Abstract

The health of migrant children is a pressing issue. While most African migration takes place within Africa, a significant number of African migrants travel to outside of the continent. This article reports findings from a scoping review on the health of African immigrant children from sub-Saharan Africa now living outside of Africa. A systematic search for studies published between 2000 and 2019 resulted in only 20 studies reporting on the health of children up to 18 years of age migrating from sub-Saharan Africa. Data from these articles were thematically analyzed, highlighting concerns related to the children's nutrition status (n = 8), mental health (n = 7), and physical health (n = 5). Study participants were primarily from Somali and Ethiopia, and most studies were conducted in Australia or Israel. The review highlights several gaps related to the scope, range, and nature of evidence on the health of African immigrant children living outside of Africa. In particular, most focus on children's nutritional and mental health, but pay little attention to other health concerns this specific population may encounter or to the benefits associated with effective responses.

Keywords: Scoping review, African immigrant children, Sub-Saharan Africa

Highlights

-

•

A systematic search for studies published between 2000 and 2019 resulted in only 20 studies reporting on the health of children up to 18 years of age migrating from sub-Saharan Africa.

-

•

Data highlight concerns related to the children's nutrition status (n = 8), mental health (n = 7), and physical health (n = 5).

-

•

Most focus on children's nutritional and mental health, but pay little attention to other health concerns.

-

•

Gaps related to the scope, range, and nature of evidence on the health of this population.

Introduction

Twelve percent of international migrants worldwide are children aged 18 years and under, with the total number reaching 33 million in 2019 (UNICEF 2020). The critical interconnection between migration to health is widely acknowledged throughout the United Nations’ Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) (United Nations 2016). A growing body of evidence demonstrates both adverse physical and mental health outcomes associated with migration as well as the benefits associated with effective responses or structural economic conditions that allow families to operate in the best interest of their members (Castanenda et al., 2015; Haagsman et al., 2015; Dito et al., 2016; Mazzucato et al., 2017; International Organization for Migration 2018). The 2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development recognises the contribution of migration to sustainable development. Eleven of the 17 SDGs address indicators that are relevant to migration or mobility (United Nations 2016). Advancing understanding of the relationship between migration and health is an important step towards the identification of effective interventions that address the health-related needs of migrant groups considered especially vulnerable, such as children and young people. Yet, to date the health of child migrants has received relatively little attention. A recent systematic review examined the available evidence on child migrant health, documenting the paucity of research on the subject (Thompson et al., 2018).

Within this context, it is also important to acknowledge geographic, demographic, and political variations of migration. Low- and middle-income countries host 86% of forcibly displaced populations (World Health Organization 2017). It is widely accepted that immigrant children from different geographic regions present diverse challenges, including those related to health. African immigrants are a notably growing population. According to a report by the International Organization for Migration (International Organization for Migration 2018), migration in Africa involves roughly equal numbers of migrants moving within or off of the continent. While international migration within the African region has increased since 2000, the most significant growth by far has been migration from Africa to other regions. In 2015, most African-born migrants living outside the continent were residing in Europe (9 million), Asia (4 million), and North America (2 million) (International Organization for Migration 2018). Despite emerging literature on African migration, there is a paucity of research on the health experiences of African migrant children.

In response to this identified gap, a scoping review examining the evidence of the health experiences of African migrant children was deemed appropriate, in particular with respect to those migrating from sub-Saharan Africa. Health is defined as a “state of complete physical, mental and social well-being and not merely the absence of disease or infirmity” (World Health Organization 2020). Given the significance of migration as an important social determinant of health and the importance of child health outcomes to redressing health inequalities, there is a critical and timely need to examine the evidence base on the health of child migrants, particularly those from sub-Saharan Africa. Without such a knowledge synthesis, significant gaps remain in our understanding of the impacts of migration with respect to public health policies and practice related to the health and well-being of African child migrants.

This paper focuses on African immigrant children. We define immigrants as “a person who moves into a country other than that of his or her nationality or usual residence, so that the country of destination effectively becomes his or her new country of usual residence” (International Organization for Migration 2020). Refugees are excluded from our analysis as they face unique health challenges, such as post-traumatic stress, due to unique pre-migration experiences that may further complicate their health status (Shawyer et al., 2017). Studies have already shed light on the experience of African refugees in destination countries (Adedoyin et al., 2016; Gladden, 2012; Tempany, 2009). However, we found no review focused on African immigrants, especially children, who are not refugees. A sole focus on immigrants who are not refugees will enable an in-depth perspective to be gained on the health of African immigrant children.

