Abstract

This study reviewed the methodology and findings of 44 peer-reviewed studies on psychosocial risk factors associated with mental health outcomes among undocumented immigrants (UIs) in the United States. Findings showed a considerable advancement over the past seven years in the methods and measures used in the included studies. Nonetheless, there is a need for continued methodological rigor, innovative study designs, greater diversity of samples, and in-depth exploration of constructs that facilitate resilience. Identifying avenues to reduce risk in this population is essential to inform intervention and advocacy efforts aimed at overcoming distress from the current U.S. anti-immigrant and socio-political climate.

Keywords: Undocumented, Immigrant, Mental health, Stress, Latinxs

1. Introduction

Undocumented immigrants (UIs) comprise a considerable portion of the U.S. population. A recent study using advanced demographic modeling suggests that the current number of UIs in the U.S. is nearly double that of previous estimates, approximating the current U.S. undocumented population to be 22.1 million (Fazel-Zarandi et al., 2018). As UIs establish their families in the U.S., they become settled and less likely to return to their countries of origin (Passel et al., 2014). Unfortunately, the longer these immigrants live in the U.S., the more at-risk they are for diminished health outcomes given the constant and chronic stressors that they face, including socioeconomic disadvantage, harsh living conditions, demanding work schedules, stigmatization and discrimination, constant fear of deportation, and limited healthcare access, among many other factors contributing to adversity (Garcini et al., 2016). Over the past seven past years, the socio-political climate in the U.S., which has been characterized by prevalent anti-immigrant rhetoric, policies and actions, has contributed to increase distress, fear and distrust among undocumented communities (Garcini et al., 2020). For instance, in 2017, the Trump administration announced plans to rescind the Delayed Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program, which provides temporary protected legal status to undocumented youth who were brought to the U.S. as children, (Venkataramani and Tsai, 2017). Most recently, UIs have been disproportionately affected by the economic, social, and health consequences of the current coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic; many have lost their jobs and are being prevented from accessing medical care or relief packages (Garcini et al., 2020). Also, there has been a surge in the number of deportations of UIs at the U.S.-Mexico border, along with increased stigmatization that portrays these immigrants as agents of disease and as a risk to U.S. public health (Garcini et al., 2020). The aforementioned context places UIs and their families at an increased risk for diminished health outcomes and its negative social and economic consequences.

Although approximately 66% of UIs have lived in the U.S. for more than a decade, the legal barriers of their documentation status have inhibited research with this population (Krogstad et al., 2019). Results from a previous literature review examining the mental health of UIs in the U.S. underscored a need for more robust research on this area of study (Garcini et al., 2016). A need for studies to better understand the effect of contextual stressors on the health of UIs over time has been highlighted, along with a need for studies that use random sampling and more diverse samples of UIs to make more general inferences and less biased conclusions about this at-risk population (Garcini et al., 2016). Likewise, there is a need for studies using well-established measures to assess outcomes of interest, as well as for studies addressing the effect of culture and normative cultural factors (e.g., values, beliefs) on the mental health of UIs (Garcini et al., 2016). Moreover, studies with strong methodological rigor across different fields of study could help clarify the health risks and related complications of living undocumented, which is needed to inform interventions, advocacy, and policy efforts, as well as best practices among professionals that come into contact with this population.

2. Purpose of review

Given drastic changes in the U.S. social, political and economic climate that pertain to immigration over the past seven years, this paper aims to provide an update to a previous systematic review of studies assessing psychosocial risk factors influencing the mental health of UIs in the U.S (Garcini et al., 2016). Specific aims of this review are to: (a) describe population and setting characteristics, as well as methodologies recently used (over the past seven years) to study the mental health of UIs; (b) summarize relevant themes/constructs that influence their mental health; (c) provide insight regarding mental health risks for UIs within the current U.S. socio-political context; (d) evaluate recent findings in light of previous studies and identify gaps in the literature; and (e) provide recommendations for moving this field forward.

3. Methods

The methods used in this review are informed by guidelines from the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA), as well as from a previous review on the topic (Garcini et al., 2016, Liberati et al., 2009). The present review includes peer-reviewed studies reporting quantitative and/or qualitative data on mental health outcomes of UIs since May 2014 until April 2021. Criteria for included studies were: (a) that the study was published in English; (b) that it clearly specified the inclusion of UIs adults living in the U.S. or having recently lived in the U.S. as undocumented (i.e. was not inferred from the results section); and (c) that it included the study and assessment of mental health and/or an associated psychosocial risk factor in this population. Excluded from this review were dissertations, commentaries, book/historical reviews, case studies, theoretical papers, discussion of program development, and presentations of clinical/counseling guidelines.

Similar to the previous review, a literature search using multiple databases (i.e., CINAL, ERIC, Medline, and PsycInfo) was done to identify relevant studies. Our search focused exclusively on peer-reviewed studies. Given variations in the terms used to describe UIs (e.g., illegal immigrants), the search criteria included the broad term migrant, refugee, immigrant OR immigration, as well as other comprehensive terms to facilitate screening of a wide range of studies that included UIs.1

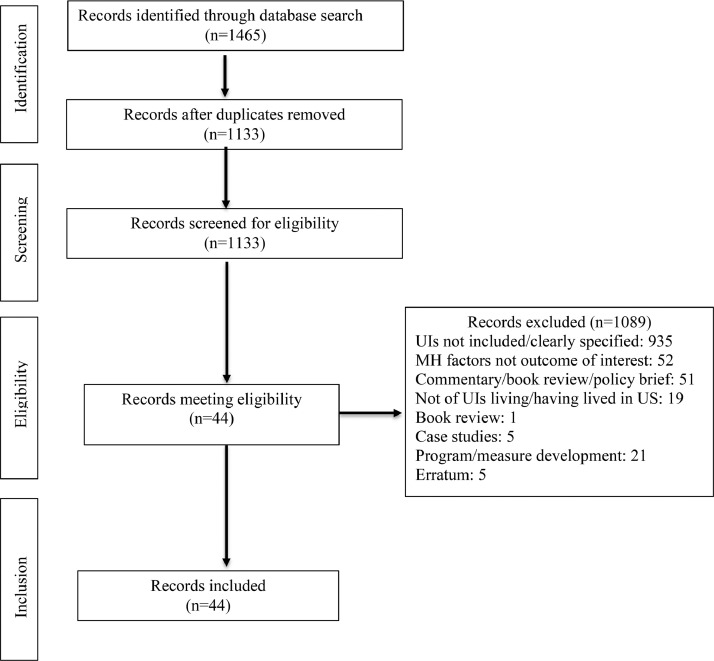

Our initial search found 1465 articles. Following the removal of duplicates (n = 332), 1133 studies were screened. Titles, abstracts, and in some cases the complete text were reviewed to determine eligibility. From the articles reviewed, 44 articles met eligibility criteria and were included (See Fig. 1). A data abstraction form to be used in coding the studies was created based on a previous literature review (Garcini et al., 2016). Information on study design and methodology, purpose of the study, sample characteristics, themes/constructs assessed, measures used, summary of findings, and limitations of the study were abstracted from eligible studies. Studies were coded by 6 trained research assistants, followed by a group validation of the coding process. Modifications were made to each coding sheet until at least 90% inter-rater joint probability agreement was obtained. Data were entered and analyzed using SPSS V25.

Fig. 1.

