Prescription dispensing to children declined by one-quarter in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019; declines were greater for infection-related than chronic disease–related drug classes.

Abstract

BACKGROUND

After the US coronavirus disease 2019 outbreak, overall prescription dispensing declined but then rebounded. Whether these same trends occurred for children is unknown.

METHODS

Using the IQVIA National Prescription Audit, which contains monthly dispensing counts from 92% of US retail pharmacies, we assessed changes in the monthly number of prescriptions dispensed to US children aged 0 to 19 years during 2018–2020. We compared dispensing totals in April to December 2020 and April to December 2019 overall, by drug class, and among drug classes that typically treat acute infections (eg, antibiotics) or chronic diseases (eg, antidepressants).

RESULTS

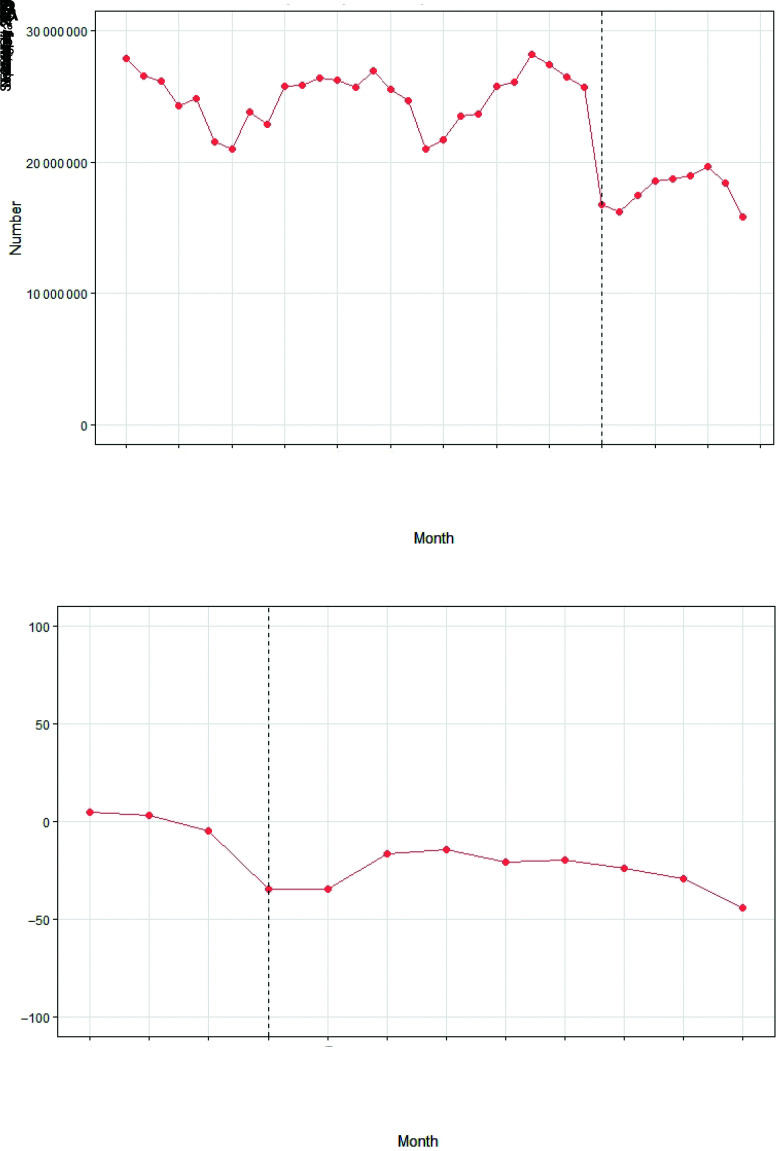

Between January 2018 and February 2020, the median monthly number of prescriptions dispensed to children was 25 744 758. Dispensing totals declined from 25 684 219 to 16 742 568 between March and April 2020, increased to 19 657 289 during October 2020, and decreased to 15 821 914 during December 2020. Dispensing totals during April to December 2020 (160 630 406) were 27.1% lower compared with April to December 2019 (220 284 613). Among the 3 drug classes accounting for the most prescriptions in 2019, the corresponding percentage changes were −55.6% for antibiotics, −11.8% for attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder medications, and 0.1% for antidepressants. Among drug classes that typically treat acute infections and chronic diseases, percentage changes were −51.3% and −17.4%, respectively.

CONCLUSIONS

Prescription dispensing to children declined by one-quarter in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019. Declines were greater for infection-related drugs than for chronic disease drugs. Decreased dispensing of the latter is potentially concerning and warrants further investigation. Whether reductions in dispensing of infection-related drugs are temporary or sustained will be important to monitor going forward.

What’s Known on This Subject:

After the US outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019, overall prescription dispensing declined sharply but then rebounded. Whether these same trends occurred for children is unknown.

What This Study Adds:

The number of prescriptions dispensed to US children during April to December 2020 was 27.1% lower compared with April to December 2019. Among drug classes prescribed for acute infections (eg, antibiotics) and chronic diseases (eg, antidepressants), the percentage changes were −51.3% and −17.4%, respectively.

Prescription drugs are one of the most commonly used medical services among US children. In an analysis of children included in the 2011–2014 NHANES, 21.9% had prescription drug use in the 30 days before the interview.1 Commonly used prescription drugs in children include those prescribed for acute infections, such as antibiotics, as well as those prescribed for chronic disease management, such as antidepressants.1

After the US outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), the total number of prescriptions dispensed to Americans declined sharply and subsequently rebounded to levels that were just 5% below their baseline in 2019.2 However, whether these same trends occurred for children is unknown. Multiple studies indicate that children have experienced greater decreases in outpatient visits during the COVID-19 pandemic than other age groups.3,4 Because outpatient visits represent opportunities for prescribing, prescription drug dispensing to children may not have rebounded to the same degree as it has for the population as a whole. Documenting whether changes in dispensing to children has occurred may be particularly important for drugs that are essential to manage common chronic diseases, such as depression.

The objective of this study was to assess changes in prescription drug dispensing to children after the COVID-19 outbreak, both overall and for drug classes typically prescribed for acute infections and chronic diseases. To achieve this objective, we analyzed 2018–2020 national pharmacy dispensing data. Although previous studies have documented pandemic-related changes in dispensing overall and for specific drugs,2,5–7 this study represents the first to our knowledge to specifically examine changes in dispensing to children.

