Highlights

-

•

32%-35% of participants experienced food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic.

-

•

Barriers to getting food included insufficient money and fear of COVID-19 exposure.

-

•

Financial struggles due to COVID-19 is an important predictor of food insecurity.

-

•

SNAP receipt buffered the harmful effect of financial struggles on food security.

Keywords: COVID-19, Food Insecurity, Federal Nutrition Assistance, Health Policy

Abstract

The COVID-19 pandemic has considerably increased food insecurity. To identify where intervention and policy solutions are most needed, we explored barriers to obtaining food and predictors of experiencing food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic. Between May and July 2020, we conducted cross-sectional online surveys with two convenience samples of U.S. adults (Study 1: n = 2,219, Study 2: n = 810). Roughly one-third of participants reported experiencing food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 1: 32%, Study 2: 35%). Between one-third and half reported using the charitable food system (Study 1: 36%, Study 2: 46%). The majority of participants experienced barriers to getting food (Study 1: 84%, Study 2: 88%), of which the most commonly reported were not having enough money to buy food (Study 1: 48%; Study 2: 53%) and worrying about getting COVID-19 at the store (Study 1: 50%; Study 2: 43%). Higher education was associated with greater risk of food insecurity in both studies (all p < 0.05). Receipt of aid from SNAP buffered against the association between financial struggles and food insecurity in Study 1 (p = 0.03); there was also some evidence of this effect in Study 2 (p = 0.05). Our findings suggest that food insecurity might be reduced by mitigating financial struggles (e.g., by increasing access to SNAP) and by addressing barriers to obtaining food (e.g., by expanding accessibility of food delivery programs).

1. Introduction

Food insecurity, or uncertain access to adequate food (U.S. Department of Agriculture – Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS), 2020), is a pressing public health problem. Food insecurity disproportionately affects low-income families and people of color (Coleman-Jensen, 2020), and is associated with a higher probability of chronic disease including cardiovascular disease, hypertension, stroke, cancer, asthma, diabetes, and arthritis (Gregory, 2017, Gundersen and Ziliak, 2015, Vercammen et al., 2019). Before the COVID-19 pandemic, roughly 11% of United States (U.S.) households were classified as food insecure (Coleman-Jensen, 2020). However, since the COVID-19 pandemic began to affect the U.S. in March 2020, the prevalence of food insecurity increased. By the late spring and early summer of 2020, estimates of food insecurity prevalence within the overall population ranged between 18% and 35% (Bauer, 2020, Bitler et al., 2020, Karpman et al., 2020b, Kent et al., 2020, Niles et al., 2020, Owens et al., 2020, Schanzenbach and Pitts, 2020, Waxman et al., 2020), and were even higher among individuals who lost their job (Ahn and Norwood, 2021, Karpman et al., 2020b, Niles et al., 2020, Waxman et al., 2020), lost income (Karpman et al., 2020b, Kent et al., 2020), were classified as low-income (Karpman et al., 2020a, Waxman et al., 2020, Wolfson and Leung, 2020), or have children (Ahn and Norwood, 2021, Karpman et al., 2020a, Kent et al., 2020, Bauer, 2020, Bitler et al., 2020, Schanzenbach and Pitts, 2020, Waxman et al., 2020). Moreover, 31% of adults reported a necessary reduction in money spent on food between March and May of 2020 because of the COVID-19 pandemic (Karpman et al., 2020b), and more than half of respondents in the U.S. Census Household Pulse Survey, a survey of household-level experiences during the COVID-19 pandemic, reported they were not very confident in their ability to afford the food they needed in the next month (Bitler et al., 2020).

Intervention and policy solutions are needed to address food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic, which could persist for several years (Scudellari, 2020). Identifying the barriers to food security due to the COVID-19 pandemic may highlight general barriers to food security that arise during times of crisis (e.g., global pandemics, natural disasters, financial crises) and inform policy for future potential shocks to social, economic, and environmental systems. Research on pandemic-specific predictors of food insecurity can inform these interventions and policy solutions. Prior to the pandemic beginning in the U.S. in March 2020, lower household income, high local food prices, and lower educational attainment consistently predicted food insecurity (Gundersen and Ziliak, 2018). However, with elevated food insecurity, additional factors may be playing an increasingly prominent role. Thus, we aimed to examine the barriers to obtaining food and the predictors of experiencing food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic using two national surveys of U.S. adults.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

Participants came from two parent studies that recruited convenience samples of U.S. adults (ages 18 and older). In Study 1, we recruited 2,219 adults between May and July 2020 through two opt-in panel research companies (Kantar and CloudResearch’s Prime Panels) for a study on beverage purchasing behavior. Across both panels, 13,965 people started the screener, 4,353 consented to the study, and 2,219 (51% of those who consented) completed the study. Participants were parents of children between the ages 1–5 (MGH, unpublished results). In Study 2, we recruited 810 adults in May 2020 through a third opt-in panel research company (Qualtrics Online Panel) for a study on the impact of Covid-19 health warnings related to tobacco use. For this study, 948 people started the screener and 810 consented to and completed the study (85%). Participants were current smokers, e-cigarette users, or dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes (Grummon et al., 2020). The companies notified existing panel members either by email or other electronic means that a survey was available, or by recruiting through other companies that require participants to access surveys through online hubs.

