Abstract

Coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19) has endured constituting formidable economic, social, educational, and phycological challenges for the societies. Moreover, during pandemic outbreaks, the hospitals are overwhelmed with patients requiring more intensive care units and intubation equipment. Therein, to cope with these urgent healthcare demands, the state authorities seek ways to develop policies based on the estimated future casualties. These policies are mainly non-pharmacological policies including the restrictions, curfews, closures, and lockdowns. In this paper, we construct three model structures of the SIIID-N (suspicious S, infected I, intensive care I, intubated I, and dead D together with the non-pharmacological policies N) holding two key targets. The first one is to predict the future COVID-19 casualties including the intensive care and intubated ones, which directly determine the need for urgent healthcare facilities, and the second one is to analyse the linear and non-linear dynamics of the COVID-19 pandemic under the non-pharmacological policies. In this respect, we have modified the non-pharmacological policies and incorporated them within the models whose parameters are learned from the available data. The trained models with the data released by the Turkish Health Ministry confirmed that the linear SIIID-N model yields more accurate results under the imposed non-pharmacological policies. It is important to note that the non-pharmacological policies have a damping effect on the pandemic casualties and this can dominate the non-linear dynamics. Herein, a model without pharmacological or non-pharmacological policies might have more dominant non-linear dynamics. In addition, the paper considers two machine learning approaches to optimize the unknown parameters of the constructed models. The results show that the recursive neural network has superior performance for learning nonlinear dynamics. However, the batch least squares outperforms in the presence of linear dynamics and stochastic data. The estimated future pandemic casualties with the linear SIIID-N model confirm that the suspicious, infected, and dead casualties converge to zero from 200000, 1400, 200 casualties, respectively. The convergences occur in 120 days under the current conditions.

Keywords: COVID-19, Casualties, Pandemic, Prediction, Model, Non-linear dynamics, Linear dynamics

1. Introduction

Even though pharmacological developments like vaccines have expected to yield some successful results, the COVID-19 has continued to be a dreadful threat for societies due to challenges in producing a sufficient number of vaccines [1]. The COVID-19 emerged in December 2019 in Wuhan city of China has spread to over 113 countries with 91,605,941 infected and 1,962,345 dead as of 13 January 2021 [2]. The second peak in the COVID-19 casualties, which is larger than the first peak, has caused considerable challenges for the healthcare providers since the hospitals have been overwhelmed with suspicious, infected, intensive care, intubated, and dead people [3]. To halt the spread of the virus, non-pharmacological policies such as closures, restrictions, and curfews have been re-imposed [4]. International organizations such as the World Health Organization (WHO) and also the state authorities require accurate models to understand the character of the pandemic diseases and also to estimate the future casualties [5]. In this paper, we develop a parametric model called as SIIID-N (suspicious S, infected I, intensive care I, intubated I, and death D together with the non-pharmacological policies N) to predict the future pandemic casualties in the presence of the non-pharmacological policies.

The recent history has witnessed severe acute respiratory syndrome (SARS), Middle East respiratory syndrome (MERS), and the COVID-19 outbreaks and more than 2000, 8000, and 91,000,000 people were infected, respectively [6]. It is reported that the COVID-19 outbreak has brought about a heavier burden than the recent 2009 influenza pandemic and seasonal influenza in terms of the hospital requirements and mortality rates [7]. Although the COVID-19 is not a new member of the pandemic diseases family as it has emerged from the SARS coronavirus, it has unseen characters including the rapid spread in the human body, high infectious speed, extreme resilience against the environmental conditions, efficient adaptation to the human body, and considerably virulent genetic variant [8]. Therefore, developing models for the COVID-19 outbreak is challenging due to these complex and time-varying dynamics [9]. Modelling of the pandemic diseases can be categorized as parametric and non-parametric where the parametric approaches are mainly based on the system identification and the non-parametric approaches are based on the statistical approaches.

With respect to the non-parametric approaches, Zhu and Chen introduced a statistical disease transmission model to predict the early-stage transmissibility of the COVID-19 outbreak in China which yielded 4.2 for the infectious period with a 95% confidence interval [10]. Gupta et al. analysed the relationship between the COVID-19 stemmed mortality and air pollution with the variance and regression models which revealed a positive correlation for the nine Asian cities [11]. Similarly, Redon and Aroca reviewed the role of the climate change and the COVID-19 spread with the generalized linear models which showed that the hot weather impacts on the transmission of the virus are insignificant [12]. Rozenfeld et al. performed a multivariable statistical approach to analyse the infection of the COVID-19 based on the age, obesity, gender, race, ethnicity, and income. The results highlighted that the communities having poor housing, insecure transportation, and chronic disease make people more vulnerable to the COVID-19 [13]. The key disadvantage associated with the statistical approaches is that they do not account for the possible presence of the temporal trends in the data; however, they all have a transient period before exerting their full impacts.

