Abstract

The sperm-specific Ca2+ channel CatSper registers chemical cues that assist human sperm to fertilize the egg. Prime examples are progesterone and prostaglandin E1 that activate CatSper without involving classical nuclear and G protein-coupled receptors, respectively. Here, we study the action of seminal and follicular fluid as well of the contained individual prostaglandins and steroids on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration of sperm from donors and CATSPER2-deficient patients that lack functional CatSper channels. We show that any of the reproductive steroids and prostaglandins evokes a rapid Ca2+ increase that invariably rests on Ca2+ influx via CatSper. The hormones compete for the same steroid- and prostaglandin-binding site to activate the channel, respectively. Analysis of the hormones’ structure–activity relationship highlights their unique pharmacology in sperm and the chemical features determining their effective properties. Finally, we show that Zn2+ suppresses the action of steroids and prostaglandins on CatSper, which might prevent premature prostaglandin activation of CatSper in the ejaculate, aiding sperm to escape from the ejaculate into the female genital tract. Altogether, our findings reinforce that human CatSper serves as a promiscuous chemosensor that enables sperm to probe the varying hormonal microenvironment prevailing at different stages during their journey across the female genital tract.

Keywords: CatSper, human sperm, steroids, prostaglandins, reproductive fluids

Introduction

During their journey to the egg, mammalian sperm face an ever-changing chemical milieu, ranging from seminal fluid over secretions of cells lining the female genital tract and surrounding the egg to follicular fluid, which enters the oviduct upon ovulation. In human sperm, the sperm-specific Ca2+ channel CatSper translates changes in the chemical microenvironment into changes of the intracellular Ca2+ concentration ([Ca2+]i) and swimming behavior (Tamburrino et al., 2014; Brown et al., 2019; Wang et al., 2021). Aberrations of CATSPER genes, some of which were shown to result in a loss of CatSper function, are associated with male infertility (Avidan et al., 2003; Avenarius et al., 2009; Hildebrand et al., 2010; Smith et al., 2013; Jaiswal et al., 2014; Williams et al., 2015; Brown et al., 2018; Luo et al., 2019; Schiffer et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020), indicating that CatSper serves as a central signaling knot in human sperm. Quite generally, CatSper is gated by membrane depolarization and intracellular alkalization (Kirichok et al., 2006; Lishko et al., 2010; Seifert et al., 2015; Hwang et al., 2019). In human sperm, CatSper is also activated by prostaglandins and steroids (Lishko et al., 2011; Strünker et al., 2011), the predominant hormones in seminal and follicular fluid (e.g., Bygdeman and Samuelsson, 1966; de los Santos et al., 2012), respectively, which are also released by the oviductal epithelium and cumulus cells surrounding the egg (Ogra et al., 1974; Vastik-Fernandez et al., 1975; Schuetz and Dubin, 1981; Libersky and Boatman, 1995). Our knowledge about the steroid and prostaglandin control of CatSper and human sperm originates especially from studies using progesterone and prostaglandin E (e.g., PGE1). Progesterone or PGE1 activation of CatSper evokes a rapid Ca2+ increase (Blackmore et al., 1990; Baldi et al., 1991; Schaefer et al., 1998; Shimizu et al., 1998; Harper et al., 2003; Bedu-Addo et al., 2007; Strünker et al., 2011; Servin-Vences et al., 2012; Brenker et al., 2018b), which has been implicated in human sperm chemotaxis, hyperactivation, penetration into viscous medium, and/or acrosomal exocytosis (Aitken and Kelly, 1985; Schaefer et al., 1998; Harper et al., 2003; Bedu-Addo et al., 2007; Oren-Benaroya et al., 2008; Publicover et al., 2008; Baldi et al., 2009; Kilic et al., 2009; Servin-Vences et al., 2012; Alasmari et al., 2013; Sanchez-Cardenas et al., 2014; Schiffer et al., 2014; Tamburrino et al., 2014, 2015, 2020; Brown et al., 2017; Rennhack et al., 2018). However, reproductive fluids comprise rather a complex cocktail of various prostaglandins and steroids (Samuelsson, 1963; Bendvold et al., 1987; Munuce et al., 2006; Kushnir et al., 2009; Marchiani et al., 2020). Several steroids identified in follicular fluid evoke Ca2+ and motility responses in human sperm that are similar to those evoked by progesterone (Blackmore et al., 1990, 1996; Alexander et al., 1996; Luconi et al., 2004; Brenker et al., 2018b). Only for some of these steroids, e.g., 17-OH-progesterone and estradiol, it has been shown that they also act via CatSper (Lishko et al., 2011; Strünker et al., 2011; Brenker et al., 2018a, b; Rehfeld, 2020). Similarly, it has been shown that CatSper is also activated by prostaglandins other than PGEs, such as PGFs, which are also found in seminal fluid (Lishko et al., 2011; Brenker et al., 2018a). However, thus far, a comprehensive quantitative analysis of the action of physiologically relevant prostaglandins and steroids contained in reproductive fluids on [Ca2+]i and CatSper in human sperm has been lacking.

Here, we show that stimulation of sperm with follicular and seminal fluid evokes a rapid Ca2+ increase that rests predominantly on steroid and prostaglandin activation of CatSper, respectively. Moreover, we determined in a quantitative fashion the steroid content of follicular fluid and studied the action of the steroids on [Ca2+]i of human sperm. Similarly, we studied the action of the prostaglandins contained in seminal fluid. Each reproductive steroid and prostaglandin tested, i.e., 15 per class of hormone, evokes Ca2+ influx via CatSper, yet with different potency and efficacy; in sperm from CATSPER2-deficient patients that lack functional CatSper channels, the hormone-induced Ca2+ influx is abolished. Analysis of the structure–activity relationship revealed the particular structural features rendering a hormone more or less potent to activate the channel. Furthermore, we show that all reproductive steroids employ the same steroid-binding site and, thereby, compete for CatSper activation, whereas prostaglandins compete all for the same prostaglandin-binding site to activate the channel. Altogether, our results suggest that the hormonal control of CatSper and, thereby, sperm function involves a concerted (inter)action of the various prostaglandins and steroids that sperm are exposed to within the female genital tract. Finally, we show that Zn2+, which is present at millimolar concentration in seminal fluid, suppresses hormone activation of CatSper. The complex opposing action of seminal Zn2+ and prostaglandins on CatSper might prevent premature activation of CatSper in the ejaculate and serve as a dilution sensor for sperm, assisting sperm to escape from the ejaculate into the female genital tract.

Results

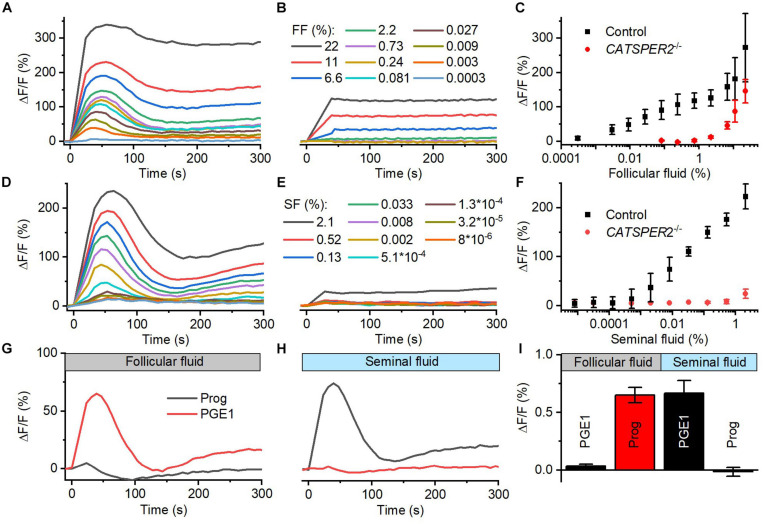

Follicular and Seminal Fluid-Evoked Ca2+ Signals in Human Sperm Are Predominantly Mediated by CatSper

We studied the action of follicular (FF) and seminal fluid (SF) on the intracellular Ca2+ concentration of human sperm. To this end, populations of human sperm were challenged with dilute solutions of the respective fluid and [Ca2+]i was monitored using a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator. In sperm from donors, both FF and SF evoked a rapid [Ca2+]i increase, consisting of a Ca2+ transient (Figures 1A–F) followed by a second sustained elevation of [Ca2+]i (Figures 1A,D); similar FF-induced Ca2+ signals were reported before (Thomas and Meizel, 1988; Blackmore et al., 1990; Hong et al., 1993; Brown et al., 2017). The amplitude of the Ca2+ signal increased in a dose-dependent fashion: the FF-induced signal first saturated at about 1% FF (final concentration, volume/volume percentage), but then continued to rise at FF ≥ 2.2% (Figures 1A,C), whereas the signal evoked by SF increased rather steadily with increasing SF (Figures 1D,F). It has been suggested that FF-induced Ca2+ signals rest predominantly, but not exclusively, on Ca2+ influx via CatSper (Brown et al., 2017). Supporting this notion and indicating that CatSper also mediates the signals induced by SF, Ca2+ signals evoked by ≤2.2% FF and <2% SF were abolished in sperm from CATSPER2-deficient patients (Figures 1B,E) lacking functional CatSper channels (see Brenker et al., 2018b; Schiffer et al., 2020; Wang et al., 2020); at higher concentrations, both FF and SF evoked a residual, sustained [Ca2+]i increase in CATSPER2–/– sperm that might rest on inhibition of Ca2+ export and/or Ca2+ release from intracellular stores. We can, however, not exclude that the residual signal reflects an artifactual increase in the fluorescence of indicators rather than a genuine [Ca2+]i response.

FIGURE 1.

Follicular and seminal fluid-evoked Ca2+ signals in human sperm. (A) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by dilute solutions of follicular fluid (FF); the final FF concentration is indicated as volume/volume percentage. [Ca2+]i was monitored in control sperm from donors loaded with a fluorescent Ca2+ indicator, using a fluorescence plate reader. ΔF/F (%) indicates the percent change in fluorescence (ΔF) with respect to the mean basal fluorescence (F) before application (and subsequent continuous presence) of FF at t = 0. (B) Representative FF-evoked Ca2+ signals in sperm from patients deficient for the CATSPER2 gene (CATSPER2–/–), lacking functional CatSper channels. (C) Concentration–response relationship for the mean (±SD) maximal signal amplitudes evoked by FF in control and CATSPER2–/– sperm (n = 3). (D) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by dilute solutions of seminal fluid (SF) in control (D) and CATSPER2–/– (E) sperm. (F) Concentration–response relationship for the mean (±SD) maximal signal amplitudes (n = 3). (G) Representative progesterone- and PGE1-evoked Ca2+ signal in control sperm preincubated in 1% FF or (H) 0.5% SF; progesterone or PGE1 was applied at t = 0. (I) Mean (±SD) maximal amplitude of progesterone- and PGE1-evoked Ca2+ signals in control sperm preincubated in 1% FF or 0.5% SF (n = 4).