Material and methods

Focus

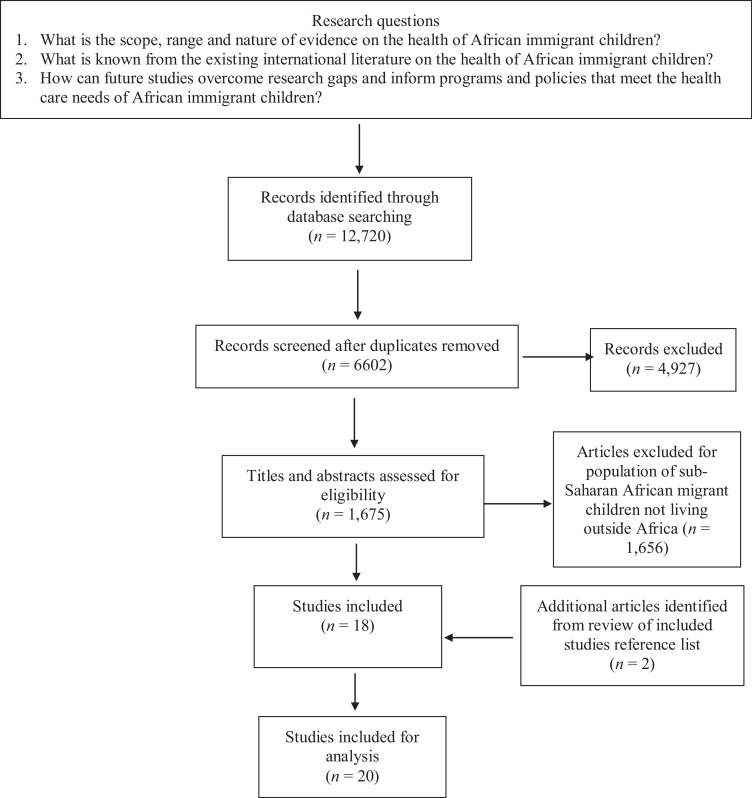

During the first half of 2019, we conducted a scoping review on the health of African children. A scoping review is a method often used to map out and characterize the extent, range, and nature of research activity in a given area as well as identify research gaps in the existing literature. The review was guided by Arksey and O'Malley's (Arksey and O'Malley, 2005) framework, which outlines five stages for conducting a scoping review (see Fig. 1). Stage 1 involved developing research questions appropriate for a scoping review. This project focused on summarizing the breadth of evidence related to the health of migrant and displaced African children. The research questions were as follows:

-

1

What is the scope, range, and nature of evidence on the health of African immigrant children?

-

2

What is known from the existing international literature on the health of African immigrant children?

-

3

How can future studies overcome research gaps and inform programs and policies that meet the health care needs of African immigrant children?

Fig. 1.

Flowchart (Moher et al., 2009).

Search strategy

Stage 2 involved identifying the relevant studies. Published research articles were identified in the proposed project through searches of electronic databases, reference lists of articles reviewed, and searches of libraries of relevant organisations. The following databases were searched on January 21, 2019 by a health science librarian: Ovid PsycInfo; Cochrane Library; Ovid MEDLINE(R) and Epub Ahead of Print, In-Process & Other Non-Indexed Citations and Daily; Embase; Ovid Global Health; EBSCO CINAHL Plus with Full-text; EBSCO SocIndex; EBSCO Child Development & Adolescent Studies; ProQuest Sociological Abstracts; and ProQuest Dissertations & Theses Global. We used a combination of search terms that represents child and immigrant. The above two groups of search terms were combined with the word Africa and the names of all African countries. A total of 12,720 records were initially retrieved from the above databases with 6602 records remaining after duplicates were removed by a subject librarian. These articles were then exported into Covidence, an online website that works in collaboration with Cochrane to enhance the selection and completion of systematic reviews.

Article selection

Stage 3 involved article selection. Two research assistants independently reviewed the titles and abstracts of the identified records in Covidence. However, as significant resources were required to review 6602 full articles, the research team carefully considered and then applied the following inclusion criteria after significant discussion: research studies published between 2000 and 2019, reporting on the health of children up to 18 years of age, where the child and parents were migrants, and with migration status clearly stated. Systematic reviews, literature reviews, and conference abstracts and proceedings were excluded. Articles focused on the mother's health, on the experiences of parents but without information on the health of the child, on African Americans where no information is provided on whether or not they are migrants, on African populations mixed with non-African populations (as it would be difficult to retrieve findings on Africans), and on Caribbean migrants were also excluded. At this stage, only titles and abstracts were used for article selection and conflicts between reviewers were resolved by consensus.

These revised inclusion criteria resulted in 1675 articles for full review. An initial classification of these articles highlighted that the records comprised studies on African immigrants and refugees outside Africa, as well as refugees and internally displaced people in Africa. It was decided to consider these groups independently, with the present publication focusing on studies reporting on African immigrant children from sub-Saharan Africa living outside of Africa. Disagreements between the two reviewers were resolved by consensus. The focus on sub-Saharan Africa was driven by discussions about how this context is quite different from North Africa where countries are culturally more similar to Middle Eastern countries; the exceptions to this were Somalia, Sudan, and Djibouti, with studies focused on immigrant children from these countries included in the review. While only titles and abstracts were reviewed to apply the first set of inclusion criteria, titles, abstracts and full texts were reviewed to apply the second set of inclusion criteria. Twenty articles were ultimately included in data charting and data extraction.

Data extraction

Stage 4 involved data charting and data extraction of the following information: author name, title, year of publication, research questions or objectives, theoretical framework, methodology (sampling, sample size, age of child, data source, e.g., parent vs. child vs. health professional), clinical area of focus (e.g., mental health, nutrition, cardiovascular health, etc.), period of data collection, country of origin or region, destination country or region, summary of findings, and summary of implications. See data extraction table (Table 1) for details.

Table 1.

