Abstract

Corticotrophinomas represent 10% of all surgically removed pituitary adenomas, however, current treatment options are often not effective, and there is a need for improved pharmacological treatments. Recently, JQ1+, a bromodomain inhibitor that promotes gene transcription by binding acetylated histone residues and recruiting transcriptional machinery, has been shown to reduce proliferation in a murine corticotroph cell line, AtT20. RNA-Seq analysis of AtT20 cells following treatment with JQ1+ identified the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) gene as significantly downregulated, which was subsequently confirmed using real-time PCR and Western blot analysis. CaSR is a G protein-coupled receptor that plays a central role in calcium homeostasis but can elicit non-calcitropic effects in multiple tissues, including the anterior pituitary where it helps regulate hormone secretion. However, in AtT20 cells, CaSR activates a tumour-specific cAMP pathway that promotes ACTH and PTHrP hypersecretion. We hypothesised that the Casr promoter may harbour binding sites for BET proteins, and using chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP)-sequencing demonstrated that the BET protein Brd3 binds to the promoter of the Casr gene. Assessment of CaSR signalling showed that JQ1+ significantly reduced Ca2+e-mediated increases in intracellular calcium (Ca2+i) mobilisation and cAMP signalling. However, the CaSR-negative allosteric modulator, NPS-2143, was unable to reduce AtT20 cell proliferation, indicating that reducing CaSR expression rather than activity is likely required to reduce pituitary cell proliferation. Thus, these studies demonstrate that reducing CaSR expression may be a viable option in the treatment of pituitary tumours. Moreover, current strategies to reduce CaSR activity, rather than protein expression for cancer treatments, may be ineffective.

Keywords: corticotrophinoma, epigenetic modification, G protein-coupled receptor, pituitary tumourigenesis

Introduction

Pituitary tumours are common neoplasms, which account for 10–15% of primary intracranial tumours and are identified in > 25% of unselected autopsies and approximately 20% of the population undergoing intracranial imaging (Daly et al. 2009, Di Ieva et al. 2014). Corticotrophinomas, which secrete adrenocorticotropic hormone (ACTH), represent 10% of all surgically removed pituitary adenomas (Daly et al. 2009). The recommended treatment for corticotrophinomas is trans-sphenoidal resection, which can result in remission rates of up to 90% for microadenomas (Cuevas-Ramos et al. 2016). Trans-sphenoidal resection can, however, result in mortality rates of 1–2%, with 10-year recurrence rates of ~20% (Daly et al. 2009, Cuevas-Ramos et al. 2016). Pharmacological treatments, including inhibitors of steroidogenesis, glucocorticoid antagonists, dopamine agonists, and somatostatin analogues, may provide an alternative for patients in whom surgery is contraindicated or has been unsuccessful (Cuevas-Ramos et al. 2016). However, these current medical treatments are often not effective in corticotrophinomas, and, therefore, there is a clinically unmet need for improved pharmacological treatments for these patients.

Increasing evidence indicates that aberrant epigenetic modifications play an important role in pituitary tumourigenesis (Shariq & Lines 2019), and previously we have demonstrated that the bromo and extra terminal domain (BET) protein inhibitor, JQ1+, reduces proliferation and increases apoptosis of the corticotroph murine cell line, AtT20 (Lines et al. 2020), indicating it may also represent an effective novel therapy for corticotrophinomas. The mechanism by which JQ1+ alters proliferation and apoptosis in these cells is, however, incompletely understood. To elucidate the target pathways of JQ1+ in pituitary cells, we previously undertook RNA sequence analysis (Lines et al. 2020). This revealed that one of the most highly significantly downregulated genes was the calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) (Supplementary Table 1, see section on supplementary materials given at the end of this article).

The CaSR is a G protein-coupled receptor (GPCR) that is widely expressed and has calcitropic roles, that is, regulation of extracellular calcium (Ca2+e) by the parathyroid, kidneys and bone, and non-calcitropic roles such as inflammation, bronchoconstriction, wound healing, gastropancreatic hormone secretion, hypertension, and glucose metabolism (Hofer et al. 2000, Rossol et al. 2012, Yarova et al. 2015, Zietek & Daniel 2015). On stimulation by elevations in Ca2+e, the CaSR can couple to multiple G-protein subtypes to activate diverse signalling pathways. In most cell types, CaSR couples predominantly to Gq/11, to activate phospholipase C (PLC)-mediated increases in intracellular calcium and mitogen-activated protein kinase (MAPK), and Gi/o, to reduce cAMP (Brown & MacLeod 2001, Hofer & Brown 2003). However, in some cell types, CaSR is able to couple to G12/13 to activate Rho kinase signalling (Huang et al. 2004), and in breast cancer and AtT20 cells, CaSR activates Gs-mediated increases in cAMP (Mamillapalli et al. 2008, Mamillapalli & Wysolmerski 2010). The switching of CaSR coupling from Gq/11 and Gi/o to Gs has been suggested to contribute to tumourigenesis as it is only present in malignant breast cancer cells and not in normal mammary epithelial cells (Mamillapalli et al. 2008). This switch to Gs coupling increases cAMP, which consequently increases secretion of parathyroid hormone-related peptide (PTHrP) (Mamillapalli et al. 2008), a growth factor that is required for mammary gland development (Hens et al. 2007) but has been implicated in malignancy in several tissue types including breast, colon and prostate (Suva et al. 1987, Asadi et al. 1996, Shen et al. 2007). Targeting this pathway by inhibiting CaSR signalling via treatment with the CaSR negative allosteric modulator NPS-2143, and mammary gland-specific deletion of the Casr gene, reduced tumour cell proliferation and PTHrP secretion (Kim et al. 2016).

A CaSR-mediated increase in cAMP signalling and PTHrP secretion via the Gs pathway has also been demonstrated in AtT20 cells (Mamillapalli & Wysolmerski 2010). Reduction of CaSR expression by siRNA has been shown to reduce CaSR signalling in AtT20 cells, although the effect on proliferation was not assessed (Mamillapalli & Wysolmerski 2010). Recently, JQ1+ treatment of AtT20 cells was shown to reduce proliferation and increase apoptosis, indicating that this may be an efficacious treatment for corticotrophinomas (Lines et al. 2020). RNA-Seq analysis in these JQ1+-treated cells revealed that the Casr gene was significantly downregulated (Lines et al. 2020) (Supplementary Table 1). We, therefore, hypothesised that reducing CaSR expression or signalling by the receptor may be a novel treatment for pituitary tumours. Moreover, if existing allosteric modulators of CaSR could reduce AtT20 proliferation, these compounds could be repurposed for use in pituitary tumours.

Materials and methods

Cell lines, antibodies and compounds

AtT20 murine pituitary corticotroph tumour cells (ATCC) were cultured in DMEM media (Gibco, supplemented with 10% foetal calf serum (FCS) (Gibco). HEK293 cells stably expressing CaSR (HEK-CaSR) (Nesbit et al. 2013) were cultured in DMEM Glutamax media (Gibco), supplemented with 10% FCS and 400 µg/mL geneticin (ThermoFisher Scientific). All cells were maintained at 37°C, 5% (vol/vol) CO2, and tested for mycoplasma using the MycoAlert kit (Lonza, Basel, Switzerland). Cells were maintained for a maximum of 15 passages, and all assays were performed after at least one passage following cell rederivation. Cells were transiently transfected with Lipofectamine 2000 (LifeTechnologies). The active (+)-JQ1 (JQ1+, IUPAC [(S)-4-(4-chloro-phenyl)-2,3,9-trimethyl-6H-1-thia-5,7,8,9a-tetraaza-cyclopenta[e]azulen-6-yl]-acetic acid tert-butyl ester) and inactive control compound (−)-JQ1 (JQ1−) were supplied by the Structural Genomics Consortium, Oxford, and further details on the structure and specificity for each compound are available at https://www.thesgc.org/chemical-probes. Most compounds were suspended/diluted in DMSO (Sigma-Aldrich), except pertussis toxin (Sigma), which was suspended in ethanol. JQ1+ was used at a concentration of 1 µM, which has previously been shown to reduce AtT20 cell proliferation (Lines et al. 2020). The negative allosteric modulator NPS-2143 hydrochloride (also known as 2-chloro-6-[(2R)-3-[[1,1-dimethyl-2-(2-naphthalenyl)ethyl]amino]-2-hydroxypropoxy]-benzonitrile hydrochloride) was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (catalogue SML0362). H-89 dihydrochloride (H89) was purchased from Sigma-Aldrich. Untreated and DMSO or ethanol only-treated cells were used as controls.

