Abstract

Objective:

Impairment in consciousness is a debilitating symptom during and after seizures, however its mechanism remains unclear. Limbic seizures have been shown to spread to arousal circuitry to result in a ‘network inhibition’ phenomenon. However, prior animal models studies did not relate physiological network changes to behavioral responses during or following seizures.

Methods:

Focal-onset limbic seizures were induced while rats were performing an operant conditioned behavioral task requiring response to an auditory stimulus to quantify how and when impairment of behavioral response occurs. Correct responses were rewarded with sucrose. Cortical and hippocampal electrophysiology measured by local field potential recordings was analyzed for changes in low and high frequency power in relation to behavioral responsiveness during seizures.

Results:

As seen in patients with seizures, ictal (p<0.0001) and postictal (p=0.0015) responsiveness was variably impaired. Analysis of cortical and hippocampal electrophysiology revealed that ictal (p=0.002) and postictal (p=0.009) frontal cortical low-frequency 3–6 Hz power was associated with poor behavioral performance. In contrast, the hippocampus showed increased power over a wide frequency range during seizures, and suppression post-ictally neither of which were related to behavioral impairment.

Significance:

These findings support prior human studies of temporal lobe epilepsy as well as anesthetized animal models suggesting that focal limbic seizures depress consciousness through remote network effects on the cortex, rather than through local hippocampal involvement. By identifying the cortical physiological changes associated with impaired arousal and responsiveness in focal seizures these results may help guide future therapies to restore ictal and postictal consciousness, improving quality of life for people with epilepsy.

Keywords: focal seizures, epilepsy, consciousness, sleep, slow waves, frontal cortex

Introduction

Consciousness is an actively maintained neural process1–3. Seizures pose a clinically-relevant context in which the consciousness system may be transiently perturbed4, 5. Impaired conscious awareness greatly affects morbidity, mortality and quality of life for people with epilepsy6, 30–40% of whom remain refractory to medical therapy7. Consequences include sudden unexplained death in epilepsy (SUDEP), traumatic accidents (falls, motor vehicle accidents)8, and impaired performance at work or school. Investigating mechanism of impaired consciousness in epilepsy would be greatly aided by valid animal models.

Characteristics of focal limbic seizures, the type to most commonly affect consciousness, include: (1) variable impairment in behavior9; (2) high-amplitude delta oscillations in association cortices10; and (3) hemodynamic increases in upper brainstem/medial thalamus and decreases in association cortices11. The ‘network inhibition’ hypothesis12, supported by evidence from our animal model work13, 14, proposes focal limbic seizures impair level of consciousness by inhibiting subcortical arousal systems resulting in low-frequency cortical oscillations14–19. However, our prior studies dissecting these mechanisms were performed under light anesthesia, which can affect electrophysiology and limit behavioral study. Recent work in a mouse awake model of focal limbic seizures demonstrates impaired behavioral responses and cortical slowing20–22, but does not allow direct comparison to previous mechanistic studies done mainly in rats. To overcome these limitations, we developed an awake-behaving rat seizure model with dorsal hippocampal electrical stimulation to induce focal-onset limbic seizures while performing an operant conditioned reward-driven task. The model enables assessment of peri-ictal behavioral reactivity in direct relation to changes in pre-frontal cortical and hippocampal physiology within the confines of our task paradigm.

Methods

Animals

All procedures were approved by the Yale Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee. Adult female Sprague-Dawley rats weighing 180–300 grams (Charles River Laboratories) were used. We used female animals because our goal was to study focal limbic seizures without secondary generalization, and previous work showed that focal seizures are obtained more easily in females than in males23, 24

Surgery and electrode implantation

We implanted chronic hippocampal and frontal cortical electrodes as previously described25, 26. Hippocampal electrodes induced and recorded seizure onset and offset. Frontal electrodes recorded cortical slow waves13. For implants, animals were anesthetized with intramuscular 100 mg/kg ketamine (Henry Schein Animal Health) and 10 mg/kg xylazine (Lloyd Laboratories, AnaSed). Stereotaxic coordinates are reported as electrode tip locations relative to bregma. A bipolar electrode (PlasticsOne, E363-2-2TW) cut to 20 mm, with tips separated by 1 mm in the coronal plane was implanted in right lateral orbitofrontal cortex (AP +4.2; ML +2.2; SI −3.8 mm)27. A bipolar electrode with insulation shaved to 0.5 mm and tips separated by 1 mm in the coronal plane was implanted in the left dorsal hippocampus (HC) (AP −3.8; ML −2.5; SI −3.0 mm)27. Electrodes were cemented to three anchoring screws (PlasticsOne, 0–80×3/32) and a ground screw (PlasticsOne, E363–20) with dental cement (Lang Dental Manufacturing). Electrode pins were placed into two six-pin pedestals (PlasticsOne, MS363). Animals recovered for 1 week prior to behavioral training.

Food restriction and behavioral training

Food restriction was achieved with 36g/kg of chow per day until reaching 85% of their initial body weight. Animals were then trained to lick a spout in response to an auditory ‘clicking’ stimulus.

We used an electrically-shielded and sound-attenuated chamber (Med Associates, ENV-018MD-EMS) containing a plexiglass behavioral operant chamber (Med Associates, ENV-008-CT) equipped with a camera, light, fan, speaker, and spout for sucrose reward delivery affixed to a photobeam lickometer (Med Associates, CT-ENV-251L-X4) as previously described (Figure 1A)28. A syringe pump delivered 60 μl of 10% sucrose solution reward. Sound stimuli were 2s, 100 Hz trains of 3 ms clicks at 75 dB, produced by an audio generator (ANL-926, MedAssociates) using a customized script in MED-PC. The script also generated TTL timing pulses for licks and sound events sent to an analog-to-digital converter (CED 1401) to record all behavioral and electrophysiological data on a single time line.

