Abstract

Background

Sexual and gender minority (SGM) persons face a number of physical and mental health disparities closely linked to discrimination, social stigma, and victimization. Despite the acceptability and increasing number of digital health interventions focused on improving health outcomes among SGM people, there is a lack of reviews summarizing whether and how researchers assess engagement with social media–delivered health interventions for this group.

Objective

The objective of this systematic review was to synthesize and critique the evidence on evaluation of engagement with social media–delivered interventions for improving health outcomes among SGM persons.

Methods

We conducted a literature search for studies published between January 2003 and June 2020 using 4 electronic databases. Articles were included if they were peer-reviewed, in English language, assessed engagement with a social media–delivered health intervention for improving health outcomes among sexual and gender minorities. A minimum of two authors independently extracted data from each study using an a priori developed abstraction form. We assessed quality of data reporting using the CONSORT extension for pilot and feasibility studies and CONSORT statement parallel group randomized trials.

Results

We included 18 articles in the review; 15 were feasibility studies and 3 were efficacy or effectiveness randomized trials. The quality of data reporting varied considerably. The vast majority of articles focused on improving HIV-related outcomes among men who have sex with men. Only three studies recruited cisgender women and/or transgender persons. We found heterogeneity in how engagement was defined and assessed. Intervention usage from social media data was the most frequently used engagement measure.

Conclusion

In addition to the heterogeneity in defining and assessing engagement, we found that the focus of assessment was often on measures of intervention usage only. More purposeful recruitment is needed to learn about whether, how, and why different SGM groups engage with social media-interventions. This leaves significant room for future research to expand evaluation criteria for cognitive and emotional aspects of intervention engagement in order to develop effective and tailored social media-delivered interventions for SGM people. Our findings also support the need for developing and testing social media-delivered interventions that focus on improving mental health and outcomes related to chronic health conditions among SGM persons.

Keywords: Social media, Sexual and gender minorities, LGBTQ+, Digital health interventions, Mental health, Systematic review

Highlights

-

•

Digital interventions are widely acceptable to sexual and gender minorities (SGM).

-

•

There is heterogeneity in defining and assessing engagement across studies.

-

•

Current SGM social media interventions have narrow scopes and limited population.

-

•

Engagement in SGM-targeted interventions focuses mostly on micro level factors.

-

•

Better evaluating engagement is crucial to effective digital interventions for SGM.

1. Introduction

Sexual and gender minority (SGM, i.e., lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender, queer/questioning) persons face a number of physical and mental health disparities closely linked to discrimination, social stigma, and victimization (Meyer, 2003). While sexual minorities comprise persons whose sexual identity, attraction, and practices are different from the dominant culture (American Psychological Association, 2012; Cochat Costa Rodrigues et al., 2017), gender minorities include individuals whose gender identity (man, woman, other) or expression (masculine, feminine, other) is different from their sex assigned at birth (male, female) (American Psychological Association, 2015). The frequently chronic trajectory of the physical and mental health conditions SGM persons face makes them potentially amenable to behavioral intervention programs that seek to boost protective factors, reduce risk factors, manage symptoms, or improve treatment adherence. Indeed, digital technology delivered interventions (e.g., via apps, web-based, social media) are widely acceptable among SGM persons (Gilbey et al., 2020).

Social media can be defined as “a group of Internet-based applications that allow the creation and exchange of user-generated content” (Kaplan and Haenlein, 2010), and it includes a wide range of platforms in the form of websites mobile apps (e.g., Twitter, Snapchat), messaging apps (e.g., WhatsApp, Facebook Messenger), and location-based apps, i.e., an app that allows a person to simultaneously use GPS to broadcast their location and be located. (e.g., Grindr, Scruff). SGM individuals are heavy users of social media platforms and apps (Escobar-Viera et al., 2018; Seidenberg et al., 2017), to which they turn to explore their identity, find events, services and health information, meet friends or potential partners, and seek social support and affirmation (DeHaan et al., 2013; Harper et al., 2016). These reasons, along with their desire to avoid potential negative experiences (e.g., stigmatization, denial, refusal of services) at in-person health care settings (Ayhan et al., 2020), might influence SGM people to turn to and rely on digital interventions.

While social media holds potential for delivering digital health interventions and these seem acceptable to SGM persons, high levels of attrition from these interventions have been reported among the general population (Short et al., 2018). Given this, engagement is a proposed prerequisite for the effectiveness of social media–delivered health interventions because when engagement is low, the intervention will likely fail to change behavior (Pagoto and Waring, 2016; Yardley et al., 2016). Interestingly, assessing the engagement with social media-interventions beyond simply usage had not been emphasized in the research (Welch et al., 2016). This paucity of research around the subject makes it difficult to reach to significant conclusions related to engagement with social media-interventions for the general population, let alone for SGM individuals.

In the context of digital health interventions, engagement has been defined as having two dimensions: micro level engagement, or “the extent (e.g. amount, frequency, duration) of usage” and macro level engagement, or “the depth of user involvement with the behavior change process characterized by attention, interest, and affect” (Perski et al., 2017). Some examples of micro level engagement include number of ‘likes’, count of post views, and frequency and number of user posts or replies to intervention messages (Waring et al., 2018). Meanwhile, certain types of post content produced by intervention participants, such as autobiographical posts (Pagoto et al., 2018), might be an indicator of affective response to intervention components, which are described as macro level engagement. These two dimensions are important to evaluate in social media–delivered interventions because, while good micro level engagement might signal overall engagement with the intervention, macro level engagement seems to be a more valid indicator of engagement with a process of behavioral change (Yardley et al., 2016). More recently, a number of both qualitative and quantitative methods have been proposed for assessing these emotional, cognitive, and behavioral aspects of engagement, including interviews, think aloud methods, focus groups, self-report questionnaires, ecologic commentary assessments, system usage and sensor data, social media data, and psychophysiological measures (Short et al., 2018).

Despite the increasing number of digital health interventions focused on improving health outcomes among SGM people (Gilbey et al., 2020), there is a lack of reviews summarizing whether and how researchers assess this construct. Given the ongoing conversation on building consensus in the area of engagement with digital health interventions, we propose to expand previous research (Gilbey et al., 2020), and the need to expand access to health services to hidden populations such as SGM persons (Kates et al., 2018), we propose to put a specific focus on summarizing the literature in the field of engagement with social media–delivered health interventions for SGM people. Therefore, the objectives of this review were to (1) identify all peer-reviewed published articles that assessed engagement with social media–delivered health intervention for SGM persons, describing study characteristics and quality of study reporting; and (2) describe whether and how engagement metrics were operationalized across studies using the proposed dimensions of micro and macro level engagement.

2. Methods

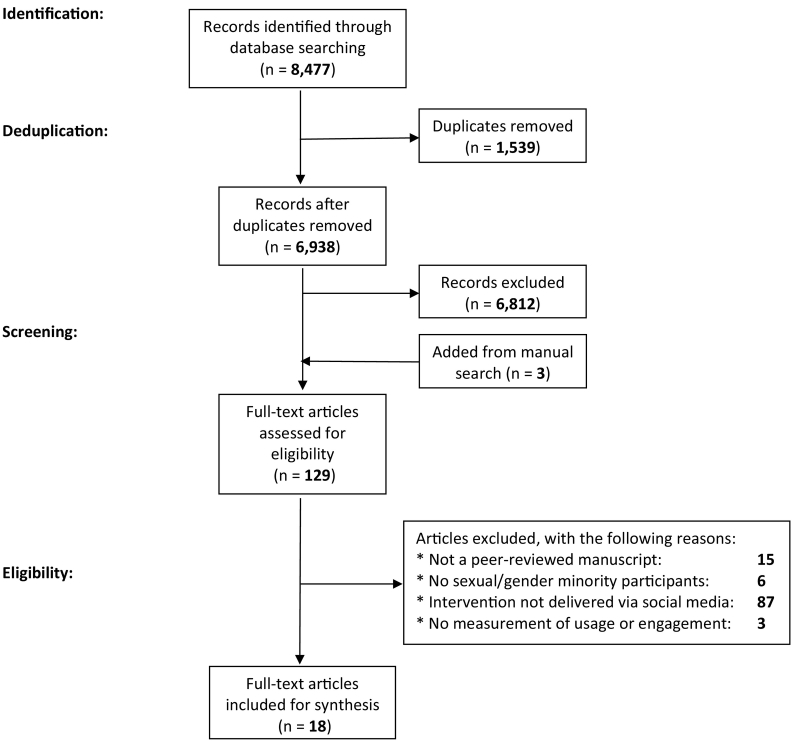

We report this review according to the requirements of the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Statement (PRISMA) (Liberati et al., 2009; Moher et al., 2009) (Appendix 1). We registered the protocol for this review in the PROPERO database (no. CRD4201942189), and we make it available here as a supplement (Appendix 2).