Methods

Data Sources

We analyzed data from the IQVIA National Prescription Audit (NPA). This database contains monthly counts of prescriptions dispensed from 92% of US retail pharmacies, 70% of mail-order pharmacies, and 70% of pharmacies in long-term care facilities. For retail pharmacies, coverage of chain pharmacies and food stores with pharmacies is more complete than coverage of independent pharmacies. By comparing dispensing totals from included pharmacies with national sales data, IQVIA projects the former so that NPA data are representative of all retail, mail-order, and long-term care pharmacies. Because data were deidentified, the Institutional Review Board of the University of Michigan Medical School exempted this study from review.

In the NPA, age is reported in predefined bands (eg, 0 to 2 years); we defined children as those aged 0 to 19 years. Dispensing channel (retail, mail order, long-term care pharmacy) and payer type are also reported. Payer type is categorized as cash, Medicaid fee for service, Medicare Part D, and third party, a category that includes Medicaid managed care and commercial insurance. IQVIA uses a proprietary system to assign products to 1 of 277 classes (IQVIA minor class). For simplicity, we combined 13 systemic antibiotic classes (eg, penicillins and cephalosporins) into a single class, leaving 265 classes. Of these classes, 232 accounted for at least 1 dispensed prescription to a child between 2018 and 2020. We excluded the class for vaccine prescriptions, leaving 231 classes.

Categorization of Drug Classes

We assigned the 231 drug classes to 1 of 3 categories:

acute infection related, defined as drugs typically prescribed to treat acute viral, bacterial, fungal, or parasitic infections and drugs typically prescribed to treat the symptoms of these infections (eg, cough);

chronic disease related, defined as drugs typically prescribed to treat conditions included in the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm, a validated administrative algorithm for identifying children with chronic diseases8; and

other, including prescriptions for noninfectious chronic diseases not included in the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm (eg, allergic rhinitis, anxiety, migraines), contraceptives, and pain medications.

Two authors (K.C. and A.V.), one a primary care pediatrician and the other a primary care physician dually boarded in internal medicine and pediatrics, independently assigned drug classes to categories. Discrepancies were resolved via consensus. For all 231 drug classes, initial classification decisions were concordant for 211 (91.3%). For the 30 classes accounting for the most prescriptions dispensed to children in 2019, initial decisions were concordant for 29 (97%). Supplemental Table 3 lists drug classes assigned to each category.

Changes After COVID-19 Outbreak

We assessed changes in dispensing in 2 ways. First, we calculated the unadjusted year-over-year percentage change in the number of prescriptions dispensed to children in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019 (ie, dispensing in April to December 2020 minus dispensing in April to December 2019, divided by dispensing in April to December 2019). We similarly calculated the percentage change in dispensing totals in April to August 2020 compared with April to August 2019 and in September to December 2020 compared with September to December 2019. For each month in 2020, we also calculated the year-over-year percentage change in dispensing compared with the same month in 2019. Year-over-year percentage changes are useful when assessing drugs for which dispensing varies by season, such as antibiotics.9 However, if dispensing were already decreasing or increasing before the COVID-19 outbreak, this metric would capture both these trends and any effects of the outbreak.

Consequently, we conducted a second analysis that accounted for prepandemic trends. Specifically, we conducted an interrupted time series analysis, assessing for abrupt level and slope changes in dispensing during April 2020.10 Analyses employed linear segmented regression models using Prais-Winsten estimators with robust SEs.11 Models accounted for first-order autocorrelation and included an indicator for quarter to account for seasonality.

We repeated analyses among subgroups defined by age group, dispensing channel, payer type, and drug class category. We also repeated analyses among the top 30 drug classes in 2019. Among these 30 classes, we identified those with the greatest percentage increases and decreases in dispensing totals in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019. We only assessed the top 30 classes because small absolute changes could translate to large percentage changes for infrequently used drug classes.

Statistical Analysis

To provide context for analyses of pandemic-related changes, we used descriptive statistics to describe prepandemic dispensing to children in 2019. For analyses, we used SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute, Inc, Cary, NC) and R 4.0.1. Two-sided tests were performed; significance was defined as α = .05.

Sensitivity Analysis

To assess whether results would differ substantially when accounting for population growth, we compared the number of dispensed prescriptions per 100 000 US children in April to December 2020 versus April to December 2019. We obtained monthly population denominators using US Census Bureau estimates (see Sensitivity analysis section in the Supplemental Information for details).12

Results

Prescription Drug Dispensing in 2019

The sample included 296 993 253, 299 188 743, and 240 238 895 prescriptions dispensed to children in 2018, 2019, and 2020, respectively. The 299 183 743 prescriptions dispensed to children in 2019 represented 7.2% of the 4 146 930 150 prescriptions dispensed to all age groups during 2019. Of the 299 183 743 prescriptions, children aged 0 to 2, 3 to 9, and 10 to 19 years accounted for 32 989 896 (11.0%), 86 362 416 (28.9%), and 179 836 431 (60.1%), respectively. Retail pharmacies accounted for 288 395 541 (96.4%), whereas third-party payers accounted for 249 331 643 (83.3%). Drug classes categorized as acute infection related, chronic disease related, and other accounted for 86 775 782 (29.0%), 136 055 210 (45.5%), and 76 357 751 (25.5%) of the prescriptions, respectively.

