Abstract

Pre-clinical early-life stress paradigms model early adverse events in humans. However, the long-term behavioral consequences of early-life adversities after traumatic brain injury (TBI) in adults have not been examined. In addition, endocannabinoids may protect against TBI neuropathology. Hence, the current study assessed the effects of adverse stress during adolescence on emotional and cognitive performance in rats sustaining a TBI as adults, and how cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1) activation impacts the outcome. On postnatal days (PND) 30–60, adolescent male rats were exposed to four weeks of chronic unpredictable stress (CUS), followed by four weeks of no stress (PND 60–90), or no stress at any time (Control), and then anesthetized and provided a cortical impact of moderate severity (2.8 mm tissue deformation at 4 m/s) or sham injury. TBI and Sham rats (CUS and Control) were administered either arachidonyl-2′-chloroethylamide (ACEA; 1 mg/kg, i.p.), a CB1 receptor agonist, or vehicle (VEH; 1mL/kg, i.p.) immediately after surgery and once daily for 7 days. Anxiety-like behavior was assessed in an open field test (OFT) and learning and memory in novel object recognition (NOR) and Morris water maze (MWM) tasks. No differences were revealed among the Sham groups in any behavioral assessment and thus the groups were pooled. In the ACEA and VEH-treated TBI groups, CUS increased exploration in the OFT, enhanced NOR focus, and decreased the time to reach the escape platform in the MWM, suggesting decreased anxiety and enhanced learning and memory relative to the Control group receiving VEH (p<0.05). ACEA also enhanced NOR and MWM performance in the Control + TBI group (p<0.05). These data suggest that 4 weeks of CUS provided during adolescence may provide protection against TBI acquired during adulthood and/or induce adaptive behavioral responses. Moreover, CB1 receptor agonism produces benefits after TBI independent of CUS protection.

Keywords: cannabinoid receptor 1 (CB1), chronic unpredictable stress (CUS), controlled cortical impact (CCI), early life stress (ELS), endocannabinoids, traumatic brain injury (TBI)

1. Introduction

Preclinical early-life stress (ELS) paradigms model adverse events in humans (Farkas et al., 2017). Exposure to repetitive stressful life events as secondary stressors and day-to-day trauma reminders are thought to increase the salience of the traumatic event (e.g., traumatic brain injury; TBI), which precipitate symptoms of psychiatric disorders commonly associated with mood, anxiety, and substance-use (Alway et al., 2016). Higher levels of acute stress disorder are observed in mild TBI patients, which often results in longer hospital admissions and higher levels of psychosocial distress (Broomhall et al., 2009). Indeed, early life adversity can lead to dysregulated stress reactivity that exacerbates future stress-related disease states, including those that manifest after TBI (Russell et al., 2018).

Adolescence is a critical period for the emergence of several psychiatric disorders, including depression and anxiety that can be potentiated by stress-induced alterations in the developmental trajectories of the cortico-limbic neurocircuitry (Andersen and Teicher, 2008; Paus et al., 2008; Whittle et al., 2014). Consistent with animal models, the dynamic elaboration and pruning of dendritic lengths and branching complexity occurring in the dorsal and ventral hippocampus during the developmental period of adolescence is disrupted after isolation-stress in rats, which in standard pair-housed conditions are essential for cognitive and emotional behavior in early adulthood (Chen et al., 2018). When tested well into adulthood, chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) in adolescent rats decreases behavioral inhibition through increased impulsivity to explore novel objects in a recognition task (NOR) and novel environments in the open field test (OFT) (Chaby et al., 2013). In addition, adult rats exposed to adolescent CUS exhibit enhanced reversal learning and the ability to maintain the location of a novel reward in working memory more than 6 months after stress exposure relative to unstressed rats. However, after exposure to a novel chamber, these adolescent-stressed rats exhibited increased latency to locate the reward, suggesting that adolescent-stress increases vulnerability to a disturbance in working memory (Chaby et al., 2015a).

The endocannabinoid system has been implicated as a potential therapeutic target for TBI (Mechoulam and Shohami, 2007; Shohami et al., 2011; Schurman and Lichtman, 2017; Magid et al., 2019). Daily administration (1 mg/kg) of the CB1 receptor agonist arachidonyl-2′-chloroethylamide (ACEA) following moderate controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury in young adult rats improves cognitive performance in NOR and Morris water maze (MWM) tasks (Arain et al., 2015). Furthermore, ACEA (0.1 mg/kg), reduces freezing behavior in adolescent (PND 40–45) male rats after 3 weeks of CUS exposure (Reich et al., 2013) while local CB1 receptor antagonism with AM251 within the prefrontal cortex further increases immobility in the forced swim test after CUS (McLaughlin et al., 2013). CB1 receptors are also highly expressed on GABAergic and glutamatergic terminals of the hippocampus, frontal cortex, striatum, amygdala, and other brain areas sensitive to stress (Morena et al., 2016) and excitotoxic injury (Schurman and Lichtman, 2017). The two main cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2 are believed to confer protective effects after TBI, by reducing inflammation via CB2 receptors found primarily in immune cells such as microglia and by producing on-demand downregulation of excitotoxicity via CB1 receptors found primarily in neurons. However, CB1 receptors are the sole mediators of the psychotropic effects of cannabinoids (Magid et al., 2019). Yet, both CB1 and CB2 receptors are found to be functional in peripheral and brain tissues (Liu et al., 2020).

The most abundant endocannabinoid in the brain 2AG (2-Arachidonoyl-glycerol), has higher affinity to the CB2 endogenous ligand, while the endocannabinoid structurally like THC ((–)-trans-Δ9-tetrahydrocannabinol, the principal psychoactive ingredients of Cannabis sativa), AEA (N-arachidonoylethanolamine, or anandamide) has higher affinity to the CB1 endogenous ligand (Leishman et al., 2018). These lipid-signaling molecules (2AG and AEA) have been shown to regulate cognitive and emotional behavioral function by modulating the neuroendocrine stress response (Gorzalka and Hill, 2009; Ruehle et al., 2012). For example, genetic knockout of the main 2-AG producing enzyme DAGL-α (diacylglycerol lipase α), reduces exploration of the central area of the open field and increases anxiety-related behaviors in the light/dark box, fear and despair behavior, associated with reduced hippocampal neurogenesis in mice (Jenniches et al., 2016). Moreover, transgenic mice with CB1-deficient newborn neurons display despair behavior in the forced swim test, impaired performance in the NOR test, and decreased spatial learning in the MWM (Zimmermann et al., 2018). Hence, in the current study, ACEA administration may result in beneficial effect on behavioral responses post TBI through the neuromodulatory role of CB1 receptor activation.

Taken together, the neuroendocrine stress and endocannabinoid systems are functionally related, and may play a major role in neurobehavioral outcomes observed after TBI (de la Tremblaye et al., 2018). Thus, we hypothesize that chronic stress during adolescence may produce adaptive changes later in life, both in emotional and cognitive behaviors, underlying an altered programming of stress and neuroplasticity mechanisms that decrease the vulnerability to TBI in adulthood. In addition, CB1 receptor activation after TBI will enhance cognition in adult TBI rats.

2. Results

One rat from the Control + TBI + ACEA group was unable to locate the visible platform during testing, suggesting visual acuity deficits, and was omitted from the study. Thus, the final group sizes were: Control + TBI + VEH (n=11), Control + TBI + ACEA (n=10), CUS + TBI + VEH (n=11), CUS + TBI + ACEA (n=11). There were no statistical differences among the four sham groups in any of the behavioral assessments (supplemental Figs.1-3) and thus they were pooled and analyzed as one group (denoted as SHAM; n=40, which consisted of 10 per group corresponding to the TBI groups). However, the weight gain data for the Sham groups are analyzed and presented separately (i.e., not pooled) as significant differences were observed between the Control and CUS groups.

