Abstract

Pathologists are faced with a variety of problems when considering placental tissue in cases of stillbirth. It is recognized that there are changes which occur following fetal demise and which can complicate the assessment and may coexist with other morphological changes. It is recognized that up to 25% of stillbirths may have a recognizable abnormality causing fetal demise. A systematic review of placental tissue allows many of these disorders to be identified. This review considers macroscopic and microscopic features of placental pathology in stillbirth together with clinicopathological correlation. Stillbirth definitions, general aspects of macroscopic assessment of placentas, placental changes after fetal demise, and some recognizable causes of fetal demise are considered.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Placenta, Stillbirth, Histopathology

Introduction

Stillbirth Definitions

The World Health Organization (WHO) recommends the definition of stillbirth as a baby born with no signs of life after 28 weeks’ gestation (1). There are more conservative definitions currently in place in many developed countries, including the United States (2), United Kingdom, and Australia (this is highlighted in Table 1).

Table 1:

| Country | Gestational Age | Weight, g |

|---|---|---|

| Australia | >20 weeks | >400 |

| New Zealand | >20 weeks | >400 |

| United States | >20 weeks | N/A |

| United Kingdom | >24 weeks | N/A |

| Germany | N/A | >500 |

| France | >22 weeks | >500 |

| Italy | >180 days | N/A |

| Japan | >22 weeks | N/A |

| Taiwan | >20 weeks | >500 |

| India | >28 weeks | N/A |

| Sudan | >28 weeks | N/A |

| Ghana | >28 weeks | N/A |

Definitions of stillbirth vary and usually relate to fetal demise at 20 weeks’ gestation or later. The variations in definitions are shown in Tables 1 and 2. All live births and fetal loss before 20 weeks’ gestation are excluded. When gestational age is not determined, still birth may be defined by fetal weight, acknowledging that stillbirths of similar gestation to live births weigh significantly less. Fetuses weighing more than 400 g are generally regarded as stillborn if gestational age cannot be determined (12).

Table 2:

WHO Definition of Stillbirth

| WHO (ICD-10) | Gestational Age | Weight, g | Length, cm |

|---|---|---|---|

| Early fetal death | >22 weeks | >500 | >35 |

| Late fetal death | >28 weeks | >1000 | N/A |

| Proposed ICD-11 definition (no subcategorization) | >28 weeks | N/A | N/A |

WHO = World Health Organization

ICD = International Classification of Diseases

Many preventable stillbirths occur in almost every country (1). Data collection for stillbirth is not complete and investigation of placental pathology is limited in many reports.

General Aspects of Macroscopic Examination of Placenta

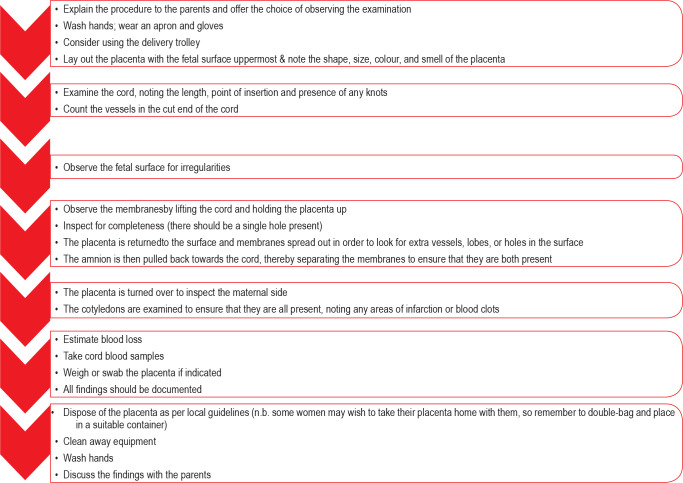

All placentas should be examined by birth attendants (Image 1) and the Royal College of Midwives in the United Kingdom has outlined acceptable practice in relation to routine deliveries in National Health Service hospitals (13). This is shown in Figure 1 (12).

Image 1:

Unremarkable fresh placenta typically viewed by birth attendants.

Figure 1:

A guide to placental examination for midwives.

Additional pathological assessment is necessary for all stillbirths. It is also important in the assessment of many live born infants, and the criteria and approach have been well outlined (14). It is of interest that the weight of the placenta is not always recorded by birth attendants. The issue of assessment of placental weight is an important part of macroscopic placental assessment (13). While assessment of weight with and without attached membranes and umbilical cord is commonly recommended (15), it is not always performed. The trimmed weight is the more significant criterion (16). Placental weight may vary because of congestion of fetal villous capillaries and adherent clot.