Quantitative real time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was extracted from AtT20 cell lines using a miRvana kit (Ambion), and 1 μg was used to generate cDNA using the Quantitect RT kit (Qiagen), as previously described (Lines et al. 2017). Quantitect primers (Qiagen) were used for qRT-PCR reactions, utilising the Quantitect SYBR green kit (Qiagen), on a Rotor-Gene 5. Each test sample was normalised to the geometric mean of reference genes for glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase and α1a-tubulin (Gapdh and Tuba1a, respectively). The relative expression of target cDNA in all qRT-PCR studies was determined using the Pfaffl method (Pfaffl 2001). Data were normalised to untreated cells (set at 1) within each biological replicate, then data were combined for all the biological replicates to perform statistical analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using either a one-way ANOVA or an unpaired student’s t-test.

Western blot analysis

Western blots were performed as previously described (Lines et al. 2017, Gorvin et al. 2018). Cells were seeded at 300,000 cells/well, left to settle for 24 h before treatment with 1 µM JQ1−, JQ1+, or DMSO. Cell lysates were prepared in NP40 lysis buffer: 250 mM NaCl, Tris 50 mM (pH 8.0), 5 mM EDTA, 0.5% NP-40 (vol/vol) and 2× protease inhibitor tablets (Roche). Lysates were prepared in 4× Laemmli loading dye (BioRad Laboratories) boiled at 95°C for 5 min, resolved using 6% SDS-PAGE gel electrophoresis and transferred to polyvinylidene difluoride membrane (PVDF). PVDF membrane was probed with primary antibody anti-CaSR (ADD, Abcam) and secondary antibody anti-mouse HRP conjugate (BioRad). Blots were then stripped with Restore Western Blot Stripping Buffer (ThermoScientific) and re-probed with anti-Calnexin (Millipore) loading control primary antibody and secondary antibody anti-rabbit HRP conjugate (Santa Cruz Biotechnology). Western blots were visualised using an Immuno-Star WesternC kit (BioRad) on a BioRad Chemidoc XRS+ system. Densitometry analysis was performed by calculating the number of pixels per band using ImageJ software. Data were represented as the number of pixels of the protein band, relative to the number of pixels of the corresponding calnexin band. Western blot analyses were performed in four biological replicates (i.e. four independently treated batches of cells, prepared on separate days). To compare datasets, data were normalised to untreated cells (set at 1) within each biological replicate, then data were combined for all the biological replicates to perform statistical analyses. Statistical analysis was performed using an unpaired student’s t-test.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation and sequencing (ChIP-Seq)

Approximately 8 million AtT20 cells were fixed in 1% formalin in culture media before being split into four aliquots and sonicated to produce DNA fragments between 200 and 1000 bp. Chromatin Immunoprecipitation (ChIP) was undertaken using the ChIP assay kit (Merck Millipore) with samples incubated overnight with 10 µL anti-Brd2 (D89B4, Cell Signalling), 10 µL anti-Brd3 (61489, Active motif, La Hulpe, Belgium), and 0.5 µg anti-Brd4 (PA5-41550, Thermo Fisher Scientific) antibodies. DNA from each ChIP was un-cross-linked, purified using phenol extraction, precipitated using ethanol and resuspended in nuclease-free water. For all experiments, an input (no antibody) control was also included for analysis. ChIPs were sequenced using a NovaSeq 6000 at the Oxford Genomics Centre (Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics, University of Oxford). All experiments were performed in n = 3 biological replicates. For analysis, adapter filtering, read mapping and filtering, lane merging, de-duplication, peak calling and refining were undertaken, as well as normalized strand coefficient (NSC), relative strand correlation (RSC), irreproducible discovery rate (IDR), read enrichment around transcription start site (TSS) quality checks. BigWig files were generated using the ‘bamCoverage’ function from deepTools2 software (Ramirez et al. 2016). The reads per genomic content (RPGC) (1× normalisation) approach was used for the coverage normalisation with parameters applied as follows: bin Size 10 – normalise using RPGC – effective GenomeSize 2620345972 – extend reads – ignore duplicates. Data were then uploaded and visualised using a UCSC genome browser custom track.

Intracellular calcium measurements

Ca2+e-induced Ca2+i responses were measured by Fluo-4 calcium assays, as previously described (Gorvin et al. 2018). Cells were plated at 30,000 cells/well in black-walled 96-well plates (Corning). Cells were incubated with serum-free media (SFM) overnight with either vehicle (DMSO), JQ1− or JQ1+ (Fluo-4 dye was prepared according to manufacturer’s instructions (Invitrogen), and cells were loaded for 1 h at 37°C. Baseline measurements were made and increasing concentrations of CaCl2 were injected automatically into each well. Changes in Ca2+i were recorded on a PHERAstar instrument (BMG Labtech, Aylesbury, UK) at 37°C with an excitation filter of 485 nm and an emission filter of 520 nm. The peak mean fluorescence ratio of the transient response after each individual stimulus was expressed as a normalised response, relative to the basal response. Nonlinear regression of concentration-response curves, area under the curve (AUC) and maximal responses were calculated using GraphPad Prism 7. Each treatment was performed in four to five columns on four separate occasions. Maximal responses were compared using one-way ANOVA and EC50 values compared using the F-test (Gorvin et al. 2018).

Luciferase reporter assays

Cells were plated at 50,000 cells/well in 24-well plates and transiently transfected with 100 ng/mL pGL4-cAMP-response element (CRE) luciferase reporter and 10 ng/mL pRL null control luciferase reporter constructs (Promega). For control experiments, HEK-CaSR cells were pre-treated with 10 μM forskolin (MP Biomedicals, Eschwege, Germany) for 30 min on the day of the assay to activate adenylate cyclase. For studies with epigenetic modifiers, cells were pre-treated with DMSO vehicle control, JQ1+ or JQ1− compounds for 24 h prior to performance of assays, and for allosteric modulator studies cells were exposed to 20 nM NPS-2143 overnight. On the day of the experiment, all cells were treated with SFM containing 0.1–10 mM CaCl2 and incubated for 4 h. Cells were then lysed and assays were performed using Dual-Glo Luciferase (Promega) on a Veritas Luminometer (Promega) as previously described (Gorvin et al. 2018). For studies with pertussis toxin, cells were pre-incubated with ethanol vehicle control or 300 ng/mL pertussis toxin for 6 h prior to CRE measurements. For studies with H89, cells were pre-incubated with DMSO vehicle control or 10 µM H89 for 1 h prior to luciferase measurements. Luciferase: renilla ratios were expressed as fold changes relative to responses at low CaCl2 concentrations (0.1 mM). All assay conditions were performed in four independent transfections. Statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test using GraphPad Prism 7.

Cell viability

Cell viability was assessed using the CellTiter-Blue Cell Viability assay (Promega), as previously described (Lines et al. 2017). Cells were plated at 10,000 cells/well and grown in media containing 1.8 mM CaCl2 (basal level for DMEM-Glutamax media). For each assay, 20 μL of CellTiter-Blue reagent were added per well, incubated for 2 h at 37°C, 5% (vol/vol) CO2, before the output was read on a CytoFluor microplate reader (PerSeptive Biosystems, Paisley, UK) at 530 nm excitation and 580 nm emission. All assay conditions were performed in four to five biological replicates. Statistical analyses were performed by one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism 7.

Statistical analysis

Statistical comparisons in qRT-PCR and Western blot analyses were made using one-way ANOVA or the unpaired student’s t-test. For Ca2+i measurements, maximal responses were compared using one-way ANOVA and EC50 values were compared using the F-test. For luciferase reporter assays, statistical analysis was performed by two-way ANOVA with Tukey’s multiple-comparisons test using GraphPad Prism 7. For cell viability assays, statistical analysis was performed by one-way ANOVA and Student’s t-test using GraphPad Prism 7.

