Abstract

Rationale & Objective

Digital health system tools to support shared decision making and preparation for kidney replacement treatments for patients with chronic kidney disease (CKD) are needed.

Study Design

Descriptive study of the implementation of digital infrastructure to support a patient-centered health system intervention.

Setting & Participants

4 CKD clinics within a large integrated health system.

Exposure

We developed an integrated suite of digital engagement tools to support patients’ shared decision making and preparation for kidney failure treatments. Tools included an automated CKD patient registry and risk prediction algorithm within the electronic health record (EHR) to identify and prioritize patients in need of nurse case management to facilitate shared decision making and preparation for kidney replacement treatments, an electronic patient-facing values clarification tool, a tracking application to document patients’ preparation for treatments, and an EHR work flow to broadcast patients’ treatment preferences to all health care providers.

Outcomes

Uptake and acceptability.

Analytic Approach

Mixed methods.

Results

From July 1, 2017, through June 30, 2018, the CKD registry identified 1,032 patients in 4 nephrology clinics, of whom 243 (24%) were identified as high risk for progressing to kidney failure within 2 years. Kidney Transitions Specialists enrolled 117 (48%) high-risk patients by the end of year 1. The values tool was completed by 30/33 (91%) patients who attended kidney modality education. Nurse case managers used the tracking application for 100% of patients to document 287 planning steps for kidney replacement therapy. Most (87%) high-risk patients had their preferred kidney replacement modality documented and displayed in the EHR. Nurse case managers reported that the tools facilitated their identification of patients needing support and their navigation activities.

Limitations

Single institution, short duration.

Conclusions

Digital health system tools facilitated rapid identification of patients needing shared and informed decision making and their preparation for kidney replacement treatments.

Funding

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Project Program Award (IHS-1409-20967).

Trial registration

ClinicalTrials.gov NCT02722382.

Index Words: Digital infrastructure, health information technology, shared decision making, chronic kidney disease, case management

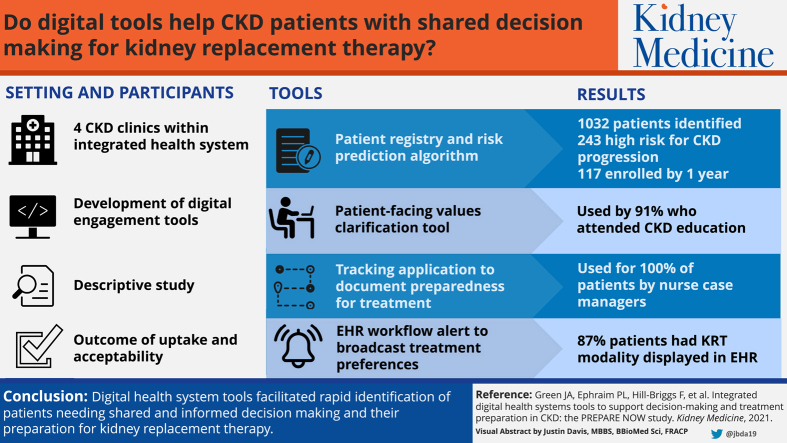

Graphical abstract

Plain-Language Summary.

Digital health system tools to support shared decision making and preparation for kidney failure treatments are needed. We developed an integrated suite of digital engagement tools, including (1) a chronic kidney disease (CKD) registry and risk prediction algorithm to identify and prioritize patients, (2) an electronic patient-facing values clarification tool, (3) a tracking application to document patients’ preparation for treatments, and (4) an electronic work flow to broadcast patients’ treatment preferences to all health care providers. We evaluated the first-year implementation of the use of these tools and found consistent uptake and acceptability by users. This supportive health system infrastructure could have a significant impact on the clinical care of patients with CKD and their outcomes.

More than 30 million people in the United States have chronic kidney disease (CKD), and each year more than 150,000 progress to complete kidney failure.1,2 As CKD progresses toward kidney failure, patients face complex decisions regarding their selection of a treatment modality for life-saving kidney replacement therapy. Treatment modalities, which range from in-center hemodialysis to self-care home dialysis, kidney transplantation, or conservative care, differ with regard to the types of preparation they require, the way they are delivered, patients’ experiences with them, and their associated clinical outcomes. It is widely advocated that patients receive education about all treatment options, engage in shared and informed decision making, and prepare for their desired treatments in a timely manner.3,4 Despite this, evidence suggests that most patients who initiate kidney replacement therapy have a poor understanding of their treatment options before initiating treatment, and many patients initiate hemodialysis urgently, with little or no time to consider treatment alternatives.5

For patients to select treatment modalities that align with their values before kidney failure occurs, they need early identification, advance warning that kidney failure may be imminent, education about their treatment options, and opportunities to examine their personal values and engage in shared and informed decision making about treatments, and they must complete the medical procedures or tests required to ensure that they can initiate timely treatment. In addition, health care providers need to be aware of patients’ treatment preferences. However, patients and providers often report that they lack support to successfully carry out the key steps needed to help patients reach informed decisions and adequately prepare for treatments.6, 7, 8

Health information systems could be leveraged to develop an infrastructure that supports patients’ and providers’ actions as patients prepare for kidney failure treatments.9 However, the design and systematic implementation of integrated digital health system tools to support patients’ preparation for kidney replacement treatment has not been well described. We describe the first-year implementation, uptake, and acceptability of a novel suite of integrated digital health system tools to support patients’ shared and informed decision making and preparation for kidney replacement treatments.

