Abstract

Introduction

Evidence relating to long-term outcomes of online education programs is largely lacking and head-to-head comparisons of different delivery formats are very rare. The aims of the study were to test whether eLearning Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) or blended training (eLearning plus face-to-face course delivery), implemented in an Australian public sector workplace, were more effective than a control intervention at 1-year and 2-year follow-up, and whether blended MHFA training was more effective than eLearning alone.

Material and methods

Australian public servants (n = 608 at baseline) were randomly assigned to complete an eLearning MHFA course, a blended MHFA course or Red Cross eLearning Provide First Aid (PFA) (the control) and completed online questionnaires pre- and post-training and one and two years later (n = 289, n = 272, n = 243 at post, 1- and 2-year follow-up respectively). The questionnaires were based on vignettes describing a person with depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD). Primary outcomes were mental health first aid knowledge, desire for social distance and quality of support provided to a person in the workplace. Secondary outcomes were recognition of mental health problems, beliefs about treatment, helping intentions and confidence, personal stigma, quality of support provided to a person outside the workplace, self-reported professional help seeking and psychological distress.

Results

At 1-year follow-up, both eLearning and blended courses produced greater improvements than PFA training in knowledge, confidence and intentions to help a person with depression or PTSD, beliefs about dangerousness and desire for social distance. At 2-year follow-up, some of these improvements were maintained, particularly those relating to knowledge and intentions to help someone with PTSD. When eLearning and blended courses were compared at 1-year follow-up, the blended course led to greater improvements in knowledge and in confidence and intentions to help a person with depression. At 2-year follow-up, improvements in the quality of help provided to a person with a mental health problem outside the workplace were greater in participants in the blended course.

Conclusions

Both blended and eLearning MHFA courses led to significant longer-term improvements in knowledge, attitudes and intentions to help a person with a mental health problem. Blended MHFA training led to an improvement in the quality of helping behaviours and appears to be more effective than online training alone.

Trial registration

ACTRN12614000623695 registered on 13/06/2014 (prospectively registered).

Trial registry record url: https://www.anzctr.org.au/Trial/Registration/TrialReview.aspx?id=366410&isReview=true

Keywords: Mental Health First Aid, eLearning, Mental health literacy, Blended learning, Depression

Highlights

-

•

The effects of Mental Health First Aid training last for up to 2 years.

-

•

MHFA blended learning (online plus face-to-face) led to greater improvements than online only MHFA in knowledge and in confidence and intentions to help a person with depression.

-

•

At 2-year follow-up, blended MHFA led to greater improvements in behavioural outcomes.

1. Introduction

eLearning has seen an enormous growth in popularity in the last two decades, particularly in the higher education sector (Stone, 2019). This long-term trend is likely to continue with the increasing maturity of a generation of ‘digital natives’ and may also be accelerated as a result of the Covid-19 pandemic, which has seen the education and training sector swiftly transition to eLearning (often in the form of blended learning with a combination of eLearning and video-conferencing components). The longer-term impacts of these shifts are not yet known but they are likely to have a profound impact on practice in higher education institutions, health professional training and also in adult education and training programs (Curran et al., 2017). Given that many such interventions go beyond provision of knowledge and aim to teach skills and influence behaviour, a critical question relates to whether blended learning is more effective than eLearning alone (Blieck et al., 2019). In many contexts, such interventions may involve practicing interactions with other people, and it is possible that blended learning is more effective than eLearning in supporting the acquisition and use of skills, particularly in the longer term. However, evidence relating to long-term outcomes of adult education programs is largely lacking and head-to-head comparisons of different delivery formats are very rare (Liu et al., 2016; Vallee et al., 2020).

This paper reports on the 1-year and 2-year follow-up of a randomised controlled trial (RCT) of Mental Health First Aid (MHFA) training implemented in a workplace setting and offers the opportunity to investigate whether blended learning is more effective than eLearning. MHFA training teaches members of the public how to help a person developing a mental health problem or in a mental health crisis (e.g. at immediate risk of suicide) (Kitchener and Jorm, 2002). The first aid is given until appropriate professional treatment is received or until the crisis resolves. The program, which was developed in Australia in 2000, gives an overview of the most common and disabling mental health problems, introduces a five-component MHFA Action Plan and then applies these actions to help people with problems of depression, anxiety disorders, psychosis and substance use disorder as well as crisis situations including suicidal behaviours, panic attacks, traumatic events, aggressive behaviour, and acute intoxication (Kitchener et al., 2017). Originally delivered face-to-face, since 2008 an eLearning version of the Standard MHFA training course (for adults helping adults) has been available and has been shown to be more effective than wait-list control in improving knowledge and attitudes (Jorm et al., 2010). In 2014 a blended version of the course was developed (the same eLearning course plus an additional 4-h face-to-face session) and an RCT evaluated both the eLearning MHFA and blended MHFA courses implemented in a workplace setting. At post-test, this RCT found that both courses had more positive effects than a control intervention (Red Cross Provide First Aid (PFA)) on mental health first aid knowledge, desire for social distance, personal stigma, beliefs about professional treatments, and intentions and confidence in helping a person with depression or PTSD (Reavley et al., 2018a). There were very small non-significant differences between the eLearning MHFA and blended MHFA courses on these outcome measures. However, course satisfaction ratings were higher from participants in the blended MHFA course, potentially leading to greater benefits in the longer term.

Therefore, the principal aim of this study was to compare the longer-term effects (at 1-year and 2-year follow-up) of eLearning or blended (eLearning plus face-to-face course delivery) MHFA training with PFA on knowledge, stigmatising attitudes, confidence in providing support and intentions to provide support to a person with depression or PTSD. A secondary aim was to compare the longer-term effects of eLearning and blended learning on these outcomes. Participants were members of the public service in Victoria and the Australian Capital Territory (ACT), Australia.