Results

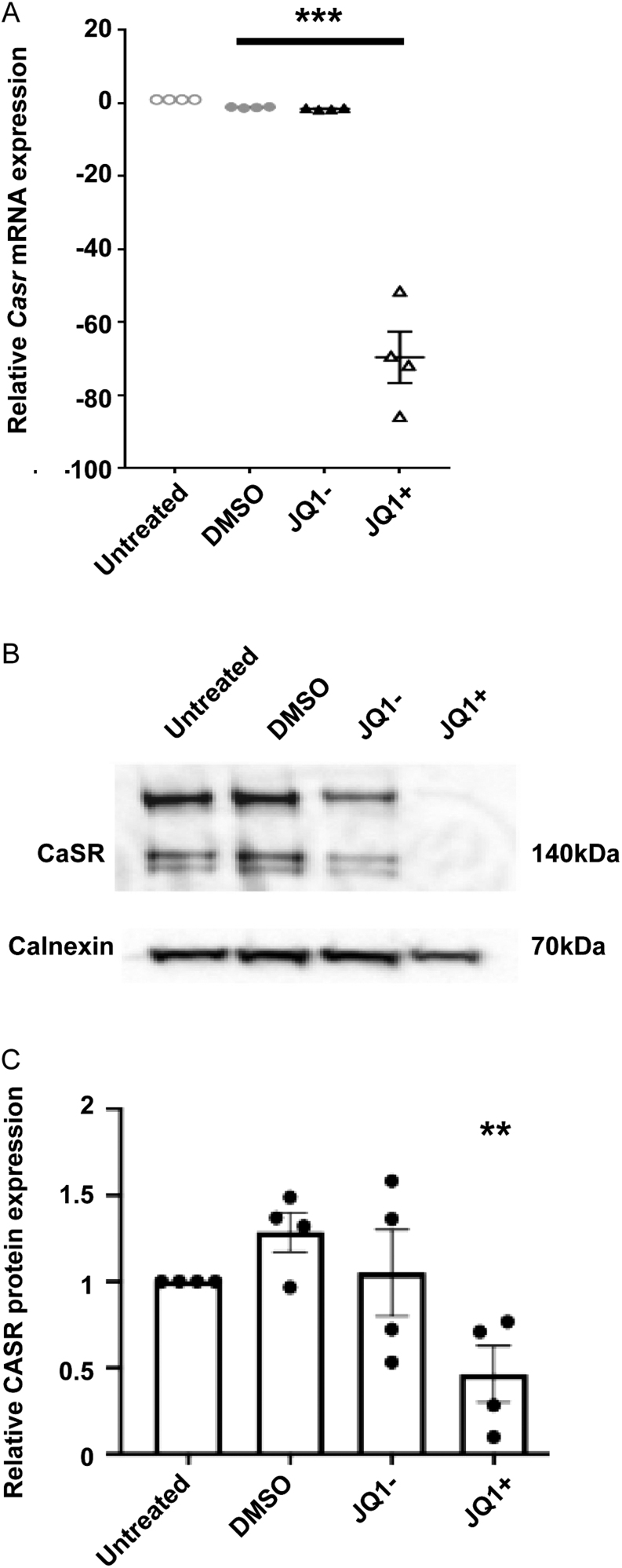

CaSR expression is significantly downregulated by JQ1+ treatment

Our previous studies demonstrated that JQ1+ was effective in reducing proliferation in the corticotrophinoma cell line, AtT20 (Lines et al. 2020). RNA-sequencing showed a number of genes to be differentially expressed in AtT20 cells by JQ1+ treatment, including the gene encoding Casr, which was in the top 15 most downregulated genes (43.30-fold reduction compared to vehicle-treated cells, P < 0.0001) (Supplementary Table 1). Quantitative RT-PCR analysis was used to verify the reduction in Casr gene expression in JQ1+-treated cells. This revealed a significant reduction in JQ1+-treated cells (−69.67 ± 7.07-fold, P < 0.001) compared to untreated cells (Fig. 1A). There was no significant difference between AtT20 cells treated with DMSO or JQ1− when compared to untreated cells (−1.12 ± 0.08 and −1.50 ± 0.12, respectively), indicating the downregulation observed with JQ1+ is specific to the active JQ1+ compound (Fig. 1A). Western blot analysis confirmed that CaSR protein expression was also reduced in JQ1+-treated AtT20 cells (−0.46 ± 0.16), compared to untreated cells (Fig. 1B and C ). There was no significant difference between AtT20 cells treated with DMSO or JQ1− when compared to untreated cells (1.29 ± 0.11 and 1.05 ± 0.25), respectively. Therefore, JQ1+ treatment reduces mRNA and protein expression of CaSR in AtT20 cells.

Figure 1 Calcium-sensing receptor.

(CaSR) is downregulated by JQ1+ treatment. (A) qRT-PCR analysis of CaSR following exposure to cell culture media, DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 96 h in AtT20 cells. (B) Representative Western blot of CaSR in AtT20 cells following exposure to DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 96 h. (C) Densitometry analysis of protein expression following treatment with DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 96 h. CaSR protein expression was expressed relative to calnexin. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. in panels A and C. Statistical analyses compared to DMSO-treated cells in all panels: ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01.

The epigenetic modifier Brd3 binds to DNA regions coding for Casr

JQ1+ is an epigenetic modifier that targets bromodomains (BRDs) of the BET protein family, which in turn bind acetylated histone residues (Filippakopoulos et al. 2010). The BET family comprises four members, BRD2, BRD3, BRD4, which are ubiquitously expressed, and BRDT, a testes-specific protein (Filippakopoulos et al. 2010). Our previous studies have shown that Brd2, Brd3 and Brd4 are expressed at high levels in the AtT20 cells (Lines et al. 2020), and JQ1+ may target any of these proteins. We, therefore, performed ChIP-Seq analysis, which can be used to identify the binding sites of DNA-associated proteins (Park 2009), using antibodies targeting each of the three Brd proteins in AtT20 cell lines. This revealed that ChIP with Brd3 antibody resulted in significant enrichment (P < 0.001), compared to input control, of DNA in the genetic region coding for the Casr (Supplementary Fig. 1). In total, two peaks were observed, the first at an average position of 16:3,653,074–36,532,125, and the second at 16:3,655,597–36,556,077, both of which correspond to regions within intron 1–2 of the mouse Casr gene ENSMUG00000051980. This significant enrichment was not observed for the ChIPs with Brd2 or Brd4 antibodies (Supplementary Fig. 1), thereby indicating that Brd3 likely binds to genetic regions coding for the Casr, while Brd2 and Brd4 do not bind or bind to a lesser extent.

