Abstract

Background

Candida glabrata is the second leading fungal pathogen causing candidaemia and invasive candidiasis in Europe. This yeast is recognized for its rapid ability to acquire antifungal drug resistance.

Objectives

We systematically evaluated 176 C. glabrata isolates submitted to the German National Reference Center for Invasive Fungal Infections (NRZMyk) between 2015 and 2019 with regard to echinocandin and fluconazole susceptibility.

Methods

Susceptibility testing was performed using a reference protocol (EUCAST) and a range of commercial assays. Hot spot regions of the echinocandin target FKS genes were sequenced using Sanger sequencing.

Results

In total, 84 of 176 isolates were initially classified as anidulafungin-resistant based on EUCAST testing. Of those, 71 harboured mutations in the glucan synthase encoding FKS genes (13% in FKS1, 87% in FKS2). Significant differences in anidulafungin MICs were found between distinct mutation sites. 11 FKS wild-type (WT) isolates initially classified as resistant exhibited anidulafungin MICs fluctuating around the interpretation breakpoint upon re-testing with multiple assays. Two FKS WT isolates consistently showed high anidulafungin MICs and thus must be considered resistant despite the absence of target gene mutations. Over one-third of echinocandin-resistant strains displayed concomitant fluconazole resistance. Of those, isolates linked to bloodstream infection carrying a change at Ser-663 were associated with adverse clinical outcome.

Conclusions

Resistant C. glabrata strains are emerging in Germany. Phenotypic echinocandin testing can result in misclassification of susceptible strains. FKS genotyping aids in detecting these strains, however, echinocandin resistance may occur despite a wild-type FKS genotype.

Introduction

Candida species are a leading cause of hospital-acquired infections.1–3 A diverse spectrum of immunocompromised patients ranging from neonates to patients receiving organ transplants or suffering from malignancies are considered at risk.4–7

Within the phylogenetically heterogenous Candida genus, Candida albicans is the most frequently isolated species, followed by Candida glabrata as the second leading pathogen causing bloodstream infection in Europe.8–11

Currently, the incidence of invasive Candida infections in ICU is estimated to range between 2.1 and 6.7 per 1000 admissions and candidaemia is recognized as the fourth most common cause of bloodstream infection worldwide.9,10 In Germany, the overall Candida species mortality of ICU mono-microbial bloodstream infection is 25.2% (P < 0.001).12 Notably, non- albicans Candida species (27.1%; P = 0.001) seem to confer a slightly higher mortality than C. albicans (24.6%, P < 0.001), which may be linked to a higher degree of antifungal drug resistance.12 In addition, a significant proportion of candidaemia cases occur outside the ICU. Thus, there is an estimated annual burden of 2000–12 000 cases of invasive candidiasis in Germany per year.7

Unlike C. albicans, which rarely develops antifungal drug resistance and is primarily susceptible to azole and echinocandin antifungals, C. glabrata shows an inherently reduced susceptibility to fluconazole. In addition, a significant proportion of clinical isolates show bona fide resistance to fluconazole.13–15

Since the introduction of echinocandins as first-line antifungal treatment for most cases of invasive candidiasis, the emergence of echinocandin resistance has also been observed in C. glabrata. Echinocandins target an essential element of the fungal cell wall by inhibition of the β-1,3-d-glucan synthase, which results in a fungicidal effect on Candida spp.16,17 Unlike C. albicans, C. glabrata harbours two FKS genes, FKS1 and FKS2, which are considered functionally redundant.18,19 Echinocandin resistance is mainly conferred by point mutations leading to amino acid substitutions within the two hot spots (HS) of the enzyme’s catalytic subunits encoded by FKS1 and FKS2, which result in a substantial reduction of echinocandin affinity for its target enzyme.20,21 The haploid genome of C. glabrata as well as alterations within the DNA mismatch repair system contribute to rapid emergence of resistance during therapy.22,23 Studies have assessed the incidence of FKS-mutated C. glabrata strains ranging between 2%–18%.24–27

Due to these developments, antifungal susceptibility testing has become increasingly important. Phenotypic resistance testing is conducted by reference broth microdilution according to EUCAST or CLSI protocols.28,29 In routine daily use, commercial systems such as microdilution trays, semi-automated testing systems or agar gradient diffusion (AGD) tests facilitate antifungal susceptibility testing.30–33 However, the prolonged duration of all assays (24–48 h) and a recently observed overlap of wild-type and FKS-mutated populations limit the value of in vitro susceptibility testing.34–36 Due to these problems, some authors have suggested that molecular resistance testing should be performed to detect echinocandin resistance based on the presence of FKS mutations. Molecular analysis seems to predict therapeutic failure more precisely than phenotypic testing.26,34,37

In this study, we assessed the current situation of phenotypic and genotypic echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata strains from Germany, focusing on differences in specific mutations and associated reduced susceptibility levels, the value of different testing methods and the emergence of MDR strains. Our data confirm the methodological problems of phenotypic testing. We showed that testing for micafungin is more discriminative than testing for anidulafungin with regard to detection of non-wild-type FKS isolates. However, we also identified two echinocandin-resistant isolates that do not harbour FKS mutations.

Material and methods

Strain collection

The National Reference Center for Invasive Fungal Infections (NRZMyk) serves as a national reference laboratory for Germany. In this study, 176 C. glabrata strains sent to the NRZMyk between 2015 and 2019 were analysed (see Table S1, available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online). Strains were submitted to NRZMyk by German healthcare facilities and laboratories for species confirmation and susceptibility testing. Apart from isolates 2016-275 and 2016-293, which are two distinct strains from a single patient harbouring different FKS mutations, only initial isolates for a patient were included in this study.

DNA extraction, species identification and FKS gene sequencing

DNA extraction and PCR was conducted as described previously.38 Species identification was accomplished by sequencing the internal transcribed spacer of the ribosomal DNA (ITS-rDNA) using the primer pair V9G39 and LR340 for PCR and ITS441 as sequencing primer. Fungal DNA was amplified on a TProfessional Trio PCR thermocycler (Biometra GmbH, Göttingen, Germany). PCR products were visualized utilizing 1% agarose gels. SeqMan program version 11.0.0 (DNAStar; Lasergene) was used for the processing of sequences. Species identification was confirmed by GenBank basic local alignment search tool (BLAST) searches. HS of the FKS gene were amplified and sequenced as described previously.42 Relevant HS mutations were detected by ApE- A plasmid Editor v1.17. software.

