Abstract

Background

A multiphased mixed-methods study was performed to develop and validate a comprehensive patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) for arm lymphedema in women with breast cancer (i.e., the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module).

Methods

Qualitative interviews (January 2017 and June 2018) were performed with 15 women to elicit concepts specific to arm lymphedema after breast cancer treatment. Data were audio-recorded, transcribed, and coded. Scales were refined through cognitive interviews (October and Decemeber 2018) with 16 patients and input from 12 clinical experts. The scales were field-tested (October 2019 and January 2020) with an international sample of 3222 women in the United States and Denmark. Rasch measurement theory (RMT) analysis was used to examine reliability and validity.

Results

The qualitative phase resulted in six independently functioning scales that measure arm symptoms, function, appearance, psychological function, and satisfaction with information and with arm sleeves. In the RMT analysis, all items in each scale had ordered thresholds and nonsignificant chi-square p values. For all the scales, the reliability statistics with and without extremes for the Person Separation Index were 0.80 or higher, Cronbach’s alpha was 0.89 or higher, and the Intraclass Correlation Coefficients were 0.92 or higher. Lower (worse) scores on the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity scales were associated with reporting of more severe arm swelling, an arm problem caused by cancer and/or its treatment, and wearing of an arm sleeve in the past 12 months.

Conclusions

The LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module can be used to measure outcomes that matter to women with upper extremity lymphedema. This new PROM was designed using a modern psychometric approach and, as such, can be used in research and in clinical care.

Breast cancer treatment is the most common cause of upper extremity lymphedema in Western countries.1 Risk factors for the development of arm lymphedema are axillary lymph node dissection (ALND), sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB), and radiation therapy of the axilla, or a combination of these therapeutic methods.

The overall incidence of breast cancer-related arm lymphedema has ranged between 14 and 21%.1–3 Findings from a prospective cohort study of 2171 women investigating time course and incidence of breast cancer-related lymphedema identified that patients receiving ALND with radiation therapy were at a greater risk for the development of lymphedema (31.2 %) than those with ALND alone (24.6 %) or with SLNB plus radiation therapy (12.2 %).2 Furthermore, early onset of lymphedema at less than 12 months postoperatively was associated with having ALND, whereas onset at 12 months or later was associated with having radiation therapy.2

Arm lymphedema is a debilitating diagnosis that may impose a significant detriment to a patient’s health-related quality of life (HRQOL) due to symptoms (e.g., swelling, pain, infection) and reduced arm function.4,5 The rapidly emerging field of lymphedema research has had little consensus on the most suitable metric for measuring outcomes. Clinicians commonly use limb volume and circumference, but these metrics do not capture the HRQOL burden of arm lymphedema from the patient perspective.6,7

To better understand and measure outcomes that matter to patients with arm lymphedema, a valid and reliable patient-reported outcome measure (PROM) is needed. Given that arm lymphedema affects how patients function and feel, information captured through the use of a PROM may be a better indicator of disease than traditional clinical metrics.6

Currently, 14 lymphedema-specific PROMs have been used to measure upper extremity lymphedema outcomes from the patient perspective.8 A systematic literature review identified that 13 of the 14 PROMs were developed with limited input from patients.8 Patient involvement in the development of a PROM is considered crucial to ensuring that its content is comprehensive and relevant to patients (i.e., content validity).9,10 The systematic literature review also identified that the quality of each PROM was low to moderate in terms of meeting the criteria for reliability and validity as set out in the COnsensus‐based Standards for the selection of health Measurement Instruments (COSMIN).11

To address the shortcomings in existing PROMs for upper extremity lymphedema, our team developed the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module. This PROM was developed to complement the BREAST-Q that we previously developed to measure HRQOL and patient satisfaction among women with breast surgery.12 This study aimed to describe the development and psychometric validation of the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module.

Methods

Best practice guidelines for the development of a PROM were used to guide this multi-phased mixed-methods study.10,13–17 Phase 1 involved qualitative patient interviews to elicit concepts. Interpretive description was used to inform the qualitative approach.18 Subsequently, cognitive interviews with patients and expert input were used to refine the new scales content. In phase 2 (quantitative), a field-test was performed and Rasch measurement theory (RMT)19,20 analysis was used for item reduction and to examine the psychometric properties of each scale.

Research Ethics

For phase 1, approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Boards at McMaster University (Hamilton, ON, Canada), Toronto General Hospital (TGH) (Toronto, ON, Canada), Memorial Sloan Kettering Cancer Center (MSK) (New York, NY, USA), and Brigham and Women’s Hospital (BWH) (Boston, MA, USA). In Denmark, the study was reported to and approved by the Region of Southern Denmark and included on the list of Health Research for data protection safety.

Written consent was obtained from all the participants before each qualitative and cognitive interview. The participants in Canada and the United States were sent a $50 (CAD, USD) gift card to thank them for their participation.

For phase 2, in the United States, approval was obtained from BWH and the Scientific Advisory Committee of the Love Research Army (LRA; formerly known as the Army of Women), an online non-profit community started by the Dr. Susan Love Research Foundation in 2008 that connects breast cancer researchers to women with and without breast cancer.21 An email describing the study aims was sent to LRA members. Completion of the study questionnaire implied consent.

For Denmark, phase 2 of the study was approved by the Region of Southern Denmark and included on the list of Health Research for data protection safety. Ethics approval from the Regional Committee on Health Research Ethics was not required because the study involved completion of a questionnaire. An email invitation was sent to the electronic secure mailbox (Eboks) of potential participants. Informed consent to take part in the study was obtained electronically in REDCap.

Phase 1: Qualitative Interview

Sample and Recruitment

Women who were 18 years of age or older with a breast cancer diagnosis and fluent in English were invited to participate in a qualitative interview as part of a larger study to develop new scales for the BREAST-Q. A purposive sampling approach was used to ensure that participants varied by age and breast cancer stage (stages 0–4), as well as by surgical (i.e., breast-conserving therapy, mastectomy with/without reconstruction) and nonsurgical (i.e., adjuvant or neoadjuvant) breast cancer treatments. Data from the subset of women in the sample who reported arm lymphedema were used to develop the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module.

Health care professionals described the study to potential participants in clinics or by telephone. Permission was obtained to share contact information with the research team. Interviews were scheduled and took place by phone or face-to-face at a time that was convenient to each participant.

Concept Elicitation

Interviews were performed by experienced qualitative researchers who followed a semi-structured interview guide with open-ended questions. The participants were asked to discuss how lymphedema and its treatment influenced their physical, psychological, and social well-being, as well as their overall HRQOL. The interviews were audio-recorded and transcribed verbatim.

To establish rigor, data collection and analysis took place concurrently so that new concepts elicited from participants could be added to the interview guide. Furthermore, the interviews were coded by two coders independently, and regular team meetings were used to review coding. Multiple levels of codes (top-level domains and themes) were applied to the text. Codes were created inductively through the generation of new codes and deductively through the application of relevant codes from the BREAST-Q conceptual framework.12 Recruitment continued until redundancy of concepts elicited through the interviews was achieved.

Participant quotes and associated codes were transferred from Microsoft Office Word to Excel for further refinement of themes and subthemes using constant comparison. In Excel, an item pool was developed for use in scale development. Scales covered key concepts elicited from the participants. Each scale was given instructions, a time frame for answering, and a set of response options.

Scale Development and Refinement

Patient and expert input was used to establish content validity of the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module. A semi-structured cognitive interview guide was used with questions and probes to determine whether the content of each scale (i.e., instructions, recall period, item set, response options) was comprehensive, relevant, and comprehensible.15 Participants were asked to suggest missing concepts. Women with breast cancer-related lymphedema from Canada, the United States, and Denmark 18 years of age or older who could speak and read in English or Danish, were invited to participate in the cognitive interviews, which used the think-aloud approach.22–24 Interviews and analyses were performed by skilled qualitative researchers and took place in rounds to enable the refinement of scale content between rounds.

