Abstract

Background

Health conditions perceived as contagious, dangerous, or incurable are associated with some facets of social stigma.

Methods

A cross-sectional survey was conducted from May 9, 2020 to June 9, 2020, among frontline healthcare workers (HCWs) in India to understand their perceived stigmatizing experiences (SE) and self-esteem during the COVID-19 pandemic. Google forms, an online forms tool, was used to create the survey, and samples were recruited through snowball sampling. Data comprised baseline characteristics of HCWs and their responses to the modified version of the Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale.

Results

Of the 600 participants (mean age: 30.9 ± 6.7 years), 76% comprised of nurses. Most participants were residing in urban areas and working in government sectors in clinical areas. Approximately 66.3% HCWs had at least 1 SE, and 51.7% reported a high impact of stigma (SI) across their various life domains, viz. quality of life, social contacts, self-esteem, and family relations, but 73% had normal self-esteem. The SI was more at the family level than at the individual level. The prevalence of SE (69.5% vs. 56.6%) and psychosocial SI (54.5% vs. 44.1%) was higher among nurses than among doctors. Being a nurse and working in clinical areas were statistically significant (P < 0.05 and < 0.01, respectively) for predicting SE likelihood.

Conclusion

Although HCWs have their own apprehensions, they do have high self-esteem and continue to deliver professional duties despite their SE. The government should frame guidelines to stop such discrimination and hail the saviors.

Keywords: COVID-19, Social stigma, Discrimination, Health care worker, Self-esteem

Introduction

Health conditions perceived as contagious, dangerous, or incurable are associated with some facets of societal stigma and discrimination. Stigma is a negative social experience of an individual or a group that operates at cognitive–behavioral or emotional levels and leads to social inequalities.1, 2, 3 The world is witnessing the wrath of a dreadful pandemic wave from the novel coronavirus [severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS) coronavirus-2] infection, which was first reported in Wuhan City of Hubei Province, China, on December 31, 2019.4 This pandemic has now affected every continent, with a sizable share of COVID-19 cases being reported from India. India reported its first case on January 30, 2020, and thereafter, an exponential surge has been observed in the number of infected cases and deaths.

In this ongoing war against the pandemic, healthcare workers (HCWs) are frontline warriors who endure multiple stressors due to increased professional demands amidst adverse working conditions. Obviously, they expect support from the public. On the contrary, incidences of negative public attitudes toward these esteem groups have been reported in our country. Moreover, they have been exposed to prejudices and stereotyped behaviors and have been labeled as potential carriers of COVID-19 even when they provide care to those infected.5,6 This has resulted in emotional turmoil, with HCWs developing conflicting thoughts as they face tremendous challenges in balancing their personal and professional roles.7 Such impermissible gestures from the society may have severe repercussions on the work quality, morale, and contentment of HCWs while delivering professional responsibility and, ultimately, their quality of life and psychological wellbeing in this crisis.8

Some reports have confirmed increased psychological distress amongst HCWs.9,10 The World Health Organization (WHO) had also expressed worry about the stigma faced by HCWs in its bulletin.11 Ramaci et al documented outcomes of stigmatizing attitudes toward HCWs in Italy.12 A perception of stigmatizing behavior also exists in our country, as highlighted by some authors.13,14 However, these authors had presented this information through correspondence or opinion papers, which need validation, and the number of such relevant papers are few.

Hence, we aim to document perceived stigmatizing experiences (SE) and their impact on various life domains among HCWs during this COVID-19 pandemic in India.

Materials and methods

Study design

A cross-sectional online survey was conducted from May 9, 2020 to June 9, 2020 among HCWs in India to understand their perceived SE and self-esteem during the COVID-19 pandemic. An expedited ethical approval was taken from the institutional ethics committee (IEC Ref No: T/IM-NF/Nursing/20/04 dated 08/05/2020).

Study participants

The study participants consisted of HCWs of either sex belonging to frontline strata consisting of doctors and nurses who were directly involved or likely to be involved in the near future for COVID-19 patient care. HCWs working in government or private hospitals in India who volunteered to participate in this online survey were included. The survey was conducted in English.