Summary of article screening and eligibility

4. Results

4.1. Study design and methods

Of the 44 studies included, 65.9% were quantitative (n=29), 20.5% were qualitative (n=9), and 13.6% were mixed methods studies (n=6) (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Study design characteristics

| Quantitative Studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design | Recruitment | Mode of Data Collection | Data Source | Year of Data Collection & Location | Response/ Retention/ Cooperation Rate |

| Beatrice et al., 2016 (Beatrice and Soler, 2016) | Retrospective | Existing records | Existing records | Secondary (Pima County Office of Medical Examiner) | NR Southwest & Central U.S. | NR |

| Berger Cardoso et al., 2016 (Berger Cardoso et al., 2016) | Longitudinal | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary (Recent Latino Immigrant Study) | NR Southeast U.S. (FL) |

91%* |

| Cano et al., 2017 (Cano et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | NR Southeast U.S. | NR |

| Cerezo et al., 2016 (Cerezo, 2016) | Cross-sectional | Community events | Face to face individual interviews & internet | Primary | NR Southwest U.S. | 60% |

| Cesario et al., 2014 (Cesario et al., 2014) | Prospective | Legal centers & shelters | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | NR Midwest U.S. | 96%* |

| Cobb et al., 2016 (Cobb et al., 2016) | Cross-sectional | Churches & community venues | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | NR Midwest U.S. | NR |

| Cobb et al., 2017 (Cobb et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | Churches & community venues | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | NR Midwest U.S. | NR |

| Cobb et al., 2019 (Cobb et al., 2019) | Cross-sectional | Churches & community venues | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2016 Midwest U.S. | NR |

| Cyrus et al., 2015 (Cyrus et al., 2015) | Prospective Longitudinal | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary | NR Southeast U.S. | 90%* |

| DaSilva et al., 2017 (Da Silva et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary | NR Southeast U.S. | NR |

| Dillon et al., 2018 (Dillon et al., 2018) | Cross-sectional | Community centers, social media & health fairs | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2014 Southeast U.S. | NR |

| Finno-Velasquez et al., 2016 (Finno-Velasquez et al., 2016) | Cross-sectional | Child welfare agency records | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary (National Survey of Child & Adolescent Wellbeing) | 2009 Nationwide | 35% |

| Galvan et al., 2015 (Galvan et al., 2015) | Cross-sectional | Randomly from day labor sites | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2012 Southwest U.S. | 35% |

| Garcini, Peña, Gutierrez et al., 2017 (Garcini et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2015 Southwest U.S. | NR |

| Garcini, Peña, Galvan et al., 2017 (Garcini et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2015 Southwest U.S. | NR |

| Garcini, Renzaho et al., 2018 (Garcini et al., 2018) | Cross-sectional | Stratified Sampling from neighborhoods | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary (San Diego Prevention Community Survey) | 2009 Southwest U.S. | 23% |

| Garcini, Chen et al., 2018 (Garcini et al., 2018) | Cross-sectional | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2015 Southwest U.S. | NR |

| Hainmueller et al., 2017 (Hainmueller et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | Existing records | Existing records | Secondary (Medicaid Claims Oregon Health Authority) | 2003-2015 Northwest U.S. | N/A |

| Lee et al., 2019 (Lee et al., 2020) | Cross-sectional | Door to door recruitment in randomly selected zones | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2017 Northeast U.S. | NR |

| Levitt et al., 2019 (Levitt et al., 2019) | Longitudinal | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary (The Recent Latino Immigrant Study) | 2008-2010 Southeast U.S. | NR |

| Organista et al., 2019 (Organista et al., 2019) | Cross-sectional | Day Laborer sites & Businesses | Internet survey | Primary | 2014 Southwest U.S. | 100% |

| Quantitative Studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design | Recruitment | Mode of Data Collection | Data Source | Year of Data Collection & Location | Response/ Retention/ Cooperation Rate |

| Patler et al., 2018 (Patler and Laster Pirtle, 2018) | Cross-sectional | DACA workshops | Telephone surveys/interview | Secondary (Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Study) | 2015 Southwest U.S. | 67% |

| Rodriguez et al., 2017 (Rodriguez et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | Telephone | Telephone surveys/interview | Secondary (Pew Research Center Data) | 2007-2013 Nationwide | <50% |

| Rodriguez et al., 2019 (Rodriguez et al., 2019) | Cross-sectional | County hospitals | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2018 Southwest U.S. | 79% |

| Romano et al., 2016 (Romano et al., 2016) | Cross-sectional | Community Centers, health fairs, businesses | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary (The Latino Recent Immigrant Study) |

Prior to 2012 Southeast U.S. | 89% |

| Ross et al., 2019 (Ross et al., 2019) | Cross-sectional | Community Centers | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary (Hispanic Community Health Study of Latinos) | 2008-2011 2014-2017 Nationwide | NR |

| Sanchez et al., 2016 (Sanchez et al., 2016) | Cross-sectional | RDS | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | NR Southeast U.S. | NR |

| Young et al., 2017 (Young and Pebley, 2017) | Cross-sectional | Stratified Probability Sampling of Census Tracts | Face to face individual interviews | Secondary (Los Angeles Family and Neighborhood Study) | 2008 Southwest U.S. | NR |

| Zapata et al., 2017 (Zapata Roblyer et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | College events & Health fairs | Face to face individual interviews | Primary | NR Midwest U.S. | NR |

| Qualitative Studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design | Recruitment | Mode of Data Collection | Data Source | Year of Data Collection & Location | Response/ Retention/ Cooperation Rate |

| Benuto et al., 2018 (Benuto et al., 2018) | University | Semi-structured face to face in person & phone individual interview | Primary | 2016-2017 Southwest U.S. | 42% | |

| Brietzke et al., 2017 (Brietzke and Perreira, 2017) | Schools | Semi-structured face to face individual interview | Primary | 2006-2010 Southeast U.S. (NC) | NR | |

| Fernandez et al., 2017 (Fernández-Esquer et al., 2017) | Apartment complexes & day labor sites | Semi-structured individual & group interview | Primary | 2008 Midwest U.S. | NR | |

| Glasman et al., 2018 (Glasman et al., 2018) | Community centers | Structured individual interviews | Primary | NS Midwest U.S. | NR | |

| Hwahgn et al., 2019 (Hwahng et al., 2019) | Transgender support groups | Semi-structured face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2012 Northeast U.S. | 100% | |

| Marrs et al., 2014 (Marrs Fuchsel, 2014) | Hospitals & clinics | Semi-structured individual interviews | Primary | 2013 Midwest U.S. | NR | |

| Rodriguez et al., 2019 (Rodriguez et al., 2019) | Media content analysis | Media content analysis | Primary | 2017 –2018 Nationwide | N/A | |

| Siemons et al., 2017 (Siemons et al., 2017) | Churches, businesses, legal centers, social media, telephone | Structured group interviews | Primary | 2013 Southwest U.S. | NR | |

| Qualitative Studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design | Recruitment | Mode of Data Collection | Data Source | Year of Data Collection & Location | Response/ Retention/ Cooperation Rate |

| Sudhinaraset et al., 2017 (Sudhinaraset, 2017) | Word of mouth; Venue-based; website, social media | Semi-structured individual interviews and focus groups | Primary | 2015-2016 Southwest U.S. | NR | |

| Mixed Methods Studies | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Study Design | Recruitment | Mode of Data Collection | Data Source | Year of Data Collection & Location | Response/ Retention/ Cooperation Rate |

| Brabeck, et al., 2016 (Brabeck et al., 2016) | Cross-sectional | Churches & community venues & radio/media | Semi-structured face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2013-2014 Northeast U.S. | NR |

| Buckingham et al., 2019 (Buckingham and Suarez-Pedraza, 2019) | Cross-sectional | Churches & community venues/festivals | Semi-structured group interviews | Primary | NR Southwest & Southeast U.S. | 96% |

| Cross et al., 2020 (Benuto et al., 2018) | Cross-sectional | Churches, community venues, youth centers, & shopping malls | Semi-structured face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2016-2017 Midwest U.S. | NR |

| Gowin et al., 2017 (Gowin et al., 2017) | Retrospective | Existing records | Existing records | Secondary (Asylum U.S. Applications) | 2012 NR | N/A |

| Monico C., et al., 2020 (Monico and Duncan, 2020) | Cross-sectional | Word of mouth; gatekeeper referrals | Semi-structured face to face individual interviews | Primary | 2017- 2018 Southeast | NR |

| Vargas, et al., 2017 (Vargas et al., 2017) | Cross-sectional | Random selection of landline phones and cell phones | Structured individual phone and internet interviews | Secondary (RWJF Latino National Health and Immigration Survey) | 2015 Nationwide | 18% |

RDS = Respondent Driven Sampling; CR=Cooperation rate; NS=Not specified; NR=Not reported

*Retention rate

Studies Reporting on Quantitative Data. Of studies reporting on quantitative data (n=35), most were cross-sectional (29 of 35), with three longitudinal studies, two studies that used retrospective chart reviews, and one prospective cohort study. Of these, two studies were intervention studies; one addressing domestic violence and another focusing on abuse among immigrant women residing in shelters. Moreover, 20 of the 35 quantitative studies used primary data. Pertaining to sampling, some form of random sampling was used in 5 studies, and included multistage random sampling, randomly selecting zones or telephone numbers, stratified neighborhood sampling, stratified probability sampling, and two-stage cluster sampling. Seven additional studies used Response-Driven Sampling (RDS); a peer-to-peer recruitment that uses statistical adjustments to try and approximate random sampling.

