Abstract

Background

Due to its ability to perform fast and high-density fermentation, Pichia pastoris is not only used as an excellent host for heterologous protein expression but also exhibits good potential for efficient biosynthesis of small-molecule compounds. However, basic research on P. pastoris lags far behind Saccharomyces cerevisiae, resulting in a lack of available biological elements. Especially, fewer strong endogenous promoter elements available for foreign protein expression or construction of biosynthetic pathways were carefully evaluated in P. pastoris. Thus, it will be necessary to identify more available endogenous promoters from P. pastoris.

Results

Based on RNA-seq and LacZ reporter system, eight strong endogenous promoters contributing to higher transcriptional expression levels and β-galactosidase activities in three frequently-used media were screened out. Among them, the transcriptional expression level contributed by P0019, P0107, P0230, P0392, or P0785 was basically unchanged during the logarithmic phase and stationary phase of growth. And the transcriptional level contributed by P0208 or P0627 exhibited a growth-dependent characteristic (a lower expression level during the logarithmic phase and a higher expression level during the stationary phase). After 60 h growth, the β-galactosidase activity contributed by P0208, P0627, P0019, P0407, P0392, P0230, P0785, or P0107 was relatively lower than PGAP but higher than PACT1. To evaluate the availability of these promoters, several of them were randomly applied to a heterogenous β-carotene biosynthetic pathway in P. pastoris, and the highest yield of β-carotene from these mutants was up to 1.07 mg/g. In addition, simultaneously using the same promoter multiple times could result in a notable competitive effect, which might significantly lower the transcriptional expression level of the target gene.

Conclusions

The novel strong endogenous promoter identified in this study adds to the number of promoter elements available in P. pastoris. And the competitive effect observed here suggests that a careful pre-evaluation is needed when simultaneously and multiply using the same promoter in one yeast strain. This work also provides an effective strategy to identify more novel biological elements for engineering applications in P. pastoris.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s12934-021-01648-6.

Keywords: Pichia pastoris, Endogenous promoter, RNA-seq, β-Galactosidase, Biosynthetic pathway

Background

As one of the typical methylotrophic yeasts, Pichia pastoris (also known as Komagataella phaffii) is not only widely used as an excellent host for heterologous protein expression [1] but also exhibits good potential for efficient biosynthesis of economic compounds such as nootkatone [2], carotenoids [3, 4], xanthophylls [5], ricinoleic acid [6], hyaluronic acid [7] and dammarenediol II [8]. Although a lot of work had been carried out in P. pastoris, compared with Saccharomyces cerevisiae, fewer strong endogenous promoter elements available for foreign protein expression or construction of biosynthetic pathways were carefully investigated in P. pastoris [9].

Using methanol as a carbon source is one of the most favorable properties of P. pastoris. Several promoters from the methanol utilization (MUT) pathway were identified as the methanol-dependent strong promoters [10], such as PAOX1 (the promoter of alcohol oxidase 1) [11], PFLD1 (the promoter of formaldehyde dehydrogenase 1) [12], and PDAS (the promoter of dihydroxyacetone synthase) [13]. On the contrary, PPEX8 (the promoter of peroxisomal matrix protein) [14] or PAOX2 (the promoter of alcohol oxidase 2) [15] was classified as a weak promoter. Considering that these promoters are tightly regulated by methanol, making them useful for the efficient production of foreign proteins when using methanol as a carbon source and inducer [16].

PGAP is the most frequently used constitutive promoter that drives the expression of glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase at a high level in the medium with glucose or glycerol but at a moderate level in the medium with methanol as a carbon source. Although in many cases, PAOX1 works more efficiently than PGAP for heterologous protein production [17, 18]. Some cases also gave the opposite results. Waterham HR et al. proved the expression level of β-lactamase contributed by PGAP in the medium containing glucose was even higher than PAOX1 in the medium containing methanol [19]. Similar result was obtained with the PGAP regulated mammalian peptide transporters rPEPT2 by Doring F et al. [20]. A promoter library of mutated PGAP was generated, and it spanned an activity range between 0.6% and 19.6-fold of the wild-type PGAP activity [21]. As another well-known constitutive and strong promoter, the transcriptional activity of PTEF1, which controls the expression of translation elongation factor 1 alpha [22], was also found to be similar to or higher than that of PGAP in batch cultures or fed-batch cultures (glucose or glycerol was used as carbon source). PGCW14 is a strong constitutive promoter discovered recently [23]. It exhibited stronger promoter activity than PTEF1 or PGAP under different carbon sources (glucose, glycerol, or methanol) when an enhanced green fluorescent protein (EGFP) was used as the reporter. Moreover, some other constitutive promoters, PENO1, PGPM1, PHSP82, PKAR2, PPGK1, PSSA4, and PTPI1 [24], were also reported with little attention paid. The expression levels of EGFP contributed by these promoters were showed to be 10–80% of that of PGAP.

Although most studies have focused on strong promoters, it is worth noting that strong promoters are not suitable in some applications. For example, promoters with moderate expression levels are sometimes more desirable for transporter or chaperone expression. Thus, the studies on various promoters with different transcriptional activities should also be emphasized. In this study, based on the RNA-seq data and LacZ reporter system, eight novel endogenous promoters that exhibited strong transcriptional activities in three frequently-used media were screened out. A heterogenous β-carotene biosynthetic pathway was chosen to further evaluate the availability of these promoters. It was also found that simultaneously using the same promoter multiple times could result in a notable competitive effect, which might significantly lower the transcriptional expression level of the target gene.

Results

Screening the potential strong promoters independent of carbon sources based on RNA-seq

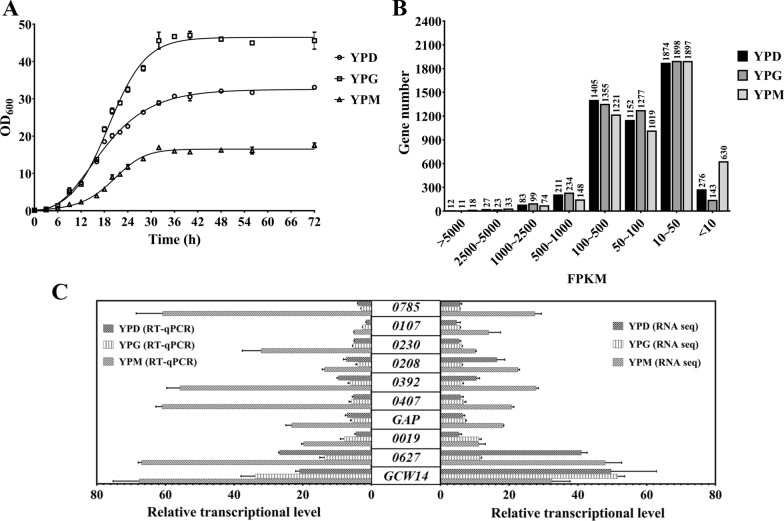

In order to screen out strong promoter candidates from P. pastoris, the assessment of cell growth status was firstly carried out. As shown in Fig. 1A, the yeast cells gradually entered the stationary phase after 36 h growth in YPD, YPG, or YPM broth. Considering that the accumulation of protein expression or small-molecule compound has occurred chiefly during the stationary phase of yeast growth, total RNA isolation and subsequent RNA-seq were performed after 36 h growth.

