Abstract

Background & Aims

Nourishment of gut microbiota via consumption of fermentable fiber promotes gut health and guards against metabolic syndrome. In contrast, how dietary fiber impacts type 1 diabetes is less clear.

Methods

To examine impact of dietary fibers on development of type 1 diabetes in the streptozotocin (STZ)-induced and spontaneous non-obese diabetes (NOD) models, mice were fed grain-based chow (GBC) or compositionally defined diets enriched with a fermentable fiber (inulin) or an insoluble fiber (cellulose). Spontaneous (NOD mice) or STZ-induced (wild-type mice) diabetes was monitored.

Results

Relative to GBC, low-fiber diets exacerbated STZ-induced diabetes, whereas diets enriched with inulin, but not cellulose, strongly protected against or treated it. Inulin’s restoration of glycemic control prevented loss of adipose depots, while reducing food and water consumption. Inulin normalized pancreatic function and markedly enhanced insulin sensitivity. Such amelioration of diabetes was associated with alterations in gut microbiota composition and was eliminated by antibiotic administration. Pharmacologic blockade of fermentation reduced inulin’s beneficial impact on glycemic control, indicating a role for short-chain fatty acids (SCFA). Furthermore, inulin’s microbiota-dependent anti-diabetic effect associated with SCFA-independent restoration of interleukin 22, which was necessary and sufficient to ameliorate STZ-induced diabetes. Inulin-enriched diets significantly delayed diabetes in NOD mice.

Conclusions

Fermentable fiber confers microbiota-dependent increases in SCFA and interleukin 22 that, together, may have potential to prevent and/or treat type 1 diabetes.

Keywords: Inulin, Cellulose, Gut Microbiota, Insulin Resistance, Type 1 Diabetes

Abbreviations used in this paper: CDD, compositionally defined diet; GBC, grain-based chow; HbA1c, glycosylated hemoglobin; IL, interleukin; IP, intraperitoneally; LEfSe, linear discriminant analysis effect size; NOD, non-obese diabetes; PBS, phosphate-buffered saline; qPCR, quantitative polymerase chain reaction; SCFA, short-chain fatty acids; STZ, streptozotocin; T1D, type 1 diabetes; T2D, type 2 diabetes; WSD, Western style diet; WT, wild-type

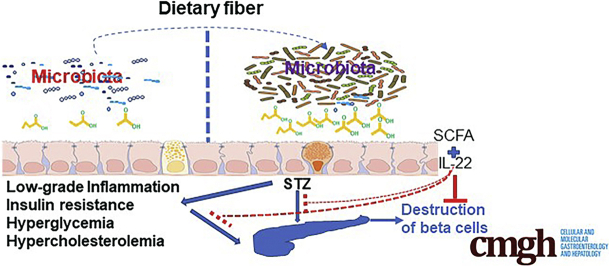

Graphical abstract

Summary.

Gut microbiota play an important role in the development of type 1 diabetes. We show herein that fermentable fiber inulin modulates gut microbiota to prevent and treat STZ-induced diabetes and to delay diabetes development in non-obese diabetes (NOD) mouse models.

Type 1 diabetes (T1D), a major and increasing worldwide public health problem, is characterized by the destruction of insulin-producing β cells, resulting in insulin deficiency and, consequently, hyperglycemia as well as a variety of resulting interrelated complications. Although host genetics determine proneness to T1D, increasing evidence supports an important role for environmental (ie, non-genetic) factors, including diet and gut microbiota. For example, depletion of gut microbiota by antibiotics partially reduces disease onset in T1D rats.1, 2, 3 Furthermore, a variety of alterations in gut microbiota composition are reported in T1D patients,4,5 some of whom also exhibit disrupted intestinal barrier function.6,7 These studies suggest that altering gut microbiota via diet may influence development of T1D.

Numerous studies of humans and animal models indicate that dietary fiber can modulate gut microbiota and ameliorate aspects of metabolic syndrome including insulin resistance.8, 9, 10, 11 Metabolic benefits of fiber, particularly those provided by soluble fibers, result, at least in part, from them being fermented by gut bacteria. Fermentation products themselves, namely short-chain fatty acids (SCFA), provide an array of metabolic benefits including increased production of and sensitivity to insulin, thus protecting against type 2 diabetes (T2D). Furthermore, independent of SCFA, nourishing gut bacteria with fermentable fiber promotes intestinal health in a manner that promotes better management of gut microbiota, thus ameliorating the low-grade inflammation and consequently preventing insulin resistance. In addition and/or alternatively, dietary fiber has potential to reduce insulin resistance by ameliorating numerous aspects of metabolic syndrome including hyperphagia, adiposity, and hyperlipidemia, in part by restoring expression of interleukin (IL) 22, which is lost in mice fed low-fiber diets.11

Research on fiber in the context of obesity and metabolic syndrome has resulted in nutritional guidelines increasingly recommending increased consumption of fermentable fiber as a means of promoting metabolic health and protecting against T2D.8,12 In contrast, the potential value of modulating gut microbiota via fiber in T1D is less extensively studied. Although T1D is primarily driven by destruction of pancreatic β cells, insulin sensitivity also impacts disease severity.13 Hence, we tested the potential of fermentable fiber to ameliorate T1D using 2 well-established models of this disease, namely the highly tractable streptozotocin (STZ)-induced and spontaneous genetic non-obese diabetes (NOD) mouse models. We observed a striking potential for fermentable fiber to prevent and treat STZ-induced diabetes and to delay diabetes development in the NOD model. Such protection in the STZ model required gut microbiota, fermentation, and IL22, which, by itself, was able to ameliorate diabetes development.

Results

Enrichment of Diet With Fermentable Fiber Protects Against STZ-Induced Diabetes

An important consideration in diet-based research is selection of a control diet. One logical choice is grain-based rodent chow (GBC), which has long been widely used to maintain lab rodents, but this diet is hard to precisely manipulate and also varies seasonally, thus making its composition difficult to specify. One of the well-appreciated areas of variance of GBC relates to its fiber content, which crude methods of analysis indicate comprises 5%–8% of the diet’s mass, whereas more advanced methods reveal that GBC has a total fiber content of 15%–25% fiber when purchased from various providers14 or when comparing batches from the same provider.15 Accordingly, many studies use GBC to serve as a high-fiber diet and compare it with a compositionally defined diet (CDD) designed to lack fiber.16,17 By comparison, a widely used “open-source” CDD mimics the overall fat, protein, and carbohydrate levels of GBC, thus justifying its use as a control diet in many studies. However, this commonly used CDD has a total fiber content of only 5%, which is composed entirely of insoluble fiber, cellulose, thus supporting its use as a low-fiber diet.11,16,18

The alkylating agent STZ is highly and preferentially toxic to pancreatic β cells, enabling daily low-dose STZ treatment to serve as a model of T1D.19 Accordingly, subjecting GBC-fed C57BL/6 mice to 5 daily injections of STZ resulted in a marked sustained hyperglycemia (Figure 1A and B). Reminiscent of earlier work,18 feeding mice CDD by itself promoted adiposity but did not induce hyperglycemia (Figure 1B–D). However, relative to GBC, consumption of CDD resulted in exacerbated diabetes in response to STZ as assessed by measure of blood glucose, adiposity, and pancreatic mass (Figure 1), leading us to hypothesize that dietary fiber might ameliorate diabetes development.

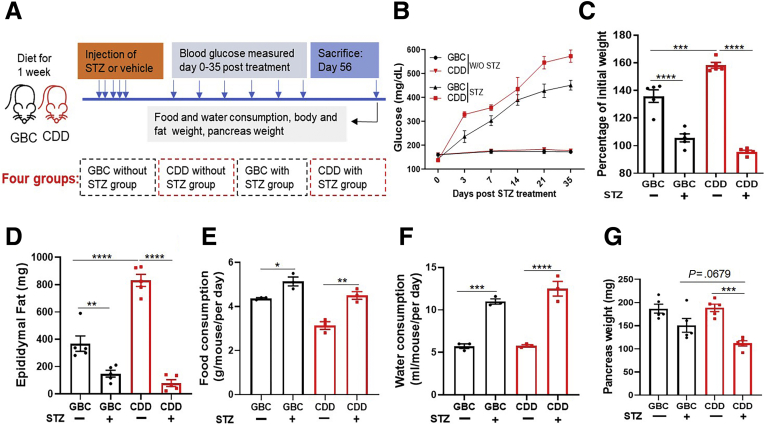

Figure 1.

Low-fiber diet exacerbated severity of STZ-induced diabetes. (A) C57BL/6 male mice (n = 5) at age of 7 weeks were fed with GBC or CDD for 1 week, after which some mice were injected with low dose of STZ for 5 constitutive days as schematized. (B) Mice were monitored for blood glucose until 5 weeks after STZ treatment. (C) Change in body mass at 8 weeks after treatment relative to initial weight; (D) epididymal fat mass; (E and F) food and water consumption; (G) pancreas weight.

To directly test the possibility that fiber protects against STZ-induced diabetes, CDD was enriched with soluble fiber, inulin, which is readily fermented by gut bacteria, or an insoluble fiber, cellulose, which is difficult for non-ruminant animals to ferment. These diets, which were administered 1 week before STZ treatment and referred to as CDD:Cell and CDD:Inul, had total fiber contents of 20%, approximating that of GBC (Figure 2A). Relative to mice consuming CDD, those fed CDD:Inul displayed modest reductions in systemic indices of inflammation including the percentage of splenic neutrophils (Figure 2B and C). Moreover, CDD:Inul-fed mice were markedly protected against STZ-induced diabetes on the basis of levels of blood glucose and glycosylated hemoglobin (HbA1c), whereas CDD:Cell provided only very modest protection (Figure 2F and G). Such better glycemic control of CDD:Inul-fed mice broadly correlated with reduced disease by all diabetes-related parameters measured. Specifically, STZ-treated mice fed CDD exhibited loss of adipose mass (Figure 2H), hyperphagia (Figure 2I), and polydipsia (Figure 2J), all of which are features of uncontrolled T1D in humans. Enrichment of the diet with inulin, but not cellulose, almost fully normalized these diabetic parameters. In addition, irrespective of STZ, CDD:Inul reduced levels of serum cholesterol and triglycerides (Figure 2K and L), both of which are common comorbidities of diabetes and which were modestly increased by STZ. Furthermore, STZ-induced kidney hypertrophy/dysfunction, which also occurs in severe T1D, was prevented by enrichment of CDD with inulin but not cellulose as assessed by kidney appearance, weight, and blood urea nitrogen (Figure 3A–C).