Sampling technique and sample size

For creating an unbiased sampling environment for the study, an exponential snowball sampling was used to recruit participants. The sample size was calculated using open-epi software.15 Considering approximately 20 lakh HCWs and a hypothesized percentage of outcome in population as 50% at 5% absolute precision, the sample size was determined to be 577.16 Stratification was performed on the basis of an average institutional doctor: nurse ratio of 1:5 for the HCWs.

Study variables and instruments

The survey collected demographic data and data regarding SE, SI, and self-esteem. The demographic details included baseline characteristics of the participants, that is, age, gender, marital status, occupation, place of residence, type of residence, type of workplace, years of experience, and involvement in COVID-19 patient care (presently involved or likely to be involved in future). The study tools included a modified version of the Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences (ISE), originally developed by Stuart et al,17 and the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale (R-SES), which was developed by Rosenberg.18 These tools were used to collect data about SE and self-esteem. The permission to use these tools was obtained from the respective authors.

Inventory of Stigmatizing Experiences (ISE) was first described by authors in 2005 to capture the range of SE and the impact of these experiences on individuals. ISE has two subscales, namely the Stigma Experience Scale (SES) and Stigma Impact Scale (SIS). The SES has 10 items that measure the prevalence and frequency of SE. The first two items on SES are scored on a 5-point rating scale and the next eight items are scored on a 3-point scale. All items need to be recoded into a binary variable of yes or no with a scoring of 1 and 0, where 1 reflects a high expectation of stigma and 0 reflects no or low expectations of stigma. The scores were summed across all items to get the index score. The SIS assesses the intensity of the psychosocial impact of stigma on an individual and their family across various life domains, viz. quality of life, family relationships, social contacts, and self-esteem. The responders need to rate the stigma impact (SI) on a 10-point Likert scale for all the seven items; on this scale, a score of 0 denotes no impact, and a score of 10 denotes the highest possible impact. Again, the scores were summoned to get the cumulative impact. The scales were modified with due permission to suit the current stigma context (Fig. 1). The R-SES, which was the second tool, is widely used to evaluate individual self-esteem. It is also a 10-item scale with items to be answered on a 4-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agrees to strongly disagree. Agreement with positively worded items and disagreement with negatively worded items were given the highest scores from 4 to 1 for responses in each item. The cumulative scores give a comprehensive measure of self-esteem ranging from 0 to 40, where scores <15 may indicate low self-esteem. Both tools have established validity and reliability.17,18

Fig. 1.

A modified version of inventory of stigmatizing experiences (changed with permission from original author).

Data collection

A cross-sectional study of HCWs was conducted by using Google forms, an online forms tool (Microsoft office version 10, Chicago, USA), to create the survey. The online link for survey participation was first disseminated to a few key prospective participants along with text messages, and they were further motivated to pass it on to their peers through various social networking channels, viz. email, WhatsApp, and Facebook. Data collection was stopped once recruitment was complete. The survey link comprised a detailed information sheet for the study, an option to agree or disagree to participate in the survey, and the questionnaire. The filled responses for the survey questionnaire were updated in real-time in an MS Excel spreadsheet, which was later imported for analysis.

Statistical methods

Statistical analysis was performed using SPSS version 17 (Microsoft, Chicago, USA). Categorical variables are expressed as frequency and percentage. The normalcy of numerical variables was tested using the Kolmogorov–Smirnov test. Numerical variables are expressed as median with interquartile range (IQR) if non-parametric and as mean ± standard deviation if parametric. The Mann–Whitney U-test was used to compare subgroups in terms of self-esteem, SE, and SI. A binomial logistic regression was performed to ascertain the association of SE and SI with selected demographic variables. The Nagelkerke R2 test was used to assess the variance of the regression model. Odds ratio (OR) and adjusted OR were also applied to determine the likelihood of risk of SE and SI. All the tests were 2-tailed. P < 0.05 was regarded as statistically significant.