Fig. 1.

Screening of the strong endogenous promoters based on RNA-seq. A The growth curves of P. pastoris GS115 WT strain in YPD, YPG, or YPM broth for 72 h with an initial OD600 of 0.15. B The distribution of FPKM values of all expressed genes in three broths. C The RNA-seq and RT-qPCR data of candidate genes at 36 h. Error bars indicate the SD for samples tested in triplicate

As shown in Fig. 1B, the distribution of FPKM (referred to fragments per kilobase of transcript per million base pairs sequenced) values of genes was similar when the GS115 WT strain was cultured in three broths, and the FPKM values of most genes fall in the range of 10–50. The FPKM value of ACT1 (PAS_chr3_1169), which is usually used as an endogenous reference gene (housekeeping gene) in yeast [25, 26], was 624 in YPD, 858 in YPG, and 315 in YPM, respectively. It ranked 245th out of 4764 (YPD), 185th out of 4897 (YPG), and 473th out of 4410 (YPM) expressed genes (FPKM < 10 was defined as not expressed in the corresponding medium), indicating that PACT1 could be considered as a strong promoter. To explore the potential strong promoters in all the above media, the genes with FPKM values five times higher than that of ACT1 were selected as the candidate genes. Finally, the promoters of PAS_chr1-4_0586 (GCW14), PAS_chr4_0627, PAS_chr2-2_0019, PAS_chr2-1_0437 (GAP), PAS_chr1-1_0407, PAS_chr2-2_0392, PAS_chr3_0230, PAS_chr2-2_0208, PAS_chr4_0785, and PAS_chr1-1_0107 were screened out (Additional file 1). For the subsequent description’s convenience, the above genes were represented by GCW14, 0627, 0019, GAP, 0407, 0392, 0230, 0208, 0785, and 0107, respectively. In addition, the expression levels of these candidate genes were also confirmed by real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR). As shown in Fig. 1C, all the RT-qPCR results were consistent with the RNA-seq data, suggesting these promoters could be used for further evaluation.

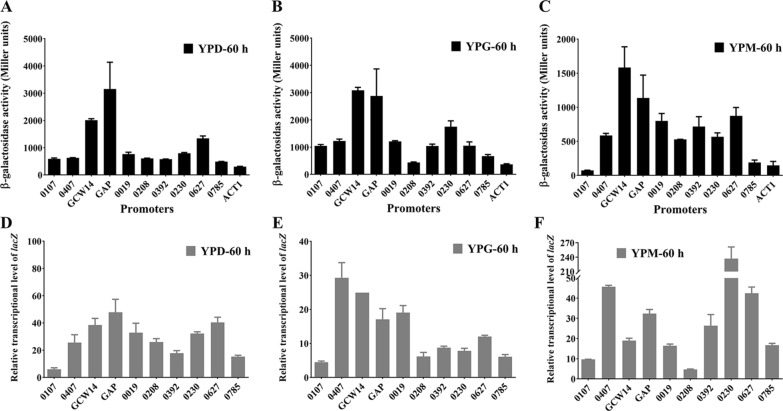

Comparing the transcriptional activities of promoter candidates

In order to compare the transcriptional activities of above-selected promoters, the β-galactosidase activities of transformants harboring vector pZeocin/PXXX-lacZ-TADH1 (PXXX indicates the name of candidate promoter) were measured after 60 h growth. The transcriptional levels of lacZ in all transformants were also tested by RT-qPCR. All experimental data was obtained from three independently screened colonies. As shown in Fig. 2, the β-galactosidase activity contributed by each selected promoter was higher than that by PACT1 when the transformant was cultured in three mentioned broths, except P0107 which exhibited a lower β-galactosidase activity compared to PACT1 in YPM broth. In YPD or YPG broth, the activity of PGAP or PGCW14 was significantly higher than those of the rest promoters. In YPM broth, PGCW14 contributed the highest β-galactosidase activity among the all-selected promoters, and PGAP, P0208, P0019, P0392, P0230, or P0627 contributed a similar β-galactosidase activity. In summary, among the ten selected promoters, the previously reported PGAP and PGCW14 showed strong transcriptional activities. The transcriptional activity of P0019, P0107, P0208, P0230, P0392, P0407, P0627, or P0785 was between that of strong promoters PGAP and PACT1. It indicates that these promoter candidates could be recognized as strong endogenous promoters in P. pastoris.

Fig. 2.

Comparison of the selected promoter activities. A–C The β-galactosidase activity of transformant harboring vector pZeocin/PXXX-lacZ-TADH1 (PXXX indicates the name of candidate promoter) after 60 h growth. D–F The relative transcriptional levels of lacZ in different transformants. The ACT1 gene was used as the reference gene. Error bars indicate the SD for samples tested in triplicate

Although the transcriptional activities of most selected promoters corresponded with the β-galactosidase activities at 60 h, there were still few exceptions, such as P0407 and P0230. For example, the transcriptional level of P0407-lacZ was much higher than that of PGAP-lacZ when the relative transformants were cultured in YPG or YPM broth. However, the β-galactosidase activities controlled by P0407 were less than half of that by PGAP. So was P0230-lacZ. We evaluated the copy number of lacZ controlled by each promoter, the results proved all clones harboring only one lacZ, eliminating the influence of transcriptional level by copy number (data not shown). It indicated that the transcriptional and protein level were not coordinated in some genes. The reason was not clear.

P0208 and P0627 are novel growth-dependent promoters

To evaluate whether the above promoters are constitutive, the β-galactosidase activities of different transformants at 16 h (exponential phase) and 60 h (stationary phase) were measured. In view of PGAP being identified as a recognized constitutive promoter, it was chosen as a control in this study. As shown in Table 1, most promoter candidates, except P0407, P0627, and P0208, could be defined as constitutive promoters due to their relatively stable β-galactosidase activities at 16 and 60 h. The relative β-galactosidase activity driven by P0208, P0407, or P0627 at 16 h was at least 16.5, 2.5 or 7.5 times lower than that at 60 h in three media, reminding us that these promoters might be associated with cell growth.

Table 1.

