Abstract

Objective

Physical therapists are well positioned to meet societal needs and reduce the global burden of noncommunicable diseases through the integration of evidence-based population health, prevention, health promotion, and wellness (PHPW) activities into practice. Little guidance exists regarding the specific PHPW competencies that entry-level clinicians ought to possess. The objective of this study was to establish consensus-based entry-level PHPW competencies for graduates of US-based physical therapist education programs.

Methods

In a 3-round modified Delphi study, a panel of experts (N = 37) informed the development of PHPW competencies for physical therapist professional education. The experts, including physical therapists representing diverse practice settings and geographical regions, assessed the relevance and clarity of 34 original competencies. Two criteria were used to establish consensus: a median score of 4 (very relevant) on a 5-point Likert scale, and 80% of participants perceiving the competency as very or extremely relevant.

Results

Twenty-five competencies achieved final consensus in 3 broad domains: preventive services and health promotion (n = 18), foundations of population health (n = 4), and health systems and policy (n = 3).

Conclusions

Adoption of the 25 accepted competencies would promote consistency across physical therapist education programs and help guide physical therapist educators as they seek to integrate PHPW content into professional curricula.

Impact

This is the first study to establish consensus-based competencies in the areas of PHPW for physical therapist professional education in the United States. These competencies ought to guide educators who are considering including or expanding PHPW content in their curricula. Development of such competencies is critical as we seek to contribute to the amelioration of chronic disease and transform society to improve the human experience.

Chronic, noncommunicable diseases (NCDs) have surpassed acute, infectious diseases as the leading causes of mortality and morbidity globally.1 Heart disease and stroke alone accounted for more than 15 million deaths in 2017.2 The scope and urgency of this threat prompted the United Nations,3 World Health Organization,4 and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention5 to label NCDs an epidemic and issue a call for health professionals to aid in reducing the preventable burden of global mortality and morbidity associated with NCDs.3 , 6 In response, the World Confederation for Physical Therapy and the American Physical Therapy Association (APTA) have released numerous position statements affirming the role physical therapists can and should play in preventing NCDs and promoting health.7–10 Numerous studies have linked movement to mortality,11–13 and physical therapists are well positioned to integrate evidence-based population health, prevention, health promotion, and wellness (PHPW) activities into practice as a means of meeting societal needs and reducing the global burden of NCDs.

Population health has been defined as “the health outcomes of a group of individuals, including the distribution of such outcomes within the group”14 and an approach that “focuses on interrelated conditions and factors that influence the health of populations over the life course, identifies systematic variations in their patterns of occurrence, and applies resulting knowledge to develop and implement policies and actions to improve the health and well-being of populations.15 Prevention generally refers to efforts aimed at avoiding, arresting, or reversing disease processes while health promotion refers to the process of empowering individuals and communities to increase control over their health.16 Wellness has been defined as a “sense that one is living in a manner that permits the experience of consistent, balanced growth in the physical, spiritual, emotional, intellectual, social and psychological dimensions of human existence.”17

To help identify and disseminate best practices in PHPW in the United States, APTA formed the Council for Prevention, Health Promotion, and Wellness in 2018.18 The council is open to all APTA members and works to raise awareness regarding the role of physical therapists and physical therapist assistants in PHPW, provide resources to therapists wishing to integrate PHPW concepts into practice, and foster intersectoral collaborations to catalyze change. One of the council’s first tasks was to survey US-based, entry-level doctor of physical therapy programs to: (1) ascertain the perceived importance of PHPW in entry-level education, (2) describe the delivery of PHPW content in entry-level curricula, and (3) identify factors that facilitate or impede inclusion of PHPW content in entry-level programs. Ninety-eight percent of respondent programs (N = 88) reported including PHPW content in their curricula; however, there was substantial variation regarding the perceived importance of PHPW content as well as the breadth and depth of topics covered. Those PHPW topics included most frequently across programs were the influence of biopsychosocial factors on health, screening and counseling for healthy behaviors, and injury prevention. There was substantial variation regarding the depth of information provided across topics and across programs, ranging from a “brief introduction” to “in-depth discussion.” Factors perceived as impeding both breadth and depth of PHPW content in entry-level curricula centered around limited time, lack of faculty expertise, and unclear competency expectations (under review in Physical Therapy).

To address unclear competency expectations, the council looked to the literature for guidance in establishing entry-level competencies for US-based physical therapist education programs. Competence is defined as the ability to do something successfully, while competencies establish educational expectations with regard to knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes.19 , 20 The First and Second Physical Therapy Summits on Global Health established the role of physical therapists in addressing NCDs and created regional action plans to realize this vision.7 , 8 The Third Summit sought to establish competency standards related to NCD prevention and health promotion for physical therapist practice.21 These standards focused on lifestyle-related behavioral and risk factor assessment and health behavior change interventions.21 , 22 The Association for Prevention Teaching and Research (APTR) published a Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework23 that outlines curricular recommendations for clinical health professions regarding individual and population-oriented prevention and health promotion efforts. This framework, along with various APTA position statements9 , 10 and published works,7 , 8 , 21 , 22 , 24 further informed the council’s work. The purpose of this study was to reach expert consensus in the development of entry-level PHPW competencies for graduates of US-based physical therapist education programs.