Figure 2.

Enrichment of low-fiber diet with inulin but not cellulose prevented STZ-induced diabetes. (A) Five-week-old C57BL/6 male mice were fed CDD, CDD:Cell, or CDD:Inul and 1 week later injected with vehicle or STZ (50 mg/kg) for 5 constitutive days as schematized. (B–E) Innate immune cells in spleen were analyzed by flow cytometry (FACS) before STZ treatment. Representative flow cytometry plot included neutrophils (CD45+, CD11b+, MHCII-Ly6G+), DC (CD45+, CD11b-, CD11c+) (C), macrophages (CD45+, CD11b+, MHCII+) (B). Percentage of neutrophils (C), DC (D), and macrophages (E) was calculated in spleen. (F) Non-fasting glucose was monitored weekly. (G and H) HbA1c in blood (G) and epididymal fat mass (H) were measured at end of experiment (12 weeks after STZ). (I and J) Two weeks before euthanasia, food (I) and water (J) consumption was measured daily over several 24-hour periods. (K and L) Cholesterol (K) and triglycerides (L) in serum were measured. Data are means ± standard error of the mean (n = 4–10 mice per group) of an individual experiment and representative of at least 2 separate experiments.

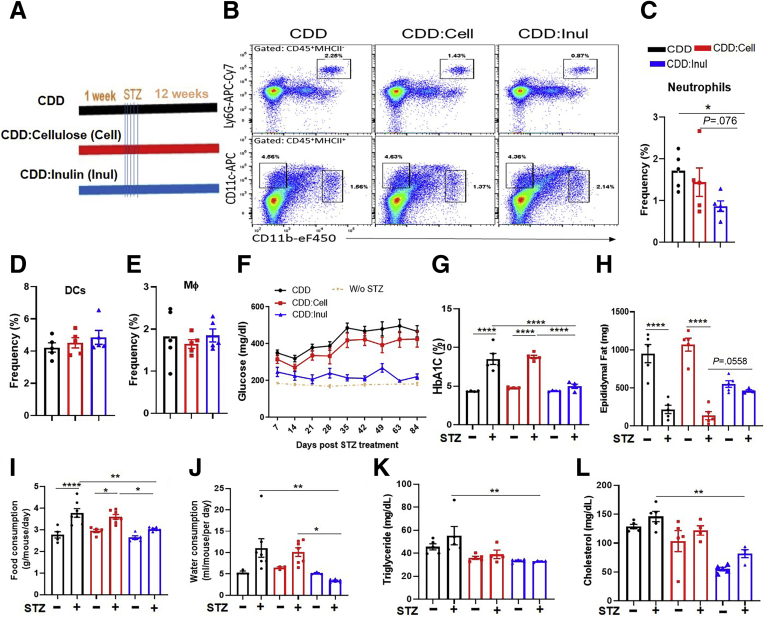

Figure 3.

Inulin-enriched diet prevented STZ-induced kidney and pancreatic islet damage. (A–C) STZ-treated and untreated mice were euthanized at end of experiment (12 weeks and STZ); kidney weight (A) and images of kidney in STZ-treated mice (B); blood urea nitrogen (BUN) in serum of mice measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay (C). (D–H) Pancreas weight (D) and insulin staining per section were calculated using ImageJ software (E); representative image of HE and immunofluorescence microscopy; insulin (green), counterstained with DAPI (blue) in STZ-treated mice (F). (G and H) MCP-1 (G) and IL6 (H) in pancreas measured by quantitative real-time PCR. Data are means ± standard error of the mean (n = 4–9 mice per group) of an individual experiment and representative of at least 2 separate experiments.

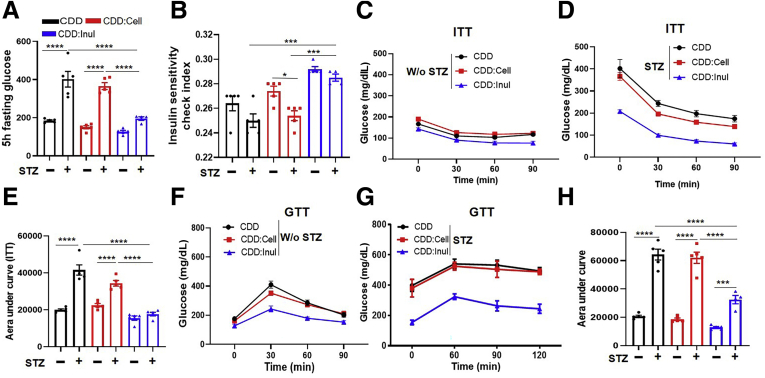

Because of the central role of pancreatic islet destruction in STZ-induced diabetes, we expected inulin’s protection against STZ-induced diabetes might correlate with preservation of insulin-containing pancreatic islets. In accord with this notion, feeding of CDD:Inul prevented STZ-induced loss of pancreatic mass and preserved pancreatic insulin staining (Figure 3D–F). Such protection was associated with reduced levels of inflammatory cytokines expression including MCP-1 and IL6 in the pancreas (Figure 3G and H). In addition, CDD:Inul also increased insulin sensitivity and did so irrespective of STZ treatment, as indicated by assay of fasting blood glucose levels and the Insulin Sensitivity Index (Figure 4A and B). Accordingly, relative to mice fed CDD or CDD:Cell, those fed CDD:Inul displayed greater sensitivity to exogenously administered insulin (Figure 4C–E). Moreover, in mice that were and were not treated with STZ, feeding the inulin-enriched diet markedly improved glycemic control as assessed by glucose tolerance testing (Figure 4F–H).

Figure 4.

Inulin-enriched diets increased insulin sensitivity. (A and B) STZ-treated and untreated mice at 11 weeks after STZ treatment were fasted for 5 hours; glucose was measured (A), and insulin sensitivity check index was calculated (B). (C–E) Mice without or with STZ treatment were fasted for 5 hours, injected IP with insulin at dose of 5 or 7.5 U/g body weight, respectively, and glucose was measured at indicated time points (insulin tolerance test [ITT]) (C and D); area under curve was calculated (E). (F–H) Five-hour fasted mice were administered with glucose (2 g/kg body weight) IP to measure glucose tolerance test (GTT) (F and G); area under curve was calculated (H).

Inulin-Enriched Diet Treats STZ-Induced Diabetes

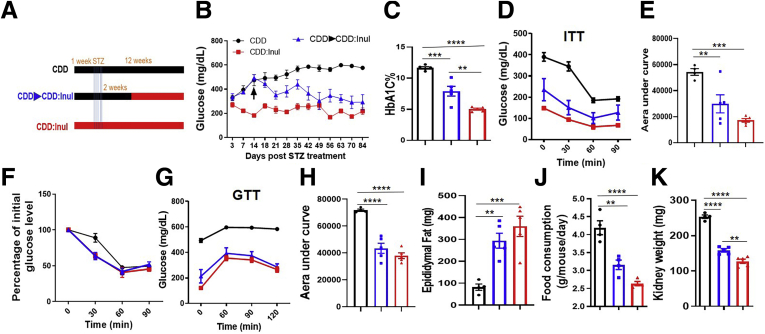

We next sought to investigate the potential of fermentable fiber to ameliorate STZ-induced diabetes after disease had been established. CDD-fed mice were treated with STZ to induce diabetes as described above. Two weeks later, at which time marked hyperglycemia was evident, some mice were switched to CDD:Inul (Figure 5A). Mice fed CDD throughout the experiment displayed glucose levels that continued to rise for several weeks after STZ treatment, whereas glucose levels of mice switched to CDD:Inul declined toward, but did not reach, the normal glucose levels exhibited by STZ-treated mice that had consumed CDD:Inul throughout the experiment (Figure 5B). Concomitantly, such mice switched to CDD:Inul after hyperglycemia was established showed marked improvements in all diabetes-related parameters measured including HbA1c (Figure 5C), insulin sensitivity (Figure 5D–F), and glucose tolerance (Figure 5G and H) amidst restoration of adipose mass (Figure 5I), which occurred despite reduced food consumption (Figure 5J) and which was accompanied by reduced kidney hypertrophy (Figure 5K). Thus, diets rich in fermentable fiber inulin may have potential to both prevent and treat diabetes.

Figure 5.

Treatment of established STZ-induced diabetes by inulin-enriched diet. (A) Mice were fed CDD or CDD:Inul diets for 1 week before IP injection with low dose of STZ for 5 constitutive days. One group of CDD fed mice was then switched to CDD:Inul at 2 weeks after STZ treatment. (B and C) Glucose was monitored (B); HbA1c in blood was measured at end of experiment (C). (D–F) Insulin tolerance test (ITT) was measured (D), area under curve was calculated (E), and percentage of decreased glucose as compared with initial glucose based on ITT of D (F). (G and H) Glucose tolerance test (GTT) was measured (G); area under curve was calculated (H). (I–K) Epididymal fat (I), food consumption (J), and kidney weight (K). Data are means ± standard error of the mean (n = 4–5 mice per group) of an individual experiment and representative of at least 2 separate experiments.

