Abstract

Acute intravascular hemolysis is a rare and often lethal complication of Clostridium perfringens septicemia.Clostridium perfringens is an anaerobic, gram-positive spore-forming rod which is commonly implicated in cases of food poisoning, gas gangrene, and severe hemolytic anemia in humans via the alpha-toxin (phospholipase C). We report an interesting and rare case of a 72-year-old woman who developed massive intravascular hemolysis secondary to C perfringens bacteremia in the setting of poorly differentiated high-grade endometrial malignancy.

Keywords: Forensic pathology, Clostridium perfringens, Bacteremia, Acute hemolytic anemia, Endometrial malignancy

Case

The decedent was a 72-year-old woman with a history of type 2 diabetes, hypertension, hyperlipidemia, third-degree heart block with pacemaker, and gastroesophageal reflux disease who initially presented with left-sided weakness and altered mental status. The decedent was also noted to have hematuria and urinary incontinence on arrival and stated that she had been having several months of “bloody urine.” Prior to her arrival at the emergency department, she was found with sheets saturated in blood at home. Hemoglobin on admission was noted to be 7.7 g/dL down from 10 g/dL several months prior. Additional testing was suggestive of hemolytic anemia including an elevated D-dimer and peripheral smear. Workup for stroke was inconclusive with nonspecific changes on computed tomography imaging. The decedent’s status continued to decline and she was transferred to the intensive care unit. Of note, her white blood cell count was elevated (18.24 K/mm3). Upon arrival in the intensive care unit, her respiratory status and effort had worsened and extensive resuscitative efforts were unsuccessful, and she ultimately passed away. An autopsy was requested and performed the morning after her death.

