Abstract

Background: N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification is one of the most common chemical modifications of eukaryotic mRNAs, which play an important role in tumors and cardiovascular disease through regulating mRNA stability, splicing and translation. However, the changes of m6A mRNA and m6A-related enzymes in pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) remain largely unexplored.

Methods: MeRIP-seq was used to identify m6A methylation in lung tissues from control and MCT-PAH rats. Western blot and immunofluorescence were used to evaluate expression of m6A-related enzymes.

Results: Compared with control group, m6A methylation was mainly increased in lung tissues from MCT-PAH rats. The up-methylated coding genes in MCT-PAH rats were primarily enriched in processes associated with inflammation, glycolysis, ECM-receptor interaction and PDGF signal pathway, while genes with down-methylation were enriched in processes associated with TGF-β family receptor members. The expression of FTO and ALKBH5 downregulated, METTL3 and YTHDF1 increased and other methylation modification-related proteins was not significantly changed in MCT-PAH rats lung tissues. Immunofluorescence indicated that expression of FTO decreased and YTHDF1 increased in small pulmonary arteries of MCT-PAH rats.

Conclusion: m6A levels and the expression of methylation-related enzymes were altered in PAH rats, in which FTO and YTHDF1 may play a crucial role in m6A modification.

Keywords: pulmonary arterial hypertension, N6-methyladenosine, FTO, YTHDF1

INTRODUCTION

Pulmonary arterial hypertension (PAH) is a progressive disease with unfavorable treatment outcomes and poor prognosis [1]. The pathogenic mechanisms of PAH primarily include inflammation, immune abnormalities, oxidative stress and epigenetic changes, which cause pulmonary vasoconstriction and vascular remodeling [2]. Typical pathological characteristics of PAH are intimal hyperplasia resulting in cavity stenosis or occlusion, muscular thickening in the small pulmonary arterioles, adventitial fibrosis and in situ thrombosis, which is related to abnormalities in the proliferation and apoptosis of endothelial cells and pulmonary arterial smooth muscle cells and extracellular matrix remodeling [2, 3]. Currently available drugs aim mainly to decrease pulmonary vasoconstriction rather than reverse vascular remodeling [4]. However, end-stage PAH is caused mainly by vascular remodeling [5, 6], thus, the need to identify a new approach to treat vascular remodeling is extremely urgent.

Numerous studies have indicated that epigenetic modifications, including DNA methylation, histone modifications and microRNA dysregulation, play important roles in regulating PAH [7]. RNA, an intermediate in the flow of genetic information from DNA to proteins, is an important part of the central dogma of molecular biology, and its various chemical modifications mediate the regulation of many biological processes [8]. N6-methyladenosine (m6A) modification of RNA transcripts is the most prevalent modification in many classes of RNA [9]. m6A modification is a critical regulator of mRNA stability, protein expression, and several other cellular processes [10]. Recently, a transcriptome-wide map of the m6A modification of circular RNAs (circRNAs) in hypoxia-mediated pulmonary hypertension (HPH) was constructed, and the level of m6A circRNAs was found to be decreased in HPH [11]. However, changes in m6A mRNA methylation and the expression levels of m6A-related enzymes in PAH lung tissues remain largely unexplored.

m6A modification is one of the most abundant and prevalent internal modifications of mRNA, and like DNA methylation, it is dynamically regulated by various m6A-related enzymes including writers, erasers and readers [12]. The installation of m6A is catalyzed by “writers”, such as the multicomponent methyltransferase complex consisting of Methyltransferase Like 3 and 14 (METTL3, METTL14) [13, 14]. “Erasers”, including fat mass and obesity-associated protein (FTO) and alkB homolog 5 (ALKBH5), are responsible for catalyzing the removal of m6A methylation [15, 16]. “Readers”, such as the YT521-B homology (YTH) domain-containing protein family, which includes YTHDF (YTHDF1, YTHDF2, YTHDF3), YTHDC1, and YTHDC2, specifically recognize m6A and regulate the splicing, localization, degradation and translation of RNA [17, 18].

In this study, we used methylated RNA immunoprecipitation sequencing (MeRIP-seq) to establish the transcriptome-wide m6A methylome profile of lung tissue from rats with monocrotaline (MCT)-induced PAH. Then, western blot and immunofluorescence were used to detect methylation modification-related enzymes. Moreover, we screened potential target transcripts involved in PAH.

RESULTS

Hemodynamic test

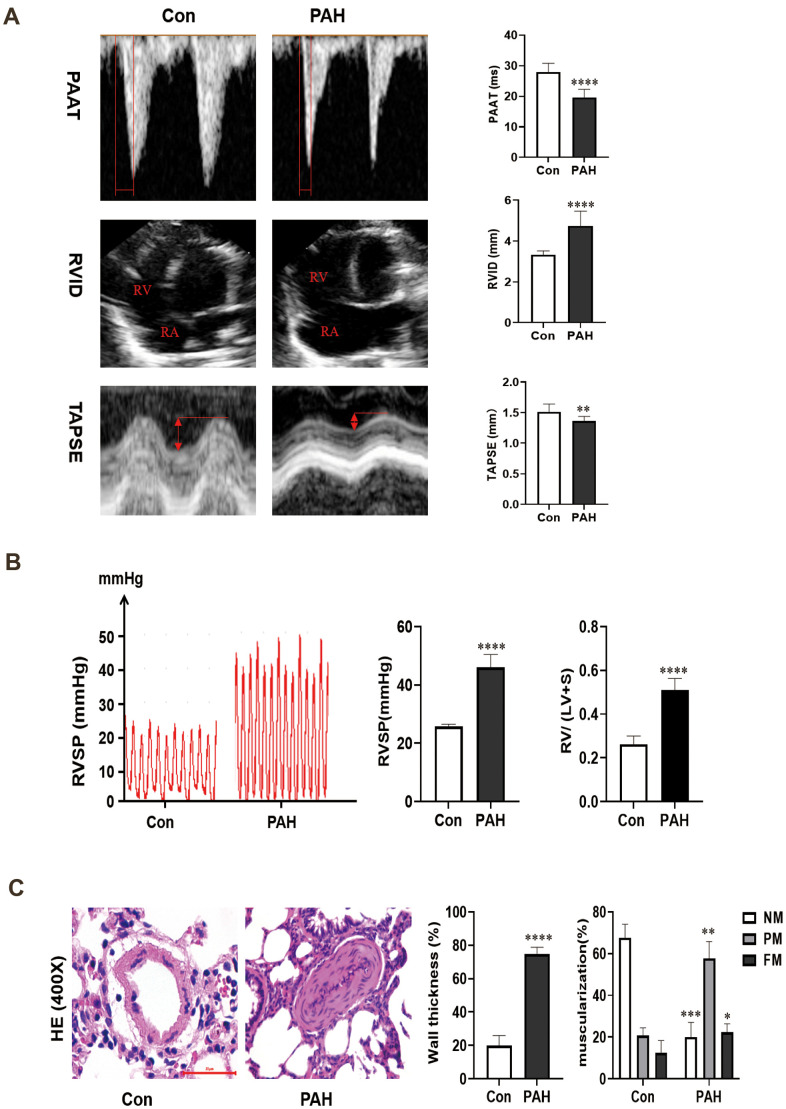

The pulmonary artery velocity profile in the PAH group was dagger-shaped, and the pulmonary artery blood flow acceleration time (PAAT) was correspondingly reduced compared to that in the control group (19.60 ± 2.54 vs 27.88 ± 2.71 ms, p < 0.0001). In addition, the ventricular septum was significantly shifted to the left ventricle, and the right ventricle was enlarged in the PAH group compared to the control group (4.74 ± 0.69 vs 3.34 ± 0.17 mm, p < 0.0001). Compared to that in the control group, the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE) was greatly reduced in the PAH group (1.36 ± 0.07 vs 1.51 ± 0.12 mm, p < 0.01) (Figure 1A). Four weeks after MCT injection, the right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP) in the PAH group was elevated (45.97 ± 4.25 mmHg vs 25.74 ± 0.73 mmHg, P < 0.0001), and the RV/ (LV + S) value was increased in the PAH group compared with the control group (0.51± 0.05 vs 0.26 ± 0.03 g, p < 0.0001) (Figure 1B).

Figure 1.

(A) Changes of echocardiography in rats after intraperitoneal injection of monocrotaline (MCT) for 4 weeks. (B) The hemodynamic test results of the two groups. Compared with the control group, the right ventricular systolic pressure was significantly increased in the PAH group, and RV/ (LV + S) also increased in the PAH group. (C) Pulmonary artery HE staining images of the control group and PAH group were obtained under microscopy. Pulmonary artery remodeling was observed in PAH group compared with control group. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01, ***P < 0.001, ****P < 0.0001.