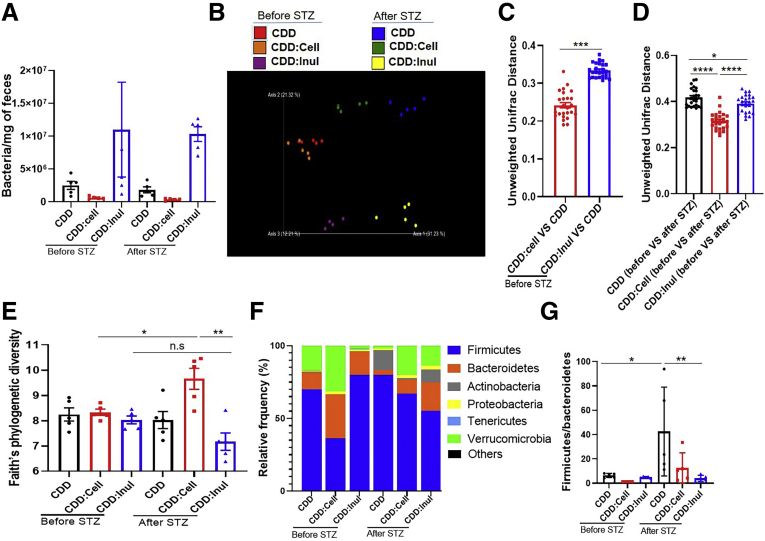

Impact of Fiber and STZ on Gut Microbiota

Inulin’s protection against Western style diet (WSD)–induced metabolic syndrome is mediated by gut microbiota.10,11 Hence, we next examined the impact of fiber consumption on microbiota in the context of STZ-induced diabetes. Analogous to our work with WSD, inulin enrichment of CDD led to a marked enhancement in the total amount of bacteria per mg feces, ie, bacterial density, which was not impacted by STZ treatment (Figure 6A). In further accord with previous studies, enrichment of CDD with inulin had a greater impact on overall microbiota composition than did cellulose as visualized via principal coordinate analysis (Figure 6B). This notion was confirmed by measure of the Uni-Frac distances separating CDD and CDD:Inul samples, which were significantly higher compared with those of CDD and CDD:Cell (Figure 6C). Regardless of diet, STZ itself had a marked impact on microbiota composition but did not markedly affect the overall extent to which inulin enrichment of CDD altered microbiota composition within this context, although both cellulose and inulin modestly blunted the impact of STZ treatment on microbiota composition (Figure 6D). Assessment of microbiota by Faith’s phylogenic diversity did not detect significant impacts of STZ but revealed a modest increase in alpha diversity in CDD:Cell fed mice after STZ treatment (Figure 6E). A common feature of microbiotas associated with inflammatory disease states, including obesity, is an increase in the phylogenic ratio of Firmicutes to Bacteroidetes. STZ itself induced such an increase in this ratio in mice fed CDD and CDD:Cell but not CDD:Inul (Figure 6F and G). To assess how fiber impacted STZ-induced changes in microbiota composition at the genus level we used linear discriminant analysis effect size (LefSe) analysis. This analysis revealed that although STZ induced some changes in microbiota composition irrespective of diet, for example an increase in Allobuculum and Bifidobacterium, other STZ-induced changes were uniquely present or absent in mice fed the inulin-enriched diet (Figure 7). Specifically, STZ induced Akkermansia only in inulin-fed mice (Figure 7A), reminiscent of findings that this taxa contributes to inulin’s amelioration of glycemic control in T2D.8 Moreover, LEfSe revealed a stark STZ-induced increase in the genera Enterococcus in mice fed CDD and CDD:Cell but was absent in STZ-treated mice fed CDD:Inul (Figure 7B). Culture-based quantification confirmed that CDD:Inul inhibited STZ-induced expansion of pathobiont Enterococcus, which might possibly promote inflammation and consequently insulin resistance in diabetic mice (Figure 7C). Last, we measured total levels of bacteria adherent to intestinal tissue by quantitative polymerase chain reaction (qPCR) and observed that STZ induced an increase in this parameter, which was not observed in mice fed CDD:Inul (Figure 7D). Together, these results indicate that STZ drives seemingly detrimental changes in gut microbiota that are blunted by inulin.

Figure 6.

Enrichment of diet with inulin ameliorated STZ-induced dysbiosis. (A) Fecal DNA from mice (n = 5) before and after STZ treatment was extracted to measure total bacterial number by qPCR. (B–G) Fecal microbiota composition was analyzed by 16S RNA sequencing; global composition was expressed by unweighted UniFrac principal component analysis (B); principal component analysis of the Unifrac distance (C and D); alpha diversity was analyzed by Faith’s phylogenetic diversity (E); relative abundance of bacteria at the phylum level (F) and the ratio of Firmicute to Bacteroidetes were calculated (G).

Figure 7.

Enrichment of diet with inulin altered gut microbiota composition. (A) LEfSe was used to display differences in relative abundance of genus in feces of mice between before and after STZ treatment. (B–D) Percentage of Enterococcus was calculated (B). Enterococcus spp. were analyzed by selective cultural plate (C). Relative level of intestinal adherent bacteria was analyzed by qPCR (D).

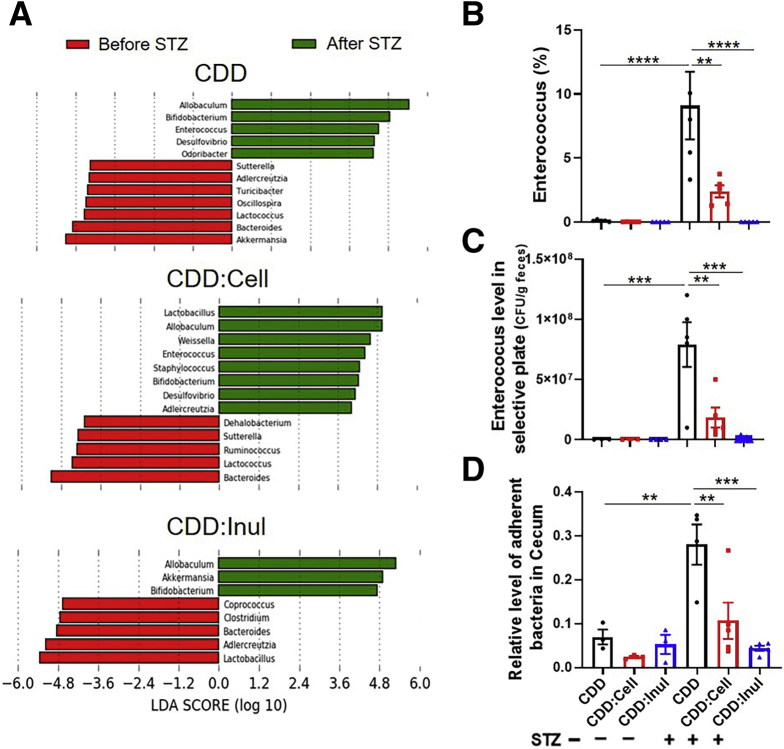

Inulin’s Protection Against STZ-Induced Diabetes Is Microbiota-Dependent

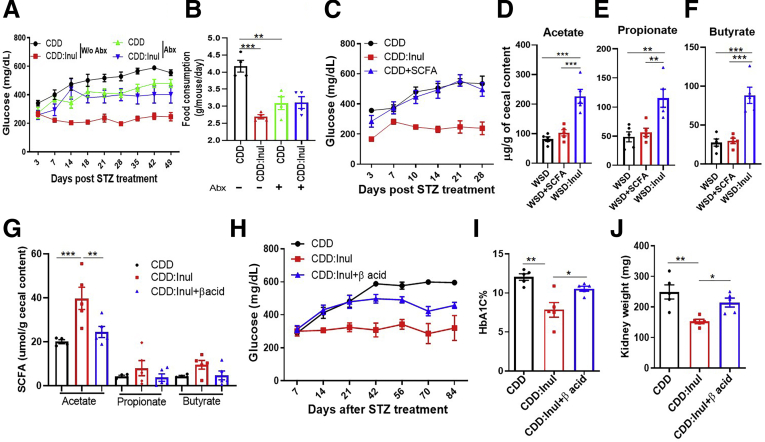

Inducing dysglycemia with WSD and preventing it with inulin require presence of gut microbiota.11 Hence, we investigated the extent to which gut microbiota played a similar role in STZ-induced diabetes. Before and after STZ treatment some mice received via drinking water a mixture of ampicillin, neomycin, vancomycin, and metronidazole previously shown to broadly suppress gut bacteria and eliminate inulin’s beneficial impacts in mice fed WSD.11,20 Such antibiotic treatment moderately reduced the severity of STZ-induced diabetes and also eliminated the near complete protection provided by inulin as assessed by dysglycemia and its associated parameters such as hyperphagia (Figure 8A and B). These results suggest that gut bacteria may play a role in promoting STZ-induced dysglycemia and, more unequivocally, indicate that microbiota are needed for inulin’s protection in this model.

Figure 8.

Beneficial impacts of inulin on STZ-induced diabetes were eliminated by antibiotics and reduced by fermentation blockade. (A and B) Mice (n = 5) were treated with CDD or CDD:Inul with or without antibiotic cocktail including ampicillin, neomycin, vancomycin, and metronidazole, glucose was monitored after STZ treatment (A), and food intake was measured (B). (C) Mice were fed with CDD or CDD:Inul diets with or without SFCA supplemented in drinking water and then treated with STZ to induce T1D; glucose was measured. (D-F) SCFA was measured in cecum content of mice fed a WSD, WSD enriched with inulin, or WSD and drinking water containing a mixture of sodium acetate, butyrate, and propionate. (G–J) C57BL/6 mice were given drinking water containing vehicle or 40 ppm of β acid during diet treatment. After 1 week, these mice were euthanized to collect cecum for measuring the level of SCFA or were subjected for treatment with STZ. Acetate, propionate, and butyrate were measured at 1 week of β-acid treatment (G). Glucose was monitored after STZ treatment (H), HbA1c (I), and kidney weight (J) was measured at end of experiment. Abx, antibiotics.