Methods

Overview

We designed and implemented a suite of digital health system tools to support shared and informed decision making and kidney failure treatment preparation for patients with advanced CKD as part of an ongoing pragmatic clinical trial. We conducted a mixed-methods analysis among a small subgroup of early study participants to evaluate the uptake and acceptability of the suite of integrated tools used by nurse case managers.

The PREPARE NOW Study is a 4-year cluster randomized controlled clinical trial (NCT02722382) across 8 nephrology clinics at Geisinger. Four clinics have implemented a multicomponent intervention that comprises new digital health system tools, behavioral support, education, peer support, patient navigation, and nurse case management to create a system of care to help patients with advanced CKD make shared and informed treatment decisions and prepare for kidney failure treatments. Full details of the PREPARE NOW protocol are published elsewhere.10 All study procedures have been approved through a single Institutional Review Board at Duke University (Pro00074588).

Setting

The PREPARE NOW intervention is being implemented within Geisinger, an integrated health system that serves approximately 4.2 million people in Pennsylvania and New Jersey. Geisinger provides comprehensive nephrology care to approximately 4,000 patients with kidney disease, as well as full-service transplant care. Numerous information systems and a culture of clinical innovation provide a backbone for Geisinger health information systems, including an Epic electronic health record (EHR), a web-based patient portal, a billing collections system, and more than a decade of experience working with patients and care team members to develop product innovation efforts. A comprehensive enterprise-level data warehouse updates every 24 hours with feeds from multiple source systems, including the EHR, financial decision support, claims, patient satisfaction, and third-party reference data sets.

Innovation in partnership with these systems occurs through the Geisinger Steele Institute for Health Innovation. The Institute’s Product Innovation development team works in partnership with clinical units to deploy design thinking, health information technology, and human-centered design strategies to develop new products, services, processes, and innovative systems to support Geisinger’s mission of enhanced value in health care.

Elements of PREPARE NOW Digital Health System Tools

Overview

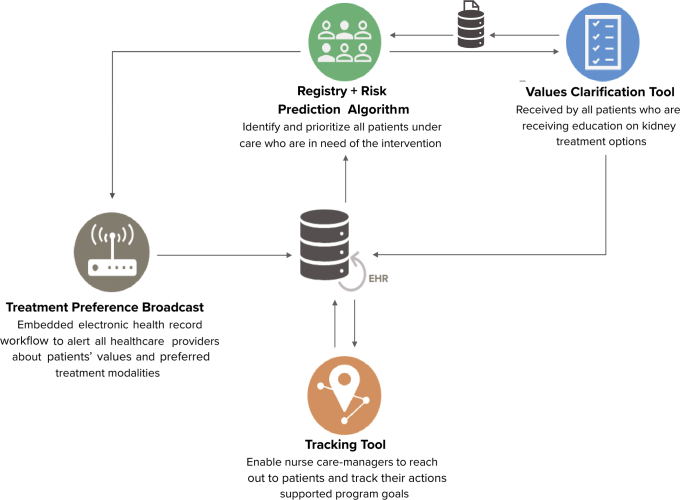

PREPARE NOW digital health system tools build on Geisinger core information systems and are integrated with the EHR to enhance clinical work flows. The suite of tools includes (1) a system-wide CKD patient registry coupled with an automated risk prediction algorithm that identifies and prioritizes all patients under nephrology care who are in need of the intervention, (2) a patient-facing electronic values clarification tool that all patients who are receiving education on kidney failure treatment options receive, (3) a navigation and tracking application to help nurse case managers reach out to patients and track their actions supporting PREPARE NOW goals, and (4) an embedded EHR work flow to alert providers throughout the health system about patients’ values and preferred kidney failure treatment modalities (Fig 1). These tools are embedded within existing case management work flows that include contact with patients and providers in-person, over the telephone, or within the EHR. Patient assessments occur at least every 6 months, with more frequent contact depending on patient needs.

Figure 1.

Integrated PREPARE NOW digital health system tools. Abbreviation: EHR, electronic health record.

CKD Registry and Prediction Tool for Population Risk Stratification

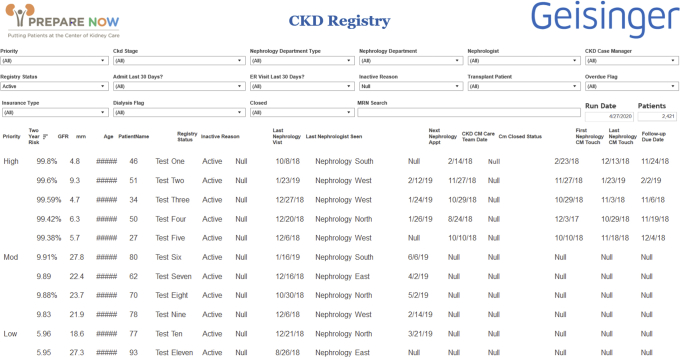

The CKD registry is designed to identify patients at risk for CKD progression and those who can most benefit from interventions to prepare them to make kidney failure treatment decisions. The registry identifies nephrology patients (≥1 office visit in the past year) who are categorized as “very high risk” prognosis based on Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) staging categories (stages G3aA3, G3bA2-A3, G4A1-A3, and G5A1-A3).4 Outpatient data from the EHR are processed nightly to identify qualifying patients using Geisinger’s Apache Hadoop data warehouse and the Tableau analytics software. The most recent outpatient serum chemistry values within 2 years and most recent urine chemistry value ever are used to calculate eligibility. Patients with acute kidney injury are not included unless they meet other registry criteria. Patients remain on the registry until 6 months after they transition to kidney failure or if they no longer meet inclusion criteria, at which point they become inactive. They can be reactivated at any time if they meet inclusion criteria. Targeted outreach occurs to facilitate scheduling of patients who become inactive due to not having an appointment in the preceding year. Patients not followed up in nephrology are captured by a best practice alert prompting referral to nephrology when estimated glomerular filtration rate (eGFR) decreases to <30 mL/min/1.73 m2.