Neural network (NN) is a non-parametric machine learning (ML) approach mostly considered for prediction. Wieczorek et al. trained an NN with available spread rates and used the resulted model to predict the COVID-19 spread for various regions [14]. Melin et al. constructed an NN to perform predictions under various conditions and utilized a fuzzy logic algorithm to make a decision depending on the predictions [15]. Ahmad and Asad provided an NN-based prediction for the infected, recovered, and death casualties [16]. NN approaches require a suitable training model selected based on the characteristic of the historical data, which necessaire intuitive insights about the data and re-training since the pandemic outbreaks usually have time-varying dynamics.

With regard to the parametric approaches, Chen et al. used the susceptible–infected– recovered (SIR) model with available transmission and recovery rates to predict the casualties in China [17]. Calafiore et al. considered the susceptible–infected–recovered–dead (SIRD) model with the time-varying parameters to estimate the casualties in Italy [18]. Mahajan et al. implemented the susceptible–exposed–symptomatic–purely asymptomatic- hospitalized–recovered–deceased (SIPHERD) model to predict the casualties in India [5]. All these models are first-order non-linear and do not take into account the non-pharmacological policies. Recently, we developed the suspicious–infected–death (SpID) model having second-order linear coupled dynamics learned from the available data [19]. We showed that the SpID model can efficiently represent the second-order dynamics such as the distinct peak and performed eigenvalue-based character analysis. In addition, we proposed the SpID-N model with the parametrized non-pharmacological policies N and extensively analyse the role of each non-pharmacological policy on the reported casualties [20]. This research proved that the second-order dynamics of the COVID-19 occur due to non-pharmacological policies and they are not intrinsic.

Recent researches have addressed the external impacts such as the weather on the COVID-19. Coskun et al. investigated the role of the population density and the climatic properties including the temperature, humidity, wind, and the number of sunny days on the COVID-19 spread [21]. Similarly, Sahin examined the interactions between the COVID-19 and temperature, dew point, humidity, and wind [22]. Ozer analysed the distance education efforts during the COVID-19 outbreak [23]. Morgul et al. examined the relationship between the COVID-19 outbreak and psychological fatigue as a mental health issue [24]. Satici et al. assessed the COVID-19 stemmed fear and psychological distress and life satisfaction [25].

Based on these expressed gaps in the corresponding literature, we can summarize the contributions of this paper as:

-

(1)

We construct three SIIID-N model structures; namely, linear SIIID-N model, non-linear SIIID-N model, and strongly non-linear SIIID-N model to reveal the linear and non-linear characters of the COVID-19 casualties under the comprehensive non-pharmacological policies. All the parametric models expressed above have non-linear structures, but they do not consider the non-pharmacological policies. It is a fact that non-pharmacological policies are the essential tools to control pandemic casualties. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first paper examining the linear and non-linear properties of a pandemic disease under such extensive non-pharmacological policies.

-

(2)

We modify the non-pharmacological policies since their characters have changed with the occurrence of the second peak in the COVID-19 casualties. Re-opening of the schools partial-by-partial and imposed self-curfews, for instance, are modelled and incorporated into the SIIID-N models.

-

(3)

We enrich the SpID-N model with the intensive care I and intubated I to estimate the healthcare requirements.

All the model parameters are assigned as unknown and learned from the available data by using the batch type least-squares (BLS) approach. In this respect, the SIIID-N model is adaptive since it updates its parameters as the new data are available. In addition, further linear and non-linear model structures can be constructed, but as this paper aims to analyse the character of the pandemic dynamics, we have considered only three SIIID-N model structures.

In the rest of the paper, Section 2 introduces the proposed model structures, Section 3 provides the modified non- pharmacological policies, Section 4 derives the BLS to learn the unknown parameters, Section 5 analysis the models and predicts the future pandemic casualties and Section 6 summarizes the key contributions of the paper.

2. Linear and non-linear parametric model structures

In this section, we introduce three parametric model structures; namely, a linear SIIID-N model, a nonlinear SIIID-N model, and a strongly non-linear SIIID-N model which are all extensively analysed in terms of representing the characteristics of the pandemic diseases, specifically the COVID-19. It is important to note that various alternative structures for the linear and non-linear SIIID-N model can be formed. However, since this paper focuses on revealing the existence of linear or non-linear dynamics, we have constructed and analysed only three model structures.

