SUMMARY

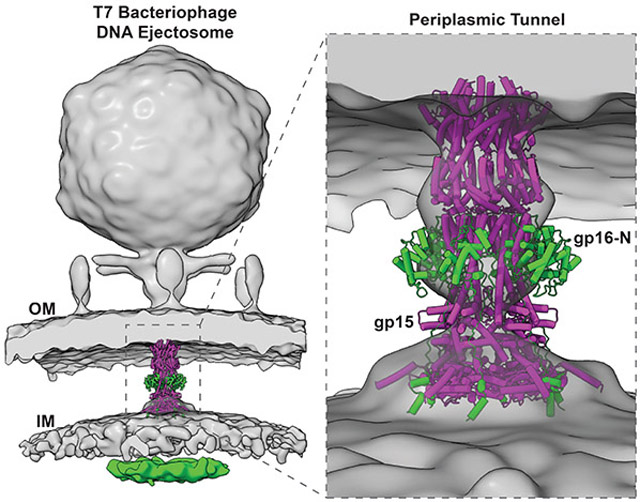

Hershey and Chase used bacteriophage T2 genome delivery inside Escherichia coli to demonstrate that DNA, and not protein, is the genetic material. 70 years later, our understanding of viral genome-delivery in prokaryotes remains limited, especially for short-tailed phages of the Podoviridae family. These viruses expel mysterious ejection proteins found inside the capsid to form a DNA ejectosome for genome delivery into bacteria. Here, we reconstitute the phage T7 DNA ejectosome components gp14, gp15, and gp16 and solve the periplasmic tunnel structure at 2.7 Å resolution. We find gp14 forms an outer membrane pore, gp15 assembles into a 210 Å hexameric DNA tube spanning the host periplasm, and gp16 extends into the host cytoplasm forming a ~4,200 residue hub. Gp16 promotes gp15 oligomerization, coordinating peptidoglycanhydrolysis, DNA-binding, and lipid-insertion. The reconstituted gp15:gp16 complex lacks channel-forming activity, suggesting the pore for DNA passage forms only transiently during genome-ejection.

Graphical Abstract

eTOC

Bacterial viruses are the most abundant form of life on earth, yet little is known about how they deliver DNA into bacteria. Here, Swanson et al. deciphered the first, complete architecture of the bacteriophage T7 DNA-ejectosome. This molecular machine is expelled into the bacterium cell envelope to mediate DNA delivery.

INTRODUCTION

T7 internal core proteins gp14, gp15, and gp16 are essential for phage morphogenesis and infection (Molineux, 2001; Molineux and Panja, 2013). They account for ~1.5 MDa of mass inside the mature T7 virion (Guo et al., 2013) and, upon infection, are expelled through the ~30 Å wide portal channel (Cuervo et al., 2019; Leptihn et al., 2016). Phage T7 ejection proteins exist in two structurally-distinct states: a pre-ejection conformation, coaxially arranged onto the dodecameric portal protein to form a 'core stack' (Agirrezabala et al., 2005; Cerritelli et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2013), and a post-ejection conformation, assembled as a transenvelope channel in the bacterial periplasm ('DNA-ejectosome') (Hu et al., 2013; Serwer et al., 2008). The tomographic reconstruction of T7 infecting E.coli minicells also revealed a toroid density projecting inside the host cytoplasm (Hu et al., 2013), whose molecular identity is unknown. The T7 ejectosome assembles after a virion encounters a host cell (Gonzalez-Garcia et al., 2015) that triggers gp14, gp15, and gp16 ejection into the host periplasm (Jin et al., 2015; Lupo et al., 2016). Tomographic studies revealed that, in addition to phage T7, the Salmonella phages P22 (Wang et al., 2019) and Epsilon 15 (Chang et al., 2010b) eject a channel into the host cell envelope upon infection. Similarly, previous tomographic studies on the bacteriophage P-SSP7 infecting Prochlorococcus suggested the disappearance of the inner core proteins after host attachment (Liu et al., 2010), although a transenvelope channel was not directly observed in this work. A more recent study (Murata et al., 2017) revealed that P-SSP7 phages vertically-oriented onto the host surface have a density beyond the tail tip, possibly consistent with a tube for DNA ejection, supporting observation made for the cyanophage Syn5 (Dai et al., 2013). A low-resolution cryo-EM reconstruction of the bacteriophage P22 lacking the tail needle gp26 (McNulty et al., 2018) revealed a tube-like protein density extending from the center of the tail assembly, which was interpreted as one of the P22 ejection proteins, possibly gp16 or gp20 (McNulty et al., 2018). The idea that the ejection proteins form a tube was also supported by a low-resolution negative stain reconstruction of the phage Sf6 gp12 (a homolog of P22 gp20), which in vitro forms a hollow, possibly decameric tube large enough to accommodate hydrated DNA (Zhao et al., 2016). Despite growing evidence, especially from cryo-ET (Chang et al., 2010b; Dai et al., 2013; Hu et al., 2013; Liu et al., 2010; Murata et al., 2017; Wang et al., 2019) that the ejection proteins form an extensible tail into the host cell envelope, the biology of ejection proteins, their assembly, and the composition of the DNA-ejectosome are speculative. Furthermore, no atomic structure of an ejection protein has yet been determined, limiting the power of tertiary structure prediction and domain analysis for these proteins, which remain mostly unannotated in the sequenced genomes of hundreds of bacteriophages.

The mechanisms by which ejection proteins mediate genome-ejection in Podoviridae are poorly understood (Molineux and Panja, 2013) and may differ significantly in different phages. For instance, bacteriophage P22 causes drastic changes in the bacterial membrane permeability for K+ during infection, whereby K+ release correlates with DNA delivery into target cells - an ejection protein mediated event (Bohm et al., 2018; Leavitt et al., 2013). In contrast, phage T7 infection does not cause cytoplasmic K+ to leak from cells (Kuhn and Kellenberger, 1985; Molineux and Panja, 2013), likely due to differences in genome ejection machinery. Fractionation studies of bacterial cells infected by T7 revealed that the smallest ejection protein gp14 forms a channel across the outer membrane (OM), while gp15 and gp16 possibly span the host periplasm and cytoplasmic membrane (Chang et al., 2010a; Hu et al., 2013; Kemp et al., 2005). These two proteins were hypothesized to ratchet phage DNA inside the host using the proton motive force as an energy source (Kemp et al., 2004). Gp15 and gp16 are involved in the ejection of the first ~850 bp of the 40 kb T7 genome, which proceeds at a constant rate and with a temperature-dependence like an enzymatic reaction. The initial ejection of the T7 genome mediated by gp15:gp16 exposes three promoters to the bacterial RNA polymerase, which pulls the rest of the phage DNA inside the host (Garcia and Molineux, 1995, 1996; Struthers-Schlinke et al., 2000). Overall, both the initial transcription-independent ejection of the first ~1 kb of the T7 genome and the RNA-polymerase-dependent pulling of the remaining phage DNA are enzymatic events, inconsistent with a model where the energy stored in the pressurized DNA provides the driving force for genome-ejection (Molineux and Panja, 2013).

Here, we used cryo-electron microscopy (cryo-EM) and hybrid structural methods to determine the structure of the periplasmic tunnel (PT) of the T7 DNA-ejectosome and decipher the activities of T7 ejection proteins. This work led us to derive the complete model of a prototypical DNA-ejectosome.

RESULTS

Bioinformatic analysis of ejection proteins in Podoviridae

Ejection proteins are conserved in the genomes of Podoviridae phages that infect gram-negative bacteria, including Enterobacteriaceae, mycobacteria, and cyanobacteria, but are not found in podophages such as phi29-like phages that infect Gram-positive bacteria, possibly due to the different cell envelope composition. Ejection proteins have low sequence homology to other phage and bacterial proteins and remain largely unannotated in the sequenced genomes of many phages. Using phage T7 ejection proteins as a reference, we selected nine common Podoviridae that infect Escherichia coli, Salmonella, Pseudomonas, Shigella, and Prochlorococcus and identified the genes encoding gp14, gp15, and gp16 homologous proteins (Data S1). This analysis revealed the genes encoding ejection proteins are clustered in a small operon, where the gene encoding the gp14-like factor is adjacent to gp15, followed by a larger ORF encoding gp16. Gp14 is the most conserved of the three ejection proteins, both in sequence and size, with an average sequence identity and similarity of 24/37% in the ten phages analyzed in this study (Data S2). All gp14-like factors contain a set of 4 or 5 predicted transmembrane helices, except P-SSP7 gp14, which is predicted to have only 2 TMHs (see also Figure S1C). In contrast, gp15 and gp16 vary significantly in amino acid sequence, size, and composition (Data S2) (Hardies et al., 2016) with an average sequence similarity under 34%. An N-terminal peptidoglycan hydrolase domain present in T7 gp16 is not conserved in P22 or Sf6, where this ejection protein is significantly smaller (e.g., 1318 vs 609 and 665, respectively, Data S1). Likewise, T7 gp16 contains putative transmembrane helices at the C-terminus (Lupo et al., 2016; Molineux, 2001) that we also identified in all gp16-like factors in Data S1.

