Abstract

Allosteric peptide inhibitors of thymidylate synthase (hTS) bind to the dimer interface and stabilize the inactive form of the protein. Four interface residues were mutated to alanine, and interaction studies were employed to decode the key role of these residues in the peptide molecular recognition. This led to the identification of three crucial interface residues F59, L198, and Y202 that impart activity to the peptide inhibitors and suggest the binding area for further inhibitor design.

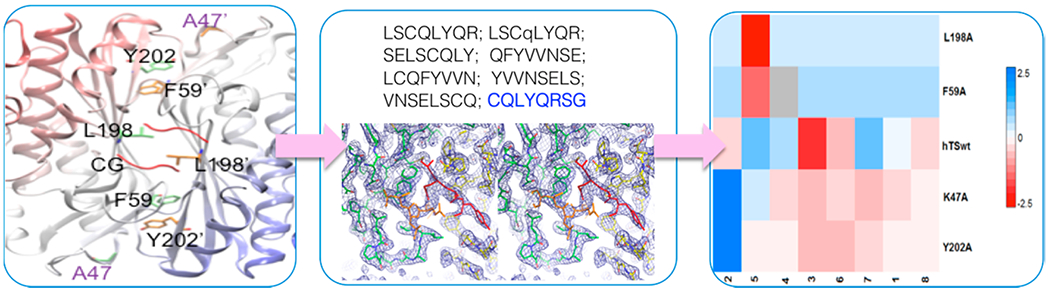

Graphical Abstract

INTRODUCTION

Thymidylate synthases (TS) catalyzes the final step in the biosynthetic pathway for deoxythymidine monophosphate (dTMP) production, which is required for DNA synthesis. Therefore, it serves as an important enzyme in transformed cells and has been intensively studied as a key anticancer drug target.1–4

All chemotherapeutic agents that target human thymidylate synthase (hTS) are either substrate or cofactor analogs that bind to the enzyme active site. The antimetabolite 5-fluorouracil is converted into 5-fluoro-2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate (FdUMP), which is an analog of TS substrate 2′-deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate (dUMP), inside cells.5 Like dUMP, FdUMP forms a covalent ternary complex with the enzyme and cofactor, but it is unable to proceed through subsequent catalytic steps. Structure-based drug design strategy has been intensively employed to design antifolates now used in anticancer therapy, such as raltitrexed6 and pemetrexed7 where one or more moieties are replaced with a new chemical group resulting in an inhibitor that closely resembles the cofactor. But several mechanisms of resistance limit the effectiveness of these drugs, including increasing levels of TS inside cells.8

Binding of substrate or cofactor analog inhibitors may lead to higher levels of TS in the cell through competition with hTS mRNA, which purportedly regulates hTS levels by binding to the enzyme or by stabilization of an enzyme conformation that is resistant to proteosomal degradation.9 We therefore sought to develop a new strategy with hTS inhibitors to target regions outside the active site. Biochemical and structural studies have shown that hTS is an obligate dimer where the interface consists primarily of side chains contributed by β-sheets. There are two arginines from one protomer binding to the phosphate moiety of dUMP bound at the active site of the other. Crystal structures of hTS have revealed two distinct conformations of the enzyme: an “active” conformation, with substrates or inhibitors bound in productive orientations to the active site, and an “inactive” conformation in which the “catalytic loop” (loop 181–197) containing the catalytic cysteine, Cys195, gets refolded to orient the Cys195 side chain toward the dimer interface rather than the active site cavity.10,11 The inactive conformation of hTS is usually seen in structures of apo-hTS crystallized under high salt conditions (1.4 M ammonium sulfate and 20 mM β-mercaptoethanol).10 However, the inactive form of hTS has been shown to also crystallize at a more physiological ionic strength (30 mM ammonium sulfate), indicating the inactive conformation is not an artifact of crystallization conditions.12,13 In solution, apo human thymidylate synthase (hTS) exists as an approximately 3:1 mixture of the “active” and “inactive” conformations.14

Alteration/disruption of the dimer assembly inactivates the enzyme.15 Small molecules dimer disruptors have been already successfully identified for a protease from human Kaposi’s sarcoma-associated herpesvirus (KSHV),16 HIV protease, HIV integrase, cytokine interleukin 2 (IL-2), B-cell lymphoma protein (Bcl-XL), the oncogene human protein double minute 2 (HDM2), and the human papilloma virus transcription factor E2 complex.17–19 Other protein–protein interaction inhibitors have been identified against TS-DHFR from pathogens such as Cryptosporidium hominis.20 We have approached this problem by synthesizing peptides with sequences corresponding to the fragments of the interface region.21 The peptides were derived from the C20 peptide sequence, which show a mechanism of allosteric inhibition against the homodimeric hTS while peptide 2 was derived from ligand-based approach as discussed earlier.22 Eight peptides have been obtained showing inhibitory properties, and for two of them the mechanism of action has been demonstrated through biophysical studies such as ITC, enzyme kinetics. The X-ray crystallographic study shows that the LR peptide, 1, binds at the dimeric interface from where it modulates the enzyme activity. This peptide reduces ovarian cancer cells growth without inducing hTS overexpression.21 In another study, we have also found the key interface residues (termed as “hotspots”) that play crucial role in stabilizing the human TS dimer; mutating them to alanine (A mutants) resulted in weaker dimer association.23 Although these mutants were less likely to be in a dimer state, they were found to be still active. While computational docking studies on the binding mode of the lead LR to the dimeric hTS interface showed a large ensemble of binding modes,21 an experimental approach to shed more light on the contribution of key residues to molecular recognition is necessary for further optimization work.

