Abstract

Background

Healthcare workers (HCWs) can be a source of SARS-CoV-2 within long-term care facilities (LTCFs); therefore, we analysed the data from a testing programme among LTCF employees.

Aims

The aim of this study was to investigate the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 and its determinants among employees of LTCFs and the risk for fellow workers and residents.

Methods

Testing started at week 15, the first wave’s peak, using nasopharyngeal swabs for PCR up to week 23. At the start of the second wave (week 32), testing resumed.

Results

A total of 32 457 test results were available from 446 LTCFs: 2% were positive: 1% in men, 2% in women, 2% in HCWs (=having patient contact), 1% in non-HCWs, higher in younger age groups. In total, 30 729 employees were tested once, 823 twice, 66 thrice and 4 four times. Prevalence was 13% during the first week of testing (week 15) and declined to 7% (week 16) to stay at around 1% (from week 17 until week 23). At the start of the second wave (week 31–33), the prevalence was around 3%. In 70% of positive tests, the employee was asymptomatic.

Conclusions

Our study confirms the presence of HCWs with SARS-CoV-2 as a possible source of infection in LTCFs even when the incidence in the general population was low; 70% were asymptomatic. To control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in LTCFs vaccination, infection prevention and control measures are necessary as well as testing of all LTCF HCWs during possible outbreaks, even if asymptomatic.

Keywords: Health care workers, long-term care facilities, PCR, SARS-CoV-2

Key learning points.

What is already known about this subject

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 but could also transmit it silently, particularly in long-term care facilities (LTCFs).

We wanted to know the prevalence of COVID-19 in HCWs in long-term care facilities in Belgium during first peak of the pandemic and the proportion of asymptomatic infections.

What this study adds

This study found that the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2 positive employees in LTCFs is about 2%—of which a large part (70%) is asymptomatic.

This large proportion of asymptomatic carriers is a risk for transmission of the virus, both to residents and fellow workers, particularly when vaccination coverage is low.

Impact on practice or policy

Infection control measures should be strictly adhered to in LTCFs also in the absence of symptomatic cases.

When outbreaks occur after vaccination, screening of all (both asymptomatic and symptomatic) HCWs in LTCFs, including contact tracing and quarantine, should be done to protect both residents and other HCWs against infection.

Introduction

Healthcare workers (HCWs) are at risk of infection with SARS-CoV-2 [1–3] but they could also be a source of silent transmission, particularly in long-term care facilities (LTCFs) [4]. During the first wave of the pandemic, a campaign was implemented in LCTFs in Belgium to test all employees. We here report the results of the Occupational Health Service (OHS) IDEWE.

Methods

The campaign was carried out according to Belgian and international privacy and ethical legislation, allowing post hoc analysis of anonymized data.

The objectives of the study were to analyse the PCR results of nasopharyngeal swabs taken from staff during a testing campaign decided by the ministry of health of Belgium in LTCFs affiliated with the OHS IDEWE in order to determine the prevalence of infection with SARS-CoV-2 and its determinants (gender, age, occupation), the evolution in time and possible risk for spreading among fellow workers and residents [5].

The campaign was rolled out on April 8 2020 (=week 15); facilities reporting outbreaks among residents were given priority; testing continued until week 23, when all LTCFs had been tested. All employees were invited including those absent due to disease or other reasons. From week 24 to 31, when the incidence in the general population was low, no systematic testing was performed; from week 32 on, at the start of the second wave, testing resumed when an alarm level was reached in the general population in the LTCF’s municipality.

Nasopharyngeal swabs were collected by occupational physicians (OPs), according to a standardized procedure in compliance with all prescribed safety measures, and real-time PCR testing was performed in pre-selected laboratories. Reporting of COVID-19 symptoms was not compulsory but strongly encouraged. Results of tests were registered by the OP in the employee’s electronic occupational health file. More details of the testing campaign in Belgium have been published elsewhere [5].

The proportion of positive samples was calculated for employees, overall, by age group and occupation. We included in the category HCWs all occupations having direct or face contact with patients. Among the positive cases, we calculated the proportion of asymptomatic presentations at the time of testing. We calculated the odds ratios (ORs) and corresponding confidence intervals (CIs). Data were analysed with SPSS (version 25).

Results

Test results were available from 446 LTCFs (221 [50%] LTCFs for the elderly people, 100 [22%] facilities for people with disability, 81 [18%] various long-care institutions and 44 [10%] other welfare and care facilities), together representing 20% of the 2240 LTCFs affiliated with OHS IDEWE.