Hematoxylin-eosin (HE) staining

The results of HE staining showed that the medial muscle of the pulmonary artery was significantly thickened (74.67 ± 3.94% vs 19.93 ± 5.63%, P < 0.0001) and that the vascular lumen was reduced in the PAH group compared with the control group. Moreover, in the control group, 67.67 ± 5.25% of the arterioles were non-muscularized (NM) vessels, and 12.33 ± 4.92% were fully muscularized (FM) vessels. In contrast, partially muscularized vessels (PM) and FM vessels showed a greater proportion (57.67 ± 6.60% and 22.33 ± 2.49%) in MCT-PAH rats, while NM vessels occupied a lower proportion (20.00 ± 5.72%) (Figure 1C). The results of hemodynamic analysis and HE staining indicated that the rat model of PAH had been successfully established.

Methylation profile of lung tissue from rats with PAH

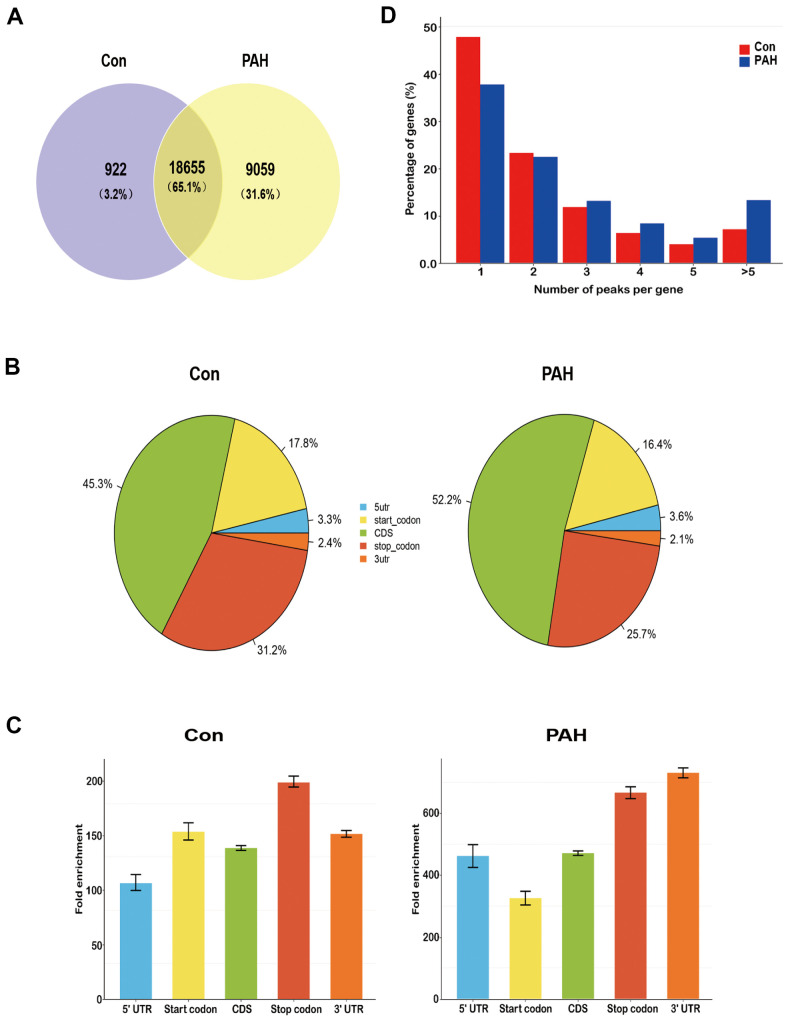

Lung tissues were collected from the two groups. MeRIP-seq analysis identified 922 nonoverlapping m6A sites in the control group, 9059 nonoverlapping m6A sites in the PAH group, and 18655 overlapping m6A sites between the two groups (Figure 2A). Nearly one-third of the m6A sites were found exclusively in the PAH group, suggesting that methylation modification plays an important role in PAH.

Figure 2.

Overview of N6-methyladenosine methylation within mRNAs in the control and MCT groups. (A) Venn diagram showing the overlap of m6A peaks within mRNAs in two groups. (B) Pie charts showing the percentage of m6A peaks in five non-overlapping segments of transcripts. Both the control group and the PAH group had the most abundant m6A peak in the coding sequence. (C) Distributions of fold enrichment of m6A peaks in five segments. The mean fold enrichment in the stop codon segments was the largest in the control group, while that value in 3' UTR was the largest in the PAH group. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. (D) Proportion of genes harboring different numbers of m6A peaks in two groups. Most genes have only one m6A peak.

The enrichment peaks were annotated to the nearest gene by bioinformatic analysis approaches, thus mapping the genome through the use of annotation information. We systematically classified these m6A sites into five transcript regions—5’UTRs, 3’UTRs, stop codons, start codons and coding sequences (CDs)—and found that the m6A sites were distributed mostly in CDs, stop codons, and start codons in both groups (Figure 2B). Notably, the mean fold enrichment was largest in the stop codon segments in the control group but the 3’UTR regions in the PAH group (Figure 2C), indicating that there are different methylation patterns between normal and disease. Meanwhile, the distribution pattern of methylated modifications was similar to previous studies [19, 20].

Notably, 47.7% of the m6A-modified coding genes in the control group and 36.2% of those in the PAH group contained only one m6A peak, consistent with a single m6A site or a cluster of adjacent m6A residues. The next highest percentage contained two m6A peaks, while a relatively small percentage contained three or more peaks (Figure 2D), which is agree with the trend of the proportions previously reported for the pig liver [21] and mouse heart [22].

Next, differentially methylated m6A sites (DMMSs) between the groups were identified by diffReps with the following default screening criteria: an FDR ≤ 0.0001 and a fold change ≥ 2. We selected 3298 DMMSs between the two groups. A total of 777 m6A sites exhibited decreased methylation, and 2521 exhibited increased methylation. On average, 23.6% and 76.4% of the m6A sites exhibited prominently decreased and increased methylation, respectively, in PAH lung tissues relative to control lung tissues (Table 1). Tables 2, 3 show the top ten genes with increased and decreased methylation.

Table 1. Total numbers of differentially methylated N6-methyladenosine peaks and associated gene.

| Item | Hypermethylated peak | Hypermethylated gene | Hypomethylated peak | Hypomethylated gene |

| mRNA | 2521 | 1261 | 777 | 568 |

Table 2. Top ten up-regulated genes.

| chrom | txStart | txEnd | GeneName | Foldchange |

| chr10 | 14521318 | 14521596 | Tpsab1 | 1643.7 |

| chr2 | 124777380 | 124777456 | Cpa3 | 852.7 |

| chr6 | 39260307 | 39260379 | LOC257642 | 528.3304473 |

| chr15 | 38492079 | 38492215 | Cma1 | 523.6 |

| chr1 | 235026074 | 235026209 | Ms4a2 | 454.3 |

| chr10 | 14519180 | 14519530 | Tpsab1 | 422.8 |

| chr15 | 38920068 | 38920123 | Mcpt2 | 399.3 |

| chr6 | 147108214 | 147108505 | AABR06046430.3 | 375.8 |

| chr6 | 148133714 | 148134006 | Ighg | 324.7 |

| chr15 | 38499889 | 38500287 | Mcpt1l1 | 317.4916885 |

Table 3. Top ten down-regulated genes.

