Abstract

Young Black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men (YB-GBMSM) are disproportionately impacted by HIV/AIDS. Novel intervention strategies are needed to optimize engagement in HIV care for this population. We sought to develop a group-level intervention to enhance resilience by augmenting social capital (defined as the sum of resources in an individual’s social network) among YB-GBMSM living with HIV, with the ultimate goal of improving engagement in HIV care. Our multiphase, community-based participatory research (CBPR) intervention development process included: (1) Development and maintenance of a youth advisory board (YAB) comprised of YB-GBMSM living with HIV; (2) Qualitative in-depth interviews with YB-GBMSM living with HIV; (3) Qualitative in-depth interviews with care and service providers at clinics and community-based organizations; and (4) Collaborative development of intervention modules and activities with our YAB, informed by social capital theory and our formative research results. The result of this process is Brothers Building Brothers By Breaking Barriers, a two-day, 10-module group-level intervention. The intervention does not focus exclusively on HIV, but rather takes a holistic approach to supporting youth and enhancing resilience. Intervention modules aim to develop resilience at the individual level (exploration of black gay identity, development of critical self-reflection and coping skills), social network level (exploring strategies for navigating family and intimate relationships) and community level (developing strategies for navigating clinical spaces and plans for community participation). Most intervention activities are interactive, in order to facilitate new social network connections – and accompanying social capital – within intervention groups. In summary, our intensive CBPR approach resulted in a novel, culturally-specific intervention designed to enhance HIV care engagement by augmenting resilience and social capital among YB-GBMSM living with HIV.

Keywords: HIV/AIDS, resilience, youth, social capital

Introduction

Although overall HIV incidence rates in the United States (US) remain relatively stable, high rates of new infections are still occurring among young Black gay/bisexual and other men who have sex with men (YB-GBMSM) ages 13–29 years (Matthews et al., 2016; Prejean et al., 2011). Furthermore, YB-GBMSM who are living with HIV are at heightened risk for suboptimal engagement across the care continuum (Saha, Kermode, & Annear, 2015; Singh et al., 2014). Black GBMSM often face significant cultural barriers to obtaining appropriate medical care, including discrimination and mistrust within patient-provider relationships, which may be compounded by structural barriers such as lack of insurance and transportation difficulties (Harper et al., 2013; Malebranche, Peterson, Fullilove, & Stackhouse, 2004; Mimiaga et al., 2009). Novel interventions are urgently needed to improve engagement in care among YB-GBMSM, in order to decrease individual morbidity and mortality among individuals living with HIV, and to prevent secondary HIV transmission in communities (Cohen et al., 2011; Mugavero, Amico, Horn, & Thompson, 2013).

One innovative approach to addressing this need is through the development of interventions that aim to enhance resilience, in contrast with traditional deficit- or risk-based public health intervention design (Herrick, Stall, Goldhammer, Egan, & Mayer, 2014; McNair et al., 2017). Resilience is defined as positive adaptation in spite of adversity (Luthar, Cicchetti, & Becker, 2000). According to Fergus and Zimmerman, resilience is comprised of both assets (referring to internally held factors such as self-efficacy or coping skills) and resources (factors external to the individual, such as parental support or community-based organizations) that enable an individual to withstand or overcome challenges in their lives (Fergus & Zimmerman, 2005). Despite multiple, intersecting societal disadvantages, YB-GBMSM living with HIV have been observed to display both assets (e.g., strong ethnic and/or gay identity beliefs) and resources (e.g., enlisting social support, peer mentorship), and to translate these resilience factors into HIV care engagement behaviors (Harper, Bruce, Hosek, Fernandez, & Rood, 2014; Hussen et al., 2015; Hussen et al., 2017).

Social capital, defined as the net worth of an individual’s resource-containing reciprocal, and trustworthy social network connections (Bourdieu, 1986; Chen, Stanton, Gong, Fang, & Li, 2009), is an important resilience resource that has been shown to positively impact a range of different health outcomes, including HIV care engagement. Social capital can be divided into two main components: bonding capital and bridging capital (Szreter & Woolcock, 2004). Bonding capital refers to resources accessed within social groups whose members are relatively homogeneous in terms of sociodemographic identity, while bridging capital refers to resources derived from cross-identity connections. Both bonding and bridging capital can be used to elicit new and useful resilience resources, such as informational support, instrumental support, emotional support; and they can also be used to build collective efficacy (an asset). The majority of the work on social capital and HIV care engagement has been conducted internationally, particularly in sub-Saharan Africa. This work has identified the mobilization of social capital as a key resilience process through which HIV-positive individuals maintain high rates of care engagement despite living in social contexts characterized by high stigma and low resource availability (Bangsberg, 2011; Binagwaho & Ratnayake, 2009; Ware et al., 2009).

