Abstract

Activation of caspase, externalization of phosphatidyl serine, change in the mitochondrial membrane potential, and DNA fragmentation are apoptosis markers found in human ejaculated spermatozoa. Also, reactive oxygen species (ROS) play a vital role in the different types of male infertility. In this review, data sources including Google Scholar, Scopus, PubMed, and Science Direct were searched for publications with no particular time restriction to get a holistic and comprehensive view of the research. Apoptosis regulates the male germ cells, correct function and development from the early embryonic stages of gonadal differentiation to fertilization. In addition to maintaining a reasonable ratio between the Sertoli and germ cells, apoptosis is one of the well-known quality control mechanisms in the testis. Also, high ROS levels cause a heightened and dysregulated apoptotic response. Apoptosis is one of the well-known mechanisms of quality control in the testis. Nevertheless, increased apoptosis may have adverse effects on sperm production. Recent studies have shown that ROS and the consequent oxidative stress play a crucial role in apoptosis. This review aims to assimilate and summarize recent findings on the apoptosis in male reproduction and fertility. Also, this review discusses the update on the role of ROS in normal sperm function to guide future research in this area.

Keywords: Fertility, Spermatogonia, Apoptosis, Reproduction, DNA fragmentation, DNA integrity, ROS.

1. Introduction

Infertility is an important medical and behavioral issue that affects many people. Apoptosis is an important physiological mechanism which has been shown to play significant roles in various physiological processes. Apoptosis, which is characterized by chromatin disintegration during programmed cell death, is a distinct mechanism that leads to DNA fragmentation. This biological process is critical for proper germ cell formation and the maintenance of the germ cell-Sertoli ratio in the testis (1, 2). In the 1940s, reactive oxygen species (ROS) were reported as a potential contributor to male infertility (3). Oxidative stress (OS) leads to defect sperm operation. Recent studies have shown that ROS can be a contribute factor in 30-80% of infertile males (4). OS is caused by an imbalance in the physiology of body between antioxidants and ROS (5). The major causes of DNA damage are aberrant apoptosis and OS. DNA fragmentation is a common result of ROS-mediated damage, and it's most commonly seen in infertile men's spermatozoa. Direct or indirect ROS-mediated damage can result in single or double-stranded fragments and abnormal apoptosis (1). Semen analysis is an important first step in the laboratory assessment of an infertile male (6). It includes evaluation of the volume of ejaculates and sperm quantity, motility, and shape by the World Health Organization criteria (7). The effects of male elderly on quality of semen, DNA breakage, and chromosomal abnormalities have been studied since 1970 have been reported in infertile patients and fertile donors but the results are conflicting (8). Pollutants in nature cause harmful effects on sperm motility, vitality, membrane lipid composition, and acrosome status and is related to excessive ROS production (9).

This review aimed to assimilate and summarize recent findings of apoptosis as an important physiological process in male infertility.

2. Materials and Methods

Search strategy

This study is a narrative review and the data were retrieved from Google Scholar, PubMed, Scopus and Science Direct. Publications were searched with no particular time restriction from 1943 to 2020 to get a holistic and comprehensive view of the research done on this topic so far with the following terms: “Apoptosis", “Fertility", “Male infertility", “Mitochondria in the apoptosis", “Spermatogenesis", “Apoptosis in a male germ cell", “Apoptosis pathways", “Hormones, and germ cell apoptosis", “Sperm morphology and ROS production", “Sperm apoptosis", “Sperm DNA integrity", and “DNA fragmentation Apoptosis, and semen quality".

Study selection

The study was done in three steps: first, the titles of the papers were searched according to the selected terms, and appropriate titles were selected for the next step. Second, abstracts were reviewed and eligible papers were selected. At the last step, full-texts of the eligible papers were evaluated. In total, 1,253 papers were evaluated, of which, 1,168 were excluded because of no consistency with the study goals or no new important data. Finally, 85 papers were included in this review. Also, 30 papers were omitted because of the language of the papers (such as Turkish or Arabic).

3. Results

Spermatogenesis

Spermatogenesis is one of the most active self-renewal processes in the body: 10 sperm per day are produced per gram of testicular tissue. The time taken to complete the cycle is unique and unalterable for any mammalian species. Since the process is supported by somatic Sertoli cells, cell-cell interaction between the germ and Sertoli cells is generally thought to control the duration of cell cycles and cell organization (10-12). Spermatogenesis is divided into three stages: (i): spermatogonia duplication and distinction; (ii) meiosis, and (iii) spermiogenesis, a complex mechanism which transforms round spermatids after meiosis into a complex structure called the spermatozoon. In humans, the spermatogenesis process begins at the time of puberty and continues throughout a men's lifetime (13). During this process, an early wave of apoptosis that follows the first round of spermatogenesis in the testes will eliminate excess spermatogonia (14). Disorder in apoptosis results in a phenotype of male infertility due to an imbalance in germ- and Sertoli cell numbers (15). Later during the life, apoptosis plays a role in the elimination of germ cells that are damaged by exposure to environmental toxicants, chemotherapy drugs, or heat (16). Almost 75% of the spermatogonia die in the process of apoptosis before maturity (17, 18). Therefore, apoptosis plays a significant role in controlling the spermatogenesis of different species of mammals, including humans (19). High apoptosis levels have been reported in infertile men testicular biopsies (20). Although spermatogenesis is affected by the hypothalamic-pituitary-testicular axis, exogenous factors such as infections, exposure to heavy metals, smoking of cigarettes, irradiation, chemicals/herbs, and medicines impair spermatogenesis and predispose sperm cells to harm.