Susceptibility testing

Initial in vitro susceptibility testing was performed by broth microdilution in accordance with EUCAST.28 Antifungal agents for susceptibility testing of the NRZMyk were provided by Pfizer Inc., Peapack, NJ, USA (anidulafungin and fluconazole) and MSD, Rahway, NJ, USA (caspofungin). The storage of plates did not exceed 6 months (at −80°C). RPMI supplemented with 2% glucose was used as a medium. The final inoculum ranged between 0.5 × 105 and 2.5 × 105 cfu/mL. MICs were assessed with a nephelometer (Labsystems Nepheloskan Ascent Microplate Reader Type 750) after 24 h of incubation at 35°C, defining the endpoint of growth as a ≥ 50% inhibition in comparison with the drug-free control. Current breakpoints (BP) were applied in accordance with CLSI or EUCAST as described in Table S2.43,44 Commercial testing devices used are listed in Table S3.

Reference strain ATCC 22019 Candida parapsilosis was used as a quality control.

Data assessment and statistics

Clinical data were extracted in an anonymized form from the NRZMyk database. Figures were designed in GraphPad Prism Version 7.05. The comparison of anidulafungin MICs and FKS HS mutations was performed using a Kruskal–Wallis test and Dunn’s multiple comparisons test (P values adjusted for multiple testing) in GraphPad Prism Version 7.05.

Results

Characteristics of C. glabrata strains submitted to NRZMyk

Over 5 years, a total of 178 C. glabrata clinical isolates were sent to the NRZMyk (20 strains in 2015; 47 strains in 2016; 35 strains in 2017; 41 strains in 2018; and 35 strains in 2019). Two isolates represented identical duplicates of initial isolates from the same patient and were thus excluded from further analysis. The remaining 176 C. glabrata isolates derived from 175 patients (Figure 1). Two non-identical isolates (2016-275 and 2016-293) were isolated from a single patient. The majority [14% (24/175)] of corresponding patients were between 61–65 years of age, 56% were male (Figure 2a). Most of the C. glabrata isolates (40%) had been grown from blood culture, 25% had been isolated from an intra-abdominal specimen and 7% from urine samples (Figure 2b). The most common reason for submission to the NRZMyk was a request for reference susceptibility testing. Thus, these strains represent a highly biased subset of C. glabrata isolates from Germany, where the primary laboratory had decided that submission to the NRZMyk was warranted. Importantly, this precludes any estimations about the overall frequency of resistance in C. glabrata in Germany. Species identification as C. glabrata was confirmed for all isolates using ITS sequencing.

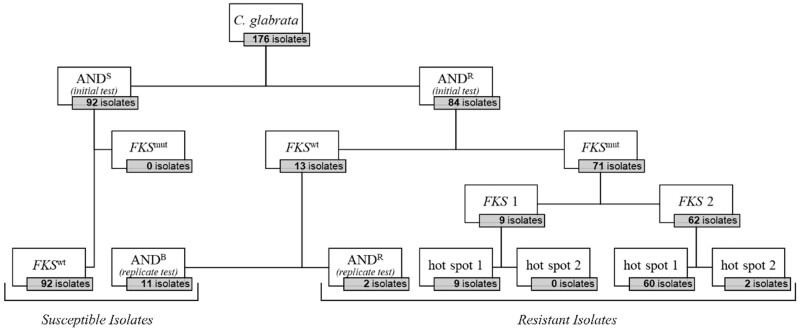

Figure 1.

176 C. glabrata isolates submitted to the NRZMyk (2015–19) subdivided by susceptibility to anidulafungin (AND) and concordant FKS phenotype. Broth microdilution and breakpoint (BP) are according to EUCAST. FKS1 and FKS2 hot spots were sequenced. Abbreviations: anidulafungin susceptible (ANDS); anidulafungin ‘borderline’ with MICs fluctuating around BP (ANDB); anidulafungin-resistant (ANDR). FKS wildtype (FKSwt); FKS mutation (FKSmut).

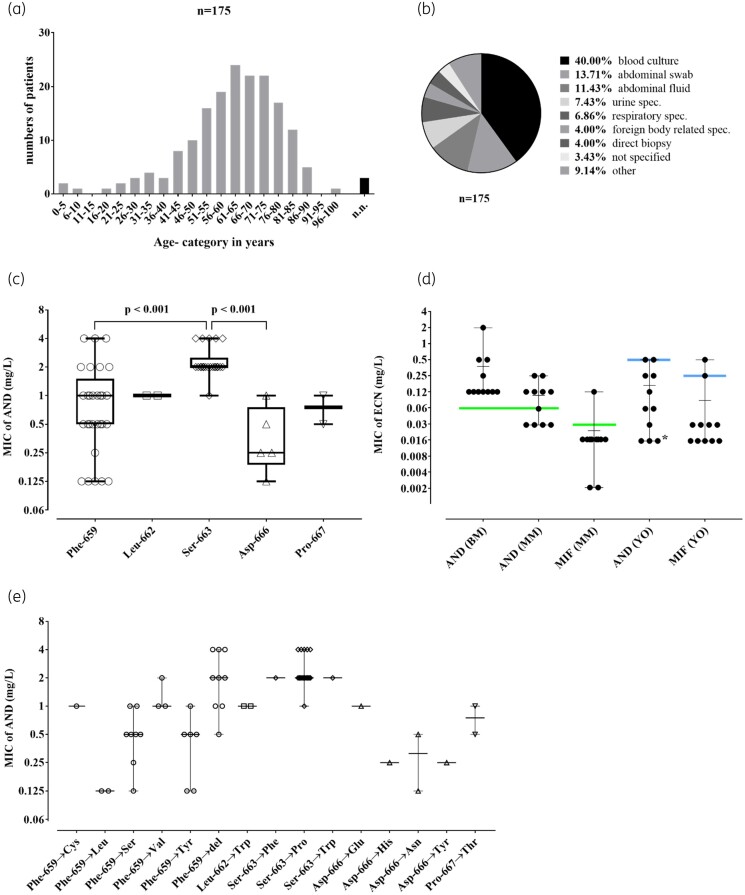

Figure 2.