Almost half of the quantitative studies used a theoretical framework (17 of 35), with the most common being Social Identity Theory (n=3), the Socio-Ecological Framework (n=5), and the Stress Process Model (n=3). Other models or frameworks discussed included the Minority Stress Model, Social Capital Theory, the Hispanic paradox, the Structural-Environmental Framework, and a social determinants of health approach. The majority of quantitative studies collected data using a single method. Methods used to collect quantitative data included face-to-face in-person individual interviews (77.1%), review of existing records (8.6%), telephone (8.6%), and/or internet (8.6%), and face to face group interviews (2.9%) (Table 1).

Pertaining to outcome measures, most studies used psychometrically sound measures that have been previously used with immigrant populations. The most commonly used measure to assess depression was the Center for Epidemiologic Studies Depression Scale (CES-D) (n=5), with the Generalized Anxiety Disorder 7-item (GAD-7) Scale used to assess anxiety (n=2) and the Brief Symptom Inventory (BSI) used to assess overall psychological distress (n=5). For more structured mental health diagnosis, the MINI Neuropsychiatric Interview (n=1), the Composite International Diagnostic Interview Short-Form (n=2), and the National Institute of Mental Health Diagnostic Interview Schedule for the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual (DSM) IV (n=1) have been used to assess PTSD, MDD, GAD, and substance use disorders. The PTSD Checklist has also been used to assess PTSD (n=1). The most commonly used measures to assess substance use were the Alcohol Use Disorders Identification Test (AUDIT) (n=7) and the Drug Abuse Screening Test (DAST) (n=2).

Studies Reporting on Qualitative Data. Of studies reporting on qualitative data (n=15), data was collected either through structured (3 of 15) or semi-structured (10 of 15) interviews using either individual interviews (9 of 15) or focus groups (2 of 15); two studies collected data from individual interviews and groups. One study used a review of existing records from asylum appications and another did a media content analyses from social media posts of UIs. Almost half of studies using qualitative data reported using a theoretical framework (6 of 15), with two of these studies using the Socio-Ecological Framework. Other theoretical models or perspectives used included the Ecological Model of Child Development, the Stress Process Model, the Social Constructivist Perspective, and the Social Practice Theory of Self and Identity.

4.2. Sampling and recruitment

Overall, data for the included studies was collected between 2003 and 2018, with five studies collecting data over multiple years. Twenty-seven studies occurred locally (61.4%), whereas 11 studies collected data across multiple states (25.0%). Most data were collected in the Southwest (15 of 44) and Southeast (11 of 44) U.S., followed by Midwest/Central (10 of 44), Northeast (3 of 44) and Northwest (3 of 44). Five studies were nationwide. Among studies describing the setting in which the study took place (28 of 44), most were conducted in urban areas (92.9%). Less than one-third of studies (16 of 44) provided response or retention rates, which ranged from 18% to 100%. Participants were recruited from a number of collaborating sites including churches, local businesses, legal centers, hospitals and clinics, community centers, universities or schools, shelters, employment sites, health fairs, festivals, and local events. Helpful in recruitment was the use of word of mouth, social media, phone directories, radio, media advertisement, and email. Participation varied considerably across U.S. regions, with no single region showing higher or lower participation rates. Lowest participation was reported in studies when data was collected via phone and a web survey, whereas highest participation occurred when recruitment was done in shelters or in collaboration with legal offices. Other studies reporting higher participation rates recruited participants through faith-based organizations or trusted networks. Pertaining to ethics, less than half of the studies reported the type of informed consent that was obtained (47.5%). Among those reporting on consent, most used verbal (57.9%) over written consent (42.1%).

Participant characteristics. Overall, the average age of participants in the included studies was 31 years (SD = 6.4), without much difference in mean age between documented and undocumented participants (undocumented M=32.1; SD= 6.3). Sample sizes ranged from 8 to 22,873 participants, and in most studies women were a majority of the sample. Approximately a quarter of the studies were comprised exclusively of women (22.5%), with five studies including men only (12.5%). Most studies included participants of Latinx/Hispanic origin (95.5%). Indeed, in 39 studies all participants were of Latinx/Hispanic background; one study included only participants of Asian origin. Of the studies that provided countries of origin for participants, the majority were from Mexican origin, with eight studies having participants of Cuba as the majority. Few of the studies focused on special populations including sexual minorities or transgender immigrants (n=3) and day laborers (n=3). All of the studies reported on adult outcomes, although three studies included dyads; two reported on parent-child dyads and one on parent-adolescent dyads. Of the included studies, 13 included only UIs (29.5%), whereas the rest of the studies included immigrants varying in immigration legal status. Among studies of immigrants varying in immigration legal status (31 of 44), only four described differences in demographics and related characteristics by documentation status. Of studies that described the characteristics of UIs, most included participants that had a lower than high school education, employed, and married. Of note, only 3 studies focused on recent immigrants.

4.3. Findings: mental health themes, stressors and protective factors

Findings from Studies Reporting on Quantitative Data. Mental health outcomes explored included psychological distress, depression (i.e., depressive symptoms, major depressive disorder (MDD)), anxiety (i.e., anxiety symptoms, generalized anxiety disorder (GAD), panic disorder (PD), trauma- and stressor-related disorders (i.e., post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), adjustment disorder, acute stress disorder (ASD)), substance use/abuse (i.e., alcohol and drug use), psychiatric symptoms, and self-rated mental health. One study investigated physiological stress as assessed through skeletal remains of UIs found in the desert (Beatrice and Soler, 2016). Other mental health outcomes explored were satisfaction with life, flourishing, sense of safety, fear, despair, anger, shame, health-related quality of life, self-reported health, sleep difficulties, general wellbeing, and resilience. Of note, one study explored the use of psychiatric medication in this population, specifically antidepressants and anxiolytics (Ross et al., 2019).

Comparisons to identify prevalence estimates for the aforementioned mental health outcomes are difficult given that most studies do not differentiate mental health outcomes by immigration legal status. Nonetheless, of the estimates reported, a study of UIs using population-based data found that the prevalence of MDD in this population was 14.4% [95% CI=10.2; 18.6], followed by PD (8.4%, 95% CI=5.0; 11.9) and GAD (6.6%, 95% CI=3.4; 9.8) (Garcini et al., 2017). Of note, estimates for clinical levels of depression and anxiety in other studies when using non-DSM measures of distress were higher. For instance, one study that used the CES-D to assess depression found the prevalence of depression among UIs was as high as 20% and 9% for anxiety when using the GAD-7 (Garcini et al., 2017). Pertaining to trauma, despite the high prevalence of traumatic events reported among undocumented Mexican immigrants (82%), prevalence estimates for PTSD were low (3%) (Garcini et al., 2017, Garcini et al., 2017). The prevalence of substance use among UIs varied heavily depending on the measures used, with lower estimates when using DSM diagnostic measures when compared to other screening measures. For instance, the prevalence of alcohol abuse among UIs in a study using the MINI Neuropsychiatric Interview to determine DSM diagnosis was 1.6% (Garcini et al., 2017), whereas problematic alcohol use was reported as 8.6% when using the AUDIT (Finno-Velasquez et al., 2016).