Methods

Research Design

This descriptive study employed a modified Delphi method to reach consensus regarding the development of PHPW competencies for graduates on their entry into physical therapist practice. The Delphi method, developed at the Rand Corporation in the 1950s, is an iterative process for reaching consensus among experts on a given topic.25 It has been applied successfully across health professions education, including medicine,26 nursing,27 and physical therapy.28 Advantages of the Delphi method include its iterative nature and anonymity. The iterative process allows participants an opportunity to assess the comments made by other Delphi participants, reflect on their initial judgments, and modify their response accordingly. The ability to provide responses and comments anonymously helps to offset the limitations of in-person discussions, including the dominance of the conversation by a single individual or subgroup of individuals, and pressure to conform to the group.25

Conceptual Framework

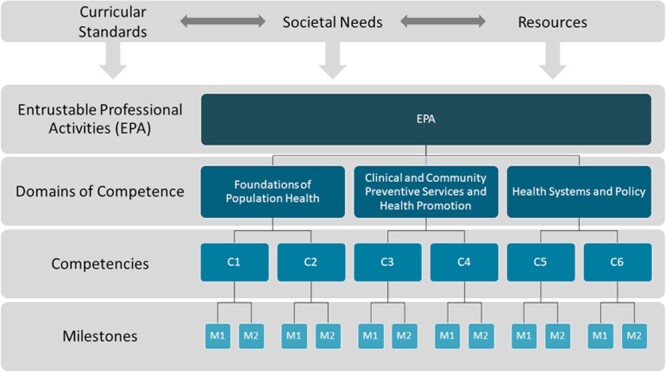

Figure 1 depicts the conceptual framework used to inform development of PHPW competencies for graduates on entry into practice. This framework, adopted from the Accreditation Council for Medical Education29 and others,19 , 20 highlights the interconnectedness of societal needs, curricular standards, and resources and their influence on entrustable professional activities (EPAs), domains of competence and associated competencies, and milestones. EPAs are defined as essential tasks that a professional can perform unsupervised once competence has been demonstrated.30 Domains of competence form the framework for a profession and are comprised of individual competencies.30 Milestones mark individuals’ achievement along a learning or developmental continuum.30 The current study is concerned with the development of entry-level competencies within this framework.

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework.

Participants

Participants were recruited in 4 ways. First, recruitment emails were sent to more than 40 members of APTA’s Council for Prevention, Health Promotion, and Wellness. Second, an announcement was posted to the council’s communication hub. Third, participants were recruited during various programming events at APTA’s 2019 Combined Sections Meeting held in Washington, DC. Finally, snowball sampling was utilized whereby members of the study team and recruited participants were encouraged to recommend individuals perceived as having the requisite expertise in PHPW. Participants were eligible to participate if they were licensed physical therapists with self-identified PHPW expertise in clinical and/or educational settings. The study team was intentional in recruiting and purposefully selecting experts with varied clinical and educational experiences from diverse geographic regions. Individuals who expressed interest in participating were screened based on inclusion criteria and the study team’s desire to have broad representation across settings and geographic regions. Participants were informed in advance regarding the study’s purpose, competency inclusion criteria, and duration as well as the resources used to develop the preliminary list of competencies presented in the Round 1 survey.

Instrumentation

In a traditional Delphi study, expert opinion is sought to develop the Round 1 survey. In this modified Delphi study, a list of competencies for the first round was compiled by the study team from various APTA position statements regarding the role of physical therapists in PHPW,9 , 10 APTA guidelines regarding the minimum required skills of physical therapist graduates at entry level,31 APTA core values,32 Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education (CAPTE) standards and required elements for accreditation of physical therapist education programs,33 the Clinical Prevention and Population Health Curriculum Framework for Health Professionals,23 and Interprofessional Health Promotion Competency Recommendations.24 Incorporating competencies from these resources helped to ensure content validity of the initial survey, which was piloted with 5 physical therapist clinicians and physical therapist educators with experience in PHPW to assess survey feasibility and clarity. Minor changes were made to 5 competencies to improve clarity. No substantive changes were made. The Round 1 survey and subsequent surveys were created in Qualtrics (Provo, UT). The Round 1 survey consisted of 34 competencies, while Round 2 and 3 surveys consisted of 21 and 6 competencies, respectively.

Procedures

Personalized survey links were distributed via Qualtrics to all participants meeting the study’s inclusion criteria. Participants were asked to indicate the perceived relevance of each competency for entry-level physical therapist education (extremely, very, moderately, slightly, or not at all relevant) and to justify their rating with an entry in an open text field. They were also asked to indicate the perceived clarity of each competency (extremely or somewhat clear, neither clear nor unclear, somewhat or extremely unclear) and provide revisions if they did not find the competency to be clear. Finally, participants were instructed to add competencies they perceived as missing and to provide justification for the competency’s inclusion. Data regarding participants’ practice setting, primary area of clinical and/or research expertise, organizational position, degree(s), years of experience, and geographic region also were collected. Participants were given 2 weeks to complete each survey. Reminder emails were sent to participants during this window as needed. Two additional email attempts were made at the close of these 2-week windows to encourage survey completion. On completion of the Round 1 survey, results for each competency were analyzed to determine whether consensus was achieved (see “Analysis” for consensus criteria). If consensus was not achieved for a particular competency, that item was carried forward to the second round. Competencies that achieved consensus but were not perceived as being clear were also carried forward with slight modifications to improve clarity. Finally, new competencies proposed during the first round via open-text responses were moved forward to the second round. The Round 3 survey was developed using the same process described for the Round 2 survey. Approximately 5 weeks elapsed between each survey round. Data were collected over a period of 4 months. Individual responses remained anonymous throughout the study. Approval for this study was obtained through the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board.

