Abstract

Hospital census prediction has well-described implications for efficient hospital resource utilization, and recent issues with hospital crowding due to CoVID-19 have emphasized the importance of this task. Our team has been leading an institutional effort to develop machine-learning models that can predict hospital census 12 hours into the future. We describe our efforts at developing accurate empirical models for this task. Ultimately, with limited resources and time, we were able to develop simple yet useful models for 12-hour census prediction and design a dashboard application to display this output to our hospital’s decision-makers. Specifically, we found that linear models with ElasticNet regularization performed well for this task with relative 95% error of +/− 3.4% and that this work could be completed in approximately 7 months.

Keywords: machine learning, forecasting, hospital census, inpatient

INTRODUCTION

Management of inpatient hospital census and efficient use of hospital resources have been perpetual challenges for hospital leaders worldwide; both have been significantly exacerbated by the CoVID-19 (COVID) pandemic. Specific resource allocation challenges include nurse and ancillary staffing, run time of operating theaters and radiology equipment, and hospital bed allocation, among many others. Accordingly, the prediction of patient census, also known as “inventory” or “occupancy,” has received significant research interest over time.1–8 The methods for accomplishing this task generally fall into 1 of 2 categories: throughput-based models or empirical models. The basis of most throughput-based models is queuing theory, which models future inventory as a function of inflow, current inventory, and service time. Using analogous hospital terminology, future census is modeled as a function of admissions, current census, and length of stay.5 Empirical models, on the other hand, need not explicitly consider the flow of individual patients through a hospital, but rather detect statistical relationships between predictor variables and future hospital census using simple (linear regression, autoregressive integrated moving average) or complex (neural network) means.1,5 Some approaches have also combined both throughput-based and empirical components.3 Ultimately, there does not appear to be consensus on which modeling techniques are most useful for this task, nor does there appear to be a good understanding of how models at various scales (ie, hospital unit versus department versus whole-hospital census) translate between these different aggregations.

Predicting adult acute inpatient census is important to balance profitable use of hospital resources with the need to provide safe patient care and mitigate overcrowding. The term “adult acute” from our knowledge is specific to our institution but represents a concept that is common to most hospitals: a flexible pool of adult inpatient beds that can include ICU or general care. This pool accounts for the majority of inpatient census capacity. Before COVID, many hospitals around the country were routinely close to or over capacity. Once COVID arrived, many of these same hospitals quickly were overwhelmed and needed to postpone elective procedures to free up needed beds. However, this caused financial hardship that was often unsustainable because elective procedures are a primary profit generator for most hospitals, further emphasizing the need for actionable hospital census forecasts.9,10 In this context, our group was asked to develop predictions ranging from 4 hours to 7 days in the future. The urgency to operationalize predictions led us to first focus on 12-hour adult acute census predictions.

Literature on this topic has primarily described research efforts at census prediction, but recently there has been growing interest in operationalizing census prediction algorithms for real-time use by hospital management.11–13 In this manuscript, we describe the development of these models and subsequent operationalization in a dashboard available to our end user, which included hospital and divisional leadership and members of our inpatient command center.

Objective

To describe our preliminary efforts in developing and operationalizing a machine-learning model to predict hospital census 12 hours into the future.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

We obtained 19 months of hourly hospital inpatient census data, including breakdown by medical versus surgical census, and hourly admissions and discharges for both subgroups. Our data ranged from midnight, June 1, 2018, shortly after our hospital system migrated from our legacy system to Epic’s electronic health record (EHR), to 11PM on February 15, 2020, a date chosen to end before the CoVID-19 pandemic began to influence our hospital’s operations. We hypothesized that forecasting during the pandemic would require significant modifications to our models but also anticipated a return to “normal” operations at some point in the future. For our early models, we obtained data on the timing of physician admission, expected discharge date and discharge orders from our internally built unified data platform, which aggregates and houses data from our EHR system.

Of the 15 000 hourly rows that comprised our dataset, the first 12 500 were selected as our training set, while the last 2500 (roughly 3 months) were designated the test set. Our data contained total adult acute census by hour as well as a breakdown by medical and surgical subsets, which were mutually exclusive and collectively exhaustive. We then performed exploratory data analysis to inform feature engineering. We designed features that seemed relevant to the structure of the data: day of the week; time of day; medical and surgical census in the 3 hours, 8 hours and 24 hours prior; and the number of medical and surgical admissions and discharges in the 3 hours, 8 hours and 24 hours prior. This hospital-level dataset with the aforementioned features constituted our preprocessed data.

