Abstract

Background

Financial toxicity (FT) is a well-established side-effect of the high costs associated with cancer care. In recent years, studies have suggested that a significant proportion of those with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD) experience FT and its consequences.

Objectives

This study aimed to compare FT for individuals with neither ASCVD nor cancer, ASCVD only, cancer only, and both ASCVD and cancer.

Methods

From the National Health Interview Survey, we identified adults with self-reported ASCVD and/or cancer between 2013 and 2018, stratifying results by nonelderly (age <65 years) and elderly (age ≥65 years). We defined FT if any of the following were present: any difficulty paying medical bills, high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, food insecurity, and/or foregone/delayed care due to cost.

Results

The prevalence of FT was higher among those with ASCVD when compared with cancer (54% vs. 41%; p < 0.001). When studying the individual components of FT, in adjusted analyses, those with ASCVD had higher odds of any difficulty paying medical bills (odds ratio [OR]: 1.22; 95% confidence interval [CI]: 1.09 to 1.36), inability to pay bills (OR: 1.25; 95% CI: 1.04 to 1.50), cost-related medication nonadherence (OR: 1.28; 95% CI: 1.08 to 1.51), food insecurity (OR: 1.39; 95% CI: 1.17 to 1.64), and foregone/delayed care due to cost (OR: 1.17; 95% CI: 1.01 to 1.36). The presence of ≥3 of these factors was significantly higher among those with ASCVD and those with both ASCVD and cancer when compared with those with cancer (23% vs. 30% vs. 13%, respectively; p < 0.001). These results remained similar in the elderly population.

Conclusions

Our study highlights that FT is greater among patients with ASCVD compared with those with cancer, with the highest burden among those with both conditions.

Key Words: atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease, cancer, financial toxicity, health economics

Abbreviations and Acronyms: ASCVD, atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; BMI, body mass index; CI, confidence interval; COST, Comprehensive Score for Financial Toxicity; CRF, cardiovascular risk factor; FT, financial toxicity; OOP, out-of-pocket; OR, odds ratios

Central Illustration

Financial toxicity (FT) refers to the financial strain that patients experience while accessing health care, and has been widely researched in cancer patients (1). Used interchangeably with “financial hardship,” “financial (di)stress,” “(high) financial burden,” “economic burden,” and “economic hardship” (2), it has been reported that a large proportion of patients with cancer experience FT (3, 4, 5). This affliction is not limited to cancer diagnosis, but also manifests as the impaired health of patients following treatment and survivorship (6). These insights have also been directed toward implementation of FT-specific interventions for better screening, social support, and care for patients with cancer (7, 8, 9, 10).

Although there has been an emphasis on understanding and remedying FT in patients with cancer (3), this phenomenon has been studied less frequently among patients with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease (ASCVD). The extent of FT and how it manifests might differ between patients with ASCVD and cancer. For example, patients with cancer may have short bursts of high expenditures with chemotherapy, whereas ASCVD incurs a more chronic economic burden related to the costs of drugs, procedures, clinician visits, and hospital stays (11). The economic burden that ASCVD confers to patients and families who experience it has been described in the last few years (12, 13, 14, 15). Additionally, with prolonged survival following the diagnosis of cancer, the cardiac toxicity of some treatments, and better treatment options for ASCVD, the population of patients with simultaneous ASCVD and cancer is growing. Without the ability to pay, patients can experience financial health and non–health-related difficulties, such as difficulty paying medical bills, financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, and food insecurity, and may forego or delay care due to cost (16, 17, 18, 19). However, no studies to date have contrasted the FT incurred in patients with ASCVD and/or cancer, which are currently the 2 leading causes of death in the United States (20). The current study, using a nationally representative sample of the United States, compared the financial burden of health care on adult patients with neither ASCVD nor cancer, ASCVD only, cancer only, and both ASCVD and cancer.

Methods

Study design

We utilized 6 years of data (2013 to 2018) from the NHIS (National Health Interview Survey). The NHIS, a database compiled by the National Center for Health Statistics/Center for Disease Control and Prevention, is constructed from annual, cross-sectional national surveys that incorporate complex, multistage sampling to provide estimates on the noninstitutionalized U.S. population (21). The NHIS questionnaire is divided into 4 core components: Household Composition, Family Core, Sample Child Core, and Sample Adult Core (21). The Household Composition file collects basic information and relationship information about all persons in a household. The Family Core file collects sociodemographic characteristics, basic indicators of health status, activity limitations, injuries, health insurance coverage, and access to, and utilization of, health care services. From each family, 1 sample child and 1 sample adult are randomly selected to gather more detailed information. This study utilized the Sample Adult Core files (with relevant variables added from the Family Core files), which are supplemented with demographic and socioeconomic characteristics, health status, health care services, and health-related behaviors on the U.S. adult population (21). Because NHIS data are publicly available and deidentified, this study was exempt from institutional review board approval (22).

Study population

We used a self-reported diagnosis of coronary or cerebrovascular disease to identify patients with ASCVD. Specifically, individuals were included if they reported having coronary artery disease (“yes” to any of the following 3 questions: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had…coronary heart disease,” “…angina, also called angina pectoris,” or “…a heart attack [also called myocardial infarction]?”) and/or stroke (“yes” to the following question: “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had a stroke?”) were classified as having ASCVD. Similarly, individuals that answered “yes” to the question, “Have you ever been told by a doctor or other health professional that you had cancer or a malignancy of any kind?” were classified as having cancer. These methods of diagnosis ascertainment have been used in previous literature (12,23). For our main analyses, we included only non-elderly (≥18 to <65 years of age) adults to capture the population without universal financial protections from public insurance. As a subanalysis, we further extended our study population to elderly (≥65 years of age) adults.

Study outcomes

Financial toxicity

For the purposes of this paper, we defined FT as having any of the following: difficulty paying medical bills, inability to pay them at all, high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, food insecurity, and/or delayed/foregone care due to cost. The specific questions and definitions for each FT component are presented in Supplemental Table 1.

Difficulty paying medical bills

The following questions were used to assess the study population having “any difficulty paying medical bills”:

-

•

“In the past 12 months, did you/anyone in your family have problems paying or were unable to pay any medical bills? Include bills for doctors, dentists, hospitals, therapists, medication, equipment, nursing home or home care,” or

-

•

“Do you/anyone in your family currently have any medical bills that are being paid off over time? This could include medical bills being paid off with a credit card, through personal loans, or bill paying arrangements with hospitals or other providers. The bills can be from earlier years as well as this year.”

This approach has been previously employed in other studies and surveys (24,25). Additionally, for individuals who answered “yes” to having difficulty paying bills, a follow-up question was asked: “Do you/does anyone in your family currently have any medical bills that you are unable to pay at all?” Individuals who answered “yes” to this question were studied as a separate group—those who were “unable to pay bills at all.”