Analysis

In the Delphi method, analyses can involve both quantitative and qualitative data. Regarding the analysis of quantitative data, measures of central tendency (eg, mean, median, or mode) and percent agreement were used.25 The use of median scores for Likert-type scales is strongly favored as a measure of central tendency;25 , 34 thus, the first criterion for consensus was a median score of 4 (very relevant) on a 5-point Likert scale. Further literature reviews of the Delphi method suggest levels of agreement are also used to establish consensus, with agreement between 51% and 80% being acceptable.25 , 34 Thus, the second criterion for consensus required that at least 80% of participants perceived the competency as extremely or very relevant. Similar criteria were applied for establishing the clarity of each competency, requiring that at least 70% of participants perceived the competency as being extremely or somewhat clear. Competencies were excluded from further consideration if the percentage of respondents who perceived them as not at all or slightly relevant was greater than the percentage of respondents who perceived them as extremely or very relevant. Participants were provided with median scores and percent agreement for each competency from the previous round. Regarding the analysis of qualitative data, directed content analysis was used to summarize participants’ rationale for accepting or rejecting a competency and refine unclear competencies. Two members of the study team independently reviewed open-text comments and coded commonalities. Summaries of participants’ rationale for accepting or rejecting a competency, and refined competencies were provided in subsequent survey rounds. Coder discrepancies were resolved through consensus of the study team members. Survey rounds continued until consensus and clarity benchmarks were achieved for all competencies.

Results

Participants

Of the 47 individuals who expressed initial interest in the study, none were excluded and 42 accepted a formal invitation to participate via email. These 42 individuals were sent personalized links to the Round 1 survey: 37 participants (88%) completed Round 1 and 2 surveys, and 29 (69%) completed all 3 rounds (Tab. 1). Participants possessed broad expertise across diverse practice settings. Seventy percent (N = 21) of participants were clinicians and/or program faculty representing each geographic region of the United States. Forty-six percent (N = 17) of participants possessed doctorates in physical therapy, and 89% (N = 25) held additional degrees. Finally, participants’ experience related to physical therapist practice and/or education ranged from 0 to 5 years (5%) to 26 years or more (35%).

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Variable | Completed Round 1 Survey (N = 37) | Completed Round 3 Survey (N = 29) |

|---|---|---|

| Clinical and/or research expertise | ||

| Public health, prevention, health promotion | 25 | 21 |

| Geriatrics | 16 | 14 |

| Orthopedics | 12 | 11 |

| Exercise physiology | 8 | 7 |

| Neurology | 7 | 4 |

| Cardiopulmonary | 6 | 5 |

| Biomechanics | 5 | 5 |

| Other | 5 | 3 |

| Pediatrics | 3 | 1 |

| Sports medicine | 3 | 2 |

| Anatomy | 2 | 2 |

| Oncology | 2 | 1 |

| Hand therapy | 0 | 0 |

| Women’s health | 0 | 0 |

| Practice setting | ||

| Academic institution | 19 | 14 |

| Fitness/wellness | 14 | 10 |

| Outpatient | 10 | 8 |

| Other | 9 | 6 |

| Home health | 4 | 4 |

| Rehab/subacute rehab | 4 | 3 |

| Acute care | 3 | 2 |

| Local, state, or federal government | 3 | 3 |

| Skilled nursing | 2 | 2 |

| School/preschool | 2 | 1 |

| Sports medicine | 1 | 1 |

| Industrial, workplace, other occupational environment | 1 | 1 |

| Hospice | 0 | 0 |

| Position within organization | ||

| Clinician | 13 | 11 |

| Faculty | 13 | 10 |

| Other | 9 | 8 |

| Owner | 8 | 8 |

| Chair, division chief, or program director | 4 | 2 |

| Clinic manager | 1 | 1 |

| Geographic region | ||

| Northwest central | 8 | 8 |

| South Atlantic | 8 | 6 |

| Mid-Atlantic | 6 | 4 |

| Northeast central | 3 | 3 |

| Southeast central | 3 | 2 |

| Mountain | 3 | 3 |

| Southwest central | 2 | 1 |

| New England | 1 | 1 |

| Pacific | 1 | 1 |

| Highest clinical degree | ||

| DPT | 17 | 15 |

| MSPT | 9 | 5 |

| BSPT | 6 | 5 |

| Other | 3 | 3 |

| Additional degrees | ||

| PhD | 10 | 8 |

| MS | 6 | 5 |

| MPH | 4 | 4 |

| EdD | 2 | 2 |

| DSc/ScD/DHSc | 2 | 2 |

| MEd | 1 | 1 |

| Years of experience related to physical therapist practice and/or education | ||

| 0–5 | 2 | 2 |

| 6–10 | 5 | 3 |

| 11–15 | 4 | 4 |

| 16–20 | 6 | 5 |

| 21–25 | 7 | 6 |

| 26+ | 13 | 9 |

Surveys

The Round 1 survey contained 34 proposed competencies. Thirteen were accepted as written, 17 failed to achieve consensus and were carried forward to Round 2, and 4 were rejected (Tab. 2). Members of the study team made minor revisions to competencies requiring further clarification (ie, fewer than 70% of participants perceived the competency as clear) and split 1 competency into 2 separate competencies based on participant feedback. Three new competencies were recommended by participants and carried forward to Round 2. The Round 2 survey contained 21 competencies. Six competencies were accepted as written, 6 failed to achieve consensus and were carried forward to Round 3, and 9 competencies were rejected (Tab. 3). Members of the study team made minor clarifying revisions to 3 competencies based on participant feedback. No new competencies were recommended by participants. The Round 3 survey contained 6 competencies, and all 6 competencies were accepted as written (Tab. 2). None of these competencies required further revisions or clarification, and no new competences were recommended by participants. Twenty-five competencies achieved final consensus across 3 broad categories: clinical and community preventive services and health promotion (n = 18), foundations of population health (n = 4), and health systems and policy (n = 3).

Table 2.