We then trained 2 models on this preprocessed data. One was a linear model with ElasticNet regularization, with cross-validation to optimize the regularization hyperparameters. The other one was a tree-based model using gradient boosting. For the second model, we selected a set of hyperparameters that were also optimized using cross-validation. We also trained 2 naïve models as a baseline for comparison. These models just assumed the ratio of change was constant at each time of the day, and equal to the average rate of census change in our training set. The first naïve model used the ratio of change by time of day, the second naïve model took both time of day and day of the week into account. In the case of the first naïve model, to make a prediction at 8am for what the census will be 12h later, we multiplied the current census by the average rate of increase or decrease in census for the 8am–8pm time interval in our training set. For all models, we measured the mean absolute error of our predictions. To check that our models were not overfitting, we tested the models against the most recent 3 months of census data that were not included in our training set. Details on our analysis can be found in our Supplementary Code Appendix.

Before selecting a model for operational use, our hospital administrator end users had specified an acceptable relative accuracy of 90% for the model. This was defined by the mean absolute error divided by our average total AA census.

RESULTS

Our training period contained 15 000 hourly census data points. Mean adult acute census was 524 (SD 42) patients. Mean medical census was 303 (SD 24), while mean surgical census was 220 (SD 31) patients. These data are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

General demographics/data set characterization

| Mean ± SD (no. patients) |

Maximum (no. patients) |

Minimum (no. patients) |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Total hourly census data points, N = 15 000 | |||

| Adult Acute Census | 524 ± 42 | 645 | 223 |

| Medical Census Subset | 303 ± 24 | 379 | 144 |

| Surgical Census Subset | 220 ± 31 | 315 | 66 |

Note: Adult acute census in our hospital is composed of all nonintensive care medical and surgical inpatients across all subspecialties.

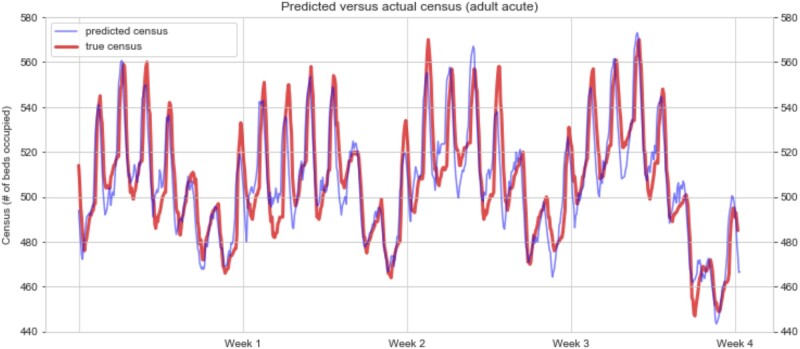

Exploratory review of the total hospital census suggested weekly cycles and daily spikes embedded therein. Visual inspection of the trends revealed that both the surgical and medical census fluctuations contributed to the presence of the daily spikes, while the underlying weekly trends appeared to be driven mainly by surgical census fluctuations. Figure 1 demonstrates 4 representative weeks of census data, with our predictions overlaid on the actual census.

Figure 1.

Hourly census over 4 representative weeks. Two cyclical patterns are apparent: 1 daily, 1 weekly. Red line—actual adult acute census. Blue line—predicted adult acute census.

Table 2 presents the results of our modeling approaches. Our linear model yielded census predictions that had a mean absolute error of 10.1 patients; 95% of predictions were accurate to ± 17.9 patients. With a mean census of 524 patients, this represented a relative accuracy of ± 3.4%. The 2 naïve approaches slightly underperformed our 2 approaches, with relative accuracies of 4.3% and 5.7%.

Table 2.

Performance of various models

| Model | Mean absolute error (no. patients) | 95% distribution of error (no. patients) | Relative 95% error |

