Abstract

Background

There are limited data to guide oncology and cardiology decision-making in patients with a left ventricular assist device (LVAD) and concurrent active malignancy.

Objectives

The goal of this study was to describe cancer treatment approaches, complications, and survival among patients with active cancer on LVAD support in 2 tertiary heart failure and oncology programs.

Methods

In this retrospective cohort study, LVAD databases were reviewed to identify patients with a cancer diagnosis at the time of or after LVAD implantation. We created a 3:1 matched cohort based on age, sex, etiology of cardiomyopathy, LVAD implant strategy, and INTERMACS profile stratified by site. Kaplan-Meier analysis and Cox proportional hazards models were used to compare survival between patients with cancer and non-cancer comparators.

Results

Among 1,123 patients who underwent LVAD implantation between 2005 and 2019, 22 patients with LVADs with active cancer and 66 matched non-cancer comparators were identified. Median age was 62 years (range 41 to 73 years); 50% of patients with cancer were African-American, and 27% were women. Prostate cancer, followed by renal cell cancer and hematologic malignancies were the most common diagnoses. There was no significant difference in unadjusted Kaplan-Meier median survival estimates from the time of LVAD placement between patients with cancer (3.53 years; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.41 to 5.33) and non-cancer comparators (3.03 years; 95% CI: 1.83 to 5.26; log-rank P = 0.99). In Cox proportional hazard models, cancer diagnosis as a time-varying variable was associated with a statistically significant increase in death (hazard ratio: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.03 to 4.12; P = 0.04). Patients with cancer had less gastrointestinal bleeding compared with matched non-cancer comparators (P = 0.016). Other complications were not significantly different.

Conclusions

Our study provides initial feasibility and safety data and set a framework for multidisciplinary team management of patients with cancer and LVADs.

Key Words: advanced heart failure, cancer, cancer therapies, left ventricular assist device

Abbreviations and Acronyms: CI, confidence interval; CTCAE, common terminology criteria for adverse events; CMP, cardiomyopathy; CVD, cardiovascular disease; DT, destination therapy; GI, gastrointestinal; HF, heart failure; LVAD, left ventricular assist device