2.1. Acute neurological evaluation

No significant differences were observed among the TBI groups in time to recover the hind limb withdrawal reflex in response to a brief paw pinch [left range = 173.9 ± 5.6 s to 181.4 ± 5.9 s, p>0.05; right range = 164.3 ± 5.2 s to 173.7 ± 7.4 s, p>0.05] or for return of righting ability [range 367.9 ± 21.4 s to 398.5 ± 32.8 s, p>0.05] following the cessation of anesthesia. The lack of significant differences with these acute neurological indices suggests that all TBI groups experienced an equivalent level of injury and anesthesia. There were also no significant differences in reflexes for SHAM rats indicating that they too were treated similarly: paw pinch (left = 30.3 ± 4.4 s to 36.5 ± 2.6 s, p>0.05; right = 25.2 ± 3.6 s to 29.3 ± 3.1 s, p>0.05; righting reflex (109.3 ± 9.6 s to 116.3 ± 7.4 s, p>0.05).

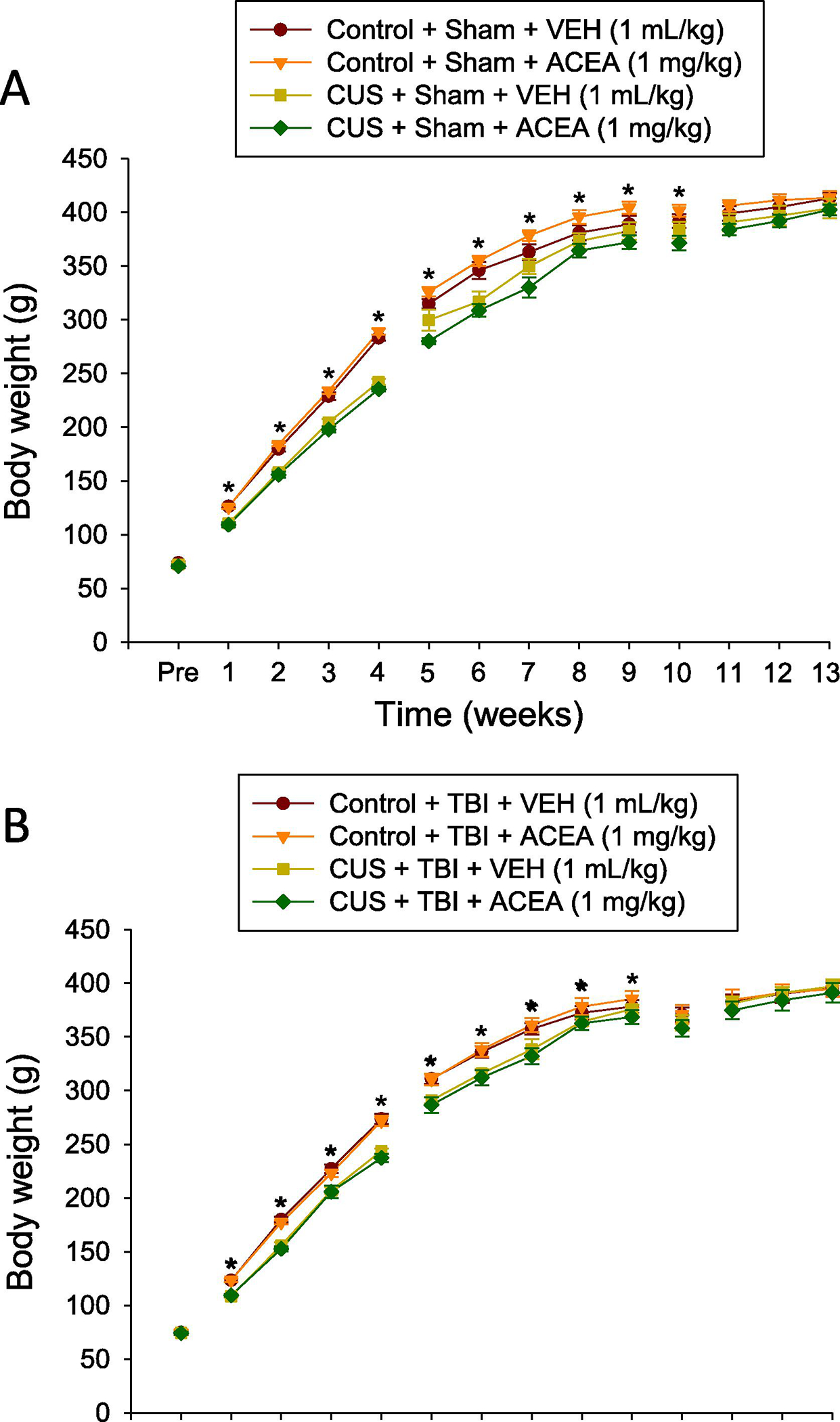

2.2. Body weight

Body weight was recorded at baseline (before any manipulations) and once weekly to evaluate the effect of CUS on weight gain and to monitor recovery after TBI or sham injury. No significant differences were noted at baseline among the groups randomized for TBI as pup weights ranged from 74.1 ± 1.2 g to 74.7 ± 2.5 g; [F3,39 = 0.039, p=0.98] (Fig. 1A) or for groups randomized to Sham as weights ranged from 70.6 ± 1.7 g to 73.7 ± 1.3 g; [F3,39 = 0.783, p=0.51] (Fig. 1B). For the eventual TBI groups, the repeated measures ANOVA for the 4-week period during CUS revealed significant Group [F3,39 = 29.905, p<0.0001] and Day [F3,117 = 2518.9, p<0.0001] differences, as well as a significant Group x Day interaction [F9,117 = 3.683, p=0.0004]. For the rats destined to become Shams, the repeated measures ANOVA for the 4-week CUS period revealed significant Group [F3,36 = 73.049, p<0.0001] and Day [F3,108 = 5493.1, p<0.0001] differences, as well as a significant Group x Day interaction [F9,108 = 21.92, p<0.0001]. The post-hoc analyses revealed that CUS rats had less weight gain than the Controls [p<0.05]. The reduction in weight gain for the stressed rats continued after the 4-week CUS paradigm and up to surgery day as indicated by the repeated measures ANOVA, which revealed significant Group [F3,39 = 3.18, p=0.034], [F3,36 = 8.939, p<0.0001], and Day [F4,156 = 397.286, p<0.0001], [F4,144 = 311.178, p<0.0001] differences for the TBI and Sham groups, respectively. All groups gained weight after surgery and did not differ from one another [F3,39 = 0.235, p=0.87] and [F3,36 = 2.09, p=0.12] for TBI and Sham groups, respectively.

Fig. 1.

AB. Mean (± S.E.M.) body weight recorded at baseline (before any manipulations) and once weekly to evaluate the effect of stress on weight gain and to monitor recovery after Sham injury (A) or TBI (B). For panel A, *p<0.05 vs. Control + Sham + VEH and Control + Sham + ACEA. For panel B, *p<0.05 vs. Control + TBI + VEH and Control + TBI + ACEA. No other comparisons were significant.