(a) Categorized age distribution of patients suffering from C. glabrata infection (n = 175). (b) Isolation site of obtained specimens (n = 175). (c) MIC values for anidulafungin (AND) at indicated amino acid positions in FKS2 hot spot 1. A significant difference between position 663 and 659 (P < 0.001) as well as 663 and 666 (P < 0.001) was observed. The box plots show the median, lower/upper quartile and range of each position. (d) Comparison of anidulafungin (AND) and micafungin (MIF) susceptibility results using different susceptibility testing devices and breakpoints on 13 selected borderline isolates: AND broth microdilution (AND BM) (according to EUCAST); AND and MIF Merlin Micronaut microdilution (AND MM; MIF MM) (according to EUCAST); AND and MIF Yeast One Sensititre microdilution (AND YO; MIF YO) (according to CLSI). MIC value of echinocandins (MIC of ECN). Scatter plots show the range and median. Coloured lines refer to the current MIC breakpoint applicable for the antifungal substance according to its testing method and affiliated reference society [green for EUCAST (AND >0.06 mg/L; MIF >0.03 mg/L); blue for CLSI (AND ≥0.5 mg/L; MIF ≥0.25 mg/L)]. The asterisk is used as specific marker for three strains with AND MIC values ≤0.016 mg/L in YO. (e) Distribution of MIC values concerning mutations in FKS2 hot spot 1. Scatter plots show the range and median of each amino acid exchange.

Anidulafungin susceptibility testing

Upon receipt of the strains at the NRZMyk, anidulafungin MICs were determined for all 176 isolates by broth microdilution according to EUCAST standards. Overall, anidulafungin MICs ranged from ≤0.016 mg/L to >8 mg/L. Ninety-two isolates (52%) were found to be susceptible to anidulafungin (ANDS) in accordance with EUCAST breakpoints (MIC ≤0.06 mg/L, Figure 1). Eighty-four isolates (48%) were classified as anidulafungin-resistant (ANDR) according to EUCAST interpretation (MIC >0.06 mg/L, Figure 1).

FKS sequence analysis of C. glabrata isolates

FKS sequencing was performed for all 176 isolates. None of the 92 ANDS isolates harboured a mutation in the known HS regions of the FKS1 or FKS2 gene. In contrast, 71 out of 84 ANDR isolates did contain a single mutation in one of the HS regions of either FKS1 or FKS2 (FKSmut).

Most of these ANDR/FKSmut isolates (62/71; 87.2%) showed a mutation in FKS2, compared with only 12.7% (9/71) having an FKS1 mutation. All FKS1 mutations affected FKS1 HS1, whereas 60 FKS2 mutations affected FKS2 HS1 and 2 affected FKS2 HS2 (Figure 1).

The majority of mutations found (those located in FKS2 HS1) affected five different positions: Leu-662 (n = 2), Asp-666 (n = 5), Pro-667 (n = 2), Phe-659 (n = 29) and Ser-663 (n = 22), all of which have previously been identified to correspond to echinocandin resistance.33,34 Together, mutations affecting Phe-659 or Ser-663 accounted for nearly three-quarters of all mutations found in this study (Figure 2c). Other FKS mutations in ANDR strains affected positions in FKS1 HS1 [Phe-625 (n = 5), Ser-629 (n = 2) Leu-630 (n = 1) and Asp-632 (n = 1)] or FKS2 HS2 [Arg-1378 (n = 2)].

Isolates harbouring relevant mutations in FKS2 HS1 position 663 (1×Ser-663→Phe; 1×Ser-663→Trp; 20 ×Ser-663→Pro; Figure 2e) were found to be associated with significantly higher anidulafungin MICs compared with mutations in position Phe-659 and position Asp-666 (P value <0.001; Figure 2c). This difference was confirmed by caspofungin MIC data for Ser-663 and Phe-659 using the same subset of mutated strains (n = 71) (Figure S1). The most frequent mutation Ser-663→Pro was associated with high anidulafungin MICs and the overwhelming majority of isolates harbouring this mutation showed an MIC of 2 mg/L (range: 1–4 mg/L).

In contrast, FKS2 HS1 Phe-659 mutations resulted in rather divergent phenotypes. Isolates with a deletion in position 659 showed higher anidulafungin MICs compared with other mutations within this position (n = 9; median: 2 mg/L; range: 0.5–4 mg/L), whereas Phe-659→Tyr (n = 6) and Phe-659→Ser (n = 8) mutations both showed a median anidulafungin MIC of 0.5 mg/L and thus seemed to be associated with a less-pronounced MIC increase (Figure 2c and e). Additional mutations affecting Phe-659 were observed only in a limited number of strains (3×Phe-659→Val, 2×Phe-659→Leu, 1×Phe-659→Cys), preventing further analysis of any correlation with MICs (Figure 2e).