Results of Modified Delphi Processa

| Round 1 | Round 2 | Round 3 | Final Competency | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Competency | Median | % Ext or V Relevant | Median | % Ext or V Relevant | Median | % Ext or V Relevant | |

| Clinical and community preventive services and health promotion | |||||||

| Integrate evidence-based prevention and health promotion recommendations with every patient, client, or caregiver as needed | 5 | 94.4% | Yes | ||||

| Recognize individual, family, community, organizational, and societal barriers that impact achievement of optimal health and function | 5 | 94.4% | Yes | ||||

| Implement evidence-based clinic and community-based screenings in accordance with US Preventive Services Taskforce and other nationally recognized agencies | 5 | 66.7 | — | ||||

| Design clinic and community-based screening programs in accordance with evidence-based national and international agencies (eg, US Preventive Services Taskforce, Centers for Disease Control, Special Olympics, WCPT)b | — | — | 4 | 61.1 | |||

| Organize and participate in clinic or community-based screening programs in accordance with evidence-based national and international agencies (eg, US Preventive Services Taskforce, Centers for Disease Control, Special Olympics, WCPT)b | — | — | — | — | 5 | 92.3% | Yes |

| Engage in positive health behaviors in accordance with evidence-based national guidelines | 5 | 91.7% | Yes | ||||

| Recognize risk factors for diseases and the potential impact of these diseases on activities, participation, and quality of life | 5 | 91.7% | Yes | ||||

| Function as a member of an inter-professional team of health professionals, community health workers, public health professionals, and others to reduce disease risk and improve health among individuals and populations | 5 | 88.9% | Yes | ||||

| Communicate nutritional guidelines, set forth by the federal government, to clients as a means of promoting healthy eatingc | — | — | 4 | 69.4% | |||

| Communicate nutritional recommendations set forth by state, national, and international agencies as a means of promoting healthy eating patternsb | — | — | — | — | 5 | 88.5% | Yes |

| Apply evidence-based principles of movement, function, and exercise as a means of promoting physical activity, reducing sedentarism, and improving individual and population health | 5 | 86.1% | Yes | ||||

| Identify community resources and supports for priority health behaviors (active living, healthy eating, injury prevention, stress management, smoking cessation, healthy sleeping, alcohol moderation, and substance-free living) | 5 | 86.1% | Yes | ||||

| Translate medical guidelines and related recommendations in a way that is meaningful to clients, caregivers, and community members | 5 | 75.0% | |||||

| Communicate prevention and health promotion information in a way that recognizes and respects clients’ values, priorities, and communication needsb | — | — | 5 | 86.1% | Yes | ||

| Provide evidence-based education and behavior change strategies in the following APTA and USNPS priority areas: active living, healthy eating, injury prevention, stress management, smoking cessation, healthy sleeping, alcohol moderation, and substance-free living | 5 | 83.3% | Yes | ||||

| Assess your clients’ health literacy and readiness to change and their health-related goals, risks, and assets | 5 | 83.3% | Yes | ||||

| Establish and foster client-centered and inter-professional collaborations that empower individuals and populations | 5 | 80.6% | Yes | ||||

| Recognize that injuries can be prevented by making homes, communities, schools, and worksites safer through the implementation of evidence-based prevention programs and policies | 4 | 69.4% | |||||

| Design evidence-based injury prevention programs to make homes, communities, schools, and worksites saferb | — | — | — | — | 5 | 80.7% | Yes |

| Recognize that priority populations for all prevention and health promotion efforts ought to include individuals and populations experiencing health disparities and individuals and populations experiencing chronic conditions | 4 | 66.7% | |||||

| Consider prioritizing clients who experience health disparities (eg, racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, geographic, gender, disability) and face an increased risk for chronic conditions in prevention and health promotion effortsb | — | — | 4 | 58.3% | |||

| In developing prevention and health promotion programs, attend to the needs of clients who experience health disparities (eg, racial/ethnic, socioeconomic, geographic, gender, disability) as a means of advancing health equityb | — | — | — | — | 5 | 80.7% | Yes |

| Interpret knowledge of the multiple determinants of health and integrate this information into a plan of care | 5 | 72.2% | |||||

| Integrate knowledge of personal and environmental factors into a prevention/health promotion plan of careb | — | — | 5 | 80.1% | Yes | ||

| Integrate evidence-based relaxation strategies (eg, mindfulness, meditation, breathing techniques) to reduce client stress and anxiety as appropriatec , d | — | — | 4 | 77.8% | Yes | ||

| Summarize key constructs underlying behavior change theories and models (eg, Social Cognitive Theory, Theory of Planned Behavior, Transtheoretical Model) and integrate evidence-based behavior change strategies with every patient, client, or caregiver as neededc , d | — | — | 5 | 75.0% | Yes | ||

| Apply principles of client and community engagement to improve individual and population healthe | 4 | 55.6 | No | ||||

| Adapt interventions and programs in a way that reflects the needs, assets, and priorities of the individual or community where they live, work, learn, and play | 5 | 72.2 | |||||

| Design prevention/health promotion programs that reflect the needs, assets, and priorities of clients where they live, work, learn, and playb | — | — | 4 | 45.6% | No | ||

| Facilitate the achievement of goals for function, health, and wellness in clients and communities | 4 | 66.7% | |||||

| Engage clients and communities in the achievement of their goals for function, health, and wellnessb | — | — | 4 | 40.0% | No | ||

| Apply the best available evidence in the design, implementation, and evaluation of community-based health promotion programs | 4 | 61.1% | |||||

| Design a community-based health promotion program using evidence-based frameworks (eg, PRECEDE-PROCEED, RE-AIM)b | — | — | 3 | 36.1% | No | ||

