Abstract

Alzheimer’s disease (AD) is a neurodegenerative disorder, projected to be the second leading cause of mortality by 2040. AD is characterized by a progressive impairment of memory leading to dementia and loss of ability to carry out daily functions. In addition to the deficiency of acetylcholine release in synapse, there are other mechanisms explaining the etiology of the disease. The most disputing ones are associated with the accumulation of damaged proteins β-amyloid Aβ and hyperphosphorylated tau outside and inside neurons, respectively. Lysergic acid derivatives have been shown to possess promising anti-Alzheimer effect. Moreover, lysergic acid structure encompasses the general structural requirements for acetylcholinesterase inhibition. In this study, sixteen analogues, derived from lysergic acid structure, were synthesized. Heck and Mannich reactions were carried out to 4-bromo indole nucleus to generate potentially active analogues. Some of them were subsequently cyclized by nitromethane and zinc reduction procedures. Some of these compounds showed neuroprotective and anti-inflammatory effects stronger than the currently used anti-Alzheimer drug; donepezil. Some of the synthesized compounds showed a noticeable acetylcholinesterase inhibition. Twelve molecular targets attributed with AD etiology were tested versus the synthesized compounds by in silico modeling. Docking scores of modeling were plotted against in vitro activity of the compounds. The one afforded the strongest positive correlation was ULK-1 which has a significant role in autophagy.

Keywords: Alzheimer, Structural simplification, Lysergic acid, Neuroprotection

Graphical Abstract

Alzheimer’s (AD) is a neurodegenerative disease, considered to be the most prevalent form of dementia 1. It affects mostly elderly people, ages 65 years and over, in sporadic type of AD. The number of people expected to show AD manifestations is speculated to exceed 130 million by 2050. In 2015, the health care cost of AD was approximated to be $818 billion 2. Moreover, by 2040 neurodegenerative diseases are supposed to be the second leading cause of mortality 3. With the increase in life expectancy, the world is very prone to encounter a dementia epidemic in the near future 3. The most recognizable features of AD are accumulations of amyloid plaques consisting of β-amyloid (Aβ peptide) outside neurons and aggregates of neurofibrillary tangles resulting from hyper-phosphorylation of tau protein inside the neurons 1. Histological examination of autopsy brain specimens revealed that the amyloid plaques not only consisted of proteins, but also glial cells such as microglia 4.

The exact mechanism of AD is still ambiguous 3. Pathology of AD is attributed to mitochondrial damage, accumulation of Aβ, phosphorylated tau, synaptic dysfunction, hormonal imbalance and a cascade of inflammatory responses 2. Oxidative stress is also a possible etiological factor of AD 1. In 2000, it was noticed that people who consumed nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs for various inflammatory diseases had less incidence and prevalence of AD 5. Therefore, blocking inflammatory signaling was cited as a therapeutic strategy against AD 6,7. Microglia play an essential role in regulating the plasticity of the synapse, surveying the neurons from pathogen intrusions, cleaning the damaged cells by phagocytosis and facilitating remodeling of neuronal circuits. However, the excessive activity of microglia might idiosyncratically lead to neuronal loss due to aberrant induction of inflammation 4. Activated microglia release nitric oxide (NO), tumor necrosis factor-alpha (TNFα) and other pro-inflammatory cytokines causing a disruption of mitochondria and inducing apoptosis 8. Inflammation is a key factor for several CNS diseases such as stroke, multiple sclerosis, Parkinson and AD 8.

One of the newly introduced mechanism of neuroinflammation is endoplasmic reticulum (ER) stress, which might prove to be a potential target in treating neurodegenerative diseases 9,10. ER is responsible for secretory and membrane protein modifications including folding and post-translational alterations 11,12. A change in the lumen of ER including the level of calcium and folding capacity of chaperone proteins may trigger protein misfolding, which could be solved by unfolding protein response (UPR) 13,14. If UPR does not work properly then apoptosis commence through a cascade of inflammatory responses attributed to ER stress 15. Chemicals that induce ER stress include; tunicamycin which interferes with protein glycation during the post-translational modification and thapsigargin which disrupts ER calcium levels 16,17. Lipopolysaccharide (LPS) as a flammogen triggers ER stress and also induces cellular pro-inflammatory cascade after binding to a membrane receptor called TLR4 18.