Data extraction from included articles.

| Authors | Article Title | Year | Research focus | Theoretical Framework | Approach | Data collection Method | Sampling | Sample size | Age of participant data | Data source | Clinical area focus | Period of data collection | Country of origin / (Destination country) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

East African immigrant children in Australia have poor immunization coverage | 2011 | immunization status of recently arrived east african children and adolescents in australia | None reported | Prospective | Questionnaire; blood tests | Convenience | 136 | Mean 8.7 years | Parents | Vaccination | 2002–2002 | Somalia, Sudan, Kenya, Ethiopia & Eritrea (Australia) |

|

A comparison of levels and predictors of emotional problems among preadolescent Ethiopians in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Toronto, Canada. | 2012 | Level and predictors of emotional problems among preadolescent Ethiopians living in immigrant families in Canada | Segmental Assimilation and Immigration Stress | Qualitative | Interviews | Probability | 64 | 11–13 years | Parents and children | Mental health | Not specified | Ethiopia (Canada) |

|

Dental care issues for African immigrant families of preschoolers | 2008 | Dental health issues for African immigrant families of preschoolers living in the United States | Narrative inquiry and Ethnographic impressionism | Mixed methods | Survey and interviews | Purposive | 125 parents | 3–5 years | Parents | Dental health | Not specified | 13 African countries −72.8% from West Africa (USA) |

|

Culture and dental health among African immigrant school-aged children in the United States | 2007 | African immigrant parents’ views on dental decay and dental insurance for their children | None reported | Cross-sectional | Survey | Not specified | 400 parents601 children |

Not specified | Parents | Dental health | 2005 | Not specified (USA) |

|

Assessment of the nutritional status of Sudanese primary school pupils in Riyadh City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia | 2014 | Nutritional status of primary school Sudanese pupils | None reported | Cross-sectional | Interviews | Simple random | 600 | 6–12 years | Children | Nutrition | Not specified | Sudan (Saudi Arabia) |

|

It was like walking without knowing where I was going: A qualitative study of Autism in a UK Somali migrant community | 2017 | Health, education and social care services for families affected by autism | None reported | Community-based participatory | Interviews | Purposive | 15 | 4–13 years | Parents | Mental health | Not specified | Somalia (UK) |

|

Breastfeeding among Somali mothers living in Norway: Attitudes, practices and challenges | 2016 | Infant feeding practices among Somali-born mothers in Norway | None reported | Qualitative | Interviews; focus-groups | Snowball | 21 mothers 22 (focus groups. |

6, 12 and 24 months | Mothers | Nutrition | 2012–2015 | Somalia (Norway) |

|

Ethiopian parents' perception of their children's health: A focus group study of immigrants to Israel | 2001 | Ethiopian immigrants' perception of the health of their children | None reported | Qualitative | Focus groups | Convenience | Not specified | Younger than 3 years | Parents | General health | Not specified | Ethiopia (Israel) |

|

Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and offerings to Somali children: The FAV-S pilot study | 2014 | Parent-centered intervention to increase fruit and vegetable servings and consumption among Somali children living in the United States | None reported | Quantitative | Surveys | Snowball | 25 | Mean 43.6 years |

Parents | Nutrition | Not specified | Somali, Ethiopia & Eritrea (USA) |

|

Made in America: Perspectives on friendship in West African immigrant families | 2016 | African immigrant parents’ perceptions regarding the negative influences on their children | None reported | Qualitative | Interviews; focus groups | Purposive | 56 (adults=31, teenagers=25) | adults (32–83 years) teenagers (12–21 years) |

Parents and teenagers | Mental health | Not specified. | Sierra Leone & Liberia (USA) |

|

Reducing physical inactivity and promoting active living: from the voices of East African immigrant adolescent girls | 2011 | Experiences with and beliefs about physical activity of East African adolescent female participants | Ecological systems | Qualitative | Interviews; focus groups | Purposive | 19 First generation (n = 8) second generation (n = 11) |

12–18 years | Children | Sport, exercise | Not specified | Somali and Ethiopia (USA) |

|

Relationship between body mass index and family functioning, family communication, family type and parenting style among African migrant parents and children in Victoria, Australia: a parent-child dyad study. | 2016 | Difference between children and parental perception of family functioning, family communication, family type and parenting styles and its relationship with body mass index | Family communication patterns | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire; interviews | Snowball | 284 parents 283 children | 12–17 years | Parents and children | Nutrition | Not specified | Not specified (Australia) |

|

Contributions of self-esteem and gender to the adaptation of immigrant youth from Ethiopia: Differences between two mass immigrations | 2002 | Effects of gender, self-esteem, and sense of belonging on four measures of adaptation | None reported | Cross-sectional | Questionnaire | Not specified | 150 | 13–19 years | Teenagers | Mental health | Not specified | Ethiopia (Israel) |

|

Enablers and barriers to dietary practices contributing to bone health among early adolescent Somali girls living in Minnesota | 2012 | Dietary factors that contribute to bone health among first generation Somali girls | None reported | Qualitative | Focus groups | Not specified | 39 | 11–14 years | Teenagers | Nutrition | 2008 | Somalia (USA) |

|

Readiness to use psychoactive substances among second-generation adolescent immigrants and perceptions of parental immigration-related trauma | 2017 | Relationship between parental immigration-related trauma and second-generation adolescent substance abuse | Transgenerational trauma transference | Quantitative | Questionnaire | Purposive | 510 | 12–18 years | High school students | Mental health | Not specified | Ethiopia (Israel) |

|

Navigating among worlds: The experience of Ethiopian adolescents in Israel | 2007 | Experience of immigrant Jewish Ethiopian youth in Israel and its impact on identity formation | None reported | Qualitative | Interviews | Purposive | 13 | 14–17 years | High school students | Mental health | Not specified | Ethiopia (Israel) |

|

Maintenance of traditional cultural orientation is associated with lower rates of obesity and sedentary behaviours among African migrant children to Australia | 2008 | Association between acculturation and obesity and its risk factors among African migrant children in Australia | None reported | Quantitative | Questionnaire | Snowball | 337 | 3–12 years | Parents and anthropometric measurements | Nutrition | 2001 - 2002 | Sub-Saharan Africa (Australia) |

