Abstract

BACKGROUND AND AIMS:

In February 2020, the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network replaced donor service area-based allocation of livers with acuity circles, a system based on three homogeneous circles around each donor hospital. This system has been criticized for neglecting to consider varying population density and proximity to coast and national borders.

APPROACH AND RESULTS:

Using Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients data from July 2013 to June 2017, we designed heterogeneous circles to reduce both circle size and variation in liver supply/demand ratios across transplant centers. We weighted liver demand by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)/Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) because higher MELD/PELD candidates are more likely to be transplanted. Transplant centers in the West had the largest circles; transplant centers in the Midwest and South had the smallest circles. Supply/demand ratios ranged from 0.471 to 0.655 livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate. Our heterogeneous circles had lower variation in supply/demand ratios than homogeneous circles of any radius between 150 and 1,000 nautical miles (nm). Homogeneous circles of 500 nm, the largest circle used in the acuity circles allocation system, had a variance in supply/demand ratios 16 times higher than our heterogeneous circles (0.0156 vs. 0.0009) and a range of supply/demand ratios 2.3 times higher than our heterogeneous circles (0.421 vs. 0.184). Our heterogeneous circles had a median (interquartile range) radius of only 326 (275–470) nm but reduced disparities in supply/demand ratios significantly by accounting for population density, national borders, and geographic variation of supply and demand.

CONCLUSIONS:

Large homogeneous circles create logistical burdens on transplant centers that do not need them, whereas small homogeneous circles increase geographic disparity. Using carefully designed heterogeneous circles can reduce geographic disparity in liver supply/demand ratios compared with homogeneous circles of radius ranging from 150 to 1,000 nm.

Responding to a July 2018 directive from the Department of Health and Human Services,(1) the Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network (OPTN)/United Network for Organ Sharing (UNOS) Board of Directors replaced the donor service area (DSA)-based allocation system with the acuity circles allocation system, a system employing 150, 250, and 500 nautical mile (nm) circles around each donor hospital. Acuity circles are a homogeneous circular allocation system, meaning that the circles are the same size everywhere in the United States regardless of geographic variation in liver supply, liver demand, population density, and proximity to the coast and national borders. The acuity circles allocation system was implemented in February 2020.

A cursory view of liver supply and demand (Fig. 1) suggests that large, homogeneous circles might not be necessary or optimal for allocation. Large circles might be required in areas of the country that are sparsely populated, near the coast, or near national borders. Large circles, however, might induce undue transport, organ quality, and health care cost burdens in relatively high supply areas of the country where smaller circles may be sufficient to meet demand. Using homogeneous large, arbitrary geographic boundaries might even worsen geographic disparity, as using regions for distribution has been shown to do.(2) We recently demonstrated that homogeneous circles do not reduce variance in supply-to-demand ratios when compared with DSAs unless the circles are at least 400 nm in radius.(3) We have also demonstrated that one type of heterogeneous circles, with circles varying in size but containing a fixed population, do not reduce variance in supply-to-demand ratios when compared with DSAs unless the circles contain at least 50 million people.(3) In that work and the present work, we considered a metric of liver availability that others have suggested: the ratio of liver supply to demand.(4) In the present work, we weighted demand by Model for End-Stage Liver Disease (MELD)/Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease (PELD) so that candidates with higher MELD/PELD count more toward the demand metric. This reflects the fact that candidates at a higher MELD/PELD are more likely to be transplanted than those with a lower MELD/PELD.

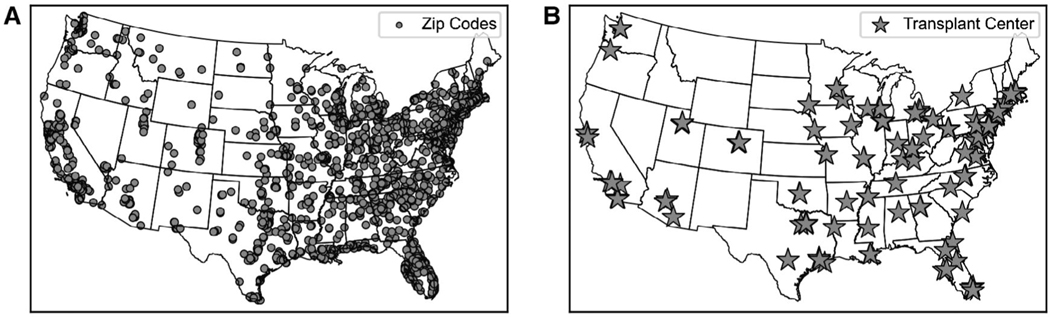

FIG. 1.

