Abstract

Objective:

Lung cancer screening (LCS) efficacy is highly dependent on adherence to annual screening, but little is known about real-world adherence determinants. We used insurance claims data to examine associations between LCS annual adherence and demographic, comorbidity, healthcare usage, and geographic factors.

Materials and Methods:

Insurance claims data for all individuals with a LCS low dose CT scan was obtained from the Colorado All Payer Claims Dataset. Adherence was defined as a second claim for a screening CT 10-18 months after the index claim. Cox proportional hazards regression was used to define the relationship between annual adherence and age, sex, insurance type, residence location, outpatient healthcare usage, and comorbidity burden.

Results:

After exclusions, the final dataset consisted of 9,056 records with 3,072 adherent, 3,570 non-adherent, and 2,414 censored (unclassifiable) individuals. Less adherence was associated with ages 55-59 (hazard ratio (HR)=0.80, 99% confidence interval (CI)=0.67-0.94), 60-64 (HR=0.83, 99% CI=0.71-0.97) and 75-79 (HR=0.79, 99% CI=0.65-0.97), rural residence (HR=0.56, 99% CI=0.43-0.73), Medicare Fee-for-Service (HR=0.45, 99% CI=0.39-0.51), and Medicaid (HR=0.50, 99% CI=0.40-0.62). A significant interaction between outpatient healthcare usage and comorbidity was also observed. Increased outpatient usage was associated with increased adherence and was most pronounced for individuals without comorbidities.

Conclusions:

This population-based description of LCS adherence determinants provides insight into populations that might benefit from specific interventions targeted toward improving adherence and maximizing LCS benefit. Quantifying population-based adherence rates and understanding factors associated with annual adherence is critical to improving screening adherence and reducing lung cancer death.

Summary Sentence

Our findings that age, rural residence, insurance type, and health care use/comorbidity burden influence LCS adherence provides insight into populations that may benefit from interventions to improve adherence and maximize LCS benefit.

Introduction

Lung cancer is the leading cause of cancer death and kills more people than breast, colon, and prostate cancer combined (1). Lung cancer lethality is largely driven by the preponderance of metastatic disease at diagnosis. Most patients present with advanced disease and despite recent treatment advances, the 5-year survival of metastatic lung cancer remains under 10% (2). Though the 5-year survival of early stage lung cancer exceeds 55%, only 17% of patients present with localized disease (2). Lung cancer screening (LCS) by annual low dose computed tomography (LDCT) reduces lung cancer mortality by identifying surgically curable early stage disease (3, 4). The Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) recommend LCS for current and former smokers 55-77 years old with a ≥ 30 pack year smoking history who are still smoking or have quit within the last 15 years (5). Based on modeling data, the US Preventive Services Task Force recommends screening through age 80 (6) and recently released a draft recommendation to expand screening by lowering eligibility to 50 years of age and tobacco exposure to 20 pack years (7).

LCS efficacy is highly dependent on both screening uptake and adherence to annual screening. Uptake refers to the number of eligible people that have an (index or initial) screening LDCT, while annual adherence is the proportion of individuals that continue to receive subsequent interval screening LDCTs. In the National Lung Screening Trial (NLST), 58% of early stage lung cancers were detected on annual (as opposed to initial) LDCT, suggesting that a substantial fraction of the reduced lung cancer mortality was attributable to the >95% adherence to serial imaging in the trial (3). Similar stage I lung cancer detection (58%), reduced lung cancer mortality (25% at 10 years) and adherence to screening (90%) were recently reported in another large study (4). Microsimulation modeling predicts a halving of screening benefit when annual screening adherence falls below 50% (8). Similarly, stage shift from late to early stage disease is reduced as the screening interval is increased (9).

Determinants of cancer screening adherence are multifaceted and include both individual factors (demographics, income, beliefs) and health care system factors (insurance, accessibility, clinician recommendation) (10-21). Early reports of real-world screening cohorts describe LCS annual adherence rates outside clinical trials between 37 and 66% (22-27). Recent systemic reviews and meta-analyses found higher adherence in participants in their 60s and former (as opposed to current) smokers and lower adherence in racial minorities, individuals with less education, and individuals who lived further from the screening facility (20, 21). However, the quality of evidence supporting most of these associations was moderate or low and was largely derived from cohort studies performed in academic settings before the CMS decision to cover screening in the high-risk population defined by the NLST (20, 21). To this point, determinants of LCS adherence in a real-world, unselected United States population, outside of a study have not been described. We used a state-based, administrative claims dataset to quantify population level LCS adherence and identify demographic, comorbidity, healthcare usage, and geographic factors associated with adherence.

Materials and Methods

Data Source:

The Colorado All Payer Claims Dataset (CO APCD) was queried to identify all claims for LCS specific LDCT scans identified with procedural codes G0297 and S8032. The extracted dataset included all health claims with dates of service between 1/2012 and 12/2018, diagnosis or procedural codes, and associated demographic and insurance information available for these claims. CO APCD covers approximately 68% of insured lives in Colorado and captures data from >40 commercial (private insurance) payers, Medicare fee-for-service (FFS) (public insurance for Americans >65 years of age or individuals with a disability), Medicare Advantage (Medicare contracted through a private insurance company), and Medicaid (government assistance program for low income Americans regardless of age), CO APCD does not include data from the majority of self-funded health care plans regulated by the Employee Retirement Income Security Act or health care plans administered by the federal government (TriCare, Veterans Administration, Indian Health Service, Federal Employee Health Benefits). Within CO APCD, individuals are assigned a unique composite ID that provides continuity of claims across payer types. The study was reviewed by the Colorado Multiple Institutional Review Board and determined to be exempt for use of secondary data. Although the CO APCD dataset includes personal health information (dates associated with health claims), the study met criteria for a full waiver of HIPAA authorization.

