Abstract

The role of the adipocyte in the tumor microenvironment has received significant attention as a critical mediator of the obesity-cancer relationship. Current estimates indicate that 650 million adults have obesity, and thirteen cancers, including breast cancer, are estimated to be associated with obesity. Even in people with a normal body mass index, adipocytes are key players in breast cancer progression because of the proximity of tumors to mammary adipose tissue. Outside the breast microenvironment, adipocytes influence metabolic and immune function and produce numerous signaling molecules, all of which affect breast cancer development and progression. The current epidemiologic data linking obesity, and importantly adipose tissue, to breast cancer risk and prognosis, focusing on metabolic health, weight gain, and adipose distribution as underlying drivers of obesity-associated breast cancer is presented here. Bioactive factors produced by adipocytes, both normal and cancer associated, such as cytokines, growth factors, and metabolites, and the potential mechanisms through which adipocytes influence different breast cancer subtypes are highlighted.

During their lifetime, 1 in 8 women will be diagnosed with breast cancer and approximately 1 in 39 women will die of this disease. In 2020 alone, an estimated >300,000 cases of invasive and in situ breast cancer will be diagnosed.1 Risk factors include those that cannot be changed (eg, being female, older age, inherited genetic mutations) and those that are considered modifiable (eg, physical activity levels, alcohol consumption, obesity). In 2016, >1.9 billion adults were considered overweight. Of these, >650 million were considered obese.2 In the United States, obesity prevalence has approached 40% in adults3 and 17% in children.4 These dire statistics present a health care crisis because obesity predisposes individuals of all ages to a variety of health problems, including diabetes, hepatic steatosis, cardiovascular disease, and cancer. Thirteen cancer types are now considered to be associated with obesity–,5 including esophageal, gastric, colon and rectal, liver, gallbladder, pancreatic, corpus uterine, ovarian, renal cell, meningioma, thyroid, multiple myeloma, and postmenopausal breast cancers.5 Given the breadth of obesity-associated cancers, it is not surprising that numerous mechanisms have been cited.

Strong epidemiologic evidence indicates that obesity is linked with breast cancer incidence and prognosis. Importantly, the association between obesity and breast cancer in postmenopausal women remains even after adjusting for metabolic status; in other words, metabolically healthy women with obesity have an elevated risk of breast cancer.6 However, premenopausal breast cancer is not yet considered one of the obesity-associated cancers,5,6 and a high body mass index (BMI) may actually predict a decreased risk of breast cancer in young women7; however, this paradox remains poorly understood. This article primarily focuses on postmenopausal breast cancer. Clinically, breast tumors are categorized into 3 subtypes, which inform treatment options; however, several molecular (eg, luminal A, luminal B, claudin low) and histologic (eg, lobular, ductal) subtypes have been identified that may have distinct origins. Most tumors (>70%; >150,000 cases per year) express the estrogen and/or progesterone receptor and are frequently diagnosed in postmenopausal women.8 Approximately 15% of tumors express the human epidermal growth factor receptor 2, whereas the remaining 15% lack all three receptors and are classified as triple-negative breast cancer.8 The risk of a breast cancer diagnosis associated with obesity is greatest for the estrogen receptor (ER)/progesterone receptor–positive subtype,9 especially after menopause. One meta-analysis reported a 12% increase in postmenopausal breast cancer risk associated with every 5-kg/m2 increase in BMI.10 Obesity is associated with advanced breast cancer at diagnosis,9,11 including larger, higher-grade tumors and lymph node involvement.9,11,12 The American Cancer Society Cancer Prevention Study II found that breast cancer mortality is progressively elevated with increasing BMI, such that women with BMI ≥40 kg/m2 are more than twice as likely to die of breast cancer than those who have a normal BMI.13 Studies focused on the link between obesity and breast cancer–specific mortality have found that excess weight predicts increased risk of death from breast cancer and impairs response to treatment13; however, this relationship may be strongest for hormone receptor–positive breast cancers.9,13 Thus, there is still an unmet need for a better understanding of the relationship between obesity and underlying drivers of breast cancer initiation and progression, keeping in mind age, menopausal status, and tumor subtype as critical variables that influence specific mechanisms.

Obesity is characterized by excess adipose tissue throughout the body. Adipose is a dynamic organ that plays several important roles in physiology, including storing excess energy in the form of lipid, signaling locally and to distant organs through secreted proteins, providing protection to internal organs, and facilitating body temperature regulation. In addition to adipocytes, adipose depots contain fibroblasts, preadipocytes, vascular cells, nerve cells, immune cells, and extracellular matrix proteins, all of which participate in a complex network of communication. The increased prevalence of obesity and associated comorbidities has resulted in a scientific understanding that adipose tissue, like many other organs in the body, can become sick. In fact, many obesity-associated cancers occur in organs are located adjacent to or within adipose depots, including breast cancer. Adipocytes are a major component of the breast tumor microenvironment; however, adipocytes found throughout the body can influence breast cancer through mechanisms similar to those found near the tumor. Thus, this review focuses on the tumor-promotional role of adipose tissue, emphasizing the contribution of adipocytes both within and outside the tumor microenvironment to breast cancer risk and progression.

Estrogen is not Necessarily the Only Driver of Breast Cancer in Obesity

In humans, adipose tissue is a biologically significant source of estrogen after the loss of ovarian function, so obesity-associated estrogen likely plays a critical role in breast cancer growth. The aromatase enzyme, encoded by CYP19A1 expressed in stromal fibroblasts and immune cells within adipose tissue, converts androgens into estrogens. Women with obesity have elevated levels of estrone and estradiol.14,15 Although overall cases are much lower than the number of cases in females only, breast cancer risk in males is positively associated with obesity and estrogen levels.16 Higher local or circulating levels of estrogens in obesity may be responsible for driving ER-positive tumor growth and may partly explain the elevated risk associated with BMI17; however, in postmenopausal women, aromatase inhibitors decrease circulating estrogen levels by 85% to 95% regardless of BMI, resulting in plasma estradiol concentrations below clinically relevant levels (<10 pM) that may retain biological activity.14 In this environment (ie, after antiestrogen therapy), the tumor promotional effects of obesity are maintained,18,19 but elevated estrogen concentrations may not be the easy explanation.20 Indeed, clinical studies have found no added benefit to tumor response with high versus low levels of aromatase inhibitor treatment,21,22 suggesting that increasing the standard dose may not improve breast cancer–specific prognosis in women with obesity. This finding implies that factors besides or in addition to estrogen may be responsible for obesity-associated breast cancer progression and could partially explain why obesity worsens breast cancer outcomes, which may not be overcome by attempting to further lower estrogen levels. Although mouse models are commonly used to study breast cancer, the role of adipose-derived estrogen in mice remains controversial. Some studies in mouse models demonstrate adipose-specific Cyp19a1 gene expression or aromatase enzyme activity associated with diet-induced obesity,23,24 whereas others have found no detectable aromatase or estradiol in adipose tissue (specifically mammary adipose) from ovariectomized obese females.25, 26, 27 Discrepancies in study outcomes could be attributable to differences in mouse strain, age, or methods used to measure gene or protein levels but suggest that the ovariectomized female mouse could represent a useful model of the human environment after menopause and endocrine therapy for which estrogen may not be the only driving factor for breast cancer.