|

Parenting, family functioning and lifestyle in a new culture: the case of African migrants in Melbourne,Victoria, Australia | 2011 | Parenting styles among African migrants in Australia, | None reported | Qualitative | Focus group | Purposive | 85 | 13–52 years | Parents and children | Nutrition, Parenting health practices | Not specified | Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia (Australia) |

|

Screening for intestinal parasites in recently arrived children from East Africa | 2003 | Prevalence and risk factors for intestinal parasite carriage among children recently arrived from East African countries | None reported | Quantitative | Questionnaire, clinical assessment, lab analysis | Purposive | 135 | 0–17 years | Not stated | Nutrition | Not specified | Sudan, Somalia, Ethiopia, Eritrea, Kenya (Australia) |

|

Suicidal ideation and alcohol use among Ethiopian adolescents in Israel | 2012 | Relationship between ethnic identity (Israeli and Ethiopian) and parental support with suicide ideation and alcohol use | None reported | Quantitative | Questionnaire | Purposive | 200 | 15–18 years | Children | Mental health | Not specified | Ethiopia (Israel) |

Data analysis and synthesis

Stage 5 involved collating, summarizing, and reporting the results using thematic analysis and numerical summary. Two research assistants read the articles and manually coded themes that emerged across the included studies. Inter-coder reliability reached >95%. Three main themes related to the children's nutrition status (n = 8), mental health (n = 7), and physical health (n = 5).

Results and discussion

The 20 studies included in this review were mostly cross-sectional in nature, with 10 using a quantitative approach, nine using a qualitative approach, and one using mixed methods. Only five reported a theoretical framework that guided the research, most employed a non-probabilistic sampling method (n = 16), and the sample size ranged from eight to 601 participants. The authors of the studies relied on parents, children, and clinical assessments for data collection. The participants were primarily from Somalia and Ethiopia and their places of destination were predominantly Israel (n = 5), Australia (n = 5), and the USA (n = 6). The studies reported on three broad themes: children's nutrition status, including weight issues, dietary factors, and breastfeeding practices (n = 8); mental health, including developmental disorders (n = 7); and physical health, including dental health, vaccination, and exercise (n = 5).

These results confirmed that a scoping review was the most appropriate approach to answer the research question. Scoping reviews are best designed for when a body of literature has not previously been comprehensively reviewed, or exhibits a large, complex, or heterogeneous nature not amenable to a more precise systematic review. However, the results also highlighted the weaknesses of this approach. Scoping reviews do not allow researchers to formally assess the quality of evidence and often gather information from a wide range of study designs and methods, posing a risk for bias from different sources. We offer the discussion below aware of this weakness.

Nutritional health

Eight studies reported on nutritional health on topics that included weight issues, dietary factors, and breastfeeding practices. Five of the studies were quantitative and three qualitative. Renzaho, Swinburn, and Burns (Renzaho et al., 2008) examined the relationship between acculturation and obesity among African immigrant children in Australia. Their sample consisted of 337 children between the ages of 3 and 12 years. They collected anthropometric data from the children and used questionnaires to collect information on their diet and physical activity from their parents. The authors used a bi-dimensional model of strength of affiliation with African and Australian cultures to divide the sample into four cultural orientations: traditional (African), assimilated (Australian), integrated (both), and marginalised (neither). They found that more than 25% of the participants were either overweight or obese. Youth who maintained a traditional African lifestyle were at the lowest risk of being overweight and obese. The youth who exhibited greater levels of assimilation in Australian society were at a higher risk of obesity as they had acquired eating habits and sedentary lifestyle habits that facilitated weight gain. They reported that 32% of “integrated” children were obese, compared to 9.8% for children who followed a traditional lifestyle. Overall, “integrated” and “marginalized” children exhibited a higher body mass index (BMI) than “traditional” children. The authors concluded that the further African children moved from traditional lifestyles, the less physically active they became and the fattier foods they ate, which resulted in obesity. In addition, keeping some aspects of traditional culture was linked with healthy nutritional choices, healthier weight, and protection against chronic illness.

Cyril, Halliday, Green, and Renzaho (Cyril et al., 2016) examined the difference between child and parental perception of family functioning, family communication, family type, and parenting styles, and these variables’ relationship with BMI. Using a quantitative approach and a cross-sectional design, the authors collected data via questionnaires and anthropometric measures from parents and their children (n = 283). The results showed a number of the children were either underweight (n = 29), overweight (n = 68), or obese (n = 27). Furthermore, a positive relationship was found between poor family functioning and child BMI (β = 1.73, 2.94; p<0.001). Renzaho, Green, Mellor, and Swinburn (Renzaho et al., 2011) reported on the parenting styles among African migrants now living in Australia and assessed how intergenerational issues related to parenting in a new culture impact family functioning and the modification of lifestyles. To accomplish their objective, the authors employed a qualitative approach through focus groups to collect data from 85 parents and children. Overall, the findings of these studies revealed that African migrant children were less active and ate more fast food, thus contributing to obesity problems.

In contrast to the studies conducted in Australia, the quantitative Saudi Arabian study of Khayri, Muneer, Ahmed, Osman and Babiker (Khayri et al., 2014) aimed to assess the nutritional status of primary school Sudanese pupils. These authors examined correlates and found that 31% of participants were underweight and only 6.75% were overweight. In addition, the participants' average daily intake of calories and fibre was significantly lower than the dietary requirement intake (DRI) (1, 397.89 vs. 2000 kcal, p<0.01). However, the intake of protein (59.25 g), carbohydrates (186.0 g), unsaturated fat (206.6 g), some vitamins, and iron were significantly higher than the DRI (p = <0.01).

