Unless those who deliver health care in Delaware invest in continuity planning, they risk never being able to recover from events like natural disasters, human-caused events, and malicious technological breaches. Continuity planning places the organization in the best position to avert these and other threats.

Delaware has a diverse and robust for-profit health care delivery system that includes hospitals, skilled nursing facilities, home health services, physician offices, diagnostic centers, specialty care treatment centers, mental and behavioral health, and a variety of other components. In 2019, the U.S. Department of Labor, in collaboration with Infogroup, a leading provider of data and data-driven marketing solutions, found that health care providers represented three of the top five largest employers in Delaware, accounting for an approximate combined total of 20,000 employees.1 To avert disaster, public and non-profit entities including Federally Qualified Health Centers (FQHC), divisions within Delaware Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS), and others require the same level of continuity planning as their for-profit partners.

When examining the health care delivery system and the role of continuity, two distinct goals surface. First, individual businesses or agencies should have plans in place to recover business or mission functions after a disaster occurs. According to the Federal Emergency Management Agency (FEMA), “40 percent of small businesses never reopen after a disaster and another 25 percent, that do reopen, fail within a year.”2 FEMA has found that “following a disaster, 90% of smaller companies fail within a year unless they can resume operations within 5 days.”3 Continuity is not only important to a business’ bottom line, but it has a broader socioeconomic impact regarding employment and services. Second, the health care system must be maintained following a disaster. Rapid recovery of operations after an event is critical to the community, which may require medical services.

Continuity Planning versus Emergency Preparedness

At first glance, continuity planning and emergency preparedness can be a daunting undertaking, especially for professionals who are unexpectedly saddled with those responsibilities. Within the national and state health care delivery systems, dedicated emergency managers typically exist only within hospital systems. In most workplaces, staff who have other primary day-to-day missions will complete the organization’s continuity and emergency planning.

Although these terms and processes overlap, they are quite different. The primary goal of emergency preparedness is to safeguard people and property from harm. Preparedness is a fluid and dynamic process that requires continual updates with adjustments. Continuity’s main goal focuses on the continuation of key business or mission operations. Recognizing the difference permits the identification of different key tasks relating to the planning processes. Many businesses manage the two processes as one – a logical combination since both processes are working towards the same objective. However, this may not be the right decision for many organizations. Continuity cannot be fully addressed within the organization’s emergency preparedness planning component.

Emergency preparedness plans may only provide a false sense of security from a continuity perspective and in many cases, may leave the business or organization vulnerable to irreparable damage. The 2017 letter to State Survey Agency Directors from the Centers for Medicare and Medicaid Services (CMS) delineated that the emergency plan is developed to support Continuity of Business Operations. The memo indicated that “an emergency plan provides the framework for the emergency preparedness program. The emergency plan is developed based on facility- and community-based risk assessments that assist a facility in anticipating and addressing facility, patient, staff and community needs and support continuity of business operation.”4 The memo further delineates the two processes by defining that continuity planning “generally considers elements such as: essential personnel, essential functions, critical resources, vital records and IT data protection, alternate facility identification and location, and financial resources” all of which are accurate assessments (see Figure 1).4

Figure 1.

Continuity Cycle’s Influence within the Comprehensive Emergency Management Cycle5

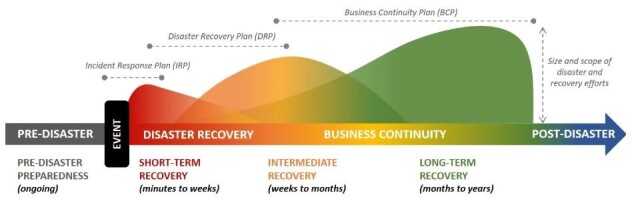

Depending on the organization’s mission, a continuity plan should incorporate components of three continuity planning styles: Disaster Recovery (DR), Continuity of Operation Planning (COOP), and Business Continuity (BC). While they each have distinct nuances, emergency management professionals use the COOP and BC titles and concepts interchangeably, falsely leading many to surmise that they share the same meaning and purpose. COOP and BC actually have fundamental differences in their role definition and planning methodologies. According to the Disaster Recovery Journal, the most notable difference between COOP and BC “is the ability of the organization to survive and the capability of the organization to recover from a disaster (Figure 2).7 COOP organizations expect they will do whatever is needed to meet the challenges of a disruption. There is no question they will remain operational during and after the event. BC organizations know they can fail. They seek to remain viable as an entity, with the understanding an unsuccessful recovery may force them to go under.”7 There is value in understanding whether the organization needs a COOP or a BC plan.

