Abstract

Purpose

This paper aims to evaluate the decision-making of wisdom teeth extractions (M3s extraction) and the epidemiological profile in the targeted population.

Materials and method

This was a prospective analysis study of 106 patients at our hospital august 20, 1953 specialist hospital, which is a referral center between January 1, 2020 and January 1, 2021. The patients are divided into 2 groups according decision-making of wisdom teeth removal based on scientific evidence if it's right or wrong.

Results

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding sex (P = 0.478), educational level (P = 0.718), or working status (P = 0.606). Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding general co-morbidity (P = 1.00) or oral history (P = 0.28). The mean age of the sample was 32.12 years (SD = 11.337 years, range = 17–70 years, median = 30 -years). We reported that only 28% of the third molars were surgically extracted. We included in Group (I), 81 patients who were treated for third molars removal which the decision-making was justified. In Group (II), 25 patients were treated for third molars removal which the decision-making was unjustified. Group (I) comprised 30 men and 51 women with a mean age of 30 years. Group (II) comprised 7 men and 18 women with a mean age of 27 years. The assessment of surgical outcomes (operating time, blood loss, hospital stay) showed no difference between groups.

Discussion

Monitoring asymptomatic wisdom teeth appears to be an appropriate strategy. Regarding retention versus prophylactic extraction of asymptomatic wisdom teeth, decision-making should be based on the best evidence combined with clinical experience.76.4% had a reason for extraction that was justified. The reasons why extraction of the wisdom tooth was not justified in our study population was either: extraction for prophylaxis or in the case of asymptomatic non-pathological third molars; without scientific evidence.

Conclusion

This subject, which is perpetually debated, requires updating dental health authorities by evaluating new conservative procedures.

Keywords: Decision making, Tooth extraction, Evidence-based dentistry, Third molars, Oral and maxillofacial surgery, Dental caries

Highlights

-

•

Third molars are a major focus of interest in dentistry.

-

•

Preliminary indication and wrong decision-making for teeth extraction have resulted in many healthy teeth being sacrificed.

-

•

Debate continues about the best strategies for the management of wisdom teeth.

1. Introduction

Third molars are a major focus of interest in dentistry due to the diversity of their development and their interaction with the rest of the dentition. The wisdom teeth avulsion is a classic problem in our daily practice; even the issue has received considerable critical attention [1]. Factors found to be influencing third molars extraction have been explored in several studies [[2], [3], [4], [5]]. Questions have been raised about the safety of this medical practice. Researchers have not treated the retention of wisdom teeth in much detail. Debate continues about the best strategies for the management of wisdom teeth.

The study aimed to investigate the indications for wisdom teeth avulsions. The authors will try to evaluate the indication of these extractions and the epidemiological profile of these patients.

2. Materials and methods

This was a prospective analysis study of 106 patients at our hospital august 20, 1953 specialist hospital, which is a referral center between January 1, 2020 and January 1, 2021. The patients are divided into 2 groups according decision-making of wisdom teeth removal based on scientific evidence if it's right or wrong.

All patients who underwent extraction of wisdom teeth under general or local anesthesia are included in the study. The surgeries were performed by a team of residents under the supervision of the chief professor of the maxillofacial surgery department.

This study's data were collected using the files' analysis. The patients were assessed for oral hygiene, infection, wound dehiscence, neuro-sensory deficit, mouth opening, and reasons for a dental visit, operating time, tooth wisdom position, and patterns for extraction.

Data management and analysis were performed using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, version 25.0.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY). Categorical data were summarized as frequencies, and cross-tabulations and ×2 tests for significance made comparisons across allocated groups. Continuous variables were summarized as the mean and range, and comparisons between groups were made using the ANOVA test. All significance tests used a two-sided P-value of 0.05. Simple statistical analysis was used to analyze the relationship between wisdom teeth extraction and other variables.

This case series has been reported in line with the PROCESS criteria [6].

