory failure. On admission, the patient was hemodynamically and neurologically stable, dyspneic with a respiratory rate of 25/min and oxygen saturation SpO2% = 83% on room air, the temperature was 39.7°C, his weight was 99 kg with a height of 1.76cm and a body mass index of 31.96kg/m2. The clinical examination was unremarkable. Given the pandemic context, RT-PCR for SARS-COV 19 was carried out and came back positive. A nonenhanced chest CT scan (Fig. 1) showed peripheral ground-glass opacities typical of SARS-COV 19 infection with pulmonary involvement estimated between 25% and 50%. Blood analysis (Table 1) showed lymphopenia, increased ferritin, CRP and LDH. The arterial blood gas analysis (Table 2) on admission showed hypoxemia with Partial Pressure of Oxygen of 55 mm Hg. The patient was hospitalized in intensive care unit for COVID-19, stabilized respiratory with oxygen therapy via nasal cannula with a flow rate of 7l/min increasing his SpO2% to 93%.

Fig. 1.

Axial nonenhanced chest CT image (lung window) showing bilateral ground-glass opacities typical of SARS-COV 19 infection with pulmonary involvement estimated between 25% and 50%.

Table 1.

Laboratory findings.

| Variable | Normal Value | Day 1 | Day 2 | Day3 | Day4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| WH cells (/ul) | 4000-10000 | 12654 | 11654 | 11700 | 13567 |

| Segmented neutrophils (/ul) | 1500-7000 | 8900 | 8700 | 9230 | 10020 |

| Lymphocytes (/ul) | 1000-4000 | 430 | 360 | 207 | 200 |

| Hemoglobin(g/dl) | 12-16 | 12,7 | 13,6 | 13,5 | 12,9 |

| Platelets (× 104/ul) | 15-40 | 10 | 8,9 | 9,5 | 9,2 |

| ALAT (UI/l) | 0-55 | 76 | 74 | 69 | 82 |

| ASAT (UI/l) | 5-34 | 56 | 59 | 64 | 83 |

| LDH (UI/l) | 125-143 | 487 | 654 | 652 | 596 |

| Serum ferritin (ug/l) | 20-300 | 432 | 476 | 645 | 874 |

| Hematocrit (%) | 37-49 | 51 | 49 | 43 | 47 |

| Glucose(g/l) | 0,7-1,15 | 1,8 | 1,43 | 1,7 | 1,86 |

| CRP (mg/l) | 0-6 | 254,4 | 276,9 | 273,8 | 325,8 |

| Procalcitonin (ng/ml) | 0-0,05 | 1,5 | 1,78 | 2,1 |

1,98 |

| Total protein (g/l) | 64-83 | 67 | 72,8 | 71,8 | 69,7 |

| Albumin (mg/l) | 35-50 | 32 | 36 | 33 | 30 |

| High-sensitive cardiac troponin (pg/ml) | 0-26 | 47 | 127 | 154 | 432 |

| Prothrombin time (sec) | 11-13 | 15,3 | 16 | 15,9 | 17,4 |

| D-dimer (mg/l) | 0-0,5 | 4,6 | 10,3 | 12,4 | 18,6 |

| Fibriogen (g/l) | 2-4 | 6,8 | 8,25 | 8,1 | 7,9 |

| Partial thrombin time(sec) | 30-50 | 56 | 61 | 63 | 72 |

| Urea | 0,15-0,45 | 0,35 | 0,28 | 0,41 | 0,38 |

| Creatinine (mg/l) | 6-12 | 8,5 | 9,65 | 8 | 10,1 |

ALAT, Alanine aminotransferase (UI/l); ASAT, Aspartate aminotransferase; LDH, Lactate dehydrogenase; CRP, C-reactive protein.

Table 2.