2.1. Linear SD-N model

The linear SIIID-N model architecture is shown in Fig. 1

Fig. 1.

Linear SIIID-N model architecture.

As can be seen from Fig. 1, the linear SIIID-N model consists of five sub-models. The suspicious sub-model represents the people tested daily. Some of the suspicious people become infected with an unknown parameter , and a number of the infected people can spread the virus with an unknown parameter rate , which excites the number of the suspicious casualties. The infected individuals can move to the intensive care unit with the parameter , and a number of them leave the intensive care unit , but remain infected with the unknown parameter . Some of the intensive care patients become intubated with the unknown parameter . The intubated patients can be dead with the parameter , and the changes in the death is reflected on the intubated casualties with the unknown parameter. Since the SIIID-N model does not cover the recovered and asymmetric casualties, the model represent them as the unmodelled dynamics with the , , , , coupling parameters. To explicitly represent such epidemiological properties, the SIIID-N model should be enhanced. The non-pharmacological polices is the external input and it manipulates the sub-models with the , , , , and unknown parameters. These unknown parameters are learned in Section 0.

The linear SIIID-N model in Fig. 1 can be represented by considering only the arrows leaving out each sub-model as

| (1) |

| (2) |

| (3) |

| (4) |

| (5) |

Table 1 introduces the components of the linear SIIID-N.

Table 1.

Components of the linear SIIID-N.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| , , , , | Unknown internal parameters of the , , , ,and , respectively. |

| , , , , , , , | Unknown coupling parameters of the , , , , and . |

| , , , , | Unknown parameters of the non-pharmacological policies contributing to the , , , , and sub-models, respectively. |

All the sub-models of the linear SIIID-N model have corresponding internal dynamics and also the coupling dynamics associated with the neighbouring sub-models. These dynamics are represented with the parameters learned from the data (reported pandemic casualties); therefore, the parameters of the pandemic diseases such as the infectious rate and recovery rate are learned implicitly. The next sub-section introduces the non-linear SIIID-N model.

2.2. Non-linear SD-N model

Fig. 2 illustrates the constructed nonlinear SIIID-N model.

Fig. 2.

Non-linear SIIID-N model architecture.

As can be seen from Fig. 1, Fig. 2, the only difference between the linear and nonlinear SIIID-N models is the non-linear coupling of the suspicious and infected sub-models through the and unknown parameters. The suspicious casualties vary based on the number of the people tested daily, the daily testing capacity of the healthcare centersand whether the tests are made in the existence of strong symptoms. If the capacities of the healthcare centres are constant or less than the daily requirements, then it is expected to have a non-linear relationship between the suspicious and the infected casualties. The non-linearity occurs because the proportional input of the model does not yield a proportional output. However, if the healthcare centres are flexible to meet the daily test requirements and the tests are performed in the presence of certain symptoms, then it is anticipated to have a linear relationship between the suspicious and infected casualties. In this case, the proportional inputs of the model produce proportional outputs. Thus, the results presented in the analyses section can vary from country to country based on the healthcare infrastructure of the countries and policies for handling the outbreaks. However, since the proposed SIIID-N models learn the parameters from the available data, they are adaptive and can be used to estimate the corresponding pandemic casualties.

We can represent the non-linear SIIID-N model with five sub-models where the suspicious and infected sub-models are non-linearly coupled as

| (6) |

| (7) |

| (8) |

| (9) |

| (10) |

Table 2 introduces the components of the non-linear SIIID-N.

Table 2.

Components of the non-linear SpInItIbD-N.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| , | Unknown internal parameters non-linearly associated with the and . |

| , , | Unknown internal parameters of the , , and , respectively. |

| , , , , , | Unknown coupling parameters of the , , , , and . |

| , , , , | Unknown parameters of the non-pharmacological policies for the , , , , and sub-models, respectively. |

The next sub-section introduces the strongly non-linear SIIID-N model.

2.3. Strongly non-linear SD-N model

Fig. 3 shows the strongly non-linear SIIID-N model structure.

Fig. 3.

Strongly non-linear SIIID-N model architecture.

As can be seen from Fig. 3, all the internal dynamics of the sub-models are non-linearly coupled with the neighbouring sub-models. The existence of the strong non-linear dynamics depends on the healthcare infrastructure and also the non-pharmacological policies. The non-pharmacological policies are like the external forces manipulating the casualties to stabilize them at the desired equilibriums, desirably converge them to zero. Therefore, the non-pharmacological policies can dominate the internal and coupling dynamics or, if they are efficient enough, they can completely eliminate the intrinsic dynamics of the pandemic diseases.