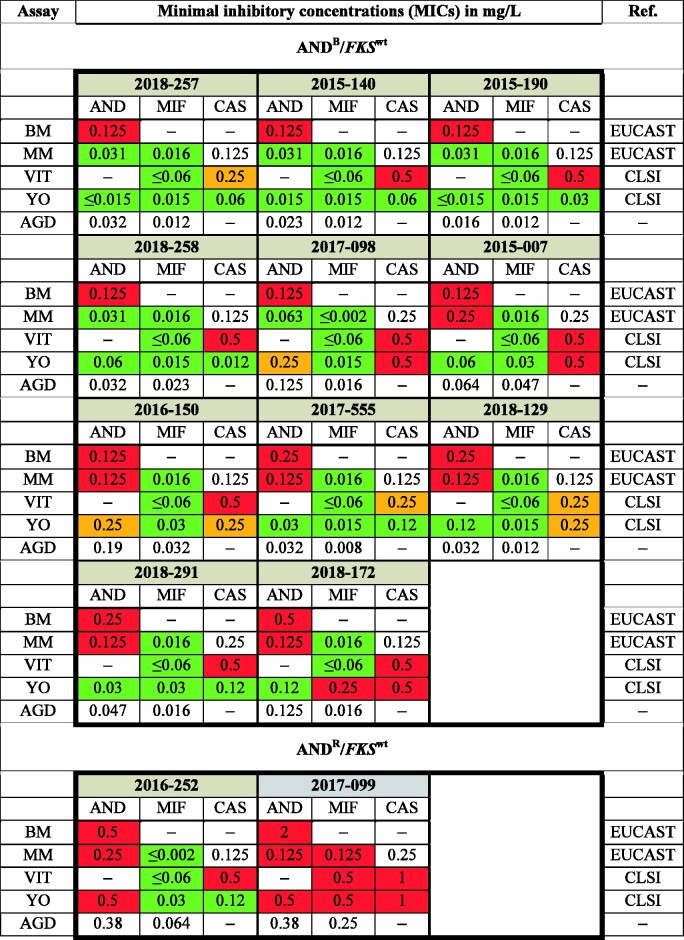

Echinocandin susceptibility in ANDR/FKSwt C. glabrata

Initially, 13 C. glabrata isolates (7%) were identified as ANDR by EUCAST reference testing without carrying any matching FKS HS mutations (ANDR/FKSwt). Anidulafungin MICs for these strains ranged from 0.125 mg/L (n = 7), 0.25 mg/L (n = 3) to ≥0.5 mg/L (n = 3) (Figure 3). We therefore performed a range of additional susceptibility tests for these isolates and included testing with micafungin and caspofungin to determine whether phenotypic resistance of these strains to echinocandins could be confirmed (Figure 3). For this, we used the Micronaut microdilution assay (MICRONAUT- AM, Merlin Diagnostika- A Bruker Company, Bornheim, Germany) (MM) interpreted according to EUCAST as well as the Sensititre Yeast One YO10 (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Massachusetts, USA) (YO) and the VITEK2 (AST-YS08 cartridge, bioMérieux, Paris, France) (VIT), both interpreted according to CLSI. Additionally, anidulafungin and micafungin agar gradient diffusion (AGD) tests (Etest, bioMérieux, Marcy-l'Étoile, France) were performed (Figure 3 and Figure 2d). As a result, 11 of the 13 ANDR/FKSwt were tested and found to be susceptible to micafungin in two out of three (n = 1; 2018-172) or all three (n = 10) assays performed. Furthermore, test results for anidulafungin in the additional assays varied between susceptible and resistant (Figure 3), indicating that anidulafungin MICs for these strains are fluctuating around the breakpoint. In addition, all of these strains tested as intermediate (I) or resistant (R) in at least one test for caspofungin, interpreted according to CLSI. However, none of these 11 isolates consistently tested resistant to any of the echinocandins in all assays applied. Thus, we refer to these isolates as ‘borderline’ with regard to anidulafungin testing (ANDB, Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Susceptibility testing of 11 ANDB/FKSwt isolates and 2 ANDR/FKSwt isolates using multiple assays. Initial broth microdilution (BM) was extended with the commercial testing devices Yeast one (YO), VITEK 2 (VIT), Merlin Micronaut (MM) and agar gradient diffusion tests (AGD; Etest). Antifungal agents: AND, anidulafungin; MIF, micafungin; CAS, caspofungin. Colours according to breakpoints of either EUCAST or CLSI: red (resistant); orange (intermediate); green (susceptible).

Two of the 13 ANDR/FKSwt strains (2016-252 and 2017-099) were found to be resistant to anidulafungin by all testing methodologies.

C. glabrata 2016-252 was resistant to anidulafungin in all test systems, confirming the result obtained using the EUCAST reference method. Interestingly, 2016-252 was found to be susceptible to micafungin in all assays used, contradicting the paradigm of complete cross-resistance within the echinocandin class of antifungals (Figure 3). Thus, 2016-252 was categorized as ANDR/MIFS/FKSwt.

C. glabrata 2017-099 was consistently resistant to both anidulafungin and micafungin in all test systems and was thus categorized ANDR/MIFR/FKSwt (Figure 3).

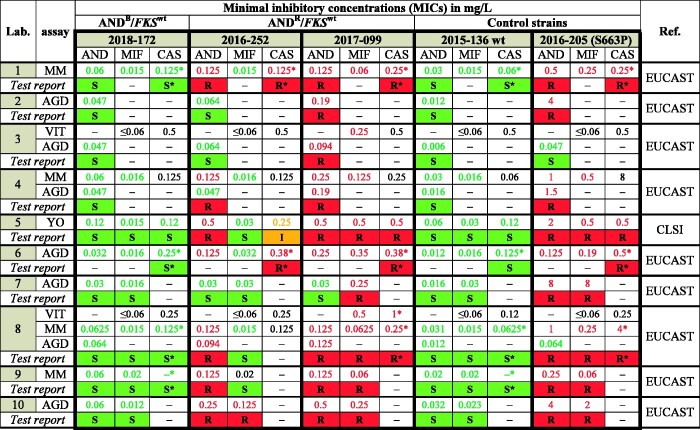

Inter-laboratory susceptibility testing of ANDR/FKSwt

To address the potential consequences of MICs fluctuating around clinical breakpoints and echinocandin resistance in the absence of FKS mutations for phenotypic susceptibility testing, we conducted a blinded trial. C. glabrata strains, 2016-252 (ANDR/MIFS/FKSwt), 2018-172 (ANDB/FKSwt) and 2017-099 (ANDR/MIFR/FKSwt) were sent to 10 different microbiology laboratories in our InfectControl sentinel laboratory network for susceptibility testing. 2015-136 (ANDS/MIFS/FKSwt) and 2016-205 (ANDR/MIFR/FKSmut; FKS mutation: Ser-663→Pro in FKS2 HS1) were added as controls. In total, the 10 laboratories used four different assays generating 29 MIC values for each strain (Figure 4). With one exception, the control strains were correctly tested as susceptible or resistant by all labs, although one laboratory generated a false susceptible result for 2016-205 by anidulafungin AGD test, which, however, would have been ignored during result interpretation (Figure 4). Strain 2018-172 was tested and found to be susceptible to anidulafungin and micafungin by all labs, indicating that the borderline phenotype did not occur in a significant proportion of blinded routine testing (Figure 4). C. glabrata 2016-252 was tested as anidulafungin resistant by six laboratories, anidulafungin susceptible by three laboratories and generated contradictory results with two test systems used in one laboratory. In line with the results from the NRZMyk, nine labs evaluated this strain as micafungin susceptible, while one laboratory found this strain to be micafungin resistant. Except for a single susceptible anidulafungin AGD test, C. glabrata 2017-099 was scored as resistant to all echinocandins tested, confirming phenotypic resistance despite the absence of an FKS mutation (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Susceptibility testing results for one ANDB/FKSwt strain, two ANDR/FKSwt and two control strains by 10 German microbiology laboratories. 2015-136 (FKS wild-type) and 2016-205 (mutation in FKS2 HS1 S663P) were added as controls. Assays used: MM, Merlin Micronaut; YO, Yeast one; VIT, VITEK 2; AGD, agar gradient diffusion test. Antifungal agents: AND, anidulafungin; MIF, micafungin; CAS, caspofungin. Colours are applied according to breakpoints of either EUCAST or CLSI: red (resistant); orange (intermediate); green (susceptible). Susceptibility interpretation of CAS MIC data marked with an asterisk are derived from AND and/or MIF, as CAS lacks official EUCAST BP.