Arterial blood gas result.

| Variable | Normal value | Day1 | Day2 | Day3 | Day4 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pH | 7,37-7,43 | 7,46 | 7,34 | 7,27 | 7,23 |

| PaO2 (mm Hg) | >80 | 54 | 49 | 37,6 | 40,2 |

| PaCO2 (mm Hg) | 35-45 | 44,3 | 50,4 | 48,7 | 51,9 |

| SaO2 (%) | >94 | 83 | 87 | 84 | 89 |

| Lactat (mmol/l) | 0-2 | 1,3 | 0,8 | 1,9 | 2,8 |

| HCO3- (mmol/l) | 22-26 | 22,6 | 18,9 | 17,6 | 15,7 |

pH, potential of hydrogen; PaO2, Partial pressure of oxygen in arteriel blood; PaCO2, Partial pressure of carbon dioxide in arteriel blood; HCO3-, Bicarbonate; SaO2, arterial blood saturated with oxygen; Hb, Hemoglobin.

The prescribed treatment includes Vitamin C 2g/d, Zinc 45 mg/12 h, corticosteroid therapy with dexamethasone 6 mg/d, along with therapeutic dosing of low-molecular-weight heparin 8000UI/12H and gastric protection using proton pump inhibitors 20 mg/d.

On the third day of his hospitalization, the patient reports difficulty in breathing even under oxygen therapy with nasal cannula, the SpO2 decreased to 84%, the arterial blood gas analysis (Table 1) showed a severe hypoxemia with Partial Pressure of Oxygen at 47 mm Hg. Contrast-enhanced chest CT (Fig. 2) was performed, showing worsening of the lesions with an estimated pulmonary involvement of more than 75%. The patient required oxygen therapy with a high-concentration mask with a flow rate of 14l/min, as well as 16-hour prone decubitus sessions to achieve a SpO2 of 90%. The evolution was favorable.

Fig. 2.

Axial Contrast-enhanced chest CT image (lung window) showing worsening of the lesions with an estimated pulmonary involvement of more than 75%.