Biochemical reconstitution of phage T7 ejection proteins

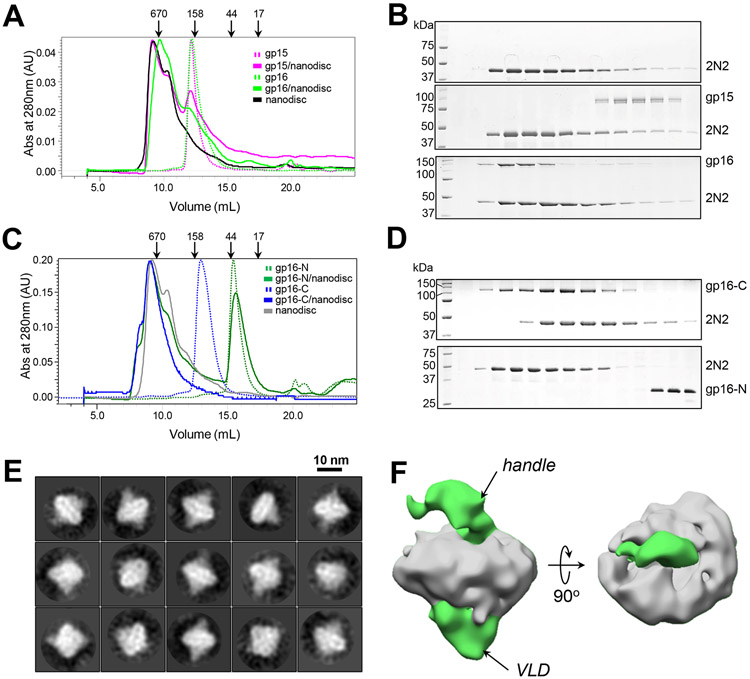

We individually purified gp14, gp15, and gp16 from E. coli using overexpression vectors and studied their domain architecture and binding interactions in solution. Gp14 (196 residues) (Figure 1A) is the first ejection protein to emerge from the virion during infection (Chang et al., 2010a). We found that gp14 is completely water-insoluble, but after detergent solubilization (Figure S1A), the protein forms a discrete oligomeric species (Figure S1B), possibly representative of the pore that inserts in the host OM during infection (Chang et al., 2010a). MemBrain (Yin et al., 2018) predicts five transmembrane α-helixes in gp14 (Figure S1C). This topology appears to be conserved in gp14-homologous proteins identified in other Podovoridae (Data S1). Gp15 (747-residue protein) (Figure 1A) is mainly monomeric in solution (Figure S1D) and highly enriched in α-helices, as determined by circular dichroism (CD) (Figure S1E). It denatures with an apparent melting temperature (appTm) of 48°C, indicative of a folded polypeptide chain. Gp16, the largest of the three ejection proteins (1,318 residues) (Figure 1A), is also the most complex. It contains a peptidoglycan hydrolytic domain in the first ~155 residues (Moak and Molineux, 2004), followed by ~1,150 residues of unknown structure. Recombinant gp16 is monomeric in solution (Figure S2A) and water-soluble despite harboring putative transmembrane helices (Lupo et al., 2016; Molineux, 2001). Using limited proteolysis (Figure S2C), we identified two domains: gp16-N, spanning the N-terminal 228 residues, and gp16-C that includes the remaining ~1,100 amino acids, which chymotrypsin further digests to a ~70 kDa fragment. The individual recombinant gp16-N and gp16-C proteins were soluble and monomeric (Figure S2D). They displayed helical signal at 222 nm, denaturing with appTms of ~46°C and 44°C, respectively (Figure S2E). Using a gel-shift assay on a native polyacrylamide gel, we found gp16-N associated with gp15 (Figure S3A), and, together, the two proteins formed a screw-shaped complex visible by negative stain EM (Data S3A). This complex was efficiently formed from dilute ejection proteins using sub-stoichiometric quantities of gp16-N. We vitrified the gp15:gp16-N complex (Data S3B) and collected ~8,000 movies in super-resolution mode that yielded 4.7 million particles.

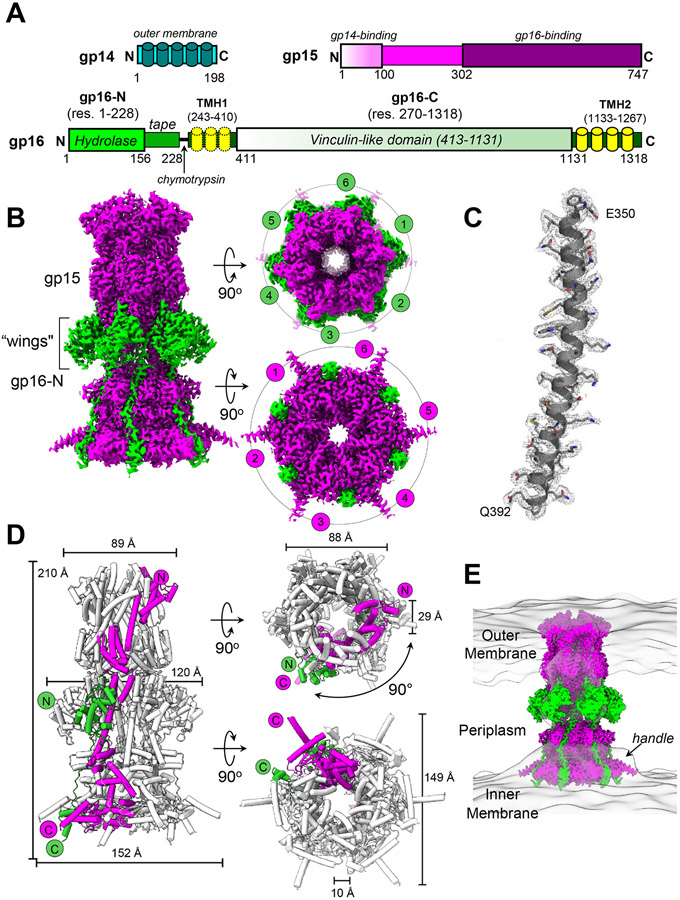

Figure 1. The periplasmic tunnel of the T7 DNA-ejectosome.

(A) Schematic diagrams of T7 gp14, gp15, and gp16. (B) 2.7 Å cryo-EM map of T7 PT with gp15 and gp16-N colored in magenta and green, respectively. The map is contoured at 3.5 σ above the background. (C) Representative electron density map at 3.0 σ overlaid to the refined model for gp15 residues 350-392. (D) Cartoon representation of T7 PT with α-helices represented as cylinders; only one protomer of gp15 and gp16-N are colored as in (A) while the rest of the structure is gray. (E) Overlay of T7 PT density in the 40 Å resolution cryo-ET density of T7 ejection proteins (map EMD-5534).

Cryo-EM structure of T7 PT at 2.7 Å resolution

We determined the structure of the gp15:gp16-N complex at 2.7 Å resolution using cryo-EM single-particle analysis (Figures 1B and S3B; Table 1). 5,250 residues and 219 water molecules (Data S3C) were built de novo in the cryo-electron density, which is resolved to better than 2.4 Å resolution in many areas of the structure (Figures 1C and S4A,B). The final atomic model includes residues 57-706 of gp15 (Data S4A) and 1-228 of gp16 (Data S4B) and displays excellent stereochemistry and a map-to-model correlation coefficient of 0.92 (Table 1). Figure 1D illustrates the overall architecture of the gp15:gp16-N complex, which we will refer to as the PT of the T7 DNA-ejectosome. It contains six copies of gp15 bound to a stoichiometric number of gp16-N, with a total mass of 652.4 kDa. In side view, the T7 PT resembles a chess bishop, ~210 Å in length with a wide end (~150 Å in diameter) and a tapered end (~90 Å in diameter), long enough to span the entire gram-negative periplasm (Bhardwaj et al., 2011). The core of T7 PT (4,440 residues) comprises six helical protomers of gp15 that spiral around a central 6-fold axis, forming a twisted hollow tube. Six gp16-N proteins decorate the outside of the tunnel, running roughly parallel to the central 6-fold axis and forming lateral protrusions that resemble wings (Figure 1B). Notably, the cryo-EM structure of T7 PT presented here fits closely with the tube-like density observed in the tomographic reconstruction of phage T7 infecting E.coli minicells (Hu et al., 2013) (Figure 1E). The tapered end of PT contacts gp14 at the OM (Chang et al., 2010a), while the wider end forms a large surface of contact with the inner membrane (IM).

Table 1.

Cryo-EM data collection, refinement, and validation statistics

| Data Collection and Processing |

gp15:gp16-N | gp16-C:2N2:PG | 2N2:PG |

|---|---|---|---|

| Magnification | 81,000X | 190,000X | 190,000X |

| Voltage (kV) | 300 | 200 | 200 |

| Electron exposure (e−/Å2) | 50 | 80 | 80 |

| Defocus range (um) | −1.0 to −2.5 | −0.25 to −3.0 | −0.25 to −3.0 |

| Pixel size (Å) | 0.54 (1.08) | 0.74 | 0.74 |

| Initial particle images (no.) | 4,729,536 | 637,588 | 23,796 |

| Final particle image (no.) | 208,024 | 9,018 | 11,030 |

| Map resolution (Å) | 2.7 | 15 | 17.8 |

| FSC threshold | 0.143 | 0.143 | 0.143 |

| Map resolution range (Å) | 2.4 - 5.6 | 8.5-13 | 15-24 |

| Refinement | |||

| Initial model used (PDB code) | RELION de novo model from 1,486,209 particles | ||

| Model resolution (Å) | 2.7 | ||

| FSC threshold | 0.143 | ||

| Map sharpening B factor (Å2) | −50 | ||

| Model composition | |||

| - Non-hydrogen atoms | 41,547 | ||

| - Protein residues | 5268 | ||

| - Ligands (water) | 19 | ||

| B factors (Å2) | |||

| - Protein | 45.1 | ||

| - Ligand (water) | 42.5 | ||

| R.M.S. deviations | |||

| - Bond lengths (Å) | 0.003 | ||

| - Bond angles (°) | 0.530 | ||

| Validation | |||

| - MolProbity score | 1.45 | ||

| - Clashscore | 5.57 | ||

| - Poor rotamers (%) | 0.00 | ||

| Ramachandran plot | |||

| - Favored (%) | 97.16 | ||

| - Allowed (%) | 2.84 | ||

| - Disallowed (%) | 0.00 |

Gp15 forms a tube for DNA delivery through the periplasm

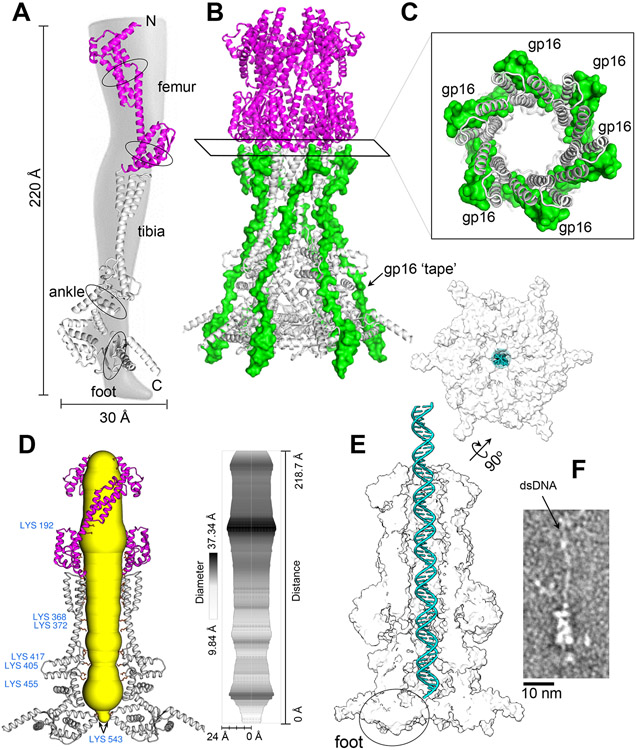

Gp15 folds into a 220 Å elongated helical protein that is hexameric in complex with gp16-N (Figure 1D). The gp15 tertiary structure resembles a leg with four distinct regions that, by analogy with the human limb, we named femur, tibia, ankle, and foot (Figure 2A). The maximum diameter of a gp15 monomer is only ~30 Å, roughly equal to the diameter of the T7 portal protein tunnel (Cuervo et al., 2019) through which gp15 is ejected at infection. Gp15 is monomeric on its own (Figure S1D) but hexameric in complex with gp16-N (Figure 1B): the cryo-EM structure reveals the molecular basis for gp15 oligomerization. A stretch of 71 residues in gp16-N (157-228), which we refer to as "molecular tape" (colored in green in Figure 2B), stabilizes the gp15 hexameric structure by cementing the gp15:gp15 dimerization interface at three points of contact (Figure S5A). The free energy of assembly formation for a pair of gp15 subunits decreases from −13.2 to −49.2 kcal/mol in the presence of gp16-N, which stitches two-thirds of gp15 length. A section through gp15 at the junction between the femur and tibia (Figure 2C) reveals that gp16 forms a cage surrounding six gp15 protomers, which generates a thermodynamically stable tube.

Figure 2. Architecture of gp15 DNA tunnel.

