Abstract

Purpose: The aim of this study was to assess the exposure to and impact of the It's Never Just HIV mass media campaign aimed at HIV negative men who have sex with men (MSM) in New York City.

Methods: Questions about the campaign were included in the local questionnaire of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-sponsored National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) study of MSM in NYC conducted in 2011. Participants in this cross-sectional study were recruited using venue-based sampling.

Results: Among 447 NYC National HIV Behavioral Surveillance study participants who self-reported HIV negative or unknown status and answered questions about the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene's It's Never Just HIV campaign, more than one-third (n = 173, 38.7%) reported having seen the campaign. Latinos (34.8%) and blacks (34.4%) were less likely to report seeing the campaign compared to whites (47.7%). Most of those who reported seeing the campaign saw it on the subway (80.1%). Only 9.4% of those who saw the campaign reported having changed their sexual or health behaviors in response to the campaign.

Conclusions: These data suggest that thousands of HIV-uninfected MSM in NYC have been reached by the campaign and recalled its message.

Key words: : health behavior, health communications, health promotion, HIV/AIDS, men who have sex with men (MSM)

Introduction

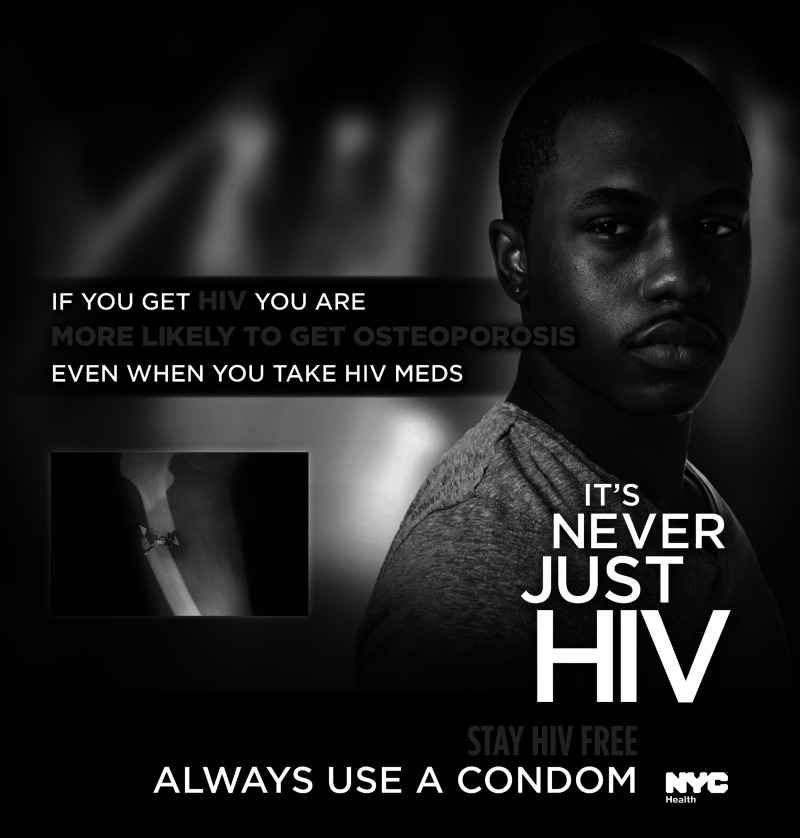

Mass media outreach to populations at highest risk for HIV infection has the potential to be one of the more cost-effective means of HIV prevention in the United States.1 Men who have sex with men (MSM) comprise the greatest number of new and prevalent HIV diagnoses in New York City.2 In 2013, most new HIV diagnoses among males in NYC were among MSM (71%); excluding cases with unknown risk, the proportion rises to 90%.3 From December 2010 to May 2011, the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) conducted the It's Never Just HIV media campaign, which focused on reaching NYC's estimated 105,000 MSM.4 The campaign emphasized comorbid medical conditions for which individuals diagnosed with HIV are at increased risk even among those who adhere to antiretroviral therapy, including anal cancer, osteoporosis, and dementia. This content was chosen to underscore the campaign's core messages to “Stay HIV Free” and “Always Use a Condom.” The campaign consisted of 30-second video spots posted on YouTube and on television. The YouTube link was included in a press release that was distributed via the DOHMH.5 Television spots ran primarily during gay-friendly programming on networks popular among gay and bisexual men in NYC, including Logo, the Travel Channel, the Style Network, and Bravo, as well as NBC, the Discovery Channel, the Food Network, and Comedy Central. Nearly 2,000 television spots ran from December 2010 through January 2011. Images from the campaign also were deployed as English and Spanish print advertisements (“subway squares”) displayed in the interior of 20% of all NYC subway cars (Figure 1). Online banner ads were also displayed on websites estimated to have high visibility among gay men in NYC, and companion educational brochures were distributed through community groups and service organizations. The campaign's video spots quickly drew notice and comment from multiple well-known bloggers. Links to the YouTube video were distributed widely among internet users, and, in the 53 months following release, the video was viewed 165,987 times.5,6