A frequently cited reason for why dietary fiber might improve glycemic control is that chemical products of its fermentation, namely SCFA, promote insulin sensitivity. We sought to test this possibility in STZ-treated mice by administering a mixture of SCFA via drinking water. This approach did not ameliorate STZ-induced hyperglycemia (Figure 8C). On the one hand, such lack of efficacy may reflect that orally administered SCFA are largely absorbed in the small intestine and thus did not elevate SCFA levels in the cecum/colon (Figure 8D–F). Yet on the other hand, that this mode of SCFA administration promotes development of regulatory T cells21 argues against such SCFA-elicited cells being sufficient to suppress STZ-induced diabetes. To investigate whether fermentation of inulin into SCFA in the large intestine was necessary for protection against STZ-induced diabetes, mice were administered drinking water supplemented with hops β-acids, which are very potent inhibitors of fermentation,22 thus preventing inulin-induced increases of colon SCFA without preventing increases in microbiota density.11 We observed a similar pattern of results in that enriching CDD with inulin resulted in marked increases in cecal SCFA, namely acetate, propionate, and butyrate, that were abolished by hops β-acids (Figure 8G). Such blockade of fermentation reduced but did not eliminate the ability of inulin to ameliorate hyperglycemia, elevations in HbA1c, and kidney hypertrophy in STZ-treated mice (Figure 8H–J). Together, these results indicate an important role for fermentation of inulin in mediating protection against STZ-induced diabetes but suggest that additional mechanisms are also important.

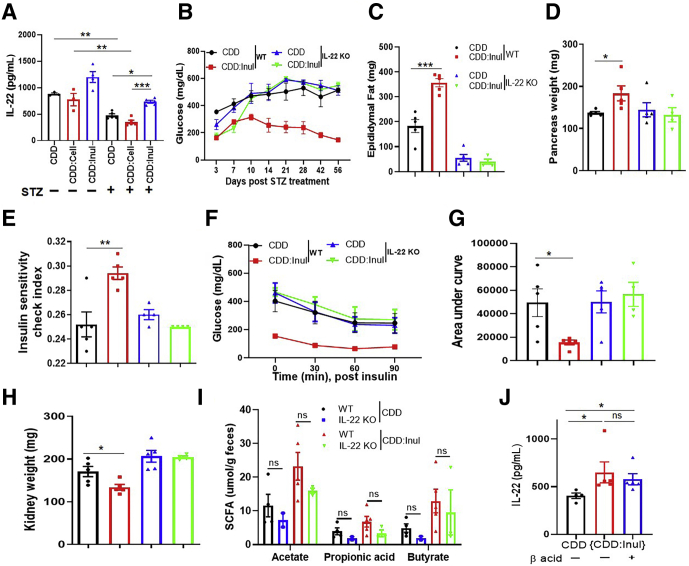

IL22 Is Necessary for and Partially Recapitulates Inulin’s Protection Against STZ-Induced Diabetes

Enrichment of WSD with inulin increases intestinal innate lymphoid cell IL22 expression, which is necessary for its protection against metabolic syndrome.11 Therefore, we examined the extent to which IL22 might play a role in inulin’s protection against STZ-induced diabetes. In accord with this possibility, we observed that STZ resulted in reduced intestinal IL22 expression, which was partially restored by CDD:Inul (Figure 9A). Furthermore, the strong protection against all parameters of STZ-induced diabetes conferred by CDD:Inul was largely absent in IL22-/- mice (Figure 9B–H). Thus, inulin’s protection against STZ-induced diabetes is highly dependent on IL22. We next sought to investigate the relationship between IL22 and SCFA. First, we considered the hypothesis that IL22, which is known to induce expression of antimicrobial peptides, might influence levels of fermenting bacteria and thus impact inulin-induced SCFA levels. However, CDD:Inul similarly increased cecal SCFA in wild-type (WT) and IL22-/- mice (Figure 9I), arguing against this possibility. Conversely, blockade of SCFA production via hops β-acids did not reduce inulin-induced expression of IL22 (Figure 9J). These results indicate that IL22 and fermentation are both microbiota-dependent but yet independent of each other, consequences of adding inulin to diet that protect against STZ-induced diabetes.

Figure 9.

IL22 was necessary for inulin’s prevention of STZ-induced diabetes. (A) Mice (n = 4–5), WT and IL22 KO, were fed CDD or CDD:Inul diets and treated with STZ to induce hyperglycemia. Expression of IL22 was analyzed by using ex vivo culture of colonic tissue of WT mice. (B) Blood glucose was monitored. (C and D) Epididymal fat (C) and the pancreas (D) were weighed at end of experiment. (E–G) Insulin sensitivity check index was calculated (E); insulin tolerance test (ITT) was conducted as mentioned (F); area under curve of ITT was calculated (G). (H) Kidney weight. (I) Feces was collected to measure SCFA. (J) Expression of IL22 was analyzed by using ex vivo culture of colonic tissue of WT mice fed with indicated diets with or without β-acid treatment.

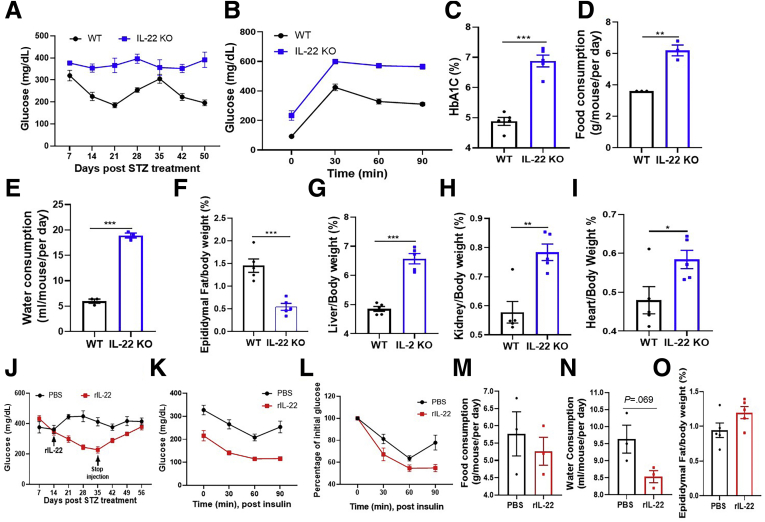

Next we examined whether IL22 expression might play a role in limiting the extent of diabetes in response to STZ in mice fed GBC, which is composed of ingredients that contain fermentable fiber, albeit likely at levels less than CDD:Inul. We compared the response of IL22-/- and closely related WT mice (offsprings of littermates) with STZ treatment. STZ-treated IL22-/- female mice exhibited more severe diabetes by all parameters measured including non-fasted and fasted blood glucose level, glucose tolerance, HbA1c, as well as food and water consumption (Figure 10A–E). Such exacerbated diabetes associated with reduced adiposity and exacerbated complications of diabetes including increased liver/kidney and cardiac mass (Figure 10F–I). These results suggest that analogous to mice fed inulin-enriched diets, IL22 expression helps limit severity of STZ diabetes in mice fed GBC. We next investigated whether supplementing basal IL22 production in mice fed GBC via administering exogenous IL22 might be sufficient to reduce severity of STZ-induced diabetes. Two weeks after STZ treatment, at which time hyperglycemia was established, mice were injected twice per week with vehicle (phosphate-buffered saline [PBS]) or recombinant IL22 for 3 weeks. IL22 treatment resulted in improved glycemic control as assessed by non-fasted and 5-hour fasted blood glucose (Figure 10J and K), which was associated with increased sensitivity to exogenously administered insulin (Figure 10K and L). Such benefits dissipated over the subsequent 3 weeks after cessation of IL22 treatment, suggesting that IL22 impacted the diabetic state rather than reversed STZ-induced injury (Figure 10J–O). Together, these results indicate that IL22 contributes to and can partially recapitulate fermentable fiber’s protection against STZ-induced diabetes.

Figure 10.

Use of recombinant IL22 to treat STZ-induced diabetes. (A) C57BL/6 WT and IL22 KO female mice (n = 5) fed with grain-based chow diet were treated with STZ; the glucose levels were measured until 50 days after STZ treatment. (B) Glucose tolerance test; (C) HbA1c level. (D and E) Food and water consumption. (F–I) Percentage of epididymal fat (F), liver (G), kidney (H), and heart (I) to body weight. (J–O) 2 weeks after STZ treatment, diabetic mice were injected IP with PBS or recombinant IL22 (rIL-22) 2 times every week until 35 days; these mice were euthanized at 56 days after STZ treatment. (J) Glucose was monitored. (K and L) Insulin tolerance test at day 35 after STZ treatment (K) and percentage to initial glucose after insulin injection were calculated (L). (M and N) Food (M) and water (N) consumption were measured 1 week before mice euthanasia. (O) Ratio of epididymal fat to body weight was calculated.