2.2. Procedures

In both studies, participants completed a survey online. They provided informed consent, answered questions as part of their respective parent study, and then answered questions about food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic and personal characteristics. After completing the survey, participants received incentives in a type and amount set by the survey vendor (e.g., a small cash or points system reward). Incentive amounts varied depending on the panel company. One panel company, Kantar, estimated that the dollar-equivalent value for the incentive was approximately $3; the other companies were unable to provide estimates for the incentive. The University of North Carolina Institutional Review Board approved procedures for both studies.

2.3. Measures

In both studies, the primary outcome was food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic (termed pandemic food insecurity). We developed survey items on pandemic food insecurity, defined as not having access to a sufficient quantity and quality of food as a result of the COVID-19 pandemic. We chose to assess food insecurity specifically due to the COVID-19 pandemic to uncover experiences of food insecurity that may be unique to the constellation of disruptions in grocery shopping, work, social networks, and childcare. We assessed pandemic food insecurity using three questions modeled after the USDA six-item Food Security Survey (Bickel et al., 2000) (Supplementary Table 1). This brief form allowed us to minimize survey length and participant burden. Several food insecurity and survey design experts reviewed the questions and deemed them to have high face validity. The items read: “In the last two months, how often were you unable to eat balanced meals because of the COVID-19 pandemic?”, “In the last 2 months, how often did you eat less than you wanted because of the COVID-19 pandemic?”, and “In the last 2 months, how often did you worry that you would not have enough food because of the COVID-19 pandemic?”. The response scale was “Never”, “Rarely”, “Sometimes”, “Often”, or “All the time”. We then created a dichotomous outcome representing whether participants experienced food insecurity (i.e., answered “Sometimes”, “Often”, or “All the time” to each of the three questions).

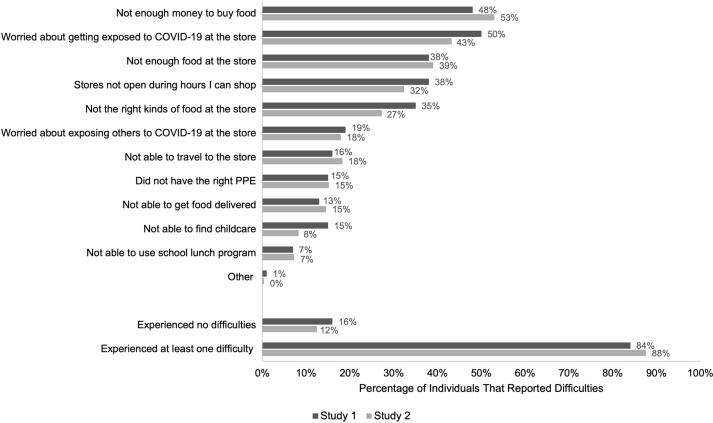

The survey assessed barriers to getting enough food with the question: “Some people are having difficulty getting enough food or the right kinds of food because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Which of the following difficulties getting food have you experienced?” We created response options (Fig. 1; Supplementary Table 2) based on a review of the peer-reviewed and grey literature between March and May of 2020 (Farmer, 2020, Karpman et al., 2020a, NORC at the University of Chicago, 2020, Schlanger, 2020, Feeding America, 2020, Ziady, 2020), with a fill in the blank option for any barriers not listed.

Fig. 1.

Reasons for difficulties getting food during the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 1, n = 2,179; Study 2, n = 810).

The survey also measured potential predictors of pandemic food insecurity including employment changes due to COVID-19, government benefits received (e.g., SNAP, WIC, unemployment), number of children in the household, and financial struggles due to COVID-19. The survey assessed financial struggles due to COVID-19 with a new item created by our team: “How much are you struggling financially due to the COVID-19 pandemic?” with 5 response options ranging from “Not at all” to “A great deal”. The survey measured standard demographics including age, gender identity, race, ethnicity, education, and household income. Exact item wording for survey measures appears in Supplementary Table 2.

2.4. Statistical analysis

We examined correlates of pandemic food insecurity with a single multivariable logistic regression, using all participants with complete data on each predictor (Study 1: n = 2,152 (97% of all participants); Study 2: n = 795 (98% of all participants)). For ease of interpretation, we report average marginal effects (AME) (i.e., differences in predicted probabilities) for the correlates, using the observed values for each participant to compute predicted probabilities (Williams, 2012). Analyses showed no variance inflation factors above 3.77, indicating no harmful multicollinearity. We also explored whether self-reported receipt of aid from SNAP or WIC moderated the association between financial struggles due to COVID-19 and pandemic food insecurity, given that these programs could help to buffer against the negative effects of financial challenges and can reduce food insecurity (Barrett, 2002, Bleich et al., 2020, DePolt et al., 2009, Gundersen and Ziliak, 2018, Keith-Jennings et al., 2019). We included two interaction terms in the logistic regression model for both interactions between financial struggles and SNAP receipt and financial struggles and WIC receipt, only retaining interaction terms that were statistically significant in either study in the final model. For interactions included in the final model, we calculated average marginal effects at both levels of the moderator.

Analyses used Stata MP version 16.1 (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX). Statistical tests were two-tailed and used a critical alpha of 0.05. Prior to data collection, we pre-registered the sample size and analysis plan for Study 1 (https://aspredicted.org/274x7.pdf) and Study 2 (https://aspredicted.org/jf9ds.pdf). Changes from this plan include: creating a dichotomous variable (food insecure: yes/no) to measure food insecurity rather than creating a scale, excluding four proposed correlates from the model for parsimony, and plotting and interpreting an interaction term with p = 0.05 (rather than p < 0.05) as described further in the results section.

