Abstract

Background

This study aimed to evaluate the efficacy of external vibrating devices and counterstimulation on a child's dental anxiety, apprehension, and pain perception during local anesthetic administration.

Methods

This was a prospective, randomized, parallel-arm, single-blinded interventional, clinical trial. One hundred children aged 4–11 years, requiring pulp therapy or extraction under local anesthesia (LA), were recruited and allocated equally into two groups (1:1) based on the interventions used: Group BD (n = 50) received vibration using a Buzzy® device {MMJ Labs, Atlanta, GE, USA} as a behavior guidance technique; Group CS (n = 50) received counterstimulation for the same technique. Anxiety levels [Venham's Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale (VCARS), Venham Picture Test (VPT), Pulse oximeter {Gibson, Fingertip Pulse Oximeter}, Beijing, China)] were assessed before, during, and after LA administration, while pain perception [Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale (WBFPS), Visual Analogue Scale (VAS)] was evaluated immediately after injection. Statistical analysis was performed using the Student's t-test to assess the mean difference between the two groups and the repeated measures ANOVA for testing the mean difference in the pulse rates. Statistical significance was set at P < 0.05.

Results

Significant differences in mean pulse rate values were observed in both groups. In contrast, the children in the BD group had higher diminution (P < 0.05), whereas the mean VCARS and VPT scores were conspicuous (P < 0.05). Based on the mean WBFPS and VAS scores, delayed pain perception after LA injection was more prominent in the BD group than in the CS group.

Conclusion

External vibration using a Buzzy® device is comparatively better than counterstimulation in alleviating needle-associated anxiety in children requiring extraction and pulpectomy.

Keywords: Anesthesia, Child, Dental Anxiety, Pain, Pulpectomy, Vibration

INTRODUCTION

In general context, pain is “an unpleasant sensory or emotional experience associated with actual or potential tissue damage or described in terms of such damage”" [1]. Extreme pain can result in short or protracted physiological, psychological, and emotional outcomes. The administration of local anesthesia (LA) is an ubiquitous method for alleviating dental pain; however, needle-related procedures are essential sources of fear and anxiety in children, as they have an ingrained fear of sharp and pointed objects [2]. According to Bienvenu and Eaton, children with needle phobia experienced unpleasant needle insertion in the past [3]. Therefore, children may perceive different intensities of pain from a similar stimulus (e.g., dental injection).

Fear and anxiety-related behavior, especially during dental procedures, can be a significant impediment to dental care and may adversely impact the child's overall oral health and well-being. Okawa et al. suggested that children reported elevated dental pain when they were highly anxious [4]. According to Rachman, conditioning (direct response), modeling, and information (indirect responses) are three factors promoting dental anxiety in children [5]. Hmud and Walsh (2009) identified the “4S factors” for children's dental anxiety; these include sights (e.g., feeling of uneasiness and worry), sounds (drilling), sensations (high-frequency vibrations with a high annoyance factor), and smells (odors, such as eugenol and bonding agents) [6].

Behavior modification of disruptive and apprehensive children during dental visits should follow a two-step session: handling the child while treating their dental problems and identifying possible techniques to manage their dental anxiety [7]. Gaining the child's attention towards the treatment and targeting their cognitive abilities are imperative for achieving a constructive child-dentist relationship, alleviating fear and anxiety, building trust and rapport, and instilling a positive dental attitude for future appointments. Effective management of pain in children during dental appointments is the basis of successful behavior guidance [8].

Non-pharmacological behavior guidance techniques (BGTs) have proven to be the gold standard interventions for managing children experiencing needle-related pain. Various non-pharmacological BGTs reported in the literature include the following: Tell-Show-Do (TSD), modeling, voice control, hypnosis, acupuncture, biofeedback, guided imagery, and distraction using storytelling, audio, or audiovisual aids, which target the psychological facet of the child; these are highly acceptable, as they do not result in repercussions [9,10]. During dental procedures, distraction involves diverting a child's attention away from an unpleasant stimulus. Consequently, distraction is a safe and inexpensive intervention that reduces the time and number of personnel required to perform the procedure.