In an attempt to increase healthy eating habits in African immigrant children, Hearst, Kehm, Sherman, and Lechner (Hearst et al., 2014) designed an intervention to determine the feasibility, acceptability, and impact of a parent-centered intervention to increase fruit and vegetable servings and consumption among Somali children living in the United States. The authors implemented a quantitative pilot study with 25 Somali mothers of children between the ages of three and 10 years recruited through a non-probabilistic technique (snowballing). The intervention was tailored to the Somali dietary practices and was implemented in four sessions over a six-week period. The authors found the intervention to be feasible and well accepted by the participants. Mothers reported providing their children significantly more frequent servings of fruits and vegetables at dinner, with the weekly median servings pre- and post-intervention reported as follows: (13 vs. 59, p = <0.001), lunch (22 vs. 62, p = 0.01), and snack time (12 vs. 45, p = 0.01). In addition, parents reported an increase in daily vegetable and fruit consumption from pre-test to post-test in their own diet (0.3 vs. 2, p = 0.01) as well as in their children's diet (0.3 vs. 2, p = 0.001).

Benbenek and Garwick (Benbenek and Garwick, 2012) explored dietary factors that contribute to bone health among first-generation Somali girls in the United States and aimed to determine the social and cultural contexts that shape these health behaviours. The authors used a descriptive qualitative design to gather data from 39 Somali girls aged 11–14 years using focus groups. The results from this study highlighted four factors contributing to the consumption of calcium and vitamin d-rich foods among Somali girls: cultural and family tradition, environment, developmental stage, and acculturation.

Wandel et al.’s (Wandel et al., 2016) qualitative research explored infant feeding practices among Somali-born mothers in Norway, and the ways in which they navigate among different information sources. Through in-depth interviews and five focus groups with 43 mothers of children between the ages of 6 and 24 months, the authors discovered mothers introduced water and infant formula at early stages of the children's development, thus interfering with exclusive breastfeeding and influencing the nutritional health of the infants. The authors explained these results were due to the mothers not being familiar with the principles of exclusive breastfeeding.

Rice et al. (Rice et al., 2003) described the prevalence of and risk factors for intestinal parasite carriage among children recently arrived in Australia from African countries. They used a quantitative approach to gather data through a questionnaire and clinical assessment (i.e., stool specimen, blood tests) from 137 African migrant children aged 1 to 17.5 years. The authors found that parasites were identified in 50% of the samples. Of these, 18% of the children hosted a parasite that could be pathogenic; however, no child manifested signs and symptoms. In addition, 11 and 2% of children tested positive for Strongyloides and Schistosoma, respectively. Children with intestinal parasites were older than those without (median 9.8 vs. 7.4 years, p = 0.002).

Based on the large variation in indicators analysed, and the diversity of origin and destination contexts, the results of these studies do not lend themselves to summative conclusions related to nutritional health in this population.

Mental health

Seven studies reported on the theme of mental health. Four were conducted among Ethiopian immigrants in Israel (Aviad-Wilchek et al., 2017; Goldblatt and Rosenblum, 2007; Itzhaky and Levy, 2002; Walsh et al., 2012) and three respectively focused on immigrants in Canada (Beiser et al., 2012), the United States (Akinsulure-Smith et al., 2016), and the United Kingdom (Fox et al., 2017). Four utilised quantitative methodology and three used qualitative methodology. Three studies were mainly concerned with the impact that immigration had on youth and their struggles with identity formation and becoming integrated in the host society (Goldblatt and Rosenblum, 2007; Walsh et al., 2012; Beiser et al., 2012). Ethiopian families struggled with various issues including racism and changing roles, where children were assuming some of their parents’ roles because they were able to learn the host country's language faster (Goldblatt and Rosenblum, 2007). Avid-Wilcheck et al. (Aviad-Wilchek et al., 2017) found that the children of parents with high post-traumatic stress from the immigration process were more likely to use drugs but that second-generation Ethiopian children in Israel had low likelihood of drug use. Walsh et al.’s (Walsh et al., 2012) study highlighted the importance of parents to youth mental health; youth with high levels of parental support were less likely to use drugs and engage in suicide ideation. Some studies emphasised the importance of youth having a strong positive sense of identity and high self-esteem, which gave them the resilience to withstand the stressors of immigration (Itzhaky and Levy, 2002; Walsh et al., 2012).

Fox et al. (Fox et al., 2017) explored the needs of Somali parents in the United Kingdom with children affected by autism, and how health, education, and social care services can support them. For the families in this study, cultural attitudes towards mental illness, combined with the lack of vocabulary to define and explain autism in Somali culture, made the understanding and acceptance of their child's diagnosis particularly difficult and caused them to delay seeking help. Even for those who sought help, limited English proficiency skills and lack of understanding of the health system posed significant challenges. The findings support evidence that the perceived link to mental illness or “insanity” mean that families with autistic children experience shame and social isolation from their fellow Somalis.

A key part of immigrant youth integration in their host country is forming friendships outside of their family network. The study by Akinsulure-Smith et al. (Akinsulure-Smith et al., 2016) conducted among West Africans in the United States showed that parents’ aversion to their children's friends and their attempts to influence their children's peer group choices was a source of tension in the parent–child relationship. However, parents’ concerns did not prevent youth from maintaining friendships with their peer group.

Physical health

Four studies reporting on the theme of physical health, relating to dental health, vaccination, and exercise. Obeng's research conducted in the United States of America (Obeng, 2007; Obeng, 2008) showed the cultural beliefs around oral health, African parents’ perceptions about dental decay, and financial barriers resulted in a significant proportion of African immigrant children not receiving professional dental care. Her 2008 study (Obeng, 2008) focused on pre-school children of African parents and showed 48% of those children had never had their teeth checked by a dental professional. Many of the parents felt other issues were more important than oral health, such as life-threatening diseases or their financial obligations to family members in their countries of origin.

