Abstract

Activity that places demands on cognitive resources has positive effects on cognitive health in old age. To further understand determinants of age-group differences in participation, we examined how negative aging stereotypes and responses associated with a cognitively challenging activity influenced future willingness to engage in that activity. Sixty-nine young (20 – 40 years) and eighty older (63 – 84 years) adults performed a letter-number sequencing (LNS) task at different levels of demand for 15 min, during which systolic blood pressure responses—a measure of effort mobilization—and subjective perceptions of task demands were assessed. Approximately half the participants were primed with a negative aging stereotype prior to this task. Following the LNS task, participants completed an effort-discounting task, with resulting subjective values indicating their willingness to perform the task at each level of demand. As expected, both subjective and objective indicators of cognitive demands as well as performance were associated with future willingness to engage in a difficult task, with these effects being significantly greater for older adults. In addition, although stereotype activation influenced older adults’ engagement levels in the LNS task, it did not moderate willingness. Together, the results indicate that, relative to younger adults, older adults’ decisions to engage in cognitively challenging activities are disproportionately affected by their subjective perceptions of demands. Interestingly, actual engagement with the task and associated success result in reduced perceptions of difficulty and greater willingness to engage. Thus, overcoming faulty and discouraging task perceptions may promote older adults’ engagement in demanding, but potentially beneficial activities.

Keywords: Engagement, activity, effort, motivation, aging

Evidence is accumulating that engagement in cognitively demanding activities is beneficial for both the maintenance of cognitive functioning and reducing the probability of dementia in later life (see Hertzog, Kramer, Wilson, & Lindenberger, 2008; Smith, 2016). There is also great variability in the degree to which individuals engage in these activities, raising the question as to what individual characteristics influence engagement rates in potentially beneficial activities. A couple of obvious factors would be health and cognitive ability. For example, some research has suggested a transactional process, with engagement not only promoting cognitive health (e.g., ability), but ability also positively predicting engagement (e.g., Hultsch, Hertzog, Small, & Dixon, 1999; Schooler & Mulatu, 2001). However, research has also highlighted the role of more subjective influences, such as motivation, task experience, perceptions of task demands, and aging stereotypes or attitudes on cognitive engagement (e.g., Hess, Growney, & Lothary, 2019; Hess, Growney, O’Brien, Neupert, & Sherwood, 2018; Hess, Smith, & Sharifian, 2016).

Several theoretical perspectives have hypothesized that changes in personal resources (e.g., ability, health, time) in later life influence goals and associated selection processes (e.g., choosing to engage in specific beneficial activities). These include shifts from primary to secondary control processes (Heckhausen, Wrosch, & Schulz, 2010), increased focus on loss prevention versus growth (e.g., Freund & Ebner, 2005), and greater reliance on accommodative as opposed to assimilative processes (Brandtstädter & Rothermund, 2002). Whereas these perspectives are useful for understanding general developmental processes that may underlie engagement processes, they are less precise in identifying mechanisms associated with engagement in specific types of activities. Building on these perspectives as well as others focusing on effort mobilization (e.g., Brehm & Self, 1989; Obrist, 1981; Wright, 1996), selective engagement theory (SET; Hess, 2014) attempts to better understand determinants of adult age differences in engagement in cognitively demanding activities by examining interactions between situational factors, personal characteristics, and motivation.

Selective Engagement

SET argues that the cognitive costs associated with specific activities are an important determinant of both the motivation to engage in these activities and subsequent participation rates. These costs can be reflected not only in objective indices of effort expenditure associated with performing a task (e.g., systolic blood pressure [SBP] response, cortical activation), but also subjective perceptions of task characteristics (e.g., mental demands). Research has shown that both are related to actual task demands (e.g., memory load), and that aging is associated with an increase in these costs (e.g., Cappell, Gmeindl, & Reuter-Lorenz, 2010; Ennis, Hess, & Smith, 2013; Hess & Ennis, 2012). In addition, subjective perceptions of task demands have been shown to inflate effort expenditure beyond that necessary for successful performance under conditions of high motivation, with this effect being disproportionately greater in older than in younger adults (Ennis et al., 2013; Hess et al., 2016, 2019). In other words, relative to younger adults, older adults are likely to expend more effort than necessary to meet performance standards when engaging in a demanding activity. Collectively, these findings suggest that the costs—both experienced and perceived—associated with task engagement increase with age. Additional research has shown that these costs are negatively associated with the motivation to engage in cognitively demanding tasks, which in turn is associated with self-reported activity in cognitively demanding everyday activities (Ennis et al., 2013; Growney & Hess, 2020; Hess et al., 2018; Queen & Hess, 2018). Of particular note is the possibility that subjective factors (e.g., elevated perceptions of task demand) may negatively impact older adults’ willingness to engage in demanding, but potentially beneficial activities in their day-to-day lives by inflating costs.

Although a coherent picture of the association between costs, motivation, and engagement seems to be emerging from this work, there is an important limitation that leads to more circumspect conclusions regarding the prediction of activity selection and engagement. Specifically, assessments of costs and motivation in the aforementioned studies were made independently of assessments of activity engagement. That is, costs were based on individual characteristics assessed in the lab (e.g., effort required to perform task [Hess et al., 2018]) or surveys (e.g., self-reported health [Queen & Hess, 2018]), which were then used to predict engagement in a variety of everyday activities. There was, however, no assessment of the costs directly associated with these activities. Instead, estimates of cognitive demands were based on the degree to which engagement in specific activities is associated with cognitive ability (see Jopp & Hertzog, 2010, for examples of such relationships), with stronger associations assumed to represent more challenging activities. This assumption may not be unreasonable, with both cross-sectional (Queen & Hess, 2018) and longitudinal (Growney & Hess, 2020) data having shown stronger links between both costs and motivation and those activities that are more highly associated with ability.

Some research has attempted to more directly assess connections between costs and engagement in specific activities within individuals. For example, Salthouse, Berish, and Miles (2002) presented different-aged adults with a list of everyday activities and asked them to rate their frequency of involvement in each as well as the cognitive demands of each activity they performed. They then assessed the relationship between demands and participation. The limitation in this approach is that—in addition to these being subjective assessments of demands—this relationship was only assessed for activities in which individuals actually participated, constraining the ability to examine selectivity. Indeed, a positive association observed between perceived demands and activity may simply reflect the fact that longer duration activities—regardless of objective demands—may be viewed as cognitively taxing.

A potentially more promising approach was taken by Westbrook, Kester, and Braver (2013), who used an effort-discounting task to assess the impact of task demands on engagement. After providing experience with a cognitively demanding task (N-back) at different memory loads, young and older adults made a series of choices about performing an easier or more difficult version of the task for different amounts of money. For both age groups, the amount of money required to perform the more difficult task increased as the load increased. In other words, discounting increased with an increase in the objective task demands of the comparison task. In addition, this effect was stronger in the older group. This suggests that increases in cognitive demands decrease the willingness of individuals to perform a specific activity, with this effect being particularly consequential in older adults (i.e., old age is associated with greater selectivity). Notably, factors that might be reflective of personal costs, such as performance or subjective perceptions of task demands, were not strong predictors of discounting.