Umbilical cord assessment in stillbirth placentas is a key aspect of macroscopic pathology. Cord accidents are a recognized cause of stillbirth. Excessively long cords are associated with entanglement, prolapse, knots, hypercoiling, constriction, and thrombosis (17). A recent article has noted an association with malformation in fetuses with short umbilical cords (18). This may affect stillbirth rate. Identification of hypercoiled cords is associated with fetal pathology of the central nervous system and musculoskeletal system. There is controversy regarding constriction of twisted cords, particularly at the fetal end of the cord, but most experts support the view that this is a cause of fetal demise in utero. The application of associated histological criteria of vascular ectasia, thrombus within the umbilical cord vessels, and smaller thrombi in fetal stem villi or chorionic plate is useful in supporting the macroscopic findings (19).

Determination of central, eccentric, marginal (battledore), or velamentous cord insertion should be made. Particular histological sampling of cords showing velamentous insertion is required. Cord discoloration may occur within four hours of fetal demise.

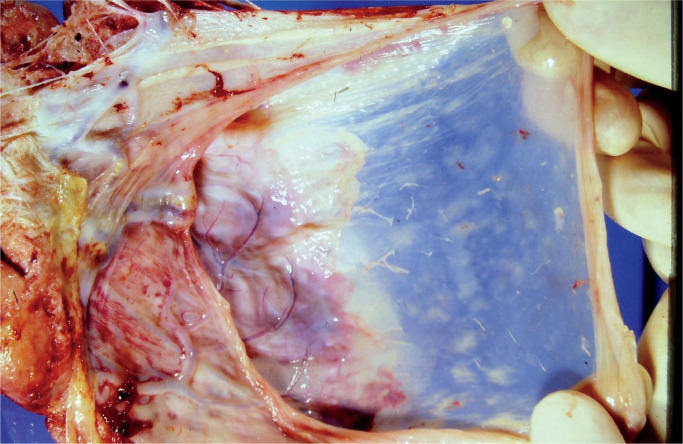

Macroscopic examination of fetal membranes in stillbirths is important and may provide information allowing determination of fetal demise (20). Discoloration may occur within four hours of fetal demise. Opacity and discoloration are common findings. Marked opacity may indicate inflammatory cellular infiltration of membranes. Image 2 demonstrates opacity in membranes from a case of chorioamnionitis. Pigment deposition seen may be difficult to determine macroscopically. The pigment may be characterized histologically and use of special stains, mainly Perls’ Prussian blue stain to identify iron deposition, is necessary.

Image 2:

Placental membranes showing membrane opacification from a case of chorioamnionitis

Changes in cord and membranes prior to delivery of a stillborn infant occurs fairly rapidly and estimation of time of fetal demise based on macroscopic and microscopic assessment of these tissues (21) is inaccurate. The general description of these changes is described as maceration and many factors such as the presence of bacteria in the tissues, maternal fever, and duration of maternal hypoxia are known to influence the rate of maceration (22).

Detecting and classifying specific macroscopic lesions is difficult. Pale firm areas may have many different etiologies. The location of hematomas may sometimes be difficult to classify in cases where the placenta is delivered in a fragmented state. Microscopic assessment is useful in these situations.

Stillbirth—Changes in Placenta After Fetal Demise

Although there have been considerable reductions in mortality from a number of common diseases in recent decades, the incidence of stillbirth in developing and wealthy countries has declined modestly (23). In Australia, stillbirth incidence has not declined significantly since 2000 (24). The proportion of stillbirths with unexplained in utero fetal demise appears to be declining (25). The number of unexplained stillbirths varies considerably in studies (26, 27). The failure to determine a precise cause of fetal demise relates mainly to the difficulty of clinicopathological correlation rather than absence of detection of macroscopic and microscopic abnormalities. In studies with low unexplained stillbirth rates, fetal demise is attributed to placental disease in greater numbers (28).

The pathogenesis of the changes has been considered in detail by Stanek (29) and changes of chronic hypoxia appear to precede the morphological changes. Acute hypoxia by contrast leads to localized infarction. There is overlap. There are good predictors of placental changes which may indicate time from fetal demise to delivery (30). These morphological changes are presented in Table 3. Examination of the placental tissue in isolation from the stillbirth limits the utility of these observations.

Table 3:

Some Changes in Placental Villous Tissues Following Fetal Demise

| Villous Change | Time After Fetal Demise |

|---|---|

| Stromal vascular karyorrhexis | From 6 hours |

| Stem villous destruction /obliteration | From 48 hours |

| Villous fibrosis | From 14 days |

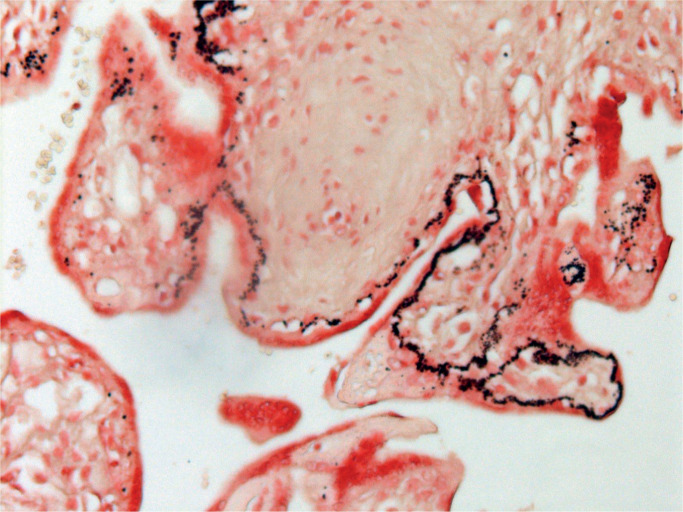

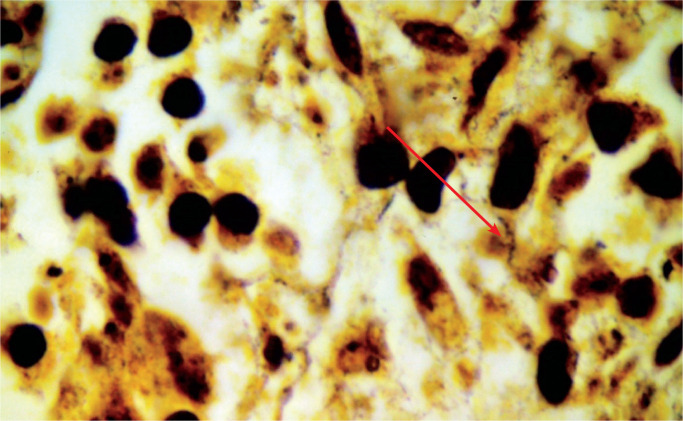

Placental calcification seen at 28 to 32 weeks’ gestation is associated with an adverse outcome. In cases of fetal demise, calcification becomes more prominent and initially is seen in thickened villous basement membranes (31). There is a close link with fetal hypoxia (29). The deposition of calcification is initially granular, but larger, more aggregated deposits are seen later. Image 3 demonstrates initial villous calcification following fetal demise.

Image 3:

Early deposition of dystrophic calcification in basement membranes of chorionic villi (Von Kossa stain X100).

Stillbirth—Recognizable Causes of Fetal Demise

The disorders may be considered as cord, membranous, or placental disc related.

Cord-Related Disorders

Cord-related disorders are complex and may be associated with a range of clinical scenarios. While a range of embryonic remnants are seen in cord tissue, they are not associated with stillbirth. Single umbilical artery is common and is associated with an increased incidence of cord accidents, growth restriction, maternal diabetes, and antepartum hemorrhage. There is association with diverse congenital abnormalities, oligohydramnios, and polyhydramnios. There are reports of supernumerary vessels and these may be associated with congenital abnormality. Thrombi are found in a small number of cords. The incidence appears to be less than one in 1000 deliveries (32).

In most stillbirths with thrombi present, some organization is seen. Veins are the common site of cord vascular thrombi. There is an association with knots and entanglement.

Cord entanglement, knots, and prolapse are recognized in many stillbirths and may be causative. Cord entanglement is quite frequently noted and nuchal cords may be seen from 20 weeks’ gestation. Most occur in long cords. Obstruction of venous return to the placenta is regarded as the mode of fetal demise. Examination of multiple sections of cord in regions of possible thrombus formation is suggested.

Cord prolapse occurs when umbilical cord precedes fetal presenting parts during delivery. There is a high likelihood of fetal demise as well as neonatal death. Autopsy findings are variable and the diagnosis cannot be made with certainty by autopsy findings alone.

True knots are present in up to 1% of cords and most are loose. Those with associated venous thrombi within tight knots are of significance. False knots are of no clinical significance.

While there are many forms of cord insertion, velamentous insertion is of major significance and hemorrhage may occur at this site resulting in fetal demise. Thrombosis may also be noted.

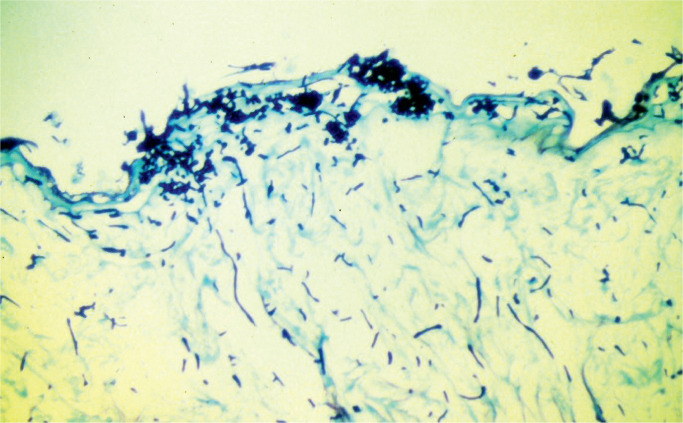

Funisitis may be recognized either macroscopically or microscopically and is usually associated with ascending infection. Image 4 highlights patchy funisitis. It may be less severe than the chorioamnionitis found.