In recent years, vaccination has been at the center of discussion for health providers, healthcare policymakers, and society in general. However, only one study considered immunization coverage and focused on East African children living in Australia (Paxton et al., 2011). The authors relied on a quantitative approach using a questionnaire requesting information from parents on their children's vaccination status, the Mantoux test, and serology samples (i.e., hepatitis B, measles) collected from the children. Participants were recruited using a non-probabilistic sampling method (convenience) to obtain a final sample size of 136 children. The average age of participants was 8.7 years. According to the results from the questionnaire, 97% of the participants had either an incomplete or unclear immunization status. The results from the serology tests showed a low number of children with serological immunity against hepatitis B (33%), diphtheria (45%), and tetanus (61%) but a larger number with immunity to measles (90%), rubella (77%), and tetanus (61%). Based on these results, the authors concluded that East African children migrating to Australia are likely to have an incomplete vaccination scheme. In addition, reports about the children's vaccination coverage by the parents does not predict serological immunity for these diseases.

Thul and LaVoi's (Thul and LaVoi, 2011) study, carried out in the United States, explored the experiences with, and beliefs about, physical activity of East African adolescent female participants and suggestions for promoting active living. The authors of this study used Ecological Systems Theory to guide this research. They employed a phenomenological approach through an exploratory qualitative design. The researchers recruited first generation (n = 8) and second generation (n = 11) immigrant children from Somali and Ethiopia using a purposive sampling method, resulting in a total sample size of 19 children aged 12 to 18 years. Semi-structured interviews and a focus group were conducted to collect data from the children. The results of this study showed participants wanted to become physically active, but experienced numerous barriers (i.e., personal, social, environmental, cultural) to active living, even when they were able to identify culturally appropriate physical activities.

Yaphe, Schein, and Naveh (Yaphe et al., 2001) described the importance of pre-arrival cultural understanding of health and the communal culture. They conducted a study with Ethiopian immigrants in Israel to understand perceptions of their children's health. They found Ethiopian parents carried an array of information regarding illnesses and treatments with them to Israel. The study highlighted the fact that health decisions were taken communally and the important role that elders and traditional healers play in decisions regarding treatment of illnesses.

Conclusions

Despite the large number (6.5 million) of African children living abroad as immigrants (38) only 20 articles published between 2000 and 2019 report on the health of these children. A review of these articles highlights several gaps related to the scope, range, and nature of evidence on the health of African immigrant children living outside of Africa. Our review of these studies indicates they mostly focus on children's nutritional and mental health, but pay little attention to other health concerns this specific population may encounter or to the benefits associated with effective responses, such as encouraged by Castanenda et al. (Castanenda et al., 2015) and the International Organization for Migration (International Organization for Migration 2018). Even though the identified studies report robust findings on aspects of nutrition, mental health, and physical health, more research is needed on all of these topics as well as on the effectiveness of interventions. In addition, study participants were primarily from Somalia and Ethiopia, with a limited focus on children from other African countries. This is important as the Pew Research Center (Pew Research Center 2018) indicated eight of the fastest growing migrant populations worldwide come from the sub-Saharan African region.

Most of the studies were conducted in Australia and Israel, even though a range of countries are known to host immigrants from the African continent; most African-born nationals living outside the region reside in Europe, Asia, and North America (International Organization for Migration 2018). This demonstrates a need to focus research on other destination countries to better understand the experiences of African immigrant youth. The lack of European studies was surprising and we can only speculate on the reasons for this shortfall. One factor might be that in some European countries, such as in France, it has not possible since the early 2000s to ask for ‘ethnic origin’ in surveys. This means it is not possible to isolate specific African groups in large-scale survey work. Another factor may relate to the fact that some commissioned studies by ministries and health services remain in the form of reports that are not easily accessible via database searches and may have escaped our review.

Mental health was an issue commonly explored in the studies in this scoping review. However, given that most of the studies were descriptive in nature and only a single study used an intervention design, we suggest the need for more quantitative, qualitative, and intervention research in this field. Qualitative studies could help unpack and provide in-depth explanations and understanding of the association and trends identified in the quantitative studies. Furthermore, designing, implementing, and evaluating health interventions are necessary to improve the mental health outcomes of African immigrant children. A wide range of interventions have been found useful for managing mental health issues with other populations, such as music therapy to reduce anxiety and depression among cancer patients (Jasemi et al., 2016), dance therapy to reduce stress in family caregivers (Fernández-Sánchez et al., 2019), and expressive writing to alleviate depressive symptoms (Reinhold et al., 2018). Such intervention studies could further be culturally adapted to meet the needs of African immigrant children.

The correlates of nutritional status of African immigrant children should be further explored. It is also important that researchers and policy analysts are cognizant of child rearing norms that are practiced in migrant-origin countries. More studies are needed on the role that the cultures of both the country of origin and destination play in mediating African immigrant children's access to various health services. To achieve this, we suggest consulting key stakeholders such as religious or community leaders, but also speaking with some of the less visible members of migrant communities, such as women and the children/youth themselves. Stakeholders can provide direction for research and policy help design culturally appropriate policies and health interventions for African immigrant children.