An alternative method to allay injection pain is pre-cooling the injection site. The application of cold stimuli on the injection site before LA administration remains an easy and physiologically effective procedure without any surplus costs [11]. Harbert stated that cooling the palatal region before injection significantly relieves pain perception [12]. Recently, the use of gels under cold temperatures as an adjunct to a vibrating device has also shown promising results. It has been anticipated that these vibrating devices will generate a distracting environment that causes brain cells to relay the vibrations, thereby allowing the anesthetic to be administered. The rationale for using both cold (temperature) and vibration (stimulation) is based on the idea that pain relies on the patient's attention and perception as a psychological component. The addition of the cold element further confuses the pain pathway's reception of signals, allowing for a “masking effect of pain” [13].

Despite developments in pediatric dentistry, injections remain a source of discomfort and concern; however, no standard injection technique has been established to date. Nevertheless, an easy-to-use, quick, noninvasive, low-cost, and reusable intervention can be an exciting surrogate, particularly in acute situations where needle-related procedures have a limited preparation time. One such device with the aforementioned properties is the Buzzy® device (BD). Buzzy® (MMJ Labs, Atlanta, GE, USA) is a bee-shaped apparatus consisting of two parts: the body of a bee and detachable ice-wings. The Buzzy® device is primarily based on Melzack and Wall's (1965) gate control theory of pain and the descending inhibitory mechanism. Apparently, the vibration is hypothesized to block the afferent pain-sensitive fibers (A-delta and C-fibers) by stimulating the non-noxious A-beta fibers, which will further stimulate an inhibitory interneuron, thereby reducing the pain information transferred to the spinal cord. Furthermore, while a protracted cold treatment (30 – 60 secs) is placed closer to the nociception site, it activates the c-nociceptive fibers and further blocks the A-delta pain transmission signal [14]. Additionally, gentle stroking of the mucosa with topical anesthesia while administering the injection has been proven to be utilitarian in medicine [15]. Aminabadi et al. proved that counter-stimulation (CS) is helpful in reducing pain at the time of LA administration in 4- to 5-year-old children [16].

The literature reports that BD and CS could be potential measures for pain and anxiety alleviation; however, no study has compared these techniques. Hence, the present study was conducted to compare and evaluate the efficacy of BD and CS on dental anxiety and pain perception during LA administration in children. The null hypothesis of this study was that BD is superior to CS in alleviating dental anxiety.

METHODS

1. Study design

A prospective, randomized, parallel-arm, single-blinded, interventional, clinical trial with a balanced allocation ratio of 1:1 was conducted on children attending the Department of Pediatric and Preventive Dentistry. Institutional ethical committee clearance was obtained and registered with the university (No: D188407007). Written informed consent was obtained from the parents or guardians of the children enrolled in the study.