Image 4:

Umbilical cord tissue demonstrating patchy funisitis. A positive culture for Candida albicans was noted).

Membranous Disorders

Membranous changes may be divided into those associated with ascending infections and those associated with fetal developmental abnormalities. Ascending infections are common and are closely associated with stillbirth. Membranes may be intact or ruptured. The macroscopic changes may be minimal or may be thick and exudative. The inflammatory process may also result in funisitis, villitis, and deciduitis. The correlation with clinical findings is usually without difficulty, but some stillbirth cases are less clear with limited inflammation present. The key histological feature is neutrophilic infiltration. Fibrinous exudate and loss of amniotic cells are usually noted. In some placentas particularly with severe group B streptococcal infections, large numbers of coccal organisms may be seen with only a limited number of neutrophils present. Most studies have highlighted group B streptococci as the most likely cause of ascending infection causing still birth (33). Folgosa et al (34) have reported the specific etiological organisms in chorioamnionitis causing stillbirth in a population in Maputo, Mozambique, and noted the prevalence of ascending infection related to Escherichia coli. The diversity of results reported has been noted particularly in regions where the burden of infectious diseases is high (33). Many reports of bacterial, viral, and protozoan ascending infections are reported (15). Of the bacterial causes, Fusobacterium and Clostridia represent difficulty with identification and may require stains in addition to hematoxylin and eosin stain and gram stain. in addition to hematoxylin and eosin stain and gram stain; Warthin-Starry and Silver stains are examples of such.

Bacterial vaginosis has been reported in cases of premature rupture of membranes and increased incidence of preterm birth, but clear association with stillbirth is not reported (35).

Reports of Candida infection associated with stillbirth with the presence of placental infection are rare (36), Image 5 demonstrates a case.

Image 5:

Numerous hyphal structures on the amniotic surface (methylene blue stain x100).

Placental Disc-Related Disorders

Acute and chronic villitis are recognized causes of stillbirth. There are diverse etiologies.

Acute villitis is associated with a variety of infections where there is ascending infection involving placental villi or following maternal septicemia. A typical example of the latter is Listeria monocytogene infection in which acute villitis and characteristic microabscess formation is seen (37). Listeria infections are foodborne infections resulting in bacteremia in susceptible individuals, including pregnant women. The range of foods involved has become more complex and includes dairy, meat products, and a range of salad vegetables and fruits such as cantaloupes or rock melons.

Chronic villitis is defined as chronic inflammatory infiltrate in chorionic villi and is associated with stillbirth. It may be classified as of known or unknown etiology. Chronic villitis of unknown etiology is known to occur in 5% to 15% of all placentas, and in selected cases, such as those in growth restriction or stillbirth, up to 30% of placentas are reported with this. There are two major suggestions regarding possible etiology. The first relates to minor graft-versus-host disorder and the second relates to viral disease not recognized by limited viral immunohistochemical staining. Careful correlation with clinical history is necessary (38).

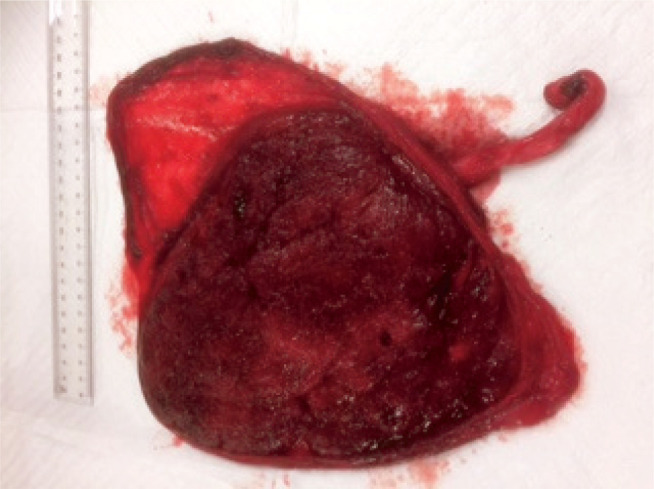

Chronic villitis associated with definitive microbiological etiology is well recognized and assessment of placentas from stillborn fetuses requires careful sampling of the placental disc and correlation with maternal serology and microbiological cultures. Image 6 demonstrates spirochetes in an example of congenital syphilis.

Image 6:

Numerous spirochaetes in a case of congenital syphilis, see arrow (Warthin Starry stain X400)

The causes of these specific infections are numerous and diverse. Bacterial, viral, protozoan, and nematode infections have been reported (39). Bacterial, viral, protozoan and nematode infections have been reported, but Cytomegalovirus infection is the most prevalent (39). Histopathological features are not able to reliably identify all specific infections. Although histopathological features are not able to reliably identify all specific infections, specific features of protozoans and viral inclusions may be observed.