Experts known to our team who treat patients with arm lymphedema were invited to provide feedback on the comprehensiveness and relevance of the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module content. An email invitation was sent by a member of the research team with an attached PDF copy of the lymphedema scales. A reminder email was sent after 1-week. Experts were asked to provide written feedback via email and to add missing concepts. The input from the experts was analyzed descriptively by two researchers with the results used to refine the scales.

Elsewhere we describe the methods and results of a linguistic validation study to translate the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module into Danish.25 The scales were translated into Danish according to the International Society for Pharmacoeconomics and Outcomes Research26 and World Health Organization27 guidelines. Feedback from patients and experts provided additional evidence of the scales’ content validity.

Phase 2: Field-Test Study

Sample and Recruitment

The analysis included data from two samples as follows:

Love Research Army

The LRA study was performed as part of a larger study to develop new scales for the BREAST-Q. The study was open to women 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of breast cancer who could read English. The LRA members were sent an electronic recruitment email (e-blast) containing a description of the study and the eligibility criteria. Women who agreed to participate were directed to a REDCap survey28 designed by our team and hosted at BWH.

The REDCap survey included demographic and clinical questions, new BREAST-Q scales and the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module. Targeted clinical questions and branching logic were used to ensure that only women with arm lymphedema completed the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity scales. The LRA participants were invited to take part in a test-retest (TRT) study. Those who provided their email were automatically sent a URL link 3 weeks after the initial survey, with one reminder sent after 2 days.

-

2.

Danish National Health Data Authority

In Denmark, a list of all patients 18 years of age or older with a diagnosis of both breast cancer and arm lymphedema in the past 12 years was obtained from the Danish National Health Data Authority. An invitation with written information about the study and a REDCap public link to the survey was sent to patients’ Eboks. The REDCap database was hosted by the Open Patient Data Explorative Network.29 Patients were invited to use the URL provided to access and complete clinical and demographic questions as well as the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module. Two reminders were sent 7 and 14 days after the initial invitation.

Data Analysis

In this study, RMT analysis was performed using RUMM2030 software and the unrestricted Rasch model for polytomous data (RUMM version 2030; RUMM Laboratory Pty Ltd., Duncraig, Western Australia, 1998-14). The RMT analysis involved a series of diagnostic tests, described in detail elsewhere.30 Briefly, a set of statistical and graphic tests, were used to identify items and scales that did not work as hypothesized.19 Scales that work have a set of items that line up to map out a single continuum. RMT analysis uses the chi-square statistic to examine both item fit and the overall model fit. Because this test is highly sensitive to sample size, we adjusted the sample to 500. We also applied Bonferroni corrections to account for multiple comparisons.

Ordering of Item Thresholds

Threshold maps were examined to determine whether response options (e.g., very dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, somewhat satisfied, very satisfied) were used appropriately. Disordered thresholds indicate problems in comprehension, or that the response options do not work as intended.

Item Fit

We examined individual item fit and overall fit of the data to the Rasch model.31,32 Indicators of fit were inspected and interpreted together. Item fit was evaluated statistically by whether fit residuals were within – 2.5 and + 2.5 and had nonsignificant chi-square values after Bonferroni adjustment. Fit residuals also were inspected graphically to determine whether item characteristic curves showed agreement between observed and expected scores.31,32

Local Dependency

We examined residual correlations to identify their influence on the Person Separation Index (PSI, reliability). Any pairs of items with a residual correlation of 0.30 or higher were included in a subtest to determine their impact on scale reliability.33–35

Targeting

Scales should measure the construct as experienced by the sample. We examined graphic displays (person-item threshold distributions) of item and person spread to determine whether these overlapped. We also computed the proportion of the sample that scored outside the range of measurement.

Differential Item Function (DIF)

We examined whether subgroups in the sample responded differently to items in a scale despite having similar level of the construct measured. DIF was examined for dataset (USA and Danish) and age group (18 to 49, 50 to 59, 60 to 69, ≥ 70 years). For each variable, we performed DIF three times with random samples drawn to match the smallest subgroup. The DIF then was performed with and without adjustment of the overall sample in the analysis to 500. Any items that evidenced significant DIF in the unadjusted analysis were split on the sample characteristic. The person locations based on the original and split analyses were correlated to determine whether the DIF had any impact on scale scoring.32

Reliability

The PSI and Cronbach alpha36 reliability coefficients were determined within RUMM2030. Values of 0.70 or higher were considered acceptable.37

From the final models for each scale, the Rasch scores were obtained and transformed from 0 (worst) to 100 (best). The following statistical tests were performed in SPSS version 26.0 (IBM Corporation, Armonk NY, USA for Windows/Apple Mac).

1. Test-Retest Reliability. We used the transformed scores of 0 to 100 to examine test-retest reliability. The participants were asked if anything had changed with their health or in their life since they completed the questionnaire (response options: yes, no). Those who said yes were excluded from the TRT analyses. We computed two-way random Intraclass Correlation Coefficients (ICCs) with the test-retest data. ICC values greater than 0.70 were considered acceptable.38

2. Data Quality. We examined scale-level missing data and the proportion of patients to score at the floor and ceiling.

3. Construct Validity. We examined the normality of the data by examining kurtosis and skewness.39 Data that exceeded ± 2.0 were examined using nonparametric statistics.39 We tested the following hypotheses. First, we expected that correlations between the scales measuring similar, related but dissimilar, and unrelated constructs would meet the COSMIN guidelines for construct validity (i.e., correlations should be ≥0.50 for similar constructs, 0.30 to 0.50 for related but dissimilar constructs, and < 0.30 for unrelated constructs).11 Second, we expected that participants’ scale scores would be incrementally associated with severity (none, mild, moderate, severe) of self-reported arm swelling. Third, we expected that participants’ scale scores would be incrementally associated with having a self-reported arm problem (none, minor, major) as a result of breast cancer, treatment, or both. Finally, we expected that scale scores would be lower for women who reported that they wore a compression sleeve in the past 12 months compared with those who did not.

Results

Phase 1: Qualitative Phase

Data collection took place between January 2017 and June 2018. Qualitative interviews were performed with 58 patients as part of the larger BREAST-Q study. Data from 15 participants with arm lymphedema were used to develop the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module scales. Those with arm lymphedema were mainly 40 to 74 years of age. The participants included 13 white patients and 10 married patients. Most of the participants had a mastectomy (n = 10) and a history of combination treatment with chemotherapy, radiotherapy, or endocrine therapy (n = 7).

Analysis resulted in the development of a framework of concepts important in arm lymphedema. The framework included top-level domains with two or more of the following major themes: arm appearance (body image, characteristic, clothing), physical (function, symptoms), psychological (distress, impact), social (support, function, relationships), and experience of care (lymphedema information, arm sleeve). The item pool was used to develop content for five LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module scales as follows: function, symptoms, appearance, life impact, and information. Each scale was assigned instructions, a time frame for responding, and four response options that measured severity (symptoms, life impact), bother (appearance), difficulty (function), and satisfaction (information).

To establish content validity further, we performed 16 cognitive interviews of patients with breast cancer who had arm lymphedema. Interviews took place in three rounds between October and December 2018. Round 1 included two U.S. participants; round 2 included 10 Danish participants; and round 3 included four U.S. participants. The sample included women 38 to 74 years of age who were mainly white (n = 16) and married (n = 11). Most of the participants had a mastectomy (n = 10), ALND (n = 14) and a history of a combination of chemotherapy, radiotherapy, and endocrine therapy (n = 11).

Feedback was obtained from 12 of 22 invited multi-disciplinary experts after round 2 (response rate, 55 %). The experts represented four countries (Canada, Denmark, Poland, United Kingdom) and included eight plastic surgeons, two breast surgeons, a medical oncologist, and a nurse practitioner.