2. Methods

2.1. Participants

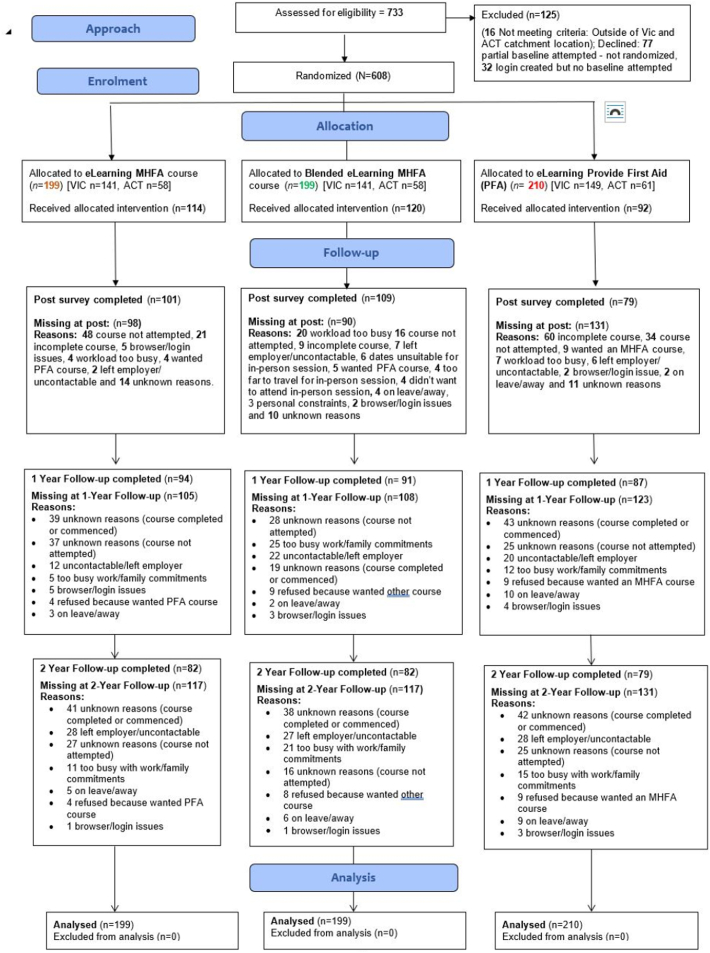

As described previously (Reavley et al., 2018a), public servants in the state of Victoria and the ACT who were aged 18 and over and did not hold a current certificate in either MHFA or PFA were eligible for participation. The CONSORT flow diagram of the number of participants at each stage of the trial is given in Fig. 1. At baseline, 74.1% of participants were female, the mean age of participants was 41.2 years (SD = 10.9; females Mage = 40.5, SD = 10.9; males Mage = 43.3, SD = 10.6), 87.1% spoke only English at home, 66.1% were tertiary educated, 1.2% were Aboriginal or Torres Strait Islander, 65.4% were married or in de facto relationships and 31.2% managed staff. All the participants included in the analyses completed the baseline questionnaire and the three groups were similar in baseline sociodemographic characteristics, indicating that randomization resulted in comparable groups (Reavley et al., 2018a). There were 272 participants (44.7%) with data at 1-year follow-up, 243 participants (40.0%) at 2-year follow-up, and 325 (53.5%) with data at either follow-up point. Predictors of missingness were explored with simple logistic regression models (see Table S1). Participants were less likely to be missing at follow-up if they had a tertiary education (OR = 0.58, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.86) or were assigned to the blended course, as compared to the PFA course (OR = 0.61, 95% CI 0.39 to 0.95).

Fig. 1.

CONSORT flow diagram for the study.

2.2. Procedure

Recruitment was managed via a trial website at www.workplaceaid.net.au, which contained a Participant Information Sheet and a link to the baseline SurveyMonkey questionnaire. After completion of this questionnaire, participants were randomised to one of the three groups listed above and given instructions on how to access the relevant course. Participants were allowed to complete the training during work hours, with their manager's approval, avoiding busy times at work.

Data were collected at baseline, post training (participants were given 2 months to complete the assessment after they had completed the course), one-year follow-up and two-year follow-up. The measures and the way they were applied were identical in each condition. Participants were invited to complete an online questionnaire via SurveyMonkey after they had completed the eLearning course, or had attended the face-to-face course. They were also sent emails with links to complete the questionnaire at 1-year and 2-year follow-up and given 2 months to complete each questionnaire. Up to 4 reminder emails were sent at each timepoint.

2.3. Randomization

Randomization was carried out by a random integer generator programmed on the trial website to give values of 1 = eLearning MHFA; 2 = Blended MHFA and 3 = PFA eLearning (see http://php.net/manual/en/function.rand.php). Allocation was concealed as randomization was computer generated. Blinding was not possible due to the nature of the interventions.

2.4. Interventions

2.4.1. eLearning MHFA

This intervention was a 6-h eLearning MHFA course accessed via the MHFA Australia web portal (mhfa.com.au). The eLearning MHFA course teaches a 5-component MHFA Action Plan for responding to developing mental health problems such as depression, anxiety problems, psychosis and substance use problems, and crises including suicidal thoughts and behaviours, non-suicidal self-injury, panic attacks, traumatic events, severe psychotic states, severe effects from drug and alcohol abuse, and aggressive behaviours. Each module included interactive content on case studies, audio and video content depicting stories of lived experience and demonstrating how to provide mental health first aid, followed by questions or other activities. Each participant received a hard-copy manual (Kitchener et al., 2017). Participants received weekly automated emails for 6 weeks to pace them through the material. Each section had a quiz at the end and monthly reports were extracted to monitor course progress.

2.4.1.1. Blended MHFA

This intervention included the 6-h eLearning course described above plus a 4-h face-to-face session, which reviewed the contents of the online course through quizzes and discussion. It also included case studies and role plays to give participants more experience in applying the MHFA Action Plan in different work-related situations. Group training was completed within 3 months of eLearning course completion.

2.4.1.2. Provide first aid

This intervention was a 4-h eLearning PFA course delivered via the Australian Red Cross online portal. The course teaches the fundamental principles, knowledge and skills to provide emergency care for injuries and illnesses in the home or the workplace. It was chosen as a control as it teaches useful skills, uses a similar mode of administration to the eLearning MHFA training and involves a similar time commitment. Participants received weekly emails for 6 weeks to pace them through the material. Reports from Red Cross were obtained to monitor course progress and flag course completers.

2.4.2. Outcomes

After completing a section comprising questions on sociodemographic characteristics, participants were asked to read a vignette of a person ‘John’ meeting the DSM criteria for major depressive disorder with suicidal thoughts and ‘Paula’ meeting the DSM criteria for PTSD (Reavley and Jorm, 2011; Slade et al., 2009) (see Table S2 for details of the vignettes). Subsequent questions were based on these vignettes.

2.4.2.1. Primary outcome measures

These were as follows.

2.4.2.1.1. Mental health first aid knowledge

This was measured using a 16-item true/false quiz based on the content of the Mental Health First Aid Manual (Kitchener et al., 2017). This measure has been shown to discriminate between people who have been trained in MHFA and those who have not (Morgan et al., 2018).The number of correct responses was converted into a percentage. Example items are: Q4. Exercise can help relieve depression (True); Q5. Recovery from anxiety disorders requires facing situations which are anxiety provoking (True); Q11. It is not a good idea to ask someone if they are feeling suicidal in case you put the idea in their head (False).

2.4.2.1.2. Desire for social distance

This was measured by the Social Distance Scale (Link et al., 1999) in relation to the vignettes described above. This scale asks about a participant's willingness to undertake a range of activities with the person in the vignette (e.g. work closely on a project, move next door or spend an evening). It is widely used and has been shown to have a single factor structure (Jorm and Oh, 2009; Yap et al., 2014). The internal consistency of the scales in this sample (omega total) was 0.88 for depression and 0.91 for PTSD. Scores were dichotomised at the median of pre- and post-scores in order to be consistent with the approach used in the analyses of pre-post results, which was taken due to distribution of the residuals not suiting a linear model However, with an additional two assessment points, the linear model fit reasonably well, so it could also be analysed as a continuous measure.

2.4.2.1.3. Self-reported supportive behaviours if someone at work develops a mental health problem

At 1-year and 2-year follow-up, participants were asked if anyone they had worked with had any sort of mental health problem. If they responded ‘yes’, they were asked if there was more than one person and, if yes, they were then asked to think about the person they knew best. They were asked about the person's age, gender and whether the person was a co-worker, superior, person working under their supervision or other. They were asked what they thought the mental health problem was and whether they had tried to help the person with the problem over the last 12 months. If they responded ‘no’, they were also asked an open-ended question about the reasons they didn't help the person with the problem and if ‘yes’, they were asked to describe all the things they did to help (also open-ended). Scoring was based on the MHFA Action Plan (Rossetto et al., 2014), which has the following components: Approach the person, assess and assist with any crisis; Listen non-judgementally; Give support and information; Encourage appropriate professional help; Encourage other supports. Responses received a score of 0–2 points for each component of the plan. Total scores ranged from 0 to 12. Open-ended responses were scored blinded to allocation or occasion. A random sample of 50 responses were double-coded, with inter-rater reliability (ICC) of 0.78. Participants who provided data on helping behaviour at any time point were included in the analyses.