Apoptosis

Apoptosis is a programmed cell death that involves the removal of genetically damaged cells (2). In the lack of special cell surface receptors, factors that can penetrate the cell straight and modulate the apoptotic cascade may cause apoptotic activation (21). Such factors include: heat shock, stressors, ROS, ultraviolet radiation, drug, synthetic peptides, and toxins (22). Nowadays, the attendance and activity of apoptotic signals in human sperm in response to different stimuli are widely accepted (23, 24). There are two distinct mechanisms for apoptosis initiation: extrinsic pathway or receptor apoptosis and apoptosis endogenous or mitochondrial (25). Specific mechanisms include the perforin-granzyme A and B pathway and P53 pathway that induces apoptosis (26, 27). The biochemical particularity of apoptosis consists of the transmission of phosphatidylserine to the plasma membrane external, caspase activation, and DNA fragmentation (28). Caspase activity is associated with sperm immaturity, low numbers, decreased motilities (29, 30), lower fertilization levels (31), and lack of plasma membrane integrity, as demonstrated by externalization of phosphatidylserine (32). Caspases are cysteine proteases which promote apoptosis in mammals (33). Apoptosis cycle is significant in the background of germ cells because both mitosis and meiosis occur in cells, and cell death may be necessary to remove cells with genetic defects during the process (34). The proportion of apoptotic sperm in infertile men's ejaculated semen samples is reported to be higher than in healthy men (35). Furthermore, during cryopreservation, infertile patients' sperm caspases become more active than healthy donors' (36). However, it is unclear whether the apoptotic markers detected in spermatozoa are remnants of an unsuccessful apoptotic cycle that occurred before to ejaculation, or if they are the product of apoptosis that occurred after ejaculation (37).

The role of mitochondria in the apoptosis process

Mitochondria are organelles that participate in the ATP synthesis, calcium signals, production of ROS, and regulation of apoptosis (21). Mitochondrial abnormalities trigger physiological disorders, including infertility (38). The mitochondria function at the heart of the apoptotic pathway by offering main factors, including those which trigger caspase activity and DNA fragmentation (39). Caspases are a family of proteases that are essential for the regulation of apoptosis (40). Cytochrome c, which is one of the main factors of apoptosis, mediates caspase 9 and caspase 3 activations, which leads to cell suicide (41). Bcl-2 is a family of regularizer proteins that play a role in the control of mitochondrial permeability and, therefore, in apoptosis regulation (2).

Apoptosis in male germ cell

Internal pathway of apoptosis

Primordial germ cells are sourced from the epiblast and finally migrate to the gonad. Surplus cells produced during this time are killed by apoptosis, which depends mainly on the harmony between Bcl-xL and Bax (42). The early wave of apoptosis removed in transgenic mice with overexpressing Bcl-2 or Bclx results in the cumulation of spermatogonia and spermatocytes, further resulting in infertile animals (43). Bcl-x-knockout mice had severe defects in male germ cells during growth (44). Therefore, adult rats with two mutant Bcl-x alleles lack spermatogonia (42). Bcl-w mutant mice show almost perfect degeneration of the testicles (34). Although Bax, Bcl-w, and Bcl-2 are the primary regulators of germ cell growth and maturity post-birth, Bcl-x is necessary for the durability of primordial germ cells in the embryonic gonad during early phases (45).

External pathway of apoptosis

Fas is a transmembrane molecule with 281 amino acids which are activated by FasL and intercede apoptosis. FasL and respective receptor Fas both interact, and the activated Fas induce apoptosis in the cell (46). It is widely accepted that Sertoli cells regulate the number of germ cells by one of the most common apoptotic pathways, the Fas/FasL paracrine signal transmission machine, in which the FasL expressed in Sertoli cells and Fas expressed in germ cells induce apoptosis when connecting with each other (47). Mice with a random loss of function mutation in the Fas gene (Fas) or FasL (Fasl) develop apparent lymphoproliferative and autoimmune diseases. The consequence of the Fas/FasL-mediated cycle is hypospermatogenesis, such as maturity arrest and Sertoli cell syndrome. Germ cell maturity may be associated with Fas gene expression that is able to induce apoptosis to eliminate damaged germ cells (48). The expression of Fas/FasL in the human testis is regulated by gonadotropin. It is generally proven that the Fas/FasL system may have a role in the quality-control process of the manufactured gametes (34).