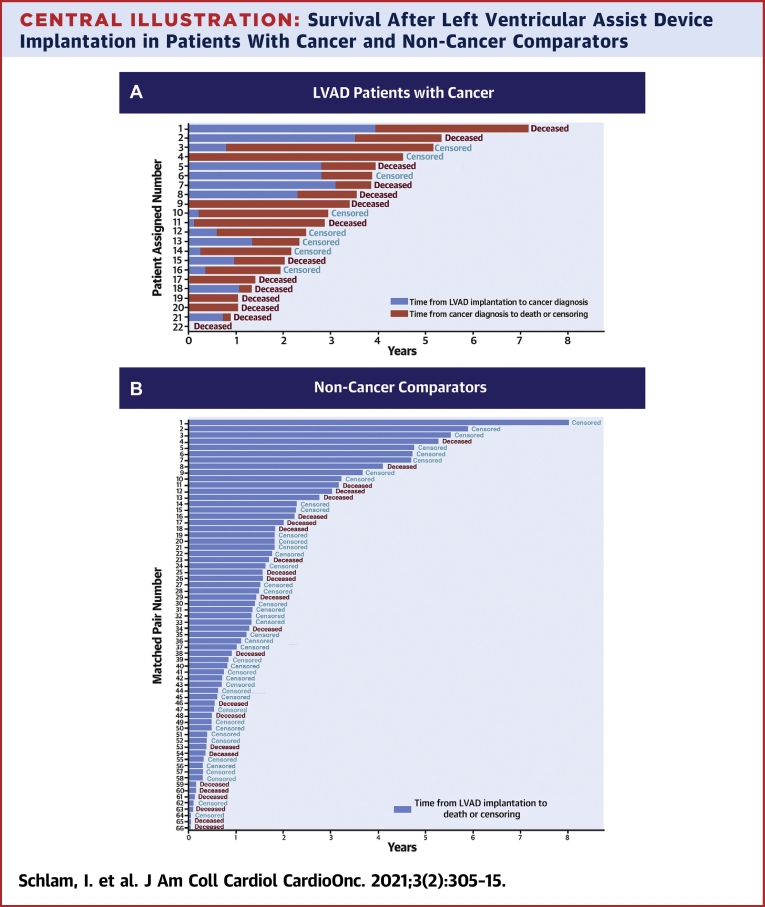

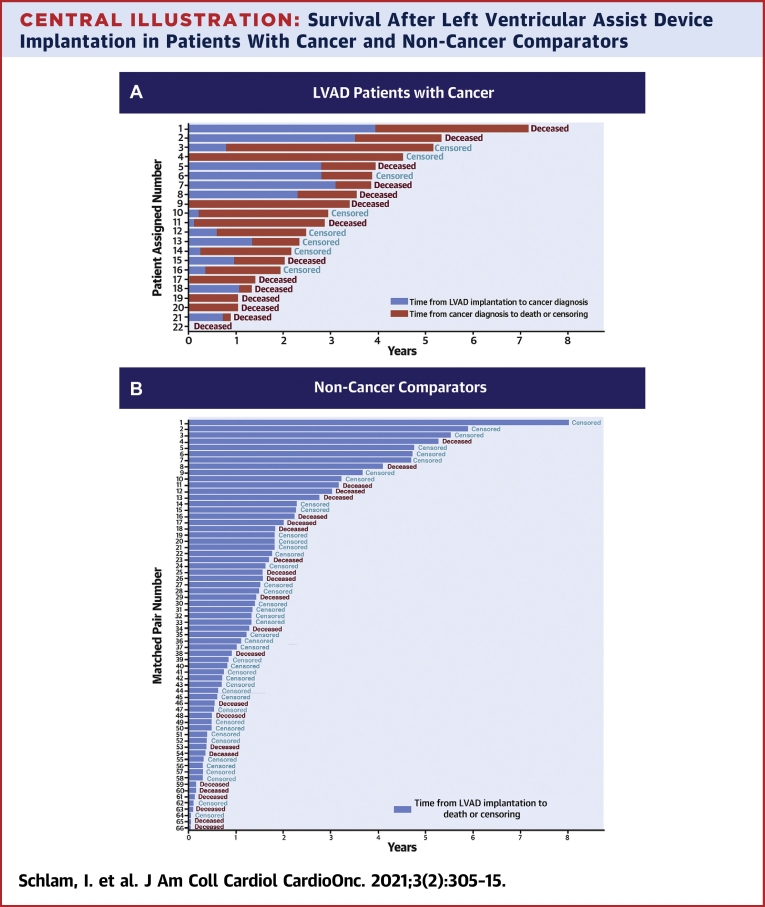

Central Illustration

Heart disease and cancer are the 2 leading causes of death in the United States (1). The National Cancer Institute estimates that more than 1.8 million new cancer cases were diagnosed in 2020 in the United States (2). Cancer incidence increases with age, and it is most frequently diagnosed among people age 65 to 74 years (2). Similarly, the incidence of heart failure (HF) increases with age with estimated lifetime risk as high as 20% to 45% (3,4). It is well-established that shared risk factors exist for cardiovascular disease (CVD) and cancer (5). With the increasing prevalence of HF and cancer, there is a growing population at risk of developing these disease states concurrently.

Advances in the treatment of end-stage HF, including the use of durable mechanical circulatory support with left ventricular assist devices (LVADs), have led to improvements in survival and quality of life (6). Survival has improved with each subsequent generation of LVADs and increase in user experience. In the 2020 Society of Thoracic Surgery-INTERMACS report, 1- and 5-year survival following LVAD implantation improved in the 2015 to 2019 era compared with the 2010 to 2014 era (82.3% and 46.8% vs. 80.5% and 40.9%) (7). In 2019, 3,198 primary LVADs were implanted, which represents the highest annual volume in Society of Thoracic Surgery-INTERMACS history (7). There was a significant recent shift toward implantation as destination therapy (DT), which represented the implant strategy in 73% of the patients in 2019 (7, 8, 9). Because a growing number of patients are undergoing implantation as DT and longevity on LVAD support continues to improve, patients are at risk for developing other common diseases of aging including cancer.

The diagnosis of cancer in patients on durable LVAD support is associated with clinical challenges, including the intent and choice of cancer treatment, monitoring and management of LVAD and cancer-related complications, palliative care, and ethical considerations (10). However, there is limited information about the outcomes of this group of patients.

We conducted a retrospective cohort study across 2 large volume advanced HF and cancer centers and identified patients on LVAD support with a diagnosis of active malignancy. We present cancer diagnoses, cancer treatment approaches, as well as the most common complications and outcomes in this unique group of patients. To compare our findings to the survival of patients with LVAD without cancer, we identified a comparator cohort matched for age, sex, etiology of cardiomyopathy (CMP), LVAD implant strategy, and INTERMACS profile at both institutions.