FIG. 1.

Example of It's Never Just HIV “subway square.” (Image courtesy of NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene.)

Materials and Methods

To help assess exposure to and the impact of the campaign among its core intended audience (HIV-negative MSM in NYC), we included questions about the campaign in the local questionnaire of the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC)-sponsored National HIV Behavioral Surveillance (NHBS) study of MSM in NYC conducted during 2011. NHBS is an ongoing national, cross-sectional study sponsored by the CDC that monitors HIV risk behaviors, testing history, exposure to and use of HIV prevention services, and HIV prevalence among MSM, injection drug users (IDU), and high-risk heterosexuals in three-year cycles.7,8 In the MSM cycle of NHBS, the methods of which are described in detail elsewhere,9 participants were selected using venue-based sampling (VBS) of designated NYC MSM venues (bars, clubs, parks, etc.). There were 54 recruitment events conducted over 15 weeks from July through October 2011. At each recruitment event, field staff operating in a mobile van outside the venue enumerated all adult men who entered the venue (or crossed an imaginary line when no venue entrance existed). Enumerated men were sequentially and non-preferentially approached by interviewers who described the study to them, and interested men were screened for eligibility. Eligible men who provided their verbal informed consent were given a structured survey interview administered privately by trained interviewers and a voluntary HIV test. The eligibility criteria were male, ≥18 years of age, NYC residence, and English or Spanish comprehension. MSM sexual history was not an eligibility criterion, but men who did not report having anal or oral sex with a man in the past 12 months were excluded from this analysis. Those who reported that they were HIV positive, including those first identified positive in the last 12 months, were also eliminated from this analysis since the It's Never Just HIV campaign targeted HIV negative men. All study procedures involving human subjects were approved by the NYC DOHMH and John Jay College of Criminal Justice Institutional Review Boards. Participants were shown an image from the campaign and asked, “Have you ever seen this message as a commercial, poster, pamphlet or video?” Those who had seen the campaign were asked, “Did you make any changes in your sexual or health behaviors in response to this advertisement?”

Statistical analyses

Means and standard deviations (for normal continuous data), medians and interquartile ranges (IQR) (for non-normal continuous data), and the frequencies and percentages for each level of categorical variables were calculated. Associations between having seen the campaign and reported behavior change among those who had seen the campaign and selected categorical variables were examined through the estimation of prevalence ratios (PR) and 95% confidence intervals (CI) using log-binomial general linear regression models; significant differences between non-normal continuous variables were determined using Wilcoxon signed-rank tests. All analyses were conducted using SAS 9.2 (Cary, NC, USA).