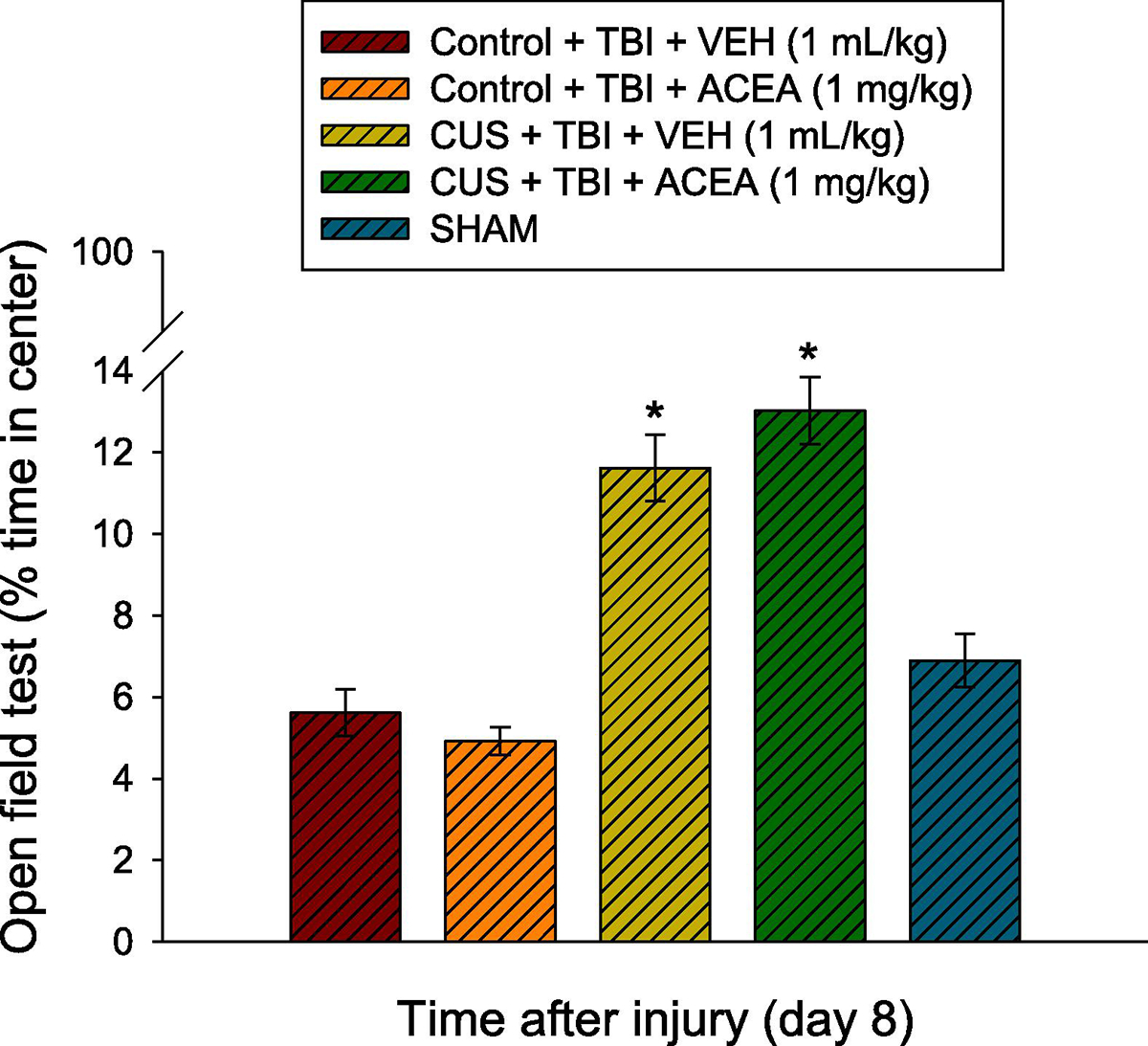

2.3. Open-field test (OFT)

There were no differences among the Sham groups for percent-time spent in the center zone in the open-field test [F3.36 = 0.319, p=0.81; Supplemental Fig. 1]. Because of the lack of differences, the Sham data were pooled and included in the statistical analysis with the TBI groups where the ANOVA revealed a significant Group effect [F4,78 = 15.209, p<0.0001]. Specifically, the post-hoc analysis revealed that the CUS + TBI + VEH and CUS + TBI + ACEA groups spent a greater percent of exploratory time in the center zone relative to the Control + TBI + VEH, Control + TBI + ACEA, and SHAM groups [p<0.05; Fig. 2]. There was no difference between the two CUS + TBI groups [p>0.05] or among the two Control groups and pooled SHAM [p>0.05].

Fig. 2.

Mean (± S.E.M.) percent-time spent in the center zone in the open-field test. *p<0.05 vs. Control + TBI + VEH, Control + TBI + ACEA, and SHAM. There was no difference between the CUS + TBI + VEH and CUS + TBI + ACEA groups (p>0.05). The Control groups, regardless of treatment (VEH or ACEA) did not differ from SHAM (p>0.05). No other comparisons were significant.

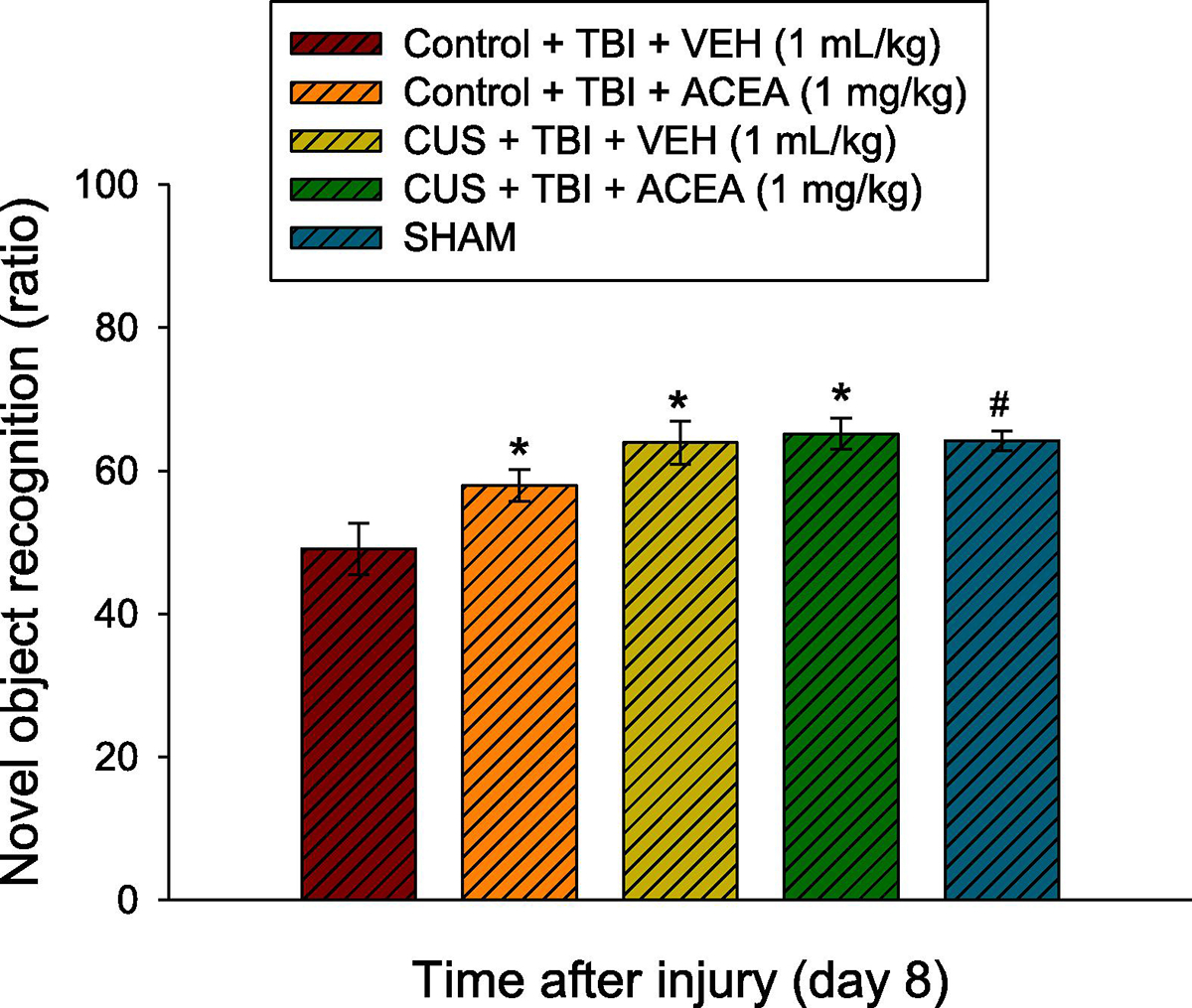

2.4. Novel object recognition (NOR)

The ANOVA revealed a significant Group [F4,78 = 7.313, p<0.0001] difference. The post-hoc analysis showed that the SHAM, CUS + TBI + VEH, CUS + TBI + ACEA, and Control + TBI + ACEA groups performed better (i.e., increased time exploring the novel object) than the Control + TBI + VEH group [p<0.05] and did not differ from each other [p>0.05]. Albeit not statistically significant, the CUS + TBI + ACEA group trended (p=0.07) toward greater improvement relative to the Control + TBI + ACEA group (65.2 ± 2.2 vs. 57.9 ± 2.2). Supplemental Fig. 2 depicts the individual Sham groups after an ANOVA revealed no differences [F3,36 = 2.458, p=0.078].