High financial distress

Financial distress was derived from 6 questions regarding the level of concern with several financial matters, including: lack of retirement funds, ability to pay medical costs of serious illness, maintaining an acceptable quality of living, ability to pay day-to-day health care costs, inability to pay monthly bills, and inability to pay rent/mortgage/housing costs (Supplemental Table 1). The questions were responded to on a 4-point scale, ranging from “not worried at all” to “very worried.” An aggregate score was created, ranging from 6 to 24, a higher score indicating increased levels of financial distress (26). Participants within the highest quartile were designated as experiencing high levels of financial distress.

Cost-related medication nonadherence

Cost-related medication nonadherence was defined as a survey responder reporting any of the following behaviors to save money in the last 12 months: skipping medication doses, taking less medicine, or delaying filling a prescription (Supplemental Table 1).

Food insecurity

Food security in the last 30 days was created based on the 10-item questionnaire as recommended by the U.S. Department of Agriculture Economic Research Service (Supplemental Table 1) (27,28), and constructed per the NHIS instructions (28). In questions about frequency of occurrence in the past 30 days, answers of ≥ 3 days were considered affirmative. A raw score ranging from 0 to 10 was calculated, with the following categories: food secure (score 0 to 2), low food security (score 3 to 5), and very low food security (score 6 to 10). For this study’s purposes, food insecurity included those who had either low or very low food security, as is common in practice (29).

Delayed/foregone care due to cost

Delayed and/or foregone care due to cost was assessed by asking individuals whether, within the past year, medical care had been delayed due to cost, or if they needed but did not receive medical care due to cost (30).

Covariates

Other covariates included in this study were age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, education, insurance status, region, cardiovascular risk factor (CRF) profile, number of chronic comorbidities, and for individuals with cancer, years since diagnosis. Categorical variables were classified as follows: 2 categories for sex; 3 categories for race/ethnicity (non-Hispanic White, non-Hispanic Black, and Hispanic); 2 categories for family income (based on percent of family income to the federal poverty limit from the Census Bureau: high/middle-income [≥200%], low-income [<200%]); 2 categories for education (some college or higher, high school/GED or less than high school); 2 categories for insurance status (insured, uninsured), and 4 categories for geographic region (Northeast, Midwest, South, and West). CRF profile was calculated by determining, via self-report, whether individuals had 1 or more of the following: diagnosis of hypertension, diabetes mellitus or high cholesterol, obesity (calculated body mass index ≥30 kg/m2), current smoker, or insufficient physical activity (based on not participating in >150 min/week of moderate-intensity aerobic physical activity, >75 min/week of vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity, or a total combination of ≥150 min/week of moderate/vigorous-intensity aerobic physical activity). Based on the presence of these individual risk factors, individuals were categorized as “poor” (≥4 CRFs), “average” (2 to 3 CRFs), and “optimal” (0 to 1 CRF) (31,32). Self-reported chronic comorbidities, including emphysema, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, asthma, gastrointestinal ulcer, arthritis (including arthritis, gout, fibromyalgia, rheumatoid arthritis, and systemic lupus erythematosus), any kind of liver condition, or “weak/failing” kidneys, were aggregated, and categorized as having 0, 1, or ≥2. For individuals with cancer, time since diagnosis was measured in years, and presented as both continuous, and categorized as ≥0 to ≤5, >5 to ≤15, and >15 years.

Statistical analysis

Chi-square tests were used to compare categorical variables, and weighted proportions were used to study prevalence. Continuous variables were reported as medians with interquartile range. Categorical variables were reported as unweighted counts with their accompanying weighted proportions (in tables), and as weighted proportions with 95% confidence interval (CI) (in figures). Further, we used linear regression to test for linear trends of the prevalence of FT measures between disease groups. Unadjusted and adjusted logistic regression models were used to measure the association between FT prevalence and disease group (neither ASCVD nor cancer, ASCVD, cancer, or both ASCVD and cancer), and were reported as odds ratios (ORs) with 95% CIs. Adjusted models included variables that have been correlated with presence and/or risk for FT (e.g., income and insurance status), or that are clinically significant (e.g., age, cardiovascular risk factors, and comorbidities). We used the Akaike Information Criterion to determine the optimal variables to include in our adjusted model. The full list of explanatory variables included age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, education, insurance status, geographic region, cardiovascular risk factor profile, and comorbidities for all outcome measures; in the case of high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, food insecurity, and foregone/delayed care due to cost, burden from medical bills was also included due to the risk of confounding. Similar models were constructed for the individual components of FT. Variance estimation for the entire pooled cohort was obtained from the Integrated Public Use Microdata Series (33). For all statistical analyses, p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant. All analyses were carried out using Stata version 16 (StataCorp, LP, College Station, Texas). All analyses were survey-specific considering the complex design of the NHIS survey.

Results

Non-elderly population

From 2013 to 2018, the NHIS total sample of non-elderly (≥18 to <65 years of age) adults was 141,826, of which 6,887 (weighted prevalence: 4.5% [95% CI: 4.4% to 4.7%]), 6,093 (weighted prevalence: 3.8% [95% CI: 3.7% to 4.0%]), and 971 (weighted prevalence: 0.6% [95% CI: 0.56% to 0.65%]) had cancer, ASCVD, and both ASCVD and cancer, respectively. This translates to 8.9, 7.5, and 1.2 million non-elderly U.S. adults yearly, respectively (Table 1).

Table 1.

General Characteristics Among Non-Elderly Adults With Cancer and/or ASCVD, From the National Health Interview Survey, 2013 to 2018

| Neither ASCVD Nor Cancer | Cancer Only | ASCVD Only | Both ASCVD and Cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sample | 127,875 | 6,887 | 6,093 | 971 |

| Weighted sample | 178,640,421 (91.1) | 8,865,357 (4.5) | 7,493,768 (3.8) | 1,173,167 (0.6) |

| Age category, yrs | ||||

| 18–39 | 61,680 (50.7) | 979 (14.3) | 717 (13.3) | 66 (7.8) |

| 40–64 | 66,195 (49.3) | 5,908 (85.7) | 5,376 (86.7) | 905 (92.2) |

| Sex | ||||

| Male | 59,431 (49.3) | 2,350 (36.2) | 3,390 (59.1) | 441 (48.7) |

| Female | 68,444 (50.7) | 4,537 (63.8) | 2,703 (40.9) | 530 (51.3) |

| Race/ethnicity | ||||

| Non-Hispanic White | 78,011 (61.7) | 5,626 (83.6) | 3,801 (64.9) | 762 (82.1) |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 17,463 (13.2) | 503 (6.4) | 1,146 (17.1) | 105 (9.3) |