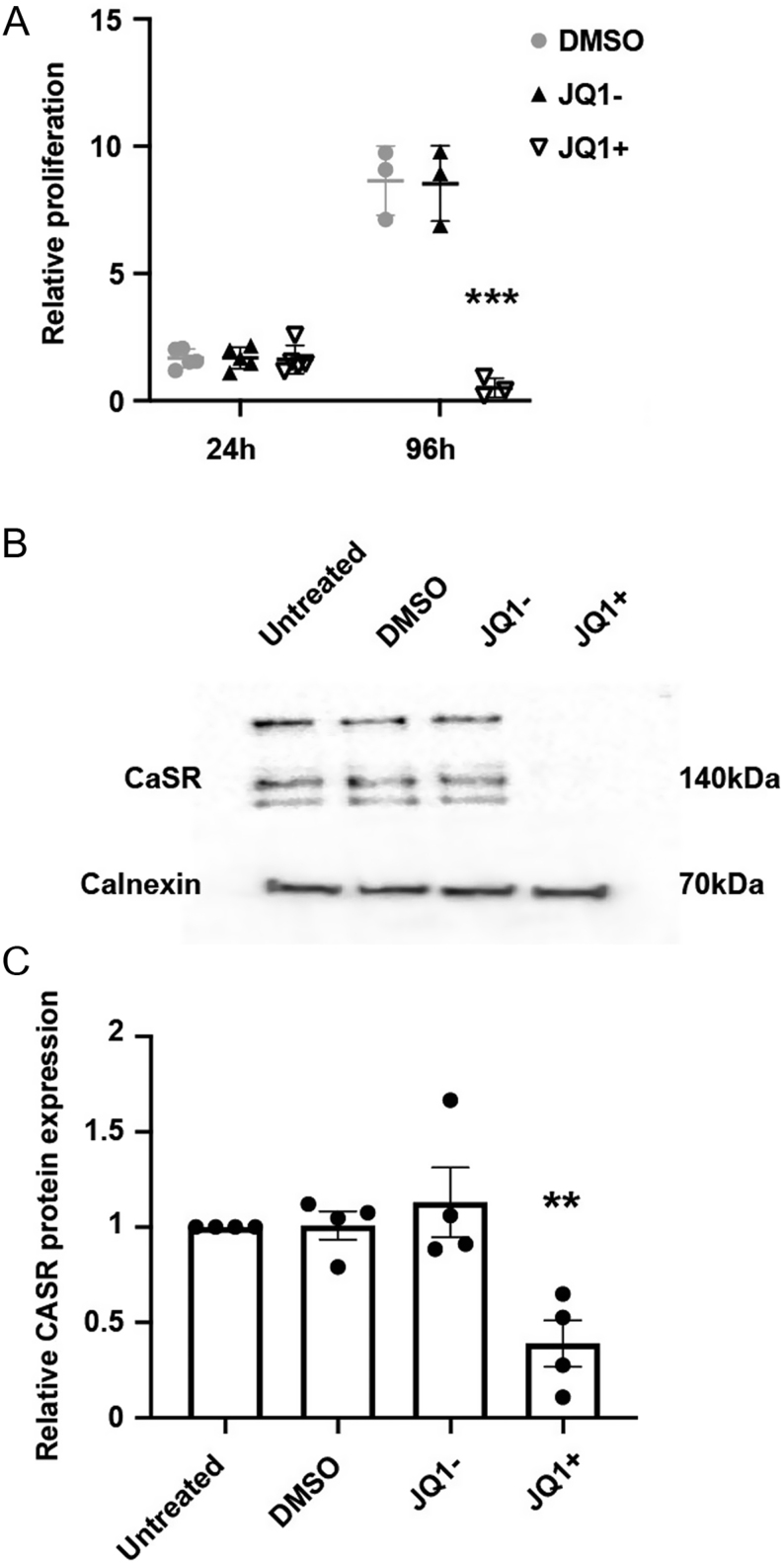

JQ1+ inhibits Gs-mediated cAMP increases

As JQ1+ reduced CaSR expression in AtT20 cells, we hypothesised that CaSR signalling would also be reduced. However, previous studies have shown that JQ1+ reduces the number of viable AtT20 cells after 96-h treatment, which is at least in part due to increased apoptosis (Lines et al. 2020). Therefore, any reduction in signalling could be due to a JQ1+-mediated impairment of signalling or merely a reduction in cell number. Thus, prior to embarking on signalling studies, we first sought to establish a time point at which JQ1+ would not reduce proliferation but may still impact CaSR function. To assess the number of viable cells following treatment with DMSO, JQ1+ and JQ1−, Cell Titer Blue assays were performed 24 and 96 h post-treatment (Fig. 2A). This revealed a modest increase in cell numbers in all treatment groups after 24 h, with no significant difference between JQ1+ and the other treatment groups (Fig. 2A). In contrast, at 96 h, cells treated with DMSO and JQ1− exhibited a 5.2-fold and 5.1-fold increase in cell number, respectively, while JQ1+ cells reduced cell viability by 17-fold (P < 0.005, Fig. 2A). This confirmed previous findings that JQ1+ reduced viability in AtT20 cells at 96 h and revealed that the compound did not significantly reduce cell numbers at 24 h. Moreover, JQ1+ treatment significantly reduced CaSR protein expression at 24 h, by 61.2% (P < 0.005, Fig. 2B and C ). There was no significant difference between CaSR expression in cells treated with DMSO or the inactive JQ1− compound when compared to untreated cells. Thus, we concluded that 24 h post-JQ1+ treatment would be the optimal time to perform signalling assays.

Figure 2.

JQ1+ does not reduce proliferation of AtT20 cells after 24 h but does decrease calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR) protein expression. (A) Relative proliferation of AtT20 cells following exposure to DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 24 and 96 h. Data were expressed relative to cell numbers at day 0. (B) Representative Western blot of CaSR in AtT20 cells following exposure to DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 24 h. (C) Densitometry analysis of protein expression following treatment with DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 24 h. CaSR protein expression was expressed relative to calnexin. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. in panels A and C. Statistical analyses compared to DMSO treatment in panel A, ***P < 0.001, and statistical analysis compared to DMSO-treated cells in panel C, **P < 0.005.