2.1. Inclusion and exclusion criteria

We included peer-reviewed references published in journals of medicine, public health, or social sciences, in English language. On a case-by-case basis, we allowed references from conference proceedings, as long as these conferences required full manuscript submission and peer-review before acceptance. Included manuscripts had to assess the engagement with health interventions delivered through social media and focused on SGM individuals. In the context of this review, social media could include social and professional networking, content production and sharing, online communities, and location-based services (i.e. Facebook, LinkedIn, YouTube, online support groups, Tinder, etc.). Because we aimed to review the findings about engagement with these interventions, we did not set specific health outcomes or conditions as inclusion criteria. Given the heterogeneity in defining engagement, we included papers that reported to assess engagement, and examined their conceptualization of engagement and assessment of it. Finally, we excluded theses, dissertations, and opinion pieces.

2.2. Search process

Literature searches were developed and conducted by a health sciences librarian (RM) using the PubMed, Ovid APA PsycInfo, EBSCOhost SocINDEX, and ACM Guide to Computing Literature databases. Search strings were comprised of natural language and controlled vocabulary representing the concepts of sexual or gender minorities and social media, and were translated for each database. The search strings were adapted in part from searches developed by Charles Wessel (Escobar-Viera et al., 2018). The searches were limited to the publication year 2003 (the year “MySpace,” the first modern social media platform launched) to present (June 2020), and references were downloaded into the EndNote citation management software After importing them into a bibliography managing software, duplicate references were removed (Bramer et al., 2016). We provide the entire list of terms, descriptors, and search strings as a supplement (Appendix 3). We retrieved 8477 citations. Of these, 2453 were from PubMed or MEDLINE, 2829 from PsycINFO, 2250 from SocINDEX, and 945 from ACM. After removing 1539 duplicates, 6938 citations remained for the screening process.

2.3. Study selection and data extraction

We conducted all screening and data extraction procedures using an online platform (Distiller SR, 2020), within which we created structured forms that systematically guided both screening and data extraction processes. Two pairs of reviewers (EMM, DJL, JDG, and AJB) were randomly assigned an equal number of citations. Within each pair, reviewers independently screened all manuscript titles and abstracts to generate a set of references that had some possibility for inclusion. Then, each pair assessed the full text of these references to determine eligibility for inclusion. We achieved substantial interrater reliability (weighted Cohen's kappa, 0.75) (McHugh, 2012). In order to minimize risk of reviewer bias, we held consensus meetings between the coders and the rest of the team (CGEV, DLW, BLR, SP) to resolve differences. These meetings were sufficient to resolve all conflicts, and adjudication procedures were not needed.

Our extraction forms allowed for several categories of data (1) study logistics (author, full title, year of publication, methodology, research design, setting, and funding source); (2) study population characteristics (number of participants, recruitment methods, gender identity, sexual orientation, race, ethnicity, education level, employment status, and income); (3) quality of study reporting; (4) intervention characteristics (social media platforms used, intervention name, study length, theoretical framework, comparison group, and measures of usage/engagement); (5) health outcomes (primary and secondary outcomes, measures used); and (6) results and limitations. During the extraction process, one reviewer of each pair completed a first data extraction and the second reviewer validated or disagreed with it. This procedure helped ensure accuracy of data extracted with disagreements being resolved during team meetings.

2.4. Quality of study reporting

We assessed quality of reporting of all included studies. Given that all studies fit in two categories, we used either the CONSORT extension for pilot and feasibility studies checklist (Eldridge et al., 2016; Thabane et al., 2016) or the main CONSORT statement for parallel group randomized trials checklist (Schulz et al., 2010). For each checklist, we assigned values of zero for each item marked with an ‘X’ and one for items marked with a checkmark. Total scores could range from zero to 40 or from zero to 37, where a score of 40 or 37 means the study fully adhered to the CONSORT guidelines for pilot and feasibility studies or parallel group randomized trials, respectively (Appendix 4, Appendix 5).

3. Results

3.1. Study identification

Of 6938 citations reviewed, we excluded 6812 records after title and abstract screening (Fig. 1). During this step, we identified three potentially relevant references with manual search, and thus included them for full-assessment. Of 129 articles fully assessed for eligibility, we excluded 15 that were not peer-reviewed manuscripts, six that did not have sexual or gender minority participants, 87 studies of interventions not delivered via social media, and three that did not use a measure of usage or engagement with the intervention. We reviewed the list of references for each included manuscript in order to identify additional studies, but no new study that met our inclusion criteria were identified in this manner. Therefore, 18 research manuscripts were included in the final sample.

Fig. 1.

Flowchart of studies screened and included in a 2020 systematic review of engagement with social media−delivered interventions for improving health outcomes among sexual and gender minorities.

3.2. Study characteristics and quality of reporting

Of 18 manuscripts included in this review, 15 reported results of feasibility studies (Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018; Anand et al., 2015; Elliot et al., 2016; Horvath et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2017; Lampkin et al., 2016; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2020; Pedrana et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015; Tanner et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2019a; Washington et al., 2017; Young and Jaganath, 2013; Zhu et al., 2019). Three studies reported results of either efficacy (Bull et al., 2012) or effectiveness trials (Cao et al., 2019; Vogel et al., 2019b). Characteristics of each study are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Characteristics of studies on the engagement of social media−delivered health interventions among sexual and gender minorities.

| Author(s), country, year | Study type, intervention length | Platform or app | Participants |

Reporting quality scorea | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| N | Age range, mean | Race/ethnicity (%) | Cis-women (%) | Sexual identity (%) | Transgender (%) | ||||

|

Zhu et al., 2019 China |

Feasibility and acceptability, 6 months | 100 | 18+, N/R | N/R | 0 | Gay: 78 MSM: 100 |

0 | 27/40 | |

|

Vogel et al., 2019a, Vogel et al., 2019b USAb |

Feasibility and acceptability, 30 days | 27 | 18–25, 19.7 | White: 74.1 Black: 14.8 Asian: 3.7 Hawaiian or Pacific Islander: 3.7 Alaskan or Native American: 7.4 Hispanic/Latino: 14.8 Arab, non-White: 3.7 |

40.7 | Gay or lesbian: 22.2 Bisexual: 56.6 Queer: 7.4 Pansexual: 29.6 |

7.4 | 24/40 | |

|

Cao et al., 2019 China |

Effectiveness trial, 1 year | 1033 | 16+, 25.3 | N/R | 0 | Gay: 72 MSM: 100 |

0 | 22/37 | |

|

Vogel et al., 2019a, Vogel et al., 2019b USAb |

Effectiveness trial, 1 year | 500 | 18–25, N/R | White: 73.8 Black: 2.6 Alaskan or Native American: 1.0 Asian or Pacific Islander: 1.2 Hispanic/Latino: 6.9 Multiple races: 14.5 |

54.6 | SGM: 27 | 0.6 | 17/37 | |

|

Washington et al., 2017 USA |

Feasibility and acceptability, 6 weeks | 42 | 18–30, 23 | Black: 100 | 0 | MSM: 100 | N/R | 15/40 | |

|

Anand et al., 2015 Thailand |

Feasibility and acceptability, 40 months | Adam's Love | 1181 | 14+, N/R | N/R | 0 | Gay or MSM: 92.3 Bisexual: 6.1 |