Methods

Study design

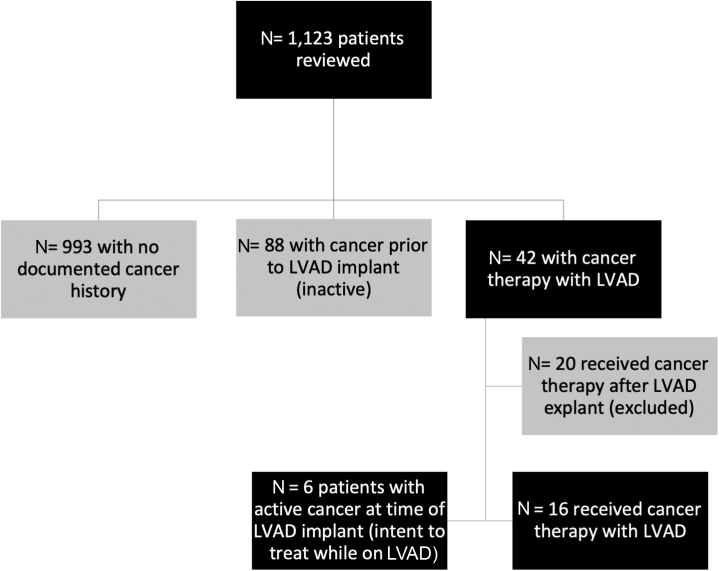

This retrospective matched cohort study was conducted in 2 large volume LVAD centers with advanced HF programs and tertiary care oncology centers. Each center obtained the institutional review board approval from the University of Washington Human Subjects Division and MedStar Health Research Institute to review their respective LVAD databases and identify patients with active cancer during LVAD support between July 2005 and September 2019. Follow-up time was censored at the time of data lock on April 20, 2020. Patients’ individual electronic medical records were reviewed to collect the following variables: demographics, HF history and treatment, LVAD implantation data, type of cancer and stage, cancer-directed therapies (systemic therapy, radiation, surgery), and complications, including bleeding, thrombosis, and infection. Hospitalizations and death from any cause were also recorded. Patient information was collected in a REDCap database. Patients with history of malignancy that were in remission before LVAD and did not have active cancer diagnosis during LVAD support were excluded. Patients with nonmelanoma skin cancer or premalignant conditions were also excluded. In addition, we excluded patients who were diagnosed with cancer after LVAD explant (ie, after heart transplant and heart recovery) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Patient Selection Flowchart

Patients with non-melanoma skin cancer and premalignant conditions were excluded. LVAD = left ventricular assist device.

Matched non-cancer comparator cohort

Non-cancer comparators were identified from the same LVAD databases and matched to patients with cancer at each institution. We used exact 3:1 matching of non-cancer comparators to active patients with cancer based on the following variables: age (±3 years), sex, implant intention (DT, bridge to transplant, bridge to candidacy), CMP etiology (ischemic and/or nonischemic), and INTERMACS profile. Stratified matching was performed for the 2 institutions rather than combined matching to avoid clustering effects by center. Three patients with cancer could not be matched with enough non-cancer comparators based on the preceding criteria, so the INTERMACS profile was relaxed by ±1 which led to enough matches. A total of 12 patients with cancer at MedStar were matched with 36 non-cancer comparators. A total of 10 patients with cancer at University of Washington were matched with 30 non-cancer comparators. Together, our sample consisted of 22 patients with cancer and 66 non-cancer comparators.

Adverse events

The following INTERMACS-defined adverse events were extracted from the LVAD database and presented as events/100 patient-months: LVAD (pump)-thrombosis, ischemic stroke, hemorrhagic stroke, gastrointestinal (GI) bleed, and infection (LVAD-related and non−LVAD-related) (9).

In addition, we performed a chart review in patients with cancer to identify high severity complications, defined as grade 3 or higher based on the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events version 5.0 (CTCAE), and to present them in the setting of the individual cancer treatment received. Grade ≥3 bleeding was defined as hemoglobin <8 g/dL, if transfusion of packed red blood cells was indicated, if an urgent intervention was required, or if life-threatening consequences were reported. Grade ≥3 thrombotic events included pulmonary embolism, cardiac thrombus (including pump thrombosis), cerebrovascular event, or life-threatening complications with hemodynamic and neurologic instability. Grade ≥3 infectious complications were defined as infections that required intravenous antifungal, antibacterial, or antiviral therapy, required an urgent interventional procedure, or resulted in life-threatening complications. The cause of death in patients with cancer was determined by chart review and adjudicated as cancer-related (due to disease progression or cancer treatment complications), LVAD-related, or unrelated to cancer and LVAD complications.

Statistical analysis

For descriptive data analysis, continuous variables are reported as medians with ranges. Categorical variables are reported as counts with percentages. LVAD implant time was treated as time zero, and incidence rates for complications were calculated as time-to-first event, with follow-up until death or end of the study. Crude Kaplan-Meier curves were generated starting at the time of LVAD implant to death. Patients were censored at LVAD explant (transplant or recovery) or end of study follow-up.

We performed Cox proportional hazard regression analysis to compare mortality between patients with LVADs with and without cancer using the time of LVAD implantation as time 0. Our model accounted for the 1:3 matching by using a generalized estimating equation approach, assuming possible dependence between subjects within each matching cluster. A robust estimate of SEs was used to calculate the 95% confidence intervals (CIs). We evaluated for proportional hazard assumption by testing for a nonsignificant relationship between the Schoenfeld residuals and time.

The results were presented as hazard ratio (HRs) with 95% CIs, and a P value <0.05 was used to define statistical significance. All analyses were performed using the lifelines library in Python 3.9 (Python Software Foundation, Wilmington, Delaware) and the survival package in R 4.0.3 (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria).

Results

Patient characteristics

Between July 2005 and September 2019, 1,123 patients underwent LVAD implantation (Figure 1). Twenty-two patients had active cancer and concurrent LVAD, 6 of whom had cancer at the time of LVAD implantation (bridge to cancer treatment), and 16 were diagnosed with cancer after the implantation while remaining on LVAD support. The non-cancer comparator group consisted of 66 patients who underwent LVAD implantation, had no diagnosis of malignancy, and were matched based on age, sex, CMP etiology, implant strategy, and INTERMACS profile.