In round 1, the participants reviewed 57 items in five scales (symptoms, function, appearance, life impact, and information). Two new scales (psychological, arm sleeves) were added after round 1 participant feedback. The psychological and arm sleeve scales measured whether lymphedema affects how participants feel (response options: always, often, sometimes, never) and satisfaction with the arm sleeve (response options: very dissatisfied, somewhat dissatisfied, somewhat satisfied, very satisfied), respectively. The final set of items was tested in round 3, which resulted in a total of 110 items in the following scales finalized for the field-test: symptoms (n = 20 items), function (n = 19 items), appearance (n = 14 items), life impact (n =11 items), psychological (n = 19 items), information (n = 13 items), and arm sleeve (n = 14 items).

The LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module was translated into Danish.25 The scales were reviewed by an expert panel consisting of the primary investigator leading the translation process, two professional bilingual translators, a breast surgeon/plastic surgeon, a physiotherapist specialized in lymphedema treatment, a medical doctor specialized in lymphedema research, and a medical doctor specialized in PROM research. This was followed by cognitive debriefing interviews with 10 women who had arm lymphedema. The feedback received by the patients and the expert panel confirmed that the scales were comprehensive and comprehensible and included highly relevant questions.

Phase 2: Quantitative Phase

Field-test data were collected between October 2019 and January 2020. A total of 1717 LRA members opened the REDCap link and self-selected themselves to be eligible for the study. Among these members, 364 had a diagnosis of lymphedema and completed at least one of the lymphedema scales. Of the 364 participants, 79 also provided data for the TRT.

In Denmark, 8139 women with breast cancer and arm lymphedema were identified. Of these women, 6850 used Eboks and were invited to participate. Responses were obtained from 3945 women (57.6 %). Of these women, 1087 were excluded from the study (426 declined to participate, 298 did not have lymphedema, 363 completed only the clinical/demographic information). After these exclusions, 2858 Danish participants were included in the analysis. Sample characteristics for the combined sample of 3222 participants are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of the 3222 participants in the field-test sample

| n | % | |

|---|---|---|

| Country | ||

| Denmark | 2858 | 88.7 |

| USA | 364 | 11.3 |

| Age group (years) | ||

| ≤49 | 322 | 10.0 |

| 50–59 | 854 | 26.5 |

| 60–69 | 1037 | 32.2 |

| ≥70 | 1009 | 31.3 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||

| Under/normal weight (<25) | 1226 | 38.0 |

| Overweight (25–29) | 1107 | 34.4 |

| Obese (≥30) | 877 | 27.2 |

| Missing | 12 | 0.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||

| White | 2806 | 87.1 |

| Other | 416 | 12.9 |

| Relationship status | ||

| Married/common-law | 2349 | 73.0 |

| Separated/divorced | 235 | 7.3 |

| Widowed | 285 | 8.8 |

| Single, never married | 336 | 10.4 |

| Other | 17 | 0.5 |

| Education status | ||

| Some high school | 313 | 9.7 |

| Completed high school | 360 | 11.2 |

| Some college, trade, or university | 714 | 22.2 |

| Completed college, trade, or university | 1245 | 38.6 |

| Some Masters or Doctoral | 331 | 10.3 |

| Completed Masters or Doctoral | 164 | 5.1 |

| Other | 95 | 2.9 |

| Employment status | ||

| Retired | 1630 | 50.6 |

| Working full-time | 726 | 22.5 |

| Working part-time | 499 | 15.5 |

| Other | 367 | 11.4 |

| Treatment for breast cancer | ||

| None | 77 | 2.4 |

| Chemotherapy | 2447 | 76.0 |

| Radiation therapy | 2912 | 90.4 |

| Anti-estrogen therapy | 2303 | 71.5 |

| Targetted therapy | 593 | 18.4 |

| Arm swelling | ||

| None | 418 | 13.0 |

| Mild | 1346 | 41.8 |

| Moderate | 1070 | 33.2 |

| Severe | 356 | 11.0 |

| Missing | 32 | 1.0 |

| Lymphedema laterality | ||

| Unilateral | 3156 | 98.0 |

| Bilateral | 66 | 2.0 |

| Arm problem as a result of breast cancer and/or treatments | ||

| None | 335 | 10.4 |

| Minor | 2108 | 65.4 |

| Major | 779 | 24.2 |

| Time since lymphedema diagnosis (years) | ||

| ≤4 | 998 | 31.0 |

| 5–9 | 1183 | 36.7 |

| ≥10 | 1041 | 32.3 |

| Compression sleeve worn in the past 12 months to reduce or prevent swelling? | ||

| Yes | 2282 | 70.8 |

| No | 940 | 29.2 |

| Bothered by how arm(s) look overall? | ||

| Not at all | 1154 | 35.8 |

| A little | 1049 | 32.6 |

| Moderately | 604 | 18.7 |

| Extremely | 353 | 11.0 |

| Missing | 62 | 1.9 |

SN, sentinel node biopsy; ALND, axillary lymph node dissection

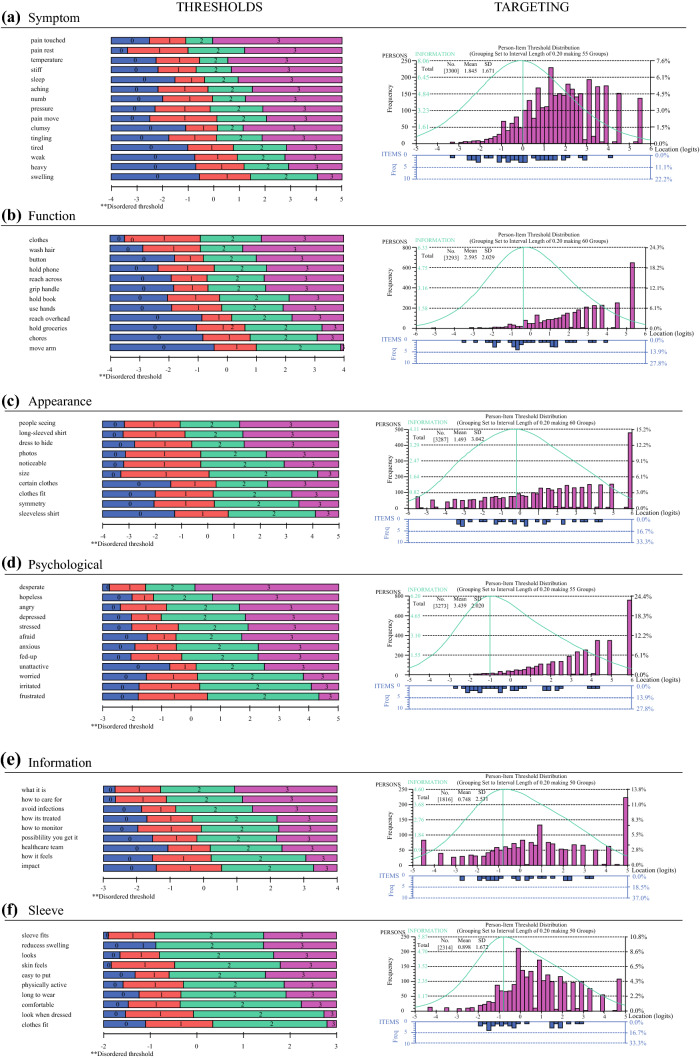

The RMT analysis led to a reduction of items from 110 to 68. Items were dropped due to either poor fit to the Rasch model or redundant content. All 68 items had properly ordered thresholds (Appendix 1) and nonsignificant chi-square p values after Bonferroni adjustment. Data fit the Rasch model for all six scales, with nonsignificant p values (Appendix 2). Item fit was within ± 2.5 for 27 of the 68 items. Scale level findings for the six scales that formed the item-reduced version of the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module are shown in Appendix 2, and item fit statistics are shown in Appendix 3. The proportion of the sample that scored on each scale is shown in Appendix 2. All but one scale (psychological) had at least 80 % of participants’ scores within the scale’s measurement. Targeting can be seen graphically in Appendix 1, which shows the person measurement and item locations for each scale.