Results

There were 447 NHBS participants who reported HIV-negative or unknown status and answered questions about the campaign. More than one-third (n = 173, 38.7%) of these participants reported having seen the campaign (Table 1). Latinos (34.8%) and blacks (34.4%) were less likely to report seeing the campaign compared to whites (47.7%) (P = .02 and P = .05, respectively). There were no significant differences in age, birthplace, sexual identity, education, or condom use at last sex among participants who had seen the campaign. Those who reported seeing the campaign saw it on the subway (80.1%), on the internet (12.9%), on television (12.9%), in a pamphlet (1.8%), and in other media (11.1%). Blacks and Latinos were less likely to report having seen the campaign on the subway compared to whites (P = .006 and P = .001, respectively); there was no significant difference in race or ethnicity for having seen the campaign for all other media. Of those who had seen the campaign, 16 (9.4%) reported having changed their sexual or health behaviors in response to the campaign (Table 2). Blacks were more likely to have reported behavior change compared to whites (22.6% vs. 6.3% (P = .03), but there were no other significant differences in reported behavior change by age, birthplace, sexual identity, education, or condom use at last sex among those who reported seeing the campaign. The majority of those who saw the campaign (78.4%) saw it at least 10 times, 9.4% saw it 5–9 times, and 12.3% saw it 1–4 times; there was no significant difference in condom use at last sex by the number of times participants reported seeing the campaign (Wilcoxon, P = .19). There was also no difference in the number of times participants reported having seen the campaign for those who reported behavior change (median: 6.5 times, IQR: 3, 10) compared with those who reported that they did not change their behavior in response to the campaign (median: 7 times, IQR: 4, 10) (Wilcoxon, P = .38). There was no difference in the time between the last date of the campaign (January 2011) and the date of the interview for those who reported seeing the campaign compared with those who reported that they did not see the campaign (median: 7 months, IQR: 6, 8 for both groups) (Wilcoxon, P = .46).

Table 1.

Exposure to It's Never Just HIV Campaign (Self-Report Negative/Unknown HIV Status, n = 447)

| Total n | Total column % | Saw campaign n | Saw campaign row % | PR (95% CI) | P-value | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 447 | 100.0 | 173 | 38.7 | ||

| Race | ||||||

| White | 132 | 29.7 | 63 | 47.7 | 1.0 | — |

| Black | 93 | 20.9 | 32 | 34.4 | 0.7 (0.5, 1.0) | .05 |

| Latino | 181 | 40.7 | 63 | 34.8 | 0.7 (0.6, 1.0) | .02 |

| Other | 39 | 8.8 | 14 | 35.9 | 0.8 (0.5, 1.2) | .22 |

| Age | ||||||

| 18–29 | 243 | 54.4 | 95 | 39.1 | 1.0 | — |

| 30–39 | 98 | 21.9 | 36 | 36.7 | 0.9 (0.7, 1.3) | .69 |

| 40–49 | 76 | 17.0 | 30 | 39.5 | 1.0 (0.7, 1.4) | .95 |

| 50+ | 30 | 6.7 | 12 | 40.0 | 1.0 (0.6, 1.6) | .92 |

| Birthplace | ||||||

| United States | 361 | 80.8 | 138 | 38.2 | 1.0 | — |

| Foreign born | 86 | 19.2 | 35 | 40.7 | 1.1 (0.8, 1.4) | .67 |

| Sexual Identity | ||||||

| Gay | 344 | 77.1 | 132 | 38.4 | 1.0 | — |

| Bisexual | 92 | 20.6 | 37 | 40.2 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.4) | .74 |

| Straight | 10 | 2.2 | 3 | 30.0 | 0.8 (0.3, 2.0) | .61 |

| Education | ||||||

| Completed college | 116 | 26.0 | 51 | 44.0 | 1.2 (0.9, 1.5) | .17 |

| Did not complete college | 331 | 74.0 | 122 | 36.9 | 1.0 | — |

| Condom Use at Last Sex | ||||||

| Yes | 306 | 68.5 | 118 | 38.6 | 1.0 (0.8, 1.3) | .93 |

| No | 141 | 31.5 | 55 | 39.0 | 1.0 | — |

Numbers may not equal sample total due to missing data.