Furthermore, results showed that UIs are subjected to numerous immigration-related stressors that negatively impact their mental health. Three of the most commonly explored stressors werediscrimination, acculturative stress, and traumatic events. Among studies exploring the effect of discrimination on mental health, discrimination was significantly associated with a diminished sense of wellbeing and higher psychological distress, depressive symptoms, symptoms of PTSD, substance use, and diminished life satisfaction (Cobb et al., 2019- (Cobb et al., 2017). Similarly, an epidemiological study of 254 undocumented Mexican immigrants found that discrimination due to being undocumented was associated with higher risk of meeting criteria for a mental disorder, specifically MDD (OR = 2.57, p = .012) (Garcini et al., 2017). Pertaining to acculturative stress, higher acculturative stress was significantly associated with greater psychological distress and lower wellbeing (Da Silva et al., 2017, Dillon et al., 2018, Buckingham and Suarez-Pedraza, 2019). Traumatic events also play a large role in the mental health of UIs, with traumatic events being associated with clinical levels of psychological distress (Garcini et al., 2017). Highest prevalence of clinically significant psychological distress was reported among those with a history of domestic violence (59.0%), bodily injury (58.9%), witnessing violence to others (55.5%), material deprivation (54.9%), and injury to loved ones (52.9%). Ill health without access to proper care (OR = 2.63, 95% CI [1.21, 5.70], p = .014), sexual humiliation (OR = 2.63, 95% CI [1.32, 5.26], p = .006), and not having a history of deportation (OR = 2.38, 95% CI [1.55, 5.26], p = .035), were also associated with clinically significant psychological distress (Garcini et al., 2017). In a study among transgender immigrants, traumatic experiences were associated with greater depression, anxiety, sleep difficulties, isolation, avoidance, substance use, and suicidal tendencies (Gowin et al., 2017). Additional stressors identified were harsh working and living conditions. In a study of undocumented day laborers, harsh work and living conditions were associated with greater despair (β = −0.10, SE = 0.03, p < .01; β = −0.19, SE = 0.03, p < .001), depression (β = −0.11, SE = 0.02, p < .01; β = −0.17, SE = 0.02, p < .001), and substance abuse (β = −0.13, SE = 0.43, p < .01) (Organista et al., 2019). Also, limited access to health and social services, isolation/loneliness, exploitation/abuse, and fear of immigration enforcement were identified as salient concerns (Finno-Velasquez et al., 2016, Gowin et al., 2017, Rodriguez et al., 2017, Lee et al., 2020, Cesario et al., 2014).

Nonetheless, the high resilience of UIs is highlighted in the included studies. For instance, one study reported that when compared to their documented counterparts, UI parents reported higher occupational stress, discrimination, language difficulties, and other immigration-related challenges, yet no significant differences by immigration legal status were found in the assessed mental health outcomes (Brabeck et al., 2016). A little more than a third of quantatitive studies explored coping or protective factors to the mental health of UIs, with the most commonly studied protective factor being social support. In three studies, having greater social support was significantly associated with lower use of alcohol, lower use of illicit drugs, and lower related risk behaviors such as driving under the influence (Cano et al., 2017, Sanchez et al., 2016). Other studies found that greater social support was associated with less depressive symptoms (b = 1.40, p < .01) and higher resilience (β = 0.09, p < .05) (Lee et al., 2020, Zapata Roblyer et al., 2017). The relevance of social support to the wellbeing of UIs is also emphasized by its mediating effect on the association between social capital or greater access to community resources and lower risk of substance use (b = −0.02, 95% CI [−0.041, −0.004]) (Sanchez et al., 2016). Important to note is that different sources of social support and/or social capital may have different protective effects for UIs. A study among recent Latinx immigrants found that having greater sources of support stemming from family and friends was associated with lower risk of drinking, whereas no association was found for other sources of social support (Cyrus et al., 2015). Unfortunately, when compared to their documented counterparts, UIs reported lower levels of social support, including instrumental sources of social support such as childcare help, financial assistance, and help finding work (Lee et al., 2020, Brabeck et al., 2016, Sanchez et al., 2016). In one of the two intervention studies in this review, results showed that even after a 4-month intervention aimed at promoting resilience among abused immigrant women, participants did not report greater social support, which is of concern (Cesario et al., 2014).

Cultural values, religiosity/spirituality and ethnic identity also emerged as playing an important role in UIs’ mental health although interesting patterns emerged. For instance, a study conducted among young adult Latinx immigrants found contrasting findings as to how different aspects of the cultural value of Marianismo predicted psychological distress (Dillon et al., 2018). Specifically, beliefs supporting the role of Latina women as spiritual leaders (β = -.15, p < .05) and as virtuous and chaste (β = -.16, p < .05) were associated with less psychological distress, whereas beliefs that view Latina women as pillars of the family (β = .15, p < .05) and as subordinate and self-silencing (β = .29, p < .001) were associated with greater psychological distress (Dillon et al., 2018). Similarly, in a study of young adult Latina immigrants, negative religious coping defined as struggling with faith was found to be significantly associated with greater psychological distress (β = .30, SE = .03, p < .001); however, positive religious coping or the tendency to approach faith with comfort was not associated with psychological distress (β = -.04, SE = .04, p = .39). Another interesting finding in this study was that a high degree of negative religious coping was found to strengthen the negative effect of acculturative stress on the psychological wellbeing of these young immigrants, although this association was not found among those with a low degree of religious coping (β = .32, SE = .03, p < .001) (Monico and Duncan, 2020). Ethnic/racial group identity centrality or greater identification with one's ethnic/racial group was identified as another protective factor to the mental health of UIs. In a study of 140 UIs, greater ethnic/racial group identify centrality was found to buffer the negative effects of discrimination on their psychological wellbeing (β = 0.54, p < .001, 95% CI [0.21-0.86]) and life satisfaction of UIs (β = 0.41, p = .03, 95% CI [0.04;0.79]) (Cobb et al., 2019).

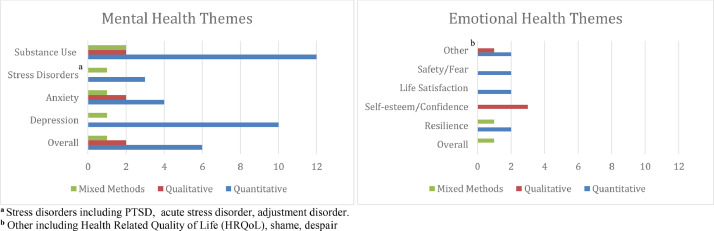

Moreover, the use of specific behavioral and cognitive strategies was also emphasized as helpful in coping with distress among UIs. For instance, in a study of young UI adults, results showed that engaging in seeking information to inform a plan of action to address a particular problem was a preferred coping strategy (Monico and Duncan, 2020). Additional effective coping strategies used by young UI adults to cope with stress included distraction (e.g., involvement in activities to avoid thinking about a problem), praying or consultation with a faith figure, and talking about problems with trusted individulas such as friend or relatives (Monico and Duncan, 2020) (Table 2, Fig. 2).

Table 2.

Participant Characteristics

| Quantitative Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Total sample size% UIs | Characteristics of UIs*(Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity) | Socio-economic Status (Income, Education) | Setting |

| Beatrice et al., 2016 (Beatrice and Soler, 2016) |

N=225 (76% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 17% women |

Income: NR Education: 38% < HS |

Rural |

| Berger Cardoso et al., 2016 (Berger Cardoso et al., 2016) |

N=527 (33% UIs) |

Mean Age= 27.0 years (SD=5) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 45% women |

Income: $ 5,042 Mean Annual Education: 18% < HS |

Urban & Rural |

| Cano et al., 2017 (Cano et al., 2017) |

N=527 (30% UIs) |

Mean Age= 27.0 years (SD=5) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 46% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

Urban |

| Cerezo et al., 2016 (Cerezo, 2016) |

N=152 (31% UIs) |

Mean Age= 30.9 years (SD=11) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 6% < HS |

NR |

| Cesario et al., 2014 (Cesario et al., 2014) |

N=106 (60% UIs) |

Mean Age= 32.9 years (SD=8) Ethnicity: Latino 79% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 56% < HS |

Urban |

| Cobb et al., 2016 (Cobb et al., 2016) |

N=122 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 33.7 years (SD=8) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 56% < HS |

Urban |

| Cobb et al., 2017 (Cobb et al., 2017) |

N=140 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 34.8 years (SD=8) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 49% women |

Income: $ 28,785 Mean Annual Education: 54% < HS |

Urban |

| Cobb et al., 2019 (Cobb et al., 2019) |

N=140 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 34.8 years (SD=8) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 49% women |

Income: $ 28,785 Mean Annual Education: NR |

NR |

| Cyrus et al., 2015 (Cyrus et al., 2015) |

N=476 (28% UIs) |

Mean Age= 27.4 years (SD=NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 46% women |

Income: $ 10,117 Mean Annual Education: 54% < HS |

NR |

| DaSilva et al., 2017 (Da Silva et al., 2017) |

N=530 (18% UIs) |

Mean Age= 28.8 years (SD=2) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 10% < HS |

NR |

| Dillon et al., 2018 (Dillon et al., 2018) |

N=530 (17% UIs) |

Mean Age= 20.8 years (SD=2) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 43% < HS |

NR |

| Finno-Velasquez et al., 2016 (Finno-Velasquez et al., 2016) |

N=842 (15% UIs) |

Mean Age= 32.2 years (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 89% women |