| Non-Hispanic Asian | 8,184 (6.6) | 155 (2.5) | 177 (3.3) | 6 (0.5) |

| Hispanic | 22,416 (18.4) | 526 (7.5) | 838 (14.8) | 72 (8.1) |

| Family income | ||||

| Middle/high income | 77,946 (69.5) | 4,658 (77.9) | 2,724 (54.1) | 424 (54.3) |

| Low income | 42,332 (30.5) | 1,826 (22.1) | 3,059 (45.9) | 497 (45.7) |

| Education | ||||

| Some college or higher | 82,769 (64.6) | 4,777 (70.4) | 2,993 (50.2) | 543 (56.8) |

| HS/GED or less than HS | 44,652 (35.4) | 2,094 (29.6) | 3,076 (49.8) | 425 (43.2) |

| Insurance status | ||||

| Insured | 107,418 (85.3) | 6,327 (92.9) | 5,335 (87.9) | 887 (91.7) |

| Uninsured | 19,816 (14.7) | 544 (7.1) | 740 (12.1) | 79 (8.3) |

| Region | ||||

| Northeast | 20,323 (17.4) | 1,120 (17.3) | 894 (15.1) | 141 (15.8) |

| Midwest | 27,750 (22.2) | 1,602 (23.6) | 1,344 (23.6) | 213 (24.1) |

| South | 45,443 (36.3) | 2,379 (37.2) | 2,566 (42.7) | 415 (43.0) |

| West | 34,359 (24.0) | 1,786 (22.0) | 1,289 (18.6) | 202 (17.0) |

| CRF profile | ||||

| Optimal | 73,456 (61.2) | 2,952 (47.4) | 940 (17.9) | 142 (16.5) |

| Average | 41,420 (32.8) | 2,789 (41.2) | 2,637 (45.6) | 390 (45.2) |

| Poor | 8,187 (6.0) | 819 (11.3) | 2,131 (36.4) | 360 (38.3) |

| Comorbidities | ||||

| 0 | 88,643 (70.8) | 3,203 (48.3) | 2,149 (37.9) | 210 (25.0) |

| 1 | 29,926 (22.7) | 2,259 (32.8) | 1,950 (32.5) | 270 (28.6) |

| ≥2 | 9,306 (6.5) | 1,425 (18.9) | 1,994 (29.6) | 491 (46.4) |

| Years since cancer diagnosis | — | 6 (2–14) | — | 7 (2–16) |

| Years since cancer diagnosis | ||||

| 0 to ≤5 | — | 2,989 (44.7) | — | 400 (41.6) |

| >5 to ≤15 | — | 2,336 (33.8) | — | 287 (31.6) |

| >15 | — | 1,562 (21.5) | — | 284 (26.8) |

Values are n, n (%), or median (interquartile range). All p values for comparison between groups were <0.001.

ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; CRF = cardiovascular risk factor; GED = general equivalency diploma; HS = high school.

Most individuals in the non-elderly population were 40 to 64 years of age, insured, and White. Women were more likely to report having cancer, with a majority coming from middle-/high-income households and with a higher education level. In contrast, those reporting ASCVD (with or without cancer) were evenly distributed by sex, education, and income levels, although with a shift toward a more unfavorable CRF profile (Table 1). Among the non-elderly adults with cancer, the most frequently reported cancers included skin (nonmelanoma), breast, cervix, prostate, and “other” (Supplemental Table 2). Similar patterns were observed in the population that reported both ASCVD and cancer.