Of 32 457 reported test results, 2% (n = 509) was positive: 1% (65) in men and 2% (460) in women (OR 1.4 [95% CI 1.10–1.87]). In HCWs, 2% were positive, and in non-HCWs, 1% were positive (OR 2.1 [95% CI 1.66–2.64]). The distribution according to age and occupation is given in Table 1; prevalence was slightly higher in younger age groups and significantly higher in HCWs compared to non-HCWs in every age group, except the youngest one.

Table 1.

Number of positive tests (%; 95% CI) by age group and occupation (HCWs/non-HCWs) in employees (total tested in group)

| Age group | 15–24 years | 25–34 years | 35–44 years | 45–54 years | 55+ years | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HCWs | 23 (2; 1.2–1.8) | 88 (2; 1.9–2.9) | 66 (2; 1.4–2.4) | 74 (2; 1.7–2.7) | 57 (2; 1.5–2.5) | 308 (2; 1.9–2.3) |

| (1148) | (3716) | (3531) | (3413) | (2877) | (14 685) | |

| Non-HCWs | 6 (2; 0.3–3.1) | 15 (1; 0.5–1.5) | 23 (1; 0.6–1.4) | 28 (1; 0.6–1.4) | 24 (1; 0.5–1.3) | 94 (1; 0.8–1.2) |

| (348) | (1510) | (2044) | (2837) | (2546) | (9285) | |

| Total | 29 (2) | 103 (2) | 87 (2) | 102 (2) | 81 (2) | 402 (2) |

| (1496) | (5226) | (5575) | (6250) | (5423) | (23 970) |

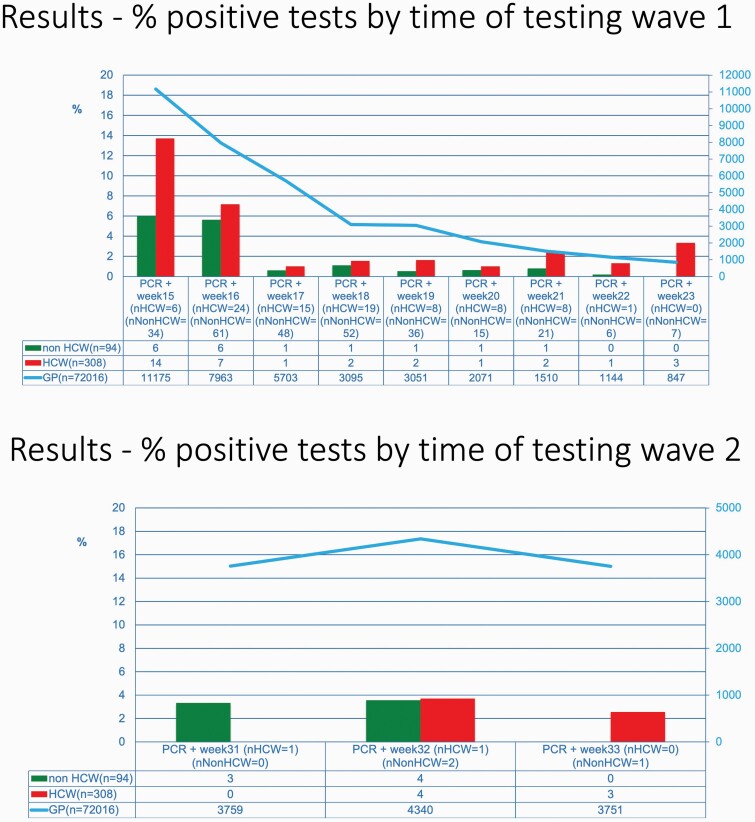

A total of 30 729 employees were tested once, 823 twice, 66 three time and 4 4 times; there was no difference in testing frequency according to occupation (i.e. HCW versus non-HCW). The evolution of the prevalence in time and the total number of cases in Belgium is shown in Figure 1. It shows a high prevalence (13%) in week 15, gradually decreasing and staying around 1% until week 23. From week 31 to 33, at the start of the second wave, the prevalence was around 3%. In about 70% of the positive tests (171/242), the employee was asymptomatic.

Figure 1.

Prevalence of positive tests in personnel in LTCFs in time.

Discussion

Our study confirms the findings of other international and Belgian studies: the prevalence of SARS-CoV-2-positive employees in LTCFs is about 2%—and they are largely asymptomatic [1,2,5]. This prevalence is comparable to that of a larger (n = 138 327) but shorter study (April 8 until May 18) in Belgian LCTFs [5]. Our study shows, however, that the virus remained present in employees in LTCFs after May18.