One of the promising lead compounds in the treatment of AD is lysergic acid. It is an ergot alkaloid extracted from rye fungus Claviceps purpurea 19. Ergot alkaloids are used in improving mental recognition and other symptoms related to AD 20. For example, the FDA-approved ergot derived drug, ergoloid mesylates (Hydergine®), bestows small measurable improvements in the treatment of AD 21,22. Nicergoline (Sermion®) is another ergoline alkaloid that is currently used for senile dementia 23. Ergot alkaloids are assumed to enhance the blood flow to the brain and modulate the neurotransmitter function 23. However, there is still a lack of effective AD medications and therefore, developing more efficacious and safe candidates is crucial 24,25.

Several analogues of lysergic acid were synthesized by adopting a structural simplification strategy. Their neuroprotection and anti-inflammatory properties as well as their potential in inhibiting acetylcholinesterase were evaluated. Moreover, the neuroprotective efficacy of the compounds was assessed in silico against known molecular targets involved in AD and then compared using in vitro assays.

Since lysergic acid derivatives are well known as anti-AD agents (e.g. FDA approved drug Hydergin®), they were adopted here as lead compounds for designing new potential anti-AD agents. Structural simplification as a drug design approach was used to rationalize the synthetic targets. Structural simplification is generally used to reduce the molecular complexity of natural products. Additionally, simplifying chemical structure may enhance both efficacy and pharmacokinetic properties of compounds, and may lead to analogues with reduced undesirable side effects as exemplified by morphine analogues methadone and pethidine that are derived by the simplification of morphine structure. The proposed analogues were designed by the simplification of lysergic acid skeleton while preserving some components of acetylcholine esterase inhibitor pharmacophore (Figure 1). The synthetic intermediates as well as synthesis byproducts were also subjected to biological testing to expand the structure-activity relationship profile.

Figure 1.

Structural simplification of lysergic acid to guide the synthesis of simpler anti-Alzheimer agents.

SAR of acetylcholine esterase inhibitors revealed a hydrogen bond acceptor such as carbonyl group and an ammonium head for steering the compound towards its receptor, connected by a spacer such as a benzoid nucleus. Using lysergic acid as a model of ergot-derived compounds, carbonyl group containing moieties such as ester were incorporated into some analogues and an amide group was introduced in others to improve the drugability of the compounds. Analogues lacking ammonium head were also tested to obtain a better insight of the role of basic nitrogen on activity as the loss of ionization may enhance some kinetic properties such as penetration of blood-brain barrier (BBB). Moreover, compounds without basic functionality may lead to activity against targets other than acetylcholinesterase. While some of the analogues preserved the ergoline ring system, structure simplification also involved trimming down the fused tetracyclic ring of ergoline to simpler bicyclic indole system in some of the synthesized analogues. Additionally, shortening the distance between the basic nitrogen and the indole ring may affect activity; Castle and Whittle found that increasing the distance between the basic nitrogen and the indole ring failed to produce biologically active compounds in derivatives of lysergic acid 26,27, whereas reducing this distance to one carbon length depicted strong biological activity and toxicity 28. Another example is gramine, which has one carbon atom distance between its basic nitrogen and indole ring and possesses activity against AD 29. It is conceivable that activity of gramine derivatives may be due to generation of a reactive electrophilic species upon loss of amine function.