2.4.2.2. Secondary outcome measures

2.4.2.2.1. Recognition of mental health problems

After being presented with the vignettes, participants were asked an open-ended question, “What, if anything, do you think is wrong with John/Paula?” For the depression vignette, participants were assessed as having correctly recognised the problem if they mentioned ‘depressed’ or ‘depression’ in their response. For the PTSD vignette, responses with any mention of PTSD, post-traumatic stress, or post-traumatic stress disorder were assessed as correct.

2.4.2.2.2. Beliefs about treatment

These were assessed using a 16-item scale based on the 2011 National Survey of Mental Health Literacy and Stigma (Reavley et al., 2014) and a consensus between Australian clinical psychologists, psychiatrists, and GPs established by a national survey (Morgan et al., 2013). Participants were presented with sources of potential help for depression and received a point for rating the following as helpful: a typical family GP or doctor; a psychiatrist; a psychologist; becoming more physically active; reading about people with similar problems and how they have dealt with them; psychotherapy; cognitive behaviour therapy; cutting out alcohol altogether; and antidepressants. They also scored 1 point for rating ‘dealing with the problem alone’ as harmful. For PTSD, they received a point for rating the following as helpful: a typical family GP or doctor; a psychiatrist; a psychologist; becoming more physically active; reading about people with similar problems and how they have dealt with them; courses on relaxation, stress management, meditation or yoga; psychotherapy; cognitive behaviour therapy; and receiving information about his problem from a health educator.

2.4.2.2.3. Helping intentions and confidence

Intentions to provide help to the person in the vignette were assessed by asking participants to rate the following statement on a 7-point scale ranging from 1 = Strongly Disagree to 7 = Strongly Agree: If John/Paula was a co-worker, I would help him/her. Responses were coded into two categories: strongly agree/agree vs other. This was followed with, “Describe all the things you would do to help John/Paula.” (open-ended response). Scoring was based on the MHFA Action Plan (Rossetto et al., 2014) (see above). A random sample of 50 responses were double coded for each vignette, and inter-rater reliability (ICC) was 0.88 for depression and 0.94 for PTSD.

Confidence in providing help to someone at work with depression and PTSD was assessed by asking participants to rate the following on a 5-point scale ranging from 1 = Not at all to 5 = Extremely: “How confident do you feel in helping someone at work with a problem like John/Paula?” (Kitchener and Jorm, 2002).

2.4.2.2.4. Personal stigma

The Personal Stigma Scale was used to measure participants' stigmatising attitudes to the person described in the vignette (Griffiths et al., 2004). High scores indicate low stigmatising attitudes. Exploratory Structural Equation Modelling has shown this scale to have factors measuring belief that a person with a mental health problem is weak not sick, and belief that they are dangerous or unpredictable (Yap et al., 2014). The Omega coefficient in this sample for’ Weak not sick’ stigma was 0.83 for depression and 0.82 for PTSD. For Dangerous/unpredictable stigma, the Omega coefficient was 0.70 for depression and 0.72 for PTSD. ‘Weak not sick’ scores showed substantial negative skew so were dichotomised at the median, which was the highest possible score (5) for both depression and PTSD vignettes.

2.4.2.2.5. Self-reported supportive behaviours if someone outside work develops a mental health problem

At 1-year and 2-year follow-up, participants were asked if any of their family or friends outside of the workplace had any sort of mental health problem. If ‘yes’, they were asked if there was more than one person and, if ‘yes’, were then asked to think about the person they knew best. They were asked about the person's age, gender and whether the person was a family member, friend, acquaintance, neighbour or other. They were asked what they thought the mental health problem was and whether they had tried to help the person with the problem over the last 12 months. If they responded ‘no’, they were also asked an open-ended question about the reasons they didn't help the person with the problem and if ‘yes’, they were asked to describe all the things they did to help (also open-ended). Scoring was based on the MHFA Action Plan (described above) (Rossetto et al., 2014). A random sample of 50 responses were double-coded, with inter-rater reliability (ICC) of 0.86.

2.4.2.2.6. Participants' help-seeking for a mental health problem

Participants were asked if they had any sort of mental health problem over the last 12 months. If ‘yes’, they were asked what they thought the problem was and if they had done anything to deal with the problem in the last 12 months. If ‘yes’, they were asked to describe all the things they did (open-ended). Verbatim responses were scored for the presence of an appropriate source of help. Participants scored 1 if they mentioned any of the following professionals or treatments: counselling, GP, professional help, Employee Assistance Program (EAP), medication, exercise, meditation or self-help books/websites.

2.4.2.2.7. Psychological distress

Participant psychological distress was assessed by the 12-month version of the Kessler 6 (K6) mental health symptom screening questionnaire (Kessler et al., 2010). This questionnaire asks participants to think about one month in the last 12-months when they were most depressed, anxious, or emotionally stressed. It contains 6 items and the resulting score range is between 6 and 30 with a cut-off point of ≥19 indicating a high level of psychological distress.

2.4.3. Sample size estimation

In order to calculate the required sample size, we considered the main hypothesis of interest to be the following: that blended MHFA training would be superior to MHFA eLearning in achieving improvements in MHFA knowledge. The sample size required to detect differences between these two modes of training was larger than that required to detect differences between these modes and PFA training. Consequently, we chose a small effect size to evaluate the difference between the two modes of MHFA training, as an effect size smaller than this may not be meaningful in terms of participant outcomes. According to Stata Release 12, 165 participants were required per group. For a repeated measures design, with 1 pre-training measure and 3 post-training measures, using the change method of sample size calculation and assuming a conservative 0.70 correlation between pre- and post-measurements (based on (Means et al., 2010)), to detect an effect size of Cohen's d = 0.20 (or h = 0.20), with a power = 0.80 and an alpha = 0.05, and increasing the sample size by 20% to account for attrition, the total sample size required was estimated to be 594 (198 participants per group).

2.4.4. Adverse events

In the event that a participant felt distressed during survey completion or while undertaking the training, a list of contacts was included at the end of each online survey. This included phone numbers for Lifeline, Suicideline (Victoria only), SANE, Emergency Services (000) and relevant EAP providers. Lifeline's Online Crisis Chat link was also included. Participants were encouraged to contact the trial manager to report any adverse events. None were reported.

2.4.5. Ethics

The study was approved by the University of Melbourne Human Ethics Sub-Committee (Ethics ID 1341345.2). Informed consent was obtained from all participants via an online ‘I agree to participate’ clickable link.

2.4.6. Design and data analysis

The study, which was registered with the Australian and New Zealand Clinical Trials Registry (ACTRN12614000623695) on 13 June 2014, was a parallel group RCT with participants randomised to eLearning MHFA, blended MHFA or PFA eLearning in a 1:1:1 ratio. Data were collected at baseline and 1-year and 2-year follow-up.