Figure 1.

Lick task in response to an auditory stimulus. (A) Rats were trained to respond to a 2 second, 75dB, 100 Hz clicking sound in an operant chamber equipped with behavioral control, electrophysiology recording, and video recording. (B) Behavior and electrophysiology were recorded and controlled in an automated fashion with multi-modal data acquisition. “Behav control & data acquisition” is a dedicated computer with Med-PC and Spike2 software; “ADC” is analog-to-digital converter. (C) Example behavior from one animal through the 3 stages of training; first the animal is freely provided sucrose during sound presentation; next the animal had to lick within 5 seconds of a sound in order to receive a sucrose reward; lastly, the animal must lick within 5 seconds, but once the reward is dispensed, it had 10 seconds in order to consume the reward, any licks outside of this window will put the animal into a 30 second time-out from any sound stimuli. Stimuli occurred every 10–15 seconds. (D) Group data of lick response time courses show that lick rates rose consistently with sound and reward in all three stages. After the final stage of training, baseline lick rate was 0 and rose specifically with sound stimulus. Time courses show mean and SEM.

Auditory stimuli were presented at random 10–15 second intervals. The first lick following the stimulus was considered the response. Training consisted of three stages: (1) ‘Free Reward’ stage, in which a sucrose reward was presented during the auditory stimulus regardless of a lick response; (2) ‘Sound-Reward’ stage, in which the animal was required to lick the spout within 5 seconds following the onset of auditory stimulus to receive the reward; (3) ‘Sound-Reward with Timeout’ stage, in which the animal went into a 30s time-out period if it licked the spout at any time outside of the 5-second reward window or outside the first 10s following receipt of a reward. The timeout period was accompanied by a non-noxious visual stimulus with 1 Hz flashing (500ms on, 500ms off) of the enclosure light to indicate a separate period than the non-timeout inter-stimulus period. For each training stage, ≥70–75% correct response rate for two successive training sessions was needed to proceed to the next training stage, or to complete training. Trials where the animal licked within 5 seconds of the auditory stimulus were considered correct responses (‘hits’), while those in which they did not were ‘misses’.

Electrophysiology and video recording procedures

Once training was completed, electrophysiological recordings were performed in the shielded behavioral chambers (Figure 1B), as previously described28. Animals were connected from the head-mounted pedestals to a commutator (PlasticsOne), headstages (10x gain), and amplifiers (A-M Systems, Model 1800, 1000x gain), and local field potential (LFP) recordings obtained at 1–500 Hz, with 60 Hz notch filter. LFP data underwent analog-to-digital conversion (Power 1401, Cambridge Electronics Design) at 1000 Hz and were recorded with simultaneous video of rat behavior using Spike2 (Figure 1B).

Focal-onset limbic seizures were induced as previously described13, with a 2 s train of 60 Hz square biphasic (1ms per phase) current pulses to the hippocampus using an isolated stimulator (A-M Systems, Model 2100). Initial current amplitude to produce focal-onset seizures in the awake state was typically 50 microamps, which is smaller than in previous anesthetized experiments. If a seizure was not produced, current was increased by 25 microamps and re-attempted after ≥20 minutes. Generalization was defined based on propagated polyspike activity to frontal recording electrodes or behavioral Racine class ≥3, and generalized seizures (including generalized-tonic clonic seizures) were excluded from analysis. All hippocampal stimulations were less than 200 microamps except for 1 included focal seizure requiring 500 microamps stimulation. As only hippocampal and frontal electrodes were placed, a limitation of these experiments is that potential seizure activity at other cortical or subcortical brain areas was not measured.

Histology

After completion of experiments, animals were euthanized and then perfused with 4% paraformaldehyde, brains were post-fixed for three days, and slices cut at 100 μm, stained with cresyl violet to confirm electrode location within the targeted regions of dorsal hippocampus and lateral orbitofrontal cortex as described previously26, 29.

Data analysis and statistics

Analysis time epochs were defined based on hippocampal LFP recordings as follows: Baseline – 180s just prior to seizure initiation; Ictal – first 60s of induced seizure (or until end of seizure if ictal period <60s); Postictal – first 60s immediately following seizure end; and Recovery – a 180s period starting 300s following seizure end. If due to movement artifact or interruption of recordings, the full periods of behavioral and electrophysiological data were not available, then available data were used.

Behavioral analysis was performed for each epoch. Correct response rate (hit rate) was calculated as number of hits in an epoch divided by number of sound stimuli presented. Response latency was measured as time from sound stimulus onset to time of first lick; lick rate timecourse (Figures 1, 2) was calculated as number of licks per 1s interval in the 5s preceding and 10s following a sound. The timecourse of hit rate (Figure 3) was generated by binning stimuli across seizures into 10s windows in each epoch (Baseline, Ictal, Postictal, and Recovery); the hit rate was defined by number of hits divided by number of stimuli in each 10s window.

Figure 2.

Seizures variably impaired peri-ictal behavior. (A) Example of a focal limbic seizure which was induced with 2s dorsal hippocampal stimulation while the animal was performing the ‘sound-reward with timeout’ task. (B) 5s insets of Baseline, Ictal, Postictal and Recovery periods show that Ictal low-frequency oscillations in the lateral orbitofrontal cortex associated with misses. Ictal and Postictal performance was significantly decreased compared to the Baseline period. (C) The characteristics of hit and miss behavior with seizures show that the characteristics of the lick responses were not different amongst hits in the different time epochs, but were significantly delayed and depressed amongst misses. Time courses show mean and SEM.