Fluconazole and multidrug resistance

Fluconazole MICs were determined using EUCAST reference methodology. MICs were distributed from 0.25 mg/L to >64 mg/L (median 4 mg/L). Resistance to fluconazole was found in 38% (n = 67) of the strains (those with MICs >16 mg/L; Table S1). Of those, 26 isolates showed combined fluconazole and echinocandin resistance, all of them with a concordant FKS mutation (14% of all isolates).

The type of FKS mutations for these strains was overall similar to that of all ANDR isolates. In 23 strains an FKS2 HS1 mutation (11×Phe-659; 7×Ser-663; 4×Asp-666; 1×Pro-667) was detected, whereas in three cases an FKS1 HS1 mutation (2×Phe-625; 1×Ser-629) was confirmed (Table S1).

Within the group of multidrug-resistant C. glabrata, nine isolates (three each from 2016, 2017 and 2018) were from bloodstream infections (Table 1). Three of those (2016-058, 2016-064 and 2017-252) showed elevated echinocandin and fluconazole MIC values, at the upper end of the tested ranges (anidulafungin 2–4 mg/L; caspofungin >8 mg/L; fluconazole >64 mg/L) and all carried Ser-663→Pro mutations (Table 1). 2016-058 was obtained from a patient suffering from acute myeloid leukaemia, with graft versus host disease of the skin and gastrointestinal tract, under triple immunosuppressive therapy after transplantation. Antifungal therapy was initially switched from voriconazole to caspofungin. Upon further clinical deterioration (multiple organ failure) a combination of anidulafungin and amphotericin B was administered (Table 1). Isolate 2016-064 had been isolated from a patient with cirrhosis due to alcoholic liver disease, lactic acidosis and pneumonia. Treatment was escalated from anidulafungin to amphotericin B (Table 1). The strain 2017-252 was isolated from a patient with acute liver failure and transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt (TIPS) infection. Candidaemia was treated with flucytosine and caspofungin (Table 1). All three patients succumbed to the infection. In contrast five of the remaining patients with MDR C. glabrata bloodstream infection survived. In one case (1/9) no outcome data was available (Table 1).

Table 1.

Outcome and patient data for MDR C. glabrata strains associated with bloodstream infection between 2016 and 2019

| NRZ-ID | Sex | Age category (years) | Specimen | MIC (mg/L) |

Mutation in FKS | Pre-existing conditions | Reason for admission | Antifungal therapy | Outcome of candidaemia | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| AND | CAS | FLC | |||||||||

| 2016-058 | f | 46–50 | blood culture | 4 | >8 | >64 | S663P (FKS2 HS1) | AML | GvHD | VRC, CAS, AND + AMB | deceased |

| 2016-064 | f | 61–65 | blood culture | 4 | >8 | >64 | S663P (FKS2 HS1) | ALRD, cirrhosis | lactic acidosis, pneumonia | AND, AMB | deceased |

| 2016-144 | m | 76–80 | blood culture | 0.5 | 2 | >64 | F659S (FKS2 HS1) | – | – | – | survived |

| 2017-041 | f | 46–50 | blood culture | 2 | >8 | 32 | F659del (FKS2 HS1) | lung cancer | sepsis | CAS | survived |

| 2017-252 | m | 51–55 | blood culture | 2 | >8 | >64 | S663P (FKS2 HS1) | liver failure | TIPS infection | CAS + 5FC | deceased |

| 2017-312 | m | 76–80 | blood culture | 0.125 | 0.5 | >64 | D666N (FKS2 HS1) | – | – | FLC | survived |

| 2018-067 | m | 46–50 | blood culture | 1 | 8 | >64 | F625C (FKS1 HS1) | aspiration pneumonia | port infection | FLC, CAS | survived |

| 2018-462 | m | 56–60 | blood culture | 0.5 | 2 | 64 | P667T (FKS2 HS1) | chronic heart failure | infected LVAD | CAS (1 year) | survived |

| 2019-615 | m | 76–80 | blood culture | 1 | >8 | 32 | F659del (FKS2 HS1) | – | – | – | – |

Abbreviations: AML, acute myeloid leukaemia; ARLD, alcohol-related liver disease; GvHD, graft versus host disease; LVAD, left ventricular assist device; TIPS, transjugular intrahepatic portosystemic shunt; AND, anidulafungin; AMB, amphotericin B; CAS, caspofungin; 5FC, flucytosine; VRC, voriconazole.

Discussion

Antifungal drug resistance has become a major concern and limits therapeutic options in life-threatening invasive fungal infections. New resistant fungal pathogens, such as Candida auris, emerge and spread globally.3 In addition, well-known fungal pathogens, including Candida spp., Aspergillus spp. and Cryptococcus spp. have acquired resistant phenotypes in recent decades.45–47

The widespread use of echinocandins as first-line therapy for candidaemia promotes the emergence of resistant strains. The haploid genome of C. glabrata enables rapid mutation that can occur during therapy and result in treatment failure.48 This may be further enhanced by alterations within the DNA mismatch repair gene resulting in mutator phenotypes.22,23 Our study confirms that echinocandin resistance in C. glabrata is emerging in Germany. We can confirm previous findings showing that mutational HS1 of both FKS genes plays a major role in mediating echinocandin resistance, as 97% (69/71) of all relevant mutations are detected in this region (Figure 1).34,49,50 Zhao et al.34 designed a rapid FKS1/FKS2 HS1 genotyping tool based on melting curve analysis which includes the most relevant mutations of HS1 (8×FKS1 HS1; 7×FKS2 HS1) and showed 100% specificity and 100% sensitivity in WT/non-WT discrimination validated by 186 clinical C. glabrata isolates. Applied to our results, 69% (49/71) of all mutations found would have been detected within a timeframe of only 3 h.

The majority (72%, 51/71) of all echinocandin-resistant strains with a mutated FKS revealed an amino acid change at positions Phe-659 and Ser-663 (both FKS1 HS2) (Figure 2c). In particular, Ser-663→Pro and Phe-659→del are associated with high echinocandin resistance and therefore considered most important in Germany, supporting observations made in recent studies and meta-analyses (Figure 2e).33,42,49,51–53 Interestingly, all detected mutations at Ser-663 exchange the polar amino acid serine (Ser) with a hydrophobic non-polar amino acid [phenylalanine (Phe), proline (Pro) or tryptophan (Trp)]. This change in polarity might contribute to the phenomenon of reduced susceptibility, perhaps due to a decrease in affinity of the 1,3-β-d-glucan synthase for the antifungal drug. Of note, compared with any replacement with other amino acids, a complete deletion at Phe-659 appears to have the highest impact on resistance to echinocandins (Figure 2e).