To further identify patients on the registry who are more likely to progress to kidney failure, the internationally validated Kidney Failure Risk Equation11,12 is applied nightly to medical records of patients identified in the registry. This provides a score to each patient based on age, sex, and laboratory values, including eGFR, urinary albumin-creatinine ratio, serum albumin, phosphorus, bicarbonate, and calcium. Patients with scores of <6%, 6% to 10%, and >10% are categorized as being at low, moderate, or high risk for progressing to kidney failure within 2 years, in accordance with validated standards.11, 12, 13

A nurse case manager (called a Kidney Transitions Specialist) reviews a data-driven list of patients on the registry that also displays the score categorization. This list allows Kidney Transitions Specialists to identify patients at highest risk for progression and therefore with the most urgent need for interventions to ensure their shared and informed decision making and kidney failure treatment preparation (Fig 2). Kidney Transitions Specialists prioritize all high-risk patients for enrollment in nurse case management. Low- or moderate-risk patients are triaged to receive early education on kidney disease self-management but are not enrolled in case management unless they progress to high risk. Enrollment can occur at the time of an office visit or over the telephone, depending on urgency.

Figure 2.

Chronic kidney disease (CKD) registry. Abbreviations: CM, case management; ER, emergency room; GFR, glomerular filtration rate.

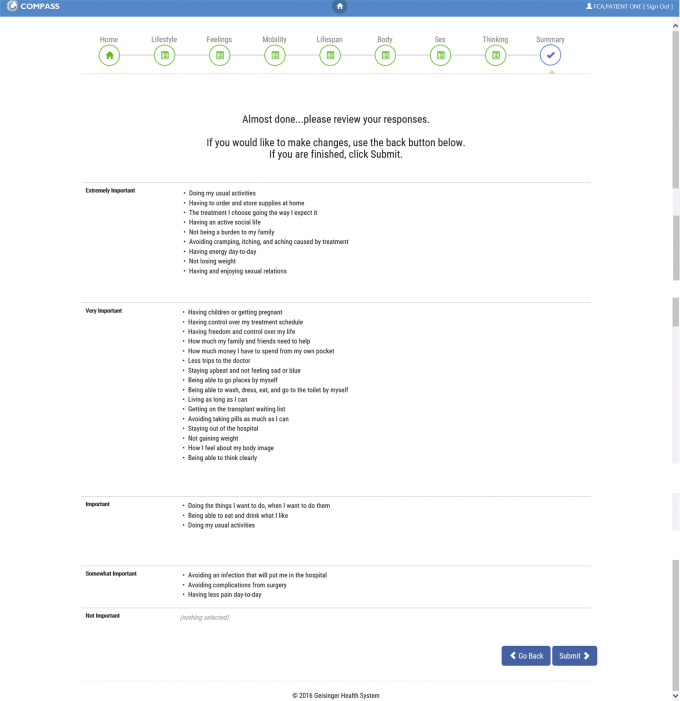

Patient-Facing Values Clarification Tool

The electronic values clarification tool helps patients consider how various treatments for kidney failure might align with their personal values. This web-based tool is programmed to be used on a tablet or can be launched online through the electronic health portal before or at the beginning of a nurse-led 2-hour group class or 1:1 counseling session about kidney failure treatments. Patients are asked to rate the importance of 30 values previously identified as important to patients with kidney disease14,15 on a 5-point Likert scale from not important to extremely important. Patients complete the tool and then receive a printout of their responses (Fig 3). They are encouraged to refer to their answers to these questions throughout the education session and after so that they can consider how potential treatment options align with their personal values. Patients are able to take this printout home with them to consider as they reflect on education they have received and as they interact with health care providers who will engage in discussions promoting shared and informed decision making over the coming months. Results are also uploaded into EHR flowsheets for providers to view. Patients can complete the tool again as needed.

Figure 3.

Patient values clarification tool.

Navigation and Tracking Application Promoting Actions to Help Patients Prepare for Their Preferred Treatments

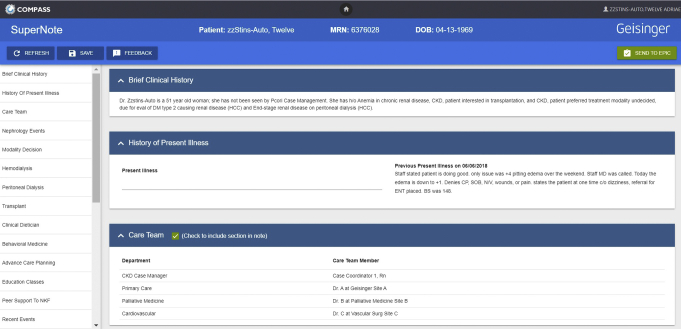

We developed an electronic application integrated with Epic that Kidney Transitions Specialists use to prompt them to engage in shared and informed decision making (by inquiring whether discussions have occurred and whether patients have declared their preferences for treatments) and to prompt their navigation of patients to complete necessary steps (eg, referrals to kidney transplantation center) that will enable patients to receive their preferred treatments. The navigation and tracking application serves as a note within the EHR. Nurse case managers can select a series of drop-down boxes to indicate whether they have worked with patients to complete a number of activities relevant to treatment decision making, including education and planning steps to prepare for treatment initiation (Fig 4). The sections are updated during each patient encounter and then shared with members of the health care team.