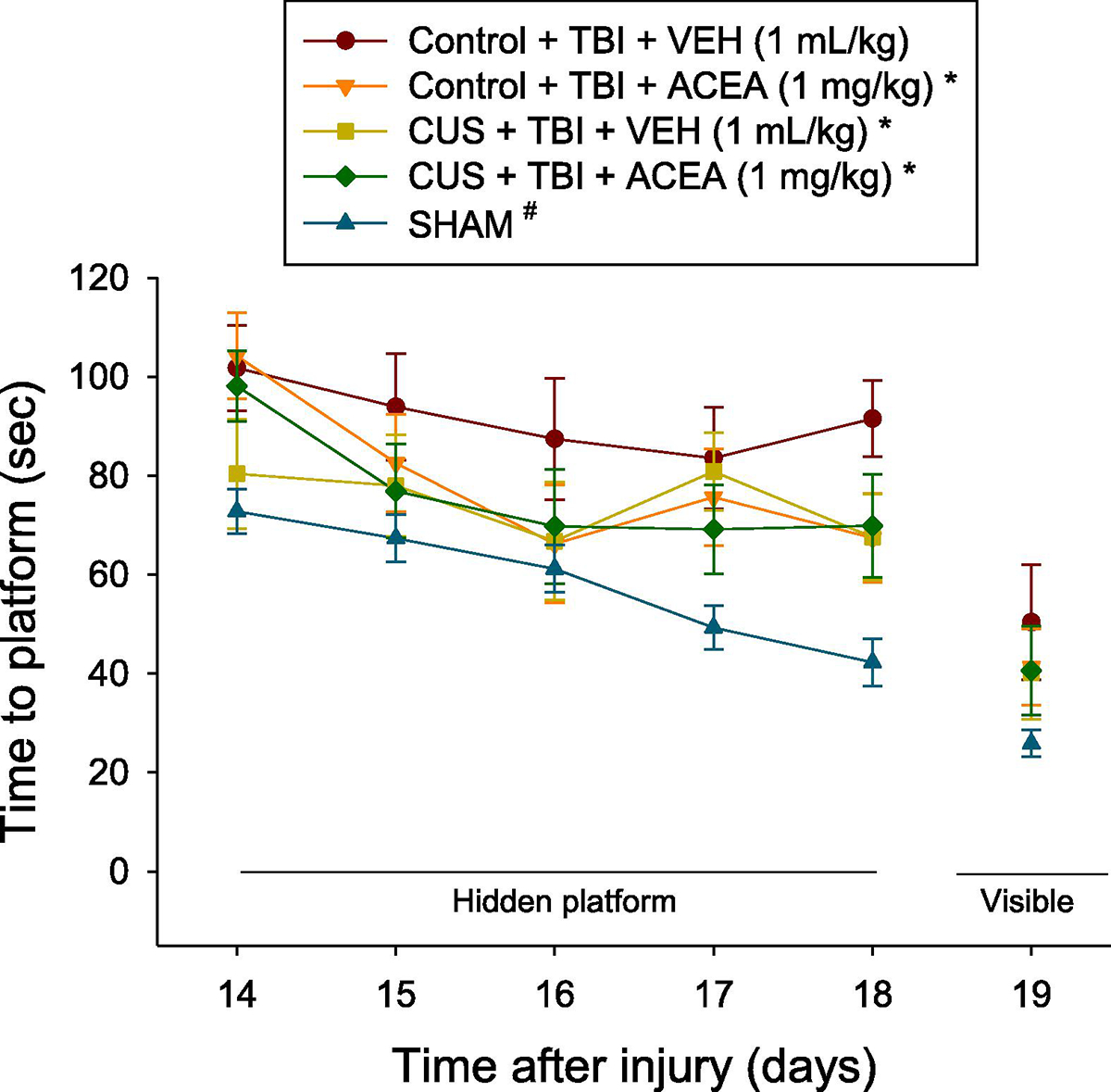

2.5. Cognitive function: acquisition of spatial learning (time to platform)

There were no differences among the Sham groups in time to locate the hidden platform [F3.36 = 1.08, p=0.37; Supplemental Fig. 3]. As such, the Sham data were pooled and included in the statistical analysis with the TBI groups where the repeated measures ANOVA revealed significant Group [F4,78 = 12.379, p<0.0001] and Day [F4,312 = 6.586, p<0.0001] differences. Post-hoc analysis revealed that the SHAM group was significantly better than all TBI groups at locating the escape platform [p’s<0.05; Fig 4]. Other post-hoc analyses showed that the CUS + TBI + VEH, CUS + TBI + ACEA, and Control + TBI + ACEA groups were able to locate the platform significantly quicker over time vs. the Control + TBI + VEH group [p<0.05] and did not differ from one another [p>0.05]. No significant differences were observed among the TBI and SHAM groups in swim speed (range = 27.9 ± 1.8 cm/s to 31.1 ± 0.7 cm/s) [p>0.05] or time to reach the visible platform [p>0.05].

Fig. 4.

Mean (± S.E.M.) time (s) to locate a hidden and visible platform in the Morris water maze after TBI or SHAM injury. For the hidden platform assessments, *p<0.05 vs. Control + TBI + VEH and #p<0.05 vs. all TBI groups. The Control + TBI group treated with ACEA performed at the same level as the CUS groups. No other comparisons reached significance. No differences were observed among the groups on the visible platform assessment (p>0.05).

2.6. Probe trial (memory retention)

Analysis of the probe data did not reveal significant differences among the four TBI or pooled SHAM groups in memory retention. All groups exhibited chance level performance in the percent of allotted time spent in the target quadrant (range = 23.6 ± 2.7 % to 27.4 ± 2.3 %) [p>0.05]. Graphical representation of the data not shown due to the lack of group differences.

3. Discussion

The aim of the study was to determine what effect chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) provided during adolescence has on neurobehavioral and cognitive outcome after adult TBI. The data revealed that four weeks of CUS during PND 30–60 protected against affective symptoms and persistent cognitive impairment. Specifically, relative to non-stressed TBI rats (Controls), adult TBI rats exposed to CUS exhibited decreased anxiety-like behavior and improved recognition memory assessed in open field and NOR tests, respectively. Moreover, CUS facilitated spatial learning in a well-validated MWM paradigm (Kline et al., 2000, 2012; Bleimeister et al., 2019). These outcomes were observed with or without ACEA treatment, which indicates that moderate CUS when experienced in adolescence may be protective against affective and cognitive impairments induced after a TBI acquired as an adult.

The facilitation in learning the location of the escape platform in the MWM by CUS in the current study is consistent with previous results showing that adult male rats exposed to 10 days of CUS exhibited both shorter latencies and path lengths to reach the hidden platform compared to controls. Furthermore, the CUS rats swam less in the outer portion of the maze during the probe trial, which is suggestive of less thigmotaxis and greater active searching (Gouirand and Matuszewich, 2005). Additionally, a 2-week CUS paradigm in adult rats resulted in better long-term memory for platform location in a radial arm water maze (Hawley et al, 2012). However, CUS in adolescent rats did not reduce cognitive flexibility deficits, assessed with an attentional set shifting task (AST) in adult rats even after a 3-week no-stress period (Zhang et al., 2017). CUS also did not improve memory retention assessed with a single probe trial in the current study. The lack of group differences among brain injured CUS and Controls vs. the pooled SHAM group is surprising as historical data from our laboratories consistently show a marked benefit in the Sham groups. Typically, Sham rats spend approximately 40% of the allotted time searching in the target quadrant vs. untreated TBI rats who spend only 25% of the time in the target quadrant, which is chance level performance (Kline et al., 2007, 2010; Radabaugh et al., 2016; Free et al., 2017). This finding underscores an anomaly in the probe testing that leaves unanswered the question of whether CUS might also protect against memory deficits. Nevertheless, the anxiolytic behavior in the OFT and the enhanced cognitive performance in the NOR and MWM tests collectively point to improved stress coping and increased resilience in adult TBI rats exposed to CUS in adolescence.

Like CUS, ACEA treatment during the first week after TBI also improved performance in the NOR and MWM tasks in both the CUS and Control groups but did not reduce anxiety-like behavior in either group. The beneficial effects of ACEA are in accord with other studies showing a neuroprotective role of CB1 cannabinoid receptor activation in vitro and in vivo (Ma et al., 2015; Bai et al., 2017; Vrechi et al., 2018; Palomba et al., 2020). Specifically, a single administration of the CB1 receptor agonist ACEA at a dose like what was provided in the current study increased cell viability and mitochondrial function and reduced neuronal apoptosis and ischemic brain infarct volume in rats after middle cerebral artery occlusion (Yang et al., 2020).