2. Patient collection

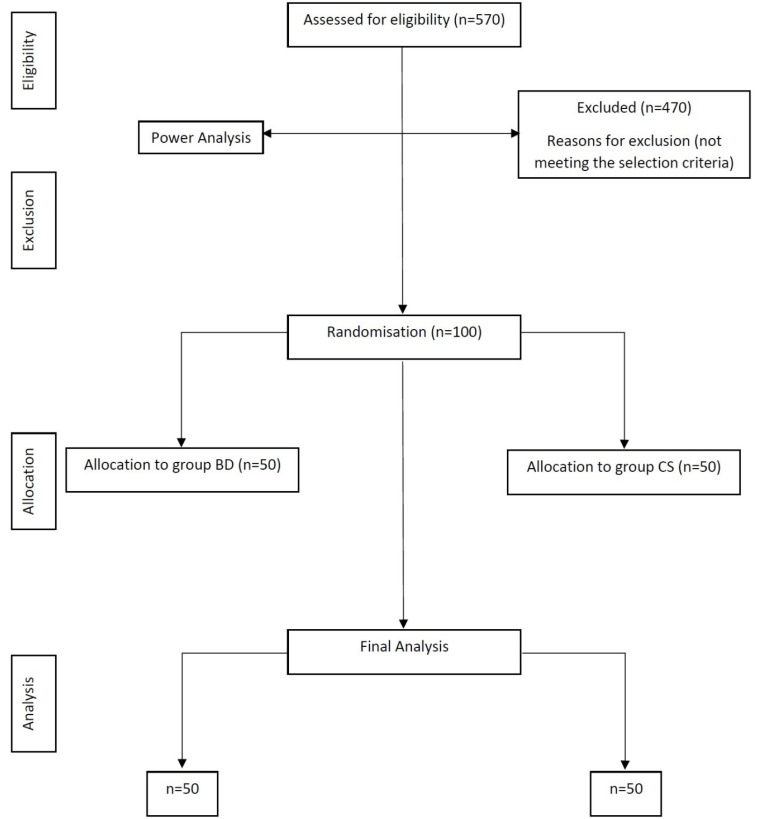

Healthy children with normal body mass index percentile for age (ASA 1 classification) and anxious children aged 4–11 years (positive and negative Frankl behavior rating) who had no previous experience with LA administration were included in the study. Frankl's definitely positive and definitely negative children and those with special healthcare needs who required pharmacological behavior management were excluded from the study. The children were further divided into two age groups: group 1, 4–7 years old; group 2, 8–11 years old, keeping in mind that the psychology and mental status of 4-year-old children are different from those of 8-year-old children. Sample size determination was performed based on the findings from a pilot study that was conducted on 10 children (five in each group), taking an alpha error of 0.05% and power of 85 %; a final sample size of 100 was determined. Based on random numbers, the total number of children (n = 100) was divided into two groups, with 50 children (BD and CS) in each group (Fig. 1). The procedure was described in detail to the parents and children in simple terms before the start of treatment, with LA administration being the major aspect explained.

Fig. 1. CONSORT flow diagram.

3. Group I (Buzzy® device)

Buzzy® comprises two components: an external vibrating component that resembles a honeybee's body, and a pre-cooling component that is designed in the form of a honeybee's wings. Buzzy® is a noninvasive, childfriendly, and economical tool that can reduce pain perception in children undergoing LA administration [14]. After being seated in a dental chair, the children were initially introduced to the device by demonstrating its function in simple words; next, the child was allowed to play with the Buzzy® for familiarization purposes. The device was then connected to the frozen wing; Buzzy® was placed extra-orally above the cheek region where the LA was to be administered (Fig. 2).

Fig. 2. Placement of Buzzy® Device before LA injection.

4. Group II (Counter-stimulation)

Counter stimulation involves gentle vibration or stimulation of the mucosa near the LA administration site with the thumb and applying light pressure to an analogous extra-oral area with the forefinger (Fig. 3).

Fig. 3. Stroking the cheek and the extra-oral mucosa (Counter-stimulation).

5. Materials for assessing a child's level of anxiety

1) Physiological parameters were recorded using a pulse oximeter (Gibson, Fingertip Pulse Oximeter, Beijing, China).

2) Subjective scales for reporting pain were recorded using:

a) Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale (WBFPS) [17].

b) Visual Analogue Scale (VAS) [18].

3) Subjective Venham's picture Test (VPT) was used for reporting anxiety [19].

4) Venham's Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale (VCARS) [20] was used to record the objective scales of anxiety levels in children.

6. Method of study evolution

Initially, anxiety levels were measured with a pulse oximeter, VCARS, and VPT 15 min before LA administration in both groups. The needle prick site was dried with sterile gauze; 20% benzocaine topical anesthetic gel was applied with a cotton applicator for 30 secs. Subsequently, infiltration anesthesia was performed in all children using a 23-gauge needle; 2% lidocaine with 1:80,000 adrenaline anesthetic solution was injected at approximately 1mL / min. For Groups I (n = 50) and II (n = 50), the Buzzy® device with ice-wings and the counter-stimulation method were performed as behavior guidance techniques, respectively. Following the delivery of LA, pain perception was measured using WBFPS and VAS; similarly, the anxiety levels were evaluated using pulse oximetry, VCARS, and VPT. Standard extraction and pulp therapy procedures were performed after obtaining profound anesthesia (i.e., after 5 min).

7. Statistical analysis

Statistical analysis was performed using the standard statistical package (SPSS) version 22 (IBM, USA). The values for categorical variables are expressed as percentages and numbers, whereas continuous variables are reported as mean and standard deviation. The inter- and intra-group comparisons of the WBFPS, VAS, VPT, VCARS, and pulse rates were assessed using the chi-squared and paired t-tests, respectively. Repeated measures of ANOVA were used to investigate continuous changes in the pulse rate. All p-values < 0.05 are considered statistically significant (P < 0.05).