The implications for policy and practice are extensive. Scholars around the globe are increasingly encouraging that both physical and mental health advancement activities and initiatives be cognizant of, if not grounded in, local health practices; some scholars also call for the integration of local medical heath practices into the formal health care delivery system and more attention to the informal sector in health care delivery (Gureje et al., 2015; Egharevba et al., 2015). Western medical culture often disregards or dismisses local health practices in its considerations of wellness of populations (Pesek et al., 2006). Maintaining aspects of lifestyle as practiced in origin countries will promote healthy habits and address immigrants’ predispositions for mental health challenges and physical health concerns such as obesity and other chronic diseases. The results of studies across regions and populations of African immigrant children could assist policymakers in making informed decisions regarding programs to reduce inequities within the migration context and suggest changes to health policies on immunization coverage to benefit recently arrived African immigrant children.

Declarations

Ethics approval: As this scoping review did not involve human participants, the need for approval was waived.

Availability of data and materials: This scoping review is not based on primary data. The data supporting the findings are listed in the articles cited in Table 1.

Competing interests: None of the authors have any competing interests to declare.

Funding: The project was partially funded by a World Universities Network grant. The purpose of the grant supported networking; the funding body had no role in the design or implementation of the study.

Authors’ contributions: The authors all had an equal contribution in the design and development of the study and the subsequent preparation of the manuscript.

Declaration of Competing Interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- UNICEF, 2020. Child migration. https://data.unicef.org/topic/child-migration-and-displacement/migration/, (accessed 26 November 2020).

- United Nations, 2016. Transforming our world: the 2030 agenda for sustainable development. https://sustainabledevelopment.un.org/post2015/transformingourworld, (accessed 26 November 2020).

- Castanenda H., Holmes S.M., Madrigal D.S., Young M.E., Beyeler N., Quesada J. Immigration as a social determinant of health. Annu. Rev. Public Health. 2015;18(36):375–392. doi: 10.1146/annurev-publhealth-032013-182419. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haagsman K., Mazzucato V., Dito B. Transnational families and the subjective well-being of migrant parents: angolan and Nigerian parents in The Netherlands. Ethn. Racial Stud. 2015;38(15):2652–2671. doi: 10.1080/01419870.2015.1037783. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dito B., Mazzucato V., Schans D. The effects of transnational parenting on the subjective health and well-being of Ghanaian migrants in The Netherlands. Popul. Space Place. 2016;23(3):1–15. doi: 10.1002/psp.2006. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mazzucato V., Dito B., Grassi M., Vivet J. Transnational parenting and the well-being of Angolan migrant parents in Europe. Glob. Netw. 2017;17(1):89–110. doi: 10.1111/glob.12132. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration . 2018. World Migration Report 2018.https://www.iom.int/wmr/world-migration-report-2018 (accessed 26 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Thompson J., Fairbrother H., Curtis P. Hidden voices: reflections on the health experiences of children who migrate. Eur. J. Public Health. 2018;28 doi: 10.1093/eurpub/cky048.049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2017. Refugee and Migrant Health.http://www.who.int/migrants/en/ (accessed 26 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization . 2020. What is the WHO Definition of Health?https://www.who.int/about/who-we-are/frequently-asked-questions (accessed 26 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- International Organization for Migration, 2020. Key migration terms. https://www.iom.int/key-migration-terms, (accessed 26 November 2020).

- Shawyer F., Enticott J.C., Block A.A., Cheng I.H., Meadows G.N. The mental health status of refugees and asylum seekers attending a refugee health clinic including comparisons with a matched sample of Australian-born residents. BMC Psychiatry. 2017;17(1):76. doi: 10.1186/s12888-017-1239-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Adedoyin A.C., Bobbie C., Griffin M., Adedoyin O.O., Ahmad M., Nobles C., Neeland K. Religious coping strategies among traumatized African refugees in the United States: a systematic review. Soc. Work Christianity. 2016;43(1):95. [Google Scholar]

- Gladden J. The coping skills of East African refugees: a literature review. Refug. Surv. Q. 2012;31(3):177–196. [Google Scholar]

- Tempany M. What research tells us about the mental health and psychosocial wellbeing of Sudanese refugees: a literature review. Transcult. Psychiatry. 2009;46(2):300–315. doi: 10.1177/1363461509105820. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey H., O'Malley L. Scoping studies: towards a methodological framework. Int. J. Soc. Res. Methodol. 2005;8(1):19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Renzaho A.M., Swinburn B., Burns C. Maintenance of traditional cultural orientation is associated with lower rates of obesity and sedentary behaviours among African migrant children to Australia. Int. J. Obes. 2008;32(4):594–600. doi: 10.1038/ijo.2008.2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyril S., Halliday J., Green J., Renzaho A.M.N. Relationship between body mass index and family functioning, family communication, family type and parenting style among African migrant parents and children in Victoria, Australia: a parent-child dyad study. BMC. 2016;16(1):1–10. doi: 10.1186/s12889-016-3394-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Renzaho A.M., Green J., Mellor D., Swinburn B. Parenting, family functioning and lifestyle in a new culture: the case of African migrants in Melbourne, Victoria, Australia. Child Fam. Soc. Work. 2011;16(2):228–240. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2206.2010.00736.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Khayri H.O., Muneer S.E., Ahmed S.B., Osman M.A., Babiker E.E. Assessment of the nutritional status of Sudanese primary school pupils in Riyadh City, Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. J. Immigr. Minor. Health. 2014;18(1):28–33. doi: 10.1007/s10903-014-0135-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hearst M.O., Kehm R., Sherman S., Lechner K. Increasing fruit and vegetable consumption and offerings to Somali children: the FAV-S pilot study. J. Prim. Care Community Health. 2014;5(2):139–143. doi: 10.1177/2150131913513269. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benbenek M.M., Garwick A.W. Enablers and barriers to dietary practices contributing to bone health among early adolescent Somali girls living in Minnesota. J. Spec. Pediatr. Nurs. 2012;17(3):205–214. doi: 10.1111/j.1744-6155.2012.00334.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wandel M., Terragni L., Nguyen C., Lyngstad J., Amundsen M., de Paoli M. Breastfeeding among Somali mothers living in Norway: attitudes, practices and challenge. Women Birth. 2016;29(6):487–493. doi: 10.1016/j.wombi.2016.04.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rice J.E., Skull S.A., Pearce C., Mulholland N., Davie G., Carapetis J.R. Screening for intestinal parasites in recently arrived children from East Africa. J. Paediatr. Child Health. 2003;39(6):456–459. doi: 10.1046/j.1440-1754.2003.00188.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aviad-Wilchek Y., Levy I., Ben-David S. Readiness to use psychoactive substances among second-generation adolescent immigrants and perceptions of parental immigration-related trauma. Subst. Use Misuse. 2017;2(12):1646–1655. doi: 10.1080/10826084.2017.1298618. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goldblatt H., Rosenblum S. Navigating among worlds: the experience of Ethiopian adolescents in Israel. J. Adolesc. Res. 2007;22(6):585–611. doi: 10.1177/0743558407303165. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Itzhaky H., Levy D. Contributions of self-esteem and gender to the adaptation of immigrant youth from Ethiopia: differences between two mass immigrations. J. Soc. Work Res. Eval. 2002;3(3):33–46. [Google Scholar]