In 93% (163/176) of the analysed strains a correct phenotypic differentiation between FKSwt and FKSmut was possible by anidulafungin reference microdilution alone, applying the current EUCAST BP (Figure 1). All (92/92) of the isolates found to be phenotypically anidulafungin susceptible did not harbour any relevant FKS HS mutation, underlining the fact that FKS-mutated strains do confer resistance (Figure 1).23,54

However, in 7% (13/176) of the isolates a decreased susceptibility to anidulafungin was observed phenotypically, while genotypic resistance could not be confirmed (Figure 1). The majority (11/13) showed MICs fluctuating around the clinical breakpoints upon re-testing indicating a ‘borderline’ resistance (ANDB). Notably, these 11 strains were found to be micafungin susceptible in all assays conducted, suggesting a higher discriminative power in detecting FKSwt strains compared with anidulafungin. An adaption of the current anidulafungin EUCAST BP by implementing an area of technical uncertainty (ATU) at anidulafungin MICs of 0.125 mg/L or recommending additional testing of micafungin in these rare cases might address this issue.

Differences in the in vivo activity of mutated C. glabrata strains concerning different echinocandins have been observed, questioning the paradigm of complete cross-resistance in this class of antifungals.23,55 We identified one isolate (2016-252) which did not carry an FKS mutation and was consistently tested ANDR by 8 of 11 labs, including the NRZMyk, but was susceptible to micafungin (10/11). It remains unclear whether this reflects an extreme borderline phenotype in a susceptible isolate or points to an as yet unknown mechanism conferring selective resistance to anidulafungin. Notably, Healy et al.56 described a related phenotype showing reduced susceptibility to caspofungin while micafungin susceptibility was paradoxically increased. More importantly, we identified one FKSwt isolate (2017-099) that exhibits reduced susceptibility to all echinocandins, contradicting the paradigm that echinocandin resistance is only mediated by such mutations.23 This in vitro resistance (all MICs were found to be above the current BP) may not serve as a sufficient proof of a refractory therapeutic response in vivo, but it strongly hints that there may be relevant FKS-independent resistance mechanisms. Functional, biochemical and genomic analyses are underway to further elucidate this phenomenon.

Our round robin test of German laboratories highlighted further limitations of phenotypic susceptibility testing. Notably, the VITEK 2 testing cartridge (bioMérieux) does not include anidulafungin and the tested concentrations for micafungin do not cover the EUCAST BP of 0.03 mg/L. Therefore, this assay is not able to distinguish between resistant and susceptible strains (Figure 4). In addition, the notoriously difficult reading of AGD test results could potentially have resulted in a major error as an echinocandin-resistant FKSmut isolate was classified susceptible.

In conclusion, our data emphasize the clinical importance of susceptibility testing for C. glabrata strains but also highlight technical difficulties. Our finding, that infection with MDR C. glabrata strains with Ser-663 mutations result in adverse outcomes is in line with studies indicating that certain genetic phenotypes may be connected to increased mortality.57–59 These evolving multiresistant strains represent a major threat and need to be monitored closely in epidemiological surveillance studies. Micafungin testing is clearly more robust than anidulafungin testing and better suited to identify isolates with a mutated FKS gene. If available, genotypic resistance testing is a rapid and reliable tool to identify resistant strains,24,26,60 although our findings suggest that FKS-independent resistance mechanisms may occur in rare cases. Diagnostic laboratories urgently need to optimize their susceptibility testing portfolio for Candida.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to Anastasia Besenfelder, Stefan Jaborek, Carmen Karkowski, Dominique Krause, Grit Mrotzek, Sabrina Mündlein and Christiane Weigel for technical assistance. In addition, we thank Bodo Eing, Hanna Gölz, Barbara Graf, Armin Hoffmann, Marcel Jarick, Ricarda Plogmann-Pietsch, Pascal Radtke, Roman Schwarz, Christof Seckert and Lisa Vorbeck for providing outcome data.

We are grateful to Pfizer Inc., Peapack, NJ, USA (Anidulafungin, Fluconazole) and MSD, Rahway, NJ, USA (Caspofungin) for providing antifungal compounds.

This data was partly presented during the poster session IV at the 53th Scientific Conference of the German speaking Mycological Society (DMykG) in Mannheim (Poster ID: PIV4)

Members of the InfectControl fungal infections study group

Johannes Elias (Institute of Microbiology, DRK Kliniken Berlin, Berlin, Germany), Frieder Fuchs (Institute for Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene, University of Cologne, Medical Faculty and University Hospital of Cologne, Cologne, Germany), Andrea Haas (Department of Medical Microbiology and Hospital Epidemiology, Max von Pettenkofer Institute, Faculty of Medicine, LMU Munich, Munich, Germany), Axel Hamprecht (Institute for Medical Microbiology and Virology, University of Oldenburg, Oldenburg, Germany), Jürgen Held (Mikrobiologisches Institut—Klinische Mikrobiologie, Immunologie und Hygiene, Universitätsklinikum Erlangen und Friedrich-Alexander-Universität (FAU) Erlangen-Nürnberg, Erlangen, Germany), Christina Hess (Institute of Medical Microbiology and Hygiene, Medical Center—University of Freiburg, Faculty of Medicine, Freiburg, Germany), Michael Hogardt (German Consiliary Laboratory on Cystic Fibrosis Bacteriology, Institute of Medical Microbiology and Infection Control, University Hospital Frankfurt, Goethe University, Frankfurt am Main, Germany), Peter-Michael Rath (Institute of Medical Microbiology, University Hospital Essen, University of Duisburg-Essen, Essen, Germany), Kathrin Rothe (Institute for Medical Microbiology, Immunology and Hygiene, Technical University of Munich, School of Medicine, Munich, Germany), Jörg Steinmann (Institute of Clinical Hygiene, Medical Microbiology and Infectiology, General Hospital Nürnberg, Paracelsus Medical University, Nuremberg, Germany)

Funding

This work was supported by the Federal Ministry for Education and Science (BMBF) within the programme InfectControl project FINAR2.0 (grant number 03ZZ0834A). The NRZMyk is funded by the Robert Koch Institute from funds provided by the German Ministry of Health (grant number 1369-240).

Transparency declarations

None to declare.

