Abstract

The anatomy of the primate forearm is frequently investigated in terms of locomotor mode, substrate use, and manual dexterity. Such studies typically rely upon broad, interspecific samples for which one or two representative taxa are used to characterize the anatomy of their genus or family. To interpret variation between distantly related taxa, however, it is necessary to contextualize these differences by quantifying variation at lower hierarchical levels, that is, more fine‐grained representation within specific genera or families. In this study, we present a focused evaluation of the variation in muscle organization, integration, and architecture within two speciose primate families: the Callitrichidae and Lemuridae. We demonstrate that, within each lineage, several muscle functional groups exhibit substantial variation in muscle organization. Most notably, the digital extensors appear highly variable (particularly among callitrichids), with many unique configurations represented. In terms of architectural variables, both families are more conservative, with the exception of the genus Callimico—for which an increase is observed in forearm muscle mass and strength. We suggest this reflects the increased use of vertical climbing and trunk‐to‐trunk leaping within this genus relative to the more typically fine‐branch substrate use of the other callitrichids. Overall, these data emphasize the underappreciated variation in forearm myology and suggest that overly generalized typification of a taxon's anatomy may conceal significant intraspecific and intrageneric variation therein. Thus, considerations of adaptation within the forearm musculature should endeavor to consider the full range of anatomical variation when making comparisons between multiple taxa within an evolutionary context.

Keywords: dexterity, fascicle length, muscle, PCSA, primate

Photographs taking during the dissection of a specimen of Varecia rubra. (a) and (b) show superficial images of the anterior (flexor) and posterior (extensor) compartments; (c) and (d) show deeper images of the same compartments

![]()

1. INTRODUCTION

The functional repertoire of the primate forearm encompasses a broad array of tasks, from locomotion (Cartmill, 1972; Lemelin & Grafton, 1998; Reghem et al., 2012; Schmitt, 1998; Schmitt & Lemelin, 2002; Sussman & Raven, 1978) to object manipulation (Reghem et al., 2011; Toussaint et al., 2013) and grooming (Hopkins et al., 2007; Mitchell & Tokunaga, 1976). Across the order, functional differences in forearm and hand use have been associated with significant anatomical variation in the myology of the forelimb (e.g., Aversi‐Ferreira et al., 2010; Diogo et al., 2012; Gyambibi & Lemelin, 2013; Kikuchi, 2010; Leischner et al., 2018; Lemelin & Diogo, 2016; Michilsens et al., 2009; Myatt et al., 2012; Van Leeuwen et al., 2018). Such studies have demonstrated, for example, an increase in wrist flexor strength among gibbons and chimpanzees (Michilsens et al., 2009; Thorpe et al., 1999), as well as generalized trends toward greater muscle excursion potential within arboreal taxa (Leischner et al., 2018).

Due to the relatively rare nature of primate cadaveric material, such analyses have been largely restricted to small samples predominantly composed of the most attainable taxa, resulting in broad interspecific comparisons across the order with little fine‐grained taxonomic coverage. To interpret directional trends in variation across these large phylogenetic distances, however, it is imperative to contextualize these data alongside an understanding of variation existing at lower hierarchical levels (e.g., within individual families, genera, or even species). Indeed, without an understanding of such variation, anatomists can neither verify that inter‐specimen differences are generally representative of differences at a population level nor investigate anatomical fluidity within a taxon or genus—resulting instead in generalized descriptions that may lead to misinterpretation of adaptive evolution within a lineage that may be represented by only one or two isolated specimens. Such absolute notions of a taxon's anatomy may be particularly misleading in the forearm where anatomical variants in muscle organization have been suggested to be extremely common (Boettcher et al., 2019; Boettcher et al., 2020a; Diogo et al., 2012; Diogo & Wood, 2012; Lemelin & Diogo, 2016).

1.1. Myology of the primate forearm

The muscles of the forearm can be broadly divided on the basis of function into five distinct functional groups: digital flexors, digital extensors, wrist flexors, wrist extensors, and forearm pronators/supinators. (One additional muscle—the brachioradialis—is primarily in the forearm but functions with the brachial muscles as an elbow flexor.) The number of constituent muscles within each functional group may vary; while some are relatively conservative in their organization, others may present many distinct forms (e.g., the digital extensors, where a number of digit‐specific accessory extensors may complement the common digital extensor). An increase in the number of dedicated muscles may be important in enhancing dexterity by facilitating isolated control of individual digits during object manipulation. Additionally, the relative volumes of each functional group (and of individual muscles therein) may provide an insight into the relative importance of each generalized action to the behavioral repertoire of an individual or species.

Correlates of muscle function can also be observed in the organization of muscle fiber bundles, or fascicles, within individual muscles. Longer fascicles contain a greater number of serially arranged sarcomeres, facilitating an increase in both excursion potential and contractile velocity (Bodine et al., 1982; Gans & Bock, 1965; Gokhin et al., 2009). Meanwhile, as total fiber count is proportional to force production (measured anatomically as physiological cross‐sectional area [PCSA]; Anapol & Barry, 1996; Lieber, 1986; Schumacher, 1961), shorter fascicles permit a greater total number of muscle fascicles to be accommodated within a given volume of muscle. Thus, from an organizational perspective, there exists a functional trade‐off between force and excursion: for a given muscle volume, muscles with fewer, longer fascicles can produce greater stretch and contractile speed, while muscles with more numerous though shorter fascicles can produce greater contractile force (Gans & Bock, 1965; Gans & Gaunt, 1991; Lieber, 1986; Lieber & Fridén, 2000; Lieber & Ward, 2011).

1.2. Myological variation in the primate forearm

Over the last decade, several studies have sought to examine ecological or behavioral correlates of architectural and organizational variation in the primate forearm. Relative to terrestrial counterparts, Leischner et al., (2018) report that arboreal taxa possess significantly greater fascicle lengths in several functional groups of the forearm, a trend interpreted to reflect increased mobility during locomotion. Additionally, brachiating gibbons have been shown to possess elevated PCSA in muscles associated with the flexion of the elbow and wrist (Michilsens et al., 2009). A similar increase in wrist flexor strength is also reported in chimpanzees relative to humans (Thorpe et al., 1999), further suggesting an important role of wrist flexor strength in arboreal specialists. Within prosimians, however, the forearm musculature appears relatively conservative, scaling closely with body mass and showing no strong relationships with locomotor mode or substrate types (Gyambibi & Lemelin, 2013). Similarly, an analysis of fascicle lengths within the digital flexors of a broad primate sample showed no correlation with locomotor speed (Boettcher et al., 2019), while certain taxa (e.g., Perodicticus potto) that were expected to possess a relatively increased digital flexor PCSA appeared distinctly unremarkable, plotting instead as relatively average among primates.