Measures and definitions:

We defined annual adherence as a second claim for a screening LDCT 10-18 months after the index LDCT claim. This definition captures 87% of all returning individuals (22). Time (in months) between the index screening LDCT and any subsequent screening specific LDCTs was calculated using the dates of service associated with the LDCT claim. We classified individuals as adherent if there was a second screening LDCT claim within 10-18 months of the first claim and non-adherent if there was not a second LDCT claim and more than 18 months had elapsed since the first claim. Individuals with 10-18 months of follow-up time after the index LDCT and no second screening specific LDCT claim were censored as they could not be classified as adherent or non-adherent since incomplete time had passed to meet the definition of adherence. For the primary analysis, individuals who returned >18 months after the index LDCT were classified as non-adherent.

The eligible population included anyone 55-79 years old with at least one claim for a lung cancer screening LDCT. We excluded individuals with less than 10 months of follow-up after the index LDCT, individuals with a second LDCT claim 3-9 months after the index LDCT, individuals with a lung cancer diagnosis using International Classification of Disease (ICD) 9 and 10 codes, out-of-state residents, and individuals with missing statistical model data.

We assessed the following associations with LCS adherence: sex, age at index LDCT, residence (urban vs rural/frontier as designated by the Colorado Rural Health Center) at index LDCT, insurance type (commercial, Medicare FFS, Medicare Advantage, or Medicaid) linked with the index LDCT claim, health care utilization (defined by the number of outpatient visits excluding the LDCT in the 3.5 years before through 1.5 years after the index CT date), and comorbidity burden (by Charlson Comorbidity Index (CCI) score (28) based on clinician (SPM) review of ICD 9 and 10 codes found in the CO APCD and categorized as 0, 1, or ≥2). In calculating the CCI, we utilized any data available in the CO APCD and excluded non-melanoma skin cancers and HIV/AIDS as the CCI was validated in a period before effective antiretroviral therapy (29, 30).

Statistical Analysis:

Normal distribution of continuous variables was evaluated with quantile-quantile plots. Continuous variables were categorized and tested to determine if they showed a linear or nonlinear trend in the log hazard. Univariate differences between the three population groups were assessed with a χ2 test. Cox proportional hazards regression was performed to characterize the relationship between annual adherence and subject variables. Utilization of a cox proportional hazards regression accounted for the time element of our adherence definition and allowed for a prospective approach to the study. The proportional hazards assumption was tested with weighted Schoenfeld residuals and we utilized an alpha level of 0.01 for statistical significance of all hypothesis tests. The primary analysis focused on enumerating adherence rates and associations for adherence for only the first annual LDCT scan. We performed three sensitivity analyses: one assessing a 15-month definition of adherence, one defining any return for screening as adherent, and one excluding late returning (>18 month) individuals. We additionally calculated continued adherence rates to the second annual screening among individuals adherent to the first annual LDCT. Data analysis was generated using SAS/STAT software, Version 9.4 of the SAS System for Windows (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Results

There were 27,332 claims for LCS LDCT between 10/1/2014 and 12/31/2018 (Fig. 1). Second LDCT claims within 2 months were assumed to be duplicate claims; removing these claims left 19,416 unique LDCT claims for 14,563 individuals. We excluded 4,530 individuals with <10 months of follow-up time after the index LDCT claim as insufficient time had elapsed for determination of annual adherence. We excluded individuals with second LDCT claims between 3-9 months as these were assumed to be diagnostic (not screening) studies; a distribution of times from index to second LDCT claims is shown in Fig. 2. We excluded individuals <55 or >79 years of age and individuals with a lung cancer diagnosis (ICD 9 or 10 codes (1623, 1624, 1625, 1628, 1629, C341, C343, C349) as screening is not recommended in these individuals. After excluding non-Colorado residents and records with missing subject variable data, we had a final dataset of 9,056 records with 3,072 adherent individuals, 3,570 non-adherent individuals, and 2,414 individuals who were censored because they could not be accurately classified with <18 months of follow-up time.

Figure 1. Study cohort.

Study population was derived as described in the text. Four individuals had multiple exclusion criteria. Censored individuals had 10-18 months of follow-up since index CT but no claim for a second LDCT and hence could not be classified as adherent or non-adherent. The duplicate claims are explained by the procedure (LDCT) and professional fee (radiology interpretation) being billed separately to insurance.

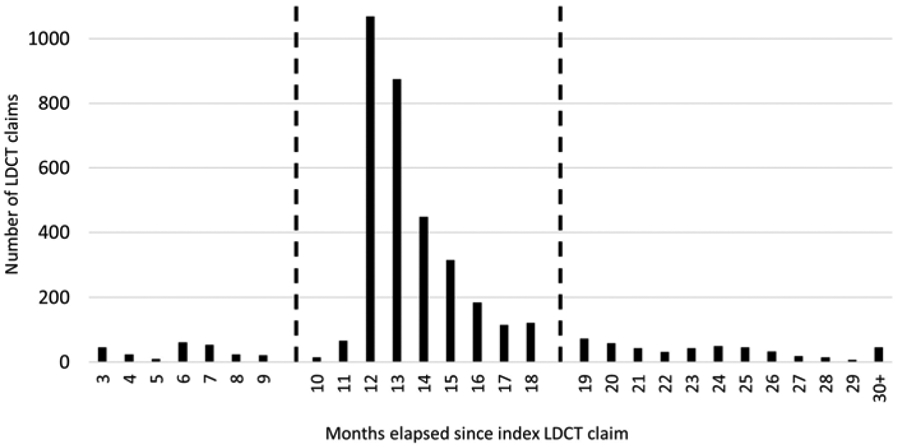

Figure 2. Time between index and second LDCT.

Defining adherence as having a second LDCT 10-18 months after the index CT scan captures 87% of returning individuals. Claims 3-9 months after the index LDCT were assumed to be diagnostic studies for monitoring pulmonary nodules.