Author contributions

O.K. designed the study. G.W., R.M. and A.M.A. supplied the NRZMyk data. O.K., G.W., R.M., M.H. and A.M.A. interpreted the findings. M.H. contributed to the statistical analysis. Members of the InfectControl Fungal Infections Study Group conducted a round robin test and contributed test results. A.M.A. wrote the first manuscript version. All authors contributed to subsequent and critical revisions and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Supplementary data

Figure S1 and Tables S1 to S3 are available as Supplementary data at JAC-AMR Online.

References

- 1. Tabah A, Koulenti D, Laupland K. et al. Characteristics and determinants of outcome of hospital-acquired bloodstream infections in intensive care units: the EUROBACT International Cohort Study. Intensive Care Med 2012; 38: 1930–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Toth R, Nosek J, Mora-Montes HM. et al. Candida parapsilosis: from Genes to the Bedside. Clin Microbiol Rev 2019; 32: e00111-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chowdhary A, Sharma C, Meis JF.. Candida auris: a rapidly emerging cause of hospital-acquired multidrug-resistant fungal infections globally. PLoS Pathog 2017; 13: e1006290. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Healey KR, Perlin DS.. Fungal resistance to echinocandins and the MDR phenomenon in Candida glabrata. J Fungi (Basel) 2018; 4: 105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Ullmann AJ, Akova M, Herbrecht R. et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: adults with haematological malignancies and after haematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HCT). Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18 Suppl 7: 53–67. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Hope WW, Castagnola E, Groll AH. et al. ESCMID guideline for the diagnosis and management of Candida diseases 2012: prevention and management of invasive infections in neonates and children caused by Candida spp. Clin Microbiol Infect 2012; 18 Suppl 7: 38–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. von Lilienfeld-Toal M, Wagener J, Einsele H. et al. Invasive fungal infection. Dtsch Arztebl Int 2019; 116: 271–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Klingspor L, Ullberg M, Rydberg J. et al. Epidemiology of fungaemia in Sweden: a nationwide retrospective observational survey. Mycoses 2018; 61: 777–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Colombo AL, de Almeida Junior JN, Slavin MA. et al. Candida and invasive mould diseases in non-neutropenic critically ill patients and patients with haematological cancer. Lancet Infect Dis 2017; 17: e344–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Fraser M, Borman AM, Thorn R. et al. Resistance to echinocandin antifungal agents in the United Kingdom in clinical isolates of Candida glabrata: Fifteen years of interpretation and assessment. Med Mycol 2019; 58: 219–26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Duggan S, Leonhardt I, Hunniger K. et al. Host response to Candida albicans bloodstream infection and sepsis. Virulence 2015; 6: 316–26. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Schwab F, Geffers C, Behnke M. et al. ICU mortality following ICU-acquired primary bloodstream infections according to the type of pathogen: a prospective cohort study in 937 Germany ICUs (2006-2015). PLoS One 2018; 13: e0194210. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Goemaere B, Lagrou K, Spriet I. et al. Clonal spread of Candida glabrata bloodstream isolates and fluconazole resistance affected by prolonged exposure: a 12-year single-center study in Belgium. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e00591–18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Farmakiotis D, Kontoyiannis DP.. Epidemiology of antifungal resistance in human pathogenic yeasts: current viewpoint and practical recommendations for management. Int J Antimicrob Agents 2017; 50: 318–24. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Castanheira M, Deshpande LM, Davis AP. et al. Monitoring antifungal resistance in a global collection of invasive yeasts and molds: application of CLSI epidemiological cutoff values and whole-genome sequencing analysis for detection of azole resistance in Candida albicans. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2017; 61: e00906-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Perlin DS. Current perspectives on echinocandin class drugs. Future Microbiol 2011; 6: 441–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Wagener J, Striegler K, Wagener N.. Alpha- and β-1,3-glucan synthesis and remodeling. Curr Top Microbiol Immunol 2020; 425: 53–82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Katiyar SK, Alastruey-Izquierdo A, Healey KR. et al. Fks1 and Fks2 are functionally redundant but differentially regulated in Candida glabrata: implications for echinocandin resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 6304–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Healey KR, Paderu P, Hou X. et al. Differential regulation of echinocandin targets Fks1 and Fks2 in Candida glabrata by the post-transcriptional regulator Ssd1. J Fungi (Basel) 2020; 6: 143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Garcia-Effron G, Lee S, Park S. et al. Effect of Candida glabrata FKS1 and FKS2 mutations on echinocandin sensitivity and kinetics of 1,3-β-D-glucan synthase: implication for the existing susceptibility breakpoint. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2009; 53: 3690–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Katiyar S, Pfaller M, Edlind T.. Candida albicans and Candida glabrata clinical isolates exhibiting reduced echinocandin susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2006; 50: 2892–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Singh A, Healey KR, Yadav P. et al. Absence of Azole or echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata isolates in India despite background prevalence of strains with defects in the DNA mismatch repair pathway. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2018; 62: e00195-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Arendrup MC, Patterson TF.. Multidrug-resistant candida: epidemiology, molecular mechanisms, and treatment. J Infect Dis 2017; 216: S445–51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Alexander BD, Johnson MD, Pfeiffer CD. et al. Increasing echinocandin resistance in Candida glabrata: clinical failure correlates with presence of FKS mutations and elevated minimum inhibitory concentrations. Clin Infect Dis 2013; 56: 1724–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Cleveland AA, Farley MM, Harrison LH. et al. Changes in incidence and antifungal drug resistance in candidemia: results from population-based laboratory surveillance in Atlanta and Baltimore, 2008–2011. Clin Infect Dis 2012; 55: 1352–61. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Shields RK, Nguyen MH, Press EG. et al. The presence of an FKS mutation rather than MIC is an independent risk factor for failure of echinocandin therapy among patients with invasive candidiasis due to Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 4862–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Klotz U, Schmidt D, Willinger B. et al. Echinocandin resistance and population structure of invasive Candida glabrata isolates from two university hospitals in Germany and Austria. Mycoses 2016; 59: 312–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Arendrup MC, Meletiadis J, Mouton JW. et al. and the Subcommittee on Antifungal Susceptibility Testing (AFST) of the ESCMID European Committee for Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST). EUCAST Definitive Document E.DEF 7.3.2: Method for the determination of broth dilution minimum inhibitory concentrations of antifungal agents for yeasts. April 2020. https://www.eucast.org/fileadmin/src/media/PDFs/EUCAST_files/AFST/Files/EUCAST_E_Def_7.3.2_Yeast_testing_definitive_revised_2020.pdf.

- 29. CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts—Fourth Edition: M27. 2017.