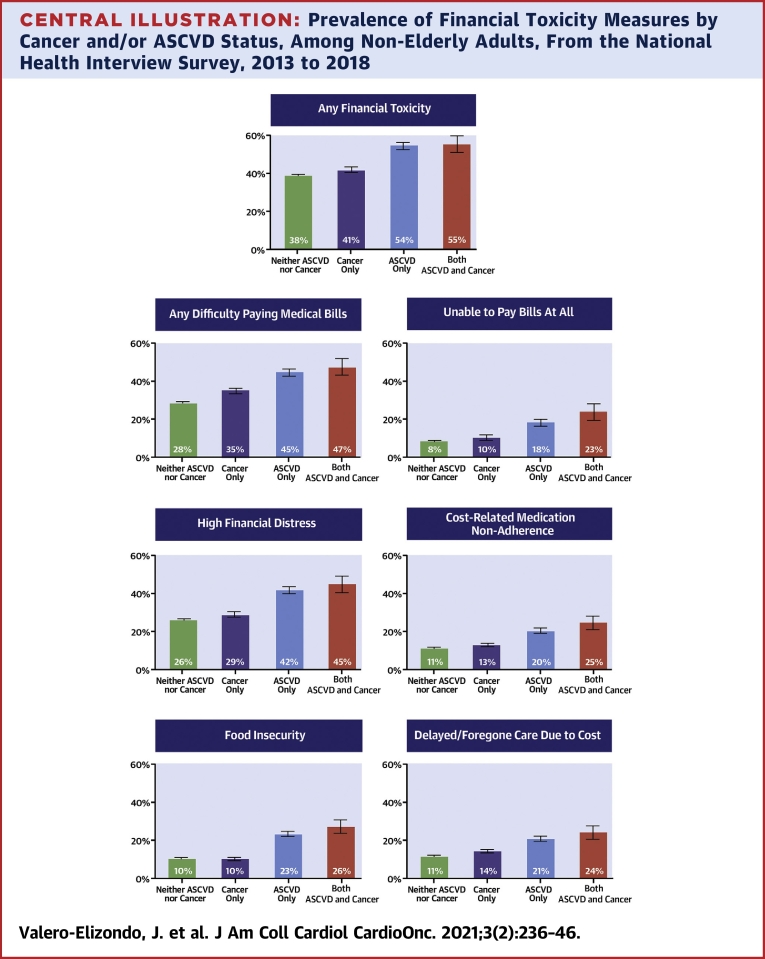

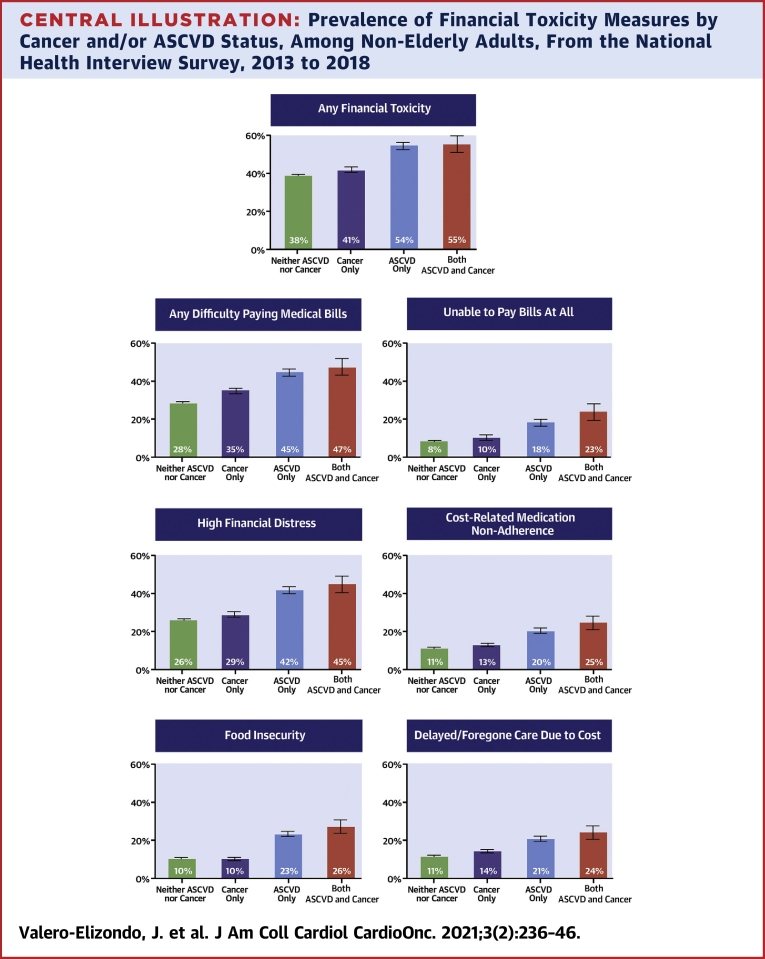

Prevalence of FT measures by underlying condition are comprehensively depicted in our Central Illustration. Any FT was present to a higher extent across disease categories from neither ASCVD nor cancer (38.3% [95% CI: 37.8% to 38.9%]), to cancer (41.0% [95% CI: 39.5% to 42.6%]), to ASCVD (54.1% [95% CI: 52.4% to 55.8%]), and both (ASCVD and cancer; 54.5% [95% CI: 50.3% to 58.7%]) (p trend <0.001) (Central Illustration). Difficulty paying medical bills was significantly higher for individuals with ASCVD (with or without cancer; 44.8% [95% CI: 43.1% to 46.5%] and 47.4% [95% CI: 43.1% to 51.7%], respectively) when compared with those with cancer (35.0% [95% CI: 33.5% to 36.6%]). When analyzing those with the highest burden from medical bills—those with an inability to pay bills at all—a statistically significant trend was also seen when comparing cancer (10.1% [95% CI: 9.0% to 11.3%]) versus ASCVD (18.2% [95% CI: 16.9% to 19.5%]) versus both (23.2% [95% CI: 19.8% to 26.8%]) (p trend <0.001). Overall, the same pattern (i.e., ASCVD and cancer > ASCVD > cancer > neither) was observed for high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, food insecurity, and delayed/foregone medical care due to cost when comparing those reporting ASCVD (with or without cancer) versus cancer (all p trend <0.001).

Central Illustration.

Prevalence of Financial Toxicity Measures by Cancer and/or ASCVD Status, Among Non-Elderly Adults, From the National Health Interview Survey, 2013 to 2018

Any financial toxicity: any difficulty paying medical bills ± unable to pay bills at all ± high financial distress ± cost-related medication non-adherence ± food insecurity ± delayed/foregone care due to cost. The p value for linear trends was <0.001 for all financial toxicity prevalence measures when comparing disease groups. Data in this figure represents weighted prevalence (bars) with 95% confidence interval (error bars). ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey.

In univariable logistic regression analysis, patients with both cancer and ASCVD had increased odds of any FT (OR: 1.93; 95% CI: 1.63 to 2.28). This was further observed in all of FT measures: any difficulty paying medical bills (OR: 2.27; 95% CI: 1.91 to 2.70), inability to pay medical bills at all (OR: 3.43; 95% CI: 2.83 to 4.16), high financial distress (OR: 2.46; 95% CI: 2.08 to 2.92), cost-related medication nonadherence (OR: 4.72; 95% CI: 3.86 to 5.78), food insecurity (OR: 3.19; 95% CI: 2.65 to 3.83), and foregone/delayed care due to cost (OR: 2.51; 95% CI: 2.08 to 3.03) when compared with patients who reported neither disease (Table 2). The presence of ASCVD with or without cancer was associated with an increased odds for all FT measures when compared with individuals with cancer, as evidenced by nonoverlapping CIs. In multivariable analysis, after adjusting for confounders including variables such as family income and insurance status, the effect sizes were attenuated but associations remained consistent and statistically significant: those with ASCVD and cancer had increased odds of being unable to pay medical bills at all, high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, and foregone/delayed medical care, when compared with those with cancer (Table 2). Of note, even though effect sizes were larger (i.e., higher ORs), there were no statistical differences between the groups with ASCVD only and both ASCVD and cancer in adjusted analyses (interaction p = 0.39). Our findings further reinforce the notion that presence of ASCVD was a key determinant of the presence and severity of FT.

Table 2.

Burden of Financial Toxicity Among Non-Elderly Adults With and Without Cancer and/or ASCVD, From the National Health Interview Survey, 2013 to 2018

| Neither ASCVD Nor Cancer | Cancer Only | ASCVD Only | Both ASCVD and Cancer | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any financial toxicity∗ | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.12 (1.05–1.20) | 1.90 (1.77–2.03) | 1.93 (1.63–2.28) |

| Model 2 | 1.12 (1.04–1.21) | 1.35 (1.25–1.47) | 1.39 (1.14–1.69) | |

| Any difficulty paying medical bills | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.36 (1.27–1.45) | 2.04 (1.91–2.19) | 2.27 (1.91–2.70) |

| Model 2 | 1.29 (1.20–1.39) | 1.53 (1.41–1.65) | 1.54 (1.27–1.86) | |

| Unable to pay medical bills | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.27 (1.12–1.45) | 2.52 (2.30–2.76) | 3.43 (2.83–4.16) |

| Model 2 | 1.29 (1.11–1.50) | 1.54 (1.38–1.71) | 2.02 (1.59–2.57) | |

| High financial distress | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.15 (1.07–1.24) | 2.04 (1.90–2.18) | 2.46 (2.08–2.92) |

| Model 2 | 1.03 (0.95–1.12) | 1.13 (1.04–1.24) | 1.26 (1.03–1.55) | |

| Cost-related medication nonadherence | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.78 (1.62–1.96) | 3.22 (2.93–3.54) | 4.72 (3.86–5.78) |

| Model 2 | 1.17 (1.04–1.31) | 1.48 (1.32–1.67) | 1.63 (1.27–2.09) | |

| Food insecurity | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 0.95 (0.86–1.05) | 2.65 (2.45–2.87) | 3.19 (2.65–3.83) |

| Model 2 | 0.95 (0.84–1.07) | 1.27 (1.14–1.42) | 1.34 (1.05–1.69) | |

| Foregone/delayed care due to cost | ||||

| Model 1 | Reference | 1.33 (1.21–1.45) | 2.08 (1.92–2.25) | 2.51 (2.08–3.03) |

| Model 2 | 1.14 (1.02–1.26) | 1.32 (1.18–1.47) | 1.61 (1.28–2.03) | |

Values are odds ratio (95% confidence interval).