Strongly non-linear SIIID-N model couples all the internal parameters as

| (11) |

| (12) |

| (13) |

| (14) |

| (15) |

Table 3 introduces the components of the strongly non-linear SIIID-N.

Table 3.

Components of the strongly non-linear SpInItIbD-N.

| Component | Description |

|---|---|

| , , , , | Unknown internal parameters non-linearly associated with the , , , , and , respectively. |

| , , | Unknown coupling parameters of the , , and , respectively. |

| , , , , | Unknown parameters of the non-pharmacological policies contributing to the , , , , and sub-models, respectively. |

The next section reviews the modified non-pharmacological policies which are the external inputs of the SIIID-N models.

3. The non-pharmacological policies N

In this section, we review the parametrized non-pharmacological policies imposed to battle against the pandemic diseases. These non-pharmacological policies are (A) Curfews on the people with chronic diseases, age over 65, and age under 20, (B) Curfews on the weekends and holidays, (C) Closure and re-opening of the schools and universities. Since the data for these non-pharmacological policies are not directly available, it is necessary to develop mathematical models which imitate the response of them.

3.1. Curfews on people with chronic diseases, age over 65, and age under 20

As people with chronic diseases and age over 65 are highly defenceless against the outbreaks, curfews are implemented on them primarily. Even though people age under 20 are resilient against the outbreaks, as they are super spreaders of the virus, they are put under curfews as well.

To model such curfews, consider these facts about the pandemics:

-

•

It is reported that symptoms of a pandemic diseases can appear in 14 days where the peak point is around day 7 as reported by the WHO [26]. Therefore, a non-pharmacological policy should have a transient ascent part that reaches the peak point around day 7 and a transient descent part that converges to zero at day 14 as shown in Fig. 4.

-

•

If the curfew continues for a period of time, then the response of the non-pharmacological policy has a steady-state behaviour just after the transient ascent part as can be seen in Fig. 4.

-

•

Since it is likely that the curfew can be violated by an uncertain number of people, the response of the curfew covers random non-parametric uncertainties as shown in Fig. 5.

Fig. 4.

Transient ascent, steady-state, and transient descent parts of the response without uncertainty.

Fig. 5.

The uncertain response of the curfew modelled for Turkey with the data presented in Table 4.

We can model the uncertain transient ascent and steady-state parts of the response as

| (16) |

where

-

•

is the response of the curfew (in closed form solution),

-

•

is the number of the people under the curfew,

-

•

is the number of the days and is the start day of the curfew,

-

•

is the discount factor of the response, where for and ,

-

•

is the random non-parametric uncertainty in the response,

-

•When the curfew is lifted, its effect disappears in 14 days (Fig. 4) and this constitutes the transient descent part of the model represented as

(17)

where

is the terminal day of the curfew.

Even though the curfews are abolished, a number of elderly people with chronic diseases impose self-curfews which can be expressed as

| (18) |

where

represents the number of the people under self-curfew.

The next sub-section reviews the parametric model of the curfew implemented on the weekends and holidays.

3.2. Curfews on the weekends and holidays

Since the duration of the curfews on the weekends and holidays are usually for two days, their response consists of the transient ascent and transient descent parts. Therefore, the response has impulse response properties whose transient ascent part is

| (19) |

where

-

•

is the response of the curfew on the weekends and holidays,

-

•

is the number of the people under the curfews on the weekends and holidays,

-

•

is the random uncertainty in the response,

The transient descent part of the response is

| (20) |

The overall response is

| (21) |

The next sub-section introduces the closure and re-opening of the schools and universities.

3.3. Closure and re-opening of the schools and universities

While closing the schools and universities can hinder the spread of the viruses, re-opening of them reverses the contribution. Modelling the closure part of the response is same as modelling the curfews on the people with chronic diseases and age over 65. However, re-opening is usually periodic (as in Turkey) since the students partially attend the schools on certain days of the week. This can be expressed as

| (22) |

where

-

•

is the response of the closure and re-opening of the schools and universities,

-

•

is the number of the students attending the schools partially,

-

•

is the day that the schools re-open,

-

•

is the random uncertainty of the response,

Fig. 6 shows the response of the model for Turkey where the schools were closed, partially re-opened, and re-closed.

Fig. 6.

The response of the model with closure, re-opening, and re-closure of the schools for Turkey.

The next section presents the parametrized SIIID-N models and the batch type least squares (BLS) estimator.