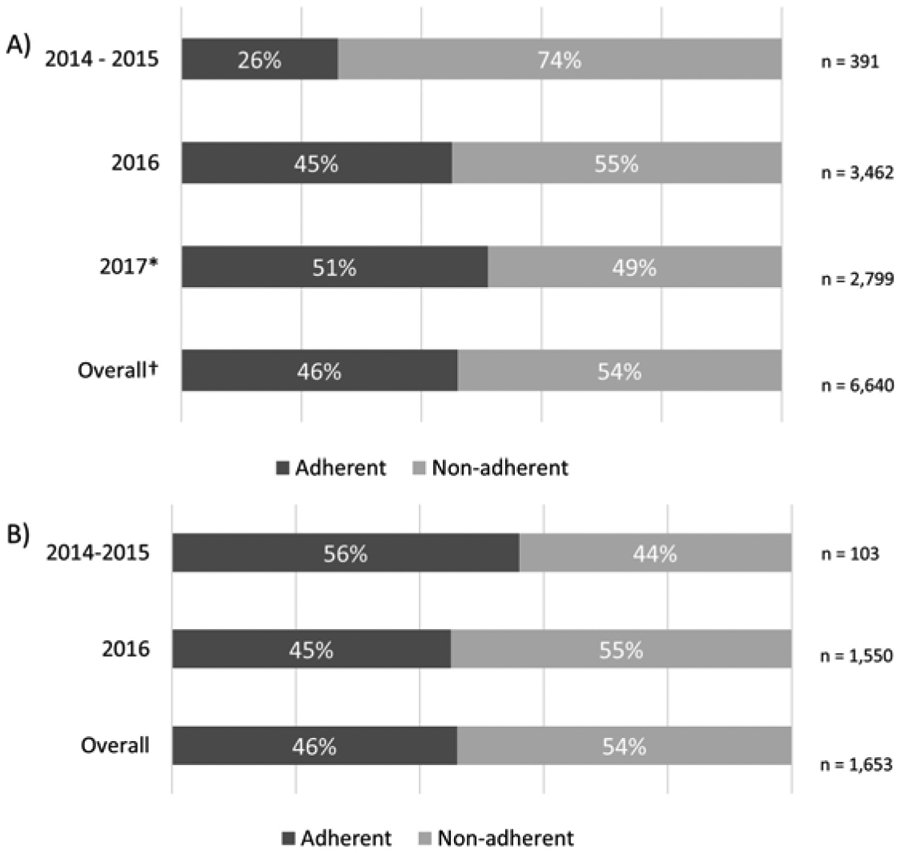

Overall adherence in this cohort using an 18-month definition was 46%; this increased to 53% if any return for screening was considered adherent. Adherence to the first annual LDCT increased over the duration of this study (p = 0.0009) (Fig. 3A). Of individuals who were adherent to the first round of screening, adherence to the second annual LDCT was approximately 50% (Fig. 3B); due to data maturity, adherence to additional screening rounds could not be assessed.

Figure 3. Screening adherence by year of index LDCT.

(A) Adherence to first annual LDCT by year of index claim. *For 2017, individuals who could not be classified due to data maturity are not included. †Overall numbers do not include unclassifiable individuals screened in 2017 or any individuals screened in 2018. (B) Adherence to the second annual LDCT by year of index claim. Only individuals who were adherent to the first annual screening are included.

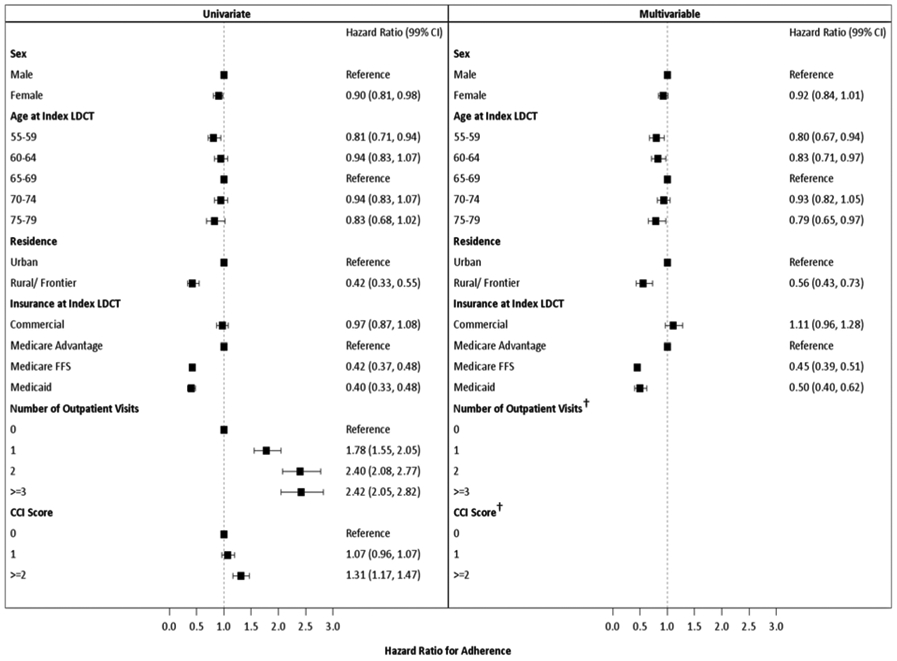

Characteristics of the study population are presented in Table 1. The adherent group had more males (p = 0.003), individuals aged 65-69 (p = 0.01), urban residents (p < 0.0001), individuals with commercial or Medicare Advantage insurance (p < 0.0001), outpatient visits (p < 0.0001), and comorbidities (p < 0.0001). After adjustment for covariates, age, residence, and insurance were significantly associated with annual lung cancer screening adherence (Fig. 4). Compared to individuals aged 65-69, individuals 55-64, and 75-79 had a 20% reduction in adherence. Individuals with a rural residence had a 44% reduction in adherence compared to urban residents, and individuals with Medicare FFS and Medicaid had a 45% reduction in adherence when compared to individuals with Medicare Advantage.

Table 1. Characteristics of study population.