In this work, we combine targeted mutagenesis and peptides interaction studies to decode the role of important interface residues of hTS in the molecular recognition of the peptides inhibitors. We selected the eight mentioned peptides against the four hTS A mutants (K47A, F59A, L198A, and Y202A). We were also able to crystallize the K47A hTS mutant complexed with CG peptide, 8 (PDB code 4FGT), and performed ITC studies for thermodynamic characterization for its binding to protein. Structure–activity and binding relationships could be identified for almost all peptide inhibitors.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Cells and Cell Culture, Site-Directed Mutagenesis, Expression.

E. coli strain of the wild-type human TS was provided by H. Myllykallio (Ecole Polytechnique, Cedex). The pQE-80L His-tagged vector contains resistance genes for ampicillin. Details are in Supporting Information.

Purification of Recombinant Human TS.

Thymidylate synthase was purified using HisTag affinity purification (50 mM Tris, pH 6.9 (rt), 300 mM KCl, eluted with 500 mM imidazole) and subsequently by size-exclusion chromatography (100 mM HEPES, pH 7.5, 4 °C). The purification was then confirmed by SDS–PAGE gel. The activity of TS was measured spectrophotometrically by monitoring the increase in absorbance at 340 nm in the presence of dUMP and mTHF.

Peptide Purification.

Peptides 1, 3–8 were purchased from GeneCust (www.genecust.com), while peptide 2 was synthesized by Remo Guerrini (University of Ferrara). 1–8 were purified by preparative HPLC using a Kromasil column C18 (250 mm × 4.6 mm, 5 μm spherical particle size). The % purity is reported in parentheses: 1, LSCQLYQR (98); 2, LSCqLYQR (>95); 3, SELSCQLY (99); 4, QFYVVNSE (96); 5, LCQFYVVN (95); 6, YVVNSELS (99); 7, VNSELSCQ (96); 8, CQLYQRSG (96). The column was perfused at a flow rate of 1.0 mL/min with a mobile phase containing solvent A (100%, v/v, acetonitrile in 0.1% TFA) and a linear gradient from 0% to 80% of solvent B (100%, v/v, water in 0.1% TFA) over 25 min for the elution of peptides. For each peptide, the accurate mass has been determined using a Q-TOF mass spectrometer (Supporting Information, p S12).

Enzymatic Inhibition Assay.

The peptide solution was prepared as reported,21 and all peptides were tested against the four mutants. IC50 values were measured for all compounds. The peptides were incubated with the protein for 1 h and the reaction was monitored for 3 min with a spectrophotometric assay that followed cofactor absorbance change at λ = 340 nm for 3 min (refer to Supporting Information for detail). Ki was measured following the previously reported methods.21 Details are reported in Supporting Information. Data analysis, reported in Figure 1, Table 1, and Figure S1 (in Supporting Information), was performed using InfernoRDN software.24

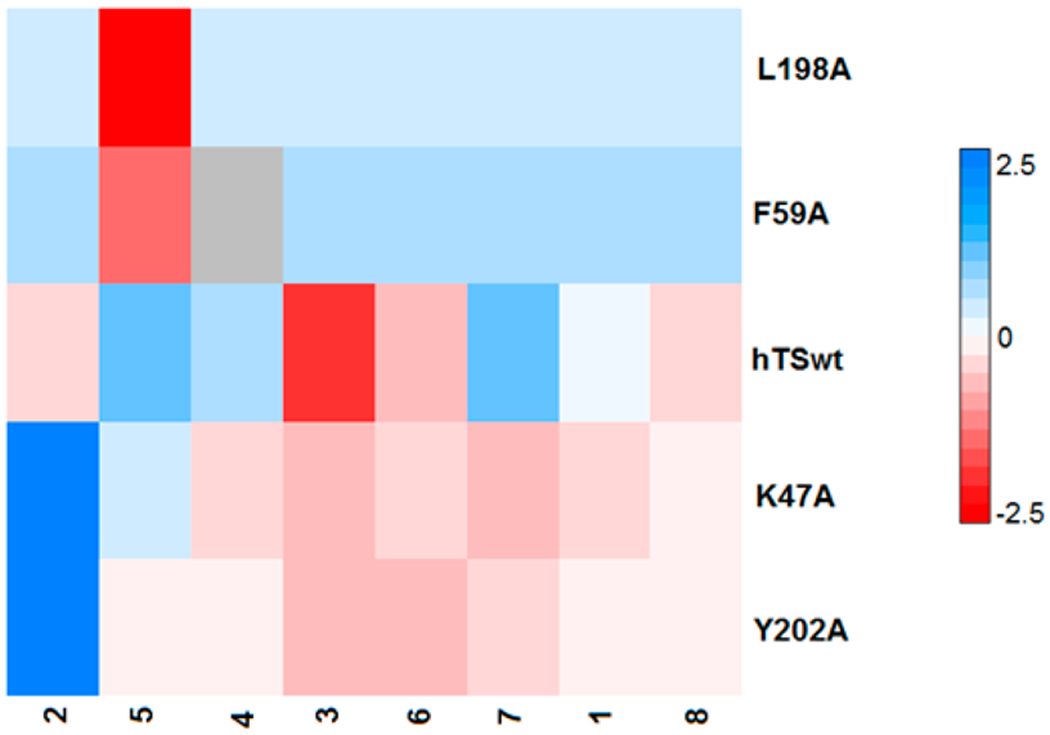

Figure 1.