4. BLS based unknown parameters learning

In this section, initially, we parametrize the SIIID-N models in terms of the known bases and unknown parameters. Then, we use the BLS optimization approach to determine the unknown parameters.

4.1. Formulation of the estimated SD-N models

The estimated sub-models of the SIIID-N models can be represented as

| (23) |

| (24) |

| (25) |

| (26) |

| (27) |

where , , , , and are the estimated outputs for the suspicious, infected, intensive care, intubated and deaths sub-models respectively, ’s are the corresponding known bases covering the reported casualties. For instance, the bases of the nonlinear SIIID-N model by considering Eqs. (6) to (10) can be formed as

| (28) |

| (29) |

| (30) |

| (31) |

| (32) |

where is the dot product and is the sum of the all non-pharmacological policies. The corresponding unknown parameter vectors are

| (33) |

| (34) |

| (35) |

| (36) |

| (37) |

The real outputs are

| (38) |

| (39) |

| (40) |

| (41) |

| (42) |

4.2. The BLS formulation

Consider the error between the real outputs and estimated outputs expressed as

| (43) |

where and .

The squared error is

| (44) |

The slope of the squared error with respect to the unknown parameters is

| (45) |

Since the parameter learning process terminates with the zero slope, equating (45) zero yields the optimum unknown parameters formulated as

| (46) |

The unknown parameters can be determined with Eq. (46) by using the constructed bases and the outputs. The next section provides the comparative results of the three SIIID-N models.

5. Analysis of the proposed SIIID-N models

In this section, we analyse the proposed models by using the COVID-19 casualties reported by the Health Ministry of Turkey [2]. Turkey is chosen because the authors are able to reach the data required for the constructed models. Even though the casualties are reported daily by the Health Ministry, the data for the non-pharmacological policies are usually announced verbally, and understanding the written statements is not straightforward. To properly represent the character o the models, especially the non-pharmacological policies, the home country of the authors has been chosen. To optimize the unknown parameters of the constructed models, a batch least-squares (BLS) and a neural network (NN) approaches are considered. Initially, we introduce the background data and then presents the estimated casualties with developed models. We perform the mean and the standard deviation-based analysis of the models to validate the effectiveness.

5.1. Parameters of the models

Table 4 summarizes the parameters of the models.

Table 4.

Parameters of the models.

| 26.567.000 | People with chronic diseases | |

| 1.517.000 | People age over 65 without chronic diseases | |

| 25.573.000 | People age under 20 | |

| 29.497.000 | Remaining people under curfews | |

| 26.048.000 | Number of the school and university students | |

|

|

First COVID-19 casualty has been seen | |

| and |

|

Start and end dates of the curfews for the people with chronic diseases and their corresponding day numbers |

| and |

|

Start and end dates of the curfews for the people age over 65 and their corresponding day numbers |

| and |

|

Start and end dates of the curfews for the people age under 20 and their corresponding day numbers |

| and |

– cont. |

Closure and re-opening dates of the schools and universities closures and their corresponding day numbers |

| and |

|

Start and end dates of the curfews on the weekend and holidays |

5.2. Analysis of the linear SD-N model

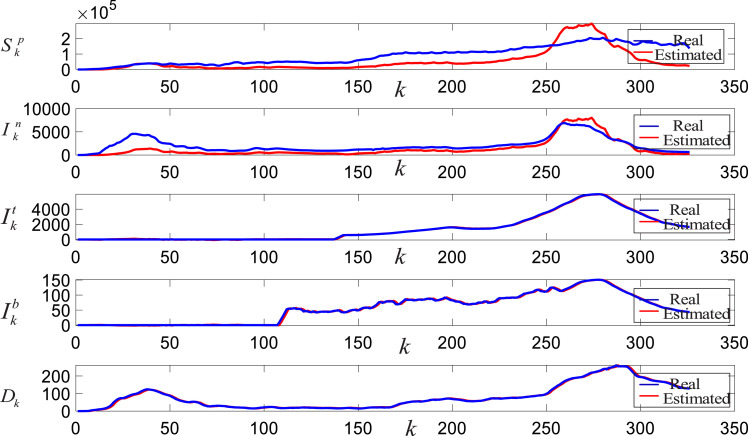

Fig. 7 presents the real and estimated outputs of the linear SIIID-N model with the BLS approach.

Fig. 7.

The real and estimated outputs of the linear SIIID-N Model with the BLS.