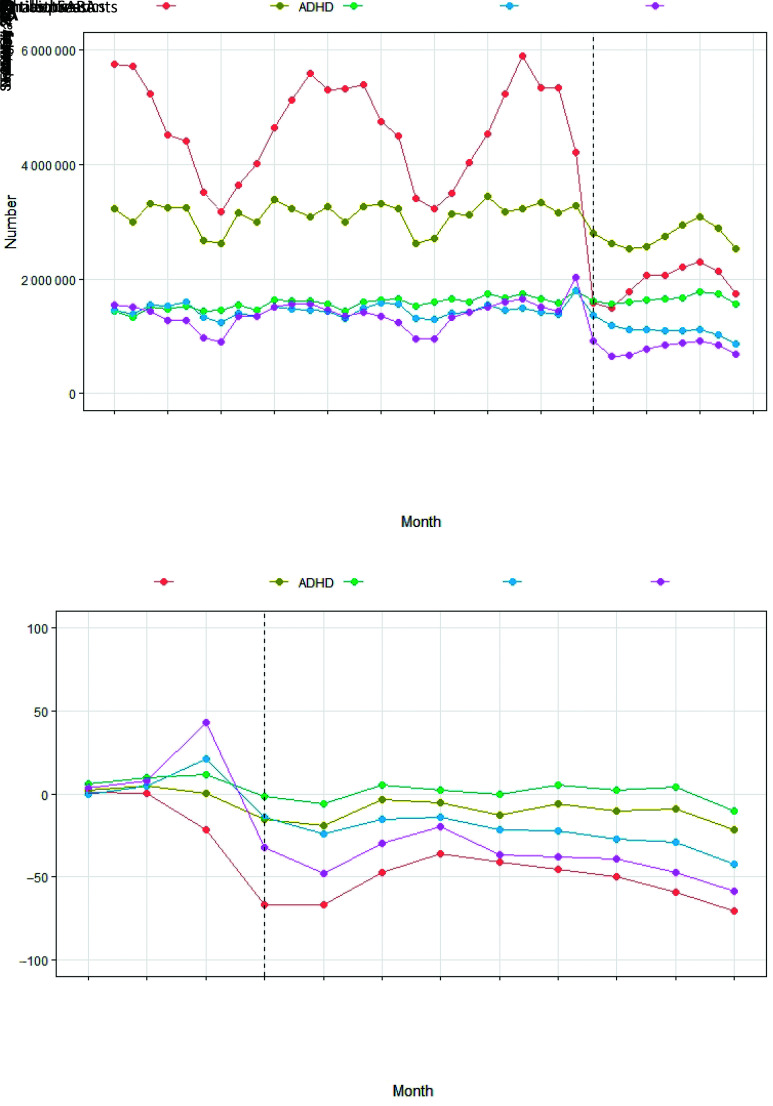

The top 30 drug classes collectively accounted for 91.1% of all prescriptions dispensed to children in 2019. The top 5 classes, which collectively accounted for 48.6% of dispensed prescriptions, were systemic antibiotics (18.4%), attention-deficit/hyperactivity disorder (ADHD) medications (12.5%), antidepressants (6.5%), antiasthmatics (eg, inhaled corticosteroids and montelukast; 5.8%), and inhaled short-acting β-agonists (5.4%). The Additional details section in the Supplemental Information includes additional details on dispensing to children and the estimated per-capita rate of this dispensing in 2019.