Several attempts have also been made to aggregate trends in muscle organization and integration across the primate order by combining historical records of forearm gross dissections with novel dissections of supplementary taxa (e.g., Diogo et al., 2012; Diogo & Wood, 2011; Diogo & Wood, 2012; Lemelin & Diogo, 2016). Though restricted to qualitative observations, a number of valuable observations are reported, including the loss of an ulnar attachment site of the extensor carpi ulnaris (ECU) in several old‐world and new‐world monkeys (including Papio, Macaca, and Saimiri) and the loss of a tendinous insertion of the flexor digitorum superficialis (FDS) to Digit II in Loris and Perodicticus (Lemelin & Diogo, 2016). However, due to a lack of consistency between historical accounts (many of which date to the early 20th century), critical data regarding the fine anatomy of these muscles are unavailable. Moreover, as more recent studies have dissected additional representatives of certain genera or taxa, some of these earlier findings have been challenged. For instance, more recent accounts of the forearm muscles of Perodicticus (Boettcher et al., 2020a) confirm a tendinous insertion of the FDS to Digit II, as seen in most primates, despite the vestigiality of this digit in this taxon. In addition to highlighting the extent to which anatomical trends in this region remain poorly understood, such examples further underline the importance of more rigorous sampling within a genus/family to better identify the extent of variation therein, an understanding that has significant implications for interpreting evolutionary adaptations within a lineage.

1.3. Aims of the study

Within this study, we present systematic data on muscle organization, integration, and architectural variation across the forearm functional groups of two speciose primate families: the Callitrichidae and the Lemuridae. These families are each composed of a high number of both genera and species that span relatively conservative body mass ranges, rendering them ideal for studies of intrafamilial variation. The New World Callitrichidae, consisting of tamarins and marmosets, are generally characterized as diminutive (100–500 g), highly arboreal species that practice “squirrel‐like” (Garber, 1980) vertical climbing supplemented by arboreal quadrupedalism. The Malagasy Lemuridae (0.9–4.0 kg; Mittermeier et al., 2013), meanwhile, can be collectively characterized as arboreal quadrupeds that engage in a broad array of generalized locomotor behaviors, including leaping, vertical climbing, and suspension (Ashton & Oxnard, 1964; Hunt et al., 1996).

The forearm myology of these families is generally understood to be conservative among primates, being relatively unspecialized in its organization with few accessory tendons associated with fine motor manipulation of individual digits (Diogo et al., 2012; Diogo & Wood, 2011; Diogo & Wood, 2012; Lemelin & Diogo, 2016), though an expansion of the extensor indicis (EI) to Digits II–IV has been previously noted in Saguinus and Callithrix among the Callitrichidae (Lemelin & Diogo, 2016). Variation in forearm muscle architectural properties (e.g., muscle masses, fascicle lengths, and PCSAs) within each family, however, is poorly documented owing to a limited number of quantitative studies focused upon each family. We address this knowledge gap by presenting these data alongside categorical descriptions of muscle organization and integration for all specimens analyzed herein.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Data collection

A sample of 46 captive adult primate specimens, composed of 30 callitrichids and 16 lemurids, were included within this study (Table 1). These specimens represented 12 species in five genera of callitrichid, and seven species in four genera of lemurid. The majority of specimens were obtained from the University of Valladolid School of Medicine, though a subset of lemurids were additionally sourced from the Duke Lemur Center, the Lemur Conservation Foundation, and the North Carolina Zoo. In all cases, specimens were adults acquired frozen and unfixed. No specimens were euthanized for the purposes of this study, and none exhibited signs of tissue degradation. All necessary tissue usage and safety approvals were acquired via North Carolina State University and Universidad de Valladolid prior to the onset of this study.

TABLE 1.

Dissection specimens included in analyses

| IDa | Family | Species | Sex | BM (g)c |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 8061 | Callitrichidae | Callimico goeldii | Male | 366 |

| 8023 | Callitrichidae | Callimico goeldii | Male | 366 |

| MF2 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix aurita | Female | 423.3* |

| 8044 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix geoffroyi | Male | 290 |

| CJF1b | Callitrichidae | Callithrix jacchus | Female | 183.2* |

| CJM1b | Callitrichidae | Callithrix jacchus | Male | 220.9* |

| CJM2b | Callitrichidae | Callithrix jacchus | Male | 365* |

| 8015 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix jacchus | Female | 322 |

| 8016 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix jacchus | Female | 322 |

| 8030 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix jacchus | Male | 317 |

| 7999 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix pygmaea | Male | 112 |

| 8041 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix pygmaea | Male | 112 |

| 8042 | Callitrichidae | Callithrix pygmaea | Male | 116* |

| 8007 | Callitrichidae | Mico argentatus | Male | 349 |

| 8008 | Callitrichidae | Mico argentatus | Male | 349 |

| 8009 | Callitrichidae | Mico argentatus | Male | 349 |

| 8033 | Callitrichidae | Mico argentatus | Female | 406 |

| 8035 | Callitrichidae | Mico argentatus | Female | 406 |

| 8038 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus bicolor | Male | 540 |

| 8034 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus bicolor | Male | 540 |

| 8036 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus bicolor | Female | 540 |

| 8019 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus imperator | Male | 475 |

| 8018 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus imperator | Female | 475 |

| 8013 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus labiatus | Male | 455 |

| 8012 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus labiatus | Female | 455 |

| 8001 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus midas | Female | 440 |

| So2b | Callitrichidae | Saguinus oedipus | Male | 418 |

| 8002 | Callitrichidae | Saguinus oedipus | Male | 418 |

| 8010 | Callitrichidae | Leontopithecus rosalia | Male | 620 |

| 8040 | Callitrichidae | Leontopithecus rosalia | Male | 620 |

| LCFRLOb | Lemuridae | Eulemur coronatus | Female | 1300 |

| UN1b | Lemuridae | Eulemur fulvus | Male | 2210 |

| 8049 | Lemuridae | Eulemur fulvus | Male | 1500 |

| 8059 | Lemuridae | Eulemur fulvus | Male | 1500 |

| 980577b | Lemuridae | Eulemur mongoz | Male | 1451.5* |

| DLC1371b | Lemuridae | Hapalemur griseus | Male | 954 |

| 8051 | Lemuridae | Lemur catta | Male | 2200 |

| 8056 | Lemuridae | Lemur catta | Female | 2200 |

| 8055 | Lemuridae | Lemur catta | Female | 2200 |

| 6761Fb | Lemuridae | Lemur catta | Female | 2200 |

| LCFBPb | Lemuridae | Varecia rubra | Female | 3595 |

| 8026 | Lemuridae | Varecia rubra | Female | 3600 |

| 8053 | Lemuridae | Varecia rubra | Female | 3600 |

| NCZWZYb | Lemuridae | Varecia rubra | Female | 3600 |

| 7998 | Lemuridae | Varecia variegata | Female | 3520 |

| 8060 | Lemuridae | Varecia variegata | Male | 3630 |

aOsteological remains of all specimens are curated at the Universidad de Valladolid, Museo Anatomico except “b” from North Carolina State University. cAsterisk denotes specimen‐specific body weights; for all others, sex‐specific body masses were derived from Mittermeier et al., (2013). If sex was unknown, body mass was approximated using the average of provided male and female masses reported by Mittermeier et al., (2013).