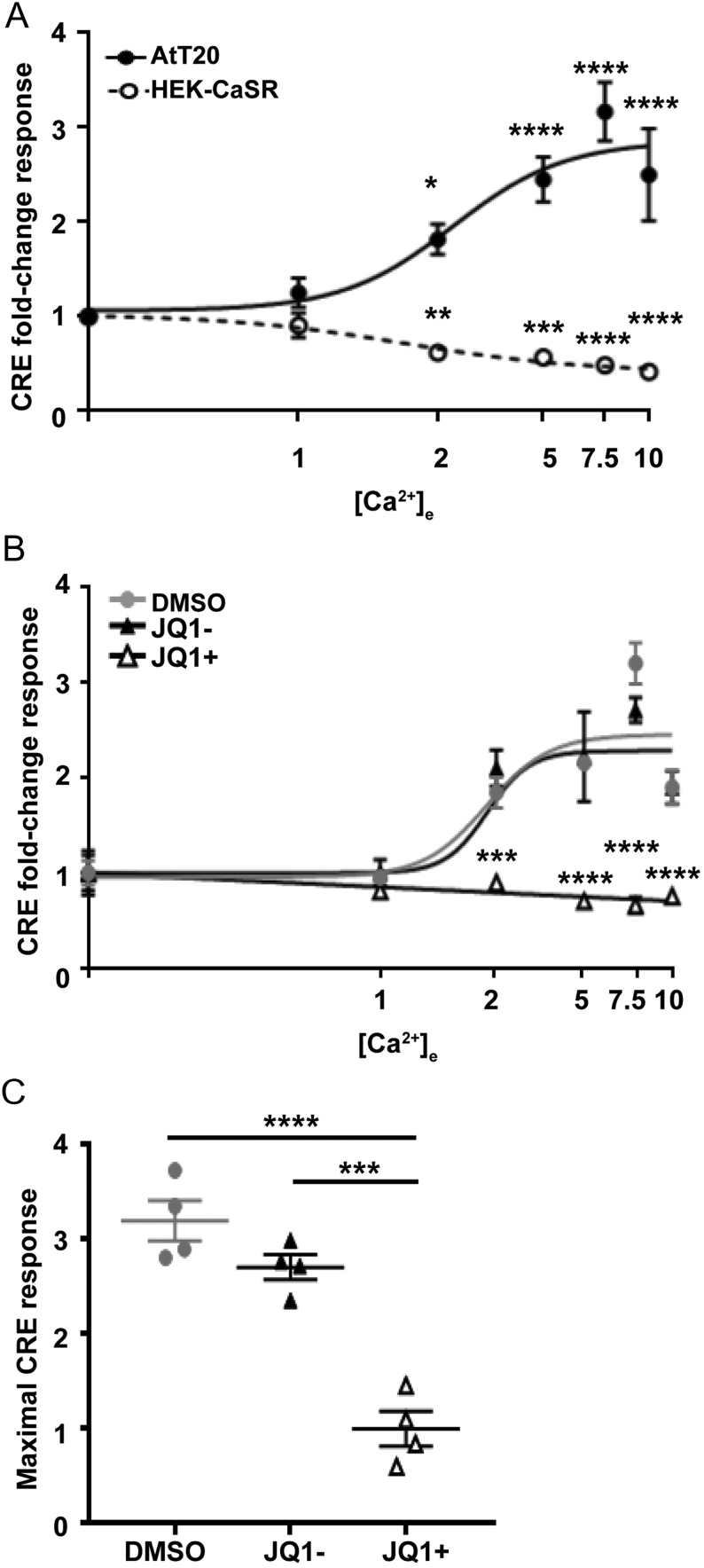

Previous studies of CaSR in cancer cell lines, including MCF-7 human breast cancer cells and AtT20 cells, have shown that CaSR switches from preferentially coupling to Gq/11 and Gi/o pathways to exclusively signalling by a Gs pathway (Mamillapalli et al. 2008, Mamillapalli & Wysolmerski 2010). Activation of the Gs signalling pathway leads to a signalling cascade involving activation of adenylate cyclase, increases in cAMP, activation of protein kinase A, and increases in transcription (Walsh & Van Patten 1994). We used a CRE luciferase reporter (Gorvin et al. 2018) to assess cAMP signalling. Although CRE can be induced by other signalling pathways (e.g. Ca2+i and MAPK), CaSR-mediated effects on CRE luciferase are impaired by pertussis toxin (which inhibits adenylate cyclase) and H89 (which impairs protein kinase A) in HEK-CaSR cells, indicating that CaSR-mediated CRE luciferase activity is at least partially cAMP-dependent (Supplementary Fig. 2). We thus utilised this reporter in the AtT20 cells to first confirm that Ca2+e preferentially activates CRE luciferase activity (Fig. 3). AtT20 cells were exposed to increasing concentrations of Ca2+e (0.1–10 mM), and CRE reporter activity was measured. This revealed a concentration-dependent increase in CRE reporter activity, with a maximal stimulatory fold-change response (Emax) of 3.35 ± 0.29, which was significantly elevated compared to cells exposed to 0.1 mM Ca2+e (P < 0.0001) (Fig. 3A). The same concentration-response assay was also performed in HEK-CaSR cells. This showed a significant reduction in luciferase reporter activity in a concentration-dependent manner, as previously reported (Gorvin et al. 2018) (maximal inhibitory response of 0.68 ± 0.06, P < 0.0001 compared to 0.1 mM Ca2+e). This reduction in signalling is most likely due to Gi/o-coupled effects on cAMP rather than pERK or MAPK as these latter two pathways are increased by CaSR rather than reduced (Fig. 3A). Thus, these studies confirm that AtT20 cells preferentially couple to Gs pathways, while HEK-CaSR cells couple to Gi/o pathways.

Figure 3.

JQ1+ reduces cAMP signalling in AtT20 cell lines. (A) Ca2+e-induced cAMP-response element (CRE) luciferase reporter responses in AtT20 and HEK-CaSR cell lines. Elevations in Ca2+e concentrations increase CRE luciferase in AtT20 cells and reduce luciferase in HEK-CaSR cells. (B) Ca2+e-induced CRE luciferase reporter responses in AtT20 cell lines following exposure to DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 24 h. (C) Maximal CRE luciferase responses from panel B. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. in all panels. Statistical analyses compared to basal responses in each cell line in panel A and to DMSO-treated cells in panel B. Firefly values ranged from 6027 to 981,659 luminescent units and renilla from 1027 to 5031 luminescent units. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

To determine whether JQ1+ affected CaSR-mediated cAMP responses, we repeated the CRE luciferase reporter assays following overnight treatment with DMSO control, JQ1+ or JQ1− (Fig. 3B, C and D ). JQ1+ abolished the Ca2+e-induced increase in CRE reporter activity, while vehicle and JQ1− cells exhibited a concentration-dependent increase in CRE reporter activity (Fig. 3C). Thus, the maximal responses in DMSO and JQ1−-treated cells were 3.20 ± 0.21-fold and 2.71 ± 0.13-fold, respectively, whereas in JQ1+-treated cells, the maximal response was 1.00 ± 0.18-fold, observed in cells treated with basal calcium (0.1 mM) (Fig. 3C). Therefore, JQ1+ is effective in reducing CaSR Gs-mediated signalling in AtT20 cells.

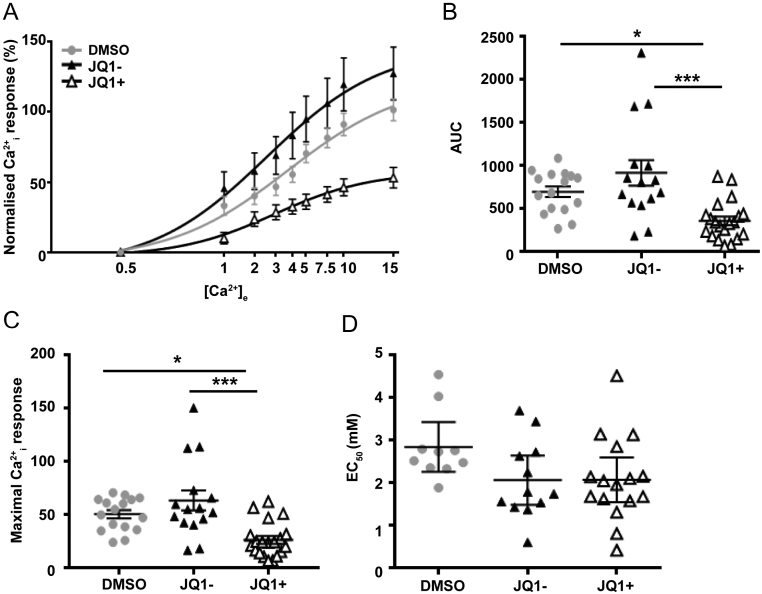

JQ1+ inhibits calcium mobilisation in AtT20 cells

Previous studies of AtT20 cells have demonstrated that CaSR can also activate Ca2+i signalling pathways (Emanuel et al. 1996). The effects of DMSO, JQ1+ and JQ1− on Ca2+e-induced Ca2+i responses in AtT20 cells were assessed using the Fluo-4 calcium assay. The Ca2+i responses were shown to be elevated in a dose-dependent manner following stimulation with increasing concentrations of Ca2+e (Fig. 4A). The responses of the AtT20 cells treated with DMSO or JQ1− were similar at all concentrations of calcium, and the maximal responses were not significantly different (101.4 ± 7.73 and 127.3 ± 18.84, respectively) (Fig. 4A, B and C ). In contrast, the JQ1+-treated cells had reduced responses compared to both DMSO and JQ1−-treated cells (Emax = 53.15 ± 7.27) (Fig. 4A, B and C ). Despite the reduction in Ca2+i maximal responses, there was no significant difference between the EC50 values of the three treatment groups (Fig. 4D). This indicates that the potency of AtT20 for Ca2+e is unchanged, while the efficacy is reduced, most likely due to the reduced CaSR protein expression.

Figure 4.

JQ1+ reduces calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR)-mediated calcium mobilisation in AtT20 cell lines. (A) Ca2+ e-induced Fluo-4 intracellular calcium mobilisation assays in AtT20 cells following exposure to DMSO, JQ1− and JQ1+ for 24 h. (B) Area under the curve (AUC) of data in A. (C) Maximal Ca2+i responses and (D) EC50 values obtained in Fluo-4 intracellular calcium mobilisation assays shown in panel A. Data are expressed as mean ± s.e.m. in panels A and B, and mean ± 95% CIs in panel C. Statistical analyses compared between groups in panel B, ***P < 0.001, *P < 0.05.

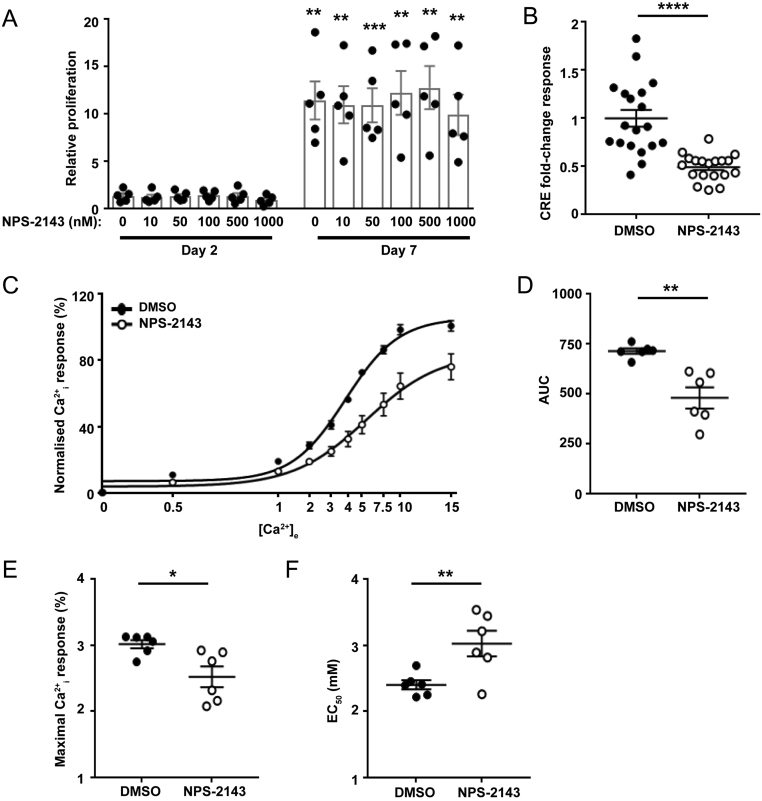

Treatment with a CaSR negative allosteric modulator reduces CaSR signalling but does not affect proliferation in AtT20 cells