The activation of CatSper by reproductive fluids does not rest on an increase of the intracellular pH (pHi): SF did not affect pHi of human sperm (Supplementary Figures 1C,D), and FF slightly decreased pHi (Supplementary Figures 1A,B), yet only at high concentrations. Cross-desensitization experiments demonstrate that the activation of CatSper by FF and SF is rather mediated by the contained steroids and prostaglandins, respectively: In sperm preincubated in FF, progesterone- but not PGE1-evoked Ca2+ influx was abolished (Figures 1G,I), whereas preincubation of sperm in SF abolished PGE1- but not progesterone-induced Ca2+ influx (Figures 1H,I). We investigated the action of the individual steroids and prostaglandins in the reproductive fluids in more detail.

Analysis of the Steroid Content of Human Follicular Fluid

We determined by LC-MS/MS the concentration of 16 steroids, representing all major classes, in follicular fluid obtained during ovum pickup for assisted reproduction from gonadotropin-stimulated patients; FF of eight ova from four patients was pooled to yield averaged concentrations. The FF contained only picomolar concentrations of deoxycortisols, whereas all other steroids were present at nano- to micromolar concentrations (Table 1). These results are in line with those of previous studies (e.g., Walters et al., 2019). The steroid concentrations in pooled FF from 10 ova obtained from 10 patients not stimulated with gonadotropin are shown in Supplementary Table 1.

TABLE 1.

Steroid composition of pooled human follicular fluid.

| Concentration of steroids in FF (nM) | |||

| Progesterone | 28,880 | Cortisone | 20 |

| Pregnenolone | 1,470 | Androstendione | 4 |

| 17-OH-progesterone | 2,982 | Androstenediol | 20 |

| 17-OH-pregnenolone | 115 | Dehydroepiandrosterone | 463 |

| 11-Deoxycorticosterone | 65 | Testosterone | 2 |

| Corticosterone | 6 | Estradiol | 1,221 |

| 11-Deoxycortisol | 0.03 | Estrone | 76 |

| 21-Deoxycortisol | 0.19 | Estriol | 8 |

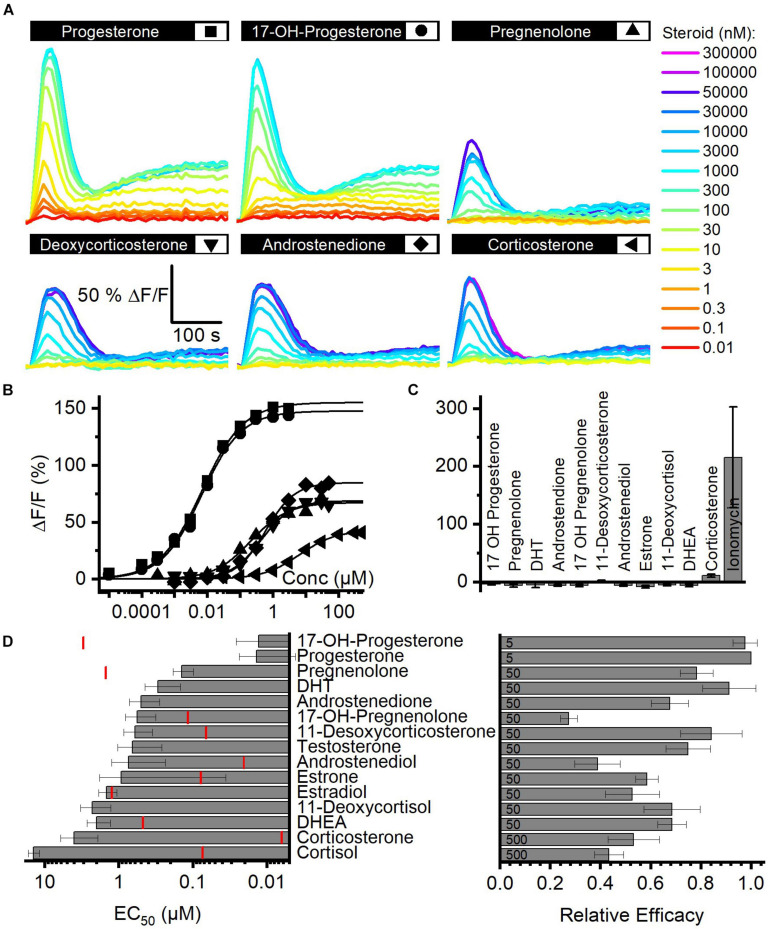

The Action of Reproductive Steroids on CatSper in Human Sperm

We determined the structure–activity relationship for the activation of human CatSper by steroids contained in FF. To this end, we studied Ca2+ signals evoked by individual steroids and analyzed their concentration–response relationship (Figure 2A). With no exception, each of the 15 steroids tested evoked a biphasic Ca2+ response (Figures 2A,B,D) that was abolished in CATSPER2–/– sperm (Figure 2C; Brenker et al., 2018b), demonstrating that the response rests on Ca2+ influx via CatSper. The steroids differed, however, in their potency and efficacy to evoke Ca2+ influx (Figures 2B,D and Supplementary Table 2) (Brenker et al., 2018b). With decreasing potency, also the efficacy tended to decrease, indicating that the two parameters are correlated (Figure 2D and Supplementary Figure 2).

FIGURE 2.

Steroid-evoked Ca2+ signals in human sperm. (A) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by progesterone, 17-OH-progesterone, pregnenolone, deoxycorticosterone, corticosterone, or androstenedione in control sperm from donors. (B) Concentration–response relationship for the maximal amplitudes of signals shown in (A). (C) Mean (±SD) maximal amplitude of Ca2+ signals evoked by steroids [at the concentration indicated in (D); right panel] or the Ca2+-ionophore ionomycin (2 μM) in CATSPER2–/– sperm (n = 3). (D) Left: potency, i.e., mean (±SD) EC50 (n ≥ 4), of steroids to evoke Ca2+ signals in control sperm (red lines indicate the concentration of the steroid in follicular fluid); right: relative efficacy of steroids to evoke Ca2+ signals in control sperm, i.e., mean (±SD) maximal signal amplitude evoked by the respective steroid at the indicated saturating concentration (in μM) relative to that evoked by progesterone (set to 1) (n ≥ 5).

Moreover, we recognized that patterns of pharmacological properties coincide with structural features. First, progesterone and 17-OH-progesterone represent the most potent and efficacious steroids and activate CatSper with similar potency and efficacy. This indicates that the introduction of an OH group at the 17α-position of progesterone does not affect the activation of the channel. Modifications of progesterone and 17-OH-progesterone at the same positions affect the potency in a similar fashion: reduction of the ketone at 3-position and a shift of the double bond from 4/5- to 5/6-position decreases the potency by about 10-fold (Figure 2D; compare pregnenolone and 17-OH-pregnenolone to progesterone and 17-OH-progesterone, respectively). Increasing the polarity by the successive addition of OH groups at 21-position (deoxycorticosterone) and 17α- as well as 21-position (11-deoxycortisol) decreases the potency by 10- and 100-fold, respectively. The potency to activate CatSper also decreases with the number of OH groups attached to the cholesterol backbone, though OH groups attached to the 17α-position are better tolerated than groups attached to 11-position; relative potency: cortisol (OH at C-11, C-17α, and C-21) < corticosterone (OH at C-11 and C-21) < 11-deoxycortisol (OH at C 17α and C-21) < deoxycorticosterone (OH at C-21). Finally, steroids lacking an acyl group at 17-position (androgens) are 100-fold less potent than progesterone, whereas the presence of an OH (Figure 2D, compare estrone versus testosterone and androstenediol) or a keto group (Figure 2D; compare dehydroepiandrosterone versus androstenedione and estradiol) at 17-position hardly affects the potency. The group at 3-position does not affect the potency either: compare χ,δ-unsaturated alcohol (dehydroepinadrosterone versus androstenediol), α,β-unsaturated ketone (androstenedione testosterone), and phenol (estrone, estradiol). In a nutshell, augmenting the steroid polarity by additional OH groups hampers CatSper activation, especially for the glucocorticoids cortisol and corticosterone, where the OH group is bound to C11 of the cholesterol backbone.

