During the 2019 Coronavirus (COVID19) pandemic, 48% of Americans reported delays in accessing health care [1]. Emergency Department (ED) visits decreased by 42% in the first months of the pandemic [2]. Increases in late presentations [3,4] and out of hospital cardiac arrests [5] seen during the pandemic may represent delays in accessing care. This may have been driven by widespread public health messaging from healthcare systems to avoid unnecessary ED and hospital visits [6]. While anecdotal evidence exists, few studies have examined who delayed ED care [7] or examined consequences of such delays [[3], [4], [5],8]. In this study we assessed whether ED patients delayed their visit due to concerns regarding the COVID19 pandemic and characterized those who reported a delay. We assessed if delays were associated with greater illness severity as measured by need for further acute medical treatment or evaluation.

We conducted an observational, prospective study at a tertiary academic ED from April 26 through August 25, 2020. Its annual census is approximately 45,000 visits and in 2019 had 14,861 visits during the same timeframe. The ED is in a region that saw a peak of 161 daily new COVID19 cases during the study period [9]. We added the question “Did you delay coming to the ER or seeing a doctor for your problem today either because of the shelter-in-place orders or concerns about coronavirus?” to the triage process. We obtained study variables from the electronic health record. Our project was approved by our Institutional Review Board. Reporting adheres to STROBE guidelines [10].

We enrolled all ED encounters during the study period. We included encounters even if a response to the triage question was not recorded. If the patient had more than one ED visit in a day, we only included their response at the first encounter.

The primary outcome was need for further medical evaluation or treatment from the ED, measured by ED disposition. We obtained patient age, gender, race/ethnicity, insurance type, emergency severity index (ESI) assignment, ED diagnosis, ED disposition, level of care from ED, documentation of critical care time in the ED, and COVID19 diagnosis (PCR nasopharyngeal swab). We defined ED diagnosis by ICD-10 code. We used established methods to identify visits' ICD-10 codes that represent emergency care sensitive conditions (ECSCs) - conditions that are most sensitive to timely, quality emergency care [11].

We performed descriptive analyses stratified by self-reported delay in accessing healthcare and evaluated the proportion of patients who reported a delay over time. Next, adjusting for observable confounders, and to account for patient-level clustering, we performed mixed effect bivariate and adjusted logistic regressions for our outcome-need for further acute medical treatment or evaluation-as defined by an ED disposition of hospital admission, admission to the operating room, transfer, or expired in the ED. We used Stata statistical software version 16 (StataCorp) for all analysis.

There were 11,001 unique patient encounters during the study period. We excluded 93 for having had a previous encounter on the same day, leaving 10,908. 8643 (79%) of patients did not report a delay, compared to 954 (9%) who did. No answer was recorded for 1311 (12%) of encounters (Table 1 ) and these visits were more likely to be self-pay, categorized as ESI 4, and have an ED disposition of eloped, left against medical advice (AMA), or left without being seen (LWBS). Among those who answered the question, men, non-Hispanic White patients, and those without private insurance were less likely to self-report a delay in presentation compared to their counterparts (Table 1). Of respondents, those with ESI 1 or 2 were less likely to report delays in accessing care than those with ESI 3 (p < 0.001), as were those with an ECSC diagnosis (p = 0.001). Those who self-reported delays were significantly more likely to be discharged from the hospital than those who did not (p < 0.001).

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics of included patient encounters, single center, April 26 – August 25, 2020

| Total N = 10,908 |

No N = 8643 (79%) |

Yes N = 954 (9%) |

Unknown N = 1311 (12%) |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 52 (20) | 52 (20) | 50 (18) | 50 (19) |

| Sex | ||||

| Female | 5080 (47%) | 3965 (46%) | 553 (58%) | 562 (43%) |

| Male | 5819 (53%) | 4672 (54%) | 401 (42%) | 746 (57%) |

| Missing | 9 (0%) | 6 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 3 (0%) |

| Race/Ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 4764 (44%) | 3852 (45%) | 378 (40%) | 534 (41%) |

| African-American/Black | 1728 (16%) | 1348 (16%) | 154 (16%) | 226 (17%) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1332 (12%) | 1062 (12%) | 118 (12%) | 152 (12%) |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 1939 (18%) | 1512 (17%) | 186 (19%) | 241 (18%) |

| Other | 1145 (10%) | 869 (10%) | 118 (12%) | 158 (12%) |

| Insurance | ||||

| Private | 3223 (30%) | 2535 (29%) | 366 (38%) | 325 (25%) |

| Medicaid | 3038 (28%) | 2388 (28%) | 256 (27%) | 394 (30%) |

| Medicare | 3602 (33%) | 2939 (34%) | 267 (28%) | 396 (30%) |

| Self-Pay | 623 (6%) | 446 (5%) | 35 (4%) | 142 (11%) |

| Other | 422 (4%) | 345 (4%) | 30 (3%) | 47 (4%) |

| ESI | ||||

| 1 | 64 (1%) | 40 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 24 (2%) |