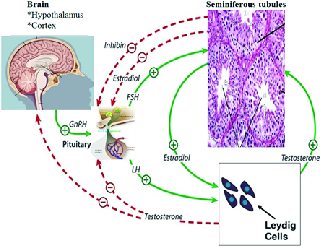

Hormones and germ cell apoptosis

In the mammalian testes, follicle-stimulating hormone (FSH), luteinizing hormone, gonadotropin, and testosterone regulate germ cells proliferation, differentiation, and viability (34). Luteinizing hormone helps with steroidogenesis by activating Leydig cells, but FSH activates the Sertoli cells to help with the spermatogenesis developmental stages (13). Getting exposed to excess hormones or hormone deficiency may result in cellular apoptosis in the testis (49). Sertoli cells have FSH and testosterone receptors, which are the major spermatogenesis hormonal regulators. Removal of the hormone causes apoptosis of germ cells (50). While testosterone and the synergistic activity of FSH with estradiol help germ cell survival during seminiferous tubular maturity, estradiol alone has an inhibitory effect and is an inducer of apoptosis (Figure 1) (34). Besides, excess testosterone can lead to increased expression of Fas/FasL in testis (51). Testosterone removal stimulates caspase activity and results in DNA fragmentation in Sertoli cells (52).

Sperm apoptosis

In the seminiferous epithelium, spermatogenesis is accompanied by germ cell apoptosis, a cycle that generally takes place during life. Apoptosis of germ cells is essential to retain the optimal germ cell ratio to Sertoli cells and to remove abnormal germ cells, especially during maturity. The exit of phosphatidylserine to the outer membrane of the sperm, caspases activation, and chromosome fragmentation are considered to mark apoptosis (53). Bcl-2, the apoptosis inhibitor gene, safeguards the cell by reducing the ROS generation. Although the FAS receptor frequently causes apoptosis, this fails to clean all the sperm intended for elimination, leading to a high population of defective sperm. The percentage of FAS-positive sperm can be 50% in men with unusual sperm parameters (5).

Role of apoptosis in male infertility

In certain pathological circumstances, an enormous increase in germ cell apoptosis occurs, which involves idiopathic infertility in males (54). Apoptosis has been observed often in spermatocytes, less in spermatogonia, and rarely in spermatids (55). Fujisawa and co-workers documented the existence of apoptosis in the testes, especially in spermatocytes (56). A study by Martincic and colleagues determined the presence and abundance of germ cells apoptosis in infertile males whereas Sertoli cells do not undergo apoptosis (18). It has been shown that the Fas-system is involved in regulating the spontaneous apoptosis of germ cells. In the normal state, Sertoli cells express FasL which triggers the apoptosis in Fas-positive germ cells, and shows a paracrine interaction between germ and Sertoli cells (57, 58). Apoptosis increases with age in the testes, resulting in a decrease in germ cells. This may be linked with the reduction in androgen levels or a rise in OS (21). Measuring apoptosis rates can also be used as a sign for pursuing male infertility treatment (59).

The role of OS in apoptosis

OS is one of the major causes of male infertility. In recent years, the production of ROS and its influence on semen quality have been widely studied. OS occurs as a result of an imbalance between ROS production and antioxidants (1, 60).

Mitochondrial exposure to ROS leads to the induction of apoptosis and thus causes the fragmentation of the DNA (19, 61). A direct association between increased sperm damage caused by ROS and high levels of cytochrome C, caspase 9, and 3 was demonstrated in the study by Soderquist and colleagues which showed positive apoptosis in infertile men. Studies in infertile men have shown that high levels of cytochrome C in plasma show remarkable mitochondrial harm by ROS (62). Increased age causes ROS to accumulate which induces lipid peroxidation. Excessive amounts of ROS and reduced antioxidant capacity during ageing can cause apoptosis or oxidative damage to DNA (63). The damaged paternal DNA, if not repaired, may through fertilization reach the couple's offspring, causing a variety of diseases (64). In this regard, certain clinical research have found that giving antioxidants improves sperm DNA integrity. Vitamin C, vitamin E, and glutathione, when taken together for two months, dramatically reduced the levels of 8OHdG, a marker for OS-induced sperm DNA damage (65).

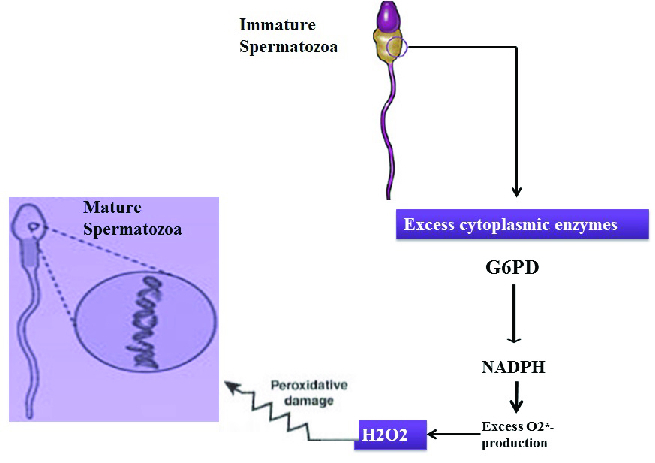

Effect of sperm morphology on ROS production

Teratozoospermia is caused by a defect in the spermatogenesis process and is determined by sperm with an excess cytoplasm (65). Remaining cytoplasm stimulates sperms to produce endogenous ROS through processes that can be mediated by the enzyme glucose-6-phosphate dehydrogenase. Teratozoospermia patients are at higher risk of pathogenic ROS, apoptosis, and DNA damage (Figure 2) (66). ROS generation is highest in immature sperm from males with abnormal semen values. Also, there is a direct relationship between the ROS generation and the spermatozoa deformation indicator, calculated by dividing the total count of abnormal sperms by the count of sperms evaluated (67).