Income: NR Education: 4% < HS |

Urban & Rural |

| Galvan et al., 2015 (Galvan et al., 2015) |

N=725 (94% UIs) |

Mean Age= 38.5 years (SD= 8) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 0% women |

Income: 70% < $10,000 year Education: 4% < HS |

Urban |

| Garcini, Peña, Gutierrez et al., 2017 (Garcini et al., 2017) |

N=248 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 38.0 years (SD= 11) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 69% women |

Income: 66% < $24,000 year Education: 65% < HS |

Urban |

| Garcini, Peña, Galvan et al., 2017 (Garcini et al., 2017) |

N=248 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 38.0 years (SD= 11) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 69% women |

Income: 66% < $24,000 year Education: 65% < HS |

Urban |

| Garcini, Renzaho et al., 2018 (Garcini et al., 2018) |

N=393 (19% UIs) |

Mean Age= 43.7 years (SD= 17) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 73% women |

Income: NR Education: 54% < HS |

Urban |

| Garcini, Chen et al., 2018 (Garcini et al., 2018) |

N=246 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 38.0 years (SD= 11) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 69% women |

Income: 66% < $ 24,000 year Education: 65% < HS |

Urban |

| Hainmueller et al., 2017 (Hainmueller et al., 2017) |

N=22,873 (64% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 73% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

NR |

| Lee et al., 2019 (Lee et al., 2020) |

N=306 (29% UIs) |

Mean Age= 38.0 (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 53% women |

Income: 76% < $ 29,000 year Education: 37% < HS |

Urban |

| Levitt et al., 2019 (Levitt et al., 2019) |

N=474 (28% UIs) |

Mean Age= 27.0 (SD= 5) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 52% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

NR |

| Organista et al., 2019 (Organista et al., 2019) |

N=344 (92% UIs) |

Mean Age= 40.5 (SD= 11) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 0% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

Urban |

| Patler et al., 2017 (Patler and Laster Pirtle, 2018) |

N=487 (10% UIs) |

Mean Age= 24.2 (SD= 0) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 58% women |

Income: NR Education: 65% < HS |

NR |

| Rodriguez et al., 2017 (Rodriguez et al., 2017) |

N=6,012 (22% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 67% women |

Income: NR Education: 67% < HS |

NR |

| Rodriguez et al., 2019 (Rodriguez et al., 2019) |

N=1,318 (34% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 48% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

Urban |

| Romano et al., 2016 (Romano et al., 2016) |

N=467 (14% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 45% women |

Income: NR Education: 22% < HS |

Urban |

| Ross et al., 2019 (Ross et al., 2019) |

N=9,257 (11% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 52% women |

Income: 55.3% < $ 30,000 year Education: 29% < HS |

Urban |

| Sanchez et al., 2016 (Sanchez et al., 2016) |

N=467 (16% UIs) |

Mean Age= 31.8 (SD= 5) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 55% women |

Income: $ 19,962 Mean Annual Education: 29% < HS |

NR |

| Young et al., 2017 (Young and Pebley, 2017) |

N=1396 (21% UIs) |

Mean Age= 37.4 years (SD=1) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 53% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

Urban |

| Zapata et al., 2017 (Zapata Roblyer et al., 2017) |

N=114 (81% UIs) |

Mean Age= 37.3 (SD= 6) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

NR |

| Qualitative Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Total sample size% UIs | Characteristics of UIs*(Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity) | Socio-economic Status (Income, Education) | Setting |

| Benuto et al., 2018 (Benuto et al., 2018) |

N=8 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 21.5 years (SD=3) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 88% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

Urban |

| Brietzke et al., 2017 (Brietzke and Perreira, 2017) |

N=24 (58% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 58% < HS |

Urban & Rural |

| Fernandez et al., 2017 (Fernández-Esquer et al., 2017) |

N=27 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 0% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

Urban & Rural |

| Glasman et al., 2018 (Glasman et al., 2018) |

N=64 (% UIs NR) |

Mean Age= 32.6 years (SD= 8) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 0% women |

Income: NR Education: 30% < HS |

Urban |

| Hwahgn et al., 2019 (Hwahng et al., 2019) |

N=13 (% UIs NR) |

Mean Age= 38.0 (SD= 9) Ethnicity: Latino 92% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 61% < HS |

Urban |

| Marrs et al., 2014 (Marrs Fuchsel, 2014) |

N=36 (38% UIs) |

Mean Age= 38.0 (SD= 12) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 100% women |

Income: NR Education: 33% < HS |

Rural |

| Rodriguez et al., 2019 (Rodriguez et al., 2019) |

N= NR (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR Ethnicituy: NR Sex: NR |

Income: NR Education: NR |

NR |

| Siemons et al., 2017 (Siemons et al., 2017) |

N=61 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 22.4 (SD= 3) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 59% women |

Income: NR Education: 5% < HS |

Urban |

| Sudhinaraset et al., 2017 (Sudhinaraset, 2017) |

N=32 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 22.9 (SD= 3) Race: Asian 100% Sex: 50% women |

Income: 40.7% < $30,000 year Education: 0% < HS |

Urban |

| Mixed Methods Studies | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study | Total sample size% UIs | Characteristics of UIs*(Age, Sex, Race/Ethnicity) | Socio-economic Status (Income, Education) | Setting |

| Brabeck, et al., 2016 (Brabeck et al., 2016) |

N=178 (49% UIs) |

Mean Age= 36.7 years (SD=7) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 85% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

Urban |

| Buckingham et al., 2019 (Buckingham and Suarez-Pedraza, 2019) |

N=438 (36% UIs) |

Mean Age= 37.9 years (SD=13) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 61% women |

Income: NR Education: 20% < HS |

Urban |

| Cross et al., 2020 (Benuto et al., 2018) |

N=115 (44% UIs) |

Mean Age= 42.5 years (SD=5.06) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 89% women |

Income: 50.4% < $30,000 year Education: 48% < HS |

NR |

| Gowin et al., 2017 (Gowin et al., 2017) |

N=45 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= 32.0 years (SD= NR) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 0% women |

Income: NR Education: 0% < HS |

NR |

| Monico C., et al., 2020 (Monico and Duncan, 2020) |

N=13 (100% UIs) |

Mean Age= NR Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 85% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

NR |

| Vargas et al., 2017 (Vargas et al., 2017) |

N=1,493 (9% UIs) |

Mean Age= 45.9 (SD= 17) Ethnicity: Latino 100% Sex: 62% women |

Income: NR Education: NR |

NR |

NR= Not reported

Fig. 2.

Themes and outcomes of interest in the included studies

a Stress disorders including PTSD, acute stress disorder, adjustment disorder.

b Other including Health Related Quality of Life (HRQoL), shame, despair

Findings from Studies Reporting on Qualitative Data. Overall, emotional wellbeing (8 of 15) and mental health distress (7 of 15) emerged as common themes. Themes of emotional wellbeing explored included self-esteem/self-confidence, general wellbeing, resilience, positive emotions (i.e., feelings of happiness, motivation, gratefulness, safety), negative emotions (i.e., feeling of instability, despair, insecurity, hypervigilance), and interpersonal dynamics. Themes pertaining to mental health distress included anxiety, overall psychological distress, depression, post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), suicidal tendencies, and psychiatric symptoms. Substance use appeared as a theme in 3 of 15 qualitative studies. Overall, most qualitative studies provided detailed descriptions of how UIs experience distress. For instance, Fernandez and colleagues (2017) described the undocumented experience as living in a constant state of instability, insecurity, and hypervigilance that negatively affects their social environment, work, health, and living conditions (Fernández-Esquer et al., 2017).

Several qualitative studies highlighted common immigrant-related stressors that contribute to distress among UIs. Among the most commonly explored were a sense of diminished social status, poor working and living conditions, discrimination, and the language barrier. These stressors are often the result of a systematic pattern of marginalization and disadvantage and have detrimental effects on the immigrant's mental health and that of his/her family system (Brabeck et al., 2016, Cross et al., 2020). Liminality or stress associated with having a limited sense of belonging also emerged as a significant stressor, which increased feelings of rejection and isolation, while also contributed to diminished self-identity (Benuto et al., 2018). Acculturative stress, which is stress experienced by immigrants as they try to adapt to a new culture while preserving their own, was another significant stressor associated with diminished mental health (Buckingham and Suarez-Pedraza, 2019). In particular, higher levels of acculturative stress influenced mental health outcomes, such as depression and anxiety. Trauma also emerged as a stressor that negatively impacts the mental health and wellbeing of UIs, particularly in the face of limited access to health and social services due to fear of deportation, distrust from government agencies, shame, and the language barrier (Gowin et al., 2017). In a study of young UI adults, results showed that emotional trauma starting in childhood can adversely affect health and wellbeing through the life span (Monico and Duncan, 2020).