Scaled IC50 heat map of the peptide inhibition levels on the whole mutant set. IC50 values were normalized using arbitrary units; the compound of reference is peptide 1 against hTSwt (color code bar on the right side). Blue color is associated with higher IC50 (lower inhibition level), while red color (0 to −2.5) is associated with lower IC50 and higher inhibition levels (2.5–0). The gray box indicates not determined data. Each color graduation take into account the comparison with respect to peptide 1, and the intensity is related to for the considered peptide. This imposes different nuance depending on the ΔIC50.

Table 1.

IC50 (μM) Values of the Peptides Tested against hTS and A Mutantsa

| peptide |

||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mutant | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 |

| hTSwt | 75 | 68 | 45 | 81 | 88 | 62 | 88 | 68 |

| K47A | 57 | 152 | 52 | 56 | 80 | 57 | 53 | 63 |

| (+18) | (−84) | (−7) | (+25) | (+8) | (+5) | (+35) | (+5) | |

| F59A | 300b | 300b | 300b | ND | 120 | 300b | 300b | 300b |

| (−225) | (−232) | (−255) | ND | (−32) | (−238) | (−212) | (−232) | |

| L198A | 500 | 300b | 300 | 300b | 188 | 300b | 300 | 300b |

| (−225) | (−232) | (−255) | (−219) | (−100) | (−238) | (−212) | (−232) | |

| Y202A | 67 | 300b | 30 | 71 | 75 | 40 | 50 | 6S |

| (+8) | (−232) | (+15) | (+10) | (+13) | (+22) | (+38) | (0) | |

Numbers in parentheses correspond to ΔIC50 for A mutants with respect to hTSwt. . A negative ΔIC50 corresponds to a better activity of the peptide against the hTSwt than the mutant.

300 μM corresponds to no inhibition at 100 μM peptide.

Protein Crystallization.

For cocrystallization, protein was concentrated at 8–10 mg/mL, mixed with inhibitors at the appropriate ratio with 20 mM βME, and then incubated for about 1 h on ice. The hexagonal form (P3121) of crystals grew in high ammonium sulfate concentration (1.4 M), 20 μM βME, and 0.1 M Tris (or 0.1 M MES for complex with peptide 8), pH 7.0–8.4, at room temperature. They were grown in hanging drops by the vapor diffusion and diffraction method using a Mosquito nL-scale robotic workstation (TTP Labtech). Crystals were grown for a time duration ranging from days to weeks.

X-ray Data Collection and Structure Determination.

X-ray diffraction data were collected from cryoprotected crystals (in 20% ethylene glycol or 20% glycerol) at the beamline 8.3.1 of the Advanced Light Source (Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratories) on a 315r CCD detector. Details are reported in Supporting Information.

Isothermal Titration Colorimetry. Interaction between Human TS/K47 and Peptide 8.

Prior to the day of the experiment, peptide 8 was dissolved in protein buffer (NaH2PO4 20 mM, NaCl 30 mM, pH 7.5) at the desired concentration (c = 25 μM) and was left for magnetic stirring at 4 °C. ITC experiments were conducted with the MicroCal instrument (model: VP-ITC microcolorimeter). Data were analyzed applying different models. Details are reported in the Supporting Information.

RESULTS AND DISCUSSION

Selection of Interface Mutants for Binding Studies.

Our previous studies have enabled us to find crucial hot-spot residues, which when mutated to alanine, led to the decrease in the dimer stability.23 Except for R175A, all mutants showed activity, with Y202A being equally active as the hTSwt (Table S2, Supporting Information). After arranging the mutants in hierarchical order of the enzymatic activity profile, we considered the four topmost mutants (viz. K47A, L198A, F59A, and Y202A), which showed relatively better activity than the others and were well distributed across the interface area (Figure 2A). Such considerations will uncover any long-range effects (if occurring) induced by mutations occurring at farther distances.