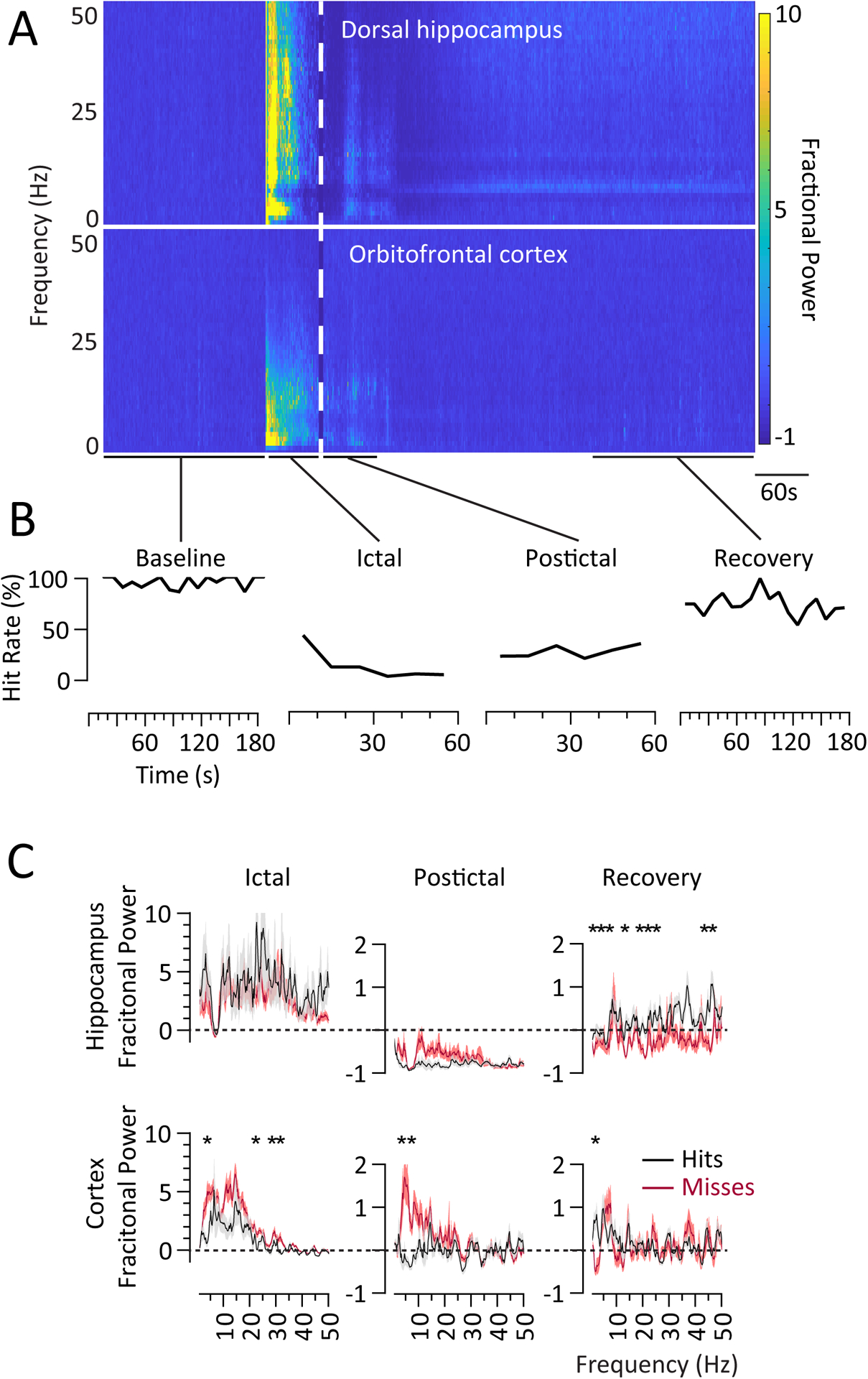

Figure 3.

Low frequency cortical oscillations was associated with Ictal and Postictal misses. (A) Time-frequency plots of fractional power change from averaged Baseline power show widespread increases in Ictal hippocampal power (except at 7–9 Hz, theta), and increases below 25 Hz (notably at <10 Hz) in cortex. The Postictal state shows initially marked suppression in hippocampus, followed by some persistent power elevations in hippocampus and cortex. Leading up to and during the Recovery period, the hippocampus shows theta and broadband gamma power increases with cortical state resembling Baseline. (B) Time course of hit rates for the corresponding epochs. (C) Hippocampal and cortical spectrograms in the 2s surrounding each sound event show that in the Ictal and Postictal periods, there is greater low frequency power in misses, with no differences in hippocampal signals. In the Recovery period, there are many distributed frequencies with significant relative increases in hippocampus power amongst hits, but only at 1–3Hz in the cortex. *p<0.05, Bonferroni-corrected t-test performed on 3Hz bins.

We also analyzed cortical and hippocampal LFP in each epoch. Power spectra were obtained with the spectrogram function in MATLAB (MathWorks). Fractional power was calculated in 1 s bins and for each 1 Hz frequency band as power (in μV2) minus the first 60 seconds of Baseline power, divided by the first 60 seconds of Baseline power. Artifacts, occurring uncommonly but thought to arise from motion, were defined as values exceeding 3 standard deviations above the mean for a specific time (1s bin) and frequency (1 Hz bin) across all seizures; artifact values were rejected and the remainder of values were analyzed. The average of fractional power time-frequency plots were generated by averaging fractional power for corresponding time and frequency values across seizures.