(A) Ribbon diagram of gp15 protomer colored with the femur in magenta and the rest of the protein in gray. Circled areas are potential points of conformational motion. (B) Quaternary structure of the hexameric gp15 bound to six copies of gp16 molecular tape (residues 157-228, colored in green). (C) Magnified view of the gp15:gp16 DNA tunnel cross-section at the junction between the gp15 femur and tibia. (D) (Left) Gp15 DNA tunnel in yellow with the central most lining residues in orange. Only two gp15 protomers are shown. (Right) Aligned gp15 DNA-tunnel diameter calculated using MOLE 2.0. (E) Van der Waals surface of T7 PT filled by a dsDNA 70-mer (cyan). Gp15 DNA tunnel fits a total of 56 base pairs and is gated at the IM. (F) Representative micrograph of negatively stained gp15:gp16 bound to a ~1,100 bps dsDNA fragment.

Along its inner surface, the diameter of the gp15 tunnel varies between ~38 Å (at residue K192) and ~21 Å (at residue K405) (Figures 2D). Each of the six gp15 chains exposes 21 residues lining the tunnel. Of those, six are negatively charged, seven are positively charged, and eight are neutral at pH 7.0. Many charged residues engage in electrostatic contacts among neighboring subunits, which results in a relatively neutral charge distribution (Figure S5B). The only exception is a basic gear formed by gp15 K405/K417/K455 close to the IM, while residues by the OM have a slightly more negative charge distribution. Overall, the gp15 DNA tunnel provides a snug fit for DNA, which is ~22 Å in cross-sectional diameter in its hydrated form (Lokareddy et al., 2017), but likely loses the outer hydration shell during ejection (Molineux and Panja, 2013) (Figure 2E). The DNA tunnel diameter narrows down at the tip proximal to the IM, which has a maximum opening of only ~9 Å. K543 generates this constriction in the gp15 foot (Figures 2D-E) that lays orthogonal to the tibia, at a position analogous to the "heel" of the gp15 foot. The DNA tunnel internal diameter in this portion of gp15 (Figures 2D-E) is insufficient for DNA passage. The total length of the DNA tunnel from the gp14 tip to the IM restriction is ~190 Å, enough to accommodate ~56 bp of elongated uncoiled B-DNA (Kuhn and Kellenberger, 1985; Molineux and Panja, 2013). To validate this prediction, we incubated gp15:gp16 with a linear 1,100 bps double-stranded DNA (dsDNA) and visualized the complex by negative staining EM. In some micrographs, we observed dsDNA threaded inside the PT, going through the tapered end of gp15, but not coming out of the wide end, where gp16 binds, which is gated (Figure 2F). Thus, the gp15 hexamer spans the entire periplasm but is not likely to form a pore through the IM for DNA passage.

Structure of gp16-N

The N-terminal 156 residues of gp16-N adopt a transglycosylase fold that makes up the wings of the ejectosome (Figure 1B). C-terminal of this domain, gp16 residues 157-228 form the molecular tape cementing gp15 hexamer, as described above (Figures 2B, C). Notably, the six copies of gp16-N in the cryo-EM reconstruction do not form a stable quaternary structure in the absence of gp15 (Figure 3A), as seen in solution (Figure S2A). The only point of contact between gp16-N protomers is a van der Waals bond between R114 and N7, which is insufficient to hold together a gp16 oligomer in the absence of the gp15 tube. The electron density for gp16 in the transglycosylase domain is less well resolved than in the tape region (Figure S4A), as the wings deviate from the 6-fold rotational symmetry seen for the gp15 tube. We used symmetry expansion followed by focused classification and refinement to improve the density in the gp16-N (Figures S4D, E) that allowed us to assign all residues in the wings unambiguously (Figure 3B). A superimposition of gp16-N with the 27% identical transglycosylase SLT70 from E.coli (Thunnissen et al., 1995) (Figure 3B) reveals a conserved fold (RMSD ~2.6 Å) characterized by a deep catalytic cleft. Bulgecin A, a transglycosylase inhibitor co-crystallized with SLT70 (Thunnissen et al., 1995), fits accurately inside the gp16-N substrate-binding pocket, lined by the putative catalytic residue E37 (Figure 3B). This prediction is consistent with the report that a mutant virion containing the mutation E37F in gp16 is defective in cell wall hydrolysis and exhibits delayed DNA entry into the cytoplasm (Moak and Molineux, 2000, 2004). Interestingly, the gp16-N active site clefts face toward the gp15 tibias instead of projecting outward (Figure 3C). The relative motion of gp16 wings around gp15 may allow peptidoglycan units to reach inside the active site cleft while the ejectosome assembles in the periplasm.

Figure 3. Topology of the large ejection protein gp16.

(A) Top (left) and side (right) views of the six gp16-N protomers built in the cryo-EM reconstruction. Only one protomer is colored in green, with the other five in gray. A semitransparent solvent surface is overlaid to the final model shown as ribbons. Only one point of contact, between R114 and N7, exists between gp16-N protomers. (B) Secondary structure superimposition of the T7 gp16-N residues 1-156 (green) and E.coli SLT70 residues 445-618 (gray) transglycosylase domains. The RMSD is 2.6 Å. Bulgecin A and gp16 active site residue E37 are shown as sticks. (C) Model of one gp16 protomer (green) bound to the T7 PT (semitransparent solvent surface). Gp16-N forms the wings in the periplasm, while gp16-C spans the IM and projects a folded VLD-domain in the host cytoplasm. The red star indicates the catalytic residue E37. The regions of gp16-C that cross the IM (labeled as TMH1 and TMH2) are predicted by MemBrain (Yin et al., 2018) to contain several transmembrane helices, shown in the zoomed-in panels (D) and (E).

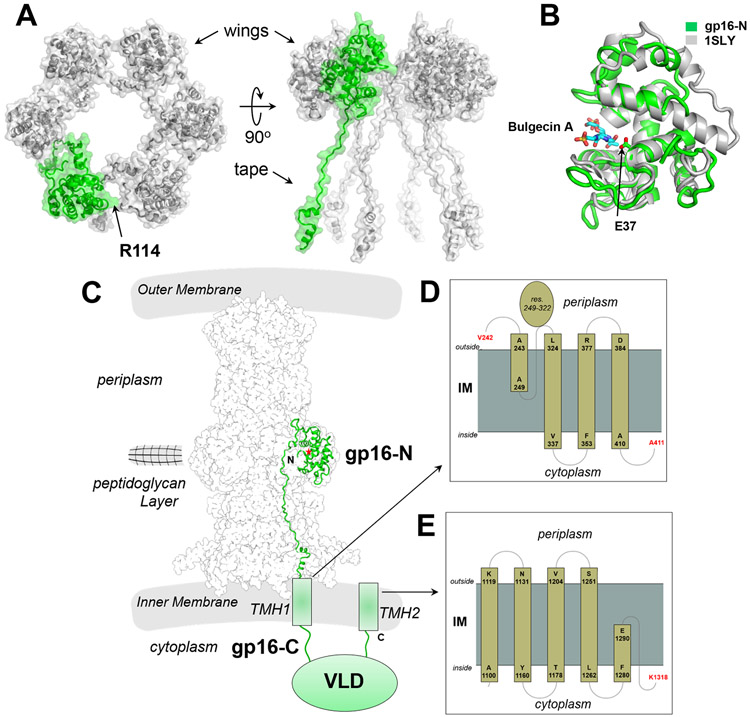

Gp16-C forms a DNA-binding hub

Using the 3D-structure of gp15:gp16-N as a template, we built a topological model of the full-length gp16 (Figure 3C). The ~1,100 residues of gp16 located C-terminal of residue 228 are poorly characterized (Figure 1A). We generated a low-resolution negative stain reconstruction of gp16-C, which revealed a trapezoidal shape with approximate dimensions 105x80x40 Å (Figure S6A, B). The central core of gp16-C (residues 362-1131) is homologous to Vinculin, an all-helical protein involved in cell adhesion. The two sequences have an overall identity and similarity of 18.4% and 26.7%, respectively (Data S5), which allowed us to generate a low homology model of the gp16-C Vinculin-like domain (gp16-VLD). Interestingly, gp16-VLD consists of a flat helical stack of approximate dimensions 90x80x35 Å that fits well in the negative stain reconstruction of gp16-C (Figure S6B). As previously pointed out, the cryo-ET of T7 infecting minicells identified a toroid-density of ~300x60 Å with a ~40 Å central cavity arranged below the PT inside the host cytoplasm (Hu et al., 2013). This toroid density, hypothesized to be part of the motor that pulls the genomic DNA end into the cell (Chang et al., 2010a; Kemp et al., 2004; Molineux, 2001), was not assigned to gp15 or gp16, which Hu et al. thought form only the periplasmic tunnel (Hu et al., 2013). We computationally extracted the toroid density from the deposited cryo-ET map (EMD-5534) and docked six copies of gp16-VLDs inside the low-resolution density (Figure S6C). The docking model suggests gp16-C, which has a flat shape (see side view in Figure S6C), may form a hexameric assembly under the IM, possibly interacting with the viral genome as it comes out of the PT. In support of this idea, we found that purified gp16-C has saturable sequence-independent binding to DNA in vitro, which was not observed for gp16-N (Figure 4A). Mutations responsible for the transcription-independent ejection of the T7 genome (Struthers-Schlinke et al., 2000) cluster between gp16-VLD residues 730-860 (underlined residues in Data S6), reinforcing the link between this domain and genome ejection.

Figure 4. Gp16-C has DNA-binding activity.

(A) EMSA of a Cy3-labelled DNA incubated with increasing concentrations of gp16-N and gp16-C. The gel on the right was stained by Coomassie blue; on the left is the same gel exposed at ~550 nm to detect Cy3-fluorescence. (B) Collage of representative negatively stained electron micrographs of the full-length gp15:gp16 complex. The top two rows depict representative side views, while the bottom rows show the complex top/bottom views. The magenta and green arrows indicate the PT and gp16-C globular domains surrounding the PT, respectively.

To visualize gp16-C in the context of the assembled DNA-ejectosome, we formed a complex of the full-length gp16 bound to gp15 (Figure S2B) and subjected it to negative-stain EM. We observed screw-like particles resembling T7 PT (Figure 4B, magenta arrows) with up to six globular appendices facing the wide end of gp15, differentially arranged in various complexes (Figure 4B, green arrows). We ascribed these globular domains to gp16-VLD (Figure 3C, S6B) within gp16-C. The connection between PT and gp16-C is flexible in the absence of a lipid bilayer. Likewise, gp16-C does not self-associate in solution (Figure S2D), suggesting the quasi-hexameric and hollow conformation of gp16-C inferred from the tomographic reconstruction (Figure S6C) forms only when gp16 is bound to gp15 and inserted in the IM.