3. Surgical technique

The degree of difficulty of the procedure is directly correlated to the accessibility of the tooth to be avulsed. This accessibility is a function of the teeth’ position within the bone tissue, root morphology, and stage of evolution; as well as the neighboring structures: bone density of the proximal environment, the proximity of adjacent teeth, and proximity of a nerve course (Fig. 1, Fig. 2, Fig. 3).

-

-

Detachment of the attached gingiva with the syndesmotome, on 1–2 mm of height initiated, if necessary, with a blade 15 scalpel without decapitating the interdental papillae.

-

-

Place an elevator perpendicular to the long axis of the tooth to be extracted along its mesial (or distal) side of the tooth, with the concave side facing the tooth to be avulsed, as deep as possible towards the apex. The convex side of the elevator must rest on the alveolar bone and not on the adjacent tooth.

-

-

Rotate the elevator around the long axis of the elevator; an upward levering movement is then exerted upward leverage to break the dentoalveolar attachments. This movement is sometimes sufficient to perform the dental avulsion.

-

-

Using a fissure drill, the tooth is cut to separate the crown from the roots. It is also possible to perform a root separation with a fissure drill, with or without a coronal-radicular section, especially when the roots are convergent or when they cover the inferior alveolar nerve.

-

-

Patients were reviewed at 1, 2, 4, and 6 weeks after surgery. The patients received amoxicillin/clavulanic acid 1 g twice daily and antalgics for 8 days.

-

-

To examine the neuro-sensory deficit, we applied a light touch to one or both sides of the third trigeminal division and asked the patient to show or tell if the sensation is the same on both sides.

-

-

All patients underwent X-rays preoperatively. Furthermore, all patients had at least one postoperative review. The follow-up period for the two groups was equal.

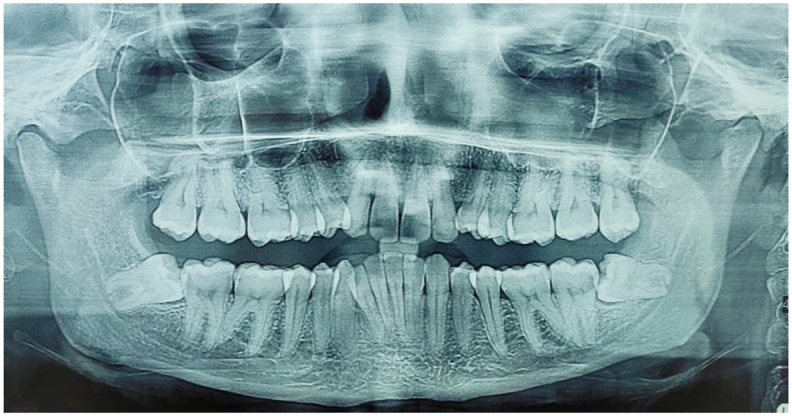

Fig. 1.

The mandibular thirds molars (horizontal impacted position).

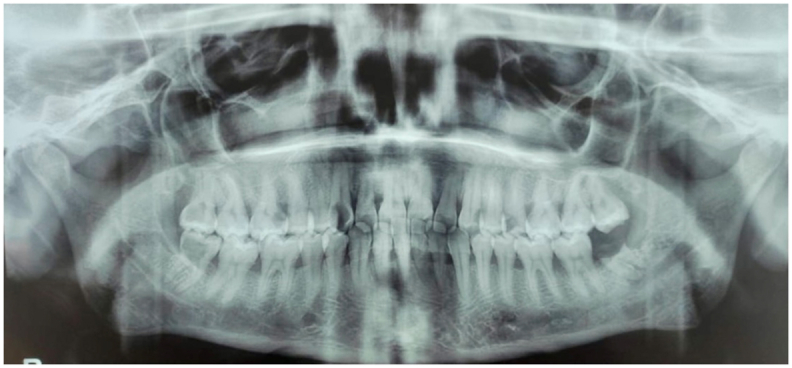

Fig. 2.