To derive electrophysiological correlates to ‘hit’ or ‘miss’ response behavior, we analyzed cortical and hippocampal LFP waveforms from 1s prior to 1s after the sound onset for each epoch and in each seizure. Sound stimuli in which the analysis window (sound onset time ±1s) was either outside of the bounds of the recording or which included the 2 s hippocampal stimulation (seizure induction) were excluded. Similar to timecourse analysis, artifacts were rejected as values exceeding 3 standard deviations above the mean for specific time- and frequency-bin, again using a 1s and 1Hz window sizes. Fractional power was calculated in a similar fashion as already described, by subtracting the mean Baseline hit power values for each 0.25 Hz frequency window from power values for the corresponding 0.25 Hz and 1s windows for the Ictal, Postictal, and Recovery periods, and then dividing by the corresponding Baseline power values (Figure 3).

Statistics were performed with Prism (GraphPad, v8.3) and MATLAB, with significance threshold p<0.05. Behavioral and electrophysiological data were presented as averages across seizures (Figures 3A, B) or across sound events (Figures 1D, 2C, 3C). Very similar results were found when averaging within animal first (data not shown). For statistical analysis of hit and miss power spectra (Figure 3C), fractional power values were averaged in bins of 3 Hz. Appropriate single groups were compared using an unpaired Student’s t-test with Bonferroni-Holm correction for multiple comparisons. Analysis of three or more groups together were compared with a one-way ANOVA followed by post hoc Tukey test. Correlation analysis was by Pearson correlation followed by a t-test. Means and errors are presented as mean ± SEM and reported p-values are adjusted for multiple comparisons.

Results

Animals were trained to reliably respond to auditory stimulus

Quantification of impaired behavioral response required a frequently occurring task with an expected response from a conscious animal. Our task was designed to continuously assess responsiveness based on presence of a lick to auditory stimuli and response latency to the first lick. The training paradigm consisted of 3 phases (see Methods for details). Average training times for each stage were as follows (mean ± SEM, n=8 animals): ‘Free Reward’ 2.02h ± 0.36h; ‘Sound-Reward’ 7.11h ± 1.41h; ‘Sound-Reward with Timeout’ 20.59h ± 4.65h. The animal lick rate rose specifically after the ‘Sound-Reward with Timeout’ stage (Figure 1C, D). After training through the ‘Free Reward’, ‘Sound-Reward’, and ‘Sound-Reward with Timeout’ stages, animals were able to obtain 78.99 ± 6.83% correct response rate and 1.58 ± 0.19s hit response latency.

Task performance was variably impaired during focal seizures

Focal-onset limbic seizures were induced with a 2s hippocampal stimulation (Figure 2A, B). We excluded secondarily generalized seizures based on propagation of polyspike activity to frontal cortex13 or Racine class ≥3 tonic-clonic movements. Of 78 seizures in 8 animals, 5 seizures (6%) were excluded by these criteria. Duration of included seizures was 96.01s ± 4.94 (73 seizures, mean ± SEM).

Correct response rate (‘hit rate’) decreased significantly from 93.66 ± 1.16% in Baseline period to 22.28 ± 5.39% during the Ictal period (p<0.0001), 33.27 ± 8.73% in the Postictal period (p=0.0015), 81.44 ± 5.74% in the Recovery period (p=0.34) (one-way repeated-measures Bonferroni-corrected ANOVA, compared to Baseline). In the Ictal period, 27 seizures (37%) of seizures had a hit rate of 0% and an average seizure duration of 92.53s, while 9 seizures (12.3%) had hit rate of 100% and significantly shorter duration of 51.93s (t=2.31; p=0.04). Longer seizures were significantly correlated with worse ictal (r=−0.31, p=0.008) and post-ictal (r=−0.56, p<0.0001) hit rates, suggesting a duration-dependent component to ictal and post-ictal pathophysiology. Interestingly, hits during the ictal period occurred an average of 18.53 ± 3.043s earlier than misses (t=6.089, df=52.49, p<0.001), suggesting that behavioral performance becomes progressively worse during the ictal period. There was no significant correlation between seizure duration and hit rate in the Baseline (r=−0.11, p=0.34) or Recovery (r=−0.02, p=0.89) periods.

The occurrence of hits with the expected associated post-reward licking behavior during a seizure suggested that seizures did not always directly impair the ability to respond by impairing sensory perception, processing of the learned behavior, or motor behavior. To examine this further, the timecourse of lick behavior was generated for 5s prior and 10s after each sound stimulus for hits and for misses (Figure 2C). Interestingly, the licking behavior for hits in the Ictal and Postictal periods remained similar to Baseline (Figure 2C). Thus, among hits the time to first lick, or the response latency among hits was not significantly different between Baseline and Ictal, Postictal, or Recovery periods (one-way ANOVA, F=0.85, p=0.48). However, Ictal misses were significantly delayed compared to Baseline (t=3.09, p=0.02). Analysis of peak lick rate and peak lick rate latencies for hits were not significantly different amongst Baseline, Ictal, Postictal, and Recovery periods. However for misses, peak lick rates were significantly decreased during Ictal (t=4.40, p=0.002) and Postictal (t=3.42, p=0.02) periods.

In summary, the peri-ictal behavioral data suggested that correct responses (hits) can sometimes occur during and following seizures (as seen in Figure 3B), and when these responses occur their characteristics are similar to those that occur at Baseline pre-seizure (as seen in Figure 2C). Subsequent electrophysiological analysis focused on parsing cortical and hippocampal signal features specific to spared versus impaired behavioral responses to the auditory stimulus.