Myological data were collected following a standardized sharp dissection protocol after Herrel et al., (2008). After removing the skin and any overlying tissues, notations of integration between any adjacent muscles and the distribution of each muscle's tendons were recorded, and then each forearm muscle was individually excised and weighed to the nearest 0.001 g. At successive stages of dissection, photographs of the exposed muscles were taken using a Canon EOS 5Ds camera in layers from most superficial to deepest (Figure 1). Individual muscles were then placed in 35% nitric acid such that the connective tissues between fascicles could be chemically digested, following protocols outlined in Herrel et al., (2008). Muscles remained in the nitric acid solution for 15–24 h depending on their size and the amount of connective tissue—larger and more tendinous muscles required longer to break down. Once muscle fascicles became separable, muscles were removed from acid and placed in an aqueous 50% glycerol solution to neutralize residual acid and prevent overdigestion. Following Boettcher et al., (2020b) and Leonard et al., (2020), muscle fascicles were then separated manually with forceps into a representative sample of at least 40 fascicles to be photographed alongside a scale bar for subsequent digital data collection. The photographs of the fascicles were measured using the ImageJ 1.52a software package to record the average lengths of individual fascicles for each muscle.

FIGURE 1.

Photographs taking during the dissection of a specimen of Varecia rubra. (a) and (b) show superficial images of the anterior (flexor) and posterior (extensor) compartments; (c) and (d) show deeper images of the same compartments. Abbreviations as follows: PT, pronator teres; FCR, flexor carpi radialis; PL, palmaris longus; FCU, flexor carpi ulnaris; FDS, flexor digitorum superficialis; FDP, flexor digitorum profundus; PQ, pronator quadratus; ED, extensor digitorum; ECRB, extensor carpi radialis brevis; ECRL, extensor carpi radialis longus; BR, brachioradialis; EDM, extensor digiti minimi; ECU, extensor carpi ulnaris; APL, abductor pollicis longus; EPL, extensor pollicis longus; ED III, extensor digitorum III; EI, extensor indicis; Sup, supinator. Colors of functional groups as follows: yellow = digital flexors, green = wrist flexors, red = digital extensors, blue = wrist extensors, pink = pronators/supinators

2.2. Data analysis

Following Schumacher (1961), muscle mass and fascicle length data were combined to calculate PCSA using the formula

where q is equivalent to PCSA, m is muscle mass in grams, l represents fascicle length, and p represents muscle density. A constant of 1.056 g/cm3 was applied to represent muscle density, following Murphy and Beardsley (1974). As outlined above, individual muscles were grouped into one of five distinct functional groups (digital flexors, digital extensors, wrist flexors, wrist extensors, and forearm pronators/supinators). Muscle mass and PCSA were calculated for each functional group by summing data for all constituent muscles, while average fascicle length for each functional group was calculated as the weighted average of fascicle lengths from individual muscles therein using the formula

following Hartstone‐Rose et al., (2012) and Leischner et al., (2018) in which FL and m represent fascicle lengths and muscle masses, respectively, of individual muscles within a functional group. These data are presented in Table S1.

For subsequent analyses, data were first linearized (i.e., areas and volumes were taken to the square and cubic root respectively, such that isometry for all slopes = 1) and subsequently log‐transformed. To assess scaling relationships, reduced major axis (RMA) regressions were conducted between each architectural variable (muscle mass, fascicle length, and PCSA) and body mass. From each RMA regression, the residuals of each variable against body mass were also analyzed to assess size‐adjusted architectural variables between genera. Relationships between genera were statistically evaluated using two‐tailed Tukey–Kramer HSD pairwise tests.

3. RESULTS

3.1. Categorical analysis

Relative functional group masses remained highly conservative within each family, with only one genus (Hapalemur, which presented unusually large wrist flexors and comparatively small wrist extensors) deviating from an otherwise highly standardized trend (Table 2). However, the organization of muscles within each functional group showed several points of variation (Figure 2), particularly within Callitrichidae. Among the digital flexors, 83% of callitrichid specimens exhibited fusion between the FDS and flexor digitorum profundus (FDP), resulting in a fused muscle body characterized by integration along most or all of their lengths but two distinct tendons, while 17% exhibited distinct FDS and FDP muscle bellies. Additionally, notable variation was observed within the digital extensors. Eighty percent of specimens presented a standard configuration of the extensor digitorum profundus (EDP; sensu Diogo & Wood, 2012) attaching to Digits I and II, while 10% presented differentiated extensor pollicis longus (EPL) and EI muscles associated only with Rays I and II, respectively, 7% presented a modified EDP spanning from Digits I to III, and 3% presented an EI associated with Digits II and III alongside a differentiated EPL. The presence of a dedicated ED III accessory extensor muscle was noted in 80% of specimens, while 14% presented a derivative EDIII + IV associated with both digits, and 6% presented no central accessory extensor muscle. One final variant observed within the digital extensors was a single specimen of Callithrix jacchus for which the extensor digiti minimi (EDM) served Digit V alone (as is the state in humans), rather than sharing tendons between Digits IV and V as it does in most primates (Diogo & Wood, 2012).

TABLE 2.

