Abstract

Objective:

Light-skin disadvantage (hypothesized to result from resentment by darker-skinned individuals) has been described in majority African-American populations but is less studied than dark-skin disadvantage. We investigated both light- and dark-skin disadvantage in a contemporary African-American study population.

Methods:

We used skin reflectance and questionnaire data from 1,693, young African-American women in Detroit, Michigan, and dichotomized outcomes as advantaged/disadvantaged. We compared outcomes for women with light vs. medium skin color with prevalence differences (PDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs), and dark-skin disadvantage with prevalence ratios (PRs) and 95% CIs for a 10-unit increase in skin color.

Results:

There was little evidence for light-skin disadvantage, but darker skin was associated with disadvantage across socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial domains. The strongest associations were for SES, but even controlling for SES, other associations included higher body mass index (PR: 1.14 95% CI: 1.08–1.20) and more stressful events (PR: 1.10 95% CI: 1.01–1.20).

Conclusions:

Dark-skin disadvantage was the predominant form of colorism. Skin color metrics in public health research can capture more information than simple racial/ethnic categories, and such research could bring awareness to the deep-rooted colorism in society.

Keywords: skin color, colorism, disparities, African-American

Introduction

Disparities in the health, well-being, and socioeconomic status (SES) of racial/ethnic groups has been a noteworthy area of research globally for decades. Special focus in the United States has been placed on inter-racial/ethnic (out-group) comparisons between American Whites and Blacks (or African-Americans) [1]. Recent studies demonstrate that marked disparities between Whites and African-Americans continue to exist and are theorized to be due at least partially to the historical and current pervasiveness of racism and discrimination [2, 3].

Historically, intra-racial/ethnic (within-group) disparities associated with differences in skin color, also known as skin tone stratification, were studied as another important dimension of inequality [4]. These differences were theorized to be due to colorism, a byproduct of racism, defined as “the discriminatory treatment of individuals falling within the same “racial” group on the basis of skin color”[5], p. 19. Stigma linked to darker skin tone, the primary aspect of colorism, has been documented globally (4), and was prominent from the time of slavery onwards in the US (7). Both during and after slavery, light or fair-skinned African-Americans (those thought to have White ancestry) were “privileged” compared to dark-skinned African-Americans, with more opportunities for education and jobs [6, 7]. The general acceptance of this color-based stratification historically is evident in African-American blues singer Big Bill Broonzy’s song in the 1930s-40s “Black, Brown, and White”

If you’re Black and gotta work for livin’, Now, this is what they will say to you, They says: ‘If you was White, You’s alright, If you was brown, Stick around, But if you’s Black, oh, brother, Get back, get back, get back.’[8]

Decades later the National Survey of Black Americans (NSBA) conducted in 1979–1980 and even more recently, the National Survey of American Life (NSAL) conducted from 2001–2003 found that skin-tone stratification was still apparent [4, 9, 10]. These nationally representative studies found that dark-skinned African-Americans had lower SES (lower income, lower family income, less education, lower occupational prestige, and less educated spouses) compared to lighter-skinned African-Americans [4, 10]. Even after accounting for SES, multiple studies conducted from the mid-1990s to early 2000s also found health outcomes (high blood pressure, elevated BMI, and stress) to be positively associated with darker skin color [1, 11–16]. These health disparities were not due to inherent biological/genetic differences but social/environment influences [14, 17]. Thus, other stressors such as discrimination/stigma were examined as potential causes of health inequalities [1]. However, currently, there is little open acknowledgement and investigation of skin tone stratification and colorism.

Outside of discrimination by Whites against African-Americans of darker complexions, discrimination by African-Americans against darker-skinned group members also has historical roots. The “paper bag” test was used by some African-Americans to assess eligibility for entrance into their parties, churches, and social organizations based on being lighter than a brown paper bag even as recent as the 1980s [18]. Data from the NSBA and the NSAL also suggest that more educated African-American men have tended to marry light-skinned women [6, 19].

Additionally, the more recent data (NSAL, 2001–2003) suggest such colorism still exists within the African-American community, and may have another layer of complexity, light-skin disadvantage (compared to medium skin) [20]. In the NSAL, light-skinned African-American men and women reported more perceived unfavorable treatment by members of their own racial/ethnic group than medium-skinned individuals [21]. This light-skin disadvantage is hypothesized to arise from resentment by dark-skinned individuals for the myriad societal privileges associated with being light-skinned. The burden on women may be even greater than men because lighter skin color more closely aligns with the European standard of beauty that was historically widespread in the US due to racism [21, 22]. This is seen in Spike Lee’s provocative 1980s film “School Daze” in a song called “Good and Bad Hair” where the darker-skinned sorority with natural hair (coined “jigaboos”) are pitted against the lighter-skinned sorority with long straight hair (coined the “wannabe Whites”) [23]. That rejection felt by light-skinned women may be even more painful than discrimination from Whites, with damaging effects on health and well-being [21]. Thus, light-skinned individuals may have more health and psychosocial disadvantage compared with medium-skinned African-Americans.

This intra-racial discrimination is less likely to impact the societal advantages of light-skinned women in an inter-racial setting because Whites still play a major role in resource distribution [21]. For example, in the NSAL, light-skinned African-American women reported perceiving the least unfavorable treatment by those outside their race and were more likely to be more educated, have higher income, and higher status jobs [4, 21]. However, in a more homogenous setting (predominantly African-American), we may see more evidence of deleterious consequences for light-skinned individuals. This was supported by a small study (conducted over the same time period as the NSAL, 2001–2002) of African-American college students which investigated the impact of skin color on psychosocial disadvantage in a majority White and a majority African-American institution. They reported that for students at a predominantly White institution, light-skinned disadvantage was not very apparent whereas in a predominantly African-American institution lighter skin tone was disadvantaged and darker skin tone was valued and associated with more acceptance and self-esteem [24]. These complexities of colorism have generally been ignored in current disparities research.