An intention-to-treat approach was used, with all participants included in the analyses. Data were analysed using mixed-effects models for continuous and binary outcome variables, with group-by-measurement occasion interactions. This method takes into account the hierarchical structure of the data in the analysis of differences between the groups, i.e. the correlation of measurement occasions within participants. It can produce unbiased estimates when a proportion of the participants withdraw before the completion of the study, based on the reasonable assumption that these data are missing at random (Rabe-Hesketh and Skrondal, 2008). As tertiary-educated participants were less likely to be missing data at follow-up, education was included as a fixed effect in order to help meet the missing at random assumption. Effect sizes (Cohen's d) were calculated by dividing the difference in mean change in each condition by the pooled standard deviation at follow-up. Analyses were performed in Stata 15 and the significance level was set at p < .05.

2.5. Results

At 1-year follow-up, 272 participants were retained in total, with n = 94, n = 91 and n = 87 in the eLearning MHFA, blended MHFA and PFA groups, respectively. At 2-year follow-up 243 participants were retained in total, with n = 82, n = 82 and n = 79 in the eLearning MHFA, blended MHFA and PFA groups, respectively (see Fig. 1). Baseline, 1-year and 2-year scores on all continuous and binary outcome measures are presented in Supplementary Tables S3 and S4 respectively. Table 1, Table 2 present the estimated mean changes from baseline to 1-year and 2-year follow-up respectively, and Table 3 presents the changes in binary outcomes for 1-year and 2-year follow-up.

Table 1.

Estimated mean changes from baseline to 1-year follow-up.

| Baseline to 1-year follow-up |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHFA eLearning vs PFA |

Blended MHFA vs PFA |

MHFA blended vs eLearning |

||||||||||

| Mean diff | 95% CI | d | 95% CI | Mean diff | 95% CI | d | 95% CI | Mean diff | 95% CI | d | 95% CI | |

| MHFA knowledge | 6.45b | 2.09 to 10.81 | 0.45 | 0.14 to 0.75 | 12.65c | 8.30 to 17.00 | 0.90 | 0.59 to 1.22 | 6.20b | 1.92 to 10.47 | 0.41 | 0.12 to 0.70 |

| Quality of MHFA towards a work colleague | 0.51 | −0.26 to 1.28 | 0.66 | −0.01 to 1.33 | 0.65 | −0.11 to 1.40 | 0.32 | −0.30 to 0.94 | 0.13 | −0.56 to 0.83 | −0.33 | −0.91 to 0.24 |

| Quality of MHFA towards another person | 0.57 | −0.06 to 1.19 | 0.49 | 0.02 to 0.96 | 0.11 | −0.48 to 0.70 | 0.41 | −0.03 to 0.85 | −0.45 | −1.04 to 0.13 | −0.25 | −0.67 to −0.18 |

| Social distance - depression | −0.04 | −0.17 to 0.09 | −0.10 | −0.40 to 0.19 | −0.08 | −0.21 to 0.04 | −0.18 | −0.47 to 0.12 | −0.04 | −0.17 to 0.08 | −0.09 | −0.36 to 0.22 |

| Social distance - PTSD | −0.06 | −0.20 to 0.07 | −0.22 | −0.52 to 0.07 | −0.07 | −0.20 to 0.07 | −0.17 | −0.47 to 0.13 | 0.00 | −0.13 to 0.13 | 0.06 | −0.23 to 0.35 |

| Confidence - depression | 0.06 | −0.19 to 0.30 | −0.03 | −0.32 to 0.26 | 0.36b | 0.12 to 0.61 | 0.42 | 0.12 to 0.72 | 0.30a | 0.06 to 0.55 | 0.48 | 0.19 to 0.77 |

| Confidence - PTSD | 0.42b | 0.15 to 0.68 | 0.41 | 0.11 to 0.71 | 0.58c | 0.31 to 0.84 | 0.64 | 0.33 to 0.94 | 0.16 | −0.10 to 0.43 | 0.21 | −0.08 to 0.50 |

| MHFA intentions - depression | 0.64a | 0.07 to 1.22 | 0.27 | −0.03 to 0.56 | 1.50c | 0.92 to 2.08 | 0.73 | 0.43 to 1.03 | 0.86b | 0.29 to 1.43 | 0.45 | 0.16 to 0.74 |

| MHFA intentions - PTSD | 0.95c | 0.45 to 1.45 | 0.67 | 0.36 to 0.97 | 1.27c | 0.77 to 1.76 | 0.79 | 0.49 to 1.10 | 0.32 | −0.18 to 0.81 | 0.10 | −0.19 to 0.39 |

| Prof help beliefs - depression | 0.29 | −0.30 to 0.87 | 0.16 | −0.14 to 0.45 | 0.56 | −0.03 to 1.14 | 0.31 | 0.01 to 0.60 | 0.27 | −0.31 to 0.85 | 0.18 | −0.11 to 0.47 |

| Prof help beliefs - PTSD | 0.30 | −0.25 to 0.86 | 0.27 | −0.03 to 0.57 | 0.38 | −0.17 to 0.93 | 0.26 | −0.03 to 0.56 | 0.08 | −0.47 to 0.62 | −0.01 | −0.30 to 0.28 |

| Stigma - Dangerous/unpredictable - Depression | 0.17a | 0.04 to 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.04 to 0.63 | 0.17a | 0.03 to 0.31 | 0.33 | 0.03 to 0.62 | 0.00 | −0.14 to 0.13 | −0.02 | −0.31 to 0.27 |

| Stigma - Dangerous/unpredictable - PTSD | 0.13 | −0.01 to 0.27 | 0.38 | 0.08 to 0.68 | 0.12 | −0.02 to 0.26 | 0.33 | 0.03 to 0.63 | 0.00 | −0.14 to 0.13 | −0.06 | −0.35 to 0.23 |

PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; MHFA: Mental Health First Aid, PFA: Provide First Aid.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 2.

Estimated mean changes from baseline to 2-year follow-up.

| Baseline to 2-year follow-up |

||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHFA eLearning vs PFA |

Blended MHFA vs PFA |

MHFA blended vs eLearning |

||||||||||

| Mean diff | 95% CI | d | 95% CI | Mean diff | 95% CI | d | 95% CI | Mean diff | 95% CI | d | 95% CI | |

| MHFA knowledge | 8.19c | 3.65 to 12.72 | 0.50 | 0.18 to 0.81 | 14.86c | 10.36 to 19.36 | 0.98 | 0.64 to 1.31 | 6.67b | 2.18 to 11.17 | 0.47 | 0.16 to 0.78 |

| Quality of MHFA towards a work colleague | 0.40 | −0.40 to 1.25 | −0.14 | −0.90 to 0.62 | −0.15 | −0.95 to 0.66 | −0.37 | −1.07 to 0.34 | −0.55 | −1.31 to 0.22 | −0.20 | −0.86 to 0.46 |

| Quality of MHFA towards another person | −0.07 | −0.72 to 0.58 | 0.23 | −0.28 to 0.74 | 1.19c | 0.57 to 1.81 | 1.25 | 0.73 to 1.77 | 1.27c | 0.64 to 1.90 | 1.01 | 0.48 to 1.53 |

| Social distance - depression | 0.02 | −0.12 to 0.15 | −0.06 | −0.37 to 0.25 | 0.01 | −0.12 to 0.15 | −0.03 | −0.34 to 0.27 | 0.00 | −0.14 to 0.13 | 0.03 | −0.28 to 0.33 |