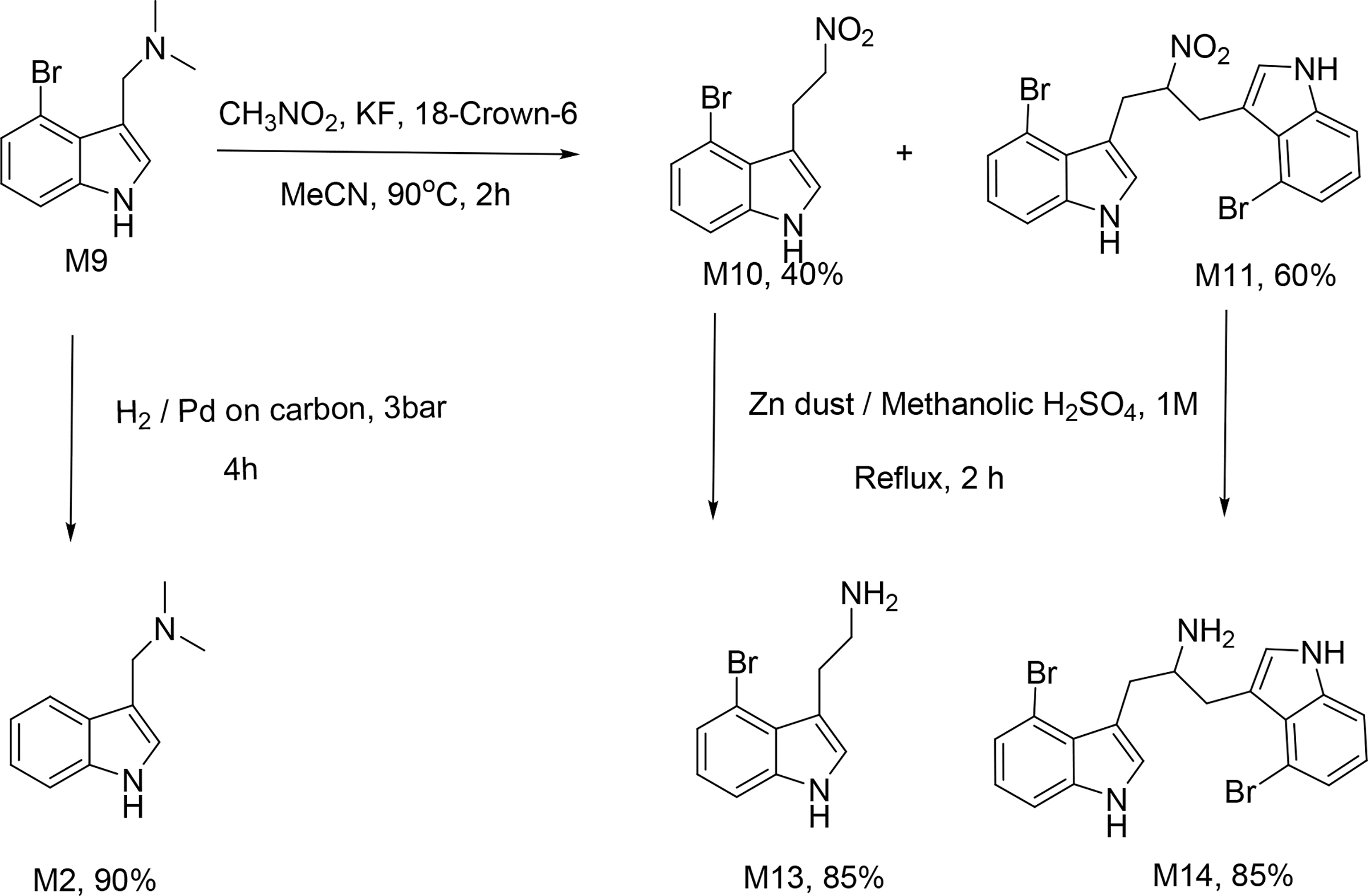

Altogether, sixteen analogues were synthesized of which six; namely M5, M8, M11, M12, M14 and M16 (Figure 2) are novel compounds and a few; M2, M9 and M13 are commercially available. The analogues M3 and M5 were designed by dissecting the alicyclic rings of lysergic acid and reducing the distance between the basic amine and indole by one carbon atom. It has been reported that amide and ester modification of carboxylic acid in other lysergic acid analogues affords CNS activity 30,31. Therefore, carboxylic acid conversion to simple ester or amide led to M1, M3, M4, M5, M6, M7, M8 and M15. The analogues without a basic functional group were designed to prepare a diverse set of compounds for a comprehensive understanding of SAR. The synthesis involved as key reactions Heck coupling used to introduce the hydrogen bond acceptor such as ester or amide group and Mannich reaction to introduce the basic amine fragment (Scheme 1). Michael addition of nitromethane-derived carbanion was employed to build the precursor for cyclisation. Potentially toxic nitro was reduced to amine using zinc dust in acidic medium.

Figure 2.

The synthesized compounds.

Scheme 1.

Synthesis of compounds using methyl acrylate in Heck coupling.

Heck reaction was carried out by heating the reaction mixture in a microwave synthesizer and gave 85% yield when methyl acrylate was used as olefin coupling partner (Scheme 1). Heck reaction with acrylamide gave low yields (<30%, Scheme 2) when several Pd(II) and Pd(0) catalysts were used individually. Interestingly, the yields increased enormously (>90%) when a mixture of Pd(II) and Pd(0) catalysts was used. (Figure 3). This remarkable reactivity when a combination of Pd(0) and Pd(II) catalysts was used maybe explained as due to rate enhancement through the generation of an anionic Pd(0) intermediate (Figure 3). The anionic Pd(0) complex formed is more nucleophilic and drastically enhances the rate of the oxidative addition step in the catalytic cycle. Moreover, the generated ionic Pd(0) complex increases the stability of the catalytically active Pd(0) state. Eventually, the introduction of nitromethane anion, followed by reduction of the nitro group with zinc dust and acid were carried out (Scheme 3).