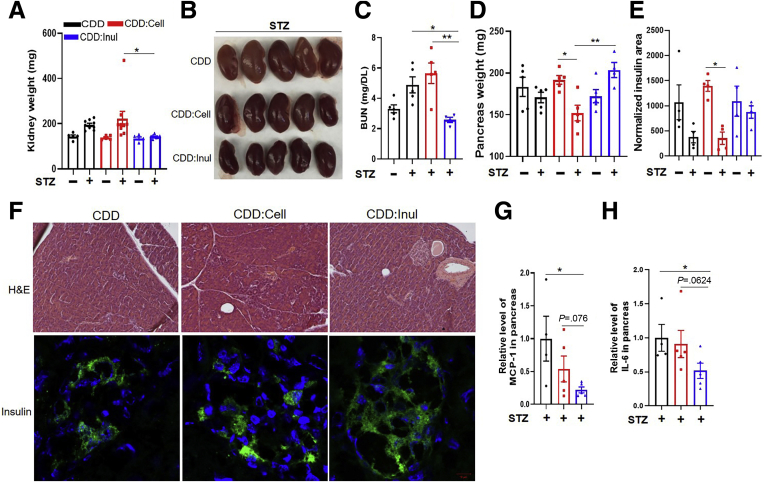

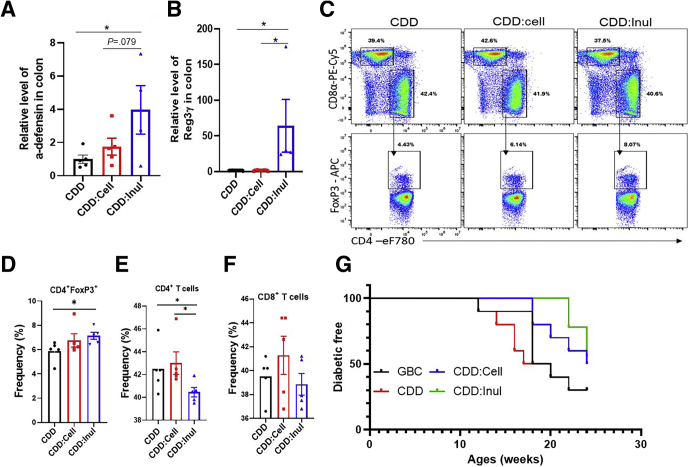

Last, we began to explore possible mechanisms by which IL22 and SCFA might mediate inulin’s protection against STZ-induced diabetes. The microbiota dependence of such protection and the fact that IL22 is known to induce epithelial production of antimicrobial peptides23 suggest that inulin might help manage microbiota by such a mechanism. In accord with this possibility, mice fed CDD:Inul exhibited elevated intestinal expression of Reg3 γ and α-defensin (Figure 11A and B). Regarding how fermentation of inulin protected against STZ-induced diabetes, we reasoned that the apparent requirement that SCFA be generated in the distal gastrointestinal tract suggested a possible role in impacting immune responses in this compartment. Indeed, we observed that enriching CDD with inulin resulted in increased regulatory T cells and decreased effector CD4 T cells in the intestinal mesenteric lymph nodes (Figure 11C–F). We envisage that such impacts of inulin on innate and adaptive immunity would not only protect against STZ-induced diabetes but might confer this fiber with ability to ameliorate T1D induced by various underlying causes. To test this notion, we used the NOD model characterized by this mouse strain’s sporadic and rapid development of diabetes that occurs from 12 to 30 weeks of age in various studies. In accord with other studies, when they were fed GBC, 50% of NOD mice developed severe diabetes (glucose more than 599 g/dL) by 18 weeks of age. Diabetes development was significantly delayed by more than 4 weeks in NOD mice fed CDD:Inul but not CDD:Cell (Figure 11G), thus supporting the notion that fermentable fiber might generally protect against T1D.

Figure 11.

Inulin modulated gut immunity and delayed diabetes development in NOD mice. (A–F) C57BL/6 male mice (n = 4–5) were fed CDD, CDD:Cell, or CDD:Inul for 1 week before euthanasia. Colon reg3 γ and α-defensin expression was analyzed by quantitative real-time PCR (A and B). Intestinal mesenteric lymph node T-cell populations were assayed by flow cytometry. Representative flow cytometry plot of T cells (C). Percentage of CD4 T-regulatory cells (D), total CD4 (E), and CD8 (F) T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes. (G) NOD mice (n = 9–10) were fed with indicated diets, and diabetes development was monitored as defined by blood glucose greater than 250 mg/dL.

Discussion

The central finding reported herein is that nourishing intestinal microbiota via provision of the fermentable fiber inulin resulted in protection in 2 experimental models of T1D. Although this finding can be viewed as an extension of previous reports that fermentable fiber ameliorates T2D,11 marked distinctions in the underlying causes and presentation of these diseases make these observations quite surprising. Specifically, while fermentable fiber provides a benefit in T2D by ameliorating the central defining feature of this disease, namely insulin resistance, inulin’s protection against STZ-induced diabetes associated with preservation of pancreatic β cells, whose loss is the central pathogenic event in T1D.24 Furthermore, the beneficial impacts of fermentable fiber on glycemic control in T2D models are highly intertwined with mitigating other central features of metabolic syndrome, especially adiposity.25 In contrast, in the STZ model, consumption of inulin resulted in markedly improved glycemic control while maintaining body mass. This suggests that preservation of normoglycemia in the STZ model may be a relatively proximal consequence of consumption of fermentable fiber and, in any case, is clearly not dependent on reducing adiposity. That inulin protected against STZ-induced hyperglycemia while preserving body mass provides a readily appreciable health benefit in this disease model. Specifically, weight loss and accompanying reductions in blood glucose levels do not necessarily reflect improved health. Indeed, weight loss and resulting changes in glycemia can also be a consequence of various diseases, thus making it difficult to discern, especially in relatively short-term studies in mice, if a dietary intervention that lowered blood glucose was truly health-benefitting. In contrast, in the STZ-induced diabetes model, fiber not only improved diagnostic markers of disease but also clearly made the STZ-treated mice healthier in that it ameliorated overt clinical-type disease features such as excessive thirst/urination and wasting despite hyperphagia that often result in death if untreated.

Inulin’s prevention of β cell loss in the STZ model suggests potential to reduce development of T1D in scenarios wherein β cells are challenged by environmental stressors. Indeed, a growing list of environmental chemicals that humans encounter (eg, persistent organic pollutants) are reported to damage or destroy β cells and/or impede insulin secretion in model systems.26,27 Accordingly, persons with higher exposures to organic pollutants display lower insulin secretion after glucose challenge.28 Increased exposures to such chemicals mirror the steadily rising incidence of T1D in children.29,30 Although mechanisms by which fiber might protect β cells are unclear, that inulin’s protection against STZ-induced diabetes associated with and required IL22 suggests a potential role for regenerating islet III (Reg3) β and γ proteins, which are highly induced by IL22 and can prevent loss of β cells.31,32 Such a role for Reg3 proteins accords with recent appreciation that they can act as gut-derived hormones.33 Consequently, whether Reg3 proteins produced in response to IL22 in the intestine are transported to the pancreas and impact β cells therein warrants investigation.

The notion that IL22 has broad metabolic consequences comports with our previous finding that this cytokine is required for inulin’s protection against WSD-induced metabolic syndrome11 and findings by others that exogenously administered IL22 results in metabolic improvements in WSD-fed and leptin-deficient mice.34 The ability of IL22 to protect against hyperglycemia in T1D and T2D models reflects that despite their differences, there are some similarities in disease pathophysiology and consequently how inulin protects therein. Alterations in gut microbiota strongly associate with both T1D and T2D and may be an important determinant of disease development.35 Accordingly, in models of both, inulin’s protection against disease was fully eliminated by antibiotics, indicating a role for microbiota. Moreover, both STZ- and WSD-induced hyperglycemia was itself partially ameliorated by antibiotics.36 Considering these observations, together with IL22’s ability to protect mucosal surfaces, including by driving expression of antimicrobial peptides, suggests that a portion of inulin’s ability to ameliorate diabetes may reflect its ability to help maintain a beneficial host-microbiota relationship, both by restoring microbiota density and by preventing detrimental changes in microbiota composition.

A stable beneficial host-microbiota relationship is proposed to protect against T2D by minimizing low-grade inflammation, which can promote insulin resistance.37 That the inulin-enriched diet decreased splenic neutrophils and increased sensitivity to insulin suggests that mitigating low-grade systemic inflammation, and consequently insulin resistance, may contribute to its protection in the STZ model. This notion fits with recent appreciation that the severity of T1D in humans is impacted by insulin sensitivity.38,39 In addition to directly impacting blood glucose levels, insulin’s ability to maintain glycemic control can help preserve β-cell function. Indeed, in early stages of diabetes, pancreatic β cells are not permanently damaged and can be rescued by removing or alleviating their stresses.40 Hence, inulin’s impact on insulin sensitivity may contribute to its ability to preserve pancreatic function. Specifically, we hypothesize that by limiting hyperglycemia, which can be directly toxic to β cells, inulin’s promotion of insulin signaling helps avoid the permanent destruction of these cells. Considering such a scenario in the context of microbiota suggests that dysbiosis observed in T1D patients might act as a trigger and/or exacerbating factor in disease development, perhaps by promoting low-grade inflammation, thus contributing to insulin resistance. Conversely, it suggests that reshaping gut microbiota by increased consumption of fermentable fiber in the early stage of T1D might increase insulin sensitivity and thereby suppress disease development. Importantly, such a protective mechanism could potentially ameliorate T1D that might otherwise be initiated by a wide degree of underlying causes.

The metabolic benefits of fermentable fiber are frequently attributed to their fermentation products, namely SCFA. That blockade of fermentation with hops β-acids reduced inulin’s protection against STZ-induced hyperglycemia indicates an important role for fermentation in mediating the beneficial effects of this in this T1D model. Yet, direct SCFA administration by itself did not provide a significant impact on STZ-induced diabetes, suggesting that SCFA alone are not sufficient to recapitulate inulin’s benefits or that their oral administration does not result in them reaching necessary sites of action, which we hypothesize are the cecum and colon. We initially hypothesized that colonic SCFA might abrogate STZ-induced hyperglycemia by promoting IL22 expression but found that inulin continued to induce IL22 irrespective of fermentation blockade. Moreover, we find that SCFA lack ability to induce IL22 in an ex vivo model (administration of mmol/L levels of SCFA to an ILC3 cell line did not by itself induce IL22 or enhance the amount of IL22 elicited by IL23). Conversely, inulin continued to increase levels of SCFA in IL22-deficient mice, thus indicating that IL22 and SCFA act independently to improve glycemic control in STZ-induced diabetes. The sporadic nature of diabetes development in the NOD model makes mechanistic studies more challenging. Nonetheless, we suspect that inulin’s dampening inflammation, and thus insulin resistance, may also play a role in delaying disease in NOD mice. In addition and/or alternatively, such dampening of inflammation might alter the nature or kinetics of the adaptive immune response that drives the destruction of β cells in this model. Inulin increased intestinal lymph node regulatory T cells, which previous studies indicate help stabilize host-microbiota homeostasis and suppress the T-cell mediated destruction of β cells.41,42

Although a long, albeit rarely deep, body of literature supports the notion that dietary fiber is generally health-promoting and protects against obesity and its associated disorders including T2D, the extent to which dietary fiber might provide a benefit in T1D is less clear. Although broad societal comparisons have suggested reduced consumption of fiber-rich foods to be associated with increased incidence of this disorder, careful intra-society observational studies have generally not consistently associated differences in fiber consumption with development of T1D.43, 44, 45 Yet, such studies suffer from a number of limitations including that most persons consumed far less fiber than recommended by most nutrition guidelines and did not distinguish types of fiber. Indeed, host metabolism and consequently impacts of insoluble fiber and soluble fiber are quite distinct. Indeed, although insoluble fiber provides bulk, which can promote intestinal motility and can have a variety of metabolic impacts, such fibers do not have the marked impacts on glycemic control induced by soluble fibers.11 Moreover, within these subtypes, distinct fibers can have markedly distinct impacts. For example, long-chain but not short-chain inulin reduced development of immune-mediated diabetes exhibited by NOD mice.42 Thus, we suggest that irrespective of the range of potential initiators of T1D, use of fermentable dietary fiber and/or IL22 may have application as an early intervention to ameliorate this disorder.