We used data from the Study of Environment, Lifestyle & Fibroids to examine both aspects of colorism, light-skin disadvantage and the more traditional dark-skin disadvantage, in a contemporary study (enrollment 2010–2012). The study population is a large sample of young African-American women from a geographic area that has been predominantly African-American for decades, Detroit, MI. In the 2010 census, over 80% of the population of Detroit was African-American (compared to 14% of Michigan). We first address the question of whether light-skin disadvantage is evident in this contemporary African-American study population, most of whom have resided throughout their lives in a geographic area with majority African-Americans. Secondly, we investigate dark-skin disadvantage. We utilize a broad range of data in order to examine outcomes in three domains: socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial.

Methods

We used skin reflectance measurements and self-reported questionnaire data from participants in an ongoing study described previously (ref will be added). The aim of the parent study was to investigate the development of uterine fibroids. In brief, starting in 2010, the study enrolled a volunteer sample of 1,693 African-American women ages 23–35 living in the Detroit, Michigan area. Recruitment materials were distributed throughout the area, primarily composed of targeted letters, a website, media announcements, flyers, brochures at health clinics, and booths at community events. Follow-up visits continued approximately every 20 months to assess fibroid incidence. Women were ineligible if they had previously been diagnosed with fibroids, had a hysterectomy, required medication for lupus, Grave’s disease, Sjogren’s scleroderma, or multiple sclerosis, or had previous radiation or chemotherapy treatment for cancer. The study was approved by institutional review boards and all participants gave informed consent.

Measurement of Skin Color

At the baseline clinic visit, skin color was measured using a digital skin reflectance instrument (DSM II ColorMeter, Cortex Technology, Denmark) similar to the Coronary Artery Risk Development in Young Adults (CARDIA) study [12]. The color measuring system provided the skin color index of the skin which ranks skin tone from light to dark starting at 0 and increasing beyond 100 for the darkest. The meter also provides a numerical Commission International d’Eclairage measure that considers lightness, and amount of green/red or blue/yellow tone of the skin [L*a*b (L=lightness, a=amount of green or red, b=amount of blue or yellow)][25]. Measurements were taken in triplicate on the right inner arm and the mean of the measurements was used. From hereon we will refer to the mean value as the skin color index. The higher the skin color index, the darker the skin tone.

Measurement of Socioeconomic, Health, and Psychosocial Outcomes

Questionnaire data regarding each participant’s socioeconomic, health, and psychosocial status were collected at enrollment by telephone interview and by both web-based and self-administered questionnaires. Weight and height were measured at the enrollment clinic visit. We dichotomized all outcomes, constructing less-advantaged and more-advantaged categories. Table 1 and Online Resource 1 provide the details on how each outcome was dichotomized and measured, respectively.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics by Skin Color for 3 Domains: Socioeconomic, Health, and Psychosocial

| Domain | Total N=1693 n % |

Light n=300 (18%) % |

Medium n=1,086 (64%) % |

Dark n=307 (18%) % |

|

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Skin Color Index (mean, SD) | 65.4 (11.0) | 49.9 (4.3) | 65.0 (5.5) | 82.0 (5.7) | |

| Age (median, IQR) | 29.3 (26.3–32.0) | 29.5 (26.3–32.2) | 29.3 (26.3–31.9) | 29.4 (26.6–32.3) | |