RESULTS

In this study, 100 children were enrolled and subsequently divided into two groups, with almost equal gender distribution (BD: 48% boys, 52% girls; CS: 52% boys, 48% girls). The mean age of the children was 8.80 ± 1.38 in boys and 8.91 ± 1.44 in girls. The percentage of extractions was 46.6% in the (BD) group and 53.9% in the (CS) group; pulpal therapies in the mandibular primary molars were performed in 53.4% (BD) and 46.6% (CS) of children among each group. There were no significant differences between the groups in terms of age, sex, and type of treatment. Intergroup comparisons between mean values of self-reported pain during LA administration (WBFPS, P = 0.001; VAS, P = 0.001) were statistically significant. Similarly, a statistically significant difference was observed in the objective parameter, VCARS, recorded before and after LA administration in both groups (Table 1). The subjective parameter, VPT, recorded before the administration of LA (P = 0.653), was not statistically significant in the two groups, but a statistically significant difference (P = 0.001) was observed after the procedure.

Table 1. Details of the studies with possible biases and confounding factors.

| Subjective | Group | Mean | SD | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| WBFPS | BD | 1.98 | 1.35 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 5.16 | 1.89 | ||

| VAS | BD | 1.96 | 1.35 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 5.22 | 1.63 | ||

| Objective (VCARS) | ||||

| Before | BD | 3.06 | 1.30 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 4.78 | 1.58 | ||

| After | BD | 1.22 | 0.91 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 4.92 | 1.52 | ||

| Subjective (VPT) | ||||

| Before | BD | 4.88 | 1.46 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 4.78 | 1.58 | ||

| After | BD | 2.34 | 1.39 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 5.04 | 1.63 | ||

| Physiologic (PULSE RATE) | ||||

| Before | BD | 99.36 | 14.88 | 0.485 |

| CS | 97.27 | 15.01 | ||

| During | BD | 90.11 | 12.28 | 0.001* |

| CS | 100.2 | 16.22 | ||

| After | BD | 88.06 | 10.76 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 100.5 | 13.49 |

*P < 0.05 - Statistically significant; **P < 0.001 - Highly significant

BD, Buzzy Device; CS, Counter Stimulation; SD, Standard Deviation; WBFPS, Wong-Baker Faces Pain Rating Scale; VAS, Visual Analog Scale; VCARS, Venham's Clinical Anxiety Rating Scale; VPT, Venham Picture Test.

A statistically significant difference was observed between the mean values of physiologic measures (pulse rate) before (P = 0.001) and after (P = 0.001) LA administration. At baseline, there were no significant variations in the pulse rates between the two groups. The BD group displayed a statistically significant difference

(P = 0.001) in the mean VCARS scores before and after LA administration; however, in the CS group, no statistically significant (P = 0.466) differences were noted (Table 2). A decrease in pulse rates was observed with the interventions in both groups after the administration of LA; the BD group showed a significantly higher pulse rate reduction. The WBFPS and VAS scores demonstrated lesser discomfort with LA needle insertion in the BD group than in the CS group.

Table 2. Intragroup comparison of VCARS.

| Group | Mean | SD | Difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD | Before | 3.06 | 1.30 | 1.84 ± 0.39 | < 0.001** |

| After | 1.22 | 0.91 | |||

| CS | Before | 4.78 | 1.58 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.466; NS |

| After | 4.92 | 1.52 |

Wilcoxon-Signed Rank Test: NS: P > 0.05; Not significant; **P < 0.001; Highly significant. BD, Buzzy Device; CS, Counter Stimulation; SD, Standard Deviation.

In both groups, objective assessment using the VCARS scores revealed a reduction in the BD group (P = 0.001), but showed no variation in the CS group (P = 0.824). The post-intervention pulse rate showed a significant difference when measured with a pulse oximeter; in contrast, children in the BD group had a more significant reduction in their anxiety levels (Table 3). When the anxiety-measuring parameters were compared across the two age groups (4–7 and 8–11 years), it was observed that children in the Buzzy® group of both age groups displayed similar anxiety levels, irrespective of their cognitive development (Table 4 and 5).

Table 3. Intragroup comparison of VPT.

| Group | Mean | SD | Difference | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| BD | Before | 4.88 | 1.46 | 3.1 ± 0.20 | < 0.001** |

| After | 1.78 | 1.26 | |||

| CS | Before | 4.78 | 1.58 | 0.14 ± 0.06 | 0.309; NS |

| After | 5.04 | 1.62 |

Wilcoxon-Signed Rank Test: NS: P > 0.05; Not significant; **P < 0.001; Highly significant. BD, Buzzy Device; CS, Counter Stimulation; SD, Standard Deviation; VPT, Venham Picture Test.