3. Results

3.1. Participants

In Study 1, participants’ average age was 34.8 years, 71% were white, 21% were Black, and 33% identified as Hispanic or Latino/a (Table 1). One-third (33%) had an annual household income less than $50,000 per year. Over one-third (36%) of participants reported obtaining food from the charitable food system (e.g., food bank, church, or other places providing free food) in the past two months. In Study 2, participants’ average age was 41.9 years, 77% were white, 12% were Black, and 10% identified as Hispanic or Latino/a. Approximately half (49%) had an annual household income less than $50,000 per year. Nearly half (46%) of participants reported obtaining food from the charitable food system in the past two months. Study 2 participants came from all four U.S. Census regions (U.S. Census Bureau, 2010) (Study 1 participants did not report state of residence). One-third of participants reported experiencing food insecurity in the last two months due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 1: 32%; Study 2: 35%; Table 1). Extended participant characteristics can be found in Supplementary Table 3 and the percent of participants that experienced pandemic food insecurity by participant characteristics can be found in Supplementary Table 4.

Table 1.

Participant characteristics in Study 1, conducted May-July 2020, and Study 2, conducted May 2020.

| Characteristic |

Study 1 (n = 2,219) |

Study 2 (n = 810) |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| n | % | n | % | |

| Participant | ||||

| Experienced pandemic food insecurity | 697 | 32% | 283 | 35% |

| Mean age (SD) | 34.8 | (7.6) | 41.9 | (14.6) |

| Gender identity | ||||

| Man | 768 | 35% | 365 | 45% |

| Woman | 1,402 | 65% | 430 | 53% |

| Neither or prefer to self-describe | 1 | 0% | 13 | 2% |

| Hispanic or Latino/a | 735 | 33% | 81 | 10% |

| Race | ||||

| White | 1,571 | 71% | 620 | 77% |

| Black or African American | 472 | 21% | 97 | 12% |

| Other or multiracial | 176 | 8% | 93 | 11% |

| Education | ||||

| Less than a 4-year college degree | 743 | 34% | 509 | 63% |

| 4-year college degree or more | 1,428 | 66% | 301 | 37% |

| Loss of employment due to the COVID-19 pandemic | 1,150 | 53% | 486 | 60% |

| Financial struggle due to the COVID-19 pandemic | ||||

| Not at all | 570 | 26% | 143 | 18% |

| Very little | 518 | 24% | 173 | 21% |

| Somewhat | 579 | 27% | 238 | 29% |

| Quite a bit | 305 | 14% | 136 | 17% |

| A great deal | 197 | 9% | 118 | 15% |

| Obtained food from the charitable food system in past 2 months | ||||

| Never | 1,384 | 64% | 441 | 54% |

| Once | 165 | 8% | 76 | 9% |

| 2–4 times | 340 | 16% | 171 | 21% |

| 5–9 times | 209 | 10% | 80 | 10% |

| 10 or more times | 79 | 4% | 42 | 5% |

| Government benefit receipt in the last 2 months | ||||

| Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program (SNAP) | 426 | 19% | 236 | 29% |

| Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children (WIC) | 281 | 13% | 84 | 10% |

| Unemployment | 293 | 13% | 120 | 15% |

| COVID payment/stimulus | 465 | 21% | 200 | 25% |

| Temporary Assistance for Needy Families (TANF) | 51 | 2% | 10 | 1% |

| Other | 24 | 1% | 35 | 4% |

| None of the above | 1,131 | 51% | 319 | 39% |

| Household | ||||

| Household income ≤ 150% of U.S. Federal Poverty Level | 480 | 22% | 236 | 29% |

| Household income, annual | ||||

| $0-$49,999 | 713 | 33% | 395 | 49% |

| $50,000+ | 1,450 | 67% | 415 | 51% |

| At least one child in household | 2,167 | 100% | 417 | 51% |

| Census region of household | ||||

| Northeast | – | – | 180 | 23% |

| Midwest | – | – | 134 | 17% |

| South | – | – | 322 | 41% |

| West | – | – | 155 | 20% |

Note. SD, standard deviation. Missing demographic data ranged from 0.00% to 2.52%. -- Not assessed. Loss of employment due to the COVID-19 pandemic was defined as reporting “Been scheduled to work fewer hours”, “Taken unpaid time off”, “Had your wages or salary reduced”, “Been furloughed”, or “Been laid off” because of the COVID-19 pandemic. Experiencing pandemic food insecurity was defined as answering “Sometimes”, “Often”, or “All the time” to each of the three pandemic food insecurity questions. We examined the proportion of households with household income ≤ 150% of the U.S. Federal Poverty Level (FPL) because this cutoff is similar to cutoffs for eligibility to participate in many assistance programs (e.g., the federal cutoff for SNAP is 130% FPL1 the federal cutoff for WIC is 185% FPL2). Participants in Study 1 did not report their state of residence.

1 SNAP - Fiscal Year 2021 Cost of Living Adjustments (Policy Memo No. FNS-GD-2020-0133), 2020. USDA-FNS.

2 WIC 2021–2022 Income Eligibility Guidelines (Policy Memo No. FNS-GD-2021-0025), 2021. USDA-FNS.

3.2. Barriers to getting food

Most participants reported at least one barrier to getting food due to the COVID-19 pandemic (Study 1: 84%; Study 2: 88%; Fig. 1). The most commonly reported barriers were not having enough money to buy food (Study 1: 48%; Study 2: 53%), worrying about getting COVID-19 at the store (Study 1: 50%; Study 2: 43%), stores not having enough food (Study 1: 38%; Study 2: 39%), stores not open during the hours participants could shop (Study 1: 38%; Study 2: 32%), and stores not having the right kinds of food (Study 1: 35%; Study 2: 27%). A substantial proportion of participants also reported that they were worried about giving COVID-19 to others at the store (Study 1: 19%; Study 2: 18%), were unable to travel to the store (Study 1: 16%; Study 2: 18%), did not have the right personal protective equipment (PPE) (Study 1: 15%; Study 2: 15%), or were not able to get food delivered (Study 1: 13%; Study 2: 15%).