In the present study, we attempted a more elaborate exploration of how the individual’s experiences with a specific task influence their willingness to engage in that task. Specifically, young and older adults were given extensive experience with a working-memory task at several different levels of memory load. In addition to performance, we also assessed subjective perceptions of cognitive costs, as reflected in ratings of mental demands and effort requirements, as well as SBP responsivity during the task. This latter measure has been used as an index of effort mobilization or expenditure (e.g., Obrist, 1981; Wright, 1996), and it has been argued that it is a valid measure for assessing age differences in effort (Hess & Ennis, 2014). We then had participants complete an effort-discounting task similar to that used by Westbrook et al. (2013) to assess selection processes in engagement.

Of primary interest were the factors predicting preferences for tasks based on their objective memory loads, as indicated by subjective value. SET argues that the demands experienced by the individual (i.e., costs) will influence their willingness to engage in a specific task, with these costs being particularly consequential for older adults. Within SET, these costs were originally conceptualized in terms of the effort necessary to perform the task and the associated consequences (e.g., fatigue). However, research has demonstrated that perceived costs may also influence task engagement, with such effects being stronger for older than for younger adults (e.g., Hess et al., 2016). Thus, consistent with past research, we predicted that SBP responsitivity, subjective perceptions, and performance will be related to the objective demands (i.e., memory load) of the task. We further predicted that these effects would be generally stronger in the older adults in comparison to the young adults. Finally, we examined the degree to which specific types of outcomes associated with task engagement would predict task selection in the discounting task. Consistent with SET, we predicted that the greater costs—both experienced and perceived—and lower performance associated with a specific level of task demands, the lower the subjective value assigned to that level will be. In other words, participants will require more incentive to complete task levels associated with greater costs. We also predicted that these effects would be stronger for older than for younger adults.

Aging Stereotype Influences on Engagement

Previous research has also shown that negative beliefs about aging affect effort mobilization in both young (Zafeiriou & Gendolla, 2017) and older (Hess et al., 2019) adults, and are associated with reduced motivation to engage in cognitively demanding activities (Hess et al., 2018). This suggests that stereotypic beliefs about aging might also influence task preferences, potentially through appraisals of task difficulty. For example, Zafeiriou and Gendolla (2017) argued that elevated levels of engagement exhibited by younger adults following priming of an aging stereotype may reflect an increase in perceptions of task difficulty consistent with beliefs about reduced cognitive skills in old age. Given the findings of these studies, we decided to also investigate the extent to which activation of a negative aging stereotype would affect selection processes and influence both the costs associated with the working-memory task and the types of factors that would determine eventual choices involving engagement in high versus load demand activities. Consistent with this past research, we predicted that experimental activation of a negative aging stereotype would elevate levels of effort expenditure. If such effects are due to associated changes in task appraisal, we also expected stereotype activation would lead to an increase in subjective perceptions of task demands. (Interestingly, Zafeiriou and Gendolla found no impact of activation on subjective perceptions.) Of greater interest, however, was the effect of stereotypes on the weighting of predictors of task selection, as reflected in subjective-value assessments from the discounting task. Given the just-discussed research, we predicted that activation of a negative aging stereotype would accentuate the influence of costs—both perceived and experienced—on task selection.

Method

Participants

Our study used an extreme age-groups design to compare general tendencies in performance between younger and older adults. We chose this design given that this study reflected an initial exploration of these ideas using the discounting task, and a simple comparison between age groups was expected to provide us with information about general age trends and the usefulness of this approach. We also had no specific hypotheses about midlife, and expected that the most dramatic differences between age groups would be observed between young and older adults. Thus, we recruited participants within each age group from a similarly wide age range (approximately 20 years) using age cut-offs similar to those used elsewhere in the literature. Notably, the older group included an age range that might be characterized as representing the third age (i.e., relatively healthy, high-functioning older adults), during which the benefits of engagement may be most consequential.

Our sample included people from the local university as well as community-based volunteers who were recruited via paper flyer, newspaper, and online advertisements from the Raleigh, North Carolina, area. Individuals were ineligible to participate at recruitment if they: (a) received a score greater than 6 on the Short Blessed Orientation–Memory–Concentration Test (n = 2; Katzman et al., 1983); or, (b) had uncontrolled hypertension or medical conditions that could affect their cardiovascular responses (e.g., diabetes, coronary heart disease, congestive heart failure; n = 7). Those exhibiting initial blood-pressure levels greater than or equal to 160/100 mmHg at the time of their lab visits were also deemed ineligible and were not included in the study (n = 1). The data from three young and two older adults were further excluded from analyses due to malfunctions in recording equipment. The final sample of 69 young adults (37 women) aged 20 to 40 included 40 European Americans, 12 Asian Americans, 8 African Americans, 1 Native American, and 7 individuals identified as other or mixed race. Forty-nine of the younger adults were undergraduate students. The older group comprised 80 individuals (40 women) aged 64 to 83, including 73 European Americans, 2 African Americans, 1 Native American, 1 Pacific Islander, and 3 individuals identified as mixed race or other.1 Each participant received $30 plus a $5 bonus (see Procedure) for participating in the study. More information about the sample is presented in Table 1. The observed differences between age groups were generally consistent with findings elsewhere in the literature (e.g., older adults had higher verbal skills and mental health scores than younger adults, whereas the opposite was true for perceptual speed and physical health). The only observed gender difference was due to women having significantly higher perceptual speed scores than men, t(147) = 2.71, p = .008.

Table 1.

Participant Characteristics

| Young Adults | Older Adults | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Measure | M | SD | M | SD | t(147) | p |

| Age | 23.6 | 4.6 | 72.1 | 4.9 | - | - |

| Education (Years) | 15.9 | 2.0 | 17.0 | 2.5 | 3.01 | .003 |

| SF36 Physical Health | 49.0 | 4.9 | 46.9 | 4.8 | 2.55 | .01 |

| SF36 Mental Health | 46.7 | 12.0 | 57.4 | 5.4 | 7.22 | <.001 |

| Expectations Regarding Aging | 2.7 | 0.5 | 2.7 | 0.5 | 0.68 | .50 |

| Vocabulary | 21.0 | 5.1 | 27.2 | 4.8 | 7.53 | <.001 |

| Digit-Symbol Substitution | 88.1 | 14.3 | 63.2 | 11.8 | 11.67 | <.001 |

| Stroop | 0.59 | 0.09 | 0.48 | 0.09 | 7.84 | <.001 |

| Plus/Minus | 0.68 | 0.11 | 0.69 | 0.12 | 0.05 | .96 |

This project was reviewed and approved by the Institutional Review Board at North Carolina State University.

Materials and Equipment

Cardiovascular responses.

Systolic blood pressure (SBP) was recorded using a CNAP monitor (CNSystems Medizintechnik AG, Graz, Austria) in conjunction with a BIOPAC MP150 system (BIOPAC Systems, Inc., Goleta, CA). This system uses an arm cuff for calibration and two finger cuffs to measure finger arterial pressure, which is then converted into predictions of brachial arm pressure.

Priming Task.

Two different computer-based judgement tasks were created. For the negative stereotype task, the materials used were the same as those used in Hess et al. (2018). Specifically, images of three men and three women in the 65- and 85-year-old age range with grumpy or sad expressions were taken from The Center for Vital Longevity Face Database (Minear & Park, 2004). Each face was accompanied by a brief vignette about the individual, describing mostly negative information. Here is an example description:

Robert is 67 years old. After his recent retirement, he has struggled to keep himself occupied throughout the day. His wife is still employed as a school teacher, and he feels lonely after she leaves for work each morning. He wishes he could get together with his friends who meet up to play tennis each week, but he fears he doesn’t have the energy to play like he used to.