Table 4. Intra-group comparison among mean values of pulse rate (before versus during), (during versus after), and (before versus after) LA administration.

| Group | Pulse (Before) | Pulse (During) | P-value | Pulse (During) | Pulse (After) | P-value | Pulse (Before) | Pulse (After) | P-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | ||||

| BD | 99.36 ± 14.88 | 90.11 ± 12.28 | < 0.001** | 90.11 ± 12.28 | 88.06 ± 10.76 | < 0.001** | 99.36 ± 14.88 | 88.06 ± 10.76 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 97.27 ± 15.01 | 100.24 ± 16.22 | 0.05 | 100.24 ± 16.22 | 100.48 ± 13.49 | 0.001* | 97.27 ± 15.011 | 100.48 ± 13.49 | 0.824 |

*P < 0.05 - Statistically significant. BD, Buzzy Device; CS, Counter Stimulation; LA, Local Anesthetics; SD, Standard Deviation.

Table 5. Intra-group comparison among mean values of pulse rate (before versus during), (during versus after), and (before versus after) local anesthesia administration < 7 years and > 7 years.

| Group | Pulse (Before) | Pulse (During) | P-value | Pulse (During) | Pulse (After) | P-value | Pulse (Before) | Pulse (After) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | Mean ± SD | |||||

| < 7 years | BD | 5.12 ± 1.39 | 2.50 ± 1.30 | 0.448 | 2.50 ± 1.30 | 1.92 ± 1.19 | < 0.001** | 5.12 ± 1.39 | 1.92 ± 1.19 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 4.85 ± 1.48 | 5.38 ± 1.49 | 5.38 ± 1.49 | 5.04 ± 1.03 | 4.85 ± 1.48 | 5.04 ± 1.03 | ||||

| > 7 years | BD | 4.63 ± 1.52 | 2.17 ± 1.49 | 0.924 | 2.17 ± 1.49 | 1.63 ± 1.34 | < 0.001** | 4.63 ± 1.52 | 1.63 ± 1.34 | < 0.001** |

| CS | 4.71 ± 1.70 | 4.67 ± 1.71 | 4.67 ± 1.71 | 4.79 ± 1.93 | 4.71 ± 1.70 | 4.79 ± 1.93 | ||||

*P < 0.05 - Statistically significant. BD, Buzzy Device; CS, Counter Stimulation; SD, Standard Deviation.

DISCUSSION

Pain is a subjective experience that includes fear, anxiety, trust, personality, and sense of control over an unpleasant stimulus. The American Dental Association (ADA) states that fear of pain is the most important factor preventing individuals from visiting dentists. Inadequate pain management is a significant factor in the development of dental fear and anxiety [21]. Dental anxiety is a multidimensional model with social, conscious, and physiological components; using a single parameter to assess this type of anxiety may not provide an accurate result [22]. Therefore, a combination of three subjective scales (WBFPS, VAS, and VPT), one objective scale (VCARS), and a physiologic parameter (pulse rate) were employed in the study to measure pain and anxiety levels in children.

The self-report assessment of pain enables an immediate emotional response to dental treatment; it depends on verbal communication with children [23]. During dental treatment, WBFPS and VAS used in the present trial proved highly subtle for the subjective evaluation of pain among children [24]. In this study, anxiety was evaluated using VCARS and VPT. VCARS is a six-point rating scale that measures a child's situational anxiety. VPT is a reliable measure of self-reporting anxiety in children. Increased pulse rate during dental treatments was attributed to stressful conditions; its measurement using a pulse oximeter is helpful because it directly assesses physiological arousal [25].

The present study included 100 children (50 boys and girls), with equal allocation into both groups. Children without any prior experience with LA administration were selected, as evidenced by the fact that the injection order influenced LA pain perception [26]. According to the Frankl Behavior Rating Scale, cooperative children who fell under positive and negative categories were included in this study to avoid age-related uncooperative responses, which tend to misconstrue pain ratings. These children do not show immature, weeping, and whining behaviors towards the dentist, and follow the dentist's directions during the procedure. Children aged 4–11 years were recruited in this study because it has been suggested that cognitive development begins in this age group [27].

The Buzzy® device and counter-stimulation methods were employed in the current study to relieve pain and anxiety associated with LA administration during pulp therapy and extraction. The results showed a significant decrease in anxiety levels in both groups, with a higher percentage in the BD group. Children in the BD group experienced less pain than those in the CS group when measured using the WBFPS and VAS. Aminabadi et al. (2008) juxtaposed counter-stimulation in combination with verbal distraction to counterstimulation alone and the conventional LA administration method in 5-year-old children [16]. They reported that children who received CS and verbal distraction had less pain perception. In contrast, our study found no significant decrease in the pulse rates among the CS group during and after LA delivery; however, anxiety levels with VPT and VCARS were also not statistically significant.