Results

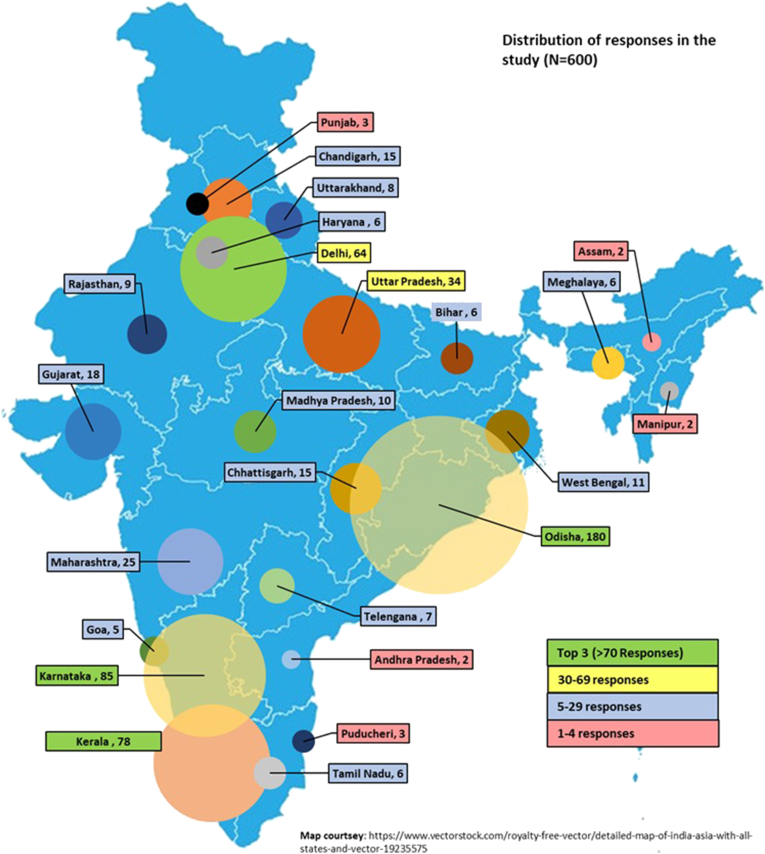

During the study period, 764 HCWs responded to the survey. After excluding those with missing data or incomplete responses, a total of 600 responses from various Indian states were considered for data analysis, as shown in Fig. 2.

Fig. 2.

Bubble chart depicting the distribution of participants across the country.

Participant characteristics

The mean age of the participants was 30.9 ± 6.7 years. They were mostly men (54.3%), married (58.3%), residing in urban areas (77.5%), residing in rental apartments (59.3%), and residing with family (54.4%). The majority of our study participants were working in government hospitals (82.7%) and posted in clinical areas (86.5%) but were not yet involved in COVID-19 patient care (64.2%). The details are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Demographic variables of Healthcare workers (n = 600).

| Demographic variable | Frequency | Percentage (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Age (in years) | ||