| chrom | txStart | txEnd | GeneName | Foldchange |

| chr13 | 94156781 | 94157040 | Mpz | 144.4 |

| chr15 | 37540300 | 37540399 | Myh7 | 127.2 |

| chr8 | 118499941 | 118500097 | Als2cl | 111.7 |

| chr1 | 32944021 | 32944397 | Zfp72 | 110.5 |

| chr2 | 230629248 | 230629515 | Mybphl | 93.6 |

| chr17 | 67605795 | 67605900 | Ryr2 | 89.8 |

| chr17 | 17414465 | 17414480 | Iars | 88.2 |

| chr2 | 227847959 | 227848030 | Wdr77 | 87.9 |

| chr5 | 163485561 | 16485644 | Arhgef19 | 83.9 |

| chr2 | 228004667 | 228004738 | Wdr77 | 82.9 |

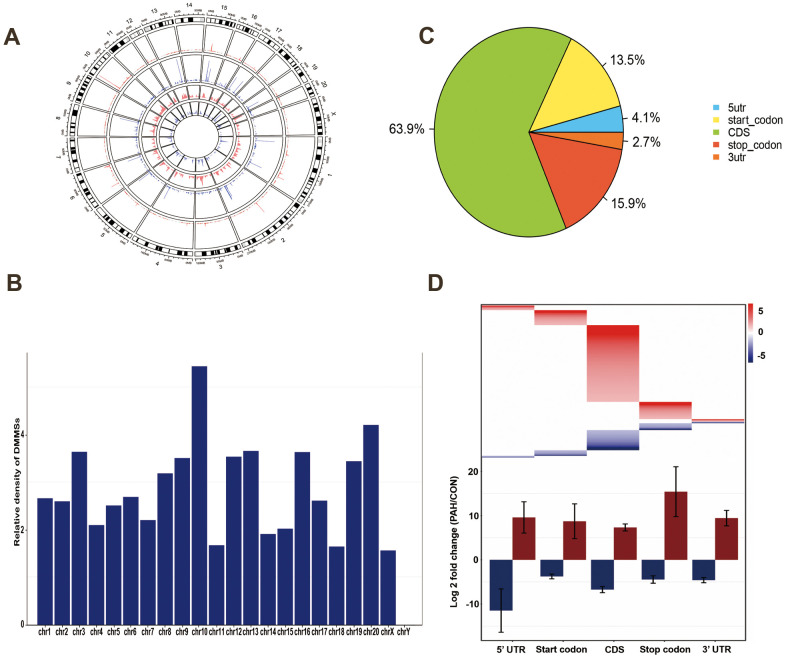

To assess their distribution profiles, all DMMSs within mRNAs were mapped to chromosomes (Figure 3A). The five chromosomes harboring the most DMMSs were chromosomes 1, 2, 4, 3 and 5. However, when the number of DMMSs harbored by a chromosome was normalized by the length of that chromosome, chromosomes 10, 20, 3, 13 and 16 were the five chromosomes with the highest relative densities of DMMSs (Figure 3B). We further investigated the regions with DMMSs in mRNA and found that most were located in CDs (Figure 3C). Moreover, most m6A sites in the stop codons with upregulated methylation showed the highest fold change, however, most m6A sites in the 5’UTRs with downregulated methylation showed the highest fold change (Figure 3D). Figure 3B, 3D suggesting the preferences of methylation and demethylation genome wide in the PAH group compare to the control group.

Figure 3.

Distribution of differentially methylated N6-methyladenosine sites. (A) Circos plots was used to plot the chromosomal distribution and genomic density of all DMM sites on genome. In the plot, red corresponds to up-methylated sites (gain of methylation) and blue corresponds to down-methylated sites (loss of methylation). Two histogram tracks were closer to the rat genome showed the chromosomal distribution of up-methylated sites and down-methylated sites, respectively. Two genomic density tracks were father from the rat genome showed the genomic density of up-methylated sites and down-methylated sites, respectively. (B) Relative occupancy of differentially methylated m6A sites in each chromosome normalized by length of the respective chromosome. (C) Pie chart showing the percentage of DMM peaks in five non-overlapping segments. Among them the largest proportion is the coding sequence. (D) Statistics of fold change of DMM peaks in five segments. The upper heatmap shows the distribution of the fold change, while the lower histogram shows the mean of the fold change. Error bars represent the standard error of the mean. (DMM: Differentially methylated N6-methyladenosine).

Differentially methylated RNAs are involved in important biological pathways

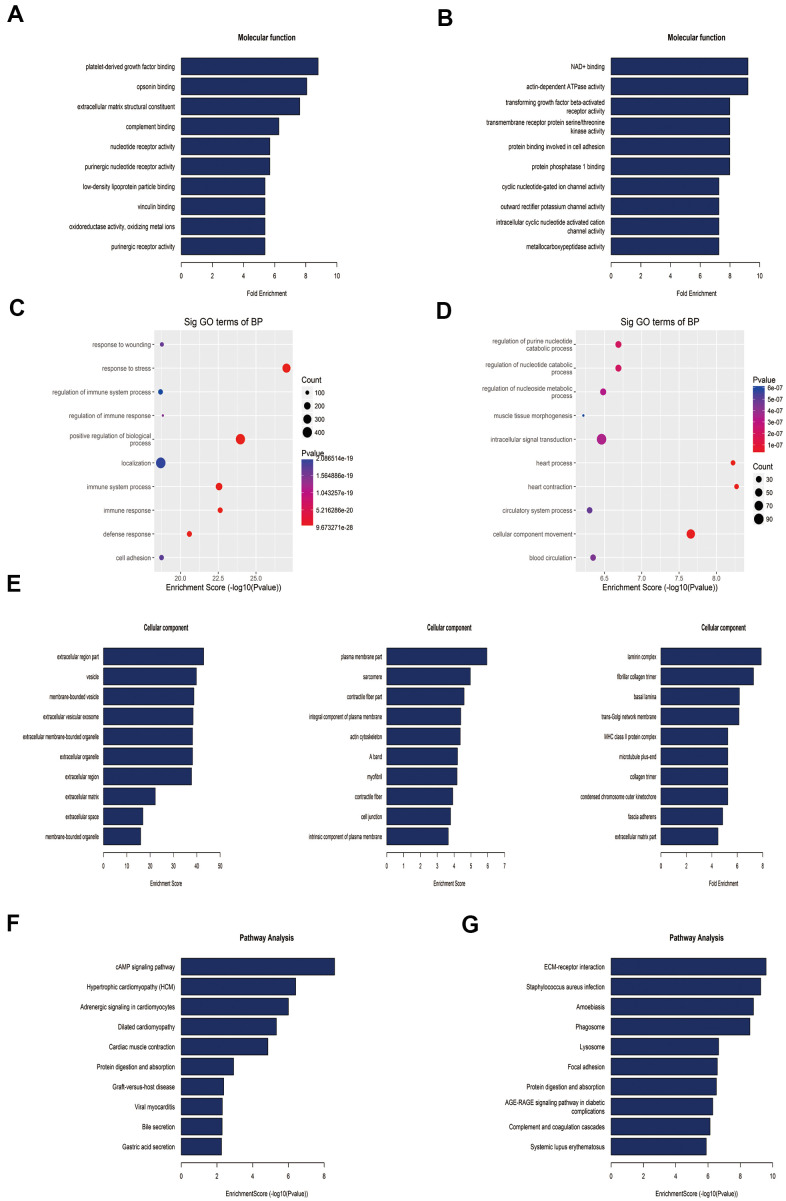

To reveal the functions of m6A in the lung tissues of rats with MCT-induced PAH, protein-coding genes containing DMMSs were selected for GO enrichment and KEGG pathway analyses. In the molecular function (MF) category, genes with up-methylated at m6A sites were significantly (p< 0.05) enriched in the platelet-derived growth factor (PDGF) binding, opsonin binding, extracellular matrix structural constituent, and complement binding categories (Figure 4A), while genes with down-methylated at m6A sites were highly enriched in the NAD+ binding, actin-dependent ATPase activity, transforming growth factor beta (TGF-β)-activated receptor activity, and transmembrane receptor protein serine/threonine kinase activity categories, among others (Figure 4B). Notably, studies have shown that the PDGF signaling pathway plays an important role in PAH. In the biological process (BP) category, immune-related processes were most enriched in rat lung tissues with upregulated methylation (Figure 4C), while heart-related processes, cellular component movement and regulation of purine nucleotide catabolic process were enriched in tissues with downregulated methylation (Figure 4D). In the cellular component category, genes containing DMMSs in lung tissues were enriched mainly in the extracellular region, plasma membrane, laminin complex and so on (Figure 4E).

Figure 4.

Gene ontology and Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes analyses of coding genes harboring differentially methylated N6-methyladenosine sites. (A) Bar plot showing the top ten enrichment scores of the molecular function for the up-methylated genes. (B) Bar plot showing the top ten enrichment scores of molecular functions of the down-methylated genes. (C) The top ten gene ontology terms of biological processes were significantly enriched for the up-methylated genes. (D) The top ten gene ontology terms of biological process significantly enriched for down-methylated genes. (E) In the cellular component category, the lung tissues of rats mainly contain genes with DMMSs. (F) Bar plot showing the top ten enrichment scores of the significant enrichment pathway for the up-methylated genes. (G) Bar plot showing the top ten enrichment scores of the significant enrichment pathways of the down-methylated genes.

Furthermore, genes with down-methylated m6A sites were found to be significantly (p< 0.05) involved in cardiovascular disease-related pathways, such as the cAMP signaling pathways, hypertrophic cardiomyopathy, adrenergic signaling in cardiomyocytes, and dilated cardiomyopathy (Figure 4F), while those with up-methylated m6A sites were involved in ECM-receptor interaction, staphylococcus aureus infection and so on (Figure 4G).