3.3. Correlates of pandemic food insecurity

Bivariate associations between each variable and food insecurity can be found in Supplementary Table 4. Multivariable analyses found that in both studies, those with a 4-year college degree or more were more likely to experience pandemic food insecurity, compared to participants with less than a college degree (Study 1: p = 0.001; Study 2: p = 0.002; Table 2).

Table 2.

Correlates of pandemic food insecurity.

| Study 1 (n = 2,152) |

Study 2 (n = 795) |

|||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| OR | Adjusted Average Marginal Effect (Difference in Predicted Probability) | p | OR | Adjusted Average Marginal Effect (Difference in Predicted Probability) | p | |

| COVID-19 related factors | ||||||

| Financial struggles due to COVID-19 | 2.67 | N/A | <0.001 | 2.14 | N/A | 0.02 |

| Government benefits (past 2 months) | ||||||

| SNAP | ||||||

| Did not receive aid (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Received aid | 2.90 | N/A | 0.01 | 3.68 | N/A | <0.001 |

| Financial struggles due to COVID-19 X SNAP Interaction | 0.78 | N/A | 0.03 | 0.74 | N/A | 0.05 |

| Other government benefits (past 2 months) | ||||||

| WIC | ||||||

| Did not receive aid (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Received aid | 1.52 | 0.07 | 0.01 | 1.66 | 0.09 | 0.09 |

| Unemployment | ||||||

| Did not receive aid (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Received aid | 0.67 | −0.06 | 0.01 | 1.36 | 0.05 | 0.21 |

| COVID payment/stimulus | ||||||

| Did not receive aid (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Received aid | 1.17 | 0.03 | 0.22 | 0.75 | −0.05 | 0.16 |

| Employment changes due to COVID-19 | ||||||

| Did not change (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Lost employment | 0.83 | −0.03 | 0.12 | 1.06 | 0.01 | 0.79 |

| Demographic characteristics | ||||||

| Age | 0.94 | −0.01 | 0.44 | 0.79 | −0.04 | 0.001 |

| Gender identity | ||||||

| Male (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Female | 0.64 | −0.07 | <0.001 | 0.89 | −0.02 | 0.53 |

| Neither or prefer to self-describea | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A | N/A |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Not Hispanic/Latino (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Hispanic/Latino | 1.61 | 0.08 | <0.001 | 1.34 | 0.05 | 0.33 |

| Race | ||||||

| White (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Black or African American | 0.92 | −0.01 | 0.53 | 0.64 | −0.07 | 0.10 |

| Other or multiracial | 0.92 | −0.01 | 0.67 | 0.89 | −0.02 | 0.68 |

| Children in household | ||||||

| 0 children | N/A | N/A | N/A | 0.83 | −0.03 | 0.56 |

| 1 child | 1.02 | 0.00 | 0.92 | 1.40 | 0.06 | 0.31 |

| 2 children | 0.96 | −0.01 | 0.77 | 0.75 | −0.05 | 0.37 |

| 3 + children (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| Education | ||||||

| Less than a college degree (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| 4-year college degree or higher | 1.49 | 0.06 | 0.001 | 1.91 | 0.11 | 0.002 |

| Household income, annual | ||||||

| <$50,000 (ref) | – | – | – | – | – | – |

| ≥$50,000 | 1.00 | 0.00 | 0.99 | 1.44 | 0.06 | 0.08 |

Note. Results presented in this table are from a multivariable logistic regression model which included the interaction term for SNAP and financial struggles. Average Marginal Effect (AME) is the difference in average predicted probability of being food insecure between the group of interest and the referent group, expressed as a proportion (e.g., an AME of + 0.05 indicates a 5 percentage point difference in predicted probabilities). P-values are associated with AMEs, unless AMEs listed as N/A. N/A, Not Applicable. SNAP, Supplemental Nutrition Assistance Program; WIC, Special Supplemental Nutrition Program for Women, Infants, and Children. Multivariable analysis included all variables in the table. Boldface indicates statistical significance (p < 0.05). Analyses exclude 67 participants from Study 1 and 16 participants from Study 2 due to missing data.

Results for the gender category “Neither or prefer not to say” are suppressed due to small cell size of participants.

In Study 1 only, receipt of WIC in the past two months (p = 0.01) and Hispanic or Latino/a ethnicity (p < 0.001) were associated with a higher probability of experiencing pandemic food insecurity. Also in Study 1, female gender (p < 0.001) and receipt of unemployment benefits in the past two months (p = 0.01) were associated with a lower probability of experiencing pandemic food insecurity. In Study 2 only, older age was associated with a lower probability of experiencing pandemic food insecurity (p = 0.001).