Figure 2.

Disaster Event Cycle and Plan Overlap6

Continuity of Operations Planning (COOP)

COOP found its roots in civil defense planning, which dates back prior to World War II. In 1982, through executive order, President Ronald Reagan formalized U.S. government continuity planning in response to rising tensions from the Cold War with National Security Decision Directive 47 and 55. The “various measures were designed to ensure that the government of the United States would be able to continue operating after a nuclear war.”8

Governmental and public organizations should use the COOP process and terminology. These organizations plan with the assumption that in a disaster their mission is such that they cannot fail. Federal Continuity Directives written by the U.S. Department of Homeland Security (DHS) and FEMA outline the methodology for COOP. Presidential Policy Directive 40 outlines the program. Requirements are found within Federal Continuity Directives 1 and 2. President George W. Bush updated these policies with National Security Presidential Directive 51 and 20.9 Within the federal government and sometimes with state governments are the terms “Enduring Constitutional Government (ECG)” and “Continuity of Government (COG),” which refer to how the government will continue its command and constitutional powers during a disaster. An example of ECG and COG seen in popular culture is the television series, “Designated Survivor.” Although adapted for dramatic television, this example is a real process that often occurs when large portions of the government are in one location, such as during the State of the Union address. The only unclassified COG/CEG event in recent history occurred immediately after the September 11, 2001 attacks. Between 75 and 150 key senior federal government officials and other critical governmental workers from every executive department in Washington, D.C. were evacuated to secure bunkers known today as Raven Rock and Mount Weather Emergency Operations Center.8

Delaware state agencies, including DHSS and the Division of Public Health (DPH), maintain continuity of operations plans. On October 13, 2017, Governor John C. Carney signed and distributed Executive Order 15. Executive Order 15, a promulgation of the Delaware Emergency Operations Plan, stipulates that “each executive department or agency shall develop plans to ensure continuity of operations during times of emergency, consistent with the requirements in the plan or as may be promulgated by the Secretary through the Delaware Emergency Management Agency to ensure its ability to carry out essential government functions in the aftermath of a disaster or emergency.”10

DPH’s Office of Preparedness works closely with DHSS divisions and DPH sections to ensure that continuity plans meet FEMA best practices. This ensures that each agency is prepared to recover their mission critical functions in a disaster. Validating plans and training for continuity is a vital part to a robust continuity program. In May 2019, DPH’s Emergency Medical Services and Preparedness Section performed a full-scale exercise for the DHSS COOP. Staff received an emergency notification that the primary office was impacted by an event and that all staff should report to the alternate facility. Approximately 50 staff relocated to the alternate facility, received Just-In-Time training, performed a turnover of the working space following the plan, and were able to demonstrate that essential mission functions could be performed. Three months later, senior leadership from all DHSS and DPH offices with disaster roles participated in a facilitated tabletop exercise to validate each representative’s plan (see Figure 3). The attendance by each group’s senior leadership allowed for high-level plan review and validation. DHSS and DPH leadership are committed to ensuring that their agencies maintain a robust continuity program to minimize the impact to the communities they serve.

Figure 3.

Delaware Department of Health and Social Services (DHSS) and Delaware Emergency Management Agency (DEMA) staff discuss continuity relocation to alternate facilities during an August 13, 2019 COOP tabletop exercise. Pictured from left: Division of Public Health (DPH) Deputy Director Crystal Webb, DHSS Deputy Secretary Molly Magarik, DEMA Principal Planner Tony Lee, DPH Director of Preparedness Timothy Cooper, and Chief of DPH’s Emergency Medical Services and Preparedness Section Steve Blessing. Photo Credit: Eric Donato EMSPS.

FEMA provides a wide variety of COOP training and programs that are free of cost and can be applied to the public and private sector organizations.