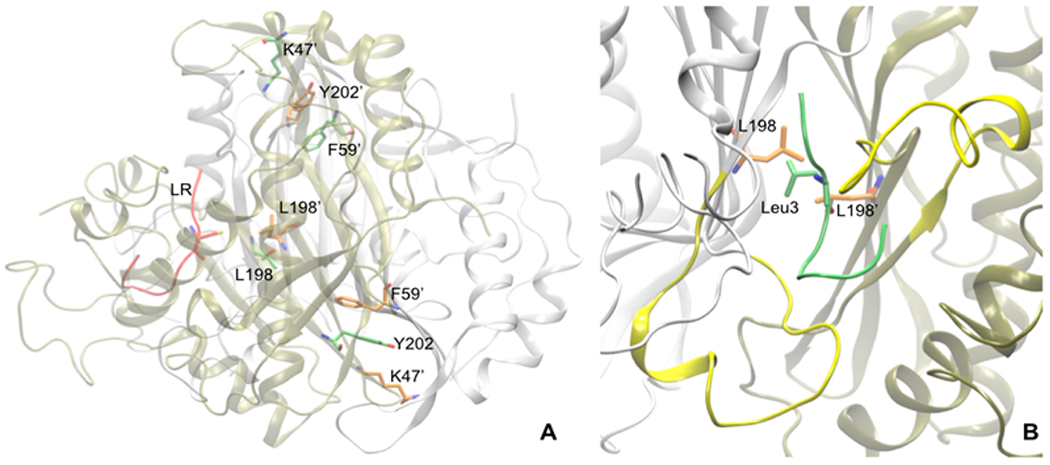

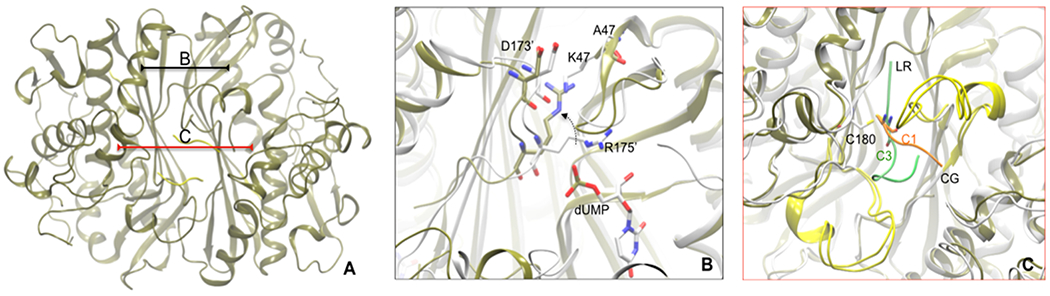

Figure 2.

(A) Cross-sectional view of some of the hotspot interface residues, which were mutated to alanine. The figure also depicts the peptide (in lime, new cartoon representation) binding region along with the flexible loop (shown in yellow). (B) Among the interface residues L198 lies very close to the peptide and directly interacts with the designed peptide 3.

Kinetic Assay of Peptides against hTS Alanine Mutants.

The peptides were tested against hTS mutants, viz. K47A, F59A, L198A, and Y202A. The heat-map results are reported in Figure 1, Table 1 and Figure S3 (Supporting Information) describe the IC50 values of the tested peptides), whereas Figure S1 (Supporting Information) shows PCA-biplot. Both kinds of data analysis suggest that all peptides, with the exception of 2 and 5, have similar activity profile against the A mutants. Peptide 2 profile is markedly affected by Y202A, while the activity of 5 versus this mutant was similar to hTSwt. Residues L198 and F59 play important roles in the binding and activities of the peptide inhibitors. IC50 values of almost all peptides increase drastically (values higher than 300 μM). Since residues K47 and Y202 are located at the opposite side of the peptide-binding region, mutating them to Ala has no effect on the inhibitory values of all the eight peptides. To explain the observed effects, the crystal structure of 1 complexed with hTS was analyzed, revealing that the L198 side chains from the two protomers protrude into the interface region. Application of molecular dynamics calculations on complex 1 bound to hTSwt in our previous work22 has also shown that L198 side chains from both the protomers face each other (Figure 2B) throughout the entire dynamics run, making a hydrophobic contact. Point mutating this residue can significantly affect the peptide interaction with the dimer interface residues. We observed that those peptides containing hydrophobic residues, Leu or Val, at position 3 (in peptides 3, 6, and 8) showed slightly better activity against hTSwt than the other peptides. Assuming that the binding of 1 is similar to those of 2–8, the better activity of these peptides may be due to hydrophobic interactions between the Leu or Val residues at position 3 with L198 (Table 1). Mutating L198 to alanine prevents the aforementioned interactions. However, the change in the peptide activity induced by F59A mutation cannot be easily interpreted, as this residue, like K47 and Y202, is located at the interface region opposite to the peptide’s binding site. But on the basis of our recent results (data unpublished), we know that F59 plays an important role in making hTS dimer stable. It makes aromatic stacking interaction with Y202 from the opposite monomer, which in turn induces stability to the dimer. Mutating it to Ala, cuts off this interaction, leading to dimer instability and partial loss of activity compared to hTSwt. It is therefore assumed that F59A mutation somehow influences the overall conformation of the protein, making it unrecognizable by the peptide, which indirectly affects the peptides’ affinity. Mutating K47 and Y202 to Ala showed only small effects on the activities of the peptides (except 2) in comparison to hTSwt. In particular, the inhibition of Y202A-hTS was increased by 1.3- to 1.8-fold for 3–7. Interaction studies of peptide 2 with the four mutants show that 3 out of 4 mutants were not inhibited by the peptide. The result is in agreement with the previously observed molecular dynamic studies,22 in which it was shown that 2 was better enveloped in the dimeric interface of hTS with respect to 1; therefore, mutations to alanine affect more the peptide interactions.

X-ray Crystal Structure of Peptide 8 with K47A-hTS.