In the control task, six neutral pictures displaying household objects (e.g., basket, clock) were taken from the International Affective Picture System (IAPS; Lang, Bradley, & Cuthbert, 2008). Each picture was paired with a description of the name and general purpose of the object as well as one random fact about it. The length and style of descriptions were made to be similar to the negative stereotype task. Since our interest was primarily in how activation of negative aging stereotypes influenced perceptions of task demands and engagement patterns, this control condition served as a type of baseline.

Target task.

A computerized-version of the Letter-Number Sequencing (LNS) task (WAIS-III, Wechsler, 1997) was used to provide participants with experience performing a cognitively demanding task, and served as a basis for their choices in the discounting task. Following the same format as in the standardized version of the task, stimulus sets containing sequences of 3 to 7 items (i.e., memory loads) were created, with randomly selected letters and numbers alternating within each sequence. For each sequence, items were presented sequentially in the middle of the computer screen, with each being displayed for 1,000 ms, with a focal point between each item being displayed for 1,000 ms. Stimulus sequences were presented in blocks of increasing memory load, with each block lasting for 3 min. We did not equate the number of sequences presented at each level of memory load to avoid confounding the demands associated with time on task with those associated with the number of items. However, in order to ensure adequate experience, a minimum of four sequences were given at each level.

Discounting task.

To assess task preferences, we used a modified version of the effort discounting task used by Westbrook et al. (2013). Participants were forced to choose between performing the LNS task with a memory load of 3 items versus a more demanding version of the task (e.g., memory load = 5) for a greater amount of money. Attached to each option was a monetary incentive offer, starting at $1.50 for the easiest level and $3.00 for the more demanding ones. Whereas the amount offered for the more demanding tasks remained constant, the amount offered for the easiest task changed after each choice. After the first offer for a given comparison, the amount offered for the easier task either increased by 50% of the initial offer if the more demanding task was chosen or decreased by the same amount if the easier task was chosen. The amount added or subtracted for each subsequent offer was also 50% of the amount of the previous change, increasing the total amount offered if the more demanding task was chosen or decreasing it if the easier task was chosen. After six of these decision trials for a given comparison between two levels of the task, a point of indifference (POI) was calculated as the hypothetical seventh-offer value that would have been shown to the participant for that particular comparison. POI represents the equalization of greater effort compared to greater cost for each higher demand level of the LNS task compared to the easiest level. There were six comparisons between the least demanding version of the task and each of the more demanding versions (i.e., memory loads of 4, 5, 6, & 7), totaling 24 decisions. Examples of two possible series of decisions are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Two Examples of Possible Decision Paths and Outcomes in the Effort-Discounting Task

| Example 1 | Example 2 | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Step | Option A: Difficult Task | Option B: Easy task | Choice | Option B: Easy task | Choice |

| 1 | $3.00 | $1.50 | A | $1.50 | B |

| 2 | $3.00 | $2.25 | A | $0.75 | B |

| 3 | $3.00 | $2.63 | B | $0.38 | A |

| 4 | $3.00 | $2.44 | B | $0.57 | A |

| 5 | $3.00 | $2.35 | A | $0.66 | A |

| 6 | $3.00 | $2.40 | B | $0.71 | A |

| Point of indifference | $2.38 | $0.74 | |||

| subjective value | 0.79 | 0.25 | |||

Note: Value of the difficult option is always the same. Thus, in each example, Option B is being compared with the unchanging Option A. Choice indicates the option chosen, with the options on the next line resulting from this choice. As indicated in the text, subjective value was calculated by dividing the point of indifference by $3.

Subjective ratings.

To measure subjective perceptions of costs associated with task demands, a computerized version of the NASA Task-Load Index (TLX; Hart & Staveland, 1988) was used. Each of the six TLX components (mental demands, physical demands, temporal demands, performance, effort, and frustration) is represented by a single item (e.g., “How mentally demanding was the task?”). Rating scales for each component were presented on the computer screen individually in the same order every time, and participants used a slider scale from very low to very high (or perfect to failure for the performance subscale) to indicate their responses. These responses were later converted to scores of 1 to 100. Given their relevance to the definition of cognitive costs within SET (e.g., Hess et al., 2016), we focused on ratings of mental demands and effort. These ratings were highly correlated with each other at each level of memory load (rs = .64 - .84), and thus we computed a composite score reflecting costs based on the mean of the two ratings for use in later analyses.

Cognitive ability.

In order to characterize the sample, several tests were given to measure cognitive ability. These included the Digit-Symbol Substitution subtest of the Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale III (WAIS-III, Wechsler, 1997) and Vocabulary Test V-2 from the Kit of Factor-Referenced Cognitive Tests (Ekstrom, French, Harman, & Derman, 1976). Participants also completed a verbal Stroop task (Stroop, 1935) and the plus-minus task (Jersild, 1927) to assess inhibitory control and task-switching, respectively.

Beliefs about aging.

The 12-item Expectations Regarding Aging survey (ERA; Sarkisian, Steers, Hays, & Mangione, 2005) was used to assess beliefs about aging (α = .76).

Procedure

Prior to coming into the lab, participants completed an on-line Qualtrics survey containing the ERA as well as several measures unrelated to the present research. Once participants arrived at the lab, they completed the informed consent form. Their blood pressure was then screened using a HEM-780 monitor (Omron Health care, Inc., Kyoto, Japan). If their blood pressure exceeded 160/100mmhg, they were asked to relax for 5 min, after which a second reading was taken. If readings still exceeded the previously described limits, they were compensated but excluded from further participation. For qualifying participants, the CNAP monitor was then attached to the index and middle fingers of their non-dominant hand and the calibrating arm cuff was placed on the same arm. Participants were given instructions to relax silently for 10 min while the CNAP calibrated and collected the first baseline blood pressure assessment. No materials were provided during the baseline assessment and the words “Relax” or “Please continue to relax” were displayed on the screen using the E-Prime 3.0 software (Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). The last 5 min of this assessment was used as the primary baseline measurement.

Following a mood assessment (i.e., current negative and positive mood), participants completed the priming task. Participants were randomly assigned to be in either the control (32 young, 39 old) or negative (37 young, 41 old) condition. For the negative stereotype condition, participants were asked to form an impression about each of the six people they viewed based on their descriptions. They then responded to four questions (using a 5-point scale) based on their impression of the target person: (a) How mentally fit is this person? (b) How healthy is this person? (c) How active is this person? and (d) How happy is this person? Mean ratings for these four items were toward the lower end (i.e., negative) of the rating scale for both young (M = 2.2, SD = 0.5) and older (M = 2.1; SD = 0.4) adults, with both means being significantly (ps < .001) lower than the midpoint of the scale. Thus, this task had the intended effect of priming negative views about older adults. For the control condition, participants were asked to help researchers learn more about the previously described household objects used as stimuli for a future study. After viewing each object and the associated description, they provided responses on a 5-point scale to the following: a) How interesting is this object? b) How useful is this object? c) How common is this object? and d) How versatile is this object?

After completing the priming task, participants were given another mood assessment. Participants were then asked to relax silently for 3 min to collect an additional baseline cardiovascular measure before moving on to the next task.