Geographic variation in liver supply and demand. The circles (A) indicate the location of the supply of livers at each ZIP code where at least one deceased donor liver was recovered and transplanted between 07/2013 and 06/2017 (livers recovered and transplanted in AK, HI, and PR are not shown), while the stars (B) indicate the liver transplant centers in the continental United States.

We designed heterogeneous circles for liver allocation, using a genetic algorithm to seek solutions with smaller circles to reduce transport distances while ensuring that MELD-weighted supply/demand ratios were similar across transplant centers. We tested whether our heterogeneous circles could reduce geographic disparity in MELD-weighted supply/demand ratios across transplant centers in the continental United States.

Materials and Methods

DATA SOURCE

This study used data from the Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients (SRTR) external release made available in March 2018. This research does not constitute human subjects research, as it involves secondary analysis of de-identified data. It was reviewed and declared exempt by the Johns Hopkins Medicine IRB. The SRTR data system includes data on all donors, waitlisted candidates, and transplant recipients in the United States submitted by members of the OPTN and has been described elsewhere. The Health Resources and Services Administration, United States Department of Health and Human Services provides oversight to the activities of the OPTN and SRTR contractors.

STUDY POPULATION

We studied 25,893 transplanted deceased donor livers and 49,646 waitlist candidates whose first active date on the waitlist was between July 2013 and June 2017 (i.e., incident candidates) from 139 liver transplant centers. We excluded waitlist candidates from Hawaii and Puerto Rico as well as candidates whose first active date was prior to the study period (i.e., prevalent candidates). These data were split into two sets, a training set (July 2013-June 2015) that was used to design the heterogeneous circles and a test set (July 2015-June 2017) that was used to test the heterogeneous circles and compare them with various homogeneous circles.

ESTIMATING SUPPLY/DEMAND RATIOS USING CIRCLES

We defined demand at each transplant center as the number of incident candidates listed at that center, weighted by the MELD/PELD of those incident candidates when they were first active on the waitlist. We weight demand according to MELD/PELD to reflect the fact that candidates at a higher MELD/PELD are more likely to be transplanted than those with a lower MELD/PELD. Let N be the total number of incident candidates, and let Ni be the number of incident candidates whose first active MELD/PELD was i. Then the weight, wi, given to these candidates was defined as the proportion of incident candidates at or below MELD/PELD i.

Let ni be the number of incident candidates at transplant center T whose first active MELD/PELD was i. Then the MELD-weighted demand, DT, at this center is defined as1

We scaled all of the demand quantities by a constant to ensure that the total national demand, given as the number of MELD-weighted incident candidates, was equivalent to the total number of incident candidates. Transplant centers were used as the geographic locations of liver demand.

ZIP codes were used as the geographic units of liver supply. The supply of livers within each ZIP code was the number of deceased donor livers recovered in a hospital within that ZIP code that were ultimately transplanted.

For heterogeneous circles, our algorithm automatically selected the best radius for each transplant center’s circle; for homogeneous circles, each transplant center was given the same circle of a specified size. Each transplant center’s circle contained all the ZIP codes where the geodesic distance between the transplant center and the centroid of the ZIP code was less than or equal to the radius of that transplant center’s circle. The geodesic distance between each transplant center and ZIP code was calculated in Python 3.7.3 using GeoPy 1.19.0. ZIP code latitude and longitude coordinates were obtained from the United States Census Bureau 2015 Gazetteer Files.