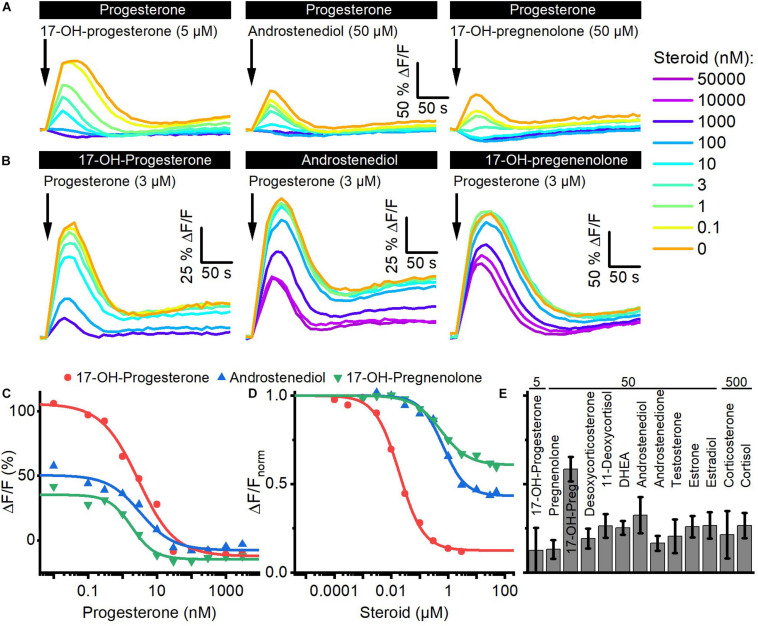

Reproductive Steroids Compete for the Same Binding Site to Activate CatSper

We investigated whether the steroids in follicular fluid employ the same binding site to activate CatSper. To this end, we performed cross-desensitization experiments (Strünker et al., 2011; Brenker et al., 2018b): we challenged sperm preincubated in different concentrations of progesterone with a saturating concentration of 17-OH-progesterone, androstenediol, or 17-OH-pregnenolone and monitored the ensuing Ca2+ response (Figures 3A,C). Progesterone suppressed in a concentration-dependent fashion the steroid-evoked Ca2+ signals; at > 300 nM progesterone, i.e., concentrations at which the amplitude of the Ca2+ signal evoked by progesterone itself saturate (Figure 2B), the 17-OH- progesterone-, androstenediol-, or 17-OH-pregnenolone-evoked signals were abolished (Figures 3A,C). The IC50 of progesterone to suppress the steroid responses was 8.5 ± 6.1 nM for 17-OH-progesterone, 5.0 ± 2.8 nM for androstenediol, and 2.6 ± 0.9 nM for 17-OH-pregnenolone (n = 3) (Figure 3C), which is similar to the EC50 of progesterone to evoke Ca2+ signals in human sperm (Figure 2B). Vice versa, we challenged sperm preincubated in different concentrations of 17-OH-progesterone, androstenediol, or 17-OH-pregnenolone with a saturation concentration of progesterone and monitored the ensuing Ca2+ signal (Figures 3B,D). The progesterone-evoked Ca2+ signal was suppressed by 17-OH-progesterone, androstenediol, and 17-OH-pregnenolone in a concentration-dependent fashion (Figures 3B,D) with an IC50 of 23.8 ± 7.27 nM (n = 4), 2.5 ± 1.7 μM (n = 3), and 1.63 ± 2.33 μM (n = 3), respectively, which is similar to the EC50 value of the respective steroid to evoke Ca2+ signals (Figure 2D). Of note, the progesterone response was completely abolished by preincubation with 17-OH-progesterone, but not with androstenediol or 17-OH-pregnenolone (Figures 3B,D). For example, upon preincubation with ≥ 10 μM androstenediol or 17-OH-pregnenolone, the amplitude of the progesterone-evoked Ca2+ response settled at a constant residual level. Residual progesterone-induced Ca2+ signals were also observed upon preincubation with a saturating concentration of any of the other steroids identified in follicular fluid (Figure 3E). Together, these results demonstrate that the reproductive steroids compete all for the same binding site to activate CatSper. Moreover, displacing a weakly (e.g., androstenediol, 17-OH-pregnenolone) with a highly efficacious steroid (e.g., progesterone) from the steroid-binding site reinduces Ca2+ influx via CatSper; the amplitude of the Ca2+ signal correlates negatively with the efficacy of the steroid displaced (Figures 2D, 3D).

FIGURE 3.

Steroids compete for the same binding site to activate CatSper in human sperm. (A) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by a saturating concentration of 17-OH-progesterone (5 μM), androstenediol (50 μM), or 17-OH-pregnenolone (50 μM) in sperm preincubated in different concentrations of progesterone. (B) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by a saturating concentration of progesterone (3 μM) in sperm preincubated in different concentrations of 17-OH-progesterone, androstenediol, or 17-OH-pregnenolone. (C) Maximal amplitude of steroid-evoked Ca2+ responses shown in (A), plotted as a function of the (preincubated) progesterone concentration. (D) Maximal amplitude of the progesterone-evoked Ca2+ responses shown in (B), plotted as a function of the (preincubated) steroid concentration. (E) Mean (±SD) maximal amplitude of the Ca2+ signal evoked by progesterone (3 μM) in sperm preincubated in the indicated (in μM) saturating concentration of the respective steroid (n = 3–8).

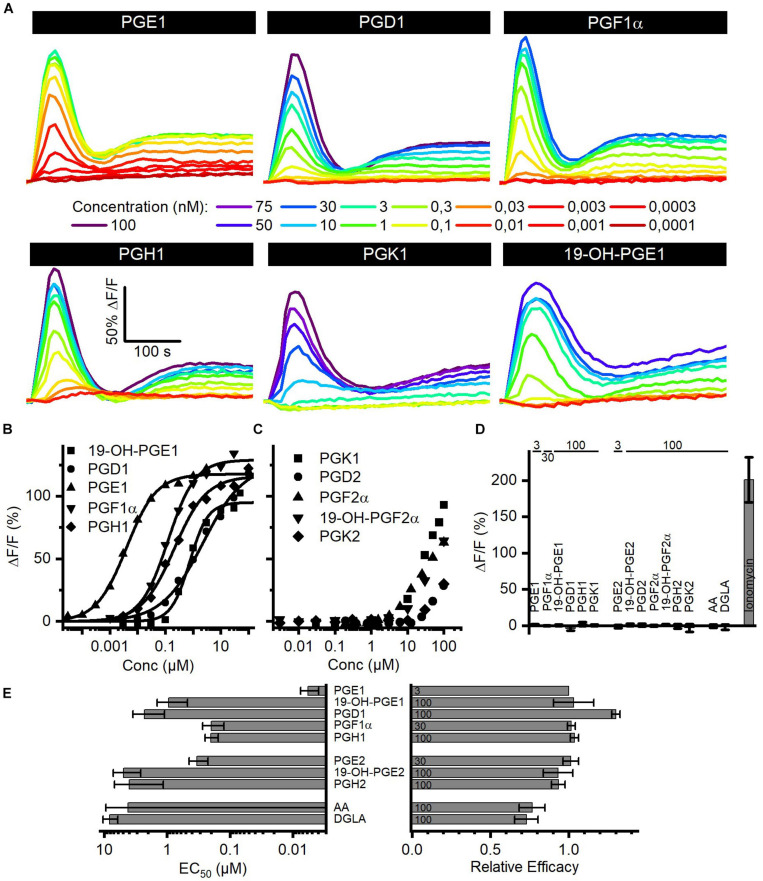

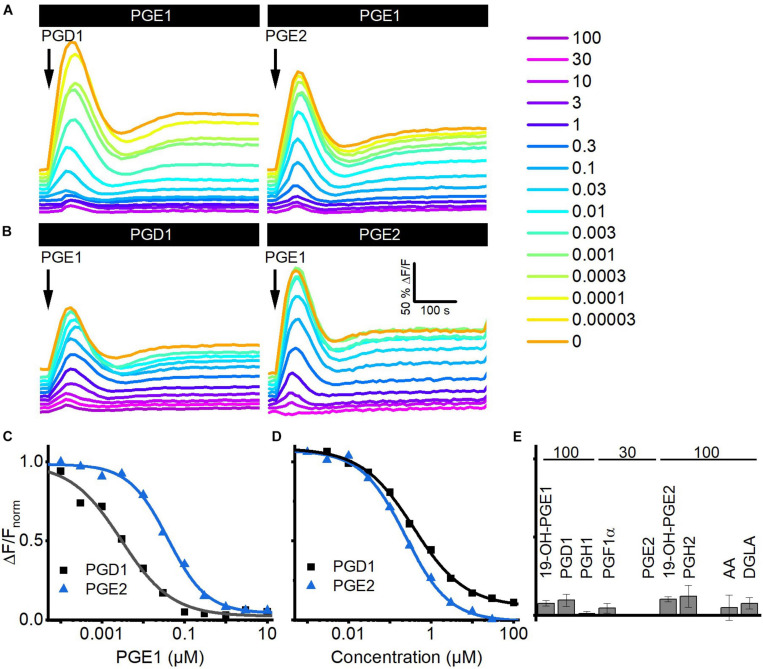

The Action of Reproductive Prostaglandins on CatSper in Human Sperm

Seminal fluid contains a cocktail of various prostaglandins at concentrations from the low nano- to the high micromolar range (Table 2). We determined the structure–activity relationship for the activation of human CatSper by reproductive prostaglandins as well as prostaglandin H1 and H2 (PGH1, PGH2) and the prostaglandin precursors arachidonic acid (AA) and dihomo-γ-linolenic acid (DGLA). To this end, we studied Ca2+ signals evoked by the individual prostaglandins and analyzed the concentration–response relationships (Figures 4A,B). Each of the prostaglandins tested evoked a biphasic Ca2+ signal that was abolished in CATSPER2–/– sperm (Figures 4A,D), demonstrating that the response rests on Ca2+ influx via CatSper. The prostaglandins differed considerably in their potency to increase [Ca2+]i, but in contrast to steroids, the efficacy was rather similar (Figures 4A,E and Supplementary Figure 2) and did not correlate with the potency (compare Figures 2D, 4E and Supplementary Figure 2). Of note, we failed to determine an EC50 for PGK1, PGK2, PGF2α, 19-OH-PGF2α, and PGD2. Even at the highest possible concentration tested, i.e., 100 μM, the amplitude of the Ca2+ signal did not reach saturation (Figure 4C), indicating that these prostaglandins activate CatSper with very low potency. PGE1 represented the most potent prostaglandin. In general, prostaglandins with one double bond (PGX1) are more potent than their counterpart with two double bonds (PGX2). For example, PGE2 is about 55-fold less potent than PGE1. Moreover, PGE1 contains a ketone in 9-position and an alcohol in 11-position. Changing the ketone into an alcohol decreases the potency only by 20-fold (Figures 4B,E, compare PGE1 versus PGF1α), whereas the presence of ketone at 11-position (compare PGE1 versus PGD1 and PGK1) decreases the potency considerably, i.e., by at least 1,000-fold (Figures 4B,E, compare PGE1 versus PGD1). Remarkably, a ketone at 11-position seems to increase the efficacy (Figure 4B, compare PGE1 versus PGD1). The finding that a peroxide bicyclic to the cyclopentane decreases the potency by only about 35-fold (Figure 4B, compare PGE1 versus PGH1) suggests that the OH group at 11-position is beneficial, but not required, for a submicromolar EC50. Introduction of an OH group at 19-position decreases the potency, however, considerably (Figure 4B, compare PGE1 versus 19-OH-PGE1). Finally, both AA and DGLA comprise several double bonds instead of O-atom-containing functional groups. AA and DGLA are about 1,000-fold less potent than PGE1. Nevertheless, they are still more potent than some of the prostaglandins tested (e.g., PGK1, PGK2, PGF2α, 19-OH-PGF2α, and PGD2).

TABLE 2.

Prostaglandin concentrations in SF.

| Concentrations of prostaglandins in SF (μM) | |

| 19-OH-PGE1+2 | 720 ± 369 |

| 19-OH-PGF1α | 58 ± 1 |

| PGE2 | 33 ± 12 |

| PGE1 | 25 ± 15 |

| PGF1α | 7 ± 4 |

| PGF2α | 6 ± 2 |

Mean (±SD) concentration reported by Bygdeman and Samuelsson (1966); Isidori et al. (1980), Gerozissis et al. (1982); Aitken and Kelly (1985), and Schaefer et al. (1998).

FIGURE 4.

Prostaglandin-evoked Ca2+ signals in human sperm. (A) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by PGE1, PGD1, PGF1α, PGH1, or 19-OH-PGE1 in control sperm from donors. (B) Concentration–response relationship for the maximal amplitudes of Ca2+ signals shown in (A), except for PGK1. (C) Concentration–response relationship for the maximal amplitudes of Ca2+ signals evoked by PGK1, PGD2, PGF2α, 19-OH-PGF2α, or PGK2; the concentration–response relationships could not be fitted to derive an EC50, because the signal amplitudes did not saturate at the highest concentration tested. (D) Mean (±SD) maximal amplitude of Ca2+ signals evoked by prostaglandins (at the concentration indicated in μM) or the Ca2+-ionophore ionomycin (2 μM) in CATSPER2–/– sperm (n = 3–5). (E) Left: potency, i.e., mean (±SD) EC50 (n = 3–4), of prostaglandins to evoke Ca2+ signals in control sperm; right: relative efficacy of prostaglandins to evoke Ca2+ signals in control sperm, i.e., mean (±SD) maximal signal amplitude evoked by the respective prostaglandin at the indicated saturating concentration (in μM) relative to that evoked by PGE1 (set to 1) (n = 3–4).