Behavioral impairment associated with cortical and hippocampal physiology in Ictal, Postictal, and Recovery Periods

The timecourse of peri-ictal hippocampal and cortical signals showed electrophysiological features in the Ictal, Postictal and Recovery periods (as compared to the Baseline) that correlated with behavioral impairment (Figure 3A, see also Figure 2B). In the Ictal period, there were expectedly widespread dramatic increases in hippocampal power. Beginning about 15s after seizure induction, there was a notable decrease in the 7–8 Hz theta frequency range. In the cortex, the ictal power increase was predominantly limited to lower frequencies below 25 Hz (Figure 3A). The frequencies that showed increased power and the magnitude of the increases were different between the cortex and hippocampus, suggesting that the observed cortical response was not solely seizure propagation. Behaviorally, the consistently high hit rate of the Baseline period (86%−100%) dropped to 44% by 10s after seizure start, 13% by 30s, and then 3% at 40s (Figure 3B).

Postictally, there was a background of diffuse hippocampal suppression of activity below Baseline, along with persistent 6–9Hz suppression (Figure 3A). Cortical power was reduced compared to the Ictal period but remained slightly above Baseline. The Postictal hit rate was stably decreased compared to Baseline (timecourse ranging from 21% to 35%; p=0.0015); the Postictal hit rate was not significantly improved from Ictal impairment (p=0.90). During the Recovery period behavior continued to improve, while the hippocampal signal gradually resolved over a much longer timeframe as compared to the cortical signal, with a notably specific hippocampal rebound of 6–9 Hz (theta) power and more diffuse and less apparent power elevation from 12–50 Hz (beta-low gamma) (Figure 3A). There was not a similar coincident rebound in the cortical LFP.

We were interested in relating behavioral responses during and following seizures to alterations in cortical and hippocampal physiology. Segmenting the data within each period (i.e., Baseline, Ictal, Postictal, and Recovery) to the 2s centered around each auditory stimulus, we noted differences in hippocampal and cortical physiology directly relatable to hits versus misses (Figure 3C). At Baseline, there were no significant frequency power differences in the cortical signal between hits (n=210) and the rare misses occurring under normal conditions (n=9) (data not shown). In the Ictal period, cortical power below 25 Hz was overall increased for both hits and misses, although misses had significantly higher power than hits in 3–6 (p=0.002), 21–24 (p=0.002), 27–30 (p=0.03), and 30–33 (p=0.01) Hz ranges (n = hits: 23; misses: 160; Bonferroni-corrected t-test) (Figure 3C). In contrast, although Ictal hippocampal LFP signals were increased across a broad frequency range, there were no frequencies with significant differences in power between hits and misses. Again seen was an Ictal dip in hippocampal theta frequency (~8Hz) power slightly below baseline for both hits and misses.

In the Postictal period, cortical power was elevated in low frequencies for misses compared to hits (3–6 Hz, p=0.009; 7–9 Hz, p<0.001) (Figure 3C). In contrast to the Ictal Period, in the Postictal period the hippocampus showed a marked suppression of power across a broad frequency range. However, like the Ictal period there were no significant differences in Postictal hippocampal power between hits (n=49) and misses (n=116) at any frequency (Figure 3C). This stark contrast emphasized that cortical influence, especially of low frequencies, was likely correlated with Ictal and Postictal impaired behavioral responses.

During the Recovery period overall power returned closer to Baseline (zero point in the plots) for both the hippocampus and cortex. However, in the hippocampus misses (n=52) had lower power compared to hits (n=179) across distributed frequencies (1–9, 12–15, 18–27, 36–39, 42–45, and 45–48 Hz), possibly residual from the broadband suppressed power seen in the hippocampus postically (Figure 3C). In the cortex, power was the same for hits and misses at most frequencies and similar to Baseline, although 1–3 Hz power was higher in hits compared to misses.

Discussion

We correlated impaired behavior during an operant conditioning auditory response task with orbitofrontal and hippocampal electrophysiology in relation to focal limbic seizures. Induced limbic seizures variably decreased the correct response rate in the Ictal and Postictal periods. However, when correct responses did occur, they had normal appearing latency. In the Ictal and Postictal periods, incorrect responses were associated with elevated cortical low-frequency power. Our results fit into the context of the ‘network inhibition’ hypothesis associating peri-ictal subcortical arousal suppression with low frequency cortical synchrony and behavioral impairment4.

Variable task behavior impairment in our seizure model

In 2017, the seizure classification guidelines were revised to consider seizures as focal seizures with or without awareness as a surrogate marker of consciousness30. Patients with partial seizures showed bimodal impairment of the Responsiveness in Epilepsy Scale31. Chronic and acute animal studies of focal temporal seizures have evaluated peri-ictal behavior with the Racine scale of qualitative semiology, behavioral arrest, and have also related ictal physiology in relation to a range of memory and neuropsychiatric comorbidities15, 20, 21, 26, 29, 32–35. In the awake behaving rodent model presented, we have recapitulated the variable Ictal and Postictal impairments in responsiveness observed in patients. Similar to patients, during focal seizures response behavior was sometimes impaired and sometimes fully spared31.

Cortical low-frequency oscillations with altered peri-ictal responsiveness

We found that cortical lower-frequency (<10 Hz) oscillations were most consistently associated with impaired responses in both the Ictal and Postictal periods. Increased cortical low-frequency power has been previously associated with depressed responsiveness in deep sleep, coma, anesthesia, and seizures4, 36 while decreased low frequency power is associated with conscious experience37. Prior studies showed improvements from peri-ictal behavioral arrest associated with abolition of cortical delta waves26, 29, but the cognitive value to this improvement was unclear because no specific behavioral task was performed. More recently, poor performance in the postictal period on shock-avoidance and spontaneous licking tasks was associated with cortical slow wave activity; intralaminar thalamic stimulation abolished postictal cortical slow waves and improved postictal responses28. The distributed frequencies and large magnitude of Ictal power elevations we observed in the cortex for both hits and misses supports the notion that a threshold of cortical low-frequency waves may correlated but is not causative of behavior38. After a seizure had resolved, the association of cortical low-frequency power with Postictal misses remained. Dissipation of cortical low-frequency waves in the transition from Postictal to Recovery is similar to that noted in emergence from anesthesia39.