These studies led us to hypothesise that JQ1+ most likely mediates its effects by a reduction in CaSR protein rather than mediating direct effects on signalling pathways. To test whether reducing CaSR signalling led to changes in proliferation, we assessed the effect of the CaSR-negative allosteric modulator NPS-2143 on AtT20 cell viability over 7 days. Cells were exposed to six different concentrations of NPS-2143 (0, 10, 50, 100, 500 and 1000 nM) and compared to untreated cells (Fig. 5). As exposure of cells to high concentrations of calcium over a period of days is likely to have a detrimental effect on cells, we maintained cells in standard DMEM media, which contains 1.8 mM CaCl2. Proliferation increased in all cells over 7 days, however, NPS-2143 did not have a significant effect on cell number at any concentration tested (Fig. 5A). In contrast, 50 nM NPS-2143 still reduced CaSR signalling in AtT20 cells, demonstrated by a reduction in CRE luciferase reporter activity (Fig. 5B). NPS-2143 also reduced Ca2+e-mediated Ca2+i signalling demonstrated by a rightward shift in the concentration-response curve when compared to DMSO-treated cells and reduced AUC (Fig. 5B, C and D ) and a reduced maximal response (Emax = 100.63 ± 3.13 in vehicle compared to 75.99 ± 7.76 in NPS-2143-treated cells) and an increased mean EC50 value of 3.12 mM (95% (CI) 2.79–3.49) in NPS-2143-treated cells compared to 2.38 mM (95% CI 2.23–2.53) in DMSO-treated cells (Fig. 5E and F ). Thus, reducing CaSR signalling alone is not sufficient to decrease proliferation in AtT20 cells.

Figure 5.

NPS-2143 has no effect on AtT20 proliferation but does reduce calcium-sensing receptor (CaSR)-mediated cAMP and Ca2+i signalling in AtT20 cells. (A) Effect of NPS-2143 (0–1000 nM) on proliferation of AtT20 cells 2 days and 7 days post-treatment. Data were expressed relative to proliferation at day 1. Statistical analyses comparing proliferation between day 2 and day 7 in each group. There was no significant difference between cell proliferation in cells exposed to different concentrations of NPS-2143. Raw fluorescence units ranged between 17,096 and 69,941 for day 2 and 19,935 and 222,377 for day 7. (B) cAMP-response element (CRE) luciferase reporter responses at 5 mM Ca2+e in AtT20 cells exposed to DMSO or 20 nM NPS-2143 for 12 h. Data were expressed relative to responses in DMSO-treated cells. (C) Ca2+e-induced Fluo-4 intracellular calcium mobilisation assays in AtT20 cells following exposure to DMSO or 20 nM NPS-2143. Raw fluorescence units ranged between 1896 and 58,337. (D) Area under the curve (AUC) of data in C, (E) Maximal Ca2+i responses, and (F) EC50 values showing mean ± 95% CIs obtained in Fluo-4 intracellular calcium mobilisation assays shown in panel C. ****P < 0.0001, ***P < 0.001, **P < 0.01, *P < 0.05.

Discussion

Our studies showed that JQ1+ treatment of corticotroph pituitary cells impairs CaSR mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 1), which may contribute to the reduced cell proliferation observed in earlier studies (Lines et al. 2020). This indicates that targeting CaSR expression could be beneficial in reducing proliferation in neuroendocrine tumours, such as corticotrophinomas that represent up to 10% of all surgically removed pituitary adenomas (Daly et al. 2009), however, this remains to be tested in detail. Moreover, studies of CaSR function in anterior pituitary cells have shown that CaSR activation may enhance pituitary hormone secretions, including ACTH and PTHrP from AtT20 cells (Ferry et al. 1997, Mamillapalli & Wysolmerski 2010); growth hormone (GH) secretion from rat somatotrophs (Zivadinovic et al. 2002); and enhancement of GH-releasing hormone (GHRH)-mediated GH secretion in human non-functioning pituitary adenoma and GH-omas (Romoli et al. 1999). Thus, decreasing CaSR expression may reduce the hypersecretion of ACTH and GH that are observed in 4.8–10% and 13–20% of pituitary adenomas, respectively, and could provide a possible treatment for Cushing’s disease and acromegaly, common co-morbidities of ACTH and GH hypersecretion (Mehta & Lonser 2017, Lines et al. 2020). However, compounds intended to reduce CaSR protein expression would need to be specifically targeted to pituitary cells to prevent adverse effects, such as severe hypercalcaemia that would be observed if CaSR expression was reduced in parathyroid glands and kidneys, in which CaSR performs its primary roles in calcium homeostasis.

The observation that the JQ1+ compound abolished CaSR activity and cell proliferation in AtT20 cells led us to hypothesise that reducing CaSR signalling by treatment with a negative allosteric modulator, NPS-2143, could also reduce cell proliferation and may be a novel treatment for corticotrophinomas. However, while 20 nM NPS-2143 was effective at reducing both Ca2+i and cAMP signalling in AtT20 cells, it had no effect on pituitary cell proliferation in our assays (Fig. 5). Moreover, higher concentrations of NPS-2143 (up to 1000 nM) had no significant effect on AtT20 cell proliferation (Fig. 5). This contrasts with previous studies that have shown NPS-2143 to be efficacious in reducing proliferation in bone metastases associated with renal cell carcinoma (Joeckel et al. 2014), breast cancer cell lines (Kim et al. 2016), gastric cancer cell lines (Zhang et al. 2020), melanoma M14 cancer cells (Wang et al. 2018) and human prostate PC-3 cells (Yamamura et al. 2019). However, these studies used a higher dose of the negative allosteric modulator than our studies, ranging from 5 to 100µM. These concentrations are far in excess of that required to maximally inhibit CaSR activity in HEK293 cells (IC50 = 43 nM) (Gowen et al. 2000) and to stimulate PTH secretion from bovine parathyroid cells in vitro (EC50 = 39 nM) (Nemeth et al. 2001). Indeed, when lower concentrations of NPS-2143 were tested in some of these cancer cell lines, the compound was ineffective in reducing proliferation (Wang et al. 2018, Zhang et al. 2020). The findings from these previous studies indicate that high doses of NPS-2143 that reduce CaSR expression, as well as activity, may be required for NPS-2143 to be effective in reducing the growth of cancer cells. However, this remains to be investigated in detail.

Several lines of evidence indicate that a reduction in CaSR expression, rather than decreasing CaSR activity, is required to reduce cell proliferation. Exposure of cells to high doses of NPS-2143 (10 µM) reduces CaSR protein expression (Huang & Breitwieser 2007, Yamamura et al. 2019), indicating it is likely this, rather than a reduction in CaSR activity, that is responsible for the reduced proliferation observed in multiple cancer cell lines. Treatment of breast cancer cells with siRNAs that target the CaSR reduced receptor expression and decreased cell proliferation (Kim et al. 2016). Finally, our studies using JQ1+ downregulated CaSR mRNA and protein expression (Fig. 1) and reduced AtT20 cell viability. Although JQ1+ was also effective in reducing CaSR signalling (Figs 3 and 4), it is likely that this is due to the reduced CaSR protein expression, which was apparent at 24-h post-treatment with JQ1+. Thus, these studies indicate that the current strategy to reduce CaSR activity in several tumour models may be ineffective unless higher concentrations of compounds are used that can reduce CaSR protein expression.