Changes in Dispensing After COVID-19 Outbreak

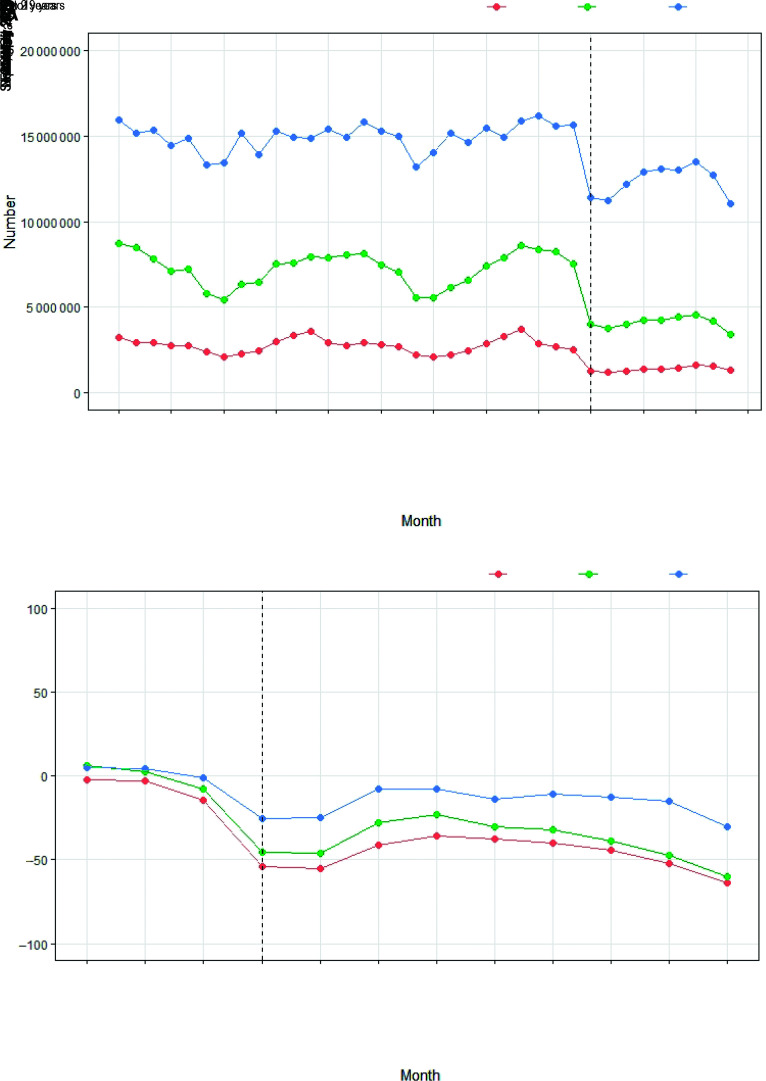

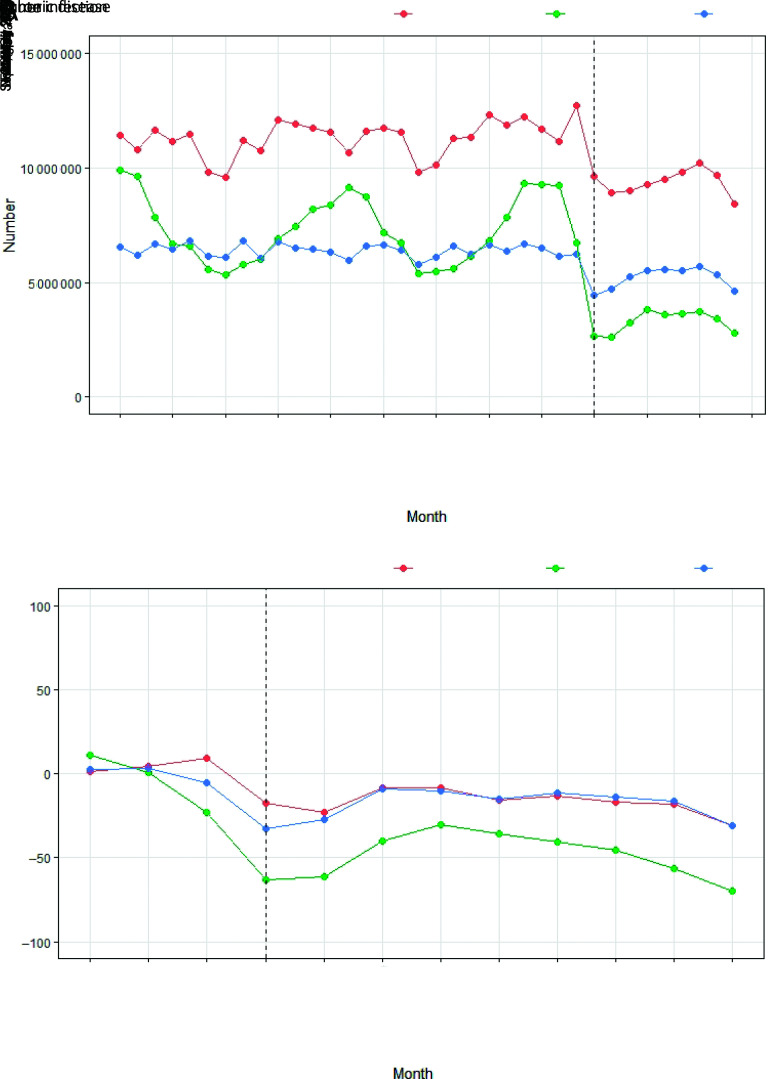

Figures 1A, 2A, 3A, and 4A display dispensing trends overall, among the 3 age subgroups, among the 3 drug class categories, and among the top 5 drug classes in 2019. Figures 1B, 2B, 3B, and 4B display the respective year-over-year percentage changes in dispensing during each month in 2020 compared with the same month in 2019. Table 1 displays year-over-year percentage changes and coefficients for segmented regression models overall and according to age group, channel, and payer type. Table 2 displays the same for the 3 drug class categories and the top 30 drug classes in 2019. Supplemental Tables 6 and 7 contain the raw numbers used to calculate year-over-year percentage changes in Tables 1 and 2.

FIGURE 1.

Changes in overall prescription drug dispensing to US children aged 0 to 19 years after the COVID-19 outbreak, IQVIA NPA. A, Monthly number of prescriptions dispensed during 2018–2020. B, Year-over-year percentage change in dispensing totals between each month in 2020 and the corresponding month in 2019.

FIGURE 2.

Changes in prescription drug dispensing to US children aged 0 to 19 years after the COVID-19 outbreak by age group, IQVIA NPA. A, Monthly number of prescriptions dispensed during 2018–2020. B, Year-over-year percentage change in dispensing totals between each month in 2020 and the corresponding month in 2019.

FIGURE 3.

Changes in prescription drug dispensing to US children aged 0 to 19 years after the COVID-19 outbreak by drug class category, IQVIA NPA. A, Monthly number of prescriptions dispensed during 2018–2020. B, Year-over-year percentage change in dispensing totals between each month in 2020 and the corresponding month in 2019.

FIGURE 4.

Changes in prescription drug dispensing to US children aged 0 to 19 years after the COVID-19 outbreak among the top 5 drug classes in 2019, IQVIA NPA. A, Monthly number of prescriptions dispensed during 2018–2020. B, Year-over-year percentage change in dispensing totals between each month in 2020 and the corresponding month in 2019. SABA, short-acting β-agonist.

TABLE 1.

Changes in Prescription Dispensing to US Children After the COVID-19 Outbreak, Overall and by Age Group, Dispensing Channel, and Payer Type

| Category | No. Prescriptions Dispensed to Children in 2019 (% of the 299 188 743 Prescriptions Dispensed in 2019) | Unadjusted Percentage Changesa | Coefficients From Segmented Regression Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change in Dispensing (April to August 2020 Versus April to August 2019) | % Change in Dispensing (September to December 2020 Versus September to December 2019) | % Change in Dispensing (April to December 2020 Versus April to December 2019) | Intercept | Change per Month Before April 2020 | Level Change in April 2020 | Slope Change in April 2020 | ||

| All drugs | 299 188 743 (100.0) | −24.7 | −29.8 | −27.1 | 26 245 168* | 631 | −5 329 970* | −333 017 |

| Age group, y | ||||||||

| 0–2 | 32 989 896 (11.0) | −45.9 | −51.4 | −48.7 | 2 912 785* | −11 454 | −982 899* | −55 949 |

| 3–9 | 86 362 416 (28.9) | −35.9 | −45.6 | −40.6 | 7 961 025* | −9734 | −2 189 437* | −156 586 |

| 10–19 | 179 836 431 (60.1) | −16.3 | −17.5 | −16.8 | 15 309 540* | 17 706 | −2 356 461* | −67 248 |

| Dispensing channel | ||||||||

| Retail pharmacy | 288 395 541 (96.4) | −25.3 | −30.5 | −27.8 | 25 368 972* | −1624 | −5 321 098* | −319 210 |

| Mail-order pharmacy | 3 771 155 (1.3) | 2.5 | −3.2 | −0.1 | 299 305* | 812* | 21 738 | −6551* |

| Long-term care pharmacy | 7 022 047 (2.3) | −14.9 | −15.1 | −15 | 554 018* | 1188* | −77 108* | −3471 |

| Payer type | ||||||||

| Cash | 11 805 359 (3.9) | −31.7 | −33.3 | −32.5 | 1 184 798* | −6436* | −203 869* | −5633 |

| Medicaid fee for service | 37 351 184 (12.5) | −21.0 | −25.2 | −22.9 | 3 597 933* | −14 964* | −376 888 | −30 261 |

| Medicare | 617 994 (0.2) | −8.1 | −13.2 | −10.6 | 38 165* | 895* | −14 522* | −748 |

| Third partyb | 249 311 643 (83.3) | −25.0 | −30.3 | −27.5 | 21 415 280* | 20 527 | −4 725 316* | −297 281 |

Represents the No. prescriptions dispensed during the period in 2020 minus the No. prescriptions dispensed during the same period in 2019, divided by the No. prescriptions dispensed during the period in 2019. For example, 160 603 406 prescriptions were dispensed to children between April and December 2020, compared with 220 284 613 between April and December 2019. The unadjusted percentage change was (160 603 406 − 220 284 613)/(220 284 613) = −27.1%. The raw Nos. for calculations of percentage changes are included in Supplemental Table 6.