Functional group muscle weights as a proportion of total forearm muscle mass for each genus of callitrichid and lemurid and the average for each family

| Group | WF | WE | DF | DE | PS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Callithrix | 18.71% (3.02%) | 7.57% (2.04%) | 18.14% (3.89%) | 43.07% (5.94%) | 12.51% (2.97%) |

| Callimico | 18.06% (0.77%) | 8.39% (0.18%) | 18.73% (0.25%) | 44.20% (0.87%) | 10.62% (0.04%) |

| Leontopithecus | 17.81% (1.48%) | 7.15% (0.25%) | 19.51% (0.35%) | 44.76% (0.68%) | 10.78% (0.70%) |

| Mico | 19.77% (1.36%) | 7.48% (1.19%) | 17.75% (1.59%) | 45.51% (3.12%) | 9.49% (0.68%) |

| Saguinus | 19.67% (2.94%) | 6.74% (1.09%) | 18.26% (2.53%) | 44.78% (4.59%) | 10.55% (1.22%) |

| Callitrichid average | 18.80% (0.89%) | 7.46% (0.61%) | 18.48% (0.67%) | 44.46% (0.91%) | 10.79% (1.09%) |

| Lemur | 13.19% (1.22%) | 7.73% (1.24%) | 21.45% (1.95%) | 47.24% (0.89%) | 10.39% (1.31%) |

| Eulemur | 15.49% (1.12%) | 7.78% (0.67%) | 18.89% (1.40%) | 47.23% (0.58%) | 10.61% (0.82%) |

| Hapalemur | 27.08% (N/A) | 2.47% (N/A) | 22.50% (N/A) | 38.70% (N/A) | 9.26% (N/A) |

| Varecia | 15.25% (0.91%) | 7.68% (1.00%) | 18.41% (1.81%) | 47.09% (1.71%) | 11.57% (1.55%) |

| Lemurid average | 17.75% (6.30%) | 6.41% (2.63%) | 20.31% (1.98%) | 45.06% (4.24%) | 10.46% (0.95%) |

Standard deviations in parentheses below.

Abbreviations: DE, digital extensors; DF, digital flexors; PS, pronators/supinators; WE, wrist extensors; WF, wrist flexors.

FIGURE 2.

Schematic illustration of digital extensor variations observed within callitrichids and lemurids. Percentages refer to prevalence within callitrichids, followed by lemurids. In all cases, digit numbers in parentheses refer to the digits receiving a tendon from the named muscle body. Muscles present in multiple parts (e.g., [a] and [b] or [a–c]) are organized by frequency of character state. Abbreviations as follows: extensor indicis (Ext. Ind.), extensor digitorum (ED), extensor digiti minimi (EDM), extensor pollicis longus (EPL)

Within Lemuridae, notably less variation in muscle organization was observed. Sixty‐nine percent of lemurid specimens demonstrated fusion between the FDS and FDP, while 31% exhibited distinct FDS and FDP muscle bellies. Further, 63% of lemurids demonstrated a dedicated EDIII, with a further 25% possessing a modified EDIII + IV muscle and one specimen possessing an expanded EDIII–V modification of this structure (in addition to a distinct EDM muscle, which was consistent across all lemurids). Additionally, unlike the Callitrichidae, few lemurids (12.5%) presented an EDP; rather, the EI and EPL remained distinct muscle bodies with no interdigitation of fascicles.

3.2. Architectural analysis

Summary statistics of all scaling relationships are presented in Table 3, while graphical representations of slopes within each family are presented in Figure 3. Across callitrichids, muscle mass scaled isometrically with body mass in all functional groups. This relationship approached positive allometry in all functional groups barring the pronators/supinators, which were more strongly isometric. However, PCSA scaled with positive allometry in all five functional groups. Finally, fascicle lengths yielded no consistent patterns relative to body mass (r 2 = −0.04–0.19) and indeed were sufficiently variable as to prohibit meaningful interpretation of their scaling relationship. Rather, trends in fascicle length appear relatively independent of body size within these taxa. Within the Lemuridae, muscle mass scaled isometrically with body mass across four functional groups and with slight positive allometry within the fifth (digital extensors). PCSA scaled isometrically in all functional groups, while fascicle lengths presented the same trend as muscle mass (scaling isometrically in all functional groups barring the digital extensors, which scaled with positive allometry). Fascicle lengths were universally more strongly associated with body mass than in callitrichids (r 2 = 0.60–0.64).

TABLE 3.

Summary scaling statistics following RMA regressions of each architectural variable (muscle mass, PCSA, and fascicle length) against body mass

| Family | Variable | Functional group | Slope | 95% CIs | Y‐intercept | r |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Callitrichidae | Muscle mass | WE | 1.35 | 0.98–1.87 | −1.26 | 0.78 |

| DE | 1.29 | 0.90–1.86 | −1.35 | 0.75 | ||

| WF | 1.29 | 0.98–1.71 | −1.21 | 0.82 | ||

| DF | 1.24 | 0.91–1.70 | −1.04 | 0.79 | ||

| PS | 1.19 | 0.68–2.11 | −1.21 | 0.60 | ||

| PCSA | WE | 2.02 | 1.36–3.00 | −1.82 | 0.72 | |

| DE | 2.36 | 1.59–3.51 | −2.26 | 0.72 | ||

| WF | 2.15 | 1.52–3.04 | −1.89 | 0.76 | ||

| DF | 1.92 | 1.36–2.71 | −1.59 | 0.76 | ||

| PS | 1.97 | 1.09–3.57 | −1.75 | 0.59 | ||

| Fascicle length | WE | 1.56 | a | −1.39 | 0.20 | |

| DE | −1.87 | a | 1.34 | −0.26 | ||

| WF | −1.67 | a | 1.19 | −0.04 | ||

| DF | 1.57 | a | −1.39 | 0.02 | ||

| PS | −1.46 | a | 0.88 | −0.02 | ||

| Lemuridae | Muscle mass | WE | 1.15 | 0.68–1.92 | −1.11 | 0.77 |

| DE | 1.70 | 1.14–2.52 | −1.84 | 0.84 | ||

| WF | 1.18 | 0.79–1.76 | −1.11 | 0.83 | ||

| DF | 1.29 | 0.93–1.80 | −1.12 | 0.87 | ||

| PS | 1.35 | 0.96–1.89 | −1.40 | 0.87 | ||

| PCSA | WE | 1.28 | 0.45–3.65 | −1.26 | 0.59 | |

| DE | 1.70 | 0.96–3.02 | −1.85 | 0.74 | ||

| WF | 1.18 | 0.61–2.29 | −1.01 | 0.70 | ||

| DF | 1.41 | 0.80–2.48 | −1.21 | 0.75 | ||

| PS | 1.31 | 0.88–1.96 | −1.22 | 0.83 | ||

| Fascicle length | WE | 1.96 | 0.86–4.51 | −2.01 | 0.64 | |

| DE | 5.10 | 1.90–13.86 | −5.74 | 0.60 | ||

| WF | 1.72 | 0.70–4.25 | −1.94 | 0.62 | ||

| DF | 2.02 | 0.86–4.75 | −2.02 | 0.64 | ||

| PS | 2.03 | 0.97–4.25 | −2.36 | 0.67 |

Abbreviations: DE, digital extensors; DF, digital flexors; PS, pronators/supinators; WE, wrist extensors; WF, wrist flexors.

Indicates too much variation to ascribe significant confidence intervals.

FIGURE 3.