Hippocampal power changes during seizures and recovery

We found increases in ictal hippocampal power across the spectrum, in both hits and misses. Similarly, behavior was completely spared or completely impaired in approximately 50% of seizures despite the relatively uniform increase in hippocampal power. Postictally, there were broadband hippocampal power decreases again present both in hits and misses. Impairments associated with limbic seizures extend beyond the functions traditionally ascribed to the hippocampus40–42. In our model, seizure duration was inversely correlated with Ictal and Postictal hit rates, suggesting that longer seizures are more likely to have more severe effects through propagation to remote brain networks. Based on prior work in animal and human focal temporal lobe seizures14, 43, we believe that propagation to subcortical arousal structures affects the cortex indirectly, rather than through direct cortical propagation. Consistent with this hypothesis, we found the hippocampus showed broad power increases at higher frequencies, whereas the cortex showed mainly lower frequency increases during seizures. We did not identify any specific frequency in the hippocampal power spectrum that was correlated with the observed alterations in behavioral responses.

A notable LFP finding in our model during the Ictal period is the early loss of 7–9 Hz theta frequency band power, with persistent absence of the hippocampal theta rhythm in the Postictal state, followed by rebound in the Recovery period. Hippocampal theta has been associated with locomotion speed in rodents44, and is believed to play a role in spatial learning/navigation. We found, however, depressed Ictal and Postictal theta regardless of behavioral impairment. With Recovery, the theta and low gamma frequencies exhibited higher than Baseline power elevations, and many of these frequency ranges including theta were significantly associated with correct responses. Improved power over these frequency ranges following the marked suppression in the Postictal period could be related to improved responses. Correlation of hits with power increases across distributed frequencies may be related to the importance of task-relevant spatial and non-spatial dimensions of memory retrieval and navigation45, 46. The observed hippocampal timecourse may be compared to the subcortically-driven ‘ignition’ sequence following emergence from anesthesia39.

Connecting behavior and electrophysiology

We utilized a relatively simple operant conditioned auditory response task to study ‘consciousness’ or ‘responsiveness.’ We found peri-ictal response impairment in hit rate but not in the response latency or the lick rate timecourse. This suggests that auditory perception or sound-response association is affected, but not an impairment in motor output. The marked hippocampal spectral differences in the Ictal and Postictal states compared to the Baseline and Recovery, and the cortical low-frequency oscillations seen in Ictal and Postictal states suggest that the impairment arises from a broad network mechanism. This would be consistent with the known electrophysiological timecourse of emergence from other states of altered responsiveness39, 47, and with spectral differences in the hippocampus and cortex specific to brain arousal state and behavior. The robust finding that cortical low-frequency oscillations were associated with misses during the Ictal and Postictal periods makes a direct link between peri-ictal behavioral impairment and remote cortical effects of limbic seizures, possibly mediated by changes in subcortical arousal state. A reward-driven task may impact the electrographic and behavioral output during seizures48; conversely, seizures impacting behavioral performance may be due to an interaction with subcortical reward and arousal circuitry (including the medial forebrain bundle) and could modulate reward circuits subserving the operant conditioned response. Full investigation of these circuits will require additional investigation in future studies.

Therapeutic utility of modeling peri-ictal behavioral impairment

Accurately modeling the behavioral outcomes in an acute focal limbic seizure model is clinically and scientifically significant. The circuit we hope to understand and to modulate includes deep nuclei, their white matter connections, and the cortex. Subcortical disruption may be important causally for the aberrant cortical oscillations we have associated with behavioral impairment4. Multiple pathologies and animal model studies have suggested the importance of the intralaminar thalamic nuclei16, 49, 50, therefore subcortical targeting of this circuit to improve behavior in a physiologically relevant way may have significant clinical implications26, 28, 29, 51 (see also https://braininitiative.nih.gov/funded-awards/thalamic-stimulation-prevent-impaired-consciousness-epilepsy). New therapeutic strategies to improve level of consciousness in epilepsy and traumatic brain injury have emerged52, 53. Accurate modeling of behavior will lay the foundation for testing strategies to limit seizure effects, understand propagation pathways, and prevent impairment of consciousness.

Key points:

We provide a novel animal model quantifying task-related impaired behavior and relation to neurophysiology during focal-onset limbic seizures.

Our data suggest that impaired behavioral responses during and after seizures are related low frequency cortical signals.

Such low frequency signals, based on previous work, may arise from depressed subcortical arousal.

Future therapies may be designed to improve peri-ictal consciousness with DBS or RNS to accessible network nodes such as intralaminar thalamus.

Acknowledgements

We thank Kate Christison-Lagay for helpful suggestions on design of the auditory stimulus. This work was supported by NIH/NINDS R01 NS066974 and NS096088 (HB), a Swebilius Foundation grant (AG, JG), by the Betsy and Jonathan Blattmachr family, and the Mark Loughridge and Michele Williams Foundation.

Footnotes

Ethical statement

We confirm that we have read the Journal’s position on issues involved in ethical publication and affirm that this report is consistent with those guidelines.

Disclosures

Authors AG, RM, DG, LAS, JX, BFG, CM, and HB have no conflicts of interest. JLG has served as a paid consultant for Medtronic.