Looking Beyond BMI

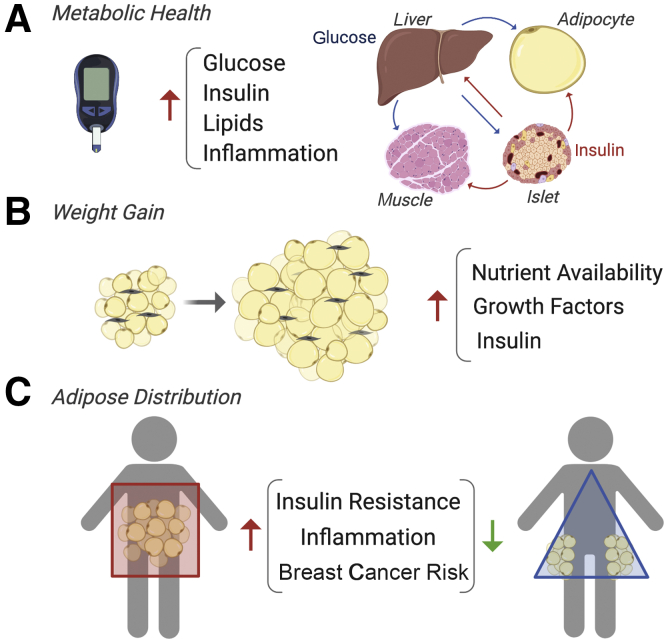

Although BMI is a standardized measurement that is easy to collect and frequently reflects excess adipose tissue, it may not be a perfect predictor of breast cancer risk or outcomes, even when excluding the contribution of nonmodifiable factors (ie, in the absence of genetic mutations). Two large clinical studies (the Women's Health Initiative and the Study of Tamoxifen and Raloxifene) reported that 40.8% and 37.1% of women with breast cancer had obesity, respectively.12,28 Additionally, the National Surgical Adjuvant Breast and Bowel Project reported that 30.1% of postmenopausal women with breast cancer had obesity.28 Based on these three trials, approximately 29% to 40% of women have an elevated BMI (≥30 kg/m2) at the time of breast cancer diagnosis, which is comparable to percentages reported in general analyses of obesity prevalence (eg, 36.5% to 44.7%, depending on age group).3 Overall, this finding indicates that simply measuring BMI is not sufficient to capture the population at risk for breast cancer, potentially because of complex underlying drivers. On the other hand, the prevalence of obesity and breast cancer provides the opportunity to perform large epidemiologic studies aimed at looking beyond BMI for further clarification on drivers of obesity-associated breast cancer. Three underlying variables of the obesity-cancer relationship include metabolic syndrome, adult weight gain, and adipose tissue distribution (Figure 1). Metabolic syndrome and weight gain are particularly linked to the risk of several of the aforementioned obesity-associated cancers.6,29 In a prospective cohort study, women with a normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) and one or more features of metabolic syndrome (eg, high waist circumference, elevated blood pressure, diabetes) had a similarly elevated risk for postmenopausal breast cancer as women who were metabolically healthy but were overweight or obese.30 A different study found that women classified as metabolically unhealthy based on the homeostatic model assessment of insulin resistance or fasting insulin levels had an elevated risk of breast cancer even with a normal BMI.31 Although obesity, regardless of metabolic health, is associated with breast cancer incidence, the contribution of metabolic syndrome may further increase risk.32 However, whether BMI or metabolic health is a more meaningful predictor of breast cancer incidence or outcome has not yet been distinguished. Moreover, the mechanisms described below are reported in studies in which BMI and metabolic function are not always explicitly separated, making it difficult to isolate the specific roles of excess adipose and metabolism.

Figure 1.

Factors beyond body mass index that predict breast cancer risk. Epidemiologic studies suggest that metabolic health (A), adult weight gain (B), and adipose tissue distribution (C) may drive obesity-associated breast cancer. Mechanisms include increased nutrients (glucose, lipids that traffic among liver, adipocytes, pancreas, and muscle), elevated insulin levels, growth factor production, and inflammation.

Insulin signaling is a commonly identified pathway in obesity, metabolic syndrome, and weight gain that may underlie breast cancer growth, particularly when hormone levels are elevated, as often seen before a diabetes diagnosis.33,34 Insulin decreases levels of sex hormone binding globulin,35 which increases levels of free circulating steroid hormones, particularly estradiol.34 Insulin and insulin-like growth factor 1 are potent mitogens for cancer cells36,37 and may also potentiate signaling through ER.36,38 In addition to acting as a growth factor, hyperinsulinemia may promote tumors by making nutrients available to rapidly dividing cancer cells. This process is illustrated in a rat model of carcinogen-induced postmenopausal breast cancer, where nutrient tracer studies revealed that diet-induced obesity facilitated mild insulin resistance in subcutaneous adipose, liver, and muscle, but not in cancer cells, resulting in tumor uptake of glucose and fatty acids and cancer progression.39 Tumor nutrient uptake was observed in obese but not lean female rats who overeate, experienced a high positive energy balance, and rapidly gained weight after the loss of ovarian hormones.39 In contrast, peripheral uptake of nutrients during overfeeding was relatively higher in liver, skeletal muscle, and mammary adipose tissue compared with tumors in lean rats. Notably, obese rats had elevated circulating insulin levels compared with lean rats, highlighting the potentially complex roles of insulin as a mitogen and in providing nutrients for growing tumors. The tumor-promotional effects of weight gain are documented in epidemiologic studies as well. Women who transitioned from a normal BMI (<25 kg/m2) to overweight or obese categories faced an increased risk of breast cancer compared with women who had overweight or obesity as young adults and did not gain >5% weight during approximately 13 years of follow-up.12 In addition, a meta-analysis estimates that every 5 kg of weight gain increases the risk of breast cancer by 11%.40

There is strong evidence that adipose tissue inflammation plays a role in obesity-associated breast cancer. Inflammation is a broad term but is often associated with the presence of crown-like structures (CLSs), which are formed when macrophages localize around a dying adipocyte and become activated. CLSs are present in approximately 50% of breast cancers, as measured by histologic analysis,41 and individuals who are CLS-positive have higher BMI than those who are CLS-negative. When adipocytes become hypertrophic in obesity to accommodate the increasing need for lipid storage, the effects include hypoxia and necrosis. CLS macrophages have been characterized by CD11c (Itgax) expression in mouse models of diet-induced obesity and represent a new macrophage phenotype that needs to be further explored.42,43 Adipose tissue inflammation is correlatively, and in some models causatively, linked to insulin resistance associated with obesity, potentially through NF-κB kinase subunit-β–NF-κB44 and/or c-Jun N-terminal kinase 1,45 and predicts a worse cancer prognosis.46 For example, tumor necrosis factor-α concentrations are elevated in adipose tissue during obesity, and neutralization antibody treatment of obese female rats improve peripheral insulin sensitivity.47 Since this report in 1993, many studies have found links between adipose-derived factors, such as proinflammatory cytokines or adipokines and insulin sensitivity in multiple organs.48 The communication between adipocytes and macrophages alters the tumor microenvironment and can directly influence nearby cancer cells; therefore, additional mechanisms that coexist with and may result from adipose tissue inflammation are described in more detail in the following sections.

The complexity of the effects of excess adiposity on inflammation and immunity is gleaned from studies on the effects of therapies in individuals with obesity. It has been well established that traditional therapies for breast cancer may be less efficacious in patients with obesity, but the outcomes of immunotherapy are less clear. Breast cancer cell line data demonstrate that adipocytes promote doxorubicin49 and paclitaxel resistance through their release of leptin,50 and attenuate the response to hormone therapy.51,52 In addition, adipocytes promote radiotherapy resistance.53,54 The effects of adipocytes on the newer immunotherapies in breast cancer are not yet known. In 2019 and 2020, the US Food and Drug Administration approved two separate checkpoint inhibitor immunotherapy drugs, anti–programmed cell death 1 (PD1) and programmed cell death ligand (PD-L1) antibodies, for the treatment of triple-negative metastatic breast cancer in patients whose tumors express the PD-L1 protein. PD-L1 binding to the PD1 receptor ensures that the immune cells will not be activated in response to the tumor, and is, therefore, immunosuppressive; these antibodies block this action. Animals on a high-fat diet have increased PD1+CD8+ T cells in their tumors compared with those in normal mice. Adipocytes release PD-L1 and saturate anti–PD-L1 antibodies to prevent them from activating important antitumor functions of CD8+ T cells in syngeneic mammary tumor models.55 Even though obesity causes a reduction in such effector immune populations, it has a beneficial effect on survival in patients undergoing anti–PD1/PD-L1 treatment for melanoma, non–small cell lung cancer, or renal cell carcinoma.56 This contradictory information highlights the need for a better understanding of adipocyte-immune-tumor interactions, which may help explain immunotherapeutic outcomes in breast cancer.57

Adipose Tissue Distribution

Not only does overall adiposity influence breast cancer risk, but also the depots in which excess adipose is stored play an important role in the development and progression of cancer. This finding may be underappreciated because adipose distribution can change while BMI remains stable, such as during the menopausal transition.58 Although obesity increases the risk of postmenopausal ER-positive breast cancer, it is associated with a decreased risk of premenopausal breast cancer,59 and the exception to this paradox may be explained, in part, by adipose distribution. Central obesity, which refers to excess adipose deposited in the visceral depots, has consistently been associated with increased risk of premenopausal triple-negative breast cancer.60 Central obesity is also associated with elevated postmenopausal breast cancer risk, even in the absence of metabolic disease.6 Of importance, central obesity is often classified based on the waist to hip ratio, which includes abdominal (ie, truncal) subcutaneous adipose in addition to visceral adipose in the waist measurement. Although numerous studies have implicated visceral adipose in metabolic health risks, others have found that excess abdominal subcutaneous adipose tissue (SAT) may more accurately be associated with insulin resistance.61 Breast tumors grow in the mammary fat pad, and although this pad has distinct functions from other white adipose depots, it is considered SAT.62 The proximity of breast cancer to mammary adipose tissue makes it difficult to discern the respective contribution of SAT and visceral adipose tissue (VAT) depots to breast cancer risk and progression. Because breast cancer consists of several biologically distinct subtypes with different origins, it is not surprising that its relationship with obesity is multifaceted. Understanding the role of VAT versus SAT in breast cancer incidence may clarify some of these complex links.