The legalization process emerged as another salient theme that influences the mental health of UIs. For instance, in a study of young undocumented adults who were candidates for DACA, findings showed a high degree of anxiety and psychological distress before and during the application process (Siemons et al., 2017). Besides the fear of being deported, these candidates experienced difficulties getting access to documentation (e.g., driver license), healthcare, jobs or educational opportunities. Similarly, in a study of Mexican transgender immigrants, symptoms of anxiety, depression, suicidal tendencies, and PTSD were associated with the legalization process (Gowin et al., 2017). This was attributed to prevalent experiences of discrimination and stigmatization, along with limited social support. Another study among immigrant parents and adolescents discussed how the immigration process and the influences of immigrant systems could negatively impact their mental health (Brabeck et al., 2016). Unauthorized parents reported finding themselves overwhelmed by occupational stress due to limited access to needed services, language barriers, and discrimination. Moreover, limited family support due to family separation was identified as a contributing factor that led to problems with childcare and finances, thus, increasing family distress. Nonetheless, despite distress from the legalization process, a study emphasized that having a sense of belonging as a result of legalization increases immigrants’ self-esteem and sense of wellbeing (Siemons et al., 2017). Similarly, another study found that having a protected immigration legal status such as DACA can improve health outcomes among UIs by increasing economic stability, opening educational opportunities, increasing access to healthcare, and empowering UIs to engage in social and community efforts (e.g., advocacy) (Sudhinaraset, 2017).

Another common theme in qualitative studies was protective and coping factors to the mental health and emotional wellbeing of UIs. Overall, the most frequently identified protective factor was social support (6 of 10). For instance, a robust social support network was found to have positive effects on identity formation (Siemons et al., 2017), along with contributing to increased self-esteem and feelings of empowerment (Marrs Fuchsel, 2014). Engament in social media to support advocacy efforts was also identified as an empowerment strategy often used by young UIs adults (Rodriguez, 2019). Support networks, such as extended families, were also found to be protective against sexual and substance use risk behaviors (Glasman et al., 2018). However, although having a sense of obligation towards family responsibilities can contribute to having an increased sense of purpose and meaning among UIs, sometimes having too many financial and caregiving family responsibilities contributes to distress in this population (Siemons et al., 2017, Brietzke and Perreira, 2017). Furthermore, social support was identified as a powerful tool to advance the social ladder. For instance, a study among adolescent immigrants and their parents found that those who coped with stress by seeking social support were better positioned to pursue upward socioeconomic opportunities when compared to those that preferred using avoidance to escape stressful situations (Brietzke and Perreira, 2017). Two additional protective factors identified were an ability for cognitively reframing experiences of adversity, as well as finding a sense of purpose and meaning in the immigration experience (Monico and Duncan, 2020). In a study of Latinxs who immigrated to the U.S. as children and remained undocumented during their childhood, many immigrants reframed their difficulties as a catalyst for personal growth and as motivation to live a better life (Benuto et al., 2018). From a developmental perspective, a study among adolescent immigrants and their parents emphasized that having a sense of purpose and building a positive self-esteem is helpful to foster healthy development and adjustment while growing up undocumented (Brietzke and Perreira, 2017). Moreover, another study found that as their self-esteem increases, UIs gain an increased focus on targeted goals along with an increased ability for decision-making (Marrs Fuchsel, 2014).

5. Discussion

Over the past seven past years, the US socio-political climate has been characterized by prevalent anti-immigrant rhetoric, policies and actions that have increased distress, fear and mistrust among undocumented communities. This review aimed to summarize what we know and what we need to know about the mental health of UIs, including evaluating the quality of existing studies, in order to move forward this important field of study. This knowledge is essential to inform intervention development, as well as much needed advocacy and policy efforts.

Consistent with prior studies, studies in this review documented psychological distress as a prevalent concern among UIs, with some of these studies providing the first population-based estimates that highlight the extent to which depression, anxiety, and trauma-related distress affect this population. A noticeable trend in the included studies is an increase in the emphasis placed on the study of emotional wellbeing constructs that are important to better understand how the socio-political context influences the mental health of UIs. For instance, wellbeing outcomes explored in the included studies, such as self-esteem/self-confidence, sense of flourishing, motivation, gratefulness, perceptions of safety, and life satisfaction are helpful to provide insight as to how the social context of living undocumented influences these immigrants’ sense of self and of the world around them, which in turn contributes to distress. The study of the aforementioned wellbeing constructs in the context of mental health promotion for UIs is essential in several ways. First, facilitating an understanding of the effect of the socio-political context on the emotional wellbeing of UIs is important to avoid pathologizing the immigrant experience of these marginalized populations and to reduce stigmatization. UIs often lack control over harsh and uncertain social and political environments that may negatively impact their wellbeing, thus increasing risk for diminished mental health. Second, learning how context can influence their wellbeing provides valuable information for the development of strength-based approaches that can help UIs remain strong in the face of adversity. Equally important is that this information is crucial to support advocacy efforts aimed at promoting the adoption of policies that can create safer and better social environments for UIs. Additional studies should continue to explore how wellbeing constructs, such as sense of purpose, meaning making, self-efficacy, and valued-based living, may be relevant mediators through which socio-political environments influence mental health outcomes among UIs.

Pertaining to immigration-related stressors, findings from this review are consistent with past research and emphasize discrimination, limited resources, intra- and inter-personal conflict, acculturative stress, and exploitability as stressors commonly faced by UIs. Having a history of traumatic events also was emphasized as a prevalent stressor, which increases risk for re-traumatization and diminished health outcomes, including impairment in functional ability. Developing a better understanding of the short- and long-term effects of the aforementioned stressors on the wellbeing of UIs is needed, including identifying protective factors that can ameliorate their negative health consequences. This information is essential to inform culturally and contextually sensitive interventions. Important to emphasize is the compounded effect that the aforementioned stressors may have on the mental health of UIs when experienced simultaneously and under daring circumstances such as the current U.S. anti-immigrant climate and the COVID-19 pandemic. Future studies are needed to help document the compounded effect of multiple stressors on the mental health of UIs within the current socio-political and health context. Also, given recent trends for the need to understand the mind-body connection and long-lasting health effects of stress, including identifying how distress from the undocumented experience may get under the skin of UIs to increase disease risk, future studies should focus on studying the interplay between physical and mental health in this population along with factors that may ameliorate such risks.

A novel trend in some of the included studies was exploration of the effect of the legalization process on the mental health of UIs and their families. The findings highlight the stressful nature of this process, particularly in recent years when uncertainty predominates and rapid changes in policy and laws are taking place. However, the findings also emphasize the health benefits experienced once UIs obtain documentation, including having a greater sense of belonging and social support, as well as far-reaching positive consequences that extend beyond the UI to their families. Future studies should aim to identify factors that can help UIs cope with stress during the legalization process and additional information is needed to understand the short- and long-term health effects of experiencing stress during legalization. Longitudinal studies may be appropriate for studying the effects of the legalization process, as following participants throughout their experience of legalization can provide comprehensive information about the process in relation to other aspects in their life and compounded stressors, including their socioeconomic status, acculturation process, immigration-related distress, and overall wellbeing, among others. Importantly, further research should continue to document the health benefits of legalization, which is needed to inform advocacy and policy efforts.

Importantly, this review identified advancements in the study of protective and coping factors to the mental health of UIs. First, we noticed an increase in the identification and study of specific aspects of protective factors within broader constructs that may facilitate the coping process among UIs. For instance, a study identified specific types of religious coping that are effective in coping with immigration-related distress (Da Silva et al., 2017, Dillon et al., 2018). This information is essential to facilitate the development of effective culturally and contextually sensitive interventions that can address specific protective factors most relevant to the undocumented experience. Another important development was identifying pathways or providing explanations as to how certain protective factors contribute to the emotional wellbeing of UIs beyond ameliorating distress. For example, a study identified social support as a powerful tool to advance the social ladder (Brietzke and Perreira, 2017). Future studies should continue to identify and explain how specific cognitive and behavioral aspects of relevant protective factors may facilitate or impair social advancement among UIs given that a sense of diminished social status is associated with increased distress in this population (Brabeck et al., 2016). Moreover, relevant protective factors in need of further study include types and sources of social support, cultural factors (e.g., identify, pride, values), and dispositional attributes (e.g., optimism, creativity, resourcefulness, complacency, tenacity) that may help build resilience in the face of adversity. Understanding protective factors could serve to further inform intervention and advocacy efforts specifically tailored to meet the needs of this at-risk immigrant population.