The computer-based LNS task was then presented. Participants completed a series of practice trials consisting of two 3-item, two 4-item, and one 5-item series. They then completed five 3-min trial blocks, presented in ascending levels of demand. Within each block after each sequence was presented, participants were instructed to repeat verbally the numbers first, in numerical order, and the letters second, in alphabetical order. Participants continued to be presented with new sequences within each block until 3 min had expired, with participants also completing the NASA-TLX at the end of each block. The experimenter recorded their responses to each sequence and provided feedback about their score after each block.

The effort-discounting task was presented next. Participants were instructed to reflect back on their experience with the LNS task as they were presented with each decision. In order to maintain motivation, participants were also told that the computer would randomly select a demand level and monetary value based upon the choices they had made at the end of the task, and that they would have a chance to earn an extra bonus by completing additional trials at that demand level. Participants were also told to keep in mind the accuracy of their decisions because they would need to maintain a high level of performance when completing a future LNS task related to these decisions. In reality, the memory load and associated value for this task were the same for all participants, but was made to appear as though the computer had calculated the level and bonus amount. All participants completed four sequences of the 5-item LNS for $1.25 each, earning a $5 bonus amount. In order to maintain engagement, they were also informed that we would monitor their performance and CV responses during this final test phase. Upon completing this task, the CNAP machine was turned off and the participants were disconnected from the CV recording equipment.

Following this, participants completed the Digit-Symbol Substitution, Vocabulary, Stroop, and Plus-Minus tests. They also completed a brief demographics survey, the SF-36 health survey (Ware, 1993), and a chronic conditions checklist based on that used in Midlife in the United States study (http://midus.wisc.edu) on Qualtrics, after which participants were debriefed and compensated for their participation.

Data Preparation and Analytic Plan

Cardiovascular responses were recorded throughout the task and after completing all tasks with the BIOPAC system. AcqKnowledge software (BIOPAC Systems, Inc.) was used to record and clean the data, allowing us to eliminate artifacts in the data caused by movement and other factors. Means were then calculated for each segment of the task using these cleaned data. Responsivity scores (SBP-R) were calculated by subtracting mean baseline SBP from the mean of each LNS block.

The four POI values obtained from the discounting task were normalized by the reward magnitude (for example: $1.50/$3.00 = $0.50), resulting in a subjective value (SV) assigned to each demand level of the LNS task. Lower values reflected greater unwillingness to engage in more cognitively demanding tasks even as incentives increase.

Multilevel modeling (MLM) was used as our primary analytic strategy for all dependent measures, with both linear and quadratic effects of memory load included as Level 1 factors. Age group and priming condition were included as Level 2 variables, along with all cross-level interactions.2 The quadratic effect of memory load was included to allow for curvilinear functions associated with disengagement at high levels of task demands (e.g., Ennis et al., 2013). When the quadratic main effect and interactions were not significant, the model was re-run without them to simplify the analysis. Follow-up analyses to examine significant age or condition effects were conducted by re-running the same model, but using specific age groups or conditions as reference groups (e.g., re-centering age group on the young group). Analyses were conducted using SAS Proc Mixed Version 9.4 (SAS Institute, 2013), allowing for random intercepts and slopes. All variables were standardized prior to analysis to permit calculation of standardized effects.

The main analyses proceeded through three different steps. First, we examined participant responses associated with the target task by assessing performance, effort expenditure, and subjective perceptions of task demands. Next, we assessed task preferences based on responses in the discounting task. Finally, we attempted to use the experiential information to predict these preferences and age-group differences therein.

Results

Preliminary analyses

Prior to our main analyses, we performed 2 × 2 (Age Group × Priming Condition) analyses of variance on the measures included in Table 1 to determine potential differences across conditions that might complicate interpretation of effects. The obtained age effects were consistent with previous studies, with young adults having better physical health, digit-symbol, and Stroop scores, whereas older adults had better mental health and vocabulary scores. Older adults also had higher education levels, potentially relating to the presence of undergraduate students in our young sample. Only two significant condition effects were observed, with those in the negative stereotype condition having more positive ERA scores than those in the control condition (Ms = 2.8 vs. 2.6), but worse scores on the plus/minus test (Ms = 0.67 vs 0.71). Controlling for these differences in the analyses below, however, had no impact on the observed condition effects.

Task-Related Responses

We first focused on performance, effort expenditure, and ratings collected during the primary LNS task to examine participants’ responses associated with the task.

Performance.