The SAT and VAT depots, under noncancer conditions, have different effects on whole-body metabolism. VAT is more sensitive to immune and inflammatory changes that accompany obesity.63 Almost all immune cell types are found in VAT. In rodent models, obesity driven by genetics or diet increases the numbers of VAT T cells, B cells, macrophages, mast cells, and neutrophils. In contrast, the numbers of anti-inflammatory immune cells are decreased, including invariant natural killer T cells, Th2 T cells, and T-regulatory cells. Macrophages are the most abundant immune cells in adipose tissue and can increase up to 50% in the VAT in both humans with obesity and mouse models of obesity.64 Humans with obesity have twice as many macrophages in omental adipose tissue compared with SAT.65 In humans with a normal BMI, VAT macrophages have predominately the anti-inflammatory M2 phenotype, whereas in obesity they have predominately the proinflammatory M1 phenotype. Several excellent reviews have discussed the immunologic profile of VAT.66,67 Although inflammation is important for the metabolic syndrome associated with excess VAT, the primary events that trigger VAT inflammation in obesity are unclear. Intra-abdominal lipectomy reverses insulin resistance and glucose intolerance in obese rodents.68, 69, 70, 71 Adipose tissue transplantation studies have collectively suggested that total VAT mass is not as critical as the quality of the VAT. Transplantation of SAT into the visceral cavity improves insulin sensitivity and glucose tolerance in mice.72 In addition, individuals with a greater capacity to form new subcutaneous adipocytes typically have beneficial metabolic health in obesity.73 Although studies in humans are difficult and controversial, omental adipose tissue reduction improves insulin sensitivity.74 Overall, these studies suggest that VAT (ie, adipose distribution) may be a key contributor to breast cancers that are driven by metabolically unhealthy obesity. Although visceral adipocytes are, by definition, not part of the breast tumor microenvironment, they ultimately influence cancer cell growth, even from a distance. In contrast, SAT or mammary adipose specifically can also influence breast cancer cells directly but through similar biological mediators to VAT.

Bioactive Factors from Adipocytes

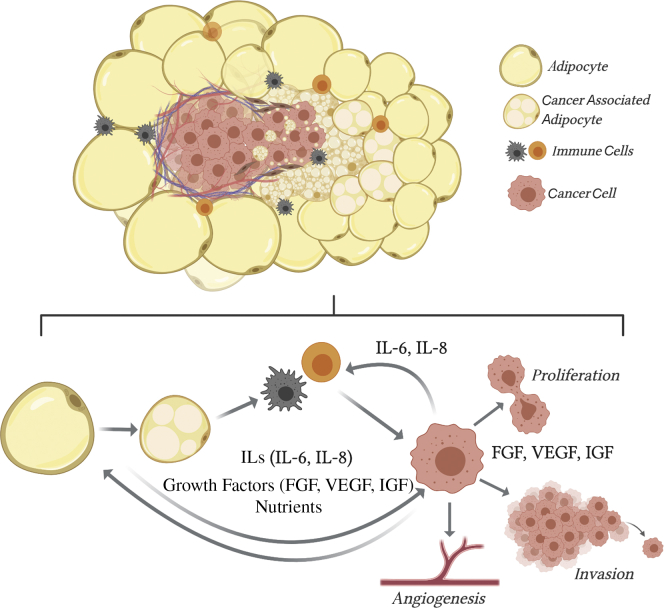

The invasive fronts of breast tumors are often surrounded by adipocytes75 that may delipidate or dedifferentiate over time76,77 to adopt a cancer-associated fibroblast morphology (Figure 2). The close contact between breast cancer cells and adipocytes alters each in such a way that the cancer-associated adipocyte has a unique phenotype as well as gene expression and secretory profile.75,78 Tumor cells cultured with adipocytes have enhanced invasive potential, and each cell type demonstrates metabolic adaptations that support tumor progression.79 Obesity may support breast cancer risk or progression by producing adipocytes that mimic the cancer-associated adipocyte phenotype, through secretion of proinflammatory cytokines, growth factors, and extracellular matrix proteins, and providing abundant nutrients,80 thereby accelerating the growth of early- and later-stage tumors.

Figure 2.

Adipocytes near a breast tumor participate in complex communication. The invasive fronts of breast tumors are surrounded by adipocytes that become smaller the closer they are to cancer cells. They transfer lipids, cytokines [eg, interleukin (IL) 6 and IL-8], and growth factors [eg. fibroblast growth factor (FGF), insulin-like growth factor (IGF), and vascular endothelial growth factor (VEGF)] to the environment and cancer cells, which promote breast cancer proliferation, invasion, and facilitate angiogenesis. Both adipocytes and cancer cells recruit immune cells, which facilitate tumor progression.

Cytokines and Growth Factors

Adipocytes not only store excess nutrients but they also synthesize and secrete numerous biological factors, such as cytokines and growth factors, that communicate locally and systemically with organs as well as tumors. Production of these factors is influenced by adipocyte size, location, and changes in energy balance and metabolic health. In many cases, the local interactions among adipocytes, immune cells, and tumor cells support therapy resistance, angiogenesis, and immune evasion. Adipocytes secrete cytokines that stimulate immune cell recruitment and act directly on breast cancer cells to promote proliferation and invasion. In case of obesity, adipose tissue is often unhealthy, characterized by reduced vascular density, adipocyte hypertrophy, and low-grade inflammation.81,82 Inflammation in breast adipose tissue alters its quality and can affect early stages of breast cancer.82, 83, 84 Experimentally manipulating adipose tissue depots through diet, exercise, pharmacologic, or surgical interventions, has provided researchers with several hypotheses about underlying mechanisms linking adipose distribution to breast cancer risk and progression. Patients with breast cancer and obesity are reported to have elevated levels of IL-6 and fibroblast growth factor (FGF)-2, as seen in a murine model of obesity and breast cancer, to facilitate resistance to anti–vascular endothelial growth factor therapies.81 Both IL-6 and FGF-2 correlate with the VAT area in patients and are localized to adipocyte-rich regions within breast tumor sections.81 Parametrial VAT lipectomy reduces the circulating levels of FGF-2 and IL-6 in high-fat diet–fed mice.85,86 Recently, FGF-2 was reported to activate ER in breast cancer cells independent of estrogen ligands, potentially contributing to tamoxifen resistance.87 In addition to promoting therapy resistance,81,87 FGF-2 alone and FGFs with IL-6 synergize to promote the malignant transformation of mammary epithelial cells in vitro.88,89

Separate studies have implicated cytokines, including leptin, IL-6, and IL-8, from adipose depots local to and distant from the tumor, in breast cancer risk, cell proliferation and migration,90,91 and tumor resistance to therapies that target angiogenesis or ER.81,92 In some cases, signals from adipocytes are communicated to infiltrating immune cells (eg, neutrophils, macrophages, T cells)81,93 and directly to cancer cells (Figure 2). Leptin, IL-6, and IL-8 concentrations are frequently elevated in obesity in both clinical and preclinical models, and are produced by cancer-associated adipocytes.81,90,91 Crosstalk among adipocytes, immune cells, and cancer cells can facilitate immune evasion, angiogenesis, and cancer cell proliferation and invasion, suggesting the potential to therapeutically target nonepithelial tumor cells and the factors they produce.

Growth factors are often produced by adipose tissue, even in the relatively less harmful SAT, during the normal expansion that occurs with a long-term positive energy balance (ie, during weight gain). As part of their normal function, hypertrophic adipocytes that may have reached their capacity for nutrient storage communicate signals to adipocyte progenitors to expand and differentiate, offering more sites for lipid deposition.25,94 Two such signals, FGF1 and FGF2, classically activate FGF receptors (FGFRs). Recently, FGF1 was found to be produced by mature hypertrophic adipocytes and released through activation of the mechano-sensing ion channel Piezo1.94 In this way, FGF1 serves as a beneficial signal from hyperplastic adipocytes that are under mechanical tension to stimulate preadipocyte proliferation94; however, it can also potentially activate FGFR in local breast cancer cells. In a mouse model of obesity and ER-positive breast cancer, weight gain and insulin resistance after antiestrogen therapy associated with adipocyte hypertrophy and SAT/mammary FGF1 expression in women with obesity and in obese, but not lean, female mice.25 This finding corresponds to elevated phosphorylation of FGFR1 in ER-positive patient-derived xenograft tumors and in primary breast tumors, and with resistance to antiestrogen treatment.25 Inhibition of FGFR in obese female mice restores tumor sensitivity to estrogen deprivation.25 FGFR1 and FGFR2 amplifications occur in breast cancer, and activity of these signaling pathways has been implicated in resistance to breast cancer therapy.25,81,95,96 Together, these studies suggest putative mechanisms through which adipose tissue distribution, metabolic health, and weight gain can support early- or late-stage growth of breast cancer cells, and also emphasize the need to look beyond adipose-derived estrogen for mediators of breast cancer growth, particularly in obesity.