In the current study, ACEA treatment led to only a slight improvement in cognitive performance in the NOR task for the CUS groups, which may have been due to the long-term effect of CUS being too robust for the ACEA treatment to improve the stress-induced beneficial effects further. Our findings are in line with a previous report by Santori et al. (2019) demonstrating that systemic elevation of cannabinoid signaling prevents recognition memory impairments in the NOR test after swim stress exposure, while not altering performance in un-impaired controls. Thus, the effects of ACEA on cognitive behavior appear to be dependent on the adaptive response to adolescent stress exposure.

The neuroprotective effects of ACEA have been linked to its action on CB1 receptors located in mitochondria rather than on the plasma membrane of neurons. In a murine model of bilateral common carotid artery occlusion, Ma and colleagues concluded that ACEA protects neurons from ischemic damage via the inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening (Ma et al., 2018). CB1 receptors are also highly expressed on GABAergic and glutamatergic terminals of the hippocampus, frontal cortex, striatum, amygdala, and other brain areas sensitive to stress (Morena et al., 2016) and excitotoxic injury (Schurman and Lichtman, 2017). The two main cannabinoid receptors, CB1 and CB2 are believed to confer protective effects after TBI, by reducing inflammation via CB2 receptors found primarily in immune cells such as microglia and by producing on-demand downregulation of excitotoxicity via CB1 receptors found primarily in neurons. However, CB1 receptors are the sole mediators of the psychotropic effects of cannabinoids (Magid et al., 2019). Yet, both CB1 and CB2 receptors are found to be functional in peripheral and brain tissues (Liu et al., 2020).

In the current study, CUS rats lagged in weight gain through the duration of the study relative to Control rats, which is consistent with other studies showing a persistent chronic stress-induced decrease in body weight gain in young and adult rats (Zhang et al., 2017; Rusznak et al., 2018). The data in the current study indicates that these long-term physiological effects of CUS during adolescence confer adaptive changes later in life that decreases the vulnerability to TBI in adulthood. Interestingly, the timing of the stress experience appears to be relevant for the beneficial effects conferred by CUS exposure. Previous data from our laboratory showed that maternal separation for 180 min per day during the first 21 post-natal days followed by a mild TBI impaired cognitive performance while increasing microglial activation adjacent to the injury and the contralateral CA1 hippocampal subfield, suggesting that increased neuroinflammation was a mechanism induced by ELS (Diaz-Chavez et al., 2020). There is an upregulation in the microglial activation pathway following neonatal maternal deprivation or chronic mild stress in early youth, and even more when combined successively, as evidenced by increased protein levels of the neuroinflammation markers Iba-1, pPI3K/PI3K, pacts/Akt, and NF-κB in the prefrontal cortex and hippocampus, which are associated with increased emotional and cognitive dysfunction in adolescent female rats (Ye et al., 2019). Furthermore, increased peripheral inflammation and dysregulated neuroinflammation and altered social and open field behavior have been reported after 2 and 4 weeks of adolescent chronic predatory stress starting on PND 34, indicating that adolescent stress can impact neuroinflammation in early adulthood (Eidson et al., 2019). Thus, the timing and the type of stress exposure is important to note when considering the long-term impact of ELS on neurobehavioral outcome after TBI in adulthood.

In summary, the data show that aversive environmental conditions during adolescence induce adaptive emotional and cognitive responses in TBI rats reflecting a greater ability to engage in stress-coping strategies that likely have beneficial effects in future stress challenges, such as after a TBI. Moreover, long-term stress exposure can interact with ACEA, a CB1 receptor agonist, and improve affect and cognition after TBI. Our findings showing that adolescent stress and ACEA treatment can improve behavioral outcome post-TBI in adulthood is important considering that adults with a prior history of mild to moderate TBI have a higher prevalence of cannabis use and screen positive for elevated psychological distress when compared to adults without a history of trauma (Ilie et al., 2015; Durand et al., 2016; Rabner et al., 2016). Further work is needed to determine the use of cannabis to alleviate stress and the potential dosing challenges given the range of THC potency in cannabis products.

4. Materials and methods

4.1. Animals

Eighty-four male Sprague-Dawley rats were obtained at postnatal day-21 (PND-21) from Envigo RMS, Inc., (Indianapolis, IN) and were pair-housed in ventilated polycarbonate rat cages and maintained in a temperature (21 ± 1°C) and light (on 7:00 a.m. to 7:00 p.m.) controlled environment with food and water available ad libitum (except for brief periods during the scheduled stress sessions). All experimental procedures were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee at the University of Pittsburgh. Every attempt was made to limit the number of rats used and to minimize suffering.

4.2. Chronic unpredictable stress (CUS) exposure during adolescence

After one week of acclimatization, the rats were randomly assigned to an experimental stressor group (n=42) and exposed to 4 weeks of CUS during PND 30–60 to cover the entire adolescent period (Sengupta, 2013; Dutta and Sengupta, 2016) or to an unstressed Control group (n=42) that received gentle handling daily for the same period. Briefly, the CUS paradigm involved applying, twice daily during the light phase, a random schedule of physical and psychological stressors that ranged in severity. The stressors, which were similar to those utilized in the well-established paradigm of Chaby et al., (2015b), included: 1) confinement to a small rodent box for 4 h, 2) isolation for 4 h, 3) cage tilt for 2 h, 4) shaking and crowding for 1 h, which consisted of 6 rats in a transparent Plexiglas box on an orbital shaker, 5) predatory stress, which consisted of fox odor (Red Fox-P) placed on a cotton swab in a small box, 6) social instability – weekly change of cage partner, 7) tail pinching for 15 min, 8) restraint for 30 min, where rats were placed in cone-shaped plastic bags with an opening for breathing, and 9) 15 min electric foot shock, which consisted of 0.5 mA intensity for 1 s, with an inter-shock interval of 10 s, for a total of 2 min in the electronic shock generator for a 15 min duration. All rats were weighed weekly during the stress treatment, and thereafter. After completion of the stress exposure, during the post-pubertal early adulthood (PND 30–90), rats began a resting period consisting of standard housing where they were undisturbed except for gentle handling twice a week until TBI or sham surgery.

4.3. Controlled cortical impact (CCI) injury

On PND-90, rats weighing 300–325 g underwent a CCI injury as previously described (Kline et al., 2000, 2012). Briefly, surgical anesthesia was induced, and maintained, with inhaled concentrations of 4% and 2% isoflurane, respectively, in 2:1 N2O:O2. After endotracheal intubation, the rats were secured in a stereotaxic frame, ventilated mechanically, and core temperature maintained at 37 ± 0.5°C with a heating blanket. Adhering to aseptic protocol, a midline scalp incision was made, the skin and fascia were reflected to expose the skull, and a craniectomy was made in the right hemisphere (encompassing bregma and lambda and the sagittal and coronal sutures) with a hand-held trephine. The bone flap was removed and the craniectomy was enlarged further to ensure unobstructed penetration of the impact tip (6 mm, flat). Subsequently, the impacting rod was extended, and the impact tip was centered and lowered through the craniectomy until it touched the dura mater, then the rod was retracted, and the impact tip was advanced 2.8 mm farther to produce a brain injury of moderate severity (2.8 mm tissue deformation at 4 m/s). Immediately after the CCI, anesthesia was discontinued, the incision was promptly sutured, and the rats were extubated and assessed for acute neurological outcome. Sham-operated rats underwent all surgical procedures but the impact (Olsen et al., 2012; Bondi et al., 2014; Phelps et al., 2015; Radabaugh et al., 2016; Njoku et al., 2019).

4.4. Acute neurological evaluation

Hind limb reflexive ability was assessed immediately following the cessation of anesthesia and removal from the stereotaxic apparatus by gently squeezing the rats’ paw every 5 s and recording the time to elicit a withdrawal response. Return of the righting reflex was determined by the time required to turn from the supine to prone position three consecutive times. These sensitive neurological indices are used to determine the level of injury severity (Kline et al., 2000; Bondi et al., 2014; Radabaugh et al., 2016).