| 23–29 | 810 | 48 | 47 | 48 | 47 |

| 30–35 | 883 | 52 | 53 | 52 | 53 |

| Socioeconomic | |||||

| Education | |||||

| > High school/GED | 1323 | 78 | 87 | 78 | 70 |

| ≤ High school/GED | 369 | 22 | 13 | 22 | 30 |

| Missing | 1 | ||||

| Annual Income | |||||

| ≥ $20,000 | 915 | 54 | 63 | 54 | 46 |

| < $20,000 | 766 | 46 | 37 | 46 | 54 |

| Missing | 12 | ||||

| Employment | |||||

| Employed/student | 1308 | 77 | 81 | 79 | 68 |

| Unemployed/homemaker | 382 | 23 | 19 | 21 | 32 |

| Missing | 3 | ||||

| Insurance Status | |||||

| Not solely government/clinic | 959 | 58 | 68 | 57 | 50 |

| Solely government/clinic | 704 | 42 | 32 | 43 | 50 |

| Missing | 30 | ||||

| Marital Statusa | |||||

| Ever | 701 | 41 | 56 | 58 | 63 |

| Never | 992 | 59 | 44 | 42 | 37 |

| Mother’s Education | |||||

| ≥ High School/ GED | 1464 | 87 | 89 | 87 | 82 |

| < High School | 227 | 13 | 11 | 13 | 18 |

| Missing | 2 | ||||

| Health | |||||

| Body Mass Indexb | |||||

| <35 | 1013 | 60 | 62 | 64 | 45 |

| 35+ (obese class 2/3) | 401 | 40 | 38 | 36 | 55 |

| Smoking | |||||

| Never | 1245 | 74 | 78 | 74 | 69 |

| Ever | 448 | 26 | 22 | 26 | 31 |

| Alcohol at Age When Drinking the Mostc | |||||

| Low/moderate | 1002 | 59 | 59 | 61 | 52 |

| Heavy | 691 | 41 | 41 | 39 | 48 |

| Multivitamin Use | |||||

| Yes | 689 | 41 | 51 | 59 | 70 |

| No | 1004 | 59 | 49 | 41 | 30 |

| Sleep | |||||

| 7+ hours | 704 | 42 | 45 | 42 | 38 |

| <=6 hours | 989 | 58 | 55 | 58 | 62 |

| Physical Activityd | |||||

| > Low | 1409 | 84 | 83 | 85 | 83 |

| ≤ Low | 264 | 16 | 17 | 15 | 17 |

| Physical Health Diagnosise | |||||

| No | 1129 | 68 | 71 | 68 | 65 |

| Yes | 539 | 32 | 29 | 32 | 35 |

| Missing | 25 | ||||

| Mental Health Diagnosisf | |||||

| No | 1331 | 80 | 76 | 82 | 80 |

| Yes | 327 | 20 | 24 | 18 | 20 |

| Missing | 35 | ||||

| Psychosocial | |||||

| Adulthood | |||||

| Support | |||||

| More support | 1367 | 81 | 87 | 79 | 80 |

| Less support | 326 | 19 | 13 | 21 | 20 |

| Stressors | |||||

| Overall Daily Stress | |||||

| Less stress | 1317 | 78 | 79 | 78 | 75 |

| More stress | 376 | 22 | 21 | 22 | 25 |

| Stress Past 30 Days (PSS-4) | |||||

| Less stress | 1342 | 79 | 76 | 80 | 78 |

| More stress | 351 | 21 | 24 | 20 | 22 |

| Financial Stress | |||||

| Less stress | 1470 | 87 | 88 | 88 | 82 |

| More stress | 222 | 13 | 12 | 12 | 18 |

| Missing | 1 | ||||

| Number of stressful events | |||||

| Less stress | 1352 | 80 | 81 | 81 | 76 |

| More stress | 332 | 20 | 19 | 19 | 24 |

| Missing | 9 | ||||

| Racism | |||||

| During your 20s, how often did you experience racism? | |||||

| Rarely | 1322 | 78 | 76 | 78 | 80 |

| Often | 371 | 22 | 24 | 22 | 21 |

| How often do you think about your race? | |||||

| Less than once/day | 1465 | 87 | 86 | 87 | 86 |

| At least once/day | 228 | 13 | 14 | 13 | 14 |

| In the past 5 years how often have you, personally, been followed or watched by security guards or clerks because of your race? | |||||

| Rarely | 1194 | 71 | 72 | 71 | 68 |

| Often | 498 | 29 | 28 | 29 | 32 |

| Missing | 1 | ||||

| In the past 5 years how often have you, personally, been called insulting names related to your race by Whites? | |||||

| Never | 1108 | 65 | 68 | 64 | 68 |

| Ever | 584 | 35 | 32 | 36 | 32 |

| Missing | 1 | ||||

| Childhood | |||||

| Support | |||||

| More support | 1194 | 71 | 74 | 70 | 70 |

| Less support | 499 | 29 | 26 | 30 | 30 |

| Before 20, how often did you experience racism? | |||||

| Rarely | 1313 | 78 | 72 | 79 | 77 |

| Often | 380 | 22 | 28 | 21 | 23 |

Ever married includes those who have ever been legally married or lived with someone as though married

Body mass index was calculated as weight (kg)/height (m)2

This variable reflected the drinking level each woman reported for the age(s) when she was drinking the most. Low drinkers were those who never had 10 or more drinks in a year. Heavy drinkers were those who usually drank 6 or more drinks on days when they drank or drank 4 + drinks per sitting at least 2–3 times a month. Moderate drinkers were all others.

≤low=less than 1 hour/week vigorous and 2 hours/week moderate and 14 hours/week; >low were all others.

Asthma, diabetes, high blood pressure, high cholesterol, heart attack, angina, and/or stroke

Depression, anxiety/panic attacks, and/or bipolar disorders

See Supplemental Table 1 for further description of variables.

Statistical Analyses

First, we addressed the question of possible light-skin disadvantage. We hypothesized that light-skinned women may be disadvantaged only when compared to medium-skinned women. Based on the distribution of skin color index in our population which ranged from 29.3–106.1, light-skin was categorized as 29.3-<55 and medium skin as 55–75. Dark-skinned women, those with a skin color index >75, were excluded. We used binomial regression to test for associations between light vs. medium skin-color group and being in the less-advantaged category of each outcome. We computed prevalence differences (PD) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for light vs. medium for each of the outcomes. For example, we determined if more women in the light skin group reported less education than the medium skin group.

As sensitivity analyses for the question of light-skin disadvantage, we used 3 other category cut points for skin color: tertiles (<60.4; 60.4–69.8; >69.8), to reflect the percentage groups from the NSAL [21] [lower 26% of skin color index: light (<58); middle 41% (58–70): medium; upper 33% (>70): dark], and the percentile groups used in the CARDIA study [12] [lower 25% of skin color index: light (<58); middle 50% (58–73); upper 25% ( >73): dark]. Again we only compared the light-skin vs. medium-skin categories.

To address the question of dark-skin disadvantage for those outcomes that did not show light-skin disadvantage, we considered the full range of skin reflectance. For these analyses we examined the skin color index as a linear variable and estimated the prevalence ratio and 95% CIs associated with being in the less-advantaged outcome category for a 10-unit increase in skin color.

For both analysis questions we examined the impact of adjusting for participant’s age, education, and participant’s mother’s education. Age did not influence the associations and education and mother’s education did not impact the light-skin disadvantage analysis. However, for the dark-skinned disadvantage analysis, both the education variables were important and were included as adjustment factors in the presented results. Results without these adjustment factors are shown in Online Resource 2.

As a sensitivity analysis for both light and dark-skin disadvantage, we restricted the sample to participants who reported living in Detroit their entire life (n=1,038) to have an even more homogenous sample regarding their social environment and interactions.

All analyses were conducted with SAS 9.4.

Results

The total study population included 1,693 African-American women with a mean age of Over 75% had some college education, but only ~50% made over $20,000 per year and 77% were employed or students full-time. Almost 25% had ever smoked and close to 25% were in obese class 2 or 3 (BMI ≥ 35 kg/m2) (Table 1). Among the full sample, the mean skin color index was 65 (SD=11), ranged from 29–106, and was fairly normally distributed (Online Resource 3). Based on our cut points, the distribution of light-skinned, medium-skinned, and dark-skinned was 18% (n=300), 64% (n=1,086), and 18% (n=307), respectively.