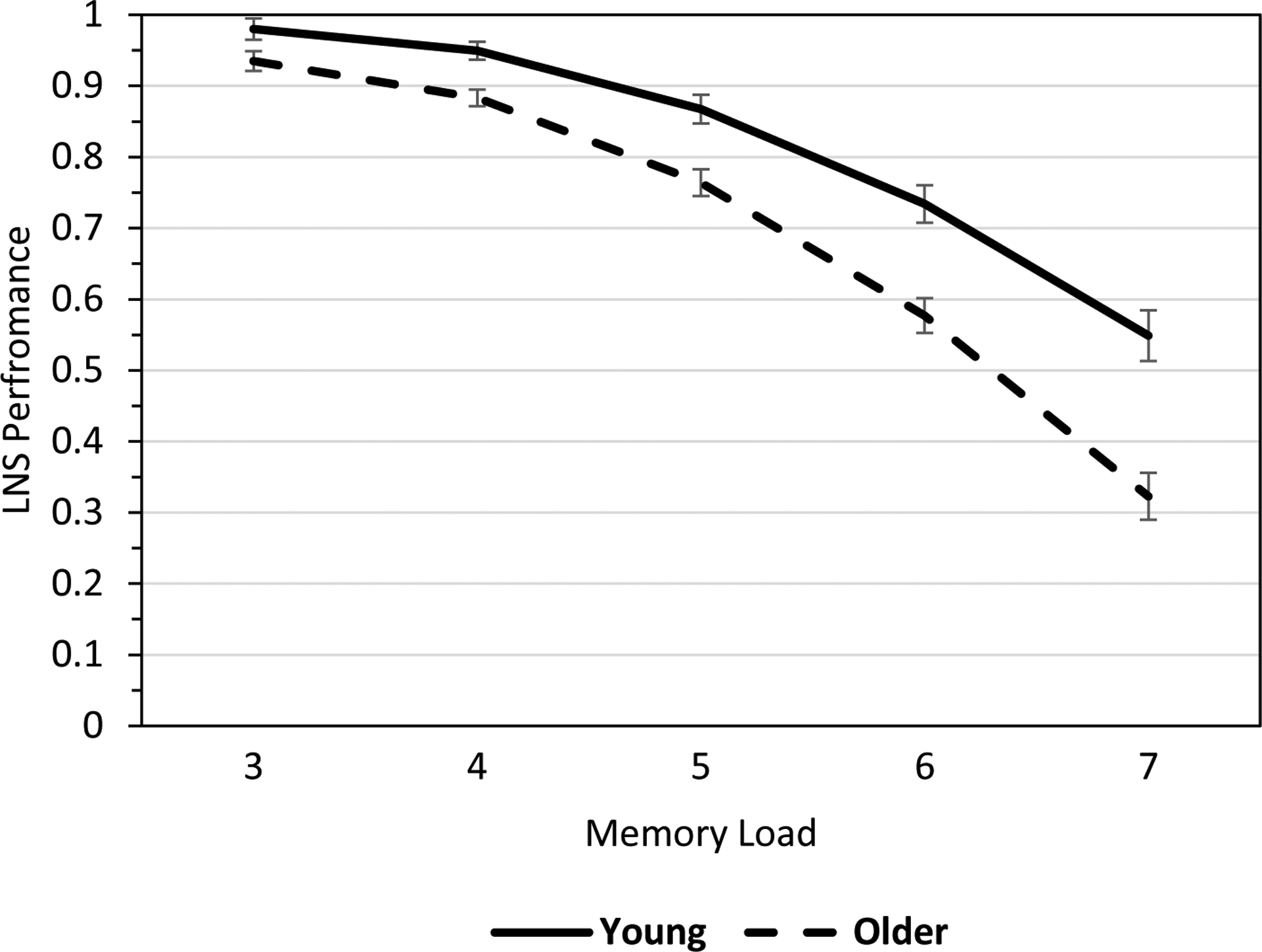

We examined the proportion of strings correctly recalled on the LNS task (Figure 1) using the traditional scoring method (i.e., 1 if all items were recalled in correct order, 0 if not). Young adults performed better than older adults, ß = −0.17, t(145) = −3.69, p = .0003. In addition, significant linear, ß = −0.64, t(588) = −21.70, p < .0001, and quadratic, ß = −0.21, t(588) = −10.10, p < .0001, effects due to memory load were obtained, reflecting negatively accelerating decline in recall as demands increased. A significant Age × Memory Loadlinear interaction, ß = −.11, t(588) = −3.71, p = .0002, was due to the decline with demands being steeper in the old (ß = −.75) than in the young (ß = −.53). There were no significant effects related to priming condition (ps > .13).

Figure 1.

Estimated Letter-Number Sequencing (LNS) performance (± 1 SE) as a function of memory load and age group.

Effort expenditure.

We next examined SBP-R using a similar analysis, including baseline SBP as a covariate to control for possible differences in range of response as a function of starting point. As expected, older adults had higher responsivity while performing the LNS task than did younger adults, ß = 0.36, t(144) = 4.53, p < .0001. In addition, both the linear, ß = −.05, t(580) = −2.29, p = .02, and quadratic, ß = −.06, t(580) = −2.99, p = .003, effects of memory load were significant. As expected, age moderated the effect of demands, as reflected in a significant Age × Memory Loadquadratic interaction, ß = −0.06, t(580) = −3.19, p = .002. Examining effects within each age group revealed no significant effects due to memory load (ps > .12) in the young group, whereas the quadratic effect of memory load was significant in the old group, ß = −0.11, t(580) = −4.36, p < .0001. In addition, this analysis revealed a significant Priming Condition × Memory Loadlinear interaction, ß = 0.07, t(580) = 2.20, p = .03. As can be seen in Figure 2, responsivity was fairly consistent across levels of demands in the young, but increased and then tailed off in the old. This latter trend is suggestive of disengagement by the older adults as the task got too difficult. In addition, engagement was generally lower in the negative stereotype condition than in the control condition for the older adults, with the pattern of increasing engagement followed by disengagement being more evident in the latter condition.

Figure 2.

Effort expenditure (SBP-R estimates, ± 1 SE) as a function of memory load, age group, and priming condition.

Subjective perceptions.

Finally, we examined TLX ratings as a function age group, priming condition, and memory load. The linear and quadratic effects associated with memory load were both significant—β = 0.61, t(588) = 28.45, p < .0001, and β = −0.07, t(588) = −4.48, p < .0001, respectively—due to ratings reflecting a negatively accelerating function with an increase in memory load. A small, but significant effect was also obtained for priming condition, β = −0.19, t(588) = −3.23, p = .002, with ratings in the control group being greater than those in the negative stereotype condition. Condition also moderated the quadratic component of memory load, β = −0.04, t(588) = 2.43, p = .02. There were no significant effects due to age group (ps > .16). These trends are depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Estimated (± 1 SE) ratings of cognitive costs as a function of age, task condition, and memory load.

Summary.

Together, the results from these three sets of analyses support the general contention that old age is associated with higher costs relating to engagement in a difficult working memory task. This was reflected in actual performance and objective assessments of energy expenditure (i.e., SBP-R). Somewhat surprisingly, age group differences in subjective ratings of cognitive costs were not significant. The impact of priming condition was evident primarily in the older group, where engagement levels somewhat unexpectedly were generally lower in the negative stereotype condition relative to the control condition.

Task Preferences

Our main focus was on how these responses associated with engagement within a specific activity affected decisions to engage in that activity. To do this, we used the subjective value (SV) assigned to a specific level of memory load obtained from the discounting task as the primary dependent measure. Note that since the discounting task always involved comparing the lowest memory load (i.e., 3) with each of the higher levels, there were only four levels of the memory load variable in this analysis.

In this initial model, older adults had lower SVs (i.e, preferred easier versions of the task) than did younger adults, β = −0.24, t(145) = −3.57, p = .0005, and SVs decreased as memory load increased, β = −.56, t(439) = −12.13, p < .0001. In addition, condition moderated the effect of memory load, β = −.06, t(439) = −12.13, p = .0006. Follow-up analyses within conditions revealed that the interaction was due to the effect of memory load being stronger in the negative condition (β = −0.16, p < .0001) than in the control condition (β = −0.10, p < .0001). Notably, these analyses also revealed that age interacted with memory load in the control condition (β = −0.06, p = .02), but not in the negative condition (β = 0.01, p = .84). As can be seen in Figure 4, these effects reflected the fact that SVs were lower for the younger adults in the negative than in the control group, with the negative effect of demands being greater in the former condition.

Figure 4.

Estimated subjective value (± 1 SE) derived from responses on the discounting task as a function of age group, task condition, and memory load.

Prediction of Task Preferences

Our primary interest was in determining which responses associated with task engagement were predictive of subsequent task choice, as reflected in the discounting task. The focus was on three sets of predictors: performance (proportion correct on LNS task); effort expenditure (SBP-R); and subjective perceptions of cognitive costs (TLX ratings). For each set of analyses, SV was used as the dependent variable, and performance, effort, or cognitive cost ratings for memory loads of 4 to 7 were used as predictors instead of actual memory load. (Again, note that SV scores were not available for a memory load of 3.) Of primary interest were the impact of each of these experience factors on task preferences, and the degree to which this impact was moderated by age group or priming condition.

Three general observations can be made based on these results (see Table 3). First, performance, effort expenditure, and subjective assessments of cognitive costs all had an impact on SV, with better performance, greater effort, and ratings of costs all being associated with higher rates of selecting the more demanding tasks (i.e., higher SVs) in the discounting task. Second, priming condition had minimal influence on preferences, with its effect only being evident for performance. In addition, priming condition only moderated performance in the young group due to its impact being greater in the negative condition (β= 0.65, p < .0001) than in the control condition (β = 0.30, p = .0002). Finally, ratings of cognitive costs were found to be more predictive of SV scores in the old group, β = −0.68, p ≤ .0001, than in the young group, β = −0.47, p ≤ .0001. In addition, although the Age × SBP-R interaction was not significant, follow-up analyses conducted to provide further information relevant to our hypotheses revealed that the impact of SBP-R on task preference was significant in the old group, β = 0.22, p < .01, but not in the young, β = 0.13, p = .30.

Table 3.

