Abstract

Background

As a mitigation measure for COVID-19 pandemic, lockdown was implemented in India for a period of 2 months (24 March–31 May 2020). Disruption in antenatal care (ANC) provisions during lockdown is expected due to diversion of public health facilities on pandemic.

Objective

To assess the proportion of pregnant women who had not completed the ideal number of antenatal visits, availability of iron–folic acid (IFA) supplements and challenges in availing health services during the period of lockdown.

Methods

A concurrent mixed-methods study was conducted among pregnant women in Puducherry, India. Information on obstetric characteristics and details regarding antenatal visits were collected through telephonic interviews. In-depth interviews were conducted to understand the perceived challenges in availing health services during the lockdown period.

Results

Out of 150 pregnant women, 62 [41.3%; 95% confidence interval (CI) 33.6–49.3] did not complete the ideal number of visits and 61 (40.7%, 95% CI 32.7–49.0) developed health problems. Out of 44 women who received medical care for health problems, 11 (25%) used teleconsultation. Of all the women, 13 (8.7%, 95% CI 4.9–14.0) had not taken the IFA supplements as prescribed by the health provider. Economic hardship, restricted mobility, lack of information about the health system changes and psychological stress due to the fear of COVID were the challenges in accessing care.

Conclusions

Two out of five pregnant women did not complete the ideal number of visits and developed health problems during the lockdown period.

Keywords: Antenatal care, COVID, lockdown, maternal health, problems during pregnancy, teleconsultation

Key Messages.

40% of antenatal women had not completed the ideal number of visits.

Majority of the health problems were managed at home.

One in four women sought care for pregnancy problems used teleconsultation to avail care.

Introduction

In late 2019, the novel coronavirus was identified as the cause of many pneumonia cases in Wuhan, China and eventually, the disease caused by the virus was named as COVID-19 (1). As on 7 September 2020, there were 26.9 million confirmed cases and 0.88 million deaths (2) globally. To control the virus’s spread, India instituted a nationwide lockdown from 24 March to 31 May and it was extended till 30 June with a few relaxations. Despite the mitigation measures, India had 5 million confirmed cases and 82 066 deaths (as on 16 September) (3).

The nascent public health systems of low- and middle-income countries (LMICs) struggled to maintain essential services including non-communicable and maternal health care services during the pandemic as the resources were diverted for management of COVID-19 cases (4). Also, majority of the LMICs instituted either complete or partial lockdowns as a COVID-19 mitigation measure hampering the health care access. The modelling studies reported that if COVID-19 continues to spread can threaten essential health care services in the LMICs (5). The insights on challenges in delivering essential services during pandemic might help to mitigate it elsewhere or in future.

Pregnant women are among the vulnerable groups who need special attention during the COVID-19 pandemic. The vulnerability is not only because pregnant women are at risk of developing severe form of COVID-19 (6), but more so due to the potential disruption of routine antenatal care (ANC). The studies exploring the impact of epidemics like Ebola and SARS have shown that the prenatal and obstetric service suffered the most due to insufficient access and non-availability of essential health care services (7–9). Similarly, as management of individuals with COVID-19 became the need of the hour (10), non-emergency health care services for pregnant women were cancelled leading to fewer ANC visits (4).

Though several referral centres in India utilized telemedicine services for providing uninterrupted obstetric care services to pregnant women, the utilization of such services among pregnant women registered for care in public health facilities is not known. Hence, we aimed to assess the proportion of pregnant women who could not complete the scheduled antenatal visits, had disruptions in taking supplements, who developed any problems during pregnancy, the type of care they sought for the same, the usage of telemedicine services and challenges for accessing care during the lockdown period.

Methodology

Study design

A concurrent mixed-methods study was conducted with quantitative (cross-sectional study) and qualitative (descriptive study) design.