| 2 | 2193 (20%) | 1831 (21%) | 164 (17%) | 198 (15%) |

| 3 | 6640 (61%) | 5295 (61%) | 673 (71%) | 672 (51%) |

| 4 | 1631 (15%) | 1254 (15%) | 110 (12%) | 267 (20%) |

| 5 | 250 (2%) | 208 (2%) | 7 (1%) | 32 (2%) |

| Unknown | 13 (1%) | 17 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 118 (9%) |

| ECSCa | ||||

| No | 9074 (83%) | 7116 (82%) | 825 (86%) | 1133 (86%) |

| Yes | 1834 (17%) | 1527 (18%) | 129 (14%) | 178 (14%) |

| ED Disposition | ||||

| Discharge | 6964 (64%) | 5442 (63%) | 657 (69%) | 865 (66%) |

| Admit | 3044 (28%) | 2557 (30%) | 256 (27%) | 231 (18%) |

| Expired | 15 (0%) | 5 (0%) | 0 (0%) | 10 (1%) |

| Transferred | 252 (2%) | 230 (3%) | 8 (1%) | 14 (1%) |

| AMA, Eloped, LWBS, Unspecified | 642 (6%) | 405 (5%) | 34 (4%) | 203 (15%) |

| Level of Care from ED | ||||

| Discharged or Transferred | 7730 (71%) | 5960 (69%) | 688 (72%) | 1064 (81%) |

| Floor or Observation | 1931 (18%) | 1631 (19%) | 177 (19%) | 123 (9%) |

| Procedure | 122 (1%) | 104 (1%) | 11 (1%) | 7 (1%) |

| Step-down Unit | 735 (7%) | 631 (7%) | 58 (6%) | 46 (4%) |

| ICU or Expired in ED | 390 (4%) | 299 (3%) | 20 (2%) | 71 (5%) |

| Any ED Critical Care Time Documented | 525 (5%) | 426 (5%) | 16 (2%) | 83 (6%) |

| In Hospital Mortality | 123 (1%) | 91 (1%) | 2 (0%) | 30 (2%) |

| COVID19 Diagnosis | 178 (2%) | 134 (2%) | 22 (2%) | 22 (2%) |

Emergency Care Sensitive Condition.

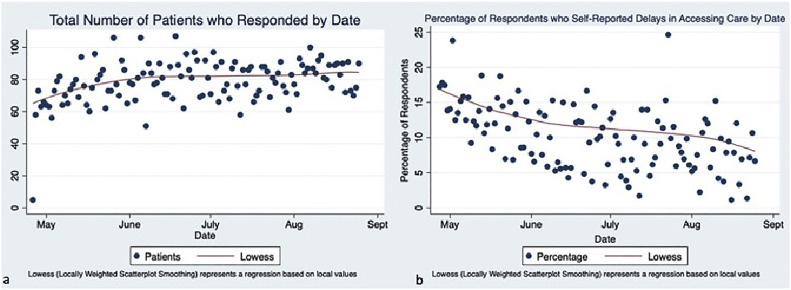

The percentage of patients reporting a delay declined during the study period:13.4% reported a delay in April–May, 9.4% in July, 9.2% in July and 7% in August (p < 0.01). (Fig. 1 ).

Fig. 1.

Trends in patient volume and self-reported delay in accessing health care over time.

Emergency Department patients over time from April 26, 2020 to August 25, 2020. (a) Total number of patients who responded to the triage question “Due to the COVID 19 pandemic, did you delay accessing health care prior to your ED visit today?”. (b) Percentage of respondents per day who responded “Yes” to the screening triage question.

After adjusting for age, gender, race, insurance type, visit date, and presence of ECSC diagnoses, visits with a self-reported a delay showed a trend towards reduced odds of the outcome of admission to hospital, OR, transfer, or expired in the ED (0.80 (0.62–1.03)) (Table 2 ).

Table 2.

Bivariate and multivariate logistic regression of self-reported delay and observed confounders on odds of admission to hospital, operating room, transfer or death in the ED.

| Admission to Hospital, Operating Room, Transfer or Death in ED |

||

|---|---|---|

| Unadjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | Adjusted Odds Ratio (95% CI) | |

| Reported Delay in Accessing Care | ||

| No Reported Delay | Reference | Reference |

| Self-Reported Delay | 0.70 (0.54–0.89) | 0.80 (0.62–1.03) |

| Unknown if Delayed | 0.34 (0.27–0.43) | 0.37 (0.29–0.47) |

| Agea | 1.64 (1.56–1.72) | 1.26 (1.19–1.33) |

| Sex | ||

| Male | Reference | Reference |

| Female | 1.05 (0.91–1.23) | 1.03 (0.88–1.20) |

| Race | ||

| Non-Hispanic White | Reference | Reference |

| African-American/Black | 0.61 (0.48–0.77) | 0.75 (0.59–0.96) |

| Hispanic/Latinx | 1.03 (0.81–1.32) | 1.42 (1.10–1.83) |

| Asian American/Pacific Islander | 1.67 (1.34–2.05) | 1.35 (1.10–1.66) |

| Other | 0.66 (0.51–0.85) | 0.98 (0.75–1.28) |

| Insurance Type | ||

| Private | Reference | Reference |

| Medicaid | 1.05 (0.86–1.29) | 1.05 (0.85–1.29) |

| Medicare | 5.26 (4.19–6.59) | 2.04 (1.60–2.62) |

| Self-Pay | 0.11 (0.07–0.17) | 0.15 (0.09–0.24) |

| Other | 0.42 (0.28–0.64) | 1.40 (0.26–0.62) |

| Visit Date | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) | 1.00 (1.00–1.00) |

| ECSC Diagnosisb | 31.76 (22.50–44.82) | 22.12 (16.58–29.52) |

Centered around the mean age of 51.8 years and scaled by 10 years.