The thirds molars (DECAY).

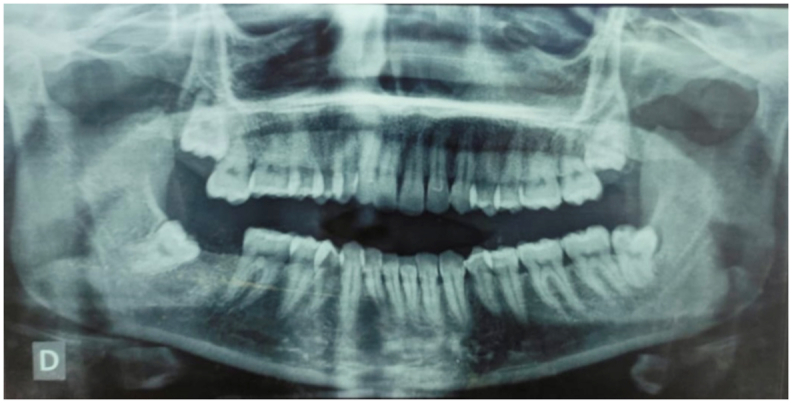

Fig. 3.

On arch position of the third molars.

4. Results

The characteristics of the patients divided into groups, as well as the clinical considerations are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristic of population.

|

Groups |

|||

|---|---|---|---|

| GI (%) | GII (%) | P-value | |

| Mean age (yr.) | 30 (22,5–37.5) | 27 (17–37) | 0.104 |

| Age group | 0.043 | ||

| <20 | 8 (9.9) | 8 (32) | |

| 21 - 40 | 60 (74.1) | 15 (60) | |

| 41 - 60 | 9 (11.1) | 2 (8) | |

| >60 | 4 (4.9) | 0 (0) | |

| Gender | 0.478 | ||

| Female | 51 (63) | 18 (72) | |

| Male | 30 (37) | 7 (28) | |

| Oral hygiene | 0.071 | ||

| Poor | 50 (61.7) | 10 (40) | |

| Average | 13 (16) | 9 (36) | |

| Good | 18 (22.2) | 6 (24) | |

There was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding sex (P = 0.478), educational level (P = 0.718), or working status (P = 0.606). Furthermore, there was no statistically significant difference between the groups regarding general co-morbidity (P = 1.00) or oral history (P = 0.28). (Table 1).

The mean age of the sample was 32.12 years (SD = 11.337 years, range = 17–70 years, median = 30 -years). We reported that only 28% of the third molars were surgically extracted.

We included in Group (I), 81 patients who were treated for third molars removal which the decision-making was justified. In Group (II), 25 patients were treated for third molars removal which the decision-making was unjustified.

Group (I) comprised 30 men and 51 women with a mean age of 30 years.

Group (II) comprised 7 men and 18 women with a mean age of 27 years.

The percentage of wisdom teeth extracted in women, 65.6%, is significantly higher than in men, 34.4%, with a sex ratio of 1.86; explained by the fact that women consult more often than men in general due to their greater motivation for oral hygiene and their preoccupation with appearance and aesthetics.

We note that oral hygiene was generally low; sixty patients in our series had poor dental hygiene, while twenty-four patients had good dental hygiene. No significant differences were found between oral hygiene and the effectiveness of indication (P = 0.071).

The pain is one of the most signs that bring the patients to the consultation; in 73.5% of consultations, 15.1% had functional issues, and 11.3% had esthetic problems. It should also be noted that pain-related reasons for consultation are more frequently found in the younger age group predominant in our study than the older age group who often consults for prosthetic purposes.

Concerning pain and functional issues as reasons for a dental visit, the justified removal third molar group was respectively (80.2%,16%) had a higher rate than the unjustified removal group (52%,12%), when the reason is esthetic, we noted that the rate in the unjustified removal third molar group was higher (36%) than justified removal group (3.7%). This difference between the groups was statistically significant (P < 0.001).