| Social distance - PTSD | −0.08 | −0.22 to 0.06 | −0.29 | −0.61 to 0.02 | −0.04 | −0.18 to 0.10 | −0.10 | −0.41 to 0.21 | 0.04 | −0.09 to 0.18 | 0.18 | −0.13 to 0.49 |

| Confidence - depression | 0.28a | 0.02 to 0.53 | 0.27 | −0.04 to 0.58 | 0.21 | −0.05 to 0.46 | 0.30 | −0.01 to 0.62 | −0.07 | −0.32 to 0.18 | 0.00 | −0.31 to 0.31 |

| Confidence - PTSD | 0.22 | −0.06 to 0.49 | 0.29 | −0.02 to 0.61 | 0.27 | −0.01 to 0.54 | 0.36 | 0.05 to 0.67 | 0.05 | −0.22 to 0.32 | 0.04 | −0.27 to 0.35 |

| MHFA intentions - depression | −0.05 | −0.66 to 0.55 | −0.01 | −0.32 to 0.30 | 0.43 | −0.17 to 1.04 | 0.28 | −0.03 to 0.59 | 0.49 | −0.11 to 1.09 | 0.25 | −0.05 to 0.56 |

| MHFA intentions - PTSD | 0.45 | −0.06 to 0.96 | 0.27 | −0.04 to 0.58 | 0.91c | 0.40 to 1.43 | 0.61 | 0.29 to 0.93 | 0.47 | −0.04 to 0.98 | 0.28 | −0.03 to 0.59 |

| Prof help beliefs - depression | 0.16 | −0.45 to 0.77 | 0.17 | −0.14 to 0.49 | 0.58 | −0.02 to 1.19 | 0.37 | 0.05 to 0. 68 | 0.43 | −0.18 to 1.03 | 0.21 | −0.10 to 0.52 |

| Prof help beliefs - PTSD | 0.31 | −0.27 to 0.89 | 0.33 | 0.02 to 0.65 | 0.78b | 0.21 to 1.35 | 0.50 | 0.19 to 0.82 | 0.47 | −0.10 to 1.04 | 0.19 | −0.12 to 0. 50 |

| Stigma - Dangerous/unpredictable - Depression | 0.08 | −0.06 to 0.22 | 0.17 | −0.14 to 0.48 | 0.06 | −0.08 to 0.20 | 0.14 | −0.17 to 0.45 | −0.02 | −0.16 to 0.12 | −0.04 | −0.34 to 0.27 |

| Stigma - Dangerous/unpredictable - PTSD | 0.14 | −0.01 to 0.28 | 0.35 | 0.03 to 0. 67 | 0.13 | −0.02 to 0.27 | 0.28 | −0.04 to 0. 59 | −0.01 | −0.15 to 0.13 | −0.08 | −0.39 to 0.23 |

PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; MHFA: Mental Health First Aid, PFA: Provide First Aid.

p < .05.

p < .01.

p < .001.

Table 3.

Estimated change for dichotomous outcomes from baseline to 1- and 2-year follow-up.

| Baseline to 1-Year follow-up |

Baseline to 2-year follow-up |

|||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MHFA eLearning vs PFA |

Blended MHFA vs PFA |

MHFA blended vs eLearning |

MHFA eLearning vs PFA |

Blended MHFA vs PFA |

MHFA blended vs eLearning |

|||||||

| OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | OR | 95% CI | |

| Social distance ≤= median - depression | 5.25a | 1.16 to 23.85 | 6.90a | 1.51 to 31.61 | 1.31 | 0.26 to 6.68 | 2.48 | 0.48 to 12.65 | 2.10 | 0.43 to 10.37 | 0.85 | 0.16 to 4.65 |

| Social distance ≤= median - PTSD | 1.04 | 0.33 to 3.22 | 1.20 | 0.39 to 3.71 | 1.16 | 0.38 to 3.51 | 0.99 | 0.30 to 3.21 | 1.48 | 0.45 to 4.88 | 1.49 | 0.46 to 4.84 |

| Helped work colleague | 2.19 | 0.13 to 35.88 | 9.17 | 0.26 to 322.61 | 4.18 | 0.11 to 153.66 | 2.42 | 0.13 to 44.11 | 0.26 | 0.02 to 4.19 | 0.62 | 0.05 to 7.34 |

| Helped another person | 2.90 | 0.20 to 41.24 | 8.13 | 0.56 to 117.94 | 2.80 | 0.16 to 49.91 | 1.34 | 0.13 to 13.43 | 3.93 | 0.39 to 39.33 | 2.94 | 0.24 to 35.56 |

| Correct recognition of depression | 0.31 | 0.03 to 3.14 | 0.70 | 0.10 to 5.07 | 2.24 | 0.27 to 18.59 | 0.91 | 0.11 to 7.73 | 2.02 | 0.34 to 12.09 | 2.22 | 0.25 to 19.45 |

| Correct recognition of PTSD | 1.25 | 0.35 to 4.51 | 1.56 | 0.43 to 5.69 | 1.25 | 0.37 to 4.23 | 0.51 | 0.13 to 1.96 | 0.83 | 0.21 to 3.35 | 1.65 | 0.46 to 5.94 |

| Would help John (Agree/Strongly Agree) | 3.45a | 1.09 to 10.92 | 16.64b | 4.30 to 64.39 | 4.82a | 1.20 to 19.34 | 1.66 | 0.47 to 5.83 | 3.40 | 0.93 to 12.39 | 2.05 | 0.55 to 7.58 |

| Would help Paula (Agree/Strongly Agree) | 4.13a | 1.30 to 13.04 | 3.27a | 1.06 to 10.07 | 0.79 | 0.24 to 2.58 | 2.50 | 0.76 to 8.22 | 4.53a | 1.28 to 16.05 | 1.81 | 0.50 to 6.56 |

| Weak not sick ≥= median - Depression | 0.84 | 0.32 to 2.22 | 1.70 | 0.62 to 4.65 | 2.02 | 0.75 to 5.46 | 0.67 | 0.24 to 1.87 | 1.16 | 0.41 to 3.28 | 1.74 | 0.61 to 4.94 |

| Weak not sick ≥= median - PTSD | 1.25 | 0.41 to 3.78 | 1.27 | 0.41 to 3.98 | 1.02 | 0.33 to 3.10 | 1.17 | 0.37 to 3.67 | 1.16 | 0.36 to 3.71 | 1.00 | 0.31 to 3.17 |

| High psychological distress | 0.82 | 0.24 to 2.87 | 1.95 | 0.57 to 6.64 | 2.37 | 0.71 to 7.86 | 0.89 | 0.24 to 3.27 | 1.40 | 0.39 to 5.02 | 1.58 | 0.44 to 5.62 |

| Sought professional help | 0.39 | 0.03 to 5.15 | 0.71 | 0.05 to 10.13 | 1.84 | 0.17 to 19.99 | 0.23 | 0.01 to 3.44 | 0.28 | 0.02 to 4.22 | 1.23 | 0.11 to 14.17 |

PTSD: post-traumatic stress disorder; MHFA: Mental Health First Aid, PFA: Provide First Aid.

p < .05.

p < .001.