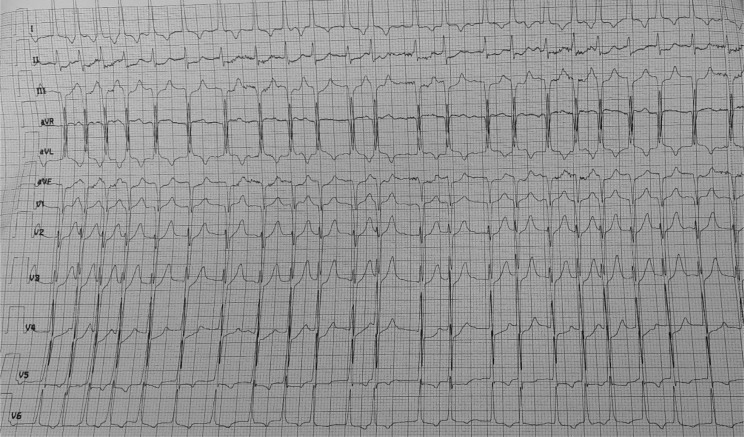

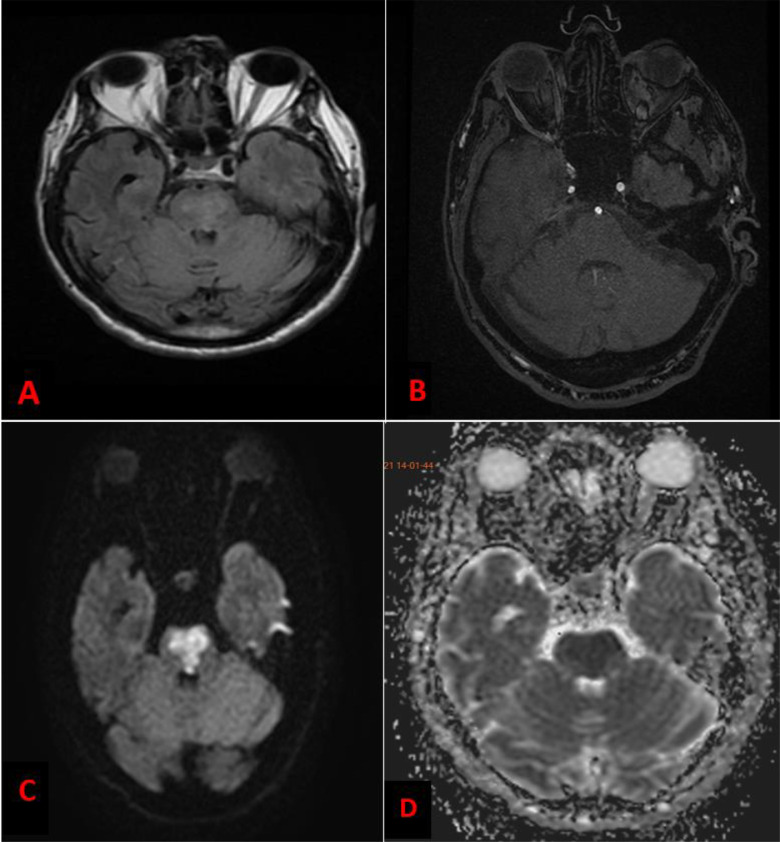

On the fifth day of admission, the patient reports sudden onset of palpitations with worsening of his dyspnea, his heart rate (HR) was 186 bpm, blood pressure was 134/80 mm Hg. The electrocardiogram revealed (Fig. 3) an irregular, narrow-QRS complex tachycardia without P waves, evoking an atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response. In this situation, a rhythm control strategy was chosen. Amiodarone was introduced as a continuous infusion after an initial bolus. The patient's HR slowed but did not drop below 140 bpm. Two hours later, the patient presented a new AF with a ventricular response reaching this time 205 bpm with hemodynamic instability, BP was 70/50 mm Hg, as well as alteration of state of consciousness with Glasgow Coma Scale at 8/15 (E = 1, V = 3, M= 4). In order to stabilize the hemodynamic state, an external electric shock at 260J was performed. Sinus rhythm was restored, HR slowed to 98 bpm, and the patient was hemodynamically stabilized with BP = 125/80 mm Hg, but without recovery of his normal consciousness. Given this context of AF, a stroke is suspected. A cerebral MRI (Fig. 4) was performed 1 hour later and came back in favor of a brainstem acute ischemic stroke. The National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score was calculated to be 35. Given the severe alteration of consciousness, the National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale score as well as the location of stroke, thrombolysis was contraindicated. The patient developed severe neuro-vegetative disorders such as prolonged apnea with extreme bradycardia and tachycardia. Five hours after the onset of palpitations, the patient presented with an unrecovered cardiac arrest on refractory ventricular fibrillation despite the resuscitation measures.

Fig. 3.

The electrocardiogram (EKG) showing atrial fibrillation (AF) with rapid ventricular response.

Fig. 4.

(A) Fluid attenuated inversion recovery (FLAIR) MRI sequence showed a high signal in Pons; (B) 3D Time-of-Flight (TOF) MRI sequence an absence of visualization of the anteromedial branch intended for the pons; (C) Diffusion Weighted Sequence MRI showed a high signal in Pons; (D) Apparent Diffusion Coefficient (ADC) images showed reduced ADC values in Pons.

Discussion

The pandemic of coronavirus 19 (COVID-19) has totally disrupted the world health status because of the severity, the speed of spread and the very high morbidity and mortality of this infection [2].

In COVID-19 disease, cardiovascular involvement remains very frequent and it is associated with a poor prognosis [3].The cardiovascular involvement is mainly represented by arterial and venous thromboembolic events, cardiac arrhythmias, cardiogenic shock, ischemic or non-ischemic myocardial injury and sudden death [2,3]. Apart from the respiratory severity of the disease, the hypercoagulable state remains a serious problem to manage, especially in patients who are hospitalized in intensive care units [4]. The origin of this condition remains poorly elucidated, but the overexpression of the tissue factor and the endothelial dysfunction secondary to the interleukin storm produced by the hyper-inflammatory state remains a well-established hypothesis [1,4].