| 20-29 | 262 | 43.7 |

| 30-39 | 280 | 46.7 |

| 40-49 | 43 | 7.2 |

| ≥50 | 15 | 2.5 |

| Gender | ||

| Male | 326 | 54.3 |

| Female | 274 | 45.7 |

| Marital status | ||

| Single | 250 | 41.7 |

| Married | 350 | 58.3 |

| Residing region | ||

| Urban | 465 | 77.5 |

| Rural | 135 | 22.5 |

| Residence | ||

| Rental | 356 | 59.3 |

| Own | 244 | 40.7 |

| Occupation | ||

| Doctor | 145 | 24.2 |

| Nurse | 455 | 75.8 |

| Years of experience | ||

| <2 | 161 | 26.8 |

| 2-5 | 210 | 35 |

| 5-10 | 177 | 29.5 |

| >10 | 52 | 8.7 |

| Living with | ||

| Not with family | 274 | 45.7 |

| Family | 326 | 54.4 |

| Area of work | ||

| Clinical | 519 | 86.5 |

| Non clinical | 81 | 13.5 |

| Caring for COVID-19 | ||

| Yes | 215 | 35.8 |

| No | 385 | 64.2 |

| Type of Health care facility | ||

| Government | 496 | 82.7 |

| Private | 104 | 17.3 |

SE of HCWs and its impact on HCWs

Approximately 66.3% of HCWs had at least1 SE, and 51.7% had reported a high SI, but 73% of the HCWs had normal self-esteem during the pandemic. The prevalence of SE (69.5% vs. 56.6%) and SI (54.5% vs. 44.1%) was significantly higher in nurses than in doctors (p < 0.01) as seen in Table 2. At the same time, HCWs who directly treated or cared COVID-19 patients had a higher SE compared to those who have not yet cared for COVID-19 patients (66.35 vs. 33.6%, p = 0.006). Fig. 3 depicts that SI was more at the family level than at the individual level across various life dimensions. At the individual level, the psychosocial SI was more on the self-esteem domain (41%), followed by family relations (39.7%) and quality of life (39.3%). HCWs who were directly involved in COVID-19 patient care had significantly higher SE than those who were not yet involved (P < 0.001).

Table 2.

Magnitude of Self-Esteem, Stigma Experience, and Impact among Health care workers.

| Outcomes | Range | IQR | Median | Overall (700) |

Nurses (455) |

Doctors (145) |

Z value† | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | ||||||

| Self Esteem | 16–40 | 28–34 | 30 | |||||

| Low(0–20) | 4 (0.6) | 2 (0.4) | 2 (1.4) | −1.65 | 0.09 | |||

| Normal (21–33) | 439 (73.2) | 341 (74.9) | 98 (67.6) | |||||

| High (34–40) | 157 (26.2) | 112 (24.6) | 45 (31.0) | |||||

| Stigma Impact | 0–70 | 11–46 | 31.5 | |||||

| Low Impact | 290 (48.3) | 209 (45.9) | 81 (55.9) | −2.90 | 0.004∗ | |||

| High Impact | 310 (51.7) | 246 (54.1) | 64 (44.1) | |||||

| Stigma Experience | 0–9 | 0–3 | 01 | |||||

| Not Experienced | 202 (33.6) | 139 (31.5) | 63 (43.4) | −1.87 | 0.06 | |||

| Experienced | 398 (66.3) | 316 (69.5) | 82 (56.6) |

∗p<0.05, † Mann Whitney U Test.

Fig. 3.

Level of Stigma Impact on various aspects of Life of Healthcare workers during COVID-19.

Determinants of SE and SI

The binomial logistic regression model was not statistically significant (P > 0.05) for SE (χ2 = 3.15) or SI (χ2 = 5.2). The model explained 5% of the variance (Nagelkerke R2) for both SE and SI. Of the 10 selected variables, being a nurse and working in clinical areas were statistically significant (P < 0.05 and < 0.01, respectively) for predicting the likelihood of SE. Female gender, being a doctor, and working in government hospitals were statistically significant (P < 0.05) for predicting the likelihood of SI on various psychosocial domains of the HCWs (Table 3). Doctors had 41% lower risk of odds (95% CI: 0.38–0.91) to have SE and 51% lower risk of odds (95% CI: 0.31–0.76) to have SI than nurses. HCWs working in clinical areas had 70% (95% CI: 1.03–2.80) higher odds of SE. Female HCWs had a 39% lower risk of odds (95% CI: 0.43–0.88) and HCWs working in government hospitals had a 46% lower risk of odds (95% CI: 0.33–0.88) to have psychosocial SI (Fig. 4).

Table 3.