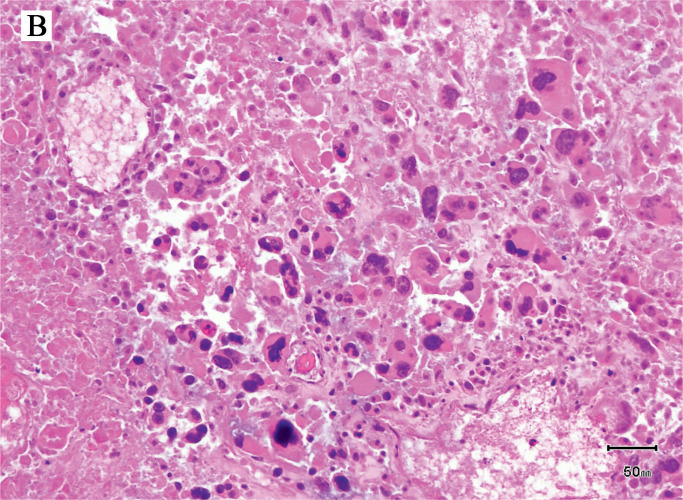

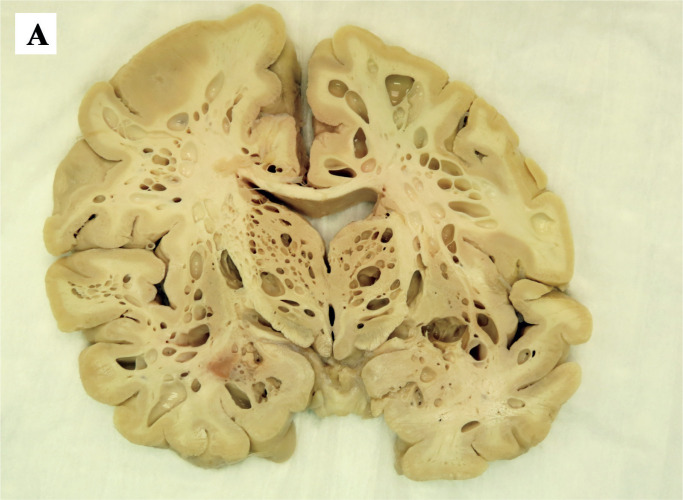

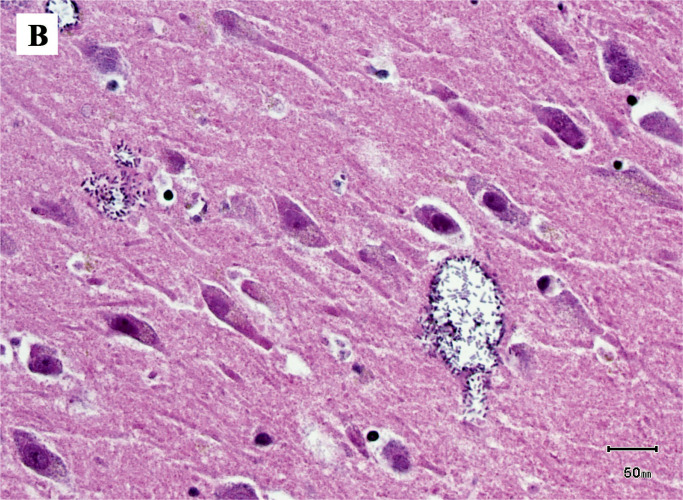

The most significant findings on autopsy included viscera showing accelerated decompositional change with diffuse softening and intraparenchymal and intraluminal gas accumulation. Diffuse green-yellow skin discoloration with sloughing and blebbing was observed. Notably, the uterus was bivalved to reveal a red, shaggy/fungating, hemorrhagic mass carpeting the endometrium, and sections through the brain revealed diffuse vacuolization. Image 1 demonstrates the presence of rod-shaped bacteria within the parenchyma of the endometrium among necrotic tissue and some viable malignant cells. The malignant cells are discohesive and show bizarre pleomorphic nuclei, with no discernible differentiation. Image 2 demonstrates the presence of colonies of rod-shaped bacteria within the brain with associated diffuse parenchymal gas accumulation. These findings correspond with antemortem blood cultures that were positive for C Perfringens. The cause of death in this patient, based on clinical pathological correlation, is C perfringens bacteremia in the setting of poorly differentiated highgrade endometrial malignancy. Furthermore, the manner of death was deemed natural.

Image 1A:

Bulging uterus revealed upon opening the abdominal cavity.

Image 1B:

Photomicrograph of uterus showing some viable tumor cells and bacteria in the background (H&E, x400).

Image 2A:

Representative coronal cross-section of the brain demonstrating diffuse parenchymal emphysema.

Image 2B:

Clostridium perfringens within the brain parenchyma (H&E, x400).

Discussion

Prior to the legalization of abortion in the United States, the risk of infectious morbidity and mortality as a result of C perfringens infections remained quite high. Since then, that risk has dramatically fallen, but the severity of such infections is maintained (1). Though we recognize the risk of these infections in the peripartum period, one must also consider the ability for Clostridium species to flourish in the setting of degenerating malignancy. To date, there are only a few case reports of C perfringens infections associated with benign (2 –4) and malignant uterine abnormalities (5). While the literature of acute hemolytic anemia due to Clostridium is established, the relationship to endometrial malignancy is still quite sparse.

Clostridium perfringens is a gram-positive, encapsulated, anaerobic bacillus that is notable for the production of alpha toxin. This toxin is an enzyme that cleaves lecithin into its more constitutive products, phosphocholine and diglyceride. Due to the effects on the integrity of the red blood cell membrane, this mechanism is thought to explain the development of spherocytosis and hemolysis in the setting of frank Clostridial infection (6).

The widespread nature of Clostridium species is owed to their ability to form endospores. Though rare, sepsis caused by C perfringens carries significant mortality with rates ranging from 27% to 58% (7). It can cause gas gangrene in infections and, when present postmortem, causes diffuse tissue emphysema, as is seen in this case. Clostridium perfringens is part of the normal vaginal flora in 1% to 10% of healthy women, and it is thought that most uterine C perfringens infections are secondary to ascension of bacteria from the vagina or introduction by instrumentation (8, 9). Symptomatic infections with C perfringens can range from a mild endometritis or present with fulminant septicemia, as was seen in this patient. In the gynecologic cancer patient, the microenvironment within tumors creates a location particularly well suited for the growth of Clostridium owing to the necrotic and hypoxic conditions that can be found there (10). In this environment, the release and effects of exotoxins can start having fatal effects in as little as 12 hours making it exceedingly difficult to diagnose and treat in a timely manner (7).

Findings most consistent with Clostridial sepsis include a quick decline that eventually leads to multi-organ failure. Since patients can die within hours of presentation, the cornerstone of treatment includes early recognition and aggressive treatment with broad-spectrum antibiotics and surgical debridement (7). For gas gangrene, hyperbaric oxygen used in conjunction with surgery and antibiotics has been shown to have marked effects. This is due to the ability of the alpha toxin produced by the bacteria to be suppressed by the oxygen, with residual alpha toxin being fixed in tissues (10). In patients with known or suspected pelvic or gastrointestinal malignancy in the setting of sepsis, C perfringens infection should be considered in a differential diagnosis, and empiric antibiotics should be started immediately.