Study setting

This study was conducted in two conveniently selected urban Primary Health Centres (PHC) of Puducherry, South India. On registration (booking) in these PHCs, pregnant women are given free ANC including iron–folic acid (IFA) and calcium supplements, deworming and tetanus toxoid vaccination. The women without high-risk pregnancy are asked to visit PHCs once every month till 28 weeks of gestation, once every 2 weeks during 29–36 weeks and every week after 36 weeks until delivery (11).

The health advisory released on May 2020 suggested to continue essential reproductive, maternal, new born, child and adolescent nutrition services through home delivery of IFA tablets and promotion of teleconsultation services (12). The pregnant women were advised to limit the visits to PHC and avail care through teleconsultation.

Study period

We collected data during 15 July–7 June 2020. We inquired the participants about their ANC during the lockdown period (March–May 2020).

Study population including sample size

Quantitative

All pregnant women registered for ANC in selected PHCs during December 2019 to May 2020 were eligible for the study. We used the formula, for sample size calculation (13). The minimum sample size was 174 pregnant women, assuming that the proportion not able access care as 33% (14), relative precision of 20% and 95% confidence level.

Qualitative

Purposive sampling was used to select participants for exploring the challenges in availing ANC services. Participants were selected based on their week of gestation. In total, 12 pregnant women were interviewed (three were in first trimester, six in second and three in third trimester). The interviews were guided by the information saturation.

Study variables and data collection

Quantitative

Information on number of antenatal visits made during the lockdown period, intake of iron and other supplements, the health problems faced, seeking medical care for the same and mode of care received were captured through telephonic interviews. Ideal number of health facility visit was considered as once a month till 28 weeks of gestation, twice a month from 29 to 36 weeks and every week from 37 weeks till delivery. If any of these visits is missed, it was considered as ‘not completing the ideal number of visits’ (11).

Pregnant women were advised to take the IFA tablets based on their haemoglobin level (normal values-once daily and anaemic woman-twice daily). If they missed these supplements, they were considered as ‘not taking IFA as prescribed by the health worker’.

Qualitative

In-depth interviews were conducted telephonically in the local language (Tamil) by a female public health researcher (RU) trained in qualitative research. The interviews were planned according to the convenience of the pregnant women and were audio-recorded. Interview guide with the set of semi-structured questions and prompts was used to guide the interviews (Supplementary File 1). Interviews lasted for an average of 10 (ranging 8–20) minutes.

Data analysis

The quantitative data were entered into EpiCollect5 and analysed using Stata version 11.0 (StataCorp LP, College Station, TX). The outcome variables were expressed as proportions with 95% confidence intervals (CIs).

Using the audio-recordings, RU prepared the transcripts within 3 days of the interview. Manual content analysis was done independently by two trained investigators (RU and PT) to identify the codes. A final list of codes was decided after discussion between the two investigators. Similar transcripts’ codes were grouped as themes. The results were reported using a 32 item ‘Consolidated Criteria for Reporting Qualitative Research’ (15).

Results

We contacted 180 pregnant women through telephonic calls and we could reach 150 women (response rate of 83.3%). Of 150 women, 114 (77%) had completed their undergraduate or master’s degree and the median monthly family income was 10 000 INR (~133 USD). Among the pregnant women, 83 (55%) were primigravida, 20 (13.3%) were in the first trimester, 93 (62.0%) were in their second trimester and 37 (24.7%) were in the last trimester (Table 1).

Table 1.

Obstetric characteristics of antenatal mothers registered in selected urban PHCs of Puducherry during the period of lockdown of COVID-19 pandemic 2020 (N = 150)

| Parameter | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Gravida | ||

| Primi | 83 | 55.7 |

| Multi | 66 | 44.3 |

| Period of gestation in weeks | ||

| 5–28 | 113 | 75.4 |

| 29–36 | 29 | 19.3 |

| 37–40 | 8 | 5.3 |

| Comorbiditiesa | ||

| Gestational diabetes mellitus | 16 | 10.7 |

| Pregnancy-induced hypertension | 7 | 4.7 |

| Othersc | 13 | 8.7 |

| Nil | 122 | 81.3 |

| Source of IFAb | ||

| Government | 118 | 78.7 |

| Private | 27 | 18 |

| Not accessible | 5 | 3.3 |

aMore than one comorbidity present.

bIron–folic acid.

cOther comorbidities were asthma and thyroid problems.