RMA regressions of each architectural variable (muscle mass, PCSA, and fascicle length) against body mass in each functional muscle group. All variables linearized and log‐transformed prior to analysis. Summary statistics presented in Table 3. In all cases, black line depicts callitrichids, and gray line depicts lemurids. Shapes indicate genus as follows: solid circles = Callithrix, asterisk = Callimico, solid triangles = Leontopithecus, solid squares = Mico, solid diamonds = Saguinus, open circles = Eulemur, open triangles = Hapalemur, open diamonds = Varecia, open squares = Lemur

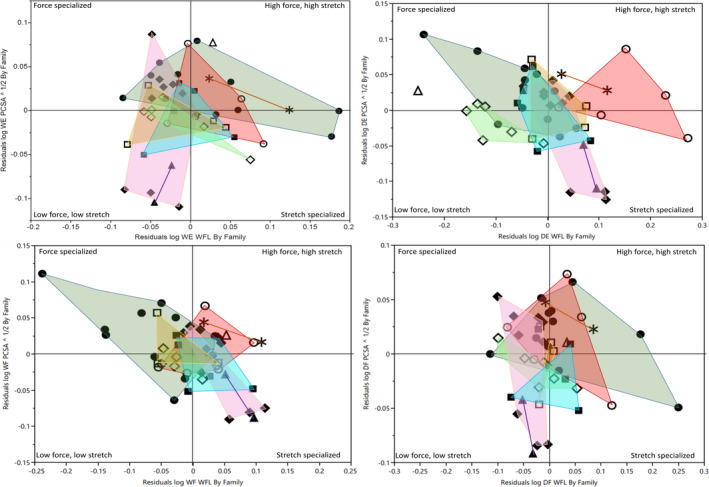

To assess relative muscle sizes, force, and excursion potential between taxa, RMA regressions of each variable were conducted (independently for each family) against body mass, and the resultant residuals extracted. These body‐size adjusted data were then analyzed to assess relative differences in architectural properties between genera and species within each family. Within Callitrichidae, two‐tailed Tukey–Kramer HSD tests revealed significant differences in relative muscle masses of the digital extensor and wrist flexor functional groups between Callimico and Leontopithecus—that is, when adjusted for body size, Callimico had relatively larger digital extensor and wrist flexor muscles than Leontopithecus. Callimico also approached significantly greater digital extensor (DE) and wrist flexor (WF) muscle masses relative to Saguinus (p = 0.06 and 0.13, respectively) and Mico (p = 0.11 and 0.09, respectively), though, possibly because of small intrageneric sample sizes, these differences merely approached significance. Significant differences were observed in pronator/supinator fascicle lengths between Callithrix and Leontopithecus, with the former being significantly longer. Differences between Callimico and Leontopithecus (following the same trends observed in DE and WF muscle masses) in pronator/supinator fascicle lengths also approached significance (p = 0.08). No relative differences were observed between any genera of Lemurid in any architectural variable. Finally, the relative residuals of muscle force and excursion potential for each genus are presented via functional space plots in Figure 4. Within lemurids, no consistent functional trends are observed, though it may be noted that Hapalemur shows consistently above average force potential in all functional muscle groups (most notably wrist extensors). Among callitrichids, our two most speciose genera (Callithrix and Saguinus) occupy distinct morphospaces only in the digital extensors. Additionally, Callimico occupies the high force, high stretch quadrant in all four functional groups. This likely reflects, in part, the increased muscle sizes observed in this genus (described above).

FIGURE 4.

Functional space plots showing relationship between relative muscle strength (residuals of PCSA vs body mass—PCSA) and relative muscle excursion potential (residuals of fascicle lengths vs body mass—WFL) in the four major functional compartments of the forearm. Residuals calculated independently within each family following RMA regressions of key variables against body mass. Abbreviations as follows: WE, wrist extensors; DE, digital extensors; WF, wrist flexors; DF, digital flexors. Shapes indicates genus following Figure 3. Colors as follows: dark green = Callithrix, brown = Callimico, purple = Leontopithecus, blue = Mico, pink = Saguinus, red = Eulemur, light green = Varecia, yellow = Lemur. Hapalemur is uncolored as the genus is represented by one data point (open triangle) in each plot

4. DISCUSSION

Despite widespread interest in the anatomy of the primate forearm as an adaptive indicator of ecology and behavior, the extent of myological variation within this region remains poorly understood. Currently, the most comprehensive descriptions of primate forearm variation are reported by Diogo and Wood (2012); yet even this fairly extensive dataset relies on a relatively small number of specimens to describe differences in overall forearm organization between genera and families. Within the Callitrichidae and Lemuridae, data are presented for only two genera each (Callithrix, Saguinus, Lemur, and Eulemur). Thus, finer‐scale data are needed to more comprehensively describe the magnitude of anatomical variation across these speciose lineages to better contextualize intergeneric differences by defining the extent of variation observed within each genus and to be able to contextualize variability in myology within subdivisions (especially those of such high interest) of the primate order.

We report that relative functional group masses remain highly conservative within each family (and, indeed, between the two families). However, the organization of muscles within several functional groups is shown to be highly variable, particularly among the Callitrichidae. First, our data suggest that, in both families, fusion of the FDS and FDP to form a common digital flexor is the typical state. Previous accounts described the relationship between FDS and FDP as highly variable (Diogo & Wood, 2012), and, though we confirm this variability, a significant majority of both Callitrichid (83%) and Lemurid (69%) specimens presented a fused condition, clearly indicating this to be the more typical state in both lineages.

Similarly, our data suggest that within the digital extensor functional group, a common EDP is the typical condition observed within Callitrichidae. This configuration, observed in 90% of our specimens, matches the description of this functional group presented by Diogo and Wood (2012), who describe this configuration as found in Callithrix among other the new‐world primate genera Saimiri, Aotus, and Pithecia on the basis of accounts by Barnard (1875), Duckworth (1904), Senft (1907), Beattie (1927), Hill (1957), Ziemer (1972), Kaneff (1980), Dunlap et al., (1985), and Aziz and Dunlap (1986). In describing this configuration as typical among Callitrichidae, we propose adding the genera Saguinus, Callimico, Mico, and Leontopithecus to this list.