Conclusion

In light of the historical, gross, and microscopic findings, we conclude that the decedent died as a result of C perfringens bacteremia causing overwhelming disseminated infection and associated acute hemolytic anemia in the setting of a poorly differentiated endometrial malignancy. This case is one of a few reported cases of C perfringens bacteremia presenting as acute intravascular hemolysis in the setting of endometrial malignancy.

Authors

Luke R. Cypher MD PhD, Medical University of South Carolina - Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, general supervision, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Christopher Sullivan MPH, Geisinger Community Medical Center - College of Medicine

Roles: Project conception and/or design, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Ryan Jones MD, Medical University of South Carolina - Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Roles: Data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Angelina Phillips MD, Medical University of South Carolina - Pathology and Laboratory Medicine

Roles: Project conception and/or design, data acquisition, analysis and/or interpretation, manuscript creation and/or revision, approved final version for publication, accountable for all aspects of the work, general supervision, writing assistance and/or technical editing.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval: As per Journal Policies, ethical approval was not required for this manuscript

Statement of Human and Animal Rights: This article does not contain any studies conducted with animals or on living human subjects

Statement of Informed Consent: No identifiable personal data were presented in this manuscript

Disclosures & Declaration of Conflicts of Interest: The authors, reviewers, editors, and publication staff do not report any relevant conflicts of interest

Financial Disclosure: The authors have indicated that they do not have financial relationships to disclose that are relevant to this manuscript

References

- 1). Dempsey A. Serious infection associated with induced abortion in the United States. Clin Obstet Gynecol. 2012. Dec; 55(4):888–92. PMID: 23090457. 10.1097/GRF.0b013e31826fd8f8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2). Kaufmann BM, Cooper JM, Cookson P. Clostridium perfringens septicemia complicating degenerating uterine leiomyomas. Am J Obstet Gynecol. 1974. Mar 15; 118(6):877–8. PMID: 4361157. 10.1016/0002-9378(74)90506-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3). Bryant CS, Perry L, Shah JP. et al. Life-threatening clostridial sepsis in a postmenopausal patient with degenerating uterine leiomyoma. Case Rep Med. 2010; 2010:541959. PMID: 20585368. PMCID: PMC2878686. 10.1155/2010/541959. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4). Kao MJ, Roy M, Harter J, Spencer RJ. Uterine sarcoma presenting with sepsis from clostridium perfringens endometritis in a postmenopausal woman. Case Rep Obstet Gynecol. 2018. Apr 16; 2018:8217296. PMID: 29850320. PMCID: PMC5926516. 10.1155/2018/8217296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5). Kremer KM, McDonald ME, Goodheart MJ. Uterine Clostridium perfringens infection related to gynecologic malignancy. Gynecol Oncol Rep. 2017. Sep 21; 22:55-7. PMID: 29034307. PMCID: PMC5635240. 10.1016/j.gore.2017.09.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6). Ohtani S, Watanabe N, Kawata M. et al. Massive intravascular hemolysis in a patient infected by a Clostridium perfringens. Acta Med Okayama. 2006. Dec; 60(6):357–60. PMID: 17189980. 10.18926/AMO/30725. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7). Halpin TF, Molinari JA. Diagnosis and management of clostridium perfringens sepsis and uterine gas gangrene. Obstet Gynecol Surv. 2002. Jan; 57(1):53–7. PMID: 11773832. 10.1097/00006254-200201000-00024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8). Leal J, Gregson DB, Ross T. et al. Epidemiology of clostridium species bacteremia in Calgary, Canada, 2000-2006. J Infect. 2008. Sep; 57(3):198–203. PMID: 18672296. 10.1016/j.jinf.2008.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9). Cohen AL, Bhatnagar J, Reagan S. et al. Toxic shock associated with Clostridium sordellii and Clostridium perfringens after medical and spontaneous abortion. Obstet Gynecol. 2007. Nov; 110(5):1027–33. PMID: 17978116. 10.1097/01.AOG.0000287291.19230.ba. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10). Tönjum S, Digranes A, Alho A. et al. Hyperbaric treatment in gas-producing infections. Acta Chir Scand. 1980; 146(4):235–41. PMID: 7468048. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]