2.5.1. Primary outcomes

2.5.1.1. Mental health first aid knowledge

From baseline to 1-year follow-up, there were statistically significant greater improvements in knowledge in both MHFA eLearning (d = 0.45, 95% CI 0.14 to 0.75) and blended MHFA groups (d = 0.90, 95% CI 0.59 to 1.22) compared to PFA eLearning. The difference between MHFA eLearning and blended MHFA was statistically significant and small-to-moderate in size (d = 0.41, 95% CI 0.12 to 0.70). These differences were maintained at 2-year follow-up with similar effect sizes (d = 0.50 (95% CI 0.18 to 0.81), d = 0.98 (95% CI 0.64 to 1.31) and d = 0.47 (95% CI 0.16 to 0.78) respectively).

2.5.1.2. Desire for social distance

At both 1-year and 2-year follow-up, there were no statistically significant differences in change in desire for social distance (reported as continuous measures). When scores were dichotomised at the median (consistent with the approach used for the post-test analysis), there were statistically significantly greater improvements in desire for social distance from a person with depression in the eLearning MHFA (OR 5.25, 95% CI = 1.16 to 23.85, p = .032) and blended MHFA groups (OR 6.90, 95% CI 1.51 to 31.61, p = .013) compared to the PFA group at 1-year follow-up.

2.5.1.3. Self-reported supportive behaviours if someone at work develops a mental health problem

At baseline, 52.6% (n = 320) of participants reported working with a person with a mental health problem (eLearning 52.3% (n = 104); blended 52.3% (n = 104); PFA 53.3% (n = 112)). At 1-year follow-up, 53.6% (n = 140) of participants reported working with a person with a mental health problem (eLearning 57.8% (n = 52); blended 56.0% (n = 51), PFA 46.3% (n = 37)). At 2-year follow-up, 49.8% (n = 115) of participants reported working with a person with a mental health problem (eLearning 48.7% (n = 37); blended 58.8% (n = 47), PFA 41.3% (n = 31)).

At 1-year and 2-year follow-up, there were no statistically significant differences with baseline in changes in the quality of self-reported supportive behaviours to someone at work who developed a mental health problem.

2.5.2. Secondary outcomes

2.5.2.1. Recognition of mental disorders

For both depression and PTSD vignettes, there were high rates of recognition at baseline (over 90% for depression) and there were no statistically significant differences in change in recognition at 1-year and 2-year follow-up.

2.5.2.2. Beliefs about treatment

For both depression and PTSD vignettes, there were no statistically significant differences in changes in beliefs about professional help at 1-year and 2-year follow-up.

2.5.2.3. Quality of helping intentions and confidence

At 1-year follow-up, there were statistically significant greater increases in intentions to help a person with depression in both the MHFA eLearning and blended MHFA groups compared to PFA eLearning (OR = 3.45, p = .035 and OR = 16.64, p < .001 respectively). Similar results were seen for PTSD (OR = 4.13, p ≤ .016 and OR = 3.27, p = .039). The differences between MHFA eLearning and blended MHFA were statistically significant for depression (OR = 4.82, p = .026) but not for PTSD. At 2-year follow-up, only the difference in changes between blended MHFA and PFA for the PTSD vignette was statistically significant (OR = 4.53, p = .019).

At 1-year follow-up, there were statistically significant greater improvements in quality of helping intentions for depression and PTSD in both the MHFA eLearning and blended MHFA groups compared to PFA eLearning. The differences between MHFA eLearning and blended MHFA were statistically significant for depression (d = 0.45) but not for PTSD. At 2-year follow-up, only the difference in changes between blended MHFA and PFA for the PTSD vignette was statistically significant (d = 0.61).

At 1-year follow-up, there were statistically significant greater improvements in confidence for helping a person with depression in the blended MHFA group compared to PFA eLearning (d = 0.42) and in the blended MHFA group compared to eLearning MHFA (d = 0.48). For PTSD, at 1-year follow-up there were statistically significant greater improvements in confidence in the blended MHFA and eLearning groups compared to PFA eLearning (d = 0.41 and d = 0.64 respectively), but no differences between blended and eLearning groups. At 2-year follow-up, the only statistically significant difference in improvement was between eLearning and PFA for depression (d = 0.27).

2.5.2.4. Personal stigma

There were no statistically significant differences in changes in beliefs that people with depression or PTSD are ‘weak not sick’ at 1-year and 2-year follow-up. At 1-year follow-up only, there were statistically significant improvements in beliefs that people with depression were dangerous or unpredictable in the eLearning MHFA and blended MHFA courses when compared to PFA (d = 0.33 and d = 0.33 respectively). There were no differences between blended and eLearning courses.

2.5.2.5. Self-reported supportive behaviours if someone outside work develops a mental health problem

At baseline, 76.8% (n = 467) of participants reported knowing someone outside work with a mental health problem (eLearning 73.4% (n = 146); blended 79.9% (n = 159), PFA 77.1% (n = 162)). At 1-year follow-up, 65.1% (n = 168) of participants reported knowing someone outside work with a mental health problem (eLearning 60.0% (n = 54); blended 70.0% (n = 63), PFA 65.4% (n = 51)). At 2-year follow-up, 64.5% (n = 149) of participants reported knowing someone outside work with a mental health problem (eLearning 59.2% (n = 45); blended 70.0% (n = 56), PFA 64.0% (n = 48)).

At 2-year follow-up, blended MHFA led to statistically significant improvements in the quality of self-reported behaviours to someone outside work who developed a mental health problem, compared to both PFA (d = 1.25) and eLearning MHFA (d = 1.01).

2.5.2.6. Participant help-seeking for a mental health problem

At baseline, 36.7% (n = 223) of participants reported having a mental health problem (eLearning 36.2% (n = 72); blended 36.2% (n = 72), PFA 37.6% (n = 79)). At 1-year follow-up, 38.9% (n = 101) of participants reported having a mental health problem (eLearning 34.4% (n = 31); blended 44.0% (n = 40), PFA 38.0% (n = 30)). At 2-year follow-up, 39.4% (n = 91) of participants reported having a mental health problem (eLearning 38.2% (n = 29); blended 40.0% (n = 32), PFA 40.0% (n = 30)).

There were no statistically significant differences in changes in help-seeking for a mental health problem at 1-year and 2-year follow-up.

2.5.2.7. Psychological distress

There were no significant differences between courses in changes in psychological distress at 1-year and 2-year follow-up.

2.6. Discussion

This study aimed to test whether eLearning or blended MHFA training were more effective than a control intervention at 1-year and 2-year follow-up, and whether blended MHFA was more effective than eLearning alone. A focus on consistent effects rather than one-off significant findings showed that both eLearning and blended MHFA training led to greater improvements than PFA training in knowledge, some stigmatising attitudes and behavioural intentions. Compared to PFA, blended MHFA led to greater improvements in the quality of assistance provided to a person with a mental health problem outside the workplace. Compared to eLearning, blended MHFA led to greater improvements in knowledge, confidence and intentions to help a person with depression as well as in the quality of help provided to a person with a mental health problem outside the workplace.