| Work to ensure that existing trans-sectoral policies (health, education, legal, housing, etc.) are in the best interest of our clients and communities | 3 | 27.8 | No | ||||

| Work to ensure that clinical and community services are integrated, available, and mutually reinforcing | 4 | 55.6% | |||||

| Collaborate with clients, health care professionals, and community-based organizations to ensure that prevention and health promotion efforts are integrated and mutually reinforcing (ie, complementary)b | — | — | 4 | 22.2% | No | ||

| Foundations of population health | |||||||

| Define population health and justify the physical therapist’s role in prevention and health promotion | 5 | 94.4% | Yes | ||||

| Recognize the multiple determinants of health (eg, genetics/genomics, healthcare access and quality, individual health behaviors, social and physical environments, policy) and how they interact to influence individual and population health | 5 | 91.7% | Yes | ||||

| Identify key health indicators used to monitor population health in physical therapy practice | 4 | 58.3% | |||||

| Identify key health indicators (eg, physical activity, BMI, educational attainment, income, neighborhood risk) used to monitor population healthb | — | — | 5 | 86.1% | Yes | ||

| Collect and utilize sources of population health data to guide the provision of prevention/health promotion services, inform precision physical therapy, and evaluate outcomes | 3 | 36.1% | |||||

| Access sources of population health data (eg, CDC, County Health Rankings, HealthData.gov) to guide the development of prevention and health promotion services b , d | — | — | 4 | 61.1% | 4 | 75.4% | Yes |

| Health systems and policy | |||||||

| Advocate for the health needs of society | 5 | 94% | Yes | ||||

| Advocate for and promote the integration of physical activity into all levels of education (preschool through higher education) | 4 | 66.7% | |||||

| Advocate for the integration of healthy behaviors into educational and community-based settingsb | — | — | 5 | 82.2 | Yes | ||

| Understand the structure of medical and public health systems and their relationship to non-health sector agencies (eg, education, transportation, legal, housing, etc.) | 4 | 67% | |||||

| Describe the role of health sector (ie, medical and public health systems) and non-health sector (eg, transportation, housing, urban planning, etc.) agencies in increasing or decreasing health vis-à-vis social determinantsb | — | — | 4 | 63 | 4 | 80.8% | Yes |

| Work to ensure the blending of social justice and economic efficiency in the delivery of prevention and health promotion programs | 4 | 53% | |||||

| Consider balancing societal needs and economic efficiency in the delivery of prevention and health promotion programsb | — | — | 3 | 47.2% | No | ||

| Understand the process of policy-making at the organizational, local, state, and federal levels | 4 | 61.1% | |||||

| Summarize the process of prevention/health promotion policy-making at the organizational, local, state, and federal levelsb | — | — | 3 | 47.2% | No | ||

| Support scientific, educational, legislative, organizational, and other policy initiatives that promote healthy behaviors (eg, active living, healthy eating, injury prevention, stress management, smoking cessation, healthy sleeping, alcohol moderation, and substance-free living) and improve individual and population health | 4 | 66.7% | |||||

| Support policy initiatives (educational, organizational, and legislative) that promote individual health behaviorsb | — | — | 3 | 38.9 | No | ||

| Support policy initiatives (educational, organizational, and legislative) that promote healthy communitiesb | — | — | 3 | 41.7% | No | ||

| Advocate for community designs that promote opportunities for safe physical activity and active forms of transportation | 3 | 47.2% | |||||

| Support community designs that promote opportunities for safe physical activity and active transportation for people of all abilitiesb | — | — | 3 | 38.9% | No | ||

| Advocate for the coordination of data and services within and across sectors | 3 | 33.3 | No | ||||

| Define and advocate for the physical therapist’s role within an inter-professional disaster preparedness team | 3 | 8.3% | No | ||||

a APTA = American Physical Therapy Association; BMI = body mass index; CDC = Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; Ext = extremely; USNPS = United States National Prevention Service; V = very WCPT = World Confederation of Physical Therapy.

b Revised competencies based on panel feedback.

c Recommended by participants via Round 2 survey.

d Accepted given that percentage of participants who perceived competency as slightly or not at all relevant was less than 5%.

e Competency perceived as being redundant and therefore was removed.

Table 3.

Referenced CAPTE Elements for Accreditation of Physical Therapist Education Programsa 33

| CAPTE Element | Description |

|---|---|

| 7D11 | Identify, evaluate, and integrate the best evidence for practice with clinical judgment and patient/client values, needs, and preferences to determine the best care for a patient/client |

| 7D14 | Advocate for the profession and the health care needs of society through legislative and political processes |

| 7D19h | Select and competently administer tests and measures appropriate to the patient’s age, diagnosis, and health status, including, but not limited to, those that assess environmental factors |

| 7D20 | Evaluate data from the examination (history, health record, systems review, and tests and measures) to make clinical judgments |

| 7D23 | Determine patient/client goals and expected outcomes within available resources (including applicable payment sources) and specify expected length of time to achieve the goals and outcomes |

| 7D34 | Provide physical therapy services that address primary, secondary, and tertiary prevention; health promotion; and wellness to individuals, groups, and communities |

| 7D39 | Participate in patient-centered interprofessional collaborative practice |

| 7D40 | Use health informatics in the health care environment |

| 7D41 | Assess health care policies and their potential impact on the health care environment and practice |

a CAPTE = Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education.