The supply of livers available to each transplant center was defined as the number of livers available within that transplant center’s circle, accounting for MELD-weighted incident candidates at other centers whose circles overlapped. For each ZIP code contained in multiple transplant centers’ circles, the supply of livers from that ZIP code to each transplant center was proportionate to that transplant center’s demand. For example, suppose 100 livers were recovered in a ZIP code contained in the circles for transplant centers A and B and that A and B have demand of 150 and 50 MELD-weighted incident candidates, respectively. Because transplant center A accounts for 75% of the demand and transplant center B accounts for 25% of the demand, transplant center A would see a supply of 75 livers and transplant center B would see a supply of 25 livers from this ZIP code. If a ZIP code was not contained in the circle of any transplant center, then the livers from that ZIP code were divided nationwide, proportionate to the demand of each transplant center. The ratio of liver supply to demand for a transplant center was defined as the number of livers available to that transplant center divided by the number of MELD-weighted incident candidates at that transplant center. This is the reciprocal of the disparity metric used by Rana et al.(4)

ESTIMATING THE DISTANCE LIVERS TRAVEL

We estimated the average distance a liver would travel using these circles. For example, suppose a ZIP code is 20 nm from transplant center A and 100 nm from transplant center B. If 75 livers went to transplant center A, each of those livers would travel 20 nm, and if 25 livers went to transplant center B, each of those livers would travel 100 nm. On average, livers from that ZIP code would travel 40 nm. Using a heat map, we illustrated the average distance a liver would travel if it were recovered anywhere in the continental United States using our heterogeneous circles and compared it with homogeneous circles of radius 500 nm, the largest circle used in the acuity circles allocation system.

DESIGNING CIRCLES WITH GENETIC ALGORITHM

We used a genetic algorithm to design the radius of the circle around each transplant center using data from our training set (July 2013-June 2015). Genetic algorithms are a heuristic tool for optimization, which we applied here to design circles that make supply/demand ratios more similar across transplant centers while favoring smaller circles.(5) We began the algorithm by assigning each of the 139 transplant centers a circle of radius 250 nm. We then created 200 offspring of this parent solution, each one a copy of the parent with the exception of a mutation that added a random number (drawn from the normal distribution of mean 0 and standard deviation 75) to the radius of a randomly chosen transplant center’s circle. For each offspring, we calculated a fitness score, which was the inverse of the product of the variance in supply/demand ratios, the range of supply/demand ratios, and the average distance livers would travel. The offspring with the highest fitness score (if greater than the parent) became the parent of the next generation, and the process was iterated until 100 consecutive generations occurred with no increase in the fitness score. At this point, the solution was examined and manually perturbed by increasing the radius for the transplant centers with the lowest supply-to-demand ratios. The algorithm was again allowed to continue until 100 consecutive generations occurred with no increase in fitness score, at which point the solution was obtained.

COMPARING WITH SUPPLY/DEMAND RATIOS USING HOMOGENEOUS CIRCLES

To determine whether our heterogeneous circles were effective in reducing geographic disparity, we tested our heterogeneous circles and compared their performance with that of various homogeneous circle sizes using our test set (July 2015-June 2017). We calculated the variance and range of supply/demand ratios across all transplant centers using our heterogeneous circles and compared these with the variance and range of supply/demand ratios calculated for homogeneous circles for sizes between 150 and 1,000 nm.

Results

HETEROGENEOUS CIRCLE SIZES

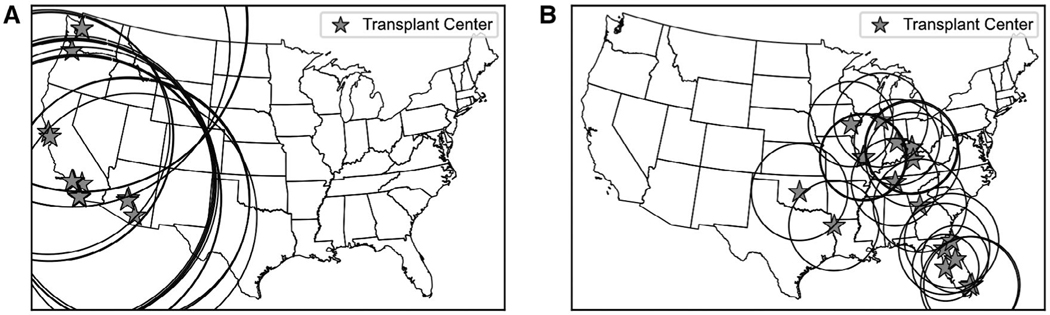

The median (interquartile range) radius of our heterogeneous circles was 326 (275–470) nm (Fig. 2). The 20 transplant centers with the largest circles were in the western states of Washington, Oregon, California, and Arizona and had circles ranging in size from 662 to 894 nm (Fig. 3A), whereas the 20 transplant centers with the smallest circles were in the Midwest and the South and had circles ranging in size from 179 to 264 nm (Fig. 3B). All ZIP codes in which a liver was recovered were contained within at least one transplant center’s circle, with the exception of 15 located in Hawaii and Alaska.