The effect of ROS on sperm

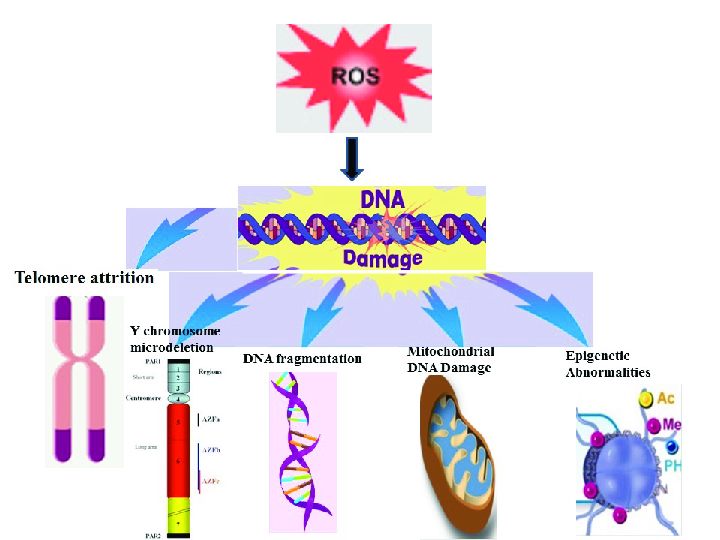

Excessive ROS in human semen is severely correlated with male infertility (68). ROS are free radicals derived from oxygen that are required at a low level for capacitation, hyperactivation, motility, and acrosome reaction (69). Nonetheless, excessive ROS level can lead to OS and consequently cause DNA damage, lipid peroxidation, shorting of telomeres, epigenetic variations, Y chromosome microdeletions, and induction of apoptosis (Figure 3) (70, 71). Aitken and Clarkson first observed ROS using the method of chemiluminescence in the human ejaculate (72). Also, high amounts of ROS negatively affect sperm concentration, motility, morphology, and male fertility (67, 73, 74). The sources of endogenous ROS are immature sperm and leukocytes, and there are different external causes (75). Genitourinary infections, varicocele, cigarette smoking, alcohol, recreational drug misuse, ionizing radiation, cell phone usage, stress, excessive exercise, spinal cord damage, parental age, and environmental pollution are all active variables in the OS production (76-78). Sperms are vulnerable to OS because it contains high values of polyunsaturated fatty acids that are sensitive to lipid peroxidation (70). The by-products of lipid oxidization include mutagenic molecules acrolein, malondialdehyde, and 4 hydroxy-nonenal (4-HNE), which indirectly lead to DNA damage (4). 4-HNE and acrolein lead to induction apoptosis and fragmentation of DNA (79). Malondialdehyde has been used in various biochemical studies to track the degree of sperm-related peroxidative damage (79, 80). More of the sperm genome (almost 85%) is linked to central nucleoproteins, which preserves it against free radical attacks (4). Therefore, the plasma membrane is the main purpose of ROS, which triggers a cascade of events that damage the genetic confirmation of sperm (69). In a study conducted by Venkatesh et al., the sperm count, sperm motility percentage, and normal sperm morphology percentage in infertile men reduced significantly in comparison with the control groups. Also, ROS levels in infertile men increased significantly in comparison with the control groups. No significant relation was observed between ROS levels and semen parameters (81).

Apoptosis as a marker of semen quality

Apoptosis of sperm was considered a potentially useful indicator of male fertility (21). Loss of germ cell, which happens via apoptosis, is a prevailing mechanism during spermatogenesis and is regulated by the expression levels of p53, p21, Bcl-2, FAS, and caspases (82). Several studies have reported increased apoptosis rates in samples of poor-quality semen (19). Apoptosis happens during spermatogenesis and has been proven too in ejaculated sperm (83, 84). Studies showed the fragmentation of DNA in ejaculated sperm. OS causes damage to DNA and increased levels of oxidative damage in sperm DNA (85). The measurement of apoptosis may be an index of semen quality (21).

Figure 1.

Effects of hormones on the germ cells survival. LH helps with steroid genesis by activating Leydig cells but FSH activates the Sertoli cells to help the developmental stages of spermatogenesis.

Figure 2.

Effects of sperm morphology on the production of endogenous ROS. Figure shows the mechanism for the link between OS and sperm DNA damage. OS leads to damage of the sperm DNA.

Figure 3.