Lipid Mediators and Metabolites

Adipocytes not only secrete cytokines and growth factors, they also release lipids in the form of nonesterified fatty acids. Breast cancer cells require fatty acids for all biologic activities. Lipids influence breast cancer cells in two ways: they rewire metabolism for de novo lipid biosynthesis or they are taken up exogenously from the adipocyte microenvironment or the systemic circulation. Both preclinical and clinical studies demonstrate that lipids can modulate breast cancer. Co-culture of breast cancer cell lines with 3T3-L1 adipocytes deplete adipocyte triacylglycerol and enhance breast cancer cell proliferation.97 In 3T3-L1 obese adipocytes, modeled by increased lipid droplets and triacylglycerols, breast cancer cell proliferation is enhanced further.97 Moreover, these paracrine effects of lipids are amplified by breast cancer cells that secrete lipolytic enzymes, further promoting this cycle of lipid release and uptake.97 Adipocytes adjacent to breast cancer cells have smaller lipid droplets than nontumor adjacent adipocytes and express genes associated with browning or beigeing.98 Clinical studies have found that elevated circulating free fatty acid concentrations lead to impaired lipid homeostasis and metabolic disease.99 The endocrine-acting monounsaturated fatty acid C16:1n7-palmitoleate is associated with obesity100 and breast cancer risk.101 This free fatty acid may have indirect effects on tumorigenesis through its insulin-sensing function. In general, unfavorable serum lipid profiles (elevated lipid levels that favor a higher proportion of saturated fatty acids compared with monounsaturated or polyunsaturated fatty acids) are associated with diets high in saturated fats and abdominal obesity.102

Hypercholesterolemia is an indirect consequence of obesity. Total circulating cholesterol is associated with the increased risk of breast cancer as determined from a prospective analysis.103,104 Oxygenated metabolites of cholesterol have growth-stimulating activity in breast cancer cells. The cholesterol metabolite 27-hydroxycholesterol is a selective ER modulator that promotes the growth of ER-positive tumors in preclinical models105 and behaves as a partial ER agonist.106 Another cholesterol metabolite, 6-oxocholestan-3β,5α-diol, promotes the growth of tumors through the glucocorticoid receptor.107 Although there are many undisputed detrimental effects of hypercholesterolemia, the efficacy of statins for breast cancer prevention and treatment is still subject to controversy, suggesting still many unknown roles for cholesterol in breast cancer. Recent studies have found that lipophilic statins, such as fluvastatin and simvastatin, are beneficial and decrease the diagnosis of advanced-stage breast cancer108 and reduce breast cancer recurrence, especially in younger patients.109,110 Statins block the malignant transformation of human MCF10A breast cells by factors released from VAT.111 These studies suggest the potential for adipocyte-derived lipids and obesity-associated metabolites to exert a negative impact on breast cancer risk and prognosis.

Exosomes

Integral to the adipose tissue–cancer connection is the communication between tissues by direct contact or secreted soluble mediators. However, cell to cell communication through extracellular vesicles is emerging as a novel way in which adipose tissue may influence tumor physiology. Adipocyte-derived exosomes, extracellular vesicles of endosome origin that have known roles in whole body and lipid metabolism, may contribute directly to primary tumor progression and metastasis. Adipocyte exosomes drive melanoma tumor progression by stimulating migration and invasion in vitro, and mass spectrometry has found that most exosome proteins are involved in fatty acid oxidation.112 Furthermore, obesity in mice and humans is associated with an increase in adipocyte exosome shedding and enhanced fatty acid oxidation–associated melanoma cell migration.112

There is also evidence that exosomes in obesity can influence breast cancer initiation and progression. MCF10DCIS cells, a model for early-stage breast cancer, cultured with exosomes from 3T3-L1 preadipocytes have enhanced mammosphere formation and form larger tumors in the mammary fat pads of immune-deficient mice compared with control MCF10DCIS cells.113 MCF7 cells, ER-positive breast cancer cells, cultured with exosomes isolated from mesenchymal stem cell–differentiated adipocytes, have enhanced proliferation, invasion, and resistance to chemotherapy-stimulated apoptosis compared with untreated MCF7 cells.114 The growth-promoting effect of these mesenchymal stem cell–derived adipocyte exosomes is dependent on the hippo-signaling pathway.114 The presence of adipocyte exosomes is critical for the tumor-promoting effect of the adipocytes in an MCF7 tumor xenograft model as determined by depleting exosomes with GW4869, an inhibitor of exosome biogenesis and release.114 Moreover, MCF7 cells cultured with exosomes from women with obesity (N = 5) have enhanced cellular proliferation, migration, and invasion compared with cells cultured with that from normal weight women (N = 5).115

In addition to adipocyte and preadipocyte extracellular vesicles, adipose tissue mesenchymal stem cells release extracellular vesicles. Exosomes released from mesenchymal stem cells induce the migration of MCF7 cells, and this phenotype is associated with the activation of the WNT signaling pathway.116 Interestingly, exosomes isolated from the VAT of obese individuals contain miRNAs predicted to stimulate WNT/β-catenin activation by inhibiting negative regulators.117 These miRNAs are not enhanced in exosomes from lean individuals.117 Ten years after the discovery that miRNAs could be transported in exosomes,118 Thomou et al119 found that miRNA in adipose tissue exosomes affect gene expression at distant sites. This discovery was made by determining that exosomes from a donor mouse expressing exogenous miRNA could repress a reporter gene in the liver of an acceptor mouse.119 Because liver is often a site of metastasis, it would be interesting to investigate whether adipose tissue–derived exosomes could promote premetastatic niche formation. Exosomes from breast cancer cells also contain miRNAs (miR-126 and miR-144) that promote nearby adipocyte browning and catabolic release of metabolites.98 Although mechanistic and in vivo research is still lacking, initial in vitro and tumor xenograft studies suggest that adipose tissue–derived exosomes can have both paracrine and endocrine effects, contributing to cancer initiation and progression, and that obesity may emphasize this communication.

Reversibility of Obesity-Associated Breast Cancer Risk

The reviewed literature describes the effects of obesity on tumor promotion and progression, which begs the question, “Can fat loss or therapies that target adipocyte communication and signaling prevent or reverse obesity-associated breast cancer?” Reversal of obesity through surgery, pharmacologic interventions, diet, and/or exercise has been found in some cases to target the above-mentioned drivers of obesity-associated breast cancer, such as inflammation, adipocyte hypertrophy, and insulin resistance, and biological factors such as estrogens and insulin. Several large studies indicate that weight loss is associated with a lower risk of breast cancer,120,121 suggesting that reversing obesity may reduce breast cancer risk and extend disease-free survival.122 Although this is great news, one concern is that animal studies have demonstrated obesogenic memory in which adipose tissue inflammation exists even after weight loss.123 Preventing obesity from occurring in the first place may provide the greatest benefits to cancer incidences. Ideally, the effects of weight on cancer risk should be studied by enrolling thousands of individuals in a clinical trial that provides weight loss and maintenance programs with follow-up for several decades. However, the increase in the number of patients undergoing bariatric surgery, which facilitates weight loss and improves metabolic function, may provide future data on specific cancer diagnoses decades out from operations without the monetary costs associated with a huge clinical trial. Even with these types of studies, much would still need to be elucidated, including the sustainability of weight loss and the precise mechanisms affected by reducing adipose tissue mass. Given the complex relationship among excess adipose tissue, its distribution, and associated metabolic abnormalities, it will be important to develop adequate preclinical models in which these factors can be systematically addressed and targeted to provide better translational relevance.

Footnotes

Tumor Microenvironment in Breast Cancer Theme Issue

Supported by NIH grants R01CA241156 (E.A.W.) and R01ES030695 (J.J.B.).

Disclosures: None declared.

This article is a part of a review series on the role of the tumor microenvironment in breast cancer pathogenesis.