Reproductive Prostaglandins Compete for the Same Binding Site to Activate CatSper

We investigated whether prostaglandins employ the same binding site to activate CatSper using cross-desensitization experiments. We challenged sperm preincubated in different concentrations of PGE1 with a saturating concentration of PGD1 or PGE2. PGE1 suppressed in a concentration-dependent fashion the prostaglandin-evoked Ca2+ signals; at > 0.1 μM PGE1, i.e., concentrations at which the amplitude of Ca2+ signals evoked by PGE1 itself saturate, the PGD1- and PGE2-evoked signals were completely abolished (Figures 5A,C). The IC50 of PGE1 to suppress the prostaglandin responses was 2.2 ± 0.6 nM for PGD1 and 18 ± 7 nM for PGE2 (n = 3), which is similar to the EC50 of PGE1 to evoke Ca2+ signals in human sperm. Vice versa, in sperm preincubated in PGD1 or PGE2, the PGE1-induced Ca2+ signal was suppressed in a concentration-dependent fashion with an IC50 of 0.7 ± 0.4 and 0.24 ± 0.01 μM (n = 3) (Figures 5B,D), respectively, which is similar to the EC50 of the respective prostaglandin to evoke Ca2+ signals in human sperm. Of note, the PGE1 response was completely abolished upon preincubation with PGD1 and PGE2 (Figures 5B,D). Similarly, the PGE1-evoked Ca2+ signal was almost completely suppressed upon preincubation with a saturating concentration of any other prostaglandin tested (Figure 5E), reflecting the rather similar efficacy among prostaglandins to activate CatSper. Altogether, these results show that reproductive prostaglandins compete for the same prostaglandin-binding site to activate CatSper.

FIGURE 5.

Prostaglandins compete for the same binding site to activate CatSper in human sperm. (A) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by a saturating concentration of PGD1 (100 μM) and PGE2 (30 μM) in sperm preincubated in different concentrations of PGE1. (B) Representative Ca2+ signals evoked by a saturating concentration of PGE1 (3 μM) in sperm preincubated in different concentrations of PGD1 or PGE2. (C) Maximal amplitude of PGD1- and PGE2-evoked Ca2+ responses shown in (A), plotted as a function of the (preincubated) PGE1 concentration. (D) Maximal amplitude of the PGE1-evoked Ca2+ responses shown in (B), plotted as a function of the (preincubated) PGD1 or PGE2 concentration. (E) Mean (±SD) maximal amplitude of PGE1-evoked Ca2+ signals in sperm preincubated in the indicated (in μM) saturating concentrations of the respective prostaglandin (n = 3–4).

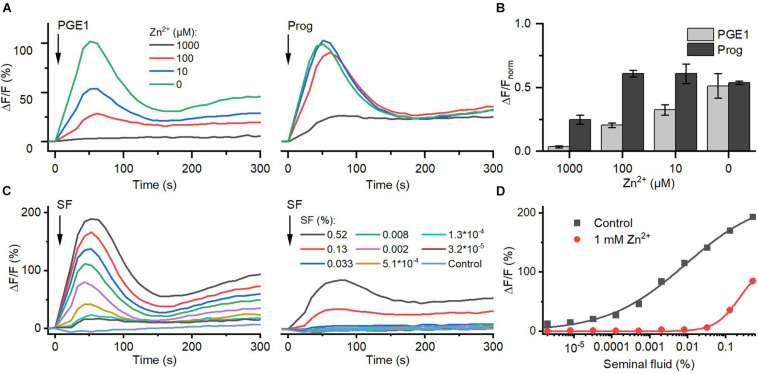

Zn2+ Inhibits Prostaglandin Activation of CatSper

Seminal fluid contains millimolar concentrations of Zn2+ (Cooper et al., 1991; Zhao et al., 2016). We investigated the action of Zn2+ on prostaglandin- and steroid-evoked Ca2+ influx via CatSper. At ≥10 μM, Zn2+ suppressed PGE1-induced Ca2+ influx in a dose-dependent fashion; the signal was almost completely abolished at 1 mM Zn2+ (Figures 6A,B). In contrast, at ≤100 μM, Zn2+ did not affect progesterone-evoked Ca2+ influx, and at 1 mM Zn2+, the signal amplitude was reduced only by about 60%. Of note, as a reference, we also recorded Ca2+ signals evoked by ionomycin in the absence and presence of Zn2+ (Supplementary Figure 3) and corrected for the Zn2+-induced decrease in the maximal signal amplitude (Figure 6B). Moreover, in sperm bathed in Zn2+ (1 mM), the Ca2+ influx evoked by ≤0.03 and >0.1% seminal fluid was also abolished and attenuated, respectively (Figures 6C,D). This indicates that Zn2+ suppresses prostaglandin activation of CatSper in the ejaculate.

FIGURE 6.

The action of Zn2+ on prostaglandin- and steroid-evoked Ca2+ signals in human sperm. (A) Representative Ca2+ signal evoked by progesterone (3 μM) and PGE1 (3 μM) in the absence and presence of different Zn2+ concentrations. (B) Mean (±SD) maximal amplitude of Ca2+ signals evoked by progesterone and PGE1 in the presence of indicated Zn2+ concentration normalized to the amplitude of the ionomycin-evoked Ca2+ signal recorded in parallel. (C) Representative seminal fluid-evoked Ca2+ signals in the absence (left) and presence (right) of Zn2+ (1 mM). (D) Concentration–response relationship for the maximal amplitudes of Ca2+ signals shown in (B).

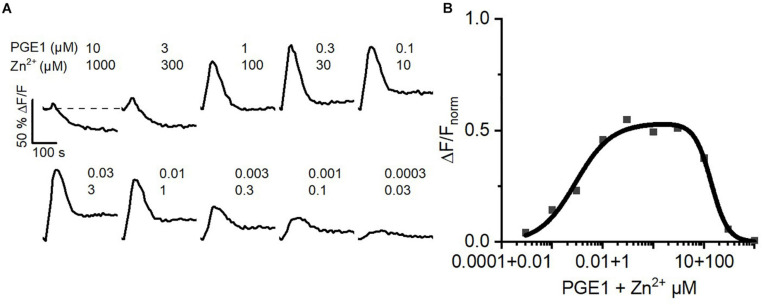

The Concerted Action of Prostaglandins and Zn2+ on CatSper Might Serve as a Dilution Sensor for Human Sperm

Inside the female genital tract, the ejaculate dilutes with female reproductive fluids and sperm escape from the ejaculate into the uterus and oviduct. Thus, in vivo, at the beginning of their journey across the female genital tract, sperm experience a decreasing concentration gradient of both seminal prostaglandins and Zn2+. We tried to emulate this scenario in vitro. To this end, we challenged sperm with serial dilutions of buffer containing 10 μM PGE1 and 1 mM Zn2+, i.e., a concentration ratio similar to that in the ejaculate. At low dilutions, the PGE1/Zn2+ mixture rather decreased [Ca2+]i, confirming that Zn2+ suppresses prostaglandin activation of CatSper (Figure 7A). However, with increasing dilution factor, the Zn2+ inhibition tapered off, giving rise to prostaglandin-evoked Ca2+ signals. The signal amplitude first grew with increasing dilution factor until it decreased again due to the decreasing PGE1, yielding a bell-shaped dilution–response relationship (Figure 7B). Sperm might harness the PGE1/Zn2+ interplay as a dilution sensor: in the ejaculate, the inhibition of prostaglandin-evoked Ca2+ influx by Zn2+ prevents premature activation of CatSper. However, upon dilution of the ejaculate, when sperm start escaping it in vivo, sperm are relieved from Zn2+ inhibition and the prostaglandin action commences. The relief of the Zn2+ inhibition and ensuing prostaglandin-evoked motility responses might promote the escape from the ejaculate into the female genital tract.

FIGURE 7.

Ca2+ signals evoked by dilute solutions of a Zn2+/PGE1 mixture. (A) Representative Ca2+ signals in human sperm stimulated with a serially diluted mixture of 10 μM PGE1 and 1 mM Zn2+. (B) Concentration–response relationship for the maximal amplitudes of Ca2+ signals shown in (A) relative to that evoked by PGE1 (3 μM) in the absence of Zn2+ (set to 1).

Discussion

In the past three decades, work by many groups, including our own, demonstrated that various steroids and prostaglandins increase [Ca2+]i in human sperm (e.g., Blackmore et al., 1990; Krausz et al., 1995; Alexander et al., 1996; Blackmore et al., 1996; Schaefer et al., 1998; Luconi et al., 2004; Baldi et al., 2009; Strünker et al., 2011; Brenker et al., 2018a, b; Rehfeld, 2020). Here, using CatSper-deficient sperm from infertile patients lacking the CATSPER2 gene, we show that Ca2+ responses evoked by reproductive steroids and prostaglandins rest invariably on Ca2+ influx via CatSper.

Our results are in line with that of most (Blackmore et al., 1990, 1996; Luconi et al., 1999, 2001; Rossato et al., 2005; Brenker et al., 2018b; Rehfeld, 2020), but not all, previous studies concerning the steroid action in sperm: Mannowetz et al. (2017) claimed that testosterone, hydrocortisone, and estradiol represent antagonists that abolish steroid activation of CatSper but themselves do not activate the channel. However, our results and those of a number of other, independent studies consistently show that also testosterone, hydrocortisone, and estradiol are, in fact, true agonists that activate CatSper (Luconi et al., 1999, 2001; Rossato et al., 2005; Brenker et al., 2018b; Rehfeld, 2020). This is not to say that CatSper is activated by any steroidal compound: levonorgestrel, the synthetic steroid used in intrauterine contraceptive devices, does not evoke a Ca2+ signal (Supplementary Figure 4), supporting the notion that C-17α is a key position for CatSper activation that does not tolerate an alkyne group. The steroid control of CatSper is a prime example for nonclassical steroid action, involving membranous rather than nuclear steroid receptors (Baldi et al., 2009; Tamburrino et al., 2020). It has been proposed that in sperm, steroids activate the membrane serine hydrolase α/β hydrolase domain-containing protein 2 (ABHD2), which in turn degrades 2-AG in the flagellar membrane, relieving CatSper from inhibition by 2-AG (Miller et al., 2016). We show that steroids increase [Ca2+]i in sperm with vastly different potency and efficacy (see also Luconi et al., 1999; Brenker et al., 2018b), suggesting that the hormones bind to ABHD2 with different affinities and act as either full or partial agonists. However, the pharmacology of the steroid-binding site supposedly controlling ABHD2 is unknown. Thus, to scrutinize the model of nonclassical steroid action in sperm, it is required to determine whether the pharmacology of the steroid activation of ABHD2 and CatSper matches. Of note, at high micromolar concentrations, progesterone activates not only CatSper, but also inhibits Slo3 (Brenker et al., 2014), the principal K+ channel in human sperm (Brenker et al., 2014). Whether steroids other than progesterone also target Slo3 is unknown and whether and how inhibition of Slo3 affects the potency and/or efficacy of steroids to evoke Ca2+ influx via CatSper remains to be determined.