We found an increase in the postoperative anxiety scores in the CS group, as compared to the preoperative anxiety scores. The mean pain scores calculated with VAS and WBFPS in the BD group were less than those in the CS group; the values were statistically significant. These findings were similar to those of Nunna et al., where VCARS and WBFPS scores were not statistically significant in the CS group, as compared to the VR group [28].

Bilsin and colleagues reported that Buzzy® device distraction is superior in controlling pain in children undergoing LA procedures [29]. Corresponding to these results, we perceived a significant decrease in mean heart rates in children who received LA injections while using the same method. The Buzzy® device's ice wings play an influential role in soothing the pain perceived by the children during LA administration. Ghaderi et al. placed an ice stick to the injection site for 1 min prior to local anesthesia; they found that this application considerably decreased pain related to LA administration [11]. Correspondingly, many researchers have stated that the application of cold stimuli on the injection area before LA administration substantially soothes children's agony during injections. Chilamakuri et al. stated that precooling the injection site with a pencil of ice was more effective than topical anesthesia [30]. Furthermore, Kosaraju and Vandewalle reported lower pain scores in the cold refrigerant group than in the gel group in decreasing pain during LA administration [31]. Aminah et al. concluded that pre-cooling the injection site before the administration of LA significantly reduced pain, as compared with buffered and local anesthesia [32]. In the present study, the mean values of WBFPS were lower in the BD group than in the CS group. The pain-related effect of the injection was significantly influential in the application of external cooling and vibration.

Dak-Albab et al. employed a vibrating dental device, Dental Vibe (Injection Comfort System), on children and reported that vibration was a practical and more accessible method than gels in decreasing pain related to dental injections [33]. Similarly, Shaefer et al. and Nanitsos et al. reported that vibrating devices effectively reduced pain during LA with a dental visit device and vibrating massager, respectively [34,35]. Our results are similar to those of a randomized trial by Alanazi et al. 2019 [36], except for the number of children (n = 60) and the age group (6–7 years). In both trials, children who employed the Buzzy® device distraction had a lower self-reported measure of pain during LA administration. In agreement with this, Suohu et al. (2020) and Bilsin et al. (2020) reported that pain at the injection site was significantly decreased when vibration and external cooling were used on local anesthetic sites during dental treatment in children [37,29].

In this prospective clinical trial, physiological assessment with a pulse oximeter displayed an accurate positive correlation between mean scores determined before, during, and after distraction with the Buzzy® device, suggesting that the use of external cold and vibrating devices significantly decreased needleassociated pain in children. These findings are consistent with studies performed on other vibrating devices that do not require external cooling [8]. In contrast, Suohu et al. observed no statistically significant difference in the pulse rates of Buzzy® and control groups [37].

To date, some randomized controlled trials have evaluated the effectiveness of external vibrating devices and site pre-cooling on pain control in children undergoing injection procedures in various dental and medical settings. Recently, a systematic review and meta-analysis by Ballard et al. (2019) stated that the Buzzy® device appears to be a promising technique for procedural pain management in children [38]. Another positive finding observed in the present study is that the majority of the children in the BD group intended to play with the device throughout the treatment, as it provided distraction from the sound and sight of dental instruments. However, the small sample size could be a possible limitation of the current study. Based on the study's observations, we rejected the null hypothesis by stating that the Buzzy® device and the counter-stimulation method reduced pain and dental anxiety in children during LA administration.

In conclusion, within the limitations of the contemporary study, Buzzy® device distraction is a valuable behavior guidance modality in diminishing dental anxiety and fear in children undergoing LA administration, as compared to counter-stimulation. The Buzzy® device is cost-effective, optimized, and easily available compared to other recently used LA devices and can be an additional armamentarium in pediatric dentistry.

Footnotes

DECLARATION OF INTEREST: The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

- Varada Sahithi: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing — original draft.

- Kanamarlapudi Venkata Saikiran: Conceptualization, Formal analysis, Writing — original draft, Writing — review & editing.

- Mahesh Nunna: Formal analysis, Writing — review & editing.

- Sainath Reddy Elicherla: Methodology, Supervision, Writing — review & editing.

- Ramasubba Reddy Challa: Methodology, Supervision, Validation,Writing — review & editing.