Over half of the study population had unknown or missing race and ethnicity data, making this variable unusable for regression analysis. The adherent group has a higher proportion of missing data because >95% of missing data is from Medicare Advantage and commercial payers, which comprise a higher percentage of the adherent group. Data are presented as count (%). Definition of abbreviations: LDCT = low dose computed tomography, FFS = fee-for-service, CCI = Charlson Comorbidity Index.

| Adherent n = 3,072 |

Non-adherent n = 3,570 |

Censored n = 2,414 |

|

|---|---|---|---|

| Sex | |||

| Male | 1694 (55) | 1847 (52) | 1228 (51) |

| Female | 1378 (45) | 1723 (48) | 1186 (49) |

| Race | |||

| White | 767 (25) | 1542 (43) | 1140 (47) |

| Black | 38 (1) | 94 (3) | 52 (2) |

| Other | 57 (2) | 83 (2) | 42 (2) |

| Unknown | 800 (26) | 1108 (31) | 730 (30) |

| Missing | 1410 (46) | 743 (21) | 450 (19) |

| Hispanic Ethnicity | |||

| Yes | 11 (0.3) | 35 (1) | 24 (1) |

| No | 826 (27) | 1761 (49) | 1339 (56) |

| Unknown | 182 (6) | 395 (11) | 275 (11) |

| Missing | 2053 (67) | 1379 (39) | 776 (32) |

| Age at index LDCT | |||

| 55-59 | 496 (16) | 676 (19) | 446 (19) |

| 60-64 | 676 (22) | 769 (21) | 552 (23) |

| 65-69 | 1026 (33) | 1079 (30) | 752 (31) |

| 70-74 | 670 (22) | 772 (22) | 486 (20) |

| 75-79 | 204 (7) | 274 (8) | 178 (7) |

| Residence | |||

| Urban | 2973 (97) | 3307 (93) | 2162 (90) |

| Rural/Frontier* | 99 (3) | 263 (7) | 252 (10) |

| Insurance at index LDCT† | |||

| Commercial | 939 (30) | 770 (22) | 479 (20) |

| Medicare Advantage | 1340 (44) | 1023 (29) | 698 (29) |

| Medicare FFS | 571 (19) | 1269 (35) | 840 (35) |

| Medicaid | 222 (7) | 508 (14) | 397 (16) |

| Number of outpatient visits | |||

| 0 | 521 (17) | 1184 (33) | 862 (36) |

| 1 | 1060 (34) | 1206 (34) | 911 (38) |

| 2 | 842 (27) | 668 (19) | 376 (16) |

| ≥3 | 649 (21) | 512 (14) | 265 (11) |

| CCI score | |||

| 0 | 1227 (40) | 1611 (45) | 1133 (47) |

| 1 | 951 (31) | 1142 (32) | 768 (32) |

| ≥2 | 894 (29) | 817 (23) | 513 (21) |

Rural/Frontier is based on designations contained in the CO APCD by the Colorado Rural Health Network. Counties not designated as part of a Metropolitan Statistical Area as defined by the United States Office of Management and Budget are designated as rural. Counties that additionally have population density of six or fewer persons per square mile are designated as frontier.

Dual enrolled individuals were classified according to the primary insurance type associated with the index LDCT claim.

Figure 4. Variables associated with lung cancer screening adherence.

Analysis was performed as described in Methods. After adjustment for other covariates, female sex, ages 70-74, and commercial insurance (compared to Medicare Advantage) did not have a statistically significant relationship with screening adherence. † There was a significant interaction between number of outpatient visits and CCI score, therefore these results are presented in Figure 5.