Includes commercial payers and Medicaid managed care.

P < .05.

TABLE 2.

Changes in Prescription Dispensing to US Children After the COVID-19 Outbreak Among the Top 30 Drug Classes in 2019

| Categorya | No. Prescriptions Dispensed to Children in 2019 (% of the 299 188 743 Prescriptions Dispensed in 2019) | Rank Among Top 30 Drug Classes in 2019 | Unadjusted Percentage Changesb | Coefficients From Segmented Regression Models | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| % Change in Dispensing (April to August 2020 Versus April to August 2019) | % Change in Dispensing (September to December 2020 Versus September to December 2019) | % Change in Dispensing (April to December 2020 Versus April to December 2019) | Intercept | Change per Month Before April 2020 | Level Change in April 2020 | Slope Change in April 2020 | |||

| Infection-related drug classes | 86 775 782 (29.0)c | N/A | −47.7 | −55.0 | −51.3 | 8 664 098* | −33 362 | −2 405 033* | −138 928 |

| Antibiotics, systemic | 55 069 670 (18.4) | 1 | −53.6 | −57.4 | −55.6 | 5 255 662* | −23 091 | −1 932 216* | −63 088 |

| Anti-infectives, eye | 5 306 098 (1.8) | 15 | −62.1 | −64.8 | −63.3 | 485 469* | −971 | −232 154* | −6021 |

| Antivirals, influenza | 5 288 284 (1.8) | 16 | −95.0 | −97.5 | −97.0 | 1 144 047* | 4460 | −49 271 | −34 117 |

| Antitussives | 4 566 339 (1.5) | 19 | −79.4 | −76.5 | −77.6 | 537 006* | −98 | −129 088 | −22 199* |

| Antifungals, topical | 4 345 542 (1.5) | 20 | −19.9 | −17.3 | −18.7 | 347 313* | −114 | −73 281* | 1567 |

| Antibiotics, topical | 3 823 282 (1.3) | 22 | −20.9 | −23.7 | −22.1 | 263 804* | 152 | −71 086* | −729 |

| Steroids or anti-infectives, ear | 1 855 130 (0.6) | 29 | −19.3 | −37.0 | −24.9 | 139 075* | −753 | −1594 | −6911 |

| Chronic disease–related drug classes | 136 055 210 (45.5)c | N/A | −15.0 | −20.1 | −17.4 | 11 147 525* | 23 233 | −1 426 780* | −172 199 |

| ADHD | 37 490 152 (12.5) | 2 | −11.8 | −11.7 | −11.8 | 3 175 464* | 2193 | −299 742 | −18 284 |

| Antidepressants | 19 391 873 (6.5) | 3 | −0.1 | 0.3 | 0.1 | 1 397 729* | 10 098* | −86 330 | −5860 |

| Antiasthmatics | 17 252 144 (5.8) | 4 | −17.8 | −30.3 | −23.5 | 1 434 597* | 2367 | −158 616 | −44 166* |

| Inhaled short-acting β-agonists | 16 197 401 (5.4) | 5 | −34.0 | −46.0 | −40.2 | 1 423 413* | 6180 | −413 902* | −47 861* |

| Oral corticosteroids | 9 712 183 (3.2) | 7 | −55.4 | −61.5 | −58.6 | 807 312* | −302 | −391 616* | −16 584 |

| Antiepileptics | 8 434 301 (2.8) | 9 | −4.6 | −7.0 | −5.7 | 664 618* | 780 | −16 278 | −6017 |

| Antipsychotics | 6 308 122 (2.1) | 13 | −1.8 | −4.6 | −3.0 | 488 056* | 1333* | −4394 | −5144 |

| Antiulcerants | 5 988 802 (2.0) | 14 | −30.1 | −20.0 | −25.8 | 542 343* | −3607* | −85 861* | 2594 |

| Human insulins and analogues | 2 015 684 (0.7) | 27 | −4.1 | −10.0 | −6.8 | 154 956* | 496* | −894 | −3352* |

| Thyroid preparations | 1 894 477 (0.6) | 28 | −7.7 | −10.7 | −9.0 | 154 438* | −192 | −3736 | −1592 |

| Other drug classes | 76 357 751 (25.5)c | N/A | −19.3 | −18.3 | −18.9 | 6 453 152* | −7410 | −1 238 776* | 25 423 |

| Contraception, hormonal systemic | 12 531 475 (4.2) | 6 | −6.6 | −9.0 | −7.7 | 949 103* | −322 | −42 499 | −6756 |

| Topical corticosteroids | 9 072 247 (3.0) | 8 | −11.2 | −6.5 | −9.3 | 727 090* | −1057 | −102 214* | 9567 |

| Antihistamines, systemic | 6 673 413 (2.2) | 10 | −18.5 | −25.2 | −21.6 | 505 892* | 3310 | −122 417* | −9842 |

| Antiacne | 6 667 536 (2.2) | 11 | −5.1 | 6.8 | 0.2 | 481 511* | 2512* | −92 390* | 12 244* |

| Nasal corticosteroids without anti-infectives | 6 519 734 (2.2) | 12 | −28.1 | −29.5 | −28.7 | 532 770* | 859 | −179 388* | −943 |

| Serotonin antagonists, antiemetics, antinauseants | 5 279 994 (1.8) | 17 | −55.4 | −58.7 | −57.1 | 489 627* | −857 | −192 892* | −3900 |

| Antirheumatics, nonsteroidal | 4 676 976 (1.6) | 18 | −33.9 | −28.9 | −31.5 | 480 287* | −4044 | −113 007* | 8393 |

| Tranquilizers | 3 870 226 (1.3) | 21 | −1.0 | 0.4 | −0.4 | 287 194* | 1334* | −21 308 | 924 |

| Nonnarcotic analgesics | 3 361 137 (1.1) | 23 | −53.7 | −58.8 | −56.3 | 284 638* | 1299 | −154 205* | −4540 |

| Narcotic analgesics | 2 718 567 (0.9) | 24 | −27.0 | −12.3 | −21.0 | 256 128* | −3039* | −53 509 | 7939 |

| Vitamins and minerals | 2 668 505 (0.9) | 25 | −10.0 | −1.8 | −6.4 | 249 445* | −1332* | −16 262 | 3782 |

| Stomatologicals | 2 361 589 (0.8) | 26 | −15.9 | −2.7 | −10.3 | 178 008* | 494 | −48 980 | 5023 |

| Cardiac stimulants, excluding cardiac glycosides | 1 444 083 (0.5) | 30 | −30.1 | −8.0 | −21.5 | 91 079* | 5 | −55 980* | 6211* |

N/A, not applicable.