In the attempt to obtain X-ray crystal structures of Y202A and K47A complexed with the peptides, we could only obtain the crystal structure of K47A-hTS bound to peptide 8 (Figure 3A). The crystallographic complex was obtained in high ammonium sulfate concentration, which favors the inactive conformations of the catalytic flexible loop. Analyzing the structure (PDB code 3N5G) in detail revealed that the peptide gets deeply buried in a cleft at the dimer interface, with both hTS protomers in the inactive conformation.21 This result was consistent with the mixed type inhibition kinetics measured for the peptide. In hTSwt, Lys47 lies in a loop containing the key substrate-binding residue Arg50 and donates a hydrogen bond across the dimer interface to the backbone carbonyl of Asp173′ from the second protomer (Figure 3B). To compensate for this mutation, the side chain of Arg175′ adopts a new conformation in K47A-hTS that positions it in the space formerly occupied by the Lys47 side chain (Figure 3B). In hTSwt Arg175′ is one of two arginines donated to the active site of the opposite protomer and is included in the part of the binding site for the phosphate moiety of the substrate, dUMP, or for inorganic phosphate bound to the dUMP site. Reorientation of Arg175′ in K47A abrogates its role in phosphate binding, further weakening the dimer interface. Besides reorientation of Arg175′, the only other structural change in the vicinity of the mutation is a small (~0.8 Å) rigid body shift of the loop containing K47. The eukaryotic inserts in the variable domain were poorly ordered. Density for residues 110–125 was not visible in density maps, and these residues were omitted from the structure. Cys180 and Cys195 lie on the opposite side of the dimer interface from K47 (Figure 3C). While Cys195 and another nearby cysteine, Cys199, appear to be oxidized or modified by βME, there is density consistent with the peptide used for cocrystallization attached via a disulfide bond to Cys180 (Figure 4). Four (CQLY) of the eight residues of the peptide 8 could be fit to density. The rest (QRSG) are presumed to be disordered and therefore are missing in the atom coordinate file. The peptide chain traverses the dimer interface and binds in the hydrophobic groove between the catalytic loop and the eukaryotic insert (residues 145–153) of the opposite protomer (Figure 4). Since the hTS dimer interface has crystallographic 2-fold symmetry, there are two peptides per dimer, each disulfide-bonded to Cys180. We had to model the Gln2 side chain (the second peptide residue) in two conformations to accommodate both peptides without overlaps (two-binding site mode). Another interpretation of the map could be that a single peptide binds to the dimer interface (one-binding site), and the electron density represents the average of two structures, each with the peptide bound to a different protomer, but we did not attempt to model this. Moreover, the analysis of the electron density map revealed that there was a density off at other cysteines, especially at Cys195. This is because in the X-ray structures, the cysteines tend to be oxidized, possibly due to the involvement of βME.

Figure 3.

(A) X-ray crystallographic structure of K47A mutant hTS protein bound to two molecules of peptide 8 (in yellow) at the interface. (B) The region when superimposed to active form of hTS (PDB code 1HVY, in white) describes the local changes brought when K47 residue is mutated to Ala. R175′ side chain (in white) interacts with the phosphate moiety of dUMP substrate molecule present in the other monomeric unit. Mutating K47 to Ala leaves an empty space near D173′ which in turn is filled by the movement (shown in black broken curved line) of R175′ (in tan). (C) The region when superimposed with 1 bound hTS protein (in white) shows binding differences of 1 (in lime) with peptide 8 (in orange). Owing to the presence of Cys1 at N-ter, the peptide binding is shifted down to facilitate sulfide bonding with C180 interface residue.

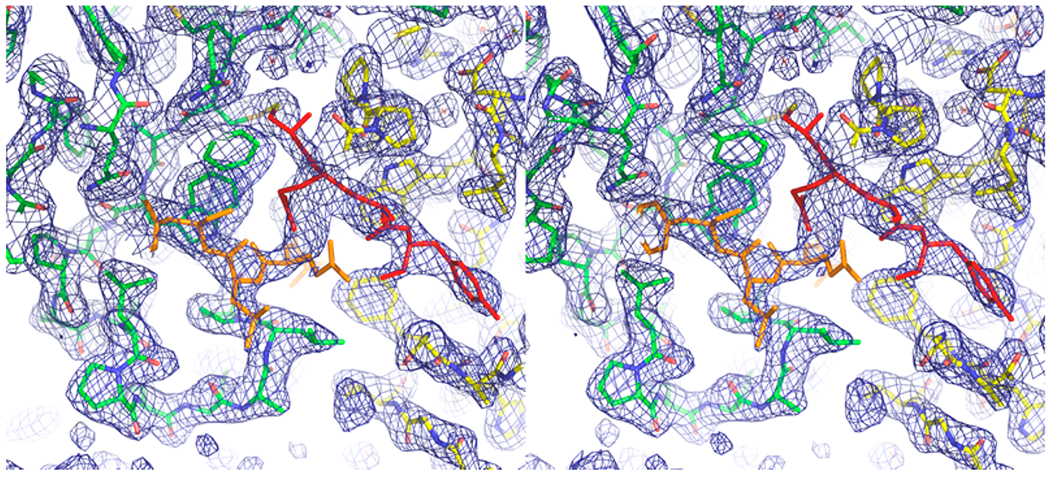

Figure 4.

Stereoview of the dimer interface of K47A hTS bound to peptide 8 (only 4 of the 8 residues were visible in density maps). 2Fo – Fc density contoured at 1σ is shown in blue. The two protomers, which are related by crystallographic 2-fold symmetry, are shown in green and yellow sticks, respectively. Two symmetry-related peptides are drawn in red and orange sticks, respectively. Each is attached via a disulfide bond to Cy180 of one of the protomers. The Gln side chain of the second residue in the peptide lies at the crystallographic 2-fold and is statistically disordered.

Comparison of K47A-8 Complex with the Peptide 1 Binding to Wild Type hTS.