As can be seen from Fig. 7, all the sub-models of the linear SIIID-N model with the BLS are able to follow the real outputs including the peaks. Even though the initial intensive care and intubated data are not available, the linear SIIID-N model manages to learn the corresponding characters of the sub-models. It is also noticeable that the developed SIIID-N model closely chases the fluctuations in the real outputs. This indicates the existence of low standard deviations together with the mean errors in the estimates. Fig. 8 presents the linear SIIID-N model estimates with the NN approach.

Fig. 8.

The real and estimated outputs of the linear SIIID-N model with the NN.

NN is an iterative approach, whereas the BLS is a batch type approach. It is well known that the batch kind approaches provide accurate results for stochastic optimization problems. As can be seen from Fig. 8, that the suspicious , infected , and intubated casualties have larger fluctuations due to the stochastic nature of the casualties. Henceforth, even though the NN can capture the dynamics of these sub-models, estimates with the NN yield slightly more fluctuations than the BLS estimates in Fig. 7. The next sub-section provides the real and estimated results of the non-linear SIIID-N model with the BLS and NN approaches.

5.3. Analysis of the non-linear SD-N model

Fig. 9 shows the real and estimated outputs of the non-linear SIIID-N model with the BLS.

Fig. 9.

The real and estimated outputs of the non-linear SIIID-N model with the BLS.

The internal dynamics of the suspicious and infected sub-models of the non-linear SIIID-N model are non-linearly coupled as given in Eqs. (6) and (7) and the rest of the sub-models are linearly coupled with their neighbouring sub-models. As illustrated by Fig. 9, the non-linearly coupled suspicious and infected sub-models have the largest estimation errors. This implies that the internal dynamics of the suspicious and infected sub-models are not quite non-linearly coupled for the reported casualties of Turkey. However, since the casualties of each country and also regions of the countries might have different characteristics, for other cases, these sub-models may provide much more accurate results. In addition, recursive approaches such as the NN can manage to learn the non-linear dynamics with higher accuracy than a batch kind approach. Fig. 10 exhibits that the NN approach is able to learn the non-linear parameters with smaller estimation errors.

Fig. 10.

The real and estimated outputs of the non-linear SIIID-N model with the NN.

As can be seen from Fig. 10, the recursive estimates of the unknown parameters associated with the non-linear couplings yield a smaller estimation error than the batch type learning shown in Fig. 9. It is known that the NN is a non-parametric modelling approach which can learn any linear or non-linear functions from the input–output data. This result shows that the NN has superior performance for optimizing the non-linear parameters. The next sub-section provides the real and estimated outputs of the strongly non-linear SIIID-N model with the BLS and NN approaches.

5.4. Analysis of the strongly non-linear SD-N model

Fig. 11 shows the real and estimated outputs of the strongly non-linear SIIID-N model with the BLS.

Fig. 11.

The real and estimated outputs of the strongly non-linear SIIID-N model the BLS.

All the sub-models of the strongly non-linear SIIID-N model have coupled internal dynamics as illustrated by Equations from (11) to (15) where all yield the largest estimation errors compared to the non-linear SIIID-N and linear SIIID-N models. It is noticeable that especially the death sub-model is unable to produce proper estimations. This indicates that it is non-linearly correlated with the intubated sub-model. The positive correlation is possibly due to the fact that the COVID-19 stemmed deaths can occur among the intubated , intensive care , and suspicious as well. Fig. 12 illustrates the estimates of the strongly non-linear SIIID-N model with the NN approach.

Fig. 12.

The real and estimated outputs of the strongly non-linear SpInItIbD-N Model with the NN.

As can be seen from Fig. 12, the NN again produces smaller estimation errors but generates larger variations when the data have random characters. This is expected since the recursive approaches consider the instant data; henceforth, the latest variations can be learned while the ones in the past are forgotten. However, the batch type approaches can normalize the data and can learn the average character of them. The next sub-section compares the proposed models in terms of the corresponding mean errors and standard deviations.

5.5. Comparison analysis of the proposed models

Fig. 13 shows the mean errors and the standard deviations of the estimated outputs by the proposed models.

Fig. 13.

Mean and standard deviations of the estimation errors where the bars represent the mean errors and the lines on the bars represent the standard deviations.

It is clear from Fig. 13, all the sub-models of the linear SIIID-N model yield the smallest mean errors and also the smallest standard deviations for the reported casualties of Turkey. Both the mean errors and the standard deviations increase with respect to the non-linear coupling. We can deduct from these results that the linear SIIID-N model provides more accurate results for Turkey. However, the character of the non-linear dynamics depends on the healthcare infrastructure of the countries and the properties of the imposed pharmacological or non-pharmacological policies. It is also obvious from Fig. 13 that the NN approach outperforms the BLS approach in the presence of non-linear dynamics. Nevertheless, in the case of linear dynamics, the BLS generally performs better. The NN generates more accurate results only when the casualties have less variation as in the intensive care and dead casualties.