1.6 | 15/40 |

|

Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015 USA |

Feasibility and acceptability, 3 months | 41 | 18–29, 25.2 | White: 53.7 Black: 17.1 Hispanic/Latino: 22.0 Other: 7.3 |

0 | Gay: 85.4 Bisexual: 12.2 Uncertain: 2.4 MSM: 100 |

N/R | 20/40 | |

|

Horvath et al., 2013 USAc |

Feasibility and acceptability, 8 weeks | Thrive With Me | 123 | 18+, 42.7 | White: 64.2 Black: 33.3 Multi-ethnic/other: 2.4 Hispanic: 9.8 |

0 | MSM: 100 | 0 | 22/40 |

|

Pedrana et al., 2013 Australia |

Feasibility and acceptability, 12 months | Facebook, YouTube | N/R | 13+, N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | N/R | 16/40 |

|

Young & Jaganath, 2013 USA |

Feasibility and acceptability, 12 weeks | 57 | 18+, 31.2 | White: 8.8 Black: 29.8 Asian: 1.8 Hispanic/Latino: 59.7 |

N/R | Gay: 73.7 Bisexual: 17.5 Heterosexual/ questioning/ don't know: 8.8 MSM: 100 |

N/R | 20/40 | |

|

Bull et al., 2012 USA |

Efficacy trial, 8 weeks | 1578 | 16–25, 20 | White: 30.1 Black: 34.9 Asian: 19.4 Hawaiian or Pacific Islander: 0.8 Alaskan or Native American: 0.8 Hispanic/Latino: 13.7 Other: 10.5 |

N/R | N/R | N/R | 22/37 | |

|

Patel et al., 2020 India |

Feasibility and acceptability, 12 weeks | 244 | 18+, N/R | N/R | 0 | Gay, homosexual, or queer: 71.7 Bisexual: 25.8 Straight or heterosexual: 3.3 MSM: 100 |

N/R | 19/40 | |

|

Tanner et al., 2018 USA |

Feasibility and acceptability, 12 months | Facebook, GPS-based mobile apps (A4A/Radar, badoo, Grindr, Jack'd, SCRUFF) | 91 | 16–34, 25 | White: 1.1 Black: 79.1 Hispanic/Latino: 13.2 Multi-racial: 6.6 |

0 | MSM: 100 | N/R | 23/40 |

|

Elliot et al., 2016 UK |

Feasibility and acceptability, 24 months | Gaydar, Grindr, Recon, and Facebook | 321 | N/R, 34.5 | N/R | 0 | MSM: 100 | N/R | 16/40 |

|

Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018 Spaind |

Feasibility and acceptability, 4 months | Grindr, PlanetRomeo, and Wapo | 2656 | 18+, N/R | N/R | 0 | MSM: 100 | N/R | 16/40 |

|

Huang et al., 2017 USA |

Feasibility and acceptability, 1 month | Dating/Hook-up App | 122 | 18+, N/R | Black: 14 Hispanic/Latino: 86 |

0 | MSM: 100 | N/R | 16/40 |

|

Lampkin et al., 2016 USAb |

Feasibility and acceptability, 1 year | Grindr | 816 | 18+, N/R | White: 26.3 Black: 2.5 Asian: 8.3 Hispanic/Latino: 17.9 Mixed/other: 9.9 Not reported: 35 |

0 | MSM: 100 | N/R | 16/40 |

|

Sun et al., 2015 USA |

Feasibility and acceptability, 6 months | A4A Radar, Grindr, Jack'd, and Scruff | N/R | N/R, N/R | N/R | N/R | MSM: 100 | N/R | 21/40 |

N/R: not reported.

Assessed using CONSORT 2010 main statement (37 possible points) and extension to randomized pilot and feasibility trials (40 possible points).

Demographic assessment allowed participants to select multiple responses and therefore, percentages may not add up to 100.

Race/ethnicity variables were reported with different categories from the ones reported in this review, therefore, percentages may not add up to 100.

Sexual orientation was reported for only 79 study participants, as opposed to the entire sample of 2656 persons.

Eleven studies were conducted in the USA, two in China, and one in Thailand, Australia, India, UK, and Spain, respectively. Social media sites used to deliver the interventions varied across studies. Eleven studies (Anand et al., 2015; Bull et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2019; Horvath et al., 2013; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2020; Vogel et al., 2019a; Vogel et al., 2019b; Washington et al., 2017; Young and Jaganath, 2013; Zhu et al., 2019) delivered their interventions using a single social media site (Facebook, WeChat, Adam's Love, Thrive with Me). Four studies (Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018; Huang et al., 2017; Lampkin et al., 2016; Sun et al., 2015) leveraged location-based social media apps for intervention delivery (Grindr, Planet Romeo, Wapo, A4A Radar, Jack'd, Scruff), and three other studies (Elliot et al., 2016; Pedrana et al., 2013; Tanner et al., 2018) used a combination of social media sites and location-based apps to do so (Facebook, YouTube, Badoo, Gaydar, A4A Radar, Grindr, Jack'd, Scruff, Recon). Feasibility studies had an average duration of 8.7 months (range 1–40 months). Both effectiveness trials had a duration of 12 months, and the only efficacy trial included had a duration of two months.

Participant demographic characteristics varied greatly across studies. Among studies that reported mean age of participants (Bull et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2019; Elliot et al., 2016; Horvath et al., 2013; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015; Tanner et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2019a; Washington et al., 2017; Young and Jaganath, 2013), mean age was 27.1 years (range 16–34). Only three studies (Anand et al., 2015; Vogel et al., 2019a; Vogel et al., 2019b) recruited participants who identified as either cisgender women or transgender. Of 15 feasibility studies, 13 recruited samples of men who have sex with men (MSM), with sexual orientation comprising mainly gay men. One study (Vogel et al., 2019a) included participants with diverse sexual identity, and another (Pedrana et al., 2013) did not report participants' sexual identity. Among the three effectiveness or efficacy trials, one (Cao et al., 2019) recruited MSM only, another (Vogel et al., 2019b) reported sexual and gender minority participants as a single group, and one study (Bull et al., 2012) did not report participants' sexual identity.

The quality of reporting was variable across the included manuscripts. Among 15 feasibility studies, CONSORT scores (Eldridge et al., 2016) ranged from 14 to 26 out of 40 possible points; 8/15 studies met reporting standards on their title, 14/15 did so on the Introduction section, 0/15 met the reporting standards in the Methods and Results sections, and 4/15 did so on the Discussion section. Only 2/15 studies met reporting standards regarding funding sources, ethical approval, pilot trial protocol, and registration number. Among three effectiveness or efficacy trials, CONSORT scores (Schulz et al., 2010) were 22 (Cao et al., 2019), 17 (Vogel et al., 2019b), and 22 (Bull et al., 2012) out of 37 possible points; 2/3 studies met reporting standards in their title and Introduction sections, 0/3 did on the methods, results and discussion reporting, and 1/3 met standards reporting trial registration, protocol availability, and funding sources.

3.3. Intervention characteristics

Characteristics of social media−delivered interventions evaluated in each included study are summarized in Table 2. A total of 17 interventions were evaluated across 18 articles. The vast majority of papers evaluated interventions related to HIV care: sexual health promotion (Pedrana et al., 2013), HIV testing (Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018; Cao et al., 2019; Elliot et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2017; Patel et al., 2020; Sun et al., 2015; Washington et al., 2017; Young and Jaganath, 2013; Zhu et al., 2019), condomless sex (Bull et al., 2012; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015), linkage to services (Anand et al., 2015; Lampkin et al., 2016), and treatment adherence (Horvath et al., 2013; Tanner et al., 2018). Two articles (Vogel et al., 2019a; Vogel et al., 2019b) evaluated different aspects of the same smoking cessation intervention.

Table 2.