Eighteen of 25 competencies listed under “preventive services and health promotion” were accepted and 7 were ultimately rejected. Rejected competencies were perceived as relevant to physical therapist practice but exceeding expectations for new graduates. In addition, the community aspect of many of these competencies was perceived as being appropriate for individuals with advanced, post-professional training. Four of 4 competencies listed under “foundations of population health” were accepted. Three of 10 competencies listed under “health systems and policy” were accepted and 7 were rejected. Rejected competencies were perceived by participants as being relevant to physical therapist practice but exceeding expectations for new graduates and general practitioners. In particular, supporting community designs that promote active transportation, advocating for data coordination across sectors, and advocating for physical therapists’ role in disaster preparedness were perceived as specialized competencies requiring advanced, post-professional training. Three rejected competencies (support policy initiatives that promote [1] healthy behaviors and [2] healthy communities; summarize the process of prevention/health promotion policy-making) were perceived as falling under the umbrella of previously accepted competencies (advocate for the health needs of society).

Discussion

Similar to previous efforts to establish entry-level competencies in physical therapist education for emerging or specific areas of practice,19 , 28 , 35 this study utilized a consensus method to establish competencies in the areas of population health, prevention, health promotion, and wellness (PHPW). Of the 34 original competencies derived from key documents and 3 new competencies recommended by study participants, 25 achieved final consensus in 3 broad categories: preventive services and health promotion (n = 18), foundations of population health (n = 4), and health systems and policy (n = 3).

Perhaps not surprisingly, the majority of competencies (18/27) focused on clinical preventive services and health promotion, consistent with more individualized and traditional approaches in physical therapist practice. Competencies within this category loosely align with the following required elements set forth by the CAPTE: 7D11, 7D20, 7D23, 7D34, and 7D39 (Tab. 3).33 Moreover, they align with Dean’s recommendations to establish health competency standards in physical therapist practice related to (1) health and lifestyle behavioral assessments, (2) NCD prevention and health promotion interventions, and (3) behavior change theories and models.21 A number of recommended preventive service and health promotion competencies are notably absent from current CAPTE requirements. These include engaging in positive health behaviors and integrating evidence-based relaxation and behavior change strategies into practice. The APTR recommends that all health professions education programs incorporate preventive services and health promotion content in their curricula, including screening, promoting health behaviors, counseling for behavior change, and understanding what medications are commonly prescribed to address NCDs. Like Dean et al,21 the authors of the current study believe that physical therapists are well positioned to meet societal needs and support the overall health and wellness of every client through the provision of preventive and health promotion services. Physical therapists represent one of the largest, primarily nonpharmacological health professions, and just as they have worked alongside key stakeholders to address the opioid crisis,36 , 37 they have an opportunity and responsibility to leverage their expertise in addressing the NCD epidemic.

The remaining 7 competencies pertained to foundations of population health (n = 4) and health systems and policy (n = 3). Participants shared that achieving APTA’s bold vision of transforming society38 will require not only a commitment to clinical preventive services and health promotion but an even stronger commitment to population health, health systems, and health policy. Recent perspective pieces suggest that population-based approaches to health are gaining traction in physical therapist practice.39 , 40 Moreover, the profession’s public policy priorities for 2020 include population health and the role physical therapists can play in empowering people to live healthy lives through disease prevention and health promotion.41 In recognition of the profession’s and the health care system’s shift toward population health, APTA convened a Population Health Work Group to chart a path for physical therapists toward practical, meaningful, and sustainable solutions that improve the health of individuals and populations.42 Participants, reflecting these recent trends, endorsed the need for graduates of entry-level programs to define population health, recognize how multiple determinants of health interact to influence health, identify key health indicators used to monitor population health, and access sources of population health data to guide prevention and health promotion efforts. These competencies loosely align with the following required elements set forth by CAPTE: 7D11, 7D19h, and 7D40.33 Surprisingly, the term “population health” does not appear in CAPTE standards for the accreditation of physical therapist education programs,33 though it does appear in accreditation standards for other health professions.43 APTR recommends that all health professions’ education programs incorporate population health content in their curricula, including describing the health of populations, understanding the influence of multiple determinants on health (eg, social, cultural, environmental, and political), collecting and using population-level data, integrating population-based approaches in clinical practice, implementing disease prevention and health promotion interventions, and partnering with the public to improve health.23

In contrast to accepting all foundations of population health competencies, Delphi participants’ beliefs regarding physical therapists’ critical role in health systems and policy did not translate into their acceptance of a majority of health system and policy competencies. Participants perceived 5 rejected competencies as being relevant to physical therapist practice but beyond entry-level, and perceived 2 rejected competencies (support policy initiatives that support [1] healthy behaviors and [2] healthy communities) as duplicating a previously accepted competency: advocate for the health needs of society. This competency aligns with CAPTE element 7D14: advocate for the profession and the health care needs of society through legislative and political processes. The second competency accepted in this category encourages new graduates to promote healthy behaviors in educational and community-based settings. The final competency accepted in this category expands CAPTE element 7D41 by drawing our attention to the social determinants of health and reminding us of our professional responsibility to (1) understand how societal issues influence health and well-being, (2) promote social policies that improve health, and (3) ensure that existing social policies are in the best interest of our clients.32 , 44 APTR recommends that all health professions’ education programs incorporate health systems and policy content in their curricula, including the organization of clinical and public health systems, health services financing, clinical and public health workforce, and health policy processes.