Patients and the matched comparison group were similar with respect to sex (73% men), and median age at LVAD implant was 62 years in both groups (Table 1). Among patients with malignancies, 50% identified as black/African American and 41% as Caucasian. In the non-malignancy group there were 41% black Americans and 53% Caucasians. Ischemic CMP and idiopathic-dilated CMP were the most common etiologies of HF. Chemotherapy-associated CMP was present only in the malignancy group and accounted for 18% of the patients. Most patients had LVAD implantation as DT.

Table 1.

Demographic Characteristics of Patients With LVADs With Active Malignancy and Matched Non-Cancer Comparators

| Patients With Active Malignancy (n = 22) | Matched Patients Without Cancer (n = 66) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sex | ||

| Male | 16 (73) | 48 (73) |

| Female | 6 (27) | 18 (27) |

| Race | ||

| Black/African American | 11 (50) | 28 (41) |

| Caucasian | 9 (41) | 35 (53) |

| Asian | 2 (9) | 1 (2) |

| American Indian | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Hispanic | 0 | 1 (2) |

| Cardiomyopathy | ||

| Idiopathic | 8 (36) | 32 (48) |

| Ischemic | 8 (36) | 27 (41) |

| Chemotherapy induced | 4 (18) | 0 |

| Other∗ | 2 (10) | 7 (11) |

| Age at LVAD implant (yrs) | 62 (41-73) | 62 (41-76) |

| Goal of LVAD implant | ||

| Destination therapy | 14 (64) | 42 (64) |

| Bridge to transplant | 6 (27) | 15 (23) |

| Bridge to candidacy | 2 (9) | 9 (13) |

| Type of LVAD | ||

| Abbott HeartMate II | 11 (50) | 23 (35) |

| Medtronic HVAD | 7 (32) | 26 (39) |

| Abbott HeartMate 3 | 4 (18) | 17 (26) |

Values are n (%) or median (range).

HVAD = HeartWare ventricular assist device; LVAD = left ventricular assist device.

Sarcoid (n = 3), hypertrophic (n = 2), myocarditis, familial, valvular heart disease, and postviral.

Cancer characteristics, treatment, and complications

Prostate cancer was the most commonly diagnosed cancer (n = 5), followed by renal cell carcinoma (n = 4), and hematologic malignancies (n = 3) (Table 2). There were 4 patients who had a history of completed cancer treatment, all of whom underwent LVAD implantation for chemotherapy-induced CMP. Of those, 3 patients were breast cancer survivors who, after LVAD placement, were diagnosed with multiple myeloma (n = 1), acute myelogenous leukemia (n = 1), and recurrent breast cancer (n = 1). One patient had a history of treated uterine cancer and developed breast cancer after LVAD placement.

Table 2.

Oncological Characteristics of Patients With Active Malignancy (N = 22)

| Type of cancer | |

| Prostate | 5 (23) |

| Renal | 4 (18) |

| Hematologic malignancy | 3 (14) |

| Breast | 2 (9) |

| Lung | 2 (9) |

| Bladder | 2 (9) |

| Neuroendocrine tumor | 2 (9) |

| Other | 2 (9) |

| Median age at cancer diagnosis∗ (yrs) | 61 (41-72) |

| Goal of therapy | |

| Curative | 13 (59) |

| Palliative | 6 (27) |

| No therapy | 3 (14) |

| Type of cancer-directed therapy† | |

| Surgery | 12 (55) |

| Systemic therapy | 11 (50) |

| Radiation | 5 (23) |

Values are n (%) or median (range).

Abbreviation as in Table 1.

6 patients with active cancer at the time of LVAD placement.

Some patients received more than 1 type of cancer-directed therapy.

Individual patient diagnoses, cancer treatment received, and complications are presented in Table 3 with the corresponding individual patient survival shown in the Central Illustration. There were 6 patients who received LVAD therapy as a bridge to cancer treatment. Of 14 patients diagnosed with early stage cancer, 13 received curative intent treatment, and 1 patient with chronic lymphocytic leukemia received no therapy. Of 8 patients with locally advanced or metastatic disease, 6 were treated with palliative regimens, and 2 did not receive cancer therapy (liposarcoma and non-small cell lung cancer). Five patients received radiation therapy while on LVAD support, and 12 patients underwent surgery as part of their cancer treatment. Two patients who received concurrent chemoimmunotherapy were admitted within 20 days of the first cycle with septic shock that led to discontinuation of treatment. One patient received immune checkpoint inhibitors (without chemotherapy) for metastatic renal cell carcinoma and tolerated it without adverse clinical sequelae.

Table 3.

