“I am a survivor. Bring it on.”

—From my patient, a survivor of 4 cancers, cardiac arrest, and heart failure in response to the question, “What first comes to mind when hearing cancer and heart disease?”

The resiliency and strength of my patients inspire and motivate me every day. They suffer from the burden of both cancer and cardiovascular disease, but they are able to effectively manage their health and navigate the multiple complexities of their diseases. They work full time and strive to live life each day to its fullest, as mothers, fathers, sisters, brothers, daughters, sons, wives, husbands, friends, and colleagues. But they also feel anxious, overwhelmed, and sad. They cry, and I cry with them.

Our Patients

Caring for the needs of our patients is at the core of what we—as medical professionals—do every day. But how can we do this in the best possible way: How can we remain firmly patient-centered, and partner with our patients to provide them with evidence-based, personalized care?

We Need to Listen

Fundamentally, we need to take the time, and be afforded the time, to empathically listen to our patients. As medical professionals, we are acutely aware of the many needs and demands on our time and the pressures of meeting productivity and performance metrics within our practice. We are acutely aware of the many strengths, but also the many burdens of the electronic health record system, which can provide ready access to data, but also impose overwhelming stress and intrusion on the human connection (1). We need to give ourselves the time to listen intently, without distraction, to what our patients are trying to tell us (2). We need our health care system to allow us the time establish a patient-centered approach to medical care. In cardio-oncology, in particular, the medical problems our patients face can be extraordinarily complex, requiring detailed discussions and a careful navigation of concerns across multiple disciplines.

We Need Support

To practice at the “highest level of certification,” we need greater support to provide coordinated care to our patients (2). The multidisciplinary nature of cardio-oncology necessitates a team-based approach to care, where silos of practice cannot exist. We need institutional support to build an effective infrastructure that meets the needs of individual providers and patients, to collaboratively develop innovative solutions to overcome the challenges that we face in everyday practice, which include lack of access to coordinated care and excessive administrative burdens (1). We need an environment that educates, communicates, and values team-based care, so that an individual can use his or her strengths and skill sets to most effectively contribute to the common goal of providing the best possible care to our patients (2).

We Need Evidence

We need to practice evidence-based and interpersonal medicine. Cardio-oncology is a growing field, and we need science to inform our best practices. We need to develop guidelines based on rigorously executed studies, the available data, and graded evidence. We need to practice based on scientific evidence, rather than intuition (3,4). Moreover, we need to understand how to best apply guidelines, using interpersonal medicine that addresses the behavioral and social factors that are barriers to our patients’ acceptance of our recommendations (3).

We Need to Educate and Advocate

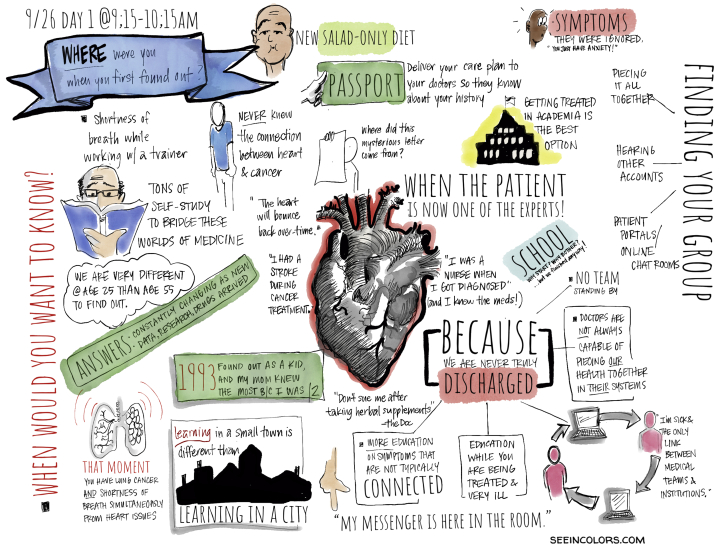

The American College of Cardiology convened a patient forum in September 2019, “At a Crossroads: Surviving Cancer, Taking Your Care to Heart” (Figure 1), where 20 patients were invited to share their experiences, in an effort to better understand the unique challenges confronting cancer patients with cardiovascular disease. The overarching message was that patients wanted a physician who would listen to them and advocate for them (5). Patients wanted more knowledge and to be better educated and informed, so they could also advocate for themselves. To help address these needs, the National Cancer Institute–funded Eastern Cooperative Group–American College of Radiology Imaging Network and the American College of Cardiology have collaborated to develop patient education modules specific to cardio-oncology (6).

Figure 1.

Artist's Sketch Depicting the Discussions at the ACC Patient Forum “At a Crossroads: Surviving Cancer, Taking Care of Your Heart”

To close, a recent mixed-methods study published in JAMA identified 5 practices with the potential to positively affect the patient-physician relationship (7). Although there is a need for a greater understanding of the impact these measures can have on clinical outcomes, they provide specific guiding principles for us to live by, as we reinvigorate the patient-physician relationship:

Prepare with intention: Review the patient’s history. Focus your attention before you walk into the room.

Listen intently and completely: Thoughtfully position your body. Listen without interruption.

Agree on what matters most: Determine your patient’s concerns and priorities.

Connect with your patient’s story: Empathize. Acknowledge your patient’s efforts.

Explore emotional cues: Be attentive, elicit, reflect and validate your patient’s cues.

References

- 1.Lieu T.A., Altschuler A., Weiner J.Z. Primary care physicians’ experiences with and strategies for managing electronic messages. JAMA Netw Open. 2019;2 doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.18287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Noseworthy J. The future of care—preserving the patient-physician relationship. N Engl J Med. 2019;381:2265–2269. doi: 10.1056/NEJMsr1912662. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cheng S., Lee T.H. Beyond evidence-based medicine. N Engl J Med. 2018;379:1983–1985. doi: 10.1056/NEJMp1806984. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Minasian L.M., Dimond E., Davis M. The evolving design of NIH-funded cardio-oncology studies to address cancer treatment-related cardiovascular toxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol CardioOnc. 2019;1:105–113. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2019.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Strong S.R. Decades after diagnosis: the unrecognized trauma of surviving. J Am Coll Cardiol CardioOnc. 2020;3:149–151. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2020.02.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.American College of Cardiology. CardioSmart. Available at: www.cardiosmart.org. Accessed February 5, 2020.

- 7.Zullman D.M., Haverfield M.C., Shaw J.G. Practices to foster physician presence and connection with patients in the clinical encounter. JAMA. 2020;323:70–81. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.19003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]