Moreover, the efficacy to elevate [Ca2+]i might co-determine the gamut of behavioral responses evoked by a particular steroid. Not only progesterone but also estradiol, testosterone, and hydrocortisone promote the penetration of sperm into viscous medium, indicating that this behavioral response is rather independent of the efficacy of steroids (Rehfeld, 2020). By contrast, progesterone, but not estradiol, also evokes acrosomal exocytosis (Luconi et al., 2001; Rossato et al., 2005), suggesting that the increase of [Ca2+]i by estradiol is not sufficient to trigger acrosomal exocytosis. However, it needs to be systematically assessed whether the efficacy of steroids to increase [Ca2+]i and their ability to evoke particular cellular responses indeed correlate. Furthermore, on a single-cell level, progesterone activation of CatSper triggers long-lasting oscillations of [Ca2+]i (Kirkman-Brown et al., 2004; Bedu-Addo et al., 2007; Brown et al., 2017; Kelly et al., 2018; Mata-Martinez et al., 2018; Torrezan-Nitao et al., 2021) that seem to involve Ca2+-induced Ca2+ release and an interplay of CatSper with Slo3 (Torrezan-Nitao et al., 2021). Whether steroids other than progesterone also trigger such [Ca2+]i oscillations is unknown. However, the finding that steroid- and prostaglandin-induced Ca2+ signals are completely abolished in CATSPER2–/– sperm demonstrates that the hormones do not directly stimulate Ca2+ release.

Another question concerns the physiological significance of the promiscuous steroid activation of CatSper. Figure 2D shows that for some, but not all steroids, the concentration in follicular fluid suffices to activate CatSper. This suggests that in vivo, these steroids interplay to control the activity of CatSper. However, upon ovulation, only trace amounts of follicular fluid indeed enter the oviduct (Hansen et al., 1991). This suggest that at physiological dilutions, the steroid activation of CatSper by follicular fluid rests predominantly on the action of progesterone, representing by far the most abundant, efficient, and potent steroid. Supporting this notion, the action of follicular fluid on CatSper and human sperm is largely, but not entirely, mimicked by progesterone (Oren-Benaroya et al., 2008; Brown et al., 2017). Previous studies suggest that so far unknown components of follicular fluid other than steroids also act on CatSper and that follicular fluid increases [Ca2+]i by mechanisms independent of CatSper (Brown et al., 2017). The latter is supported by our finding that high concentrations of follicular fluid evoke sizeable Ca2+ signals even in CATSPER2–/– sperm. Finally, steroids are not only contained in follicular fluid, but also in the secretions of the cumulus cells and cells lining the oviduct (Libersky and Boatman, 1995; Munuce et al., 2006; Lamy et al., 2016). Similar to follicular fluid, progesterone is the most abundant steroid in the secretion of cumulus cells (Osman et al., 1989), suggesting that also in the vicinity of the egg, steroid activation of CatSper rests predominantly on the action of progesterone. The steroid composition of oviductal fluid is, however, largely unknown in quantitative terms. Thus, at different stages during their journey across the oviduct, steroids other than progesterone might take center stage as to the control of CatSper and, thereby, the swimming behavior of human sperm.

The mechanism of CatSper activation by prostaglandins has remained elusive, except that it does not involve ABHD2, classical G protein-coupled receptors, and second messengers (Schaefer et al., 1998; Lishko et al., 2011; Strünker et al., 2011; Brenker et al., 2012). Instead, prostaglandins activate CatSper rather via an ionotropic mechanism by binding to a subunit or a so far unknown protein associated with the channel complex. Our comprehensive analysis of the structure–activity relationship might enable the development of chemical tools, e.g., prostaglandin photo-affinity labels, to elucidate the prostaglandin-binding site in human sperm as well as the coupling between binding of prostaglandins and channel opening. In contrast to steroids, prostaglandins increase [Ca2+]i in sperm with different potency, but rather similar efficacy, suggesting that this class of ligands evokes rather stereotypical behavioral responses in human sperm. This question as well as whether prostaglandins also modulate the activity of Slo3 and whether or not this might co-determine the potency and efficacy of ligands to elevate [Ca2+]i in sperm remains, however, to be elucidated. It is also unknown whether only steroid or also prostaglandin activation of CatSper triggers oscillations of [Ca2+]i. The first encounter of sperm with prostaglandins is in the ejaculate. The physiological function of prostaglandins in the ejaculate is only ill-defined. The hormones might modulate uterine contractions and, thereby, aid the passive transport of sperm from the uterus to the oviduct. In line with Schaefer et al. (1998), we found that in the ejaculate, the action of prostaglandins on CatSper is rather suppressed by Zn2+, which might serve to protect sperm from premature ligand-evoked Ca2+ influx and ensuing behavioral responses. The mechanism underlying the opposing action of prostaglandins and Zn2+ is unknown. Further studies need to address whether Zn2+ impairs the binding of prostaglandins, the coupling of binding into channel gating, or both. The Zn2+ inhibition of prostaglandin activation of CatSper tapers off upon dilution of the seminal fluid, which might ensure that CatSper is activated only when sperm start escaping from the ejaculate into the female genital tract. In fact, the action of Zn2+ in sperm and its role during fertilization are complex and only ill-defined (Allouche-Fitoussi and Breitbart, 2020). It has been reported that seminal Zn2+ decreases sperm motility and that the motility is stimulated only upon its removal (Allouche-Fitoussi and Breitbart, 2020); in sperm purified from the ejaculate, stimulation with low micromolar Zn2+ concentrations evoked hyperactivated motility (Allouche-Fitoussi et al., 2018; Allouche-Fitoussi and Breitbart, 2020). Our results suggest an even more complex control of motility by a Zn2+/prostaglandin interplay, which needs to be scrutinized in future studies that investigate the motility responses of sperm upon dilution from the ejaculate and/or upon stimulation with dilutions of Zn2+/prostaglandin mixtures. Moreover, it needs to be investigated whether Zn2+ also inhibits CatSper in species, in which the channel is insensitive to hormone activation [e.g., mouse (Lishko et al., 2011)], and whether and how relief of CatSper from Zn2+ inhibition affects the swimming behavior of sperm in these species. Prostaglandin activation of CatSper by dilute seminal fluid should rest predominantly on the action of PGE1, considering the high micromolar concentration of PGE1 in the ejaculate and its low nanomolar EC50 (Supplementary Table 3). Similarly, PGEs seem to be the most abundant prostaglandins in oviductal fluid and the secretion of cumulus cells, suggesting that prostaglandin activation of CatSper in the oviduct and close to the egg is largely mediated by PGEs. The concentration of prostaglandins in oviductal fluid is in the nanomolar range (Ogra et al., 1974), whereas their concentration in the cumulus cell secretions is unknown. Of note, both in the oviduct and close to the egg, sperm encounter prostaglandins and steroids at the same time (Schuetz and Dubin, 1981). Prostaglandins and steroids activate CatSper in a strongly synergistic fashion and, thereby, elevate [Ca2+]i to levels that are not reached by each ligand alone (Brenker et al., 2018a). Future studies have to take this synergism into account: it remains to be elucidated how the combined action of steroids and prostaglandins affects human sperm functions, such as the swimming behavior and acrosomal exocytosis, under conditions that experimentally emulate the complex chemical, topographical, and hydrodynamic landscapes of the female genital tract. This might provide further insight into the ligand control of sperm behavior during fertilization.

In a nutshell, the results presented here underscore that fertilization is orchestrated by a complex action of steroids and prostaglandins, controlling the activity of CatSper. The precise role of these hormones during fertilization has, however, not been definitely established (Baldi et al., 2009; Tamburrino et al., 2020). We propose that at the beginning of their journey across the genital tract, i.e., in the vagina and uterus, sperm are exposed primarily to high concentrations of prostaglandins rather than steroids acting on CatSper. In the oviduct, yet, still rather afar from the egg, low concentrations of both hormones might act in concert to control the activity of CatSper, whereas at the site of fertilization, steroids present at high concentrations rather than prostaglandins take center stage as to the control of CatSper and, thereby, the function of sperm (Supplementary Figure 5).

Materials and Methods

Semen Samples

Semen samples were obtained from normozoospermic (according to WHO) volunteers (donors) and CATSPER2–/– patients (see Schiffer et al., 2020 for more details) with prior written consent and under approval from the ethical committees of the medical association Westfalen-Lippe and the medical faculty of the University of Münster (reference number: 4INie). Semen samples were produced by masturbation and ejaculated into plastic containers. The samples were allowed to liquefy for 15∼30 min at 37°C, and motile sperm were purified by a swim-up procedure. Of note, performing the swim-up procedure with ejaculates from CATSPER2–/– patients yields morphologically normal sperm displaying rather normal basal motility (see also Supplementary Movie EV9 in Schiffer et al., 2020). For swim-up, liquefied semen (0.5–1 ml) was directly layered in a 50-ml Falcon tube below 4 ml of human tubal fluid (HTF) medium, containing (in mM) the following: 97.8 NaCl, 4.69 KCl, 0.2 MgSO4, 0.37 KH2PO4, 2.04 CaCl2, 0.33 Na-pyruvate, 21.4 lactic acid, 4 NaHCO3, 2.78 glucose, and 21 HEPES, pH 7.35 (adjusted with NaOH). Alternatively, the liquefied semen was diluted 1:10 with HTF, and sperm, somatic cells, and cell debris were pelleted by centrifugation at 700 × g for 20 min (37°C). The pellet was resuspended in the same volume HTF, 50 ml Falcon tubes were filled with 5 ml of the suspension, and cells were pelleted by centrifugation at 700 × g for 5 min (37°C). In both cases, motile sperm were allowed to swim up into HTF for 60–90 min at 37°C. Sperm were washed two times by centrifugation at 700 × g for 20 min at 37°C and resuspended in HTF at a density of 1 × 107 sperm/ml. Except for the experiments investigating the action of Zn2+, the HTF was fortified with human serum albumin (3 mg/ml) (HTF+).