Association of stigma experiences and stigma impact with selected socio-demographic variables (n = 600).

| Variables (Reference Variable) | Stigma Experience |

Stigma Impact |

||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| UOR† (95% CI) | AOR† (95% CI) | R2 | UOR† (95% CI) | AOR† (95% CI) | R2 | |

| Gender (Female) | 0.78 (0.63–1.25) | 0.76 (0.52–1.11) | 0.05 | 0.75 (0.54–1.03) | 0.61∗ (0.43–0.88) | 0.05 |

| Marital status (Married) | 0.91 (0.65–1.29) | 0.75 (0.44–1.28) | 1.09 (0.78–1.51) | 1.19 (0.72–1.97) | ||

| HCWs (Doctor) | 0.57∗ (0.39–0.84) | 0.59∗ (0.38–0.91) | 0.67∗ (0.46–0.97) | 0.49∗ (0.31–0.76) | ||

| Residence (Rented) | 1.02 (0.72–1.44) | 0.88 (0.60–1.31) | 1.002 (0.72–1.38) | 0.89 (0.61–1.29) | ||

| Institute (Government) | 1.49 (0.96–2.30) | 1.24 (0.76–2.02) | 0.71 (0.46–1.09) | 0.54∗(0.33–0.88) | ||

| Treating COVID-19 patients (Yes) | 1.67∗ (1.16–5.43) | 1.46 (0.99–2.15) | 1.25 (0.90–1.76) | 1.18 (0.83–1.69) | ||

| Age (<30 years) | 1.08 (0.77–1.52) | 1.01 (0.63–1.61) | 1.20 (0.87–1.65) | 1.56 (0.99–2.45) | ||

| Living with family (Yes) | 0.93 (0.66–1.31) | 1.23 (0.77–1.97) | 1.10 (0.79–1.51) | 1.28 (0.82–2.00) | ||

| Area working (Clinical) | 1.80 (1.12–2.90) | 1.70∗ (1.03–2.80) | 1.57 (0.97–2.52) | 1.54 (0.93–2.55) | ||

| Place of residence (Rural) | 1.21 (0.80–1.83) | 1.23 (0.78–1.92) | 0.87 (0.55–1.20) | 1.06 (0.70–1.60) | ||

†UOR: Unadjusted Odds ratio, AOR: Adjusted Odds ratio; HCWs: Health care workers.

∗p < 0.05, OR, AOR, and R2 was calculated using Binominal logistic regression.

Fig. 4.

Logistic regression results of AOR of Stigma Experience and Stigma Impact among Healthcare workers with predictors.

Discussion

HCWs are front liners in a pandemic who are risking their lives for the betterment of humanity. Yet, forgetting their sacrifices, people sometimes treat HCWs differently; they stigmatize and even outcaste these HCWs. This stigmatizing unfortunately happened during the outbreaks of Ebola and other infectious diseases such as tuberculosis and SARS; the HCWs were threatened and evicted, and their families’ attacked.19, 20, 21 The COVID-19 pandemic is no different. The psychosocial SI and SE may have long-lasting repercussions on the personal and professional work fronts of HCWs.

Nearly 90% of our HCWs were aged <40 years, reflecting professionally and socially the most active age groups. Again, most of them were from clinical areas of healthcare facilities, which inherently are associated with higher risk stigmatization.22 HCWs residing in rental houses and apartments have been given eviction notices and are publicly slammed and humiliated with discriminating attitudes.5,6,23 More than half of the HCWs were within 5 years of their service at their current healthcare facility, which indicated that they were new to that place and might not have been well acquainted with the local language and the public around their locality. This adds the risks of marginalization in a country of diverse regional and cultural disparities. These findings are in contrast to the demography of HCWs in a study in Italy, where most of the HCWs are aged >40 years and had a mean tenure of more than 13 years.12 We also had a nurse: doctor ratio of almost 4:1, which is opposite to what they studied.12

In the present study, 66.5% of the HCWs reported at least 1 SE after the COVID-19 outbreak. The SARS coronavirus-2 is highly contagious and has instigated overwhelming fear among the public. However, the frequency of SE reported was higher than that reported from Singapore and Taiwan during earlier SARS outbreaks.22,24 The prevalence of psychosocial SI was reported in almost 90% of the HCWs, with 51.7% HCWs reporting a high SI. The SI at the family level overwhelmed the SI at the individual level. This may be due to more likelihood of neighbors and public interactions from the family than by the HCWs who bear more professional and work demands during the pandemic. The HCWs share a dual responsibility of safeguarding their family and simultaneously delivering their professional duties, often with long working hours, deprived of loved ones during isolation. However, they maintain a high self-esteem, even concealing their own apprehensions and fear. SE is contagious, and the majority of our participants were living with their families. Therefore, these negative social gestures might have been perceived by the family of HCWs as a whole. Jung et al also found stigmatizing attitudes toward family members and even children of nurses who were caring for patients in hospitals during the Middle East Respiratory Syndrome Coronavirus (MERS-CoV) outbreak.25

