ABSTRACT

Background: Despite the established evidence base of psychological interventions in treating PTSD in children and young people, concern that these trauma-focused treatments may ‘retraumatise’ patients or exacerbate symptoms and cause dropout has been identified as a barrier to their implementation. Dropout from treatment is indicative of its relative acceptability in this population.

Objective: Estimate the prevalence of dropout in children and young people receiving a psychological therapy for PTSD as part of a randomized controlled trial (RCT).

Methods: A systematic search of the literature was conducted to identify RCTs of evidence-based treatment of PTSD in children and young people. Proportion meta-analyses estimated the prevalence of dropout. Odds ratios compared the relative likelihood of dropout between different treatments and controls. Subgroup analysis assessed the impact of potential moderating variables.

Results: Forty RCTs were identified. Dropout from all treatment or active control arms was estimated to be 11.7%, 95% CI [9.0, 14.6]. Dropout from evidence-based treatment (TFCBTs and EMDR) was 11.2%, 95% CI [8.2, 14.6]. Dropout from non-trauma focused treatments or controls was 12.8%, 95% CI [7.6, 19.1]. There was no significant difference in the odds of dropout when comparing different modalities. Group rather than individual delivery, and lay versus professional delivery, were associated with less dropout.

Conclusions: Evidence-based treatments for children and young people with PTSD do not result in higher prevalence of dropout than non-trauma focused treatment or waiting list conditions. Trauma-focused therapies appear to be well tolerated in children and young people.

KEYWORDS: PTSD, dropout, psychotherapy, CBT, EMDR, acceptability, TF-CBT, children, adolescents

HIGHLIGHTS

Dropout from RCTs is not more likely for trauma-focused treatments than for non-trauma-focused arms or control conditions.

Trauma-focused treatments for PTSD are acceptable to most youth.

Short abstract

Antecedentes: A pesar de la base de evidencia establecida de intervenciones psicológicas en el tratamiento del TEPT en niños y gente joven, la preocupación por el que estos tratamientos focalizados en el trauma puedan ‘retraumatizar’ a los pacientes o exacerbar sus síntomas y causar abandono, ha sido identificada como una barrera para su implementación. El abandono del tratamiento es indicador de su aceptabilidad relativa en esta población.

Objetivo: Estimar la prevalencia de abandono en niños y gente joven que reciben una terapia psicológica para el TEPT como parte de un ensayo aleatorizado controlado (RCT en su sigla en inglés).

Métodos: Se realizó una búsqueda sistemática de la literatura para identificar RCTs de tratamientos basados en evidencia para el TEPT en niños y gente joven. Mediante metaanálisis de proporción se estimó la prevalencia de abandono. Los Odds Ratio compararon la probabilidad relativa de abandono entre diferentes tratamientos y controles. Mediante análisis de subgrupo se evaluó el impacto de potenciales variables moderadoras.

Resultados: Se identificaron cuarenta RCTs. El abandono de todas las ramas de tratamiento o control activo se estimó en 11.7%, IC de 95% [9.0, 14.6]. El abandono de tratamientos basados en la evidencia (TF-CBTs y EMDR) fue de 11.2%, IC de 95% [8.2, 14.6]. El abandono de tratamientos sin foco en trauma o controles fue de 12.8%, IC de 95% [7.6, 19.1]. No hubo diferencia significativa en la probabilidad de abandono al comparar las diferentes modalidades. La entrega en grupos Individual y por legos versus profesionales, se asociaron a menor abandono.

Conclusiones: Los tratamientos basados en evidencia para niños y gente joven con tept no resultan en una mayor prevalencia de abandono que los tratamientos sin foco en trauma o condiciones de lista de espera. las terapias focalizadas en el trauma parecen ser bien toleradas en niños y gente joven.

PALABRAS CLAVE: TEPT, abandono, psicoterapia, CBT, EMDR, aceptabilidad, TF-CBT, niños, adolescentes

Short abstract

背景: 尽管心理干预治疗儿童和年轻人 PTSD 的证据基础已经确立, 关于这些聚焦创伤治疗可能会‘再次伤害’患者或加剧症状并导致退出治疗的担忧, 已被识别为实施的障碍。从治疗退出表征其在该群体中的相对可接受性。

目的: 作为随机对照试验 (RCT) 的一部分, 估计接受 PTSD 心理治疗的儿童和年轻人的退出率。

方法: 对文献进行系统检索, 以确定儿童和年轻人 PTSD 循证治疗的 RCT。比例元分析估计了退出的发生率。 优势比比较了不同治疗组和对照组之间退出的相对可能性。亚组分析评估了潜在调节变量的影响。

结果: 确定了 40 个 RCT。所有治疗组或主动对照组中退出率估计值为 11.7%, 95% CI [9.0, 14.6]。循证治疗 (TFCBTs 和 EMDR) 的退出率为 11.2%, 95% CI [8.2, 14.6]。非聚焦创伤治疗或对照组的退出率为 12.8%, 95% CI [7.6, 19.1]。比较不同方式时, 退出率没有显著差异。团体而非个人方式, 以及非专业与专业方式, 退出率更低。

结论: 针对患有 PTSD 的儿童和年轻人的循证治疗不会导致比非聚焦创伤治疗或等待名单条件更高的退出率。聚焦创伤疗法似乎在儿童和年轻人中具有良好的耐受性。

关键词: PTSD, 退出, 心理治疗, CBT, EMDR, 可接受性, TF-CBT, 孩子, 年轻人

1. Introduction

Many children and adolescents are exposed to traumatic events throughout the world, with around 15.9% of those exposed going on to develop Post Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Alisic et al., 2014). PTSD is characterized by the re-experiencing of traumatic events, avoidance of reminders of the trauma, hypervigilance to threat and increased physiological arousal (International Classification of diseases for mortality and morbidity statistics (11th revision) (ICD-11) World Health Organization, 2019)). Untreated, PTSD can result in severely impaired social, academic and occupational functioning, which can persist into adulthood (Yule & Bolton, 2000). It is fortunate, therefore, that a number of psychological treatments have demonstrated efficacy in this area. In particular, a range of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural interventions, and to a slightly lesser extent, Eye Movement Desensitization and Reprocessing (EMDR) therapy have well-established empirical support confirmed by numerous meta-analyses (e.g. Gutermann et al., 2016; Mavranezouli et al., 2020; Morina, Koerssen, & Pollet, 2016). As such, they are the recommended treatment in a number of national treatment guidelines, e.g. the UK National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) which recommends trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapies as the first-line intervention, with EMDR to be considered for those who do not respond (NICE, 2018); and the International Society for Traumatic Stress Studies (ISTSS) who recommend both trauma focused cognitive behaviour therapy and EMDR as first-line interventions. (Bisson et al., 2019)

It has been widely noted, however, that despite this strong evidence base, there continues to be an under-utilization of these approaches in clinical settings (Borntrager, Chorpita, Higa-mcmillan, Daleiden, & Starace, 2013; Clark, Sprang, Freer, & Whitt-Woosley, 2010; Eslinger, Sprang, Ascienzo, & Silman, 2020; Finch, Ford, Grainger, & Meiser-Stedman, 2020a; Finch, Ford, Lombardo, & Meiser-Stedman, 2020b). Rates of young people dropping out from treatment for PTSD are significant (Dorsey et al., 2017). A number of authors have linked these two phenomena to suggest that concerns that some treatments may precipitate dropout may lead clinicians to avoid trauma-focused interventions (Borntrager et al., 2013; Feeny et al., 2003; Foa, Zoellner, Feeny, Hembree, & Alvarez-Conrad, 2002; Ruzek et al., 2014; Ruzek, Eftekhari, Crowley, Kuhn, & Karlin, 2017; van Minnen et al., 2010).

A definition of trauma-focused cognitive behavioural interventions can be found within the UK’s NICE guidance, which considers elaboration and processing of trauma-related memories and emotions, restructuring of trauma-related meanings for the child or young person, and help to overcome avoidance as key features (NICE Guideline NG116; 2018). This definition encompasses a range of treatments including Trauma-Focused Cognitive Behaviour Therapy (TFCBT), Cognitive Processing Therapy (CPT), Narrative Exposure Therapy (NET) and Prolonged Exposure Therapy (PE). The same guidelines recommend that clinicians consider EMDR for children and young people, if they do not respond to, or engage with, TFCBT (NICE Guideline NG116; 2018). Both approaches involve explicit exposure to the trauma memory, be it through ‘trauma narration’ (a detailed re-telling of event and accompanying thoughts and feelings), in vivo exposure to trauma-relevant objects or places, or imaginal exposure (bringing to mind and focusing on the details of the event). It is exposure techniques in particular, that have been most frequently implicated in the suggestion that some treatments can exacerbate symptoms and are particularly poorly tolerated in people with PTSD (Feeny et al., 2003; Foa et al., 2002; Lancaster et al., 2020; Larsen, Wiltsey Stirman, Smith, & Resick, 2016; Olatunji, 2009; Ruzek et al., 2014).).