This study has several limitations worth noting. First, physical therapists who volunteered to participate in the study were self-identified “experts” in PHPW, and no attempt was made to verify their level of expertise. Given the scope of PHPW topics, it is difficult, if not impossible, for physical therapists to be experts in all areas of PHPW, calling into question participants’ ability to accurately judge the relevance of competencies across all domains. Second, although the authors did not assess APTA membership, it is likely that the vast majority of participants were APTA members at the time of the study. Approximately one-third of US-based physical therapists are APTA members; therefore, the sample may not be representative of all physical therapists in the United States. Third, while participants represented diverse practice settings and geographical regions, the relevance of the final competencies within specific settings and regions may vary. Such analyses were beyond the scope of this particular study. Fourth, 29 of 42 participants (69.0%) completed all 3 rounds of the study; however, this level of retention is in line with similar Delphi studies completed in nursing and occupational therapy.45 , 46

Conclusion

This is the first study, to our knowledge, to establish consensus-based competencies in the areas of PHPW for entry-level physical therapist education in the United States. Adoption of the 25 accepted competencies should promote consistency across physical therapist education programs and help guide physical therapist educators as they seek to integrate PHPW content into entry-level curricula. To ease integration, recommended competencies are organized by category and listed in order of perceived relevance to entry-level physical therapist practice. Future efforts to structure and assess the integration of competencies (knowledge, skills, values, and attitudes) among entry-level graduates will likely involve the development and implementation of EPAs, the critical activities that bridge the gap between entry-level competencies and advanced clinical practice.20 , 47

Contributor Information

Dawn M Magnusson, Physical Therapy Program, University of Colorado Anschutz Medical Campus, Education 2 South, Mailstop C244, 13121 East 17th Avenue, Aurora, CO 80045 (USA).

Zachary D Rethorn, Doctor of Physical Therapy Division, Duke University, Durham, North Carolina.

Elissa H Bradford, Physical Therapy Program, Doisy College of Health Sciences, Saint Louis University, Saint Louis, Missouri.

Jessica Maxwell, Department of Physical Therapy, Movement and Rehabilitation Sciences, Northeastern University, Boston, Massachusetts.

Mary Sue Ingman, Physical Therapy Program, Henrietta Schmoll School of Health, St Catherine University, St Paul, Minnesota.

Todd E Davenport, Physical Therapy Program, University of the Pacific, Stockton, California.

Janet R Bezner, Department of Physical Therapy, Texas State University, Round Rock, Texas.

Author Contributions

Concept/idea/research design: D.M. Magnusson, E.H. Bradford, J. Maxwell, M.S. Ingman, T. Davenport, J. Bezner

Writing: D.M. Magnusson, Z.D. Rethorn, E.H. Bradford, J. Maxwell, T. Davenport, J. Bezner

Data collection: D.M. Magnusson, Z.D. Rethorn, E.H. Bradford

Data analysis: D.M. Magnusson, Z.D. Rethorn, E.H. Bradford, J. Maxwell, M.S. Ingman

Project management: D.M. Magnusson

Providing participants: D.M. Magnusson, J. Bezner

Consultation (including review of manuscript before submitting): Z.D. Rethorn, T. Davenport

Funding

There are no funders to report for this study.

Disclosures

The authors completed the ICMJE Form for Disclosure of Potential Conflicts of Interest and reported no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1. The top 10 causes of death. World Health Organization; website. http://www.who.int/news-room/fact-sheets/detail/the-top-10-causes-of-death. 2018. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2. Roth G, Murray CJL Naghavi M Global development goals causes of death collaborators . Global, regional, and national age-sex-specific mortality for 282 causes of death in 195 countries and territories, 1980-2017: a systematic analysis for the global burden of disease study 2017. Lancet. 2018;392:1736–1788. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Beaglehole R, Bonita R, Horton R, et al. Priority actions for the non-communicable disease crisis. Lancet. 2011;377:1438–1447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Global non-communicable disease action plan 2013–2020. World Health Organization; website. https://www.unscn.org/en/news-events/recent-news?idnews=1420. 2013. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 5. About global noncommunicable diseases. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; website. https://www.cdc.gov/globalhealth/healthprotection/ncd/about.html. 2017. Accessed July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 6. Geneau R, Stuckler D, Stachenko S, et al. Raising the priority of preventing chronic diseases: a political process. Lancet. 2010;376:1689–1698. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Dean E, Al-Obaidi S, De Andrade A, et al. The first physical therapy summit on Global Health: implications and recommendations for the 21st century. Physiother Theory Pract. 2011;27:531–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Dean E, De Andrade A, O'Donoghue G, et al. The second physical therapy summit on Global Health: developing an action plan to promote health in daily practice and reduce the burden of non-communicable diseases. Physiother Theory Pract. 2014;30:261–275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Health priorities for populations and individuals. American Physical Therapy Association; website. https://www.apta.org/apta-and-you/leadership-and-governance/policies/health-priorities-populations-individuals. 2015. Accessed July 1, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10. Physical therapist's role in prevention, wellness, fitness, health promotion, and management of disease and disability . American Physical Therapy Association; website. https://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/Practice/PTRoleAdvocacy.pdf. 2016. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Barreto de Brito LB, Ricardo DR, Soares de Araujo DSM, Ramos PS, Myers J, Soares de Araujo CG. Ability to sit and rise from the floor as a predictor of all-cause mortality. Prev Cardiol. 2014;21:892–898. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Pavasini R, Guralnik J, Brown JC, et al. Short physical performance battery and all-cause mortality: systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Med. 2016;14:215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Celis-Morales CA, Gray S, Petermann F, et al. Walking pace is associated with lower risk of all-cause and cause-specific mortality. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2019;51:472–480. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Kindig D, Stoddart G. What is population health? Am J Public Health. 2003;93:380–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Dunn JR, Hayes MV. Toward a lexicon of population health. Can J Public Health. 1999;November–December:S7–S10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. The Ottawa Charter for Health Promotion. World Health Organization; website. http://www.who.int/healthpromotion/conferences/previous/ottawa/en/. 2019. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Adams T, Bezner J, Steinhardt M. The conceptualization and measurement of perceived wellness: integrating balance across and within dimensions. Am J Health Promot. 1997;11:208–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Council on Prevention, Health Promotion, and Wellness. American Physical Therapy Association; website. http://www.apta.org/PHPW/. 2018. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 19. Rapport MJ, Furze J, Martin K, et al. Essential competencies in entry-level pediatric physical therapy education. Pediatr Phys Ther. 2014;26:7–18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chesbro SB, Jensen GM, Boissonnault WG. Entrustable professional activities as a framework for continued professional competence: is now the time? Phys Ther. 2018;98:3–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Dean E, Skinner M, Myezwa H, et al. Health competency standards in physical therapist practice. Phys Ther. 2019;99:1242–1254. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Dean E, Greig A, Murphy S, et al. Raising the priority of lifestyle-related non-communicable diseases in physical therapy curricula. Phys Ther. 2016;96:940–948. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Allan J, Barwick TA, Cashman S, et al. Clinical prevention and population health: curriculum framework for health professions. Am J Prev Med. 2004;27:471–476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dean E, Moffat M, Skinner M, Dornelas de Andrade A, Myezwa H, Söderlund A. Toward core inter-professional health promotion competencies to address the non-communicable diseases and their risk factors through knowledge translation: curriculum content assessment. BMC Public Health. 2014;14:717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hsu CC, Sandford BA. The Delphi technique: making sense of consensus. Pract Assess Res Eval. 2007;12:1–8. [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shaughnessy AF, Sparks J, Cohen-Osher M, Goodell KH, Sawin GL, Gravel J. Entrustable professional activities in family medicine. J Grad Med Educ. 2013;5:112–118. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. van Houwelingen CT, Moerman AH, Ettema RG, Kort HS, Ten Cate O. Competencies required for nursing telehealth activities: a Delphi-study. Nurse Educ Today. 2016;39:50–62. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Erickson M, Faeth J, Gaston PB, et al. Hand therapy content for entry-level physical therapist education: a consensus-based study. J PT Education. 2017;31:79–89. [Google Scholar]