4.5. Drug administration

Arachidonyl-2′-chloroethylamide (ACEA) was purchased from Tocris Bioscience (Minneapolis, MN) and was prepared daily by dissolving in a 1:1:18 dilution of DMSO, Tween-80, and 0.9% saline, which also served as the vehicle (VEH). ACEA (1 mg/kg) or VEH (1.0 mL/kg) were administered intraperitoneally immediately after TBI or sham injury and once daily for seven days. The dose of ACEA was selected from previous studies showing similar drug preparation and therapeutic range (Caltana et al., 2015; Knowles et al., 2016).

4.6. Body weight

Body weight was monitored through the course of the study as a physiological parameter of stress. Aside from weighing daily during ACEA or VEH administrations, the rats were weighed weekly and prior to any other manipulations for the day.

4.7. Open-field test (OFT)

Assessment in the OFT took place on day-8 after TBI or sham injury. Briefly, the rats were placed individually in a random corner of the arena (36 × 36 × 18 cm) and allowed to explore freely for 5 min. Locomotor activities were recorded using ANY-maze video tracking software. Anxiety-like behavior was quantified as the total time spent in the periphery vs. the center zone during a 5-min session (Jacqmain et al., 2014; Rowe et al., 2016; Manole et al., 2021).

4.8. Novel object recognition (NOR)

On post-operative day 8, 2 h after the OFT session, the NOR test was performed as previously described (Mumby et al., 2002; Ji et al., 2012; Bharne et al., 2016; Fiden et al., 2016). Briefly, the test consisted of three trials where the rat was individually placed in the middle of the open field to freely explore two identical objects – the permanent and decoy (circular blue glass bottles with round red caps placed in two opposite corners of the apparatus 7 cm from the sidewall) for 5 min (T, familiarization trial) before being returned to its home cage. Testing (choice trial, T2) occurred after an inter-trial interval (ITI) of 1 h for the assessment of recognition memory. During T2-ITI, one of the objects (decoy) presented in T1 was replaced by a novel object of different texture and shape (rectangular white plastic bottle with black cap). Total time spent exploring each object during the 5 min trial was recorded using Any-maze video-tracking software. Between each trial, the apparatus and the objects were thoroughly cleaned with ethanol and dried, and the position of the objects (familiar or novel) were randomly changed to avoid place preference. Exploration was operationally defined as when the rat directed its nose toward the object at no more than 2 cm and/or touching the object with its nose. Turning around or climbing on the object was not considered exploratory behavior. The discrimination index (DI) was calculated as the percent ratio between exploration times of the novel and familiar objects: DI = Novel-Familiar/Novel + Familiar.

4.9. Cognitive function: acquisition of spatial learning (time to platform)

Spatial learning was assessed in a MWM task that has been shown to be sensitive to cognitive function/dysfunction after TBI (Kline et al., 2002, 2012; Bondi et al., 2014; Diaz-Chávez et al., 2020; Moschonas et al., 2021). Briefly, the maze consisted of a plastic pool (180 cm diameter; 60 cm high) filled with tap water (26 ± 1°C) to a depth of 28 cm. The maze was in a room with salient visual cues that remained constant throughout the study. The platform was a clear Plexiglas stand (10 cm diameter, 26 cm high) that was positioned 26 cm from the maze wall in the southwest quadrant and held constant for each rat. Assessment of spatial learning consisted of providing a block of four daily trials (4-min inter-trial interval) for five consecutive days (post-operative days 14–18) to locate the platform when it was submerged 2 cm below the water surface. For each daily block of trials, the rats were placed in the pool facing the wall at each of the four possible start locations (north, east, south, west) in a randomized manner. Each trial lasted until the rat climbed onto the platform or until 120 s had elapsed, whichever occurred first. Rats that failed to locate the hidden platform within the allotted time were manually guided to it. All rats remained on the platform for 30 s before being placed in a heated incubator between trials. The times of the 4 daily trials for each rat were averaged and used in the statistical analyses. On day 19 the platform was made visible to the rats by raising it 2 cm above the water surface as a control procedure to determine the contributions of non-spatial factors (e.g., sensory-motor performance, motivation, and visual acuity) on cognitive performance.

4.10. Probe trial (memory retention)

On post-operative day 19 the rats were subjected to a probe trial to test their memory retention (the test was performed before the visible platform to avoid refresher memory). Briefly, the platform was removed from the pool and the rat was provided a single 30-s trial to swim freely (Kline et al., 2010; Radabaugh et al., 2016; Moschonas et al., 2021). The percentage of time spent in the quadrant where the platform was situated during training (i.e., target quadrant) was recorded using Any-maze video-tracking software. Swim speed was also recorded during this testing period. The percent time spent in the target quadrant was used in the statistical analysis.

4.11. Statistical analysis

The data were collected by observers blinded to treatment conditions and were analyzed using Statview 5.0.1 software. The weight gain and MWM data were analyzed by repeated-measures analysis of variance (ANOVA). The acute neurological evaluation data as well as OFT, NOR, probe, visible platform, and swim speed were analyzed by one-factor ANOVAs. When the overall ANOVA revealed a significant effect, the Newman-Keuls post-hoc test was applied to determine specific group differences. The results are expressed as the mean ± standard error of the mean (S.E.M.) and are considered significant when p values are ≤ 0.05.

Supplementary Material

Supplemental Fig. 3. Mean (± S.E.M.) time (s) to locate a hidden and visible platform in the Morris water maze after TBI or SHAM injury for all four Sham groups. There were no differences among the Sham groups (p>0.05) and therefore they were pooled and compared to the TBI groups in Fig 4.

Supplemental Fig. 1. Mean (± S.E.M.) percent-time spent in the center zone in the open-field test for all four Sham groups. There were no differences among the Sham groups (p>0.05) and therefore they were pooled and compared to the TBI groups in Fig 2.

Supplemental Fig. 2. Mean (± S.E.M.) anxiety-like behavior quantified as the total time spent in the periphery vs. the center zone during a 5-min session for all four Sham groups. There were no differences among the Sham groups (p>0.05) and therefore they were pooled and compared to the TBI groups in Fig 3.

Fig. 3.

Mean (± S.E.M.) anxiety-like behavior quantified as the total time spent in the periphery vs. the center zone during a 5-min session. *, #p<0.05 vs. Control + TBI + VEH. While not statistically significant, the CUS + TBI + ACEA group trended (p=0.07) toward greater improvement relative to the Control + TBI + ACEA group (65.2 ± 2.2 vs. 57.9 ± 2.2). No other comparisons were significant.