The relative β-galactosidase activities driven by the selected promoters compared with PGAP

| Promoters | YPD 16 h (%) |

YPD 60 h (%) |

YPG 16 h (%) |

YPG 60 h (%) |

YPM 16 h (%) |

YPM 60 h (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PGAP | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 | 100.00 |

| PACT1 | 17.48 | 11.25 | 18.78 | 15.77 | 30.43 | 15.48 |

| PGCW14 | 88.74 | 74.51 | 131.99 | 132.30 | 162.67 | 165.46 |

| P0019 | 27.51 | 28.25 | 36.94 | 51.98 | 88.92 | 83.48 |

| P0107 | 30.57 | 21.95 | 32.84 | 44.90 | 6.76 | 7.59 |

| P0230 | 30.15 | 29.49 | 42.96 | 75.11 | 54.56 | 59.04 |

| P0392 | 13.39 | 21.47 | 23.55 | 44.67 | 59.76 | 74.83 |

| P0785 | 19.09 | 18.23 | 19.52 | 28.66 | 34.18 | 19.71 |

| P0208 | 0.53 | 22.52 | 1.14 | 18.76 | 0.60 | 55.25 |

| P0407 | 7.92 | 23.23 | 19.13 | 52.61 | 8.26 | 61.18 |

| P0627 | 6.29 | 49.65 | 5.99 | 45.05 | 7.87 | 91.24 |

To test this possibility, the transcriptional levels of 0407, 0208, and 0627 genes in the GS115 WT strain were detected at the different growth stages. As shown in Additional file 2, the transcriptional levels of 0407, 0627 and 0208 genes increased along with the growth time of GS115 WT strain in YPD and YPG media, indicating P0407, P0208 and P0627 could be considered as growth-dependent promoters. In YPM broth, they behaved not growth-dependent at 60 h. We suspect that it may be related to the depletion of carbon source (methanol). In our study, YPD (2%), YPG (2%) or YPM (1%) has 32.58, 33.36 and 12.26 mmol carbon atoms, respectively. At 60 h, the methanol had been depleted which may affect the cell metabolism, so the relative transcriptional level of 0627, 0407 and 0208 at 60 h was lower than that at 36 h, showing non-growth-dependent characteristic. From 16 to 36 h, the relative transcriptional level was increased. Throughout the performance of 0208 and 0627 in three media for three time points, it demonstrates that they are growth-dependent. In addition, the transcriptional level of 0407 was higher than that of ACT1 at 16 h in YPD, YPG and YPM (Additional file 2), indicating P0407 was not a strictly growth-dependent promoter.

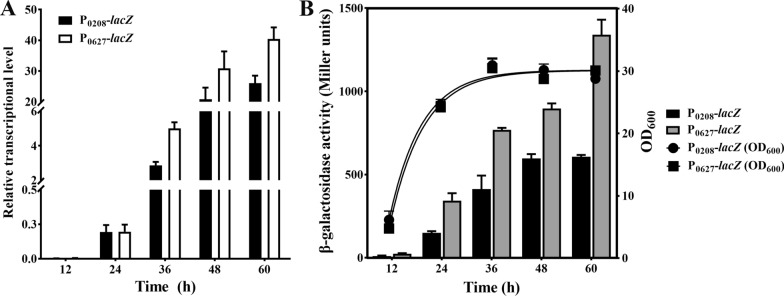

To further investigate the transcriptional properties of P0208 and P0627, the GS115/P0208-lacZ-TADH1 and GS115/P0627-lacZ-TADH1 strains were cultured in YPD broth and sampled every 12 h from 12 h to 60 h. It was found that the relative transcriptional level of P0208 was increased from 0.002 to 16 h to 26 at 60 h, while that of P0627 was increased from 0.005 to 16 h to 40 at 60 h (Fig. 3A). Although the growth status of GS115/P0208-lacZ-TADH1 or GS115/P0627-lacZ-TADH1 strain was similar, the β-galactosidase activity of GS115/P0208-lacZ-TADH1 strain was lower than that of GS115/P0627-lacZ-TADH1 strain at each sampling point (Fig. 3B), suggesting that P0627 has good potential to be used in expressing the toxic proteins independent of methanol induction.

Fig. 3.

The properties of P0208 and P0627. A The relative transcriptional level of P0208-lacZ or P0627-lacZ after 12–60 h growth in YPD broth. The ACT1 gene was used as the reference gene. B The growth curve and β-galactosidase activity of GS115/P0208-lacZ-TADH1 or GS115/P0627-lacZ-TADH1 strain cultured in YPD broth. Error bars indicate the SD for samples tested in triplicate

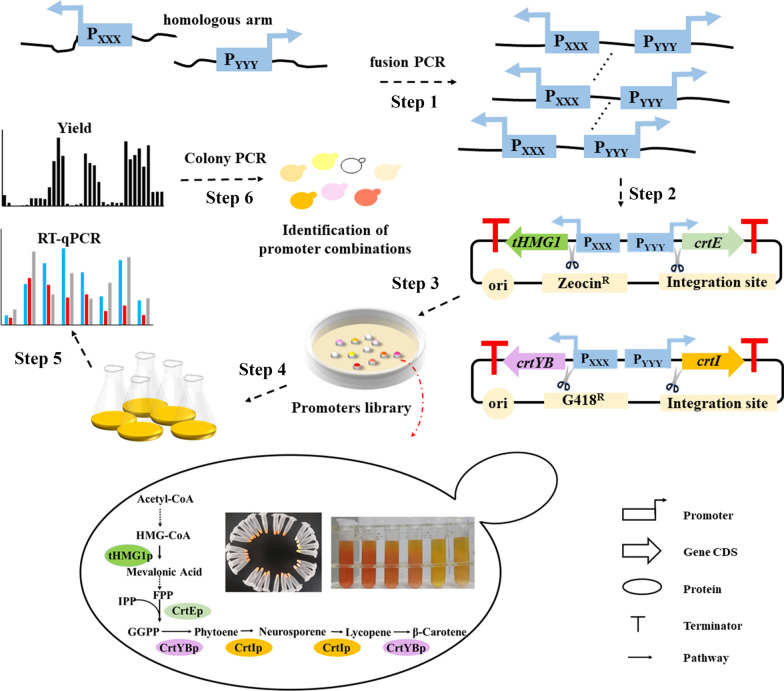

Evaluation of the promoter candidates through the heterogenous β-carotene biosynthetic pathway

According to the previous report, the optimized β-carotene biosynthetic pathway always includes four genes, crtE/tHMG1/crtYB/crtI [27]. In this study, six promoter candidates (PGAP, PGCW14, P0208, P0019, P0230, and P0107) with different transcriptional activities were randomly selected and applied to the β-carotene biosynthetic pathway to further evaluate the availability of promoters. As shown in Fig. 4, a promoter library was first constructed by random linkage of two reverse-aligned promoters (Step 1). Then two vectors (pZeocin/PXXX-crtE-PYYY-tHMG1 and pG418/PXXX-crtYB-PYYY-crtI, PXXX and PYYY indicate the name of candidate promoters) containing the above four genes were constructed (Step 2) and transformed into the GS115 WT strain in turn (Step 3). The promoter activities were qualitatively observed by the color of the transformants on plates (Step 4) and then quantitively determined by liquid fermentation (Step 5).