The results of the current study also support the greater effectiveness of blended over eLearning course delivery, as effects were generally larger in the blended course. Previous analysis of pre-post data showed that the effects were similar for the eLearning and blended modes of MHFA courses, with most outcomes showing very small non-significant differences between the modes. However, there were some signs of blended MHFA being superior to eLearning MHFA, notably in quality of intentions to help a person with depression (Reavley et al., 2018a). Thus, this study makes a valuable contribution to the literature on the impact of modes of learning, which until now, has largely focused on students enrolled in formal education or health professional training, who may be expected to have higher levels of motivation for attending and completing online courses (Liu et al., 2016; Sitzmann et al., 2006). Results of the current study appear to support the addition of a face-to-face component for improving learner outcomes in the longer term. This may be partly explained by the fact that participants in the blended MHFA group were significantly more likely to complete the eLearning course (64.8% vs 55.3%) and there were also trends towards a higher number of completed modules and more time spent on the course overall among participants in that group. Participants were also more likely to rate the blended MHFA course highly in terms of usefulness, amount learned and intentions to recommend to others. These results suggest that these aspects of course satisfaction do translate into behaviour in the longer term, whether through increasing engagement with course material or through the in-depth discussion and practice of mental health first aid skills that took place in the face-to-face component of the blended course. Covid-19 has driven growth in videoconferencing and the recent development of an MHFA blended course involving videoconferencing rather than a face-to-face component (https://mhfa.com.au/blended-online-courses-covid-19). Future research should assess its effectiveness. These findings may also point to explore ways to increase engagement with eLearning course material, including the number of modules completed and time spent, possibly by including coaching support, as is common in online interventions for mental health problems (Baumeister et al., 2014).

This study, which is the longest follow-up of the standard adult MHFA training course to date, supports the benefits of the training in improving knowledge and attitudes in the longer term (Morgan et al., 2018). Previous MHFA trials have only assessed outcomes up to 6-months post training, although one recent study has assessed the effectiveness of the Youth MHFA training course (training for parents of teenagers) for up to 2 years (Morgan et al., 2019). However, in the current study, the primary outcome measure relating to increasing supportive behaviours at work did not change significantly. It is likely that this is partly due to lack of power to detect these effects as, at 1-year follow-up, as only 113 people provided data on what they did to help someone at work with a mental health problem (n = 42, n = 44 and n = 27 people in the eLearning, blended and PFA groups respectively). At 2-year follow-up, 90 people reported on the help provided to a person in the workplace (n = 30, n = 37 and n = 23 people in the eLearning, blended and PFA groups respectively). This meant that the numbers were below the required level to detect a medium effect size, which complicates interpretation of the results. This may be partly explained by low rates of disclosure to people in workplaces compared to family and friends. A recent Australian national survey showed that 64% of people with symptoms of psychological distress or a diagnosis of mental illness disclosed to some friends and 49% disclosed to some family members, whereas non-disclosure to supervisors (55%) and other people in the workplace (54%) was more likely than full or partial disclosure (Reavley et al., 2018b).

However, changes in intentions to help a person with either depression or PTSD were greater at 1-year follow-up for both the blended and eLearning courses, and at 2-year follow-up, changes in intentions to help a person with PTSD were greater in the blended vs PFA group. As previous research has shown that mental health first aid intentions positively predict behaviours at follow-up, this is promising (Yap and Jorm, 2012; Rossetto et al., 2016). However, other factors are important in the link between intentions and behaviour beyond having sufficient knowledge and confidence in what to do (Rossetto et al., 2018). When asked about the reasons why they did not help a person in the workplace, participants commonly mentioned that the person had sought professional help themselves in the past, was a “difficult” or very private person or the first aider didn't feel as if they had enough rapport with the person to offer help. While overcoming all such barriers is not likely to be possible, organisational level factors such as flexible working practices and those that emphasise the importance of support and openness of managers are likely to be necessary to improving workplace support (Evans-Lacko and Knapp, 2014).

These conclusions are supported by the findings relating to greater improvements in the quality of help provided to a person outside work with a mental health problem in the eLearning and blended groups. Effect sizes were in the moderate range. In this case, at 1-year follow-up only 147 people across the three groups provided data on what they did to help someone at work with a mental health problem. At 2-year follow-up, 129 people across the three groups reported on the help provided to a person in the workplace. However, given the potential benefits to people outside the workplace, these findings support the role of the workplace as a setting for interventions to improve mental health literacy in the adult population, even if the outcomes are not those directly relevant to the workplace (LaMontagne et al., 2014).

Strengths of the study include a rigorous design with an active control condition and a relatively long period of follow-up for a mental health education course, while limitations include the larger than expected attrition (with significantly greater dropout in those with lower levels of education and those assigned to the PFA group) and consequent lack of power to assess differences between the two modes of MHFA delivery, relating to the behavioural primary outcome in particular. Moreover, a lack of power led to low precision for some estimates. A key limitation of this study, as with other MHFA studies, is the lack of evidence of impact on any recipients of first aid. These may be direct, in that people feel supported and valued and, in the workplace, may be provided with workplace adjustments that benefit their mental health (Reavley et al., 2017), or may be through receipt of appropriate professional help. In the context of a recent study showing that people with major depressive disorder only obtained treatment that they considered helpful after they persisted in help-seeking after unhelpful treatments with up to nine prior professionals, this still presents considerable challenges (Harris et al., 2020).

2.7. Conclusions

Both blended and eLearning MHFA courses led to significant longer-term improvements in knowledge, attitudes and intentions to help a person with a mental health problem. Blended MHFA training led to an improvement in the quality of helping behaviours and appears to be more effective than online training alone. Further research should focus on replicating these findings and on extending them to blended courses involving videoconferencing rather than a face-to-face component.

Abbreviations

- MHFA

Mental Health First Aid

- PFA

Provide First Aid

- RCT

randomised controlled trial

- EAP

Employee Assistance Program

- OR

Odds ratio

- PTSD

post-traumatic stress disorder

- SD

standard deviation

- ICC

inter-rater reliability

- ACT

Australian Capital Territory

Funding

The trial was funded by the National Health and Medical Research Council (APP1061636), which played no role in the design of the study, data collection, analysis, interpretation of data or writing of the manuscript. AFJ is supported by National Health and Medical Research Council Investigator Grant. AM is supported by a University of Melbourne CR Roper Fellowship.

Declaration of competing interest

Professor Anthony Jorm (AFJ) and Betty Kitchener (BAK) are the co-founders of MHFA training. AFJ is a former Chair of the Board of MHFA International and BAK is a former member of the Board. BAK and NB are former CEOs of MHFA International. NJR, AJM and JF have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

AFJ, NJR and BAK contributed to the development and supervision of the project. JF was the trial manager and coded responses to open-ended responses. BAK and NB delivered MHFA face-to-face training. AJM carried out the data analysis. NJR drafted the manuscript and all other authors suggested improvements. We would like to thank Anna Ross for assistance with coding open-ended responses and Stefan Cvetkovski for his assistance with the original analysis plan.

Footnotes

Supplementary data to this article can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.invent.2021.100434.

Contributor Information

Nicola J. Reavley, Email: nreavley@unimelb.edu.au.

Amy J. Morgan, Email: ajmorgan@unimelb.edu.au.

Julie-Anne Fischer, Email: jfischer@unimelb.edu.au.

Anthony F. Jorm, Email: ajorm@unimelb.edu.au.