Significant sources of variation are also observed elsewhere within the digital extensors, most prominently associated with the third digit. Indeed, some variant of an accessory digital extensor associated with Digit III was observed in the majority of both callitrichids and lemurids, though this muscle presented in multiple forms: a distinct muscle belly and tendon associated with the third digit alone (EDIII; in 80% of callitrichids and 63% of lemurids), a bifurcation between Digits III and IV (EDIII + IV in 13% of callitrichids), or an accessory tendon from the extensor digit II (i.e., EDII + III; in 3% of callitrichids). The remaining specimens (one individual each of C. jacchus, Eulemur coronatus, Varecia rubra, and Varecia variegata) presented no accessory attachments to the third digit—just the tendon of the common digital extensor. This magnitude of variation was surprising as accessory tendons of this nature are theoretically associated with highly specialized dexterity, yet both lemurids and callitrichids are typically described as unspecialized in dexterity and having fewer muscles dedicated to manipulating individual digits (Lemelin & Diogo, 2016). We consider two possible explanations for this observation. In the first, the functional role of this digit may be relatively small within these taxa such that selection for a specific, “optimized” configuration is relaxed and multiple variants of organization may characterize these families. Alternatively, the high independence of muscle bellies and tendons associated with Digit III (a specialization consistently absent in our own highly dexterous species) might suggest some functional differentiation of this digit within these taxa that future studies into hand‐usage patterns within these lineages (and particularly within the Callitrichidae) may wish to further explore.

Compared to this organizational diversity, architectural variables within the forearm demonstrated more conservative trends. Between functional groups, all three architectural variables (muscle mass, fascicle lengths, and PCSA) scale similarly relative to body mass, though fascicle lengths within Callitrichidae appeared relatively unrelated to changes in body size. Overall scaling patterns within the forearm musculature of our data are variably comparable with those reported for a mixed primate sample by Leischner et al., (2018), wherein both muscle mass and PCSA generally scale with positive allometry to body mass. Analyzing our families independently, we find that callitrichids follow this previously reported trend, whereas lemurids generally scale with isometry in both mass and PCSA. Thus, while relative forearm strength increases with body size within callitrichids (and within primates as a whole), lemurids maintain a similar relative force capacity across their body‐size spectrum.

The weak scaling relationship between forearm fascicle lengths and body mass within callitrichids might reflect either (a) lower functional constraints on maintaining FLs within these taxa such that suitable function can be maintained across a wide range of fascicle lengths or (b) that this functional range is relatively independent of body size such that all taxa occupy a relatively similar range of FLs. An analysis of our data unadjusted for body mass supports the latter interpretation: a Tukey–Kramer HSD demonstrates no statistically significant differences in raw fascicle length values between any genera with the Callitrichidae (Figure 5). Thus, despite a range of body sizes that span from ~100 to 600 g, all callitrichid genera analyzed herein present indistinguishable fascicle lengths across each functional group of the forearm. This remarkable consistency might be interpreted to reflect a narrow ecological niche occupied by all Callitrichidae, such that fascicle lengths in all taxa are optimized toward facilitating specific behaviors that require comparable ranges of muscular excursion.

FIGURE 5.

Weighted fascicle lengths (FL) within each functional group of the forearm within five callitrichid genera. Abbreviations as follows: WF, wrist flexors; WE, wrist extensors; DF, digital flexors; DE, digital extensors; PS, pronators/supinators. Within each plot, central line indicates group mean; intermediate lines (overlap marks) indicate statistical significance between groups if overlap is not observed, or insignificance if two sets overlap; diamond tips indicates 95% confidence intervals for each group, assuming equal variance. All shapes indicate single data points

Finally, analyzing intergeneric differences in muscle size and force potential reveals generally consistent trends within both lemurids and callitrichids. The one notable exception to this is the genus Callimico, which presents significantly larger digital extensors and wrist flexors than would be expected for its body size (Figure 6). Indeed, in all five functional groups, Callimico presents the largest relative muscle masses and PCSA values, suggesting a meaningful increase in relative forearm size and strength within this genus relative to its sister genera. This differentiation may reflect the unique locomotor repertoire of Callimico among its family, with the taxon described as “distinct among callitrichines” in the degree to which vertical climbing and trunk‐to‐trunk leaping dominate its locomotor repertoire (Garber & Porter, 2009, p. 10). Indeed, observational data on substrate use and locomotor behaviors within this species report frequent occupation of the lowest canopy levels, with the majority of locomotor events (55.1%) representing leaps between vertically oriented tree trunks. By contrast, sympatric populations of Saguinus (represented by Saguinus labiatus and Saguinus fuscicollis) more frequently occupied middle and upper canopy levels, with 49.5% of locomotor events occurring between smaller, flexible terminal substrates and just 14.2% of traveling events occurring between tree trunks (Garber & Leigh, 2001). A more recent analysis of substrate use within five species of Saguinus further emphasized this difference, downgrading the role of trunk‐to‐trunk leaping in the locomotor repertoire of this genus to just 1.5–7.7% (Garber et al., 2009). This latter study also presents data for Callithrix, noting that—like Saguinus—leaping events are largely restricted to travel between small diameter substrates in the middle and upper canopies (Garber et al., 2009).

FIGURE 6.

Residuals of digital extensor muscle mass (DE MM), wrist flexor muscle mass (WF MM), and pronator/supinator fascicle lengths (PS WFL) across five callitrichid genera, following reduced major axis regressions against body mass. Abbreviations as follows: WF, wrist flexors; DE, digital extensors. Within each plot, central line indicates group mean; intermediate lines (overlap marks) indicate statistical significance between groups if overlap is not observed, or insignificance if two sets overlap; diamond tips indicates 95% confidence intervals for each group, assuming equal variance. All circles indicate single data points

The increased emphasis by Callimico on vertical leaping between trunks has been studied in the hindlimb, where an elongated hindlimb enhances propulsive force generation and adaptations within the ankle serve to maximize joint stability during takeoff and landing (Davis, 2002; Garber et al., 2005; Garber & Leigh, 2001). Our findings preliminarily suggest that their distinct locomotor repertoire might also influence the anatomy of their forearm musculature, driving relative increases in forearm muscle size and strength across muscle functional groups. We hypothesize that this increased strength may assist in supporting body mass and resist gravity during the increased time spent clinging to vertical substrates; however, behavioral analyses on the relative use of the hindlimb and forelimb of Callimico during vertical postures would be necessary to explore this further.

Overall, our findings highlight a previously unquantified degree of variation in the organization of forearm muscles within two primate families. Both Callitrichidae and Lemuridae exhibit substantial variation in the anatomy of this region, often even intraspecifically and intragenerically. This observation emphasizes the dangers of relying upon single specimens to serve as templates for the anatomy of a species or genus and supports exercising caution when relying on single descriptions of a species anatomy. Comparatively, greater variation can be observed in categorical variables (e.g., muscle fusion and bifurcation) than in architectural variables, which appear more conservative within each species and genus. However, expanding a similarly rigorous approach to myological variation in other anatomical regions and within additional primate families is necessary to further elucidate this trend.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

This project was conceived by AHR, MLB, and ED. All authors contributed in part to the collection and analysis of data. UVA specimens were sourced and made available by FP. Drafting of the manuscript was performed by ED, MLB, MRS, NAW, SRS, and JSS. Revision of the manuscript was performed by FP and AHR.