Fig. 4.

Construction of the β-carotene engineering strain

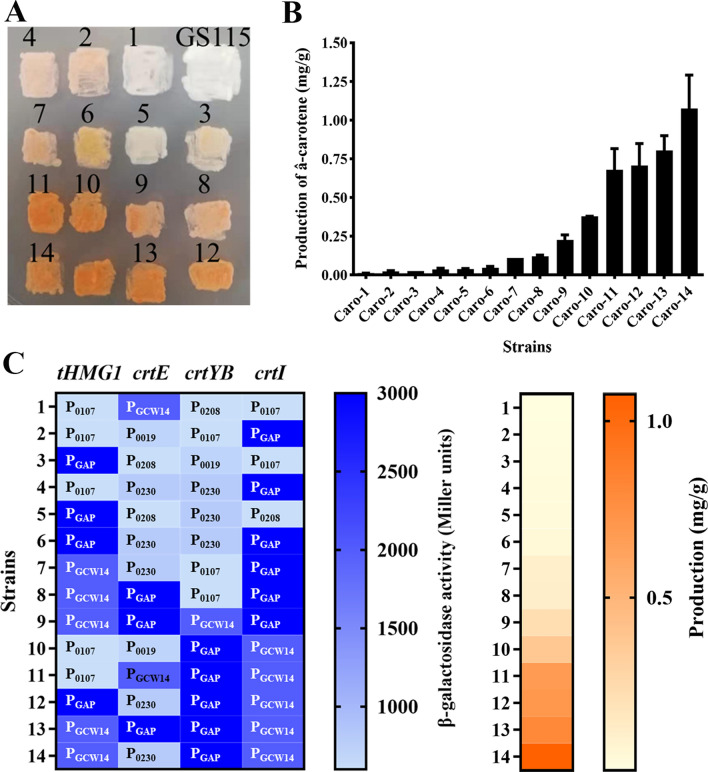

Finally, fourteen transformants with significant color differences were screened out for further liquid fermentation (Fig. 5A). The result indicates that the darker the color of transformant, the higher the yield of β-carotene (Fig. 5B). And the yield of β-carotene from these yeast mutants was from 0.0123 mg/g DCW (Caro-1 strain) up to 1.07 mg/g DCW (Caro-14 strain).

Fig. 5.

Evaluation of the promoter candidates through the β-carotene biosynthetic pathway. A The fourteen engineering strains with significant color differences grown on the YPD agar plate. B The production of β-carotene of the selected engineering strains. Error bars indicate the SD for samples tested in triplicate. C Heat map of the transcriptional levels (blue) and the β-carotene productions (orange)

The promoters of four genes (crtE, tHMG1, crtYB, and crtI) in each strain were verified by PCR and the primers were shown in Additional file 3. The relationship between the transcriptional activity of each gene and the β-carotene production of the engineering strain was then analyzed. As shown in Fig. 5C, when both crtYB and crtI had a stronger promoter (similar to PGAP), the β-carotene production of engineered strain was generally higher, and when crtYB had a relatively weaker promoter compared to PGAP, the β-carotene production of engineered strain was decreased. This result was consistent with the previous report that CrtYBp was the rate-limiting enzyme in β-carotene production [28]. Compared to the promoter combinations in the β-carotene biosynthetic pathway of Caro-13 and Caro-14 strain, all corresponding genes used the same promoter except crtE. The promoter of crtE was PGAP in the Caro-13 strain and P0230 in the Caro-14 strain. Although the transcriptional activity of P0230 was lower than that of PGAP at 60 h, the β-carotene production of the Caro-14 strain was much higher than that of the Caro-13 strain. This result suggested that not all genes should have stronger transcriptional levels to achieve higher β-carotene production. Balancing the expression level of each gene in the biosynthetic pathway could be a better choice.

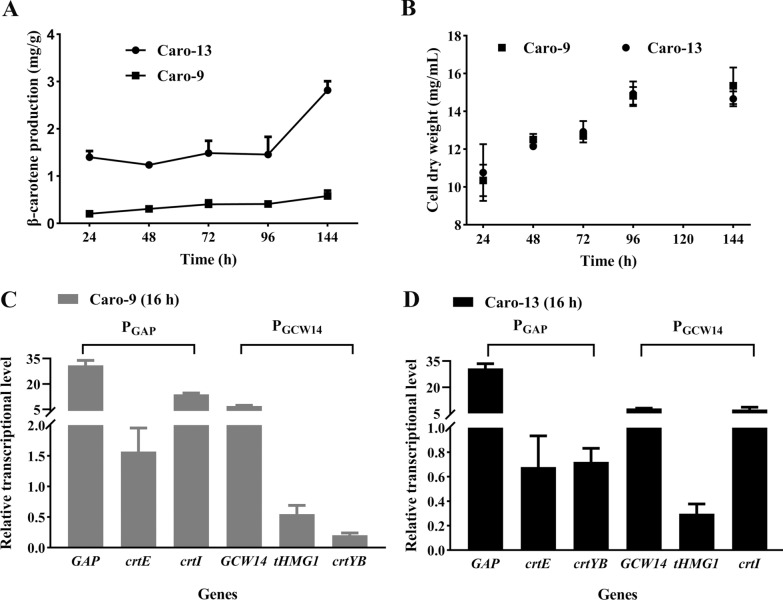

The existence of a significant competitive effect when one promoter was used multiple times in a yeast strain

In the Caro-9 strain, the combination of exogenous genes and promoters was PGCW14-tHMG1/PGAP-crtE/PGCW14-crtYB/PGAP-crtI. In the Caro-13 strain, that was PGCW14-tHMG1/PGAP-crtE/PGCW14-crtI/PGAP-crtYB. Although both PGAP and PGCW14 were strong promoters, and their related β-galactosidase activities were similar (Table 1), the β-carotene production of Caro-9 strain was over 3-fold lower than that of Caro-13 strain (Fig. 6A, B). The RT-qPCR result at 16 h also showed that the transcriptional level of crtYB in the Caro-13 strain was over 3-fold higher than that in the Caro-9 strain (Fig. 6C). To figure out the reason, the transcriptional levels of four genes in the Caro-9 or Caro-13 strain were measured, respectively. Accidentally, the transcriptional levels of two exogenous genes controlled by the same promoter behaved differently. As shown in Fig. 6C, although an endogenous gene (GAP) and two exogenous genes (crtE and crtI) were all driven by PGAP in the Caro-9 strain, the transcriptional levels of both exogenous genes were much lower than that of GAP, presenting a significant “competitive effect”. In addition, the transcriptional levels of crtE and crtI were also different. So were GCW14, crtYB, and tHMG1controlled by PGCW14. A similar phenomenon was also observed in the Caro-13 strain (Fig. 6D). Such a “competitive effect” when the same promoter was used multiple times in one yeast strain resulted in a lower expression level of the related gene than expected. It might be an important factor limiting the β-carotene yields of engineering strains constructed in this study.