Gp16-C has lipid-binding activity

Gp16 contains two spatially distinct sets of predicted transmembrane helices (TMH) (Lupo et al., 2016; Molineux, 2001) flanking the VLD that we named TMH1 and TMH2 (Figures 3C-E). Similarly, the homologous ejection protein in P22, also known as gp16 (Data S1), can partition itself into liposomes preloaded with a fluorescent dye promoting the release of the dye (Perez et al., 2009). Unlike P22 gp16, which is nearly half of the T7 gp16 molecular mass, both the full-length gp16 and gp16-C are fully water-soluble and monodisperse in solution (Figures S2A and S2D), suggesting the TMHs are likely not exposed in the absence of a membrane. In a nanodisc-association assay, gp15 alone failed to interact with lipid nanodiscs (Figures 5A, B), reinforcing the idea this ejection protein forms a DNA tube that contacts but does not penetrate the bacterial IM. In contrast, both the full-length gp16 (Figures 5A, B) and gp16-C, but not the shorter gp16-N (Figures 5C, D), comigrated with nanodiscs on a size exclusion column. These data demonstrate that gp16-C has lipid-binding activity, which is likely conferred by the predicted TMHs (Figure 3D, E). Unfortunately, deletion constructs of gp16-C lacking either set of helices were largely insoluble, suggesting that TMH1 and TMH2 bind each other in the context of gp16-C, neutralizing hydrophobic groups. Vitrified lipid nanodiscs decorated with gp16-C revealed a statistically significant density emerging from both sides of nanodiscs (Figure 5E), not observed in the empty nanodisc (Figures S6D, E). A low-resolution cryo-EM reconstruction of gp16-C bound to nanodiscs revealed gp16-C goes through the membrane lipid bilayer (Figure 5F), adopting a very asymmetric structure. A larger lobe of density that we arbitrarily oriented below the membrane (symbolizing the host IM) possibly represents the gp16-VLD. In contrast, a thinner, handle-shaped density positioned onto the lipid membrane may represent residue 249-322 of gp16-C TMH1 that is predicted to emanate in the periplasm (Figure 3D). This density also appears in the cryo-ET as a bulging of the IM at the periplasmic surface (Figure 1E). Thus, gp16-C traverses the lipid nanodisc membrane, possibly using its two sets of transmembrane helices clustered in TMH1 and TMH2 (Figure 3C).

Figure 5. The lipid-binding activity of gp16-C.

SEC analysis of purified (A) full-length gp15 and gp16 and (C) gp16-N, and gp16-C alone (shown as dashed lines) and after incubation with lipid nanodiscs (solid lines). Empty nanodiscs containing just the scaffolding protein 2N2 are shown as a solid black (in A) and gray (C) line. Arrows indicate the elution volumes of M.W. markers. (B and D) SDS-PAGE analysis of fractions eluted in panels (A) and (C), respectively. (E) Representative 2D-class averages of vitrified gel filtration purified gp16-C:nanodiscs complex (for comparison, empty nanodiscs are in Figure S6D, E). (F) Cryo-EM density of gp16-C bound to a nanodisc at 15 Å resolution. The nanodisc is colored in gray, while gp16-C, which crosses the lipid bilayer, is green.

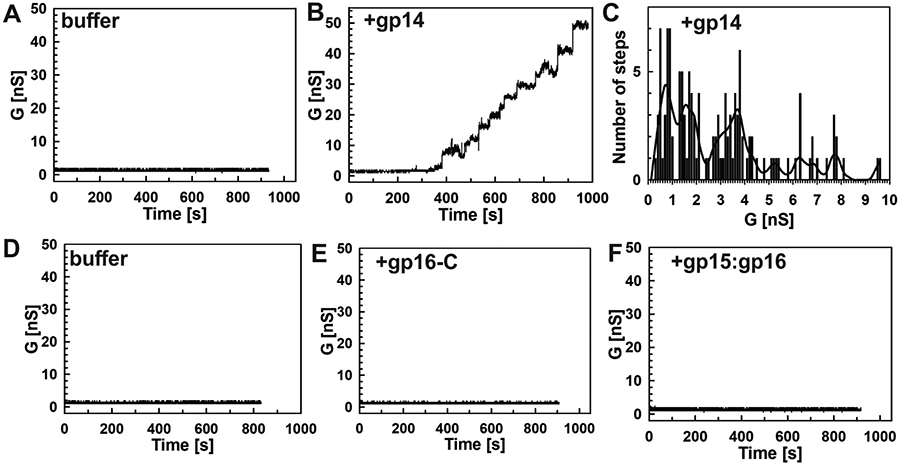

Lipid bilayer experiments with T7 ejection proteins

The function of the T7 ejectosome requires the presence of a continuous channel from the phage head to the cytoplasm of an E. coli cell. However, it is unclear whether the ejectosome proteins form open channels in vitro in the absence of complex formation or phage and cellular signals. To examine the channel-forming properties of individual ejectosome proteins, we performed lipid bilayer experiments as described previously (Heinz and Niederweis, 2000). To this end, the gp14 protein was solubilized in a buffer containing 0.2 mM n-dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM), while all other ejection proteins, including the gp15:gp16 complex, were solubilized in a buffer without detergent. For gp14, the DDM-buffer used to solubilize gp14 alone did not change the baseline current in lipid bilayer experiments (Figure 6A), demonstrating that the detergent alone does not perturb the lipid membrane. In contrast, the addition of purified gp14 protein at concentrations ranging from 500 ng/ml to 2.2 μg/ml resulted in a step-wise current increase indicative of insertions of open, water-filled channels into the lipid bilayer (Figure 6B, and S7A). We recorded a total of 130 channels in 12 different membranes using different fractions of the gp14 protein after gel filtration and observed an unusually wide distribution of conductance values with discernible peaks at 0.9 nS, 1.4 nS, and 3.8 nS and less frequent events with larger conductances (Figure 6C). We also examined the individually purified gp16-C domain (Figure 6D, E, and S7B), as well as the gp15:gp16 complex (Figure 6D, F, and S7C) in lipid bilayer experiments. However, neither of these proteins had channel activity in our experiments. Sporadic current spikes for the gp15:gp16 complex (Figure S7C) were inconsistent with a stably populated pore in the lipid bilayer, suggesting the gp15:gp16 complex does not form a stable pore in the membrane.

Figure 6. Channel activity of purified ejection proteins in lipid bilayer experiments.

All experiments were performed with diphytanoyl phosphatidylcholine (DphPC) membranes bathed in a buffer containing 1 M KCl and 10 mM HEPES (pH 7.4) and at −10 mV potential. The samples were added to both sides of the cuvette. After membrane formation current traces were recorded for 15 minutes. (A) Current trace of a DphPC membrane in 120 μl DDM (0.2 mM) buffer. Three membranes were recorded, and no activity of the buffer was observed. (B) Representative current trace of gp14 protein (1.8 μg/ml) in buffer containing 0.2 mM DDM. Insertions of open channels into the membrane were observed at protein concentrations ranging from 540 ng/ml to 2.2 μg/ml. (C) Histogram of single-channel conductances of gp14. A total of 130 events from 12 different membranes were recorded and analyzed. Channel populations centered around conductance of 0.9 nS, 1.4 nS, and 3.8 nS. The line curve represents smoothed data for better visualization. (D) Current trace for DphPC membrane with 250 μl of Tris-citrate buffer (pH 8.0). Three different membranes were recorded for each protein, and no activity was observed. (E) Current trace of gp16-C (3 μg/ml). No insertions were observed at concentrations ranging from 176 ng/ml to 3 μg/ml. (F) Current trace of the gp15:gp16 complex (3.1 μg/ml). Sporadic current spikes were observed at concentrations ranging from 200 ng/ml to 3.1 μg/ml (also see Figure S7).

DISCUSSION

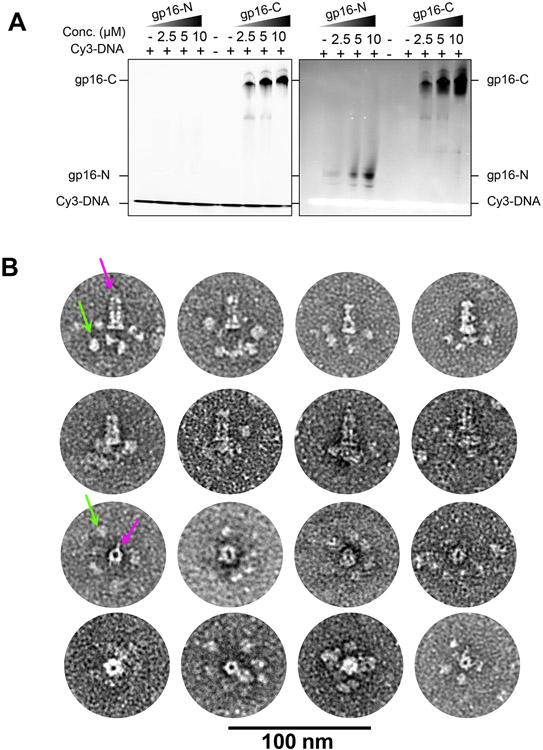

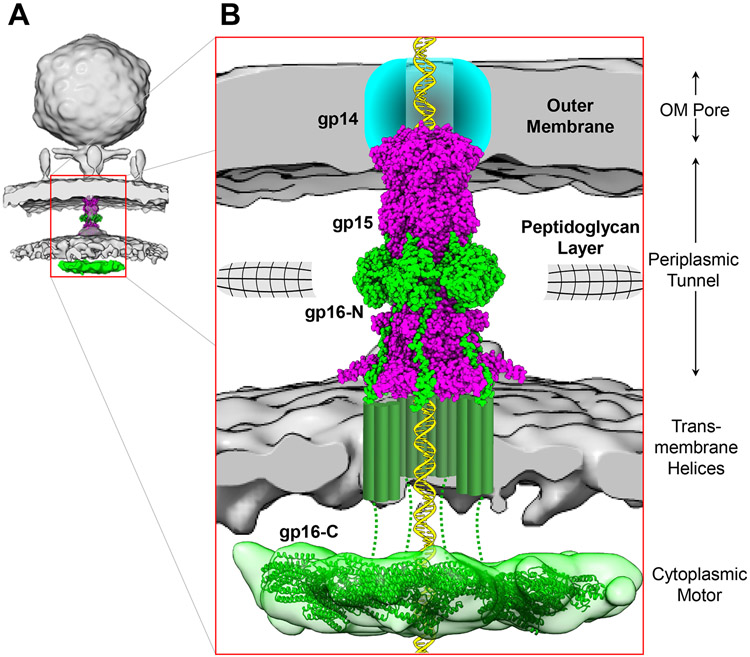

This study describes 3D-structures of viral ejection proteins. By combining biochemical, structural, biophysical, and modeling approaches, we generated a composite model of the T7 DNA-ejectosome (Figures 7A, B). This molecular machine consists of three discrete components: an OM channel formed by the membrane protein gp14, a PT built by six copies of gp15 bound to six hexamerically arranged gp16-N domains, and a large cytoplasmic hub formed by six gp16-C that exhibits DNA-binding activity (Kemp et al., 2004). This work provides a framework to decipher the mechanisms by which the DNA-ejectosome mediates phage genome-translocation into bacteria.

Figure 7. A model of the T7 DNA Ejectosome.