Of the total, 62 (41.3%; 95% CI 33.6–49.3) women did not complete the ideal number of visits and 48 (32.0%; 95% CI 24.6–40.1) did not visit the health facility at least once. Thirteen women (8.7%, 95% CI 4.9–14.0) had not taken the IFA as prescribed by the health provider, of which, five (38%) women reported restricted mobility to get the IFA tablets as the reason (Table 2).

Table 2.

Proportion of antenatal women could not complete their scheduled number of ideal visits and the dose of IFA as prescribed by health worker during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic in 2020 in Puducherry, India (N = 150)

| Particulars | Total | Missed visits | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n | (%) | ||

| Total | 150 | 62 | (41.3) |

| Number of expected visits required during lockdown | |||

| Monthly once | 113 | 42 | (37.2) |

| Monthly twice | 29 | 12 | (41.4) |

| Weekly once | 8 | 8 | (100.0) |

| Not taken IFA | |||

| Total | 150 | 13 | (8.7) |

| Number of doses missed (13) | |||

| 2–5 | 7 | (53.8) | |

| 5–10 | 2 | (15.4) | |

| More than 10 | 4 | (30.8) | |

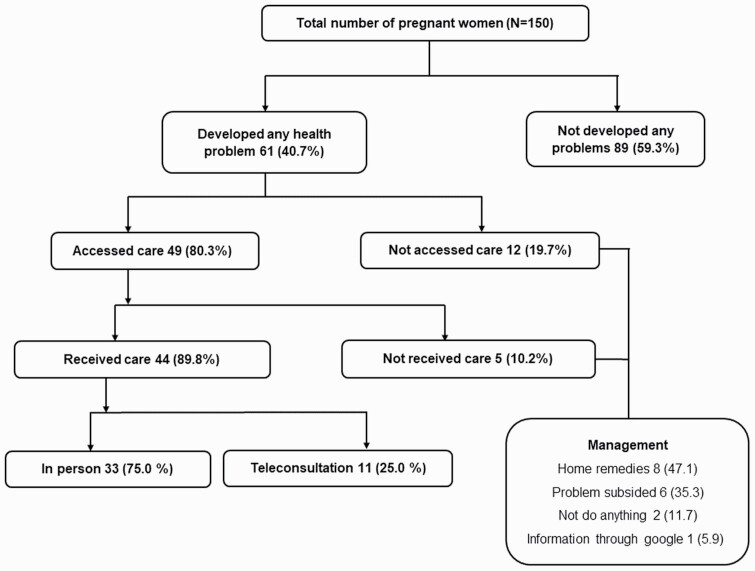

Overall, 61 (40.7%, 95% CI 32.7–49.0) women reported health problems during the lockdown period (Table 3), out of which 30 (49.2%) women were in their second trimester and 44 (44/61, 72%) received medical care or consultation (Fig. 1). Of all the women who accessed medical services, nearly 19 (19/49, 38.8%) contacted the private provider and 30 (30/49, 61%) had approached government facilities; out of which, 5 (10%) preferred tertiary institutes for their health problems. 11 (7.3%) women opted for teleconsultation. About three fourth (118, 78.7%) of the women received IFA from the public health system through home delivery. Of all the women, 10 (10/61, 16.4%) experienced labour and had childbirth.

Table 3.