Social capital represents a potentially underutilized resilience resource that can be targeted and augmented to improve engagement in HIV care for YB-GBMSM. We cite three major reasons for why this approach is likely to be effective. First, social capital can yield health-promoting “profits” such as emotional support, access to information, and financial assistance (Chen et al., 2009). Studies based in several sub-Saharan African countries have described how social capital can improve HIV care engagement in very concrete ways. For example, social network contacts can educate one another about HIV, provide transportation assistance to get to appointments, or simply endorse health-promoting norms that make an HIV-positive individual feel better about engaging in care (Hussen et al., 2014; Ware et al., 2009). Second, observational studies in the US are mixed, but largely support the idea of a similarly positive relationship between social capital and HIV-related outcomes – including HIV symptom management and ART adherence (Phillips et al., 2013; Ransome et al., 2018; Webel et al., 2015). Third, although social capital research is scant among YB-GBMSM specifically, it is well-established that social relationships are critically important to the resilience of ethnic and sexual minority youth, including YB-GBMSM living with HIV. Specifically, YB-GBMSM draw from unique and diverse support networks that can include biological family, friends, sexual partners, informal “gay families”, and other mentors (Kubicek, McNeeley, Holloway, Weiss, & Kipke, 2013; McFadden, Bouris, Voisin, Glick, & Schneider, 2014; Torres, Harper, Sanchez, Fernandez, & The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions, 2012).

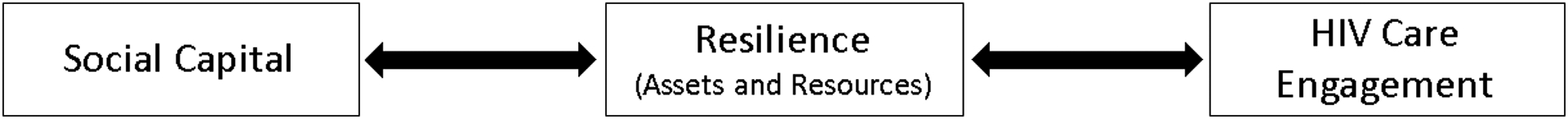

Based on the above scientific premise, we first conducted a cross-sectional survey study at a large, urban HIV care center in the Southeastern US, in order to begin to examine relationships between social capital and HIV outcomes for YB-GBMSM. We found that social capital buffered the effects of depression on HIV viral load suppression in our sample; that is – those participants with depressive symptoms and higher social capital were able to maintain HIV care engagement, while those with lower social capital were not (Hussen et al., 2018). Building on this exploratory research, we hypothesized that the diverse social networks of YB-GBMSM living with HIV contain significant social capital, which can in turn yield resilience (assets and resources) that can be utilized to improve engagement in HIV care for this population (Figure 1). Accordingly, we sought to develop a culturally tailored resilience-building intervention with the goal of enhancing care engagement by augmenting social capital. This paper describes the process of developing the intervention: Brothers Building Brothers By Breaking Barriers.

Figure 1.

Proposed relationships between social capital, resilience and HIV care engagement