Key issues linking placental disorders to fetal demise include the major vascular disorders of the placenta. It may be difficult to precisely classify disorders as obstetric complications or placental disease (2). This is particularly true in relation to vascular phenomena. Fetal demise associated with perivillous fibrin deposition and maternal floor infarction and fetal vasculopathy may have a significant maternal hemorrhage but are appropriately classified as placental diseases.

Massive perivillous fibrin deposition and maternal floor infarction are usually present in relatively small placental discs. Careful sectioning is needed to identify the location of the lesion and its extent. Multiple sections of the region are advised because all of the microscopic changes—individual fibrotic and infarcted villi separated by fibrin, cytotrophoblast cells within fibrin, and cysts—are rarely seen in one histological section. The maternal floor infarction often requires these additional sections to allow identification.

Fetal vasculopathy may be difficult to separate from intrauterine fetal demise. The morphological changes may overlap and the changes depend on determining that there is a true localized region of placental villous abnormality. Nonocclusive thrombi are seen in fetal stem villi and isolated fibrin deposits are noted occasionally. Obliteration of these vessels may be seen in some cases. It is possible that chronic villous inflammation precedes these vascular changes, but it is difficult to establish (40). The use of fibrin stains may be helpful in some cases. There is a classification system based on the number of affected villi; its value in predicting outcome is yet to be fully assessed, but most stillbirth cases are regarded as large or high grade.

Placental abruption is regarded as a clinical diagnosis and a retroplacental hematoma may be seen. It is thought that the probable etiology is rupture of a decidual artery. It is linked to maternal smoking and cocaine consumption, which are associated with significant fetal loss. While examination of the placenta and clot may highlight the severity of the condition, a specific localized macroscopic or microscopic lesion is not usually found. The age of the hematoma is difficult to assess.

Trophoblastic disorders are only linked to stillbirth when coexisting fetus is twinned with complete mole or if the triploid fetus in partial mole has a gestation greater than 20 weeks. These rare events may be diagnosed with careful placental examination and karyotyping.

Many stillbirths are caused by major congenital abnormalities, but the placenta is rarely significantly and specifically affected by the abnormality. With neural tube defects, adhesion to the placenta of the anencephalic head has been reported and immature development of placental villi may be seen (41). In modern obstetric practice, there has been a reduction in the numbers of stillbirths linked to congenital abnormality.

Placenta accreta, increta, and percreta have been increasing in incidence in many countries due to increase in cesarean section rates (42). The diagnosis cannot be made without uterine material associated with attached placenta. Up to 3% result in stillbirth. No specific cord or membranous abnormality has been reported. Most placentas studied are third trimester morphology and no localized villous abnormality is seen. Direct attachment of placental villous tissue to uterine myometrial tissue occurs.

There are many maternal diseases associated with fetal demise which are well recognized. Relatively few stillbirths are the consequence of preexisting maternal disease with the exception of hypertensive disorders and diabetes mellitus (2). The placental morphology of these diseases is well described, but the precise pathophysiological explanations for these morphologic changes is not fully understood.

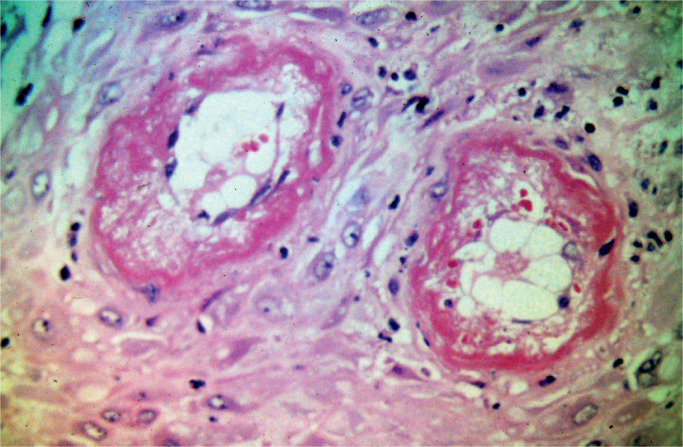

Preeclampsia is defined as the combination of hypertension associated with pregnancy after 20 weeks’ gestation and proteinuria and is seen in up to 7% of pregnancies. The outcome of these pregnancies is poorer than other gestations and there is a recognized association with stillbirth. The main placental changes are decidual vasculopathy, infarction, placental abruption, villous maldevelopment, and reduced placental disc mass. The decidual vascular changes appear to precede the other changes. Image 7 demonstrates the vascular changes. The vessels do not undergo the changes seen in normal placental development. The diameter of the arterial structures is reduced. Smooth muscle cells persist in arteriolar structures. There is a proliferation of subendothelial cells (atherosis), thrombosis, inflammatory infiltration of arterial walls, and fibrinoid necrosis. These changes may be difficult to identify and many sections of decidual bed tissue may be required. Areas of infraction, particularly in severe cases, may obscure these key vascular changes. Infarcts of varying ages may assist in the diagnosis. Additional sections of maternal bed are often needed in cases of abruption. Villous hypoplasia is often recognized but is not specific for the disorder. This is shown in Image 8.