Scheme 2.

Synthesis of compounds using acrylamide in Heck.

Figure 3.

Proposed catalytic cycle mediated by an anionic Pd(0) complex formed from palladium (0) and palladium (II). The anionic form of the complex may enhance the stability and the nucleophilicity of the catalyst towards the aryl halide reactant in the oxidative addition step. The rest of the cycle includes other elements of catalytic cycle; migratory insertion and reductive elimination.

Scheme 3.

Synthesis of non-carbonyl containing compounds.

The neuroprotective properties of synthesized compounds were assessed using cellular assays and anti-AD drug donepezil (DPZ) was used as the positive control. In an initial screening to determine a suitable concentration for testing, the lowest concentration at which DPZ exhibited significant neuroprotection in neuronal cell line under oxygen and glucose-deprived conditions (OGD) was 0.1 μM (Figure 4). Therefore, the compounds were initially screened for neuroprotective activity at a 10-fold higher concentration of 1 μM with DPZ as the positive control (Figure 5). All compounds were screened in each assay, but only the most active ones were included in the plots for clarity. Six analogues; M3, M5, M6, M8, M9 and M11showed neuroprotective activity comparable with that of DPZ. The analogues M3, M5, M9 have basic amine group, while the analogues M3, M5, M6 and M8 are structurally similar. Interestingly, the analogues M3, M5 and M8 share common structural features with lysergic acid. Some of nitro/bromine containing compounds, M6, M9 and M11 show neuroprotective effects as well. To further evaluate their biological activity, the compounds were tested for anti-inflammatory properties.

Figure 4.

Percentage viability of PC12 cells under oxygen and glucose deprived (OGD) conditions and treated with varying concentrations of donepezil. Concentrations which caused significant differences at a p-value≤0.05 compared with the reference (OGD/R) are marked with (*).

Figure 5.

Percentage viability of PC12 cells grown in oxygen and glucose (OGD) deprived conditions and treated with 1μM of test compounds. Compounds that showed significant differences compared to donepezil (DPZ) at a p-value≤0.05 are asterisked.