To date, six meta-analyses have considered dropout from PTSD treatments in adults, with mixed results. Bradley, Greene, Russ, Dutra, and Weston (2005) reported some data that implied there was a difference in dropout rate between treatments that included exposure techniques and those that did not; however, this was not subject to formal analysis. Hembree et al. (2003) found no evidence of differential dropout rates from different treatments. Bisson et al. (2007) did find that there was more dropout from TFCBT than from usual care, but this difference no longer held once lower quality studies were removed. Goetter et al. (2015) conducted a meta-analysis studies related to US veterans in particular, finding that there was no difference in dropout between those treatments that involved exposure and those that did not. Imel, Laska, Jakupcak, and Simpson (2013) found that most direct comparisons between active treatments did not demonstrate significantly different dropout rates, except where trauma-focused treatment was compared with Present Centred Therapy (PCT), with PCT having a reduced likelihood of dropout. Finally, Lewis, Roberts, Gibson, and Bisson (2020) found that there was a statistically significant relationship between dropout and treatments with a greater trauma focus than those without, although the difference was small and dropout rates were still comparatively low (18% and 14%, respectively,). Taken together, it remains far from clear whether there is definitive evidence to conclude that some treatments carry a greater risk of dropout. To the authors’ knowledge, there has not yet been a meta-analysis which has considered this important question in relation to children and young people. This is important if clinicians are to make informed decisions about which treatment approach to select to promote the retention of children and young people in treatment, giving them the best chance of benefitting from the intervention.

The purpose of the current review is therefore to obtain an estimate of dropout rates for evidence-based PTSD treatments in children and young people and to ascertain whether there are different dropout rates across different treatment approaches (and in particular whether trauma-focused treatments are associated with increased rates of dropout among children and young people).

2. Methods

An overview of the proposed review was registered a priori with PROSPERO (CRD42019154257; 14 November 2019).

2.1. Search strategy

Three databases were systematically searched: PsycINFO, MEDLINE and Published International Literature on Traumatic Stress (PILOTS; now PTSDpubs). The following search terms were used:

(Post-traumatic Stress OR ‘Posttraumatic Stress’ OR Trauma* OR PTSD OR ‘Post Traumatic Stress’ OR P.T.S.D.) AND (child* OR young OR adolescen* OR youth OR pupil OR student OR teenage*) AND (psychotherapy OR therapy OR treat* OR therap* OR cognitive OR CBT OR C.B.T. OR EMDR OR ‘Eye Movement’ OR E.M.D.R. OR Reprocess* OR Desensiti* OR ‘Narrative Exposure’ OR ‘Exposure Therapy’) AND (control* OR clinical trial OR randomized OR randomized or Randomized Controlled).

2.2. Eligibility criteria

Results were limited to those in the English language and those published since 1980. This reflects the inclusion of PTSD in the third edition of the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders (APA, 1980).

Included studies were randomized controlled trials (RCTs) of evidence-based therapeutic interventions recommended by NICE, i.e. trauma-focused cognitive/behavioural or cognitive behavioural therapies or EMDR. Participants were required to have a diagnosis of PTSD (according to the DSM, the World Health Organization (WHO) International Classification of Diseases (ICD)) or clinically significant PTSD symptoms (baseline PTSD symptom scores above threshold on a validated scale). Studies had to have a mean age for participants that was 18 years old or younger. The event the symptoms relate to was required be a least 1 month prior to the start of treatment. To be included studies had to report sufficient data to compute dropout rates.

Studies were excluded if none of the treatment arms constituted a NICE recommended intervention (e.g. play therapy, family therapy, child-parent psychotherapy, parent training (alone), or supportive counselling). Studies were excluded if the interventions under consideration were not primarily treating trauma symptoms or had been delivered to a whole group who had not been individually clinically assessed as having PTSD symptoms (e.g. to a whole class). Preventative studies were excluded on the basis that they occur in a different context (i.e. in close proximity to the trauma) to treatment studies and may therefore elicit a different response that found in the context of symptoms that may have been present for a sustained period of time. Moreover, there is currently less evidence to support the efficacy of preventative interventions than that for treatment interventions (Marsac, Donlon, & Berkowitz, 2014).

2.3. Study selection

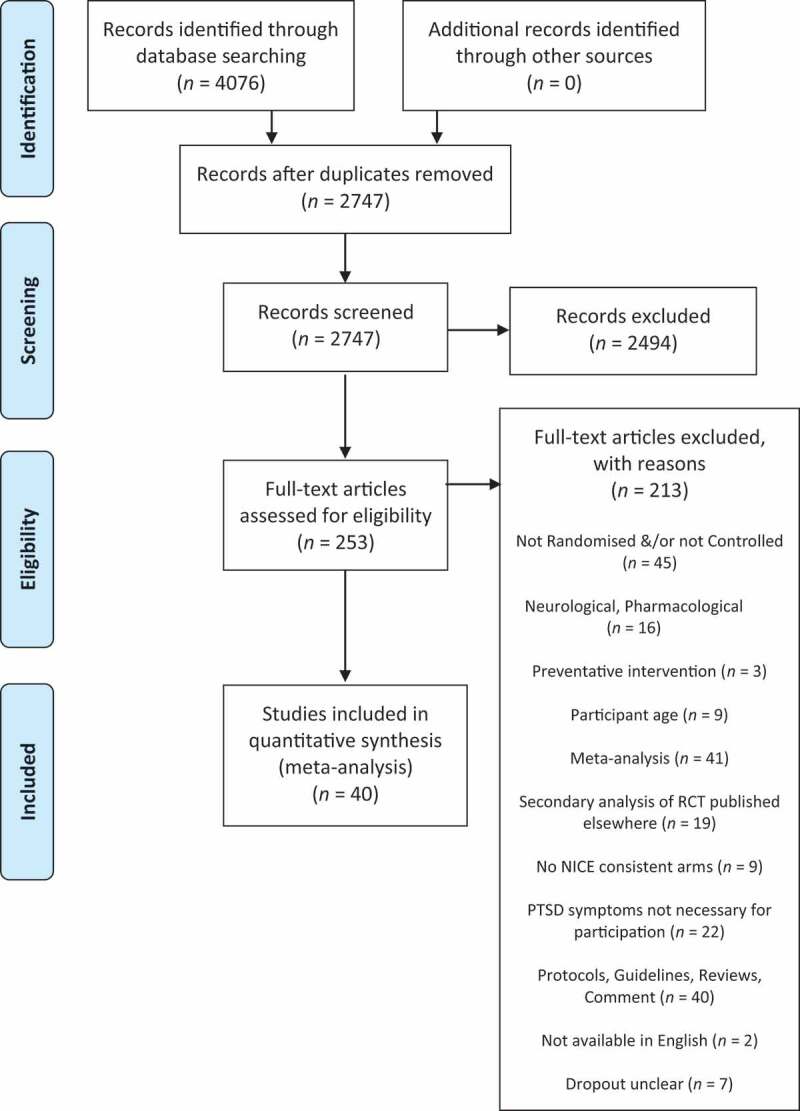

Searches produced a total of 4076 results. Once duplicates had been removed, there were 2747 records. Excluding those studies not in the English language further reduced the number of results by 147, leaving 2600. These were then screened by title and abstract with reference to the eligibility criteria. This process removed 2339 records. The full text for the remaining 261 were then retrieved for detailed screening. Concerns about eligibility were resolved through consensus discussion between the first and third author. This process produced a selection of 40 studies. All 40 included studies were then separately assessed for eligibility by the third author. A PRISMA flowchart detailing the screening and selection process is presented in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flowchart of study identification process

2.4. Study quality

Study quality was assessed with reference to a 10-point scale adapted from that which was used by Hoppen and Morina (2020) – itself an adaptation of that used by Cuijpers, van Straten, Bohlmeijer, Hollon, and Andersson (2010) – for their meta-analysis investigating study quality in the field of paediatric PTSD. One point was given for each of the following: (i) participants’ PTSD symptomology assessed personally via a clinical interview; (ii) the use of a treatment manual either published or specifically designed for the study; (iii) treatment delivered by therapists trained in the specific intervention either as part of the study or having had substantial prior experience; (iv) treatment integrity checked by, e.g., regular supervision, adherence checklists or recordings of treatment sessions being subjected to review; (v) intent-to-treat analysis; (vi) independent randomization process when allocating participants to different arms; and (vii) post-treatment assessment carried out by blind assessors.

Three further criteria were added to reflect the focus on dropout in the current study: (i) presentation of a CONSORT diagram (Schulz, Altman, & Moher, 2010), (ii) defined and explicit criteria for distinguishing dropout and treatment completion, i.e. the minimum number of sessions required to be considered to have received the treatment, and (iii) inclusion of details of the stage and/or reasons for dropout or where there was no dropout, that this was clearly stated.

Where there was insufficient information to determine whether the criterion was met, no point was awarded. All included studies were assessed for their quality by CS. A randomly generated subset of 50% of the studies was then assessed by HB. Cohen’s kappa was calculated to determine the degree of inter-rater reliability of the quality assessment as 0.72, suggesting substantial agreement (Landis & Koch, 1977). Differing scores were then resolved through discussion.

2.5. Data extraction

The following data were extracted from all included studies: authors, date and the country where study took place, whether the study concerned a specific event or category of trauma (e.g. an earthquake, or mass conflict); whether participants had experienced a single event trauma, or multiple trauma, or a mixture of the two; the age range and mean age of participants and the percentage of male and female participants, the treatment arms, including the number and length of sessions involved in each, the format (individual or group treatment), who delivered treatment, the proportion of participants who met diagnostic threshold for PTSD and the percentage of people who had dropped out from all arms in the study from the point of randomization.