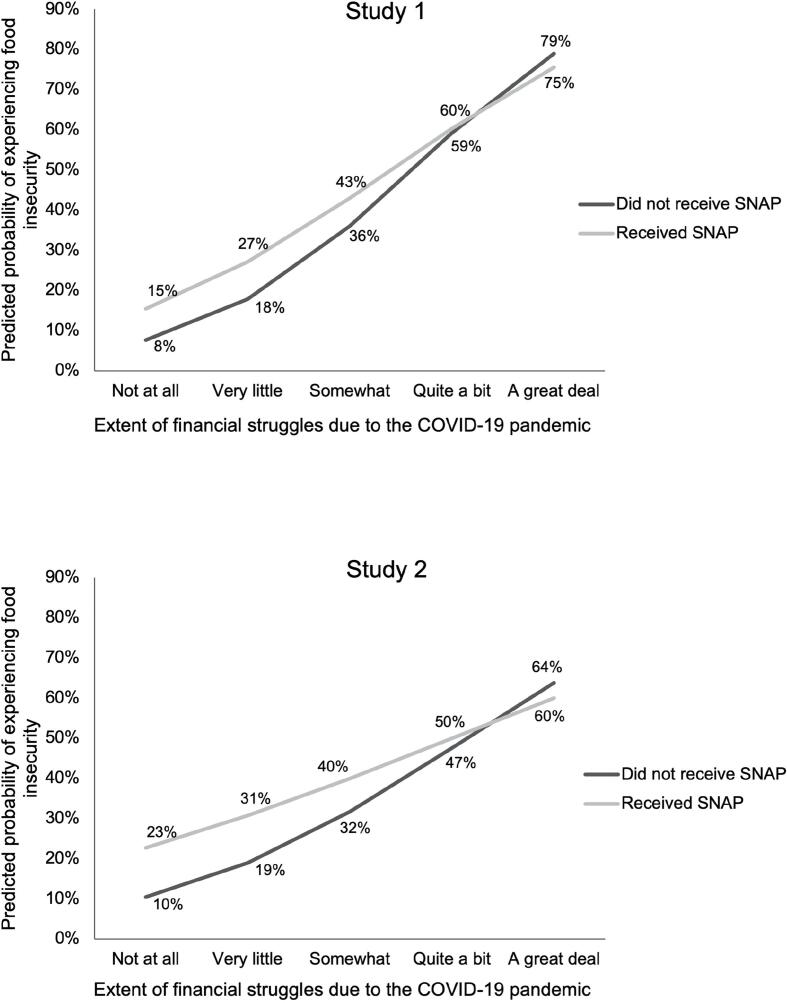

In Study 1, receipt of aid from SNAP moderated the association between financial struggles due to COVID-19 and pandemic food insecurity, after controlling for all other predictors in the model (interaction p = 0.03, Fig. 2). In Study 1, the association of financial struggles with greater pandemic food insecurity was stronger for non-SNAP recipients than SNAP recipients. In Study 2, the pattern was similar (Fig. 2), although the interaction term was not statistically significant (interaction p = 0.05). Financial struggles were associated with greater likelihood of food insecurity for SNAP and non-SNAP recipients in both studies (all p < 0.001). Receipt of WIC did not moderate the association between financial struggles due to COVID-19 and food insecurity in either study (Study 1: interaction p = 0.38; Study 2: interaction p = 0.67).

Fig. 2.

Moderation of association between financial struggles due COVID-19 and food insecurity by SNAP receipt.

4. Discussion

In two national convenience samples recruited in late spring and summer 2020, roughly one in three participants experienced pandemic food insecurity. This finding is consistent with previous research on food access and food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic among college students (Owens et al., 2020) and parents (Bauer, 2020, Bitler et al., 2020, Kent et al., 2020, Schanzenbach and Pitts, 2020). The majority of participants reported experiencing barriers to obtaining food because of the COVID-19 pandemic. More than one in three participants reported using the charitable food system in the past 2 months. Financial struggles due to the COVID-19 pandemic was an important predictor of experiencing food insecurity. However, receipt of aid from SNAP helped buffer against the harmful relationship between financial struggles and food insecurity, particularly among those with the highest financial struggles.

In both studies, we found that not having enough money was the single largest barrier to obtaining food, with roughly half of the participants reporting this reason. This aligns with prior findings that barriers to getting food typically include not having enough money, prioritizing other bills, and the price of food at the store (Breyer and Voss-Andreae, 2013, Coleman-Jensen, 2020, DeMartini et al., 2013). The pandemic has also presented new challenges to obtaining food. In both studies, several of the commonly reported barriers to getting food were related to the COVID-19 pandemic specifically. These included worrying about both getting and exposing others to COVID-19 at the store, not enough food at the store, and difficulties traveling to the store. These findings mirror recent survey results that, during the COVID-19 pandemic, food insecure households desire interventions that address both the physical and economic challenges to accessing food including improving trust in the safety of going to stores, access to public transportation, and financial support or increased government benefits (Niles et al., 2020). Thus, retailers should continue to implement and improve their COVID-19-related policies and better communicate them to the public to increase consumer trust that in-person shopping poses low COVID transmission risk. At the state- and national-level, a SNAP Online Purchasing Pilot, which allows retailers to accept SNAP payment for online purchases (i.e., by waiving the typical pay in-person SNAP requirement), is currently underway in 45 states and the District of Columbia (U.S. Department of Agriculture - Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS), 2020b). Though this program is still in a pilot phase, it has the potential to directly address the specific COVID-19-related barriers to obtaining food identified in both studies.