Business Continuity (BC)

Private industry, including health care, largely uses BC. BC generally looks inward and focuses on preserving the organization, keeping it in business and generating revenue. BC and what is now known as modern Emergency Management were “both born, in part, from the California forest fires of the early 1970s. The Incident Command System (ICS) was formalized in that crucible by the National Fire Prevention Association (NFPA). So was the NFPA-1600 standard, the first standard dedicated solely to BC.”7 The other major delineation is that BC is formed from the ground level up compared to COOP, which by design is a top-down approach to planning and execution. Resources and money limit business continuity. Applying a top-down COOP model and process designed for government may be inappropriate for a business as these models assume few or no limits to recovery resources.7 Private businesses should factor costs, profits, and losses in their BC planning; their business goal is to remain viable and an unsuccessful recovery could result in going out of business.

Disaster Recovery (DR)

DR is a subset of business continuity planning that focuses on communication, hardware, and other Information Technology (IT) assets. DR’s goal is to minimize a business’s downtime by quickly restoring technical operations. DR incidents range from a small computer malfunction to a large data breach of a records system.

Data and health care are inseparable in today’s world of telemedicine and electronic patient records. Findings from the U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) found that “based upon data collected by the HHS Office for Civil Rights, as of February 1, 2016, protected health information breaches affected over 113 million individuals in 2015. In 2015, hacking incidents comprised nearly 99 percent of all individuals affected by breaches, and the number of reported hacking incidents, 57, comprised over 20% of all reported breaches.”11

CMS Emergency Preparedness Rule and Continuity

The final rule on emergency preparedness requirements for Medicare and Medicaid participating providers and suppliers took effect in 2017.4 Its intent was to establish an all-hazards, risk-based, community-integrated approach to emergency preparedness planning that ensures health care facilities can handle a wide spectrum of disasters. The rule came almost a decade after Hurricane Katrina, which in 2005 devastated New Orleans, Louisiana and demonstrated the fragility and unready posture of the government at the local, state, and federal levels as well as the health care system overall. The tragedies that took place after Katrina’s landfall, including those at Memorial Medical Center, have shaped today’s private health care and public health emergency preparedness.

Like other states, the Delaware health care system is comprised of a diverse and vast network of providers and services. In theory, the system can easily absorb the loss of a single provider or site, but becomes strained when multiple providers are unable to reopen after an event. When a system faces pre-disaster challenges, a network with fewer providers is less capable of responding to, and recovering from, an event. Health care organizations should implement the CMS rules as the minimum foundation, as meeting the standard should not be reason to remain static. The CMS emergency preparedness rule does mean more preparedness, but a continual process of improvement should be implemented. Businesses can only make money and survive if they are able to provide services or deliver goods. The health care delivery system can only survive only if each network partner is operating effectively. The steps taken to improve an organization’s continuity will pay dividends when disaster strikes and very well may be the difference in life and death for community members. When Hurricane Katrina hit New Orleans, “roughly 300 deaths were recorded at hospitals, long-term care facilities and in nursing homes according to a recently published study of death certificates and disaster mortuary team records.”12 At every level, the health care industry has a moral obligation to their patients and customers to continuously improve their readiness (see Figure 4).

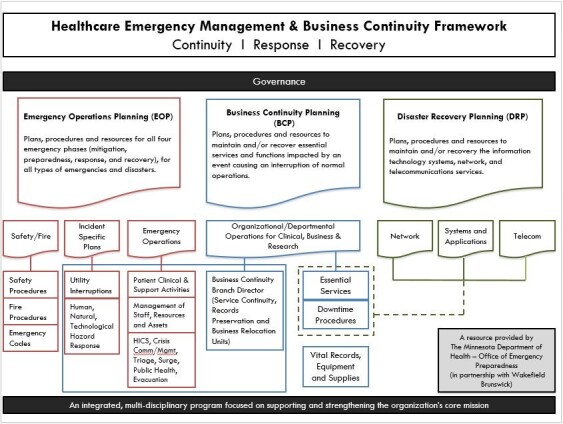

Figure 4.

Healthcare Emergency Management and Business Continuity Framework13

Continuity Program Foundations: Where to Begin

BC and COOP are specific plans, procedures, and resources that allow a health care organization to recover their essential services and functions during an event that disrupts normal operations. Organizations that meet the CMS emergency preparedness guidelines may not have a robust BC plan. To champion continuity with an organization, follow the five best foundational practices:

1. Gain organization leadership buy-in.

Before seeking leadership support, research BC or COOP in health care, and participate in continuity courses. Many of the BC and COOP mitigation measures, such as creating a staff contact roster, can be performed at little to no cost. Remember that the goal of BC is self-preservation. Can your organizational leadership afford to do nothing?