Emergency Care Sensitive Condition.

This is a single center, cross-sectional study of short duration, which limits generalizability. Self-reported delay is subjective and was not corroborated by chart review. A response to the triage screening question was not documented for 12% of the cohort, which could have biased results. Additional limitations include a lack of prior data on pre pandemic levels of self-reported delay and lack of adjustment for unmeasured confounders. Bias from survivorship may also be present.

ED volume was overall 26.0% lower than during this same period in 2019. While daily ED encounters increased over the study period, the daily percentage of encounters with reported delays decreased. In 2019, 0.37% of patients were classified as ESI 1, 19.24% as ESI 2, 58.66% as ESI 3, 18.08% ESI4, 2.05% ESI 5 (1.59% were unspecified) – similar to our cohort (Table 1), which indicates that acuity of visits did not change during this period of the pandemic.

Our findings, that ED patients had low rates of self-reported delays, that the proportion of those who delayed declined over the study period, and that delay was not associated with need for further medical care or evaluation could be explained, in part, by expanded access to primary and telehealth care created during the pandemic. We found that White patients were less likely to report delays compared to minoritized populations, which could represent more access to non-ED care or other services. It is also possible that the lack of significant COVID19 surge during the study leading to less fear in accessing health care, effective messaging by hospital system and local public health officials to encourage accessing care, or procedures to safeguard patients from COVID19 contributed to our findings.

Overall, these results indicate that ED patients may be able to appropriately self-triage in times of anticipated healthcare resource scarcity.

Sources of support

This research did not receive any specific grant from funding agencies in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Prior presentations

None.

Declaration of competing interest

VE, RCW, AAV, HKK, JF and MCR report no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Nearly Half Of Americans Delayed Medical Care Due To Pandemic . 2021. Kaiser Health News. n.d. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hartnett K.P., Kite-Powell A., DeVies J., Coletta M.A., Boehmer T.K., Adjemian J., et al. Impact of the COVID-19 pandemic on emergency department visits — United States, January 1, 2019–May 30, 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep. 2020;69:699–704. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6923e1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Schirmer C.M., Ringer A.J., Arthur A.S., Binning M.J., Fox W.C., James R.F., et al. Delayed presentation of acute ischemic strokes during the COVID-19 crisis. J Neurointerv Surg. 2020;12 doi: 10.1136/neurintsurg-2020-016299. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hammad T.A., Parikh M., Tashtish N., Lowry C.M., Gorbey D., Forouzandeh F., et al. Impact of COVID-19 pandemic on ST-elevation myocardial infarction in a non-COVID-19 epicenter. Catheter Cardiovasc Interv. 2020 doi: 10.1002/ccd.28997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Singh S., Fong H.K., Mercedes B.R., Serwat A., Malik F.A., Desai R. COVID-19 and out-of-hospital cardiac arrest: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Resuscitation. 2020;156:164–166. doi: 10.1016/j.resuscitation.2020.08.133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wong L., Hawkins J., Langness S., Murrell K., Iris P., Sammann A. Where are all the patients? Addressing Covid-19 fear to encourage sick patients to seek emergency care | catalyst non-issue content. NEJM Catal. 2020 https://catalyst.nejm.org/doi/full/10.1056/CAT.20.0193 [Google Scholar]

- 7.Nab M., van Vehmendahl R., Somers I., Schoon Y., Hesselink G. Delayed emergency healthcare seeking behaviour by Dutch emergency department visitors during the first COVID-19 wave: a mixed methods retrospective observational study. BMC Emerg Med. 2021;21:1–9. doi: 10.1186/s12873-021-00449-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rucker D.W., Brennan T.A., Burstin H.R. Delay in seeking emergency care. Acad Emerg Med. 2001;8:163–169. doi: 10.1111/j.1553-2712.2001.tb01282.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.COVID-19 Cases and Deaths DataSF | City and County of San Francisco. 2021. https://data.sfgov.org/stories/s/dak2-gvuj (accessed July 1, 2021)

- 10.STROBE Statement Available checklists. 2021. https://strobe-statement.org/index.php?id=available-checklists (accessed March 24, 2021)

- 11.Vashi A.A., Urech T., Carr B., Greene L., Warsavage T., Hsia R., et al. Identification of emergency care-sensitive conditions and characteristics of emergency department utilization. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2:198642. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.8642. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]