Interestingly, the cell line, which was first challenged with LPS, significantly recovered after treatment with compounds M3, M5 and M8, which have close structural resemblance to lysergic acid (Figure 6). As seen in the Figure 6, all of the tested compounds were effective except the nitro containing compound M11. Interestingly, it has been reported that some nitro compounds acted as neuroprotective agents in ischæmic animal models due to the lowering of NO levels 32,33. On the other hand, the nitro group has an intrinsic inflammatory effect through the generation of reactive oxygen species 34. The neuroprotective activity and the lack of anti-inflammatory effect of M11 are consistent with these findings.

Figure 6.

Percentage of cell viability after inducing inflammation in SIM-A9 cell line with lipopolysaccharides (LPS) and treating with 1μM concentration of each compound. (#) denotes significant difference between each group and LPS group, and (*) refers to a significant difference in comparison with donepezil (DPZ). P-Value≤0.05.

Interestingly, M5 and M8 are significantly potent than DPZ. In order to gain a deeper insight into the anti-inflammatory mechanisms, the compounds were further tested in two other assays, one using the neuronal cell line (PC12), and the other using the microglial cell line (SIM-A9). ER stress was used to determine the anti-inflammation effects of the compounds (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Percentage of cell viability after exposing PC12 cells to tunicamycin (TCN) and treating cells with 1μM of tested compounds. (#) denotes significant difference between each group and TCN group, whereas (*) refers to a significant difference of each group in comparison with Donepezil (DPZ). P-Value≤0.05.

The neuronal PC12 cell line was challenged with tunicamycin (TCN) to induce ER stress and treated with 1μM of each compound. A remarkable activity in increasing cell viability was observed. More interestingly, the analogues M3, M5, M6, M8, M9 and M11 were more potent than DPZ. Microglia have a significant role in the induction of neuroinflammation with a mechanism related to increasing oxidative stress. Microglial cells first challenged with LPS, release NO, which leads to inflammation. As shown in Figure 8, the tested compounds showed significant differences in the ability to reduce NO release from the cells, compared to the untreated group. Once more, the analogues structurally related to lysergic acid, namely M3, M5, M8 and M9, were more potent than DPZ in reducing NO release from microglia.

Figure 8.

Nitric oxide (NO) release from microglial SIM-A9 cell line after treatment with LPS and 1μM from each compound. (#) denotes significant difference between each group and LPS whereas asterisked groups are significantly different than Donepezil (DPZ).

Most of the analogues possessed structural components required for acetylcholine esterase (AChE) enzyme inhibition; such as the existence of a positive ammonium head to interact with the acidic glutamate (GLU-327) and a hydrogen bond acceptor that interacts with SER-200 in the binding pocket. Thus, the synthesized analogues were tested for AChE inhibitory activity. As shown in Figure 9, the analogues M3, M5 and M15 demonstrated activity not significantly different from that of the well-known potent AChE inhibitor DPZ. Computing the spatial distance between the basic nitrogen and the oxygen of the carbonyl group in energetically minimized 3D structures of M3 and M5 yielded a value of 5.7 Å. This value lies between the corresponding distances in DPZ (6.4 Å) and nicergoline (5.4 Å). The distance in M3 and M5 is very close to that of nicergoline, which is a lysergic derivative with AChE inhibitory activity 35.

Figure 9.

Acetylcholinesterase inhibition activity compared to Donepezil (DPZ). M3, M5 and M15 are not significantly different than donepezil (DPZ) at p-value≤0.05 at a concentration of 1μM for each.

Although M15 lacks any basic groups in its structure, and consequently, cannot bind strongly to the anionic site of the enzyme, it still has potent activity against the enzyme. This could be due to its high lipophilicity and structural rigidity compared to the other compounds. The rigidity reduces the entropy penalty spent by the system during the binding of the ligand to the enzyme.