Prediction of Task Preference (i.e., Subjective Value) from Responses Associated with Task Experience

| Performance (LNS) | Effort Expenditure (SBP-R) | Cognitive costs (TLX) | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| MLM Factor | β [95% CI] | SE | p | β [95% CI] | SE | p | β [95% CI] | SE | p |

| Intercept | .09 [−.01, .19] | .05 | .09 | −.002 [−.13, .12] | .06 | .97 | .16 [.04, .29] | .06 | .01 |

| Age Group | −.14 [−.24, .04] | .05 | .006 | −.32 [−.45, −.19] | .07 | <.0001 | −.23 [−.36, −.11] | .06 | .0003 |

| Condition | −.11 [−.22, −.01] | .05 | .03 | −.10 [−.22, .03] | .06 | .13 | −.19 [−.31, −.06] | .06 | .003 |

| Response1 | .48 [.41, .55] | .05 | <.0001 | .17 [.03, .32] | .08 | .02 | −.57 [−.66, −.48] | .05 | <.0001 |

| Age × Condition | .12 [.02, .23] | .05 | .02 | .15 [.02, .28] | .06 | .02 | .09 [−.04, .21] | .06 | .18 |

| Age × Response | .01 [−.06, .08] | .03 | .81 | .04 [−.11, .20] | .08 | .56 | −.11 [−.20, −.01] | .05 | .03 |

| Condition × Response | .09 [.02, .16] | .03 | .01 | .01 [−.14, .15] | .07 | .92 | −.05 [−.14, .04] | .05 | .32 |

| Age × Condition × Response | −.09 [−.16, −.02] | .03 | .01 | −.03 [−.21, .10] | .08 | .62 | .05 [−.05, .14] | .05 | .34 |

[Response] refers to the experience factor indicated at the top of the columns (i.e., performance, effort, rating of cognitive costs) that was used in the specific analysis.

Together, these findings suggest an interesting pattern. Specifically, individuals who exerted greater levels of effort and performed better during the LNS task—which in turn appears to be associated with lower perceptions of task demands—were more likely to voluntarily select more difficult tasks in the discounting task than those participants who engaged less strongly or successfully. This appears to be particularly true in older adults. From a SET perspective, this suggests that subjective perceptions of costs in older adults may be critical in that high perceived demands may prevent older adults from engaging in and experiencing success in the task, reducing the probability of subsequent engagement.

To provide evidence in support of this idea, we examined the extent to which our composite TLX score reflecting subjective cognitive costs predicted effort expenditure. Given that these scores were collected after experience at a specific level of task demand, we used ratings to predict engagement at the subsequent level of demand (e.g., ratings for memory load of 4 predicting engagement at memory load of 5) to more clearly establish a chain of causality. This, of course, necessitated excluding SBP-R data for memory loads of 3. Ratings of cognitive costs were negatively associated with engagement levels, β = −0.12, t(437) = −2.59, p = .01, with age group moderating this relationship, β = −0.12, t(437) = −2.53, p = .01. Subsequent analyses revealed that the impact of ratings of cognitive costs was significant in the older group, β = −0.23, t(437) = −3.56, p = .0004, but not in the young group, β = −0.003, t(437) = −0.04, p = .97. This supports the notion that task perceptions are preemptively influencing engagement for older adults.

Discussion

The primary goal of this study was to examine how engagement with a specific activity—including experienced and perceived costs—affected young and older adults’ future willingness to engage in that activity. Whereas previous studies have established a clear link between costs and engagement in cognitive activities, this research typically involved assessments of costs and engagement in different contexts. The present study provided a more nuanced understanding of how perceived and experienced costs predict engagement within the same context.

Prediction of Engagement

Our particular interest was in how responses associated with performance of a specific cognitively demanding task shaped individuals’ subsequent decisions to engage in that same task. We hypothesized that experienced cognitive costs (measured by SBP responses), subjective perceptions of costs, and performance would all be related to the objective demands of the task, particularly for older adults. We further hypothesized that these three factors associated with task-specific involvement would predict engagement decisions—as assessed by subjective values derived from the effort-discounting task—with the impact of these factors increasing with age. The results supported these predictions. More specifically, those who performed better on the task and viewed it as less demanding were more willing to engage in more difficult versions of the task, with these effects being stronger in the older than in the young group. Somewhat unexpectedly, those exhibiting higher levels of engagement—reflecting effort mobilization associated with active coping (e.g., Obrist, 1981)—also were more willing to do so. If effort is construed in terms of costs (e.g., Hess, 2014), then this result seems counterintuitive. Note, however, that in previous studies where such costs were observed to be negatively associated with engagement patterns (e.g., Hess et al., 2018) or positively associated with subjective task difficulty (e.g., Hess et al., 2016), test instructions were designed to promote high levels of engagement on the part of all participants. This was done by emphasizing the perceived benefits of engagement by, for example, heightening self-presentation concerns or emphasizing the benefits of engagement on cognitive health. This encouraged participants to engage resources to maximize performance, with the observed between-person variation in SBP responses attributed to individual differences in the effort necessary to successfully perform the task. In the present context, no such instructions were given, potentially reducing the perceived benefits and, concomitantly, lowering the ratio of benefits to costs and encouraging disengagement. Additionally, subjective perceptions of task demands appeared to be the primary determinants of engagement levels. Specifically, participants who viewed the task as difficult were less likely to expend effort and performed poorly, which in turn decreased their subsequent willingness to voluntarily engage in cognitively demanding activities. As expected, this selectivity, based in responses to perceived costs, was particularly evident in the old group. Thus, in the present study, the positive association between effort expenditure and willingness to perform a difficult task reflects the positive impact of previous engagement with the task.

Similar to Westbrook and colleagues (2013), we found an effort-discounting task to be useful in better understanding factors underlying older adults’ patterns of engagement. In both studies, older adults demonstrated greater reluctance than younger adults to engage further in a cognitively demanding version of the task they had just performed. The present study, however, expanded on the Westbrook et al. analysis through use of a different task and by testing both young and older participants across the same levels of task demands. We also examined the factors that were predictive of responses in the discounting task, as reflected in subjective values assigned to different levels of task demands. Together, this permitted a more sensitive analysis of selection patterns by allowing us to explicitly examine the links between specific responses at each level of task demands with subjective values assigned to those demands. This analysis demonstrated that it was not just an age-related increase in the difficulty associated with objective task demands that affected task selection in the discounting task, but also the differential weighting of subjective perceptions of demands. Interestingly, these perceptions were not only associated with assignment of subjective values, but also influenced actual engagement patterns (i.e., SBP responses) during initial exposure to the letter-number sequencing task.

Aging Stereotypes

A second important goal of the present study was to examine the impact of negative aging stereotypes on both engagement and the factors predicting it. Inconsistent with some past research (e.g., Zafeiriou & Gendolla, 2017), priming a negative stereotype had a small, but significant impact on subjective perceptions of task demands in both age groups. Interestingly, the effect was in the opposite direction to that expected: ratings of cognitive costs were lower in the negative stereotype condition than in the control condition. This effect was accompanied in older adults by a similar trend in effort expenditure. Taken together, this may suggest a pattern of older adults distancing themselves from the negative characterization of their age group, and disengaging from the task. On the surface, the lower levels of effort expenditure in the negative stereotype condition in the older group appears inconsistent with previous work by Hess et al. (2019), where the opposite trend was observed. However, this may once again relate to the absence of conditions designed to optimize motivation in the present study in that previously reported stereotype activation effects were primarily evident when motivation was high. This suggests that aging stereotypes may influence effort mobilization most when incentives are present to encourage engagement and optimal performance, with participants potentially reacting to the negative implications of aging stereotypes by increasing levels of engagement. In contrast, when incentives for performance are low, as in the present situation, older adults may react to these same implications by disengaging from the task, viewing it is not worth their effort. (See Zafeiriou & Gendolla [2017] for a similar finding.)