Fig. 6.

The competitive effect existing in Caro-13 and Caro-9 strains. A A significant difference in the production of β-carotene in both strains. B The growth curves of both strains. C The relative transcriptional levels of the exogenous genes in the Caro-9 strain after 16 h growth. D The relative transcriptional levels of the exogenous genes in the Caro-13 strain after 16 h growth. The ACT1 gene was used as the reference gene. Error bars indicate the SD for samples tested in triplicate

Discussion

The strong promoter is an indispensable element in the engineering retrofit and application of yeast. Due to the lack of basic research compared with S. cerevisiae, the availability of strong promoter is scarce in P. pastoris, which seriously restricts the subsequent application.

In this study, by analyzing the RNA-seq data of GS115 WT strain in the stationary phase under different media (YPD, YPG, and YPM), ten strong endogenous promoters (PGCW14, P0627, P0019, PGAP, P0407, P0392, P0230, P0208, P0785, and P0107) which were not affected by carbon sources were screened out. Except for PGCW14 and PGAP, eight of them were first reported here. Five (P0019, P0392, P0230, P0785, and P0107) were identified as strong constitutive promoters, and two (P0627 and P0208) as growth-dependent strong promoters. The growth-dependent transcriptional behavior of P0627 or P0208 makes it a good selection for the expression of toxic foreign proteins in P. pastoris. P0407 showed a similar trend as P0627 and P0208 in β-galactosidase activity. However, the transcriptional level of P0407-lacZ was higher than that of ACT1 at 16 h, indicating this promoter was not a strictly growth-dependent promoter. In addition, in our study, the activity of PGCW14 was lower than that of PGAP in YPD broth and similar to that of PGAP in YPG broth when measured with the β-galactosidase activity assay. These results were not consistent with the previous report that PGCW14 activity was much higher than PGAP by EGFP reporter in YPD or YPD broth [23].

However, the results of RT-qPCR and the β-galactosidase activity did not agree in all cases. For example, the transcriptional level of P0407-lacZ was much higher than that of PGAP-lacZ when the relative transformants were cultured in YPG or YPM broth. However, its related β-galactosidase activity was much lower than PGAP. P0107 presented the lowest transcriptional level at 60 h, but its corresponding β-galactosidase activity was not the lowest (Fig. 2). These results agree with the suggestion of previous reports that it was not that the higher of transcriptional level, the higher of protein expression level [29, 30].

In this study, a heterogenous biosynthetic pathway of β-carotene containing four genes was used to further evaluate the properties of six strong endogenous promoters (PGAP, PGCW14, P0208, P0019, P0230, and P0107). The Caro-14 strain contributed the highest yield of β-carotene (1.07 mg/g DCW). It is higher than the yield in S. cerevisiae containing integrated carotenogenic gene cassettes crtYB/I/E/tHMG1 (501 µg/g DCW) [31], suggesting that P. pastoris might have the advantages to be engineered as a carotene producer.

In addition, the competitive effect was first evaluated in this study. It was found that using the same promoter multiple times in one strain could lead to a significant decrease of the expression level of the target gene, reminding a careful evaluation is required before using a promoter in this way.

Some reports considered a 500 bp upstream sequence covering the whole promoter region of most genes in S. cerevisiae [32, 33]. As the most known strong constitutive promoter PGAP in P. pastoris, its’ sequence length is 477 bp. It should be noted that the intergenic region between GAP and its neighbor gene was 1576 bp. On the contrary, the sequence length of another well-known strong inducible promoter, PAOX1, is 939 bp in the commercial vector pPICZαC, mainly covering the intergenic region between AOX1 and its neighbor gene (998 bp). The study of PAOX1 showed that the region − 1055 to − 809 and − 653 to − 514 significantly affects the promoter activity [34]. In our study, the 500 bp upstream sequence of candidate gene was amplified to act as a promoter. However, the lengths of the intergenic region of some genes are more than 500 bp, which might cause incomplete promoter elements like PAOX1, thereby affecting their normal functions. The corresponding intergenic regions of six selected promoters are over 500 bp except P0208, reminding the possibility that several key regulatory elements might not be included in the 500 bp sequence (Additional file 4). The promoter length would be appropriately extended in the follow-up study to explore whether it will significantly impact promoter activity.

Method and materials

Strains, vectors, and media

All strains used in this study are listed in Additional file 5. Escherichia coli TG1 was used to amplify plasmids in LB medium (0.5% yeast extract, 1% tryptone, 1% sodium chloride) containing 100 µg/mL ampicillin, zeocin, or 50 µg/mL kanamycin sulfate, and incubated at 37 °C. The yeast mutants were derived from the P. pastoris GS115 wild-type strain. All yeast strains, unless otherwise specified, were grown in YPD medium (1% yeast extract, 2% peptone, 2% glucose) at 30 °C.

Measurement of the yeast growth curves in different carbon source broths

The GS115 WT strain was pre-cultured in 5 mL YPD broth at 30 °C, 220 rpm for 24 h and followed by inoculating to an initial OD600 of 0.1 in 250 mL shaking flasks containing 50 mL YPD (2% glucose), YPG (2% glycerol), or YPM (1% methanol) for 72 h. The optical absorbance (OD600) of the culture was detected by an Evolution™ 220 spectrophotometer (Thermo Fisher Scientific Inc., USA), and each medium had three replicates.