Supporting information

Table S1

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

We would like to thank Taylor Beck and Isabella Hertzig for their assistance with data collection. We are also grateful to the Lemur Conservation Foundation, the Duke Lemur Center, and the North Carolina Zoo for contributing lemurid specimens toward this study. This is Duke Lemur Center publication #1478. This research was funded by the National Science Foundation IOS‐15‐57125 and BCS‐14‐40599.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article. Complete raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, particularly from potential collaborators with additional comparative data.

REFERENCES

- Anapol, F. & Barry, K. (1996) Fiber architecture of the extensors of the hindlimb in semiterrestrial and arboreal guenons. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 99, 429–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashton, E. & Oxnard, C. (1964) Functional adaptations in the primate shoulder girdle. In: Proceedings of the Zoological Society of London. Wiley Online Library, pp. 49–66. [Google Scholar]

- Aversi‐Ferreira, T.A. , Diogo, R. , Potau, J.M. , Bello, G. , Pastor, J.F. & Aziz, M.A. (2010) Comparative Anatomical Study of the Forearm Extensor Muscles of Cebus libidinosus (Rylands et al., 2000; Primates, Cebidae), Modern Humans, and Other Primates, With Comments on Primate Evolution, Phylogeny, and Manipulatory Behavior. The Anatomical Record, 293, 2056–2070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz, M.A. & Dunlap, S.S. (1986) The human extensor digitorum profundus muscle with comments on the evolution of the primate hand. Primates, 27, 293–319. [Google Scholar]

- Barnard, W. (1875) Observations on the membral musculation of Simia satyrus (Orang) and the comparative myology of man and the apes. Proceedings of the American Association for the Advancement of Science, 24, 112–144. [Google Scholar]

- Beattie, J. (1927) The anatomy of the common marmoset (Hapale jacchus Kuhl). Proceeding of the Zoology Society of London, 593–718. [Google Scholar]

- Bodine, S.C. , Roy, R. , Meadows, D. , Zernicke, R. , Sacks, R. , Fournier, M. et al. (1982) Architectural, histochemical, and contractile characteristics of a unique biarticular muscle: the cat semitendinosus. Journal of Neurophysiology, 48, 192–201. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher, M.L. , Leonard, K.C. , Dickinson, E. , Aujard, F. , Herrel, A. & Hartstone‐Rose, A. (2020) The forearm musculature of the gray mouse lemur (Microcebus murinus): An Ontogenetic Study. The Anatomical Record, 303, 1354–1363. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher, M.L. , Leonard, K.C. , Dickinson, E. , Herrel, A. & Hartstone‐Rose, A. (2019) Extraordinary grip strength and specialized myology in the hyper‐derived hand of Perodicticus potto? Journal of Anatomy, 931–939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boettcher, M. , Leonard, K.C. , Herrel, A. & Hartstone‐Rose, A. (2020) The soft‐tissue anatomy of the highly derived hand of Perodicticus relative to the more generalized Nycticebus . In: Nekaris, A. & Burrows, A.M. (Eds.) Evolution, Ecology and Conservation of Lorises and Pottos. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, pp. 76–96. [Google Scholar]

- Cartmill, M. (1972) Arboreal adaptations and the origin of the order Primates. In: Tuttle, R.L. (Ed.) The Functional and Evolutionary Biology of Primates. Chicago: Aldine‐Atherton, pp. 97–122. [Google Scholar]

- Davis, L. (2002) Functional morphology of the forelimb and long bones in the Callitrichidae (Platyrrhini: Primates). PhD Thesis. Carbondale, IL: Southern Illinois University. [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, R. , Richmond, B.G. & Wood, B. (2012) Evolution and homologies of primate and modern human hand and forearm muscles, with notes on thumb movements and tool use. Journal of Human Evolution, 63, 64–78. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, R. & Wood, B. (2011) Soft‐tissue anatomy of the primates: phylogenetic analyses based on the muscles of the head, neck, pectoral region and upper limb, with notes on the evolution of these muscles. Journal of Anatomy, 219, 273–359. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diogo, R. & Wood, B. (2012) Comparative anatomy and phylogeny of primate muscles and human evolution. Oxford: Taylor & Francis. [Google Scholar]

- Duckworth, J.W. (1904) Studies from the Anthropological Laboratory, the Anatomy School, Cambridge. London: C.J. Clay & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Dunlap, S. , Thorington, R. & Aziz, M. (1985) Forelimb anatomy of New World monkeys: Myology and the interpretation of primitive anthropoid models. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 68, 499–517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans, C. & Bock, W.J. (1965) The functional significance of muscle architecture–a theoretical analysis. Ergebnisse der Anatomie und Entwicklungsgeschichte, 38, 115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gans, C. & Gaunt, A.S. (1991) Muscle architecture in relation to function. Journal of Biomechanics, 24, 53–65. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber, P.A. (1980) Locomotor behavior and feeding ecology of the Panamanian tamarin (Saguinus oedipus geoffroyi, Callitrichidae, Primates). International Journal of Primatology, 1, 185–201. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, P. , Blomquist, G. & Anzenberger, G. (2005) Kinematic analysis of trunk‐to‐trunk leaping in Callimico goeldii . International Journal of Primatology, 26, 223–240. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, P. & Leigh, S. (2001) Patterns of positional behavior in mixed‐species troops of Callimico goeldii, Saguinus labiatus, and Saguinus fuscicollis in northwestern Brazil. American Journal of Primatology, 54, 17–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garber, P.A. & Porter, L.M. (2009) Trunk‐to‐trunk leaping in wild Callimico goeldii in Northern Bolivia. Neotropical Primates, 16, 9–14. [Google Scholar]

- Garber, P.A. , Sallenave, A. , Blomquist, G.E. & Anzenberger, G. (2009) A comparative study of the kinematics of trunk‐to‐trunk leaping in Callimico goeldii, Callithrix jacchus, and Cebuella pygmaea . In: Ford, S. , Porter, L.M. & Davis, L. (Eds.) The Smallest Anthropoids. Boston, MA: Springer, pp. 259–277. [Google Scholar]