2.6. Data analysis

The statistical analysis package Jamovi (Version 1.2) was used to carry out the analyses (The Jamovi Project, 2020. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org). Proportion meta-analyses were used to estimate the prevalence of dropout for all intervention arms and for subgroups of interventions. A random effects model was used in reflection of the anticipated heterogeneity between studies (Borenstein, Hedges, & Higgins, 2011). Estimates of prevalence of PTSD were arcsine square root transformed to prevent the confidence intervals of studies with low prevalence falling below zero (Barendregt, Doi, Lee, Norman, & Vos, 2013). Heterogeneity of effect sizes was assessed using Cochrane’s Q and Higgins’ I2. The first of these examines whether the variability of effect sizes is greater than would be expected by chance. The latter represents the proportion of the overall variability that is beyond sampling error (Borenstein et al., 2011).

Odds ratios were used to determine whether there was a greater likelihood of dropout for different classes of intervention (e.g. trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapies) and different types of control (i.e. active or inactive). Subgroup analyses (meta-regressions) were conducted to explore potential moderator variables: number of sessions, group or individual format, whether participants had experienced single incident or multiple traumas or a mixture of the two. Further meta-regressions were used to group interventions by modality (e.g. all TFCBT arms) and then compare them to all other intervention arms.

The above analyses were repeated using only those studies that provided an explicit definition of what constituted dropout. In light of the finding by Bisson et al. (2007) that an apparent relationship between treatment and dropout disappeared once lower quality studies were removed, sensitivity analyses repeated the above analyses having removed the studies that scored six or fewer in the quality assessment (nine studies removed).

3. Results

Forty studies met the inclusion criteria. A summary of the included studies is presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of included studies

| Authors, year | Country | Trauma type | Single incident, multiple or mixed | Interventions | Number of participants |

Format | Maximum duration weeks, sessions, (minutes) | Delivered by | Age range (mean) | Met PTSD diagnostic threshold at pre-treatment (%) | Male (%)/ Female (%) |

Dropout (%)a | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ahmad, Larsson, & Sundelin-Wahlsten, 2007 | Sweden | Various | Mixed | EMDR vs WL | 33 | Individual | 8, 8 (45) | Therapists (authors) | 6–16(10) | 100 | 41.2/58.8 | 9.1 | |

| Ahrens & Rexford, 2002 | USA | Violence | Mixed | CPT vs WL | 38 | Group | 8, 8 (60) | Experienced doctoral candidate and qualified psychologist | 15–18(16.4) | 100 | 100/0 | 0 | |

| Barron, Abdallah, & Heltne, 2016 | Palestine | Mass Conflict | Mixed | TRT vs WL | 154 | Group | n.r., 5 (60) | School counsellors | 11–18 (13.5) | 100 | 36.4/63.6 | 16.9 | |

| Catani et al., 2009 | Sri Lanka | Civil unrest, Tsunami | Mixed | KidNET vs MED-RELAX | 31 | Individual | 2, 6 (60–90) | Teachers trained as ‘master counsellors’ | 8–14(11.9) | n.r. | 54.8/45.2 | 0 | |

| Cohen et al., 2004 | USA | Sexual abuse | Mixed | TFCBT vs CCT | 229 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 12,12 (45) | Experienced therapist (social workers and psychologists) | 8–14(10.7) | 89 | 21.2/78.8 | 11.4 | |

| Cohen et al., 2011 | USA | Intimate Partner Violence | Mixed | TFCBT vs CCT | 124 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 8, 8 (45) | Social workers | 7–14 (9.6) | 25 | 49.2/50.8 | 39.5 | |

| Dawson et al., 2018 | Indonesia | Civil conflict | Mixed | TFCBT vs PS | 64 | Individual(with care-giver involvement) | 6, 6 (60) | Lay counsellors | 7–14 (10.4) | 75 | 51.5/48.5 | 0 | |

| de Roos et al., 2011 | Netherlands | Firework Factory explosion | Single incident | TFCBT vs EMDR | 52 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 8, 4 individual plus 4 parent (60) | Licenced therapists | 4–18(10.1) | 17.3 | 55.8/44.2 | 25.9 | |

| de Roos et al., 2017 | Netherlands | Various | Single incident | CBWT vs EMDR vs WL | 103 | Individual | Up to 6, 6 (45) | Clinical psychologists | 8–18 (13.1) | 61.2 | 42.7/57.3 | 3.9 | |

| Deblinger et al., 2011 | USA | Child sexual abuse | Mixed | TFCBT (with TN) vs TFCBT (without TN) | 210 | Individual(with caregiver involvement) | Either 8 or 16, 8 or 16, (90) | Graduates with 3+ years of clinical experience | 4–11 (7.7) | n.r. | 39/61 | 24.8 | |

| Diehle et al., 2015 | Netherlands | Various | Mixed | TFCBT vs EMDR | 48 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 8, 8 (60) | Experienced therapists | 8–18 (13) | 33 | 38/62 | 25 | |

| Ertl et al., 2011 | Uganda | Former child soldiers | Multiple | KidNET vs Academic catchup with SC | 85 | Individual | 3, 8 (90–120) | Lay counsellors | 12–25 (18) | 100 | 44.7/55.3 | 7.6 | |

| Foa, McLean, Capaldi, & Rosenfield, 2013 | USA | Child sexual abuse | Mixed | PE vs SC | 61 | Individual | 14,14 (60 − 90) | Masters-level counsellors | 13 − 18 (15.3) | 100 | 0/100 | 13.1 | |

| Ford et al., 2012 | USA | Various | Mixed | TARGET vs ETAU | 59 | Individual | n.r., 12 (50) | Experienced therapists with professional qualifications | 13–17 (14.7) | 62.8 | 0/100 | 27.1 | |

| Gilboa-Schechtman et al., 2010 | Israel | Various | Single Incident | PE-A vs TLDP | 38 | Individual | PE-A: 15,15 (90)TLDP: n.r., 18 (50) | ‘MA level clinicians’ | 12–18 (14.1) | 100 | 37/63 | 21.1 | |

| Goldbeck et al., 2016 | Germany | Various | Mixed | TFCBT vs WL | 159 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 12, 12 (90) | Therapist with advanced clinical training | 7–17 (13.0) | 75.5 | 28.3/71.7 | 1.9 | |

| Jaberghaderi et al., 2004 | Iran | Sexual abuse | Mixed | TFCBT vs EMDR | 18 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 12, 12 (45) | Clinical psychologist | 12–13 (n.r.) | n.r. | 0/100 | 21.1 | |

| Jaberghaderi et al., 2019 | Iran | Domestic Violence | Multiple | TFCBT vs EMDR | 40 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 12, 12 (60) | Experienced therapists (including author) | 8–12 (n.r.) | 100 | 50.4/49.6 | 23.8 | |

| Jensen et al., 2014 | Norway | Various | Mixed | TFCBT vs TAU | 156 | Individual(with parent involvement) | n.r., 15 (45) | Experienced therapist from mix of professions | (15.1) | 66.7 | 20.5/79.5 | 25 | |

| Kemp et al., 2010 | Australia | Motor vehicle accidents | Single incident | EMDR vs WL | 27 | Individual | 6, 4 (60) | Doctoral-level psychologist with advance training | 6–12(8.9) | n.r. | 55.6/44.4 | 11.1 | |

| King et al., 2000 | Australia | Child sexual abuse | Multiple | Child CBT vs Family CBT vs WL | 36 | Individual (child only)/Individual parent & child) | 20, 20 (50) | Registered psychologist | 5–17 (11.5) | 69.4 | 31/69 | 22.2 | |

| McMullen et al., 2013 | DR Congo | War | Mixed | TFCBT vs WL | 50 | Group | n.r., 15 (45) | Authors and experienced Congolese counsellors | 13–17 (15.8) | n.r. | 100/0 | 4 | |

| Meiser-Stedman et al., 2017 | UK | Various | Single incident | CT-PTSD vs WL | 29 | Individual | 10, 10 (90) | Clinical psychologists (including authors) | 8–17(13.3) | 100 | 27.8/72.2 | 10.3 | |

| Murray et al., 2015 | Zambia | Various | Mixed | TFCBT vs TAU | 257 | Individual | 16, 16 (90) | Lay counsellors | 5–18 (13.7) | n.r. | 50.2/49.8 | 9.7 | |

| Nixon et al., 2012 | Australia | Various | Single incident | TFCBT vs Cognitive Therapy (no exposure) | 34 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 9, 9 (90) | Trainee clinical psychologists | 7–17 (10.8) | 100 | 63.3/36.7 | 38.2 | |

| O’Callaghan et al., 2013 | DR Congo | War | Mixed | TFCBT vs WL | 52 | Group (plus x3 individual sessions & x3 caregiver sessions) | 5, 15, (120) | Social workers | 12–17 (16.1) | 60 | 0/100 | 11.5 | |

| O’Callaghan et al., 2015 | DR Congo | War | Mixed | TFCBT vs CFS | 50 | Group | 3, 9 (90) | Lay facilitators | 8–17 (14.8) | 92 | 58/42 | 0 | |

| Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019 | Finland | Various | Mixed | NET vs TAU | 50 | Individual | 10, 10 (9) | Experienced MH professionals | 9–17 (13.2) | n.r. | 58/42 | 14 | |

| Pityaratstian et al., 2015 | Thailand | Tsunami | Mixed | TRT (adapted) vs WL | 36 | Group | 0.4, 3 (120)b | Certified child psychiatrists (incl. author) | 10–15 (12.3) | 100 | 27.8/72.2 | 0 | |

| Robjant et al., 2019 | DR Congo | Former Child Soldiers | Multiple | FORNET vs TAU | 92 | Individual(plus x1 group session per week) | 6, 12 (120) | Lay people | 16–25 (18) | 100 | 0/100 | 0 | |

| Rosner et al., 2019 | Germany | Various | Mixed | D-CPT vs WL/TA | 88 | Group | 20, 30 (50) | Masters-level or postdoctoral therapists | 14–21 (18.1) | 100 | 15/85 | 21.6 | |