PR, prevalence ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Table 2.

Reported Behavior Change After Exposure to It's Never Just HIV Campaign (Self-Report Negative/Unknown HIV Status, n = 171)

| n (row%) | PR (95% CI) | |

|---|---|---|

| Race | ||

| White | 4 (6.3) | 1.0 |

| Black | 7 (22.6) | 3.6 (1.1, 11.2) |

| Latino | 3 (4.8) | 0.8 (0.2, 3.3) |

| Other | 2 (14.3) | 2.2 (0.5, 11.1) |

| Age | ||

| 18–29 | 9 (9.6) | 1.0 |

| 30–39 | 4 (11.1) | 1.2 (0.4, 3.5) |

| 40–49 | 2 (6.9) | 0.7 (0.2, 3.1) |

| 50+ | 1 (8.3) | 0.9 (0.1, 6.3) |

| Birthplace | ||

| United States | 13 (9.6) | 1.0 |

| Foreign born | 3 (8.6) | 0.9 (0.3, 3.0) |

| Sexual Identity | ||

| Gay | 12 (9.2) | 1.0 |

| Bisexual | 4 (11.1) | 1.2 (0.4, 3.5) |

| Straight | 0 (0.0) | — |

| Education | ||

| Completed college | 3 (5.9) | 0.5 (0.2, 1.8) |

| Did not complete college | 13 (10.8) | 1.0 |

| Condom Use at Last Sex | ||

| Yes | 12 (10.3) | 1.4 (0.5, 4.2) |

| No | 4 (7.3) | 1.0 |

Discussion

Given the proportion of the study sample that reported exposure to the campaign, these data suggest that thousands of HIV-uninfected MSM in NYC may have been reached by It's Never Just HIV and recalled its message. Based on the estimated number of 105,000 MSM in NYC4 and the percentage of NHBS participants exposed to the campaign (38.7%), we estimate that 40,635 MSM in NYC were exposed to the campaign. The campaign was conducted for $800,000, which is approximately $20 per MSM estimated to have been exposed to the campaign. If 9.4% of those who saw the campaign changed their sexual or health behavior, it is estimated that more than 3800 MSM in NYC changed their behavior to prevent HIV infection in response to the campaign. Media durability of the campaign has been buoyed by controversy sparked from the potential impact (both positive and negative) of a campaign emphasizing the negative consequences of HIV infection.10

Limitations

The results of this study may underestimate the effect of the It's Never Just HIV campaign, if those who were exposed to the campaign, but did not recall having seen the campaign during the study interview, changed their behavior after unconsciously processing the information in the advertisement.11 This study did not measure exposure to other HIV prevention media campaigns or HIV prevention programming; the combined effect from exposure to multiple media campaigns and/or HIV prevention programming likely has a greater effect on behavior change than change from exposure to a single source. In addition, behavior change was based on self-report and participants may have provided socially desirable responses. The limited sample size may also have restricted the power to detect differences within the target population. Efforts were made to include a diverse selection of MSM venues in the sampling universe, however, MSM that do not attend these venues would not have had the opportunity to participate in this study and this study's findings may not be generalizable to all MSM in NYC or other MSM populations. The majority of participants who saw the campaign (80.1%) reported having seen the campaign on subways, which suggests that subway-advertising placement was a particularly successful dissemination strategy. Prioritizing subway lines (i.e., selecting only lines that travelled through high prevalence neighborhoods) was not possible, as cars are rotated throughout the entire subway system. Differences in the race and ethnicity of MSM who saw the campaign in the subway may be explained by current subway ridership demographics.12 Because of NHBS's cross-sectional design it was not possible to use these data to measure the long-term sustainability of the campaign's message. Also unknown is the extent to which the diffusion of this message was associated with an increase in condom use by HIV negative MSM in NYC. Research on the effectiveness of fear appeal campaigns is inconclusive13 and cognitive antecedents of behavior change (self-efficacy, attitude, subjective norm, and anticipated regret) and the level of risk behaviors prior to media campaign exposure may mediate the effect of fear-based campaigns.14

Conclusion

These data suggest that thousands of HIV-uninfected MSM in NYC were reached by the campaign and recalled its message. Further research should investigate how future HIV prevention campaigns can achieve more widespread coverage and effectiveness among MSM.