RNA-seq analysis

Three independent clones of the GS115 WT strain were incubated in 5 mL YPD broth for 24 h. The pre-cultured pellet was washed with presterilized water and transferred into YPD, YPG, or YPM broth for incubating. The yeast cells (total OD600 of 16) were harvested by centrifugation (5000 g for 5 min, 4 °C) at 36 h when they entered the stationary phase. Total RNA was isolated using a Yeast RNA kit (Omega Bio-Tek Inc., USA) through the operation manual. The residuary genomic DNA was eliminated using a DNase I treatment (Takara Bio Inc., Japan). The qualified RNA samples determined with Bioanalyzer 2100 (Agilent Technologies, USA) were used for library construction with the sequencing platform BGISEQ-500 (BGI Shenzhen, China). Compared to the genome, the average comparison rate of the sample is 97.13%, and the average comparison rate of the compared gene set is 82.58%. All the generated raw sequencing reads were filtered to remove reads with adaptors, reads with more than 10% unknown bases, and low-quality reads. Clean reads were then obtained and stored in FASTQ format. The clean reads were mapped to the genome of GS115 by HISAT [35]. The software package RSEM [36] was used to quantify the gene expression level. The ratio of FPKM for candidate genes to that for ACT1 was used as the relative fold change for RNA-seq data treatment.

Real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) analysis

The methods for obtaining pure total RNA were mentioned above. After DNase I treatment, the absence of DNA contamination was confirmed by PCR using a pair of genomic primers, and the genome of the GS115 WT strain was used as a positive control. 800 ng of total RNA was used to reverse transcription to generate cDNA with HiScript II Reverse Transcriptase (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China). RT-qPCR was carried out on a Mastercycler® ep gradient S instrument (Eppendorf, Hamburg, Germany) with 2 × ChemQ SYBR qPCR Mester Mix (Vazyme Biotech Co., Ltd., China). The ACT1 gene was chosen as an internal control to normalize the relative expression levels of target genes. All reactions were performed in three replicates. A ΔΔCt method was used for the relative fold change analysis [37].

Construction of the vectors containing PXXX-lacZ and yeast transformation

The genomic DNA of E. coli BL21 (DE3) was used as a template to amplify the open reading frame (ORF) of lacZ. DNA fragments of the integration site (AOX1 promoter, which helped the plasmid inserted into the chromosome) were amplified from GS115. ADH1 terminator (TADH1) was amplified from the genomic DNA of S. cerevisiae BY4741. The fragment of ori and zeocin-resistant marker came from the commercial plasmid pPICZαC (Invitrogen Corporation, USA). All the fragments were amplified with Hieff Canace™ high-fidelity DNA Polymerase (Yeasen, China) and then be linked by the homologous arm with pEASY®-Basic Seamless Cloning and Assembly Kit (TransGen Biotech Co., Ltd, China) to construct a vector pZeocin/lacZ-TADH1.

The promoter fragments of candidates were amplified from the genomic DNA of P. pastoris GS115 by PCR and then inserted into the HindIII site of pZeocin/lacZ-TADH1 with seamless cloning to yield vector pZeocin/PXXX-lacZ-TADH1 (PXXX indicates the name of candidate promoters).

The linearized vector pZeocin/PXXX-lacZ-TADH1 with PmeI (located in the middle of AOX1 promoter locus) digested were transferred into the GS115 cells by electro-transformation and integrated into the genome by homologous recombination [38]. The strains containing PXXX-lacZ were selected from the agar plates containing zeocin (0.1 mg/mL) and verified by PCR. The template came from colony or genomic DNA. The colony was boiled in water for 5 min before PCR and the genomic DNA was extracted as the previous report [39].

β-Galactosidase activity assay

The β-galactosidase activity was assayed according to the previous report with slight modification [40]. Briefly, the yeast cells (total OD600 of 3) were collected. The supernatant was discarded by centrifuge, and the pellet was resuspended in 1 mL Z buffer (60 mM Na2HPO4, 40 mM NaH2PO4, 10 mM KCl, and 1 mM MgSO4) and diluted to make the final OD600 of 0.2–0.6. Take suitable volumes of the above cells into a 2 mL Eppendorf tube, and make up to 1 mL with Z Buffer. Add 25 µL 0.1% SDS and 50 µL chloroform, vortex for 30 s, and incubate at 30 °C for 15 min. The reaction was started through the addition of 200 µL of 4 mg/mL onitrophenyl-β-D-galactopyranoside (ONPG) solution at 30 °C and stopped by the addition of 500 µL of 1 M NaCO3. After removal of cell debris by centrifugation, the OD420 and OD550 of the reaction solution were detected by Evolution™ 220 spectrophotometer, and the relative activity of β-galactosidase was calculated using the formula below:

T is the reaction time (min) and V is the volume (mL) of culture used for the assay.

Construction of promoter library in the β-carotene biosynthetic pathway

The vector pMRI-34-crtE-tHMG1 and vector pMRI-35-crtYB-crtI were the kind gifts from Hongwei Yu’s lab [41]. The two gene cassettes with opposite directions of tHMG1/crtE or crtI/crtYB containing the promoter, ORF, and terminator were amplified from the above vectors. The AOX1 promoter (located in GS115 chromosome 4) and ENO2 promoter (located in GS115 chromosome 3) were chosen as the integration site. The ble (coding zeocin-resistant protein in E. coli and yeast) and kan (coding kanamycin-resistant protein in E. coli and G418-resistant protein in yeast, respectively) were chosen as screening markers. All those fragments were linked with the homologous arm by seamless cloning to yield vector pZeocin/crtE-tHMG1 and vector pG418/crtYB-crtI.

The candidate promoters (P0107, PGCW14, P0019, PGAP, P0208, and P0230) were amplified from the genomic DNA of GS115 by PCR. Two promoters in opposite directions were co-amplified by fusion PCR. Then a pool of combinations with two reversed promoters was obtained. Those promoters were inserted into BamHI/NotI sites of vector pZeocin/crtE-tHMG1 and vector pG418/crtYB-crtI with seamless cloning to yield vector pZeocin/PXXX-crtE-PYYY-tHMG1 and vector pG418/PXXX-crtYB-PYYY-crtI (PXXX and PYYY indicate the name of candidate promoters). The vector pZeocin/PXXX-crtE-PYYY-tHMG1 was linearized with PmeI and then transferred into the GS115 cell by electro-transformation. All the transformants grown on the agar plates containing zeocin were selected and co-cultured for the next round of electro-transformation with linearized pG418/PXXX-crtYB-PYYY-crtI by ScaI in ENO2 promoter. The transformants with different colors on the agar plates containing G418 (0.25 mg/mL) were picked out. The promoter combinations were verified by PCR.

Measurement of the β-carotene production

The extraction and analysis of β-carotene were performed according to a previous report [41]. Briefly, the β-carotene engineering strains were pre-cultured in 5 mL YPD broth at 30 °C, 220 rpm for 24 h. Precultures were inoculated to an initial OD600 of 0.05 in 20 mL of YPD broth with 100 mL flasks and grown under the same condition for 120 h. Samples were taken every 24 h to determine the DCW and β-carotene yield. The carotenoids were co-extracted using hot HCl-acetone. The analyses of β-carotene were performed on an HPLC system (LC 20AT) equipped with a Supersil ODS2 C18 column (4.6mm × 250mm). The mobile phase is composed of acetonitrile, methanol, and isopropanol with a volume ratio of 5:3:2, followed by a flow rate of 1 mL/min at 40 °C. The UV/VIS signals were detected at 450 nm, and the analysis time of each sample is 40 min. The standard product of β-carotene was purchased from Solarbio (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd., China). The standard curve of concentration with the peak area was verified by triplicate.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Identified promoter candidates in P. pastoris GS115.