Advancing this field of study requires the use of methodological rigor and advanced research designs. Findings from this review support considerable advancement over the past seven years in the methods and measures used to study the mental health of UIs in the U.S. For instance, greater efforts have been made to incorporate random recruitment of participants through different methods, as well as systematic peer-to-peer recruitment strategies (e.g., RDS), which is essential to reduce selection biases and to needed to improve the generalizability of findings. Also, our findings highlight that most effective to facilitate recruitment of UIs is the identification of trusted networks (e.g., faith-based communities, non-profit immigrant organizations) and the collaboration with community partners, given the high mistrust that prevails in immigrant communities due to the current U.S. socio-political climate. Likewise, the use of psychometrically sound clinical measures previously validated with immigrant populations to assess outcomes of interest was prevalent, which facilitates comparisons with other U.S. populations as to provide greater insight into risk levels and areas of need.

Nonetheless, to keep moving this field forward, the need for continued methodological rigor and innovative study designs continues. For instance, prospective cohort studies that can follow UIs facing different stressors and adversity over time would provide valuable information to determine how different contextual experiences and access to resources can affect long-term health outcomes for this population. Likewise, an increase in the use of mixed methods that facilitate the systematic integration of qualitative and quantitative data is important to provide a deeper meaning and understanding of the effect of context on the wellbeing of UIs. In this regard, incorporating multiple sources of data, such as ethnographic data, existing records, or individual data collected from multiple informants, facilitate an understanding of compounded issues faced by UIs and mixed-status families, as well as increase the reliability of findings. Another key aspect of study design that is needed is the use of innovation in the collection and measurement of data, such as through the use of technology and electronic media. For instance, the use of Personal Digital Assistants (PDAs) or Short Message Services (SMS) are valuable tools that could help collect information in real time about the daily life experiences of UIs and how these experiences affect their wellbeing, such as their moods, thoughts, behaviors, and symptoms (Johansen and Wedderkopp, 2010). This information would allow for a more direct assessment of the effect of social circumstances and subjective experiences on mental health outcomes among this hidden population (Johansen and Wedderkopp, 2010). Likewise, incorporating the use of biomarkers to elucidate the effect of contextual stress on the health and wellbeing of UIs is needed. Face to face interviews continue to be the most widely used method for collecting data among UIs, yet in challenging times, such as the current anti-immigrant climate in the U.S. and the COVID-19 pandemic, researchers must devise new ways to incorporate technological advances into their studies to help overcome mistrust and fear prevalent in immigrant communities. Moreover, improvement in this area of research will continue as long as researchers become more diligent in providing detailed accounts of the methods, measures, and frameworks used to identify key constructs and outcomes, along with exploring and documenting differences in outcomes of interest across subgroups of UIs and/or differences across participants varying in immigration legal status.

Pertaining to sampling, studies in this review included participants of similar sociodemographic characteristics to those in previous studies. For instance, studies were primarily conducted among women, Latinx immigrants of Mexican origin, and immigrants residing in urban regions and in areas with higher concentration of UIs. Given the heterogeneity of UIs across various social determinants of health, it is recommended that future studies strive to maintain a balance between studying different subgroups of UIs, while also diversifying their samples across key sociodemographic characteristics and intersectional identities. Recent changes in the demographic profiles of UIs in the U.S. show that Mexican-origin immigrants are declining in numbers with a surge of UIs from Central America, Venezuela, and Asia; these changes call for an increase in studies of growing immigrant subgroups from Asia and Central and South America (Krogstad et al., 2019). Importantly, some of the included studies showed a disproportionate impact of immigration-related stressors on the mental health of certain subgroups of undocumented immigrants such as transgender men, day laborers and abused women (Gowin et al., 2017, Organista et al., 2019, Cesario et al., 2014). Future studies focusing on how the aforementioned intersectional identities may influence the undocumented experience, and vice-versa, are needed to elucidate risk and protective factors central to interventions and policy. Studies that could facilitate comparisons in outcomes of interest and prevalent contextual stressors among UIs residing in different settings (e.g., urban versus rural; community versus detention facilities; liberal versus conservative U.S. states) would provide insight as to the effect of different social environments and their respective laws and availability of resources on the wellbeing of UIs. Research emphasizing the heterogeneity of UIs and differences in their contextual experiences and living environments is needed to overcome existing stereotypes about this population, identify relevant risk factors and reduce existing inequities through advocacy and intervention efforts.

5.1. Limitations

This study complements previous research on the mental health of UIs by providing a more detailed analysis of methodology and updated findings, as well as proposing directions for future research. Nevertheless, this review has some limitations. Only studies in English were included, and results refer only to UIs living in the U.S.; thus, findings may not generalize to UIs in other countries. Nevertheless, some of our findings may be universal to the undocumented experience, given that this is a global phenomenon. A similar review focusing on UIs in other parts of the world would be highly informative. Also, only studies of adults were included in this review. It is important that similar reviews be done among UI youth given that they may experience different stressors to their adult counterparts, which may also lead to variations in mental health outcomes. A comparison of findings across quantitative studies was not possible given differences in the measures used and variations in reported measures of association. Finally, given differences across subgroups of UIs, making generalizations on the mental health of the entire undocumented population may be problematic.

6. Conclusion

The goal of this review was to examine recent research on the mental health stressors and outcomes experienced by UI adults in the U.S. Over the past seven years, research on the mental health of UIs has increased considerably while also improving upon the methodology used. The included studies continue to document the detrimental effects of discrimination, limited resources, intra- and inter-personal conflict, acculturative stress, and exploitability on the mental health of UIs, while also adding to our understanding of protective factors that facilitate resilience. Future studies should continue to strive for methodological rigor while documenting the effect of the aforementioned stressors compounded by the current U.S. socio-political climate and health crises. Likewise, identifying avenues to prevent harm and reduce further risk in this vulnerable, yet resilient population is essential to inform much needed intervention, policy, and advocacy efforts.

Declaration of Competing Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflict of interest.

Footnotes

Sources of funding: This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (K01 HL150247; PI: Garcini).

Terms used to select studies were undocumented OR legal status OR migrant OR refugee OR immigrant OR immigration, AND mental health OR depression OR anxiety OR psychiatric illness OR emotional health OR psychiatric disorder, AND United States.