Cancer Diagnosis, Cancer Treatments Received and Complications Among Patients With LVADs With Active Malignancy

| Cancer Diagnosis | Patient Assigned Number∗ | Cancer Therapies |

Complications |

Cause of Death | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Surgery (n = 12) | Systemic Therapy (n = 11) | Radiation Therapy (n = 5) | Bleeding (n = 10) | Thrombosis (n = 7) | Infection (n = 9) | |||

| Prostate | 13 | Radical prostatectomy | Leuprolide | Bacteremia (driveline infection) | N/A | |||

| Prostate | 10 | TURP | Leuprolide | Ischemic CVA | Bacteremia (driveline infection) | N/A | ||

| Prostate | 8 | Leuprolide | 7,920 Gy | Upper GIB | Pump thrombosis | LVAD-related pump thrombosis | ||

| Prostate† | 4 | Leuprolide | Ischemic CVA | N/A | ||||

| Prostate | 2 | TURP | Leuprolide | ICH | Pump thrombosis | Osteomyelitis | LVAD-related ICH | |

| RCC† | 22 | 5,000 Gy | Other | |||||

| RCC† | 17 | Nephrectomy | Bleeding from surgical site | Abdominal wall infection (related to driveline) | Other | |||

| RCC | 12 | Nephrectomy | N/A | |||||

| RCC | 3 | Nephrectomy | Nivolumab, then ipilimumab nivolumab | 2,000 Gy | N/A | |||

| AML | 15 | FLAG-ida | Upper, lower GIB | Cellulitis and pneumonia | Cancer-related | |||

| CLL† | 19 | Anemia | Other | |||||

| Multiple myeloma | 5 | CyBorD, then ixazomib and pomalidomide | Cancer-related | |||||

| Breast | 7 | Nab-paclitaxel and atezolizumab | Sepsis | Cancer-related | ||||

| Breast | 1 | Lumpectomy | Anastrozole | 6,040 Gy | Other | |||

| NSCLC | 21 | Anemia | Cancer-related | |||||

| NSCLC | 6 | Carboplatin, paclitaxel, pembrolizumab | 5,000 Gy | Sepsis | N/A | |||

| Bladder | 11 | TURBT | Hematuria | Pump thrombosis | Other | |||

| Bladder† | 9 | TURBT | Hematuria | LVAD-related chronic infection | ||||

| Neuroendocrine tumor of the pancreas | 14 | Pancreaticoduodenectomy | Bacteremia (driveline infection) | N/A | ||||

| Neuroendocrine tumor of the colon | 16 | Sigmoidectomy | Lower GIB | N/A | ||||

| Liposarcoma† | 20 | Embolic CVA | Sternal wound infection | Cancer-related | ||||

| Cervical | 18 | Hysterectomy and BSO | Vaginal bleed | Pump thrombosis | LVAD-related pump thrombosis | |||

AML = acute myeloid leukemia; BSO = bilateral salpingo-oophoerectomy; CLL = chronic lymphocytic leukemia; CVA = cerebrovascular accident; CyBorD = cyclophosphamide, bortezomib, dexamethasone; FLAG-ida = fludarabine, cytarabine, idarubicin; GIB = gastrointestinal bleed; ICH = intracerebral hemorrhage; NSCLC = non-small cell lung cancer; RCC = renal cell carcinoma; TURBT = trans-ureteral resection of bladder tumor; TURP = trans-ureteral resection of the prostate; N/A = not applicable (patient alive or underwent LVAD explant (transplant or recovery) at end of study follow-up); other abbreviations as in Table 1.

Patient-assigned number corresponds to the y-axis value in Central Illustration showing the individual patient outcome.

Patients who received LVAD as bridge to cancer treatment.

Central Illustration.

Survival After Left Ventricular Assist Device Implantation in Patients With Cancer and Non-Cancer Comparators

The plot indicates number of years after left ventricular assist device (LVAD) implantation until cancer diagnosis (blue bars, A) and until death or censoring event (red bars in A and blue bars in B) patients with cancer (A) and matched non-cancer comparators (B). Patients were censored at LVAD explant (transplant or recovery) or end of study. The numbers on the y-axis of A correspond to the individual patient-assigned number in Table 3.