(A) Cryo-ET reconstruction of T7 infecting E. coli (map EMD-5534) fit with the solved PT structure. Gp15 is colored in magenta and gp16 in green, including the toroid density observed in the host cytoplasm. (B) Zoom-in view of the entire T7 DNA ejectosome that consists of three parts: an OM pore formed by gp14, a PT consisting of six protomers of gp15 bound to gp16-N, and a cytoplasmic hub composed of gp16-C. The composition of the gp16 channel in the IM (green cylinders) and the residues connecting to the toroid density in the host cytoplasm (dashed lines) are hypothetical.

Stoichiometry and symmetry mismatches in the T7 DNA-Ejectosome

The T7 PT composition elucidated in our cryo-EM reconstruction is somewhat unexpected based on the stoichiometry of gp15 and gp16 inferred from symmetrized low-resolution cryo-EM reconstructions of the T7 procapsid and mature virion (Agirrezabala et al., 2005; Cerritelli et al., 2003; Guo et al., 2013). Notably, 8 and 4 copies of gp15 and gp16 are concentrically stacked onto the portal protein and visible after applying symmetry, which might differ from the total number of ejection proteins available in the T7 capsid before their ejection. While a loss of two gp15 subunits upon ejection is plausible, yielding the six seen in our T7 PT reconstruction, more difficult to reconcile is the presence of six fully occupied gp16-N in our reconstruction given the four seen in the virion. The atomic structure of the T7 PT helps us to solve this apparent conundrum. The 2:1 stoichiometry of gp15:gp16 observed in the T7 procapsid and mature virion is incompatible with the design principles of the DNA-ejectosome elucidated in this paper (Figure 1C). Both gp15 and gp16 are monomeric in solution (Figures S1D and S2A) but assemble into a hexameric complex upon stabilization of the gp15:gp15 binding interface by gp16, which decorates the outside of the gp15 tube (Figure 2C). The stoichiometric association of gp15 and gp16 is essential to generate a stable hexameric quaternary structure wide enough to accommodate DNA (Figure 2E, F). In contrast, a hypothetical assembly formed by eight copies of gp15 bound to only four gp16s lacks structural stability as only four of the eight gp15:gp15 binding interfaces would be cemented by gp16, insufficient to generate a quaternary structure from a monomeric protomer. Thus, we propose a symmetry mismatch between the pre- and post-ejection conformation of gp15 and gp16 accompanies the assembly of ejection proteins into a DNA-ejectosome. We posit that additional gp16 subunits are present inside the virion but not ordered in the core stack, as observed for P22 (Wang et al., 2019). In this close relative to T7, the ejection proteins are asymmetrically arranged inside the capsid, clustered loosely around the portal protein (Wu et al., 2016), and undiscernible in all cryo-EM reconstructions (Chen et al., 2011; Tang et al., 2011). An alternative possibility is that T7 gp16 functions in trans during infection, as reported for P22 gp16 (Hoffman and Levine, 1975a, b). T7 gp16 carries both a peptidoglycan hydrolytic domain and lipid-association activity and could diffuse two-dimensionally across the IM and stochastically encounter and stabilize ejection proteins in the bacterial periplasm.

The ejection protein fold reveals intrinsic structural plasticity

Our high-resolution reconstruction reveals gp15 fold consists of a collection of α-helical segments flexibly connected by at least 4 points of articulation (Figure 2A). Such a 'sticks-on-a-string' architecture is expected to be very plastic, allowing helical segments to collapse onto each other like a folding cane and adopt a compact structure. This structural plasticity might explain how gp15 is globular and compact in the core stack, in the pre-ejection conformation, but turns into a DNA-tube post-ejection. Notably, our work establishes that gp15 lacks the capability for membrane penetration on its own (Figure 5A, B) but instead serves as a connector between the gp14 channel at the OM (Chang et al., 2010a) and a second, less characterized channel that forms at the IM to allow DNA ejection into the host.

Like gp15, the larger ejection protein gp16 is formed by different helical domains flanked by flexible linkers. The atomic structure of the gp16 C-terminus (228-1318) is unknown. However, CD spectroscopy (Figure S2E), a low-resolution negative stain reconstruction of gp16-C (Figure S6A, B), homology modeling, and the toroid density extracted from the cryo-ET reconstruction of T7 infected cell (Figure S6C) all suggest a flat, α-helical fold, possibly similar to a folded conformation of gp15. Notably, gp15 and gp16 share 19.3% sequence identity and 28.1% similarity between residues 362-1318 (Data S7), suggesting the helical domain of gp16-C and the gp15 tunnel, both involved in DNA-binding, could be evolutionarily related and perhaps structurally similar. In contrast, the gp16-N transglycosidase domain was likely acquired during the evolution of different phages and is not present, for instance, in Salmonella phages (Data S1). Also, the conservation of TMH1/2 is not very high (Data S2), though both gp16 characterized so far, from P22 (Perez et al., 2009) and T7 (this paper) have lipid-binding activity, possibly underscoring different strategies to cross or insert into the IM.

A model for sequential assembly of the T7 DNA-ejectosome

In our assembly studies (Figures S2B and S3A), the DNA-ejectosome was most efficiently formed from diluted solutions of gp15 and gp16 that associate together when co-expressed in bacteria (data not shown), as also reported for phage P22 homologous factors gp20 and gp16 (Data S1) (Thomas and Prevelige, 1991). It is possible, these two ejection proteins form a complex inside the virion and are ejected together as a heterodimer. Assembly of the DNA-ejectosome in the periplasm requires vast conformational rearrangements and a great degree of sequentiality to coordinate the refolding of three ejection proteins. We suggest a model for sequential assembly of the T7 DNA-ejectosome based on data presented in this paper and available in the literature. First, gp14 is ejected from the virion and forms a pore in the OM (Chang et al., 2010a), consistent with the need for detergent solubilization in vitro (Figure S1A). In lipid bilayer experiments, gp14 was the only ejection protein to form a constitutively open pore, which allowed for a robust ion flux (Figure 6B, C). We speculate that the gp14 pore in the OM is circumcentric to the portal protein opening (Cuervo et al., 2019), allowing DNA entry into the periplasm. Second, gp15 and gp16 are ejected as a heterodimer through the portal/gp14-channel with gp15 already in an extended conformation (Figure 2A), thin enough to be expelled through this channel (Cuervo et al., 2019). Gp15 post-ejection conformation differs from the core stack seen in the T7 procapsid (Guo et al., 2013), which is also found in similar phages (Chang et al., 2010b; Jiang et al., 2006; Liu et al., 2010). This suggests that the gp15 slender, leg-shaped conformation bound to gp16-N forms in the virion upon propagating a signal for ejection to the core stack. Gp16-N could be the first moiety of the gp15:gp16 heterodimer to emerge from the portal protein into the periplasm, given its role in peptidoglycan hydrolysis. Third, gp15 subunits are sequentially ejected and oligomerize in the presence of a stoichiometric number of gp16-N tape regions. We propose that the pressure of DNA ejected from the capsid triggers a conformational change in T7 PT at the articulation between the gp15 foot and ankle (Figure 2A) that expands the gp15 tube and powers the passage of gp16 through the IM and formation of a channel. The pore for DNA passage at the IM is assembled by TMH1/2 concomitantly with a conformational change in the gp15 foot. We speculate gp16-C tethers the end of the T7 genome, surrounding it into the IM and escorting it through the periplasm into the host cytoplasm. Notably, in lipid bilayer experiments, the gp15:gp16 complex was not in a conformation capable of integrating into membranes, or the channel was not completely open to generate a measurable ion flux (Figure 6F). This suggests that the gp15:gp16 complex only opens in the inner membrane when the full ejectosome is assembled together with gp14 and when DNA is expelled through the cell envelope. Such a mechanism is consistent with the need for a viable cell to preserve ion gradients across the inner membrane (e.g., H+, Na+, etc). The DNA-translocating pore formed by TMH1/2 must be transient and close spontaneously once the DNA has been delivered into the bacterial cytoplasm, as proposed for Epsilon15 (Chang et al., 2010b), based on the lack of K+ efflux from cells during T7 infection (Kuhn and Kellenberger, 1985; Molineux and Panja, 2013). Gp14 instead forms a constitutively open pore at the OM, allowing the passage of ions into the periplasm. Fourth, in the host cytoplasm, six gp16-C self-associate into a toroid-like structure seen in the cytoplasm of infected cells (Hu et al., 2013) (Figure S6C). Gp16-C is monomeric in solution (Figure S2D), suggesting oligomerization is possible when the full-length gp16 is membrane-associated. In vitro assembled gp15:gp16 complex revealed globular domains loosely arranged around the PT that we interpreted as gp16-C (Figure 4B). The linker regions between the N- and C-terminal domains of gp16 containing TMH1/2 adopt a random coil conformation in the absence of lipids but can span the IM during ejection or the nanodisc lipid bilayer in our studies (Figure 5E, F). Such drastic conformational changes are commonly observed for bacterial pore-forming toxins, which switch from water-soluble monomers to transmembrane assemblies upon contact with a membrane and other signals (Dal Peraro and van der Goot, 2016). In summary, the degree of conformational changes necessary to fold a ~0.5 MDa DNA tube across the bacterial cell envelope requires extreme structural plasticity in both gp15 and gp16, which is provided by a segmented helical structure.

Gp16 mediates DNA-ejection into the bacterial cytoplasm

Perhaps the most unexpected finding of this study is the multifaceted structure and function of gp16, which coordinates four distinct activities essential for viral genome ejection. At the N-terminus: (i) gp16 transglycosylase domain degrades the peptidoglycan, opening a hole in the peptidoglycan layer that allows gp15 to oligomerize; (ii) gp16 molecular tape stabilizes the gp15:gp15 dimeric interface (Figure S5A) yielding a hexameric quaternary structure otherwise unstable in the absence of gp16. At the C-terminus: (iii) gp16-C exerts sequence-independent DNA-binding (Figure 4A) via a poorly characterized Vinculin-like domain that forms a hub in the host cytoplasm previously observed in the tomographic reconstruction of T7 infecting E.coli (Hu et al., 2013); (iv) two clusters of TMHs (Figure 3C-E) flanking the VLD mediate lipid insertion (Figure 5A-D) allowing the gp16 polypeptide chain to cross the IM twice (Figure 5E, F).

Our work suggests that nearly half of the DNA-ejectosome mass extends in the host cytoplasm, where gp16-C forms a large DNA-binding hub consistent with the toroid density observed in the tomographic reconstruction but not thought to be a part of the ejectosome itself (Hu et al., 2013). Interestingly, this hollow density lays ~120 Å below the IM and connects to the periplasmic core of the DNA-ejectosome via flexible linkers, invisible at subnanometer resolution (Figure 7B), same as in the reconstituted gp15:gp16 complex the linkers connecting gp16-Cs to the PT are invisible in the absence of a lipid bilayer (Figure 4B). We propose the gp16-C hub identified in this work promotes the active translocation of the first 850 bp of the 40 kb genome of T7 (Struthers-Schlinke et al., 2000), which are ejected via a transcription-independent process. The gp16 VLD serves as the critical determinant for DNA pulling and a structural scaffold for recruiting host factors that facilitate the internalization of the T7 genome. Transcription-independent translocation of the leading end of the T7 genome occurs at ~70 bp/sec at 37°C (Chang et al., 2010a), consistent with an enzyme-catalyzed reaction. Gp16-C alone, or in complex with a host protein, is the most likely factor implicated in DNA-pulling activity (Garcia and Molineux, 1996).