Differential item function was evident for 31 items in the unadjusted analysis that compared the Danish and U.S. datasets and for 14 items by age group (Appendix 3). In the adjusted analysis, DIF was evident for 26 items by dataset and for 3 items by age group (Appendix 3). When the items that evidenced DIF in the unadjusted analysis were split by the relevant participant characteristics, Spearman correlations between the original and split-person locations indicated that DIF had a negligible impact (r ≥ 0.991 for all correlations).

The PSI values were 0.80 or higher (with and without extremes), and the Cronbach alpha values were 0.89 or higher (with and without extremes) (Appendix 2). One pair of items in each of the symptoms (swelling, heavy), function (hold phone, hold book), and appearance (photos, noticeable) scales had residuals that correlated greater than 0.30. A subtest performed on these three item pairs showed the impact on the PSI values to be marginal, with a maximum drop in PSI of less than 0.01 with and without extremes.

Test-retest data were provided by 79 of the participants. Five of the participants reported a change in their health or life since completing the scales and were excluded. Appendix 2 shows the ICC values with 95 % confidence intervals. The ICC values for the six scales was 0.92 or higher. The scale-level missing data value was low (≤ 1.4 %, see Appendix 2). Floor effects were low (≤ 4.3 %), and ceiling effects ranged from 4.1 % (symptoms) to 22.7 % (psychological) (Appendix 2). The mean grade reading levels for the items in each scale were between 2.5 (symptoms, sleeve) and 15.6 (psychological), and the grade reading levels for the instructions ranged from 3.7 (psychological) to 14.1 (information).

Table 2 shows the Pearson correlations between the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module scales. As hypothesized, the correlations between the scores on the four outcome scales were stronger with each other than with the two satisfaction scales. The correlations between the four outcome scales all met the level of >0.50 for related measures. The only correlations not in accordance with our hypothesized values, as per the COSMIN guidelines for construct validity, were the correlations between the arm sleeves scale and the symptoms, function, and psychological scales, which were higher than predicted.

Table 2.

Pearson correlations between the LYMPH-Q upper extremity module scales

| LYMPH-Q scales | R | n | Hypothesized relationship | Meets criteria | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Symptoms | Function | 0.774a | 3213 | Similar | Yes |

| Appearance | 0.591a | 3208 | Similar | Yes | |

| Psychological | 0.623a | 3194 | Similar | Yes | |

| Information | 0.207a | 1756 | Unrelated | Yes | |

| Arm sleeve | 0.373a | 2257 | Unrelated | No | |

| Function | Symptoms | 0.774a | 3213 | Similar | Yes |

| Appearance | 0.504a | 3206 | Similar | Yes | |

| Psychological | 0.575a | 3192 | Similar | Yes | |

| Information | 0.174a | 1753 | Unrelated | Yes | |

| Arm sleeve | 0.333a | 2255 | Unrelated | No | |

| Appearance | Symptoms | 0.591a | 3208 | Similar | Yes |

| Function | 0.504a | 3206 | Similar | Yes | |

| Psychological | 0.562a | 3191 | Similar | Yes | |

| Information | 0.222a | 1753 | Unrelated | Yes | |

| Arm sleeve | 0.411a | 2254 | Related but dissimilar | Yes | |

| Psychological | Symptoms | 0.623a | 3194 | Similar | Yes |

| Function | 0.575a | 3192 | Similar | Yes | |

| Appearance | 0.562a | 3191 | Similar | Yes | |

| Information | 0.246a | 1755 | Related but dissimilar | Yes | |

| Arm sleeve | 0.422a | 2253 | Unrelated | No | |

| Information | Symptoms | 0.207a | 1756 | Unrelated | Yes |

| Function | 0.174a | 1753 | Unrelated | Yes | |

| Appearance | 0.222a | 1753 | Unrelated | Yes | |

| Psychological | 0.246a | 1755 | Unrelated | Yes | |

| Arm sleeve | 0.361a | 1347 | Related but dissimilar | Yes | |

| Arm sleeve | Symptoms | 0.373a | 2257 | Unrelated | No |

| Function | 0.333a | 2255 | Unrelated | No | |

| Appearance | 0.411a | 2254 | Related but dissimilar | Yes | |

| Psychological | 0.422a | 2253 | Unrelated | No | |

| Information | 0.361a | 1347 | Related but dissimilar | Yes | |

ap ≤ 0.001; criteria: similar constructs, ≥ 0.50; related but dissimilar constructs, 0.30–0.50; unrelated constructs, <0.30

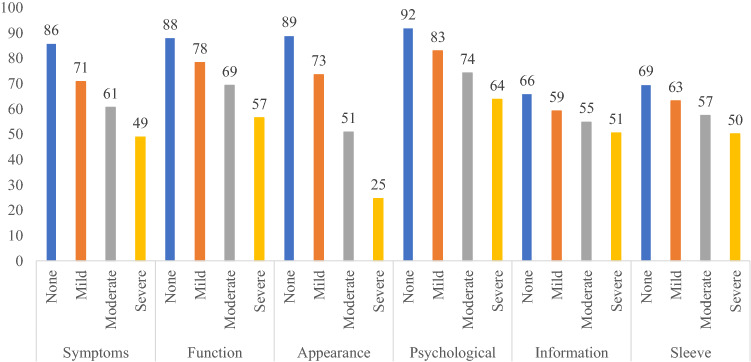

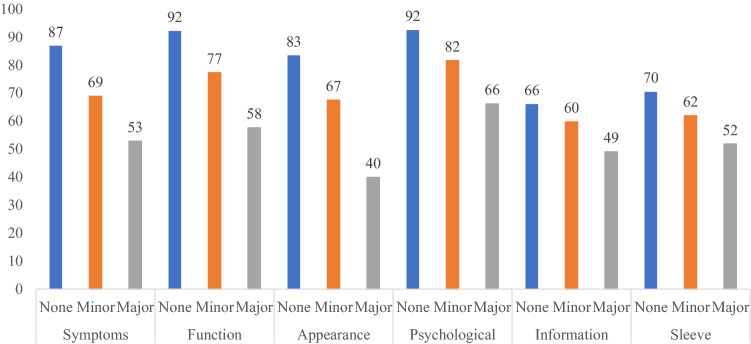

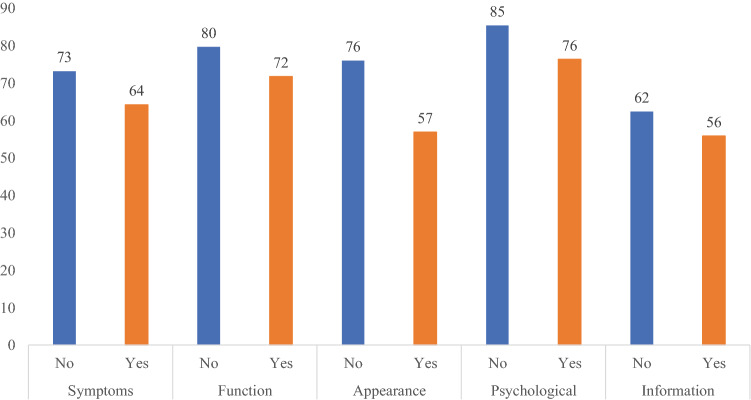

Consistent with our hypotheses, increased severity of arm swelling (Fig. 1), reporting of an arm problem caused by cancer or cancer treatments (Fig. 2), and wearing of a compression sleeve to reduce or prevent swelling in the past 12 months (Fig. 3) all were meaningfully associated with worse outcomes in all six LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module scales. Differences between scale scores by subgroups were statistically significant (p < 0.001) for all the scales in these three hypotheses. The characteristics of the subgroups for these tests of construct validity can be found in Appendix 4a–c.

Fig. 1.

Mean scores for LYMPH-Q scales based on self-reported severity of arm swelling

Fig. 2.