Figure 4.

Kidney Care Transitions Specialist tracking tool. Abbreviations: BS, blood sugar; CKD, chronic kidney disease; CP, chest pain ; DM, diabetes mellitus; ENT, ear nose throat; HCC, hierarchical condition category; N/V, nausea/vomiting; SOB, short of breath.

EHR Work Flow Broadcasting Patients’ Treatment Preferences to Health Care Providers Throughout the Health System

When patients have selected a treatment modality in advance, it is important that all their health care providers are aware so that they can align treatment plans with patients’ preferences. Using existing capabilities within Epic, we created unique diagnosis code terminology indicating patients’ preferred kidney failure treatment modality, listed as “CKD, patient preferred treatment modality: in-center hemodialysis, home hemodialysis, peritoneal dialysis, or undecided” and/or “CKD, patient interested in transplant.” These terms were submitted to and adopted by the Intelligent Medical Objects database and map to standard International Classification of Diseases terminology for CKD. These diagnosis codes can be selected by any health care team member and are posted to the problem list on each patient’s chart, making them highly visible during any patient encounters. A comment field is available to document additional details about a patient’s choice, including degrees of uncertainty. In addition, an alert banner fires within the EHR notifying providers that a patient is enrolled in the Kidney Transitions program. The banner includes a direct link to the problem list to facilitate viewing of treatment preferences.

Data Collection and Analysis

We conducted a mixed-methods analysis to evaluate the uptake and acceptability16 of the PREPARE NOW digital infrastructure over the first 12 months of implementation in 4 CKD clinics at Geisinger. We describe characteristics of the CKD registry (number of patient registrants and distribution of kidney failure risk) within PREPARE NOW clinics. To quantify infrastructure uptake, we describe the number of high-risk patients enrolled in case management, the number of patients completing the values clarification tool among those who attended kidney modality education during the study period, Kidney Transitions Specialist use of the navigation and tracking application to document planning steps for kidney replacement therapy, and use of diagnosis codes to broadcast patients’ preferred therapies on problem lists.

To characterize the populations of patients who are eligible and enrolled in case management, we summarize the demographic and clinical characteristics of these patients at the time they enter the registry, including overall, by whether they enrolled, and by whether they received kidney failure treatment modality education. These demographic and clinical characteristics include age, sex, risk score, eGFR, Charlson Comorbidity Index score, diabetes, cardiovascular disease, years in nephrology care, and total time on the registry between intervention rollout and the end of the 12-month window. Continuous measures are summarized as median and interquartile range, and categorical measures are summarized as count and percentage. To assess differences in demographics, Kruskal-Wallis tests and χ2 tests were implemented for continuous and categorical measures, respectively.

In addition, we asked the 2 Kidney Transitions Specialists who delivered the intervention to rate the acceptability of the tools in terms of ease of use (ie, “I find the [CKD registry/values tool/tracking application/problem list documentation] easy to use”) and helpfulness (ie, “the CKD registry helps me prioritize patients in the greatest need of care,” “the values [clarification] tool helps me guide patient decision making,” “the [tracking application] helps me in tracking my patient care,” and “the problem list documentation [and preference broadcasting] helps me communicate treatment preferences to other providers”), with responses for each assessed using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree. Additionally, using an open-comment text field, we asked them to qualitatively describe: (1) what they liked most and least about each tool, (2) suggested changes, and (3) how the tools helped them provide better care.

Results

The PREPARE NOW digital infrastructure was fully implemented in July 2017. All elements of the infrastructure were implemented simultaneously and have been used by 2 Kidney Transitions Specialists practicing within 4 Geisinger CKD clinics since its implementation.

Registry Implementation and Population Risk Stratification

From July 1, 2017, through June 30, 2018, the disease registry identified 1,032 patients in the 4 PREPARE NOW clinics who met inclusion criteria. At entry, 819 (79%), 69 (7%), and 144 (14%) were identified as low, moderate, or high risk for progressing to kidney failure within 2 years (Table 1). During the first 12 months, an additional 99 transitioned to high risk for a total of 243 eligible for enrollment in case management. Kidney Transitions Specialists enrolled 117 (48%) high-risk patients by the end of year 1. Characteristics of the total eligible population are shown in Table 2. Enrolled patients were more likely to have lower eGFRs, higher kidney failure risk, and more time on the registry.

Table 1.

CKD Stage and Risk for Kidney Failure at Entry Among Registry Participants

| CKD Stage | All Patients |

Risk at Entry |

||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Low |

Moderate |

High |

||||||

| No. (%) | Risk Score (median [IQR]) | No. (%) | Risk Score (median [IQR]) | No. (%) | Risk Score (median [IQR]) | No. (%) | Risk Score (median [IQR]) | |

| All stages | 1,032 (100%) | 0.02 [0.01-0.05] | 819 (79.4%) | 0.01 [0.01-0.03] | 69 (6.7%) | 0.07 [0.07-0.08] | 144 (13.9%) | 0.21 [0.13-0.37] |

| No. missing | — | 29 | — | 29 | — | 0 | — | 0 |

| Stage 3b | 583 (56.5%) | 0.01 [0.01-0.02] | 566 (97.1%) | 0.01 [0.01-0.02] | 11 (1.9%) | 0.08 [0.06-0.08] | 6 (1.0%) | 0.16 [0.13-0.25] |

| No. missing | -- | 1 | — | 1 | — | 0 | — | 0 |

| Stage 4 | 407 (39.4%) | 0.05 [0.03-0.10] | 249 (61.2%) | 0.03 [0.02-0.04] | 58 (14.2%) | 0.07 [0.07-0.08] | 100 (24.6%) | 0.18 [0.13-0.26] |