Methods

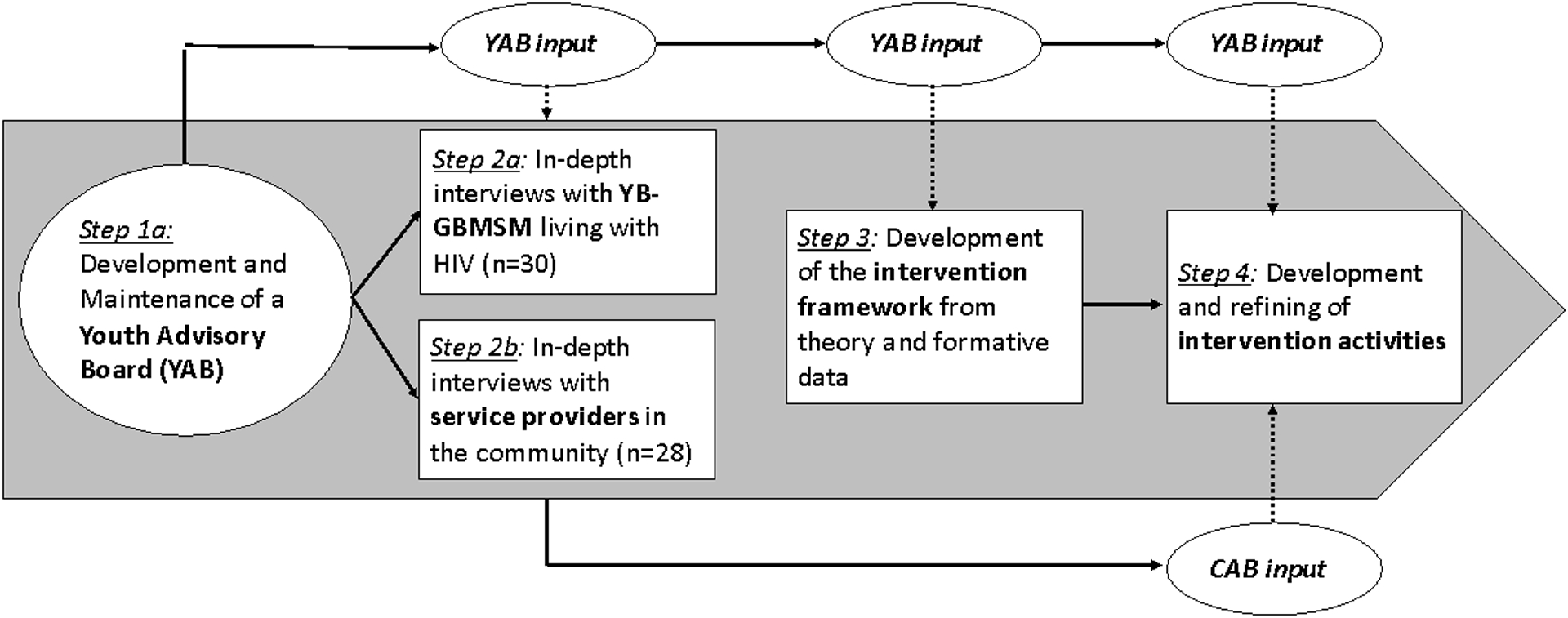

Our intervention development process consisted of the following steps: (1) development and maintenance of a youth advisory board (YAB) comprised of YB-GBMSM living with HIV; (2) qualitative in-depth interviews (IDIs) with YB-GBMSM as well as service providers who work with YB-GBMSM; (3) development of an intervention framework; and (4) development of intervention modules and activities (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Community-based participatory intervention development process

Development and maintenance of the youth advisory board (YAB)

In order to develop our intervention in a manner that was culturally and developmentally appropriate, and to enhance the future acceptability and effectiveness of the intervention, we approached intervention development from a community-based participatory research (CBPR) perspective (Israel, Schulz, Parker, & Becker, 1998). Integral to this approach was the development of a YAB to collaborate with the study team and guide all steps of the research process. We recruited potential YAB members through: (1) advertisement on social media groups targeting youth living with HIV; (2) recommendations from contacts at HIV- and LGBT-focused community-based organizations (CBOs); and (3) direct recruitment of YB-GBMSM known to study team members from prior community work. Interested applicants completed an online screening questionnaire; those who were eligible and interested were then interviewed in person. Eligibility criteria for the YAB include self-reported Black race, gay/bisexual orientation and/or MSM behavior, age between 18–29 years, and self-reported HIV-positive status. A group of nine YB-GBMSM were ultimately selected based on personal qualities (e.g., passion for community work, professionalism), commitment to the CBPR process, and efforts to balance the personalities and experiences of the YAB.

Our selected YAB members were hired as research assistants by our academic institution. YAB members committed to two 5- hour meetings per month, and they were compensated at an hourly rate for this time. YAB meetings included team-building activities, trainings in public health research ethics, direct solicitation of input about research processes, and development and pilot testing of intervention activities.

Qualitative Interviews with YB-GBMSM living with HIV and service providers

We conducted 29 IDIs with YB-GBMSM living with HIV. YB-GBMSM ages 18–29 years were recruited through an HIV clinic as well as through recommendations of the YAB, CBO staff, or study team. Our maximum variation purposive sampling scheme aimed to recruit youth who were perceived as well-connected (by an informal assessment of the referring individual), as well as those who were thought to have comparatively less social capital. With this sampling strategy, we hoped to gain greater insights into the nature of social capital among YB-GBMSM living with HIV. Our interview guide for YB-GBMSM included the following domains: (1) Description of sources of social capital in their networks; (2) HIV stigma, disclosure and gay identity; (3) Utilization of social capital; (4) Reciprocity; (5) Negative social capital; and (6) Intervention recommendations.