FIG. 2.

Distribution of heterogeneous circle radii around each transplant center.

FIG. 3.

Transplant center and circle size. (A) The 20 transplant centers with the largest circles were AZMC (662 nm), CASF (665 nm), AZUA (666 nm), AZCH (666 nm), AZGS (666 nm), CASU (675 nm), CAPC (678 nm), CALL (745 nm), CACL (766 nm), CASD (773 nm), CACH (774 nm), CAGH (777 nm), CAUH (777 nm), CACS (778 nm), CAUC (791 nm), ORUO (855 nm), ORVA (855 nm), WASM (889 nm), WAUW (890 nm), and WACH (894 nm). (B) The 20 transplant centers with the smallest circles were FLTG (179 nm), FLFH (180 nm), IAIV (232 nm), MOBH (233 nm), INIM (233 nm), MOSL (236 nm), MOCH (237 nm), TNVU (238 nm), MOCG (239 nm), LAWK (245 nm), FLUF (245 nm), OHUC (250 nm), GAEH (253 nm), FLSL (255 nm), ILLU (256 nm), FLBC (256 nm), OHCM (256 nm), KYUK (256 nm), FLCC (261 nm), and OKBC (264 nm).

SUPPLY/DEMAND RATIOS USING HETEROGENEOUS CIRCLES

Using circles designed with data from July 2013 to June 2015 and testing with the data from July 2015 to June 2017, the median (variance) supply/demand ratio was 0.536 (0.0009) livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate and ranged from 0.471 livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate in Nebraska to 0.655 livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate in Florida.

ESTIMATING THE DISTANCE LIVERS TRAVEL

Using a heat map, we illustrated the average distance a liver would travel if it were recovered anywhere in the continental United States using our heterogeneous circles and using homogeneous circles with radius 500 nm, the largest circle used in the acuity circles allocation system. Using the homogeneous 500 nm circles, livers are expected to travel approximately the same distance (350–450 nm) throughout the continental United States (Fig. 4A). Using our heterogeneous circles, livers are expected to require greater travel when recovered in the West (400–700 nm) but less travel when recovered in the East, where much of that region would require less than 200 nm of travel (Fig. 4B). We also looked at the required travel distance for livers recovered near the high-demand area of Philadelphia and New York City. Using the homogeneous 500 nm circles, livers are expected to travel 200–300 nm on average (Fig. 5A), whereas using our heterogeneous circles, livers are expected to travel only 100–200 nm on average (Fig. 5B).

FIG. 4.

Average distance livers would travel. (A) Using homogeneous 500 nm circles, each location indicates the average distance a liver would travel based on its recovery location and on the homogeneous circles. Livers will require roughly the same travel distance throughout the continental United States. (B) Using heterogeneous circles, each location indicates the average distance a liver would travel based on its recovery location and on the heterogeneous circles. Compared to homogeneous 500 nm circles, livers require more travel in the West and the less travel in the East.

FIG. 5.

Average distance livers would travel in the northeast. (A) Using homogeneous 500 nm circles, each location indicates the average distance a liver would travel based on its recovery location and on the homogeneous circles. Livers recovered near high-demand areas such as Philadelphia and New York City will travel approximately 200–250 nm on average. (B) Using heterogeneous circles, each location indicates the average distance a liver would travel based on its recovery location and on the heterogeneous circles. Livers recovered near high-demand areas such as Philadelphia and New York City will only travel approximately 100–150 nm on average.