Light-Skin Disadvantage (Light-Skin vs. Medium-Skin)

Only two outcomes across the domains showed light-skin disadvantage where PDs were significantly higher in the light-skinned group compared to the medium-skinned group. For the socioeconomic domain, none of the outcomes showed light-skinned disadvantage. For the health domain, 5% more of the light-skinned women vs. medium-skinned women reported a mental health diagnosis (95% CI: 0.1%, 11%). For the psychosocial domain, 6% more of the light-skinned group reported experiencing racism during childhood than the medium-skinned group (95% CI: 0.9%, 12%).

After using the NSAL and CARDIA cut points which created a broader light-skinned category, but reduced the medium category, racism in childhood remained higher among the light-skinned group compared to the medium-skinned group and mental health diagnoses was still higher among the light-skinned group but the association was slightly attenuated (data not shown). However, after using tertiles for category cut points which made both groups of equal size, only the racism during childhood remained higher in the light-skinned group. Restricting to participants who only lived in Detroit for their entire lives (n=1,038), yielded very similar results to the original (data not shown).

Dark-Skin Disadvantage (Continuous Skin Color Index)

Age

Age was not associated with continuous skin color index in our sample (PR: 1.00 95% CI: 0.96–1.04).

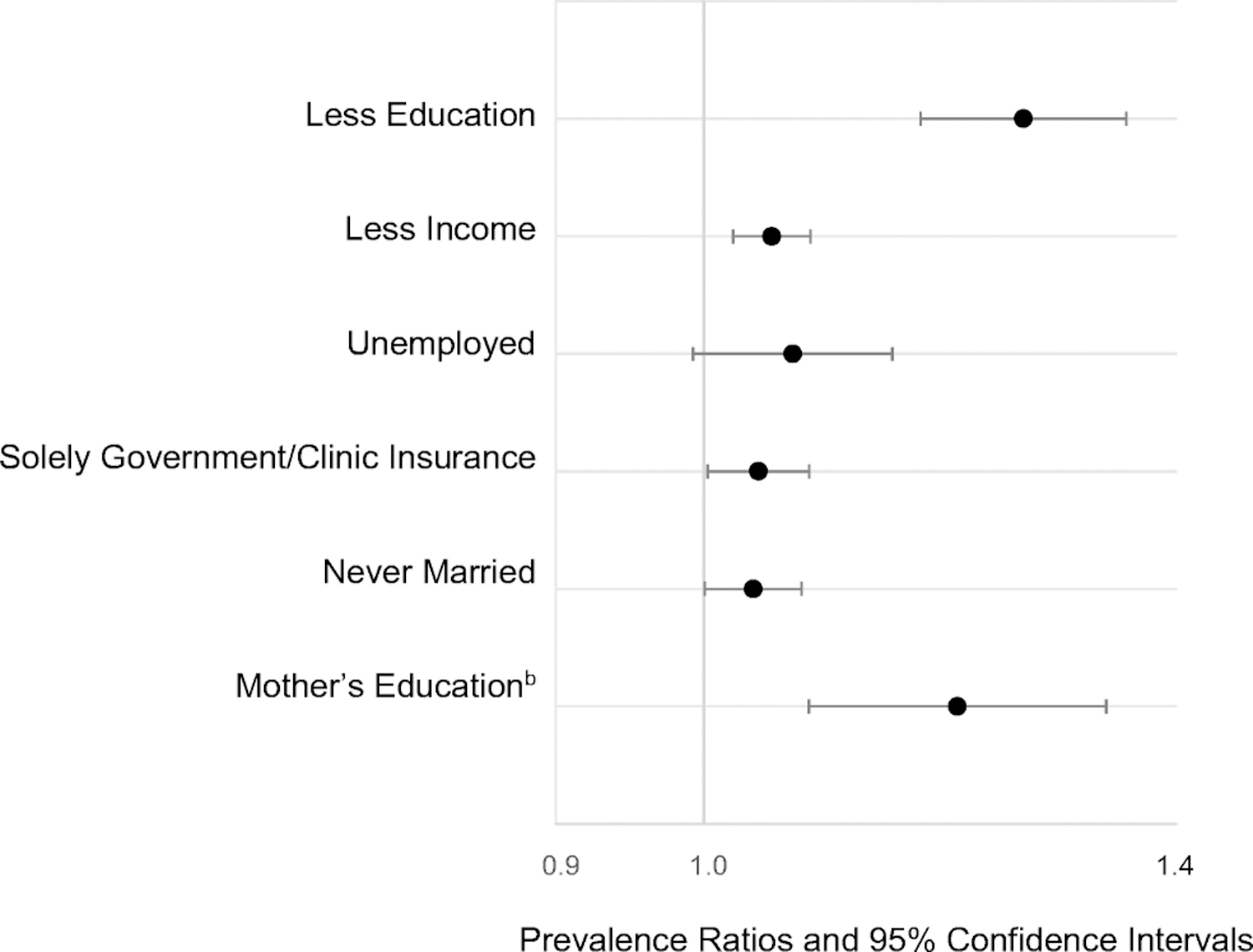

Socioeconomic domain (Figure 1)

Fig 1.

Adjusteda Prevalence Ratios for 10 Unit Increase in Mean Skin Color Index: Socioeconomic Domain

aAdjusted for mother’s and participant’s education

bUnadjusted

See Online Resource 1 for description of outcomes

For the socioeconomic domain, darker skin color was associated with both lower education (PR: 1.26 95% CI: 1.17–1.35) (controlled for maternal education) and lower maternal education (PR: 1.20 95% CI: 1.08–1.33) (unadjusted). Even controlling for both education and maternal education, a darker skin color was associated with lower income (PR: 1.05 95% CI: 1.02 −1.08) and having solely government health insurance (PR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.01–1.08). Unemployment (PR: 1.07, 95% CI: 0.99–1.14) and never being married (PR: 1.04, 95% CI: 1.00–1.07) were borderline significant.