| Ruf et al., 2010 | Germany | Refugees | Multiple | KidNET vs WL | 26 | Group | 8, 8 (120) | Clinical psychologists | 7–16 (11.5) | 100 | 54/46 | 3.9 | |

| Salloum & Overstreet, 2012 | USA | Various | Mixed | GTI-CN vs GTI-C | 72 | Group (plus x1 individual & x1 parent session) | 10, 12 (60) | Social workers, social work interns, psychology doctoral student | 6–12 (9.6) | n.r. | 55.7/44.3 | 5.6 | |

| Santiago et al., 2014 | USA | Community Violence | Mixed | CBITS vs CBITS + Family | 64 | Group (plus 1–3 individual & 1–2 group sessions for parents) | n.r., 12 (50) | Social workers | 10–14 (11.7) | 100 | 41/59 | 0 | |

| Scheeringa et al., 2011 | USA | Various | Mixed | TFCBT vs WL | 64 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 12, 12 (50) | Social workers | 3–6 (5.3) | 24 | 66.2/33.8 | 29.7 | |

| Schottelkorb et al., 2012 | USA | Refugees | Mixed | TFCBT vs CCPT | 31 | Individual(with parent involvement) | TFCBT: 12, 20 (30)C0+: 12, 24 (30) | Masters-level student counsellors | 6–13 (9.1) | 58 | 54.8/45.2 | 16.1 | |

| Shein-Szydlo et al., 2016 | Mexico | Various | Mixed | TFCBT vs WL | 100 | Individual | 12, 12 (60) | Psychologists (Authors) | 12–19 (14.9) | 100 | 44/56 | 1 | |

| Smith et al., 2007 | UK | Various | Single incident | TFCBT vs WL | 24 | Individual(with parent involvement) | 10, 12 (n.r.) | Clinical psychologists | 8–18 (13.8) | 100 | 50/50 | 0 | |

| Stein et al., 2003 | USA | Violence | Mixed | CBITS vs WL | 126 | Group | 10, 10 (60) | School clinicians | n.r. (11) | n.r. | 43.7/56.3 | 9.5 | |

| Tol et al., 2008 | Indonesia | Civil conflict | Mixed | CBT-CBI vs WL | 403 | Group | 5, 15 (n.r.) | Local lay people | (9.9) | n.r. | 51.4/48.6 | 2.5 | |

EMDR, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; WL, waiting list; CPT , cognitive processing therapy; TRT, Teaching Recovery Techniques; KidNET, narrative exposure therapy for children; MED-RELAX, meditation and relaxation intervention; TFCBT, trauma-focused cognitive behaviour therapy; CCT, child-centred therapy; PS, problem solving intervention; CBWT, cognitive behavioural writing therapy; TN, trauma narrative; SC, supportive counselling; PE, prolonged exposure; TARGET, Trauma Affect Regulation: Guide for Education and Therapy; ETAU,enhanced treatment as usual (relationship supportive therapy); PE-A, prolonged exposure for adolescents; TLDP, time-limited psychodynamic therapy; TAU, treatment as usual; CBT,cognitive behavioural therapy; CT-PTSD, cognitive therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder; CFS,child friendly spaces; NET, narrative exposure therapy; FORNET, narrative exposure therapy adapted for offenders; WL/TA, waiting list with treatment advice; GTI-CN, grief and trauma intervention with coping skills and trauma narrative processing; GTI-C, grief and trauma intervention – coping skills only; CCPT, child centred play therapy; cbits=cognitive behavioural intervention for trauma in schools; CBT-CBI, cognitive behavioural therapy classroom-based Intervention; n.r. = not reported.

aDropout from all arms including waiting list. bIntervention delivered over three consecutive days followed by homework over the following month.

3.1. Sample characteristics

A total of 3413 children and young people were included in the identified studies, with sample sizes varying from 24 to 403. The approximate mean age of participants was 12.5 years, with the youngest age of eligibility being 3 years and the oldest being 25. An average 41.5% of participants were male and 58.5% were female. Seven studies included a single gender exclusively (two had only male participants and five had only female participants). Studies came from 18 different countries including the State of Palestine. Eleven studies were from the USA. Eight low- and middle-income Countries (LMIC; World Bank) and the State of Palestine, were represented accounting for 15 studies (37.5% of included studies).

Seven studies (17.5%) looked at single incident trauma (e.g. motor vehicle accident, house fire, single event sexual or non-sexual assault). Five (12.5%) specifically only included participants who had experienced multiple traumas (e.g. child sexual abuse, domestic violence, former child soldiers), while the majority (n= 28; 70%) included participants with a mixture of multiple and single incident traumas.

3.2. Nature of interventions delivered

Twelve (30%) studies primarily reported interventions delivered in a group format, although three of these studies also included adjunctive individual child and/or parent sessions.

Most interventions were delivered by professional therapists, social workers or trainees. Six studies (15%) involved interventions delivered by lay members of the community.

The shortest intervention (Pityaratstian et al., 2015) took place over 3 consecutive days; however, this was then followed by daily homework to complete over the subsequent month. The longest interventions took place over 20 weeks (Rosner et al., 2019; King et al., 2000). The mean number of sessions was 11.8 (SD, 5.2). The intervention with the fewest number of sessions was three (again Pityaratstian et al., 2015 as noted above) the highest maximum number of sessions was 30 (Rosner et al., 2019). Considering all arms of each study, including waiting list, the mean dropout was 12.7%. The highest reported dropout was 39%. Eight studies reported that they did not have any dropout at all (i.e. a rate of 0%).

The most frequently studied intervention was TFCBT, featuring in 21 RCTs (52.5%). NET was included in five studies (12.5%), PE, three (7.5%) and CPT two (5%). EMDR featured in seven trials (17.5%), four of which were a direct comparison between EMDR and TFCBT. Fourteen trials (35%) compared a trauma-focused treatment with an inactive, waiting list control arm alone. Fourteen trials (35%) compared a trauma-focused treatment with a non-trauma focused active control such as Child Centred Therapy, Supportive Counselling or Treatment as Usual. A further three studies compared two conditions, one of which contained explicit exposure or trauma narrative and one of which was the same but without this component (Deblinger et al., 2011; Nixon et al., 2012; Salloum & Overstreet, 2012). For the purposes of this analysis, these non-exposure or non-trauma narrative arms were treated as active control conditions. Although they would involve implicit exposure through the provision of, for example, psychoeducation about trauma reactions, they would not meet the criteria set out in the NICE Guidelines set about above (NICE Guideline NG116; 2018)

3.3. Definitions of dropout

Sixteen studies (40%) included a clear definition of dropout and/or the minimum number of attended sessions that would constitute treatment completion. These can be found in Table 2.

Table 2.

Studies with explicit definitions of dropout or completion

| Study | Definition of completion |

|---|---|

| Ahmad et al., 2007 | Three or more sessions of a possible eight |

| Cohen et al, 2004 | Three or more sessions of a possible 12 |

| Cohen et al, 2011 | Completion of all eight sessions |

| Dawson et al, 2018 | Completion of all five sessions |

| de Roos et al, 2011 | Completion of four sessions unless asymptomatic |

| de Roos et al, 2017 | Completion of six sessions or fewer if units of distress reduced to zero |

| Deblinger et al, 2011 | Three or more sessions of a possible 8 or 16 |

| Diehle et al, 2015 | Eight sessions but treatment could be concluded earlier if cured |

| Ertl et al, 2011 | Completion of all eight sessions |

| Foa et al., 2013 | Eight or more sessions of a possible 14 |

| Ford et al, 2012 | Five or more sessions of a possible 12 |

| Goldbeck et al, 2016 | Eight or more sessions |

| Jaberghaderi et al, 2004 | Ten or more sessions of TFCBT No minimum for EMDR |

| Jaberghaderi et al, 2019 | Five or more sessions of a possible 12 |

| Jensen et al, 2014 | Six or more sessions |

| Peltonen & Kangaslampi, 2019 | Seven or more sessions |

3.4. Study quality

The quality of all studies was assessed with reference to the 10 criteria outlined above. A total quality score was calculated by summing the scores for each indicator. The average score was 7.8 (SD = 1.6). The scores for each criterion in each study are presented in Supplementary Figure S1.

3.5. Proportion meta-analyses

The results from the proportion meta-analyses are presented in Table 3. Heterogeneity was large (I2 > 59%) and significant in all instances. The estimated dropout across all treatment arms (any treatment or active control, excluding only waiting list conditions) was 11.7% (k = 66, 95% CI 9.0, 14.6). The forest plot (Supplementary Figure S2) shows dropout rates with 95% confidence intervals. A second proportion meta-analysis considered treatment or control arms from only those studies that had defined dropout (k = 32); this yielded an increase in dropout (15.9%; 95% CI 12.0, 20.2).

Table 3.