Our interest was in how stereotype activation affected the weighting of responses associated with performance-related responses in making decisions to engage in a cognitively demanding task. As predicted, we found that the activation of a negative aging stereotype exacerbated the influence of costs associated with task performance on such decisions, but only in the young adults. Specifically, poorer performance and higher subjective perceptions of demands were both associated with lower subjective values, but the influence of these factors was disproportionately greater following activation of a negative aging stereotype. Although we failed to replicate the finding by Zafeiriou and Gendolla (2017) that stereotype activation led to lower engagement by young adults under low incentive conditions, these findings regarding subjective value are consistent with their general perspective. Specifically, they hypothesized that activation of an aging stereotype and associated beliefs regarding age-related reductions in ability—and associated implicit perceptions of increased task difficulty—would lead to reduced engagement when the motivation to engage was low.

Somewhat surprisingly, stereotype activation was not associated with differential weighting of factors associated with task-related responses in the older group. This again may be related to the absence of instructions designed to promote motivation. As noted by Hess et al. (2019), this also highlights the fact that the impact of aging attitudes and stereotypes on older adults’ engagement patterns are not straightforward, with contextual and personal factors moderating their influence. It might be argued that our decision to contrast a non-stereotype control condition with a negative stereotype control was not as effective at demonstrating stereotype activation effects as a manipulation contrasting positive versus negative stereotypes. However, the mean ERA score of the older adults in our study—2.7 on a possible range of 1 to 4—suggests that participants had a relatively positive view of aging, essentially creating a positive backdrop in the control condition against which to meaningfully compare activation of a negative stereotype. It might also be argued that the impression task used in this study was not effective at priming age stereotypes. Whereas our data do not permit us to draw conclusive evidence of this, we would note that (a) participants in the negative stereotype condition did have negative impressions of the persons used as stimuli, and (b) similar tasks used in previous research (e.g., Hess et al., 2019; Kotter-Grühn & Hess, 2012; Zafeiriou & Gendolla, 2017) have resulted in stereotype-consistent priming effects. We also note that previous research (Hess et al., 2018) has found that a priming manipulation similar to that used here had similar engagement effects to those associated with negative beliefs about aging. Future attempts at replication using different priming methods, however, would certainly be useful in addressing these issues.

Conclusions

The current study demonstrated support for selective engagement theory (Hess, 2014) in several ways. Consistent with expectations, both subjective and objective measures of cognitive costs related to future willingness to engage cognitive resources, with their effects being particularly salient for the older adults. This supports the idea that age-related increases in the costs associated with activity engagement will negatively impact our willingness, or motivation, to engage our cognitive resources. Such effects should be particularly evident at high levels of task demands. The study expands upon previous work investigating relationships between costs and activity by examining this relationship within the same activity context. The ability to measure objective task demands and associated responses, and then to relate these factors to decisions to engage in the same task in the future, enabled us to provide a more precise accounting of how costs are translated into selection processes relating to participation in cognitively demanding activities. The use of the effort-discounting task also enhanced our ability to test SET-based predictions by permitting observation of selection processes within a controlled laboratory context. Thus, rather than just relying on, for example, changes in effort expenditure across levels of task demands to test the prediction that aging negatively affects engagement levels when costs are high (e.g., Ennis et al., 2013), we were able to evaluate and verify the same predictions by assessing participants’ explicit choices to engage.

Interestingly, the current findings also align with a growing body of research (e.g., Hess et al., 2016) which has found that—particularly for older adults—subjective perceptions of task demands are important for predicting later engagement, potentially even more so than objective indicators of task demands (e.g., effort expenditure). This expands the original SET-based conceptualization of costs influencing engagement as being reflective primarily of age-related changes in the effort necessary to perform a specific task.

Although the results are consistent with expectations regarding older adults, exclusion of middle-aged individuals in the current study limits the extent to which we can make general statements about adult development. For example, do the observed differences between young and older adults represent ends of a continuum? Or, alternatively, is there something unique about old age relating to, among other things, the influence of negative aging stereotypes, the operation of age-specific goals, or the increased probability of change in important support mechanisms (e.g., cortical structures)? Future research including middle-aged adults would help us to better understand the mechanisms underlying change in effort mobilization in old age and throughout adulthood.

The finding of subjective perceptions of task demands being especially important for understanding older adults’ willingness to engage in challenging but beneficial cognitive activities in daily life aligns well with recent research by Esposito, Gendolla, and van der Linden (2014). They found that subjective demands of the task partially mediated the association between self-efficacy beliefs and apathy (i.e., lack of motivation) in older adults. That is, relative to those with high self-efficacy, older adults with lower self-efficacy beliefs also viewed task demands as being greater and reported lower levels of interest and initiative. This, along with our findings suggest that beliefs about ability have important consequences for older adults’ motivation and effort mobilization, highlighting the need to understand those factors leading to maladaptive beliefs and subjective perceptions that may undermine activity engagement. On a positive note, beliefs may be relatively malleable, suggesting a potentially fruitful avenue for intervention that may prove easier than attempting to change actual cognitive costs (e.g., effort requirements) when promoting activity participation. Of further relevance to this point is a novel observation from the present research relating to the importance of gaining experience. Specifically, those older adults who exhibited the highest levels of task engagement not only performed better, but also viewed the task as less difficult than those with low engagement levels. These positive outcomes associated with task exposure subsequently led the former individuals to be more willing to engage in a challenging version of the task. This outcome is consistent with evidence that high levels of effort expenditure in a particular activity can increase the perceived value of both that activity and effort exertion in general (see Inzlicht, Shenhav, & Olivola, 2018). Thus, finding ways to help older adults overcome faulty and discouraging task perceptions may promote engagement, increasing the likelihood of successful performance and continued engagement with positive downstream effects on cognitive health.

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by NIA/NIH grant AG05552 awarded to Thomas M. Hess.

We gratefully acknowledge the assistance of Ashna Alam, Cinzia Boi, Sydney Dodson, Raina Gates, Ivey Jones, Jessica Lopez, and Claire Talbert in various phases of the project.

Footnotes

A priori power estimation for a mixed analysis of variance with two levels each of two between-participant factors and five levels of one within-participant factor determined that a total sample of 88 was needed to test for a medium effect size (d = .5) at α = .05 and power = .95.

We also included gender in the initial analyses, but no systematic effects were observed.

Parts of the results reported here were presented at the annual meeting of the Gerontological Society of America, Austin, 2019.

Contributor Information

Erica L. O’Brien, Center for Healthy Aging, The Pennsylvania State University.

Claire M. Growney, Department of Psychological and Brain Sciences, Washington University in St. Louis.

Jesse DeLaRosa, Department of Psychology, North Carolina State University..