Next, we conducted 28 IDIs with key informants – healthcare and social service providers – in the community, in order to gain their perspectives on the strengths and challenges facing YB-GBMSM living with HIV. Key informants included staff members at local CBOs, as well as medical providers caring for YB-GBMSM in their clinical practices. Key informants were nominated by the study team and YAB members for their expertise working with our population of interest. We again employed purposive sampling strategies in order to gain a diverse set of recommendations for our intervention – respondents varied in terms of age, race, gender, sexual orientation, educational background, current occupation. The interview guide for key informants focused on the following major domains: (1) Assessment of the strengths and resilience of YB-GBMSM; (2) Assessment of major challenges facing YB-GBMSM; and (3) recommendations for future programming.

All interviews were conducted in mutually convenient, private locations including clinic spaces and participants’ offices. Most interviews were conducted by study team members (MJ and SM); some were also conducted by YAB members under the supervision of research staff. All interviews were digitally recorded and transcribed verbatim by a professional service; transcripts were then uploaded into MAXQDA qualitative data management software (VERBI software, Berlin, Germany) for further analysis. All participants received a $50 gift card as a token of appreciation for their participation. The study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board and Grady Research Oversight Committee.

Qualitative Analysis

For the purpose of intervention development, we undertook a content analysis approach to examining our data (Bengtsson, 2016). This analytic approach allows for an efficient organization and reduction of qualitative data, in order to describe the recurrent and prominent themes therein. More in-depth conceptual relationships and thematic analyses will be presented elsewhere (Hussen et al., manuscript in preparation). Study team members examined IDI transcripts from key informants and YB-GBMSM, with specific attention to content pertaining to programmatic recommendations, and listed themes that arose across the transcripts. We next examined the lists of recurrent themes and identified challenges, strengths and recommendations that were mentioned with the greatest frequency. Finally, we presented the most prominent recommendations to the YAB for member-checking – they in turn ranked recommendations by priority, resulting in a final list of recommendations to be incorporated into the intervention.

Results

Development of the Intervention Framework

Intervention content was based on the formative qualitative research findings, guided by social capital and resilience theories, and iteratively refined based on ongoing, periodic feedback from the YAB. Based on the qualitative content analyses described above, a condensed list of key programmatic recommendations was agreed upon for incorporation into the intervention (Table 1). Recommendations clustered into two areas: those that recommended specific intervention content, and those that discussed best practices for how to approach work with YB-GBMSM. Overall, participants responded favorably to the idea of a social capital intervention for YB-GBMSM living with HIV. Many respondents expressed appreciation for the resilience-oriented framework as a welcome change from deficit-centered and/or behavior-focused models. Across participants, the most common recommendation was to ensure that the intervention addressed the holistic health and well-being of the participants, and did not focus too narrowly on HIV or sexual health. Many participants also cited the importance of group-based activities and interactions, and the need to incorporate fun and entertainment with the educational objectives.

Table 1.

Key Recommendations from Qualitative Interviews

|

Recommendations for Intervention Content Find a way to treat the whole person Empower participants with skills to get the support they need Raise awareness and pride about Black gay culture and history Address stigma and internalized homophobia Find ways to create connectedness between YB-GBMSM Refer participants to other resources as needed, particularly mental health Recommendations for the Intervention Approach Engage participants, make activities interactive and entertaining Utilize interactive group discussions Be nonjudgmental, sex positive Consider judicious use of social media Meet participants where they are in terms of interest in HIV care engagement |

Based on social capital and resilience theories, we developed the intervention outline, which focused on four overarching goals: (1) exploration of one’s self and identities; (2) building bonding capital; (3) building bridging capital; and (4) sustaining connections. Next, we utilized the key informants’ recommendations and worked closely with our YAB to develop activities that would provide participants with the skills and knowledge to attain the four main goals. Our development process was informed by Intervention Mapping, a planning approach that combines theory and evidence as the foundation for taking an ecological approach to assessing and intervening in health problems and engendering community participation (Eldredge, Markham, Ruiter, Kok, & Parcel, 2016). All activities were created in close collaboration with the YAB. Ideas for activity format and content were often generated by the YAB members. At other times, research team members brought up a general idea and YAB members gave input into how best to operationalize and/or modify it. Initially, we created 15 modules - this was reduced to 10 due to time constraints and a desire to streamline the intervention. In selecting modules for the final version, we sought to balance individual-focused, reflective activities with interactive group activities that would help participants to build bonds with one another. Table 2 describes the learning goals and objectives for each of the 10 intervention modules, which are to be administered over two full days, with a final follow-up (intervention booster) session held one month later.