Mean scores for LYMPH-Q scales based on having a problem with the arm(s) as a result of breast cancer and/or its treatment

Fig. 3.

Mean scores for LYMPH-Q scales based on whether the participant wore a compression sleeve in the past 12 months

Discussion

The LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module provides clinicians and researchers with a rigorously developed PROM that can be used to measure outcomes of breast cancer-related arm lymphedema. Given the high prevalence of arm lymphedema and its significant impact on HRQOL, this new PROM represents an important addition to the literature.

The lack of an upper extremity lymphedema PROM developed with patient input has impeded advancements in the field of lymphedema research and treatment. Whereas an increasing number of studies have used HRQOL as the primary outcome in lymphedema research,7,40–42 recent literature reviews by Coriddi et al.42 and Beelen et al.8 have highlighted the frequent use of ad hoc instruments and generic PROMs to assess HRQOL. Ad hoc questionnaires are surveys, often composed for a specific study, with unknown psychometric properties. Generic PROMs are those designed for use with any patient population, which therefore do not ask about lymphedema-specific concerns. Although generic PROMs can facilitate comparison of outcomes across disease groups, such PROMs may not detect clinically important change after treatment for specific patient groups.43,44

For patients with lymphedema, no single objective measure adequately reflects the totality of a patient’s disability. Limb volume is a commonly used measure, but it can fluctuate throughout the day and can be manipulated with physiotherapy. In addition, this measurement does not account for other important concerns, such as recurrent cellulitis, physical disability, and psychological distress. Patient-reported outcomes in lymphedema used in conjunction with objective measures would provide a more complete picture of whether a therapeutic intervention has helped or not.

Due to the complex nature of lymphedema, greater fidelity in patient-reported outcome measurement is needed, which prompted the development of the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module. The LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module was developed using a modern psychometric approach. Patient input ensured that the concepts most important to patients with lymphedema were identified and used to form the scales. The use of RMT analysis ensured that the scales provide interval-level measurement and are well-suited for use in individual patient care settings. The module can be used to evaluate the impact of new medical and surgical interventions for arm lymphedema, such as lymphovenous anastomosis and vascularized lymph node transplantation.

When choosing a PROM, high content validity, largely established through qualitative input from patients who have the condition of interest, is vital to measurement of change after an intervention. An important strength of our study was the careful qualitative research performed to ensure that the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module had content validity for patients in three countries and was validated in two languages. Furthermore, evidence from the field-test study showed that the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module worked the same by language and by age in the DIF analysis. These findings are important because they mean that the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module provides a common metric with comparable scoring that can help to facilitate international research in lymphedema treatments.

Our study had several limitations. The initial qualitative sample did not include Danish participants, and the field-test sample did not include Canadians. However, for the Danish participants, we were able to ensure that the scales had content validity by including 10 women with arm lymphedema in the cognitive interviews performed to refine the scales and 10 additional women in the review of the Danish translation. Future research is needed to test the scales in a Canadian population.

To collect a large sample of data, we used an online survey, which can provide a large sample quickly at a low cost. Online surveys, however, do not reach participants with no Internet access and those who have access but are not active online. The majority of our participants were Danish and white, which limits applicability. Further validation studies could include a more diverse sample recruited from other countries.

Finally, we discovered a problem with the branching logic in the longitudinal setup within LRA REDCap for the test-retest reliability portion of the study. As a result, the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module was sent 3 weeks after treatment instead of the planned 1 week after treatment. However, we believe 3 weeks still are a valid time for assessment of test-retest reliability.45 Because our research used a cross-sectional study design, testing the responsiveness of the scales was beyond the scope of this study. Future research is needed to examine the ability of the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module scales to measure change and establish a minimal important difference.

Conclusion

The LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module was created through a rigorous development process with an emphasis on qualitative input from patients and experts. It addresses an unmet need in the literature by providing a PROM for use in upper extremity lymphedema care and outcomes research with strong content and construct validity.

Acknowledgments

Phase 1 of this study was supported by the Canadian Breast Cancer Foundation Project Grant (now integrated into Canadian Cancer Society) (Grant No. 319371. Phase 2 of this study was supported by the Canadian Cancer Society (Grant No. 706256). Manraj Kaur was supported by the Canadian Institute of Health Research Canada’s Best Graduate Scholarship Doctoral Award (2015–2019). Louise Marie Beelen was partially supported by ZonMw (Network Grant). Contributions from Memorial Sloan-Kettering were funded in part through the NIH/NCI Cancer Center Support Grant P30CA008748.

Appendix 1

Threshold maps and person-item threshold distributions for each LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity scale from the RMT analysis

Appendix 2

Scale level results for the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module

| Scale | RMT analysis | ICC (95% CI) | Floor % | Ceiling % | Missing % | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| # completed scale | # included in RMT | Scored on scale % | χ2 | DF | P value | PSI +extr | PSI -extr | α +extr | α -extr | |||||

| Appearance | 3287 | 2721 | 82.8 | 62.09 | 90 | 0.99 | 0.93 | 0.92 | 0.97 | 0.95 | 0.96 (0.94–0.98) | 2.2 | 14.3 | 0.4 |

| Psychological | 3273 | 2505 | 76.5 | 99.27 | 96 | 0.39 | 0.80 | 0.83 | 0.93 | 0.91 | 0.94 (0.90–0.96) | 0 | 22.7 | 0.8 |

| Function | 3293 | 2635 | 80.0 | 57.51 | 96 | 0.99 | 0.84 | 0.87 | 0.94 | 0.92 | 0.95 (0.92–0.97) | 0.2 | 19.0 | 0.2 |

| Symptoms | 3300 | 3157 | 95.7 | 127.17 | 135 | 0.67 | 0.88 | 0.89 | 0.93 | 0.93 | 0.92 (0.87–0.95) | 0 | 4.1 | 0.1 |

| Arm sleeve | 2314 | 2186 | 94.5 | 59.80 | 90 | 0.99 | 0.87 | 0.86 | 0.91 | 0.89 | 0.94 (0.89–0.96) | 0.5 | 4.5 | 1.1 |

| Information | 1816 | 1504 | 82.8 | 83.89 | 72 | 0.16 | 0.91 | 0.90 | 0.95 | 0.92 | 0.92 (0.85–0.95) | 4.3 | 11.8 | 1.4 |

χ2 = chi square; df = degrees of freedom; PSI + extr = Person Separation Index with extremes; PSI-extr = Person Separation Index without extremes; α+extr = Cronbach alpha with extremes; α-extr = Cronbach alpha without extremes; ICC = intraclass correlation coefficient; Floor = percent of participants scoring at the bottom of the scale; Ceiling = percent of participants scoring at the top of the scale

Appendix 3

RMT item level fit statistics and differential item function results

| Scales | Item fit statistics | Differential item function* | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Item | Location | SE | Fit residual | df | χ2 | df | Probability | Dataset | Age-group | ||

| Unadj | Adj | Unadj | Adj | ||||||||

| Symptoms | |||||||||||

| Pain touch | − 1.20 | 0.04 | − 1.29 | 2880 | 3.90 | 9 | 0.92 | No | No | No | No |

| Pain rest | − 1.05 | 0.03 | − 4.41 | 2899 | 6.29 | 9 | 0.71 | No | No | No | No |

| Temperature | − 0.75 | 0.03 | 2.17 | 2877 | 3.71 | 9 | 0.93 | No | No | No | No |

| Stiff | − 0.72 | 0.03 | − 2.03 | 2859 | 4.17 | 9 | 0.90 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Sleeping | − 0.29 | 0.03 | − 1.05 | 2893 | 2.85 | 9 | 0.97 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Aching | − 0.29 | 0.03 | − 7.90 | 2875 | 14.69 | 9 | 0.10 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Numb | − 0.27 | 0.03 | 7.08 | 2864 | 12.11 | 9 | 0.21 | No | No | No | No |

| Pressure | − 0.16 | 0.03 | − 6.20 | 2872 | 10.86 | 9 | 0.29 | No | No | No | No |