Characteristics of social media−delivered interventions for improving health outcomes among sexual and gender minorities.

| Author(s), country, year | Health-related outcomes | Brief intervention description | Comparator condition | Engagement indicators | Other feasibility indicators | Main findings |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

Zhu et al., 2019 China |

HIV testing | Participants received two oral HIV test kits. The intervention group had access to a WeChat group which provided messages and health referrals. | Participants without WeChat group access | Number of messages read on WeTest | HIV test self-reports | Engagement: 12 of 79 messages were read by >50% of participants. 5% of participants unfollowed WeTest group during follow-up. HIV testing: intervention group had higher rates of oral HIV testing |

|

Vogel et al., 2019a, Vogel et al., 2019b USA |

Smoking cessation | Participants saw smoking cessation posts tailored towards SGM populations in private Facebook groups. | Non-SGM-tailored Facebook posts in private groups. | Quantity and content of FB comments, number of posts viewed per participant, comments per participant | Comments flagging posts for content | Engagement and acceptability: majority of participants perceived intervention positively, commented on posts, and viewed most content |

|

Cao et al., 2019 China |

HIV testing | Images, texts, and other resources promoting HIV testing were shared on WeChat. | Within and between groups | Survey measuring recall seeing, sharing, and participating in creating a message | N/A | Engagement: 91.4% of participants recalled images or text, 67.1% shared these materials, 34.5% participated in activities HIV testing: 19.9% of men reported getting an HIV test during the intervention period. Increased engagement is associated with increased odds of HIV testing |

|

Vogel et al., 2019a, Vogel et al., 2019b USA |

Smoking cessation | Participants were part of a private Facebook group, based on their motivation to quit smoking, in which there were posts and live, online counseling sessions. | Participants were referred to smokefree.gov | Number of Facebook comments during the 90-day intervention | Usability: perception of intervention | Smoking cessation: was not significantly different between SGM and non-SGM participants; at 12-month follow-up SGM participants were at higher risk of physical inactivity Engagement: no significant difference in number of comments posted between SGM and non-SGM participants |

|

Washington et al., 2017 USA |

HIV testing | Participants were part of a Facebook page on which they viewed videos promoting Black MSM to get HIV testing and commented on these videos. | Participants were part of a Facebook page where they read standard HIV information and commented on the content | Attrition rate | N/A | Attrition rate: similar in intervention (28.6%) and control (21.4%) group, respectively HIV testing: intervention group had increased odds of having had an HIV test; the intervention group had significantly greater HIV knowledge after the intervention |

|

Anand et al., 2015 Thailand |

Referral for HIV testing, counseling, and treatment | Adam's Love club membership provided comprehensive HIV prevention information and resources, social media, message boards, online counseling, recruitment, appointment making, entertainment, fashion, photography, and YouTube videos. | N/A | Analytic tools from Google, YouTube, and Facebooka | Analysis of questions asked on Adam's Love and those counseled; number of referrals made to HIV and STI screenings | Engagement: Adam's Love attracted 1.69 million viewers, had 8 million page views, average 4.6 min per visitor Feasibility: 11,120 gay, MSM, or bisexual men received online counseling. Online-to-offline recruitment was able to successfully promote MSM HIV testing, HIV counseling, and referral to treatment |

|

Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015 USA |

Condomless anal sex; Substance use | Participants were part of up to 8 Facebook live chats which incorporated motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral skills-based sessions. | N/A | Session attendance | Qualitative assessment of experiences with the intervention | Engagement: 75.6% of participants attended at least one of eight intervention sessions. Of these, 61% attended the minimum dose of 5 sessions Feasibility: positive overall sentiment about the intervention Condomless anal sex: intervention was associated with decrease in HIV risk behaviors |

|

Horvath et al., 2013 USA |

Anti-retroviral therapy adherence | TWM website with asynchronous discussion/messaging board, medication adherence page, and info about living with HIV | Participants were not asked to participate in any TWM activities. They received one interim e-mail reminding them of a follow-up survey. | Logging into intervention website, writing or responding to posts, updating their medication adherence graph, and viewing content | Recruitment and retention Follow-up completion Participants rated (1–7 scale) the intervention for information, satisfaction, and system quality |

Engagement: 58% of intervention group used 100 or more intervention components. Feasibility: 90.2% retention at 1-month follow-up. Acceptability and satisfaction: overall moderate to high Anti-retroviral therapy adherence: modest overall effects |

|

Pedrana et al., 2013 Australia |

Sexual health promotion | 3 series of online drama webisodes delivering sexual health promotion information via Facebook and YouTube | N/A | Online usage statisticsb, qualitative diary, focus groups | Perceived utility of the intervention | Engagement: by the end of series 1, Facebook page received 6105 unique page views, 2642 individual video views, and 526 page interactions, including 281 likes, 205 comments, and 40 wall posts. The YouTube channel received 7297 video views by the end of Series 1, along with the 79 subscriptions to the channel and 36 likes. |

| Young et al., 2013 USA |

HIV testing | Peer leaders, trained in HIV prevention, posted HIV-related content in secret Facebook groups. Participants had ability to discuss among community. | Participants received peer-led general health information on Facebook. | Participant conversation (initiated posts, replies, or “likes”) in the Facebook groups | N/A | Engagement: participants engaged in 458 conversations. HIV testing: participants who posted about HIV prevention and tested had a higher likelihood of requesting an HIV testing kit |

|

Bull et al., 2012 USA |

Condomless sex | Participants were part of a Facebook page providing sexual Health and STI/HIV prevention messages. | Participants were assigned to a Facebook page providing current events. | Visitors per week, time spent on FB; page posting; participant retention | N/A | Engagement: average of 43 unique visitors per week (range 37–101), average time spent on Facebook page 3.2 min (range 1–7.3 min) Condomless sex: those who engaged with intervention more likely to have used a condom at their last sex at the 2-month follow-up |

|

Patel et al., 2020 India |

HIV testing; consistent condom use | Internet-based, peer-led messaging intervention (using e-mail, Facebook private group, or WhatsApp). Intervention included motivational and educational messages in either an approach or avoidance frame. | N/A | Number of messages viewed and response to emails | Retention (composite number of messages viewed and response to emails) Satisfaction with intervention |

Feasibility: 82% of participants were retained. Satisfaction: 81.5% of participants liked or strongly liked the intervention HIV testing: there was an increase in self-reported HIV testing and intention to test |

|

Tanner et al., 2018 USA |

Viral load suppression; Clinic appointment attendance | Participants received text messages, Facebook messages, and app-based messages promoting linkage and retention in HIV care | N/A | Number of interactions or messages with health educator | N/A | Engagement: each participant had on average 41.3 conversations with the health educator Health outcomes: significant decrease in missed HIV clinic appointments and a significant increase in HIV viral load suppression |

|

Elliot et al., 2016 UK |

HIV testing | Online users were offered to assess their HIV risk through messages on social media. They were also offered free HIV tests. | Compared those diagnosed through DSH and those in the London Clinic (HIV) | Click through rates, visiting website, risk assessment survey completion, sample kit order | Acceptability survey | Engagement: 11,127 clicks through for more information on test. Of these, 93% also ordered a sampling kit. |

|

Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018 Spain |

HIV testing; STI testing | Participants received private, personal messages on apps for sexual and social encounters offering rapid HIV and STI tests and HepA and B vaccines. | N/A | Response rate | Acceptability: rate of favorable responses. Feasibility: investigators profile remained active for more than 1 week |

Engagement: 38.4% response rate to messages. Acceptability: 83.0% of favorable responses. Feasibility: investigators' profiles remained active throughout the study |

|

Huang et al., 2017 USA |

HIV testing | Participants using Grindr were exposed to an advertisement for free HIV self-tests and then redirected to a website to order a test. | N/A | Website visitors Self-test requests (click-through rate) |

Testing-experience survey measuring ease of use | Engagement: website received 11,939 unique visitors. Of these, 334 (2.8%) clicked through and requested a test |

|

Lampkin et al., 2016 USA |

Linkage to HIV/STI care | MSM users on Grindr could interact with a health educator, who identified themselves as such and provided a linkage to HIV/STI care and information. | N/A | Users' continued chat with health educator | Reach of intervention | Acceptability: 168/213 (78.8%) and 562/816 (68.9%) of those who reached out to the health educator remained engaged (i.e., kept chatting) in phases 1 and 2, respectively. |

|

Sun et al., 2015 USA |

HIV testing; STI testing | A trained health educator promoted HIV testing in 4 apps designed for MSM. Participants voluntarily interacted with the health educator. | N/A | Interaction with health educator; number of exchanges with health educator | Intervention acceptability | Engagement: 2709 interactions were logged in six months. Number of exchanges significantly different across apps. Acceptability: 63.8% of users found the intervention to be an acceptable source of sexual health information |

N/R: not reported.