- 29. Milestones. Accreditation Council for Graduate Medical Education; website. https://www.acgme.org/. 2018. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 30. Englander R, Frank JR, Carraccio C, et al. Toward a shared language for competency-based medical education. Med Teach. 2017;39:582–587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Minimum required skills of physical therapist graduates at entry-level. American Physical Therapy Association; website. https://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/BOD/Education/MinReqSkillsPTGrad.pdf. 2005. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 32. Core values for the physical therapist and physical therapist assistant. American Physical Therapy Association; website. https://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/Ethics/CoreValuesEndorsement.pdf. 2019. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 33. Standards and required elements for accreditation of physical therapist education programs. Commission on Accreditation in Physical Therapy Education; website. http://www.capteonline.org/uploadedFiles/CAPTEorg/About_CAPTE/Resources/Accreditation_Handbook/CAPTE_PTStandardsEvidence.pdf. 2017. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 34. Hasson F, Keeney S, McKenna H. Research guidelines for the Delphi survey technique. J Adv Nurs. 2000;32:1008–1015. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Myezwa H, Stewart A, Solomon P, Becker P. Topics on HIV/AIDS for inclusion into a physical therapy curriculum: consensus through a modified delphi technique. J PT Education. 2012;26:50–56. [Google Scholar]

- 36. Mintken PE, Moore JR, Flynn TW. Physical therapists’ role in solving the opioid epidemic. J Orthopedic and Sports PT. 2018;48:349–353. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Sun E, Moshfegh J, Rishel CA, Cook CE, Goode AP, George SZ. Association of early physical therapy with long-term opioid use among opioid-naive patients with musculoskeletal pain. JAMA Netw Open. 2018;1:e185909. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Vision statement for the physical therapy profession. American Physical Therapy Association; website. http://www.apta.org/Vision/. 2013. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 39. Giuffre S, Domholdt E, Keehan J. Beyond the individual: population health and physical therapy. Physiother Theory Pract. 2018;1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Magnusson DM, Eisenhart M, Gorman I, Kennedy VK, E Davenport T. Adopting population health frameworks in physical therapist practice, research, and education: the urgency of now. Phys Ther. 2019;99:1039–1047. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. 2019–2020 Public policy priorities. American Physical Therapy Association; website. https://www.apta.org/FederalIssues/PublicPolicyPriorities/Document/. 2019. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Stout S, Loehrer S, Cleary-Fishman M, et al. Pathways to population health: an invitation to health care change agents. IHI; website. http://www.ihi.org/Topics/Population-Health/Documents/PathwaystoPopulationHealth_Framework.pdf. 2017. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 43. 2018 Accreditation Council for Occupational Therapy Education (ACOTE®) Standards and interpretive guide (effective July 31, 2020). American Occupational Therapy Association; website. https://www.aota.org/~/media/Corporate/Files/EducationCareers/Accredit/StandardsReview/2018-ACOTE-Standards-Interpretive-Guide.pdf. 2018. Accessed March 21, 2020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Professionalism in physical therapy: core values. American Physical Therapy Association; website. http://www.apta.org/uploadedFiles/APTAorg/About_Us/Policies/BOD/Judicial/ProfessionalisminPT.pdf. 2008. Accessed March 21, 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 45. Whitehead D. An international Delphi study examining health promotion and health education in nursing practice, education and policy. J Clin Nurs. 2008;17:891–900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Leclair LL, Ashcroft ML, Canning TL, Lisowski MA. Preparing for community development practice: a Delphi study of Canadian occupational therapists. Can J Occup Ther. 2016;83:226–236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. ten Cate O, Scheele F. Competency-based postgraduate training: can we bridge the gap between theory and clinical practice? Acad Med. 2007;82:542–547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]