Thromboembolic events secondary to COVID-19 can be either venous dominated by deep vein thrombosis (DVT) and pulmonary embolism (PE) [5], or arterial [6], and ischemic stroke remains one of the thromboembolic complications associated with a poor prognosis [7].

NOAF is a situation associated to a high risk of embolic accident, especially cerebral [8],with a high mortality in patients who are admitted to the intensive care units [9] especially patients with sepsis [10]. This allows us to deduce that the association of NOAF and COVID-19 disease is a dangerous condition, given the thromboembolic risk, which is highly favored by the coagulopathy of COVID-19 disease on the one hand, and by the embolic risk of atrial fibrillation complicating the cardiac damage of the infection on the other hand, which makes the evolution of these patients severe [11].

The incidence of NOAF in diabetic and hypertensive patients is estimated at 13.3/1000 person-years [12], in the same patients, the thromboembolic risk remains high since their CHA2DS-VA2SC score is greater than or equal to 2. Thus the incidence of thromboembolic events is estimated at 1.6%, and reaches 3.9% in patients over 65 years like in our case [13]. For diabetic and hypertensive patients, it is difficult to estimate the incidence of NOAF during COVID infection given the lack of enough studies, but according to an observational study by Pardo et al. in 160 patients hospitalized with COVID 19 infection, the incidence of NOAF was 7.5% and all of these patients were either hypertensive or diabetic. And the incidence of thromboembolic events in these patients is estimated to be 41.6% compared to 4.1% in patients without NOAF, indicating the severity of NOAF during COVID infection [11].

In patients who are infected with COVID- 19 disease, the incidence of ischemic stroke varies between 2% and 6% [14] and it is explained either by the pro-thrombotic state due to the infection, or by the cardioembolic stroke secondary to the cardiac involvement of the disease [15]. The clinical manifestations are dominated by motor deficit, sensory deficit, dysarthria, headache and aphasia in some cases, the patient may develop a complete coma especially in cases of extensive ischemic stroke or posterior localization, but since these patients are usually under non-invasive ventilation, or even invasive ventilation, the clinical expression is poor, which makes the diagnosis a little difficult.

Ischemic stroke during COVID-19 is characterized by large-vessel occlusions, and especially the involvement of the anterior and middle circulation, which contributes to a worse prognosis [16]. Involvement of the posterior circulation remains rare. The most frequent type is cryptogenic, followed by cardioembolic causes [17].

The biological profile of these patients is generally disturbed mainly at 2 levels: inflammatory with high CRP and high ferritinemia, and hematologically with positive D-Dimers, a prolonged active partial thromboplastin time, a moderate thrombocytopenia, and high fibrinogen and factor VIII [4]. Lupus anticoagulant should also be sought by measuring anticardiolipin antibodies [18].

The management of ischemic stroke in the context of a NOAF is essentially based on 2 components. The first component is antithrombotic treatment based on anticoagulation, but first, the patient's hemorrhagic risk must be well stratified [8]. And the second component is revascularization of the infarcted territory either by intravenous fibrinolysis, or interventional treatment by mechanical thrombectomy [15]. Given the very high bleeding risk due to the associated coagulopathy, mechanical thrombectomy is the best choice for repermeabilization [14,16].

In our case, the NOAF contributed to the onset of ischemic stroke of the brainstem which represents a dangerous localization. The patient's evolution was fatal due to the onset of the neuro-vegetative disorders. This case clearly shows that despite the therapeutic anticoagulation, we could not escape the thromboembolic complications, which demonstrates the severity of the Covid19 disease.

Conclusion

Thromboembolic complications in COVID-19 disease remain a real challenge for the clinician. As our case demonstrates, there are several mechanisms that can contribute to the constitution of these complications, and if they are associated, it is difficult to escape these events, and the best example is NOAF during COVID-19 disease.

Patient consent

Informed consent was obtained from the patient.