- Walsh S.D., Edelstein A., Vota D. Suicidal ideation and alcohol use among Ethiopian adolescents in Israel: the relationship with ethnic identity and parental support. Eur. Psychol. 2012;17(2):131–142. doi: 10.1027/1016-9040/a000115. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Beiser M., Taa B., Fenta-Wube H., Baheretibeb Y., Pain C., Araya M. A comparison of levels and predictors of emotional problems among preadolescent Ethiopians in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, and Toronto, Canada. Transcult. Psychiatry. 2012;49(5):651–677. doi: 10.1177/1363461512457155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Akinsulure-Smith A., Mirpuri S., Chu T., Keatley E., Rasmussen A. Made in America: perspectives on friendship in West African immigrant families. J. Child Fam. Stud. 2016;25(9):2765–2777. doi: 10.1007/s10826-016-0431-8. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fox F., Aabe N., Turner K., Redwood S., Rai D. It was like walking without knowing where I was going: a qualitative study of autism in a UK Somali migrant community. J. Autism Dev. Disord. 2017;47(2):305–315. doi: 10.1007/s10803-016-2952-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obeng C. Culture and dental health among African immigrant school-aged children in the United States. Health Educ. 2007;107(4):343–350. doi: 10.1108/09654280710759250. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Obeng C. Dental care issues for African immigrant families of preschooler. Early Child. Res. Pract. 2008;10(2) https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ848833 [Google Scholar]

- Paxton G.A., Rice J., Davie G., Carapetis J., Skull S. East African immigrant children in Australia have poor immunization coverage. J. Pediatr. Child Health. 2011;47(12):888–892. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1754.2011.02099.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thul C.M., LaVoi N.M. Reducing physical inactivity and promoting active living: from the voices of East African immigrant adolescent girls. Qual. Res. Sport Exerc. Health. 2011;3(2):211–237. doi: 10.1080/2159676X.2011.572177. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Yaphe J., Schein M., Naveh P. Ethiopian parents’ perception of their children's health: a focus group study of immigrants to Israel. Isr. Med. Assoc. J. 2001;3(12):932–936. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.UNICEF, 2019. 13.5 Million Children Now Uprooted in Africa—Including those Displaced by Conflict, Poverty and Climate Change. https://www.unicef.org/press-releases/135-million-children-now-uprooted-africa-including-those-displaced-conflict-poverty, (accessed 26 November 2020).

- Pew Research Center . 2018. International Migration from Sub-Saharan Africa has Grown Dramatically Since 2010.https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2018/02/28/international-migration-from-sub-saharan-africa-has-grown-dramatically-since-2010/ (accessed 26 November 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Jasemi M., Aazami S., Zabihi R.E. The effects of music therapy on anxiety and depression of cancer patients. Indian J. Palliat. Care. 2016;22(4):455–458. doi: 10.4103/0973-1075.191823. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Sánchez H., Hernández-Enriquez C.B., Sidani S., Hernández Osorio C., Castellanos Contreras E., Salazar Mendoza J. Dance intervention for Mexican family caregivers of children with developmental disability: a pilot study. J. Transcult. Nurs. 2019;31(1):1–7. doi: 10.1177/1043659619838027. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reinhold M., Bürkner P., Holling H. Effects of expressive writing on depressive symptoms—a meta-analysis. Clin. Psychol. (New York) 2018;25(1) doi: 10.1111/cpsp.12224. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gureje O., Nortje G., Makanjuola V., Oladeji B., Seedat. R. Jenkins S. The role of global traditional and complementary systems of medicine in the treatment of mental health disorders. Lancet Psychiatry. 2015;2(2):168–177. doi: 10.1016/S2215-0366(15)00013-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Egharevba H.O., Ibrahim J.A., Kassam C.D., Kunle O.F. Integrating traditional medicine practice into the formal health care delivery system in the new millennium–the Nigerian approach: a review. Int. J. Life Sci. 2015;4(2):120–128. [Google Scholar]

- Pesek T.J., Helton L.R., Nair M. Healing across cultures: learning from traditions. Ecohealth. 2006;3(114):114–118. doi: 10.1007/s10393-006-0022-z. [DOI] [Google Scholar]