However, the level of activity of the compounds against AChE, compared to the high potency of DPZ does not necessarily reflect the promising activity of the compounds at the cellular level. This necessitates screening for other enzyme targets. A group of enzymes that is reported to be directly related to neuroinflammatory mechanisms are BACE1, β-secretase, CDK5, γ-secretase, GSK3B, HSP70ase, JNK, MAPK, PKC, TBK1 and ULK1. Therefore, an in-silico approach was adopted to study the possibility of any of them being potential targets of these compounds. After carrying out docking studies with all of the synthesized compounds (M1-M16) against these enzymes, docking scores obtained were correlated with the observed activity of the compounds as anti-inflammatory agents. The enzymes that showed a positive correlation with the tested compounds were BACE1, CDK5, γ-secretase, HSP70ase, and ULK1 (Figure 10). Of these, only ULK1 had a valid positive correlation with 95% confidence interval not crossing zero, i. e. not crossing the x-axis. The enzymes that have positive correlations are considered as candidates for future testing with the synthesized compounds to gain a better insight of their molecular mechanism of action.

Figure 10.

Coefficients of correlations between docking score of in silico enzymatic inhibition by the synthesized compounds (M1-M16) and the compounds’ anti-inflammatory activity. Bars represent 95% confidence intervals. β-sec denotes β-secretase while γ-sec refers to γ-secretase.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This study was supported by NIH grants R15CA213185 to L.M.V.T and R01NS112642 to ZAS, and the American Heart Association grant 17AIREA33700076/ZAS/2017 to ZAS. The authors thank the Fulbright Program for a Visiting Scholar Award to MHA.

Footnotes

Supplementary Material

The Supporting Information is available free of charge online. Materials and methods along with the details of assays, synthesis and compound characterization, and 1H and 13C NMR spectra are provided as supporting information (PDF).