At the individual level, the SI was more on the self-esteem of the HCWs, followed by family relations and quality of life, indicating major penetration into the psychosocial spheres of the HCWs. Zerbini et al and Que and co-workers also reported increased psychological distress and emotional outbursts among the frontline HCWs battling the COVID-19 pandemic, and these impacts of stigma downgrade their ability to cope with personal and work demands.9,10 Ramaci et al found that COVID-19-associated SE among the HCWs caused more fatigue and burnout, ultimately affecting outcomes.12 Corrigan et al also reported that HCWs who had SE had increased psychological distress and somatic symptoms.26 We found SE and SI were higher among nurses than among doctors. This was in congruence with the findings of a study by Zerbini et al, who reported that nurses experienced more psychosocial issues and lower work-related fulfillment than their doctors while serving at COVID-19 hospitals.9 This may be due to the public perception that nurses have to work in close contact with infected persons for longer hours than doctors. Social status discrimination is also evidently higher (doctors vs. nurses) in the Indian culture, which could be another factor that makes the nurse an easy target. Ramaci et al did not find any differences in measured variables among the doctors and nurses.12

Among the various confounders, working in clinical areas was associated with a higher prevalence of SE. The SE on HCWs is pervasive, irrespective of their involvement in COVID-19 care. However, a higher SE was found among those who directly cared or treated COVID-19 patients, as against those who were not directly cared or treated COVID-19 patients. Bai et al also reported stigmatizing attitudes toward HCWs who upfront cared for SARS victims.24 Interestingly, Wang et al found that of the 138 COVID-19 patients being treated, 29% of the patients were HCWs who were mostly working in clinical areas (general wards: 77.5%, emergency department: 17.5%, and intensive care unit: 5%).27 Thus, HCWs involved in COVID-19 patient care endure more adverse psychosocial outcomes, fueling lasting mental health consequences from these negative social gestures.28,29

Another interesting finding in our study is that female HCWs had lower SI than their male counterparts. Women in Indian culture ought to be strong and gifted with tremendous capacity to handle any crisis as they fulfill multiple roles in their professional and family life. Thus, the SE might not have instilled much SI among female HCWs. This is in contrast to the findings of the European study by Ramaci et al, where fatigue and burnout were higher in women than in men, which thus affected outcomes.12 In their meta-analysis, Kisley et al found that HCWs of younger age and female gender (particularly with dependent parents or children) were more vulnerable to psychological distress.29 Regression results also revealed that being a doctor and working in government hospitals are associated with a lower psychosocial SI. HCWs in government sectors are more secure and privileged in the public view and are expected to carry the immense workload of pandemic outbreaks such as COVID-19. They might have resisted the severe psychosocial impact of stigmatizing behaviors. In the present study, most participants reported normal or high self-esteem during the COVID-19 pandemic, which is very encouraging. Studies have also suggested that doctors and nurses reported strong feelings of commitment and professional responsibilities to serve their clients during earlier infectious disease outbreaks despite adverse psychosocial circumstances.30

The present study has some limitations that are worth acknowledging. The study was cross-sectional, so the psychosocial impact would have skewed toward the current state rather than the actual SE. This was an online survey, which would have refrained some prospective participants from providing their responses. Because the survey was conducted at an early stage of the COVID-19 pandemic, there were few infected HCWs among the participants. As the disease gained momentum, more HCWs became infected and thus may have higher SE. We did not investigate work fatigue, burnout, and satisfaction in our study. The strength being, a first of its kind study in a country with a large population and with every state resembling a small nation with diverse social and cultural values.