Return to extraction patterns; the dental caries is the main cause of extraction in 31.1% of cases, followed by unexplained facial pain by far 16%. The infectious diseases extraction and prophylactic extraction, representing 28.9%, also noted that ten extractions were not justified when performed in prophylactic cases (Table 2). This result is significant at the p < 0.001 level (see Table 3).

Table 2.

Comparison among the groups depending on the pattern for extraction and reasons of a dental visit.

| Groups |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GI (%) | GII (%) | ||

| Patterns for extraction | <0.001 | ||

| Decay | 28 (34.6) | 5 (20) | |

| Infectious disease | 17 (21) | 1 (4) | |

| Pain | 14 (17.3) | 3 (12) | |

| Traumatic | 14 (17.3) | 2 (8) | |

| Prophylactic | 4 (4.9) | 10 (40) | |

| Periodontal diseases | 4 (4.9) | 4 (16) | |

| Reasons for the dental visit | <0.001 | ||

| Pain | 65 (80.2) | 13 (52) | |

| Esthetic | 3 (3.7) | 9 (36) | |

| Functional | 13 (16) | 3 (12) | |

Table 3.

Comparison among the groups depending on tooth molars position and P&G classification (Class I, II, and III).

| Groups |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GI (%) | GII (%) | ||

| Third molars Position | 0.031 | ||

| - On Arch | 51 (63) | 11 (44) | |

| - Embedded | 17 (21) | 3 (12) | |

| - Impacted | 11 (13.6) | 10 (40) | |

| - Ectopic | 2 (2.5) | 1 (4) | |

| Ramus relationship (P&G classification) | 0.07 | ||

| Class I | 36 (33.9) | 11 (10.3) | |

| Class II | 30 (28.3) | 6 (5.6) | |

| Class III | 15 (14.1) | 8 (7.5) | |

All patients underwent X-rays preoperatively. Furthermore, all patients had at least one postoperative review. The follow-up period for the two groups was similar.

The assessment of surgical outcomes (operating time, blood loss, hospital stay) showed no difference between groups (Table 5).

Table 5.

Comparison of the groups depending on operating time, blood loss, hospital stay.

| Operating time (Mean minutes) | Blood loss (ml) | Hospital stay (mean) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Group (I) | 33 ± 12 | 50 | 1.33 ± 1.27 |

| Group (II) | 37 ± 11 | 55 | 1.44 ± 1.02 |

| P value | 0.093 | 0.062 | 0.3 |

Routine follow-up 1, 3, 6, and 12 months in our specialized consultation; any clinical signs that appeared were mentioned on the patient's discharge form. Mild edema was common during the first week postoperatively in our study; no vascular damage was noted (Table 4).

Table 4.

Comparison of the groups depending on surgical outcomes (wound dehiscence, teeth damage, mouth opening, neurosensory deficit, infection).

| Groups |

P-value | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| GI (%) | GII (%) | ||

| Wound dehiscence | 0.081 | ||

| - Yes | 11 | 6 | |

| - No | 70 | 19 | |

| Adjacent teeth damage | 0.078 | ||

| - Yes | 12 | 8 | |

| - No | 69 | 17 | |

| Mouth opening | 0.4 | ||

| - adequate | 72 | 21 | |

| - inadequate | 9 | 4 | |

| Neuro-sensory deficit | 0.043 | ||

| - Temporary | 7 (6.6) | 3 (2.8) | |

| - permanent | 0 | 3 (2.8) | |

| Infection | 0.06 | ||

| - Yes | 9 | 4 | |

| - No | 72 | 21 | |

5. Discussion

The purpose of this paper was to take a closer look at the critical factors that could influence our decision-making in the removal of wisdom teeth. This study analyzed the teeth’ prognosis, but it is essential to understand that it is influenced by the final overall treatment plan that includes the entire dentition. Genetic determinants were not included in the decision plan; however, they must be considered along with other factors when making a decision [7,8].