Appendix A. Supplementary data

Supplementary tables

References

- Baumeister H., Reichler L., Munzinger M., Lin J. The impact of guidance on internet-based mental health interventions — a systematic review. Internet Interv. 2014;1(4):205–215. [Google Scholar]

- Blieck Y., Ooghe I., Zhu C., Depryck K.S., Pynoo B., Van Laer H. Consensus among stakeholders about success factors and indicators for quality of online and blended learning in adult education: a Delphi study. Stud. Contin. Educ. 2019;41(1):36–60. [Google Scholar]

- Curran V., Matthews L., Fleet L., Simmons K., Gustafson D.L., Wetsch L. A review of digital, social, and mobile technologies in health professional education. J. Contin. Educ. Heal. Prof. 2017;37(3):195–206. doi: 10.1097/CEH.0000000000000168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evans-Lacko S., Knapp M. Importance of social and cultural factors for attitudes, disclosure and time off work for depression: findings from a seven country European study on depression in the workplace. PLoS ONE. 2014;9(3) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0091053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Griffiths K.M., Christensen H., Jorm A.F., Evans K., Groves C. Effect of web-based depression literacy and cognitive-behavioural therapy interventions on stigmatising attitudes to depression: randomised controlled trial. Br. J. Psychiatry. 2004;185:342–349. doi: 10.1192/bjp.185.4.342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harris M.G., Kazdin A.E., Chiu W.T., Sampson N.A., Aguilar-Gaxiola S., Al-Hamzawi A., Alonso J., Altwaijri Y., Andrade L.H., Cardoso G. Findings from world mental health surveys of the perceived helpfulness of treatment for patients with major depressive disorder. JAMA Psychiatry. 2020;77(8):830–841. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2020.1107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A.F., Oh E. Desire for social distance from people with mental disorders. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(3):183–200. doi: 10.1080/00048670802653349. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jorm A.F., Kitchener B.A., Fischer J.A., Cvetkovski S. Mental health first aid training by e-learning: a randomized controlled trial. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2010;44(12):1072–1081. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2010.516426. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kessler R.C., Green J.G., Gruber M.J., Sampson N.A., Bromet E., Cuitan M., Furukawa T.A., Gureje O., Hinkov H., Hu C.Y. Screening for serious mental illness in the general population with the K6 screening scale: results from the WHO world mental health (WMH) survey initiative. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2010;19(Suppl. 1):4–22. doi: 10.1002/mpr.310. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchener B.A., Jorm A.F. Mental health first aid training for the public: evaluation of effects on knowledge, attitudes and helping behavior. BMC Psychiatry. 2002;2:10. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-2-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kitchener B., Jorm A.F., Kelly C. 4th ed. Mental Health First Aid Australia; Melbourne: 2017. Mental Health First Aid Manual. [Google Scholar]

- LaMontagne A.D., Martin A., Page K.M., Reavley N.J., Noblet A.J., Milner A.J., Keegel T., Smith P.M. Workplace mental health: developing an integrated intervention approach. BMC Psychiatry. 2014;14:131. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-14-131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link B.G., Phelan J.C., Bresnahan M., Stueve A., Pescosolido B.A. Public conceptions of mental illness: labels, causes, dangerousness, and social distance. Am. J. Public Health. 1999;89(9):1328–1333. doi: 10.2105/ajph.89.9.1328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu Q., Peng W., Zhang F., Hu R., Li Y., Yan W. The effectiveness of blended learning in health professions: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2016;18(1) doi: 10.2196/jmir.4807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Means B., Toyama Y., Murphy R., Baki M. The effectiveness of online and blended learning: a meta-analysis of the empirical literature. Teach. Coll. Rec. 2010;115(030303) [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A.J., Jorm A.F., Reavley N.J. Beliefs of australian health professionals about the helpfulness of interventions for mental disorders: differences between professions and change over time. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2013;47(9):840–848. doi: 10.1177/0004867413490035. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A.J., Ross A., Reavley N.J. Systematic review and meta-analysis of mental health first aid training: effects on knowledge, stigma, and helping behaviour. PLoS ONE. 2018;13(5) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0197102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan A.J., Fischer J.A., Hart L.M., Kelly C.M., Kitchener B.A., Reavley N.J., Yap M.B.H., Cvetkovski S., Jorm A.F. Does mental health first aid training improve the mental health of aid recipients? The training for parents of teenagers randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2019;19(1):99. doi: 10.1186/s12888-019-2085-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabe-Hesketh S., Skrondal A. Classical latent variable models for medical research. Stat. Methods Med. Res. 2008;17(1):5–32. doi: 10.1177/0962280207081236. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N.J., Jorm A.F. Stigmatizing attitudes towards people with mental disorders: findings from an australian National Survey of mental health literacy and stigma. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2011;48(12):1086–1093. doi: 10.3109/00048674.2011.621061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N.J., Morgan A.J., Jorm A.F. Development of scales to assess mental health literacy relating to recognition of and interventions for depression, anxiety disorders and schizophrenia/psychosis. Aust. N. Z. J. Psychiatry. 2014;48(1):61–69. doi: 10.1177/0004867413491157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N.J., Morgan A.J., Jorm A.F. Discrimination and positive treatment towards people with mental health problems in workplace and education settings: findings from an Australian national survey. Stigma Health. 2017;2(4):254–265. [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N.J., Morgan A.J., Fischer J.A., Kitchener B., Bovopoulos N., Jorm A.F. Effectiveness of eLearning and blended modes of delivery of mental health first aid training in the workplace: randomised controlled trial. BMC Psychiatry. 2018;18(1):312. doi: 10.1186/s12888-018-1888-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reavley N.J., Morgan A.J., Jorm A.F. Disclosure of mental health problems: findings from an Australian national survey. Epidemiol. Psychiatr. Sci. 2018;27(4):346–356. doi: 10.1017/S204579601600113X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetto A., Jorm A.F., Reavley N.J. Quality of helping behaviours of members of the public towards a person with a mental illness: a descriptive analysis of data from an Australian national survey. Ann. General Psychiatry. 2014;13(1):2. doi: 10.1186/1744-859X-13-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetto A., Jorm A.F., Reavley N.J. Predictors of adults' helping intentions and behaviours towards a person with a mental illness: a six-month follow-up study. Psychiatry Res. 2016;240:170–176. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2016.04.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossetto A., Jorm A.F., Reavley N.J. Developing a model of help giving towards people with a mental health problem: a qualitative study of mental health first aid participants. Int. J. Ment. Heal. Syst. 2018;12:48. doi: 10.1186/s13033-018-0228-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sitzmann T., Kraiger K., Stewart D.B., Wisher R. The comparative effectiveness of web-based and classroom instruction: a meta-analysis. Pers. Psychol. 2006;59:623–664. [Google Scholar]

- Slade T., Johnston A., Oakley Browne M.A., Andrews G., Whiteford H. 2007 National Survey of mental health and wellbeing: methods and key findings. Aust N Z J Psychiatry. 2009;43(7):594–605. doi: 10.1080/00048670902970882. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stone C. Online learning in australian higher education: opportunities, challenges and transformations. Student Success. 2019;10(2):1–11. [Google Scholar]

- Vallee A., Blacher J., Cariou A., Sorbets E. Blended learning compared to traditional learning in medical education: systematic review and meta-analysis. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(8) doi: 10.2196/16504. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap M.B.H., Jorm A.F. Young people's mental health first aid intentions and beliefs prospectively predict their actions: findings from an Australian National Survey of Youth. Psychiatry Res. 2012;196(2–3):315–319. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2011.10.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yap M.B.H., Mackinnon A.J., Reavley N.J., Jorm A.F. The measurement properties of stigmatising attitudes towards mental disorders: results from two community surveys. Int. J. Methods Psychiatr. Res. 2014;23(1):49–61. doi: 10.1002/mpr.1433. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary tables