Antidepressants include drugs such as selective serotonin or norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors. Antiasthmatics include drugs such as inhaled corticosteroids and montelukast. Antiulcerants include H2 blockers and proton pump inhibitors. Antirheumatics (nonsteroidal) include drugs such as ibuprofen and naproxen. Serotonin antagonists and antiemetics includes drugs such as ondansetron. Tranquilizers include benzodiazepines; these drugs were not considered to be chronic disease related by our definition because anxiety is not included in the Pediatric Medical Complexity Algorithm. Stomatologicals include drugs such as benzocaine and chlorhexidine. Thyroid preparations include drugs such as levothyroxine. Cardiac stimulants, excluding cardiac glycosides, include epinephrine autoinjectors.

Represents the No. prescriptions dispensed during the period in 2020 minus the No. prescriptions dispensed during the same period in 2019, divided by the No. prescriptions dispensed during the period in 2019. The raw Nos. for calculations of percentage changes are included in Supplemental Table 7.

Because only the top 30 drug classes in 2019 are shown, the percentage of dispensed prescriptions accounted for by each drug class category does not equal the sum of the percentages accounted for by the listed drug classes in the category.

P < .05.

During January 2018 to February 2020, the monthly number of prescriptions dispensed to children ranged between 20 988 338 and 28 227 877 (median: 25 744 758). Dispensing totals varied by season, with nadirs in June and July and peaks in January. Between March and April 2020, dispensing totals decreased by 8 941 651, from 25 684 219 to 16 742 568. Dispensing totals subsequently rebounded, reaching 19 657 289 during October 2020. These totals then decreased to 15 821 914 during December 2020, a level below that during April 2020 (Fig 1A). Dispensing totals were 27.1% lower in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019, 24.7% lower in April to August 2020 compared with April to August 2019, and 29.8% lower in September to December 2020 compared with September to December 2019. In segmented regression models, the COVID-19 outbreak was associated with an abrupt drop of 5 329 970 dispensed prescriptions (P < .001) and a negative but nonsignificant slope change in dispensing totals (−333 017 prescriptions per month; P = .23) (Table 1).

In April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019, dispensing totals for children aged 0 to 2 years, 3 to 9 years, and 10 to 19 years decreased 48.7%, 40.6%, and 16.8%, respectively. Dispensing totals for retail pharmacies decreased 27.8%, but for mail-order pharmacies, totals decreased just 0.1%. Prescriptions paid with cash experienced the largest relative declines in dispensing totals of all payer types (−32.5%) (Table 1).

In April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019, dispensing totals for acute infection–related drug classes declined by 51.3%. For drug classes categorized as chronic disease related and other, dispensing totals declined by 17.4% and 18.9%, respectively. Among the top 5 drug classes in 2019, declines were −55.6% for antibiotics, −11.8% for ADHD medications, 0.1% for antidepressants, −23.5% for antiasthmatics, and −40.2% for inhaled short-acting β-agonists. Among the top 30 drug classes in 2019, the median percentage change in dispensing totals between April to December 2020 and April to December 2019 was −21.6%. For 28 of the 30 classes, this percentage change was negative. Classes with the greatest percentage decreases were influenza antiviral agents (−97.0%), antitussives (−77.6%), and eye anti-infectives (−63.3%). The 2 classes for which the percentage change was positive were antiacne medications (0.2%) and antidepressants (0.1%). In addition to antidepressants, dispensing of other mental health-related drug classes, including tranquilizers (−0.4%) and antipsychotics (−3.0%), changed minimally.

Sensitivity Analysis

The number of dispensed prescriptions per 100 000 children declined −27.5% between April to December 2020 and April to December 2019, compared to −27.1% when considering the number of dispensed prescriptions (Sensitivity analysis section in the Supplemental Information).

Discussion

This study provides a national picture of prescription drug dispensing to US children before and during the COVID-19 pandemic. Findings indicate that this dispensing declined sharply in April 2020, increased through October 2020, and declined to levels that were lower than in April 2020 by the end of 2020. Dispensing totals during April to December 2020 were 27.9% lower than those during April to December 2019. Declines in dispensing were greater for drug classes typically prescribed for acute infections than for classes typically prescribed for chronic disease management.

The decline in dispensing of infection-related drugs is consistent with studies revealing large decreases in pediatric office and emergency department visits for infections.3,13,14 For some of these drugs, declines in dispensing may be welcome given their potential harms and lack of efficacy. For example, antitussive drugs, for which dispensing declined 77.6% in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019, are ineffective in pediatric patients and are associated with serious side effects in young children.15,16 From the perspective of health care quality, the sharp decline in dispensing of these medications may represent a silver lining of the COVID-19 pandemic.

Interpreting the 55.6% decline in antibiotic dispensing to children requires some caution. This decline would be concerning if it reflected delays in seeking care for serious infections, potentially leading to morbidity or even mortality. Although possible, evidence supporting this notion is scant. If delayed diagnoses of serious infections were prevalent, one might expect to see increases in hospitalizations for such infections. Yet analyses have revealed dramatic decreases in pediatric admissions for infections and for acute respiratory failure during 2020.17,18

A more likely explanation is that the sharp declines in antibiotic dispensing reflects reductions in the incidence of infections due to COVID-19 risk–mitigation measures, such as social distancing measures and face covering use.13,19 Reduced incidence of infections would lead to fewer visits and opportunities for antibiotic prescribing, whether for antibiotic-appropriate conditions, such as strep throat, or for antibiotic-inappropriate conditions, such as acute upper respiratory infection.20–22 The resulting decrease in antibiotic exposure, in turn, would reduce the incidence of antibiotic-related adverse events and slow the spread of antimicrobial resistance,23 developments that could also be seen as a silver lining of the pandemic.