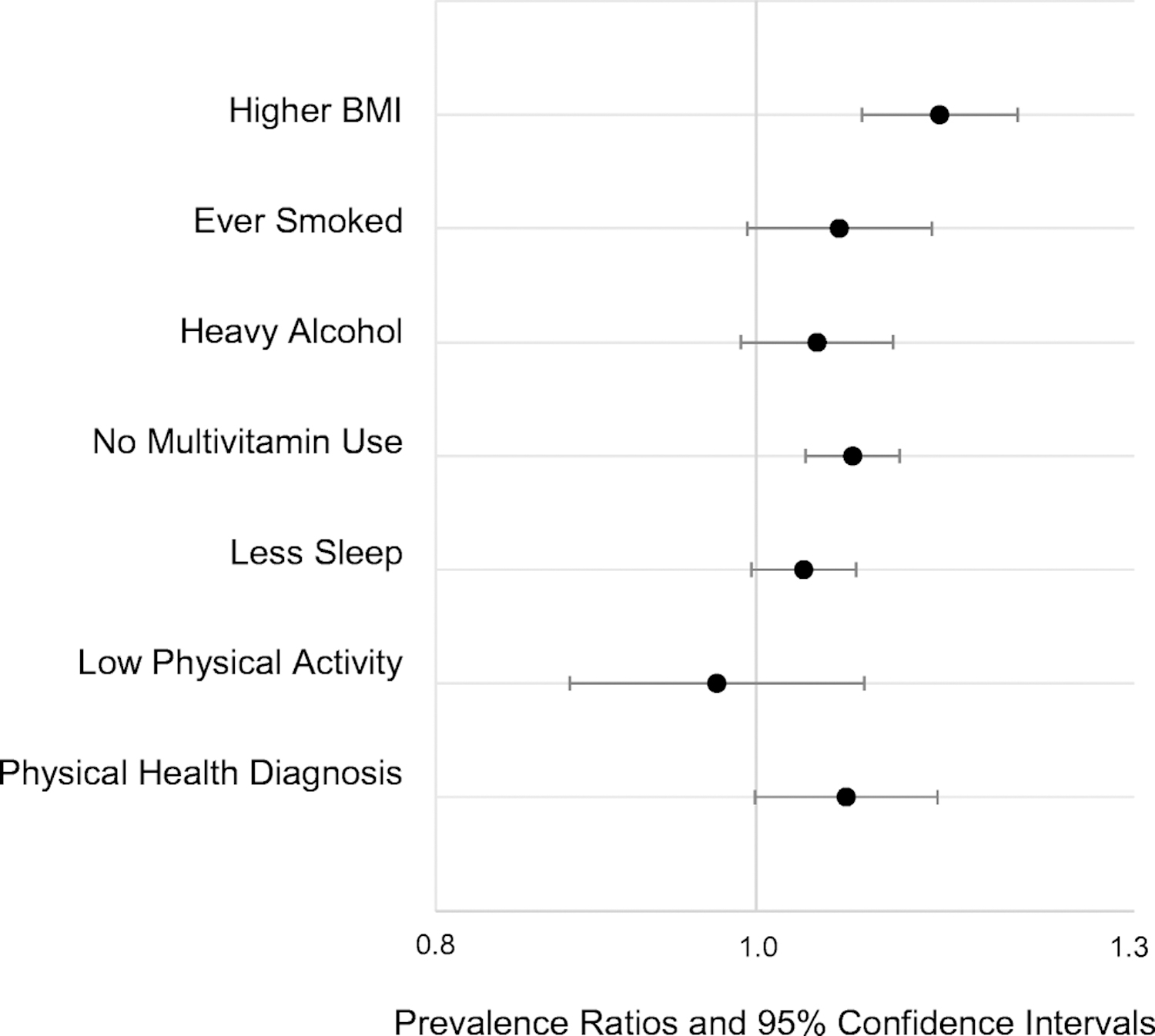

Health domain (Figure 2)

Fig 2.

Adjusteda Prevalence Ratios for 10 Unit Increase in Mean Skin Color Index: Health Domain

aAdjusted for mother’s and participant’s education

See Online Resource 1 for description of outcomes

For the health domain, after controlling for participant and maternal education, higher BMI (PR: 1.14 95% CI: 1.08–1.20) and not using a multivitamin (PR: 1.07 95% CI: 1.03–1.10) were significantly associated with darker skin color. Ever smoking (PR: 1.06 95% CI: 0.99–1.13), heavy alcohol (PR: 1.04 95% CI: 0.99–1.10), getting less sleep (PR: 1.03 95% CI: 1.00–1.07), and having a physical health diagnosis (PR: 1.06 95% CI: 1.00–1.13) were borderline significant. Having low physical activity (PR: 0.97 95% CI: 0.88–1.08) was not positively associated with continuous skin color index.