The high-prevalence SARS-CoV-2-positive employees during the first 2 weeks of the campaign reflected the fact that perceived high-risk facilities being sampled first. A remarkable agreement between the incidence in the general population and that in LCTF employees is shown in Figure 1. The virus was present almost constantly among mostly asymptomatic HCWs working in LTCFs during the pandemic. These mostly asymptomatic HCWs can transmit the infection to both residents and fellow workers as shown by a study using genetic sequencing of SARS-CoV-2 isolated from Dutch HCWs [6]. Transmission and spread of the virus are possible from both symptomatic and asymptomatic cases, supporting the hypothesis that asymptomatic carriers of the virus including HCWs represent an important driver of transmission in LTCFs among both residents and fellow workers particularly through undetected spread, when preventive measures are only applied for symptomatic cases [4].

The main strengths of our study were that it was a real-life situation in the middle of the SARS-CoV-2 pandemic, that the tests were carried out according to a standardized procedure, analysis of PCR’s was done in dedicated laboratories and the results were directly put into each tested worker’s electronic occupational health file. One of the limitations of our study was that the reporting of symptoms by the OP was not compulsory. Our proportion of asymptomatic cases, however, concurs with the results of a recent systematic review on the proportions of asymptomatic persons among COVID-19-positive cases [7].

According to infection control measures mandated in Belgium, surgical masks are recommended for most care activities, FP2 masks for care for suspected or confirmed COVID-19 patients [8]. To control the spread of SARS-CoV-2 in LTCFs in both residents and employees in the future, vaccination is paramount, but extensive infection prevention and control measures (masking, physical distancing, daily symptom screening and regular testing) are still necessary even in environments with a high vaccination coverage, until herd immunity is reached at large. When outbreaks do occur, we recommend prompt screening of HCWs even when asymptomatic [3,9,10], including contact tracing and quarantine.

Funding

IDEWE External Service for Prevention and Protection at Work, Leuven, Belgium.

Competing interests

None declared.

References

- 1. Shields A, Faustini SE, Perez-Toledo Met al. . SARS-CoV-2 seroprevalence and asymptomatic viral carriage in healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study. Thorax 2020;75:1089–1094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Nguyen LH, Drew DA, Graham MSet al. . Risk of COVID-19 among front-line health-care workers and the general community: a prospective cohort study. Lancet Public Health 2020;5:e475–e483. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Fell A, Beaudoin A, D’Heilly P, Mumm E, Cole C, Tourdot L. SARS-CoV-2 exposure and infection among health care personnel—Minnesota, March 6–July 11, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69: 1605–1610. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Dautzenberg M, Eikelenboom-Boskamp A, Drabbe Met al. . Healthcare workers in elderly care: a source of silent SARS-CoV-2 transmission? MedRxiv, doi: 10.1101/2020.09.07.20178731, 9 September 2020, preprint: not peer reviewed. [DOI]

- 5. Hoxha A, Wyndham-Thomas C, Klamer Set al.. Asymptomatic SARS-CoV-2 infection in Belgian long-term care facilities. Lancet Infect Dis. 2021;21:e67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Sikkema RS, Pas SD, Nieuwenhuijse DFet al.. COVID-19 in health-care workers in three hospitals in the south of the Netherlands: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Infect Dis 2020;20:1273–1280. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Yanes-Lane M, Winters N, Fregonese Fet al.. Proportion of asymptomatic infection among COVID-19 positive persons and their transmission potential: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PLoS ONE 2020;15: e0241536. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. European Centre for Disease Prevention and Control (ECDC). Infection Prevention and Control and Preparedness for COVID-19 in Healthcare Settings – Sixth Update, 9 February 2021. Stockholm: ECDC; 2021. https://www.ecdc.europa.eu/en/publications-data/infection-prevention-and-control-and-preparedness-covid-19-healthcare-settings (2 June 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]

- 9. Taylor J, Carter RJ, Lehnertz N, Kazazian L, Sullivan M, Wang X. Serial testing for SARS-CoV-2 and virus whole genome sequencing inform infection risk at two skilled nursing facilities with COVID-19 outbreaks—Minnesota, April–June 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 2020;69:1288–1295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. World Health Organization (WHO). Prevention, Identification and Management of Health Worker Infection in the Context of COVID-19. Interim Guidance, 30 October 2020. WHO/ 2019-nCoV/HW_infection/2020.1. Geneva, Switzerland: WHO; 2020. https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/10665-336265 (2 June 2021, date last accessed). [Google Scholar]