Footnotes

Acknowledgments: We would like to thank the team of cardiology and radiology of university hospital for their management and availability. This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Pisano T.J., Hakkinen I., Rybinnik I. Large vessel occlusion secondary to COVID-19 hypercoagulability in a young patient: a case report and literature review. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2020;29(12) doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2020.105307. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Khan M. COVID-19: a global challenge with old history, epidemiology and progress so far. Molecules. 2020;26(1):1–25. doi: 10.3390/molecules26010039. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aidan V., Davido B., Mustafic H., Dinh A., Mansencal N., Fayssoil A. Cardiovascular disorders in patients infected with 2019 novel coronavirus. Ann Cardiol Angeiol (Paris) 2021;70(2):106–115. doi: 10.1016/j.ancard.2020.11.004. Elsevier Masson s.r.l. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Spyropoulos A.C., Weitz J.I. Hospitalized COVID-19 patients and venous thromboembolism: a perfect storm. Circulation. 2020;142(2):129–132. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.120.048020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bikdeli B. COVID-19 and thrombotic or thromboembolic disease: implications for prevention, antithrombotic therapy, and follow-up: JACC state-of-the-art review. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2020;75(23):2950–2973. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2020.04.031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kashi M. Severe arterial thrombosis associated with Covid-19 infection. Thromb Res. 2020;192:75–77. doi: 10.1016/j.thromres.2020.05.025. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Tan Y.-K. COVID-19 and ischemic stroke: a systematic review and meta-summary of the literature. J Thromb Thrombolysis. 2020;50(3):587–595. doi: 10.1007/s11239-020-02228-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hindricks G. 2020 ESC Guidelines for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation developed in collaboration with the European Association for Cardio-Thoracic Surgery (EACTS): the task force for the diagnosis and management of atrial fibrillation of the Europe. Eur Heart J. 2021;42(5):373–498. doi: 10.1093/eurheartj/ehaa612. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Bosch N.A., Cimini J., Walkey A.J. Atrial fibrillation in the ICU. Chest. 2018;154(6):1424–1434. doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2018.03.040. Elsevier Inc. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Klein Klouwenberg P.M.C. Incidence, predictors, and outcomes of new-onset atrial fibrillation in critically ill patients with sepsis a cohort study. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2017;195(2):205–211. doi: 10.1164/rccm.201603-0618OC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.A. Pardo Sanz et al., “New-onset atrial fibrillation during COVID-19 infection predicts poor prognosis,” 2021, doi: 10.5603/CJ.a2020.0145. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.L. Alves-Cabratosa et al., “Diabetes and new-onset atrial fibrillation in a hypertensive population,” 2016, doi: 10.3109/07853890.2016.1144930. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 13.Lip G.Y.H., Nieuwlaat R., Pisters R., Lane D.A., Crijns H.J.G.M. Refining clinical risk stratification for predicting stroke and thromboembolism in atrial fibrillation using a novel risk factor-based approach: the euro heart survey on atrial fibrillation. Chest. 2010;137(2):263–272. doi: 10.1378/chest.09-1584. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.L. Mao et al., “Neurologic manifestations of hospitalized patients with coronavirus disease 2019 in Wuhan, China,” 2020, doi: 10.1001/jamaneurol.2020.1127. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 15.Qureshi A.I. Management of acute ischemic stroke in patients with COVID-19 infection: report of an international panel. Int J stroke Off J Int Stroke Soc. 2020;15(5):540–554. doi: 10.1177/1747493020923234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.John S. Characteristics of large-vessel occlusion associated with COVID-19 and ischemic stroke. Am J Neuroradiol. 2020;41(12):2263–2268. doi: 10.3174/ajnr.A6799. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kim B.Joon. COVID-19 and cerebrovascular diseases: a systematic review and perspectives for stroke management. Front Neurol. 2020;11 doi: 10.3389/fneur.2020.574694. | www.frontiersin.org. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.“Covid-19 Cases Coagulopathy and Antiphospholipid Antibodies in Patients with Covid-19,” 2020, doi: 10.1056/NEJMc2007575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]