Limitations of the Study

This paper sheds light on the architecture of the prototypical DNA-ejectosome of phage T7. Our work paves the way to decipher the enzymology of genome ejection as it pertains to gp16 and the host factors involved in genome ejection. Given the size, complexity, and conservation of ejection proteins in Podoviridae, deciphering the detailed mechanism of genome ejection through the ejectosome will require a concerted effort by many laboratories. A structural repertoire of DNA ejectosomes is ultimately needed to understand how different bacteriophages eject their genomes across the cell envelope of Gram-negative bacteria.

STAR Methods

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead Contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Dr. Gino Cingolani (gino.cingolani@jefferson.edu).

Materials Availability

All reagents generated in this study are available from the Lead Contact with a completed Materials Transfer Agreement.

Data and Code Availability

The data generated during this study are available at PDB:7K5C and EMD-22680 for the gp15:gp16-N complex.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND SUBJECT DETAILS

BL21 (DE3) E. coli and C43 (DE3) E. coli were used for recombinant protein expression.

METHOD DETAILS

Generation of gp16-N, gp16-C, and gp16-C Mutants

Gene 14, 15, and 16 (Lupo et al., 2016) were originally amplified from T7 phage and cloned in the expression vector pET-16b (Sigma-Aldrich) (plasmids pET-16b_gp14 and pET-16b_gp15 and pET-16b_gp16). Limited proteolysis of gp16 was carried out using chymotrypsin (purchased from Sigma) in a molar digestion ratio equal to 200:1 (w/w) gp16:chymotrypsin, as described (Cingolani et al., 2000). Gp16-C (res. 275-1318) was generated using PCR by amplifying Gp16 region 275-1318, which was then cloned into vector pGEX-6P-1 (GE Life Sciences) between restriction sites BamHI and EcoRI (plasmid pGEX-6P_gp16-C). Gp16-N (res. 1-228) plasmid (pET16b-gp16-N) was generated by introducing stop codon at position G229 in pET-16b_gp16, using site-directed mutagenesis. Gp16-C mutants containing just the VLD were generated by PCR and cloned into vector pGEX-6P-1 (GE Healthcare) between restriction sites BamHI and EcoRI.

Expression and Purification of gp15, gp16, and gp16-N

Recombinant gp15, gp16, and gp16-N were expressed and purified as previously described (Lupo et al., 2016) with some modifications. Gp15, gp16, and gp16-N in pET16b plasmids (see Generation of gp16-N, gp16-C, and gp16-C Mutants) were transformed by electroporation into BL21 (DE3) E. coli competent cells (Novagen) and plated onto Luria broth (LB) agar (Fisher) plates supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin (Inalco). The starter cultures in 250mL Erlenmeyer flasks (Pyrex) containing 100 mL of LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin were grown overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 200-250 rpm in an incubator shaker (New Brunswick Scientific) from a single colony. 6-5L glass Erlenmeyer flasks (Pyrex) containing 2 L LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin were inoculated with 10 mL starter cultures and grown at 37 °C with shaking at 200-250 rpm. After growth at 37 °C to an optical density at 600nm (OD600) of 0.6, gene expression was induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fisher), and the culture was shaken (200-250 rpm) at 37 °C for 2 h. Cells were harvested by centrifuging at 4,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C in a Sorvall BP 8 centrifuge (Thermo Scientific). The supernatants were discarded, and the cell pellets were resuspended in chilled Lysis buffer-I containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 100 mM NDSB-201 (Millipore), 10% glycerol (Alfa Aesar), and 1 mM Phenylmethylsulfonyl fluoride (PMSF) (Roche). The cell pellets were lysed by sonication in Lysis buffer-I using a S-4000 Ultrasonic Liquid Processor (Misonix) at 35% amplitude, process time 1:15 min:sec, pulse-on time 25 sec, and pulse-off time 25 sec. Supernatant from clarified lysate for gp15, gp16, and gp16-N was centrifuged at 18,000 rpm for 30 min in a Sorvall Lynx 4000 centrifuge (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a F21-8x50y FiberLite rotor (Thermo Scientific) was incubated with Ni-NTA resin (GoldBio) for 2 hrs with rotation at 4 °C, then washed with Ni-wash buffer-I containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM NDSB-201 (Millipore), 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, and 1 mM PMSF (Roche) supplemented with 10 mM imidazole (ACROS) followed by 50 mM imidazole. Proteins were eluted with Elution buffer containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 20 mM NDSB-201, 10 mM CaCl2, 10 mM MgCl2, 5% glycerol, 1 mM PMSF, and 800 mM imidazole. Protein-containing fractions were pooled and subjected to separation on a Superdex 200 16/60 gel filtration column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated with GF buffer-I containing 50 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 8.0, 100 mM sodium citrate, and 10 mM MgCl2. Gel filtration columns Superdex 200 10/300, Superose 12 10/300, and Superose 6 10/300 (GE Healthcare Life Sciences) were calibrated with molecular weight (MW) markers (29-700 kDa) via Gel Filtration Markers Kit (Sigma-Aldrich) and used to further polish proteins and estimate the MW of eluted species. Throughout the purification process, protein samples were taken and added to 5 uL of 5x loading dye containing 0.02% w/v Brilliant Blue G-250 (Fisher Bioreagents), 5% BME, and 30% glycerol and loaded on 13.7% or 18% Acrylamide/Tris/APS/TEMED electrophoresis gels (homemade) and ran alongside Precision Plus Protein™ Unstained standards (Bio-Rad) to determine purity and size in kDa. Protein concentration and protein vs. nucleic acid content (A280/A260) was measured spectrophotometrically using a DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix).

Expression, Purification, and Nanodisc Reconstitution of gp16-C

Gp16-C, and gp16-C mutants lacking TMH1, TMH2, TMH1/2, or gp16-C-VLD in pGEX-6P-1 plasmids followed the same expression and purification protocol as stated in the previous section (see Expression and Purification of gp15, gp16, and gp16-N) except the following: gp16-C was purified using GST glutathione resin (GoldBio) and attempts to purify gp16-C fragments lacking TMH1, TMH2, and TMH1/2 or containing just the VLD were unsuccessful due to the poor solubility of these deletion fragments. The GST tag cleaved with PreScission Protease (GenScript) was retained on the resin, while the eluted proteins were further polished by gel filtration using a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare). Membrane scaffolding protein 2N2 (MSP2N2) was expressed in BL21 (DE3) E. coli cells (Novagen) and purified as previously described (Tan et al., 2020). MSP2N2 plasmid (Tan et al., 2020) was transformed by electroporation into BL21 (DE3) E. coli competent cells (Novagen) and plated onto Luria broth (LB) agar (Fisher) plates supplemented with 35 μg/mL kanamycin (GoldBio). The starter cultures in 250mL Erlenmeyer flasks (Pyrex) containing 100 mL of LB broth supplemented with 35 μg/mL kanamycin were grown overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 200-250 rpm in an incubator shaker (New Brunswick Scientific) from a single colony. 6-5L glass Erlenmeyer flasks (Pyrex) containing 2L LB broth supplemented with 35 μg/mL kanamycin were inoculated with 10 mL starter cultures and grown at 37 °C with shaking at 200-250 rpm. After growth at 37 °C to an optical density at 600nm (OD600) of ~1.0, gene expression was induced with 0.5 mM IPTG, and the culture was shaken (200-250 rpm) at 28 °C for 4 h. Cells were harvested by centrifuging at 4,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C in a Sorvall BP 8 centrifuge (Thermo Scientific). The supernatants were discarded and the cell pellets were resuspended in chilled Lysis buffer-II containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, 200 mM NaCl, 20 mM MgSO4, 1 mM PMSF, and 0.5 mM tris(2-carboxyethyl)phosphine (TCEP) (Sigma-Aldrich). The cell pellets were disrupted by two passes through a Emulsiflex C3 high-pressure homogenizer (Avestin) at 1000 psi. The MSP2N2 lysate was clarified by ultracentrifugation at 34,000 rpm for 30 min at 4 °C using a Sorvall wX+ Ultra Series centrifuge (Thermo Scientific) and the recovered supernatant was supplemented with 50 mM sodium cholate and incubated with Ni-NTA resin (GoldBio) for 2 hrs with rotation at 4 °C. After packing the beads in a column, the resin was washed with Ni-wash buffer-II containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 40 mM Imidazole and MSP2N2 was eluted with Ni-elution buffer-I containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.5, 200 mM NaCl, 400 mM Imidazole, and 25 mM sodium cholate. The eluted protein was placed in Snakeskin™ Dialysis Tubing 10k MWCO (Thermo Scientific) containing TEV protease (GenScript) and gently agitated in Dialysis buffer-I containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0, and 150 mM NaCl. After dialysis, the mixture was repassed through Ni-NTA resin to recapture cleaved His-tags and TEV protease, and the flow-through was collected. Untagged MSP2N2 was further purified by gel filtration using a Superdex 200 16/60 (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated with GF-buffer-II containing 20 mM HEPES pH 7.0 and 150 mM NaCl. Nanodiscs were assembled as previously described (Tan et al., 2020) by mixing purified gp16-C at 2.5 mg/ml with 16:0-18:1 PG 1-palmitoyl-2-oleoyl-sn-glycero-3-phospho-(1'-rac-glycerol) (POPG) (Avanti Polar Lipids, Inc) at 15 mg/ml and untagged scaffolding protein MSP2N2 at 10.8 mg/ml, resulting in a molar ratio was 1:500:5. The mixture was incubated overnight in the dark at 4 °C, then injected on a Superdex 200 16/60 (GE Healthcare) column equilibrated with GF buffer-I containing 50 mM HEPES-NaOH pH 8.0, 100 mM sodium citrate, and 10 mM MgCl2. To further polish reconstituted gp16-C:2N2:PG nanodiscs, elutions containing the desired complex were gel filtrated a second time on Superdex 200 10/300 (GE Healthcare). Throughout the purification process, protein samples were taken and added to 5 uL of 5x loading dye containing 0.02% w/v Brilliant Blue G-250 (Fisher Bioreagents), 5% BME, and 30% glycerol and loaded on 13.7% or 18% Acrylamide/Tris/APS/TEMED electrophoresis gels (homemade) and ran alongside Precision Plus Protein™ Unstained standards (Bio-Rad) to determine purity and size in kDa. Protein concentration and protein vs. nucleic acid content (A280/A260) was measured spectrophotometrically using a DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix).