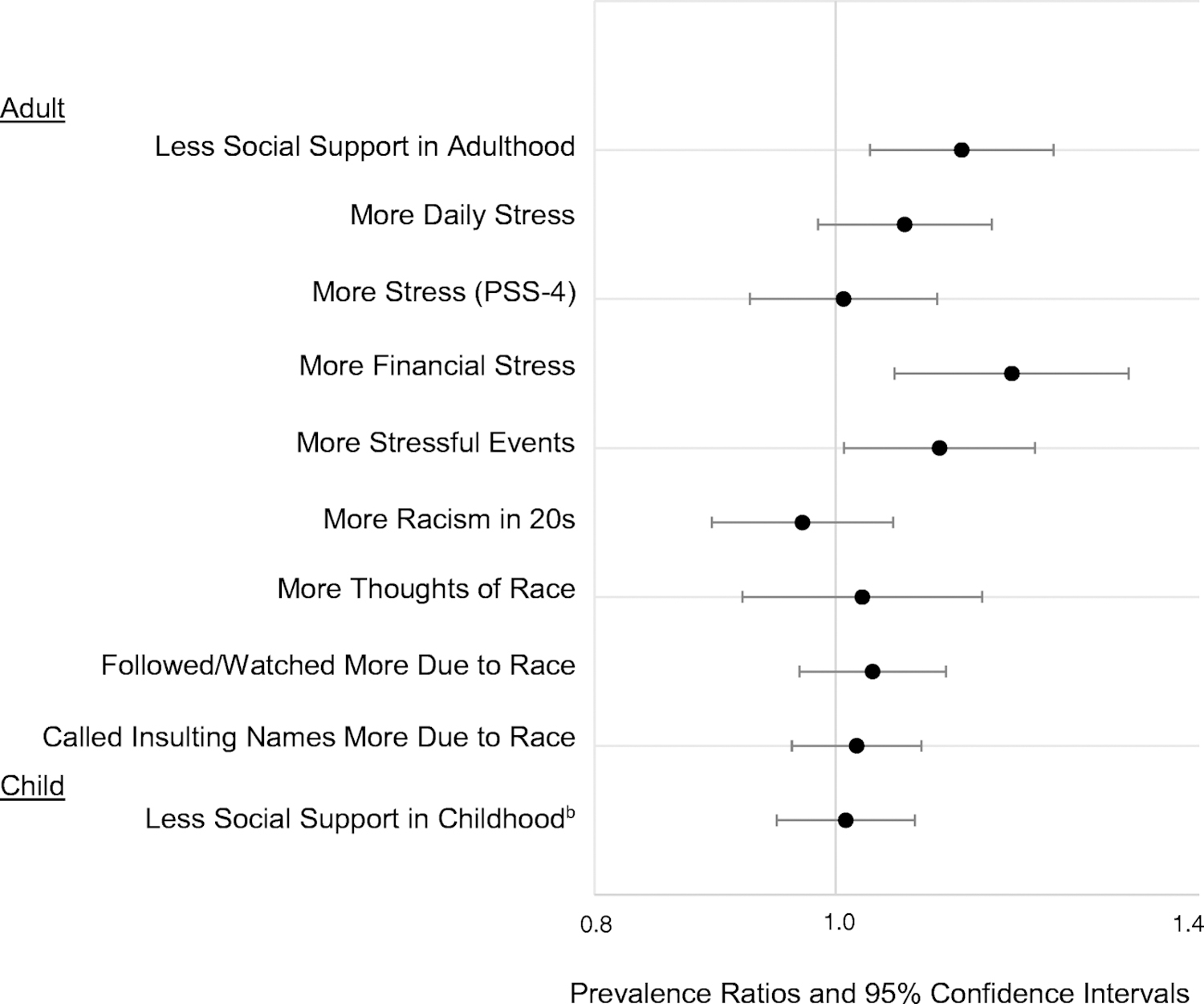

Psychosocial domain (Figure 3)

Fig 3.

Adjusteda Prevalence Ratios for 10 Unit Increase in Mean Skin Color Index: Psychosocial Domain

PSS: perceived stress scale

aAdjusted for mother’s and participant’s education

bAdjusted for mother’s education only

See Online Resource 1 for description of outcomes

For the psychosocial domain, after controlling for education and maternal education, reporting less social support in adulthood was associated with darker skin color (PR: 1.12 95% CI: 1.03–1.22). Also reporting more stressful events in the past 12 months (PR: 1.10 95% CI: 1.01–1.20) and more financial stress (difficulty paying for basic expenses) (PR: 1.18 95% CI: 1.06–1.31) were associated with being darker-skinned. However, the questions on racism, daily stress, and childhood social support did not appear to be associated with continuous skin color.

After restricting to participants who only lived in Detroit for their entire lives (n=1,038), the results were very similar (data not shown).

Discussion

In this large sample of young African-American women in a predominantly African-American setting, we found little evidence of light-skin disadvantage. However, dark skin disadvantage was apparent in all domains even after adjustment for SES. These findings further support the limited recent data indicating continued skin-tone-based disparities [4, 12] that are only partially explained by socioeconomic and generational disadvantage.

Light-skinned disadvantage was hypothesized based on data suggesting resentment from darker-skinned African-Americans might lead to disadvantage within a mostly African-American community [21, 24]. The two outcomes that did show evidence of light-skin disadvantage, having a mental health diagnosis and experiencing racism as a child, are both related to health and psychosocial well-being, in line with the hypothesis. Given that the question did not specifically ask if the racism experienced as a child was from Whites or other African-Americans, the light-skinned group’s experience of more childhood racism than the medium-skinned group needs further follow-up of possible factors beyond within-ethnic group discrimination [13, 26], such as more opportunity for light-skinned children to be around other race/ethnicities due to higher SES or family contexts for biracial children.

Regarding dark-skin disadvantage, our findings on SES are similar to the earlier NSAL and CARDIA in that we saw associations between darker skin color and participant/maternal education, and income [4, 12]. Unlike the NSAL, we found positive associations for employment and marital status (although borderline significant) [6]. While NSAL did not find positive associations with employment and marital status, it did find that darker-skinned men had less prestigious jobs [4] and that lighter-skinned women were more likely to have higher educated spouses possibly leading to better life chances [6].

Regarding the health factors, we found that darker skin was associated with higher BMI similar to other studies [12, 16]. To our knowledge, no prior studies investigated multivitamin use by skin color. Our finding of lighter-skinned women having more multivitamin use may indicate better health in these women, given that those who use supplements are more likely than non-users to incorporate other healthy habits in their lifestyle [27]. Our suggestive associations between darker skin color and ever smoking, heavy alcohol, and getting less sleep require future study. In CARDIA, there was a higher percentage of current smokers among darker-skinned African-Americans although the percentages for medium and light-skinned were very similar Studies have found that increased racism/discrimination (found to be associated with darker skin color in other studies [13, 21, 28, 29], though less so in ours) is related to poorer sleep [30]. Also, although borderline significant, our findings of an association between having a physical health diagnosis and darker skin color are in line with other studies [15].