Abbreviations as in Table 1.

Any difficulty paying medical bills ± high financial distress ± cost-related medication non-adherence ± food insecurity ± delayed/foregone care due to cost. Model 1: unadjusted. Model 2: adjusted for age, sex, race/ethnicity, family income, education, insurance type, geographic region, cardiovascular risk factor profile, comorbidities, and, where appropriate (high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, food insecurity and foregone/delayed care due to cost), burden from medical bills.

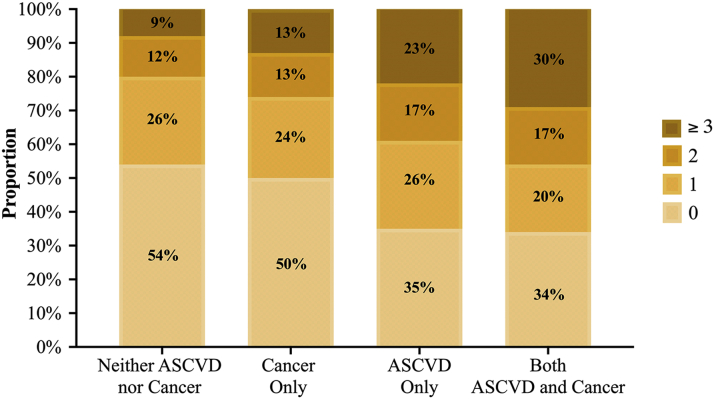

Furthermore, in a composite score of number of FT measures each individual had, we found that the prevalence of having ≥3 was 9% (≈17.2 million) among those with neither disease, 13% (≈25.3 million) among those with cancer, 23% (≈44.5 million) among those with ASCVD, and 30% (≈57.9 million) among those with both (p trend <0.001) (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Distribution of Total Burden From Financial Toxicity Measures, by ASCVD and/or Cancer Status, Among Non-Elderly Adults, From the National Health Interview Survey, 2013 to 2018

FT measures: any difficulty paying medical bills ± high financial distress ± cost-related medication non-adherence ± food insecurity ± delayed/foregone care due to cost. ASCVD = atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease; FT = financial toxicity; NHIS = National Health Interview Survey.

Elderly population

From 2013 to 2018, the NHIS total sample of elderly (≥65 years of age) adults was 48,287, of which 8,457 (weighted prevalence: 18.1% [95% CI: 17.7% to 18.6%]), 8,167 (weighted prevalence: 16.9% [95% CI: 16.4% to 17.3%]), and 3,211 (weighted prevalence: 6.8% [95% CI: 6.5% to 7.1%]) had cancer, ASCVD, and both, respectively. This translates to 8.6, 8.0, and 3.2 million elderly U.S. adults yearly (Supplemental Table 3). Virtually all patients in this age category were White and insured, and the majority were from middle/high-income households. Individuals with ASCVD (regardless of cancer diagnosis) were more likely to be men, whereas older adults (age ≥75 years) were more likely to have combined ASCVD and cancer diagnoses. Among the elderly adults with cancer, the most frequently reported cancers included breast, prostate, and skin (unknown kind). Similar patterns were observed in the population that reported both ASCVD and cancer (Supplemental Table 2).

Prevalence of FT measures by underlying condition among elderly adults are described in Supplemental Figure 1. Overall, the same pattern was observed for all FT measures as seen with non-elderly adults, although at significantly lower proportions. Individuals reporting ASCVD with or without cancer had a higher degree of difficulty paying medical bills, inability to pay at all, high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, food insecurity, and delayed/foregone medical care due to cost (Supplemental Figure 1). After adjusting for established confounders, presence of ASCVD was associated with a significantly higher odds of any difficulty paying medical bills and being unable of paying them at all when compared with those without ASCVD or cancer (Supplemental Table 4).

Sensitivity analyses

Given the high prevalence of nonmelanomatous skin cancer, we performed similar analyses excluding this diagnosis. In addition, we also performed analyses including breast, lung, and colorectal cancer only within our cancer group (i.e., no other cancer diagnoses were included), given their high incidence and mortality. Moreover, given concerns of having varying lengths of time and survival for different cancers and individuals, we performed 2 additional analyses: first, a comparison including only those with an active cancer diagnosis (i.e., only those with a cancer diagnosis diagnosed within the past year were included); and second, a series of stratified analyses by time since cancer diagnosis (≥0 to ≤5, >5 to ≤15, and >15 years). Overall, the patterns for FT measures remained similar in magnitude and direction among both non-elderly and elderly adults when comparing cancer and/or ASCVD (Supplemental Figures 2 to 13).

Discussion

In a nationally representative study using data from 2013 to 2018, we found that among non-elderly adults, ASCVD was associated with higher proportions of overall FT than patients with cancer, and patients with both illnesses concurrently had the worst outcomes across different measures of FT. These results were observed among elderly adults as well, although at significantly lower proportions. These findings demonstrate the severity of FT in patients with ASCVD when compared with cancer, the latter being one of the most researched causes of FT in the current published medical literature (3,4,7).

Our findings extend the prior published literature in several ways. First, to our knowledge, this is the first study directly analyzing FT in patients with cancer versus patients with ASCVD. Prior studies have suggested that the effect of ASCVD on FT is likely equivalent to or greater than that of cancer, but this issue had not been definitively investigated (34,35). In a previous paper, Narang et al. (34) detailed the differences in Medicare beneficiaries with cancer (compared with those without cancer, and substratified by other comorbidities), their out-of-pocket (OOP) expenditures, and financial burden. They showed that individuals with heart disease and/or stroke had higher median OOP expenditures ($2,371 vs. $2,120; p < 0.05) and financial burden (7.0% vs. 5.7%; p < 0.05) when compared with those with cancer in the overall study population. Our results not only confirm that individuals with a diagnosis of cancer have higher odds of all measures of FT than those without cancer nor ASCVD, but also highlight the burden that ASCVD represents in the overall adult population. Second, our study highlights the degree to which patients with these diseases experience financial health-related consequences. Furthermore, we also broaden the scope of the FT phenomenon across all adults, non-elderly and elderly. Our main study population was non-elderly adults, given that this population tends to have higher FT overall (5). Interestingly, we found that ASCVD was associated with a higher prevalence of FT, both alone and when occurring concurrently with cancer, compared with patients with cancer, including the elderly population. Based on previous reports, the drivers of FT, however, may be different in these populations; FT in cancer usually stems from cancer therapy pharmaceutical pricing (36), whereas ASCVD tends to be related to acute events often requiring hospitalization, like myocardial infarctions and/or stroke (13).