| Pain move | − 0.10 | 0.03 | − 5.44 | 2905 | 8.95 | 9 | 0.44 | No | No | No | No |

| Clumsy | 0.07 | 0.03 | 5.07 | 2882 | 6.34 | 9 | 0.71 | No | No | No | No |

| Tingling | 0.09 | 0.03 | 1.36 | 2883 | 3.17 | 9 | 0.96 | No | No | No | No |

| Tired | 0.87 | 0.03 | − 10.03 | 2884 | 18.41 | 9 | 0.03 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Weak | 1.00 | 0.03 | − 1.00 | 2893 | 1.61 | 9 | 1.00 | No | No | No | No |

| Heavy | 1.14 | 0.03 | − 6.49 | 2900 | 7.81 | 9 | 0.55 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Swelling | 1.66 | 0.03 | 8.09 | 2912 | 22.31 | 9 | 0.01 | Yes | No | Yes | No |

| Function | |||||||||||

| Clothes | − 1.07 | 0.04 | − 3.22 | 2400 | 5.70 | 8 | 0.68 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Wash hair | − 1.07 | 0.04 | − 5.81 | 2383 | 9.93 | 8 | 0.27 | No | No | Yes | No |

| Buttons | − 0.53 | 0.04 | 1.52 | 2393 | 1.89 | 8 | 0.98 | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Hold phone | − 0.47 | 0.04 | 0.42 | 2395 | 1.62 | 8 | 0.99 | No | No | Yes | No |

| Reach across | − 0.43 | 0.04 | − 0.83 | 2388 | 3.81 | 8 | 0.87 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Grip handle | − 0.37 | 0.04 | − 4.29 | 2380 | 7.32 | 8 | 0.50 | No | No | No | No |

| Hold book | − 0.04 | 0.04 | − 2.28 | 2373 | 3.22 | 8 | 0.92 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Use hands | − 0.04 | 0.04 | 0.35 | 2383 | 2.79 | 8 | 0.95 | No | No | No | No |

| Reach overhead | 0.52 | 0.03 | 5.99 | 2401 | 7.64 | 8 | 0.47 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Hold groceries | 0.96 | 0.03 | 1.58 | 2395 | 1.83 | 8 | 0.99 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Do chores | 1.04 | 0.03 | − 3.04 | 2399 | 7.45 | 8 | 0.49 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Move arm | 1.50 | 0.03 | − 3.26 | 2383 | 4.31 | 8 | 0.83 | No | No | No | No |

| Appearance | |||||||||||

| People seeing | − 0.98 | 0.04 | 1.14 | 2412 | 8.50 | 9 | 0.49 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Long-sleeved shirt | − 0.90 | 0.04 | 3.66 | 2418 | 6.68 | 9 | 0.67 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Dress to hide | − 0.64 | 0.04 | 1.94 | 2411 | 2.90 | 9 | 0.97 | No | No | No | No |

| Photos | − 0.37 | 0.04 | − 3.64 | 2399 | 5.23 | 9 | 0.81 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Noticeable | − 0.16 | 0.04 | − 5.85 | 2421 | 6.64 | 9 | 0.67 | No | No | Yes | − |

| Size | 0.33 | 0.04 | − 1.95 | 2430 | 3.92 | 9 | 0.92 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Certain clothes | 0.42 | 0.03 | − 2.42 | 2424 | 3.99 | 9 | 0.91 | No | No | No | No |

| Clothes fit | 0.49 | 0.04 | − 0.04 | 2416 | 4.50 | 9 | 0.88 | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Symmetry | 0.57 | 0.04 | − 4.85 | 2418 | 9.19 | 9 | 0.42 | No | No | No | No |

| Sleeveless shirt | 1.23 | 0.04 | − 4.24 | 2426 | 10.57 | 9 | 0.31 | No | No | No | No |

| Psychological | |||||||||||

| Desperate | − 1.38 | 0.06 | − 7.41 | 2264 | 15.81 | 8 | 0.05 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Hopeless | − 0.85 | 0.05 | − 6.13 | 2271. | 13.11 | 8 | 0.11 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Angry | − 0.52 | 0.04 | − 4.63 | 2280 | 7.70 | 8 | 0.46 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Depressed | − 0.39 | 0.04 | − 4.85 | 2275 | 8.33 | 8 | 0.40 | No | No | Yes | No |

| Stressed | − 0.16 | 0.04 | − 5.71 | 2267 | 10.94 | 8 | 0.21 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Afraid | − 0.08 | 0.04 | − 2.66 | 2271 | 3.79 | 8 | 0.88 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Anxious | − 0.03 | 0.04 | − 0.98 | 2275 | 2.67 | 8 | 0.95 | No | No | Yes | No |

| Fed-up | − 0.01 | 0.04 | − 5.17 | 2277 | 8.19 | 8 | 0.42 | No | No | No | No |

| Unattractive | 0.66 | 0.04 | 4.86 | 2270 | 8.08 | 8 | 0.43 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Worried | 0.85 | 0.04 | 1.54 | 2276 | 2.53 | 8 | 0.96 | Yes | No | No | No |

| Irritated | 0.88 | 0.04 | 4.67 | 2277 | 7.49 | 8 | 0.48 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Frustrated | 1.03 | 0.04 | − 0.18 | 2276 | 10.64 | 8 | 0.22 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Information | |||||||||||

| What it is | − 0.99 | 0.04 | 2.18 | 1325 | 12.47 | 8 | 0.13 | No | No | No | No |

| Care for it | − 0.85 | 0.04 | − 3.56 | 1318 | 10.64 | 8. | 0.22 | Yes | Yes | Yes | No |

| Avoid infections | − 0.40 | 0.04 | 3.31 | 1321 | 3.86 | 8 | 0.87 | No | No | No | No |

| How its treated | 0.07 | 0.04 | − 4.87 | 1320 | 12.96 | 8 | 0.11 | No | No | No | No |

| How to monitor | 0.08 | 0.04 | − 2.04 | 1319 | 6.21 | 8 | 0.62 | No | No | No | No |

| Possibility | 0.17 | 0.04 | 5.69 | 1322. | 12.04 | 8 | 0.15 | No | No | Yes | Yes |

| Healthcare team | 0.51 | 0.04 | 0.22 | 1318 | 3.26 | 8 | 0.92 | No | No | No | No |

| How it feels | 0.60 | 0.04 | − 3.12 | 1319 | 9.91 | 8 | 0.27 | No | No | No | No |

| Impact on life | 0.82 | 0.04 | − 2.89 | 1321 | 12.54 | 8 | 0.13 | No | No | No | No |

| Sleeve | |||||||||||

| Fits | − 0.45 | 0.03 | − 4.81 | 1935 | 8.68 | 9 | 0.47 | No | No | No | No |

| Swelling | − 0.31 | 0.03 | 2.92 | 1950 | 3.28 | 9 | 0.95 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Looks | − 0.26 | 0.03 | 1.08 | 1946. | 4.01 | 9 | 0.91 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Skin | − 0.17 | 0.03 | 4.01 | 1945 | 4.82 | 9 | 0.85 | No | No | No | No |

| Put on | − 0.14 | 0.03 | 4.35 | 1953 | 3.75 | 9 | 0.93 | No | No | Yes | No |

| Active | 0.01 | 0.03 | − 0.48 | 1942 | 4.66 | 9 | 0.86 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Long wear | 0.12 | 0.03 | − 3.91 | 1938 | 9.01 | 9 | 0.44 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

| Comfortable | 0.15 | 0.03 | − 4.66 | 1959 | 12.26 | 9 | 0.20 | No | No | No | No |

| Dressed | 0.38 | 0.03 | − 1.45 | 1941 | 4.94 | 9. | 0.84 | No | No | No | No |

| Clothes fit | 0.69 | 0.03 | 0.36 | 1945 | 4.39 | 9 | 0.88 | Yes | Yes | No | No |