Previous studies have shown that treatment of AtT20 pituitary cells with JQ1+ alters the expression of other genes that have a role in proliferation, including nuclear factor κ-light-chain enhancer of activated B cells (NFκB) and somatostatin receptor 2 (SSTR2) (Lines et al. 2020). However, the effect of this reduced expression on NFκB and SSTR2 activity was not investigated, and it remains to be determined whether signalling by these proteins is impaired in AtT20 cells. In the present study, we show that Casr is also downregulated by JQ1+ in AtT20 cells, and that this results in reduced CaSR activity. Moreover, the effect of the other genes downregulated in JQ1+-treated AtT20 cells (Supplementary Table 1) remains to be investigated in detail. Downregulation of the keratin 23 (Krt23) gene has been shown to reduce proliferation in colon cancer cells (Birkenkamp-Demtroder et al. 2013), although its function has not been explored in pituitary cells. Other genes, such as LIM homeobox transcription factor 1α (Lmx1a), have been associated with cancer but this appears to act as a tumour suppressor (Liu et al. 2009), and thus the effect of its downregulation by JQ1+ on the growth of AtT20 cells is unknown. Further investigation of these genes could reveal novel targets for the treatment of corticotrophinomas. It is possible that the observed reduction in proliferation and increased apoptosis of AtT20 cells following treatment with JQ1+ is due to the combined effect of changes in multiple proteins, including NFκB, SSTR2 and CaSR. Further studies investigating the effects of BET inhibition on each of these pathways would be required to determine whether all three pathways contribute to the effects of AtT20 cell growth.

Our data indicate that Brd3 was enriched in the genetic region coding for the CaSR, and, therefore, may play a role in the regulation of Casr expression (Supplementary Fig. 1). BRD3 is a BET family member that binds acetylated histones and facilitates transcription by recruitment of other proteins (Filippakopoulos et al. 2010, Fujisawa & Filippakopoulos 2017). The downstream targets of BRD3 in the pituitary, and indeed in cancers in general, are not well described, with BRD3 mostly associated with the regulation of erythroid target genes after binding of GATA1 (Lamonica et al. 2011, Stonestrom et al. 2015). The role of BRD3 in calcium regulation has also not been investigated in detail. However, BRD3 has been reported to be a calcium-sensitive gene that modulates transcriptional machinery in response to calcium signalling during Xenopus renal organ development (Bibonne et al. 2013). It is, therefore, plausible that a feedback loop could be present between calcium signalling and BRD3 expression, which ultimately can downregulate Casr expression.

In conclusion, our studies demonstrate that the BET inhibitor JQ1+ impairs CaSR mRNA and protein expression that may contribute to the reduction in cell proliferation observed in AtT20 corticotroph pituitary cells. Thus, reducing CaSR expression may be a viable option in the treatment of pituitary tumours. Moreover, we have shown that reducing CaSR activity, but not protein expression, is unlikely to have a major effect on pituitary tumourigenesis.

Supplementary Material

Declaration of interest

The authors declare that there is no conflict of interest that could be perceived as prejudicing the impartiality of the research reported.

Funding

This work was supported by an Early Career Grant from the Society for Endocrinology (K E L, C M G); a Wellcome Trust Senior Investigator Award (grant number 106995/Z/15/Z) (R V T) and the Horizon 2020 Programme of the European Union (Project ID: 675228) (R V T).

Author contribution statement

K E L and C M G designed the study. K E L, A K G, S T and C M G performed the experiments and analysed the data. K E L and C M G wrote the manuscript. C B and R V T provided the materials. K E L, A K G, S T, C B, R V T and C M G reviewed and edited the manuscript.

Acknowledgements

The authors thank the Oxford Genomics Centre at the Wellcome Centre for Human Genetics (funded by Wellcome Trust grant reference 203141/Z/16/Z) for the generation and initial processing of sequencing data.