- Sivakumar Nuvvula: Conceptualization, Methodology, Supervision, Validation, Writing — review & editing.

References

- 1.Merskey H. Pain terms: a list with definitions and notes on usage. Recommended by the IASP Subcommittee on Taxonomy. Pain. 1979;6:249. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Uman LS, Chambers CT, McGrath PJ, Kisely S. A systematic review of randomized controlled trials examining psychological interventions for needle-related procedural pain and distress in children and adolescents: an abbreviated Cochrane review. J Pediatr Psychol. 2008;33:842–854. doi: 10.1093/jpepsy/jsn031. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bienvenu OJ, Eaton WW. The epidemiology of blood-injection-injury phobia. Psychol Med. 1998;28:1129–1136. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798007144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Okawa K, Ichinohe T, Kaneko Y. Anxiety may enhance pain during dental treatment. Bull Tokyo Dent Coll. 2005;46:51–58. doi: 10.2209/tdcpublication.46.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Carrillo-Diaz M, Crego A, Armfield JM, Romero-Maroto M. Assessing the relative efficacy of cognitive and non-cognitive factors as predictors of dental anxiety. Eur J Oral Sci. 2012;120:82–88. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0722.2011.00924.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hmud R, Walsh LJ. Dental anxiety: causes, complications and management approaches. J Minim Interv Dent. 2009;2:67–78. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Allen KD, Stanley RT, McPherson K. Evaluation of behaviour management technology dissemination in pediatric dentistry. Pediatr Dent. 1990;12:79–82. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shilpapriya M, Jayanthi M, Reddy VN, Sakthivel R, Selvaraju G, Vijayakumar P. Effectiveness of new vibration delivery system on pain associated with injection of local anesthesia in children. J Indian Soc Pedod Prev Dent. 2015;33:173–176. doi: 10.4103/0970-4388.160343. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Avisa P, Kamatham R, Vanjari K, Nuvvula S. Effectiveness of acupressure on dental anxiety in children. Pediatr Dent. 2018;40:177–183. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dedeepya P, Nuvvula S, Kamatham R, Nirmala SV. Behavioural and physiological outcomes of biofeedback therapy on dental anxiety of children undergoing restorations: a randomised controlled trial. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2014;15:97–103. doi: 10.1007/s40368-013-0070-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ghaderi F, Banakar S, Rostami S. Effect of pre-cooling injection site on pain perception in pediatric dentistry: “a randomized clinical trial”. Dent Res J (Isfahan) 2013;10:790–794. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Harbert H. Topical ice: a precursor to palatal injections. J Endod. 1989;15:27–28. doi: 10.1016/S0099-2399(89)80094-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Canbulat Şahiner N, İnal S, Sevim Akbay A. The effect of combined stimulation of external cold and vibration during immunization on pain and anxiety levels in children. J Perianesth Nurs. 2015;30:228–235. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Baxter AL, Lawson ML. Methodological concerns comparing buzzy to transilluminator device. Indian J Clin Biochem. 2014;29:114–115. doi: 10.1007/s12291-013-0370-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Nuvvula S, Alahari S, Kamatham R, Challa RR. Effect of audiovisual distraction with 3D video glasses on dental anxiety of children experiencing administration of local analgesia: a randomised clinical trial. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2015;16:43–50. doi: 10.1007/s40368-014-0145-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Aminabadi NA, Farahani RM, Balayi Gajan E. The efficacy of distraction and counterstimulation in the reduction of pain reaction to intraoral injection by pediatric patients. J Contemp Dent Pract. 2008;9:33–40. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wong DL, Baker CM. Pain in children: comparison of assessment scales. Pediatr Nurs. 1988;14:9–17. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Powell CV, Kelly AM, Williams A. Determining the minimum clinically significant difference in visual analog pain score for children. Ann Emerg Med. 2001;37:28–31. doi: 10.1067/mem.2001.111517. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Venham LL, Gaulin-Kremer E. A self-report measure of situational anxiety for young children. Pediatr Dent. 1979;1:91–96. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Venham LL, Gaulin-Kremer E, Munster E, Bengston-Audia D, Cohan J. Interval rating scales for children's dental anxiety and uncooperative behavior. Pediatr Dent. 1980;2:195–202. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Yesilyurt C, Bulut G, Tasdemir T. Pain perception during inferior alveolar injection administered with the Wand or conventional syringe. Br Dent J. 2008;205:258–259. doi: 10.1038/sj.bdj.2008.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Aartman IH, van Everdingen T, Hoogstraten J, Schuurs AH. Self-report measurements of dental anxiety and fear in children: a critical assessment. ASDC J Dent Child. 1998;65:252–258. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Srouji R, Ratnapalan S, Schneeweiss S. Pain in children: Assessment and non-pharmacological management. Int J Pediatr. 2010;2010:474838. doi: 10.1155/2010/474838. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ohnhaus EE, Alder R. Methodological problems in the measurement of pain: a comparison between the verbal rating scale and the visual analogue scale. Pain. 1975;1:379–384. doi: 10.1016/0304-3959(75)90075-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fakhruddin KS, Gorduysus MO, El Batawi H. Effectiveness of behavioral modification techniques with visual distraction using intrasulcular local anesthesia in hearing disabled children during pulp therapy. Eur J Dent. 2016;10:551–555. doi: 10.4103/1305-7456.195159. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Martin MD, Ramsay DS, Whitney C, Fiset L, Weinstein P. Topical anesthesia: differentiating the pharmacological and psychological contributions to efficacy. Anesth Prog. 1994;41:40–47. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pani SC, AlAnazi GS, AlBaragash A, AlMosaihel M. Objective assessment of the influence of the parental presence on the fear and behavior of anxious children during their first restorative dental visit. J Int Soc Prev Community Dent. 2016;6:148–152. doi: 10.4103/2231-0762.189750. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Nunna M, Dasaraju RK, Kamatham R, Mallineni SK, Nuvvula S. Comparative evaluation of virtual reality distraction and counterstimulation on dental anxiety and pain perception in children. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2019;19:277–288. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2019.19.5.277. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Bilsin E, Güngörmüş Z, Güngörmüş M. The efficacy of external cooling and vibration on decreasing the pain of local anesthesia injections during dental treatment in children: a randomized controlled study. J Perianesth Nurs. 2020;35:44–47. doi: 10.1016/j.jopan.2019.06.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Chilakamuri S, Svsg N, Nuvvula S. The effect of pre-cooling versus topical anesthesia on pain perception during palatal injections in children aged 7-9 years: a randomized split-mouth crossover clinical trial. J Dent Anesth Pain Med. 2020;20:377–386. doi: 10.17245/jdapm.2020.20.6.377. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kosaraju A, Vandewalle KS. A comparison of a refrigerant and a topical anesthetic gel as preinjection anesthetics: a clinical evaluation. J Am Dent Assoc. 2009;140:68–72. doi: 10.14219/jada.archive.2009.0020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Aminah M, Nagar P, Singh P, Bharti M. Comparison of topical anesthetic gel, pre-cooling, vibration and buffered local anaesthesia on the pain perception of pediatric patients during the administration of local anaesthesia in routine dental procedures. Int J Contemp Med Res. 2017;4:400–403. [Google Scholar]