We found that higher education predicted higher risk of food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic in both studies. One explanation for this unexpected finding could be that the participants with higher education in our samples may have experienced new financial hardship and stressors regarding availability and access to food for the first time. They may therefore have not yet developed strategies to cope with or navigate the new stressors. Many people experienced food insecurity for the first time during the COVID-19 pandemic. One study found that 36% of Vermont, U.S. residents with food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic had not experienced food insecurity in the year before the pandemic (Niles et al., 2020). In that study, newly food insecure households were less likely to accept food or borrow money from friends and family, use a food pantry, or use government benefits; and more participants with a post-graduate degree were newly food insecure compared to consistently food insecure. However, in contrast with the current findings, a college education was protective against food insecurity (Niles et al., 2020). Future studies should further evaluate the relationship between educational attainment, food insecurity due to the COVID-19 pandemic, and use of buffering strategies like social and government assistance.

Hispanic and Latino/a participants experienced higher levels of food insecurity in Study 1. This finding supports prior findings on food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic (Karpman et al., 2020a). In contrast, race was not associated with food insecurity in either study, conflicting previous findings that people of color tend to be at a greater risk of food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic (Karpman et al., 2020a, Karpman et al., 2020b, Owens et al., 2020, Schanzenbach and Pitts, 2020, Waxman et al., 2020, Wolfson and Leung, 2020) and after controlling for socioeconomic status (Myers and Painter, 2017, Soldavini et al., 2021). This surprising finding may be due to the overshadowing effect of financial struggles as a large predictor of food insecurity. Another possible explanation for the lack of associations between race and food insecurity in our studies is that we assessed food insecurity specifically due to the COVID-19 pandemic, whereas other measures of food insecurity typically query lack of food due to financial constraints (e.g., not having enough money for food). Early in the pandemic, many households, regardless of race, may have been worried about not having enough or the right kinds of food due to temporary stocking issues, inability to get grocery delivery, or aversion to shopping in-store.

Receipt of aid from SNAP appeared to buffer the association of financial struggles with food insecurity in both studies, especially at high levels of financial struggles. This pattern of findings suggests that the receipt of aid from SNAP may have a protective effect against food insecurity. Because of the potential buffering effect of SNAP receipt on food insecurity, policy efforts should focus on minimizing the barriers to receiving and using aid from SNAP (e.g., waiving face-to-face interviews, allowing SNAP use in online grocery stores). We measured perceived, rather than actual, financial struggles. Perception of financial strain is associated with poor mental health (Richardson et al., 2017) and research shows that perceived financial stress is a better predictor of mental health outcomes than actual financial strain (Selenko and Batinic, 2011). This evidence, along with our findings that self-reported financial struggles are associated with food insecurity, identifies a population, individuals with self-reported financial struggles, to target for food insecurity interventions.

Given that financial struggles was a driver of food insecurity in both of our studies, and that aid from SNAP may protect against the harmful effects of financial struggles, policy solutions for food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic should aim to improve both financial and nutrition assistance programs. The American Rescue Plan Act of 2021 continues the increase in SNAP benefits originally passed in 2020, allows states to extend Pandemic – Electronic Benefit transfer (P-EBT) which allows children to receive nutrition benefits equivalent to the school lunch program (U.S. Department of Agriculture - Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS), 2020a), and allocates funds toward improving outreach and innovation within the WIC program (Yarmuth, 2021). Other policy options that could potentially alleviate food insecurity include expanding programs like the public–private partnership between USDA and Meals-to-You to provide meals to children who would have received food from the National School Lunch Program (Hetrick et al., 2020, U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2020). Another option in future times of crisis and elevated levels of food insecurity could be to reinstate the USDA’s Farmers to Family Food Box Program, which reallocates food destined for restaurants and food service companies to families (U.S. Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA-AMS), 2020).

4.1. Strengths and limitations

Strengths of these studies are the timeliness of the research topic, given the high rates of food insecurity since the COVID-19 pandemic began, and the diversity of participants within the samples. Limitations of the studies include the use of convenience samples, which means the generalizability of results remains to be established, especially for the food insecurity prevalence estimates. However, while convenience samples can yield biased prevalence estimates, they often yield generalizable associations in observational data (Jeong et al., 2018).

Because of the novelty of events surrounding the COVID-19 pandemic, we adapted a validated scale to measure pandemic food insecurity, and this adaptation limits the comparability of the prevalence of food insecurity to pre-COVID-19 estimates and other estimates during this time. Along with this adaptation, we also developed multiple novel measures to assess reactions to the COVID-19 pandemic and therefore the construct validity of these measures is unknown. We did not assess SNAP or WIC eligibility, precluding us from assessing moderation only among those eligible for benefits. We also did not define which programs may be classified as SNAP (e.g., P-EBT) when asking about SNAP receipt in the survey which may have resulted in under-reporting. Lastly, the cross-sectional design limited our ability to fully rule out potential confounding variables and infer causal associations. Given the necessity of research on the topic of food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic, future research should build upon this study in order to address its limitations; for example, by exploring similar research questions in nationally representative samples over time and examining the impact of policy actions on food insecurity.

4.2. Conclusions

Food insecurity increased sharply during the COVID-19 pandemic. In our sample, participants reported many barriers to obtaining food, including not having sufficient money to buy groceries and several COVID-19-specific barriers, such as worrying about getting COVID-19 at the store. Financial struggles due to COVID-19 was an important predictor of experiencing pandemic food insecurity and receipt of aid from SNAP buffered against the harmful effects of financial struggles on food security. Results suggest that food insecurity could be mitigated through policy improving financial and nutrition assistance programs. These findings help inform policy and other interventions to increase food security during the COVID-19 pandemic and may also be useful in future crises like natural disasters or financial recessions.