From the obtained crystal structures of 1-bound hTSwt (PDB code 3N5G) and 8-bound K47A mutant (PDB code 4FGT), it can be assumed that each peptide’s Cys has the ability to make a disulfide bond to the interface Cys180 residue of hTS protein, when the latter is in its inactive state. In doing so, the peptide adapts to the conformation that favors this linkage. In our previously reported LR-bound hTSwt crystal structure, the peptide’s Cys at position 3 makes a disulfide bond to Cys180. Favoring this interaction, the peptide adopts a confirmation where the first two residues enter into the narrower interface region, allowing 1 to fit well in the conical interface cavity and hence bind with a larger interaction surface (Figure 3C). Moreover, in the crystal structure of the hTS–1 complex a single peptide 1 is bound to each hTS dimer. Thus, the hTS dimer 2-fold symmetry is broken and the space group symmetry has changed from P3121 to P31. This is in contrast to the case of 8 bound to K47A mutant, the crystals for the hTS–8 complex clearly belong to space group P3121 with one protomer in the asymmetric unit. On the basis of B-factors, the structure contains two fully occupied peptide-binding sites per dimer. Cys1 residue of the peptide is again found to establish disulfide linkage to Cys180 of hTS, but since it is the very first residue, the binding region of the peptide shifts down, leaving the upper narrower cavity untouched (Figure 3C). The peptide 8 thus is less deeply buried and does not induce significant changes to the protein residues in the cleft. This mode of binding becomes less advantageous for the peptide inhibitory activity and could explain the reason for showing low inhibition versus the lead peptide 1.

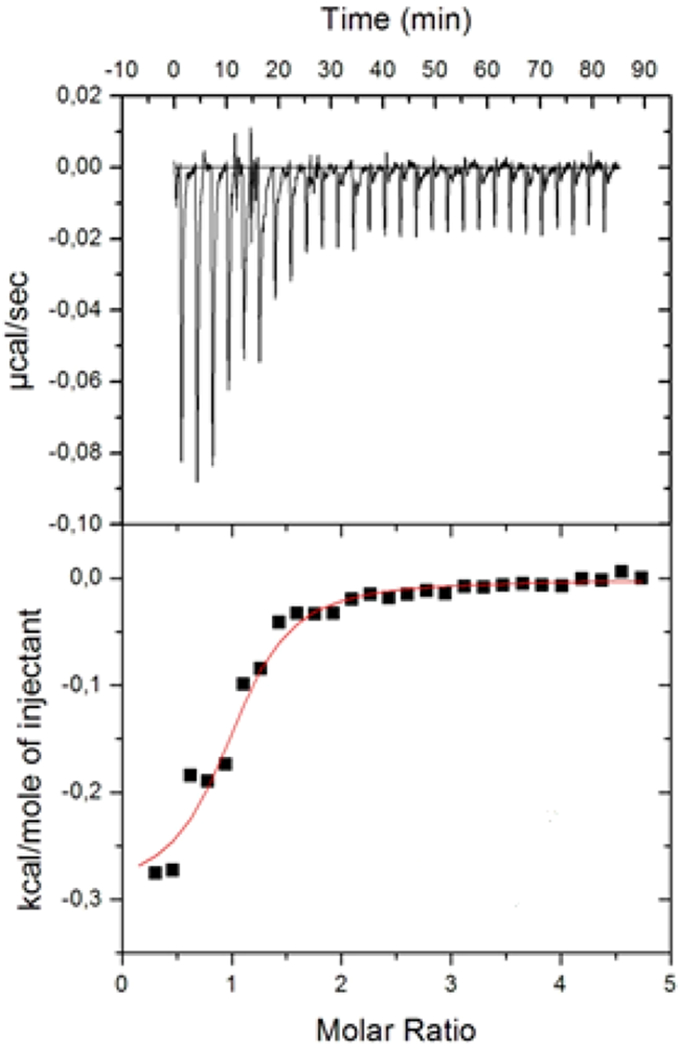

ITC Study of Peptide 8 and K47A-hTS.

To further characterize the binding of 8 to K47A-hTS mutant, ITC experiments were performed. Different binding modes (one-binding-site mode and two-nonidentical-binding-site mode from the software Origin 6) were applied to interpret the calorimetric data. Both the fitting-model results indicate that the interaction is mainly entropically driven, suggesting major involvement of surface contacts, instead of hydrogen bonding, together with increased degrees of freedom (Table S3, Supporting Information). In the two binding sites fitting mode, the entropic and enthalpic contributions for the first binding site (ΔH = −1.24 and TΔS = −29.63 kJ/mol) represent the major interaction heat output, both being larger, with respect to the second binding sites (ΔH = −0.14 and TΔS = −17.34 kJ/mol) in the same mode. Moreover, the thermodynamic signatures obtained for the first binding site in two binding sites fitting mode were similar to the ones obtained applying a single binding site fitting model (ΔH = −1.42 and TΔS = −28.59 kJ/mol). This suggests that the second binding site might just represent a nonspecific minor binding, as reflected by the lower Ka (25.5 × 104 M−1 for the first binding site vs 0.104 × 104 M−1 for the second binding site). Therefore, as we compare the two fitting models, the one-site binding model was more accurate and favorable. The measured entropic contribution may also reflect the high degree of freedom exhibited by the unbound portion (flanking portion) of the peptide 8 that does not play a role in the K47A-hTS binding. These findings are in agreement with the obtained 8 bound to K47A-hTS crystal structure where several stacking and hydrophobic interactions are present in the binding pocket. However, these interactions are different from those between peptide 1 and hTSwt, as peptide 8 is less deeply buried in the dimer interface in K47A-hTS. This also explains the larger contribution in the measured entropy for 8 with K47A-hTS (TΔS = −29.63 kJ/mol) compared to 1 with hTSwt (TΔS = 26.6 kJ/mol). However, 1 exhibited a more extensive H-bond network due to its penetration in the interface, resulting in a larger enthalpic contribution (ΔH = −12.3 kJ/mol compared to ΔH = −1.24 kJ/mol for 8 binding to K47A-hTS). This explains the 10-fold difference in binding Ka between 1 (6.6 × 106) and 8 versus IK47A-hTS (2.55 × 105 M). However, nonidentical two-binding-site mode might be considered as well (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Raw data from ITC study of the interaction of CG with K47A-hTS. The experiments at 25 °C show the heat flux recorded for each titration. Bottom: ΔH vs r plot where ΔH is integrated heat per injection. The red line represents the best fit of the experimental data (black square) using a thermodynamic model considering a one binding site. A fixed stoichiometry of one ligand per binding site was assumed. Errors are within the 5% of the reported values according to instrument sensitivity.