Expression and Purification of gp14

Gp14 in pET16b plasmid (pET-16b_gp14) was transformed by electroporation into C43 (DE3) E. coli competent cells (Biosearch Technologies) and plated onto Luria broth (LB) agar (Fisher) plates supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin (Inalco). The starter cultures in 250mL Erlenmeyer flasks (Pyrex) containing 100 mL of LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin were grown overnight at 37 °C with shaking at 200-250 rpm in an incubator shaker (New Brunswick Scientific) from a single colony. 6-5L glass Erlenmeyer flasks (Pyrex) containing 2L LB broth supplemented with 100 μg/mL ampicillin were inoculated with 10 mL starter cultures and grown at 37 °C with shaking at 200-250 rpm. After growth at 37 °C to an optical density at 600nm (OD600) of 0.6, gene expression was induced with 0.2 mM isopropyl β-d-thiogalactopyranoside (IPTG) (Fisher), and the culture was shaken (200-250 rpm) at 37 °C for 2 h. Cells were harvested by centrifuging at 4,000 g for 30 min at 4 °C in a Sorvall BP 8 centrifuge (Thermo Scientific). The supernatants were discarded and the cell pellets were resuspended in chilled Lysis buffer-I containing 50 mM HEPES pH 8.0, 300 mM NaCl, 100 mM NDSB-201, 10% glycerol, and 1 mM PMSF. The cell pellets were lysed by sonication in Lysis buffer-I using a S-4000 Ultrasonic Liquid Processor (Misonix) at 35% amplitude, process time 1:15 min:sec, pulse-on time 25 sec, and pulse-off time 25 sec. The lysate was then incubated with DNAse I (Roche), RNAse A (Roche), and additional PMSF on ice for 1 hour. Because gp14 was found to be completely insoluble, we enriched recombinant gp14 in the membrane fraction by collecting the pellets after ultracentrifugation for 45 min at 40k rpm, 4 °C using a Sorvall wX+ Ultra Series centrifuge (Thermo Scientific). The pellets were resuspended with Extraction buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 60 mM NaCl, 3 mM BME, 1 mM PMSF, and 1% N-lauroylsarcosine (NLS), or other detergents in the case of detergent screening, allowed to solubilize by rotating overnight at 4 °C, followed by centrifugation at 18,000 rpm for 30 min in a Sorvall Lynx 4000 centrifuge (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a F21-8x50y FiberLite rotor (Thermo Scientific) to remove membrane debris. The supernatant was incubated with Ni-NTA resin (GoldBio) for 2 hrs with rotation at 4 °C. After packing the beads in a column, the resin was washed with 10 CV Extraction buffer supplemented with 10% glycerol and 20 mM imidazole, followed by 50 mM imidazole. Gp14 solubilized in NLS was eluted with Ni-elution buffer-II containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, 3 mM BME, 0.8% NLS, and 500 mM imidazole. The eluted protein was placed in Snakeskin™ Dialysis Tubing 10k MWCO (Thermo Scientific) and gently agitated in Dialysis buffer-II containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 25 mM NaCl, and 0.8% NLS overnight at 4 °C. After dialysis, NLS-solubilized gp14 was gel filtrated on a Superose12 10/300 column (GE Healthcare) containing Dialysis buffer-II. Eluted NLS-solubilized gp14 was exchanged to 0.25% N-Dodecyl β-D-maltoside (DDM) (GoldBio) using ion-exchange affinity chromatography on a 5 mL Mono Q 5/50 GL column (Sigma-Aldrich) binding with Dialysis buffer-II containing 25 mM NaCl eluting with a gradient to a buffer containing 1 M NaCl and 0.25% DDM (instead of NLS). Flowthrough that exceeded the binding capacity of the column was re-run following the same salt gradient. Detergent exchanged DDM-solubilized gp14 was then subjected to gel filtration on a Superdex 200 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in DDM buffer containing 20 mM Tris-HCl 8.0, 150 mM NaCl, and 0.25% DDM. Using calibration markers via Gel Filtration Markers Kit (Sigma-Aldrich), we determined DDM-solubilized gp14 migrates as a ~150 kDa species. Throughout the purification process, protein samples were taken and added to 5 uL of 5x loading dye containing 0.02% w/v Brilliant Blue G-250 (Fisher Bioreagents), 5% BME, and 30% glycerol and loaded on 13.7% or 18% Acrylamide/Tris/APS/TEMED electrophoresis gels (homemade) and ran alongside Precision Plus Protein™ Unstained standards (Bio-Rad) to determine purity and size in kDa. Protein concentration and protein vs. nucleic acid content (A280/A260) was measured spectrophotometrically using a DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix).

Assembly and Purification of gp15:gp16 and gp15:gp16-N Complexes

The full-length gp15:gp16 complex was assembled by mixing 12.75 μM gp15 and 4.5 μM gp16 with a final molar ratio of ~3:1, and incubated on ice for 1 h. The complex was concentrated to one-third the original volume using a Vivaspin® 20, 100 kDa MWCO polyethersulfone concentrator (Millipore-Sigma) and subjected to gel filtration on Superose 6 10/300 GL column (GE Healthcare) equilibrated in Gel Filtration buffer-I. Peak fractions collected were taken and added to 5 uL of 5x loading dye containing 0.02% w/v Brilliant Blue G-250 (Fisher Bioreagents), 5% BME, and 30% glycerol and loaded on 13.7% or 18% Acrylamide/Tris/APS/TEMED electrophoresis gels (homemade) and ran alongside Precision Plus Protein™ Unstained standards (Bio-Rad) to determine purity and size in kDa. Protein concentration and protein vs. nucleic acid content (A280/A260) was measured spectrophotometrically using a DS-11 spectrophotometer (DeNovix). For gp15:gp16:DNA complex, an assembled complex of gp15:gp16 was incubated with ~1100bp linear dsDNA for 2h at 4 °C.

DNA:Protein Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay

24-bp complimentary 5’-Cy3 labeled oligonucleotides (5'-[Cy3]GCACTGCAGTAACTTGTCAGTCAT-3') were annealed to form dsDNA. Gp16-N or gp16-C at 0, 2.5, 5, 10 μM were incubated with 0.025 μM 5’-Cy3-dsDNA for one hour in a 10 μL reaction volume, containing 20 mM Tris-HCl pH 8.0, 50 mM sodium citrate, and 10 mM MgCl2. Samples were probed in NativePAGE™ 4-16% Bis-Tris protein gels (Invitrogen) in buffer from NativePAGE™ Running Buffer Kit (Invitrogen) at 150V for 100 min at 4 °C. Bands corresponding to the gp16-N/-C_Cy3-dsDNA complexes were analyzed using a ChemiDoc MP (Bio-Rad) with 577-613 nm filter. Further, the gel was stained with Coomassie blue to visualize protein.

Protein:Protein Electrophoretic Mobility Shift Assay (EMSA)

Gp15 (5.8 μM) was incubated with 5.8 μM, 11.6 μM, 23.2 μM, 34.8 μM of gp16-N for 1 hr at RT in molar ratios of 1:1, 1:2, 1:4, 1:6. 15 μL of samples were mixed with 3 μL of 4X Native PAGE™ Sample Buffer (Invitrogen) and ran on a NativePAGE™ 4-16% Bis-Tris protein gels (Invitrogen) in NativePAGE™ Running Buffer (Invitrogen) at 100V, for 100 min at 4 °C. The gel was stained with Coomassie blue to visualize protein.

Circular Dichroism and Thermal Stability

Circular dichroism (CD) spectra were recorded using a J-810 spectropolarimeter equipped with a temperature control system (Jasco). Samples were measured in a rectangular quartz cuvette with a path-length of 1 mm at a final protein concentration of 10 μM in 10 mM potassium phosphate buffer pH 7.4 and 25 mM NaCl at 20 °C. After the signal was averaged over five scans, the buffer signal was subtracted. Temperature-induced unfolding was monitored by recording variations in ellipticity at 222 nm as a function of temperature in 1.0 °C/min increments from 20 to 90 °C, as previously described (Florio et al., 2019; Lokareddy et al., 2017). Reversibility of unfolding was checked by cooling samples to 20 °C, followed by a second scan. The apparent melting temperature (appTm) observed for gp16-N and gp16-C was 46 °C and 44 °C, respectively, while for gp15, the appTm was 48 °C.

Lipid Bilayer Measurements

Lipid bilayer experiments were performed in a custom-made lipid bilayer apparatus as previously described (Heinz and Niederweis, 2000). A Teflon cuvette with 10 ml volume is separated into to compartments (cis- and trans-) by a wall with an aperture of approximately 1 mm in diameter. Ag/AgCl electrodes were bathed in a 1 M KCl, 10 mM HEPES pH 7.4 electrolyte solution. The cuvette was primed on both side of the aperture with 2% diphytanoylphosphatidylcholine (DPhPC) (Avanti Polar Lipids) in chloroform. Lipid membranes were painted across the aperture from a solution of 1% of DPhPC in n-decane. The samples were added to both sides of the cuvette. Baseline and detergent-containing buffers were examined to exclude contamination and detergent interference. Single-channel conductances for more than 100 pores for a protein sample were recorded. The current traces were recorded at −10 mV potential using a Keithley 428 current amplifier with a filter rise time of 30 ms and digitized by a computer equipped with Keithley Metrabyte STA 1800 U interface. The data were recorded with Test Point 4.0 software (Keithley) and analyzed using IGOR Pro 5.03 (WaveMetrics) using a macro provided by Dr. Harald Engelhardt, and visualized in SigmaPlot 11.0 (Systat Software).

Negative Stain TEM Preparation, Data Acquisition, and Data Processing

2-4 μL of purified gp15:gp16, gp16-C, gp15:gp16:DNA (~1,100 bps dsDNA) or gp16-C:2N2:PG nanodiscs at 0.01-0.05 mg/ml were adsorbed for 1 minute to carbon-coated 400-mesh copper grids (EMS) glow-discharged for 2 min at 25 mA using an easiGlow (PELCO). The grids were quickly washed with three 25 μl MilliQ water droplets, followed by staining with 25 μl 2% uranyl acetate for 10 seconds and again for 1 minute. Grids were blotted with filter paper and allowed to air dry before the screening. Images were collected on a FEI Tecnai T12 electron microscope equipped with a 4k x 4k OneView camera. The microscope was operated at 100 kV, at 67,000x or 110,000x magnification with a pixel size of 1.66 Å and 1.01 Å, respectively, and a defocus range of −0.5 to −1.5 μm. Particle picking, steps of classification, ab initio model generation, and 3D refinement were performed using RELION-3.1 (Scheres, 2012; Zivanov et al., 2018).

Cryo-EM Single-Particle Vitrification and Data Collection

2.5 μl of purified gp15:gp16-N at 2 mg/ml or gp16-C:2N2:PG at 1 mg/mL were adsorbed for 5-10 sec to 300-mesh Quantifoil R 1.2/1.3 holey carbon grids (EMS) glow discharged for 30 sec at 25 mA using an easiGlow (PELCO). The samples were blotted and frozen in liquid ethane using a Vitrobot Mark IV (Thermo Scientific). 7,818 movies for gp15:gp16-N samples were collected on a Titan Krios microscope (Thermo Scientific) at NIH-NCI-NCEF, operated at 300 kV, and equipped with a K3 direct electron detector camera (Gatan). Latitude S (Gatan) was used for data collection in super-resolution mode with an image pixel size of 0.54 Å and a nominal magnification of 81,000x. 3,306 movies for gp16-C:2N2:PG samples were collected on a Glacios (Thermo Scientific) equipped with a Falcon 4 direct electron detector (Thermo Scientific). EPU (Thermo Scientific) was used for data collection with an image pixel size of 0.74 Å and a nominal magnification of 190,000x. Further collection parameters are shown in Table 1.