Acknowledgements

This work was supported, in part, by NIH grants NS084967, HD069620, NS099674, NS113810 (AEK), NS094950, NS099683, NS110609 (COB), the University of Pittsburgh Physicians /UPMC Academic Foundation, and the UMPC Rehabilitation Institute (COB). PBT was a Neurobiology of Neurological Disease T32 Postdoctoral Fellow (NIH NS086749) and EHM is a current Predoctoral Neuroscience T32 Fellow (NIH NS07433).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- Alway Y, Gould KR, McKay A, Johnston L, Ponsford J. (2016). The evolution of post-traumatic stress disorder following moderate-to-severe traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 33:825–831. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andersen SL, Teicher MH. (2008). Stress, sensitive periods and maturational events in adolescent depression. Trends Neurosci. 31:183–191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arain M, Khan M, Craig L, Nakanishi ST. (2015). Cannabinoid agonist rescues learning and memory after a traumatic brain injury. Ann Clin Transl Neurol. 2:289–294. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bai F, Guo F, Jiang T, Wei H, Zhou H, Yin H, Zhong H, Xiong L, Wang Q. (2017). Arachidonyl-2-chloroethylamide alleviates cerebral ischemia injury through glycogen synthase kinase-3β-mediated mitochondrial biogenesis and functional improvement. Mol Neurobiol. 54:1240–1253. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bharne AP, Borkar CD, Bodakuntla S, Lahiri M, Subhedar NK, Kokare DM. (2016). Pro-cognitive action of CART is mediated via ERK in the hippocampus. Hippocampus 26:1313–1327. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bleimeister IH, Wolff M, Lam TR, Brooks DM, Patel R, Cheng JP, Bondi CO, Kline AE. (2019). Environmental enrichment and amantadine confer individual but nonadditive enhancements in motor and spatial learning after controlled cortical impact injury. Brain Res. 1714:227–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bondi CO, Cheng JP, Tennant HM, Monaco CM, Kline AE. (2014). Old dog, new tricks: the attentional set-shifting test as a novel cognitive behavioral task after controlled cortical impact injury. J Neurotrauma 31:926–937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Broomhall LG, Clark CR, McFarlane AC, O’Donnell M, Bryant R, Creamer M, Silove D. (2009). Early stage assessment and course of acute stress disorder after mild traumatic brain injury. J Nerv Ment Dis. 197:178–181. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caltana L, Saez TM, Aronne MP, Brusco A. (2015). Cannabinoid receptor type 1 agonist ACEA improves motor recovery and protects neurons in ischemic stroke in mice. J Neurochem. 135:616–629. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaby LE, Cavigelli SA, Hirrlinger AM, Caruso MJ, Braithwaite VA. (2015a). Chronic unpredictable stress during adolescence causes long-term anxiety. Behav Brain Res. 278:492–495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaby LE, Cavigelli SA, Hirrlinger AM, Lim J, Warg KM, Braithwaite VA. (2015b). Chronic stress during adolescence impairs and improves learning and memory in adulthood. Front Behav Neurosci. 9:327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaby LE, Cavigelli SA, White A, Wang K, Braithwaite VA. (2013). Long-term changes in cognitive bias and coping response as a result of chronic unpredictable stress during adolescence. Front Hum Neurosci. 7:328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen YW, Akad A, Aderogba R, Chowdhury TG, Aoki C. (2018). Dendrites of the dorsal and ventral hippocampal CA1 pyramidal neurons of singly housed female rats exhibit lamina-specific growths and retractions during adolescence that are responsive to pair housing. Synapse 72:e22034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de la Tremblaye PB, O’Neil DA, LaPorte MJ, Cheng JP, Beitchman JA, Thomas TC, Bondi CO, Kline AE. (2018). Elucidating opportunities and pitfalls in the treatment of experimental traumatic brain injury to optimize and facilitate clinical translation. Neurosci Biobehav Rev. 85:160–175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diaz-Chávez A, Lajud N, Roque A, Cheng JP, Meléndez-Herrera E, Valdéz-Alarcón JJ, Bondi CO, Kline AE. (2020). Early life stress increases vulnerability to the sequelae of pediatric mild traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 329:113318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Durand E, Watier L, Fix M, Weiss JJ, Chevignard M, Pradat-Diehl P. (2016). Prevalence of traumatic brain injury and epilepsy among prisoners in France: Results of the Fleury TBI study. Brain Inj. 30:363–372. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dutta S, Sengupta P. (2016). Men and mice: relating their ages. Life Sci. 152:244–248. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eidson LN, deSousa Rodrigues ME, Johnson MA, Barnum CJ, Duke BJ, Yang Y, Chang J, Kelly SD, Wildner M, Tesi RJ, Tansey MG. (2019). Chronic psychological stress during adolescence induces sex-dependent adulthood inflammation, increased adiposity, and abnormal behaviors that are ameliorated by selective inhibition of soluble tumor necrosis factor with XPro1595. Brain Behav Immun. 81:305–316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Farkas J, Kovács LÁ, Gáspár L, Nafz A, Gaszner T, Ujvári B, Kormos V, Csernus V, et al. (2017). Construct and face validity of a new model for the three-hit theory of depression using PACAP mutant mice on CD1 background. Neuroscience 354:11–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fidan E, Lewis J, Kline AE, Garman RH, Alexander H, Cheng JP, Bondi CO, Clark RS et al. (2016). Repetitive mild traumatic brain injury in the developing brain: effects on long-term functional outcome and neuropathology. J Neurotrauma 33:641–651. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Free KE, Greene AM, Bondi CO, Lajud N, de la Tremblaye PB, Kline AE. (2017). Comparable impediment of cognitive function in female and male rats subsequent to daily administration of haloperidol after traumatic brain injury. Exp Neurol. 296:62–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gorzalka BB, Hill MN. (2009). Integration of endocannabinoid signaling into the neural network regulating stress-induced activation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal axis. Curr Top Behav Neurosci. 1:289–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gouirand AM, Matuszewich L. (2005). The effects of chronic unpredictable stress on male rats in the water maze. Physiol Behav. 86:21–31. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hawley DF, Morch K, Christie BR, Leasure JL. (2012). Differential response of hippocampal subregions to stress and learning. PLoS One. 7:e53126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ilie G, Adlaf EM, Mann RE, Ialomiteanu A, Hamilton H, Rehm J, Asbridge M, Cusimano MD. (2015). Associations between a history of traumatic brain injuries and current cigarette smoking, substance use, and elevated psychological distress in a population sample of canadian adults. J Neurotrauma 32:1130–1134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacqmain J, Nudi ET, Fluharty S, Smith JS. (2014). Pre and post-injury environmental enrichment effects functional recovery following medial frontal cortical contusion injury in rats. Behav Brain Res. 275:201–211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jenniches I, Ternes S, Albayram O, Otte DM, Bach K, Bindila L, Michel K, Lutz B, Bilkei-Gorzo A, Zimmer A. (2016). Anxiety, stress, and fear response in mice with reduced endocannabinoid levels. Biol Psychiatry 79:858–868. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ji J, Kline AE, Amoscato A, Samhan-Arias AK, Sparvero LJ, Tyurin VA, Tyurina YY, Fink B et al. , (2012). Lipidomics identifies cardiolipin oxidation as a mitochondrial target for redox therapy of brain injury. Nat Neurosci. 15:1407–1413. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline AE, Massucci JL, Zafonte RD, Dixon CE, DeFeo JR, Rogers EH. (2007). Differential effects of single versus multiple administrations of haloperidol and risperidone on functional outcome after experimental brain trauma. Crit. Care Med. 35:919–924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline AE, McAloon RL, Henderson KA, Bansal UK, Ganti BM, Ahmed RH, Gibbs RB, Sozda CN. (2010). Evaluation of a combined therapeutic regimen of 8-OH-DPAT and environmental enrichment after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 27: 2021–2032. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline AE, Olsen AS, Sozda CN, Hoffman AN, Cheng JP. (2012). Evaluation of a combined treatment paradigm consisting of environmental enrichment and the 5-HT1A receptor agonist buspirone after experimental traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 29:1960–1969. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kline AE, Yan HQ, Bao J, Marion DW, Dixon CE. (2000). Chronic methylphenidate treatment enhances water maze performance following traumatic brain injury in rats. Neurosci. Lett. 280:163–166. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knowles MD, de la Tremblaye PB, Azogu I, Plamondon H. (2016). Endocannabinoid CB1 receptor activation upon global ischemia adversely impact recovery of reward and stress signaling molecules, neuronal survival and behavioral impulsivity. Prog Neuropsychopharmacol Biol Psychiatry 66:8–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Leishman E, Murphy M, Mackie K, Bradshaw HB. (2018). Δ9-Tetrahydrocannabinol changes the brain lipidome and transcriptome differentially in the adolescent and the adult. Biochim Biophys Acta Mol Cell Biol Lipids 1863:479–492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu QR, Canseco-Alba A, Liang Y, Ishiguro H, Onaivi ES. (2020). Low Basal CB2R in Dopamine neurons and microglia influences cannabinoid tetrad effects. Int J Mol Sci. 21:9763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Jia J, Niu W, Jiang T, Zhai Q, Yang L, Bai F, Wang Q, Xiong L. (2015). Mitochondrial CB1 receptor is involved in ACEA-induced protective effects on neurons and mitochondrial functions. Sci Rep. 5:12440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ma L, Niu W, Yang S, Tian J, Luan H, Cao M, Xi W, Tu W, Jia J, Lv J. (2018). Inhibition of mitochondrial permeability transition pore opening contributes to cannabinoid type 1 receptor agonist ACEA-induced neuroprotection. Neuropharmacology 135:211–222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Magid L, Heymann S, Elgali M, Avram L, Cohen Y, Liraz-Zaltsman S, Mechoulam R, Shohami E. (2019). Role of CB2 receptor in the recovery of mice after traumatic brain injury. J Neurotrauma 36:1836–1846. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manole MD, Hook MJA, Nicholas MA, Nelson BP, Liu AC, Stezoski QC, Rowley AP, Cheng JP et al. (2021). Preclinical neurorehabilitation with environmental enrichment confers cognitive and histological benefits in a model of pediatric asphyxial cardiac arrest. Exp Neurol. 335:113522. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McLaughlin RJ, Hill MN, Dang SS, Wainwright SR, Galea LA, Hillard CJ, Gorzalka BB. (2013). Upregulation of CB₁ receptor binding in the ventromedial prefrontal cortex promotes proactive stress-coping strategies following chronic stress exposure. Behav Brain Res. 237:333–337. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mechoulam R, Shohami E. (2007). Endocannabinoids and traumatic brain injury. Mol Neurobiol. 36:68–74. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morena M, Patel S, Bains JS, Hill MN. (2016). Neurobiological interactions between stress and the endocannabinoid system. Neuropsychopharmacology 41:80–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moschonas EH, Leary JB, Memarzadeh K, Bou-Abboud CE, Folweiler KA, Monaco CM, Cheng JP, Kline AE, Bondi CO. (2021). Disruption of basal forebrain cholinergic neurons after traumatic brain injury does not compromise environmental enrichment-mediated cognitive benefits. Brain Res. 1751:147175. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mumby DG, Gaskin S, Glenn MJ, Schramek TE, Lehmann H. (2002). Hippocampal damage and exploratory preferences in rats: memory for objects, places, and contexts. Learn Mem. 9:49–57. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Njoku I, Radabaugh HL, Nicholas MA, Kutash LA, O’Neil DA, Marshall IP, Cheng JP, Kline AE, Bondi CO. (2019). Chronic treatment with galantamine rescues reversal learning in an attentional set-shifting test after experimental brain trauma. Exp. Neurol. 315:32–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Olsen AS, Sozda CN, Cheng JP, Hoffman AN. Kline AE. (2012). Traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive and histological deficits are attenuated by delayed and chronic treatment with the 5-HT1A receptor agonist buspirone. J Neurotrauma 29:1898–1907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Palomba L, Motta A, Imperatore R, Piscitelli F, Capasso R, Mastroiacovo F, Battaglia G, Bruno V, Cristino L, Di Marzo V. (2020). Role of 2-Arachidonoyl-Glycerol and CB1 receptors in orexin-A-mediated prevention of oxygen-glucose deprivation-induced neuronal injury. Cells 9:1507. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paus T, Keshavan M, Giedd JN. (2008). Why do many psychiatric disorders emerge during adolescence? Nat Rev Neurosci. 9:947–957. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pawley LC, Hueston CM, O’Leary JD, Kozareva DA, Cryan JF, O’Leary OF, Nolan YM. (2020). Chronic intrahippocampal interleukin-1β overexpression in adolescence impairs hippocampal neurogenesis but not neurogenesis-associated cognition. Brain Behav Immun. 83:172–179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phelps TI, Bondi CO, Ahmed RH, Olugbade YT, Kline AE. (2015). Divergent long-term consequences of chronic treatment with haloperidol, risperidone, and bromocriptine on traumatic brain injury-induced cognitive deficits. J Neurotrauma 32:590–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabner J, Gottlieb S, Lazdowsky L, LeBel A. (2016). Psychosis following traumatic brain injury and cannabis use in late adolescence. Am J Addict. 25:91–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Radabaugh HL, Carlson LJ, O’Neil DA, LaPorte MJ, Monaco CM, Cheng JP, de la Tremblaye PB, Lajud M. et al. , (2016). Abbreviated environmental enrichment confers neurobehavioral, cognitive, and histological benefits in brain-injured female rats. Exp Neurol. 286:61–68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reich CG, Iskander AN, Weiss MS. (2013). Cannabinoid modulation of chronic mild stress-induced selective enhancement of trace fear conditioning in adolescent rats. J Psychopharmacol. 27:947–955. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rowe RK, Ziebell JM, Harrison JL, Law LM, Adelson PD, Lifshitz J. (2016). Aging with traumatic brain injury: effects of age at injury on behavioral outcome following diffuse brain injury in rats. Dev Neurosci. 38:195–205. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruehle S, Rey AA, Remmers F, Lutz B. (2012). The endocannabinoid system in anxiety, fear memory and habituation. J Psychopharmacol. 26:23–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Russell AL, Tasker JG, Lucion AB, Fiedler J, Munhoz CD, Wu TJ, Deak T. (2018). Factors promoting vulnerability to dysregulated stress reactivity and stress-related disease. J Neuroendocrinol. 30(10):e12641. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rusznák K, Csekő K, Varga Z, Csabai D, Bóna Á, Mayer M, Kozma Z, Helyes Z, Czéh B. (2018). Long-term stress and concomitant marijuana smoke exposure affect physiology, behavior and adult hippocampal neurogenesis. Front Pharmacol. 9:786. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santori A, Colucci P, Mancini GF, Morena M, Palmery M, Trezza V, Puglisi-Allegra S, Hill MN, Campolongo P. (2019). Anandamide modulation of circadian- and stress-dependent effects on rat short-term memory. Psychoneuroendocrinology 108:155–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schurman LD, Lichtman AH. (2017). Endocannabinoids: a promising impact for traumatic brain injury. Front Pharmacol. 8:69. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sengupta P (2013). The laboratory rat: relating its age with human’s. Int J Prev Med. 4:624–630. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shohami E, Cohen-Yeshurun A, Magid L, Algali M, Mechoulam R. (2011). Endocannabinoids and traumatic brain injury. Br J Pharmacol. 163:1402–1410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vrechi TA, Crunfli F, Costa AP, Torrão AS. (2018). Cannabinoid receptor type 1 agonist ACEA protects neurons from death and attenuates endoplasmic reticulum stress-related apoptotic pathway signaling. Neurotox Res. 33:846–855. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Whittle S, Lichter R, Dennison M, Vijayakumar N, Schwartz O, Byrne ML, Simmons JG, Yücel M, et al. (2014). Structural brain development and depression onset during adolescence: a prospective longitudinal study. Am J Psychiatry. 171:564–571. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang S, Hu B, Wang Z, Zhang C, Jiao H, Mao Z, Wei L, Jia J, Zhao J. (2020). Cannabinoid CB1 receptor agonist ACEA alleviates brain ischemia/reperfusion injury via CB1-Drp1 pathway. Cell Death Discov. 6:102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ye Y, Yao S, Wang R, Fang Z, Zhong K, Nie L, Zhang Q. (2019). PI3K/Akt/NF-κB signaling pathway regulates behaviors in adolescent female rats following with neonatal maternal deprivation and chronic mild stress. Behav Brain Res. 362:199–207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang Y, Shao F, Wang Q, Xie X, Wang W. (2017). Neuroplastic correlates in the mPFC underlying the impairment of stress-coping ability and cognitive flexibility in adult rats exposed to chronic mild stress during adolescence. Neural Plast. 2017:9382797. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zimmermann T, Maroso M, Beer A, Baddenhausen S, Ludewig S, Fan W, Vennin C, Loch S, Berninger B, Hofmann C, Korte M, Soltesz I, Lutz B, Leschik J. (2018). Neural stem cell lineage-specific cannabinoid type-1 receptor regulates neurogenesis and plasticity in the adult mouse hippocampus. Cereb Cortex 28:4454–4471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental Fig. 3. Mean (± S.E.M.) time (s) to locate a hidden and visible platform in the Morris water maze after TBI or SHAM injury for all four Sham groups. There were no differences among the Sham groups (p>0.05) and therefore they were pooled and compared to the TBI groups in Fig 4.

Supplemental Fig. 1. Mean (± S.E.M.) percent-time spent in the center zone in the open-field test for all four Sham groups. There were no differences among the Sham groups (p>0.05) and therefore they were pooled and compared to the TBI groups in Fig 2.

Supplemental Fig. 2. Mean (± S.E.M.) anxiety-like behavior quantified as the total time spent in the periphery vs. the center zone during a 5-min session for all four Sham groups. There were no differences among the Sham groups (p>0.05) and therefore they were pooled and compared to the TBI groups in Fig 3.