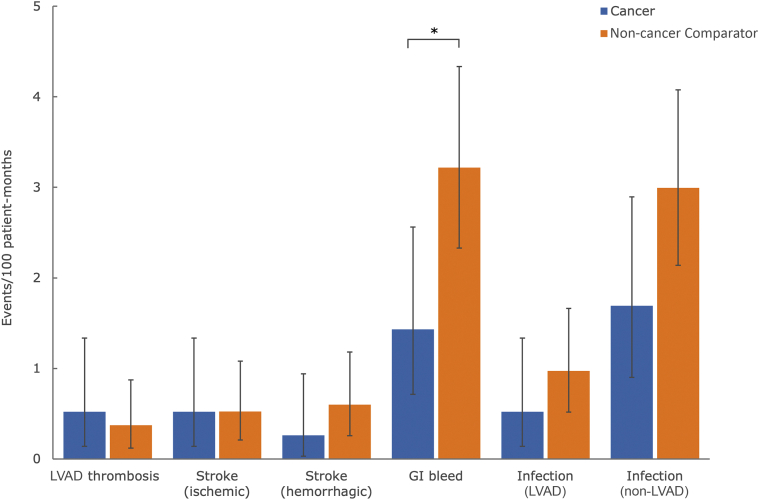

INTERMACS-defined adverse events in patients with LVADs with cancer and matched non-cancer comparators are shown in Central Illustration. There were no significant differences in the event rates between patient groups for pump thrombosis (0.5 events/100 patient-months vs 0.4 events/100 patient-months, respectively; P = 0.858), ischemic stroke (0.5 events/100 patient-months vs 0.5 events/100 patient-months; P = 0.999), hemorrhagic stroke (0.3 events/100 patient-months vs 0.6 events/100 patient-months; P = 0.461), or infection (LVAD-related: 0.5 events/100 patient-months vs 1.0 events/100 patient-months; P = 0.395 and non−LVAD-related: 1.7 events/100 patient-months vs 3.0 events/100 patient-months; P = 0.090) (Figure 2). GI bleeding was less frequent among patients with cancer compared with matched comparators (1.4 events/100 patient-months vs 3.2 events/100 patient-months). Individual patient complications based on CTCAE criteria are presented in Table 3.

Figure 2.

Post-LVAD Adverse Events in Patients With Cancer and Non-Cancer Comparators

Complications are shown as event rates per 100 patient-months in patients with cancer (blue bars) and matched non-cancer comparators (orange bars). ∗P < 0.05 (Fisher's exact test). GI = gastrointestinal; other abbreviation as in Figure 1.

Mortality

Patients were followed for a median time of 2.7 years after LVAD implantation (Central Illustration). No patients were lost to follow-up. For the 16 patients diagnosed with cancer after LVAD implantation, median time from LVAD placement to cancer diagnosis was 371 days (range: 42 to 1,436 days), and the median time from cancer diagnosis to outcome was 514 days (range: 55 to 1,596 days). There were 9 deaths in the group diagnosed with cancer after LVAD placement. There were 5 deaths among 6 patients who received an LVAD as a bridge to cancer treatment, and the time from LVAD placement to death or study closure ranged widely, from 2 to 1,644 days (median: 451 days).

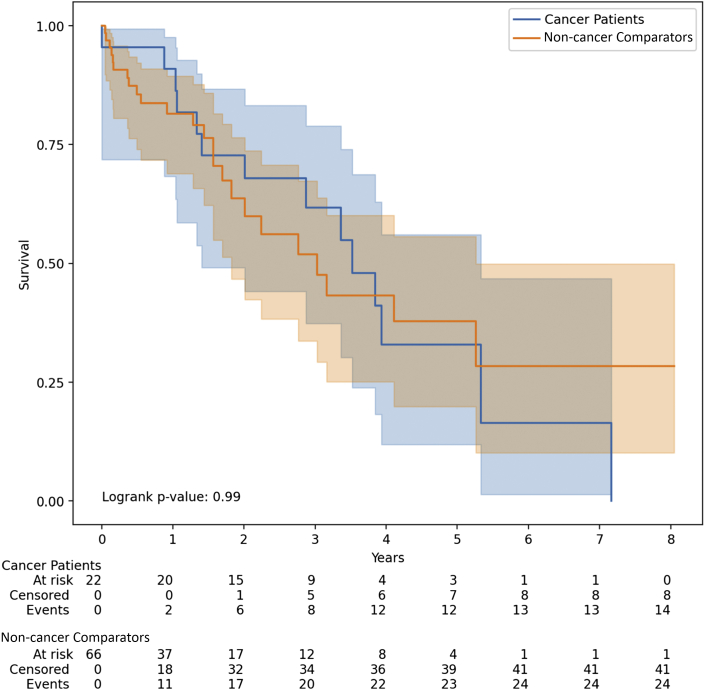

Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no statistically significant difference between the unadjusted survival in patients with LVADs with cancer and patients with LVADs without cancer (log-rank P = 0.99) (Figure 3 ). Among patients with cancer, the Kaplan-Meier median survival estimate from the time of LVAD placement was 3.53 years (95% CI: 1.41 to 5.33) and among non-cancer comparators, it was 3.03 years (95% CI: 1.83 to 5.26). In Cox proportional hazard models, cancer diagnosis as a time-varying variable was associated with a statistically significant increase in death (HR: 2.05; 95% CI: 1.03 to 4.12; P = 0.04). There was no evidence that the proportional hazard assumption was violated (test between the Schoenfeld residuals and time; P = 0.80).

Figure 3.

All-Cause Mortality in Patients With LVADs With Cancer and Matched Non-Cancer Comparators

Kaplan-Meier estimated survival among patients with LVADs with diagnosis of active cancer (n = 22) and without cancer (n = 66). Log-rank test had a P value of 0.99 that showed no statistically significant difference between the curves. Abbreviation as in Figure 1.

Discussion

In our retrospective cohort study, which was the largest to date to describe outcomes of patients with LVADs with active cancer, we identified the following novel findings: 1) among patients with active malignancy, the median survival estimate from the time of LVAD implant was 3.5 years (95% CI: 1.4 to 5.3); 2) Kaplan-Meier curves showed no statistical difference in unadjusted survival between patients with malignancy and their age-, sex-, CMP type-, implant strategy-, and INTERMACS profile-matched comparators without cancer; however, cancer diagnosis as a time-varying covariate was associated with a statistically significant increase in death; 3) among patients diagnosed with early stage cancer after LVAD, most received treatment with curative intent; and 4) complications (stroke, infection, and thrombosis) were not significantly different between patients with cancer and matched comparators, except for GI bleeding. which was less frequent in patients with cancer.