Analytic tools included: Google (total visitors, page views, visit duration, user demographics, search engines and search keywords), YouTube (lifetime views, traffic sources and devices used) and Facebook (page fans, fan demographics, people reached and page message).

Facebook: unique page views, active use, photo views, and total interactions (wall posts, comments, “likes” per day). YouTube: data included cumulative number of video views, demographics, and traffic sources, which described where users accessed the YouTube channel from.

All but one of the examined interventions consisted of exposing participants to informational and or educational content (via message boards, posts, ads, and private or group chats) about the health-related outcome of interest. One (Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015) of the interventions coupled this educational information with the delivering of motivational interviewing and cognitive behavioral skills-based sessions. Interventions allowed interactions with health-related content only (Cao et al., 2019; Elliot et al., 2016; Huang et al., 2017; Pedrana et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2019a), with peers only (Patel et al., 2020; Washington et al., 2017), with health educators only (Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018; Lampkin et al., 2016; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015; Sun et al., 2015; Tanner et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2019b; Zhu et al., 2019), or both peers and health educators (Anand et al., 2015; Bull et al., 2012; Horvath et al., 2013; Young and Jaganath, 2013). In 9/18 articles (Cao et al., 2019; Elliot et al., 2016; Horvath et al., 2013; Jacobs and Kane, 2012; Vogel et al., 2019a; Vogel et al., 2019b; Washington et al., 2017; Young and Jaganath, 2013; Zhu et al., 2019), study design included some form of comparator condition.

3.4. Engagement

All 18 studies included in this review used at least one measure of micro level engagement. However, measures of engagement varied widely across studies. Ten studies (Anand et al., 2015; Bull et al., 2012; Elliot et al., 2016; Horvath et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2017; Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015; Patel et al., 2020; Pedrana et al., 2013; Vogel et al., 2019a; Zhu et al., 2019) used social media data for frequency counts of views, reads, or logins of the intervention materials or social media site. Ten studies (Bull et al., 2012; Horvath et al., 2013; Lampkin et al., 2016; Patel et al., 2020; Pedrana et al., 2013; Sun et al., 2015; Tanner et al., 2018; Vogel et al., 2019a; Vogel et al., 2019b; Young and Jaganath, 2013) leveraged this data to assess quantity and quality of user responses to intervention prompts, emails, or other users' comments.

Moreover, three articles (Alarcón Gutiérrez et al., 2018; Bull et al., 2012; Washington et al., 2017) reported intervention attrition rates as an indicator of engagement. One study (Cao et al., 2019) assessed self-report of view counts and user responses to intervention messages. Additionally, two articles (Lelutiu-Weinberger et al., 2015; Pedrana et al., 2013) utilized qualitative assessments to learn about usability of and user experience with the intervention. Finally, three articles (Elliot et al., 2016; Horvath et al., 2013; Huang et al., 2017) assessed number of intervention activities completed by the user.

4. Discussion

4.1. Summary of evidence

In this systematic review, we found a low number of peer-reviewed articles examining social media–delivered interventions to improve health outcomes among SGM people. We found variation in the quality of data reporting across articles, with almost all interventions focused on improving HIV-related outcomes among cisgender MSM. Importantly, we found an important variation in how studies assessed engagement, with measures focused mostly on micro level engagement. We discuss the implications of these findings below and provide suggestions for future research.

We used a comprehensive set of inclusion criteria for this review. For example, we included articles from studies conducted on social media apps more commonly thought of as dating/hook-up apps. Even so, we found few studies that evaluated social media–delivered health interventions focused on SGM persons; 15 articles reported results of feasibility studies, and 3 were either efficacy or effectiveness trials. A large majority of these studies was conducted in developed countries only within the last five years. Given the ubiquitous use of social media among SGM people (Anderson and Jiang, 2018; Nesi et al., 2018) and the high acceptability of digital health interventions among this group (Gilbey et al., 2020), social media holds potential as a delivery modality for behavioral interventions targeting these minority groups. As the world struggles with a viral pandemic which forces us to consider social distancing measures, digital health interventions may be viable interventions to ensure individuals' safety and privacy. To do this, well-designed and well-conducted feasibility trials, preferably with comparator conditions, will provide stronger evidence regarding engagement, and potential effectiveness of these interventions.

Quality of data reporting was variable across the included studies. Most of the variability was due to incomplete reporting of the Methods and Results sections, such as changes made to the assessments after pilot study commenced, rationale for sample size, explanation of interim analyses, method used to generate and to implement random allocation, reasons for dropouts, or harms or unintended effects in each group. The variation we found in the reporting might be explained in part by the fact of relatively recent consensus around reporting standards (Eldridge et al., 2016) and how to structure feasibility trials (O'Cathain et al., 2015; Tickle-Degnen, 2013) in order to generate evidence that can be used to plan and design efficacy or effectiveness trials. It is likely that researchers, publishers, and funding agencies will continue to incorporate these relatively recent elements to the common practice of future research.

In most studies included in this review, participants were between 18 and 30 years of age. While social media use was previously most common among teens (Anderson and Jiang, 2018), usage has been growing among adults under (Drouin et al., 2020; Perrin and Anderson, 2019) and over 65 years of age (Nimrod, 2020), especially during the COVID-19 pandemic, to address anxiety, loneliness, and other mental health concerns. Given the current events around the world, increased social media use has been linked to enhanced quality of life among older adults (Wallinheimo and Evans, 2021). This increased usage combined with the motivation for using social media among older adults (Jung and Sundar, 2020) highlights the opportunity to expand intervention research into this particular age group.

The vast majority of articles included focused on improving HIV-related outcomes with samples comprised of men who have sex with men (MSM). Most intervention research over the last decade has focused on reducing disparities related to HIV and other sexually transmitted infections among MSM (Baptiste-Roberts et al., 2017). The lack of diversity in both sexual and gender identity among these samples makes it difficult, if not impossible, to generalize our findings about engagement with social media interventions to larger groups of SGM people. Therefore, further intensive work is needed to increase our understanding of how different groups of SGM persons engage with digital health interventions in order to meet their specific needs of health information and identity representation. Given that some of these SGM groups are more hidden than others in our communities, this research will require more purposeful incorporation of more SGM people in the entire process of developing, usability testing, feasibility evaluation, and effectiveness testing of social media-delivered other digital health interventions.

However, assessments among SGM people found important disparities and unmet needs for depression (Becerra-Culqui et al., 2018; Marshal et al., 2011), alcohol and substance use (Boyd et al., 2019), tobacco use (Jamal et al., 2018), obesity and eating disorders (Azagba et al., 2019), some types of cancer (Valanis et al., 2000), and heart disease (Caceres et al., 2020). These disparities are even greater in SGM communities of color (Bostwick et al., 2014) and SGM communities living in rural settings (Rosenkrantz et al., 2017; Willging et al., 2006). Moreover, only three articles reported recruitment of sexual minority cisgender women and/or transgender persons. The lack of inclusion of these groups limits the ability to determine the efficacy of these types of interventions for sexual minority cisgender women and transgender persons. Given the specific health disparities and barriers to access care for subgroups of SGM people (Hafeez et al., 2017; Safer et al., 2016), future intervention research that leverages social media should be conducted with these groups specifically to explore how digital health interventions might address the unmet needs and health disparities for sexual minority cisgender women and transgender persons.