|---|---|---|---|

| Naïve time of day | 14.42 | +/− 29.67 | +/− 5.7% |

| Naïve time of day and day of week | 9.98 | +/− 22.66 | +/− 4.3% |

| Regularized linear | 10.1 | +/− 17.9 | +/− 3.4% |

| Gradient-boosted tree | 9.96 | +/− 19.82 | +/− 3.8% |

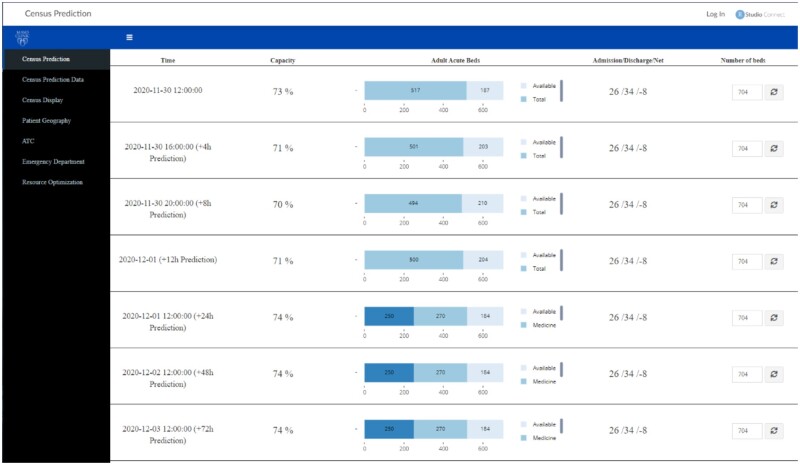

As our models appeared to have achieved a satisfactory level of predictive accuracy, we then proceeded to operationalizing the models. To accomplish this, we set up a system using our institution’s crontab and RShiny servers. Every hour, our code pulled the latest data from a refreshed SQL data table, filtered the patient population of interest, preprocessed the data for modeling, ran the model, and displayed both the current numbers and the predictions using an interactive RShiny application. Of note, for health systems using the Epic EHR, data tables in Clarity, Epic’s main relational database to support analytics, to our knowledge, are generally refreshed every 24 hours. This occurs after an extract, transform, and load process from the Chronicles database that supports clinical operations. Thus, certain workarounds may be needed to obtain hourly data of model features. A mockup of our application-in-progress is shown in Figure 2. Users could also see the historical accuracy of the model and download the data files with historical data and predictions.

Figure 2.

Mockup of hospital census dashboard application. Home screen view.

Notably, we were able to accomplish model training and dashboard development with a relatively small team, including 1 part-time data analyst devoted to data preprocessing and dashboard design, 1 part-time data scientist focused on model architecture and training, 1 physician with informatics training overseeing project direction, and several others providing consultative advice on various issues. The work described in this article was accomplished in 7 months, and is currently in operation, as of July 2020, at our hospital’s command center, where 12-hour predictions are being planned to inform allocation of certain on-site and on-call staff.

DISCUSSION

We describe our health system’s efforts to use machine-learning to predict hospital census. In examining our hospital’s census data, we noted predictable daily and weekly trends in hospital census. As noted in existing literature, this suggests that patient flow to and from hospitals seems to be characterized by some predictable factors, likely including work schedules of nursing homes, elective surgery scheduling, a preference to discharge patients during midday, and other factors which contribute to the predictable census fluctuations shown in Figure 1. This, in turn, allows for accurate prediction of hospital census using a straightforward linear model. Accurately predicting future hospital census is valuable to our hospital’s decision-makers who are seeking to maximize operational efficiency. In particular, 1 current use case centers around the reallocation of on-site general medical providers to flexible roles designed to accommodate large influxes of patients. Although our gradient-boosted tree model slightly outperformed our linear model, we did not feel that the difference was clinically meaningful and, therefore, would not justify increased resource demands for implementation. Our aim would be for subsequent work to improve not only single-hospital efficiency, but also system-wide efficiency for multihospital healthcare systems. Accomplishing this would require predictions specific to particular inpatient units, as specialty capabilities differ between hospitals, and our leadership is interested in pursuing such service-level predictions. We also hope to refine our models to better account for the effects of COVID, which may continue to affect hospital operations for some time. With respect to parameter updates, we intend to internally monitor prediction errors over time, solicit user feedback on predictions via our dashboard, and perform updates when either of these feedback channels suggest that the model is underperforming.

While other literature on this topic has rigorously evaluated various approaches to predicting hospital census, to our knowledge, this is the first report describing the development and operationalization of adult inpatient census with hourly updated predictions. The accuracy of our predictions appears comparable to other work that has attempted whole-hospital census prediction at similar time intervals, though our linear model achieves this with greater simplicity.7 As census prediction becomes of greater interest to other health systems, factors affecting replicability likely include the balance of surgical versus medical inpatients and the mix of scheduled versus urgent or emergent surgeries. The proportion of patients discharged to subsequent care facilities versus to home may also influence the timing of patient discharges, and therefore, overall census trends. One factor favorably impacting replicability is the widespread use of advanced EHRs, such as Epic, where structured data elements enable near-realtime predictive analytics.14

The naïve approach performed relatively well, although slightly worse than our 2 other approaches This is not surprising considering the strong cyclicality of the data, as can be seen in Figure 1. As can be seen in our Supplementary Appendix, the main variables by importance are time of day and certain days of the week. However, there are other variables that are also considered by the models, which likely account for the improved performance compared with the naïve approaches. The ElasticNet approach did not perform meaningfully worse than the best-performing gradient-boosting approach, so we opted for the ElasticNet approach for simplicity and interpretability reasons. This approach would also allow to easily add additional features in the future that could potentially be used to predict census, such as weather or number of COVID-19 cases in the community.