The values of the best-fit thermodynamic parameters are reported in Figure 5 legend. Peptide 8 inhibition of K47A-hTS was investigated in more detail by performing kinetic competition experiments versus mTHF that allowed Ki determination (Figure S2, Supporting Information). Peptide 8 showed a Ki (78 μM) against hTSwt of the same order of peptide 1 (with Ki = 26 μM). The Dixon plot representation shows that 8 inhibits K47A-hTS using a mixed type inhibition mechanism (Figure S2, Supporting Information), in accordance with what was determined against hTSwt. The Ki measured for the peptide 8 for hTSwt (78 μM) is similar to the one against K47A-hTS (60 μM). This result supports the allosteric inhibition mechanism in agreement with that observed in the X-ray complex 8-K47A-hTS, where 8 binds at the protein interface.

CONCLUSIONS

A mutational strategy was adopted to analyze the binding of allosteric peptide inhibitors with four interface alanine mutants of hTS. The activity profiles against these mutant enzymes were similar for all of the tested peptides except peptides 2 and 5. Residues L198 and F59 proved to be highly crucial for the peptides’ activity; when mutated to alanine, the peptide activity was drastically reduced. Mutations of K47 and Y202 to Ala showed no influence on the activities of peptides 1 and 3–8, in comparison to hTSwt. Peptide 2 lost the ability to inhibit Y202A, indicating the key role of this residue in the peptide recognition. This shows that 2 is more active against the hTSwt in comparison to the mutant Y202A, in agreement with the MD simulation studies previously performed on hTSwt where 2 proved to interact with the residue. The interaction of peptide 8 with K47A-hTS was studied in detail; the X-ray crystallographic complex was obtained and suggested that the peptide is only partly bound to the protein dimer interface. This was also demonstrated through the ITC study of the interaction of 8 complexed with K47A. Thermodynamic data analysis from the ITC experiment suggested a large entropic contribution to the binding and a lower Ka due to the reduced number of interactions that peptide 8 can establish with the interface. In agreement with the crystallographic complex, ITC better supports a single binding model where only one peptide molecule is bound to the dimeric protein. Kinetic inhibition pattern studies suggest an allosteric inhibition mechanism. Overall the study of the interaction between peptide 8 and K47A-hTS provides a validation of the mutational strategy adopted, showing a similar profile as peptide 1, previously identified. The target mutational strategy adopted in this study proved useful for the identification of key residues for peptide molecular recognition and gives suggestions about which residues can be considered more susceptible for targeting in dimer interface directed inhibition. L198 was the best residue in the interface core that can be considered as a target for further inhibitors design. However, other residues are also potentially interesting, such as F59A and Y202A.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We thank Dr. James Holton and Dr. George Meigs for their assistance during the data collection at the Advanced Light Source beamline 8.3.1. We thank Remo Guerrini (University of Ferrara) for the synthesis of peptide PF34. We also thank Dr. R. Moser of Merck & Cie Schaffhausen (Switzerland) for providing folate substrate. We thank Filippo Genovese for the IC50 data analysis. We acknowledge PNNL and the omics.pnl. gov Web site for the use of the software (http://omics.pnl.gov/software/infernordn). This work was financially supported by the Italian Association for Cancer Research (Grant IG 10474 to M.P.C.) and LIGHTS (Grant LSH-2005-2.2.0-8) FP6 Project of the European Commission.

ABBREVIATIONS USED

- hTSwt

wild type human thymidylate synthase

- dUMP, 2′

deoxyuridine 5′-monophosphate

- mTHF

methylene tetrahydrofolate

- β-ME

β-mercaptoethanol (2-mercaptoethanol)

- DMSO

dimethyl sulfoxide

- DDW

distilled deioinized water

- ITC

isothermal titration colorimetry

- KM

Michaelis–Menten constant

- Ka

equilibrium constant

- IC50

concentration inhibiting the enzyme by 50%

- Ki

inhibition constant

Footnotes

■ ASSOCIATED CONTENT

Supporting Information

Cells and cell culture, site-directed mutagenesis, expression; enzymatic inhibition assay; X-ray data collection and structure determination including the list of parameters; isothermal titration calorimetry; activity data for the hTS mutants; Dixon plot for kinetic inhibition and IC50 values for the tested peptides against hTS mutants. This material is available free of charge via the Internet at http://pubs.acs.org.

Accession Codes

Coordinates and structure factors for K47A hTS mutant complexed with CG peptide, 8, have been deposited at the Protein Data Bank (PDB code 4FGT).

The authors declare no competing financial interest.