Mice, Diets, and Treatment

C57BL/6 WT mice were purchased from Jackson Laboratory (Bar Harbor, ME) or bred at Georgia State University. IL22 KO mice, generated by Genentech (South San Francisco, CA), were bred and housed at Georgia State University. Mice were fed with GBC (cat# 5001; LabDiet), purified CDDs (Supplementary Table 1; Research Diets, Inc), and housed at Georgia State University under approved animal protocols (IACUC # A17047). For inducing diabetic models, 5-week-old mice (or at indicated age) were fed with GBC or specified CDDs for 1 week and then intraperitoneally (IP) injected with 50 mg/kg STZ for 5 consecutive days as previously described.46 For antibiotic treatment, mice were fed with indicated CDDs and drinking water containing ampicillin (1 g/L), vancomycin (0.2 g/L), neomycin (1 g/L), and metronidazole (1 g/L) for 1 week before treatments of STZ. Such diets and water containing antibiotics were maintained until the end of experiment. Mice were treated with vehicle control (propylene glycol) or β-acid (40 ppm) in drinking water to inhibit the production of SCFA, or mice were placed on drinking water containing a mixture of SCFA (67.5 mmol/L sodium acetate, 40 mmol/L sodium butyrate, and 25.9 mmol/L sodium propionate) according to previously described21 and then treated with STZ to induce diabetes. For inulin treating experiment, CDD fed mice were treated with STZ; 2 weeks after STZ treatment these mice were switched to CDD:Inul. At the end of experiment, mice were fasted for 5 hours and then euthanized. Different organs, including body weight, pancreas, and adipose weight, were measured. NOD mice, 5 weeks old, were purchased from Jackson Laboratory and housed in our animal facilities under specific pathogen-free conditions. Blood glucose (non-fasted) was measured weekly until 24 weeks.

Five-Hour Fasting Blood Glucose Measurement and Insulin Sensitivity Check Index

Mice were provided with water without food for 5 hours in a clean cage; blood glucose level was measured by using a Nova Max Plus Glucose Meter and expressed in mg/dL. Insulin in the serum of fasted and non-fasted mice was measured by enzyme-linked immunosorbent assay according to the kit instruction (#EZRMI-13K, rat/mouse insulin ELISA kit; Millipore, Burlington, MA). Quantitative insulin sensitivity check index (QUICKI) values were calculated as follows: 1/(log[fasting insulin mU/mL] + log[fasting glucose mg/dL]).

Glucose and Insulin Tolerance Test

To conduct glucose tolerance test, mice were fasted for 5 hours, their weight and baseline blood glucose were measured by using a Nova Max plus Glucose meter, and then they were IP injected with 2 mg of glucose per gram of body weight. For insulin tolerance test, 5-hour fasted mice were IP injected with 0.5 U or 0.75 U insulin/kg body weight. The blood glucose levels were measured 30, 60, and 90 minutes after injection.

Measurement of Food and Water Consumption

One week before euthanasia (or at the indicated time points), mice with 4–5 mice per cage were placed in a clean cage with a known amount of food and water. The remaining food and water were measured daily to calculate the food and water consumption and divided by number of mice. These mice were measured 3–7 constitutive days to calculate the average of food and water consumption per mouse in one cage. Because of the availability and limitation of equipment, the evaporation of water and water lost by spillage into the cage are not taken into account.

HbA1c Measurement

HbA1c levels were measured in whole blood of non-fasted mice by a cut in the tail vein and using the quick test A1CNow+ 20 test-kits.

Measurement of Cholesterol and Triglycerides

Cholesterol and triglycerides levels in serum were measured using the Infinity Cholesterol Reagent and Infinity Triglyceride Reagent System (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA) according to manufacturer’s instructions, respectively. Briefly, 2 μl serum was mixed with 200 μL Triglyceride Reagent or Cholesterol Reagent and incubated for 5 minutes before being measured by a 96-well plate reader.

Measurement of SCFA

Cecal content was collected immediately after non-fasted mice were euthanized and then weighed before freezing. Levels of acetate, propionate, and butyrate in the samples were measured after extraction with ethyl acetate using Agilent 7890A gas chromatography (Santa Clara, CA) with a fused silica capillary column (Nukon SUPELCO No: 40369-03A, Bellefonte, PA) as described.47 Heptanoic acid is used as internal standard, and the results are presented as μmol/g or μg/g of cecal/fecal content.

RNA Extraction and Real-Time PCR

Total RNA was isolated from colon or pancreas using TRIzol (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA); the expression level of Reg3γ, α-defensin in colon, and MCP-1, IL6 in pancreas was analyzed by using quantitative real-time PCR according to the Biorad iScript One-Step RT-PCR Kit in a CFX96 apparatus (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with the following primers: Reg3 γ: TTCCTGTCCTCCATGATCAAA, CATCCACCTCTGTTGGGTTC; α-defensin: GGTGATCATCAGACCCCAGCATCAGT, AAGAGACTAAAACTGAGGAGCAGC; IL6: GTGGCTAAGGACCAAGACC, GGTTTGCCGAGTAGACCTCA; MCP-1: GCTGGAGCATCCACGTGTT, TGGGATCATCTTGCTGGTGAA; 36B4: TCCAGGCTTTGGGCATCA, CTTTATTCAGCTGCACATCACTCAGA. Differences in transcript levels were quantified by normalization of each amplicon to housekeeping gene 36B4.

H&E Staining and Immunofluorescence Staining

For histology analysis, mouse pancreas was fixed in 10% phosphate-buffered formalin for at least 1 week before transfer into 70% ethanol and embedded in paraffin for histologic examination by H&E staining. To perform immunofluorescence staining, mouse pancreas was embedded in OCT after euthanasia. The tissues were sectioned at 4-μm thickness and fixed with 4% formaldehyde for 30 minutes at room temperature. After washing with PBS, the tissue was permeabilized in cold methanol for 5 minutes. The section was blocked with blocking buffer (Zymed Laboratories Inc, San Diego, CA) before incubation with anti-insulin antibody (Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA; catalog #3014) overnight at 4°C. The section was then stained with fluorescein isothiocyanate–labeled Secondary Fluorescent Antibody. After washing in PBS, the tissues were counterstained with mounting medium containing DAPI. Pancreatic islets were evaluated using ImageJ software (National Institutes of Health, Bethesda, MD).

Flow Cytometry Analysis

Cell suspension was isolated from spleen and intestinal mesenteric lymph nodes of mice fed with CDD, CDD:Cell, or CDD:Inul for 1 week by gently dissociating through a 70-μm cell strainer using the plunger of a 5-mL syringe. Fluorescence dye labeled antibodies specific for CD45-PerCP (30-F11), CD11b-eF450 (M1/70), CD11c-APC (N418), MHCII-FITC (M5-114.15.2), Ly6G-APC-Cy-7 (1A8), CD4-APC-Cy7 (L4T3), CD8-PE-Cy5.5 (53-6.7), FoxP3-APC (FJK-16S) were purchased from BioLegend (San Diego, CA), Becton Dickinson (Franklin Lakes, NJ), and eBioscience (San Diego, CA). Fc-Block (2.4G2) was purchased from BioXCel Therapeutics (New Haven, CT). Dead cells were stained using the fixable Aqua dead cell staining kit (Invitrogen). For analysis of antigen-presenting cells (macrophages, DCs) and neutrophil in the spleen, splenocytes were stained on ice for 20 minutes with antibodies specific for CD45, MHCII, CD11b, CD11c, and Ly6G. For analysis of T cells in mesenteric lymph nodes, the cells were restimulated with stimulation cocktail (plus protein transported inhibitor) for 3 hours. Restimulated cells were fixed and permeabilized using Fix/Perm buffer set (eBioscience) and intracellular staining with antibodies specific for CD4, CD8, FoxP3, in FoxP3 staining buffer (eBioscience). Multiparameter analysis was performed on the CytoFlex (Beckman Coulter, Brea, CA) and analyzed with FlowJo software (TreeStar, Ashland, OR).

Enzyme-Linked Immunosorbent Assay

One centimeter of colons closest to the cecum was cut open longitudinally and washed with ice cold PBS for multiple times to remove remaining feces. Then the tissues were cultured in 24-well flat bottom culture plates in RPMI 1640 medium supplemented with penicillin and streptomycin, 2% fetal bovine serum. After 24 hours, supernatant was collected and stored at –80°C. The concentration of IL22 in the supernatant was measured according to the ELISA kit provided by R&D Systems (Minneapolis, MN). The concentration of blood urea nitrogen in the serum was measured using the BUN ELISA kit (Invitrogen) according to its provided instructions.

Bacterial Quantification in Feces and in Cecum Tissue

To measure the total fecal bacterial load, total DNA was isolated from weighted feces using QIAamp DNA Stool Mini Kit (Qiagen, Hilden, Germany). DNA was then subjected to qPCR using QuantiFast SYBR Green PCR kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA) with universal 16S rRNA primers 8F: 5′-AGAGTTTGATCCTGGCTCAG-3′ and 338R: 5′-CTGCTGCCTCCCGTAGGAGT-3′ to measure total bacteria number. Results are expressed as bacteria number per mg of stool using a standard curve. To measure the adherent bacteria to the cecum tissue, the distal end of cecum was cut, the feces were flushed out, and cecum tissue was washed in PBS 3 times before storage in –80°C. Half milliliter of PBS was added into the cecum tissue to boil at 100°C for 10 minutes. After being centrifuged at 1200 rpm for 10 minutes, the supernatant was subjected to qPCR using universal 16S rRNA primers 8F and 338R to measure the bacteria to epithelial cells. Differences in the relative abundance of bacteria in cecum tissue were quantified by normalization of the housekeeping gene 18S rRNA.