Dispensing of infection-related drugs to children could rebound if social distancing measures are lifted and the incidence of infection increases. However, dispensing of these drugs may not necessarily return to prepandemic levels, at least not in the short-term. For example, if COVID-19 risk–mitigation measures continue in schools and day cares, this may lower the incidence of conditions for which antibiotics are frequently prescribed, such as otitis media, sinusitis, and upper respiratory infections.20,22 Additionally, barriers to accessing pediatric outpatient care during the pandemic may have forced some parents to adopt a de facto watchful waiting strategy when their children developed acute infections, which, in turn, could increase their comfort with this strategy going forward. These possibilities should be explored in future research.

Similar to infection-related drug classes, dispensing of chronic disease–related drug classes to children declined in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019, but to a much lesser degree. Owing to data limitations, interpreting these changes is challenging. For example, data lacked patient-level information on outcomes, such as disease exacerbations, and information on whether dispensing represented new use among patients with incident diagnoses versus continuing use among patients with established diagnoses. Additionally, data lacked information on days supplied. Unlike infection-related drugs, which typically are intended for one-time use, increased dispensing of chronic disease drugs may represent stockpiling due to concerns about future medication access, whereas decreased dispensing could reflect shifts to fewer but larger prescriptions (eg, a 90-day instead of a 30-day supply). As potential evidence that such shifts occurred, the number of prescriptions dispensed in mail-order pharmacies, which often provide 90-day drug supplies, changed little between April to December 2019 and April to December 2020. In contrast, dispensing in retail pharmacies declined by 27.8%.

To illustrate the difficulty of interpreting changes in dispensing of chronic disease drugs, consider antidepressants, for which dispensing changed little after the COVID-19 outbreak. An optimistic view is that this finding suggests few children on established antidepressant regimens discontinued use. However, studies suggest that the mental health of children has worsened during the pandemic, particularly among adolescents.24–26 Consequently, findings may indicate that antidepressant dispensing has not risen to meet increased need.

As another example, consider the 10.8% decrease in dispensing for ADHD medications in April to December 2020 compared with April to December 2019. This may reflect reduced overall need for medications among children with ADHD and/or reduced need to have ADHD medications at school given the transition to remote learning in many localities. However, declines in dispensing may also reflect disruptions in medication access among children with ADHD or decreased opportunities to detect new cases.27

To better understand pandemic-related changes in pediatric chronic disease drug use, research using alternative data sources is needed. For example, electronic health record data can be used to identify decreases in the frequency of refill requests among children on established drug regimens for chronic disease. For children with such decreases, clinicians could contact families to determine if there is reason for concern (eg, medications were not affordable) or not (eg, improved disease control). As another example, insurance claims databases can be used to assess changes in incident diagnoses of chronic diseases and evaluate the association between changes in chronic disease drug use and disease exacerbations.

In subgroup analyses, dispensing totals declined more precipitously among young children aged 0 to 9 years compared with older children aged 10 to 19 years. This difference may partly be driven by declines in antibiotic dispensing. Because young children have a higher rate of antibiotic use than older children,28 declines in antibiotic dispensing might affect overall dispensing totals to a greater degree in young children.28 Dispensing totals also declined more sharply for prescriptions paid with cash than for other payer types. This finding is unlikely to reflect increased insurance coverage among children considering that pandemic-related job losses have likely increased the number of children who are uninsured.29 A potential explanation is that children who were already uninsured were even more likely to face cost-related barriers to accessing drugs because of increased family financial hardship during the pandemic.

Dispensing to children declined sharply in November to December 2020. According to IQVIA, dispensing to adults similarly declined (A. Campbell, MS, personal communication, 2021). Potential explanations include the surge in COVID-19 cases at the end of 2020,30 which may have deterred families for seeking care for children. The decline during November to December 2020 highlights the importance of monitoring prescription dispensing to children in future research.

This study has several strengths. First, we used a national all-payer database that captures the vast majority of US dispensing. Second, we provide timely data through the end of 2020. Finally, we provide the most recent national data on pediatric drug use. Unlike previous studies on this topic that relied on self-reported survey data,1 we report objectively measured dispensing data.

Despite these strengths, this study has limitations. First, as noted above, analyses were limited by lack of information on clinical outcomes, days supplied, disease severity, and whether dispensing reflected new versus ongoing use. Second, categorization of drug classes employed a consensus-based approach, and heterogeneity in indication among drugs within classes is possible. Notably, however, the 2 raters agreed on the vast majority of initial classification decisions for the top 30 drug classes in 2019. Finally, a small number of pharmacies were not captured by our database. However, as discussed above, dispensing counts are projected so that they are representative of all US retail, mail-order, and long-term care pharmacies.

Conclusions

Decreased dispensing of chronic disease drugs to children during the pandemic is potentially concerning and warrants further investigation. On the other hand, declines in dispensing of infection-related drugs, such as antitussives and antibiotics, may be welcome developments. These declines reveal that substantial reductions in prescribing of these drugs are possible. Whether these reductions are temporary or sustained will be important to monitor going forward.

Glossary

- ADHD

attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder

- COVID-19

coronavirus disease 2019

- NPA

National Prescription Audit

Footnotes

FINANCIAL DISCLOSURE: The authors have indicated they have no financial relationships relevant to this article to disclose.

FUNDING: A portion of the data were provided through the IQVIA Institute’s Human Data Science Research Collaborative, the purpose of which is to promote research on the effects of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on US health care. The remainder of the data were provided through additional support from the IQVIA Institute. Dr Chua’s effort is supported by a career development award from the National Institute on Drug Abuse (1K08DA048110-01). The funders played no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. Funded by the National Institutes of Health (NIH).

POTENTIAL CONFLICT OF INTEREST: The authors have indicated they have no potential conflicts of interest to disclose.

Dr Chua conceptualized and designed the study, collected the data, analyzed and interpreted the data, drafted the initial manuscript, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Volerman conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, and reviewed and revised the manuscript; Dr Conti conceptualized and designed the study, analyzed and interpreted the data, reviewed and revised the manuscript, and provided study supervision; and all authors approved the final manuscript as submitted and agree to be accountable for all aspects of the work.