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References and notes

- (1).Boccardi V; Murasecco I; Mecocci P Diabetes Drugs in The Fight Against Alzheimer’s Disease. Ageing Res. Rev. 2019, 100936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (2).Kuruva CS; Reddy PH Amyloid Beta Modulators and Neuroprotection in Alzheimer’s Disease: A Critical Appraisal. Drug Discov. Today 2017, 22 (2), 223–233. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (3).Giaume C; Sáez JC; Song W; Leybaert L; Naus CC Connexins and Pannexins in Alzheimer’s Disease. Neurosci. Lett. 2017, 16 (pand695), 100–105. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (4).Van Eldik LJ; Carrillo MC; Cole PE; Feuerbach D; Greenberg BD; Hendrix JA; Kennedy M; Kozauer N; Margolin RA; Molinuevo JL The Roles of Inflammation and Immune Mechanisms in Alzheimer’s Disease. Alzheimer’s Dement. Transl. Res. Clin. Interv. 2016, 2 (2), 99–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (5).Szekely CA; Thorne JE; Zandi PP; Ek M; Messias E; Breitner JCS; Goodman SN Nonsteroidal Anti-Inflammatory Drugs for the Prevention of Alzheimer’s Disease: A Systematic Review. Neuroepidemiology 2004, 23 (4), 159–169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (6).Town T; Laouar Y; Pittenger C; Mori T; Szekely CA; Tan J; Duman RS; Flavell RA Blocking TGF-β–Smad2/3 Innate Immune Signaling Mitigates Alzheimer-like Pathology. Nat. Med. 2008, 14 (6), 681–687. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (7).Guillot-Sestier M-V; Doty KR; Gate D; Rodriguez J Jr; Leung BP; Rezai-Zadeh K; Town T Il10 Deficiency Rebalances Innate Immunity to Mitigate Alzheimer-like Pathology. Neuron 2015, 85 (3), 534–548. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (8).Tsou Y-C; Wang H-H; Hsieh C-C; Sun K-H; Sun G-H; Jhou R-S; Lin T-I; Lu S-Y; Liu H-Y; Tang S-J Down-Regulation of BNIP3 by Olomoucine, a CDK Inhibitor, Reduces LPS-and NO-Induced Cell Death in BV2 Microglial Cells. Neurosci. Lett. 2016, 628, 186–193. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (9).de la Monte SM Triangulated Mal-Signaling in Alzheimer’s Disease: Roles of Neurotoxic Ceramides, ER Stress, and Insulin Resistance Reviewed. J. Alzheimer’s Dis. 2012, 30 (s2), S231–S249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (10).Bharathi MD; Justin-Thenmozhi A; Manivasagam T; Rather MA; Babu CS; Essa MM; Guillemin GJ Amelioration of Aluminum Maltolate-Induced Inflammation and Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress-Mediated Apoptosis by Tannoid Principles of Emblica Officinalis in Neuronal Cellular Model. Neurotox. Res. 2019, 35 (2), 318–330. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (11).Stevens FJ; Argon Y Protein Folding in the ER. In Seminars in cell & developmental biology; Elsevier, 1999; Vol. 10, pp 443–454. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (12).Matsuo Y; Nishinaka Y; Suzuki S; Kojima M; Kizaka-Kondoh S; Kondo N; Son A; Sakakura-Nishiyama J; Yamaguchi Y; Masutani H TMX, a Human Transmembrane Oxidoreductase of the Thioredoxin Family: The Possible Role in Disulfide-Linked Protein Folding in the Endoplasmic Reticulum. Arch. Biochem. Biophys. 2004, 423 (1), 81–87. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (13).Rao RV; Ellerby HM; Bredesen DE Coupling Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress to the Cell Death Program. Cell Death Differ. 2004, 11 (4), 372–380. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (14).Hoozemans JJM; Scheper W Endoplasmic Reticulum: The Unfolded Protein Response Is Tangled in Neurodegeneration. Int. J. Biochem. Cell Biol. 2012, 44 (8), 1295–1298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (15).Turner BJ; Atkin JD ER Stress and UPR in Familial Amyotrophic Lateral Sclerosis. Curr. Mol. Med. 2006, 6 (1), 79–86. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (16).Bull VH; Thiede B Proteome Analysis of Tunicamycin-induced ER Stress. Electrophoresis 2012, 33 (12), 1814–1823. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (17).Zhang X; Yuan Y; Jiang L; Zhang J; Gao J; Shen Z; Zheng Y; Deng T; Yan H; Li W Endoplasmic Reticulum Stress Induced by Tunicamycin and Thapsigargin Protects against Transient Ischemic Brain Injury: Involvement of PARK2-Dependent Mitophagy. Autophagy 2014, 10 (10), 1801–1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (18).Lu Y-C; Yeh W-C; Ohashi PS LPS/TLR4 Signal Transduction Pathway. Cytokine 2008, 42 (2), 145–151. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (19).Oellig C Lysergic Acid Amide as Chemical Marker for the Total Ergot Alkaloids in Rye Flour–Determination by High-Performance Thin-Layer Chromatography–Fluorescence Detection. J. Chromatogr. A 2017, 1507, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (20).Jadhav SU; Ghatage TS; Thanekar AM A Brief Review of Chemistry and Pharmacology of Lysergic Acid Diethylamide. Res. J. Pharm. Technol. 2017, 10 (12), 4415–4422. [Google Scholar]

- (21).Wallach J; Colestock T; Adejare A Receptor Targets in Alzheimer’s Disease Drug Discovery. In Drug Discovery Approaches for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Disorders; Elsevier, 2017; pp 83–107. [Google Scholar]

- (22).Hesselink JMK Idalopirdine (LY483518, SGS518, Lu AE 58054) in Alzheimer Disease: Never Change a Winning Team and Do Not Build Exclusively on Surrogates. Lessons Learned from Drug Development Trials. J Pharmacol Clin Res 2016, 2. [Google Scholar]