COMPARING SUPPLY/DEMAND RATIOS USING HOMOGENEOUS CIRCLES

To determine whether our heterogeneous circles were effective in reducing geographic disparity, we calculated the variance and range of supply/demand ratios across all transplant centers for various sizes of homogeneous circles and compared them with our heterogeneous circles. Our heterogeneous circles always had a lower variance in supply/demand ratios (Fig. 6A) and a lower range of supply/demand ratios (Fig. 6B) than homogeneous circles of any size between 150 and 1,000 nm, despite our heterogeneous circles having a median circle size of only 326 nm. Homogeneous circles of radius 500 nm, the largest circle used in the acuity circles allocation system, had a variance in supply/demand ratios 16 times higher than our heterogeneous circles (0.0156 vs. 0.0009) and a range of supply/demand ratios 2.3 times higher than our heterogeneous circles (0.421 vs. 0.184), from 0.348 livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate in Massachusetts to 0.768 livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate in North Carolina (Fig. 7).

FIG. 6.

The variance and range of supply/demand ratios across transplant centers using homogeneous and heterogeneous circles (A) The dots indicate the variance in the supply/demand ratios across transplant centers using homogeneous circles of the size indicated on the x-axis. The star indicates the variance in supply/demand ratios for the designed circles, located at the median radius size. (B) The dots indicate the range of supply/demand ratios across transplant centers using homogeneous circles of the size indicated by the x-axis. The star indicates the range of supply/demand ratios for the designed heterogeneous circles, located at the median radius size.

FIG. 7.

Distribution of supply/demand ratios for heterogeneous circles (gray) and homogeneous circles of radius 500 nm (X).

Discussion

Using national registry data of transplant center liver supply and demand, we designed heterogeneous circles to reduce circle size and transport distance where possible while making MELD-weighted supply/demand ratios similar across transplant centers. There was an overall national supply/demand ratio of 0.539 livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate from July 2015 to June 2017. Our heterogeneous circles had a variance of supply/demand ratios of 0.0009 and a range of supply/demand ratios of 0.471–0.655 livers per MELD-weighted incident candidate, which are much lower supply/demand ratio differences than homogeneous circles of any radius between 150 and 1,000 nm. In particular, homogeneous circles of radius 500 nm, the largest circle used in the acuity circles allocation system, had a variance in supply/demand ratios 16 times higher than our heterogeneous circles (0.0156 vs. 0.0009) and a range 2.3 times higher than our heterogeneous circles (0.421 vs. 0.184).When compared with homogeneous 500 nm circles, our heterogeneous circles required greater travel in the West and lesser travel in the East.

Our study shows that to reduce geographic disparity, transplant centers in the West need circle sizes upward of 900 nm, whereas transplant centers in the Midwest and the South may only need circle sizes around 200 nm. Heterogeneous circles around transplant centers would make supply/demand ratios nearly identical to the national average, using circles with a median size of only 326 nm.

Optimization is a method for designing geographic boundaries to ensure equity across geographic areas. Prior work on optimizing geographic boundaries for liver allocation used DSA boundaries to design redistricting and neighborhood proposals rather than circles. We used an integer program to partition the current 58 DSAs into new sharing districts to minimize the number of livers directed away from the most medically urgent candidates and tested the redistricting plan in a patient-level simulation that included clinical details, such as MELD and transplant center accept or decline decisions.(6) Another optimization proposal was that of Kilambi and Mehrotra, who optimized overlapping neighborhoods to guarantee that organs would always be shared to neighboring DSAs.(7) Proposals based on fixed boundaries have fallen out of favor recently, as policymakers have pursued circular and continuous scoring solutions.

The OPTN’s acuity circle system employs homogeneous circles around transplant centers, but no optimization models were applied to determine the best acuity circle sizes. In a previous study, we designed heterogeneous circles without optimization that varied circle size according to population density. We drew heterogeneous circles with a fixed population of 12 million (radius ranging from 97 to 218 nm) and 50 million (radius ranging from 305 to 590 nm) and compared them with homogeneous circles of radius 150 and 400 nm.(3) We found that homogeneous circles of radius 150 nm and heterogeneous circles of population 12 million did not reduce the variance in supply/demand ratios when compared with DSAs, but homogeneous circles of radius 400 nm and heterogeneous circles of population 50 million did reduce variance and mitigate geographic disparity. In the present study, we considered liver supply and demand, rather than just population, because population might not be well correlated with liver supply and demand. Factors other than population density, such as demographics,(8) disease burden, health care quality and access, and organ procurement organization performance, greatly influence the size and composition of waitlists and the supply of donated organs.