Cryo-EM Single-Particle Data Processing

All movies were motion-corrected with MotionCor2 (Zheng et al., 2017), and CTF estimation was carried out using GCTF (Zhang, 2016). Data were processed with RELION-3.1 (Scheres, 2012; Zivanov et al., 2018), and more details of the data processing workflow for gp15:gp16-N data are shown in Figure S3B. For the gp15:gp16-N and gp16-C:2N2:PG datasets, ~2,000 particles were manually selected and subjected to 2D classification. Resulting class averages served as templates for the auto-picking. For the gp15:gp16-N dataset, ~4.7M particles were autopicked. After two rounds of 2D classification, ~2.1M particles were selected to generate ab initio 3D initial model, which was used as a 3D reference in the first round of 3D classification, sorting into 10 classes. 414k selected particles were subjected to a second round of 3D classification. The resulting 208k particles were aligned to a C6 point symmetry axis, CTF refined, and polished. After a final round of 3D refinement and post-processing, our initial asymmetric C1 reconstruction produced a 2.9 Å resolution map of excellent quality, which allowed building most of the gp15 and gp16 tape region (see below). In contrast, the electron density for residues 1-85 of the gp16 wings was noisy and poorly continuous (Figure S4A). To improve the electron density in the gp16-N wings, we rotated each particle around the symmetry axis six times to put all six wings in the same position for local classification using relion_particle_symmetry_expand. Next, all density was removed except one gp16-N wing to provide a modified particle set with the density for only one wing. A local mask was applied for the one wing, and 3D classification without any alignment was performed to classify particles solely on differences within one wing. A selected subset of particles from the 3D classification underwent a final 3D refinement with local searches only (modified with C1 symmetry options and additional argument "--sigma_ang 3") using a mask that contained this wing and the central tunnel of the gp15:gp16-N complex, and a final round of post-processing that resulted in a 2.7 Å map with markedly improved density for gp16-N. For the gp16-C:2N2:PG dataset, ~638k particles were auto-picked. After four rounds of 2D classification, ~105k particles were selected to generate ab initio 3D initial model, which was used as a 3D reference in the first round of 3D classification, sorting into 10 classes. ~49k particles were selected in one class and subjected to three rounds of 2D classification resulting in 20,345 particles used for a new ab initio 3D model limited to 15 Å. This second initial 3D model was used as a 3D reference for auto-picking resulting in ~303k particles that were subjected to five rounds of 2D classification and two rounds of 3D classification. The selected 11,944 particles were joined with the previous 20,345 particles, and duplicates were removed. From this pool, 9,018 particles were selected with a max-resolution cut-off of 9 Å by CTF estimation. Masked 3D refinement and post-processing resulted in 13.1 Å and 8.5 Å maps, respectively. Additionally, from the gp16-C:2N2:PG dataset, ~23,796 particles representing empty 2N2:PG nanodiscs were selected after four rounds of 2D classification and used for generation of an ab initio initial 3D model. The initial 3D model was used as a reference for 3D classification in which one of six classes was selected containing a final 11,030 particles. Masked 3D refinement and post-processing resulted in 24 Å and 17.8 Å maps, respectively.

De novo Model Building, Refinement, and Analysis

The cryo-EM map of T7 PT was built de novo using Coot (Emsley and Cowtan, 2004) and Chimera (Pettersen et al., 2004). The experimental density was of excellent quality, allowing us for unambiguous interpretation of residues 57-706 of gp15 and 1-228 of gp16-N. The atomic model was subjected to several rounds of real-space and B-factor refinement in Phenix (Afonine et al., 2018) and validation using MolProbity (Davis et al., 2007) (Table 1). 219 water molecules were built in the cryo-EM density using phenix.douse, which is part of Phenix version 1.18.2 31. All Ribbon models were generated using ChimeraX (Goddard et al., 2018) and PyMol (DeLano, 2002). Non-linear Poisson-Boltzmann electrostatic calculations were performed using APBS-PDB2PQR tools (Baker et al., 2001). Structural neighbors were identified using the DALI server (Holm and Rosenstrom, 2010). Binding interfaces were analyzed using PDBePISA (Krissinel and Henrick, 2007) and PDBsum (Laskowski, 2009). The program MOLEonline 2.0 (Pravda et al., 2018) was used to calculate the tunnel profiles shown in Figure 2D. Transmembrane helices in gp16 were predicted using TMbase (Hofmann and Stoffel, 1993). The sequence and secondary structure alignment were prepared using PDBsum (Laskowski, 2009).

Phylogenetic and Conservation Analysis

PSI-BLAST (Altschul and Koonin, 1998) was performed for T7 gp14, gp15, and gp16 sequences in UniprotKB and non-redundant protein sequences (nr) database. Nine gp14-like, gp15-like, and gp16-like sequences from Podoviridae that infect Gram-negative bacteria were further aligned against T7 with Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011). MemBrain (Yin et al., 2018) was used to predict gp14-like transmembrane domains (Data S1). The ten selected Podoviridae gp14-like, gp15-like, and gp16-like proteins were aligned using Clustal Omega (Goujon et al., 2010; Sievers et al., 2011) and sorted in phylogenetic trees according to iTOL v5.7 (Letunic and Bork, 2016) (Data S2). SIAS (http://imed.med.ucm.es/Tools/sias.html) was used to calculate sequence identities and similarities.

3D-Structure Prediction and Alignment

Gp16-C VLD domain structure was predicted by I-TASSER (Roy et al., 2010). Secondary structures of gp15 and gp16-N residues 1-228 built de novo in the cryo-EM reconstruction were displayed using PDBsum (Laskowski, 2009). Gp16-C VLD and human vinculin as well as gp15 and gp16-C res. 362-1318 were aligned with Clustal Omega (Sievers et al., 2011).

Quantification and Statistical Analysis

For calculations of Fourier shell correlations (FSC), the FSC cut-off criterion of 0.143 (Rosenthal and Henderson, 2003) was used. No statistical methods were used to predetermine sample size. The experiments were not randomized. The investigators were not blinded to allocation during experiments and outcome assessment.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Structure of the periplasmic channel of bacteriophage T7 DNA-ejectosome

gp14 has channel-forming activity

gp15 forms a hexameric DNA tunnel spanning the bacterial periplasm

Identification of three activities in the large ejection protein gp16

Acknowledgments

We thank the staff at the National Cryo-EM Facility at NCI-Frederick National Laboratory for assistance in data collection. This work was supported by NIH grants R01 GM100888 to G.C. and R21 HG010543 to M.N. Research in this publication includes work carried out at the Sidney Kimmel Cancer Center X-ray Crystallography and Molecular Interaction Facility at Thomas Jefferson University, which is supported in part by National Cancer Institute Cancer Center Support Grant P30 CA56036. This research was, in part, supported by the National Cancer Institute's National Cryo-EM Facility at the Frederick National Laboratory for Cancer Research under contract HSSN261200800001E. Atomic coordinates for the T7 DNA-Ejectosome components gp15:gp16-N have been deposited in the Protein Data Bank with accession code 7K5C, and the cryo-EM density map has been deposited in the Electron Microscopy Data Bank with accession code EMD-22680.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Inclusion and Diversity

One or more of the authors of this paper self-identifies as a member of the LGBTQ+ community. The author list of this paper includes contributors from the location where the research was conducted who participated in the data collection, design, analysis, and/or interpretation of the work.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

REFERENCES

- Afonine PV, Poon BK, Read RJ, Sobolev OV, Terwilliger TC, Urzhumtsev A, and Adams PD (2018). Real-space refinement in PHENIX for cryo-EM and crystallography. Acta Crystallogr D Struct Biol 74, 531–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agirrezabala X, Martin-Benito J, Caston JR, Miranda R, Valpuesta JM, and Carrascosa JL (2005). Maturation of phage T7 involves structural modification of both shell and inner core components. EMBO J 24, 3820–3829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Altschul SF, and Koonin EV (1998). Iterated profile searches with PSI-BLAST--a tool for discovery in protein databases. Trends Biochem Sci 23, 444–447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baker NA, Sept D, Joseph S, Holst MJ, and McCammon JA (2001). Electrostatics of nanosystems: application to microtubules and the ribosome. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 98, 10037–10041. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bhardwaj A, Molineux IJ, Casjens SR, and Cingolani G (2011). Atomic structure of bacteriophage Sf6 tail needle knob. J Biol Chem 286, 30867–30877. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bohm K, Porwollik S, Chu W, Dover JA, Gilcrease EB, Casjens SR, McClelland M, and Parent KN (2018). Genes affecting progression of bacteriophage P22 infection in Salmonella identified by transposon and single gene deletion screens. Mol Microbiol 108, 288–305. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerritelli ME, Trus BL, Smith CS, Cheng N, Conway JF, and Steven AC (2003). A second symmetry mismatch at the portal vertex of bacteriophage T7: 8-fold symmetry in the procapsid core. J Mol Biol 327, 1–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CY, Kemp P, and Molineux IJ (2010a). Gp15 and gp16 cooperate in translocating bacteriophage T7 DNA into the infected cell. Virology 398, 176–186. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang JT, Schmid MF, Haase-Pettingell C, Weigele PR, King JA, and Chiu W (2010b). Visualizing the structural changes of bacteriophage Epsilon15 and its Salmonella host during infection. J Mol Biol 402, 731–740. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen DH, Baker ML, Hryc CF, DiMaio F, Jakana J, Wu W, Dougherty M, Haase-Pettingell C, Schmid MF, Jiang W, et al. (2011). Structural basis for scaffolding-mediated assembly and maturation of a dsDNA virus. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 108, 1355–1360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cingolani G, Lashuel HA, Gerace L, and Muller CW (2000). Nuclear import factors importin alpha and importin beta undergo mutually induced conformational changes upon association. FEBS Lett 484, 291–298. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cuervo A, Fabrega-Ferrer M, Machon C, Conesa JJ, Fernandez FJ, Perez-Luque R, Perez-Ruiz M, Pous J, Vega MC, Carrascosa JL, et al. (2019). Structures of T7 bacteriophage portal and tail suggest a viral DNA retention and ejection mechanism. Nat Commun 10, 3746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dai W, Fu C, Raytcheva D, Flanagan J, Khant HA, Liu X, Rochat RH, Haase-Pettingell C, Piret J, Ludtke SJ, et al. (2013). Visualizing virus assembly intermediates inside marine cyanobacteria. Nature 502, 707–710. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dal Peraro M, and van der Goot FG (2016). Pore-forming toxins: ancient, but never really out of fashion. Nat Rev Microbiol 14, 77–92. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davis IW, Leaver-Fay A, Chen VB, Block JN, Kapral GJ, Wang X, Murray LW, Arendall WB 3rd, Snoeyink J, Richardson JS, et al. (2007). MolProbity: all-atom contacts and structure validation for proteins and nucleic acids. Nucleic Acids Res 35, W375–383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- DeLano WL (2002). The PyMOL Molecular Graphics System, Version 1.8 Schrödinger, LLC. [Google Scholar]

- Emsley P, and Cowtan K (2004). Coot: model-building tools for molecular graphics. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 60, 2126–2132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]