Table 2.

Brothers Building Brothers By Breaking Barriers: Intervention Description

| Module Title | Description of Module Activities | Module Goals |

|---|---|---|

| Introduction | ||

| Module 1: Set the Stage | Welcome, introductions, and icebreaker activities. | Provide outline of program, introduce facilitators and participants, set expectations, and create a safe space |

| Module 2: Who’s on your team? | Didactic presentation and interactive activity teaching the concept and utility of social capital | Explain the theoretical foundation of the intervention |

| Building Myself | ||

| Module 3: Who am I? | Interactive activities exploring self-perceptions and intersectional identities at the individual level. Group activities facilitating participants’ affirmations of each other. | Identify the ways in which multiple identities (e.g., gay identity, Black racial identity, HIV-positive identity) interact |

| Module 4: Critical self-reflection | Didactic portion on critical self-reflection techniques (e.g, the practice of asking “What? So what? Now what?) and small group activities to apply skills to hypothetical case scenarios centered around pertinent themes (e.g., HIV disclosure, homophobia). | Reflect on how individual actions impact others; discuss common stressors and positive coping strategies |

| Module 5: Communicating my needs | Didactic activity to illustrate differences between passive, aggressive and assertive communication. Reflective activities around individual communication preferences. | Reflect on personal communication styles and common barriers to effective communication |

| Building Bridges | ||

| Module 6: Breaking Barriers - Relationships | Reflective activities in which participants identify sources of social capital in their existing networks, and role-play activities to practice new communication skills. | Reflect on communication in relationships and potential social capital therein. Build conflict resolution skills. |

| End Day 1 | ||

| Module 7: Breaking Barriers – Professional Settings | Interactive case scenarios to help participants navigate bias and other obstacles at work or school. Group activity to discuss priorities in choosing healthcare providers and linking to HIV care. | Build skills for succeeding in professional arenas and cultivating relationships with colleagues and supervisors. Enhance skills for successfully navigating healthcare settings. |

| Building Bonds | ||

| Module 8: Black Gay Community | Individual reading of information about selected notable individuals in Black gay history followed by game to test knowledge. Group discussion of current norms in Black gay community. | Gain appreciation of the historical contributions of Black gay men, discuss and critique social norms on modern Black gay culture. |

| Staying Connected | ||

| Module 9: Connecting the Dots | Individually-focused worksheets about their future goals and strategize how to apply their social capital to achieve these goals. Group activity in which participants work together to identify social capital in the community that can help YB-GBMSM living with HIV. | Set short and long-term goals for career, relationships and health while reflecting on the role of social capital in achieving these goals. Build a sense of future orientation. |

| Module 10: My social capital | Introduction to follow-up project to be completed over the next month (Photovoice). Group affirmation activity. Distribution of resource list. | Introduce Photovoice community action project. Provide affirmation to one another. Conclude intervention session. |

| Intervention Booster | ||

| Module 11: Follow-Up (one month later) |

Review photos taken by each participant over the preceding month with accompanying group discussion. | Photovoice follow-up and discussion. Reflect on progress toward short term goals and utilization of social capital in the interim. |

Once the intervention manual was completed, activities were tested and refined with the YAB in an iterative fashion. Finally, we presented descriptions of all intervention modules and activities to a community advisory board (CAB) made up of a subset of service providers who had participated in the qualitative interviews. The CAB provided additional feedback, which was incorporated into subsequent refinements of the intervention manual.

Intervention Content

This group-level intervention contains activities that hone individual self-reflection skills, in addition to interactive group activities that facilitate bonding between participants. Skills developed early in the intervention are revisited later on – for example, participants are taught assertive communication strategies and then later asked to apply them to specific scenarios that YB-GBMSM living with HIV might be more likely to encounter (e.g., status disclosure, workplace bias). The individual activities primarily reflect the key informants’ recommendations to treat the whole person and build skills; while group activities align with guidance to create connectedness among YB-GBMSM and engage participants in interactive and entertaining activities. The key informants’ emphasis on cultural awareness and pride is specifically incorporated in a series of activities that focus on the intersectional identities of YB-GBMSM. See Table 2 for more details on intervention content.