Image 7:

Decidual bed demonstrating maternal vessels with fibrinoid necrosis and atherosis (haematoxylin and eosin x100)

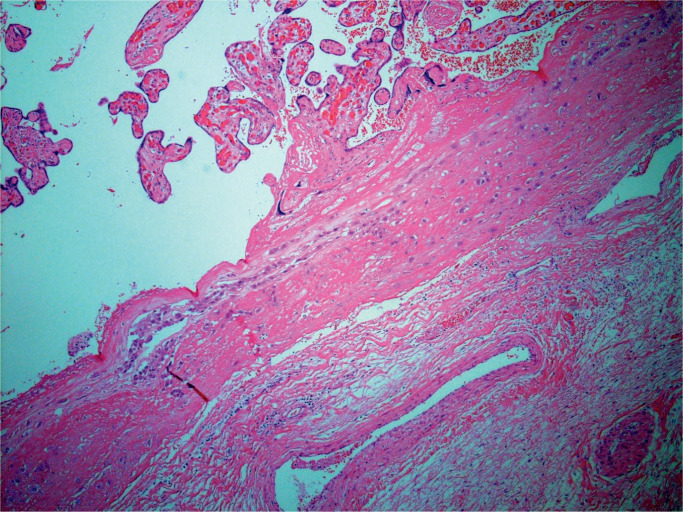

Image 8:

Placenta from diabetic patient with villous hypoplasia and fibrin deposition (haematoxylin and eosin x40)

Maternal diabetes mellitus has been rapidly increasing in incidence. Most recent data indicate that stillbirth rates in this population have been declining (43). The pathological changes in the placenta of diabetic patients vary considerably. Many placentas are thick, congested, and friable. Villous enlargement is a common feature and villi are often dysmature. The features are not specific to diabetes and it is not possible to determine type of diabetes from the histopathology. Poor control of diabetes is responsible for more severe changes.

Stillbirth incidence in twin pregnancy is greater in both monochorionic and dichorionic twins than singletons (40). There are specific aspects relating to twin placenta and stillbirth and these include twin-twin transfusion and increased congenital abnormality rate (44). Monochorionic monoamniotic twins have an even greater rate of fetal demise. Careful examination of the dividing membrane histopathology including T-zone sections is advised. Fetus papyraceous may be present adherent to membrane tissue. This would not be classified as stillbirth in the WHO classification but may qualify based on gestational age in some regions. More complex multiple gestation placental studies require careful sampling of dividing membranes and genetic analysis of cord tissue.

Conclusion

The major issue of placental examination in stillbirth is to assist assessment of fetal demise. The number of stillbirths with a specific cause of fetal demise can be addressed by careful assessment of placental macroscopic and microscopic morphology. Determining whether there is a specific placental disease or an obstetric complication may be difficult.

Authors

Robert G. Wright MB ChB FRCPA, Bond University - Faculty Health Sciences & Medicine

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, principal investigator of the current study.

Christopher Macindoe MBBS, Pathology Queensland - Gold Coast University Hospital

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, general administrative support, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Patricia Green RN/RM, Bond University - Faculty Health Sciences & Medicine

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, general administrative support, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

Statement of Informed Consent: No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscript

Disclosures & Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1). Lawn JE, Blencowe H, Waiswa P, et al. Stillbirths: rates, risk factors, and acceleration towards 2030. Lancet. 2016. Feb 6; 387(10018):587–603. PMID: 26794078. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)00837-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Stillbirth Collaborative Research Network Writing Group. Causes of death among stillbirths. JAMA. 2011. Dec 14; 306(22):2459–68. PMID: 22166605. PMCID: PMC4562291. 10.1001/jama.2011.1823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Meteor: metadata online registry [Internet]. Canberra: Australian Institute of Health and Welfare; c2019. Stillbirth (fetal death); 2018 [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: http://meteor.aihw.gov.au/content/index.phtml/itemId/482008. [Google Scholar]

- 4). Sands New Zealand [Internet]. Hamilton (NZ): Sands New Zealand; c2019. New Zealand definitions/terminology: stillbirth; [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: http://www.sands.org.nz/help-terminology.html#. [Google Scholar]

- 5). Centers for Disease Control and Prevention [Internet]. Atlanta: U.S. Department of Health & Human Services; c2019. Stillbirth; [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.cdc.gov/ncbddd/stillbirth/facts.html. [Google Scholar]

- 6). NHS [Internet]. London: Department of Health and Social Care; c2019. Stillbirth; [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.nhs.uk/conditions/stillbirth/. [Google Scholar]