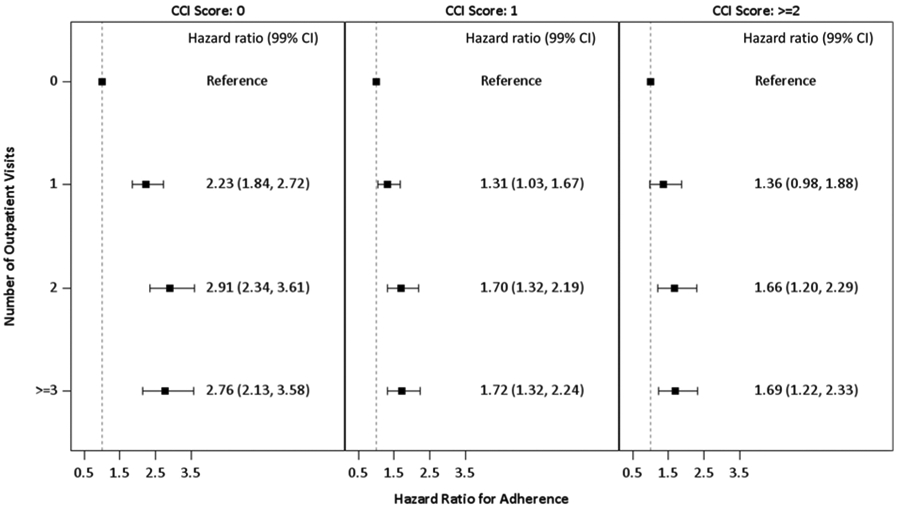

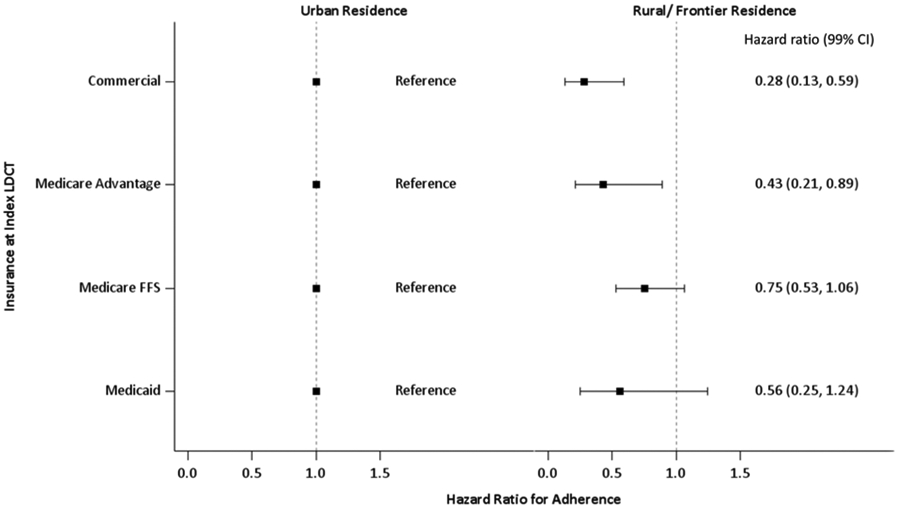

Within the multivariable model, outpatient visits and CCI had a significant interaction (p < 0.0001), the effect of number of outpatient visits at each CCI level are presented in Fig. 5. At each CCI level there was a gradient increase in adherence with increasing outpatient visits; this trend was most pronounced for individuals with no comorbidities. In a secondary analysis, a significant interaction (p = 0.01) was observed between residence and insurance type (Fig. 6); all the resulting hazard ratios are consistent with reduced adherence among rural patients. All sensitivity analyses (using a 15-month definition of adherence, defining any return for screening as adherent, excluding late returning individuals) yielded no differences in results.

Figure 5. Influence of comorbidities and heath care utilization on screening adherence.

After adjustment for other covariates, increased screening adherence is seen with increasing number of outpatient visits across all comorbidity burdens.

Figure 6. Interaction between residence and insurance at index LDCT.

There is a statistically significant reduction in adherence for rural residents with commercial and Medicare Advantage insurance, however this is likely driven by the small number of rural residents with each insurance type (commercial n = 85, Medicare Advantage n = 67, Medicare FFS n = 372, and Medicaid n = 90).

Discussion

Early descriptions of LCS adherence determinants (31, 32) came from clinical trials performed prior to clear proof that LCS reduced mortality and are difficult to contextualize in an environment where LCS is a preventive service delivered in community settings and is now covered by most insurance plans. More recent studies in academic (23 - 27), community (22) or federal health (33) settings have emerged, but no prior studies have used insurance claims to assess LCS adherence (20, 21). Using longitudinal claims data, we found that ages 55-64 and 75-79, rural residence, and Medicare FFS and Medicaid insurance are associated with reduced adherence to annual LCS. While higher healthcare usage and increased comorbidity burden are both associated with increased LCS adherence, the effects of these two variables are inter-dependent.

Our observation that individuals 65-70 years old are most adherent to LCS is relatively consistent with recent LCS adherence meta-analyses that found that individuals 60-75 years old are most adherent (20, 21). Reduced adherence amongst older individuals is likely explained by multiple recommendations to stop LCS as individuals reach their mid-70s (5, 34 - 37) and an increasing proportion of patients who may have a shorter life expectancy and hence derive less screening benefit (38). Younger individuals are less likely to receive preventive services than individuals over 65 (39) and may have competing time priorities and misperceptions about screening cost.

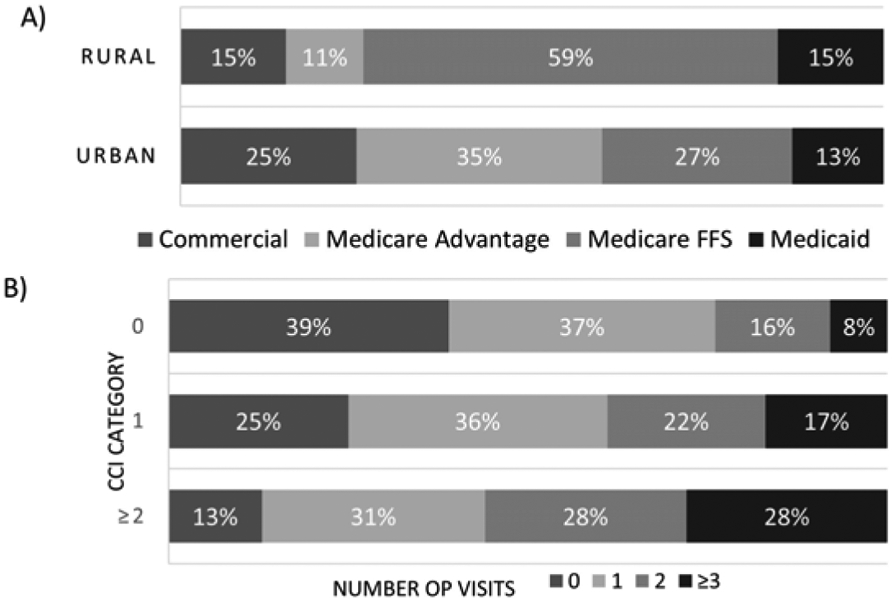

Consistent with other studies (20, 21), we did not observe an association between sex and adherence. While reduced LCS adherence has been observed in racial minorities (32), the amount of missing data on race and ethnicity in our study precluded assessing that important relationship. Rural populations have higher smoking rates, lower socioeconomic status (SES), and use less preventive care than their urban counterparts (40, 41). Our finding that rural residence is associated with reduced adherence is consistent with these demographic characteristics and is supported by the observation in our cohort that ~75% of rural residents have Medicare FFS or Medicaid compared to ~40% of urban residents. (Fig. 7A). Insurance coverage is strongly associated with increased adherence in breast and colon cancer screenings (11, 14, 42); however, the CO APCD is limited to insurance claims, hence we cannot compare insured and uninsured populations. We did find that coverage with Medicare FFS or Medicaid was associated with markedly less adherence compared to coverage by Medicare Advantage or commercial insurance. Medicare Advantage is offered by private insurance companies and there is selection of healthier patients into this program (43). In addition, Medicaid insurance is likely a surrogate for lower SES. A secondary analysis found that adherence of rural patients varies by insurance (Fig. 6), though this is mostly driven by the small number of rural patients with each insurance type.

Figure 7.

(A) Insurance type by residence. (B) Association between comorbidity burden and health care utilization.