References

- 1. Hales CM, Kit BK, Gu Q, Ogden CL. Trends in prescription medication use among children and adolescents-United States, 1999-2014. JAMA. 2018;319(19):2009–2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Symphony Health . COVID-19 weekly trend insights: compiled on 11/20/2020. 2020. Available at: https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/prahs-symphony-health/resources/COVID-19-Insights-11-20-2020-FINAL.pdf?mtime=20201124150003&focal=none. Accessed December 15, 2020

- 3. Symphony Health . COVID-19 weekly trend insights: compiled on 12/4/2020. 2020. Available at: https://s3.us-east-1.amazonaws.com/prahs-symphony-health/resources/COVID-19-Insights-12-4-2020-FINAL.pdf?mtime=20201215104218&focal=none. Accessed December 15, 2020

- 4. Mehrotra A, Chernew M, Linetsky D, Hatch H, Cutler D, Schneider EC. The impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on outpatient care: visits return to prepandemic levels, but not for all providers and patients. 2020. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/2020/oct/impact-covid-19-pandemic-outpatient-care-visits-return-prepandemic-levels. Accessed November 1, 2020

- 5. Nguyen TD, Gupta S, Ziedan E, et al. Assessment of filled buprenorphine prescriptions for opioid use disorder during the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic. JAMA Intern Med. 2021;181(4):562–565 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Buehrle DJ, Nguyen MH, Wagener MM, Clancy CJ. Impact of the coronavirus disease 2019 pandemic on outpatient antibiotic prescriptions in the United States. Open Forum Infect Dis. 2020;7(12):ofaa575. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Huskamp HA, Busch AB, Uscher-Pines L, Barnett ML, Riedel L, Mehrotra A. Treatment of opioid use disorder among commercially insured patients in the context of the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA. 2020;324(23):2440–2442 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Simon TD, Cawthon ML, Stanford S, et al. ; Center of Excellence on Quality of Care Measures for Children with Complex Needs (COE4CCN) Medical Complexity Working Group . Pediatric medical complexity algorithm: a new method to stratify children by medical complexity. Pediatrics. 2014;133(6). Available at: www.pediatrics.org/cgi/content/full/133/6/e1647 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Suda KJ, Hicks LA, Roberts RM, Hunkler RJ, Taylor TH. Trends and seasonal variation in outpatient antibiotic prescription rates in the United States, 2006 to 2010. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 2014;58(5):2763–2766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Penfold RB, Zhang F. Use of interrupted time series analysis in evaluating health care quality improvements. Acad Pediatr. 2013;13(6, suppl):S38–S44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Davidson R, MacKinnon JG. Estimation and Inference in Econometrics. New York, NY: Oxford University Press; 1993 [Google Scholar]

- 12. US Census Bureau . Table 1. Monthly population estimates for the United States: April 1, 2010 to December 1, 2020 (NA-EST2019-01). 2020. Available at: https://www2.census.gov/programs-surveys/popest/tables/2010-2019/national/totals/na-est2019-01.xlsx. Accessed October 1, 2020

- 13. Hatoun J, Correa ET, Donahue SMA, Vernacchio L. Social distancing for COVID-19 and diagnoses of other infectious diseases in children. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020006460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Pines JM, Zocchi MS, Black BS, et al. ; US Acute Care Solutions Research Group . Characterizing pediatric emergency department visits during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am J Emerg Med. 2021;41:201–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Schaefer MK, Shehab N, Cohen AL, Budnitz DS. Adverse events from cough and cold medications in children. Pediatrics. 2008;121(4):783–787 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Smith SM, Schroeder K, Fahey T. Over-the-counter (OTC) medications for acute cough in children and adults in community settings. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2014;(11):CD001831. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Pelletier JH, Rakkar J, Au AK, Fuhrman D, Clark RSB, Horvat CM. Trends in US pediatric hospital admissions in 2020 compared with the decade before the COVID-19 pandemic. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4(2):e2037227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Markham JL, Richardson T, DePorre A, et al. Inpatient Use and outcomes at children’s hospitals during the early COVID-19 pandemic. Pediatrics. 2021;147(6):e2020044735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Olsen SJ, Azziz-Baumgartner E, Budd AP, et al. Decreased influenza activity during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, Australia, Chile, and South Africa, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(37):1305–1309 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Chua KP, Fischer MA, Linder JA. Appropriateness of outpatient antibiotic prescribing among privately insured US patients: ICD-10-CM based cross sectional study. BMJ. 2019;364:k5092. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Chua KP, Linder JA. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescribing by antibiotic among privately and publicly insured non-elderly US patients, 2018 [published online ahead of print October 1, 2020]. J Gen Intern Med. doi:10.1007/s11606-020-06189-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Fleming-Dutra KE, Hersh AL, Shapiro DJ, et al. Prevalence of inappropriate antibiotic prescriptions among US ambulatory care visits, 2010-2011. JAMA. 2016;315(17):1864–1873 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention . Antibiotic Resistance Threats in the United States: 2019. Atlanta, GA: US Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention; 2019 [Google Scholar]

- 24. Leeb RT, Bitsko RH, Radhakrishnan L, Martinez P, Njai R, Holland KM. Mental health-related emergency department visits among children aged <18 years during the COVID-19 pandemic - United States, January 1-October 17, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69(45):1675–1680 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Patrick SW, Henkhaus LE, Zickafoose JS, et al. Well-being of parents and children during the COVID-19 pandemic: a national survey. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020016824. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Gassman-Pines A, Ananat EO, Fitz-Henley J II. COVID-19 and parent-child psychological well-being. Pediatrics. 2020;146(4):e2020007294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Cortese S, Coghill D, Santosh P, Hollis C, Simonoff E; European ADHD Guidelines Group . Starting ADHD medications during the COVID-19 pandemic: recommendations from the European ADHD Guidelines Group. Lancet Child Adolesc Health. 2020;4(6):e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Hicks LA, Bartoces MG, Roberts RM, et al. US outpatient antibiotic prescribing variation according to geography, patient population, and provider specialty in 2011. Clin Infect Dis. 2015;60(9):1308–1316 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Fronstin P., Woodbury SA. How many Americans have lost jobs with employer health coverage during the pandemic? 2020. Available at: https://www.commonwealthfund.org/publications/issue-briefs/2020/oct/how-many-lost-jobs-employer-coverage-pandemic. Accessed February 28, 2021

- 30. Johns Hopkins University and Medicine Coronavirus Resource Center . COVID-19 dashboard. 2020. Available at: https://coronavirus.jhu.edu/map.html. Accessed July 28, 2020