Examples of DNA damage caused by ROS. Excess ROS overwhelms the seminal plasma's neutralizing capacity of antioxidants, triggering OS and, consequently, DNA damage in the nucleus and mitochondria.

4. Conclusion

Apoptosis is one of the well-known mechanisms of quality control in the testis. Nevertheless, increased apoptosis may have adverse effects on sperm production, eventually compromising male fertility. Therefore, controlling the rate of apoptosis for fertility in men is of particular importance. Also, ROS and the consequent OS play a crucial role in apoptosis. ROS have been shown to cause abnormalities in semen analysis and sperm concentration. Therefore, ROS can cause infertility in men.

Conflict of Interest

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the research council of Mohaghegh Ardabili University for the financial support of this study.

References

- Latchoumycandane C, Vaithinathan S, D’Cruz S, Mathur PP. Parekattil SJ, Esteves SC, Agarwal A, editors. Male infertility. Switzerland: Springer; 2020. Apoptosis and male infertility; pp. 479–486. [Google Scholar]

- Bejarano I, RodrÃguez AB, Pariente JA. Apoptosis is a demanding selective tool during the development of fetal male germ cells. Front Cell Dev Biol. 2018;6:65. doi: 10.3389/fcell.2018.00065. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacLeod J. The role of oxygen in the metabolism and motility of human spermatozoa. Am J Physiol-Leg Content. 1943;138:512–518. [Google Scholar]