FT in cancer has been well described (3,5). Our results align with previous studies that found individuals with cancer to have high financial distress, cost-related medication nonadherence, food insecurity, and foregone/delayed care overall (10,23,37). Although understudied, our results build on the current published data regarding individuals with ASCVD as also having a high degree of the ill-associated measures under the umbrella of FT (12,13,35).

Our findings highlight the prevalence of, and urgent need for, effective methods to alleviate FT for ASCVD and cancer patients. In the current health system climate, there are small- and large-scale strategies to identify and combat FT. Clinicians can help patients deal with FT, as observed among oncologists when prompted to talk to their patients about financial burden in the office (38). This may be especially important for physicians, nurses, and advanced practice providers who care for patients with ASCVD and/or cancer, given the high economic burden and morbimortality potential these diseases carry. Indeed, it has been reported that a majority of patients with FT-related issues would like to discuss this problem with their health care providers; however, reports indicate that discussions addressing these concerns happen approximately in one-third of encounters (39) and are often not addressed at all (40, 41, 42). There are tools available for clinicians to address this problem. One such validated tool to engage with patients and test for FT is the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST), a patient-reported outcome measure to gauge FT in patients with cancer, which has been validated in the United States and abroad (43, 44, 45). However, to our knowledge, there are currently no tools for clinicians to measure FT among patients with ASCVD. Given the promise shown by COST, future work should develop and validate tools similar to COST for ASCVD patients. Such assessments leveraged proactively (e.g., during annual check-ups) combined with patient education on the costs involved in treatment of chronic cardiovascular conditions may persuade patients to adopt healthier lifestyles that effectively avoid potential FT. For this reason, the American Heart Association and the American College of Cardiology will likely incorporate value and cost in their next guidelines (46). However, as a strong research field in medications, devices, and innovation, cardiology clinicians are lagging behind in terms of FT in an era where treatment permits longer survival for their patients. This is paramount due to patients with cancer and/or ASCVD living longer lives through better and earlier care—which in parallel increases the potential for FT. Even with an aging population, which by definition has higher risk for both diseases and access to universal health coverage, Medicare patients appear to have lower FT, but are still not exempt from it (34,47); this population would ultimately have to deal with problems of a different nature altogether, like caregiver distress and end-of-life care and costs. We hope that by describing the extent of FT in patients with ASCVD, cancer, or both, clinicians will not only be able to provide better care, but will also be able develop support structures and interventions for the patients experiencing these diseases and FT (48).

Study limitations

First, our study population—those with ASCVD and/or cancer—was based on self-report. Although self-reported conditions can be potentially inaccurate, our estimates agree with those from previous published data using NHIS (12,49,50), and are in line with those reported by national associations, like the American Heart Association and the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (51,52). Second, we evaluate a limited number of features of FT from health care. Other aspects of financial ill-effects of treatments may not be captured. However, our focus was on domains that have been validated and widely used in prior studies and have shown to correlate well with objective measures of financial burden from OOP costs for medical expenditures (53). Third, questions relating to financial hardship used in NHIS assessed not only whether an individual but also whether anyone in the household had financial hardship, and precludes assessment of the proportion of medical bills directly related to ASCVD and/or cancer and their contribution to financial hardship itself. Khera et al. (13) recently detailed that health care spending on family members with ASCVD represented a mean of 70% of the overall family OOP health spending, with the respective proportion being slightly higher for low-income families. Fourth, it was not possible to differentiate the proportion of financial hardship caused by a specific catastrophic event from the effect of chronic bills. A recent survey suggested that over 60% of individuals with financial hardship from medical bills reported it being tied to a catastrophic medical expense, whereas 1 reports bills for treatment of chronic conditions that have built up over time (54). Fifth, it is difficult to establish causality due to the cross-sectional nature of this study. It is possible that there is a bidirectional relationship between FT and some of its perceived effects on ASCVD and/or cancer. For example, it has been described that food insecurity is often more prevalent in the low-income population (55, 56, 57), hinting toward an income-based problem rather than a purely health-related financial consequence. Although is it plausible that causality may be bidirectional (i.e., food insecurity could lead to inadequate financial coping behaviors, or financial hardship could lead to food insecurity) (57), others have argued that health behaviors could potentially be affected by food insecurity (58). Sixth, no adjustments for possible type 1 errors for multiple comparisons were used, so these results should be interpreted with caution. Finally, there is a possibility that the strategies to mitigate FT in cancer have started yielding positive results, and these are reflected in our analyses.

Conclusions

Patients with ASCVD report greater difficulty paying bills and experience high financial distress from medical costs, cost-related medication nonadherence, and food insecurity, and they forego/delay care due to cost at a proportion exceeding those with the population with cancer. It is critical that interventions to mitigate treatment-related costs that have been implemented among cancer patients are evaluated for patients with ASCVD. Finally, we hope that the findings documented here would serve as the basis for future prospective patient-centered inquiries to investigate patients’ perceptions of FT to inform well-accepted and sustainable interventions.

Perspectives.

COMPETENCY IN MEDICAL KNOWLEDGE: Patients with ASCVD reported higher financial toxicity, irrespective of cancer status (i.e., in those with or without cancer). This association remained significant after adjustment for potential confounders and across age stratification and subanalyses by specific cancer groupings. Patients with both ASCVD and cancer had the highest prevalence of financial toxicity.

TRANSLATIONAL OUTLOOK: Future studies should focus on what the determinants for financial toxicity are in each disease group, and to develop strategies to mitigate these to alleviate health-related economic hardship for patients and care providers.

Funding Support and Author Disclosures

Dr. Virani has received grant funding from the Department of Veterans Affairs, World Heart Federation and the Jooma and Taher Family; has received an honorarium from the American College of Cardiology (Associate Editor for Innovations, acc.org); and is the member of a steering committee for the Patient and Provider Assessment of Lipid Management (PALM) registry at the Duke Clinical Research Institute (no financial remuneration). Dr. Krumholz has received research agreements from Medtronic and Johnson & Johnson (Janssen), through Yale, to develop methods of clinical trial data sharing; has received a grant from Medtronic and the Food and Drug Administration, through Yale, to develop methods for postmarket surveillance of medical devices and work under contract with the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services to develop and maintain performance measures that are publicly reported; is chair of a cardiac scientific advisory board for United Health; is a participant/participant representative of the IBM Watson Health Life Sciences Board; is a member of the Advisory Board for Element Science and the Physician Advisory Board for Aetna; and is the founder of Hugo, a personal health information platform. Dr. Nasir is on the advisory board of Amgen, Novartis, Medicine Company; and his research is partly supported by the Jerold B. Katz Academy of Translational Research. The funders had no role in the design and conduct of the study; collection, management, analysis, and interpretation of the data; preparation, review, or approval of the manuscript; and decision to submit the manuscript for publication. All other authors have reported that they have no relationships relevant to the contents of this paper to disclose.