Traditionally, presence of active malignancy has represented a relative contraindication to LVAD implantation, and age-appropriate cancer screening continues to be part of the evaluation for advanced HF therapies (transplant and LVAD). Most centers use similar screening criteria for heart transplant (11) and for LVAD evaluation, including chest and abdominal computed tomography scans, and focused screening for breast, prostate, and colon cancer. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines (12) recommend that patients with history of recently treated or active cancer with life expectancy of more than 2 years might be candidates for DT, whereas a more recent consensus from the European Association of Cardio-Thoracic Surgery recommends consideration of LVAD implantation in patients with cancer with the expected survival of more than 1 year (12,13).

In our study, among 16 patients who developed cancer after LVAD placement, the diagnoses were established after a median time of 371 days, with a wide range from 42 to 1,436 days. Early occurring cancers included urothelial carcinoma on day 42 after LVAD implantation, localized prostate cancer on day 78, and a neuroendocrine tumor of the sigmoid colon on day 92 in a 41-year-old patient, which suggested that following routine age-based cancer screening recommendations would not have captured these diagnoses. In this group of patients, the oncology decision regarding cancer-treatment requires a consideration of curative versus palliative intent based on expected survivorship and risk of complications. The current literature on patients with LVAD and active cancer diagnosis is limited to individual case reports and small case series (14, 15, 16), which suggest feasibility of treatment in select diagnoses such as prostate cancer (17). Our report adds to the field by incorporating detailed oncology chart review of individual patient data, together with HF and/or LVAD characteristics, systematic collection, and adjudication of complications supported by the review of institutional LVAD databases. because LVAD and cancer therapy complications might overlap, we did not attribute specific complications to either diagnosis alone but provided chart-based adjudication of infection, bleeding, and thrombosis, with focus on high severity (CTCAE grade ≥3) complications that might inform oncology decision-making.

The comparison of INTERMACS-defined adverse events in patients with cancer and matched comparators showed no significant differences in the event rates for pump thrombosis, ischemic or hemorrhagic stroke, and infections. The small sample size might have reduced our ability to detect differences; however, no trend was seen to suggest higher risk of complications among patients with cancer. Patients with cancer had significantly less GI bleeding. Potential explanations, such as differences in the anticoagulation strategies, warrant further investigation.

Although Kaplan-Meier survival curves showed no statistically significant difference between the unadjusted survival in patients with LVADs with cancer and matched non-cancer comparators, in Cox proportional hazards models, with cancer diagnosis as a time-varying exposure, cancer diagnosis was associated with a statistically significant increase in the hazard of death. Of interest, a recent investigation by Hong et al. (18) compared 32 patients with LVADs with history of malignancy and 5 patients with active cancer after LVAD implant and found no significant differences in unadjusted Kaplan-Meier survival estimates. Small sample size might have limited the power to detect a true difference in both studies, and further investigation is needed to investigate cancer- and LVAD-related risks in these complex patients.

Six patients underwent LVAD implantation as part of the bridge-to-cancer treatment strategy, thus challenging the paradigm of an active cancer diagnosis being a contraindication for LVAD placement. Literature supporting this approach is limited (19); however, we anticipate that the interest and need for mechanical circulatory support will grow in the future with increased effectiveness of contemporary and emerging cancer therapies. In our study, the longest survival among patients with active cancer at the time LVAD placement was seen in a patient with metastatic prostate cancer who was continuing androgen deprivation therapy after 4.3 years of LVAD support.

Study limitations

The limitations of this study included small size and heterogeneity of cancer diagnoses, stages, and treatment approaches. Based on our Cox analysis and the observed HR of 2.05 with cancer as a time-varying covariate, 81 events would be needed to detect a significant difference with at least 80% power. Using the death rate in our sample, a sample size of 188 patients would be needed to detect a difference. Albeit small, our study had a diverse population (50% black and 27% women) and reflected clinical practice of 2 large urban, tertiary care centers.

We did not model mortality as cause-specific or as competing risk due to the small sample size of cases; however, we would argue that for patients with end-stage HF and comorbidities, overall survival is as important as cause-specific outcomes. Heterogeneity of cancer diagnoses and treatments, with limited sample size, precluded comparisons of treatment-specific complications.

Conclusions

In real-world practice, management of active malignancy in patients on durable LVAD support represents an increasing clinical challenge for oncology and HF teams. Our study provides initial data on cancer treatment, complications, and outcomes, and provides a rationale and framework for creation of cancer-specific cohorts and registries of patients supported with a durable LVAD.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: In this retrospective cohort study, there was no significant difference in survival estimates from the time of LVAD placement (P = 0.99) between 22 patients with cancer (3.53 years) and 66 matched non-cancer comparators (3.03 years). However, in Cox proportional hazard models, cancer diagnosis as a time-varying variable was associated with a statistically significant increase in death (HR: 2.05; P = 0.04). Patients with cancer had less GI bleeding compared with their matched non-cancer comparators (P = 0.016), whereas other complications were not significantly different.