References

- 1.Crick F, Koch C. A framework for consciousness Nat Neurosci. 2003. February;6:119–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Tononi G, Boly M, Massimini M, Koch C. Integrated information theory: from consciousness to its physical substrate Nat Rev Neurosci. 2016. July;17:450–461. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mashour GA, Roelfsema P, Changeux JP, Dehaene S. Conscious Processing and the Global Neuronal Workspace Hypothesis Neuron. 2020. March 4;105:776–798. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Blumenfeld H Impaired consciousness in epilepsy Lancet Neurol. 2012. September;11:814–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Blumenfeld H, Taylor J. Why do seizures cause loss of consciousness? Neuroscientist. 2003. October;9:301–310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Vickrey BG, Berg AT, Sperling MR, Shinnar S, Langfitt JT, Bazil CW, et al. Relationships between seizure severity and health-related quality of life in refractory localization-related epilepsy Epilepsia. 2000. June;41:760–764. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kwan P, Brodie MJ. Early identification of refractory epilepsy N Engl J Med. 2000. February 3;342:314–319. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gastaut H, Zifkin BG. The risk of automobile accidents with seizures occurring while driving: relation to seizure type Neurology. 1987. October;37:1613–1616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Williamson PD, French JA, Thadani VM, Kim JH, Novelly RA, Spencer SS, et al. Characteristics of medial temporal lobe epilepsy: II. Interictal and ictal scalp electroencephalography, neuropsychological testing, neuroimaging, surgical results, and pathology Ann Neurol. 1993. December;34:781–787. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Blumenfeld H, Rivera M, McNally KA, Davis K, Spencer DD, Spencer SS. Ictal neocortical slowing in temporal lobe epilepsy Neurology. 2004. September 28;63:1015–1021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Blumenfeld H, McNally KA, Vanderhill SD, Paige AL, Chung R, Davis K, et al. Positive and negative network correlations in temporal lobe epilepsy Cereb Cortex. 2004. August;14:892–902. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Norden AD, Blumenfeld H. The role of subcortical structures in human epilepsy Epilepsy Behav. 2002. June;3:219–231. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Englot DJ, Mishra AM, Mansuripur PK, Herman P, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H. Remote effects of focal hippocampal seizures on the rat neocortex J Neurosci. 2008. September 3;28:9066–9081. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Motelow JE, Li W, Zhan Q, Mishra AM, Sachdev RN, Liu G, et al. Decreased subcortical cholinergic arousal in focal seizures Neuron. 2015. February 4;85:561–572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Englot DJ, Modi B, Mishra AM, DeSalvo M, Hyder F, Blumenfeld H. Cortical deactivation induced by subcortical network dysfunction in limbic seizures J Neurosci. 2009. October 14;29:13006–13018. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Feng L, Motelow JE, Ma C, Biche W, McCafferty C, Smith N, et al. Seizures and Sleep in the Thalamus: Focal Limbic Seizures Show Divergent Activity Patterns in Different Thalamic Nuclei J Neurosci. 2017. November 22;37:11441–11454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhan Q, Buchanan GF, Motelow JE, Andrews J, Vitkovskiy P, Chen WC, et al. Impaired Serotonergic Brainstem Function during and after Seizures J Neurosci. 2016. March 2;36:2711–2722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Andrews JP, Yue Z, Ryu JH, Neske G, McCormick DA, Blumenfeld H. Mechanisms of decreased cholinergic arousal in focal seizures: In vivo whole-cell recordings from the pedunculopontine tegmental nucleus Exp Neurol. 2019. April;314:74–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Yue Z, Freedman IG, Vincent P, Andrews JP, Micek C, Aksen M, et al. Up and Down States of Cortical Neurons in Focal Limbic Seizures Cereb Cortex. 2019. November 30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sieu LA, Singla S, Chandrasekaran G, Sharaf A, Gummadavelli A, Martin R, et al. A novel mouse model of focal limbic seizures with impaired behavior and cortical slow waves AES Abstracts 2020. 2020;Abstract No. 462. Online at http://www.aesnet.org/.

- 21.Sieu L-A, Singla S, McCafferty C, Valcarce-Aspegren M, Niknahad A, Perrenoud Q, et al. Mouse model of electrically inducible focal seizures with impaired consciousness Soc Neurosci Abstract 2018, Abstract No 56102 Online at http://wwwsfnorg/Meetings/Past-and-Future-Annual-Meetings. 2018.