We also found some variation regarding which social media platform was used to deliver interventions. Although the vast majority of studies were conducted on commercially available platforms (e.g., YouTube, dating apps), two studies leveraged platforms specifically developed for the research. This finding highlights a growing preference of both participants and researchers for commercially available platforms that do not require additional learning effort for the participant, a very-well known principle in community-based interventions of “meeting people where they already are.” Additionally, while most interventions were delivered via Facebook, a sizeable minority of interventions were delivered on either via alternative social media platforms (e.g., YouTube) or via location-based social media apps (i.e., dating apps). This highlights the importance of having a human-centered approach (Moore and Arar, 2018) for the designing, developing, and testing of more engaging social media interventions, focused not only on platform popularity but also on users' goals, preferences, and motivations for use.

While the lack of consensus on what constitutes engagement for digital interventions, as well as the dimensions and measures to best assess it, makes it a difficult task to summarize our findings regarding engagement. However, a key finding of this review that complements and expands previous research on a similar topic (Gilbey et al., 2020), is that the most frequently employed engagement metrics were number of views, number of comments on intervention posts, attrition rates, and online usage statistics provided by each social media platform. Only two studies utilized qualitative assessments to explore usability and user experience, but not macro level engagement (Short et al., 2018). These metrics speak to the extent to which the user has observed or interacted with an intervention. In other words, these are indicators of micro level engagement (Short et al., 2018), which provides information on behavioral engagement with the intervention but less so about macro level engagement, or the user's cognitive and emotional investment with the behavior change process. Given the importance of developing interventions that mediate positive outcomes via effective engagement (which may or may not require sustained engagement) (Yardley et al., 2016), further consideration must be paid to evaluating both micro and macro level engagement of future social media–delivered interventions.

Advancing the science of social media–delivered interventions will require complementary approaches to assessment of engagement that include both micro and macro level factors (Pagoto et al., 2019). Leveraging mixed methods (i.e., collecting and integrating quantitative and qualitative data) can dramatically expand the findings related to aspects of macro level engagement compared to what either type of data separately might be able to tell (Fetters et al., 2013). For instance, researchers might want to conduct thematic analysis of user feedback collected at the same time that intervention messages are delivered on social media along with frequency count of message views. By doing this, it might be possible to suggest potential relationships between emotional responses to intervention messages with number of views, as well as potential cognitive or emotional gains from intervention messages. This might prove critically important for interventions focused on minority groups, especially SGM persons. Furthermore, it is critical to determine how the intersectional identities of SGM persons (e.g., race, ethnicity, social class, religion, etc.) might impact the types of intervention messages which may be most effective.

4.2. Limitations

Our work is not without some limitations. First, the low number of studies included in this review along with the variation in definition and measurement of engagement across studies and the limited sample of categories of SGM other than MSM, limited our ability to generalize our findings to interventions targeting diverse groups of SGM. Second, by limiting our results to research published in English language, we might have missed relevant research published in other languages. Thirdly, there was a prominence of interventions addressing HIV disparities, but limited interventions in other areas. Finally, we found a noticeable heterogeneity in outcome measures, study duration, and study protocol. Therefore, a meta-analysis was not possible. Notwithstanding these limitations, we utilized a comprehensive set of inclusion criteria along with four large online databases, which largely covered the scope of the research conducted on social media–delivered interventions for improving health outcomes among SGM individuals.

5. Conclusion

There is a growing interest among researchers for developing and testing effective digital health interventions for SGM persons. Digital health interventions are acceptable to SGM individuals, hold potential for cost-effectiveness, and might be able to reduce barriers to access of healthcare for SGM people, otherwise consistently reported in the extant research. Our findings support the need for this research, with a focus on social media–delivered interventions for improving mental and physical health outcomes. The objective of this review was to identify and describe the evaluation of engagement with social media–delivered interventions for improving health outcomes among SGM persons. In addition to the heterogeneity in defining and assessing engagement, we found a focus on measures of intervention usage with room for future research to improve evaluation of cognitive and emotional aspects of engagement in order to develop effective and tailored digital health interventions for sexual and gender minorities.

The following are the supplementary data related to this article.

PRISMA checklist.

PROSPERO Registration Form and Approval.

Online search strategy.

Evaluation of accurate reporting of studies Included using criteria from the CONSORT extension for pilot and feasibility trials.

Evaluation of accurate reporting of studies included using criteria from the CONSORT extension for randomized trials.

Funding

We gratefully acknowledge funding from NIMHD (grant number R00 - MD012813) and NIMH (grant number P50 - MH115838) for the completion of this research. Funding sources played no role in the study design; collection, analysis, and interpretation of data; writing of the report; or decision to submit the article for publication.

Declaration of competing interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Alarcón Gutiérrez M., Fernández Quevedo M., Martín Valle S., Jacques-Aviñó C., Díez David E., Caylà J.A., García De Olalla P. Acceptability and effectiveness of using mobile applications to promote HIV and other STI testing among men who have sex with men in Barcelona, Spain. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2018;94(6):443–448. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2017-053348. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Guidelines for psychological practice with lesbian, gay, and bisexual clients. Am. Psychol. 2012;67(1):10–42. doi: 10.1037/a0024659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American Psychological Association Guidelines for psychological practice with transgender and gender nonconforming people. Am. Psychol. 2015;70(9):832–864. doi: 10.1037/a0039906. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anand T., Nitpolprasert C., Ananworanich J., Pakam C., Nonenoy S., Jantarapakde J., Sohn A.H., Phanuphak P., Phanuphak N. Innovative strategies using communications technologies to engage gay men and other men who have sex with men into early HIV testing and treatment in Thailand. J. Virus Erad. 2015;1(2):111–115. doi: 10.1016/S2055-6640(20)30483-0. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/27482400%0Ahttp://www.pubmedcentral.nih.gov/articlerender.fcgi?artid=PMC4946676 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson M., Jiang J. Pew Research Center; 2018. Teens, Social Media & Technology 2018.http://www.pewinternet.org/2018/05/31/teens-social-media-technology-2018/ [Google Scholar]

- Ayhan C.H.B., Bilgin H., Uluman O.T., Sukut O., Yilmaz S., Buzlu S. A systematic review of the discrimination against sexual and gender minority in health care settings. Int. J. Health Serv. 2020;50(1):44–61. doi: 10.1177/0020731419885093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Azagba S., Shan L., Latham K. Overweight and obesity among sexual minority adults in the United States. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2019;16(10) doi: 10.3390/ijerph16101828. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baptiste-Roberts K., Oranuba E., Werts N., Edwards L.V. Obstetrics and Gynecology Clinics of North America. vol. 44. W.B. Saunders; 2017. Addressing health care disparities among sexual minorities; pp. 71–80. Issue 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Becerra-Culqui T.A., Liu Y., Nash R., Cromwell L., Flanders W.D., Getahun D., Giammattei S.V., Hunkeler E.M., Lash T.L., Millman A., Quinn V.P., Robinson B., Roblin D., Sandberg D.E., Silverberg M.J., Tangpricha V., Goodman M. Mental health of transgender and gender nonconforming youth compared with their peers. Pediatrics. 2018;141(5) doi: 10.1542/peds.2017-3845. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bostwick W.B., Boyd C.J., Hughes T.L., West B.T., McCabe S.E. Discrimination and mental health among lesbian, gay, and bisexual adults in the United States. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2014;84(1):35–45. doi: 10.1037/h0098851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Boyd C.J., Veliz P.T., Stephenson R., Hughes T.L., McCabe S.E. Severity of alcohol, tobacco, and drug use disorders among sexual minority individuals and their “not sure” counterparts. LGBT Health. 2019;6(1):15–22. doi: 10.1089/lgbt.2018.0122. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bramer W.M., Giustini D., De Jong G.B., Holland L., Bekhuis T. De-duplication of database search results for systematic reviews in endnote. J. Med. Libr. Assoc. 2016;104(3):240–243. doi: 10.3163/1536-5050.104.3.014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bull S.S., Levine D.K., Black S.R., Schmiege S.J., Santelli J. Social media-delivered sexual health intervention: a cluster randomized controlled trial. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2012;43(5):467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2012.07.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caceres B.A., Streed C.G., Corliss H.L., Lloyd-Jones D.M., Matthews P.A., Mukherjee M., Poteat T., Rosendale N., Ross L.M. Assessing and addressing cardiovascular health in LGBTQ adults: a scientific statement from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;142(19):e321–e332. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao B., Saha P.T., Leuba S.I., Lu H., Tang W., Wu D., Ong J., Liu C., Fu R., Wei C., Tucker J.D. Recalling, sharing and participating in a social media intervention promoting HIV testing: a longitudinal analysis of HIV testing among MSM in China. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(5):1240–1249. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02392-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cochat Costa Rodrigues M.C., Leite F., Queirós M. Sexual minorities: the terminology. Eur. Psychiatry. 2017;41(S1):s848. doi: 10.1016/j.eurpsy.2017.01.1680. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- DeHaan S., Kuper L.E., Magee J.C., Bigelow L., Mustanski B.S. The interplay between online and offline explorations of identity, relationships, and sex: a mixed-methods study with LGBT youth. J. Sex Res. 2013;50(5):421–434. doi: 10.1080/00224499.2012.661489. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Distiller SR Evidence Partners. 2020. https://www.evidencepartners.com/products/distillersr-systematic-review-software/