Additional file 2. Evaluation of the growth-dependent strong promoter P0208 andP0627. (A) The relative transcriptional levels of 0627, 0208,and 0407 in YPD broth (B) The relative transcriptional levels of 0627,0208, and 0407 in YPG broth (C) The relative transcriptional levelsof 0627, 0208, and 0407 in YPM broth.

Additional file 3. Primers used for RT-qPCR and colony verification.

Additional file 4. Sequence length of the intergenic region of selected genes.

Additional file 5. Strains and vectors used in this study.

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Abbreviations

- MUT

The methanol utilization

- AOX1

Alcohol oxidase 1

- FLD1

Formaldehyde dehydrogenase 1

- DAS

Dihydroxyacetone synthase

- PEX8

Peroxisomal matrix protein

- AOX2

Alcohol oxidase 2

- FPKM

Fragments per kilobase of transcript per million base pairs sequenced

- RT-qPCR

Real‐time quantitative PCR

- GPI

Glycosylphosphatidylinositol

- GS

Glutamine synthetase

- DCW

Dry cell weight

- ORF

Open reading frame

- TADH1

ADH1 terminator

- ONPG

Onitrophenyl-β-d-galactopyranoside

Authors’ contributions

WWD, QCZ and WJG conceived the original research idea. WWD, QCZ, MHZ, and ZYJ carried out all the experiments. WWD and QCZ drafted the initial manuscript. WJG reviewed and revised the manuscript. WWD and QCZ contributed equally to this article. All authors read and approved the final manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Key R&D Program of China (2019YFA0905400, 2018YFA0903200).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher’s Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Weiwang Dou and Quanchao Zhu contributed equally to this work

Contributor Information

Weiwang Dou, Email: douww@zju.edu.cn.

Quanchao Zhu, Email: 11818296@zju.edu.cn.

Meihua Zhang, Email: meihua_zhang@zju.edu.cn.

Zuyuan Jia, Email: chiazy20@zju.edu.cn.