We observed a complex relationship between increased adherence and heath care system usage (measured by number of outpatient visits) and comorbidity burden (measured by CCI). Not surprisingly, heath care use and comorbidity burden are closely linked (Fig. 7B) as individuals with co-morbidities are expected to have more health care usage and contact with the health care system is required to obtain the diagnoses that drive comorbidity index measures. That the association between adherence and health care utilization was most pronounced in individuals with no co-morbidities, may suggest that health care utilization alone is associated with higher adherence to preventive services. In breast and colon cancer screening, increased contact with the healthcare system has been associated with improved adherence (14, 44). While higher comorbidity burden has been associated with reduced adherence in breast cancer screening (45), a recent study failed to identify an association between LCS adherence and comorbidity burden in a veteran population (33).

Our 18-month adherence rate was 46%; this is consistent with the 37-66% reported LCS adherence outside of clinical trials (22-27). This may be related to our CO APCD sample being biased by clinicians or programs that are early LCS adopters as overall LCS uptake remains low with only 2-16% of eligible individuals currently receiving LCS (46-50). This notion is supported by the observation that in the CO APCD LCS data set, approximately 20% of all screening was performed by the Kaiser Permanente system. Interestingly, the increased adherence by index screening year (Fig. 3) is consistent with increasing LCS uptake over time (51).

The CO APCD study population is representative of the Colorado and US populations with respect to sex and age (52). Direct comparisons of race and ethnicity are not possible as a large amount of this information is missing in the CO APCD; however, the population of Colorado is less racially diverse than the US population (Colorado population is 84% white and 4% black compared to 72% white and 13% black in the US) (52). Our observation that adherence is highest between ages 65-69, is consistent with prior studies showing that LCS uptake is highest between ages 65-74 (51, 53).

In addition to the intrinsic issues of using claims data for research (54), our study has several limitations. First, due to missing data, we could not include race and ethnicity in our regression model. Not only do minority populations probably have reduced LCS adherence (20, 21), race and ethnicity are likely underrepresented in the CO APCD and probably confound other subject variables such as residence, insurance, and SES. A second limitation is the inability to capture CT results via claims data. Because of this, we were forced to exclude individuals with short interval imaging and lung cancer diagnosis as these individuals could not be accurately classified. A third limitation is that we assumed that all screened individuals met standard smoking history eligibility criteria, however screening of ineligible individuals remains an issue (48, 55); the impact of this is difficult to predict. Fourth, there was missing or incomplete data on enrollment status and length of health insurance coverage period. This could lead to misclassification if an individual were to move out state or no longer be eligible for health insurance coverage in Colorado. Finally, we utilized patient information associated with the index LDCT claim to classify variable information (residence, insurance type) that could potentially change over time leading to misclassification if individuals moved out of state or changed insurance.

This is the first report using insurance claims to identify population-based determinants of LCS adherence. Our findings that age, rural residence, insurance type, and health care use/comorbidity burden influence LCS adherence provides insight into populations that might benefit from specific interventions targeted toward improving adherence and maximizing LCS benefit. Interventions described to increase lung cancer screening adherence include dedicated program coordinators, patient reminders, and mobile screening of rural residents (20, 23, 24, 56). Similar interventions have increased adherence to breast, colon, cervical, and prostate cancer screenings (57-62). Quantifying population-based adherence rates and understanding factors associated with annual adherence is a critical first step in improving screening adherence and ultimately reducing lung cancer death.

Take home points.

Using claims data from the Colorado All Payer Claims Database we observed a 46% population-based adherence rate to annual lung cancer screening guidelines.

Ages 55-64 and 75-79, rural residence, and Medicare FFS and Medicaid insurance are associated with reduced adherence to annual LCS.

While higher healthcare usage and increased comorbidity burden are both associated with increased LCS adherence, the effects of these two variables are inter-dependent.

Acknowledgements:

We thank the Center for Improving Value in Health Care, administrator of the CO APCD, for assistance in acquisition of the dataset.

Sources of support: This research was supported by the University of Colorado Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI/NIH P30CA046934) and by NIH/NCATS Colorado CTSA Grant Number UL1 TR002535. Content is the authors’ sole responsibility and does not necessarily represent official NIH views.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Statement of Data Access and Integrity: The authors declare that they had full access to all of the data in this study and the authors take complete responsibility for the integrity of the data and the accuracy of the data analysis.

Disclosures: Ms. Hirsch reports grants from NIH/ National Cancer Institute, non-financial support from NIH/ National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences, during the conduct of the study. Dr. Studts reports personal fees from Lung Ambition Alliance, outside the submitted work; and Dr. Studts volunteers on the Scientific Leadership Board of the GO2 Foundation for Lung Cancer. Dr. Baron, Dr. Risendal, Dr. New, and Dr. Malkoski have no conflicts of interest to disclose

References

- 1).American Cancer Society, Cancer Facts and Figures 2020. Available at: https://www.cancer.org/content/dam/cancer-org/research/cancer-facts-and-statistics/annual-cancer-facts-and-figures/2020/cancer-facts-and-figures-2020.pdf. Accessed on June 11, 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 2).SEER cancer stat facts: lung and bronchus cancer. National Cancer Institute website. https://seer.cancer.gov/statfacts/html/lungb.html. Accessed on June 11, 2020.

- 3).Aberle DR, Adams AM, Berg CD, et al. National Lung Screening Trial Research Team. Reduced lung-cancer mortality with low-dose computed tomographic screening. N Engl J Med. 2011; 365 (5): 395–409. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4).Koning HJ, van der Aalst CM, de Jong PA, et al. Reduced Lung-Cancer Mortality with Volume CT Screening in a Randomized Trial. N Engl J Med 2020; 382:503–513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5).Centers for Medicare & Medicaid Services. Final National Coverage Determination on Screening for Lung Cancer with Low Dose Computed Tomography (LDCT). 2015. https://www.cms.gov/medicare-coverage-database/details/nca-decision-memo.aspx?NCAid=274. Accessed on June 11, 2020.

- 6).US Preventive Services Task Force. Screening for lung cancer. December 2013. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/Page/Document/UpdateSummaryFinal/lung-cancer-screening. Accessed June 11, 2020.

- 7).US Preventive Services Task Force. Draft Recommendation Statement Lung Cancer: Screening, July 7, 2020. https://www.uspreventiveservicestaskforce.org/uspstf/draft-recommendation/lung-cancer-screening-2020. Accessed August 13, 2020.