2. Establish a BC or COOP planning team.

Establish a strong internal planning team with staff that have preparedness mindsets. Regardless of its size, the team should represent all critical elements: clinical operations, non-clinical operations, and specialties like human resources or IT.

3. Identify one executive or leader with authority to serve as project manager.

To avoid isolated efforts and to embrace cross-functional planning, one executive or leader with authority should function as the overall project manager. The project manager ensures that collaboration occurs, deadlines are met, and the project maintains forward progress, in addition to resolving conflicts.

4. Perform a BC Risk Assessment or COOP Threat and Hazard Identification and Risk Assessment (THIRA).

The first step to performing a BC Risk Assessment or COOP THIRA is to understand what risks exist. This process is likely simpler than most would think, as most emergency management agencies and public health agencies are required by their grants to perform risk assessments for their jurisdictions. Many are available online; however, if one cannot be located for your area, contact the state or local public health preparedness office or emergency management agency. The risk assessment should identify threats or hazards with opportunities for hazard prevention, deterrence, or risk mitigation.

5. For BC Perform a Business Impact Analysis (BIA)

A BIA predicts the consequences of disruption of a business function or process and gathers information needed to develop a recovery strategy. Considering potential operational and financial impacts, the BIA should include other outcomes such as regulatory fines, contractual penalties, and customer dissatisfaction. Factor in the timing and duration of disruption, as these variables can alter the impact to the business. The BIA will be used to establish priories to restore business operations.

The five foundations are a starting point in the journey to continuity. When continuity planning is incorporated into the culture of an organization, a shift occurs in which business and operational decisions are made based on risk, mitigation, and resiliency, placing the organization in the best position to avert disaster (see Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Business Continuity Infographic3

Advice for Small Health Offices with Limited Resources

From dental offices to FQHCs, small health offices provide critical community services. A disruption to their operations or their inability to recover can result in business failure and a loss of those community resources. Small health offices can follow these four recommendations when developing a comprehensive continuity plan:

1. Develop a staff, vendor, and other critical personnel rosters.

Include home and cell phone contact numbers and electronic messaging information, as well as contact information for service providers, insurance companies, landlords, and others. Inform staff how they will be contacted in the event of an emergency. When a disaster strikes, the first action will be to get information to staff and critical partners. These rosters should be easily accessible and stored at an off-site location in addition to the business.

2. Develop an order of succession for the organization.

Operations should not come to a complete stop if one person is unavailable. If the organization’s decision maker is unavailable or incapacitated, is there clear guidance that indicates who is authorized to perform those duties, roles, and responsibilities? Orders of succession are provisions for the assumption of senior leadership positions during an emergency when the incumbents are unable or unavailable to execute their legal duties.

When possible, have the order of succession at least “three deep,” meaning that if the head leader of the organization was incapacitated, identify two others who could perform that role functions in an emergency. Emergencies and disasters can be stressful times, so identifying succession orders in advance provides your staff and organization clear guidance on roles and responsibilities.

3. Delegation of authority should complement succession planning.

Delegation of authority specifies who is authorized to make decisions and act on behalf of leadership and other key personnel for specific purposes during emergencies. Although similar to succession planning, delegation of authority encompasses a task rather than a position, i.e. approving timesheets.

4. Set small achievable goals.

Choose one idea this article sparked in your mind, write a small goal to work towards, and commit to achieving it within the next 30 days. When that and other goals are reached, celebrate and thank staff. Every preparedness action taken, no matter how small, makes a business better prepared than the day before.

Continuity Training Opportunities

FEMA offers training opportunities at no cost, including wide varieties of online independent study courses and one-, two-, and three-day in-person courses specific to continuity. FEMA Continuity courses are periodically offered directly through the Delaware Emergency Management Agency. FEMA also offers two levels of professional certification for continuity: the Professional and Master Continuity Practitioner. The continuity certifications provided through FEMA, including the proctored examination, are provided free of charge. Visit https://www.fema.gov/continuity-excellence-series-professional-and-master-practitioner-continuity-certificate-programs.