Gut Microbiota Analysis by Using 16S Ribosomal RNA Gene Sequencing

The DNA was extracted from feces by using the QIAamp PowerFecal Pro DNA Kit, and 16S rRNA gene amplification was conducted according to the Illumina 16S Metagenomic Sequencing Library (San Diego, CA) preparation guide as described.48 Briefly, the extracted DNA was used to amplify the region V4 of 16S rRNA genes by the following forward and reverse primers: 515FB: 5′TCGTCGGCAGCGTCAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGTGYCAGCMGCCGCGGTAA-3′; 806RB: 5′GTCTCGTGGGCTCGGAGATGTGTATAAGAGACAGGGACTACNVGGGTWTCTAAT-3′. These 2 primers were designed with overhang Illumina adapters.

PCR products of each sample were purified with Ampure XP magnetic purification beads (Agencourt) and then run on the bioanalyzer high sensitivity chip to verify the size of the amplicon. A second PCR was performed to attach dual indices and Illumina sequencing adapters using Nextera XT Index kit. Products were then quantified before the DNA pool was generated from the purified products in equimolar ratios. The quantity of pooled products was measured before sequencing on the Illumina MiSeq sequencer (paired-end reads, 2 × 250 base pairs) at Georgia Institute of Technology Molecular Evolution Core (Atlanta, GA). Sequences were demultiplexed and quality filtered using Dada2 method49 with QIIME2 default parameters to detect and correct Illumina amplicon sequence data, and a table of Qiime 2 artifact was generated. A tree was next generated using the align-to-tree-mafft-fasttree command for phylogenetic diversity analyses, and alpha and beta diversity analyses were computed using the core-metrics-phylogenetic command. Principal coordinates analysis plots were used to assess the variation between experimental groups (beta diversity). For taxonomy analysis, features were assigned to operational taxonomic units with 99% threshold of pairwise identity to the Greengenes reference database 13_8.50 LEfSe was used to investigate bacterial members at genus level between groups. The sequencing data are deposited at SRA database under accession number PRJNA666190.

Measurement of Enterococcus in Selective Plate

The fresh feces were collected from mice fed with the indicated diets by using sterile boxes individually and weighed to prepare 100 mg/mL in PBS. The resuspended feces were homogenized for 30 seconds using a Mini-Beadbeater without the addition of beads. The Enterococcus species was counted by using serial dilution and plate counting with Enterococcus selective plate. The number of Enterococcus species in feces was expressed as colony-forming units/g feces.

Recombinant IL22 Treatment

Five-week-old C57BL/6 WT mice were IP injected with 50 mg/kg STZ for 5 consecutive days. These mice were IP injected with PBS or recombinant IL22 (20 μg/per mouse, provided by Genentech, Inc as murine Fc-IL-22) two times every week beginning 2 weeks after STZ treatment. Recombinant IL22 treatment was stopped at day 35 after STZ treatment. These mice were maintained on GBC until 56 days after STZ treatment before euthanasia.

Statistical Analyses

Statistical significances of results were analyzed by unpaired Student t test or analysis of variance. Differences between experimental groups were considered significant at ∗P ≤ .05, ∗∗P ≤ .01, ∗∗∗P ≤ .001, ∗∗∗∗P ≤ .0001, and ns, not significant.

CRediT Authorship Contributions

Jun Zou (Conceptualization: Lead; Data curation: Lead; Funding acquisition: Equal; Writing – review & editing: Equal)

Lavanya Reddivari (Data curation: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Zhenda Shi (Data curation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Shiyu Li (Data curation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting)

Yanling Wang (Data curation: Supporting)

Alexis Bretin (Data curation: Supporting)

Vu Ngo (Investigation: Supporting)

Michael Flythe (Methodology: Supporting; Resources: Supporting)

Michael Pelizzon (Conceptualization: Supporting; Resources: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Benoit Chassaing (Conceptualization: Supporting; Data curation: Supporting; Methodology: Supporting; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Andrew Gewirtz (Conceptualization: Supporting; Funding acquisition: Lead; Project administration: Equal; Writing – original draft: Lead; Writing – review & editing: Supporting)

Footnotes

Conflicts of interest The authors disclose no conflicts.

Funding Supported by National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants DK099071 (ATG) and DK083890 (ATG). J. Z. is supported by the American Diabetes Association (#1-19-JDF-077).