Type of the health problems faced by the antenatal mothers during the lockdown period of COVID-19 pandemic in selected urban PHCs of Puducherry, South India (N = 61)

| Health problems | Number | Percentage |

|---|---|---|

| Pain (stomach, vaginal, hip) | 32 | 52.5 |

| Bleeding | 4 | 6.6 |

| Labour pain, leaking PV | 10 | 16.4 |

| Vomiting | 7 | 11.5 |

| Swelling in legs | 5 | 8.2 |

| Othersa | 11 | 18 |

Multiple options are possible.

aOther problems include abnormal baby movements (4), increased blood sugar (1), increased blood pressure (1), fall from the steps (1), gastritis (1), cramps in leg (1), thyroid problem (1).

Figure 1.

Flowchart describing the health problems faced and the pattern of care received by pregnant women during the lockdown period (23 March–31 May 2020) of COVID-19 pandemic in Puducherry.

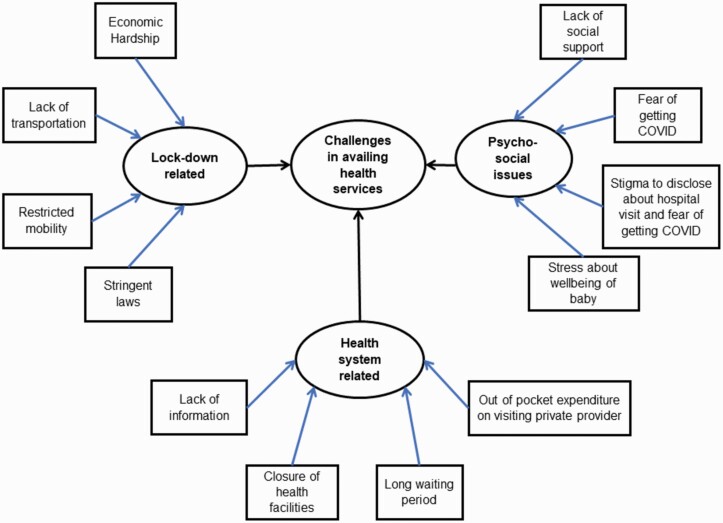

Challenges in optimal ANC wellbeing due to COVID pandemic

In total, 12 codes were generated from the transcripts of the 12 interviews (Fig. 2). The codes were categorized and detailed under the three broad themes as given below.

Figure 2.

Challenges for availing ANC services during 23 March–31 May 2020 as perceived by the pregnant women in Puducherry (n = 12).

Lockdown related issues

On analysis, four codes reflecting the challenges due to instituted lockdown emerged and are listed along with relevant verbatim below.

Economic hardship

Pregnant women stated that continuous lockdown of 2 months had pushed their family to economic hardship due to disruption in regular earning and the loss in family income meant the additional expenditure on healthy food items like fruits and vegetables was not possible. If not for lockdown, the family members would have put extra effort to earn more to meet the additional expenses.

A 29-year-old lady in her second trimester said,

My husband had lost his job during the lockdown. We stay in a rented house. There is not enough money for household expenses and we faced several problems including not being able to meet my nutritional requirements, as well as the baby’s.

Restricted mobility and stringent laws

Pregnant women expressed that the requirement of prior permission to go out of the house and lack of clarity on the regulations put them in confusion.

A woman aged 25 years in her second trimester said,

This situation restricts my communication with others as I have restricted others’ entry into my house. In other words, I am in ‘house arrest’. The places I used to visit regularly like the beach or the temple are not possible now, and the same goes for my regular walks.

Lack of transportation

Women staying away from the health facilities reported the non-availability of transport as the reason for not making scheduled ANC visits.

A woman in her second trimester said,

We are staying far from the PHC. I used to take an auto or bus to go to the hospital. Now I depend on others and most of the times, no one was available. Thus, I didn’t go for the last two check-ups.

Psycho-social issues

Four codes reflecting the challenges to optimal ANC due to psycho-social issues had emerged.

Lack of social support

Some pregnant women felt that they could not enjoy the priority and the usual social support women receive during pregnancy. As the routine events like family get-together and celebrations were put on hold, the pregnant women developed loneliness, fear and insecurity.