References

- Beatrice J.S., Soler A. Skeletal Indicators of Stress: A Component of the Biocultural Profile of Undocumented Migrants in Southern Arizona. J. Forensic Sci. 2016;61(5):1164–1172. doi: 10.1111/1556-4029.13131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Benuto L.T. Being an undocumented child immigrant. Child. Youth. Serv. Rev. 2018;89:198–204. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2018.04.036. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Berger Cardoso J. Pre- to post-immigration sexual risk behaviour and alcohol use among recent Latino immigrants in Miami. Cultre Health & Sex. 2016;18(10):1107–1121. doi: 10.1080/13691058.2016.1155751. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brabeck K.M. Authorized and unauthorized immigrant parents: The impact of legal vulnerability on family contexts. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2016;38(1):3–30. doi: 10.1177/0739986315621741. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Brietzke M., Perreira K. Stress and Coping: Latino Youth Coming of Age in a New Latino Destination. J Adolesc Res. 2017;32(4):407–432. doi: 10.1177/0743558416637915. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buckingham S.L., Suarez-Pedraza M.C. “It has cost me a lot to adapt to here”: The divergence of real acculturation from ideal acculturation impacts Latinx immigrants’ psychosocial wellbeing. Am. J. Orthopsychiatry. 2019;89(4):406–419. doi: 10.1037/ort0000329. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cano M. Immigration Stress and Alcohol Use Severity Among Recently Immigrated Hispanic Adults: Examining Moderating Effects of Gender, Immigration Status, and Social Support. J. Clin. Psychol. 2017;73(3):294–307. doi: 10.1002/jclp.22330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cerezo A. The impact of discrimination on mental health symptomatology in sexual minority immigrant Latinas. Psychology of Sexual Orientation and Gender Diversity. 2016;3(3):283–292. doi: 10.1037/sgd0000172. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cesario S.K. Functioning outcomes for abused immigrant women and their children 4 months after initiating intervention. Rev. Panam. Salud Publica. 2014;35(1):8–14. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb C. Acculturation, Discrimination, and Depression Among Unauthorized Latinos/as in the United States. Cult. Divers. Ethn. Minor. Psychol. 2016;23(2):258–268. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb C.L. Perceptions of legal status: Associations with psychosocial experiences among undocumented Latino/a immigrants. J Couns Psychol. 2017;64(2):167–178. doi: 10.1037/cou0000189. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cobb C.L. Perceived discrimination and well-being among unauthorized Hispanic immigrants: The moderating role of ethnic/racial group identity centrality. Cultur Divers Ethnic Minor Psychol. 2019;25(2):280–287. doi: 10.1037/cdp0000227. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cross F.L. Illuminating ethnic-racial socialization among undocumented Latinx parents and its implications for adolescent psychosocial functioning. Dev. Psychol. 2020;56(8):1458–1474. doi: 10.1037/dev0000826. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cyrus E. Post-immigration Changes in Social Capital and Substance Use Among Recent Latino Immigrants in South Florida: Differences by Documentation Status. Journal of immigrant and minority health. 2015;17(6):1697–1704. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0191-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva N. Acculturative Stress, Psychological Distress, and Religious Coping Among Latina Young Adult Immigrants. Couns Psychol. 2017;45(2):213–236. doi: 10.1177/0011000017692111. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dillon F.R. Latina young adults' use of health care during initial months in the United States. Health Care Women Int. 2018;39(3):343–359. doi: 10.1080/07399332.2017.1388382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fazel-Zarandi MM. The number of undocumented immigrants in the United States: Estimates based on demographic modeling with data from 1990 to 2016. PLoS One. 2018;13(9) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0201193. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fernández-Esquer M.E. Living Sin Papeles: Undocumented Latino Workers Negotiating Life in “Illegality”. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2017;39(1):3–18. doi: 10.1177/0739986316679645. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finno-Velasquez M. A national probability study of problematic substance use and treatment receipt among Latino caregivers involved with child welfare: The influence of nativity and legal status. Child. Youth. Serv. Rev. 2016;71:61–67. doi: 10.1016/j.childyouth.2016.10.035. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Galvan F.H. Chronic stress among Latino day laborers. Hispanic Journal of Behavioral Sciences. 2015;37(1):75–89. doi: 10.1177/0739986314568782. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini L.M. Health-related quality of life among Mexican-origin Latinos: the role of immigration legal status. Ethn. Health. 2018;23(5):566–581. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2017.1283392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini L.M. Mental health of undocumented immigrant adults in the United States: A systematic review of methodology and findings. Journal of Immigrant & Refugee Studies. 2016;14(1):1–25. doi: 10.1080/15562948.2014.998849. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini L.M. One Scar Too Many:" The Associations Between Traumatic Events and Psychological Distress Among Undocumented Mexican Immigrants. J. Trauma Stress. 2017;30(5):453–462. doi: 10.1002/jts.22216. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini L.M. Mental disorders among undocumented Mexican immigrants in high-risk neighborhoods: Prevalence, comorbidity, and vulnerabilities. J. Consult. Clin. Psychol. 2017;85(10):927–936. doi: 10.1037/ccp0000237. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini L.M. Kicks Hurt Less: Discrimination Predicts Distress Beyond Trauma among Undocumented Mexican Immigrants. Psychology of Violence. 2018;8(6):692–701. doi: 10.1037/vio0000205. https://dx.doi.org/ [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcini L.M. A Tale of Two Crises: The Compounded Effect of COVID-19 and Anti-Immigration Policy in the United States. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy. 2020;12(S1):S230. doi: 10.1037/tra0000775. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glasman L.R. Contextual influences on Latino men's sexual and substance use behaviors following immigration to the Midwestern United States. Ethn. Health. 2018:1–18. doi: 10.1080/13557858.2018.1562051. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gowin M. Needs of a Silent Minority: Mexican Transgender Asylum Seekers. Health Promot. Pract. 2017;18(3):332–340. doi: 10.1177/1524839917692750. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hainmueller J. Protecting unauthorized immigrant mothers improves their children's mental health. Science. 2017;357(6355):1041–1044. doi: 10.1126/science.aan5893. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hwahng, S.J., et al.: Alternative kinship structures, resilience and social support among immigrant trans Latinas in the USA. 2019: 21(1), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1080/13691058.2018.1440323 [DOI] [PubMed]

- Johansen B., Wedderkopp N. Comparison between data obtained through real-time data capture by SMS and a retrospective telephone interview. Chiropractic & Osteopathy. 2010;18:10. doi: 10.1186/1746-1340-18-10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Krogstad, J., et al.: 5 facts about illegal immigration in the U.S.. Pew Research Center 2019. https://www.pewresearch.org/fact-tank/2019/06/12/5-facts-about-illegal-immigration-in-the-u-s/ (accessed 21 September 2020).

- Lee J. The Relationships Between Loneliness, Social Support, and Resilience Among Latinx Immigrants in the United States. Clinical Social Work Journal. 2020;48(1):99–109. doi: 10.1007/s10615-019-00728-w. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levitt E. Pre- and Post-Immigration Correlates of Alcohol Misuse among Young Adult Recent Latino Immigrants: An Ecodevelopmental Approach. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health. 2019;16(22):4391. doi: 10.3390/ijerph16224391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liberati A. The PRISMA statement for reporting systematic reviews and meta-analyses of studies that evaluate health care interventions: explanation and elaboration. J. Clin. Epidemiol. 2009;62(10):e1–e34. doi: 10.1136/bmj.b2700. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marrs Fuchsel C.L. "Yes, I feel stronger with more confience and strength:” Examining the experiences of immigrant Latina women (ILW) participating in the Si yo puedo curriculum. Journal of Ethnographic & Qualitative Research. 2014;9(2):161–182. [Google Scholar]

- Monico C., Duncan D. Childhood narratives and the lived experiences of Hispanic and Latinx college students with uncertain immigration statuses in North Carolina. International Journal of Qualitative Studies on Health and Well-being. 2020;15(sup2) doi: 10.1080/17482631.2020.1822620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Organista K. Working and Living Conditions and Psychological Distress in Latino Migrant Day Laborers. Health Educ. Behav. 2019;46(4):637–647. doi: 10.1177/1090198119831753. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Passel J.S. As growth stalls, unauthorized immigrant population becomes more settled. Pew Research Center, Hispanic Trends. 2014 https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2014/09/03/as-growth-stalls-unauthorized-immigrant-population-becomes-more-settled/ (accessed 21 September 2020) [Google Scholar]

- Patler C., Laster Pirtle W. From undocumented to lawfully present: Do changes to legal status impact psychological wellbeing among latino immigrant young adults? Soc. Sci. Med. 2018;199:39–48. doi: 10.1016/j.socscimed.2017.03.009. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez D. A Content Analysis of the Contributions in the Narratives of DACA Youth. Journal of Youth Development. 2019;14:64–78. [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez N. Fear of Immigration Enforcement Among Older Latino Immigrants in the United States. J. Aging Health. 2017;29(6):986–1014. doi: 10.1177/0898264317710839. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez R.M. Declared impact of the US President's statements and campaign statements on Latino populations' perceptions of safety and emergency care access. PLoS One. 2019;14(10) doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0222837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Romano E. Drinking and Driving Among Undocumented Latino Immigrants in Miami-Dade County, Florida. Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2016;18(4):935–939. doi: 10.1007/s10903-015-0305-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ross J. Association between immigration status and anxiety, depression, and use of anxiolytic and antidepressant medications in the Hispanic Community Health Study/Study of Latinos. Ann. Epidemiol. 2019;37:17–23. doi: 10.1016/j.annepidem.2019.07.007. e13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sanchez M. Drinking and Driving among Recent Latino Immigrants: The Impact of Neighborhoods and Social Support. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2016;13(11):1055. doi: 10.3390/ijerph13111055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Siemons R. Coming of Age on the Margins: Mental Health and Wellbeing Among Latino Immigrant Young Adults Eligible for Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) Journal of Immigrant and Minority Health. 2017;19(3):543–551. doi: 10.1007/s10903-016-0354-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]