Discussion

We employed a CBPR process to develop a novel intervention designed to enhance social capital and engagement in HIV care among YB-GBMSM. IDIs with service providers and YB-GBMSM, as well as frequent and in-depth involvement from a YAB of YB-GBMSM living with HIV, confirmed the appropriateness of our theoretical basis in social capital. Additionally, community stakeholders expressed appreciation for our resilience-oriented perspective, and were optimistic about the likelihood of achieving our desired outcomes. Our iterative approach to intervention development allowed for meaningful, longitudinal involvement of youth and community stakeholders, which kept the content of the intervention grounded in the lived experiences of YB-GBMSM living with HIV.

Our intervention focuses on developing participants’ appreciation for their intersectional identities, creating and strengthening bonds with other YB-GBMSM living with HIV, and honing strategies for connecting to others in their social networks and communities. Perhaps the central feature of the intervention, however, is the holistic approach through which we aim to treat participants as young men first – in contrast to existing interventions that focus more narrowly on medication adherence, appointment attendance, or sexual health (Crosby et al., 2018; Hightow-Weidman et al., 2011; LeGrand et al., 2016). While such interventions are critically important, our holistic framework is more responsive to calls for resilience-focused interventions among gay men (Herrick et al., 2014), and to the mounting evidence of the larger health benefits of addressing multiple psychosocial factors such as gay identity and gay community involvement (Bruce, Harper, & Bauermeister, 2015; Harper et al., 2013; Mustanski, Andrews, Herrick, Stall, & Schnarrs, 2014). Furthermore, by influencing resilience more broadly, our intervention may have the added benefit of positively impacting a range of health behaviors and outcomes (e.g., mental health and/or quality of life outcomes) for this population.

Limitations

There are certain challenges and limitations that we anticipate during intervention implementation. Transportation and scheduling difficulties could be barriers to participation in our two-day, face-to-face intervention. Additionally, themes addressed in the intervention modules may evoke strong emotions, and could even be traumatic for some participants. We will attempt to mitigate this risk by provide training in crisis counseling for our facilitators, combined with referrals to mental health professionals for follow-up care as needed. The intervention may also be limited by geographic specificity; cultural relevance of some of the modules we developed may not extend beyond the urban southeastern US. Finally, we should acknowledge that the intervention may not be relevant for YB-GBMSM who identify as gender non-conforming or transgender, given that we did not obtain significant feedback in our formative phase from members of these particular communities.

Conclusions

Comprehensive interventions that build resilience and harness existing strengths within communities of YB-GBMSM are urgently needed, in order to address suboptimal care engagement and unacceptably high levels of ongoing HIV transmission among YB-GBMSM. Our intervention adds to the HIV care engagement and secondary prevention toolkits by incorporating a resilience-based approach, rather than pathologizing YB-GBMSM or focusing narrowly on HIV status and sexual risk behavior. To our knowledge, no intervention to date has previously been developed specifically to augment social capital and resilience among YB-GBMSM.

The next phase of research will be a pilot randomized controlled trial of our intervention. If the intervention is found to positively impact social capital, resilience, and engagement in HIV care among YB-GBMSM, future directions could include scale up and adoption by organizations serving YB-GBMSM. We believe that our novel intervention has the potential to improve the overall health and well-being of YB-GBMSM living with HIV, including but not limited to HIV-related clinical outcomes. Holistic, culturally tailored, resilience-based interventions represent an untapped resource in the fight to eliminate the pervasive burden of HIV in this high-priority population.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (U01PS005112) and Emory Center for AIDS Research (P30AI050409). We thank the members of the Youth Advisory Board, Community Advisory Board, and the participants (both service providers and young men) in our qualitative interviews. Finally, we would also like to acknowledge the excellent services of Exceptional Transcription and Business Solutions, Inc.