One participant in the second trimester replied,

I don’t think there is going to be a bangle ceremony for me and so it has become impossible for my mother and other relatives to visit me. Because of the lockdown, transport is affected and I am compelled to stay alone.

Stress about the baby’s health and wellbeing

Almost all the pregnant women interviewed felt that inability to visit the health facilities prompted them to worry about their health, wellbeing and safe natal care during delivery.

A lady in the first trimester said,

I am 36 years old and I had an abortion 6 months back. During the time of lockdown all the established hospitals had closed their outpatient department. Nowadays, babies are delivered with inadequate growth, absence of heartbeat etc. I was concerned about my baby’s health and that created an unexplainable fear inside me. I would have ended up having another abortion due to fear and was looking for some emotional support.

Stigma to disclose about hospital visit and fear of getting COVID

Pregnant women stated that they experienced stigma to disclose their visit to health facilities, as the neighbours and family members tried to distance from them. They experienced fear of contracting COVID-19 during their hospital visit.

A 23-year-old pregnant woman in her first trimester expressed that

I can go to tertiary institutes, but my neighbours and relatives are advising me not to go; they feel my baby and I will get infected.

Health system-related issues

Four codes reflecting the challenges to optimal ANC due to health system-related factors had emerged on analysis.

Lack of information

Though the tertiary care centres and maternity hospitals were functioning with prior appointments, the pregnant women felt that they could not book the appointment due to lack of information. The phone numbers to book appointments were not circulated widely and there were issues with connectivity.

A woman in the second trimester was saying,

In tertiary institutions, we need to book prior appointments. My husband got many numbers for booking, but the numbers are either always busy or not reachable.

Closure of health facilities

Women voiced out that the health facilities shut their regular outpatient clinics during the lockdown. The women visiting such facilities had to return without seeking care.

A pregnant woman aged 28 years in her third trimester stated,

I was advised to go for anomaly scan before lockdown. I went to a government hospital and the outpatient services were stopped; they informed me not to come. Then I called a private clinic where they told me they are not ready to see any new patients and I was not able to consult the doctor.

Out-of-pocket expenditure of visiting a private provider

The closure of public health facilities meant the pregnant women either had to approach private providers with out-of-pocket expenditure. When not able to afford the care at private facilities,

A 28-year-old pregnant woman in her third trimester said,

Doctors advised a scan, but government institutions refused, and in private, they said it is 3000 rupees for scan. I didn’t go for scan as i didn’t have money. I am quite sad to think about it now.

Discussion

Our study showed that two-fifths of the pregnant women did not make the ideal number of health care visits during the lockdown and about one-third of these women did not visit the health care facility even once. Restricted mobility, closure of health facilities and diversion of health services towards COVID affected ANC.

Shortcomings in provisions for maternal and child health services during a pandemic is not new and has been reported previously. Our study’s findings are in line with the reduction of first ANC visits during the Ebola outbreak in 2014–15 in Liberia (9). During the Ebola outbreak, women requiring antenatal, obstetric and emergency services were affected the most; witnessed reduced ANC visits from 35% to 50% and a 35% drop in the facility-based deliveries compared with regular times (7,9). In our setting, 68% of pregnant women had at least one contact with the health provider during the lockdown period. Outpatient teleconsultation services, availability of tertiary and maternity institutes, and well-functioning primary care centres in the study setting could be the reasons for a relatively better ANC provision during the pandemic. In the current study, 20% of pregnant women did not have antenatal check-ups during the first trimester and this was high compared with national family health survey (NFHS-4) (9%) findings for the same setting (16). Overall, 41.3% did not complete the ideal number of visits during the lockdown in our study. This proportion could be higher than 8% of women who did not have four or more antenatal visits reported by NFHS-4 (2015–16) for the Puducherry region’s urban areas (study setting) (16). NFHS-4 do not report on the ideal number of antenatal visits and hence we could not make a direct comparison.