- 33.Dak-Albab R, Al-Monaqel MB, Koshha R, Shakhashero H, Soudan R. A comparison between the effectiveness of vibration with Dental vibe and benzocaine gel in relieving pain associated with mandibular injection: a randomized clinical trial. Anaesth Pain Intensive Care. 2019;23:43–49. [Google Scholar]

- 34.Shaefer JR, Lee SJ, Anderson NK. A vibration device to control injection discomfort. Compend Contin Educ Dent. 2017;38:5–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Nanitsos E, Vartuli R, Forte A, Dennison PJ, Peck CC. The effect of vibration on pain during local anaesthesia injections. Aust Dent J. 2009;54:94–100. doi: 10.1111/j.1834-7819.2009.01100.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Alanazi KJ, Pani S, Al-Ghanim N. Efficacy of external cold and a vibrating device in reducing discomfort of dental injections in children: a split-mouth randomised crossover study. Eur Arch Paediatr Dent. 2019;20:79–84. doi: 10.1007/s40368-018-0399-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Suohu T, Sharma S, Marwah N, Mishra P. A comparative evaluation of pain perception and comfort of a patient using conventional syringe and Buzzy system. Int J Clin Pediatr Dent. 2020;13:27–30. doi: 10.5005/jp-journals-10005-1731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Ballard A, Khadra C, Adler S, Doyon-Trottier E, Le May S. Efficacy of the Buzzy® device for pain management of children during needle-related procedures: a systematic review protocol. Syst Rev. 2018;7:78. doi: 10.1186/s13643-018-0738-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]