For the psychosocial domain stressors, similar to Uzogara, 2017, we found more stressful events and more financial stress were associated with darker skin tone although more general measures of daily stress were not [15]. Reporting less social support in adulthood was also associated with darker skin tone. Self-reported perceived racism in adulthood was not associated with skin color. Previous studies have mixed results, [31–33] [13, 21, 28, 29] which may partially be influenced by how skin tone is measured and in what context (adolescence or adulthood). Studies using perceived skin tone, especially self-reported by the respondent vs. interviewer, tend to find associations between skin tone and perceived discrimination [13], but this may result from self-perceptions of skin tone being influenced by discriminatory treatment from others [13, 34]. Studies also vary in questions asked about perceived racial discrimination and whether they solely focus on discrimination from Whites or include discrimination from other African-Americans.

Our assessment of perceived racism/discrimination was limited. Only two questions specifically asked about discrimination from Whites and none asked specifically about discrimination from African-Americans. Nor did we ask participants specifically about discrimination ‘due to their skin color” or assess their own skin color subjectively. More detailed assessment would have allowed us to compare perceived skin tone with measured skin tone and better understand potential associations with discrimination. Future studies should include assessments designed specifically for the types of racism, discrimination or colorism under investigation and to include both perceived (interviewer/respondent) and objective measures of skin tone.

Our study also has other limitations. First, we rely on recall and willingness to report. However, web-based questionnaires were used for sensitive questions so that an interviewer’s presence did not influence answers. Second, our sample is from a single metropolitan area with its own racial and economic history which could affect generalizability. The participants were more educated [35] but had less household income [36] than the general population of African-American women in the US.

The strengths of this study are the large sample of young African-American women enabling us to examine intra-racial differences, the objective measurement of skin color, detailed questionnaire data, and the use of frequencies vs. yes/no questions to describe some factors (racism, stress, etc.). We also used computer assisted web interviews for more sensitive questions on racism limited social desirability bias. In addition, we restricted our analyses to a sample who lived in the Detroit area for life and thus may have similar societal interactions.

Public Health Implications

In conclusion, we found little evidence to support light skin disadvantage, a phenomenon hypothesized to arise from within-group discrimination. We did find that lighter-skinned individuals may be more vulnerable to mental health outcomes and experiencing race-related trauma in childhood. This requires further study especially with more appropriate psychosocial measures. Our study did reveal that the pervasive disparities for darker-skinned women across multiple facets of life, especially socioeconomically, are still present for these young women. It also corroborates the idea that colorism is an overall measure of “social experience over the entire lifecourse” ([13], p. 411). Given differences by color, screenings and interventions may need to be further targeted.

The influence of colorism among those who self-identify as African-American is often overlooked and rarely measured in health disparities research [1, 13, 26], even though socioeconomic inequality between darker-skinned and lighter-skinned African-Americans was well documented in the late 20th century (NSBA) and early 21st century (NSAL) [6, 37]. This study extends the research to more recent years, and expands the domains of disadvantage investigated. It also supports findings from studies that investigate specific societal contexts. For example, treatment of students by teachers and defendants by judges and juries are related to skin color [38–43]. In national samples, African-American female students with darker skin were more likely to receive out of school suspensions than lighter-skinned female African-Americans and White students [39, 41]. Also, male and female defendants perceived to be more stereotypically “Black” (by darker skin color and/or facial features), were more likely to have longer or more severe sentences [38, 40, 42, 43] even after adjusting for race.

Continuing to extend research on colorism to Hispanics [44] and other groups is warranted. Given that most public health researchers explore race/ethnicity as a variable of interest, they can capture more information to understand health disparities by asking about and/or measuring skin color than simply categorizing on race/ethnicity. Using skin color metrics in future research will also bring more awareness to the deeply ingrained issue of both inter-and intra-racial colorism in our society today.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements:

We thank Drs. Sandler and Gaston for reviewing a draft of the manuscript. We also thank our collaborators and study staff at the Henry Ford Health System (Detroit, Michigan) and Social and Scientific Systems (Research Triangle Park, North Carolina). The research was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Health (NIH), National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (10-E-N044). Funding also came from the American Recovery and Reinvestment Act funds designated for NIH research.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This Author Accepted Manuscript is a PDF file of a an unedited peer-reviewed manuscript that has been accepted for publication but has not been copyedited or corrected. The official version of record that is published in the journal is kept up to date and so may therefore differ from this version.

Conflicts of interest/Competing interests: None declared

Availability of data and material: Data have not been anonymized and are not yet publicly available.

Code availability: Not applicable.

Ethics Approval: This was a retrospective study. The parent study was approved by the institutional review boards of the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences and Henry Ford Health. All participants submitted informed consent.