- 22.Sieu L-A, Singla S, Sharafeldin A, Chandrasekaran G, Valcarce-Aspegren M, Niknahad A, et al. A novel mouse model of focal limbic seizures that reproduces behavioral impairment associated with cortical slow wave activity bioRxiv. 2021:2021.2005.2005.442811. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Janszky J, Schulz R, Janszky I, Ebner A. Medial temporal lobe epilepsy: gender differences Journal of neurology, neurosurgery, and psychiatry. 2004. May;75:773–775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Mejias-Aponte CA, Jimenez-Rivera CA, Segarra AC. Sex differences in models of temporal lobe epilepsy: role of testosterone Brain Res. 2002. July 19;944:210–218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Englot DJ, Blumenfeld H. Consciousness and epilepsy: why are complex-partial seizures complex? Prog Brain Res. 2009;177:147–170. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gummadavelli A, Motelow JE, Smith N, Zhan Q, Schiff ND, Blumenfeld H. Thalamic stimulation to improve level of consciousness after seizures: evaluation of electrophysiology and behavior Epilepsia. 2015. January;56:114–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Paxinos G, Watson C. The rat brain in stereotaxic coordinates. 6th ed. Amsterdam; Boston;: Academic Press/Elsevier; 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Xu J, Galardi MM, Pok B, Patel KK, Zhao CW, Andrews JP, et al. Thalamic stimulation improves postictal cortical arousal and behavior J Neurosci. 2020. August 21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kundishora AJ, Gummadavelli A, Ma C, Liu M, McCafferty C, Schiff ND, et al. Restoring Conscious Arousal During Focal Limbic Seizures with Deep Brain Stimulation Cereb Cortex. 2017. March 1;27:1964–1975. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Fisher RS, Cross JH, French JA, Higurashi N, Hirsch E, Jansen FE, et al. Operational classification of seizure types by the International League Against Epilepsy: Position Paper of the ILAE Commission for Classification and Terminology Epilepsia. 2017. April;58:522–530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Cunningham C, Chen WC, Shorten A, McClurkin M, Choezom T, Schmidt CP, et al. Impaired consciousness in partial seizures is bimodally distributed Neurology. 2014. May 13;82:1736–1744. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Phelan KD, Shwe UT, Williams DK, Greenfield LJ, Zheng F. Pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in mice: A comparison of spectral analysis of electroencephalogram and behavioral grading using the Racine scale Epilepsy Res. 2015. November;117:90–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mohamed J, Scott BW, David O, McIntyre Burnham W. Development of propagated discharge and behavioral arrest in hippocampal and amygdala-kindled animals Epilepsy Res. 2018. December;148:78–89. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Post RM. Neurobiology of seizures and behavioral abnormalities Epilepsia. 2004;45 Suppl 2:5–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Muller CJ, Groticke I, Bankstahl M, Loscher W. Behavioral and cognitive alterations, spontaneous seizures, and neuropathology developing after a pilocarpine-induced status epilepticus in C57BL/6 mice Exp Neurol. 2009. September;219:284–297. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Brown EN, Lydic R, Schiff ND. General anesthesia, sleep, and coma N Engl J Med. 2010. December 30;363:2638–2650. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Siclari F, Baird B, Perogamvros L, Bernardi G, LaRocque JJ, Riedner B, et al. The neural correlates of dreaming Nat Neurosci. 2017. June;20:872–878. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pal D, Li D, Dean JG, Brito MA, Liu T, Fryzel AM, et al. Level of Consciousness Is Dissociable from Electroencephalographic Measures of Cortical Connectivity, Slow Oscillations, and Complexity J Neurosci. 2020. January 15;40:605–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Flores FJ, Hartnack KE, Fath AB, Kim SE, Wilson MA, Brown EN, et al. Thalamocortical synchronization during induction and emergence from propofol-induced unconsciousness Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017. August 8;114:E6660–E6668. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Squire LR, Ojemann JG, Miezin FM, Petersen SE, Videen TO, Raichle ME. Activation of the hippocampus in normal humans: a functional anatomical study of memory Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 1992. March 1;89:1837–1841. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Broadbent NJ, Squire LR, Clark RE. Spatial memory, recognition memory, and the hippocampus Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2004. October 5;101:14515–14520. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Chen G, King JA, Burgess N, O’Keefe J. How vision and movement combine in the hippocampal place code Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013. January 2;110:378–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Englot DJ, Yang L, Hamid H, Danielson N, Bai X, Marfeo A, et al. Impaired consciousness in temporal lobe seizures: role of cortical slow activity Brain. 2010. December;133:3764–3777. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Slawinska U, Kasicki S. The frequency of rat’s hippocampal theta rhythm is related to the speed of locomotion Brain Res. 1998. June 15;796:327–331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Aronov D, Nevers R, Tank DW. Mapping of a non-spatial dimension by the hippocampal-entorhinal circuit Nature. 2017. March 29;543:719–722. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Etter G, van der Veldt S, Manseau F, Zarrinkoub I, Trillaud-Doppia E, Williams S. Optogenetic gamma stimulation rescues memory impairments in an Alzheimer’s disease mouse model Nat Commun. 2019. November 22;10:5322. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Pais-Roldan P, Edlow BL, Jiang Y, Stelzer J, Zou M, Yu X. Multimodal assessment of recovery from coma in a rat model of diffuse brainstem tegmentum injury Neuroimage. 2019. April 1;189:615–630. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Taylor JA, Rodgers KM, Bercum FM, Booth CJ, Dudek FE, Barth DS. Voluntary Control of Epileptiform Spike-Wave Discharges in Awake Rats J Neurosci. 2017. June 14;37:5861–5869. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Giber K, Diana MA, Plattner V, Dugue GP, Bokor H, Rousseau CV, et al. A subcortical inhibitory signal for behavioral arrest in the thalamus Nat Neurosci. 2015. April;18:562–568. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Redinbaugh MJ, Phillips JM, Kambi NA, Mohanta S, Andryk S, Dooley GL, et al. Thalamus Modulates Consciousness via Layer-Specific Control of Cortex Neuron. 2020. April 8;106:66–75 e12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Schiff ND, Giacino JT, Kalmar K, Victor JD, Baker K, Gerber M, et al. Behavioural improvements with thalamic stimulation after severe traumatic brain injury Nature. 2007. August 2;448:600–603. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Gummadavelli A, Kundishora AJ, Willie JT, Andrews JP, Gerrard JL, Spencer DD, et al. Neurostimulation to improve level of consciousness in patients with epilepsy Neurosurg Focus. 2015. June;38:E10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kundu B, Brock AA, Englot DJ, Butson CR, Rolston JD. Deep brain stimulation for the treatment of disorders of consciousness and cognition in traumatic brain injury patients: a review Neurosurg Focus. 2018. August;45:E14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]