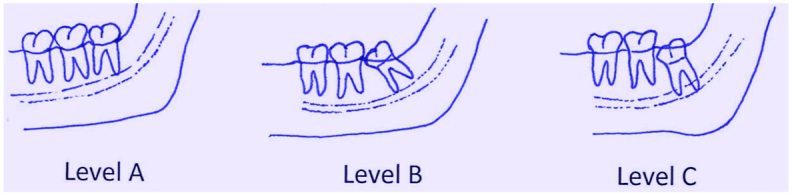

Depth of impaction was defined as the relationship of cementoenamel junction (CEJ) of third molar relative to the bone crest according to the Pell and Gregory's classification; the groups were divided as follows (Fig. 4):

Fig. 4.

Classification of impacted mandibular third molars in terms of depth of impaction.

Level A: CEJ above the bone crest.

Level II: Part of CEJ below the bone crest.

Level III: Entire CEJ below the bone crest.

Dental caries and periodontal disease are the main causes of tooth loss; curative treatment is necessary to maintain oral health, including controlling risk factors such as diet and smoking [9]. Younger adults had less severe clinical oral problems (dental caries and periodontal disease), while older adults often consulted for prosthetic purposes. Pain is the most prevalent self-reported reason for tooth extraction among the adults studied, being aggravated in most cases by the difficulty in accessing dental care [10].

The extraction method was different from those reported in previous studies conducted in oral and maxillofacial units. We reported that only 28% of the third molars were surgically extracted. In the United States study, the extraction method was the opposite, i.e., 24% of extractions were non-surgical [11,12].

Among the subjects presented to the Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery Department of Ibn Rochd University Hospital, 76.4% had a reason for extraction that was justified. The reasons why extraction of the wisdom tooth was not justified in our study population was either: extraction for prophylaxis or in the case of asymptomatic non-pathological third molars; without scientific evidence [5,13]. In our context, 3Ms at the fracture site results in a problematic reduction of fractures and a higher complication rate [13,14]. Studies have also provided strong evidence that retention of the mandibular third molars helps prevent condyle fractures [15,16].

The proximity of the inferior alveolar nerve and the lingual nerve during its mandibular course to the roots of the lower third molars (M3) is a risk factor for the development of nerve damage and subsequent sensory disturbances of the lower lip and tongue after extraction of the third molars [17,18]. To assess this risk, identification of M3 and IAN on panoramic dental radiographs (OPG) and Cone beam is mandatory. The incidence of nerve damage in both groups appears to be low without statistical significance (P: 0.043).

Clinically undetectable pathology cannot be considered an indication for a panoramic radiograph. However, if prevailing clinical practice supports preventive extractions and detection or monitoring of non-erupted third molars, screening for silent underlying vascular malformations, a referral for a panoramic radiograph may be considered good clinical practice [19,20].

In our context, the extraction of wisdom teeth was dominated by young adults of the female sex, and dental caries were the leading cause of poor oral hygiene. Faced with this situation, and to limit the unjustified extractions of wisdom teeth, it is necessary to make our population aware of the third molar role's; not considering it as a generator of problems, to ensure its preservation by good brushing and oral hygiene methods, this can be done through preventive dentistry that involves dental hygienists or through the media. On a professional level, surgeons must be trained and informed about new recommendations [21,22].

Monitoring asymptomatic wisdom teeth appears to be an appropriate strategy. Regarding retention versus prophylactic extraction of asymptomatic wisdom teeth, decision-making should be based on the best evidence combined with clinical experience [[23], [24], [25]].

5.1. There are two currents of thought

-

•

Maxillofacial surgeons maintain that most third molars are potentially pathological and should be extracted.

-

•

The other argues that only those third molars with associated pathology should be removed.

Preliminary indication and wrong decision-making for teeth extraction have resulted in many healthy teeth being sacrificed [7,26].