- Gokhin, D.S. , Bang, M.‐L. , Zhang, J. , Chen, J. & Lieber, R.L. (2009) Reduced thin filament length in nebulin‐knockout skeletal muscle alters isometric contractile properties. American Journal of Physiology‐Cell Physiology, 296, C1123–C1132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gyambibi, A. & Lemelin, P. (2013) Comparative and quantitative myology of the forearm and hand of prosimian primates. The Anatomical Record, 296, 1196–1206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartstone‐Rose, A. , Perry, J.M. & Morrow, C.J. (2012) Bite force estimation and the fiber architecture of felid masticatory muscles. The Anatomical Record, 295, 1336–1351. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Herrel, A. , De Smet, A. , Aguirre, L.F. & Aerts, P. (2008) Morphological and mechanical determinants of bite force in bats: do muscles matter? Journal of Experimental Biology, 211, 86–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hill, W.C.O. (1957) Primates: comparative anatomy and taxonomy; III Pithecoidea Platyrrhini. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Hopkins, W.D. , Russell, J.L. , Remkus, M. , Freeman, H. & Schapiro, S.J. (2007) Handedness and grooming in Pan troglodytes: comparative analysis between findings in captive and wild individuals. International Journal of Primatology, 28, 1315–1326. [Google Scholar]

- Hunt, K.D. , Cant, J.G.H. , Gebo, D.L. , Rose, M.D. , Walker, S.E. & Youlatos, D. (1996) Standardized descriptions of primate locomotor and postural modes. Primates, 37, 363–387. [Google Scholar]

- Kaneff, X.X. (1980) Évolution morphologique des musculi extensores digitorum et abductor pollicis longus chez l’Homme. III. Évolution morphologique du m. extensor indicis chez l’homme, conclusion générale sur l’évolution morphologique des musculi extensores digitorum et abductor pollicis longus chez l’homme. Gegenbaurs Morphologisches Jahrbuch, 126, 774–815. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kikuchi, Y. (2010) Comparative analysis of muscle architecture in primate arm and forearm. Anatomia, Histologia, Embryologia, 39, 93–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leischner, C. , Crouch, M. , Allen, K. , Marchi, D. , Pastor, F. & Hartstone‐Rose, A. (2018) Scaling of primate forearm muscle architecture as it relates to locomotion and posture. The Anatomical Record, 301, 484–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin, P. & Diogo, R. (2016) Anatomy, function, and evolution of the primate hand musculature. In: Kivell, T.L. , Lemelin, P. , Richmond, B.G. & Schmitt, D. (Eds). Evolution of the Primate Hand. pp. 155–193. [Google Scholar]

- Lemelin, P. & Grafton, B.W. (1998) Grasping performance in Saguinus midas and the evolution of hand prehensility in primates. In: Strasser, E. , Fleagle, J.G. , Rosenberger, A.L. & McHenry, H.M. (Eds.) Primate Locomotion. Springer, pp. 131–144. [Google Scholar]

- Leonard, K.C. , Boettcher, M.L. , Dickinson, E. , Malhotra, N. , Aujard, F. , Herrel, A. et al. (2020) The ontogeny of masticatory muscle architecture in Microcebus murinus . The Anatomical Record, 303, 1364–1373. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, R.L. (1986) Skeletal muscle adaptability. I: Review of basic properties. Developmental Medicine & Child Neurology, 28, 390–397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, R.L. & Fridén, J. (2000) Functional and clinical significance of skeletal muscle architecture. Muscle & Nerve, 23, 1647–1666. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lieber, R.L. & Ward, S.R. (2011) Skeletal muscle design to meet functional demands. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society of London B: Biological Sciences, 366, 1466–1476. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Michilsens, F. , Vereecke, E.E. , D'Août, K. & Aerts, P. (2009) Functional anatomy of the gibbon forelimb: adaptations to a brachiating lifestyle. Journal of Anatomy, 215, 335–354. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, G. & Tokunaga, D.H. (1976) Sex differences in nonhuman primate grooming. Behavioural Processes, 1, 335–345. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mittermeier, R.A. , Wilson, D.E. & Rylands, A.B. (2013) Handbook of the mammals of the world: primates. Barcelona: Lynx Edicions. [Google Scholar]

- Murphy, R. & Beardsley, A.C. (1974) Mechanical properties of the cat soleus muscle in situ. American Journal of Physiology‐Legacy Content, 227, 1008–1013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Myatt, J.P. , Crompton, R.H. , Payne‐Davis, R.C. , Vereecke, E.E. , Isler, K. , Savage, R. et al. (2012) Functional adaptations in the forelimb muscles of non‐human great apes. Journal of Anatomy, 220, 13–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reghem, E. , Byron, C. , Bels, V. & Pouydebat, E. (2012) Hand posture in the grey mouse lemur during arboreal locomotion on narrow branches. Journal of Zoology, 288, 76–81. [Google Scholar]

- Reghem, E. , Tia, B. , Bels, V. & Pouydebat, E. (2011) Food prehension and manipulation in Microcebus murinus (Prosimii, Cheirogaleidae). Folia Primatologica, 82, 177–188. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, D. (1998) Forelimb mechanics during arboreal and terrestrial quadrupedalism in Old World monkeys. In: Primate locomotion. Springer. pp. 175–200. [Google Scholar]

- Schmitt, D. & Lemelin, P. (2002) Origins of primate locomotion: Gait mechanics of the woolly opossum. American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 118, 231–238. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schumacher, G. (1961) Funktionelle morphologie der kaumuskulatur. Jena: Fisher. [Google Scholar]

- Senft, M. (1907) Myologie der Vorderextremitäten von Hapale jacchus, Cebus macrocephalus, und Ateles ater. PhD Thesis. Bern: Bern University. [Google Scholar]

- Sussman, R.W. & Raven, P.H. (1978) Pollination by lemurs and marsupials: An archaic coevolutionary system. Science, 200(4343), 731–736. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thorpe, S.K. , Crompton, R.H. , Guenther, M.M. , Ker, R.F. & McNeill, A.R. (1999) Dimensions and moment arms of the hind‐and forelimb muscles of common chimpanzees (Pan troglodytes). American Journal of Physical Anthropology, 110, 179–199. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Toussaint, S. , Reghem, E. , Chotard, H. , Herrel, A. , Ross, C. & Pouydebat, E. (2013) Food acquisition on arboreal substrates by the grey mouse lemur: implication for primate grasping evolution. Journal of Zoology, 291, 235–242. [Google Scholar]

- Van Leeuwen, T. , Vanhoof, M.J. , Kerkhof, F.D. , Stevens, J.M. & Vereecke, E.E. (2018) Insights into the musculature of the bonobo hand. Journal of Anatomy, 233, 328–340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ziemer, L.K. (1972). An atlas of the skeleton and musculature of the shoulder, arm and forearm of Pithecia monacha . MA Thesis. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Table S1

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available in the supplementary material of this article. Complete raw data are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request, particularly from potential collaborators with additional comparative data.