| No. missing | — | 24 | — | 24 | — | 0 | — | 0 |

| Stage 5 | 39 (3.8%) | 0.46 [0.30-0.68] | 1 (2.6%) | — | 0 (0.0%) | — | 38 (97.4%) | 0.46 [0.30-0.68] |

| No. missing | — | 1 | — | 1 | — | — | — | 0 |

| Not recorded at entry | 3 (0.3%) | — | 3 (100.0%) | — | 0 (0.0%) | — | 0 (0.0%) | — |

| No. missing | — | 3 | — | 3 | — | — | — | — |

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; IQR, interquartile range.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Enrolled Versus Not Enrolled in Kidney Case Management

| Characteristic | All Eligible Patients (N = 243) | Enrollment Status |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Enrolled (n = 117) | Not Enrolled (n = 126) | Pa | |||

| Age, y | 72 [59-81] | 71 [60-80] | 75 [59- 82] | 0.30 | |

| Female sex | 120 (49%) | 50 (43%) | 70 (56%) | 0.05 | |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 22.9 [17.0-27.8] | 21.4 [16.6-25.7] | 24.1 [17.5-29.6] | 0.04 | |

| KFRE score | 0.13 [0.06-0.24] | 0.16 [0.10-0.28] | 0.08 [0.04-0.21] | <0.0001 | |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | 5 [4-7] | 6 [4-7] | 5 [4-7] | 0.71 | |

| Diabetes | 160 (66%) | 83 (71%) | 77 (61%) | 0.11 | |

| Cardiovascular disease | 144 (59%) | 65 (56%) | 79 (63%) | 0.26 | |

| Time on registry as of June 30, 2018 | 8 [8-9] | 8 [8-9] | 8 [7-8] | <0.001 | |

| 1-3 mo | 20 (8.2%) | 2 (1.7%) | 18 (14.3%) | ||

| 4-6 mo | 22 (9.1%) | 12 (10.3%) | 10 (7.9%) | <0.001 | |

| 7 9 mo | 169 (69.5%) | 79 (67.5%) | 90 (71.4%) | ||

| 10-12 mo | 32 (13.2%) | 24 (20.5%) | 8 (6.3%) | ||

| Years in nephrology | 3 [1-6] | 3 [1-6] | 4 [1-7] | 0.24 | |

Note: Values expressed as median [interquartile range] or number (percent).

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; KFRE, Kidney Failure Risk Equation.

Chi-square tests for categorical measures and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous measures.

Patient-Facing Values Clarification Tool

Among patients who received kidney failure treatment modality education during the observation period, 30/33 (91%) completed the values clarification tool. Five (17%) required assistance completing the tool due to poor vision (n = 2) or feeling uncomfortable with the tablet (n = 3). Mean time to complete the tool was 8 (range, 3-13) minutes. Patients who received modality education had lower Charlson Comorbidity Index scores and more time enrolled in case management (Table 3).

Table 3.

Characteristics of Receiving Versus Not Receiving Kidney Failure Treatment Modality Education

| Characteristic | All Enrolled Patients (N = 117) | Kidney Failure Treatment Modality Education |

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Received (n = 33) | Not Received (n = 84) | Pa | ||

| Age, y | 71 [60-80] | 71 [59-79] | 70 [61-80] | 0.73 |

| Female sex | 50 (43%) | 10 (30%) | 40 (48%) | 0.08 |

| eGFR, mL/min/1.73 m2 | 21.4 [16.6-25.7] | 22.3 [16.6-25.7] | 20.9 [16.6-25.5] | 0.81 |

| KFRE score | 0.16 [0.10-0.28] | 0.17 [0.08-0.29] | 0.16 [0.10-0.28] | 0.95 |

| Charlson Comorbidity Index score | 6 [4-7] | 5 [3-6] | 6 [4-8] | 0.01 |

| Diabetes | 83 (71%) | 22 (67%) | 61 (73%) | 0.52 |

| Cardiovascular disease | 65 (56%) | 65 (56%) | 79 (63%) | 0.26 |

| Time on registry as of June 30, 2018 | 8 [8-9] | 9 [9-10] | 8 [8,9] | 0.05 |

| 1-3 mo | 2 (1.7%) | 0 (0.0%) | 2 (2.4%) | |

| 4-6 mo | 12 (10.3%) | 4 (12.1%) | 8 (9.5%) | 0.29 |

| 7-9 mo | 79 (67.5%) | 19 (57.6%) | 60 (71.4%) | |

| 10-12 mo | 24 (20.5%) | 10 (30.3%) | 14 (16.7%) | |

| Time enrolled as of June 30, 2018 | 6 [4-9] | 8 [5-9] | 6 [3-8] | 0.02 |

| 1-3 mo | 25 (21.4%) | 3 (9.1%) | 22 (26.2%) | |

| 4-6 mo | 34 (29.1%) | 11 (33.3%) | 23 (27.4%) | 0.03 |

| 7-9 mo | 43 (36.8%) | 11 (33.3%) | 32 (38.1%) | |

| 10-12 mo | 15 (12.8%) | 8 (24.2%) | 7 (8.3%) | |

| Years in nephrology | 3 [1-6] | 3 [1-6] | 4 [1-7] | 0.69 |

Note: Values expressed as median [interquartile range] or number (percent).

Abbreviations: eGFR, estimated glomerular filtration rate; KFRE, Kidney Failure Risk Equation.

Chi-square tests for categorical measures and Kruskal-Wallis tests for continuous measures.