- Bisht Sh, Faiq M, Tolahunase M, Dada R. Oxidative stress and male infertility. Nat Rev Urol. 2017;14:470–485. doi: 10.1038/nrurol.2017.69. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Makker K, Agarwal A, Sharma R. Oxidative stress & male infertility. Indian J Med Res. 2009;129:357–367. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Agarwal A, Rohra VK, Assidi M, Abu-Elmagd M, Turki RF. Effects of increased paternal age on sperm quality, reproductive outcome and associated epigenetic risks to offspring. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2015;13:35. doi: 10.1186/s12958-015-0028-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . WHO laboratory manual for the examination of human semen and sperm-cervical mucus interaction. UK: Cambridge University press; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Brahem S, Mehdi M, Elghezal H, Saad A. The effects of male aging on semen quality, sperm DNA fragmentation and chromosomal abnormalities in an infertile population. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2011;28:425–432. doi: 10.1007/s10815-011-9537-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kutluyer F, Çakir Sahilli Y, Kocabaş M, Aksu Ö. Sperm quality and oxidative stress in chub Squalius orientalis and Padanian barbel Barbus plebejus (Teleostei: Cyprinidae) after in vitro exposure to low doses of bisphenol A. Drug Chem Toxicol. 2020;7:1–6. doi: 10.1080/01480545.2020.1726379. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roosen-Runge EC, Holstein AF. The human rete testis. Cell Tissue Res. 1978;189:409–433. doi: 10.1007/BF00209130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- França LR, Ogawa T, Avarbock MR, Brinster RL, Russell LD. Germ cell genotype controls cell cycle during spermatogenesis in the rat. Biol Reprod. 1998;59:1371–1377. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod59.6.1371. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kuchakulla M, Narasimman M, Khodamoradi K, Khosravizadeh Z, Ramasamy R. How defective spermatogenesis affects sperm DNA integrity. Andrologia. 2020;53:13615. doi: 10.1111/and.13615. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Agarwal A. Zini A, Agarwal A, editors. A clinician’s guide to sperm DNA and chromatin damage. Switzeland: Springer; 2018. Defective spermatogenesis and sperm DNA damage; pp. 229–261. [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Findlay JK, Hutt KJ, Kerr JB. Apoptosis in the germ line. Reproduction. 2011;141:139–150. doi: 10.1530/REP-10-0232. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez I, Ody C, Araki K, Garcia I, Vassalli P. An early and massive wave of germinal cell apoptosis is required for the development of functional spermatogenesis. EMBO J. 1997;16:2262–2270. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.9.2262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Ch, Cui YG, Wang XH, Jia Y, Sinha Hikim A, Lue YH, et al. Transient scrotal hyperthermia and levonorgestrel enhance testosterone-induced spermatogenesis suppression in men through increased germ cell apoptosis. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2007;92:3292–3304. doi: 10.1210/jc.2007-0367. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Print CG, Loveland KL. Germ cell suicide: New insights into apoptosis during spermatogenesis. Bioessays. 2000;22:423–430. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1521-1878(200005)22:5<423::AID-BIES4>3.0.CO;2-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Koppers AJ. Apoptosis and DNA damage in human spermatozoa. Asian J Androl. 2011;13:36–42. doi: 10.1038/aja.2010.68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Abdolmaleki A, Ghayour MB, Behnam-Rassouli M. Protective effects of acetyl-l-carnitine against serum and glucose deprivation-induced apoptosis in rat adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells. Cell Tissue Bank. 2020;21:655–666. doi: 10.1007/s10561-020-09844-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cavalcanti MCO, Steilmann C, Failing K, Bergmann M, Kliesch S, Weidner W, et al. Apoptotic gene expression in potentially fertile and subfertile men. Mol Hum Reprod. 2011;17:415–420. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gar011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shukla KK, Mahdi AA, Rajender S. Apoptosis, spermatogenesis and male infertility. Front Biosci. 2012;4:746–754. doi: 10.2741/415. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fulda S, Gorman AM, Hori O, Samali A. Cellular stress responses: Cell survival and cell death. Int J Cell Biol. 2010;2010:214074. doi: 10.1155/2010/214074. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Espino J, Mediero M, Lozano GM, Bejarano I, Ortiz Ã, GarcÃa JF, et al. Reduced levels of intracellular calcium releasing in spermatozoa from asthenozoospermic patients. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:1–11. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monllor F, Espino J, Marchena AM, Ortiz A, Lozano G, GarcÃa JF, et al. Melatonin diminishes oxidative damage in sperm cells, improving assisted reproductive techniques. Turk J Biol. 2017;41:881–889. doi: 10.3906/biy-1704-45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Igney FH, Krammer PH. Death and anti-death: Tumour resistance to apoptosis. Nat Rev Cancer. 2002;2:277–288. doi: 10.1038/nrc776. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vogelstein B, Lane D, Levine AJ. Surfing the p53 network. Nature. 2000;408:307–310. doi: 10.1038/35042675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Martinvalet D, Zhu P, Lieberman J. Granzyme A induces caspase-independent mitochondrial damage, a required first step for apoptosis. Immunity. 2005;22:355–370. doi: 10.1016/j.immuni.2005.02.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fadok VA, Voelker DR, Campbell PA, Cohen JJ, Bratton DL, Henson PM. Exposure of phosphatidylserine on the surface of apoptotic lymphocytes triggers specific recognition and removal by macrophages. J Immunol. 1992;148:2207–2216. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marchetti C, Jouy N, Leroy-Martin B, Defossez A, Formstecher P, Marchetti Ph. Comparison of four fluorochromes for the detection of the inner mitochondrial membrane potential in human spermatozoa and their correlation with sperm motility. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:2267–2276. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh416. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lozano GM, Bejarano I, Espino J, Gonzalez D, Ortiz A, Garcia JF, et al. Relationship between caspase activity and apoptotic markers in human sperm in response to hydrogen peroxide and progesterone. J Reprod Dev. 2009;55:615–621. doi: 10.1262/jrd.20250. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald S, Sharma R, Paasch U, Glander HJ, Agarwal A. Impact of caspase activation in human spermatozoa. Microsc Res Tech. 2009;72:878–888. doi: 10.1002/jemt.20732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paasch U, Grunewald S, Agarwal A, Glandera HJ. Activation pattern of caspases in human spermatozoa. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:802–809. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.09.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Salvesen GS, Dixit VM. Caspases: Intracellular signaling by proteolysis. Cell. 1997;91:443–446. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80430-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaha C, Tripathi R, Mishra DP. Male germ cell apoptosis: Regulation and biology. Philos Trans R Soc B Biol Sci. 2010;365:1501–1515. doi: 10.1098/rstb.2009.0124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Taylor SL, Weng SL, Fox P, Duran EH, Morshedi MS, Oehninger S, et al. Somatic cell apoptosis markers and pathways in human ejaculated sperm: Potential utility as indicators of sperm quality. Mol Hum Reprod. 2004;10:825–834. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gah099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grunewald S, Paasch U, Wuendrich K, Glander HJ. Sperm caspases become more activated in infertility patients than in healthy donors during cryopreservation. Arch Androl. 2005;51:449–460. doi: 10.1080/014850190947813. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lachaud Ch, Tesarik J, Cañadas ML, Mendoza C. Apoptosis and necrosis in human ejaculated spermatozoa. Hum Reprod. 2004;19:607–610. doi: 10.1093/humrep/deh130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rajender S, Rahul P, Mahdi AA. Mitochondria, spermatogenesis and male infertility. Mitochondrion. 2010;10:419–428. doi: 10.1016/j.mito.2010.05.015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adams JM. Ways of dying: Multiple pathways to apoptosis. Genes Dev. 2003;17:2481–2495. doi: 10.1101/gad.1126903. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sakkas D, Moffatt O, Manicardi GC, Mariethoz E, Tarozzi N, Bizzaro D. Nature of DNA damage in ejaculated human spermatozoa and the possible involvement of apoptosis. Biol Reprod. 2002;66:1061–1067. doi: 10.1095/biolreprod66.4.1061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li P, Nijhawan D, Budihardjo I, Srinivasula SM, Ahmad M, Alnemri ES, et al. Cytochrome c and dATP-dependent formation of Apaf-1/caspase-9 complex initiates an apoptotic protease cascade. Cell. 1997;91:479–489. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(00)80434-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rucker EB, Dierisseau P, Wagner KU, Garrett L, Wynshaw-Boris A, Flaws JA, et al. Bcl-x and Bax regulate mouse primordial germ cell survival and apoptosis during embryogenesis. Mol Endocrinol. 2000;14:1038–1052. doi: 10.1210/mend.14.7.0465. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Knudson CM, Tung KS, Tourtellotte WG, Brown GA, Korsmeyer SJ. Bax-deficient mice with lymphoid hyperplasia and male germ cell death. Science. 1995;270:96–99. doi: 10.1126/science.270.5233.96. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasai S, Chuma S, Motoyama N, Nakatsuji N. Haploinsufficiency of Bcl-x leads to male-specific defects in fetal germ cells: Differential regulation of germ cell apoptosis between the sexes. Dev Biol. 2003;264:202–216. doi: 10.1016/s0012-1606(03)00400-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong SY, Seol DW. The role of mitochondria in apoptosis. BMB Rep. 2008;41:11–22. doi: 10.5483/bmbrep.2008.41.1.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Janssen O, Qian J, Linkermann A, Kabelitz D.