Conclusion

COVID-19 has led to a global standstill and filled everyone with anxiety, fear, and uncertainty, including HCWs. Despite their apprehensions, HCWs do have a high self-esteem and continue to deliver professional duties despite their SE. Through various means, government should frame guidelines to stop the discriminating attitude of the public toward HCWs and hail these saviors.

Disclosure of competing interest

The authors have none to declare.

Acknowledgements

The authors are thankful to Dr. Roumen Milev and Dr. Florence Rosenberg for giving permission to use ISE and R-SES scales. The authors are pleased to acknowledge Dr. Ranjan Das, (MBBS, MMST IIT Kharagpur) for designing the bubble chart. The authors are also grateful to all HCWs who filled the forms for the study.

References

- 1.Hatzenbuehler M.L., Phelan J.C., Link B.G. Stigma as a fundamental cause of population health inequalities. Am J Public Health. 2013 May;103(5):813–821. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2012.301069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Goffman E. First Touc. New York:Simon&Schuste; 1986. Stigma : Notes on the Management of Spoiled Identity. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Parker R., Aggleton P. HIV and AIDS-related stigma and discrimination: a conceptual frame work and implications for action. Soc Sci Med. 2003;57(1):13–24. doi: 10.1016/s0277-9536(02)00304-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Page J., Fan W., Khan N. The Wall Street Journal; 2020. How it All Started: China's Early Coronavirus Missteps.https://www.wsj.com/articles/how-it-all-started-chinas-early-coronavirus-missteps- 11583508932 [cited 2020 Jul 9]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 5.Perappadan B. The Hindu; 2020. Medical Staff Treating COVID-19 Patients Told to Vacate Homes.https://www.thehindu.com/news/cities/Delhi/medical-staff-treating-covid-19-patientstold-to-vacate-homes/article31156966.ece [cited 2020 Jul 9]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sharma N. Quartz India; 2020. Stigma: the other enemy India's overworked doctors face in the battle against Covid-19.https://qz.com/india/1824866/indian-doctors-fighting-coronavirus-now-face-socialstigma/ [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 9]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cabarkapa S., Nadjidai S.E., Murgier J., Ng C.H. The psychological impact of COVID-19 and other viral epidemics on frontline healthcare workers and ways to address it: a rapid systematic review. Brain Behav Immun Health. 2020 Oct;8:100144. doi: 10.1016/j.bbih.2020.100144. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Jacob J., VR V., Issac A. Factors associated with psychological outcomes among frontline healthcare providers of India during COVID-19 pandemic. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Dec 25;55:102531. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zerbini G., Ebigbo A., Reicherts P., Kunz M., Messman H. Psychosocial burden of healthcare professionals in times of covid-19 – a survey conducted at the university hospital augsburg. GMS Ger Med Sci. 2020;18:1–9. doi: 10.3205/000281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Que J., Shi L., Deng J. Psychological impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on healthcare workers: a cross-sectional study in China. Gen Psychiatry. 2020;33(3) doi: 10.1136/gpsych-2020-100259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Attacks on Health Care in the Context of COVID-19 [Internet]. [cited 2020 Nov 2]. Available from: https://www.who.int/news-room/feature-stories/detail/attacks-on-health-care-in-the-context-of-covid-19.

- 12.Ramaci T., Barattucci M., Ledda C., Rapisarda V. Social stigma during COVID-19 and its impact on HCWs outcomes. Sustain. 2020;12(9):1–13. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singh R., Subedi M. COVID-19 and stigma: social discrimination towards frontline healthcare providers and COVID-19 recovered patients in Nepal. Asian J Psychiatr. 2020 Jun 13;53:102222. doi: 10.1016/j.ajp.2020.102222. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Bagcchi S. Stigma during the COVID-19 pandemic. Lancet Infect Dis. 2020 Jul;20(7):782. doi: 10.1016/S1473-3099(20)30498-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dean A, Sullivan K, Soe M. Open Epi: open Source Epidemiologic Statistics for Public Health, Version. [Internet]. [cited 2020 Jul 9]. Available from: https://www.openepi.com/Menu/OE_Menu.htm.