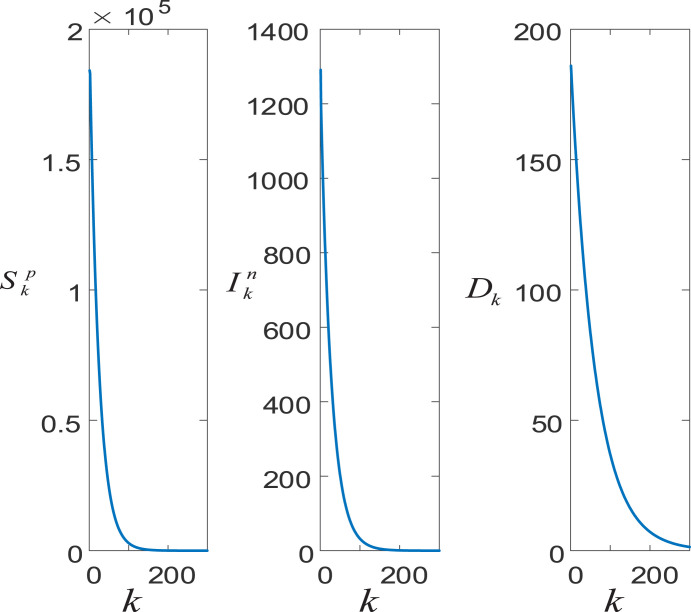

5.6. Predicted future COVID-19 casualties with linear SD-N model

Since the linear SIIID-N model results in the least estimation errors, we provide the estimated future casualties with the linear SIIID-N model. Fig. 14 provides predicted future casualties for Turkey with the linear SIIID-N model trained with data covering the period where the non-pharmacological policies have been imposed.

Fig. 14.

Predicted future casualties for Turkey with the linear SIIID-N model.

We used the reported COVID-19 casualties corresponding to the period where the non-pharmacological policies such as the closure of the schools, curfews on the weekends, and restrictions on the people with chronic diseases to determine the unknown parameters of the linear SIIID-N model. Otherwise, when we use the whole data, the linear SIIID-N model is unstable and all the sub-models produce unbounded outputs. This indicates the importance of non-pharmacological policies to confine the spread of the virus. As can be seen from, Fig. 14 the suspicious and infected converge to zero around 120 days under the current conditions.