MeRIP-seq showed that m6A of COL1A1/2 were up-methylated, which were associated with PDGF binding and extracellular matrix structural constituent in molecular function by GO analysis (Table 4). KEGG Pathway analysis indicated that COL1A1/2 related to ECM-receptor interaction, PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and Platelet activation (Table 5). Meanwhile, mRNA m6A levels of HK3, GPI, LDHA and PKM were up-regulated, which were associated with glycolysis/gluconeogenesis pathway by KEGG Pathway analysis (Table 5). m6A of NF-κB was also up-methylated, which was connected with chemokine signaling pathway, T/B cell receptor signaling pathway and HIF-1 signaling pathway (Table 5). More importantly, ACVRL1, ENG, SMAD6 and SMAD9 had down-regulated methylation, which related to TGF-β signal pathway in molecular function, biological process or KEGG pathway (Table 6).

Table 4. Molecular function of upregulated m6A methylation.

| GO.ID | Term | Count | P-value | Genes |

| GO:0005201 | extracellular matrix structural constituent | 17 | 7.29608E-12 | COL1A1/ COL1A2/ELN/EMILIN1/ LAMC1/FN1/COL12A1/COL4A1/ LAMB1/COL4A4/COL4A2/COL4A3/ PXDN/FBN1/COL3A1/COL5A2/COL5A1 |

| GO:0048407 | platelet-derived growth factor binding | 6 | 1.97812E-05 | COL1A1/ COL1A2/COL4A1/ COL6A1/COL3A1/COL5A1 |

“Count” stands for the number of DE genes associated with the listed GO.ID.

Table 5. KEGG pathway analysis of genes with up-regulated methylation.

| Pathway ID | Definition | P-value | Count | Genes |

| rno04512 | ECM-receptor interaction | 2.54915E-10 | 83 | COL1A1/COL1A2/COL4A1/COL4A2/ COL4A3/COL6A1/COL6A2/COL6A3/ COL6A6/ CD44/ FN1/HMMR, etc. |

| rno04151 | PI3K-Akt signaling pathway | 0.000162593 | 332 | COL1A1/COL1A2/COL4A1/COL4A2/ COL4A3/COL6A1/COL6A2/COL6A3/ CCND3/CCNE1/ EFNA1/EIF4B, etc. |

| rno04611 | Platelet activation | 0.001133334 | 124 | COL1A1/COL1A2/COL3A1/F2RL3/ FERMT3/FGG/APBB1IP/ARHGEF1/ BTK/ FGG/ITGA2/ LCP2, etc. |

| rno04062 | Chemokine signaling pathway | 0.003441997 | 177 | NF-κB1/ARRB2/CCL9/CCR5/ CXCL12/CXCL2/CXCL9/GNB1/ GNG2/GNGT2/MAP2K1, etc. |

| rno00010 | Glycolysis/ gluconeogenesis | 0.02539777 | 70 | GPI/HK3/LDHA/ PKM/ PCK2/ DLD/ PGAM1/ADH1/ALDH9A1/BPGM |

| rno04662 | B cell receptor signaling pathway | 0.03293257 | 73 | NF-κB1/ BTK/CD72/DAPP1/INPP5D/ MALT1/MAP2K1 /PIK3AP1/PPP3R1/ PTPN6 |

| rno04066 | HIF-1 signaling pathway | 0.0422345 | 108 | NF-κB1/CYBB/HK3/HMOX1/ STAT3/ IFNGR1/IGF1/LDHA/MAP2K1/PFKFB3/ PRKCA/SERPINE1/TIMP1 |

| rno04660 | T cell receptor signaling pathway | 0.0422345 | 108 | NF-κB1/CBLB/CD4/CTLA4/ICOS/ LCP2/MALT1/MAP2K1/PAK1/PAK2/ PPP3R1/PTPN6/PTPRC |

“Count” stands for the count of the chosen background population genes' entities associated with the listed Pathway ID.

Table 6. Genes associated with down-regulation of differential methylated m6A sites.

| Gene Name | Foldchange | FDR | Pathway | GO_MF | GO_BP |

| ACVRL1 | 2.053666236 | 1.83832E-07 | - | TGF-β activated receptor activity | TGF-β receptor signaling pathway |

| SMAD6 | 2.811467105 | 2.48433E-05 | TGF-β signaling pathway | TGF-β receptor binding | TGF-β receptor signaling pathway |

| SMAD9 | 2.264780504 | 5.58215E-05 | TGF-β signaling pathway | - | TGF-β receptor signaling pathway |

| ENG | 5.169060443 | 1.91685E-06 | - | TGF-β activated receptor activity | TGF-β receptor signaling pathway |

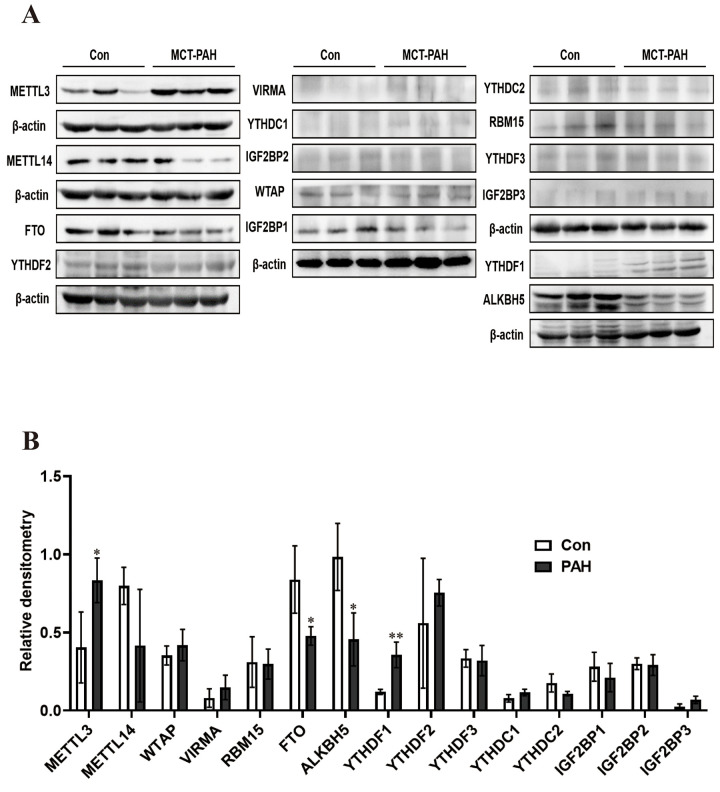

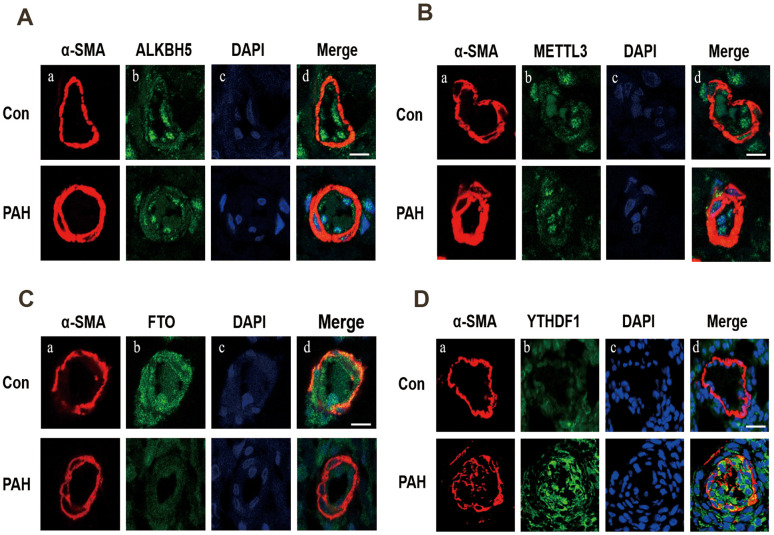

Expression of methylation-related enzymes in PAH lung tissue

Western blot analysis was used to verify the expression of methylation-related enzymes in PAH. In MCT-PAH group, the expression of FTO and ALKBH5 were decreased, the expression of YTHDF1 and METTL3 were increased, while differences in the expression levels of other methylation modification-related enzymes between the two groups were not statistically significant. Then four methylation-related enzymes, that exhibited obvious changes, were evaluated via immunofluorescence. The expression of FTO, ALKBH5, METTL3 and YTHDF1 were determined by quantifying overlap between the red and green signals, which revealed a faint fluorescence intensity for FTO and strong fluorescence intensity for YTHDF1 in small pulmonary arteries of MCT-PAH rats lung tissue, while no significant differences for ALKBH5 and METTL3 were found in the pulmonary vessels (Figures 5, 6).

Figure 5.