- Porcelli F, Meggiolaro D, Carnevali A, Ferrandi B. Fas ligand in bull ejaculated spermatozoa: A quantitative immunocytochemical study. Acta Histochem. 2006;108:287–292. doi: 10.1016/j.acthis.2006.05.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Francavilla S, D’Abrizio P, Cordeschi G, Pelliccione F, Necozione S, Ulisse S, et al. Fas expression correlates with human germ cell degeneration in meiotic and post-meiotic arrest of spermatogenesis. Mol Hum Reprod. 2002;8:213–220. doi: 10.1093/molehr/8.3.213. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shaha Ch Germ cell apoptosis: Relevance to infertility and contraception. Immun Endoc Metab Agents Med Chem. 2008;8:66–78. [Google Scholar]

- Sofikitis N, Giotitsas N, Tsounapi P, Baltogiannis D, Giannakis D, Pardalidis N. Hormonal regulation of spermatogenesis and spermiogenesis. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2008;109:323–330. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2008.03.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou XC, Wei P, Hu ZY, Gao F, Zou RJ, Liu YX. Role of Fas/FasL genes in azoospermia or oligozoospermia induced by testosterone undecanoate in rhesus monkey. Acta Pharmacol Sin. 2001;22:1028–1033. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesarik J, Martinez F, Rienzi L, Iacobelli M, Ubaldi F, Mendoza C, et al. In-vitro effects of FSH and testosterone withdrawal on caspase activation and DNA fragmentation in different cell types of human seminiferous epithelium. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1811–1819. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.7.1811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Evenson DP. Loss of livestock breeding efficiency due to uncompensable sperm nuclear defects. Reprod Fertil Dev. 1999;11:1–16. doi: 10.1071/rd98023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pareek TK, Joshi AR, Sanyal A, Dighe RR. Insights into male germ cell apoptosis due to depletion of gonadotropins caused by GnRH antagonists. Apoptosis. 2007;12:1085–1100. doi: 10.1007/s10495-006-0039-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sasagawa I, Matsuki S, Suzuki Y, Iuchi Y, Tohya K, Kimura M, et al. Possible involvement of the membrane-bound form of peroxiredoxin 4 in acrosome formation during spermiogenesis of rats. Eur J Biochem. 2001;268:3053–3061. doi: 10.1046/j.1432-1327.2001.02200.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fujisawa M, Hiramine C, Tanaka H, Okada H, Arakawa S, Kamidono S. Decrease in apoptosis of germ cells in the testes of infertile men with varicocele. World J Urol. 1999;17:296–300. doi: 10.1007/s003450050149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J, Richburg JH, Younkin SC, Boekelheide K. The Fas system is a key regulator of germ cell apoptosis in the testis. Endocrinology. 1997;138:2081–2088. doi: 10.1210/endo.138.5.5110. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pentikäinen V, Erkkilä K, Dunkel L. Fas regulates germ cell apoptosis in the human testis in vitro. Am J Physiol. 1999;276:310–316. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.1999.276.2.E310. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Baker MA. Causes and consequences of apoptosis in spermatozoa; contributions to infertility and impacts on development. Int J Dev Biol. 2013;57:265–272. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.130146ja. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Makker K, Sharma R. Clinical relevance of oxidative stress in male factor infertility: An update. Am J Reprod Immunol. 2008;59:2–11. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0897.2007.00559.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vashisht A, Gahlay GK. Using miRNAs as diagnostic biomarkers for male infertility: Opportunities and challenges. Mol Hum Reprod. 2020;26:199–214. doi: 10.1093/molehr/gaaa016. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Söderquist L, Rodriguez-Martinez H, Janson L. Post-thaw motility, ATP content and cytochrome C oxidase activity of AI bull spermatozoa in relation to fertility. Zentralbl Veterinarmed A. 1991;38:165–174. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0442.1991.tb00998.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petersen CG, Mauri AL, Vagnini LD, Renzi A, Petersen B, Mattila M, et al. The effects of male age on sperm DNA damage: An evaluation of 2,178 semen samples. JBRA Assist Reprod. 2018;22:323–330. doi: 10.5935/1518-0557.20180047. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunes S, Hekim GNT, Arslan MA, Asci R. Effects of aging on the male reproductive system. J Assist Reprod Genet. 2016;33:441–454. doi: 10.1007/s10815-016-0663-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Said TM. Oxidative stress, DNA damage and apoptosis in male infertility: A clinical approach. BJU Int. 2005;95:503–507. doi: 10.1111/j.1464-410X.2005.05328.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ. The amoroso lecture. The human spermatozoon-a cell in crisis? J Reprod Fertil. 1999;115:1–7. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.1150001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aziz N, Saleh RA, Sharma RK, Lewis-Jones I, Esfandiari N, Thomas Jr AJ, et al. Novel association between sperm reactive oxygen species production, sperm morphological defects, and the sperm deformity index. Fertil Steril. 2004;81:349–354. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2003.06.026. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Sharma RK, Nallella KP, Thomas Jr AJ, Alvarez JG, Sikka SC. Reactive oxygen species as an independent marker of male factor infertility. Fertil Steril. 2006;86:878–885. doi: 10.1016/j.fertnstert.2006.02.111. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bui AD, Sharma R, Henkel R, Agarwal A. Reactive oxygen species impact on sperm DNA and its role in male infertility. Andrologia. 2018;50:e13012. doi: 10.1111/and.13012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Saleh RA, Bedaiwy MA. Role of reactive oxygen species in the pathophysiology of human reproduction. Fertil Steril. 2003;79:829–843. doi: 10.1016/s0015-0282(02)04948-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sawyer DE, Mercer BG, Wiklendt AM, Aitken RJ. Quantitative analysis of gene-specific DNA damage in human spermatozoa. Mutat Res. 2003;529:21–34. doi: 10.1016/s0027-5107(03)00101-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Clarkson JS. Cellular basis of defective sperm function and its association with the genesis of reactive oxygen species by human spermatozoa. J Reprod Fertil. 1987;81:459–469. doi: 10.1530/jrf.0.0810459. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yumura Y, Iwasaki A, Saito K, Ogawa T, Hirokawa M. Effect of reactive oxygen species in semen on the pregnancy of infertile couples. Int J Urol. 2009;16:202–207. doi: 10.1111/j.1442-2042.2008.02213.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Agarwal A, Mulgund A, Sharma R, Sabanegh E. Mechanisms of oligozoospermia: An oxidative stress perspective. Syst Biol Reprod Med. 2014;60:206–216. doi: 10.3109/19396368.2014.918675. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Takeshima T, Kuroda S, Yumura Y. Cristiana F, editor. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) in living cells. UK: IntechOpen; Reactive oxygen species and sperm cells; 2018 pp. [Google Scholar]