- 16.Anand S., Fan V. World Health Organization; Geneva: 2016. The Health Workforce in India.https://www.who.int/hrh/resources/16058health_workforce_India.pdf (Human Resources for Health Observer Series No. 16). pdf. [cited 2020 Oct 30]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stuart H., Miley R., Koller M. The inventory of stigmatizing experiences: its development and reliability. World Psychiatr. 2005;4(S1):33–37. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Shapurian R., Hojat M., Nayerahmadi H. Psychometric characteristics and dimensionality of a Persian version of Rosenberg self-esteem scale. Percept Mot Skills. 1987;65(1):27–34. doi: 10.2466/pms.1987.65.1.27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Chang S.H., Cataldo J.K. A systematic review of global cultural variations in knowledge, attitudes and health responses to tuberculosis stigma. Int J Tuberc Lung Dis. 2014;18(2):168–173. doi: 10.5588/ijtld.13.0181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Lin E.C.L., Peng Y.C., Hung Tsai J.C. Lessons learned from the anti-SARS quarantine experience in a hospital-based fever screening station in Taiwan. Am J Infect Control. 2010;38(4):302–307. doi: 10.1016/j.ajic.2009.09.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hall R.C.W., Hall R.C.W., Chapman M.J. The 1995 Kikwit Ebola outbreak: lessons hospitals and physicians can apply to future viral epidemics. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. 2008;30(5):446–452. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2008.05.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Verma S., Mythily S., Chan Y.H., Deslypere J.P., Teo E.K., Chong S.A. Post-SARS psychological morbidity and stigma among general practitioners and traditional Chinese medicine practitioners in Singapore. Ann Acad Med Singapore. 2004;33(6):743–748. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mohapatra D. The Times of India; 2020 Mar 29. Doctor in Odisha Asked to Vacate Flat, Threatened with Rape over Covid-19 Fear.https://timesofindia.indiatimes.com/city/bhubaneswar/doctor-in-odisha-asked-to-vacateflat-threatened-with-rape-over-covid-19-fear/articleshow/74879135.cms [Internet] Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 24.Bai Y.M., Lin C.C., Lin C.Y., Chen J.Y., Chue C.M., Chou P. Survey of stress reactions among health care workers involved with the SARS outbreak. Psychiatr Serv. 2004;55(9):1055–1057. doi: 10.1176/appi.ps.55.9.1055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Jung W., Cho H. The Kyunghyang Shinmun; 2015. Punishment when Refused to Attend School of Child with Medical Staff Parents Caring MERS-CoV Infection Patients.http://news.khan.co.kr/kh_news/khan_art_view.html?artid=%0A201506212253315&code=940100 [Internet] [cited 2020 Jul 15]. Available from: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Corrigan P.W., Bink A.B., Schmidt A., Jones N., Rüsch N. What is the impact of self stigma? Loss of self-respect and the “why try” effect. J Ment Heal. 2016;25(1):10–15. doi: 10.3109/09638237.2015.1021902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wang D., Hu B., Hu C. Clinical characteristics of 138 hospitalized patients with 2019 novel coronavirus–infected pneumonia in Wuhan, China. J Am Med Assoc. 2020;323(11):1061–1069. doi: 10.1001/jama.2020.1585. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lai J., Ma S., Wang Y. Factors associated with mental health outcomes among health care workers exposed to coronavirus disease 2019. JAMA Netw open. 2020;3(3) doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.3976. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kisely S., Warren N., McMahon L., Dalais C., Henry I., Siskind D. Occurrence, prevention, and management of the psychological effects of emerging virus outbreaks on healthcare workers: rapid review and meta-analysis. BMJ. 2020;369:m1642. doi: 10.1136/bmj.m1642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Wong E.L.Y., Wong S.Y.S., Lee N., Cheung A., Griffiths S. Healthcare workers' duty concerns of working in the isolation ward during the novel H1N1 pandemic. J Clin Nurs. 2012;21(9–10):1466–1475. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2702.2011.03783.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]