Western blot was used to detect the expression of methylated protein in rat lung tissue. (A) Western blot image of methylated modified enzyme. (B) Statistical graph of the expression of methylated modifying enzymes. *P < 0.05, **P < 0.01.

Figure 6.

Immunofluorescence was used to detect the expression of ALKBH5 (A), METTL3 (B), FTO (C) and YTHDF1 (D) in pulmonary vessels. (A) Vascular staining image (red), (B) objective protein staining image (green), (C) nuclei staining image (blue), (D) merged images.

DISCUSSION

m6A modification plays an indispensable role in the expression and critical dynamics of numerous genes [23] and has been extensively studied in various biological processes and diseases, such as multifunctional regulation and the self-renewal of embryonic stem cells [24], the growth and development of eukaryotes [25], tumors [26], and angiocardiopathy [27, 28]. In this study, we constructed a transcriptome-wide map of m6A-modified mRNAs in lung tissue from rats with MCT-induced PAH. We used MeRIP-seq to map the epitranscriptomic landscape of the lung tissue from PAH rats and then quantitatively compared transcriptome-wide changes between PAH and control groups. The m6A levels of most genes with DMMSs were increased in the lung tissue of rats with MCT-induced PAH. It is well accepted that m6A sites are mainly enriched in 3'UTR and near stop codons, however this study showed most of the m6A sites are located in CDs. The coding sequences in eukaryotes includes exons and introns. Genes containing exons can be transcribed into precursor RNA, and then the transcribed part of introns can be self-cleaved into mature mRNA, which is finally translated into proteins. m6A methylation is concentrated in the CDs in PAH, suggesting that the changes of signaling pathways and metabolic molecules may be closely related to the methylation changes in the coding region during the pathogenesis of PAH. These results indicate that m6A plays a key role in PAH.

We performed GO and KEGG analyses of coding genes harboring DMMSs, which showed that genes with increased methylation in the PAH group compared to the control group were enriched mainly in biological processes and pathways associated with the immune response. As plenty of research reported, a variety of inflammatory mediators and cytokines released by immune cells can bind the corresponding receptors on vascular endothelial cells, smooth muscle cells and fibroblasts, inducing vascular remodeling [29–32]. These results imply that m6A plays a significant role in the regulation of inflammation, suggesting that m6A modification may play an important role in PAH by regulating the inflammatory process.

In addition, the molecular functions of the up-regulated m6A methylation genes were related to PDGF binding and extracellular matrix structural constituents. KEGG pathway analysis demonstrated that genes with upregulated methylation participate in extracellular matrix (ECM)-receptor interaction, PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and platelet activation, which has been shown to play a major role in the pathogenesis of PAH [33–35]. Further GSEA result also showed the similar results (Supplementary Figure 1). Studies have shown that ECM remodeling occur early in the disease process, before the onset of the increase in the intimal and medial thickness and pulmonary artery pressure, suggesting that the ECM is a cause rather than a result of distal pulmonary vascular remodeling. Inhibition of ECM remodeling can prevent and reverse pulmonary arterial hypertension [33]. Interestingly, the PI3K/AKT pathway is a classical downstream signaling pathway in PAH, and its activation can promote the proliferation of pulmonary arterial smooth muscle. Previous studies by our research group confirmed that PDGF mediates the occurrence and development of PAH by activating the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/HIF-1α signaling pathway [36]. We also identified the COL1A1 (fold change=4.979) and COL1A2 (fold change=5.974) to be included in ECM-receptor interaction, PI3K/AKT signaling pathway and Platelet activation. The COL1A1 gene encodes the α1 chain of triple-helix type I collagen molecules, and type I collagen is a fibrillar collagen subtype. A few reports have shown that COL1A1 is a major cause of pulmonary artery stiffening and decreased right ventricular systolic function in hypoxia pulmonary hypertension [37–39]. GO analysis indicated that COL1A1/2 are significantly associated with PDGF binding. Considering the abovementioned observations, we hypothesize that the increased methylation of COL1A1 may activate the PI3K/AKT signaling pathway by increasing its binding to PDGF. These observations may show that m6A exerts an enormous effect on PDGF and the regulation of its downstream signaling pathway.

In addition, nuclear factor kappa B (NF-κB), which regulates the transcription and expression of multiple cytokines related to immunity and inflammation, exhibited significantly increased methylation in the T cell receptor signaling pathway, B cell receptor signaling pathway, chemokine signaling pathway and HIF-1 signaling pathway. Recent studies have shown that inflammation is closely related to vascular remodeling in PAH [40], suggesting that NF-κB may be involved in PAH by regulating the methylation of inflammatory factors.

Meanwhile, pathway analysis of the differential m6A genes also found that mRNA m6A levels of HK3, GPI, LDHA and PKM were up-regulated in the glycolysis/ gluconeogenesis pathway in PAH. A large number of studies have shown that m6A methylation can affect the proliferation and metastasis of tumor cells by regulating the process of glycolysis. A study showed that in leukemia cells, decreased FTO expression can increase the level of m6A methylation in mRNA of the key enzyme of glycolysis, while reading protein YTHDF2 reduces the translation and expression of LDHB, a key enzyme in glycolysis, by promoting mRNA degradation, thereby inhibiting aerobic glycolysis and cell proliferation [41, 42]. Moreover, studies have confirmed that aerobic glycolysis plays an important role in the proliferation of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, and inhibition of aerobic glycolysis can inhibit the proliferation and migration of pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells, and can partially reverse PAH of animal model [36]. These results suggest that m6A methylation may affect the protein translation or transcription of the key enzyme of glycolysis by upregulating the mRNA m6A level, thus participating in the development of PAH.

In addition, a small percentage of familial PAH cases are attributed to mutations in TGF-β family receptor members or related downstream signaling proteins (e.g., ACVRL1/ALK1, endoglin/ENG, and SMAD9) [43]. Studies have demonstrated that m6A can affect RNA stability, splicing, localization, and translation at the posttranscriptional level, thereby affecting gene expression [10]. Analysis of the MeRIP-seq results revealed that the genes harboring down-methylation m6A sites are primarily associated with TGF-β-activated receptor activity. More importantly, the analysis of differential methylated m6A sites in this study showed that multiple genes related to PAH, including ACVRL1, ENG, SMAD6 and SMAD9, had down-regulated methylation, and those genes have been found related to TGF-β signal pathway in molecular function, biological process or KEGG pathway. Previous studies have shown that TGF-β pathway plays an important role in PAH by regulating pulmonary vascular remodeling, variation of several TGF-β family receptor members, such as ACVRL1, ENG and SMAD9, are pathogenic genes of hereditary pulmonary arterial hypertension patients [6]. Combined with the above results, we speculated that m6A modification may participate in the development of PAH by regulating ACVRL1, ENG, SMAD6 and SMAD9.

Recent study confirmed that elevated m6A methylation and increased expression of YTHDF1 exist in pulmonary arterial hypertension, furthermore, YTHDF1 promotes pulmonary artery smooth muscle cells proliferation and PAH via enhancing MAGED1 translation [44]. However, there are only sporadic study concerned expression and function of methylation modifying enzymes in PAH [44, 45]. In this study, expression of methylation modifying enzyme in lung tissues of PAH rats was detected, results showed decreased expressions of FTO and ALKBH5 accompanied with increased expressions of METTL3 and YTHDF1, while there was no significant difference in expressions of other methylation modifying enzyme between PAH and control rats. Further immunofluorescence detection revealed that FTO and YTHDF1 were expressed in the small pulmonary arteries. Compared with the control group, the expression of FTO was decreased and the expression of YTHDF1 was increased in pulmonary vessels of MCT-PAH rats. FTO, a demethylase, plays an important role in DNA and RNA methylation and has been implicated in cardiac defects, including hypertrophic cardiomyopathy [46], arrhythmias [47], coronary heart disease [48] and heart failure [28]. Studies have shown that the m6A modification level is increased in FTO-knockdown cells and involved in various cell proliferation and migration processes [27]. As a reading protein, YTHDF1 was initially shown to bind methylated mRNA transcripts near the stop codon, which interacted with the translation initiation mechanism to improve the efficiency of the m6A translator and promote protein synthesis [12]. Based on the aforementioned results, we speculate changes of FTO and YTHDF1 expression may promote PAH through up-regulating the m6A methylation and facilitating mRNA m6A translation of multiple molecular function, biological process or KEGG pathway relative to PAH. These findings contribute to further understanding of the pathogenesis of PAH and provide new target for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension.

CONCLUSIONS

Our study revealed differential m6A methylome in the lung tissue of MCT-induced PAH rats and strong correlation between m6A methylation and PAH pathogenesis. Furthermore, downregulated FTO expression and upregulated YTHDF1 expression in small pulmonary arteries of MCT-induced PAH rats may play a leading role in mRNA m6A and involve in development of PAH through modulating inflammation, glycolysis, TGF-β family receptor members, ECM-receptor interaction and PDGF signal pathway. Thus, these findings provide a deeper understanding of epigenetics and innovative therapeutic target in PAH.