- Harlev A, Agarwal A, Gunes SO, Shetty A, du Plessis SS. Smoking and male infertility: An evidence-based review. World J Mens Health. 2015;33:143–160. doi: 10.5534/wjmh.2015.33.3.143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sharma R, Harlev A, Agarwal A, Esteves SC. Cigarette smoking and semen quality: A new meta-analysis examining the effect of the 2010 World Health Organization laboratory methods for the examination of human semen. Eur Urol. 2016;70:635–645. doi: 10.1016/j.eururo.2016.04.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bisht S, Dada R. Oxidative stress: Major executioner in disease pathology, role in sperm DNA damage and preventive strategies. Front Biosci (Schol Ed) 2017;9:420–447. doi: 10.2741/s495. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aitken RJ, Whiting S, De Iuliis GN, McClymont S, Mitchell LA, Baker MA. Electrophilic aldehydes generated by sperm metabolism activate mitochondrial reactive oxygen species generation and apoptosis by targeting succinate dehydrogenase. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:33048–33060. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M112.366690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esterbauer H, Schaur RJ, Zollner H. Chemistry and biochemistry of 4-hydroxynonenal, malonaldehyde and related aldehydes. Free Radic Biol Med. 1991;11:81–128. doi: 10.1016/0891-5849(91)90192-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Venkatesh S, Riyaz AM, Shamsi MB, Kumar R, Gupta NP, Mittal S, et al. Clinical significance of reactive oxygen species in semen of infertile Indian men. Andrologia. 2009;41:251–256. doi: 10.1111/j.1439-0272.2009.00943.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tesarik J, Greco E, Cohen-Bacrie P, Mendoza C. Germ cell apoptosis in men with complete and incomplete spermiogenesis failure. Mol Hum Reprod. 1998;4:757–762. doi: 10.1093/molehr/4.8.757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shen HM, Dai J, Chia SE, Lim A, Ong CN. Detection of apoptotic alterations in sperm in subfertile patients and their correlations with sperm quality. Hum Reprod. 2002;17:1266–1273. doi: 10.1093/humrep/17.5.1266. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saleh RA, Agarwal A. Oxidative stress and male infertility: From research bench to clinical practice. J Androl. 2002;23:737–752. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Q, Lin HY, Yeh SD, Yu IC, Wang RS, Chen YT, et al. Infertility with defective spermatogenesis and steroidogenesis in male mice lacking androgen receptor in Leydig cells. Endocrine. 2007;32:96–106. doi: 10.1007/s12020-007-9015-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]