REFERENCES

- (1).Carreras CW; Santi DV The catalytic mechanism and the structure of thymidylate synthase. Annu. Rev. Biochem 1995, 64, 721–762. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Stroud RM; Finer-Moore JS Conformational dynamics along an enzymatic reaction pathway: thymidylate synthase, “the movie”. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 239–247. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Finer-Moore JS; Santi DV; Stroud RM Lessons and conclusions from dissecting the mechanism of bisubstrate enzyme: thymidylate synthase mutagenesis, function and structure. Biochemistry 2003, 42, 248–256. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Wilson PM; Danenberg PV; Johnston PG; Lenz H-J; Ladner RD Standing the test of time: targeting thymidylate biosynthesis in cancer therapy. Nat. Rev. Clin. Oncol. 2014, 11 (5), 282–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Heidelberger C; Danenberg PV; Moran RG Fluorinated pyrimidines and their nucleosides. Adv. Enzymol. Relat. Areas Mol. Biol. 1983, 54, 58–119. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Jackman AL; Taylor GA; Gibson W; Kimbell R; Brown M; Calvert AH; et al. ICI D1694, a quinazoline antifolate thymidylate synthase inhibitor that is a potent inhibitor of L1210 tumor cell growth in vitro and in vivo: a new agent for clinical study. Cancer Res. 1991, 51, 5579–5586. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Shih C; Chen VJ; Gossett LS; Gates SB; MacKellar WC; Habeck LL; et al. LY231514, a pyrrolo[2,3-d]pyrimidine-based antifolate that inhibits multiple folate-requiring enzymes. Cancer Res. 1997, 57, 1116–1123. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Sayre PH; Finer-Moore JS; Fritz TA; Biermann D; Gates SB; MacKellar WC; Patel VF; Stroud RM Multi-targeted antifolates aimed at avoiding drug resistance form covalent closed inhibitory complexes with human and Escherichia coli thymidylate synthases. J. Mol. Biol 2001, 313, 813–829. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).Kitchens ME; Forsthoefel AM; Rafique Z; Spencer HT; Berger FG Ligand-mediated induction of thymidylate synthase occurs by enzyme stabilization. J. Biol. Chem 1999, 274, 12544–12547. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Schiffer CA; Ciesla J; Davisson VJ; Santi DV; Stroud RM Crystal structure of human thymidylate synthase: a structural mechanism for guiding substrates into the active site. Biochemistry 1995, 34, 16279–16287. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Lovelace LL; Gibson LM; Lebioda L Cooperative inhibition of human thymidylate synthase by mixtures of active site binding and allosteric inhibitors. Biochemistry 2007, 46 (10), 2823–2830. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Lovelace LL; Minor W; Lebioda L Structure of human thymidylate synthase under low-salt conditions. Acta Crystallogr. D 2005, 61, 622–627 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Berger SH; Berger FG; Lebioda L Effects of ligand binding and conformational switching on intracellular stability of human thymidylate synthase. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2004, 1696 (1), 15–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Phan J; Steadman D; Koli S; Ding W; Minor W; Dunlap RB; Berger SH; Lebioda L Structure of human thymidylate synthase suggests advantages of chemotherapy with noncompetitive inhibitors. J. Biol. Chem 2001, 276, 14170–14177. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Genovese F; Ferrari S; Guaitoli G; Caselli M; Costi MP; Ponterini G Dimer–monomer equilibrium of human thymidylate synthase monitored by fluorescence resonance energy transfer. Protein Sci. 2010, 19 (5), 1023–1030. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Shahian T; Lee GM; Lazic A; Arnold LA; Velusamy P; Roels CM; Guy RK; Craik CS Inhibition of a viral enzyme by a small-molecule dimer disruptor. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2009, 5 (9), 640–646. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Cardinale D; Salo-Ahen OM; Ferrari S; Ponterini G; Cruciani G; Carosati E; Tochowicz AM; Mangani S; Wade RC; Costi MP Homodimeric enzymes as drug targets. Curr. Med. Chem 2010, 17 (9), 826–846. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Wells JA; McClendon CL Reaching for high-hanging fruit in drug discovery at protein-protein interfaces. Nature 2007, 450 (7172), 1001–1009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Ferrari S; Pellati F; Costi MP Protein–Protein Interaction Inhibitors: Case Studies on Small Molecules and Natural Compounds. In Disruption of Protein–Protein Interfaces; Mangani S, Ed.; Springer: New York, 2013; pp 31–60. [Google Scholar]

- (20).Martucci WE; Udier-Blagovic M; Atreya C; Babatunde O; Vargo MA; Jorgensen WL; Anderson KS Novel non-active site inhibitor of cryptosporidium hominis TS-DHFR identified by a virtual screen. Bioorg. Med. Chem. Lett. 2009, 19 (2), 418–423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (21).Cardinale D; Guaitoli G; Tondi D; Luciani R; Henrich S; Salo-Ahen OM; Ferrari S; Marverti G; Guerrieri D; Ligabue A; Frassineti C; Pozzi C; Mangani S; Fessas D; Guerrini R; Ponterini G; Wade RC; Costi MP Protein–protein interface-binding peptides inhibit the cancer therapy target human thymidylate synthase. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A 2011, 108 (34), 542–549. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (22).Pela M; Saxena P; Luciani R; Santucci M; Fer rari S; Marverti G; Martello A; Pirondi S; Genovese F; Salvadori S; D’Arco D; Ponterini G; Costi MP; Guerrini R Optimization of peptides that target human thymidylate synthase to inhibit ovarian cancer cell growth. J. Med. Chem 2014, 57, 1355–1367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (23).Cardinale D New Ligands Interfering with TS Dimerization. Ph.D. Thesis, University of Modena and Reggio Emilia, Italy, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- (24).InfernoRDN. http://omics.pnl.gov/software/infernordn.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.