Acknowledgments

This research was funded by a cooperative agreement between the NYC Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (NYC DOHMH) and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) (Grant# 1U1BPS003246-01). All study procedures involving human subjects were approved by the New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene (DOHMH) and John Jay College of Criminal Justice Institutional Review Boards. The contents of this article are solely the responsibility of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official views of the CDC. The authors acknowledge Gabriela Paz-Bailey, Dita Broz, and Isa Miles of CDC for their contributions to the NHBS study design; the NYC DOHMH HIV Prevention Program, specifically Adriana Andaluz, Nana Mensah, and Kara O'Brien, and the NYC DOHMH Health Media and Marketing Team for their leadership in the creation, implementation, and evaluation of the It's Never Just HIV campaign; Kent Sepkowitz, Jay Varma, and Deborah Dowell of the NYC DOHMH for reviewing previous drafts of this article; and the NYC NHBS field staff for all their efforts.

Author Disclosure Statement

No competing financial interests exist for any of the authors.

References

- 1.Cohen DA, Wu S-Y, Farley TA: Cost-effective allocation of government funds to prevent HIV infection. Health Aff (Millwood) 2005;24:915–926 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: HIV Surveillance Annual Report, 2012. 2013; Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/dires/surveillance-report-dec-2013.pdf Accessed January28, 2014

- 3.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: New York City HIV/AIDS Annual Surveillance Statistics 2013. 2015. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/downloads/pdf/ah/surveillance2013-table-all.pdf Accessed March9, 2015

- 4.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Community Health Survey 2011. Available at https://a816-healthpsi.nyc.gov/SASStoredProcess/guest?_PROGRAM=%2FEpiQuery%2FCHS%2Fchsindex&year=2011 Accessed April5, 2013

- 5.New York City Department of Health and Mental Hygiene: Health Department Takes Its Latest HIV Awareness Campaign to the Subway [Press Release]. 2011. Available at http://www.nyc.gov/html/doh/html/pr2011/pr002-11.shtml Accessed March6, 2013

- 6.NYC Health: It's Never Just HIV. 2010. Available at https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d0ANiu3YdJg Accessed May12, 2015

- 7.Gallagher KM, Sullivan PS, Lansky A, Onorato IM: Behavioral surveillance among people at risk for HIV infection in the US: The National HIV Behavioral Surveillance System. Public Health Rep 2007;122:32–38 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lansky A, Sullivan PS, Gallagher KM, Fleming PL: HIV behavioral surveillance in the US: A conceptual framework. Public Health Rep 2007;122:16–23 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Reilly KH, Neaigus A, Jenness SM, et al. : Factors associated with recent HIV testing among men who have sex with men in New York City. AIDS Behav 2014;18:297–304 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Hartocollis A: City's Graphic Ad on the Dangers of H.I.V. Is Dividing Activists. The New York Times January 4, 2011;A17 [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yoo CY: Unconscious processing of Web advertising: Effects on implicit memory, attitude toward the brand, and consideration set. J Interact Mark 2008;22:2–18 [Google Scholar]

- 12.Scarborough Research Corporation. Subway Rider Demographic Profile Report New York City (5-Boroughs), 2012

- 13.Witte K, Allen M: A meta-analysis of fear appeals: Implications for effective public health campaigns. Health Educ Behav 2000;27:591–615 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Smerecnik CM, Ruiter RA: Fear appeals in HIV prevention: The role of anticipated regret. Psychol Health Med 2010;15:550–559 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]