Measurement of Changes in [Ca2+]i and pHi

Experiments with swim-up sperm from donors and CATSPER2–/– patients were performed under exactly the same experimental conditions, ensuring the direct comparability of results. Changes in [Ca2+]i were measured in 384 multiwell plates in a fluorescence plate reader (FLUOstar Omega, BMG Labtech, Ortenberg, Germany) at 30°C as previously described (Schiffer et al., 2014). To investigate the action of Zn2+, sperm in HTF were loaded with the fluorescent Ca2+ indicator Fluo-4-AM (5 μM) for 45 min at 37°C. For all the other experiments, sperm in HTF+ were loaded with Fluo-4-AM for 20 min at 37°C. After incubation, excess dye was removed by centrifugation (700 × g, 5 min, room temperature) and sperm were resuspended in HTF at a concentration of 5 × 106/ml. Each well was filled with 50 μl of the sperm suspension. Fluorescence was excited at 485 nm and emission was recorded at 520 nm with bottom optics. Changes in Fluo-4 fluorescence are depicted as ΔF/F (%), i.e., the change in fluorescence (ΔF) relative to the mean basal fluorescence (F) before application of buffer or stimuli (25 μl), correcting for intra- and interexperimental variations in basal fluorescence among individual wells. Stimuli and buffer were injected into the wells simultaneously using a multichannel pipette. Each condition was measured in duplicates and the two fluorescence traces were averaged. If feasible, the signal amplitudes were fitted (nonlinear, least squares) using a modified Hill equation to determine the EC50 value. Changes in pHi were measured in sperm loaded in HTF+ with the pH indicator BCECF (5 μM) for 20 min at 37°C. After loading, cells were washed by centrifugation at 700 × g for 5 min at 37°C and resuspended in HTF at a concentration of 2 × 107/ml. Fluorescence was alternatingly excited with 440 and 485 nm, and the emission was recorded at 510 nm. Changes in the fluorescence ratio (440ex510em/485ex510em) are depicted as ΔR/R (%), i.e., the change in fluorescence ratio (ΔR) relative to the mean basal fluorescence ratio (R) before application of buffer or stimuli (25 μl).

Collection and Handling of Follicular Fluid Samples

Samples were collected from four normoovulatory women (age 30–32, BMI ≤ 25 kg/m2, no diagnosis of polycystic ovary syndrome) undergoing ICSI (intracytoplasmatic sperm injection) after ovarian gonadotropin stimulation at the University Hospital in Münster with prior written informed consent under approval from the ethical committees of the medical association Westfalen-Lippe and the medical faculty of the University of Münster (reference number: 1IX Greb 1). All women were treated with 10–14 days of GnRH agonist alone followed by adding a variable dose of 100–300 IU FSH to achieve a controlled ovarian hyperstimulation. Follicular fluid was collected only from large follicles (16–20 mm) 35–36 h after application of 6,500 IU recombinant hCG (Ovitrelle, Merck-Serono, Geneva, Switzerland). Follicular fluid was aspirated using a trans-vaginal single lumen follicle aspiration needle (Gynetics, Gynemed, Lensahn, Germany) filled with 1 ml flushing medium (Gynemed) under ultrasonographic guidance. The follicular fluid from multiple follicles from each patient was pooled and transferred to a 50-ml Falcon tube and placed on ice. After collection, the pooled samples were centrifuged at 1,500 × g for 15 min at 4°C to remove cells and debris. The collected supernatant was aliquoted and stored at –20°C.

For comparison, samples were collected from 10 normoovulatory women (age 38–42) undergoing ICSI without ovarian gonadotropin stimulation (natural cycle ICSI) due to male infertility at the University Hospital in Bern with prior written informed consent under approval from the ethical committees of the cantonal ethical committee of Bern, Switzerland (reference: 2020-01682). Serum luteinizing hormone (LH) and 17β-estradiol (E2) levels were monitored throughout the cycle until the diameter of the follicle reached at least 18 mm. At this stage, the E2 concentration was generally above 800 pmol/l, and 5,000 IU of hCG (Predalon®, MSD Merck Sharp & Dohme GmbH, Lucerne, Switzerland) was administered 36 h prior to oocyte retrieval. Follicle aspiration for oocyte retrieval was performed without anesthesia. The obtained single follicle fluids were clarified by two-step centrifugation at 600 × g for 10 min and then at 1,300 × g for a further 10 min. The obtained supernatants were stored at –80°C until the analyses of hormones were performed.

Collection and Handling of Human Seminal Fluid

After liquefaction, 100 μl of the ejaculate was diluted with 700 μl HTF. The sample was centrifuged (700 × g, 20 min, room temperature) to pellet cells and debris. The supernatant was collected and evaluated for the presence of sperm. In case of cellular contamination, the centrifugation step and supernatant collection was repeated until no more sperm were present. The seminal fluid was aliquoted and stored at –20°C.

Preparation of Prostaglandin Stock Solutions

Prostaglandins were obtained from Cayman Chemical (Ann Arbor, MI, United States). Most of the prostaglandins were obtained as lyophilized powder, from which stock solutions of 20 mM in DMSO were prepared. The stock solutions were aliquoted and stored at –20°C. In case prostaglandins were delivered as stock solutions in a solvent different from DMSO, the solvent was evaporated under a stream of nitrogen and the solute was directly resuspended in DMSO to yield a 20-mM stock solution that was aliquoted and stored at –20°C.

Preparation of Steroid Stock Solutions

Steroids were obtained as powder from the companies indicated below. The steroids were dissolved in DMSO at a concentration of 20 mM, aliquoted, and stored at –20°C.

| Steroid | Company | Steroid | Company |

| Pregnenolone | Sigma | DHEA | Sigma |

| Progesterone | Sigma | Androstenedione | Sigma |

| Deoxycorticosterone | Steraldoids | Estrone | Merck |

| Corticosterone | Sigma | Androstenediol | Sigma |

| 17-OH-pregnenolone | Sigma | Testosterone | Sigma |

| 17-OH-progesterone | Sigma | Estradiol | Sigma |

| 11-Deoxycortisol | Merck | PGE1 | Cayman Chemical |

| Cortisol | Sigma | DHT | Sigma |

LC-MS/MS Methods, Reagents, and Calibrators—Analyzing the Steroid Profile of FF

The steroid hormones were determined by LC-MS/MS as described (Kulle et al., 2010, 2013; Reinehr et al., 2020). In brief, aliquots of FF samples, calibrator, and controls with a volume of 0.05 ml were combined with the internal standard mixture to monitor recovery. All samples were extracted using Oasis MAX SPE system plates (Waters, Milford, MA, United States). Extracts of estrogens were reduced to dryness under oxygen-free nitrogen (40°C) and the residues were derivatized with dansyl chloride. LC-MS/MS was performed using a Waters Quattro Premier/XE triple-quadrupole mass spectrometer connected to a Waters Acquity (Waters). The chromatographic separation was carried out using an UPLC system, which is connected to a Quattro Premier/XE triple Quad mass spectrometer (Waters). A Waters Acquity UPLC BEH C18 column (1.7 μm, 100 × 2.1) was used at a flow rate of 0.4 ml/min at 50°C. Water (A) and acetonitrile (B) with 0.01% formic acid were used as mobile phase. Two mass transitions were monitored. The following optimized voltages were used: capillary voltage 3.5 kV, cone voltage 28–33 V, collision energy 18–25 eV, dwell time 0.01–0.08 s depending on the steroid, source temperature 120°C, and desolvation temperature 450°C. Argon was used as collision gas. Data were acquired with MassLynx 4.1 software and quantification was performed by QuanLynx software (Waters). During all the analyses, the ambient temperature was kept at 21°C by air conditioning.

Quantification of the Follicular Fluid Dilution Factor by LC-MS

Follicular fluid is diluted during the collection with washing medium, which contains the synthetic pH buffer HEPES. To determine the dilution factor of follicular fluid, we quantified the concentration of HEPES both in the washing medium and in the follicular fluid. The HEPES concentration in follicular fluid was determined by quenching with acetonitrile/water (1:1) in a ratio of 1:3 for protein precipitation [solvents were purchased in LC-MS grade: water, formic acid (VWR Chemicals, Langenfeld, Germany) and acetonitrile (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Schwerte, Germany)]. After storing in a water/ice bath (10 min, 0°C), the suspension was centrifuged (10 min, 4°C, 16,000 rpm) and the supernatant was filtrated using a syringe filter (H-PTFE, 0.2 μm pore size, 13 mm membrane diameter, Macherey-Nagel, Düren, Germany). The filtrate was diluted with water (3:50) and different concentrations of HEPES were added as a standard to aliquots of the solution. To determine the HEPES concentration in the washing medium, it was filtrated using a syringe filter. The filtrate was diluted with water (1:100) and different HEPES concentrations were added as a standard. Samples were prepared in triplicates and analyzed with the LC-MS method (Borgel et al., 2019). Peaks for HEPES were integrated using the extracted ion chromatograms ([M-H]– with 237.0915 ± 0.01 Da), and the HEPES concentrations in follicular fluid and washing medium were interpolated. Finally, the steroid concentrations determined in follicular fluid were corrected for the dilution with washing medium, yielding the true steroid concentration in crude follicular fluid. HPLC-DAD: solvent rack (SRD 3600); pump (DGP-3600RS); autosampler (WPS-3000RS); column oven (TCC-3000RS); precolumn: Phenomenex security guard TM cartridge C18 (4.0 × 2.0 mm, 4.0 μm); column: Phenomenex Synergi Hydro RP (50 × 2.1 mm, 2.6 μm); temperature 30°C and DAD-detector (DAD-3000RS). The LC system was coupled with a micrOTOF-Q II (Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany). The ESI-qTOF was operated in negative ion polarity in the full scan mode (m/z = 70–700) with the following settings: capillary voltage 4,500 V, end plate offset -500 V, collision cell RF 300.0 Vpp, nebulizer 2.0 bar, dry heater 200°C, and dry gas 9.0 L/min. Data handling and control of the system were realized with the software Data Analysis and Hystar from Bruker Daltonics. The calibration of the TOF spectra was achieved by injection of LiHCO2 (isopropanol/bidist. water 1:1, 10 mM) via a 20-μl sample loop within each LC run at 9.0–9.2 min. LC parameters: solvent A: water/acetonitrile 90:10 + 0.1% HCO2H; solvent B: acetonitrile/water 90:10 + 0.1% HCO2H; pump 1: flow rate: 0–7 min: 0.4 ml/min, 7–9.9 min: 0.6 ml/min, 9.9–10.0 min: 0.4 ml/min; gradient elution: (A %): 0–5 min: gradient from 100 to 0%, 5–6.5 min: 0%, 6.5–7 min: gradient from 0 to 100%, 7–10 min: 100% (v/v).

Data Analysis and Statistics

Data were analyzed using Microsoft Excel, GraphPad Prism 5, and OriginPro 2020 (OriginLab, Northampton, MA, United States). Data are shown as mean ± standard deviation (SD) with “n” referring to the number of independent experiments performed with sperm samples from at least two different donors or CATSPER2–/– patients. We did not perform tests for statistical significance, because we identified no set of data where this would have been meaningful and/or required to scrutinize the conclusion(s) drawn from it.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in the study are included in the article/Supplementary Material, further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding authors.

Ethics Statement

The studies involving human participants were reviewed and approved by Ethical Committees of the Medical Association Westfalen-Lippe and the Medical Faculty of the University of Münster (reference number: 4INie and 1IX Greb 1) and ethical committees of the Cantonal Ethical Committee Bern, Switzerland (reference: 2020-01682). The patients/participants provided their written informed consent to participate in this study.