Navigation and Tracking Application

Kidney Transitions Specialists used the navigation and tracking application for documentation on 100% of enrolled patients (n = 117). They documented 287 navigation steps to facilitate planning for kidney replacement therapy, including offers for kidney disease self-management education (n = 27 [23%]), offers for kidney failure treatment modality education (n = 105 [90%]), vascular access for hemodialysis preparation (n = 54 [46%]), steps toward kidney transplantation (n = 92 [79%]), and planning for peritoneal dialysis (n = 9 [8%]).

EHR Work Flow Broadcasting Patients’ Treatment Preferences

Of 117 high-risk patients enrolled, 102 (87%) had a preferred kidney replacement modality documented on the EHR problem list. The treatment modalities documented varied across all potential options, including kidney transplantation (n = 15 [15%]), in-center hemodialysis (n = 38 [37%]), home hemodialysis (n = 5 [5%]), peritoneal dialysis (n = 13 [13%]), conservative care (n = 23 [23%]), and undecided (n = 35 [34%]).

Acceptability of PREPARE NOW Tools

The 2 Kidney Transitions Specialists who delivered the intervention completed the surveys. Both were women, White, and aged 50 to 60 years and had more than 20 years of nursing experience. One had more case management experience (6 vs 3 years) and provided feedback on the design of the tools in the pilot phase of the study. Both were employed and managed by Geisinger Health Plan. The Kidney Transitions Specialists rated the ease of use and helpfulness of the tools highly (100% responded agree or strongly agree for all items). They reported a variety of advantages and challenges to using the tools (Table 4). Responses were similar between staff members.

Table 4.

Kidney Transitions Specialist Feedback on Use of Tools

| Tool | Theme | Quotes |

|---|---|---|

| CKD registry | Patient identification and risk stratification | “The CKD registry is a great tool in identifying which patients are at highest level of acuity according to the numbers. It is helpful having all the information in one place as far as function, appointments and identifying information.” |

| Values tool | Alignment of values | “The Values tool is helpful in seeing what is important to the patient and then you can refer to it as you go through the Kidney Options class. I think it is helpful for the patient to see what is important to him in writing and having to stop and think about it.” |

| Values tool | Digital literacy | “The iPads are not always user friendly, especially to older population. Paper copy seems to work better and is easily transferred to chart.” |

| Navigation and tracking tool | Efficiency | “[the navigation and tracking tool] helps to cut [down] on documentation time to spend more conversation time with patients.” “It is a good tool for review when talking with p[atien]ts.” |

| Navigation and tracking tool | Duplicate data entry | “Would be nicer if the referrals and completed appts (eg, palliative, transplant, vascular) placed would flow automatically [from EPIC] into the tracker tool just like the [Kidney] Options completed classes.” |

Abbreviation: CKD, chronic kidney disease.

Discussion

The PREPARE NOW Study has implemented an integrated suite of digital engagement applications providing a user-friendly interface and experience for patients, nurse case managers, and other health care providers that supports patients’ shared decision making about and their preparation for kidney replacement therapies. The initial 12 months of implementation demonstrated consistent uptake of applications and the feasibility of integrating applications into clinic work flows, providing important data for implementation by other health systems. By helping health care providers identify patients who are most in need of preparation early, helping patients clarify their values, prompting patients’ informed decision making, tracking patients’ preparation for treatments, and supporting their navigation toward preferred therapies, the infrastructure may play an important role in supporting efforts to overcome patients’ barriers to receiving their desired treatments.

Digital engagement platforms are increasingly being used in the care of patients with CKD. Electronic registries,17 automated risk prediction algorithms,18 automated decision support tools,19 artificial intelligence and natural language processing,20 and patient portals21 are being deployed to improve the recognition and treatment of patients with early and advanced CKD.22 However, to our knowledge, multiple integrated health information system applications designed as a suite of products to facilitate the achievement of a number of goals supporting patients’ decision making and preparation for kidney replacement treatments have not been previously implemented. Successful implementation and uptake of the infrastructure by PREPARE NOW, which leverages a widely used EPIC EHR platform, illustrates the potential feasibility of implementing similar approaches across other health care settings.

Several novel features of the PREPARE NOW digital infrastructure advance capabilities around CKD care. First, using the CKD registry facilitates ready identification of the full population of patients at risk for CKD progression. Risk stratification using the Kidney Failure Risk Equation has further enabled a triage function to help Kidney Transitions Specialists prioritize their efforts toward patients who are at greatest risk for progression.

Second, electronic collection of patients’ values in a user-friendly interface before receiving education about treatment options helps formalize the process whereby patients consider the factors that would most likely drive their informed decisions about treatments. By providing patients with printed materials of their selected values to take home with them, they have opportunities to reflect on how potential treatment options might best align with their values over time.

Third, the process of prominently broadcasting patients’ treatment preferences on problem lists before patients initiate treatments allows all providers in the health care system to eliminate ambiguity regarding preferences and prompts health care providers to help patients receive the kidney failure treatments they most desire.

Finally, providing Kidney Transitions Specialists with electronic tools to help them navigate patients through the steps needed to achieve their treatments and track their progress may facilitate their receipt of treatments that align with their values.