- 30. Cuenca-Estrella M, Gomez-Lopez A, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. et al. Comparison of the Vitek 2 antifungal susceptibility system with the clinical and laboratory standards institute (CLSI) and European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) Broth Microdilution Reference Methods and with the Sensititre YeastOne and Etest techniques for in vitro detection of antifungal resistance in yeast isolates. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48: 1782–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Pfaller MA, Castanheira M, Diekema DJ. et al. Comparison of European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing (EUCAST) and Etest methods with the CLSI broth microdilution method for echinocandin susceptibility testing of Candida species. J Clin Microbiol 2010; 48: 1592–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Pfaller MA, Chaturvedi V, Diekema DJ. et al. Comparison of the Sensititre YeastOne colorimetric antifungal panel with CLSI microdilution for antifungal susceptibility testing of the echinocandins against Candida spp., using new clinical breakpoints and epidemiological cutoff values. Diagn Microbiol Infect Dis 2012; 73: 365–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Bienvenu AL, Leboucher G, Picot S.. Comparison of fks gene mutations and minimum inhibitory concentrations for the detection of Candida glabrata resistance to micafungin: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Mycoses 2019; 62: 835–46. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Zhao Y, Nagasaki Y, Kordalewska M. et al. Rapid Detection of FKS-Associated Echinocandin Resistance in Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2016; 60: 6573–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Arendrup MC, Garcia-Effron G, Lass-Florl C. et al. Echinocandin susceptibility testing of Candida species: comparison of EUCAST EDef 7.1, CLSI M27-A3, Etest, disk diffusion, and agar dilution methods with RPMI and isosensitest media. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 426–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Pfaller MA. Antifungal drug resistance: mechanisms, epidemiology, and consequences for treatment. Am J Med 2012; 125: S3–13. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Perlin DS. Echinocandin resistance, susceptibility testing and prophylaxis: implications for patient management. Drugs 2014; 74: 1573–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Walther G, Pawlowska J, Alastruey-Izquierdo A. et al. DNA barcoding in Mucorales: an inventory of biodiversity. Persoonia 2013; 30: 11–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. de Hoog GS, Gerrits van den Ende AH. Molecular diagnostics of clinical strains of filamentous Basidiomycetes. Mycoses 1998; 41: 183–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Vilgalys R, Hester M.. Rapid genetic identification and mapping of enzymatically amplified ribosomal DNA from several Cryptococcus species. J Bacteriol 1990; 172: 4238–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. White TJ, Bruns TD, Lee SB. et al. Amplification and Direct Sequencing of Fungal Ribosomal RNA Genes for Phylogenetics. Academic Press, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 42. Zimbeck AJ, Iqbal N, Ahlquist AM. et al. FKS mutations and elevated echinocandin MIC values among Candida glabrata isolates from U.S. population-based surveillance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2010; 54: 5042–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. The European Committee on Antimicrobial Susceptibility Testing. Breakpoint tables for interpretation of MICs for antifungal agents v. 10.0. 2020. http://www.eucast.org/astoffungi/clinicalbreakpointsforantifungals/.

- 44. CLSI. Performance Standards for Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts—First Edition: M60. 2017.

- 45. Meis JF, Chowdhary A, Rhodes JL. et al. Clinical implications of globally emerging azole resistance in Aspergillus fumigatus. Philos Trans R Soc Lond B Biol Sci 2016; 371: 20150460. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Iyer KR, Revie NM, Fu C. et al. Treatment strategies for cryptococcal infection: challenges, advances and future outlook. Nat Rev Microbiol 2021; 19: 454–66. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Beardsley J, Halliday CL, Chen SC. et al. Responding to the emergence of antifungal drug resistance: perspectives from the bench and the bedside. Future Microbiol 2018; 13: 1175–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Barber AE, Weber M, Kaerger K. et al. Comparative genomics of serial Candida glabrata isolates and the rapid acquisition of echinocandin resistance during therapy. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e01628-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Pham CD, Iqbal N, Bolden CB. et al. Role of FKS Mutations in Candida glabrata: MIC values, echinocandin resistance, and multidrug resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 4690–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Pham CD, Bolden CB, Kuykendall RJ. et al. Development of a Luminex-based multiplex assay for detection of mutations conferring resistance to Echinocandins in Candida glabrata. J Clin Microbiol 2014; 52: 790–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Rivero-Menendez O, Navarro-Rodriguez P, Bernal-Martinez L. et al. Clinical and Laboratory Development of Echinocandin Resistance in Candida glabrata: molecular Characterization. Front Microbiol 2019; 10: 1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Shields RK, Kline EG, Healey KR. et al. Spontaneous mutational frequency and FKS mutation rates vary by echinocandin agent against Candida glabrata. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e01692-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Castanheira M, Woosley LN, Messer SA. et al. Frequency of fks mutations among Candida glabrata isolates from a 10-year global collection of bloodstream infection isolates. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2014; 58: 577–80. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Perlin DS. Echinocandin resistance in candida. Clin Infect Dis 2015; 61 Suppl 6: S612–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Arendrup MC, Perlin DS, Jensen RH. et al. Differential in vivo activities of anidulafungin, caspofungin, and micafungin against Candida glabrata isolates with and without FKS resistance mutations. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2012; 56: 2435–42. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Healey KR, Katiyar SK, Castanheira M. et al. Candida glabrata mutants demonstrating paradoxical reduced caspofungin susceptibility but increased micafungin susceptibility. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2011; 55: 3947–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Arastehfar A, Daneshnia F, Zomorodian K. et al. Low level of antifungal resistance in iranian isolates of Candida glabrata recovered from blood samples in a multicenter study from 2015 to 2018 and potential prognostic values of genotyping and sequencing of PDR1. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 2019; 63: e02503-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Byun SA, Won EJ, Kim MN. et al. Multilocus Sequence Typing (MLST) genotypes of Candida glabrata bloodstream isolates in Korea: association with antifungal resistance, mutations in mismatch repair gene (Msh2), and clinical outcomes. Front Microbiol 2018; 9: 1523. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Beyda ND, John J, Kilic A. et al. FKS mutant Candida glabrata: risk factors and outcomes in patients with candidemia. Clin Infect Dis 2014; 59: 819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Arastehfar A, Daneshnia F, Salehi M. et al. Low level of antifungal resistance of Candida glabrata blood isolates in Turkey: fluconazole minimum inhibitory concentration and FKS mutations can predict therapeutic failure. Mycoses 2020; 63: 911–20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.