- 8).Han SS, Ayca Erdogan S, Toumazia I, Leung A, and Plevritis SK. Evaluating the impact of varied compliance to lung cancer screening recommendations using a microsimulation model. Cancer Causes Control. 2017. September; 28(9): 947–958. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9).Yousaf-Khan U, van der Aalst C, de Jong PA, et al. Final Screening Round of the NELSON Lung Cancer Screening Trial: The Effect of a 2.5-year Screening Interval. Thorax. 2017. January;72(1):48–56. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10).Lairson DR, Chan W, Newmark GR. Determinants of the demand for breast cancer screening among women veterans in the United States. Soc Sci Med. 2005. October;61(7):1608–17. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11).Bernardo BM, Gross AL, Young G, et al. Predictors of Colorectal Cancer Screening in Two Underserved U.S. Populations: A Parallel Analysis. Front Oncol. 2018. June 19; 8:230. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12).Bronner K, Mesters I, Weiss-Meilik, et al. Determinants of adherence to screening by colonoscopy in individuals with a family history of colorectal cancer. Patient Educ Couns. 2013. November;93(2):272–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13).Tatla RK, Paszat LF, Bondy SJ, Chen Z, Chiarelli AM, and Mai V. Socioeconomic Status & Returning for a Second Screen in the Ontario Breast Screening Program. Breast. 2003. August;12(4):237–46 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14).Akinyemiju TF, Soliman AS, Yassine M, Banerjee M, Schwartz K, and Merajver S. Healthcare access and mammography screening in Michigan: a multilevel cross-sectional study. Int J Equity Health. 2012. March 21; 11:16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15).Pang H, Cataldi M, Allseits E, et al. Examining the association between possessing a regular source of healthcare and adherence with cancer screenings among Haitian households in Little Haiti, Miami-Dade County, Florida. Medicine (Baltimore). 2017. August;96(32): e7706. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16).Qi V, Phillips SP, Hopman WM. Determinants of a healthy lifestyle and use of preventive screening in Canada. BMC Public Health. 2006. November 7; 6:275. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17).Stockwell DH, Woo P, Jacobson BC, et al. Determinants of colorectal cancer screening in women undergoing mammography. Am J Gastroenterol. 2003. August;98(8):1875–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18).Shelton RC, Jandorf L, Ellsion J, Villagra C, and DuHamel KN. The influence of sociocultural factors on colonoscopy and FOBT screening adherence among low-income Hispanics. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2011. August;22(3):925–44. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19).Benito L, Farre A, Binefa G, et al. Factors related to longitudinal adherence in colorectal cancer screening: qualitative research findings. Cancer Causes Control. 2018. January;29(1):103–114. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20).Lam ACL, Aggarwal R, Cheung S, et al. Predictors of Participant Nonadherence in Lung Cancer Screening Programs: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis, Lung Cancer (2020), doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2020.05.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21).Lopez-Olivo MA, Maki KG, Choi NJ, et al. Patient Adherence to Screening for Lung Cancer in the US: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA Netw Open. 2020. November 2;3(11):e2025102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22).Catteneo SM, Meisenberg BR, Geronimo MCM, Bhandari B, Maxted JW, and Brady-Copertino CJ. Lung Cancer Screening in the Community Setting. Ann Thorac Surg 2018; 105:1627–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23).Hirsch EA, New ML, Brown S, Báron AE, Malkoski SP. Patient Reminders and Longitudinal Adherence to Lung Cancer Screening in an Academic Setting. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2019. October; 16(10):1329–1332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24).Spalluto LB, Lewis JA, LaBaze S, et al. Association of a Lung Screening Program Coordinator with Adherence to Annual CT Lung Screening at a Large Academic Institution. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020. February;17(2):208–215 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25).Triplette M, Thayer JH, Kross EK, et al. The Impact of Smoking and Screening Results on Adherence to Follow-up in an Academic Multisite Lung Cancer Screening Program. Ann Am Thorac Soc. 2020. September 18. doi: 10.1513/AnnalsATS.202006-631RL. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26).Mortani Barbosa EJ Jr, Yang R, and Hershman M. Real World Lung Cancer CT Screening Performance, Smoking Behavior, and Adherence to Recommendations: Lung-RADS Category and Smoking Status Predict Adherence. AJR Am J Roentgenol. 2020. July 15. doi: 10.2214/AJR.20.23637. Epub ahead of print. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27).Bellinger C, Foley K, Genese F, Lampkin A, and Kuperberg S. Factors Affecting Patient Adherence to Lung Cancer Screening. South Med J. 2020. November;113(11):564–567. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28).Charlson ME, Pompei P, Ales KL, MacKenzie CR. A new method of classifying prognostic comorbidity in longitudinal studies: development and validation. J Chronic Dis. 1987;40(5):373–383. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29).Volk ML, Hernandez JC, Lok AS, Marrero JA. Modified Charlson Comorbidity Index for Predicting Survival After Liver Transplantation. Liver Transpl. 2007. November;13(11):1515–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30).Zavascki AP and Fuchs SC. The need for reappraisal of AIDS score weight of Charlson comorbidity index. J Clin Epidemiol. 2007. September;60(9):867–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31).Montes U, Seijo LM, Campo A, Alcaide AB, Bastarrika G, and Zulueta JJ. Factors determining early adherence to a lung cancer screening protocol. Eur Respir J. 2007. September;30(3):532–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32).Wildstein KA, Faustini Y, Yip R, Henschke CI, and Ostroff JS. Longitudinal predictors of adherence to annual follow-up in a lung cancer screening programme. J Med Screen. 2011;18(3):154–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33).Tanner NT, Brasher PB, Wojciechowski B, et al. Screening Adherence in the Veterans Administration Lung Cancer Screening Demonstration Project, CHEST (2020), doi: 10.1016/j.chest.2020.04.063. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34).Mazzone PJ, Silvestri GA, Patel S, et al. Screening for Lung Cancer CHEST Guideline and Expert Panel Report. Chest 2018; 154(4): 954–985. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35).Wood DE, Kazerooni EA, Baum SL, et al. Lung Cancer Screening, Version 3.2018, NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology. J Natl Compr Canc Netw. 2018. April;16(4):412–441 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36).Wender R, Fontham ETH, Barrera E, et al. American Cancer Society Lung Cancer Screening Guidelines. CA Cancer J Clin. Mar-Apr 2013;63(2):107–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37).Roberts H, Walker-Dilks C, Sivjee K, et al. Screening high-risk populations for lung cancer: guideline recommendations. J Thorac Oncol 2013; 8:1232–1237 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38).Kotwal AA and Schonberg MA. Cancer Screening in the Elderly: A Review of Breast, Colorectal, Lung, and Prostate Cancer Screening. Cancer J. 2017. Jul-Aug; 23(4): 246–253. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39).Kim ES, Mooreda KD, Giasson HL, and Smith J. Satisfaction with Aging and Use of Preventive Health Services. Prev Med. 2014. December; 69: 176–180. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40).Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. Smoking & Tobacco Use: Tobacco Use by Geographic Region. Available at: https://www.cdc.gov/tobacco/disparities/geographic/index.htm. Accessed on June 11, 2020.