Despite initial success with implementing PREPARE NOW digital tools, several questions remain as implementation continues. First, the sustained use of digital tools by Kidney Transitions Specialists has not yet been demonstrated. Results of the 4-year randomized controlled trial will provide additional information on their sustained uptake. Second, although we have built the PREPARE NOW infrastructure within an Epic ecosystem (a widely used EHR platform), tailored features of the program unique to the Geisinger EPIC implementation may need to be adapted to the needs of other programs in their specific settings. For instance, Geisinger has developed customized user interfaces for documenting health care provider notes23,24 that other programs may not use. Further, PREPARE NOW navigation and tracking have been designed to accommodate Kidney Transitions Specialists working in partnership between Geisinger and its affiliated health plan. Other health care systems that may not have similar partnerships or staffing structures may need to modify the approach to accommodate their specific needs. Finally, successful long-term use of digital tools requires periodic updates and engagement with end users to meet ongoing needs, which should be taken into account by other health systems planning similar approaches.

Despite these considerations, the successful implementation of an integrated suite of digital tools to support preparation for kidney failure treatment represents an advance in the field that can serve as a model for other institutions to adopt based on their own needs and resources. Table 5 provides alternative ways for health systems to implement similar approaches in the absence of advanced technologic resources.

Table 5.

Alternatives to PREPARE NOW Digital Tools

| Tool | Alternatives |

|---|---|

| CKD registry with risk prediction |

|

| Patient values tool |

|

| Navigation and tracking tool |

|

| Treatment preferences broadcast |

|

Abbreviations: CKD, chronic kidney disease; EHR, electronic health record.

In summary, the PREPARE NOW study has demonstrated the successful implementation and uptake of an integrated suite of digital tools providing the health system infrastructure to support a number of key functions to facilitate patients’ shared and informed decision making and preparation for kidney failure treatments. This supportive health system infrastructure could have a significant impact on the clinical care of patients with CKD and their outcomes.

Article Information

Authors’ Full Names and Academic Degrees

Jamie A. Green, MD, Patti L. Ephraim, MPH, Felicia Hill-Briggs, PhD, Teri Browne, PhD, Tara S. Strigo, MPH, Chelsie L. Hauer, MPH, Christina Yule, BS, Rebecca A. Stametz, DEd, Diane Littlewood, RN, Jane F. Pendergast, PhD, Sarah Peskoe, PhD, Jennifer St. Clair Russell, PhD, Evan Norfolk, MD, Ion D. Bucaloiu, MD, Shravan Kethireddy, MD, Daniel Davis, PhD, Jeremy dePrisco, BA, Dave Malloy, BS, Sherri Fulmer, RN, Jennifer Martin, BA, Dori Schatell, MS, Navdeep Tangri, MD, PhD, Amanda Sees, BS, Cory Siegrist, MBA, Jeffrey Breed Jr, BS, Jonathan Billet, BS, Matthew Hackenberg, RN, Nrupen A. Bhavsar, PhD, and L. Ebony Boulware, MD.

Authors’ Contributions

Research idea and study design: JAG, PLE, FH-B, TB, TSS, CLH, CY, RAS, DL, JFP, JSCR, EN, IDB, SK, DD, JD, DM, SF, JM, DS, NT, AS, CS, JBJ, JB, MH, NAB, LEB; data acquisition: JAG, PLE, FH-B, TB, TSS, CLH, CY, JFP, SP, SK, JD, DM, SF, AS, CS, JBJ, JB, MH, LEB; data analysis/interpretation: JAG, PLE, FH-B, TB, TSS, CLH, CY, RAS, JFP, SP, JSCR, EN, IDB, SK, DM, SF, JM, DS, NT, CS, JBJ, JB, LEB; statistical analysis: JFP, SP; supervision or mentorship: JAG, PLE, FH-B, TB, JFP, LEB. Each author contributed important intellectual content during manuscript drafting or revision and accepts accountability for the overall work by ensuring that questions pertaining to the accuracy or integrity of any portion of the work are appropriately investigated and resolved.

Support

This work was supported through a Patient-Centered Outcomes Research Institute (PCORI) Project Program Award (IHS-1409-20967).

Financial Disclosure

The authors declare that they have no relevant financial interests.

Acknowledgements

The PREPARE NOW Study team consists of members from Duke University, Durham, NC (L. Ebony Boulware, Clarissa Diamantidis, Clare Il’Giovine, George Jackson, Jane Pendergast, Sarah Peskoe, Tara S. Strigo), Geisinger Health System, Danville, PA (Jon Billet, Jason Browne, Ion Bucaloiu, Charlotte Collins, Daniel Davis, Sherri Fulmer, Jamie Green, Chelsie Hauer, Evan Norfolk, Michelle Richner, Cory Siegrist, Wendy Smeal, Rebecca Stametz, Mary Solomon, Christina Yule,), Johns Hopkins University, Baltimore, MD (Patti Ephraim, Raquel Greer, Felicia Hill-Briggs), the University of South Carolina, Columbia, SC (Teri Browne), the University of Manitoba, Winnipeg, Manitoba, Canada (Navdeep Tangri), members of the Patient and Family Caregiver Stakeholder Group (Brian Bankes, Shakur Bolden, Patricia Danielson, Katina Lang-Lindsey, Suzanne Ruff, Lana Schmidt, Amy Swoboda, Peter Woods), the American Association of Kidney Patients (Diana Clynes), Council of Nephrology Social Workers (Stephanie Stewart), Medical Education Institute (Dori Schatell, Kristi Klicko), Brandi Vinson (Mid-Atlantic Renal Coalition), National Kidney Foundation (Jennifer St. Clair Russell, Kelli Collins, Jennifer Martin), Renal Physicians Association (Dale Singer), and Pennsylvania Medical Society (Diane Littlewood). The authors thank Kristi Klicko for contributions to the article and the physicians, nurses, medical assistants, staff, and patients of the Geisinger Health System, Danville, PA.

Disclaimer

All statements in this report, including its findings and conclusions, are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the views of the PCORI, its Board of Governors, or Methodology Committee.