Wenjun Guan, Email: guanwj@zju.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Parashar D, Satyanarayana T. Enhancing the production of recombinant acidic alpha-amylase and phytase in Pichia pastoris under dual promoters [constitutive (GAP) and inducible (AOX)] in mixed fed batch high cell density cultivation. Process Biochem. 2016;51:1315–22. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2016.07.027. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Wriessnegger T, Augustin P, Engleder M, Leitner E, Muller M, Kaluzna I, Schurmann M, Mink D, Zellnig G, Schwab H, Pichler H. Production of the sesquiterpenoid (+)-nootkatone by metabolic engineering of Pichia pastoris. Metab Eng. 2014;24:18–29. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2014.04.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Araya-Garay JM, Feijoo-Siota L, Rosa-dos-Santos F, Veiga-Crespo P, Villa TG. Construction of new Pichia pastoris X-33 strains for production of lycopene and beta-carotene. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2012;93:2483–92. doi: 10.1007/s00253-011-3764-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Bhataya A, Schmidt-Dannert C, Lee PC. Metabolic engineering of Pichia pastoris X-33 for lycopene production. Process Biochem. 2009;44:1095–102. doi: 10.1016/j.procbio.2009.05.012. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Araya-Garay JM, Ageitos JM, Vallejo JA, Veiga-Crespo P, Sanchez-Perez A, Villa TG. Construction of a novel Pichia pastoris strain for production of xanthophylls. AMB Exp. 2012;2:1–8. doi: 10.1186/2191-0855-2-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Meesapyodsuk D, Chen Y, Ng SH, Chen JN, Qiu X. Metabolic engineering of Pichia pastoris to produce ricinoleic acid, a hydroxy fatty acid of industrial importance. J Lipid Res. 2015;56:2102–9. doi: 10.1194/jlr.M060954. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jeong E, Shim WY, Kim JH. Metabolic engineering of Pichia pastoris for production of hyaluronic acid with high molecular weight. J Biotechnol. 2014;185:28–36. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.05.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Liu XB, Liu M, Tao XY, Zhang ZX, Wang FQ, Wei DZ. Metabolic engineering of Pichia pastoris for the production of dammarenediol-II. J Biotechnol. 2015;216:47–55. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2015.10.005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Xu N, Zhu JX, Zhu QY, Xing YZ, Cai MH, Jiang TY, Zhou M, Zhang YX. Identification and characterization of novel promoters for recombinant protein production in yeast Pichia pastoris. Yeast. 2018;35:379–85. doi: 10.1002/yea.3301. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Vogl T, Glieder A. Regulation of Pichia pastoris promoters and its consequences for protein production. N Biotechnol. 2013;30:385–404. doi: 10.1016/j.nbt.2012.11.010. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portela RMC, Vogl T, Ebner K, Oliveira R, Glieder A. Pichia pastoris Alcohol Oxidase 1 (AOX1) Core promoter engineering by high resolution systematic mutagenesis. Biotechnol J. 2018;13:1700340. doi: 10.1002/biot.201700340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Resina D, Cos O, Ferrer P, Valero F. Developing high cell density fed-batch cultivation strategies for heterologous protein production in Pichia pastoris using the nitrogen source-regulated FLD1 promoter. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2005;91:760–7. doi: 10.1002/bit.20545. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tschopp JF, Brust PF, Cregg JM, Stillman CA, Gingeras TR. Expression of the lacZ gene from two methanol-regulated promoters in Pichia pastoris. Nucleic Acids Res. 1987;15:3859–76. doi: 10.1093/nar/15.9.3859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Cereghino JL, Cregg JM. Heterologous protein expression in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris. FEMS Microbiol Rev. 2000;24:45–66. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6976.2000.tb00532.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Cregg JM, Madden KR, Barringer KJ, Thill GP, Stillman CA. Functional characterization of the two alcohol oxidase genes from the yeast Pichia pastoris. Mol Cell Biol. 1989;9:1316–23. doi: 10.1128/mcb.9.3.1316. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hartner FS, Glieder A. Regulation of methanol utilisation pathway genes in yeasts. Microb Cell Fact. 2006;5:39. doi: 10.1186/1475-2859-5-39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sears IB, O’Connor J, Rossanese OW, Glick BS. A versatile set of vectors for constitutive and regulated gene expression in Pichia pastoris. Yeast. 1998;14:783–90. doi: 10.1002/(SICI)1097-0061(19980615)14:8<783::AID-YEA272>3.0.CO;2-Y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vassileva A, Chugh DA, Swaminathan S, Khanna N. Expression of hepatitis B surface antigen in the methylotrophic yeast Pichia pastoris using the GAP promoter. J Biotechnol. 2001;88:21–35. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(01)00254-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Waterham HR, Digan ME, Koutz PJ, Lair SV, Cregg JM. Isolation of the Pichia pastoris glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase gene and regulation and use of its promoter. Gene. 1997;186:37–44. doi: 10.1016/S0378-1119(96)00675-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Doring F, Klapper M, Theis S, Daniel H. Use of the glyceraldehyde-3-phosphate dehydrogenase promoter for production of functional mammalian membrane transport proteins in the yeast Pichia pastoris. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1998;250:531–5. doi: 10.1006/bbrc.1998.9342. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Qin XL, Qian JC, Yao GF, Zhuang YP, Zhang SL, Chu J. GAP promoter library for fine-tuning of gene expression in Pichia pastoris. Appl Environ Microb. 2011;77:3600–8. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02843-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn J, Hong J, Lee H, Park M, Lee E, Kim C, Choi E, Jung J, Lee H. Translation elongation factor 1-alpha gene from Pichia pastoris: molecular cloning, sequence, and use of its promoter. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2007;74:601–8. doi: 10.1007/s00253-006-0698-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Liang SL, Zou CJ, Lin Y, Zhang XW, Ye YR. Identification and characterization of P-GCW14: a novel, strong constitutive promoter of Pichia pastoris. Biotechnol Lett. 2013;35:1865–71. doi: 10.1007/s10529-013-1265-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Stadlmayr G, Mecklenbrauker A, Rothmuller M, Maurer M, Sauer M, Mattanovich D, Gasser B. Identification and characterisation of novel Pichia pastoris promoters for heterologous protein production. J Biotechnol. 2010;150:519–29. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2010.09.957. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Zhu T, Guo M, Zhuang Y, Chu J, Zhang S. Understanding the effect of foreign gene dosage on the physiology of Pichia pastoris by transcriptional analysis of key genes. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol. 2011;89:1127–35. doi: 10.1007/s00253-010-2944-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schwarzhans JP, Wibberg D, Winkler A, Luttermann T, Kalinowski J, Friehs K. Non-canonical integration events in Pichia pastoris encountered during standard transformation analysed with genome sequencing. Sci Rep. 2016;6:38952. doi: 10.1038/srep38952. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Xie WP, Liu M, Lv XM, Lu WQ, Gu JL, Yu HW. Construction of a controllable beta-carotene biosynthetic pathway by decentralized assembly strategy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:125–33. doi: 10.1002/bit.25002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Ledetzky N, Osawa A, Iki K, Pollmann H, Gassel S, Breitenbach J, Shindo K, Sandmann G. Multiple transformation with the crtYB gene of the limiting enzyme increased carotenoid synthesis and generated novel derivatives in Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2014;545:141–7. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2014.01.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Koussounadis A, Langdon SP, Um IH, Harrison DJ, Smith VA. Relationship between differentially expressed mRNA and mRNA-protein correlations in a xenograft model system. Sci Rep UK. 2015;5:1–9. doi: 10.1038/srep10775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Liu YS, Beyer A, Aebersold R. On the dependency of cellular protein levels on mRNA abundance. Cell. 2016;165:535–50. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Verwaal R, Wang J, Meijnen JP, Visser H, Sandmann G, van den Berg JA, van Ooyen AJJ. High-level production of beta-carotene in Saccharomyces cerevisiae by successive transformation with carotenogenic genes from Xanthophyllomyces dendrorhous. Appl Environ Microb. 2007;73:4342–50. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02759-06. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Agmon N, Mitchell LA, Cai Y, Ikushima S, Chuang J, Zheng A, Choi WJ, Martin JA, Caravelli K, Stracquadanio G, Boeke JD. Yeast golden gate (yGG) for the efficient assembly of S. cerevisiae transcription units. ACS Synth Biol. 2015;4:853–9. doi: 10.1021/sb500372z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Garcia-Ruiz E, Auxillos J, Li T, Dai J, Cai Y. YeastFab: high-throughput genetic parts construction, measurement, and pathway engineering in yeast. Methods Enzymol. 2018;608:277–306. doi: 10.1016/bs.mie.2018.05.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Xuan YJ, Zhou XS, Zhang WW, Zhang X, Song ZW, Zhang YX. An upstream activation sequence controls the expression of AOX1 gene in Pichia pastoris. FEMS Yeast Res. 2009;9:1271–82. doi: 10.1111/j.1567-1364.2009.00571.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kim D, Landmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015;12:357-U121. doi: 10.1038/nmeth.3317. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Li B, Dewey CN. RSEM: accurate transcript quantification from RNA-Seq data with or without a reference genome. BMC Bioinform. 2011;12:1–16. doi: 10.1186/1471-2105-12-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Livak KJ, Schmittgen TD. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(T)(-Delta Delta C) method. Methods. 2001;25:402–8. doi: 10.1006/meth.2001.1262. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wu SX, Letchworth GJ. High efficiency transformation by electroporation of Pichia pastoris pretreated with lithium acetate and dithiothreitol. Biotechniques. 2004;36:152–4. doi: 10.2144/04361DD02. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Looke M, Kristjuhan K, Kristjuhan A. Extraction of genomic DNA from yeasts for PCR-based applications. BioTechniques. 2017;62:325–328. doi: 10.2144/000114497. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nambu-Nishida Y, Sakihama Y, Ishii J, Hasunuma T, Kondo A. Selection of yeast Saccharomyces cerevisiae promoters available for xylose cultivation and fermentation. J Biosci Bioeng. 2018;125:76–86. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2017.08.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Xie W, Liu M, Lv X, Lu W, Gu J, Yu H. Construction of a controllable beta-carotene biosynthetic pathway by decentralized assembly strategy in Saccharomyces cerevisiae. Biotechnol Bioeng. 2014;111:125–33. doi: 10.1002/bit.25002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Identified promoter candidates in P. pastoris GS115.

Additional file 2. Evaluation of the growth-dependent strong promoter P0208 andP0627. (A) The relative transcriptional levels of 0627, 0208,and 0407 in YPD broth (B) The relative transcriptional levels of 0627,0208, and 0407 in YPG broth (C) The relative transcriptional levelsof 0627, 0208, and 0407 in YPM broth.

Additional file 3. Primers used for RT-qPCR and colony verification.

Additional file 4. Sequence length of the intergenic region of selected genes.

Additional file 5. Strains and vectors used in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.