References

- 1.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.NCD Risk Factor Collaboration (NCD-RisC) Worldwide trends in body-mass index, underweight, overweight, and obesity from 1975 to 2016: a pooled analysis of 2416 population-based measurement studies in 128.9 million children, adolescents, and adults. Lancet. 2017;390:2627–2642. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)32129-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hales C.M., Carroll M.D., Fryar C.D., Ogden C.L. Prevalence of obesity among adults and youth: United States, 2015-2016. NCHS Data Brief. 2017;288:1–8. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ogden C.L., Carroll M.D., Kit B.K., Flegal K.M. Prevalence of childhood and adult obesity in the United States, 2011-2012. JAMA. 2014;311:806–814. doi: 10.1001/jama.2014.732. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lauby-Secretan B., Scoccianti C., Loomis D., Grosse Y., Bianchini F., Straif K., International Agency for Research on Cancer Handbook Working Group Body fatness and cancer--viewpoint of the IARC working group. N Engl J Med. 2016;375:794–798. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1606602. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cao Z., Zheng X., Yang H., Li S., Xu F., Yang X., Wang Y. Association of obesity status and metabolic syndrome with site-specific cancers: a population-based cohort study. Br J Cancer. 2020;123:1336–1344. doi: 10.1038/s41416-020-1012-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Premenopausal Breast Cancer Collaborative G. Schoemaker M.J., Nichols H.B., Wright L.B., Brook M.N., Jones M.E. Association of body mass index and age with subsequent breast cancer risk in premenopausal women. JAMA Oncol. 2018;4:e181771. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.1771. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Waks A.G., Winer E.P. Breast cancer treatment: a review. JAMA. 2019;321:288–300. doi: 10.1001/jama.2018.19323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Blair C.K., Wiggins C.L., Nibbe A.M., Storlie C.B., Prossnitz E.R., Royce M., Lomo L.C., Hill D.A. Obesity and survival among a cohort of breast cancer patients is partially mediated by tumor characteristics. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2019;5:33. doi: 10.1038/s41523-019-0128-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Renehan A.G., Tyson M., Egger M., Heller R.F., Zwahlen M. Body-mass index and incidence of cancer: a systematic review and meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. Lancet. 2008;371:569–578. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(08)60269-X. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kaplan M.A., Pekkolay Z., Kucukoner M., Inal A., Urakci Z., Ertugrul H., Akdogan R., Firat U., Yildiz I., Isikdogan A. Type 2 diabetes mellitus and prognosis in early stage breast cancer women. Med Oncol. 2012;29:1576–1580. doi: 10.1007/s12032-011-0109-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neuhouser M.L., Aragaki A.K., Prentice R.L., Manson J.E., Chlebowski R., Carty C.L., Ochs-Balcom H.M., Thomson C.A., Caan B.J., Tinker L.F., Urrutia R.P., Knudtson J., Anderson G.L. Overweight, obesity, and postmenopausal invasive breast cancer risk: a secondary analysis of the women's health initiative randomized clinical trials. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:611–621. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.1546. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Calle E.E., Rodriguez C., Walker-Thurmond K., Thun M.J. Overweight, obesity, and mortality from cancer in a prospectively studied cohort of U.S. adults. N Engl J Med. 2003;348:1625–1638. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa021423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Folkerd E.J., Dixon J.M., Renshaw L., A'Hern R.P., Dowsett M. Suppression of plasma estrogen levels by letrozole and anastrozole is related to body mass index in patients with breast cancer. J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2977–2980. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.42.0273. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Subbaramaiah K., Morris P.G., Zhou X.K., Morrow M., Du B., Giri D., Kopelovich L., Hudis C.A., Dannenberg A.J. Increased levels of COX-2 and prostaglandin E2 contribute to elevated aromatase expression in inflamed breast tissue of obese women. Cancer Discovery. 2012;2:356–365. doi: 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-11-0241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 16.Brinton L.A., Richesson D.A., Gierach G.L., Lacey J.V., Jr., Park Y., Hollenbeck A.R., Schatzkin A. Prospective evaluation of risk factors for male breast cancer. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2008;100:1477–1481. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn329. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gerard C., Brown K.A. Obesity and breast cancer - role of estrogens and the molecular underpinnings of aromatase regulation in breast adipose tissue. Mol Cell Endocrinol. 2018;466:15–30. doi: 10.1016/j.mce.2017.09.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Sestak I., Distler W., Forbes J.F., Dowsett M., Howell A., Cuzick J. Effect of body mass index on recurrences in tamoxifen and anastrozole treated women: an exploratory analysis from the ATAC trial. J Clin Oncol. 2010;28:3411–3415. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2009.27.2021. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Pfeiler G., Konigsberg R., Fesl C., Mlineritsch B., Stoeger H., Singer C.F., Postlberger S., Steger G.G., Seifert M., Dubsky P., Taucher S., Samonigg H., Bjelic-Radisic V., Greil R., Marth C., Gnant M. Impact of body mass index on the efficacy of endocrine therapy in premenopausal patients with breast cancer: an analysis of the prospective ABCSG-12 trial. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:2653–2659. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.33.2585. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ligibel J.A., Winer E.P. Aromatase inhibition in obese women: how much is enough? J Clin Oncol. 2012;30:2940–2942. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2012.43.7244. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Buzdar A.U., Jones S.E., Vogel C.L., Wolter J., Plourde P., Webster A. A phase III trial comparing anastrozole (1 and 10 milligrams), a potent and selective aromatase inhibitor, with megestrol acetate in postmenopausal women with advanced breast carcinoma. Cancer. 1997;79:730–739. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Jonat W., Howell A., Blomqvist C., Eiermann W., Winblad G., Tyrrell C., Mauriac L., Roche H., Lundgren S., Hellmund R., Azab M. A randomised trial comparing two doses of the new selective aromatase inhibitor anastrozole (Arimidex) with megestrol acetate in postmenopausal patients with advanced breast cancer. Eur J Cancer. 1996;32A:404–412. doi: 10.1016/0959-8049(95)00014-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Schech A., Yu S., Goloubeva O., McLenithan J., Sabnis G. A nude mouse model of obesity to study the mechanisms of resistance to aromatase inhibitors. Endocr Relat Cancer. 2015;22:645–656. doi: 10.1530/ERC-15-0168. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Subbaramaiah K., Howe L.R., Bhardwaj P., Du B., Gravaghi C., Yantiss R.K., Zhou X.K., Blaho V.A., Hla T., Yang P., Kopelovich L., Hudis C.A., Dannenberg A.J. Obesity is associated with inflammation and elevated aromatase expression in the mouse mammary gland. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2011;4:329–346. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-10-0381. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 25.Wellberg E.A., Kabos P., Gillen A.E., Jacobsen B.M., Brechbuhl H.M., Johnson S.J., Rudolph M.C., Edgerton S.M., Thor A.D., Anderson S.M., Elias A., Zhou X.K., Iyengar N.M., Morrow M., Falcone D.J., El-Hely O., Dannenberg A.J., Sartorius C.A., MacLean P.S. FGFR1 underlies obesity-associated progression of estrogen receptor-positive breast cancer after estrogen deprivation. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e120594. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.120594. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Zhao H., Innes J., Brooks D.C., Reierstad S., Yilmaz M.B., Lin Z., Bulun S.E. A novel promoter controls Cyp19a1 gene expression in mouse adipose tissue. Reprod Biol Endocrinol. 2009;7:37. doi: 10.1186/1477-7827-7-37. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chow J.D., Simpson E.R., Boon W.C. Alternative 5'-untranslated first exons of the mouse Cyp19A1 (aromatase) gene. J Steroid Biochem Mol Biol. 2009;115:115–125. doi: 10.1016/j.jsbmb.2009.03.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Cecchini R.S., Costantino J.P., Cauley J.A., Cronin W.M., Wickerham D.L., Land S.R., Weissfeld J.L., Wolmark N. Body mass index and the risk for developing invasive breast cancer among high-risk women in NSABP P-1 and STAR breast cancer prevention trials. Cancer Prev Res (Phila) 2012;5:583–592. doi: 10.1158/1940-6207.CAPR-11-0482. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Welti L.M., Beavers D.P., Caan B.J., Sangi-Haghpeykar H., Vitolins M.Z., Beavers K.M. Weight fluctuation and cancer risk in postmenopausal women: the women's health initiative. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:779–786. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-16-0611. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park Y.M., White A.J., Nichols H.B., O'Brien K.M., Weinberg C.R., Sandler D.P. The association between metabolic health, obesity phenotype and the risk of breast cancer. Int J Cancer J Int du Cancer. 2017;140:2657–2666. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gunter M.J., Xie X., Xue X., Kabat G.C., Rohan T.E., Wassertheil-Smoller S., Ho G.Y., Wylie-Rosett J., Greco T., Yu H., Beasley J., Strickler H.D. Breast cancer risk in metabolically healthy but overweight postmenopausal women. Cancer Res. 2015;75:270–274. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-14-2317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kabat G.C., Kim M.Y., Lee J.S., Ho G.Y., Going S.B., Beebe-Dimmer J., Manson J.E., Chlebowski R.T., Rohan T.E. Metabolic obesity phenotypes and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. Cancer Epidemiol Biomarkers Prev. 2017;26:1730–1735. doi: 10.1158/1055-9965.EPI-17-0495. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gunter M.J., Hoover D.R., Yu H., Wassertheil-Smoller S., Rohan T.E., Manson J.E., Li J., Ho G.Y., Xue X., Anderson G.L., Kaplan R.C., Harris T.G., Howard B.V., Wylie-Rosett J., Burk R.D., Strickler H.D. Insulin, insulin-like growth factor-I, and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2009;101:48–60. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Bruning P.F., Bonfrer J.M., van Noord P.A., Hart A.A., de Jong-Bakker M., Nooijen W.J. Insulin resistance and breast-cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 1992;52:511–516. doi: 10.1002/ijc.2910520402. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Plymate S.R., Hoop R.C., Jones R.E., Matej L.A. Regulation of sex hormone-binding globulin production by growth factors. Metab Clin Exp. 1990;39:967–970. doi: 10.1016/0026-0495(90)90309-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.van der Burg B., Rutteman G.R., Blankenstein M.A., de Laat S.W., van Zoelen E.J. Mitogenic stimulation of human breast cancer cells in a growth factor-defined medium: synergistic action of insulin and estrogen. J Cell Physiol. 1988;134:101–108. doi: 10.1002/jcp.1041340112. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Beckwith H., Yee D. Insulin-like growth factors, insulin, and growth hormone signaling in breast cancer: implications for targeted therapy. Endocr Pract. 2014;20:1214–1221. doi: 10.4158/EP14208.RA. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Katzenellenbogen B.S., Norman M.J. Multihormonal regulation of the progesterone receptor in MCF-7 human breast cancer cells: interrelationships among insulin/insulin-like growth factor-I, serum, and estrogen. Endocrinology. 1990;126:891–898. doi: 10.1210/endo-126-2-891. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Giles E.D., Wellberg E.A., Astling D.P., Anderson S.M., Thor A.D., Jindal S., Tan A.C., Schedin P.S., Maclean P.S. Obesity and overfeeding affecting both tumor and systemic metabolism activates the progesterone receptor to contribute to postmenopausal breast cancer. Cancer Res. 2012;72:6490–6501. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-1653. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Keum N., Greenwood D.C., Lee D.H., Kim R., Aune D., Ju W., Hu F.B., Giovannucci E.L. Adult weight gain and adiposity-related cancers: a dose-response meta-analysis of prospective observational studies. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2015;107 doi: 10.1093/jnci/dju428. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Iyengar N.M., Zhou X.K., Gucalp A., Morris P.G., Howe L.R., Giri D.D., Morrow M., Wang H., Pollak M., Jones L.W., Hudis C.A., Dannenberg A.J. Systemic correlates of white adipose tissue inflammation in early-stage breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2016;22:2283–2289. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-15-2239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Nguyen M.T., Favelyukis S., Nguyen A.K., Reichart D., Scott P.A., Jenn A., Liu-Bryan R., Glass C.K., Neels J.G., Olefsky J.M. A subpopulation of macrophages infiltrates hypertrophic adipose tissue and is activated by free fatty acids via Toll-like receptors 2 and 4 and JNK-dependent pathways. J Biol Chem. 2007;282:35279–35292. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M706762200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patsouris D., Li P.P., Thapar D., Chapman J., Olefsky J.M., Neels J.G. Ablation of CD11c-positive cells normalizes insulin sensitivity in obese insulin resistant animals. Cell Metab. 2008;8:301–309. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2008.08.015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Arkan M.C., Hevener A.L., Greten F.R., Maeda S., Li Z.W., Long J.M., Wynshaw-Boris A., Poli G., Olefsky J., Karin M. IKK-beta links inflammation to obesity-induced insulin resistance. Nat Med. 2005;11:191–198. doi: 10.1038/nm1185. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Solinas G., Vilcu C., Neels J.G., Bandyopadhyay G.K., Luo J.L., Naugler W., Grivennikov S., Wynshaw-Boris A., Scadeng M., Olefsky J.M., Karin M. JNK1 in hematopoietically derived cells contributes to diet-induced inflammation and insulin resistance without affecting obesity. Cell Metab. 2007;6:386–397. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2007.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Quail D.F., Joyce J.A. Microenvironmental regulation of tumor progression and metastasis. Nat Med. 2013;19:1423–1437. doi: 10.1038/nm.3394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Hotamisligil G.S., Shargill N.S., Spiegelman B.M. Adipose expression of tumor necrosis factor-alpha: direct role in obesity-linked insulin resistance. Science. 1993;259:87–91. doi: 10.1126/science.7678183. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Bluher M. Adipose tissue inflammation: a cause or consequence of obesity-related insulin resistance? Clin Sci (Lond) 2016;130:1603–1614. doi: 10.1042/CS20160005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Lehuede C., Li X., Dauvillier S., Vaysse C., Franchet C., Clement E., Esteve D., Longue M., Chaltiel L., Le Gonidec S., Lazar I., Geneste A., Dumontet C., Valet P., Nieto L., Fallone F., Muller C. Adipocytes promote breast cancer resistance to chemotherapy, a process amplified by obesity: role of the major vault protein (MVP) Breast Cancer Res. 2019;21:7. doi: 10.1186/s13058-018-1088-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Wang T., Fahrmann J.F., Lee H., Li Y.J., Tripathi S.C., Yue C., Zhang C., Lifshitz V., Song J., Yuan Y., Somlo G., Jandial R., Ann D., Hanash S., Jove R., Yu H. JAK/STAT3-regulated fatty acid beta-oxidation is critical for breast cancer stem cell self-renewal and chemoresistance. Cell Metab. 2018;27:136–150.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2017.11.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Delort L., Bougaret L., Cholet J., Vermerie M., Billard H., Decombat C., Bourgne C., Berger M., Dumontet C., Caldefie-Chezet F. Hormonal therapy resistance and breast cancer: involvement of adipocytes and leptin. Nutrients. 2019;11 doi: 10.3390/nu11122839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Bougaret L., Delort L., Billard H., Le Huede C., Boby C., De la Foye A., Rossary A., Mojallal A., Damour O., Auxenfans C., Vasson M.P., Caldefie-Chezet F. Adipocyte/breast cancer cell crosstalk in obesity interferes with the anti-proliferative efficacy of tamoxifen. PLoS One. 2018;13:e0191571. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0191571. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Bochet L., Meulle A., Imbert S., Salles B., Valet P., Muller C. Cancer-associated adipocytes promotes breast tumor radioresistance. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2011;411:102–106. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2011.06.101. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhao C., Wu M., Zeng N., Xiong M., Hu W., Lv W., Yi Y., Zhang Q., Wu Y. Cancer-associated adipocytes: emerging supporters in breast cancer. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2020;39:156. doi: 10.1186/s13046-020-01666-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wu B., Sun X., Gupta H.B., Yuan B., Li J., Ge F., Chiang H.C., Zhang X., Zhang C., Zhang D., Yang J., Hu Y., Curiel T.J., Li R. Adipose PD-L1 modulates PD-1/PD-L1 checkpoint blockade immunotherapy efficacy in breast cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2018;7:e1500107. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2018.1500107. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Cortellini A., Bersanelli M., Buti S., Cannita K., Santini D., Perrone F. A multicenter study of body mass index in cancer patients treated with anti-PD-1/PD-L1 immune checkpoint inhibitors: when overweight becomes favorable. J Immunother Cancer. 2019;7:57. doi: 10.1186/s40425-019-0527-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Vonderheide R.H., Domchek S.M., Clark A.S. Immunotherapy for breast cancer: what are we missing? Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:2640–2646. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-16-2569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Van Pelt R.E., Gavin K.M., Kohrt W.M. Regulation of body composition and bioenergetics by estrogens. Endocrinol Metab Clin North Am. 2015;44:663–676. doi: 10.1016/j.ecl.2015.05.011. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Matthews S.B., Thompson H.J. The obesity-breast cancer conundrum: an analysis of the issues. Int J Mol Sci. 2016;17 doi: 10.3390/ijms17060989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Pierobon M., Frankenfeld C.L. Obesity as a risk factor for triple-negative breast cancers: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2013;137:307–314. doi: 10.1007/s10549-012-2339-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Patel P., Abate N. Body fat distribution and insulin resistance. Nutrients. 2013;5:2019–2027. doi: 10.3390/nu5062019. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Shen W., Wang Z., Punyanita M., Lei J., Sinav A., Kral J.G., Imielinska C., Ross R., Heymsfield S.B. Adipose tissue quantification by imaging methods: a proposed classification. Obes Res. 2003;11:5–16. doi: 10.1038/oby.2003.3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Verboven K., Wouters K., Gaens K., Hansen D., Bijnen M., Wetzels S., Stehouwer C.D., Goossens G.H., Schalkwijk C.G., Blaak E.E., Jocken J.W. Abdominal subcutaneous and visceral adipocyte size, lipolysis and inflammation relate to insulin resistance in male obese humans. Sci Rep. 2018;8:4677. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-22962-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Weisberg S.P., McCann D., Desai M., Rosenbaum M., Leibel R.L., Ferrante A.W., Jr. Obesity is associated with macrophage accumulation in adipose tissue. J Clin Invest. 2003;112:1796–1808. doi: 10.1172/JCI19246. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Cancello R., Tordjman J., Poitou C., Guilhem G., Bouillot J.L., Hugol D., Coussieu C., Basdevant A., Bar Hen A., Bedossa P., Guerre-Millo M., Clement K. Increased infiltration of macrophages in omental adipose tissue is associated with marked hepatic lesions in morbid human obesity. Diabetes. 2006;55:1554–1561. doi: 10.2337/db06-0133. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Mathis D. Immunological goings-on in visceral adipose tissue. Cell Metab. 2013;17:851–859. doi: 10.1016/j.cmet.2013.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Stolarczyk E. Adipose tissue inflammation in obesity: a metabolic or immune response? Curr Opin Pharmacol. 2017;37:35–40. doi: 10.1016/j.coph.2017.08.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Barzilai N., She L., Liu B.Q., Vuguin P., Cohen P., Wang J., Rossetti L. Surgical removal of visceral fat reverses hepatic insulin resistance. Diabetes. 1999;48:94–98. doi: 10.2337/diabetes.48.1.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Kim Y.W., Kim J.Y., Lee S.K. Surgical removal of visceral fat decreases plasma free fatty acid and increases insulin sensitivity on liver and peripheral tissue in monosodium glutamate (MSG)-obese rats. J Korean Med Sci. 1999;14:539–545. doi: 10.3346/jkms.1999.14.5.539. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Pitombo C., Araujo E.P., De Souza C.T., Pareja J.C., Geloneze B., Velloso L.A. Amelioration of diet-induced diabetes mellitus by removal of visceral fat. J Endocrinol. 2006;191:699–706. doi: 10.1677/joe.1.07069. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Shi H., Strader A.D., Woods S.C., Seeley R.J. The effect of fat removal on glucose tolerance is depot specific in male and female mice. Am J Physiol Endocrinol Metab. 2007;293:E1012–E1020. doi: 10.1152/ajpendo.00649.2006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Foster M.T., Shi H., Softic S., Kohli R., Seeley R.J., Woods S.C. Transplantation of non-visceral fat to the visceral cavity improves glucose tolerance in mice: investigation of hepatic lipids and insulin sensitivity. Diabetologia. 2011;54:2890–2899. doi: 10.1007/s00125-011-2259-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Isakson P., Hammarstedt A., Gustafson B., Smith U. Impaired preadipocyte differentiation in human abdominal obesity: role of Wnt, tumor necrosis factor-alpha, and inflammation. Diabetes. 2009;58:1550–1557. doi: 10.2337/db08-1770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Thorne A., Lonnqvist F., Apelman J., Hellers G., Arner P. A pilot study of long-term effects of a novel obesity treatment: omentectomy in connection with adjustable gastric banding. Int J Obes Relat Metab Disord. 2002;26:193–199. doi: 10.1038/sj.ijo.0801871. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Dirat B., Bochet L., Dabek M., Daviaud D., Dauvillier S., Majed B., Wang Y.Y., Meulle A., Salles B., Le Gonidec S., Garrido I., Escourrou G., Valet P., Muller C. Cancer-associated adipocytes exhibit an activated phenotype and contribute to breast cancer invasion. Cancer Res. 2011;71:2455–2465. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-3323. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Duong M.N., Geneste A., Fallone F., Li X., Dumontet C., Muller C. The fat and the bad: mature adipocytes, key actors in tumor progression and resistance. Oncotarget. 2017;8:57622–57641. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.18038. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wang Y.Y., Attane C., Milhas D., Dirat B., Dauvillier S., Guerard A., Gilhodes J., Lazar I., Alet N., Laurent V., Le Gonidec S., Biard D., Herve C., Bost F., Ren G.S., Bono F., Escourrou G., Prentki M., Nieto L., Valet P., Muller C. Mammary adipocytes stimulate breast cancer invasion through metabolic remodeling of tumor cells. JCI Insight. 2017;2:e87489. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.87489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Tan J., Buache E., Chenard M.P., Dali-Youcef N., Rio M.C. Adipocyte is a non-trivial, dynamic partner of breast cancer cells. Int J Dev Biol. 2011;55:851–859. doi: 10.1387/ijdb.113365jt. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Wu Q., Li B., Li Z., Li J., Sun S., Sun S. Cancer-associated adipocytes: key players in breast cancer progression. J Hematol Oncol. 2019;12:95. doi: 10.1186/s13045-019-0778-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Rio M.C., Dali-Youcef N., Tomasetto C. Local adipocyte cancer cell paracrine loop: can "sick fat" be more detrimental? Horm Mol Biol Clin Investig. 2015;21:43–56. doi: 10.1515/hmbci-2014-0044. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Incio J., Ligibel J.A., McManus D.T., Suboj P., Jung K., Kawaguchi K., Pinter M., Babykutty S., Chin S.M., Vardam T.D., Huang Y., Rahbari N.N., Roberge S., Wang D., Gomes-Santos I.L., Puchner S.B., Schlett C.L., Hoffmman U., Ancukiewicz M., Tolaney S.M., Krop I.E., Duda D.G., Boucher Y., Fukumura D., Jain R.K. Obesity promotes resistance to anti-VEGF therapy in breast cancer by up-regulating IL-6 and potentially FGF-2. Sci Transl Med. 2018;10 doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aag0945. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Quail D.F., Dannenberg A.J. The obese adipose tissue microenvironment in cancer development and progression. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2019;15:139–154. doi: 10.1038/s41574-018-0126-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Brown K.A., Iyengar N.M., Zhou X.K., Gucalp A., Subbaramaiah K., Wang H., Giri D.D., Morrow M., Falcone D.J., Wendel N.K., Winston L.A., Pollak M., Dierickx A., Hudis C.A., Dannenberg A.J. Menopause is a determinant of breast aromatase expression and its associations with BMI, inflammation, and systemic markers. J Clin Endocrinol Metab. 2017;102:1692–1701. doi: 10.1210/jc.2016-3606. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Iyengar N.M., Arthur R., Manson J.E., Chlebowski R.T., Kroenke C.H., Peterson L., Cheng T.D., Feliciano E.C., Lane D., Luo J., Nassir R., Pan K., Wassertheil-Smoller S., Kamensky V., Rohan T.E., Dannenberg A.J. Association of body fat and risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal women with normal body mass index: a secondary analysis of a randomized clinical trial and observational study. JAMA Oncol. 2019;5:155–163. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2018.5327. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Chakraborty D., Benham V., Bullard B., Kearney T., Hsia H.C., Gibbon D., Demireva E.Y., Lunt S.Y., Bernard J.J. Fibroblast growth factor receptor is a mechanistic link between visceral adiposity and cancer. Oncogene. 2017;36:6668–6679. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.278. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Lu Y.P., Lou Y.R., Bernard J.J., Peng Q.Y., Li T., Lin Y., Shih W.J., Nghiem P., Shapses S., Wagner G.C., Conney A.H. Surgical removal of the parametrial fat pads stimulates apoptosis and inhibits UVB-induced carcinogenesis in mice fed a high-fat diet. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2012;109:9065–9070. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1205810109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.DiGiacomo J.W., Godet I., Trautmann-Rodriguez M., Gilkes D.M. Extracellular matrix-bound FGF2 mediates estrogen receptor signaling and therapeutic response in breast cancer. Mol Cancer Res. 2020;23:6138–6150. doi: 10.1158/1541-7786.MCR-20-0554. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Benham V., Chakraborty D., Bullard B., Bernard J.J. A role for FGF2 in visceral adiposity-associated mammary epithelial transformation. Adipocyte. 2018;7:113–120. doi: 10.1080/21623945.2018.1445889. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Van Huffel S.C., Tham J.M., Zhang X., Lim K., Yang C., Tan Y., Ong F., Lee I., Hong W. Systematic analysis of secreted proteins reveals synergism between IL6 and other proteins in soft agar growth of MCF10A cells. Cell Biosci. 2011;1:13. doi: 10.1186/2045-3701-1-13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Al-Khalaf H.H., Al-Harbi B., Al-Sayed A., Arafah M., Tulbah A., Jarman A., Al-Mohanna F., Aboussekhra A. Interleukin-8 activates breast cancer-associated adipocytes and promotes their angiogenesis- and tumorigenesis-promoting effects. Mol Cell Biol. 2019;39:e00332-18. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00332-18. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Picon-Ruiz M., Pan C., Drews-Elger K., Jang K., Besser A.H., Zhao D., Morata-Tarifa C., Kim M., Ince T.A., Azzam D.J., Wander S.A., Wang B., Ergonul B., Datar R.H., Cote R.J., Howard G.A., El-Ashry D., Torne-Poyatos P., Marchal J.A., Slingerland J.M. Interactions between adipocytes and breast cancer cells stimulate cytokine production and drive Src/Sox2/miR-302b-mediated malignant progression. Cancer Research. 2016;76:491–504. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-0927. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Gui Y., Pan Q., Chen X., Xu S., Luo X., Chen L. The association between obesity related adipokines and risk of breast cancer: a meta-analysis. Oncotarget. 2017;8:75389–75399. doi: 10.18632/oncotarget.17853. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Nickel A., Blucher C., Kadri O.A., Schwagarus N., Muller S., Schaab M., Thiery J., Burkhardt R., Stadler S.C. Adipocytes induce distinct gene expression profiles in mammary tumor cells and enhance inflammatory signaling in invasive breast cancer cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8:9482. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-27210-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Wang S., Cao S., Arhatte M., Li D., Shi Y., Kurz S., Hu J., Wang L., Shao J., Atzberger A., Wang Z., Wang C., Zang W., Fleming I., Wettschureck N., Honore E., Offermanns S. Adipocyte Piezo1 mediates obesogenic adipogenesis through the FGF1/FGFR1 signaling pathway in mice. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2303. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16026-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Formisano L., Stauffer K.M., Young C.D., Bhola N.E., Guerrero-Zotano A.L., Jansen V.M., Estrada M.M., Hutchinson K.E., Giltnane J.M., Schwarz L.J., Lu Y., Balko J.M., Deas O., Cairo S., Judde J.G., Mayer I.A., Sanders M., Dugger T.C., Bianco R., Stricker T., Arteaga C.L. Association of FGFR1 with ERalpha maintains ligand-independent ER transcription and mediates resistance to estrogen deprivation in ER+ breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2017;23:6138–6150. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-17-1232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Mao P., Cohen O., Kowalski K.J., Kusiel J.G., Buendia-Buendia J.E., Cuoco M.S., Exman P., Wander S.A., Waks A.G., Nayar U., Chung J., Freeman S., Rozenblatt-Rosen O., Miller V.A., Piccioni F., Root D.E., Regev A., Winer E.P., Lin N.U., Wagle N. Acquired FGFR and FGF alterations confer resistance to estrogen receptor (ER) targeted therapy in ER(+) metastatic breast cancer. Clin Cancer Res. 2020;26:5974–5989. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3958. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Balaban S., Shearer R.F., Lee L.S., van Geldermalsen M., Schreuder M., Shtein H.C., Cairns R., Thomas K.C., Fazakerley D.J., Grewal T., Holst J., Saunders D.N., Hoy A.J. Adipocyte lipolysis links obesity to breast cancer growth: adipocyte-derived fatty acids drive breast cancer cell proliferation and migration. Cancer Metab. 2017;5:1. doi: 10.1186/s40170-016-0163-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Wu Q., Li J., Li Z., Sun S., Zhu S., Wang L., Wu J., Yuan J., Zhang Y., Sun S., Wang C. Exosomes from the tumour-adipocyte interplay stimulate beige/brown differentiation and reprogram metabolism in stromal adipocytes to promote tumour progression. J Exp Clin Cancer Res. 2019;38:223. doi: 10.1186/s13046-019-1210-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar] [Retracted]