- 7). Reeske A, Kutschmann M, Razum O, Spallek J. Stillbirth differences according to regions of origin: an analysis of the German perinatal database, 2004-2007. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2011. Sep 21; 11:63. PMID: 21936931. PMCID: PMC3188470. 10.1186/1471-2393-n-63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Mohangoo AD, Buitendijk SE, Szamotulska K, et al. Gestational age patterns of fetal and neonatal mortality in Europe: results from the Euro-Peristat project. PLoS One. 2011;6(11):e24727. PMID: 22110575. PMCID: PMC3217927. 10.1371/journal.pone.0024727. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare [Internet]. Tokyo: Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare; c2019. Outline of vital statistics in Japan; [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.mhlw.go.jp/english/database/db-hw/outline/index.html. [Google Scholar]

- 10). Hu IJ, Chen PC, Jeng SF, et al. A nationwide survey of risk factors for stillbirth in Taiwan, 2001-2004. Pediatr Neonatol. 2012. Apr; 53(2): 105–11. PMID: 22503257. 10.1016/j.pedneo.2012.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11). Aminu M1, Unkels R, Mdegela M, et al. Causes of and factors associated with stillbirth in lowand middle-income countries: a systematic literature review. BJOG. 2014. Sep; 121 Suppl 4:141–53. PMID: 25236649. 10.1111/1471-0528.12995. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12). Ray JG, Urquia ML. Risk of still birth at extremes of birth weight between 20 to 41 weeks gestation. J Perinatol. 2012. Nov; 32(11):829–36. PMID: 22595964. 10.1038/jp.2012.60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13). Royal College of Midwives [Internet]. London: Royal College of Midwives; c2019. How to…perform an examination of the placenta; 2011. [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: https://www.rcm.org.uk/news-views-and-analysis/analysis/how-to…perform-an-examination-of-the-placenta. [Google Scholar]

- 14). Kent AL, Dahlstrom JE. Placental assessment: simple techniques to enhance best practice. Aust N Z J Obstet Gynaecol. 2006. Feb; 46(1):32–7. PMID: 16441690. 10.1111/j.1479-828X.2006.00511.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15). Baergen RN. Manual of Pathology of Human Placenta. 2nd ed. New York: Springer; 2011. 544 p. [Google Scholar]

- 16). Thompson J, Irgens L, Skjaerven R, Rasmussen S. Placenta weight percentile curves for singleton deliveries. BJOG. 2007. Jun; 114(6):715–20. PMID: 17516963. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.2007.01327.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17). Balkawade NU, Shinde MA. Study of length of umbilical cord and fetal outcome: a study of 1,000 deliveries. J Obstet Gynaecol India. 2012. Oct; 62(5):520–5. PMID: 24082551. PMCID: PMC3526711. 10.1007/s13224-012-0194-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18). Linde LE, Rasmussen S, Kessler J, Ebbing C. Extreme umbilical cord lengths, cord knot and entanglement: Risk factors and risk of adverse outcomes, a population-based study. PLoS One. 2018. Mar 27; 13(3):e0194814. PMID: 29584790. PMCID: PMC5870981. 10.1371/journal.pone.0194814. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19). Parast MM, Crum CP, Boyd TK. Placental histologic criteria for umbilical blood flow restriction in unexplained stillbirth. Hum Pathol. 2008. Jun; 39(6):948–53. PMID: 18430456. 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.10.032. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20). Khong TY, Mooney EE, Ariel I, et al. Sampling and definitions of placental lesions: Amsterdam Placental Workshop Group consensus statement. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2016. Jul; 140(7):698–713. PMID: 27223167. 10.5858/arpa.2015-0225-CC. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21). Gold KJ, Abdul-Mumin AS, Boggs ME, et al. Assessment of “fresh” versus ‘‘macerated” as accurate markers of time since intrauterine fetal demise in low-income countries. Int J Gynaecol Obstet. 2014. Jun; 125(3):223–7. PMID: 24680841. PMCID: PMC4025909. 10.1016/j.ijgo.2013.12.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22). Shanklin DR. Fetal maceration. 2. An analysis of 53 human stillborn infants. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1964. Jan 15; 88:224–9. PMID: 14104785. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23). Woods R. Long-term trends in fetal mortality: implications for developing countries. Bull World Health Organ. 2008. Jun; 86(6):460–6. PMID: 18568275. PMCID: PMC2647461. 10.2471/blt.07.043471. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24). National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit (NPESU) [Internet]. Sydney: UNSW Medicine - National Perinatal Epidemiology and Statistics Unit; c2019. Stillbirths in Australia 1991-2009; [cited 2018 Nov 23]. Available from: https://npesu.unsw.edu.au/surveillance/stillbirths-australia-1991-2009. [Google Scholar]