Results of proportion meta-analyses

| 95% CI |

Heterogeneity statistics |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | k | N | Prevalence (%) | LI | UL | Q | df | p | I2 (%) |

| Dropout from all treatment arms excluding WL | 66 | 2658 | 11.7 | 9.0 | 14.6 | 326.5 | 65 | <0.001 | 79.0 |

| Lower quality removed | 53 | 2383 | 11.6 | 8.8 | 14.8 | 286.7 | 52 | <0.001 | 80.7 |

| Defined dropout | 32 | 1386 | 15.9 | 12.0 | 20.2 | 132.0 | 31 | <0.001 | 76.1 |

| Dropout from all TFCBT arms | 41 | 1696 | 10.6 | 7.5 | 14.2 | 206.1 | 40 | <0.001 | 79.3 |

| Lower quality removed | 31 | 1457 | 10.1 | 6.7 | 14.0 | 166.8 | 30 | <0.001 | 80.1 |

| Defined dropout | 16 | 778 | 14.7 | 9.4 | 20.9 | 70.1 | 15 | <0.001 | 78.7 |

| Dropout from all TFCBT and EMDR arms | 48 | 1869 | 11.2 | 8.2 | 14.6 | 226.5 | 47 | <0.001 | 77.6 |

| Lower quality removed | 36 | 1608 | 10.8 | 7.6 | 14.5 | 186.7 | 35 | <0.001 | 79.2 |

| Defined dropout | 22 | 891 | 15.2 | 10.6 | 20.4 | 85.3 | 21 | <0.001 | 74.9 |

| Dropout from all EMDR arms | 7 | 173 | 15.5 | 7.8 | 25.3 | 15.7 | 6 | 0.015 | 59.0 |

| Lower quality removed | 5 | 151 | 16.2 | 6.9 | 28.5 | 14.7 | 4 | 0.005 | 70.1 |

| Defined dropout | 6 | 160 | 16.7 | 8.0 | 27.8 | 15.1 | 5 | 0.010 | 63.6 |

| Dropout from all non-trauma focussed armsa | 18 | 789 | 12.8 | 7.6 | 19.1 | 90.1 | 17 | <0.001 | 82.4 |

| Lower quality removed | 17 | 775 | 13.4 | 7.9 | 20.0 | 87.8 | 16 | <0.001 | 83.1 |

| Defined dropout | 10 | 495 | 17.4 | 10.5 | 25.6 | 43.4 | 9 | <0.001 | 79.2 |

WL, waiting list; TFCBT, trauma-focused cognitive behavioural therapies; EMDR, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing.

aAll active control arms, non-NICE recommended psychotherapies and the arms from component studies with exposure or trauma narrative elements removed.

A series of further proportion meta-analyses examined dropout for particular modalities of treatment, and when using only those studies which defined dropout and when removing studies rated to have low quality (see Table 3). Drop rates were low in each case (<18%), increasing slightly when restricting results to studies when defined dropout. There appeared to be little impact of removing low quality studies.

3.6. Odds ratios

Odds ratios were calculated to determine the relative likelihood of dropout between different classes of intervention and control arms. The results are presented in Table 4. There were no instances of statistically significant difference between experimental and control conditions. Moreover, these results were not accompanied by heterogeneity.

Table 4.

Odds ratios of dropout from different types of intervention

| |

95% CI |

Heterogeneity statistics |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | k | N | Odds ratio | LL | UL | p | Q | df | p | I2 (%) |

| TFCBT vs any active control | 22 | 1848 | 0.89 | 0.68 | 1.17 | 0.398 | 12.2 | 21 | 0.935 | 0 |

| Lower quality removed | 20 | 1799 | 0.87 | 0.66 | 1.14 | 0.398 | 9.1 | 19 | 0.972 | 0 |

| Defined dropout | 15 | 1337 | 0.85 | 6.23 | 1.15 | 0.398 | 8.0 | 14 | 0.889 | 0 |

| EMDR vs any active control | 5 | 283 | 1.03 | 0.54 | 1.93 | 0.938 | 1.3 | 4 | 0.870 | 0 |

| Lower qualityremoved | 4 | 265 | 1.03 | 0.53 | 1.99 | 0.938 | 1.3 | 3 | 0.741 | 0 |

| Defined dropouta | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TFCBT or EMDR vs WL | 17 | 1417 | 1.01 | 0.50 | 2.04 | 0.975 | 25.9 | 16 | 0.055 | 42.3 |

| Lower quality removed | 12 | 1153 | 1.22 | 0.33 | 2.03 | 0.975 | 17.7 | 11 | 0.088 | 42.2 |

| Defined dropoutb | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| TFCBT or EMDR vs active controlc | 14 | 1299 | 0.88 | 0.63 | 1.21 | 0.424 | 7.7 | 13 | 0.863 | 0 |

| Lower quality removed | 13 | 1268 | 0.85 | 0.61 | 1.18 | 0.424 | 4.6 | 12 | 0.971 | 0 |

| Defined dropout | 8 | 800 | 0.83 | 0.57 | 1.21 | 0.424 | 4.5 | 7 | 0.720 | 0 |

| Component studiesd | 4 | 314 | 0.81 | 0.42 | 1.55 | 0.518 | 2.0 | 3 | 0.581 | 0 |

| Lower dropout removeda | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

| Defined dropoutb | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - | - |

LL, lower limit; UL, upper limit; CBT, cognitive behavioural therapies; EMDR, eye movement desensitization and reprocessing; WL, waiting list.

aAnalysis not conducted because there were too few eligible arms (k = 2). bSame as the analysis above. cExcludes component studies and EMDR vs TFCBT studies. dArms with exposure/trauma narrative component vs arms with those elements removed.

3.7. Subgroup and moderator analyses

Proportion meta-analyses were conducted for subgroups and then meta-regressions were conducted in order to explore whether any predictor of dropout could be identified. Results are presented in Table 5. Two moderators produced statistically significant results. The first was individual versus group format: group interventions were associated with fewer dropouts. This continued to be the case once lower quality studies were removed. It was not possible to examine if this held true when considering only those studies that had defined dropout because doing this removed all of the group arms. The second statistically significant association related to whether the intervention was delivered by lay people from local communities or by professional therapists; interventions delivered by lay people were associated with significantly fewer participants dropping out. This continued to be the case when lower quality studies were removed, and when considering only those studies that defined dropout. No relationship was found between dropout rate and type of trauma (single vs multiple), intervention (TFCBT vs other, TFCBT & EMDR vs other) or number of sessions.

Table 5.

Proportion dropout meta-analyses for each active arm: subgroup and moderator analyses

| 95% CI |

Heterogeneity statistics |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Analysis | k | N | Dropout prevalence (%) | LL | UL | Q | df | p | I2 (%) |

| Individual vs group | |||||||||

| Individual armsa | 53 | 2067 | 14.2 | 11.0 | 17.6 | 218.3 | 52 | <0.001 | 76.9 |

| Group armsa | 13 | 591 | 4.0 | 1.8 | 7.1 | 34.9 | 12 | <0.001 | 59.7 |

| Test of moderation, p< .001; defined drop only, n/ab; lower quality studies removed, p = .005 | |||||||||

| Multiple vs single trauma | |||||||||

| Multiple/mixed trauma arms | 55 | 2410 | 11.1 | 8.4 | 14.2 | 286.0 | 54 | <0.001 | 79.9 |

| Single trauma arms | 11 | 248 | 15.1 | 7.6 | 24.7 | 38.9 | 10 | <0.001 | 72.3 |

| Test of moderation, p= .345; defined drop only, p = .322; lower quality studies removed, p = .269 | |||||||||

| Lay vs professional therapist | |||||||||

| Lay delivered arms | 13 | 628 | 4.1 | 1.8 | 7.4 | 40.0 | 12 | <0.001 | 64.3 |

| Professional delivered arms | 53 | 2030 | 14.0 | 11.0 | 17.4 | 212.1 | 52 | <0.001 | 76.2 |

| Test of moderation, p= .003; defined drop only, p = .027; lower quality studies removed, p = .001 | |||||||||

| Number of sessions | |||||||||

| Test of moderation, p= .461; defined drop only, p = .434; lower quality studies removed, p = .914 | |||||||||

| CBT vs otherc | |||||||||

| Test of moderation, p= .317; defined drop only, p = .548; lower quality studies removed, p = .214 | |||||||||

| CBT or EMDR vs otherc | |||||||||

| Test of moderation, p= .612; defined drop only, p = .624; lower quality studies removed, p = .446 | |||||||||

aExperimental or control arms. bNot applicable, as no eligible arms. cSubgroup data available in Table 2.

3.8. Publication bias

Visual inspection of the funnel plots related to the above analyses did not show evidence of publication bias (Page, Higgins, & Sterne, 2020).

4. Discussion

There has been well documented under-utilization of trauma-focused treatments and exposure techniques to treat PTSD despite their significant evidence-base. This has been linked to perceptions among clinicians about the potential adverse effects of these approaches, their potential for worsening symptoms and a consequent increased risk of dropout from treatment (e.g. Finch et al., 2020a). This study pooled data from 40 RCTs regarding PTSD treatment in this population. Results found that dropout from RCTs has tended to be relatively low, with all dropout estimates below 15.5%. These compare favourably with the mean dropout rate (28.4%) found by de Haan, Boon, de Jong, Hoeve, and Vermeiren (2013) in their meta-analysis of children and young people dropping out from treatment in psychotherapy efficacy studies, and are in a similar order to the recent meta-analytic findings of dropout among children and young people from psychotherapeutic interventions for depression (14.9%) (Wright, Mughal, Bowers, & Meiser-Stedman, 2021). They are also comparable to recent adult population meta-analyses that related specifically to PTSD: 16% (Lewis et al., 2020) and 18% (Imel et al., 2013). However, heterogeneity was large in all cases, suggesting that there was high degree of variability in dropout rates across studies.

Odds ratios were used to examine whether there were differences in the likelihood of dropout from different conditions when directly compared. In these analyses, there was no evidence of significant heterogeneity across studies. No type of intervention or control condition was associated with significantly greater or lesser odds of dropout, including dropout from inactive control (waiting list) conditions.