Nearly 40% of the women who reported health problems, availed care in private sector. Though with public health facilities, women sought care in the private sector as public facilities were engaged in COVID response. It would have increased the out-of-pocket costs for those women. A majority of the reported health problems could be managed at home, and our qualitative inquiry also reflected the same.

Compliance with IFA was relatively high (91.3%) in the present study, even during the pandemic when compared with regular times. NFHS-4 reported intake of 100 days of IFA as 66.3% in the study setting (16) before the pandemic. Studies from other states of India reported compliance to IFA ranging from 62% to 81.7% (17–19).

With restricted mobility and less social bonding during the lockdown, pregnant women’s mental health needs attention. Studies reported that the COVID-19 pandemic increased psychological stress and depression, elevated pregnancy anxiety among pregnant women (20). Psychological factors and lesser ANC visits, and lack of social support would increase preterm birth and deliver low birth weight babies (21,22). Our qualitative inquiry revealed that women were anxious about the baby’s health and contracting COVID-19 during health facility visits. Health worker’s home visits with adequate personal protective equipment or tele-counselling services would reduce anxiety and fear. A study done in the USA showed that telemedicine services increased from 0% to 97% during the COVID-19 pandemic compared with the data in the same period of last year (23).

The mixed-method design adopted in the study not only enabled us to quantify the deviance from the routine ANC, rather helped to understand the challenges faced by pregnant women in availing health services. However, study has some limitations. The study included only urban health centres and we did not retrieve the sample size from power analysis. The study findings may not be generalizable to rural areas because women’s education, availability of health care services and access and health-seeking behaviour could be different in rural areas compared with urban areas (24). We failed to capture the information on distance to the health facility and partner support. The responses regarding consumption of IFA and hospital visits during lockdown were self-reported and hence prone to recall bias. We did not capture the impact of COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown on pregnancy outcomes and challenges in availing the intrapartum care and we recommend further studies on this.

To conclude, one-third of pregnant women did not visit health care facilities during lockdown and about two-fifths had health problems. Globally, there is need for uninterrupted delivery of essential services like ANC despite several health facilities and health care workers are earmarked and engaged exclusively in COVID-19 response. The primary health care system with its peripheral health workers has to focus on delivering ANC by engaging with pregnant women in their catchment area. Given the challenges with house-visit due to restricted mobility, the mobile phones can be used to establish communication with pregnant women for educating on COVID-19 appropriate behaviours. Linkages with private health facilities to provide ANC during pandemic and use of telemedicine services for care provision will improve the accessibility. However, it is hard to establish such care provision systems during the pandemic and is possible only when there is strong and responsive primary health care system.

Supplementary Material

Declaration

Funding: the authors did not receive any funding for this study.

Ethical approval: the study was approved by the Institute Ethics Committee of a tertiary care hospital, Puducherry, South India.

Conflict of interest: none.

Data availability

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

References

- 1. Li H, Liu SM, Yu XH, Tang SL, Tang CK. Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19): current status and future perspectives. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2020; 55(5): 105951. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. World Health Organisation. WHO Coronavirus Disease (COVID-19) Dashboard [Internet]. 2020.. https://covid19.who.int/ (accessed on 9 March 2021).

- 3. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare Government of India. India Fights Corona COVID-19 in India, Corona Virus Tracker [Internet]. 2020.. https://www.mygov.in/covid-19 (accessed on 16 September 2020).