6. Conclusion

This paper constructed three SIIID-N model structures consisting of the linear and non-linear representations of the pandemic dynamic. The research has confirmed that the linear SIIID-N model yields more than 10 times smaller mean errors and standard deviations than the nonlinear SIIID-N model. The outperformance of the linear SIIID-N model can stem from the inclusion of the extensive non-parametric policies, which can dominate the non-linear dynamics. Moreover, the linear SIIID-N model predicts that the casualties will reach their minimum of around 120 days under the current conditions. As future work, the parametric SIIID-N model should be enriched with the susceptible and recovered casualties and the model structure should be determined based on the more accurate epidemiological facts. In addition, the model should be equipped with the priority and age-specific vaccination policy and other pharmacological advancements. Finally, the developed models should be used with artificial intelligence algorithms to make optimum policies on the control of pandemic diseases.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- 1.Gostin L.O., Karim S.A., Mason Meier B. Facilitating access to a COVID-19 vaccine through global health law. J Law Med Eth. 2020;48(3):622–626. doi: 10.1177/1073110520958892. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.2020. Digital transformation office of the Turkish presidency. accessed 3 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 3.COVID I., Murray C.J. 2020. Forecasting COVID-19 impact on hospital bed-days, ICU-days, ventilator-days and deaths by US state in the next 4 months. MedRxiv. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhattacharya S., Singh A., Hossain M.M. Health system strengthening through massive open online courses (MOOCs) during the COVID-19 pandemic: An analysis from the available evidence. J Educ Health Prom. 2020:9. doi: 10.4103/jehp.jehp_377_20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Mahajan A., Solanki R. 2020. An epidemic model SIPHERD and its application for prediction of the COVID-19 infection for India and USA. arXiv preprint arXiv:2005.00921. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peeri N.C., Shrestha N., Rahman M.S., Zaki R., Tan Z., Bibi S., et al. The SARS, MERS and novel coronavirus (COVID-19) epidemics, the newest and biggest global health threats: what lessons have we learned? Int J Epidemiol. 2020;49(3):717–726. doi: 10.1093/ije/dyaa033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yang J., Chen X., Deng X., Chen Z., Gong H., Yan H., et al. Disease burden and clinical severity of the first pandemic wave of COVID-19 in wuhan, China. Nature Commun. 2020;11(1):1–10. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-19238-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Das P., Choudhuri T. Decoding the global outbreak of COVID-19: the nature is behind the scene. VirusDisease. 2020:1–7. doi: 10.1007/s13337-020-00605-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Abdel-Basst M., Mohamed R., Elhoseny M. <? covid19?> a model for the effective COVID-19 identification in uncertainty environment using primary symptoms and CT scans. Health Inform J. 2020 doi: 10.1177/1460458220952918. 1460458220952918. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Zhu Y., Chen Y.Q. On a statistical transmission model in analysis of the early phase of COVID-19 outbreak. Stat Biosci. 2021;13(1):1–17. doi: 10.1007/s12561-020-09277-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gupta A., Bherwani H., Gautam S., Anjum S., Musugu K., Kumar N., et al. Air pollution aggravating COVID-19 lethality? Exploration in Asian cities using statistical models. Environ Dev Sustain. 2021;23(4):6408–6417. doi: 10.1007/s10668-020-00878-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Briz-Redón Á., Serrano-Aroca Á. The effect of climate on the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic: A review of findings, and statistical and modelling techniques. Progress Phys Geogr: Earth Environ. 2020;44(5):591–604. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rozenfeld Y., Beam J., Maier H., Haggerson W., Boudreau K., Carlson J., et al. A model of disparities: risk factors associated with COVID-19 infection. Int J Equit Health. 2020;19(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12939-020-01242-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wieczorek M., Siłka J., Woźniak M. Neural network powered COVID-19 spread forecasting model. Chaos Solitons Fractals. 2020;140 doi: 10.1016/j.chaos.2020.110203. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Melin P., Monica J.C., Sanchez D., Castillo O. Multiple ensemble neural network models with fuzzy response aggregation for predicting COVID-19 time series: the case of Mexico. Healthcare. 2020;8(2):181. doi: 10.3390/healthcare8020181. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmad I., Asad S.M. Predictions of coronavirus COVID-19 distinct cases in Pakistan through an artificial neural network. Epidemiol Infect. 2020:148. doi: 10.1017/S0950268820002174. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Chen Y.C., Lu P.E., Chang C.S., Liu T.H. A time-dependent SIR model for COVID-19 with undetectable infected persons. IEEE Trans Netw Sci Eng. 2020;7(4):3279–3294. doi: 10.1109/TNSE.2020.3024723. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Calafiore G.C., Novara C., Possieri C. A time-varying SIRD model for the COVID-19 contagion in Italy. Annu Rev Control. 2020;50:361. doi: 10.1016/j.arcontrol.2020.10.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tutsoy O., Çolak Ş., Polat A., Balikci K. A novel parametric model for the prediction and analysis of the COVID-19 casualties. IEEE Access. 2020;8 doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3033146. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Tutsoy O., Polat A., Colak S., Balikci K. Development of a multi-dimensional parametric model with non-pharmacological policies for predicting the COVID-19 pandemic casualties. IEEE Access. 2020;8 doi: 10.1109/ACCESS.2020.3044929. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Coşkun H., Yıldırım N., Gündüz S. The spread of COVID-19 virus through population density and wind in Turkey cities. Sci Total Environ. 2021;751 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.141663. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Şahin M. Impact of weather on COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Sci Total Environ. 2020;728 doi: 10.1016/j.scitotenv.2020.138810. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mahmut Ö. Educational policy actions by the ministry of national education in the times of COVID-19 pandemic in Turkey. Kastam Eğit Derg. 2020;28(3):1124–1129. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Morgul E., Bener A., Atak M., Akyel S., Aktaş S., Bhugra D., et al. COVID-19 pandemic and psychological fatigue in Turkey. Int J Soc Psych. 2020 doi: 10.1177/0020764020941889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Satici B., Gocet-Tekin E., Deniz M.E., Satici S.A. Adaptation of the fear of COVID-19 scale: Its association with psychological distress and life satisfaction in Turkey. Int J Ment Health Addic. 2020:1–9. doi: 10.1007/s11469-020-00294-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Cucinotta D., Vanelli M. WHO declares COVID-19 a pandemic. Acta Bio Medic: Atenei Parmensis. 2020;91(1):157. doi: 10.23750/abm.v91i1.9397. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]