References

- BIOPAC Systems, Inc. (2015). Acknowledge (Version 4.4.1) [Computer software]. Goleta, CA: Author. [Google Scholar]

- Brandtstädter J, & Rothermund K (2002). The life-course dynamics of goal pursuit and goal adjustment: A two process framework. Developmental Review, 22, 117–150. doi: 10.1006/drev.2001.0539 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brehm JW, & Self EA (1989). The intensity of motivation. Annual Review of Psychology, 40, 109–131. doi: 10.1146/annurev.psych.40.1.109 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cappell KA, Gmeindl L, & Reuter-Lorenz PA (2010). Age differences in prefontal recruitment during verbal working memory maintenance depend on memory load. Cortex, 46, 462–473. 10.1016/j.cortex.2009.11.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ennis GE, Hess TM, & Smith BT (2013). The Impact of age and motivation on cognitive effort: Implications for cognitive engagement in older adulthood. Psychology and Aging, 28, 495–504. doi: 10.1037/a0031255 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Esposito F, Gendolla GHE, & Van der Linden M (2014). Are self-efficacy beliefs and subjective task demand related to apathy in aging? Aging & Mental Health, 18, 521–530. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2013.856865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freund AM, & Ebner NC (2005). The aging self: Shifting from promoting gains to balancing losses. In Greve W, Rothermund K, & Wentura D (Eds.), The adaptive self: Personal continuity and intentional self-development (pp. 185–202). Ashland, OH: Hogrefe & Huber Publishers. [Google Scholar]

- Growney CM, & Hess TM (2020). Longitudinal relationships between resources, motivation, and cognitive engagement. Manuscript submitted for publication. [Google Scholar]

- Hart SG, & Staveland LE (1988). Development of NASA-TLX (Task Load Index): Results of empirical and theoretical research. Advances in Psychology, 52, 139–183. [Google Scholar]

- Heckhausen J, Wrosch C, & Schulz R (2010). A motivational theory of life-span development. Psychological Review, 117(1), 32–60. https://doi-org.prox.lib.ncsu.edu/10.1037/a0017668 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hertzog C, Kramer AF, Wilson RS, & Lindenberger U (2008). Enrichment effects on adult cognitive development: Can the functional capacity of older adults be preserved and enhanced? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 9, 1–65. doi: 10.1111/j.1539-6053.2009.01034.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM (2014). Selective engagement of cognitive resources: Motivational influences on older adults’ cognitive functioning. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 9, 388–407. doi: 10.1177/1745691614527465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, & Ennis GE (2012). Age differences in the effort and cost associated with cognitive activity. The Journals of Gerontology, Series B: Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 447–455. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr129 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, & Ennis GE (2014). Assessment of adult age differences in task engagement: The utility of systolic blood pressure. Motivation and Emotion, 38, 844–854. doi: 10.1007/s11031-014-9433-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Growney CM, & Lothary AF (2019). Motivation moderates the impact of aging stereotypes on effort expenditure. Psychology and Aging, 34, 56–67. doi: 10.1037/pag0000291 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Growney CM, O’Brien EL, Neupert SD, & Sherwood A (2018). The role of cognitive costs, attitudes about aging, and intrinsic motivation in predicting engagement in demanding and passive everyday activities. Psychology and Aging, 33, 953–964. doi: 10.1037/pag0000289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hess TM, Smith BT, & Sharifian N (2016). Aging and effort expenditure: The impact of subjective perceptions of task demands. Psychology and Aging, 31, 653 – 660. doi: 10.1037/pag0000127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hultsch DF, Hertzog C, Small BJ, & Dixon RA (1999). Use it or lose it: Engaged lifestyle as a buffer of cognitive decline in aging? Psychology and Aging, 14, 245–263. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.14.2.245 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Inzlicht M, Shenhav A, & Olivola CY (2018). The effort paradox: Effort is both costly and valued. Trends in Cognitive Sciences, 22, 337–349. doi: 10.1016/j.tics.2018.01.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jersild AT (1927). Mental set and shift. Archives of Psychology, 14 (No. 89), 81. [Google Scholar]

- Jopp D, & Hertzog C (2010). Assessing adult leisure activities: An extension of a self-report activity questionnaire. Psychological Assessment, 22, 108–120. doi: 10.1037/a00176622 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Katzman R, Brown T, Fuld P, Peck A, Schechter R, & Schimmel H (1983). Validation of a short Orientation-Memory-Concentration Test of cognitive impairment. The American Journal of Psychiatry, 140, 734–739. doi: 10.1176/ajp.140.6.734 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kotter-Grühn D, & Hess TM (2012). The impact of age stereotypes on self-perceptions of aging across the adult lifespan. The Journals of Gerontology Series B, Psychological Sciences and Social Sciences, 67, 563–571. doi: 10.1093/geronb/gbr153 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lang PJ, Bradley MM, & Cuthbert BN (2008). International affective picture system (IAPS): Affective ratings of pictures and instruction manual. Technical Report A-8. University of Florida, Gainesville, FL. [Google Scholar]

- Lezak MD, Howieson DB, Loring DW, Hannay HJ, & Fischer JS (2004). Neuropsychological assessment (4th ed.). New York, NY, US: Oxford University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Minear M, & Park DC (2004). A lifespan database of adult facial stimuli. Behavior Research Methods, Instruments, & Computers, 36, 630–633. doi: 10.3758/BF03206543 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Obrist PA (1981). Cardiovascular psychophysiology: A perspective. New York: Plenum. doi: 10.1007/978-1-4684-8491-5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Psychology Software Tools, Inc. [E-Prime 3.0]. (2016). Retrieved from https://www.pstnet.com.

- Queen TL, & Hess TM (2018). Linkages between resources, motivation, and engagement in everyday activities. Motivation Science, 4, 26 – 38. doi: 10.1037/mot0000061 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sarkisian CA, Steers WN, Hays RD, & Mangione CM (2005). Development of the 12-item Expectations Regarding Aging Survey. The Gerontologist, 45, 240–248. doi: 10.1093/geront/45.2.240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- SAS Institute. (2013). SAS (Version 9.4). Cary, NC: SAS Institute, Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Schooler C, & Mulatu MS (2001). The reciprocal effects of leisure time activities and intellectual functioning in older people: A longitudinal analysis. Psychology and Aging, 16, 466–482. doi: 10.1037/0882-7974.16.3.466 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Smith GE (2016). Healthy cognitive aging and dementia prevention. American Psychologist, 71(4), 268–275. doi: 10.1037/a0040250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stroop JR (1935). Studies of interference in serial verbal reactions. Journal of Experimental Psychology, 18, 643–662. doi: 10.1037/h0054651 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ware JE Jr. (1993). SF-36 Health Survey. In Maruish ME (Ed.), The use of psychological testing for treatment planning and outcomes assessment (pp. 1227–1246). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum. [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (1997). Wechsler Adult Intelligence Scale. New York, NY: Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Westbrook A, Kester D, & Braver TS (2013). What is the subjective cost of cognitive effort? Load, trait, and aging effects revealed by economic preference. PLoS One, 8, e68210. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0068210.t004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wright RA (1996). Brehm’s theory of motivation as a model of effort and cardiovascular response. In Gollwitzer PM & Bargh JA (Eds.), The psychology of action: Linking cognition and motivation to behavior (pp. 424–453). New York: Guilford. [Google Scholar]

- Zafeiriou A, & Gendolla GHE (2017). Implicit activation of the aging stereotype influences effort-related cardiovascular response: The role of incentive. International Journal of Psychophysiology, 119, 79–86. doi: 10.1016/j.ijpsycho.2017.01.011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]