- 4. Garg S, Basu S, Rustagi R, Borle A. Primary health care facility preparedness for outpatient service provision during the COVID-19 pandemic in India: cross-sectional study. JMIR Public Health Surveill 2020; 6(2): e19927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. McDonald CR, Weckman AM, Wright JK, Conroy AL, Kain KC.. Pregnant Women in Low- and Middle-Income Countries Require a Special Focus During the COVID-19 Pandemic, Vol. 1. Frontiers in Global Women’s Health, 2020, p. 6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chen Y, Li Z, Zhang YY, Zhao WH, Yu ZY. Maternal health care management during the outbreak of coronavirus disease 2019. J Med Virol 2020; 92(7): 731–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Shannon FQ II, Horace-Kwemi E, Najjemba R et al. Effects of the 2014 Ebola outbreak on antenatal care and delivery outcomes in Liberia: a nationwide analysis. Public Health Action 2017; 7 (suppl 1): S88–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Caulker VML, Mishra S, van Griensven J et al. Life goes on: the resilience of maternal primary care during the Ebola outbreak in rural Sierra Leone. Public Health Action 2017; 7 (suppl 1): 40–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Wagenaar BH, Augusto O, Beste J et al. The 2014–2015 Ebola virus disease outbreak and primary healthcare delivery in Liberia: time-series analyses for 2010–2016. PLoS Med 2018; 15(2): e1002508. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Esegbona-Adeigbe S. Impact of COVID-19 on antenatal care provision. Eur J Midwifery 2020; 4: 16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Carter EB, Tuuli MG, Caughey AB et al. Number of prenatal visits and pregnancy outcomes in low-risk women. J Perinatol 2016; 36(3): 178–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India. Guidance Note on Provision of Reproductive, Maternal, Newborn, Child, Adolescent Health Plus Nutrition (RMNCAH+N) Services During & Post COVID-19 Pandemic, Vol. 1. 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 13. Pourhoseingholi MA, Vahedi M, Rahimzadeh M. Sample size calculation in medical studies. Gastroenterol Hepatol Bed Bench 2013; 6(1): 14–7. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. McQuilkin PA, Udhayashankar K, Niescierenko M, Maranda L. Health-care access during the Ebola virus epidemic in Liberia. Am J Trop Med Hyg 2017; 97(3): 931–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Tong A, Sainsbury P, Craig J. Consolidated criteria for reporting qualitative research (COREQ): a 32-item checklist for interviews and focus groups. Int J Qual Health Care 2007; 19(6): 349–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. International Institute for Population Sciences. National Family Health Survey-4 District Fact Sheet Puducherry. Mumbai, India: Ministry of Health and Family Welfare, Government of India, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 17. Mithra P, Unnikrishnan B, Rekha T et al. Compliance with iron-folic acid (IFA) therapy among pregnant women in an urban area of south India. Afr Health Sci 2013; 13(4): 880–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Pal PP, Sharma S, Sarkar TK, Mitra P. Iron and folic acid consumption by the ante-natal mothers in a rural area of India in 2010. Int J Prev Med 2013; 4(10): 1213–6. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Debi S, Basu G, Mondal R et al. Compliance to iron-folic-acid supplementation and associated factors among pregnant women: a cross-sectional survey in a district of West Bengal, India. J Family Med Prim Care 2020; 9(7): 3613–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Lebel C, MacKinnon A, Bagshawe M, Tomfohr-Madsen L, Giesbrecht G. Elevated depression and anxiety symptoms among pregnant individuals during the COVID-19 pandemic. J Affect Disord 2020; 277: 5–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Adam Z, Ameme DK, Nortey P, Afari EA, Kenu E. Determinants of low birth weight in neonates born in three hospitals in Brong Ahafo region, Ghana, 2016—an unmatched case-control study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth 2019; 19(1): 174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lima SAM, El Dib RP, Rodrigues MRK et al. Is the risk of low birth weight or preterm labor greater when maternal stress is experienced during pregnancy? A systematic review and meta-analysis of cohort studies. PLoS One 2018; 13(7): e0200594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Barney A, Buckelew S, Mesheriakova V, Raymond-Flesch M. The COVID-19 pandemic and rapid implementation of adolescent and young adult telemedicine: challenges and opportunities for innovation. J Adolesc Health 2020; 67(2): 164–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Rani M, Bonu S, Harvey S. Differentials in the quality of antenatal care in India. Int J Qual Health Care 2008; 20(1): 62–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets analysed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.