Some organ procurement organizations have established or proposed centralized organ recovery centers. At present, OPTN policies allocate organs based on the distance to the donor hospital, not the recovery center, so we have used donor hospital zip codes for our study. Ultimately, the transplant community must decide whether to measure distance from a centralized organ recovery center or from the donor hospitals, and our methodology can be adapted to either.

Mathematically optimized circles can be smaller in high population density areas where there is sufficient nearby supply to meet their demand. Large circles can produce long transport and cold ischemia times and high transport costs, creating a potentially undue burden on transplant centers, not all of which need to obtain distant livers. Using our heterogeneous circles, only organs that must travel far to meet a medical need would travel. Although broader sharing is not expected to significantly increase cold ischemia time for livers, it does increase the number of organs flying rather than driving, which has implications for efficiency and health care costs.(9) Minimizing circle size where possible, as we did, will increase allocation efficiency.

We made some assumptions that merit discussion. We neglected the trajectory of candidate’s MELD/PELD over time and only considered the MELD/PELD when a candidate was first active on the waitlist, and we did not account for differences in center-level acceptance of livers. Livers are not actually distributed to each transplant center proportionally according to our defined MELD-weighted demand but are offered intermittently as each liver becomes available to the candidate with highest priority within the geographic unit assigned to that donor hospital. These considerations reflect that we did not simulate a patient-level allocation of organs, but rather we used a metric of supply/demand that is neither influenced by MELD score trajectories nor influenced by center acceptance practices. In a similar way, Rana et al. used the ratio of listed candidates to available allografts to characterize liver availability and found that liver availability was weakly correlated to waitlist mortality and survival after transplant.(4)

Testing our heterogeneous circles in a simulated allocation model incorporating waitlist candidate characteristics and center-level behaviors to estimate impact on MELD at transplant and number of lives rescued with transplant is the natural next step in assessing the effectiveness of our heterogeneous circles. The SRTR’s liver simulated allocation model (LSAM) was not designed to handle heterogeneous circles, and so testing our circles would involve a redesign of LSAM, which is beyond the scope of this paper. This limitation means we are unable to directly compare our heterogeneous circles system with the tiered acuity circles used today. However, heterogeneous circles yielded significantly less disparity than homogeneous circles of any size. With this understanding, we could design some or all of the tiers of an acuity-like system to be heterogeneous.

Our metrics of demand and supply are necessarily imperfect. Our metric of liver demand depends on the number of people who first became active on the waitlist, which can be influenced by referral patterns and listing practices as well as insurance and access to health care generally. Listing practices likely differ the most for low-MELD candidates because in some areas, low-MELD candidates are very unlikely to receive offers. We weighted candidates based on their MELD/PELD score when they first became active on the waitlist so that candidates with a higher MELD/PELD contributed more to a transplant center’s demand than those with lower MELD/PELD. Interestingly, we found that our definition of demand is highly correlated with the simpler definition of demand used in our work(3)—the number of candidates who first achieved a MELD/PELD of at least 15 (Fig. 8).

FIG. 8.

Comparing definitions of demand. The x-axis indicates demand as the number of candidates listed with, or who first achieved, a MELD/PELD 15 during the study period, whereas the y-axis indicates the MELD-weighted demand. Each point represents a transplant center. For this work it is only the relative demand and not the magnitude of the demands that matter. Therefore the high value suggests that these definitions are roughly equivalent.

Median allocation MELD varies across transplant centers in the same DSA, which demonstrates that center decisions impact transplant rates even when centers have similar access to livers.(10) Higher listing rates and listing of higher MELD candidates are associated with higher transplant and organ utilization rates within and between DSAs, suggesting that transplant centers should try to expand access to listing.(11) On the supply side, donor authorization rates range from 63.5% to 89.5% across DSAs,(12) and these also affect our supply/demand ratio metric. Our optimization method can be applied to design circles that equalize any metrics of supply and demand that policymakers deem appropriate, for instance, using eligible deaths instead of livers donated to measure supply or using raw counts of end-stage liver disease deaths to measure demand.

Whatever metrics are used, supply and demand can change over time, possibly nullifying the efficacy of our heterogeneous circles. To account for this, we designed our circles using data from July 2013 to June 2015 and tested them on data from July 2015 to June 2017, finding that our heterogeneous circles still outperformed all homogeneous circles. The Final Rule states that allocation policies “shall be reviewed periodically and revised as appropriate.” Our heterogeneous circles would need to be redesigned whenever the patterns of recovery and listing have changed to such an extent that the system no longer yields equitable organ distribution.