Funding

The survey data used in this study were supported by a grant from Healthy Eating Research, a national program of the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation (Study 1) and The University of North Carolina’s University Cancer Research Fund (Study 2). K01HL147713 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the NIH supported MGH’s time working on the paper. This research also received support from the Population Research Infrastructure Program awarded to the Carolina Population Center (P2C HD050924) at The University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the NIH or the Robert Wood Johnson Foundation. No other financial disclosures were reported by the authors of this paper.

CRediT authorship contribution statement

Alexandria E. Reimold: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Visualization, Writing – original draft. Anna H. Grummon: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Lindsey S. Taillie: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Noel T. Brewer: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Eric B. Rimm: Investigation, Methodology, Writing – review & editing. Marissa G. Hall: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Investigation, Methodology, Supervision, Writing – review & editing.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Acknowledgements

We thank Catherine Zimmer of the University of North Carolina Odum Institute for Research in Social Science and Maxime Bercholz of the Carolina Population Center for statistical consultation.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pmedr.2021.101500.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

The following are the Supplementary data to this article:

References

- Barrett, C.B., 2002. Food security and food assistance programs. pp. 2103–2190.

- Bauer, L., 2020. The COVID-19 crisis has already left too many children hungry in America. Brookings. https://www.brookings.edu/blog/up-front/2020/05/06/the-covid-19-crisis-has-already-left-too-many-children-hungry-in-america/ (accessed 11.6.20).

- Ahn S., Norwood F.B. Measuring food insecurity during the COVID-19 pandemic of spring 2020. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy. 2021;43(1):162–168. doi: 10.1002/aepp.v43.110.1002/aepp.13069. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bickel G., Nord M., Price C., Hamilton W., Cook J. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; Alexandria VA: 2000. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Bitler, M., Hoynes, H., Schanzenbach, D.W., 2020. The Social Safety Net in the Wake of COVID-19 (No. w27796). National Bureau of Economic Research, Cambridge, MA. https://doi.org/10.3386/w27796.

- Bleich S., Dunn C., Fleishhacker S. Healthy Eating Research; Durham, NC: 2020. The Impact of Increasing SNAP Benefits on Stabilizing the Economy, Reducing Poverty and Food Insecurity amid COVID-19 Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Breyer B., Voss-Andreae A. Food mirages: Geographic and economic barriers to healthful food access in Portland, Oregon. Health Place. 2013;24:131–139. doi: 10.1016/j.healthplace.2013.07.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Coleman-Jensen A. U.S food insecurity and population trends with a focus on adults with disabilities. Physiol. Behav. 2020;220:112865. doi: 10.1016/j.physbeh.2020.112865. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeMartini T.L., Beck A.F., Kahn R.S., Klein M.D. Food insecure families: description of access and barriers to food from one pediatric primary care center. J. Community Health. 2013;38(6):1182–1187. doi: 10.1007/s10900-013-9731-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DePolt R.A., Moffitt R.A., Ribar D.C. Food stamps, temporary assistance for needy families and food hardships in three American cities. Pac. Econ. Rev. 2009;14:445–473. doi: 10.1111/j.1468-0106.2009.00462.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Farmer, B.M., 2020. March 2020: Dr. Anthony Fauci talks with Dr Jon LaPook about COVID-19. CBS News. https://www.cbsnews.com/news/preventing-coronavirus-facemask-60-minutes-2020-03-08/ (accessed 3.17.21).

- Feeding America, 2020. The Impact of the Coronavirus on Food Insecurity. https://www.feedingamerica.org/sites/default/files/2020-04/Brief_Impact%20of%20Covid%20on%20Food%20Insecurity%204.22%20%28002%29.pdf.

- Gregory, C.A., 2017. Food Insecurity, Chronic Disease, and Health Among Working-Age Adults (No. ERR-235). U.S. Department of Agriculture, Economic Research Service.

- Grummon, A.H., Hall, M.G., Mitchell, C.G., Pulido, M., Sheldon, J.M., Noar, S.M., Ribisl, K.M., Brewer, N.T., 2020. Reactions to messages about smoking, vaping and COVID-19: two national experiments. Tob. Control. https://doi.org/10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055956. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- Gundersen C., Ziliak J.P. Food insecurity and health outcomes. Health Aff. (Millwood) 2015;34(11):1830–1839. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2015.0645. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gundersen C., Ziliak J.P. Food insecurity research in the United States: where we have been and where we need to go. Appl. Econ. Perspect. Policy. 2018;40(1):119–135. doi: 10.1093/aepp/ppx058. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hetrick, R.L., Rodrigo, O.D., Bocchini, C.E., 2020. Addressing Pandemic-Intensified Food Insecurity. Pediatrics 146. https://doi.org/10.1542/peds.2020-006924. [DOI] [PubMed]

- Jeong M., Zhang D., Morgan J.C., Ross J.C., Osman A., Boynton M.H., Mendel J.R., Brewer N.T. Similarities and differences in tobacco control research findings from convenience and probability samples. Ann. Behav. Med. Publ. Soc. Behav. Med. 2018;53:476–485. doi: 10.1093/abm/kay059. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Karpman M., Gonzalez D., Kenney G.M. Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2020. Parents Are Struggling to Provide for Their Families during the Pandemic. [Google Scholar]