TRANSITIONAL OUTLOOK: Decisions about the intent of cancer-directed therapy (curative vs palliative) among patients on LVAD support needs to include consideration of complications including bleeding, infections, and thrombosis, as well as mortality. Decision-making and management of complications require multidisciplinary team collaboration. For patients with active malignancy on LVAD support, our study provides a framework for further prospective research to guide patient-centered decision-making on cancer treatment and a multidisciplinary approach to complication management.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr Gallagher has been a member of the advisory board for Daiichi Sankyo and Seattle Genetics. Dr Sheikh has been an investigator, has received travel support, has received institutional research; and has received speaker’s fees from Abbott; and has received travel support from Medtronic. Dr Mahr has been an investigator and consultant for Abbott, Medtronic, Abiomed, and Syncardia. Dr Barac has received honoraria from Takeda. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

Ivan Netuka, MD, PhD, served as the Guest Assistant Editor for this paper. Anju Nohria, MD, served as the Guest Editor-in-Chief for this paper.

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Part of the results were presented as an eAbstract at the American Society of Clinical Oncology 2020 Virtual Meeting, May 29-June 2, 2020.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention Leading causes of death 2021. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm Available at:

- 2.Siegel R.L., Miller K.D., Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. 2020;70:7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huffman M.D., Berry J.D., Ning H. Lifetime risk for heart failure among white and black Americans: cardiovascular lifetime risk pooling project. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2013;61:1510–1517. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2013.01.022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Virani S.S., Alonso A., Benjamin E.J. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Koene R.J., Prizment A.E., Blaes A., Konety S.H. Shared risk factors in cardiovascular disease and cancer. Circulation. 2016;133:1104–1114. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.020406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Katz J.N., Waters S.B., Hollis I.B., Chang P.P. Advanced therapies for end-stage heart failure. Curr Cardiol Rev. 2015;11:63–72. doi: 10.2174/1573403X09666131117163825. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Molina E.J., Shah P., Kiernan M.S. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs 2020 Annual Report. Ann Thorac Surg. 2021;111:778–792. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.12.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Han J.J., Acker M.A., Atluri P. Left ventricular assist devices. Circulation. 2018;138:2841–2851. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.118.035566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kormos R.L., Cowger J., Pagani F.D. The Society of Thoracic Surgeons Intermacs database annual report: evolving indications, outcomes, and scientific partnerships. Ann Thorac Surg. 2019;107:341–353. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2018.11.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Cheng R.K., Kirkpatrick J.N., Sorror M.L., Barac A. Cardio-oncology and the intersection of cancer and cardiotoxicity. J Am Coll Cardiol CardioOnc. 2019;1:314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.jaccao.2019.10.003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Mehra M.R., Kobashigawa J., Starling R. Listing criteria for heart transplantation: International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for the care of cardiac transplant candidates--2006. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2006;25:1024–1042. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2006.06.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Feldman D., Pamboukian S.V., Teuteberg J.J. The 2013 International Society for Heart and Lung Transplantation guidelines for mechanical circulatory support: executive summary. J Heart Lung Transplant. 2013;32:157–187. doi: 10.1016/j.healun.2012.09.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Potapov E.V., Antonides C., Crespo-Leiro M.G. 2019 EACTS expert consensus on long-term mechanical circulatory support. Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2019;56:230–270. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezz098. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Raikhelkar J., LaBuhn C., Chung B. Bridge to cancer therapy: can LVAD support allow advanced heart failure patients to survive cancer treatment? J Heart Lung Transpl. 2018;37:S462. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Loyaga-Rendon R.Y., Inampudi C., Tallaj J.A., Acharya D., Pamboukian S.V. Cancer in end-stage heart failure patients supported by left ventricular assist devices. ASAIO J. 2014;60:609–612. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0000000000000116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Smail H., Pfister C., Baste J.M. A difficult decision: what should we do when malignant tumours are diagnosed in patients supported by left ventricular assist devices? Eur J Cardiothorac Surg. 2015;48:e30–e36. doi: 10.1093/ejcts/ezv203. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lee H.H., Shaw N.M., Mohammed S., Kowalczyk K.J., Stamatakis L., Krasnow R.E. Prostate cancer in men with treated advanced heart failure: should we keep screening? Urology. 2020;136:46–50. doi: 10.1016/j.urology.2019.11.022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hong Y., Seese L., Hickey G., Chen S., Mathier M.A., Kilic A. Left ventricular assist device implantation in patients with a history of malignancy. J Card Surg. 2020;35:2224–2231. doi: 10.1111/jocs.14723. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Netuka I., Stepankova P., Urban M. Is severe cardiac dysfunction a contraindication for complex combined oncotherapy of Hodgkin's lymphoma? Not any more. ASAIO J. 2013;59:320–321. doi: 10.1097/MAT.0b013e318289b992. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]