- 99.Park J., Morley T.S., Kim M., Clegg D.J., Scherer P.E. Obesity and cancer--mechanisms underlying tumour progression and recurrence. Nat Rev Endocrinol. 2014;10:455–465. doi: 10.1038/nrendo.2014.94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Frigolet M.E., Gutierrez-Aguilar R. The role of the novel lipokine palmitoleic acid in health and disease. Adv Nutr. 2017;8:173S–181S. doi: 10.3945/an.115.011130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Chajes V., Thiebaut A.C., Rotival M., Gauthier E., Maillard V., Boutron-Ruault M.C., Joulin V., Lenoir G.M., Clavel-Chapelon F. Association between serum trans-monounsaturated fatty acids and breast cancer risk in the E3N-EPIC Study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;167:1312–1320. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwn069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mamalakis G., Kafatos A., Manios Y., Kalogeropoulos N., Andrikopoulos N. Abdominal vs buttock adipose fat: relationships with children's serum lipid levels. Eur J Clin Nutr. 2002;56:1081–1086. doi: 10.1038/sj.ejcn.1601438. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Kitahara C.M., Berrington de Gonzalez A., Freedman N.D., Huxley R., Mok Y., Jee S.H., Samet J.M. Total cholesterol and cancer risk in a large prospective study in Korea. J Clin Oncol. 2011;29:1592–1598. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2010.31.5200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Ha M., Sung J., Song Y.M. Serum total cholesterol and the risk of breast cancer in postmenopausal Korean women. Cancer Causes Control. 2009;20:1055–1060. doi: 10.1007/s10552-009-9301-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Wu Q., Ishikawa T., Sirianni R., Tang H., McDonald J.G., Yuhanna I.S., Thompson B., Girard L., Mineo C., Brekken R.A., Umetani M., Euhus D.M., Xie Y., Shaul P.W. 27-Hydroxycholesterol promotes cell-autonomous, ER-positive breast cancer growth. Cell Rep. 2013;5:637–645. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.10.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.DuSell C.D., Umetani M., Shaul P.W., Mangelsdorf D.J., McDonnell D.P. 27-hydroxycholesterol is an endogenous selective estrogen receptor modulator. Mol Endocrinol. 2008;22:65–77. doi: 10.1210/me.2007-0383. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Voisin M., de Medina P., Mallinger A., Dalenc F., Huc-Claustre E., Leignadier J., Serhan N., Soules R., Segala G., Mougel A., Noguer E., Mhamdi L., Bacquie E., Iuliano L., Zerbinati C., Lacroix-Triki M., Chaltiel L., Filleron T., Cavailles V., Al Saati T., Rochaix P., Duprez-Paumier R., Franchet C., Ligat L., Lopez F., Record M., Poirot M., Silvente-Poirot S. Identification of a tumor-promoter cholesterol metabolite in human breast cancers acting through the glucocorticoid receptor. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2017;114:E9346–E9355. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1707965114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 108.Desai P., Lehman A., Chlebowski R.T., Kwan M.L., Arun M., Manson J.E., Lavasani S., Wasswertheil-Smoller S., Sarto G.E., LeBoff M., Cauley J., Cote M., Beebe-Dimmer J., Jay A., Simon M.S. Statins and breast cancer stage and mortality in the Women's Health Initiative. Cancer Causes Control. 2015;26:529–539. doi: 10.1007/s10552-015-0530-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Campbell M.J., Esserman L.J., Zhou Y., Shoemaker M., Lobo M., Borman E., Baehner F., Kumar A.S., Adduci K., Marx C., Petricoin E.F., Liotta L.A., Winters M., Benz S., Benz C.C. Breast cancer growth prevention by statins. Cancer Res. 2006;66:8707–8714. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-05-4061. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Sakellakis M., Akinosoglou K., Kostaki A., Spyropoulou D., Koutras A. Statins and risk of breast cancer recurrence. Breast Cancer (Dove Med Press) 2016;8:199–205. doi: 10.2147/BCTT.S116694. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Benham V., Bullard B., Dexheimer T.S., Bernard M.P., Neubig R.R., Liby K.T., Bernard J.J. Identifying chemopreventive agents for obesity-associated cancers using an efficient, 3D high-throughput transformation assay. Sci Rep. 2019;9:10278. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-46531-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 112.Lazar I., Clement E., Dauvillier S., Milhas D., Ducoux-Petit M., LeGonidec S., Moro C., Soldan V., Dalle S., Balor S., Golzio M., Burlet-Schiltz O., Valet P., Muller C., Nieto L. Adipocyte exosomes promote melanoma aggressiveness through fatty acid oxidation: a novel mechanism linking obesity and cancer. Cancer Res. 2016;76:4051–4057. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-0651. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 113.Gernapudi R., Yao Y., Zhang Y., Wolfson B., Roy S., Duru N., Eades G., Yang P., Zhou Q. Targeting exosomes from preadipocytes inhibits preadipocyte to cancer stem cell signaling in early-stage breast cancer. Breast Cancer Res Treat. 2015;150:685–695. doi: 10.1007/s10549-015-3326-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 114.Wang S., Su X., Xu M., Xiao X., Li X., Li H., Keating A., Zhao R.C. Exosomes secreted by mesenchymal stromal/stem cell-derived adipocytes promote breast cancer cell growth via activation of Hippo signaling pathway. Stem Cell Res Ther. 2019;10:117. doi: 10.1186/s13287-019-1220-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 115.Sadegh-Nejadi S., Afrisham R., Emamgholipour S., Izadi P., Eivazi N., Tahbazlahafi B., Paknejad M. Influence of plasma circulating exosomes obtained from obese women on tumorigenesis and tamoxifen resistance in MCF-7 cells. IUBMB Life. 2020;72:1930–1940. doi: 10.1002/iub.2305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 116.Lin R., Wang S., Zhao R.C. Exosomes from human adipose-derived mesenchymal stem cells promote migration through Wnt signaling pathway in a breast cancer cell model. Mol Cell Biochem. 2013;383:13–20. doi: 10.1007/s11010-013-1746-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 117.Ferrante S.C., Nadler E.P., Pillai D.K., Hubal M.J., Wang Z., Wang J.M., Gordish-Dressman H., Koeck E., Sevilla S., Wiles A.A., Freishtat R.J. Adipocyte-derived exosomal miRNAs: a novel mechanism for obesity-related disease. Pediatr Res. 2015;77:447–454. doi: 10.1038/pr.2014.202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 118.Valadi H., Ekstrom K., Bossios A., Sjostrand M., Lee J.J., Lotvall J.O. Exosome-mediated transfer of mRNAs and microRNAs is a novel mechanism of genetic exchange between cells. Nat Cell Biol. 2007;9:654–659. doi: 10.1038/ncb1596. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 119.Thomou T., Mori M.A., Dreyfuss J.M., Konishi M., Sakaguchi M., Wolfrum C., Rao T.N., Winnay J.N., Garcia-Martin R., Grinspoon S.K., Gorden P., Kahn C.R. Adipose-derived circulating miRNAs regulate gene expression in other tissues. Nature. 2017;542:450–455. doi: 10.1038/nature21365. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 120.Feigelson H.S., Caan B., Weinmann S., Leonard A.C., Powers J.D., Yenumula P.R., Arterburn D.E., Koebnick C., Altaye M., Schauer D.P. Bariatric surgery is associated with reduced risk of breast cancer in both premenopausal and postmenopausal women. Ann Surg. 2020;272:1053–1059. doi: 10.1097/SLA.0000000000003331. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 121.Luo J., Hendryx M., Manson J.E., Figueiredo J.C., LeBlanc E.S., Barrington W., Rohan T.E., Howard B.V., Reding K., Ho G.Y., Garcia D.O., Chlebowski R.T. Intentional weight loss and obesity-related cancer risk. JNCI Cancer Spectr. 2019;3:pkz054. doi: 10.1093/jncics/pkz054. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 122.Goodwin P.J., Segal R.J., Vallis M., Ligibel J.A., Pond G.R., Robidoux A., Findlay B., Gralow J.R., Mukherjee S.D., Levine M., Pritchard K.I. The LISA randomized trial of a weight loss intervention in postmenopausal breast cancer. NPJ Breast Cancer. 2020;6:6. doi: 10.1038/s41523-020-0149-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 123.Blaszczak A.M., Bernier M., Wright V.P., Gebhardt G., Anandani K., Liu J., Jalilvand A., Bergin S., Wysocki V., Somogyi A., Bradley D., Hsueh W.A. Obesogenic memory maintains adipose tissue inflammation and insulin resistance. Immunometabolism. 2020;2:e200023. doi: 10.20900/immunometab20200023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]