Peer Review

Received September 2, 2020. Evaluated by 2 external peer reviewers, with direct editorial input from the Editor-in-Chief. Accepted in revised form March 14, 2021.

Footnotes

Complete author and article information provided before references.

References

- 1.Coresh J., Selvin E., Stevens L.A. Prevalence of chronic kidney disease in the United States. JAMA. 2007;298(17):2038–2047. doi: 10.1001/jama.298.17.2038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Saran R., Robinson B., Abbott K.C. US Renal Data System 2019 Annual Data Report: epidemiology of kidney disease in the United States. Am J Kidney Dis. 2020;75(1 Suppl 1) doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2019.09.003. Svi–Svii. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Inker L.A., Astor B.C., Fox C.H. KDOQI US commentary on the 2012 KDIGO clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(5):713–735. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2014.01.416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Kidney Disease: Improving Global Outcomes (KDIGO) CKD Work Group KDIGO 2012 clinical practice guideline for the evaluation and management of chronic kideny disease. Kidney Int Suppl. 2013;3(1):1–150. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kinchen K.S., Sadler J., Fink N. The timing of specialist evaluation in chronic kidney disease and mortality. Ann Intern Med. 2002;137(6):479–486. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-137-6-200209170-00007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ameling J.M., Auguste P., Ephraim P.L. Development of a decision aid to inform patients' and families' renal replacement therapy selection decisions. BMC Med Inform Decis Mak. 2012;12:140. doi: 10.1186/1472-6947-12-140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Greer R.C., Crews D.C., Boulware L.E. Challenges perceived by primary care providers to educating patients about chronic kidney disease. J Renal Care. 2012;38(4):174–181. doi: 10.1111/j.1755-6686.2012.00323.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sheu J., Ephraim P.L., Powe N.R. African American and non-African American patients' and families' decision making about renal replacement therapies. Qual Health Res. 2012;22(7):997–1006. doi: 10.1177/1049732312443427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Institute of Medicine . The National Academies Collection: Reports funded by National Institutes of Health. In: Grossmann C., Powers B., McGinnis J.M., editors. Digital Infrastructure for the Learning Health System: The Foundation for Continuous Improvement in Health and Health Care: Workshop Series Summary. National Academies Press, National Academy of Sciences; 2011. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Green J.A., Ephraim P.L., Hill-Briggs F.F. Putting patients at the center of kidney care transitions: PREPARE NOW, a cluster randomized controlled trial. Contemp Clin Trials. 2018;73:98–110. doi: 10.1016/j.cct.2018.09.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tangri N., Grams M.E., Levey A.S. Multinational assessment of accuracy of equations for predicting risk of kidney failure: a meta-analysis. JAMA. 2016;315(2):164–174. doi: 10.1001/jama.2015.18202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tangri N., Stevens L.A., Griffith J. A predictive model for progression of chronic kidney disease to kidney failure. JAMA. 2011;305(15):1553–1559. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.451. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Wojciechowski P., Tangri N., Rigatto C., Komenda P. Risk prediction in CKD: the rational alignment of health care resources in CKD 4/5 care. Adv Chronic Kidney Dis. 2016;23(4):227–230. doi: 10.1053/j.ackd.2016.04.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.My Life MDC My Life, My Dialysis Choice. https://mydialysischoice.org/#ey

- 15.CKD Decisions Helping patients & families make informed decisions about kidney disease treatments. 2020. http://ckddecisions.org/

- 16.Proctor E.K., Landsverk J., Aarons G., Chambers D., Glisson C., Mittman B. Implementation research in mental health services: an emerging science with conceptual, methodological, and training challenges. Adm Policy Ment Health. 2009;36(1):24–34. doi: 10.1007/s10488-008-0197-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.McBride D., Dohan D., Handley M.A., Powe N.R., Tuot D.S. Developing a CKD registry in primary care: provider attitudes and input. Am J Kidney Dis. 2014;63(4):577–583. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2013.10.012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Tangri N., Inker L.A., Hiebert B. A dynamic predictive model for progression of CKD. Am J Kidney Dis. 2017;69(4):514–520. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2016.07.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Abdel-Kader K., Fischer G.S., Li J., Moore C.G., Hess R., Unruh M.L. Automated clinical reminders for primary care providers in the care of CKD: a small cluster-randomized controlled trial. Am J Kidney Dis. 2011;58(6):894–902. doi: 10.1053/j.ajkd.2011.08.028. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Vazquez M. UH3 Project: Improving Chronic Disease Management with Pieces (ICD-Pieces™) http://www.rethinkingclinicaltrials.org/uh3-project-improving-chronic-disease-management-with-pieces-icd-pieces/

- 21.Jhamb M., Cavanaugh K.L., Bian A. Disparities in electronic health record patient portal use in nephrology clinics. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2015;10(11):2013–2022. doi: 10.2215/CJN.01640215. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Roy J., Shou H., Xie D. Statistical methods for cohort studies of CKD: prediction modeling. Clin J Am Soc Nephrol. 2017;12(6):1010–1017. doi: 10.2215/CJN.06210616. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Foley T., Fairmichael F. Site visit to Geisinger Health System. 2016. http://www.learninghealthcareproject.org/section/evidence/1/63/site-visit-to-geisinger-health-system

- 24.Hagland M. Geisinger CIO John Kravitz: IT Facilitating Continuous Care Delivery Transformation—In Real Time. 2016. https://www.hcinnovationgroup.com/clinical-it/article/13026923/geisinger-cio-john-kravitz-it-facilitating-continuous-care-delivery-transformationin-real-time