Different potential moderators of dropout were considered. Of these, group or individual format, and who delivered the intervention were significant. In contrast to adult population studies which have found group treatments to be either associated with higher dropout (Goetter et al., 2015; Imel et al., 2013) or not to be significant (Lewis et al., 2020), this review found that children and young people were less likely to dropout from group treatment. This finding was unexpected, and we can only offer speculative explanations for this effect. Children and young people may be more used to, and comfortable in, group settings, and there may be less pressure to discuss their own trauma experiences in detail. They often accessed group treatment by virtue of their participation in other systems and apparatus such as their school or via Non-Governmental Organizations established in local communities. LMIC were over-represented in the group interventions, making up 50% of group interventions but only 37.5% of the total sample. There may be additional factors in these contexts that promote attendance, such as access to other services and assistance or a paucity of alternative sources of support in situations of mass displacement, conflict or disaster. Alternatively, the peer-oriented support that may be available may through group intervention may be of particular value to children and adolescents; indeed, this would reflect the wider literature that speaks to the protective effects of peer support in youth (e.g. Yearwood, Vliegen, Chau, Corveleyn, & Luyten, 2019). It may be important to note that this finding is in contrast to the lack of difference between individual and group-based interventions observed for dropout from psychological treatments for depression in children and adolescents (Wright et al., 2021).

Delivery of interventions by lay members of the community who had been trained to deliver the treatment was also associated with lower dropout. Lay-delivered interventions all took place in LMIC contexts. Lay people may bring cultural knowledge and credibility that enhances participation. This finding is promising in that it supports the vision espoused by the World Health Organization (WHO) of nonspecialised healthcare workers being critical in meeting the demand for mental health interventions around the world (mhGap Intervention Guide for mental, neurological and substance use disorders in non-specialized health settings; WHO, 2010). It is encouraging to note that while professionals have identified the need for additional training as a potential barrier to implementing trauma-focused treatments (Finch et al., 2020b), these needs may be met with relatively modest input given the success of these studies in utilizing lay facilitators.

Study quality did not appear to affect the results. However, using only those studies which had explicitly defined dropout consistently yielded a higher dropout rate. One might expect that defining dropout could reduce the number of participants considered to have dropped out, as compared to inferring dropout rate from the difference between the number randomized and the number who participated in post-treatment assessment. In the first instance, someone could be considered to have completed treatment after only having taken part in a relatively fewer sessions and in the latter, someone could have attended all or almost all planned sessions but be absent only from post-assessment and still designated as having dropped out. Instead, our analysis found the reverse. If a lot of dropout occurs at the beginning of treatment, one might expect that there would be little difference between studies that defined dropout and those that did not, as early leavers from treatment would be captured in either instance. Therefore, these findings may imply that dropout tended to occur later in treatment, but this would require further research to explore. It may be that the fact dropout was considered a priori indicated a greater level of attention was given to the issue of dropout and therefore a more stringent approach to identifying dropouts was adopted.

4.1. Strengths and limitations

There are a number of limitations to this study. As noted above, inferring dropout from the numbers of participants that were randomized and at post-treatment assessment is imperfect. There may be people who were present at post-treatment assessment who had not attended all or most of the treatment sessions. Conversely, there may be people missing from post-treatment assessment who did attend the treatment sessions and were missing from post-assessment for some other reason. Dropout at an early stage might be associated with quite different factors to that which accompany dropout at a later stage in therapy, including that some later dropout might represent some ‘early responders’ (Szafranski, Smith, Gros, & Resick, 2017).

Moreover, it has been consistently found that dropout from RCTs is less than in naturalistic settings (de Haan et al., 2013). This has been linked to the exclusion criteria for participation in RCTs, which is frequently seen to skew the sample away from comorbidity or complexity (Schottenbauer, Glass, Arnkoff, Tendick, & Gray, 2008). This may limit the applicability of these findings to other settings. Studies concerned with ‘real-world’ settings have found evidence of high rates of dropout from trauma-focused treatment, an outcome that is frequently found to be just as likely as the possibility of completing treatment (e.g. Steinberg et al., 2019, Murphy et al., 2014). One explanation for these differences would be that the samples enrolled into clinical trials are more homogeneous than those who utilize standard community services, with RCTs exclusion criteria tending to skew the sample away from comorbidity or complexity (Schottenbauer et al., 2008). There are methodological, practical and ethical reasons for this. Importantly, the more homogenous the sample, the easier it is to draw conclusions about treatment efficacy, which is rightfully the business of RCTs to address (see Schnurr (2007) for a more detailed discussion of this). However, it is important to recognize that the range of contexts and populations covered by the trials reviewed here does include diverse, complex and challenging contexts, including people who have encountered multiple and profound trauma on a mass scale or over long periods. Given what we understand about the impact of these experiences (Dorsey et al., 2017), one might suspect that comorbidity was high in some of these samples, whether or not there was a mental health infrastructure to identify it, or cultural schema to construe it, as such.

The diversity of included studies may be a further limitation, in that the statistical heterogeneity between studies was high. This reflects the wide-ranging locations, treatments, format, duration and facilitators, and necessitates caution when pooling data in this way. The advantage of this pooling is that it allows for well-powered analysis in a context where there are often low numbers from individual studies.

When it comes to retention, however, RCTs may have numerous advantages compared to usual care settings. There may be incentives to families to remain in the study, and there may be greater resources available to follow up absences or prompt attendance. Knowledge that one is involved in a trial may engender greater hope for change, motivating engagement. Other potential differences are greater fidelity to protocols and access to focused, timely supervision that supports this; differences in the skill, experience or confidence of those delivering interventions; differences in time and resources available or presence and promotion of explicit strategies to retain people in treatment; or differences in the profile of the people being treated (for example, symptom severity, co-morbidity, economic and social resources, attitudes and cultural identity).

Encouragingly, there is some evidence to suggest that even quite modest retention strategies can be effective. For example, Dorsey et al. (2014) augmented TFCBT for children placed in foster homes, with an initial phone-call to foster carers which directly discussed potential barriers, caregiver concerns and problem solving around barriers; these matters were revisited with the family at the initial face-to-face appointment. This engagement strategy was not found to make a difference to the likelihood of first appointment attendance or to the number of cancelled sessions. However, families who received the additional engagement strategy phone call were more likely to receive four or more sessions than those who did not (96.0% vs 72.7%, respectively,) and a startling 80% of completed treatment, compared to 40.9% those in the standard condition.

Research in this area would benefit from a consistent definition being adopted which would allow for greater confidence in drawing comparisons across studies. If trials are reported as standard, the definition used for treatment completion (whether expressed as a number of sessions or as the core components of the protocol that are required to have been delivered), and the known reasons for any dropout and the stage at which it occurred, the robustness of future analyses of this kind will much bolstered.

This study designated interventions as either being trauma-focused and NICE consistent (i.e. involving explicit exposure) or not. It is likely that rather than dichotomous categories, the degree of exposure utilized by different trauma-focused approaches varies along a spectrum in a way that is not captured here. Reporting greater detail about the degree of explicit exposure contained within treatment conditions would also support further research in this area. Similarly, ‘catch-all’ categories for control conditions are also imperfect. ‘Treatment as usual’ controls often vary considerably, and these were then grouped with other active psychotherapeutic approaches. Categorizing studies in this way is likely to obscure real differences in the type and intensity of the interventions provided and therefore risks missing important information about the treatment experiences of these young people.

5. Conclusion

While it is difficult to be confident about the reasons for dropout, the picture found here overall is one of high levels of retention in psychological therapies for PTSD in children and young people, suggesting that these treatments are broadly well tolerated. Our absolute estimates of dropout were accompanied by a large degree of heterogeneity, limiting the generalizability of this conclusion. Nevertheless, our analyses of RCTs suggested that there was no evidence for different dropout rates when making comparison to control conditions.

Supplementary Material

Data availability statement

Data sharing is not applicable to this article as no new data were created or analysed in this study.

Disclosure statement

No potential conflict of interest was reported by the author(s).

Ethical considerations

No ethical approval was gained – all data were secondary published data.

Supplementry material

Supplemental data for this article can be accessed here.

References

- Ahmad, A., Larsson, B., & Sundelin-Wahlsten, V. (2007). EMDR treatment for children with PTSD: Results of a randomized controlled trial. Nordic Journal of Psychiatry, 61(5), 349–17. doi: 10.1080/08039480701643464 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ahrens, J., & Rexford, L. (2002). Cognitive processing therapy for incarcerated adolescents with PTSD. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 6(1), 201–216. doi: 10.1300/J146v06n01_10 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Alisic, E., Zalta, A. K., van Wesel, F., Larsen, S. E., Hafstad, G. S., Hassanpour, K., & Smid, G. E. (2014). Rates of post-traumatic stress disorder in trauma-exposed children and adolescents: Meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 204(5), 335–340. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.113.131227 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychiatric Association. (1980). Diagnostic and statistical manual of mental disorders (Vol. 3). Washington, DC: American Psychiatric Association.