Limitations in this study still exist. First, we performed methylation sequencing analysis at the level of animal lung tissue, but further analysis of human lung tissue is needed if these findings are to be applied in the clinic. Additionally, the specific mechanism of FTO and YTHDF1 in PAH remains to be further verified.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Establishment and verification of a rat model of MCT-induced PAH

This study was approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hunan Children's Hospital and was conducted in compliance with the standards in the Guide for the Care and Use of Laboratory Animals. Sprague-Dawley rats (specific pathogen-free, male, 180–200 g, 6 weeks old, n=18) were obtained from Changsha Tianqin Biotechnology Company (China). The rats were randomized to the control (n=8) and PAH (n=10) group. Rats in the PAH group were intraperitoneally injected with MCT (60 mg·kg-1, Sigma, C2401), while rats in the control group were injected intraperitoneally with the same volume of saline [49]. All rats were housed on a 12 h light/dark cycle and given free access to food and water. After 4 weeks of feeding, the rats were anesthetized with 1% sodium pentobarbital (130 mg·kg-1) for echocardiography and right heart catheterization. Echocardiography was used to record the tricuspid annular plane systolic excursion (TAPSE), inner diameter of the right ventricle (RVID) and pulmonary artery blood flow acceleration time (PAAT). Images were acquired while the animals remained in the lateral decubitus position. After echocardiographic examination, the right external jugular vein was roughly dissected from the skin of the rat neck. One end of the catheter was passed through the external jugular vein into the right atrium and then into the right ventricle. The other end was connected to a pressure sensor that measured right ventricular systolic pressure (RVSP).

The rats were sacrificed by cervical dislocation after deep anesthesia. Then, heart tissues were harvested and separated. The weight ratio of the right ventricle to the left ventricle plus the ventricular septum [RV/(LV+S)] was used as an index of right ventricular hypertrophy. Lung tissues were excised and immediately frozen in liquid nitrogen or fixed in a 4% buffered paraformaldehyde solution for later RNA extraction and use in other experiments. All animal experimental protocols had been approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Hunan Children's Hospital.

Histological analysis

The lung tissues obtained from each group were placed in a 4% buffered paraformaldehyde solution overnight and were then dehydrated and embedded in paraffin. Then, all lung tissues were sliced into 5 μm-thick sections, fixed on a glass slide and baked to dryness. The staining procedures were performed according to the instructions. In brief, sections were sequentially soaked in xylene, an ethanol concentration gradient and hematoxylin and then sealed with resin. After the sections had dried, the pulmonary vascular morphology was observed and imaged under an optical microscope. Finally, the pulmonary small artery wall thickness and muscularization were quantitated. Medial wall thickness (MWT) is represented as follows: MWT% = (medial wall thickness × 2/external diameter) × 100.

RNA preparation

Four biological replicates were selected from each group, and sets of two replicates were combined into a single set. Then, total RNA was extracted from the tissues using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen Corporation, CA, USA) in accordance with the manufacturer’s instructions. A Ribo-Zero rRNA Removal Kit (Illumina, Inc., CA, USA) was used to reduce the ribosomal RNA content in the total RNA. Then, the RNA was chemically fragmented into fragments approximately 100 nucleotides in length using fragmentation buffer (Illumina, Inc., CA, USA).

RNA MeRIP-seq library construction and sequencing

MeRIP-seq was performed in accordance with a previously reported procedure [50] with slight modifications. In brief, MeRIP was performed with a GenSeq™ m6A RNA IP Kit (GenSeq Inc., China) following the manufacturer’s instructions. Both the input sample without immunoprecipitation and the m6A IP samples were used for RNA-seq library generation with the NEBNext® Ultra II Directional RNA Library Prep Kit (New England Biolabs, Inc., USA). The library quality was evaluated with a Bioanalyzer 2100 system (Agilent Technologies, Inc., USA). Library sequencing was performed on an Illumina HiSeq instrument with 150 bp paired-end reads.

Western blot analysis

Protein was extracted from the rat lung tissues with lysis buffer (RIPA: PMSF=100:1), and equal amounts of protein from each sample (20 μg or 40 μg) were separated by 8% or 10% sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis (SDS-PAGE) and transferred to polyvinylidene fluoride (PVDF) membranes. After incubation with high-affinity anti-YTHDF1 antibody (1:1000, Proteintech), anti-YTHDF2 antibody (1:5000, Proteintech), anti-METTL3 antibody (1:1000, Abcam), anti-METTL14 antibody (1:1000, Bioss Antibodies), anti-FTO antibody (1:1000, Abcam), anti-ALKBH5 antibody (1:1000, Abcam), anti-WTAP antibody (1:5000, Proteintech), anti-VIRMA antibody (1:1000, Abcam), anti-RBM15 antibody (1:1000, Proteintech), anti-YTHDF3 antibody (1:1000, Abclonal), anti-YTHDC1 antibody (1:1000, Proteintech), anti-YTHDC2 antibody (1:1000, Abclonal), anti-IGF2BP1 antibody (1:1000, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP2 antibody (1:1000, Abcam), anti-IGF2BP3 antibody (1:1000, Abcam), and anti-β-actin antibody (1:5000, Proteintech), the membranes were then incubated with peroxidase (HRP)-conjugated secondary antibody (1:5000, Proteintech). The chemiluminescent signals were detected with a chemiluminescent HRP substrate [51]. Densitometric analysis was conducted with ImageJ software.

Immunofluorescence staining

Paraffin sections were dewaxed and placed in a repair box filled with EDTA antigen repair buffer (pH 9.0) for antigen retrieval in a microwave oven. The primary antibody was added to the slices, incubated overnight at 4° C in a wet box, and washed 3 times. After the sections had dried slightly, a fluorescence-conjugated secondary antibody raised against the species used to generate the primary antibody was added until it covered the tissue in the ring and incubated at room temperature for 50 min. DAPI was used to counterstain nuclei, and after washing, the sections were sealed with an anti-fluorescence quenching tablet. The sections were observed by laser scanning confocal microscopy, and images were acquired [52].

Statistical analyses

In brief, paired-end reads were generated in an Illumina HiSeq 4000 sequencer and subjected to quality control by identifying bases with a quality score of Q30. Cutadapt was used to trim adaptor sequences and remove low-quality reads, after which HISAT2 was used to map clean reads to the reference genome (UCSC Rn5) [53]. Methylated sites on RNAs (m6A peaks) were identified by MACS (2) software [54]. Differentially methylated sites with a log2 (fold change) ≥1 and false discovery rate (FDR) ≤0.0001 were identified by diffReps [55]. The peaks identified by both software packages that overlapped with mRNA exons were determined and selected with scripts developed in-house. Gene ontology (GO) and pathway enrichment analyses of the differentially methylated protein-coding genes were performed.

GO and pathway enrichment analyses were performed with the Database for Annotation, Visualization and Integrated Discovery [56]. GO terms included three categories: cellular component (CC), molecular function (MF) and biological process (BP). The pathway enrichment analysis consisted of a functional analysis that mapped genes to Kyoto Encyclopedia of Genes and Genomes (KEGG) pathways. Fisher’s exact p-values were used to denotes the significance with which GO term or pathway enrichment correlated to the conditions. R package clusterProfiler was used for Gene Set Enrichment Analysis (GSEA), the average of all m6A sites fold change for each gene considered as the overall change level of the gene [57].

GraphPad Prism 8.0 software was used for analysis by single-factor analysis of variance (one-way ANOVA) for multigroup comparisons and t test for comparison between the two groups. Differences for which P < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. All experiments were independently repeated at least three times.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS: Yunhong Zeng, Ting Huang and Yunbin Xiao contributed to design the research; Yunhong Zeng, Ting Huang, Xun Wang and Yonghui Xie carried out the experiments; Yunhong Zeng, Ting Huang, Dan Wang, Zhenghui Xiao and Zhi Chen analyzed the test data; Yunhong Zeng and Ting Huang drafted the manuscript; Na Liu, Yunbin Xiao, Wanyun Zuo and Qiming Liu helped polish the manuscript.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST: The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

FUNDING: This work was funded by Hunan Provincial Health Commission Project (No. 20200483), Project of Hunan Provincial Research on Chinese Medicine (No. 201914), The Hunan Provincial Key Laboratory of Emergency Medicine for Children (No. 2018TP1028) and Hunan Provincial Natural Science Youth Foundation of China (No. 2019JJ50881).