Disaster Recovery Institute (DRI) International is a nonprofit that helps organizations around the world prepare for and recover from disasters by providing education, accreditation, and leadership in business continuity and related fields. The organization holds an annual conference and has a variety of training specific to business continuity and disaster recovery. DRI also offers a variety of professional certification for business continuity, most notably the Certified Business Continuity Practitioner and a new Certified Healthcare Provider Continuity Professional program. DRI training and certification have associated costs. Visit https://drii.org.

Continuity Resources

Varieties of resources exist to help both public and private sector organizations build continuity. The NFPA 1600 Standard on Continuity, Emergency, and Crisis Management contains a large variety of resources to help meet compliance with Joint Commission Standards and CMS Emergency Preparedness rules. Read a crosswalk of the CMS Emergency Preparedness Final Rule to NFPA 1600 at https://www.team-iha.org/files/non-gated/quality/cms-emerg-preparedness-crosswalk.aspx.

FEMA’s Continuity Resource Toolkit contains information, templates, development guides, exercises, and more at no cost. Visit https://www.fema.gov/continuity-resource-toolkit.

The DHS Business Continuity Planning Suite provides instructional videos that provide guidance for BC development; visit https://www.ready.gov/business-continuity-planning-suite. Their business section’s testimonials can be shared with organizational leadership to help establish buy-in.

When organizations within the health care delivery systems develop a continuity program, they will likely incorporate both COOP and BC components. The degree to which these components are incorporated is dependent on the organizational choice of a more top-down COOP response focus or a bottom-up BC recovery focus. When former U.S. Assistant Secretary of Defense for Homeland Security Dr. Paul Stockton discussed preparedness and continuity, he stated: “It’s not rocket science, it’s not fear mongering, it is being sensible about where we buy down risk against a whole class of threats.”14

Every Delaware health care business should be familiar with all potential threats to their business operations, from a flood to a flu pandemic. Businesses and organizations should remember, “Throughout history there always has been a moment in the life of every problem where it was big enough to be seen and still small enough to be addressed.”14 To avoid financial hardship, businesses should invest in continuity planning now or risk difficult or impossible recoveries. Regardless of an organization’s role in the health care delivery system, continuity and organizational resilience is critical for the recovery of individual organizations after a disaster, as well as for the recovery of the health care system as a whole.

References

- 1.United States Department of Labor. (2019). State profile: Largest employers Delaware. Ohama: Infogroup.

- 2.McKay, J. (2018). Small businesses are a vital part of community resiliency but often overlook vulnerabilities. Government Technology, Emergency Management. [Google Scholar]

- 3.Federal Emergency Management Agency. (2019). FEMA Media Library Business Continuity. Retrieved from: https://www.fema.gov/media-library-data/1441212988001-1aa7fa978c5f999ed088dcaa815cb8cd/3a_BusinessInfographic-1.pdf

- 4.Department of Health & Human Services. (2017). Emergency preparedness final rule interpretive guidelines and survey procedures. Baltimore: Center for Medicare & Medicaid Services. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Grand Traverse County Emergency Management. (2019). What is emergency management? Retrieved from https://www.grandtraverse.org/379/What-is-Emergency-Management

- 6.Complance Forge. (2018). Retrieved from Continuity Planning: https://www.complianceforge.com/product/continuity-of-operations-plan/

- 7.Binder, A. (2018). Continuity of operations does not mean business continuity. Disaster Recovery Journal. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Graff, G. M. (2017). Raven Rock: The story of the U.S. Government's secret plan to save itself. Simon & Schuster. [Google Scholar]

- 9.U.S. Department of Homeland Security. (2017). Federal continuity directive 1. Washington, DC: United States Government. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Carney, J. C. (2017). Executive Order Number Fifteen, Promulgation of the Delaware Emergency Operations Plan. Dover: State of Delaware. [Google Scholar]

- 11.U.S. Health and Human Services. (2019). 2015-2016-2017 Report to Congress on the breach notification program. Washington, DC: U.S. Department of Health and Human Services (HHS) Office for Civil Rights. [Google Scholar]

- 12.Fink, S. (2013). Five days at memorial. Crown Publishing Group. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Minnesota State Department of Health . (2019). Executive briefing PowerPoint. Retrieved from https://www.health.state.mn.us/communities/ep/coalitions/coop/index.html

- 14.Council, E. I. (2014, December 28). Black Sky. (N. E. Film, Interviewer)