- Barendregt, J. J., Doi, S. A., Lee, Y. Y., Norman, R. E., & Vos, T. (2013). Meta-analysis of prevalence. Journal of Epidemiology and Community Health, 67(11), 974–978. doi: 10.1136/jech-2013-203104 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barron, I., Abdallah, G., & Heltne, U. (2016). Randomized control trial of Teaching Recovery Techniques in rural occupied Palestine: Effect on adolescent dissociation. Journal of Aggression, Maltreatment & Trauma, 25(9), 955–973. doi: 10.1080/10926771.2016.1231149 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, J. I., Berliner, L., Cloitre, M., Forbes, D., Jensen, T. K., Lewis, C., … Shapiro, F. (2019). The international society for traumatic stress studies new guidelines for the prevention and treatment of PTSD: Methodology and development process. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 32(4), 475–483. doi: 10.1002/jts.22421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisson, J. I., Ehlers, A., Mathews, R., Pilling, S., Richards, D., & Turner, S. (2007). Psychological treatments for chronic post-traumatic stress disorder: Systematic review and meta-analysis. The British Journal of Psychiatry, 190(2), 97–104. doi: 10.1192/bjp.bp.106.021402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borenstein, M., Hedges, L. V., & Higgins, J. P. T. (2011). Introduction to meta-analysis. Hoboken: John Wiley & Sons, Incorporated. ProQuest Ebook Central. [Google Scholar]

- Borntrager, C., Chorpita, B. F., Higa-mcmillan, C. K., Daleiden, E. L., & Starace, N. (2013). Usual care for trauma-exposed youth: Are clinician-reported therapy techniques evidence-based? Children and Youth Services Review, 35(1), 133–141. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2012.09.018 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley, R., Greene, J., Russ, E., Dutra, L., & Weston, D. (2005). A multidimensional meta-analysis of psychotherapy for PTSD. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 162(2), 214–227. doi: 10.1176/appi.ajp.162.2.214 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Catani, C., Kohiladevy, M., Ruf, M., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2009). Treating children traumatized by war and tsunami: A comparison between exposure therapy and meditation-relaxation in North-East Sri Lanka. BMC Psychiatry, 9, 22. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-9-22 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Clark, J. J., Sprang, G., Freer, B., & Whitt-Woosley. (2010). ‘Better than nothing’ is not good enough: Challenges introducing evidence-based approaches for traumatized populations. Journal of Evaluation in Clinical Practice, 18(2), 352–359. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2753.2010.01567.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A., Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., & Steer, R. A. (2004). A multisite, randomized controlled trial for children with sexual abuse-related PTSD symptoms. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 43(4), 393–402. doi: 10.1097/01.chi.0000111364.94169.f9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cohen, J. A., Mannarino, A. P., & Iyengar, S. (2011). Community treatment of posttraumatic stress disorder for children exposed to intimate partner violence a randomized controlled trial. Archives of Pediatrics & Adolescent Medicine, 165(1), 16–21. doi: 10.1001/archpediatrics.2010.247 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuijpers, P., van Straten, A., Bohlmeijer, E., Hollon, S. D., & Andersson, G. (2010). The effects of psychotherapy for adult depression are overestimated: A meta-analysis of study quality and effect size. Psychological Medicine, 40(2), 211–223. doi: 10.1017/S0033291709006114 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson, K., Joscelyne, A., Meijer, C., Steel, Z., Silove, D., & Bryant, R. A. (2018). A controlled trial of trauma-focused therapy versus problem-solving in Islamic children affected by civil conflict and disaster in Aceh, Indonesia. Australian & New Zealand Journal of Psychiatry, 52(3), 253–261. doi: 10.1177/0004867417714333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Haan, A. M., Boon, A. E., de Jong, J. T. V. M., Hoeve, M., & Vermeiren, R. R. J. M. (2013). A meta-analytic review on treatment dropout in child and adolescent outpatient mental health care. Clinical Psychology Review, 33(5), 698–711. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2013.04.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de Roos, C., Greenwald, R., den Hollander-Gijsman, M., Noorthoorn, E., van Buuren, S., & de Jongh, A. (2011). A randomized comparison of cognitive behavioral therapy (CBT) and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) in disaster-exposed children. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 2, 5694. doi: 10.3402/ejpt.v2i0.5694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- de Roos, C., van der Oord, S., Zijlstra, B., Lucassen, S., Perrin, S., Emmelkamp, P., & de Jongh, A. (2017). Comparison of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing therapy, cognitive behavioral writing therapy, and wait-list in pediatric posttraumatic stress disorder following single-incident trauma: A multicenter randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(11), 1219–1228. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12768 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Deblinger, E., Mannarino, A. P., Cohen, J. A., Runyon, M. K., & Steer, R. A. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children: Impact of the trauma narrative and treatment length. Depression and Anxiety, 28(1), 67–75. doi: 10.1002/da.20744 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diehle, J., Opmeer, B. C., Boer, F., Mannarino, A. P., & Lindauer, R. J. L. (2015). Trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy or eye movement desensitization and reprocessing: What works in children with posttraumatic stress symptoms? A randomized controlled trial. European Child & Adolescent Psychiatry, 24(2), 227–236. doi: 10.1007/s00787-014-0572-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, S., McLaughlin, K. A., Kerns, S. E. U., Harrison, J. P., Lambert, H. K., Briggs, E. C., Revillion Cox, J., & Amaya-Jackson, L. (2017). Evidence base update for psychosocial treatments for children and adolescents exposed to traumatic events. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 46(3), 303–330. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2016 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dorsey, S., Pullmann, M. D., Berliner, L., Koschmann, E., McKay, M., & Deblinger, E. (2014). Engaging foster parents in treatment: A randomized trial of supplementing Trauma-focused Cognitive Behavioral Therapy with evidence-based engagement strategies. Child Abuse & Neglect, 38(9), 1508–1520. doi: 10.1016/j.chiabu.2014.03.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ertl, V., Pfeiffer, A., Schauer, E., Elbert, T., & Neuner, F. (2011). Community-implemented trauma therapy for former child soldiers in Northern Uganda: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 306(5), 503–512. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.1060 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eslinger, J., Sprang, G., Ascienzo, S., & Silman, M. (2020). Fidelity and sustainability in evidence-based treatments for children: An investigation of implementation determinants. Journal of Family Social Work, 23(2), 177–196. doi: 10.1080/10522158.2020.1724581 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Feeny, N. C., Hembree, E. A., & Zoellner, L. A. (2003). Myths regarding exposure therapy for PTSD. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 10(1), 85–90. doi: 10.1016/S1077-7229(03)80011-1 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J., Ford, C., Grainger, L., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2020a). A systematic review of the clinician related barriers and facilitators to the use of evidence-informed interventions for post traumatic stress. Journal of Affective Disorders, 263, 175–186. doi: 10.1016/j.jad.2019.11.143 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Finch, J., Ford, C., Lombardo, C., & Meiser-Stedman, R. (2020b). A survey of evidence-based practice, training, supervision and clinician confidence relating to post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) therapies in UK child and adolescent mental health professionals. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1), 1815281. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2020.1815281 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., McLean, C. P., Capaldi, S., & Rosenfield, D. (2013). Prolonged exposure vs supportive counselling for sexual abuse-related PTSD in adolescent girls a randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association, 310(24), 2650–2657. doi: 10.1001/jama.2013.282829 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Foa, E. B., Zoellner, L. A., Feeny, N. C., Hembree, E. A., & Alvarez-Conrad, J. (2002). Does imaginal exposure exacerbate PTSD symptoms? Journal of Consulting & Clinical Psychology, 70(4), 1022. doi: 10.1037/0022-006X.70.4.1022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ford, J. D., Steinberg, K. L., Hawke, J., Levine, J., & Zhang, W. (2012). Randomized trial comparison of emotion regulation and relational psychotherapies for PTSD with girls involved in delinquency. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 41(1), 27–37. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2012.632343 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilboa-Schechtman, E., Foa, E. B., Shafran, N., Aderka, I. M., Powers, M. B., Rachamim, L., & Apter, A. (2010). Prolonged exposure versus dynamic therapy for adolescent PTSD: A pilot randomized controlled trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 49(10), 1034–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2010.07.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goetter, E. M., Bui, E., Ojserkis, R. A., Zakarian, R. J., Brendel, R. W., & Simon, N. M. (2015). A systematic review of dropout from psychotherapy for Posttraumatic Stress Disorder among Iraq and Afghanistan combat veterans. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 28(5), 401–409. doi: 10.1002/jts.22038 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldbeck, L., Muche, R., Sachser, C., Tutus, D., & Rosner, R. (2016). Effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for children and adolescents: A randomized controlled trial in eight German mental health clinics. Psychotherapy and Psychosomatics, 85(3), 159–170. doi: 10.1159/000442824 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gutermann, J., Schreiber, F., Matulis, S., Schwartzkopff, L., Deppe, J., & Steil, R. (2016). Psychological treatments for symptoms of Posttraumatic Stress Disorder in children, adolescents, and young adults: A meta-analysis. Clinical Child and Family Psychology Review, 19(2), 77–93. doi: 10.1007/s10567-016-0202-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hembree, E. A., Foa, E. B., Dorfan, N. M., Street, G. P., Kowalski, J., & Tu, X. (2003). Do patients drop out prematurely from exposure therapy for PTSD? Journal of Traumatic Stress, 16(6), 555–562. doi: 10.1023/B:JOTS.0000004078.93012.7d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hoppen, T. H., & Morina, N. (2020). Is high-quality of trials associated with lower treatment efficacy? A meta-analysis on the association between study quality and effect sizes of psychological interventions for pediatric PTSD. Clinical Psychology Review, 78, 101855. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2020.10185 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Imel, Z. E., Laska, K., Jakupcak, M., & Simpson, T. L. (2013). Meta-analysis of dropout in treatments for posttraumatic stress disorder. Journal of Consulting and Clinical Psychology, 81(3), 394–404. doi: 10.1037/a0031474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaberghaderi, N., Greenwald, R., Rubin, A., Zand, S. O., & Dolatabadi. (2004). A comparison of CBT and EMDR for sexually-abused Iranian girls. Clinical Psychology and Psychotherapy, 11(5), 358–368. [Google Scholar]