6. Conclusion

The decision of whether or not to extract the third molar is not resolved. While there is some unanimity regarding the indications for their avulsions when they are symptomatic or cause pathologies, the indications for prophylaxis to prevent mandibular incisor crowding are very controversial evolution of wisdom teeth remains unpredictable; hence the need for sound scientific evidence to justify this practice.

This subject, which is perpetually debated, requires updating dental health authorities by evaluating new conservative procedures.

Provenance and peer review

Not commissioned, externally peer-reviewed.

Ethical approval

Written informed consent was obtained from the patient for publication of this case report and accompanying images. A copy of the written consent is available for review by the Editor-in-Chief of this journal on request.

State any sources of funding for your research

The authors declared that this study has received no financial support.

Registration of research studies

-

1.

Name of the registry: Researchregistry

-

2.

Unique identifying number or registration ID: 6967

-

3.

Hyperlink to your specific registration (must be publicly accessible and will be checked):

Author contribution

Ousmane belem: Corresponding author, writing the paper, Ouassime kerdoud: study concept, study design, writing the paper, Rachid Aloua: data analysis, writing the paper, Amine kaouani: writing the paper, Faiçal Slimani: Correction of the paper.

Guarantor

Ousmane belem.

Declaration of competing interest

Authors of this article have no conflict or competing interests. All of the authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amsu.2021.102639.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following is the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- 1.Huang G.J., Cunha-Cruz J., Rothen M., Spiekerman C., Drangsholt M., Anderson L., Roset G.A. A prospective study of clinical outcomes related to third molar removal or retention. Am. J. Publ. Health. 2014;104:728–734. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301649. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Marciani R.D. Third molar removal: an overview of indications, imaging, evaluation, and assessment of risk. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. Clin. 2007 doi: 10.1016/j.coms.2006.11.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Low S.H., Lu S.L., Lu H.K. Evidence-based clinical decision making for the management of patients with periodontal osseous defect after impacted third molar extraction: a systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Dent. Sci. 2021;16 doi: 10.1016/j.jds.2020.06.018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Zadik Y., Levin L. Decision making of Israeli, east European, and South American dental School graduates in third molar surgery: is there a difference? J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2007;65 doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2006.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Steed M.B. The indications for third-molar extractions. J. Am. Dent. Assoc. 2014;145:570–573. doi: 10.14219/jada.2014.18. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Agha R.A., Sohrabi C., Mathew G., Franchi T., Kerwan A., O'Neill N., Thoma A., Beamish A.J., Noureldin A., Rao A., Vasudevan B., Challacombe B., Perakath B., Kirshtein B., Ekser B., Pramesh C.S., Laskin D.M., Machado-Aranda D., Pagano D., Roy G., Kadioglu H., Nixon I.J., Mukhejree I., McCaul J.A., Chi-Yong Ngu J., Albrecht J., Rivas J.G., Raveendran K., Derbyshire L., Ather M.H., Thorat M.A., Valmasoni M., Bashashati M., Chalkoo M., Teo N.Z., Raison N., Muensterer O.J., Bradley P.J., Goel P., Pai P.S., Afifi R.Y., Rosin R.D., Coppola R., Klappenbach R., Wynn R., Surani S., Giordano S., Massarut S., Raja S.G., Basu S., Enam S.A., Manning T.G., Cross T., Karanth V.K., Mei Z. The PROCESS 2020 guideline: updating consensus preferred reporting of CasE series in surgery (PROCESS) guidelines. Int. J. Surg. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2020.11.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Avila G., Galindo-Moreno P., Soehren S., Misch C.E., Morelli T., Wang H.-L. A novel decision-making process for tooth retention or extraction. J. Periodontol. 2009;80:476–491. doi: 10.1902/jop.2009.080454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hyam D.M. The contemporary management of third molars. Aust. Dent. J. 2018;63 doi: 10.1111/adj.12587. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.McCaul L.K., Jenkins W.M.M., Kay E.J. The reasons for extraction of permanent teeth in Scotland: a 15-year follow-up study. Br. Dent. J. 2001 doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.4801068. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Silva-Junior M.F., de Sousa A.C.C., Batista M.J., de Sousa M. da L.R. Oral health condition and reasons for tooth extraction among an adult population (20-64 years old) Ciência Saúde Coletiva. 2017 doi: 10.1590/1413-81232017228.22212015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Susarla S.M., Dodson T.B. Predicting third molar surgery operative time: a validated model. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2013 doi: 10.1016/j.joms.2012.08.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kautto A., Vehkalahti M.M., Ventä I. Age of patient at the extraction of the third molar. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2018 doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2018.03.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shoshani-Dror D., Shilo D., Ginini J.G., Emodi O., Rachmiel A. Quintessence Int. (Berl); 2018. Controversy regarding the need for prophylactic removal of impacted third molars: an overview. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kerdoud O., Aloua R., kaouani A., Slimani F. Management of mandibular angle fractures through single and two mini-plate fixation systems: retrospective study of 112 cases. Int. J. Surg. Case Rep. 2021;80 doi: 10.1016/j.ijscr.2021.105690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Zhu S.J., Choi B.H., Kim H.J., Park W.S., Huh J.Y., Jung J.H., Kim B.Y., Lee S.H. Relationship between the presence of unerupted mandibular third molars and fractures of the mandibular condyle. Int. J. Oral Maxillofac. Surg. 2005 doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2004.10.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Iida S., Nomura K., Okura M., Kogo M. Influence of the incompletely erupted lower third molar on mandibular angle and condylar fractures. J. Trauma Inj. Infect. Crit. Care. 2004 doi: 10.1097/01.TA.0000096647.36992.83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Vinayahalingam S., Xi T., Bergé S., Maal T., de Jong G. Automated detection of third molars and mandibular nerve by deep learning. Sci. Rep. 2019;9 doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-45487-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Bellaiche N., Azoulay E. Cone beam et troisième molaire mandibulaire incluse. Rev. Orthop. Dento. Faciale. 2019;53 doi: 10.1051/odf/2019004. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vesala T., Ekholm M., Ventä I. Is dental panoramic tomography appropriate for all young adults because of third molars? Acta Odontol. Scand. 2021;79 doi: 10.1080/00016357.2020.1776384. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ramírez A., Rodríguez G M., Sánchez P R. Prophylactic removal of the third molars a clinical making decisions. Rev. Fac. Med. 2008;56 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bataineh A.B., Albashaireh Z.S., Hazza’a A.M. The surgical removal of mandibular third molars: a study in decision making. Quintessence Int. 2002;33 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Haug R.H., Abdul-Majid J., Blakey G.H., White R.P. Evidenced-based decision making: the third molar, dent. Clin. North Am. 2009;53 doi: 10.1016/j.cden.2008.09.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Song F., O'Meara S., Wilson P., Golder S., Kleijnen J. The effectiveness and cost-effectiveness of prophylactic removal of wisdom teeth. Health Technol. Assess. 2000 doi: 10.3310/hta4150. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Dirk T., Mettes G., Ghaeminia H., EL Nienhuijs M., Perry J., van der Sanden W.J., Plasschaert A. Surgical removal versus retention for the management of asymptomatic impacted wisdom teeth. Cochrane Database Syst. Rev. 2012 doi: 10.1002/14651858.cd003879.pub3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Meneu R. The wisdom tooth of health technology assessment. Heal. Technol. Assess. Heal. Policy Today A Multifaceted View Their Unstable Crossroads. 2015 doi: 10.1007/978-3-319-15004-8_3. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Camargo I.B., Melo A.R., Fernandes A.V., Cunningham L.L., Laureano Filho J.R., Van Sickels J.E. Decision making in third molar surgery: a survey of Brazilian oral and maxillofacial surgeons. Int. Dent. J. 2015;65 doi: 10.1111/idj.12165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.