- Karpman M., Zuckerman S., Gonzalez D., Kenney G.M. Urban Institute; Washington, DC: 2020. The COVID-19 Pandemic Is Straining Families’ Abilities to Afford Basic Needs: Low-Income and Hispanic Families the Hardest Hit. [Google Scholar]

- Keith-Jennings B., Llobrera J., Dean S. Links of the supplemental nutrition assistance program with food insecurity, poverty, and health: evidence and potential. Am. J. Public Health. 2019;109(12):1636–1640. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2019.305325. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kent K., Murray S., Penrose B., Auckland S., Visentin D., Godrich S., Lester E. Prevalence and socio-demographic predictors of food insecurity in Australia during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 2020;12:2682. doi: 10.3390/nu12092682. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myers A.M., Painter M.A. Food insecurity in the United States of America: an examination of race/ethnicity and nativity. Food Secur. 2017;9(6):1419–1432. doi: 10.1007/s12571-017-0733-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Niles M.T., Bertmann F., Belarmino E.H., Wentworth T., Biehl E., Neff R. The early food insecurity impacts of COVID-19. Nutrients. 2020;12:2096. doi: 10.3390/nu12072096. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- NORC at the University of Chicago, 2020. COVID Impact Survey: Week 1, National Findings. NORC at the University of Chicago.

- Owens M.R., Brito-Silva F., Kirkland T., Moore C.E., Davis K.E., Patterson M.A., Miketinas D.C., Tucker W.J. Prevalence and social determinants of food insecurity among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Nutrients. 2020;12:2515. doi: 10.3390/nu12092515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Richardson T., Elliott P., Roberts R., Jansen M. A longitudinal study of financial difficulties and mental health in a national sample of British undergraduate students. Community Ment. Health J. 2017;53(3):344–352. doi: 10.1007/s10597-016-0052-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schanzenbach, D.W., Pitts, A., 2020. How Much Has Food Insecurity Risen? Evidence from the Census Household Pulse Survey. Northwestern Institute for Policy Research.

- Schlanger, Z., 2020. Coronavirus Is Causing a Huge PPE Shortage in the U.S. Time. https://time.com/5823983/coronavirus-ppe-shortage/ (accessed 3.17.21).

- Scudellari M. How the pandemic might play out in 2021 and beyond. Nature. 2020;584(7819):22–25. doi: 10.1038/d41586-020-02278-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selenko E., Batinic B. Beyond debt. A moderator analysis of the relationship between perceived financial strain and mental health. Soc. Sci. Med. 2011;73(12):1725–1732. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.09.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Soldavini J., Andrew H., Berner M. Characteristics associated with changes in food security status among college students during the COVID-19 pandemic. Transl. Behav. Med. 2021;11:295–304. doi: 10.1093/tbm/ibaa110. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- U.S. Census Bureau, 2010. 2010 census regions and divisions of the United States. https://www.census.gov/geographies/reference-maps/2010/geo/2010-census-regions-and-divisions-of-the-united-states.html (accessed 3.8.21).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture – Agricultural Marketing Service (USDA-AMS), 2020. USDA Farmers to Families Food Box. https://www.ams.usda.gov/selling-food-to-usda/farmers-to-families-food-box (accessed 7.5.21).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture – Economic Research Service (USDA-ERS), 2020. Definitions of Food Security. https://www.ers.usda.gov/topics/food-nutrition-assistance/food-security-in-the-us/definitions-of-food-security.aspx (accessed 10.7.20).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture - Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS), 2020. State Guidance on Coronavirus Pandemic EBT (P-EBT). https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/state-guidance-coronavirus-pandemic-ebt-pebt (accessed 11.30.20).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture - Food and Nutrition Service (USDA-FNS), 2020. FNS Launches the Online Purchasing Pilot. https://www.fns.usda.gov/snap/online-purchasing-pilot (accessed 10.7.20).

- U.S. Department of Agriculture (USDA), 2020. Meals to You Partnership Delivers Nearly 30 Million Meals. https://www.usda.gov/media/press-releases/2020/07/16/usda-meals-you-partnership-delivers-nearly-30-million-meals (accessed 3.16.21).

- Vercammen K.A., Moran A.J., McClain A.C., Thorndike A.N., Fulay A.P., Rimm E.B. Food security and 10-year cardiovascular disease risk among U.S. adults. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2019;56(5):689–697. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2018.11.016. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waxman, E., Gupta, P., Karpman, M., 2020. More Than One in Six Adults Were Food Insecure Two Months into the COVID-19 Recession. Urban Inst. https://www.urban.org/research/publication/more-one-six-adults-were-food-insecure-two-months-covid-19-recession (accessed 9.17.20).

- Williams R. Using the margins command to estimate and interpret adjusted predictions and marginal effects. Stata J. Promot. Commun. Stat. Stata. 2012;12(2):308–331. doi: 10.1177/1536867X1201200209. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfson J.A., Leung C.W. Food insecurity and COVID-19: disparities in early effects for US adults. Nutrients. 2020;12:1648. doi: 10.3390/nu12061648. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarmuth, J.A., 2021. Text - H.R.1319 - 117th Congress (2021-2022): American Rescue Plan Act of 2021. Congress.gov. https://www.congress.gov/bill/117th-congress/house-bill/1319/text (accessed 3.17.21).

- Ziady, H., 2020. Can’t find what you want in the grocery store? Here’s why. CNN Bus. https://www.cnn.com/2020/04/01/business/food-supply-chains-coronavirus/index.html (accessed 3.17.21).

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.