- Drouin M., McDaniel B.T., Pater J., Toscos T. How parents and their children used social media and technology at the beginning of the COVID-19 pandemic and associations with anxiety. Cyberpsychol. Behav. Soc. Netw. 2020;23(11):727–736. doi: 10.1089/cyber.2020.0284. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Eldridge S.M., Chan C.L., Campbell M.J., Bond C.M., Hopewell S., Thabane L., Lancaster G.A., O'Cathain A., Altman D., Bretz F., Campbell M., Cobo E., Craig P., Davidson P., Groves T., Gumedze F., Hewison J., Hirst A., Hoddinott P.…Tugwell P. CONSORT 2010 statement: extension to randomised pilot and feasibility trials. Pilot Feasib. Stud. 2016;2(1) doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0105-8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elliot E., Rossi M., Mccormack S., Mcowan A. Identifying undiagnosed HIV in men who have sex with men (MSM) by offering HIV home sampling via online gay social media: a service evaluation. Sex. Transm. Infect. 2016;92(6):470–473. doi: 10.1136/sextrans-2015-052090. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Escobar-Viera C.G., Whitfield D.L., Wessel C.B., Shensa A., Sidani J.E., Brown A.L., Chandler C.J., Hoffman B.L., Marshal M.P., Primack B.A. For better or for worse? A systematic review of the evidence on social media use and depression among lesbian, gay, and bisexual minorities. JMIR Mental Health. 2018;5(3) doi: 10.2196/10496. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fetters M.D., Curry L.A., Creswell J.W. Achieving integration in mixed methods designs - principles and practices. Health Serv. Res. 2013;48(6 PART2):2134–2156. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gilbey D., Morgan H., Lin A., Perry Y. Effectiveness, acceptability, and feasibility of digital health interventions for LGBTIQ+ young people: systematic review. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020;22(12) doi: 10.2196/20158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hafeez H., Zeshan M., Tahir M.A., Jahan N., Naveed S. Health care disparities among lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender youth: a literature review. Cureus. 2017;9(4) doi: 10.7759/cureus.1184. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper G.W., Serrano P.A., Bruce D., Bauermeister J.A. The Internet’s multiple roles in facilitating the sexual orientation identity development of gay and bisexual male adolescents. Am. J. Mens Health. 2016;10(5):359–376. doi: 10.1177/1557988314566227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Horvath K.J., Michael Oakes J., Simon Rosser B.R., Danilenko G., Vezina H., Rivet Amico K., Williams M.L., Simoni J. Feasibility, acceptability and preliminary efficacy of an online peer-to-peer social support ART adherence intervention. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(6):2031–2044. doi: 10.1007/s10461-013-0469-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huang E., Marlin R.W., Young S.D., Medline A., Klausner J.D. Using Grindr, a smartphone social networking application, to increase HIV self-testing among Black and Latino men who have sex with men in Los Angeles, 2014. 2017;28(4):341–350. doi: 10.1521/aeap.2016.28.4.341. (Using) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacobs R.J., Kane M.N. Correlates of loneliness in midlife and older gay and bisexual men. J. Gay Lesbian Soc. Serv. Quarterly J. Commun. Clin. Pract. 2012;24(1):40–61. http://ovidsp.ovid.com/ovidweb.cgi?T=JS&PAGE=reference&D=psyc9&NEWS=N&AN=2012-03323-003 [Google Scholar]

- Jamal A., Phillips E., Gentzke A.S., Homa D.M., Babb S.D., King B.A., Neff L.J. Current cigarette smoking among adults — United States, 2016. MMWR Morb. Mortal. Wkly Rep. 2018;67(2):53–59. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6702a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung E.H., Sundar S.S. Older adults’ activities on Facebook: can affordances predict intrinsic motivation and well-being? Health Commun. 2020 doi: 10.1080/10410236.2020.1859722. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaplan A.M., Haenlein M. Users of the world, unite! The challenges and opportunities of social media. Bus. Horizons. 2010;53(1):59–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bushor.2009.09.003. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kates J., Ranji U., Beamesderfer A., Salganicoff A., Dawson L. Health and access to care and coverage for lesbian, gay, bisexual, and transgender (LGBT) individuals in the U.S. 2018. https://www.kff.org/racial-equity-and-health-policy/issue-brief/health-and-access-to-care-and-coverage-for-lesbian-gay-bisexual-and-transgender-individuals-in-the-u-s/

- Lampkin D., Crawley A., Lopez T.P., Mejia C.M., Yuen W., Levy V. Reaching suburban men who have sex with men for STD and HIV services through online social networking outreach: a public health approach. J. Acquir. Immune Defic. Syndr. 2016;72(1):73–78. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000930. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lelutiu-Weinberger C., Pachankis J.E., Gamarel K.E., Surace A., Golub S.A., Parsons J.T. Feasibility, acceptability, and preliminary efficacy of a live-chat social media intervention to reduce HIV risk among young men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(7):1214–1227. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0911-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A., Altman D.G., Tetzlaff J., Mulrow C., Gotzsche P.C., Ioannidis J.P.A., Clarke M., Devereaux P.J., Kleijnen J., Moher D. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate healthcare interventions: explanation and elaboration. Bmj. 2009;10(1136):2700–2727. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marshal M., Dietz L., Friedman M., Stall R., Smith H., McGinley J., Thoma B., Murray P., D’Augelli A., Brent D. Suicidality and depression disparities between sexual minority and heterosexual youth: a meta-analytic review. J. Adolesc. Health Off. Publ. Soc. Adolesc. Med. 2011;49(2):115–123. doi: 10.1016/j.jadohealth.2011.02.005. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McHugh M.L. Interrater reliability: the kappa statistic. Biochem. Med. 2012;22(3):276–282. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/23092060 [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Meyer I. Prejudice, social stress, and mental health in lesbian, gay, and bisexual populations: conceptual issues and research evidence. Psychol. Bull. 2003;129(5):674–697. doi: 10.1088/1367-2630/15/1/015008.Fluid. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher D., Liberati A., Tetzlaff J., Altman D.G., Altman D., Antes G., Atkins D., Barbour V., Barrowman N., Berlin J.A., Clark J., Clarke M., Cook D., D'Amico R., Deeks J.J., Devereaux P.J., Dickersin K., Egger M., Ernst E.…Tugwell P. Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: the PRISMA statement. PLoS Med. 2009;6(7) doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1000097. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moore R.J., Arar R. Springer; Cham: 2018. Conversational UX Design: An Introduction; pp. 1–16. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Nesi J., Choukas-Bradley S., Prinstein M.J. Transformation of adolescent peer relations in the social media context: part 2-application to peer group processes and future directions for research. Clin. Child. Fam. Psychol. Rev. 2018;21(3):295–319. doi: 10.1007/s10567-018-0262-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nimrod G. Changes in internet use when coping with stress: older adults during the COVID-19 pandemic. Am. J. Geriatr. Psychiatr. 2020;28(10):1020–1024. doi: 10.1016/j.jagp.2020.07.010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- O’Cathain A., Hoddinott P., Lewin S., Thomas K.J., Young B., Adamson J., Jansen Y.J.F.M., Mills N., Moore G., Donovan J.L. Pilot and Feasibility Studies. vol. 1. BioMed Central Ltd; 2015. Maximising the impact of qualitative research in feasibility studies for randomised controlled trials: guidance for researchers; p. 32. Issue 1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagoto S., Waring M.E. A call for a science of engagement: comment on Rus and Cameron. Ann. Behav. Med. 2016;50(5):690–691. doi: 10.1007/s12160-016-9839-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pagoto S., Waring M., Jake-Schoffman D., Goetz J., Michaels Z., Oleski J., DiVito J. Proceedings of the 51st Hawaii International Conference on System Sciences. 2018. What type of engagement predicts success in a Facebook weight loss group? [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pagoto S., Waring M.E., Xu R. A call for a public health agenda for social media research. J. Med. Internet Res. 2019;21(12) doi: 10.2196/16661. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Patel V.V., Rawat S., Dange A., Lelutiu-Weinberger C., Golub S.A. An internet-based, peer-delivered messaging intervention for HIV testing and condom use among men who have sex with men in India (CHALO!): pilot randomized comparative trial. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2020;6(2) doi: 10.2196/16494. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pedrana A., Hellard M., Gold J., Ata N., Chang S., Howard S., Asselin J., Ilic O., Batrouney C., Stoove M. Queer as Fk: reaching and engaging gay men in sexual health promotion through social networking sites. J. Med. Internet Res. 2013;15(2):1–16. doi: 10.2196/jmir.2334. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Perrin A., Anderson M. Social media usage in the U.S. in 2019|Pew Research Center. 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/04/10/share-of-u-s-adults-using-social-media-including-facebook-is-mostly-unchanged-since-2018/