- (23).Zang G; Fang L; Chen L; Wang C Ameliorative Effect of Nicergoline on Cognitive Function through the PI3K/AKT Signaling Pathway in Mouse Models of Alzheimer’s Disease. Mol. Med. Rep. 2018, 17 (5), 7293–7300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (24).Panda SS; Jhanji N Natural Products as Potential Anti-Alzheimer Agents. Curr. Med. Chem. 2019, 27 (35), 5887–5917. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (25).Tehrani MB; Rezaei Z; Asadi M; Behnammanesh H; Nadri H; Afsharirad F; Moradi A; Larijani B; Mohammadi-Khanaposhtani M; Mahdavi M Design, Synthesis, and Cholinesterase Inhibition Assay of Coumarin-3-carboxamide-N-morpholine Hybrids as New Anti-Alzheimer Agents. Chem. Biodivers. 2019, 16 (7), e1900144. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (26).CASTLE RN; WHITTLE CW Synthesis of Some 2-(3-Indolylethenyl)-and 2-(2-Pyrrylethenyl)-Pyridines and Hydrogenated Analogs. J. Org. Chem. 1959, 24 (9), 1189–1192. [Google Scholar]

- (27).Whittle CW; Castle RN Open-chain Analogs of LSD II. Synthesis of Some 2-(3-indolylethyl)-and 2-(3-methyl-2-indolylethyl) Piperidines. J. Pharm. Sci. 1963, 52 (7), 645–648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (28).Campaigne E; Knapp DR Structural Analogs of Lysergic Acid. J. Pharm. Sci. 1971, 60 (6), 809–814. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (29).Lajarín-Cuesta R; Nanclares C; Arranz-Tagarro J-A; Gonzalez-Lafuente L; Arribas RL; Araujo de Brito M; Gandía L; de Los Ríos C Gramine Derivatives Targeting Ca2+ Channels and Ser/Thr Phosphatases: A New Dual Strategy for the Treatment of Neurodegenerative Diseases. J. Med. Chem. 2016, 59 (13), 6265–6280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (30).Family N; Maillet EL; Williams LTJ; Krediet E; Carhart-Harris RL; Williams TM; Nichols CD; Goble DJ; Raz S Safety, Tolerability, Pharmacokinetics, and Pharmacodynamics of Low Dose Lysergic Acid Diethylamide (LSD) in Healthy Older Volunteers. Psychopharmacology (Berl). 2020, 237 (3), 841–853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (31).Lasslo A; Waller PD Derivatives of N-Methylpiperidine. J. Med. Chem. 1959, 2 (1), 107–110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (32).Carreau A; Duval D; Poignet H; Scatton B; Vigé X; Nowicki J-P Neuroprotective Efficacy of Nω-Nitro-L-Arginine after Focal Cerebral Ischemia in the Mouse and Inhibition of Cortical Nitric Oxide Synthase. Eur. J. Pharmacol. 1994, 256 (3), 241–249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (33).Gill R; Nordholm L; Lodge D The Neuroprotective Actions of 2, 3-Dihydroxy-6-Nitro-7-Sulfamoyl-Benzo (F) Quinoxaline (NBQX) in a Rat Focal Ischaemia Model. Brain Res. 1992, 580 (1–2), 35–43. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (34).Cӑtoi AF; Pârvu AE; Andreicuț AD; Mironiuc A; Crӑciun A; Cӑtoi C; Pop ID Metabolically Healthy versus Unhealthy Morbidly Obese: Chronic Inflammation, Nitro-Oxidative Stress, and Insulin Resistance. Nutrients 2018, 10 (9), 1199. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- (35).Matsuoka Y Inhibitory Action of Nicergoline and Its Major Metabolites on Acetylcholinesterase Activity in Rat and Mouse Brain. Basic, Clin. Ther. Asp. Alzheimer’s Park. Dis. 1990, 2, 415–419. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.