SE = standard error; df = degrees of freedom; χ2 = chi-square

Appendix 4

| None N = 418 | Mild N = 1346 | Moderate N = 1070 | Severe N = 356 | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| a. Characteristics of the subgroups—self-reported severity of arm swelling (N = 3190) | ||||||||

| Country | ||||||||

| Denmark | 334 | 79.9 | 1165 | 86.6 | 990 | 92.5 | 337 | 94.7 |

| USA | 84 | 20.1 | 181 | 13.4 | 80 | 7.5 | 19 | 5.3 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||||

| ≤ 49 | 33 | 7.9 | 153 | 11.4 | 93 | 8.7 | 31 | 11.5 |

| 50–59 | 86 | 20.6 | 379 | 28.1 | 274 | 25.6 | 109 | 30.6 |

| 60–69 | 161 | 38.5 | 429 | 31.9 | 345 | 32.2 | 97 | 27.3 |

| ≥ 70 | 138 | 33.0 | 385 | 28.6 | 358 | 33.5 | 109 | 30.6 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||||

| Under/normal weight (< 25) | 180 | 43.1 | 558 | 41.5 | 377 | 35.2 | 98 | 27.5 |

| Overweight (25–29) | 143 | 34.2 | 461 | 34.2 | 378 | 35.3 | 115 | 32.3 |

| Obese (≥30) | 94 | 22.5 | 325 | 24.1 | 310 | 29.0 | 140 | 39.3 |

| Missing | 1 | 0.2 | 2 | 0.2 | 5 | 0.5 | 3 | 0.9 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||||

| Caucasian | 370 | 88.5 | 1195 | 88.8 | 914 | 85.4 | 303 | 85.1 |

| Other | 48 | 11.5 | 151 | 11.2 | 156 | 14.6 | 53 | 14.9 |

| Time since lymphedema diagnosis | ||||||||

| ≤ 4 | 123 | 29.4 | 475 | 35.3 | 310 | 29.0 | 82 | 23.0 |

| 5–9 | 142 | 34.0 | 489 | 36.3 | 402 | 37.5 | 135 | 38.0 |

| ≥ 10 | 153 | 36.6 | 382 | 28.4 | 358 | 33.5 | 139 | 39.0 |

| Lymphedema laterality | ||||||||

| Unilateral | 413 | 98.8 | 1322 | 98.2 | 1044 | 97.6 | 345 | 96.9 |

| Bilateral | 5 | 1.2 | 24 | 1.8 | 26 | 2.4 | 11 | 3.1 |

| None N = 335 | Minor N = 2108 | Major N = 779 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | N | % | |

| b. Characteristics of the subgroups—based on having a problem with the arm(s) as a result of breast cancer and/or its treatment (N = 3222) | ||||||

| Country | ||||||

| Denmark | 302 | 90.1 | 1865 | 88.5 | 691 | 88.7 |

| USA | 33 | 9.9 | 243 | 11.5 | 88 | 11.3 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||||

| ≤ 49 | 21 | 6.3 | 211 | 10.0 | 90 | 11.6 |

| 50–59 | 57 | 17.0 | 564 | 26.8 | 233 | 29.9 |

| 60–69 | 105 | 31.3 | 695 | 33.0 | 237 | 30.4 |

| ≥ 70 | 152 | 45.4 | 638 | 30.2 | 219 | 28.1 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||||

| Under/normal weight (< 25) | 152 | 45.4 | 834 | 39.6 | 240 | 30.8 |

| Overweight (25–29) | 114 | 34.0 | 734 | 34.8 | 259 | 33.3 |

| Obese (≥30) | 67 | 20.0 | 534 | 25.3 | 276 | 35.4 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.6 | 6 | 0.3 | 4 | 0.5 |

| Ethnicity | ||||||

| Caucasian | 292 | 87.2 | 1844 | 87.5 | 670 | 86.0 |

| Other | 43 | 12.8 | 264 | 12.5 | 109 | 14.0 |

| Time since lymphedema diagnosis | ||||||

| ≤ 4 | 94 | 28.1 | 683 | 32.4 | 221 | 28.4 |

| 5-9 | 132 | 39.4 | 774 | 36.7 | 277 | 35.6 |

| ≥ 10 | 109 | 32.5 | 651 | 30.9 | 281 | 36.0 |

| Lymphedema laterality | ||||||

| Unilateral | 330 | 98.5 | 2080 | 98.7 | 746 | 95.8 |

| Bilateral | 5 | 1.5 | 28 | 1.3 | 33 | 4.2 |

| No sleeve N = 940 | Sleeve N = 2282 | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | % | N | % | |

| c. Characteristics of the subgroups—based on whether participant wore a compression sleeve in the past 12 months (N = 3222) | ||||

| Country | ||||

| Denmark | 807 | 85.9 | 2051 | 89.9 |

| USA | 133 | 14.1 | 231 | 10.1 |

| Age groups (years) | ||||

| ≤ 49 | 83 | 8.8 | 239 | 10.5 |

| 50–59 | 226 | 24.0 | 628 | 27.5 |

| 60–69 | 319 | 34.0 | 718 | 31.5 |

| ≥ 70 | 312 | 33.2 | 697 | 30.5 |

| BMI (kg/m2) | ||||

| Under/normal weight (< 25) | 350 | 37.2 | 876 | 38.4 |

| Overweight (25–29) | 328 | 34.9 | 779 | 34.1 |

| Obese (≥ 30) | 260 | 27.7 | 617 | 27.1 |

| Missing | 2 | 0.2 | 10 | 0.4 |

| Ethnicity | ||||

| Caucasian | 811 | 86.3 | 1995 | 87.4 |

| Other | 129 | 13.7 | 287 | 12.6 |

| Time since lymphedema diagnosis | ||||

| ≤ 4 | 217 | 23.1 | 781 | 34.2 |

| 5–9 | 350 | 37.2 | 833 | 36.5 |

| ≥ 10 | 373 | 39.7 | 668 | 29.3 |

| Lymphedema laterality | ||||

| Unilateral | 913 | 97.1 | 2243 | 98.3 |

| Bilateral | 27 | 2.9 | 39 | 1.7 |

Disclosures

The LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module is owned by Memorial Sloan-Kettering Cancer Center, McMaster University, and Mass General Brigham, and Pusic and Klassen are co-developers. The remaining authors have no conflicts of interest.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Contributor Information

Anne F. Klassen, Email: aklass@mcmaster.ca.

Elena Tsangaris, Email: etsangaris@bwh.harvard.edu.

Manraj N. Kaur, Email: kaurmn@mcmaster.ca.

Lotte Poulsen, Email: lotte.poulsen2@rsyd.dk.

Louise M. Beelen, Email: lbeelen@bwh.harvard.edu.

Amalie Lind Jacobsen, Email: Amalie.Lind.Jacobsen@rsyd.dk.

Mads Gustaf Jørgensen, Email: Mads.Gustaf.Jorgensen@rsyd.dk.

Jens Ahm Sørensen, Email: jens.sorensen@rsyd.dk.

Dalibor Vasilic, Email: d.vasilic@erasmusmc.nl.

Joseph Dayan, Email: dayanj@mskcc.org.

Babak Mehrara, Email: mehrarab@mskcc.org.

Andrea L. Pusic, Email: apusic@bwh.harvard.edu.