- Perski O., Blandford A., West R., Michie S. Conceptualising engagement with digital behaviour change interventions: a systematic review using principles from critical interpretive synthesis. Transl. Behav. Med. 2017;7(2):254–267. doi: 10.1007/s13142-016-0453-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenkrantz D.E., Black W.W., Abreu R.L., Aleshire M.E., Fallin-Bennett K. Health and health care of rural sexual and gender minorities: a systematic review. Stigma Health. 2017;2(3):229–243. doi: 10.1037/sah0000055. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Safer J.D., Coleman E., Feldman J., Garofalo R., Hembree W., Radix A., Sevelius J. Barriers to healthcare for transgender individuals. Curr. Opin. Endocrinol. Diabetes Obes. 2016;23(2):168–171. doi: 10.1097/MED.0000000000000227. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schulz K.F., Altman D.G., Moher D., CONSORT Group CONSORT 2010 statement: updated guidelines for reporting parallel group randomised trials. BMJ (Clin. Res. Ed.) 2010;340 doi: 10.1136/BMJ.C332. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Seidenberg A.B., Jo C.L., Ribisl K.M., Lee J.G.L., Butchting F.O., Kim Y., Emery S.L. A national study of social media, television, radio, and internet usage of adults by sexual orientation and smoking status: implications for campaign design. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health. 2017;14(4):1–14. doi: 10.3390/ijerph14040450. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Short C.E., DeSmet A., Woods C., Williams S.L., Maher C., Middelweerd A., Müller A.M., Wark P.A., Vandelanotte C., Poppe L., Hingle M.D., Crutzen R. Measuring engagement in eHealth and mHealth behavior change interventions: viewpoint of methodologies. J. Med. Internet Res. 2018;20(11) doi: 10.2196/jmir.9397. Journal of Medical Internet Research. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sun C.J., Stowers J., Miller C., Bachmann L.H., Rhodes S.D. Acceptability and feasibility of using established geosocial and sexual networking mobile applications to promote HIV and STD testing among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2015;19(3):543–552. doi: 10.1007/s10461-014-0942-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner A.E., Song E.Y., Mann-Jackson L., Alonzo J., Schafer K., Ware S., Garcia J.M., Arellano Hall E., Bell J.C., Van Dam C.N., Rhodes S.D. Preliminary impact of the weCare social media intervention to support health for Young men who have sex with men and transgender women with HIV. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(11):450–458. doi: 10.1089/apc.2018.0060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thabane L., Hopewell S., Lancaster G.A., Bond C.M., Coleman C.L., Campbell M.J., Eldridge S.M. Methods and processes for development of a CONSORT extension for reporting pilot randomized controlled trials. Pilot Feasib. Stud. 2016;2(1) doi: 10.1186/s40814-016-0065-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tickle-Degnen L. Nuts and bolts of conducting feasibility studies. Am. J. Occup. Ther. Off. Publ. Am. Occup. Ther. Assoc. 2013;67(2):171–176. doi: 10.5014/ajot.2013.006270. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Valanis B.G., Bowen D.J., Bassford T., Whitlock E., Charney P., Carter R.A. Sexual orientation and health: comparisons in the Women’s health initiative sample. Arch. Fam. Med. 2000;9(9):843–853. doi: 10.1001/archfami.9.9.843. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel E.A., Belohlavek A., Prochaska J.J., Ramo D.E. Development and acceptability testing of a Facebook smoking cessation intervention for sexual and gender minority young adults. Internet Interv. 2019;15(January):87–92. doi: 10.1016/j.invent.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogel E.A., Thrul J., Humfleet G.L., Delucchi K.L., Ramo D.E. Smoking cessation intervention trial outcomes for sexual and gender minority young adults. Health Psychol. 2019;38(1):12–20. doi: 10.1037/hea0000698. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallinheimo A.-S., Evans S.L. More frequent Internet use during the COVID-19 pandemic associates with enhanced quality of life and lower depression scores in middle-aged and older adults. Healthcare. 2021;9(4):393. doi: 10.3390/healthcare9040393. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waring M.E., Jake-Schoffman D.E., Holovatska M.M., Mejia C., Williams J.C., Pagoto S.L. Social media and obesity in adults: a review of recent research and future directions. Curr. Diabetes Rep. 2018;18(6) doi: 10.1007/s11892-018-1001-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Washington T.A., Applewhite S., Glenn W. Using Facebook as a platform to direct young Black men who have sex with men to a video-based HIV testing intervention: a feasibility study. Urban Soc. Work. 2017;1(1):36–52. doi: 10.1891/2474-8684.1.1.36. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Welch V., Petkovic J., Pardo Pardo J., Rader T., Tugwell P. Interactive social media interventions to promote health equity: an overview of reviews. Health Promot. Chronic Dis. Prev. Can. 2016;36(4):63–75. doi: 10.24095/hpcdp.36.4.01. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willging C.E., Salvador M., Kano M. Unequal treatment: mental health care for sexual and gender minority groups in a rural state. Psychiatr. Serv. 2006;57(6):867–870. doi: 10.1176/ps.2006.57.6.867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yardley L., Spring B.J., Riper H., Morrison L.G., Crane D.H., Curtis K., Merchant G.C., Naughton F., Blandford A. Understanding and promoting effective engagement with digital behavior change interventions. Am. J. Prev. Med. 2016;51(5):833–842. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2016.06.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Young S.D., Jaganath D. Online social networking for HIV education and prevention: a mixed-methods analysis. Sex. Transm. Dis. 2013;40(2):162–167. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0b013e318278bd12. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhu X., Zhang W., Operario D., Zhao Y., Shi A., Zhang Z., Gao P., Perez A., Wang J., Zaller N., Yang C., Sun Y., Zhang H. Effects of a mobile health intervention to promote HIV self-testing with MSM in China: a randomized controlled trial. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(11):3129–3139. doi: 10.1007/s10461-019-02452-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

PRISMA checklist.

PROSPERO Registration Form and Approval.

Online search strategy.

Evaluation of accurate reporting of studies Included using criteria from the CONSORT extension for pilot and feasibility trials.

Evaluation of accurate reporting of studies included using criteria from the CONSORT extension for randomized trials.