REFERENCES

- 1.Weiss A, Neubauer MC, Yerabolu D, Kojonazarov B, Schlueter BC, Neubert L, Jonigk D, Baal N, Ruppert C, Dorfmuller P, Pullamsetti SS, Weissmann N, Ghofrani HA, et al. Targeting cyclin-dependent kinases for the treatment of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Commun. 2019; 10:2204. 10.1038/s41467-019-10135-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Thenappan T, Ormiston ML, Ryan JJ, Archer SL. Pulmonary arterial hypertension: pathogenesis and clinical management. BMJ. 2018; 360:j5492. 10.1136/bmj.j5492 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Quatredeniers M, Nakhleh MK, Dumas SJ, Courboulin A, Vinhas MC, Antigny F, Phan C, Guignabert C, Bendifallah I, Vocelle M, Fadel E, Dorfmüller P, Humbert M, Cohen-Kaminsky S. Functional interaction between PDGFβ and GluN2B-containing NMDA receptors in smooth muscle cell proliferation and migration in pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Lung Cell Mol Physiol. 2019; 316:L445–55. 10.1152/ajplung.00537.2017 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dai Z, Zhu MM, Peng Y, Machireddy N, Evans CE, Machado R, Zhang X, Zhao YY. Therapeutic Targeting of Vascular Remodeling and Right Heart Failure in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension with a HIF-2α Inhibitor. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 198:1423–34. 10.1164/rccm.201710-2079OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Dai Z, Zhao YY. BET in Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension: Exploration of BET Inhibitors to Reverse Vascular Remodeling. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2019; 200:806–08. 10.1164/rccm.201904-0877ED [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Galiè N, Humbert M, Vachiery JL, Gibbs S, Lang I, Torbicki A, Simonneau G, Peacock A, Vonk Noordegraaf A, Beghetti M, Ghofrani A, Gomez Sanchez MA, Hansmann G, et al. 2015 ESC/ERS Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Treatment of Pulmonary Hypertension. Rev Esp Cardiol (Engl Ed). 2016; 69:177. 10.1016/j.rec.2016.01.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luna RC, de Oliveira Y, Lisboa JV, Chaves TR, de Araújo TA, de Sousa EE, Miranda Neto M, Pirola L, Braga VA, de Brito Alves JL. Insights on the epigenetic mechanisms underlying pulmonary arterial hypertension. Braz J Med Biol Res. 2018; 51:e7437. 10.1590/1414-431X20187437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Potapov V, Fu X, Dai N, Corrêa IR Jr, Tanner NA, Ong JL. Base modifications affecting RNA polymerase and reverse transcriptase fidelity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:5753–63. 10.1093/nar/gky341 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zheng Y, Nie P, Peng D, He Z, Liu M, Xie Y, Miao Y, Zuo Z, Ren J. m6AVar: a database of functional variants involved in m6A modification. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:D139–45. 10.1093/nar/gkx895 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Wu Y, Xie L, Wang M, Xiong Q, Guo Y, Liang Y, Li J, Sheng R, Deng P, Wang Y, Zheng R, Jiang Y, Ye L, et al. Mettl3-mediated m6A RNA methylation regulates the fate of bone marrow mesenchymal stem cells and osteoporosis. Nat Commun. 2018; 9:4772. 10.1038/s41467-018-06898-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Su H, Wang G, Wu L, Ma X, Ying K, Zhang R. Transcriptome-wide map of m6A circRNAs identified in a rat model of hypoxia mediated pulmonary hypertension. BMC Genomics. 2020; 21:39. 10.1186/s12864-020-6462-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Yang Y, Hsu PJ, Chen YS, Yang YG. Dynamic transcriptomic m6A decoration: writers, erasers, readers and functions in RNA metabolism. Cell Res. 2018; 28:616–24. 10.1038/s41422-018-0040-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liu J, Yue Y, Han D, Wang X, Fu Y, Zhang L, Jia G, Yu M, Lu Z, Deng X, Dai Q, Chen W, He C. A METTL3-METTL14 complex mediates mammalian nuclear RNA N6-adenosine methylation. Nat Chem Biol. 2014; 10:93–95. 10.1038/nchembio.1432 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vu LP, Cheng Y, Kharas MG. The Biology of m6A RNA Methylation in Normal and Malignant Hematopoiesis. Cancer Discov. 2019; 9:25–33. 10.1158/2159-8290.CD-18-0959 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Aik W, Scotti JS, Choi H, Gong L, Demetriades M, Schofield CJ, McDonough MA. Structure of human RNA N6-methyladenine demethylase ALKBH5 provides insights into its mechanisms of nucleic acid recognition and demethylation. Nucleic Acids Res. 2014; 42:4741–54. 10.1093/nar/gku085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Li Z, Weng H, Su R, Weng X, Zuo Z, Li C, Huang H, Nachtergaele S, Dong L, Hu C, Qin X, Tang L, Wang Y, et al. FTO Plays an Oncogenic Role in Acute Myeloid Leukemia as a N6-Methyladenosine RNA Demethylase. Cancer Cell. 2017; 31:127–41. 10.1016/j.ccell.2016.11.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Meyer KD, Jaffrey SR. Rethinking m6A Readers, Writers, and Erasers. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2017; 33:319–42. 10.1146/annurev-cellbio-100616-060758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ivanova I, Much C, Di Giacomo M, Azzi C, Morgan M, Moreira PN, Monahan J, Carrieri C, Enright AJ, O’Carroll D. The RNA m6A Reader YTHDF2 Is Essential for the Post-transcriptional Regulation of the Maternal Transcriptome and Oocyte Competence. Mol Cell. 2017; 67:1059–67.e4. 10.1016/j.molcel.2017.08.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dominissini D, Moshitch-Moshkovitz S, Schwartz S, Salmon-Divon M, Ungar L, Osenberg S, Cesarkas K, Jacob-Hirsch J, Amariglio N, Kupiec M, Sorek R, Rechavi G. Topology of the human and mouse m6A RNA methylomes revealed by m6A-seq. Nature. 2012; 485:201–06. 10.1038/nature11112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Luo Z, Zhang Z, Tai L, Zhang L, Sun Z, Zhou L. Comprehensive analysis of differences of N6-methyladenosine RNA methylomes between high-fat-fed and normal mouse livers. Epigenomics. 2019; 11:1267–82. 10.2217/epi-2019-0009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.He S, Wang H, Liu R, He M, Che T, Jin L, Deng L, Tian S, Li Y, Lu H, Li X, Jiang Z, Li D, Li M. mRNA N6-methyladenosine methylation of postnatal liver development in pig. PLoS One. 2017; 12:e0173421. 10.1371/journal.pone.0173421 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Zhang B, Xu Y, Cui X, Jiang H, Luo W, Weng X, Wang Y, Zhao Y, Sun A, Ge J. Alteration of m6A RNA Methylation in Heart Failure With Preserved Ejection Fraction. Front Cardiovasc Med. 2021; 8:647806. 10.3389/fcvm.2021.647806 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mendel M, Chen KM, Homolka D, Gos P, Pandey RR, McCarthy AA, Pillai RS. Methylation of Structured RNA by the m6A Writer METTL16 Is Essential for Mouse Embryonic Development. Mol Cell. 2018; 71:986–1000.e11. 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Yang D, Qiao J, Wang G, Lan Y, Li G, Guo X, Xi J, Ye D, Zhu S, Chen W, Jia W, Leng Y, Wan X, Kang J. N6-Methyladenosine modification of lincRNA 1281 is critically required for mESC differentiation potential. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018; 46:3906–20. 10.1093/nar/gky130 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Frye M, Harada BT, Behm M, He C. RNA modifications modulate gene expression during development. Science. 2018; 361:1346–49. 10.1126/science.aau1646 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.He L, Li J, Wang X, Ying Y, Xie H, Yan H, Zheng X, Xie L. The dual role of N6-methyladenosine modification of RNAs is involved in human cancers. J Cell Mol Med. 2018; 22:4630–39. 10.1111/jcmm.13804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Mathiyalagan P, Adamiak M, Mayourian J, Sassi Y, Liang Y, Agarwal N, Jha D, Zhang S, Kohlbrenner E, Chepurko E, Chen J, Trivieri MG, Singh R, et al. FTO-Dependent N6-Methyladenosine Regulates Cardiac Function During Remodeling and Repair. Circulation. 2019; 139:518–32. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.033794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dorn LE, Lasman L, Chen J, Xu X, Hund TJ, Medvedovic M, Hanna JH, van Berlo JH, Accornero F. The N6-Methyladenosine mRNA Methylase METTL3 Controls Cardiac Homeostasis and Hypertrophy. Circulation. 2019; 139:533–45. 