References

- Asadi F, Farraj M, Sharifi R, Malakouti S, Antar S, Kukreja S. 1996. Enhanced expression of parathyroid hormone-related protein in prostate cancer as compared with benign prostatic hyperplasia. Human Pathology 27 1319–1323. ( 10.1016/s0046-8177(9690344-5) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bibonne A, Néant I, Batut J, Leclerc C, Moreau M, Gilbert T. 2013. Three calcium-sensitive genes, fus, brd3 and wdr5, are highly expressed in neural and renal territories during amphibian development. Biochimica et Biophysica Acta 1833 1665–1671. ( 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2012.12.015) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Birkenkamp-Demtroder K, Hahn SA, Mansilla F, Thorsen K, Maghnouj A, Christensen R, Oster B, Orntoft TF. 2013. Keratin23 (KRT23) knockdown decreases proliferation and affects the DNA damage response of colon cancer cells. PLoS ONE 8 e73593. ( 10.1371/journal.pone.0073593) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown EM, MacLeod RJ. 2001. Extracellular calcium sensing and extracellular calcium signaling. Physiological Reviews 81 239–297. ( 10.1152/physrev.2001.81.1.239) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuevas-Ramos D, Lim DST, Fleseriu M. 2016. Update on medical treatment for Cushing’s disease. Clinical Diabetes and Endocrinology 2 16. ( 10.1186/s40842-016-0033-9) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Daly AF, Tichomirowa MA, Beckers A. 2009. The epidemiology and genetics of pituitary adenomas. Best Practice and Research: Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 23 543–554. ( 10.1016/j.beem.2009.05.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Di Ieva A, Rotondo F, Syro LV, Cusimano MD, Kovacs K. 2014. Aggressive pituitary adenomas – diagnosis and emerging treatments. Nature Reviews: Endocrinology 10 423–435. ( 10.1038/nrendo.2014.64) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Emanuel RL, Adler GK, Kifor O, Quinn SJ, Fuller F, Krapcho K, Brown EM. 1996. Calcium-sensing receptor expression and regulation by extracellular calcium in the AtT-20 pituitary cell line. Molecular Endocrinology 10 555–565. ( 10.1210/mend.10.5.8732686) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferry S, Chatel B, Dodd RH, Lair C, Gully D, Maffrand JP, Ruat M. 1997. Effects of divalent cations and of a calcimimetic on adrenocorticotropic hormone release in pituitary tumor cells. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications 238 866–873. ( 10.1006/bbrc.1997.7401) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filippakopoulos P, Qi J, Picaud S, Shen Y, Smith WB, Fedorov O, Morse EM, Keates T, Hickman TT, Felletar I.et al. 2010. Selective inhibition of BET bromodomains. Nature 468 1067–1073. ( 10.1038/nature09504) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa T, Filippakopoulos P. 2017. Functions of bromodomain-containing proteins and their roles in homeostasis and cancer. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 18 246–262. ( 10.1038/nrm.2016.143) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorvin CM, Hannan FM, Cranston T, Valta H, Makitie O, Schalin-Jantti C, Thakker RV. 2018. Cinacalcet rectifies hypercalcemia in a patient with familial hypocalciuric hypercalcemia Type 2 (FHH2) caused by a germline loss-of-function Galpha11 mutation. Journal of Bone and Mineral Research 33 32–41. ( 10.1002/jbmr.3241) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowen M, Stroup GB, Dodds RA, James IE, Votta BJ, Smith BR, Bhatnagar PK, Lago AM, Callahan JF, DelMar EG.et al. 2000. Antagonizing the parathyroid calcium receptor stimulates parathyroid hormone secretion and bone formation in osteopenic rats. Journal of Clinical Investigation 105 1595–1604 ( 10.1172/JCI9038) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hens JR, Dann P, Zhang JP, Harris S, Robinson GW, Wysolmerski J. 2007. BMP4 and PTHrP interact to stimulate ductal outgrowth during embryonic mammary development and to inhibit hair follicle induction. Development 134 1221–1230. ( 10.1242/dev.000182) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer AM, Brown EM. 2003. Extracellular calcium sensing and signalling. Nature Reviews: Molecular Cell Biology 4 530–538. ( 10.1038/nrm1154) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hofer AM, Curci S, Doble MA, Brown EM, Soybel DI. 2000. Intercellular communication mediated by the extracellular calcium-sensing receptor. Nature Cell Biology 2 392–398. ( 10.1038/35017020) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang Y, Breitwieser GE. 2007. Rescue of calcium-sensing receptor mutants by allosteric modulators reveals a conformational checkpoint in receptor biogenesis. Journal of Biological Chemistry 282 9517–9525. ( 10.1074/jbc.M609045200) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang C, Hujer KM, Wu Z, Miller RT. 2004. The Ca2+-sensing receptor couples to Galpha12/13 to activate phospholipase D in Madin-Darby canine kidney cells. American Journal of Physiology: Cell Physiology 286 C22–C30. ( 10.1152/ajpcell.00229.2003) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Joeckel E, Haber T, Prawitt D, Junker K, Hampel C, Thuroff JW, Roos FC, Brenner W. 2014. High calcium concentration in bones promotes bone metastasis in renal cell carcinomas expressing calcium-sensing receptor. Molecular Cancer 13 42. ( 10.1186/1476-4598-13-42) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim W, Takyar FM, Swan K, Jeong J, VanHouten J, Sullivan C, Dann P, Yu H, Fiaschi-Taesch N, Chang W.et al. 2016. Calcium-sensing receptor promotes breast cancer by stimulating intracrine actions of parathyroid hormone-related protein. Cancer Research 76 5348–5360. ( 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-2614) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamonica JM, Deng W, Kadauke S, Campbell AE, Gamsjaeger R, Wang H, Cheng Y, Billin AN, Hardison RC, Mackay JP.et al. 2011. Bromodomain protein Brd3 associates with acetylated GATA1 to promote its chromatin occupancy at erythroid target genes. PNAS 108 E159–E168. ( 10.1073/pnas.1102140108) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lines KE, Stevenson M, Filippakopoulos P, Muller S, Lockstone HE, Wright B, Grozinsky-Glasberg S, Grossman AB, Knapp S, Buck D.et al. 2017. Epigenetic pathway inhibitors represent potential drugs for treating pancreatic and bronchial neuroendocrine tumors. Oncogenesis 6 e332. ( 10.1038/oncsis.2017.30) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lines KE, Filippakopoulos P, Stevenson M, Muller S, Lockstone HE, Wright B, Knapp S, Buck D, Bountra C, Thakker RV. 2020. Effects of epigenetic pathway inhibitors on corticotroph tumour att20 cells. Endocrine-Related Cancer 27 163–174. ( 10.1530/ERC-19-0448) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu CY, Chao TK, Su PH, Lee HY, Shih YL, Su HY, Chu TY, Yu MH, Lin YW, Lai HC. 2009. Characterization of LMX-1A as a metastasis suppressor in cervical cancer. Journal of Pathology 219 222–231. ( 10.1002/path.2589) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamillapalli R, Wysolmerski J. 2010. The calcium-sensing receptor couples to Galpha(s) and regulates PTHrP and ACTH secretion in pituitary cells. Journal of Endocrinology 204 287–297. ( 10.1677/JOE-09-0183) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mamillapalli R, VanHouten J, Zawalich W, Wysolmerski J. 2008. Switching of G-protein usage by the calcium-sensing receptor reverses its effect on parathyroid hormone-related protein secretion in normal versus malignant breast cells. Journal of Biological Chemistry 283 24435–24447. ( 10.1074/jbc.M801738200) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta GU, Lonser RR. 2017. Management of hormone-secreting pituitary adenomas. Neuro-Oncology 19 762–773. ( 10.1093/neuonc/now130) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nemeth EF, Delmar EG, Heaton WL, Miller MA, Lambert LD, Conklin RL, Gowen M, Gleason JG, Bhatnagar PK, Fox J. 2001. Calcilytic compounds: potent and selective Ca2+ receptor antagonists that stimulate secretion of parathyroid hormone. Journal of Pharmacology and Experimental Therapeutics 299 323–331. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nesbit MA, Hannan FM, Howles SA, Babinsky VN, Head RA, Cranston T, Rust N, Hobbs MR, Heath 3rd H, Thakker RV. 2013. Mutations affecting G-protein subunit alpha11 in hypercalcemia and hypocalcemia. New England Journal of Medicine 368 2476–2486. ( 10.1056/NEJMoa1300253) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park PJ.2009. ChIP-seq: advantages and challenges of a maturing technology. Nature Reviews: Genetics 10 669–680. ( 10.1038/nrg2641) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pfaffl MW.2001. A new mathematical model for relative quantification in real-time RT-PCR. Nucleic Acids Research 29 e45. ( 10.1093/nar/29.9.e45) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ramirez F, Ryan DP, Gruning B, Bhardwaj V, Kilpert F, Richter AS, Heyne S, Dundar F, Manke T. 2016. deepTools2: a next generation web server for deep-sequencing data analysis. Nucleic Acids Research 44 W160–W165. ( 10.1093/nar/gkw257) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romoli R, Lania A, Mantovani G, Corbetta S, Persani L, Spada A. 1999. Expression of calcium-sensing receptor and characterization of intracellular signaling in human pituitary adenomas. Journal of Clinical Endocrinology and Metabolism 84 2848–2853. ( 10.1210/jcem.84.8.5922) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossol M, Pierer M, Raulien N, Quandt D, Meusch U, Rothe K, Schubert K, Schoneberg T, Schaefer M, Krugel U.et al. 2012. Extracellular Ca2+ is a danger signal activating the NLRP3 inflammasome through G protein-coupled calcium sensing receptors. Nature Communications 3 1329. ( 10.1038/ncomms2339) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shariq OA, Lines KE. 2019. Epigenetic dysregulation in pituitary tumours. International Journal of Endocrine Oncology 6 [epub]. ( 10.2217/ije-2019-0006) [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Shen X, Rychahou PG, Evers BM, Falzon M. 2007. PTHrP increases xenograft growth and promotes integrin alpha6beta4 expression and Akt activation in colon cancer. Cancer Letters 258 241–252. ( 10.1016/j.canlet.2007.09.010) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonestrom AJ, Hsu SC, Jahn KS, Huang P, Keller CA, Giardine BM, Kadauke S, Campbell AE, Evans P, Hardison RC.et al. 2015. Functions of BET proteins in erythroid gene expression. Blood 125 2825–2834. ( 10.1182/blood-2014-10-607309) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suva LJ, Winslow GA, Wettenhall RE, Hammonds RG, Moseley JM, Diefenbach-Jagger H, Rodda CP, Kemp BE, Rodriguez H, Chen EY. 1987. A parathyroid hormone-related protein implicated in malignant hypercalcemia: cloning and expression. Science 237 893–896. ( 10.1126/science.3616618) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walsh DA, Van Patten SM. 1994. Multiple pathway signal transduction by the cAMP-dependent protein kinase. FASEB Journal 8 1227–1236. ( 10.1096/fasebj.8.15.8001734) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang S, Qiu L, Song H, Dang N. 2018. NPS – 2143 (hydrochloride) inhibits melanoma cancer cell proliferation and induces autophagy and apoptosis. Medicine Science 34 Focus issue F1 87–93. ( 10.1051/medsci/201834f115) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yamamura A, Nayeem MJ, Sato M. 2019. Calcilytics inhibit the proliferation and migration of human prostate cancer PC-3 cells. Journal of Pharmacological Sciences 139 254–257. ( 10.1016/j.jphs.2019.01.008) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarova PL, Stewart AL, Sathish V, Britt Jr RD, Thompson MA, Lowe APP, Freeman M, Aravamudan B, Aravamudan B, Kita H.et al. 2015. Calcium-sensing receptor antagonists abrogate airway hyperresponsiveness and inflammation in allergic asthma. Science Translational Medicine 7 284ra260. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang ZL, Li ZR, Li JS, Wang SR. 2020. Calcium-sensing receptor antagonist NPS-2143 suppresses proliferation and invasion of gastric cancer cells. Cancer Gene Therapy 27 548–557. ( 10.1038/s41417-019-0128-4) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zietek T, Daniel H. 2015. Intestinal nutrient sensing and blood glucose control. Current Opinion in Clinical Nutrition and Metabolic Care 18 381–388. ( 10.1097/MCO.0000000000000187) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zivadinovic D, Tomic M, Yuan D, Stojilkovic SS. 2002. Cell-type specific messenger functions of extracellular calcium in the anterior pituitary. Endocrinology 143 445–455. ( 10.1210/endo.143.2.8637) [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

This work is licensed under a

This work is licensed under a