Large homogeneous circles create logistical burdens on transplant centers that do not need them, whereas small homogeneous circles increase geographic disparity. We have shown that using carefully designed heterogeneous circles can reduce geographic disparity in liver supply/demand ratios when compared with homogeneous circles of radius ranging from 150 to 1,000 nm, and they do so with a median circle size of only 326 nm.

Acknowledgment:

The data reported here have been supplied by the Hennepin Healthcare Research Institute as the contractor for the SRTR. The interpretation and reporting of these data are the responsibility of the authors and in no way should be seen as an official policy of or interpretation by the SRTR, OPTN/UNOS, or the United States Government.

Supported by grant numbers R01DK111233 (to D. L. S.), K24DK101828 (to D. L. S.), and F32DK117563 (to A. B. K.) from the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK).

Abbreviations:

- DSA

donor service area

- MELD

Model for End-Stage Liver Disease

- nm

nautical mile

- OPTN

Organ Procurement and Transplantation Network

- PELD

Pediatric End-Stage Liver Disease

- SRTR

Scientific Registry of Transplant Recipients

Footnotes

The AASLD Public Policy Corner is a regular publication of the AASLD Public Policy Committee highlighting key subject areas of AASLD’s public policy agenda. The Public Policy Committee advocates for AASLD members and their patients in front of key decision makers including legislators, regulatory agencies and key opinion leaders within the United States Government.

Under this formulation, we let i = 41 represent Status 1B candidates, and we let i = 42 represent Status 1A candidates.

Potential conflict of interest: Nothing to report.

REFERENCES

Author names in bold designate shared co-first authorship.

- 1).Sigounas G. Letter to Sue Dunn. North Bethesda, MD: U.S. Department of Health Resources and Services Administration, United Network for Organ Sharing; 2018. https://unos.org/wp-content/uploads/unos/HRSA_to_OPTN_Organ_Allocation_20180731.pdf. Accessed December 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 2).Gentry SE, Massie AB, Cheek SW, Lentine KL, Chow EH, Wickliffe CE, et al. Addressing geographic disparities in liver transplantation through redistricting. Am J Transplant 2013;13:2052–2058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3).Haugen CE, Ishaque T, Sapirstein A, Cauneac A, Segev DL, Gentry S. Geographic disparities in liver supply/demand ratio within fixed-distance and fixed-population circles. Am J Transplant 2019;19:2044–2052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Rana A, Kaplan B, Riaz IB, Porubsky M, Habib S, Rilo H, et al. Geographic inequities in liver allograft supply and demand: Does it affect patient outcomes? Transplantation 2015;99:515–520. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Mitchell M. An Introduction to Genetic Algorithms. Cambridge, MA: MIT Press; 1998. [Google Scholar]

- 6).Gentry S, Chow E, Massie A, Segev D. Gerrymandering for justice: Redistricting U.S. liver allocation. Interfaces 2015;45:462–480. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7).Kilambi V, Mehrotra S. Improving liver allocation using optimized neighborhoods. Transplantation 2017;101:350–359. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8).Parikh ND, Marrero WJ, Sonnenday CJ, Lok AS, Hutton DW, Lavieri MS. Population-based analysis and projections of liver supply under redistricting. Transplantation 2017;101: 2048–2055. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Gentry SE, Chow EK, Wickliffe CE, Massie AB, Leighton T, Segev DL. Impact of broader sharing on the transport time for deceased donor livers. Liver Transpl 2014;20:1237–1243. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Croome KP, Lee DD, Burns JM, Keaveny AP, Taner CB. Intraregional model for end-stage liver disease score variation in liver transplantation: Disparity in our own backyard. Liver Transpl 2018;24:488–496. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Adler JT, Dong N, Markmann JF, Schoenfeld D, Yeh H. Role of patient factors and practice patterns in determining access to liver waitlist. Am J Transplant 2015;15:1836–1842. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Goldberg DS, French B, Abt PL, Gilroy RK. Increasing the number of organ transplants in the United States by optimizing donor authorization rates. Am J Transplant 2015;15:2117–2125. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]