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.036146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guihaire J, Deuse T, Wang D, Spin JM, Blankenberg FG, Fadel E, Reichenspurner H, Schrepfer S. Immunomodulation Therapy Using Tolerogenic Macrophages in a Rodent Model of Pulmonary Hypertension. Stem Cells Dev. 2021; 30:515–25. 10.1089/scd.2021.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Xu Z, Ruan J, Pan L, Chen C. Candidate Genes Identified in Systemic Sclerosis-Related Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Were Associated with Immunity, Inflammation, and Cytokines. Cardiovasc Ther. 2021; 2021:6651009. 10.1155/2021/6651009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Kurakula K, Smolders V, Tura-Ceide O, Jukema JW, Quax PHA, Goumans MJ. Endothelial Dysfunction in Pulmonary Hypertension: Cause or Consequence? Biomedicines. 2021; 9:57. 10.3390/biomedicines9010057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tang C, Luo Y, Li S, Huang B, Xu S, Li L. Characteristics of inflammation process in monocrotaline-induced pulmonary arterial hypertension in rats. Biomed Pharmacother. 2021; 133:111081. 10.1016/j.biopha.2020.111081 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Thenappan T, Chan SY, Weir EK. Role of extracellular matrix in the pathogenesis of pulmonary arterial hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2018; 315:H1322–31. 10.1152/ajpheart.00136.2018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Tian H, Liu L, Wu Y, Wang R, Jiang Y, Hu R, Zhu L, Li L, Fang Y, Yang C, Ji L, Liu G, Dai A. Resistin-like molecule β acts as a mitogenic factor in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension via the Ca2+-dependent PI3K/Akt/mTOR and PKC/MAPK signaling pathways. Respir Res. 2021; 22:8. 10.1186/s12931-020-01598-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Vrigkou E, Tsantes AE, Kopterides P, Orfanos SE, Armaganidis A, Maratou E, Rapti E, Pappas A, Tsantes AG, Tsangaris I. Coagulation Profiles of Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension Patients, Assessed by Non-Conventional Hemostatic Tests and Markers of Platelet Activation and Endothelial Dysfunction. Diagnostics (Basel). 2020; 10:758. 10.3390/diagnostics10100758 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Xiao Y, Peng H, Hong C, Chen Z, Deng X, Wang A, Yang F, Yang L, Chen C, Qin X. PDGF Promotes the Warburg Effect in Pulmonary Arterial Smooth Muscle Cells via Activation of the PI3K/AKT/mTOR/HIF-1α Signaling Pathway. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017; 42:1603–13. 10.1159/000479401 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zhang B, Niu W, Dong HY, Liu ML, Luo Y, Li ZC. Hypoxia induces endothelial-mesenchymal transition in pulmonary vascular remodeling. Int J Mol Med. 2018; 42:270–78. 10.3892/ijmm.2018.3584 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Wang Z, Lakes RS, Eickhoff JC, Chesler NC. Effects of collagen deposition on passive and active mechanical properties of large pulmonary arteries in hypoxic pulmonary hypertension. Biomech Model Mechanobiol. 2013; 12:1115–25. 10.1007/s10237-012-0467-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ooi CY, Wang Z, Tabima DM, Eickhoff JC, Chesler NC. The role of collagen in extralobar pulmonary artery stiffening in response to hypoxia-induced pulmonary hypertension. Am J Physiol Heart Circ Physiol. 2010; 299:H1823–31. 10.1152/ajpheart.00493.2009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Berghausen EM, Feik L, Zierden M, Vantler M, Rosenkranz S. Key inflammatory pathways underlying vascular remodeling in pulmonary hypertension. Herz. 2019; 44:130–37. 10.1007/s00059-019-4795-6 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Qing Y, Dong L, Gao L, Li C, Li Y, Han L, Prince E, Tan B, Deng X, Wetzel C, Shen C, Gao M, Chen Z, et al. R-2-hydroxyglutarate attenuates aerobic glycolysis in leukemia by targeting the FTO/m6A/PFKP/LDHB axis. Mol Cell. 2021; 81:922–39.e9. 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.12.026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huang T, Liu Z, Zheng Y, Feng T, Gao Q, Zeng W. YTHDF2 promotes spermagonial adhesion through modulating MMPs decay via m6A/mRNA pathway. Cell Death Dis. 2020; 11:37. 10.1038/s41419-020-2235-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Southgate L, Machado RD, Gräf S, Morrell NW. Molecular genetic framework underlying pulmonary arterial hypertension. Nat Rev Cardiol. 2020; 17:85–95. 10.1038/s41569-019-0242-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Hu L, Wang J, Huang H, Yu Y, Ding J, Yu Y, Li K, Wei D, Ye Q, Wang F, Shen B, Chen J, Fulton DJ, Chen F. YTHDF1 Regulates Pulmonary Hypertension through Translational Control of MAGED1. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2021; 203:1158–72. 10.1164/rccm.202009-3419OC [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Qin Y, Qiao Y, Li L, Luo E, Wang D, Yao Y, Tang C, Yan G. The m6A methyltransferase METTL3 promotes hypoxic pulmonary arterial hypertension. Life Sci. 2021; 274:119366. 10.1016/j.lfs.2021.119366 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Boissel S, Reish O, Proulx K, Kawagoe-Takaki H, Sedgwick B, Yeo GS, Meyre D, Golzio C, Molinari F, Kadhom N, Etchevers HC, Saudek V, Farooqi IS, et al. Loss-of-function mutation in the dioxygenase-encoding FTO gene causes severe growth retardation and multiple malformations. Am J Hum Genet. 2009; 85:106–11. 10.1016/j.ajhg.2009.06.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Carnevali L, Graiani G, Rossi S, Al Banchaabouchi M, Macchi E, Quaini F, Rosenthal N, Sgoifo A. Signs of cardiac autonomic imbalance and proarrhythmic remodeling in FTO deficient mice. PLoS One. 2014; 9:e95499. 10.1371/journal.pone.0095499 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Gustavsson J, Mehlig K, Leander K, Lissner L, Björck L, Rosengren A, Nyberg F. FTO genotype, physical activity, and coronary heart disease risk in Swedish men and women. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2014; 7:171–77. 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.111.000007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Huang Y, Liu YW, Pan HZ, Zhang XL, Li J, Xiang L, Meng J, Wang PH, Yang J, Jing ZC, Zhang H. Transthoracic Pulmonary Artery Denervation for Pulmonary Arterial Hypertension. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2019; 39:704–18. 10.1161/ATVBAHA.118.311992 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Meyer KD, Saletore Y, Zumbo P, Elemento O, Mason CE, Jaffrey SR. Comprehensive analysis of mRNA methylation reveals enrichment in 3' UTRs and near stop codons. Cell. 2012; 149:1635–46. 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Han J, Wang JZ, Yang X, Yu H, Zhou R, Lu HC, Yuan WB, Lu JC, Zhou ZJ, Lu Q, Wei JF, Yang H. METTL3 promote tumor proliferation of bladder cancer by accelerating pri-miR221/222 maturation in m6A-dependent manner. Mol Cancer. 2019; 18:110. 10.1186/s12943-019-1036-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Dai Z, Zhu MM, Peng Y, Jin H, Machireddy N, Qian Z, Zhang X, Zhao YY. Endothelial and Smooth Muscle Cell Interaction via FoxM1 Signaling Mediates Vascular Remodeling and Pulmonary Hypertension. Am J Respir Crit Care Med. 2018; 198:788–802. 10.1164/rccm.201709-1835OC [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Kim D, Langmead B, Salzberg SL. HISAT: a fast spliced aligner with low memory requirements. Nat Methods. 2015; 12:357–60. 10.1038/nmeth.3317 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Zhang Y, Liu T, Meyer CA, Eeckhoute J, Johnson DS, Bernstein BE, Nusbaum C, Myers RM, Brown M, Li W, Liu XS. Model-based analysis of ChIP-Seq (MACS). Genome Biol. 2008; 9:R137. 10.1186/gb-2008-9-9-r137 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Shen L, Shao NY, Liu X, Maze I, Feng J, Nestler EJ. diffReps: detecting differential chromatin modification sites from ChIP-seq data with biological replicates. PLoS One. 2013; 8:e65598. 10.1371/journal.pone.0065598 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Huang DW, Sherman BT, Lempicki RA. Systematic and integrative analysis of large gene lists using DAVID bioinformatics resources. Nat Protoc. 2009; 4:44–57. 10.1038/nprot.2008.211 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Yu G, Wang LG, Han Y, He QY. clusterProfiler: an R package for comparing biological themes among gene clusters. OMICS. 2012; 16:284–87. 10.1089/omi.2011.0118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.