References

- 1.DiSipio T, Rye S, Newman B, et al. Incidence of unilateral arm lymphoedema after breast cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Oncol. 2013;14:500–515. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(13)70076-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McDuff SGR, Mina AI, Brunelle CL, et al. Timing of lymphedema after treatment for breast cancer: when are patients most at risk? Int J Radiat Oncol Biol Phys. 2019;103:62–70. doi: 10.1016/j.ijrobp.2018.08.036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pereira ACPR, Koifman RJ, Bergmann A. Incidence and risk factors of lymphedema after breast cancer treatment: 10 years of follow-up. Breast. 2017;36:67–73. doi: 10.1016/j.breast.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Taghian NR, Miller CL, Jammallo LS, et al. Lymphedema following breast cancer treatment and impact on quality of life: a review. Crit Rev Oncol Hematol. 2014;92:227–234. doi: 10.1016/j.critrevonc.2014.06.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Pusic AL, Cemal Y, Albornoz C, et al. Quality of life among breast cancer patients with lymphedema: a systematic review of patient-reported outcome instruments and outcomes. J Cancer Surviv. 2013;7:83–92. doi: 10.1007/s11764-012-0247-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Wiser I, Mehrara BJ, Coriddi M, et al. Preoperative assessment of upper extremity secondary lymphedema. Cancers Basel. 2020;12:135. doi: 10.3390/cancers12010135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hormes JM, Bryan C, Lytle LA, et al. Impact of lymphedema and arm symptoms on quality of life in breast cancer survivors. Lymphology. 2010;43:1–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Beelen LM, van Dishoeck AM, Tsangaris E, et al. Patient-reported outcome measures in lymphedema: a systematic review and COSMIN analysis. Ann Surg Oncol. 2021;28(3):1656–1668. doi: 10.1245/s10434-020-09346-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lasch KE, Marquis P, Vigneux M, et al. PRO development: rigorous qualitative research as the crucial foundation. Qual Life Res. 2010;19:1087–1096. doi: 10.1007/s11136-010-9677-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.U.S. Department of Health and Human Services. Guidance for industry patient-reported outcome measures: use in medical product development to support labeling claims. Retrieved 31 August 2020 at https://www.fda.gov/media/77832/download. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Prinsen CA, Mokkink Bouter, et al. COSMIN guideline for systematic reviews of patient-reported outcome measures. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1147–1157. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1798-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Pusic AL, Klassen AF, Scott AM, et al. Development of a new patient-reported outcome measure for breast surgery: the BREAST-Q. Plast Reconstr Surg. 2009;124:345–353. doi: 10.1097/PRS.0b013e3181aee807. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Aaronson N, Alonso J, Burnam A, et al. Assessing health status and quality-of-life instruments: attributes and review criteria. Qual Life Res. 2002;11:193–205. doi: 10.1023/A:1015291021312. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO good research practices task force report: part 1–eliciting concepts for a new PRO instrument. Value Health. 2011;14:967–977. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Patrick DL, Burke LB, Gwaltney CJ, et al. Content validity–establishing and reporting the evidence in newly developed patient-reported outcomes (PRO) instruments for medical product evaluation: ISPOR PRO Good Research Practices Task Force report: part 2–assessing respondent understanding. Value Health. 2011;14:978–988. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2011.06.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for assessing the content validity of proms: user manual. Amsterdam: VU University Medical Center; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Terwee CB, Prinsen CAC, Chiarotto A, et al. COSMIN methodology for evaluating the content validity of patient-reported outcome measures: a Delphi study. Qual Life Res. 2018;27:1159–1170. doi: 10.1007/s11136-018-1829-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thorne S. Interpretive description: developing qualitative inquiry. Walnut Creek: Left Cost Press Inc.; 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rasch G. Probabilistic models for some intelligence and attainment tests: studies in mathematical psychology. Copenhagen: Danmarks Paedagogiske Institut; 1960. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Andrich D. A rating formulation for ordered response categories. Psychometrika. 1978;43:561–573. doi: 10.1007/BF02293814. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Love S. Love Research Army. Retrieved 31 August 2020 at https://www.armyofwomen.org/.

- 22.Willis GB. Cognitive interviewing in practice: think-aloud, verbal probing, and other techniques: cognitive interviewing. Thousand Oaks: Sage Publications; 2005. pp. 42–65. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Collins D. Pretesting survey instruments: an overview of cognitive methods. Qual Life Res. 2003;12:229–238. doi: 10.1023/A:1023254226592. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Van Someren M, Barnard Y, Sandberg J. The think-aloud method: a practical approach to modelling cognitive. London: AcademicPress; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Madsen CB, Jørgensen MG, Klassen A, et al. Danish translation and linguistic validition of the LYMPH-Q Upper Extremity Module. Submitted.

- 26.Wild D, Grove A, Martin M, et al. Principles of good practice for the translation and cultural adaptation process for patient-reported outcomes (PRO) measures: report of the ISPOR task force for translation and cultural adaptation. Value Health. 2005;8:94–104. doi: 10.1111/j.1524-4733.2005.04054.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.World Health Organization. Process of Translation and Adaption of Instruments. Retrieved 31 August 2020 at http://www.who.int/substance_abuse/research_tools/translation/en/.

- 28.Harris PA, Taylor R, Thielke R, et al. Research electronic data capture (REDCap): a metadata-driven methodology and workflow process for providing translational research informatics support. J Biomed Inform. 2009;42:377–381. doi: 10.1016/j.jbi.2008.08.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.University of Southern Denmark. Research. Retrieved 31 August 2020 at https://www.sdu.dk/en/om_sdu/institutter_centre/klinisk_institut/forskning/forskningsenheder/open.aspx.

- 30.Hobart J, Cano S. Improving the evaluation of therapeutic interventions in multiple sclerosis: the role of new psychometric methods. Health Technol Assess. 2009;13:iii, ix–x, 1–177. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 31.Wright BD, Masters GN. Rating scale analysis. Chicago: MESA Press; 1982. [Google Scholar]

- 32.Andrich D. Rasch Models for Measurement: Sage University Papers Series Quantative Applications in the Social Sciences, vol 07-068. Thousand Oaks : Sage; 1988.

- 33.Andrich D. An elaboration of Guttman scaling with Rasch models for measurement. Soc Method. 1985;15:33–80. doi: 10.2307/270846. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Christensen KB, Makransky G, Horton M. Critical values for Yen’s Q3: identification of local dependence in the Rasch model using residual correlations. Appl Psychol Meas. 2017;41:178–194. doi: 10.1177/0146621616677520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Marais I. Local dependence. In: Christensen KB, Kreiner S, Mesbah M, editors. Rasch models in health. London: Wiley-ISTE Ltd.; 2013. pp. 111–130. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Cronbach LJ. Coefficient alpha and the internal structure of tests. Psychometrika. 1951;16:297–334. doi: 10.1007/BF02310555. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nunnally JC. Psychometric theory. 3. New York: McGraw-Hill; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Terwee CB, Bot SDM, deBoer MR, et al. Quality criteria were proposed for measurement properties of health status questionnaires. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007;60:34–42. doi: 10.1016/j.jclinepi.2006.03.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Kim H-Y. Statistical notes for clinical researchers: assessing normal distribution (2) using skewness and kurtosis. Restor Dent Endod. 2013;38:52–54. doi: 10.5395/rde.2013.38.1.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Cornelissen AJ, Kool M, Penha TRL, et al. Lymphatico-venous anastomosis as treatment for breast cancer-related lymphedema: a prospective study on quality of life. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2017;163:281–286. doi: 10.1007/s10549-017-4180-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Cheng M-H, Chang DW, Patel KM. Principles and practice of lymphedema surgery. New York, NY: Elsevier Health Sciences; 2015. [Google Scholar]

- 42.Coriddi M, Dayan J, Sobti N, et al. Systematic review of patient-reported outcomes following surgical treatment of lymphedema. Cancers Basel. 2020;12:565. doi: 10.3390/cancers12030565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patrick DL, Deyo RA. Generic and disease-specific measures in assessing health status and quality of life. Med Care. 1989;27(3l):S217–S232. doi: 10.1097/00005650-198903001-00018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Wiebe S, Guyatt G, Weaver B, et al. Comparative responsiveness of generic and specific quality-of-life instruments. J Clin Epidemiol. 2003;56:52–60. doi: 10.1016/S0895-4356(02)00537-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Streiner DL, Norman G. Health measurement scales: a practical guide to their development and use. 4. New York: Oxford University Press; 2008. [Google Scholar]