Author Contributions

CBr and TSt conceived the project. JJ, CBi, TSc, IW, FB, DS, AS, AK, PH, MW, BW, VN, TSt, and CBr designed the research; performed the experiments, acquired, analyzed, and/or interpreted the data. JJ, TSt, and CBr drafted the manuscript. All authors revised the manuscript critically for important intellectual content and approved the manuscript for publication.

Conflict of Interest

Since this study, author AS was employed by MVZ Regensburg BmbH; this company was not involved in the study or its design. The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s Note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

Acknowledgments

We thank Sabine Forsthoff, Jolanta Körber-Naprodzka, and Joachim Esselmann for technical support.

Footnotes

Funding. This work was supported by the German Research Foundation (CRU326 to TS and CBr; GRK 2515 to TS and BW), and the Interdisciplinary Center for Clinical Research, Münster (IZKF; Str/014/21 to TS).

Supplementary Material

The Supplementary Material for this article can be found online at: https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.699554/full#supplementary-material

References

- Aitken R. J., Kelly R. W. (1985). Analysis of the direct effects of prostaglandins on human sperm function. J. Rep. Fertil 73 139–146. 10.1530/jrf.0.0730139 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alasmari W., Barratt C. L., Publicover S. J., Whalley K. M., Foster E., Kay V., et al. (2013). The clinical significance of calcium-signalling pathways mediating human sperm hyperactivation. Hum. Rep. 28 866–876. 10.1093/humrep/des467 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alexander N. J., Kim H. K., Blye R. R., Blackmore P. F. (1996). Steroid specificity of the human sperm membrane progesterone receptor. Steroids 61 116–125. 10.1016/0039-128x(95)00202-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouche-Fitoussi D., Bakhshi D., Breitbart H. (2018). Signaling pathways involved in human sperm hyperactivated motility stimulated by Zn2 +. Mol. Rep. Dev. 85 543–556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Allouche-Fitoussi D., Breitbart H. (2020). The role of zinc in male fertility. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 21:7796. 10.3390/ijms21207796 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avenarius M. R., Hildebrand M. S., Zhang Y., Meyer N. C., Smith L. L., Kahrizi K., et al. (2009). Human male infertility caused by mutations in the CATSPER1 channel protein. Am. J. Hum. Genet. 84 505–510. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.03.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Avidan N., Tamary H., Dgany O., Cattan D., Pariente A., Thulliez M., et al. (2003). CATSPER2, a human autosomal nonsyndromic male infertility gene. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 11 497–502. 10.1038/sj.ejhg.5200991 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi E., Casano R., Falsetti C., Krausz C., Maggi M., Forti G. (1991). Intracellular calcium accumulation and responsiveness to progesterone in capacitating human spermatozoa. J. Androl. 12 323–330. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baldi E., Luconi M., Muratori M., Marchiani S., Tamburrino L., Forti G. (2009). Nongenomic activation of spermatozoa by steroid hormones: facts and fictions. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 308 39–46. 10.1016/j.mce.2009.02.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bedu-Addo K., Barratt C. L., Kirkman-Brown J. C., Publicover S. J. (2007). Patterns of [Ca2 + ]i mobilization and cell response in human spermatozoa exposed to progesterone. Dev. Biol. 302 324–332. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2006.09.040 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bendvold E., Gottlieb C., Svanborg K., Bygdeman M., Eneroth P. (1987). Concentration of prostaglandins in seminal fluid of fertile men. Int. J. Androl. 10 463–469. 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1987.tb00220.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore P. F., Beebe S. J., Beebe S. J., Alexander N. (1990). Progesterone and 17 alpha-hydroxyprogesterone. novel stimulators of calcium influx in human sperm. J. Biol. Chem. 265 1376–1380. 10.1016/s0021-9258(19)40024-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blackmore P. F., Fisher J. F., Spilman C. H., Bleasdale J. E. (1996). Unusual steroid specificity of the cell surface progesterone receptor on human sperm. Mol. Pharmacol. 49 727–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Borgel F., Galla F., Lehmkuhl K., Schepmann D., Ametamey S. M., Wünsch B. (2019). Pharmacokinetic properties of enantiomerically pure GluN2B selective NMDA receptor antagonists with 3-benzazepine scaffold. J. Pharm. Biomed. Anal. 172 214–222. 10.1016/j.jpba.2019.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenker C., Goodwin N., Weyand I., Kashikar N. D., Naruse M., Krähling M., et al. (2012). The CatSper channel: a polymodal chemosensor in human sperm. EMBO J. 31 1654–1665. 10.1038/emboj.2012.30 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenker C., Rehfeld A., Schiffer C., Kierzek M., Kaupp U. B., Skakkebæk N. E., et al. (2018a). Synergistic activation of CatSper Ca2 + channels in human sperm by oviductal ligands and endocrine disrupting chemicals. Hum. Rep. 33 1915–1923. 10.1093/humrep/dey275 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenker C., Schiffer C., Wagner I. V., Tüttelmann F., Röpke A., Rennhack A., et al. (2018b). Action of steroids and plant triterpenoids on CatSper Ca(2+) channels in human sperm. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 115 E344–E346. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brenker C., Zhou Y., Müller A., Echeverry F. A., Trötschel C., Poetsch A., et al. (2014). The Ca2 + -activated K+ current of human sperm is mediated by Slo3. Elife 3:e01438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. G., Costello S., Kelly M. C., Ramalingam M., Drew E., Publicover S. J., et al. (2017). Complex CatSper-dependent and independent [Ca2 + ]i signalling in human spermatozoa induced by follicular fluid. Hum. Rep. 32 1995–2006. 10.1093/humrep/dex269 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. G., Miller M. R., Lishko P. V., Lester D. H., Publicover S. J., Barratt C. L. R., et al. (2018). Homozygous in-frame deletion in CATSPERE in a man producing spermatozoa with loss of CatSper function and compromised fertilizing capacity. Hum. Rep. 33 1812–1816. 10.1093/humrep/dey278 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brown S. G., Publicover S. J., Barratt C. L. R., Martins da Silva S. J. (2019). Human sperm ion channel (dys)function: implications for fertilization. Hum. Rep. Update. 25 758–776. 10.1093/humupd/dmz032 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bygdeman M., Samuelsson B. (1966). Analyses of prostaglandins in human semen. prostaglandins and related factors 44. Clin. Chim. Acta 13 465–474. 10.1016/0009-8981(66)90238-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cooper T. G., Jockenhövel F., Nieschlag E. (1991). Variations in semen parameters from fathers. Hum. Rep. 6 859–866. 10.1093/oxfordjournals.humrep.a137441 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- de los Santos M. J., García-Láez V., Horcajadas J. A., Martínez-Conejero J. A., Esteban F. J., Esteban F. J., et al. (2012). Hormonal and molecular characterization of follicular fluid, cumulus cells and oocytes from pre-ovulatory follicles in stimulated and unstimulated cycles. Hum. Reprod 27 1596–1605. 10.1093/humrep/des082 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gerozissis K., Jouannet P., Soufir J. C., Dray F. (1982). Origin of prostaglandins in human semen. J. Reprod Fertil 65 401–404. 10.1530/jrf.0.0650401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hansen C., Srikandakumar A., Downey B. R. (1991). Presence of follicular fluid in the porcine oviduct and its contribution to the acrosome reaction. Mol. Reprod Dev. 30 148–153. 10.1002/mrd.1080300211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harper C. V., Kirkman-Brown J. C., Barratt C. L., Publicover S. J. (2003). Encoding of progesterone stimulus intensity by intracellular [Ca2 + ] ([Ca2 + ]i) in human spermatozoa. Biochem. J. 372(Pt. 2) 407–417. 10.1042/bj20021560 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hildebrand M. S., Avenarius M. R., Fellous M., Zhang Y., Meyer N. C., Auer J., et al. (2010). Genetic male infertility and mutation of CATSPER ion channels. Eur. J. Hum. Genet. 18 1178–1184. 10.1038/ejhg.2010.108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hong C. Y., Chao H. T., Lee S. L., Wei Y. H. (1993). Modification of human sperm function by human follicular fluid: a review. Int. J. Androl. 16 93–96. 10.1111/j.1365-2605.1993.tb01160.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwang J. Y., Mannowetz N., Zhang Y., Everley R. A., Gygi S. P., Bewersdorf J., et al. (2019). Dual sensing of physiologic pH and calcium by EFCAB9 regulates sperm motility. Cell 177 1480–1494.e19. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isidori A., Conte D., Laguzzi G., Giovenco P., Dondero F. (1980). Role of seminal prostaglandins in male fertility. I. relationship of prostaglandin E and 19-OH prostaglandin E with seminal parameters. J. Endocrinol. Invest. 3 1–4. 10.1007/bf03348209 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jaiswal D., Singh V., Dwivedi U. S., Trivedi S., Singh K. (2014). Chromosome microarray analysis: a case report of infertile brothers with CATSPER gene deletion. Gene 542 263–265. 10.1016/j.gene.2014.03.055 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kelly M. C., Brown S. G., Costello S. M., Ramalingam M., Drew E., Publicover S. J., et al. (2018). Single-cell analysis of [Ca2 + ]i signalling in sub-fertile men: characteristics and relation to fertilization outcome. Hum. Reprod 33 1023–1033. 10.1093/humrep/dey096 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilic F., Kashikar N. D., Schmidt R., Alvarez L., Dai L., Weyand I., et al. (2009). Caged progesterone: a new tool for studying rapid nongenomic actions of progesterone. J. Am. Chem. Soc. 131 4027–4030. 10.1021/ja808334f [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirichok Y., Navarro B., Clapham D. E. (2006). Whole-cell patch-clamp measurements of spermatozoa reveal an alkaline-activated Ca2 + channel. Nature 439 737–740. 10.1038/nature04417 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kirkman-Brown J. C., Barratt C. L., Publicover S. J. (2004). Slow calcium oscillations in human spermatozoa. Biochem. J. 378(Pt. 3) 827–832. 10.1042/bj20031368 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krausz C., Bonaccorsi L., Luconi M., Fuzzi B., Criscuoli L., Pellegrini S., et al. (1995). Intracellular calcium increase and acrosome reaction in response to progesterone in human spermatozoa are correlated with in-vitro fertilization. Hum. Reprod 10 120–124. 10.1093/humrep/10.1.120 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulle A. E., Riepe F. G., Melchior D., Hiort O., Holterhus P. M. (2010). A novel ultrapressure liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry method for the simultaneous determination of androstenedione, testosterone, and dihydrotestosterone in pediatric blood samples: age- and sex-specific reference data. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 95 2399–2409. 10.1210/jc.2009-1670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulle A. E., Welzel M., Holterhus P. M., Riepe F. G. (2013). Implementation of a liquid chromatography tandem mass spectrometry assay for eight adrenal C-21 steroids and pediatric reference data. Horm. Res. Paediatr. 79 22–31. 