References

- Bangsberg DR (2011). Perspectives on adherence and resistance to ART. Paper presented at the 18th Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections, Boston, MA. [Google Scholar]

- Bengtsson M (2016). How to plan and perform a qualitative study using content analysis. NursingPlus Open, 2, 8–14. [Google Scholar]

- Binagwaho A, & Ratnayake N (2009). The role of social capital in successful adherence to antiretroviral therapy in Africa. PLoS Med, 6(1), e18. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bourdieu P (1986). The forms of capital. In Readings in economic sociology (pp. 280–291): Wiley Online Library. [Google Scholar]

- Bruce D, Harper GW, & Bauermeister JA (2015). Minority Stress, Positive Identity Development, and Depressive Symptoms: Implications for Resilience among Sexual Minority Male Youth. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers, 2(3), 287–296. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000128 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen X, Stanton B, Gong J, Fang X, & Li X (2009). Personal Social Capital Scale: an instrument for health and behavioral research. Health Educ Res, 24(2), 306–317. doi: 10.1093/her/cyn020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen MS, Chen YQ, McCauley M, Gamble T, Hosseinipour MC, Kumarasamy N, … HPTN Study Team. (2011). Prevention of HIV-1 infection with early antiretroviral therapy. N Engl J Med, 365(6), 493–505. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1105243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Crosby RA, Mena L, Salazar LF, Hardin JW, Brown T, & Vickers Smith R (2018). Efficacy of a Clinic-Based Safer Sex Program for Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Uninfected and Human Immunodeficiency Virus-Infected Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Sex Transm Dis, 45(3), 169–176. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000721 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldredge LKB, Markham CM, Ruiter RA, Kok G, & Parcel GS (2016). Planning health promotion programs: an intervention mapping approach. (Fourth Edition ed.). San Francisco, CA: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Fergus S, & Zimmerman MA (2005). Adolescent resilience: a framework for understanding healthy development in the face of risk. Annu Rev Public Health, 26, 399–419. doi: 10.1146/annurev.publhealth.26.021304.144357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Bruce D, Hosek SG, Fernandez MI, & Rood BA (2014). Resilience processes demonstrated by young gay and bisexual men living with HIV: implications for intervention. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 28(12), 666–676. doi: 10.1089/apc.2013.0330 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper GW, Fernandez IM, Bruce D, Hosek SG, Jacobs RJ, & Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2013). The role of multiple identities in adherence to medical appointments among gay/bisexual male adolescents living with HIV. AIDS Behav, 17(1), 213–223. doi: 10.1007/s10461-011-0071-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrick AL, Stall R, Goldhammer H, Egan JE, & Mayer KH (2014). Resilience as a research framework and as a cornerstone of prevention research for gay and bisexual men: theory and evidence. AIDS Behav, 18(1), 1–9. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0384-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hightow-Weidman LB, Fowler B, Kibe J, McCoy R, Pike E, Calabria M, & Adimora A (2011). HealthMpowerment.org: development of a theory-based HIV/STI website for young black MSM. AIDS Educ Prev, 23(1), 1–12. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2011.23.1.1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussen SA, Andes K, Gilliard D, Chakraborty R, Del Rio C, & Malebranche DJ (2015). Transition to Adulthood and Antiretroviral Adherence Among HIV-Positive Young Black Men Who Have Sex With Men. Am J Public Health, 105(4), 725–731. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2014.301905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussen SA, Easley KA, Smith JC, Shenvi N, Harper GW, Camacho-Gonzalez AF, … Del Rio C (2018). Social Capital, Depressive Symptoms, and HIV Viral Suppression Among Young Black, Gay, Bisexual and Other Men Who Have Sex with Men Living with HIV. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-018-2105-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussen SA, Harper GW, Rodgers CRR, van den Berg JJ, Dowshen N, & Hightow-Weidman LB (2017). Cognitive and behavioral resilience among young gay and bisexual men living with HIV. LGBT Health, 4(4), 275–282. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hussen SA, Tsegaye M, Argaw MG, Andes K, Gilliard D, & Del Rio C (2014). Spirituality, social capital and service: Factors promoting resilience among Expert Patients living with HIV in Ethiopia. Glob Public Health. doi: 10.1080/17441692.2014.880501 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Israel BA, Schulz AJ, Parker EA, & Becker AB (1998). Review of community-based research: assessing partnership approaches to improve public health. Annual Review of Public Health, 19(1), 173–202. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kubicek K, McNeeley M, Holloway IW, Weiss G, & Kipke MD (2013). “It’s like our own little world”: resilience as a factor in participating in the Ballroom community subculture. AIDS Behav, 17(4), 1524–1539. doi: 10.1007/s10461-012-0205-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- LeGrand S, Muessig KE, McNulty T, Soni K, Knudtson K, Lemann A, … Hightow-Weidman LB (2016). Epic Allies: Development of a Gaming App to Improve Antiretroviral Therapy Adherence Among Young HIV-Positive Men Who Have Sex With Men. JMIR Serious Games, 4(1), e6. doi: 10.2196/games.5687 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthar SS, Cicchetti D, & Becker B (2000). The construct of resilience: a critical evaluation and guidelines for future work. Child Dev, 71(3), 543–562. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Malebranche DJ, Peterson JL, Fullilove RE, & Stackhouse RW (2004). Race and sexual identity: perceptions about medical culture and healthcare among Black men who have sex with men. J Natl Med Assoc, 96(1), 97–107. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matthews DD, Herrick AL, Coulter RW, Friedman MR, Mills TC, Eaton LA, … Power Study Team. (2016). Running Backwards: Consequences of Current HIV Incidence Rates for the Next Generation of Black MSM in the United States. AIDS Behav, 20(1), 7–16. doi: 10.1007/s10461-015-1158-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McFadden RB, Bouris AM, Voisin DR, Glick NR, & Schneider JA (2014). Dynamic social support networks of younger black men who have sex with men with new HIV infection. AIDS Care, 26(10), 1275–1282. doi: 10.1080/09540121.2014.911807 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McNair OS, Gipson JA, Denson D, Thompson DV, Sutton MY, & Hickson DA (2017). The Associations of Resilience and HIV Risk Behaviors Among Black Gay, Bisexual, Other Men Who Have Sex with Men (MSM) in the Deep South: The MARI Study. AIDS Behav. doi: 10.1007/s10461-017-1881-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mimiaga MJ, Reisner SL, Bland S, Skeer M, Cranston K, Isenberg D, … Mayer KH (2009). Health system and personal barriers resulting in decreased utilization of HIV and STD testing services among at-risk black men who have sex with men in Massachusetts. AIDS Patient Care STDS, 23(10), 825–835. doi: 10.1089/apc.2009.0086 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mugavero MJ, Amico KR, Horn T, & Thompson MA (2013). The state of engagement in HIV care in the United States: from cascade to continuum to control. Clin Infect Dis, 57(8), 1164–1171. doi: 10.1093/cid/cit420 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mustanski B, Andrews R, Herrick A, Stall R, & Schnarrs PW (2014). A syndemic of psychosocial health disparities and associations with risk for attempting suicide among young sexual minority men. Am J Public Health, 104(2), 287–294. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillips JC, Webel A, Rose CD, Corless IB, Sullivan KM, Voss J, … Holzemer WL (2013). Associations between the legal context of HIV, perceived social capital, and HIV antiretroviral adherence in North America. BMC Public Health, 13, 736. doi: 10.1186/1471-2458-13-736 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Prejean J, Song R, Hernandez A, Ziebell R, Green T, Walker F, … HIV Incidence Surveillance Group. (2011). Estimated HIV incidence in the United States, 2006–2009. PLoS One, 6(8), e17502. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0017502 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ransome Y, Thurber KA, Swen M, Crawford ND, German D, & Dean LT (2018). Social capital and HIV/AIDS in the United States: Knowledge, gaps, and future directions. SSM Popul Health, 5, 73–85. doi: 10.1016/j.ssmph.2018.05.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha S, Kermode M, & Annear PL (2015). Effect of combining a health program with a microfinance-based self-help group on health behaviors and outcomes. Public Health. doi: 10.1016/j.puhe.2015.07.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh S, Bradley H, Hu X, Skarbinski J, Hall HI, & Lansky A (2014). Men living with diagnosed HIV who have sex with men: progress along the continuum of HIV care--United States, 2010. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep, 63(38), 829–833. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Szreter S, & Woolcock M (2004). Health by association? Social capital, social theory, and the political economy of public health. Int J Epidemiol, 33(4), 650–667. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyh013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres RS, Harper GW, Sanchez B, Fernandez MI, & The Adolescent Medicine Trials Network for HIV/AIDS Interventions. (2012). Examining Natural Mentoring Relationships (NMRs) among Self-Identified Gay, Bisexual, and Questioning (GBQ) Male Youth. Child Youth Serv Rev, 34(1), 8–14. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2010.12.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ware NC, Idoko J, Kaaya S, Biraro IA, Wyatt MA, Agbaji O, … Bangsberg DR (2009). Explaining adherence success in sub-Saharan Africa: an ethnographic study. PLoS Med, 6(1), e11. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Webel AR, Wantland D, Rose CD, Kemppainen J, Holzemer WL, Chen WT, … Portillo C (2015). A Cross-Sectional Relationship Between Social Capital, Self-Compassion, and Perceived HIV Symptoms. J Pain Symptom Manage, 50(1), 59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.jpainsymman.2014.12.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]