The main limitation of this study is our use of data from a single tertiary referral center with a large surgical practice, which may not generalize to other hospitals. Nonetheless, the features used in our models reflect general hospital metrics that could be measured at other institutions. Another limitation of our modeling approach is its limited ability to adapt to large exogenous shocks, such as the COVID pandemic. Because our model has relatively few features, some of which rely explicitly on recent census history, accuracy, while sufficient during “steady state” operations, likely suffers during large-scale outlier events. We anticipate needing additional features to capture such changes. Other limitations include the use of only 2 years of data. In our situation, this was limited by the transition of hospital electronic medical records 2 years ago. Additionally, our model as it is may not scale to predictions on longer time horizons. We anticipate needing to include surgical and clinic schedule volume information for predictions greater than 24 hours into the future. Still, the simplicity of our models should facilitate relatively quick implementation by other health systems looking to pursue similar initiatives.

CONCLUSION

Hospital systems can use simple, empirical machine learning models to accurately predict hospital census 12 hours into the future. These models can be operationalized fairly quickly and with limited resources, though obtaining hourly EHR data to feed the models may require ad hoc solutions.

FUNDING

This work was funded by a Mayo Clinic Practice Committee Innovation Program grant awarded to TCK.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

AJR: Interpretation of data, drafting, approval and accountability

SRB: Conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, critical revision, approval and accountability

NS: Acquisition, analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision, approval and accountability

JZ: Analysis and interpretation of data, critical revision, approval and accountability

RQ: Interpretation of data, critical revision, approval and accountability

TCK: Conception, design, acquisition, analysis, and interpretation of data, critical revision, approval and accountability

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

Supplementary material is available at Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association online.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors express their gratitude to Robert A. Domnick for his assistance in assembling data tables and to the rest of the Mayo Census Prediction group for their contributions to this work.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to its business confidential nature. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

None declared.

REFERENCES

- 1.Huang Y, Xu C, Ji M, et al. Medical service demand forecasting using a hybrid model based on ARIMA and self-adaptive filtering method. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak 2020; 20 (1). doi:10.1186/s12911-020-01256-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Zinouri N, Taaffe KM, Neyens DM.. Modelling and forecasting daily surgical case volume using time series analysis. Heal Syst 2018; 7: 111–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Koestler DC, Ombao H, Bender J.. Ensemble-based methods for forecasting census in hospital units. BMC Med Res Methodol 2013; 13 (1): 1–12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Garrison GM, Pecina JL.. Using the M/G/∞ queueing model to predict inpatient family medicine service census and resident workload. Health Informatics J 2016; 22 (3): 429–39. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Broyles JR, Cochran JK, Montgomery DC.. A statistical Markov chain approximation of transient hospital inpatient inventory. Eur J Oper Res 2010; 207 (3): 1645–57. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kortbeek N, Braaksma A, Burger CAJ, et al. Flexible nurse staffing based on hourly bed census predictions. Int J Prod Econ 2015; 161: 167–80. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Littig SJ, Isken MW.. Short term hospital occupancy prediction. Health Care Manage Sci 2007; 10 (1): 47–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wood SD.Forecasting patient census: commonalities in time series models. Health Serv Res 1976; 11: 158–65. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Paavola A. Outlook remains negative for US for-profit hospitals, Moody’s says. Becker’s Hosp. Rev. 2020. https://www.beckershospitalreview.com/finance/outlook-remains-negative-for-us-for-profit-hospitals-moody-s-says.htmlAccessed February 9, 2021

- 10.King R. Moody’s: Not-for-profit hospitals face major cash constraints, negative outlook for 2021 | FierceHealthcare. Fierce Healthc. 2020. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/hospitals/moody-s-not-for-profit-hospitals-face-major-cash-constraints-negative-outlook-for-2021Accessed February 9, 2021

- 11.LeanTaaS (company). Company - LeanTaaS. https://leantaas.com/about/Accessed November 16, 2020

- 12.Hospital JH. The Johns Hopkins Hospital Launches Capacity Command Center to Enhance Hospital Operations - 10/26/2016. https://www.hopkinsmedicine.org/news/media/releases/the_johns_hopkins_hospital_launches_capacity_command_center_to_enhance_hospital_operationsAccessed November 16, 2020

- 13.Impact M. Improving Patient-Care with Hospital Command Centers • Medtech Impact On Wellness. https://www.medtechimpact.com/improving-patient-care-with-hospital-command-centers/Accessed November 16, 2020

- 14.Fierce Healthcare. Epic, Meditech gain U.S. hospital market share as other EHR vendors lose ground | FierceHealthcare. https://www.fiercehealthcare.com/tech/epic-meditech-gain-u-s-hospital-market-share-as-other-ehr-vendors-lose-groundAccessed November 17, 2020

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The data underlying this article cannot be shared publicly due to its business confidential nature. The data will be shared on reasonable request to the corresponding author.