10.1159/000346406 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kushnir M. M., Naessen T., Kirilovas D., Chaika A., Nosenko J., Mogilevkina I. (2009). Steroid profiles in ovarian follicular fluid from regularly menstruating women and women after ovarian stimulation. Clin. Chem. 55 519–526. 10.1373/clinchem.2008.110262 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lamy J., Liere P., Pianos A., Aprahamian F., Mermillod P., Saint-Dizier M. (2016). Steroid hormones in bovine oviductal fluid during the estrous cycle. Theriogenology 86 1409–1420. 10.1016/j.theriogenology.2016.04.086 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Libersky E. A., Boatman D. E. (1995). Progesterone concentrations in serum, follicular fluid, and oviductal fluid of the golden hamster during the periovulatory period. Biol Reprod 53 477–482. 10.1095/biolreprod53.3.477 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishko P. V., Botchkina I. L., Botchkina I. L., Kirichok Y. (2010). Acid extrusion from human spermatozoa is mediated by flagellar voltage-gated proton channel. Cell 140 327–337. 10.1016/j.cell.2009.12.053 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lishko P. V., Botchkina I. L., Kirichok Y. (2011). Progesterone activates the principal Ca2 + channel of human sperm. Nature 471 387–391. 10.1038/nature09767 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luconi M., Bonaccorsi L., Forti G., Baldi E. (2001). Effects of estrogenic compounds on human spermatozoa: evidence for interaction with a nongenomic receptor for estrogen on human sperm membrane. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 178 39–45. 10.1016/s0303-7207(01)00416-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luconi M., Francavilla F., Porazzi I., Macerola B., Forti G., Baldi E. (2004). Human spermatozoa as a model for studying membrane receptors mediating rapid nongenomic effects of progesterone and estrogens. Steroids 69 553–559. 10.1016/j.steroids.2004.05.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luconi M., Muratori M., Forti G., Baldi E. (1999). Identification and characterization of a novel functional estrogen receptor on human sperm membrane that interferes with progesterone effects. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 84 1670–1678. 10.1210/jcem.84.5.5670 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luo T., Chen H. Y., Zou Q. X., Wang T., Cheng Y. M., Wang H. F., et al. (2019). A novel copy number variation in CATSPER2 causes idiopathic male infertility with normal semen parameters. Hum. Reprod 34 414–423. 10.1093/humrep/dey377 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mannowetz N., Miller M. R., Lishko P. V. (2017). Regulation of the sperm calcium channel CatSper by endogenous steroids and plant triterpenoids. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 114 5743–5748. 10.1073/pnas.1700367114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchiani S., Tamburrino L., Benini F., Pallecchi M., Bignozzi C., Conforti A., et al. (2020). LH supplementation of ovarian stimulation protocols influences follicular fluid steroid composition contributing to the improvement of ovarian response in poor responder women. Sci. Rep. 10:12907. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mata-Martinez E., Darszon A., Treviño C. L. (2018). pH-dependent Ca2 + oscillations prevent untimely acrosome reaction in human sperm. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 497 146–152. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.02.042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Miller M. R., Mannowetz N., Iavarone A. T., Safavi R., Gracheva E. O., Smith J. F., et al. (2016). Unconventional endocannabinoid signaling governs sperm activation via sex hormone progesterone. Science 352 555–559. 10.1126/science.aad6887 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Munuce M. J., Quintero I., Caille A. M., Ghersevich S., Berta C. L. (2006). Comparative concentrations of steroid hormones and proteins in human peri-ovulatory peritoneal and follicular fluids. Reprod Biomed Online 13 202–207. 10.1016/s1472-6483(10)60616-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ogra S. S., Kirton K. T., Tomasi T. B., Jr., Lippes J. (1974). Prostaglandins in the human fallopian tube. Fertil Steril 25 250–255. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oren-Benaroya R., Orvieto R., Gakamsky A., Pinchasov M., Eisenbach M. (2008). The sperm chemoattractant secreted from human cumulus cells is progesterone. Hum. Reprod 23 2339–2345. 10.1093/humrep/den265 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Osman R. A., Andria M. L., Jones A. D., Meizel S. (1989). Steroid induced exocytosis: the human sperm acrosome reaction. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 160 828–833. 10.1016/0006-291x(89)92508-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Publicover S. J., Giojalas L. C., Teves M. E., de Oliveira G. S., Garcia A. A., Barratt C. L., et al. (2008). Ca2 + signalling in the control of motility and guidance in mammalian sperm. Front. Biosci. 13:5623–5637. 10.2741/3105 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rehfeld A. (2020). Revisiting the action of steroids and triterpenoids on the human sperm Ca2+ channel CatSper. Mol. Hum. Reprod 26 816–824. 10.1093/molehr/gaaa062 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinehr T., Kulle A., Barth A., Ackermann J., Lass N., Holterhus P. M. (2020). Sex hormone profile in pubertal boys with gynecomastia and pseudogynecomastia. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab 105:dgaa044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rennhack A., Schiffer C., Brenker C., Fridman D., Nitao E. T., Cheng Y. M., et al. (2018). A novel cross-species inhibitor to study the function of CatSper Ca2 + channels in sperm. Br. J. Pharmacol. 175 3144–3161. 10.1111/bph.14355 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rossato M., Ferigo M., Galeazzi C., Foresta C. (2005). Estradiol inhibits the effects of extracellular ATP in human sperm by a non genomic mechanism of action. Purinergic. Signal 1 369–375. 10.1007/s11302-005-1172-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samuelsson B. (1963). Isolation and identification of prostaglandins from human seminal plasma. 18. prostaglandins and related factors. J. Biol. Chem. 238 3229–3234. 10.1016/s0021-9258(18)48651-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez-Cardenas C., Servín-Vences M. R., José O., Treviño C. L., Hernández-Cruz A., Darszon A. (2014). Acrosome reaction and Ca2 + imaging in single human spermatozoa: new regulatory roles of [Ca2 + ]i. Biol. Reprod 91:67. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schaefer M., Hofmann T., Schultz G., Gudermann T. (1998). A new prostaglandin E receptor mediates calcium influx and acrosome reaction in human spermatozoa. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 95 3008–3013. 10.1073/pnas.95.6.3008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer C., Müller A., Egeberg D. L., Alvarez L., Brenker C., Rehfeld A., et al. (2014). Direct action of endocrine disrupting chemicals on human sperm. EMBO Rep. 15 758–765. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffer C., Rieger S., Brenker C., Young S., Hamzeh H., Wachten D., et al. (2020). Rotational motion and rheotaxis of human sperm do not require functional CatSper channels and transmembrane Ca2 + signaling. EMBO J. 39:e102363. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schuetz A. W., Dubin N. H. (1981). Progesterone and prostaglandin secretion by ovulated rat cumulus cell-oocyte complexes. Endocrinology 108 457–463. 10.1210/endo-108-2-457 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seifert R., Flick M., Bönigk W., Alvarez L., Trötschel C., Poetsch A., et al. (2015). The CatSper channel controls chemosensation in sea urchin sperm. EMBO J 34 379–392. 10.15252/embj.201489376 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Servin-Vences M. R., Tatsu Y., Ando H., Guerrero A., Yumoto N., Darszon A., et al. (2012). A caged progesterone analog alters intracellular Ca2 + and flagellar bending in human sperm. Reproduction 144 101–109. 10.1530/rep-11-0268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shimizu Y., Yorimitsu A., Maruyama Y., Kubota T., Aso T., Bronson R. A. (1998). Prostaglandins induce calcium influx in human spermatozoa. Mol. Hum. Reprod 4 555–561. 10.1093/molehr/4.6.555 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith J. F., Syritsyna O., Fellous M., Serres C., Mannowetz N., Mannowetz N., et al. (2013). Disruption of the principal, progesterone-activated sperm Ca2 + channel in a CatSper2-deficient infertile patient. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U.S.A. 110 6823–6828. 10.1073/pnas.1216588110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Strünker T., Goodwin N., Brenker C., Kashikar N. D., Weyand I., Seifert R., et al. (2011). The CatSper channel mediates progesterone-induced Ca2 + influx in human sperm. Nature 471 382–386. 10.1038/nature09769 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburrino L., Marchiani S., Minetti F., Forti G., Muratori M., Baldi E. (2014). The CatSper calcium channel in human sperm: relation with motility and involvement in progesterone-induced acrosome reaction. Hum. Reprod 29 418–428. 10.1093/humrep/det454 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburrino L., Marchiani S., Muratori M., Luconi M., Baldi E. (2020). Progesterone, spermatozoa and reproduction: an updated review. Mol. Cell. Endocrinol. 516:110952. 10.1016/j.mce.2020.110952 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tamburrino L., Marchiani S., Vicini E., Muciaccia B., Cambi M., Pellegrini S., et al. (2015). Quantification of CatSper1 expression in human spermatozoa and relation to functional parameters. Hum. Reprod 30 1532–1544. 10.1093/humrep/dev103 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas P., Meizel S. (1988). An influx of extracellular calcium is required for initiation of the human sperm acrosome reaction induced by human follicular fluid. Gamete Res. 20 397–411. 10.1002/mrd.1120200402 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrezan-Nitao E., Brown S. G., Mata-Martínez E., Treviño C. L., Barratt C., Publicover S. (2021). [Ca2 + ]i oscillations in human sperm are triggered in the flagellum by membrane potential-sensitive activity of CatSper. Hum. Reprod 36 293–304. 10.1093/humrep/deaa302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vastik-Fernandez J., Gimeno M. F., Lima F., Gimeno A. L. (1975). Spontaneous motility and distribution of prostaglandins in different segments of human Fallopian tubes. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol. 122 663–668. 10.1016/0002-9378(75)90067-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walters K. A., Eid S., Edwards M. C., Thuis-Watson R., Desai R., Bowman M., et al. (2019). Steroid profiles by liquid chromatography-mass spectrometry of matched serum and single dominant ovarian follicular fluid from women undergoing IVF. Reprod Biomed Online 38 30–37. 10.1016/j.rbmo.2018.10.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang H., McGoldrick L. L., Chung J. J. (2021). Sperm ion channels and transporters in male fertility and infertility. Nat. Rev. Urol. 18 46–66. 10.1038/s41585-020-00390-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Young S., Krenz H., Tüttelmann F., Röpke A., Krallmann C., et al. (2020). The Ca2 + channel CatSper is not activated by cAMP/PKA signaling but directly affected by chemicals used to probe the action of cAMP and PKA. J. Biol. Chem. 295 13181–13193. 10.1074/jbc.ra120.013218 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Williams H. L., Mansell S., Alasmari W., Brown S. G., Wilson S. M., Sutton K. A., et al. (2015). Specific loss of CatSper function is sufficient to compromise fertilizing capacity of human spermatozoa. Hum. Reprod 30 2737–2746. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]