REFERENCES

- 1.Williams DR and Mohammed SA, Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med, 2009. 32(1): p. 20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Williams DR, Miles to Go before We Sleep: Racial Inequities in Health. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 2012. 53(3): p. 279–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Williams DR, Priest N, and Anderson NB, Understanding associations among race, socioeconomic status, and health: Patterns and prospects. Health psychology : official journal of the Division of Health Psychology, American Psychological Association, 2016. 35(4): p. 407–411. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Monk EP Jr., Skin Tone Stratification among Black Americans, 2001–2003. Social Forces, 2014. 92(4): p. 1313–1337. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Herring C, Bleaching out the color line?: The skin color continuum and the tripartite model of race. Race and Society, 2002. 5: p. 17–31. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Monk EP, Skin Tone Stratification among Black Americans, 2001–2003. Social Forces, 2014. 92(4): p. 1313–1337. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Keith VM and Herring C, Skin Tone and Stratification in the Black-Community. American Journal of Sociology, 1991. 97(3): p. 760–778. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Broonzy B, Black, Brown, and White, in Trouble in Mind. 2000, Smithsonian Folk Ways Recordings. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hughes M and Hertel BR, The Significance of Color Remains: A Study of Life Chances, Mate Selection, and Ethnic Consciousness among Black Americans. Social Forces, 1990. 68(4): p. 1105–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Keith VM and Herring C, Skin Tone and Stratification in the Black Community. American Journal of Sociology, 1991. 97(3): p. 760–778. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Gravlee CC and Dressler WW, Skin pigmentation, self-perceived color, and arterial blood pressure in Puerto Rico. Am J Hum Biol, 2005. 17(2): p. 195–206. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hargrove TW, BMI Trajectories in Adulthood: The Intersection of Skin Color, Gender, and Age among African Americans. J Health Soc Behav, 2018. 59(4): p. 501–519. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Monk EP Jr., The Cost of Color: Skin Color, Discrimination, and Health among African-Americans. AJS, 2015. 121(2): p. 396–444. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Non AL, Gravlee CC, and Mulligan CJ, Education, genetic ancestry, and blood pressure in African Americans and Whites. Am J Public Health, 2012. 102(8): p. 1559–65. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Uzogara EE, Dark and sick, light and healthy: black women’s complexion-based health disparities. Ethn Health, 2017: p. 1–22. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 16.Sweet E, et al. , Relationships Between Skin Color, Income, and Blood Pressure Among African Americans in the CARDIA Study. American Journal of Public Health, 2007. 97(12): p. 2253–2259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gravlee CC, Dressler WW, and Bernard HR, Skin color, social classification, and blood pressure in southeastern Puerto Rico. Am J Public Health, 2005. 95(12): p. 2191–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Audrey Elisa K, The Paper Bag Principle: Of the Myth and the Motion of Colorism. The Journal of American Folklore, 2005. 118(469): p. 271–289. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Hunter ML, “If You’re Light You’re Alright”: Light Skin Color as Social Capital for Women of Color. Gender and Society, 2002. 16(2): p. 175–193. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Celious A.a.O., D, Race From the Inside: An Emerging Heterogeneous Race Model. Journal of Social Issues, 2001. 57(1): p. 149–165. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Uzogara EE and Jackson JS, Perceived skin tone discrimination across contexts: African American women’s reports. Race and Social Problems, 2016. 8(2): p. 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hill ME, Skin color and the perception of attractiveness among African Americans: Does gender make a difference? Social Psychology Quarterly, 2002. 65(1): p. 77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lee S, School Daze. 1988.

- 24.Harvey RD, et al. , The Intragroup Stigmatization of Skin Tone Among Black Americans. Journal of Black Psychology, 2005. 31(3): p. 237–253. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shriver MD and Parra EJ, Comparison of narrow-band reflectance spectroscopy and tristimulus colorimetry for measurements of skin and hair color in persons of different biological ancestry. Am J Phys Anthropol, 2000. 112(1): p. 17–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uzogara EE and Jackson JS, Perceived Skin Tone Discrimination Across Contexts: African American Women’s Reports. Race and Social Problems, 2016. 8(2): p. 147–159. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Dickinson A and MacKay D, Health habits and other characteristics of dietary supplement users: a review. Nutr J, 2014. 13: p. 14. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hersch J, Skin color, physical appearance, and perceived discriminatory treatment. The Journal of Socio-Economics, 2011. 40(5): p. 671–678. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Klonoff EA and Landrine H, Is skin color a marker for racial discrimination? Explaining the skin color-hypertension relationship. J Behav Med, 2000. 23(4): p. 329–38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Slopen N, Lewis TT, and Williams DR, Discrimination and sleep: a systematic review. Sleep Med, 2016. 18: p. 88–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Keith VM, et al. , Discriminatory Experiences and Depressive Symptoms among African American Women: Do Skin Tone and Mastery Matter? Sex Roles, 2010. 62(1–2): p. 48–59. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Borrell LN, et al. , Self-reported health, perceived racial discrimination, and skin color in African Americans in the CARDIA study. Soc Sci Med, 2006. 63(6): p. 1415–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Landor AM, et al. , Exploring the Impact of Skin Tone on Family Dynamics and Race-Related Outcomes. Journal of family psychology : JFP : journal of the Division of Family Psychology of the American Psychological Association (Division 43), 2013. 27(5): p. 817–826. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Villarreal A, Flawed Statistical Reasoning and Misconceptions about Race and Ethnicity. American Sociological Review, 2012. 77(3): p. 495–502. [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bureau, U.S.C., Educational Attainment of the Population 18 Years and Over, by Age, Sex, Race, and Hispanic Origin: 2010, in Current Population Survey, 2010 Annual Social and Economic Supplement. 2010.

- 36.Bureau, U.S.C., Current Population Survey, in 1968 to 2019 Annual Social and Economic Supplements (CPS ASEC). 2020.

- 37.Hughes M and Hertel BR, The Significance of Color Remains - a Study of Life Chances, Mate Selection, and Ethnic-Consciousness among Black-Americans. Social Forces, 1990. 68(4): p. 1105–1120. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Blair IV, Judd CM, and Chapleau KM, The influence of Afrocentric facial features in criminal sentencing. Psychol Sci, 2004. 15(10): p. 674–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Blake JJ, et al. , The role of colorism in explaining African American females’ suspension risk. Sch Psychol Q, 2017. 32(1): p. 118–130. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Eberhardt JL, et al. , Looking deathworthy: perceived stereotypicality of Black defendants predicts capital-sentencing outcomes. Psychol Sci, 2006. 17(5): p. 383–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hannon L, DeFina R, and Bruch S, The Relationship Between Skin Tone and School Suspension for African Americans. Race and Social Problems, 2013. 5(4): p. 281–295. [Google Scholar]

- 42.King RD and Johnson BD, A Punishing Look: Skin Tone and Afrocentric Features in the Halls of Justice. Ajs, 2016. 122(1): p. 90–124. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Viglione J, Hannon L, and DeFina R, The impact of light skin on prison time for black female offenders. The Social Science Journal, 2011. 48(1): p. 250–258. [Google Scholar]

- 44.Cuevas AG, Dawson BA, and Williams DR, Race and Skin Color in Latino Health: An Analytic Review. American journal of public health, 2016. 106(12): p. 2131–2136. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.