- 25). Huang DY, Usher RH, Kramer MS, et al. Determinants of unexplained antepartum fetal deaths. Obstet Gynecol. 2000. Feb; 95(2): 215–21. PMID: 10674582. 10.1016/s0029-7844(99)00536-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26). Ptacek I, Sebire NJ, Man JA, et al. Systematic review of placental pathology in association with stillbirth. Placenta. 2014. Aug; 35(8): 552–62. PMID: 24953162. 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.05.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27). Reddy UM, Goldenberg R, Silver R, et al. Stillbirth classification-developing an international consensus for research: executive summary of a National Institute of Child Health and Human Development workshop. Obstet Gynecol. 2009. Oct; 114(4):901–14. PMID: 19888051. PMCID: PMC2792738. 10.1097/AOG.0b013e3181b8f6e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28). Fox H. Morphological changes in the human placenta following fetal death. J Obstet Gynaecol Br Commonw. 1968. Aug; 75(8):839–43. PMID: 5673327. 10.1111/j.1471-0528.1968.tb01602.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29). Stanek J. Hypoxic patterns of placental injury. Arch Pathol Lab Med. 2013. May; 137(5):706–20. PMID: 23627456. 10.5858/arpa.2011-0645-RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30). Marchetti D, Belviso M, Marino M, Gaudio R. Evaluation of the placenta in a stillborn fetus to estimate the time of death. Am J Forensic Med Pathol. 2007. Mar; 28(1):38–43. PMID: 17325462. 10.1097/01.paf.0000257416.68211.20. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31). Zeng J, Marcus A, Buhtoiarova T, Mittal K. Distribution and potential significance of intravillous and intrafibrinous particulate microcalcification. Placenta. 2017. Feb; 50:94–98. PMID: 28161068. 10.1016/j.placenta.2017.01.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32). Heifetz SA. Thrombosis of the umbilical cord: analysis of 52 cases and literature review. Pediatr Pathol. 1988; 8(1):37–54. 10.3109/15513818809022278. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33). McClure EM, Dudley DJ, Reddy UM, Goldenberg RL. Infectious causes of stillbirth: a clinical perspective. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2010. Sep; 53(3):635–45. PMID: 20661048. PMCID: PMC3893929. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e3181eb6620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34). Folgosa E, Gonzalez TC, Osman NB, et al. A case control study of chorioamniotic infection and histological chorioamnionitis in stillbirth. APMIS. 1997. Apr; 105(4):329–36. PMID: 9164478. 10.1111/j.1699-0463.1997.tb00578.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35). Hay PE, Lamont RF, Taylor-Robinson D, et al. Abnormal bacterial colonisation of the genital tract and subsequent preterm delivery and late miscarriage. BMJ. 1994. Jan 29; 308(6924):295–8. PMID: 8124116. PMCID: PMC2539287. 10.1136/bmj.308.6924.295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36). Delprado WJ, Baird PJ, Russell P. Placental candidiasis: report of three cases with a review of the literature. Pathology. 1982. Apr; 14(2):191–5. PMID: 7099725. 10.3109/00313028209061293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37). Vazquez-Boland JA, Krypotou E, Scortti M. Listeria placental infection. MBio. 2017. Jun 27; 8(3). pii: e00949–17. PMID: 28655824. PMCID: PMC5487735. 10.1128/mBio.00949-17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38). Redline RW. Villitis of unknown etiology: noninfectious chronic villitis in the placenta. Hum Pathol. 2007. Oct; 38(10):1439–46. PMID: 17889674. 10.1016/j.humpath.2007.05.025. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39). Pathology of the human placenta. 6th ed. Berlin: Springer; c2012. Chapter 20, Infectious diseases; p. 557–656. [Google Scholar]

- 40). Lepais L, Gaillot-Durand L, Boutitie F, et al. Fetal thrombotic vasculopathy is associated with thromboembolic events and adverse perinatal outcome but not with neurologic complications: a retrospective cohort study of 54 cases with a 3-year follow-up of children. Placenta. 2014. Aug; 35(8):611–7. PMID: 24862569. 10.1016/j.placenta.2014.04.012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41). Sasidharan CK, Anoop P. Anencephaly with placental attachment. Indian J Pediatr. 2002. Nov; 69(11):991–2. PMID: 12503669. 10.1007/bf02726023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42). Farquhar CM, Li Z, Lensen S, et al. Incidence, risk factors and perinatal outcomes for placenta accreta in Australia and New Zealand: a case-control study. BMJ Open. 2017. Oct 5; 7(10):e017713. PMID: 28982832. PMCID: PMC5640005. 10.1136/bmjopen-2017-017713. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43). Dudley DJ. Diabetic-associated stillbirth: incidence, pathophysiology, and prevention. Clin Perinatol. 2007. Dec; 34(4):611–26, vii. PMID: 18063109. 10.1016/j.clp.2007.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44). Russo FM, Pozzi E, Pelizzoni F, et al. Stillbirths in singletons, dichorionic and monochorionic twins: a comparison of risks and causes. Eur J Obstet Gynecol Reprod Biol. 2013. Sep; 170(1):131–6. PMID: 23830966. 10.1016/j.ejogrb.2013.06.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]