- 41).Loftus J, Allen EM, Call KT, and Everson-Rose SA. Rural-Urban Differences in Access to Preventive Health Care Among Publicly Insured Minnesotans. J Rural Health. 2018. February; 34(Suppl 1): s48–s55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42).Meyer CP, Allard CB, Sammon JD, et al. Data on Medicare eligibility and cancer screening utilization. Data Brief. 2016. June; 7: 679–681. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43).Cooper AL and Trivedi AN. Fitness memberships and favorable selection in Medicare Advantage plans. N Engl J Med. 2012; 366:150–157. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44).Duncan A, Turnbull D, Wilson C, et al. Behavioural and demographic predictors of adherence to three consecutive faecal occult blood test screening opportunities: a population study. BMC Public Health 2014, 14:238. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45).Hubbard RA, O’Meara ES, Henderson LM, et al. Multilevel factors associated with long-term adherence to screening mammography in older women in the U.S. Prev Med. 2016. August; 89: 169–177. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46).Jemal A and Fedewa SA. Lung cancer screening with low-dose computed tomography in the United States-2010 to 2015. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3(9):1278–1281. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47).Pham D, Bhandari S, Oechsli M, Pinkston CM, Kloecker GH. Lung cancer screening rates: Data from the lung cancer screening registry. J Clin Oncol 2018;36(15_suppl):6504–6504.9. [Google Scholar]

- 48).Huo J, Shen C, Volk RJ, and Shih Y-CT. Use of CT and Chest Radiography for Lung Cancer Screening Before and After Publication of Screening Guidelines: Intended and Unintended Uptake. JAMA Int Med 2017;177(3):439–441.11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49).Zahnd WE and Eberth JM. Lung Cancer Screening Utilization: A Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System Analysis. Am J Prev Med 2019. August;57(2):250–255. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50).Yong PC, Sigel K, Rehmani S, Wisnivesky J, Kale MS. Lung Cancer Screening Uptake in the United States. Chest 2020;157(1):236–238 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51).Okereke IC, Nishi S, Zhou J, and Goodwin JS. Trends in lung cancer screening in the United States, 2016-2017. J Thorac Dis. 2019. March;11(3):873–881. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52).United States Census Bureau. ACS Demographics and Housing Estimates. Available at: https://data.census.gov/cedsci. Accessed on August 13, 2020.

- 53).Zgodic A, Zahnd WE, Miller DP Jr, Studts JL, and Eberth JM. Predictors of Lung Cancer Screening Utilization in a Population-Based Survey. J Am Coll Radiol. 2020. July 16; S1546-1440(20)30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54).Rai A, Doria-Rose VP, Silvestri GA, Yabroff KR. Evaluating Lung Cancer Screening Uptake, Outcomes, and Costs in the United States: Challenges with Existing Data and Recommendations for Improvement. JNCI J Natl Cancer Inst (2019) 111(4): djy228. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55).Triplette M, Thayer JH, Pipavath SN, Crothers K. Poor Uptake of Lung Cancer Screening: Opportunities for Improvement. J Am Coll Radiol. 2019. April;16(4 Pt A):446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56).Crosbie PA, Balata H, Evison M, et al. Second round results from the Manchester 'Lung Health Check' community-based targeted lung cancer screening pilot. Thorax. 2019. July;74(7):700–704 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57).Jandorf L, Feldman Hecht M, Winkel G, et al. Increasing Cancer Screening for Latinas: Examining the Impact of Health Messages and Navigation in a Cluster-Randomized Study. J of Racial and Ethnic Health Disparities. 2014; 1 (85–100). [Google Scholar]

- 58).Phillips CE, Rothstein JD, Beaver K, Sherman BJ, Freund KM, and Battaglia TA. Patient navigation to increase mammography screening among inner city women. J Gen Intern Med. 2011. February;26(2):123–9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59).Baker DW, Brown T, Buchanan DR, et al. Comparative Effectiveness of a Multifaceted Intervention to Improve Adherence to Annual Colorectal Cancer Screening in Community Health Centers. JAMA Intern Med. 2014;174(8):1235–1241 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60).DeFrank JT, Rimer BK, Gierisch JM, Bowling JM, Farrell D, and Skinner CS. Impact of Mailed and Automated Telephone Reminders on Receipt of Repeat Mammograms. Am J Prev Med. 2009. June; 36(6): 459–467. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61).Brouwers MC, De Vito C, Bahirathan L, et al. Interventions to facilitate the uptake of breast, cervical and colorectal cancer screening: an implementation guideline. Implement Sci. 2011. September 29; 6:112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62).Abdel-Aleem H, El-Gibaly OM, El-Gazzar AF, and Al-Attar GS. Mobile clinics for women's and children's health. Cochrane Database Syst Rev 2016; Issue 8:CD009677. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]