- Jaberghaderi, N., Rezaei, M., Kolivand, M., & Shokoohi, A. (2019). Effectiveness of ognitive behavioral therapy and eye movement desensitization and reprocessing in child victims of domestic violence. Iranian Journal of Psychiatry, 14(1), 67–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jamovi . (2020). The Jamovi Project (Version 1.2) [Computer Software]. Retrieved from https://www.jamovi.org [Google Scholar]

- Jensen, T. K., Holt, T., Ormhaug, S. M., Egeland, K., Granly, L., Hoaas, L. C., & Wentzel-Larsen, T. (2014). A randomized effectiveness study comparing trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy with therapy as usual for youth. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 43(3), 356–369. doi: 10.1080/15374416.2013.822307 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kemp, M., Drummond, P., & McDermott, B. (2010). A wait-list controlled pilot study of eye movement desensitization and reprocessing (EMDR) for children with posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD) symptoms from motor vehicle accidents. Clinical Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 15(1), 5–25. doi: 10.1177/1359104509339086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- King, N., Tonge, B., Mullen, P., Myerson, N., Heyne, D., Rollings, S., & Ollendick, T. (2000). Treating sexually abused children with posttraumatic stress symptoms: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 39(11), 1347–1355. doi: 10.1097/00004583-200011000-00008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lancaster, C., Gros, D., Mullarkey, M., Badour, C., Killeen, T., Brady, K., & Back, S. (2020). Does trauma-focused exposure therapy exacerbate symptoms among patients with comorbid PTSD and substance use disorders? Behavioural and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 48(1), 38–53. doi: 10.1017/S1352465819000304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Landis, J. R., & Koch, G. G. (1977). The measurement of observer agreement for categorical data. Biometrics, 33(1), 159–174. doi: 10.2307/2529310 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Larsen, S. E., Wiltsey Stirman, S., Smith, B. N., & Resick, P. A. (2016). Symptom exacerbations in trauma-focused treatments: Associations with treatment outcome and non-completion. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 77, 68–77. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2015.12.009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewis, C., Roberts, N. P., Gibson, S., & Bisson, J. J. (2020). Dropout from psychological therapies for post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) in adults: Systematic review and meta-analysis. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 11(1). doi: 10.1080/20008198.2019.1709709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marsac, M. L., Donlon, K., & Berkowitz, S. (2014). Indicated and selective preventive interventions. Child and Adolescent Psychiatric Clinics of North America, 23(2), 383–397. doi: 10.1016/j.chc.2013.12.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mavranezouli, I., Megnin, V. O., Daly, C., Dias, S., Stockton, S., Meiser, S. R., … Pilling, S. (2020). Research Review: Psychological and psychosocial treatments for children and young people with post‐traumatic stress disorder: A network meta‐analysis. Journal of Child Psychology & Psychiatry, 61(1), 18–29. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.13094 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McMullen, J., O'Callaghan, P., Shannon, C., Black, A., & Eakin, J. (2013). Group trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy with former child soldiers and other war-affected boys in the DR Congo: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 54(11), 1231–1241. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12094. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meiser-Stedman. R., Smith, P., McKinnon, A., Dixon, C., Trickey, D., Ehlers, A., Clark, D. M., Boyle, A., Watson, P., Goodyer, I. & Dalgleish, T. (2017). Cognitive therapy as an early treatment for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents: A randomized controlled trial addressing preliminary efficacy and mechanisms of action. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 58(5), 623–633. doi: 10.1111/jcpp.12673 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morina, N., Koerssen, R., & Pollet, T. V. (2016). Interventions for children and adolescents with posttraumatic stress disorder: A meta-analysis of comparative outcome studies. Clinical Psychology Review, 47, 41–54. doi: 10.1016/j.cpr.2016.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R. A., Sink, H. E., Ake, G. S., III, Carmody, K. A., Amaya-Jackson, L. M., & Briggs, E. C. (2014). Predictors of treatment completion in a sample of youth who have experienced physical or sexual trauma. Journal of Interpersonal Violence, 29(1), 3–19. doi: 10.1177/0886260513504495 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murray, L. K., Skavenski, S., Kane, J. C., Mayeya, J., Dorsey, S., Cohen, J. A., Michalopoulos, L. T. M., Imasiku, M., & Bolton, P. A. (2015). Effectiveness of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy among trauma-affected children in Lusaka, Zambia: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association Pediatrics, 169(8), 761–769. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2015.0580 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . (2018). NICE Guideline [NG116]. In Post-traumatic stress disorder. London: NICE. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nixon, R. D., Sterk, J., & Pearce, A. (2012). A randomized trial of cognitive behaviour therapy and cognitive therapy for children with Posttraumatic Stress Disorder following single-incident trauma. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 40(3), 327–337. doi: 10.1007/s10802-011-9566-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan, P., McMullen, J., Shannon, C., & Rafferty, H. (2015). Comparing a trauma focused and non trauma focused intervention with war affected Congolese youth: A preliminary randomized trial. Intervention, 13, 28–44. [Google Scholar]

- O'Callaghan, P., McMullen, J., Shannon, C., Rafferty, H., & Black, A. (2013). A randomized controlled trial of trauma-focused cognitive behavioral therapy for sexually exploited, war-affected Congolese girls. Journal of the American Academy of Child and Adolescent Psychiatry, 52(4), 359–369. doi: 10.1016/j.jaac.2013.01.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olatunji, B. O. (2009). The cruellest cure? Ethical issues in the implementation of exposure-based treatments. Cognitive and Behavioral Practice, 16(2), 239. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpra.2008.07.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Page, M. J., Higgins, J. P. T., & Sterne, J. A. C. (2020). Chapter 13: Assessing risk of bias due to missing results in a synthesis. In Higgins J. P. T., Thomas J., Chandler J., Cumpston M., Li T., Page M. J., & Welch V. A. (Eds.), Cochrane handbook for systematic reviews of interventions version 6.1 (updated September 2020). Cochrane. Retrieved from www.training.cochrane.org/handbook [Google Scholar]

- Peltonen, K., & Kangaslampi, S. (2019). Treating children and adolescents with multiple traumas: A randomized clinical trial of narrative exposure therapy. European Journal of Psychotraumatology, 10(1), e1558780. doi: 10.1080/20008198.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Pityaratstian, N., Piyasil, V., Ketumarn, P., Sitdhiraksa, N., Ularntinon, S., & Pariwatcharakul, P. (2015). Randomized controlled trial of group cognitive behavioral therapy for post-traumatic stress disorder in children and adolescents exposed to tsunami in Thailand. Behavioral and Cognitive Psychotherapy, 43(5), 549–561. doi: 10.1017/S1352465813001197 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Robjant, K., Koebach, A., Schmitt, S., Chibashimba, A., Carleial, S., & Elbert, T. (2019). The treatment of posttraumatic stress symptoms and aggression in female former child soldiers using adapted Narrative Exposure therapy – A RCT in Eastern Democratic Republic of Congo. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 123. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2019.103482 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosner, R., Rimane, E., Frick, U., Gutermann, J., Hagl, M., Renneberg, B., Schreiber, F., Vogel, A., & Steil, R. (2019). Effect of developmentally adapted cognitive processing therapy for youth with symptoms of posttraumatic stress disorder after childhood sexual and physical abuse: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of the American Medical Association Psychiatry, 76(5), 484–491. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2018.4349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruf, M., Schauer, M., Neuner, F., Catani, C., Schauer, E., & Elbert, T. (2010). Narrative exposure therapy for 7- to 16-year-olds: A randomized controlled trial with traumatized refugee children. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 23(4), 437–445. doi: 10.1002/jts.20548 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzek, J. I., Eftekhari, A., Crowley, J., Kuhn, E., & Karlin, B. E. (2017). Post-training beliefs, intentions, and use of Prolonged Exposure Therapy by clinicians in the Veterans Health Administration. Administration and Policy in Mental Health, 44(1), 123–132. doi: 10.1007/s10488-015-0689-y [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruzek, J. I., Eftekhari, A., Rosen, C. S., Crowley, J. J., Kuhn, E., Foa, E. B., … Karlin, B. E. (2014). Factors related to clinician attitudes toward prolonged exposure therapy for PTSD. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 27(4), 423–429. doi: 10.1002/jts.21945 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salloum, A., & Overstreet, S. (2012). Grief and trauma intervention for children after disaster: Exploring coping skills versus trauma narration. Behaviour Research and Therapy, 50(3), 169–179. doi: 10.1016/j.brat.2021.01.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santiago, C. D., Lennon, J. M., Fuller, A. K., Brewer, S. K. & Kataoka, S. H. (2014). Examining the impact of a family treatment component for CBITS: When and for whom is it helpful? Journal of Family Psychology, 28(4), 560–570. doi: 10.1037/a0037329 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Scheeringa, M. S., Weems, C. F., Cohen, J. A., Amaya-Jackson, L., & Guthrie, D. (2011). Trauma-focused cognitive-behavioral therapy for posttraumatic stress disorder in three-through six year-old children: A randomized clinical trial. Journal of Child Psychology and Psychiatry, 52(8), 853–860. doi: 10.1111/j.1469-7610.2010.02354.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnurr, P. P. (2007). The rocks and hard places in psychotherapy outcome research. Journal of Traumatic Stress, 20(5), 779–792. doi: 10.1002/jts.20292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]