Footnotes

The authors attest they are in compliance with human studies committees and animal welfare regulations of the authors’ institutions and Food and Drug Administration guidelines, including patient consent where appropriate. For more information, visit the Author Center.

Appendix

For supplemental tables and figures, please see the online version of this paper.

Appendix

References

- 1.Lentz R., Benson A.B., 3rd, Kircher S. Financial toxicity in cancer care: prevalence, causes, consequences, and reduction strategies. J Surg Oncol. 2019;120:85–92. doi: 10.1002/jso.25374. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Financial toxicity (financial distress) and cancer treatment (PDQ®)–patient version. https://www.cancer.gov/about-cancer/managing-care/track-care-costs/financial-toxicity-pdq Available at: [PubMed]

- 3.Gordon L.G., Merollini K.M.D., Lowe A., Chan R.J. A systematic review of financial toxicity among cancer survivors: we can't pay the co-pay. Patient. 2017;10:295–309. doi: 10.1007/s40271-016-0204-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Altice C.K., Banegas M.P., Tucker-Seeley R.D., Yabroff K.R. Financial hardships experienced by cancer survivors: a systematic review. J Natl Cancer Inst. 2017;109:djw205. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djw205. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Yabroff K.R., Dowling E.C., Guy G.P., Jr. Financial hardship associated with cancer in the united states: findings from a population-based sample of adult cancer survivors. J Clin Oncol. 2016;34:259–267. doi: 10.1200/JCO.2015.62.0468. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Nathan P.C., Henderson T.O., Kirchhoff A.C., Park E.R., Yabroff K.R. Financial hardship and the economic effect of childhood cancer survivorship. J Clin Oncol. 2018 doi: 10.1200/JCO.2017.76.4431. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Kircher S.M., Yarber J., Rutsohn J. Piloting a financial counseling intervention for patients with cancer receiving chemotherapy. J Oncol Pract. 2019;15:e202–e210. doi: 10.1200/JOP.18.00270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Zafar S.Y., Newcomer L.N., McCarthy J., Fuld Nasso S., Saltz L.B. How should we intervene on the financial toxicity of cancer care? one shot, four perspectives. Am Soc Clin Oncol Educ Book. 2017;37:35–39. doi: 10.1200/EDBK_174893. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yabroff K.R., Gansler T., Wender R.C., Cullen K.J., Brawley O.W. Minimizing the burden of cancer in the United States: goals for a high-performing health care system. CA Cancer J Clin. 2019;69:166–183. doi: 10.3322/caac.21556. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carrera P.M., Kantarjian H.M., Blinder V.S. The financial burden and distress of patients with cancer: understanding and stepping-up action on the financial toxicity of cancer treatment. CA Cancer J Clin. 2018;68:153–165. doi: 10.3322/caac.21443. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Salami J.A., Valero-Elizondo J., Ogunmoroti O. Association between modifiable risk factors and pharmaceutical expenditures among adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States: 2012-2013 Medical Expenditures Panel Survey. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 doi: 10.1161/JAHA.116.004996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valero-Elizondo J., Khera R., Saxena A. Financial hardship from medical bills among nonelderly U.S. adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease. J Am Coll Cardiol. 2019;73:727–732. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.12.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Khera R., Valero-Elizondo J., Okunrintemi V. Association of out-of-pocket annual health expenditures with financial hardship in low-income adults with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. JAMA Cardiol. 2018;3:729–738. doi: 10.1001/jamacardio.2018.1813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Khera R., Hong J.C., Saxena A. Burden of catastrophic health expenditures for acute myocardial infarction and stroke among uninsured in the United States. Circulation. 2018;137:408–410. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.117.030128. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Annapureddy A., Valero-Elizondo J., Khera R. Association between financial burden, quality of life, and mental health among those with atherosclerotic cardiovascular disease in the United States. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2018;11 doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.118.005180. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Miller G.E., Sarpong E.M., Hill S.C. Does increased adherence to medications change health care financial burdens for adults with diabetes? J Diabetes. 2015;7:872–880. doi: 10.1111/1753-0407.12292. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Choi S. Experiencing financial hardship associated with medical bills and its effects on health care behavior: a 2-year panel study. Health Educ Behav. 2018;45:616–624. doi: 10.1177/1090198117739671. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Dhaliwal K.K., King-Shier K., Manns B.J., Hemmelgarn B.R., Stone J.A., Campbell D.J. Exploring the impact of financial barriers on secondary prevention of heart disease. BMC Cardiovasc Disord. 2017;17:61. doi: 10.1186/s12872-017-0495-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ford E.S. Food security and cardiovascular disease risk among adults in the United States: findings from the National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey, 2003-2008. Prev Chronic Dis. 2013;10:E202. doi: 10.5888/pcd10.130244. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.CDC National Center for Health Statistics Leading causes of death in the United States. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/fastats/leading-causes-of-death.htm Available at:

- 21.CDC National Center for Health Statistics About NHIS. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/about_nhis.htm Available at:

- 22.Human Subject Regulations Decision Charts: 2018 Requirements. https://www.hhs.gov/ohrp/regulations-and-policy/decision-charts-2018/index.html Available at:

- 23.Kent E.E., Forsythe L.P., Yabroff K.R. Are survivors who report cancer-related financial problems more likely to forgo or delay medical care? Cancer. 2013;119:3710–3717. doi: 10.1002/cncr.28262. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Rabin D.L., Jetty A., Petterson S., Saqr Z., Froehlich A. Among low-income respondents with diabetes, high-deductible versus no-deductible insurance sharply reduces medical service Use. Diabetes Care. 2017;40:239–245. doi: 10.2337/dc16-1579. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Pollitz K., Cox C. Kaiser Family Foundation; 2014. Medical debt among people with health insurance.https://www.kff.org/private-insurance/report/medical-debt-among-people-with-health-insurance/ Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 26.Patel M.R., Piette J.D., Resnicow K., Kowalski-Dobson T., Heisler M. Social determinants of health, cost-related nonadherence, and cost-reducing behaviors among adults with diabetes: findings from the National Health Interview. Survey. Med Care. 2016;54:796–803. doi: 10.1097/MLR.0000000000000565. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Bickel G., Nord M., Price C., Hamilton W., Cook J. U.S. Department of Agriculture, Food and Nutrition Service; Alexandria, VA: 2018. Guide to Measuring Household Food Security, Revised 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 28.NHIS Data, Questionnaires and Related Documentation. https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/nhis/data-questionnaires-documentation.htm Available at:

- 29.Seligman H.K., Laraia B.A., Kushel M.B. Food insecurity is associated with chronic disease among low-income NHANES participants. J Nutr. 2010;140:304–310. doi: 10.3945/jn.109.112573. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Choi S. Experiencing unmet medical needs or delayed care because of cost: foreign-born adults in the U.S. by region of birth. Int J Health Serv. 2016;46:693–711. doi: 10.1177/0020731416662610. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Joosten M.M., Pai J.K., Bertoia M.L. Associations between conventional cardiovascular risk factors and risk of peripheral artery disease in men. JAMA. 2012;308:1660–1667. doi: 10.1001/jama.2012.13415. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Valero-Elizondo J., Salami J.A., Ogunmoroti O. Favorable cardiovascular risk profile is associated with lower healthcare costs and resource utilization: the 2012 Medical Expenditure Panel Survey. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. 2016;9:143–153. doi: 10.1161/CIRCOUTCOMES.115.002616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.IPUMS Health Surveys National Health Interview Survey, Version 6.2. 2016. https://www.ipums.org/ Available at:

- 34.Narang A.K., Nicholas L.H. Out-of-pocket spending and financial burden among Medicare beneficiaries with cancer. JAMA Oncol. 2017;3:757–765. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.4865. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Osborn C.Y., Kripalani S., Goggins K.M., Wallston K.A. Financial strain is associated with medication nonadherence and worse self-rated health among cardiovascular patients. J Health Care Poor Underserved. 2017;28:499–513. doi: 10.1353/hpu.2017.0036. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Tran G., Zafar S.Y. Financial toxicity and implications for cancer care in the era of molecular and immune therapies. Ann Transl Med. 2018;6:166. doi: 10.21037/atm.2018.03.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Zafar S.Y., Peppercorn J.M., Schrag D. The financial toxicity of cancer treatment: a pilot study assessing out-of-pocket expenses and the insured cancer patient's experience. Oncologist. 2013;18:381–390. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2012-0279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Shankaran V., Ramsey S. Addressing the financial burden of cancer treatment: from copay to can't Pay. JAMA Oncol. 2015;1:273–274. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2015.0423. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hunter W.G., Zhang C.Z., Hesson A. What strategies do physicians and patients discuss to reduce out-of-pocket costs? Analysis of cost-saving strategies in 1,755 outpatient clinic visits. Med Decis Making. 2016;36:900–910. doi: 10.1177/0272989X15626384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Meisenberg B.R., Varner A., Ellis E. Patient attitudes regarding the cost of illness in cancer care. Oncologist. 2015;20:1199–1204. doi: 10.1634/theoncologist.2015-0168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Meeker C.R., Geynisman D.M., Egleston B.L. Relationships among financial distress, emotional distress, and overall distress in insured patients with cancer. J Oncol Pract. 2016;12:e755–e764. doi: 10.1200/JOP.2016.011049. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Mead E.L., Doorenbos A.Z., Javid S.H. Shared decision-making for cancer care among racial and ethnic minorities: a systematic review. Am J Public Health. 2013;103:e15–e29. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2013.301631. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.de Souza J.A., Yap B.J., Wroblewski K. Measuring financial toxicity as a clinically relevant patient-reported outcome: the validation of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) Cancer. 2017;123:476–484. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Honda K., Gyawali B., Ando M. Prospective survey of financial toxicity measured by the comprehensive score for financial toxicity in Japanese patients with cancer. J Glob Oncol. 2019;5:1–8. doi: 10.1200/JGO.19.00003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Ripamonti C.I., Chiesi F., Di Pede P. The validation of the Italian version of the COmprehensive Score for financial Toxicity (COST) Supportive Care Cancer. 2020;28:4477–4485. doi: 10.1007/s00520-019-05286-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Hlatky M.A. Considering cost-effectiveness in cardiology clinical guidelines: progress and prospects. Value Health. 2016;19:516–519. doi: 10.1016/j.jval.2016.04.019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Davis K., Stremikis K., Doty M.M., Zezza M.A. Medicare beneficiaries less likely to experience cost- and access-related problems than adults with private coverage. Health Aff (Millwood) 2012;31:1866–1875. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2011.1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Mennini F.S., Marcellusi A., von der Schulenburg J.M. Cost of poor adherence to anti-hypertensive therapy in five European countries. Eur J Health Econ. 2015;16:65–72. doi: 10.1007/s10198-013-0554-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Kaul S., Avila J.C., Mehta H.B., Rodriguez A.M., Kuo Y.F., Kirchhoff A.C. Cost-related medication nonadherence among adolescent and young adult cancer survivors. Cancer. 2017;123:2726–2734. doi: 10.1002/cncr.30648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Berkowitz S.A., Seligman H.K., Choudhry N.K. Treat or eat: food insecurity, cost-related medication underuse, and unmet needs. Am J Med. 2014;127:303–310.e3. doi: 10.1016/j.amjmed.2014.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Virani S.S., Alonso A., Benjamin E.J. Heart disease and stroke statistics-2020 update: a report from the American Heart Association. Circulation. 2020;141:e139–e596. doi: 10.1161/CIR.0000000000000757. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.American Heart Association CDC heart disease and stroke prevention program. https://www.heart.org/en/get-involved/advocate/federal-priorities/cdc-prevention-programs#:∼:text=An%20estimated%2080%25%20of%20cardiovascular,nearly%20%241%20billion%20a%20day Available at:

- 53.Chen J.E., Lou V.W., Jian H. Objective and subjective financial burden and its associations with health-related quality of life among lung cancer patients. Support Care Cancer. 2018;26:1265–1272. doi: 10.1007/s00520-017-3949-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.The burden of medical debt: results from the Kaiser Family Foundation/New York Times Medical Bills Survey. 2016. https://www.kff.org/wp-content/uploads/2016/01/8806-the-burden-of-medical-debt-results-from-the-kaiser-family-foundation-new-york-times-medical-bills-survey.pdf Available at: [Google Scholar]

- 55.Herman D., Afulani P., Coleman-Jensen A., Harrison G.G. Food insecurity and cost-related medication underuse among nonelderly adults in a nationally representative sample. Am J Public Health. 2015;105:e48–e59. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2015.302712. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Charkhchi P., Fazeli Dehkordy S., Carlos R.C. Housing and food insecurity, care access, and health status among the chronically ill: an analysis of the behavioral risk factor surveillance system. J Gen Intern Med. 2018;33:644–650. doi: 10.1007/s11606-017-4255-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Berkowitz S.A., Basu S., Meigs J.B., Seligman H.K. Food insecurity and health care expenditures in the United States, 2011-2013. Health Serv Res. 2018;53:1600–1620. doi: 10.1111/1475-6773.12730. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Leung C., Tester J., Laraia B. Household food insecurity and ideal cardiovascular health factors in US adults. JAMA Intern Med. 2017;177:730–732. doi: 10.1001/jamainternmed.2017.0239. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.