Supplementary Material

References

- 1.Costa F.R., Francozo M.C., de Oliveira G.G., Ignacio A., Castoldi A., Zamboni D.S., Ramos S.G., Camara N.O., de Zoete M.R., Palm N.W., Flavell R.A., Silva J.S., Carlos D. Gut microbiota translocation to the pancreatic lymph nodes triggers NOD2 activation and contributes to T1D onset. J Exp Med. 2016;213:1223–1239. doi: 10.1084/jem.20150744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Dehpour A.R., Samadian T., Rassaee N. Diabetic rats show more resistance to neuromuscular blockade induced by aminoglycoside antibiotics. Gen Pharmacol. 1993;24:1415–1418. doi: 10.1016/0306-3623(93)90428-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Leite J.A., Pessenda G., Guerra-Gomes I.C., de Santana A.K.M., Andre Pereira C., Ribeiro Campos Costa F., Ramos S.G., Simoes Zamboni D., Caetano Faria A.M., Candido de Almeida D., Olsen Saraiva Camara N., Tostes R.C., Santana Silva J., Carlos D. The DNA densor AIM2 protects against streptozotocin-induced type 1 diabetes by regulating intestinal homeostasis via the IL-18 pathway. Cells. 2020;9:959. doi: 10.3390/cells9040959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kemppainen K.M., Ardissone A.N., Davis-Richardson A.G., Fagen J.R., Gano K.A., Leon-Novelo L.G., Vehik K., Casella G., Simell O., Ziegler A.G., Rewers M.J., Lernmark A., Hagopian W., She J.X., Krischer J.P., Akolkar B., Schatz D.A., Atkinson M.A., Triplett E.W., Group T.S. Early childhood gut microbiomes show strong geographic differences among subjects at high risk for type 1 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2015;38:329–332. doi: 10.2337/dc14-0850. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kostic A.D., Gevers D., Siljander H., Vatanen T., Hyotylainen T., Hamalainen A.M., Peet A., Tillmann V., Poho P., Mattila I., Lahdesmaki H., Franzosa E.A., Vaarala O., de Goffau M., Harmsen H., Ilonen J., Virtanen S.M., Clish C.B., Oresic M., Huttenhower C., Knip M., Group D.S., Xavier R.J. The dynamics of the human infant gut microbiome in development and in progression toward type 1 diabetes. Cell Host Microbe. 2015;17:260–273. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2015.01.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fenneman A.C., Rampanelli E., Yin Y.S., Ames J., Blaser M.J., Fliers E., Nieuwdorp M. Gut microbiota and metabolites in the pathogenesis of endocrine disease. Biochem Soc Trans. 2020;48:915–931. doi: 10.1042/BST20190686. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Vaarala O., Atkinson M.A., Neu J. The “perfect storm” for type 1 diabetes: the complex interplay between intestinal microbiota, gut permeability, and mucosal immunity. Diabetes. 2008;57:2555–2562. doi: 10.2337/db08-0331. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Catry E., Bindels L.B., Tailleux A., Lestavel S., Neyrinck A.M., Goossens J.F., Lobysheva I., Plovier H., Essaghir A., Demoulin J.B., Bouzin C., Pachikian B.D., Cani P.D., Staels B., Dessy C., Delzenne N.M. Targeting the gut microbiota with inulin-type fructans: preclinical demonstration of a novel approach in the management of endothelial dysfunction. Gut. 2018;67:271–283. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2016-313316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hiel S., Gianfrancesco M.A., Rodriguez J., Portheault D., Leyrolle Q., Bindels L.B., Gomes da Silveira Cauduro C., Mulders M., Zamariola G., Azzi A.S., Kalala G., Pachikian B.D., Amadieu C., Neyrinck A.M., Loumaye A., Cani P.D., Lanthier N., Trefois P., Klein O., Luminet O., Bindelle J., Paquot N., Cnop M., Thissen J.P., Delzenne N.M. Link between gut microbiota and health outcomes in inulin-treated obese patients: lessons from the Food4Gut multicenter randomized placebo-controlled trial. Clin Nutr. 2020 doi: 10.1016/j.clnu.2020.04.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Schroeder B.O., Birchenough G.M.H., Stahlman M., Arike L., Johansson M.E.V., Hansson G.C., Backhed F. Bifidobacteria or fiber protects against diet-induced microbiota-mediated colonic mucus deterioration. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:27–40 e7. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.11.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Zou J., Chassaing B., Singh V., Pellizzon M., Ricci M., Fythe M.D., Kumar M.V., Gewirtz A.T. Fiber-mediated nourishment of gut microbiota protects against diet-induced obesity by restoring IL-22-mediated colonic health. Cell Host Microbe. 2018;23:41–53 e4. doi: 10.1016/j.chom.2017.11.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Dahl W.J., Stewart M.L. Position of the Academy of Nutrition and Dietetics: health implications of dietary fiber. J Acad Nutr Diet. 2015;115:1861–1870. doi: 10.1016/j.jand.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khawandanah J. Double or hybrid diabetes: a systematic review on disease prevalence, characteristics and risk factors. Nutr Diabetes. 2019;9:33. doi: 10.1038/s41387-019-0101-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wise A., Gilburt D.J. The variability of dietary fibre in laboratory animal diets and its relevance to the control of experimental conditions. Food Cosmet Toxicol. 1980;18:643–648. doi: 10.1016/s0015-6264(80)80013-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Pellizzon M. Choice of laboratory animal diet influences intestinal health. Lab Anim (NY) 2016;45:238–239. doi: 10.1038/laban.1014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Desai M.S., Seekatz A.M., Koropatkin N.M., Kamada N., Hickey C.A., Wolter M., Pudlo N.A., Kitamoto S., Terrapon N., Muller A., Young V.B., Henrissat B., Wilmes P., Stappenbeck T.S., Nunez G., Martens E.C. A dietary fiber-deprived gut microbiota degrades the colonic mucus barrier and enhances pathogen susceptibility. Cell. 2016;167:1339–1353 e21. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.10.043. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gaines S., van Praagh J.B., Williamson A.J., Jacobson R.A., Hyoju S., Zaborin A., Mao J., Koo H.Y., Alpert L., Bissonnette M., Weichselbaum R., Gilbert J., Chang E., Hyman N., Zaborina O., Shogan B.D., Alverdy J.C. Western diet promotes intestinal colonization by collagenolytic microbes and promotes tumor formation after colorectal surgery. Gastroenterology. 2020;158:958–970 e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.10.020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chassaing B., Miles-Brown J., Pellizzon M., Ulman E., Ricci M., Zhang L., Patterson A.D., Vijay-Kumar M., Gewirtz A.T. Lack of soluble fiber drives diet-induced adiposity in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2015;309:G528–G541. doi: 10.1152/ajpgi.00172.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lenzen S. The mechanisms of alloxan- and streptozotocin-induced diabetes. Diabetologia. 2008;51:216–226. doi: 10.1007/s00125-007-0886-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Adeshirlarijaney A., Zou J., Tran H.Q., Chassaing B., Gewirtz A.T. Amelioration of metabolic syndrome by metformin associates with reduced indices of low-grade inflammation independently of the gut microbiota. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2019;317:E1121–E1130. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00245.2019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Smith P.M., Howitt M.R., Panikov N., Michaud M., Gallini C.A., Bohlooly Y.M., Glickman J.N., Garrett W.S. The microbial metabolites, short-chain fatty acids, regulate colonic Treg cell homeostasis. Science. 2013;341:569–573. doi: 10.1126/science.1241165. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Flythe M.D., Kagan I.A., Wang Y., Narvaez N. Hops (Humulus lupulus L.) bitter acids: modulation of rumen fermentation and potential as an alternative growth promoter. Front Vet Sci. 2017;4:131. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2017.00131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Kolls J.K., McCray P.B., Jr., Chan Y.R. Cytokine-mediated regulation of antimicrobial proteins. Nat Rev Immunol. 2008;8:829–835. doi: 10.1038/nri2433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Eizirik D.L., Mandrup-Poulsen T. A choice of death: the signal-transduction of immune-mediated beta-cell apoptosis. Diabetologia. 2001;44:2115–2133. doi: 10.1007/s001250100021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Papathanasopoulos A., Camilleri M. Dietary fiber supplements: effects in obesity and metabolic syndrome and relationship to gastrointestinal functions. Gastroenterology. 2010;138:65–72 e1–e2. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.11.045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fabricio G., Malta A., Chango A., De Freitas Mathias P.C. Environmental contaminants and pancreatic beta-cells. J Clin Res Pediatr Endocrinol. 2016;8:257–263. doi: 10.4274/jcrpe.2812. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Longnecker M.P., Daniels J.L. Environmental contaminants as etiologic factors for diabetes. Environ Health Perspect. 2001;109(Suppl 6):871–876. doi: 10.1289/ehp.01109s6871. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lee Y.M., Ha C.M., Kim S.A., Thoudam T., Yoon Y.R., Kim D.J., Kim H.C., Moon H.B., Park S., Lee I.K., Lee D.H. Low-dose persistent organic pollutants impair insulin secretory function of pancreatic beta-cells: human and in vitro evidence. Diabetes. 2017;66:2669–2680. doi: 10.2337/db17-0188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bonini M.G., Sargis R.M. Environmental toxicant exposures and type 2 diabetes mellitus: two interrelated public health problems on the rise. Curr Opin Toxicol. 2018;7:52–59. doi: 10.1016/j.cotox.2017.09.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Rewers M., Zimmet P. The rising tide of childhood type 1 diabetes: what is the elusive environmental trigger? Lancet. 2004;364:1645–1647. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(04)17368-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Hou W.R., Xie S.N., Wang H.J., Su Y.Y., Lu J.L., Li L.L., Zhang S.S., Xiang M. Intramuscular delivery of a naked DNA plasmid encoding proinsulin and pancreatic regenerating III protein ameliorates type 1 diabetes mellitus. Pharmacol Res. 2011;63:320–327. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2010.12.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Xiong X., Wang X., Li B., Chowdhury S., Lu Y., Srikant C.B., Ning G., Liu J.L. Pancreatic islet-specific overexpression of Reg3beta protein induced the expression of pro-islet genes and protected the mice against streptozotocin-induced diabetes mellitus. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2011;300:E669–E680. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00600.2010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Shin J.H., Seeley R.J. Reg3 proteins as gut hormones? Endocrinology. 2019;160:1506–1514. doi: 10.1210/en.2019-00073. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Wang X., Ota N., Manzanillo P., Kates L., Zavala-Solorio J., Eidenschenk C., Zhang J., Lesch J., Lee W.P., Ross J., Diehl L., van Bruggen N., Kolumam G., Ouyang W. Interleukin-22 alleviates metabolic disorders and restores mucosal immunity in diabetes. Nature. 2014;514:237–241. doi: 10.1038/nature13564. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Tai N., Wong F.S., Wen L. The role of gut microbiota in the development of type 1, type 2 diabetes mellitus and obesity. Rev Endocr Metab Disord. 2015;16:55–65. doi: 10.1007/s11154-015-9309-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran H.Q., Bretin A., Adeshirlarijaney A., Yeoh B.S., Vijay-Kumar M., Zou J., Denning T.L., Chassaing B., Gewirtz A.T. “Western diet”-induced adipose inflammation requires a complex gut microbiota. Cell Mol Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2020;9:313–333. doi: 10.1016/j.jcmgh.2019.09.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Harsch I.A., Konturek P.C. The role of gut microbiota in obesity and type 2 and type 1 diabetes mellitus: new insights into “old” diseases. Med Sci (Basel) 2018;6:32. doi: 10.3390/medsci6020032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Glastras S.J., Chen H., Teh R., McGrath R.T., Chen J., Pollock C.A., Wong M.G., Saad S. Mouse models of diabetes, obesity and related kidney disease. PLoS One. 2016;11 doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0162131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kaul K., Apostolopoulou M., Roden M. Insulin resistance in type 1 diabetes mellitus. Metabolism. 2015;64:1629–1639. doi: 10.1016/j.metabol.2015.09.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Taylor R., Al-Mrabeh A., Zhyzhneuskaya S., Peters C., Barnes A.C., Aribisala B.S., Hollingsworth K.G., Mathers J.C., Sattar N., Lean M.E.J. Remission of human type 2 diabetes requires decrease in liver and pancreas fat content but is dependent upon capacity for beta cell recovery. Cell Metab. 2018;28:667. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2018.08.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Ho J., Nicolucci A.C., Virtanen H., Schick A., Meddings J., Reimer R.A., Huang C. Effect of prebiotic on microbiota, intestinal permeability, and glycemic control in children with type 1 diabetes. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2019;104:4427–4440. doi: 10.1210/jc.2019-00481. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen K., Chen H., Faas M.M., de Haan B.J., Li J., Xiao P., Zhang H., Diana J., de Vos P., Sun J. Specific inulin-type fructan fibers protect against autoimmune diabetes by modulating gut immunity, barrier function, and microbiota homeostasis. Mol Nutr Food Res. 2017;61(8) doi: 10.1002/mnfr.201601006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ahola A.J., Harjutsalo V., Forsblom C., Saraheimo M., Groop P.H., Finnish Diabetic Nephropathy S. Associations of dietary macronutrient and fibre intake with glycaemia in individuals with type 1 diabetes. Diabet Med. 2019;36:1391–1398. doi: 10.1111/dme.13863. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Beyerlein A., Liu X., Uusitalo U.M., Harsunen M., Norris J.M., Foterek K., Virtanen S.M., Rewers M.J., She J.X., Simell O., Lernmark A., Hagopian W., Akolkar B., Ziegler A.G., Krischer J.P., Hummel S., Ts group. Dietary intake of soluble fiber and risk of islet autoimmunity by 5 y of age: results from the TEDDY study. Am J Clin Nutr. 2015;102:345–352. doi: 10.3945/ajcn.115.108159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Hakola L., Miettinen M.E., Syrjala E., Akerlund M., Takkinen H.M., Korhonen T.E., Ahonen S., Ilonen J., Toppari J., Veijola R., Nevalainen J., Knip M., Virtanen S.M. Association of cereal, gluten, and dietary fiber intake with islet autoimmunity and type 1 diabetes. JAMA Pediatr. 2019;173:953–960. doi: 10.1001/jamapediatrics.2019.2564. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Furman B.L. Streptozotocin-induced diabetic models in mice and rats. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2015;70 doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0547s70. 5.47.1–5.47.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Cantu-Jungles T.M., Ruthes A.C., El-Hindawy M., Moreno R.B., Zhang X., Cordeiro L.M.C., Hamaker B.R., Iacomini M. In vitro fermentation of Cookeina speciosa glucans stimulates the growth of the butyrogenic Clostridium cluster XIVa in a targeted way. Carbohydr Polym. 2018;183:219–229. doi: 10.1016/j.carbpol.2017.12.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zou J., Zhao X., Shi Z., Zhang Z., Vijay-Kumar M., Chassaing B., Gewirtz A.T. Critical role of innate immunity to flagellin in absence of adaptive immunity. J Infect Dis. 2021;223:1478–1487. doi: 10.1093/infdis/jiaa521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Callahan B.J., McMurdie P.J., Rosen M.J., Han A.W., Johnson A.J., Holmes S.P. DADA2: high-resolution sample inference from Illumina amplicon data. Nat Methods. 2016;13:581–583. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.McDonald D., Price M.N., Goodrich J., Nawrocki E.P., DeSantis T.Z., Probst A., Andersen G.L., Knight R., Hugenholtz P. An improved Greengenes taxonomy with explicit ranks for ecological and evolutionary analyses of bacteria and archaea. ISME J. 2012;6:610–618. doi: 10.1038/ismej.2011.139. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.