Community-Engaged Research (CEnR) has become the talk of the town in translational research. The National Institute of Health (NIH), the predominant funder of research in the United States, has made translational research a priority, and emphasizes community engagement in as a necessary component of translational research. Translational research seeks to effectively translate new knowledge (research) into new approaches for prevention, diagnosis, and treatment of disease and translation is essential for improving health (impact). Initially, most of us defined translational research as “bench to bedside” but disparity science and implementation science has made us all acutely aware that we need to go much further than the bedside and ensure that the often amazing discoveries of science are effectively and equitably shared to the benefit of all communities. In this issue, we highlight several local examples of CEnR. To begin, Dr. Dewey’s work and the work of Moore and colleagues are examples of implementation, taking evidence-based interventions and applying them in the real world settings where they are needed most.

Community-Engaged research (CEnR) is about partnership

The ultimate goal of research is to improve health. Yet, research often fails to permeate locally, especially in vulnerable communities. CEnR is not a particular method but rather an approach to research which emphasizes an equitable partnership and seeks to include the voice of those communities who are likely to be impacted by the research. CEnR prioritizes developing capacity, improving trust, and translating knowledge to action. While CEnR is not exclusively about engaging with vulnerable populations, it is especially pertinent in communities who experience disparity. Dr. Kahal’s work educating community physicians on Hepatitis C virus (HCV) screening and treatment is an example where the having done the science and created the medicine are not enough. Lifesaving treatments for HCV have often failed to get to the vulnerable communities who need it most.

Engaging patients and communities in research improves impact

It seems obvious: engaging the target community in the research process increases the likelihood of success. Yet, organizations and individuals struggle with the practicality of how to do this. The typical recipe for research success includes highly focused research, centered on the priorities of the funder, led by a single investigator at an academic institution and designed to begin and end according to funding of a limited time frame. This recipe often opposes the need for shared power, responsiveness and transparency needed to truly partner with a community. And this recipe often fails to address many of the complex problems in health care and health inequity. In the academic world of “publish or perish,” a researcher may prioritize publication yet publication is rarely a route to meaningful dissemination and impact in the community. In CEnR, academics and communities collaborate and share a priority- to have a meaningful improvement of health (see Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Community Engaged Research requires many stakeholders to work together (figure compliments of ACCEL).

Let’s start somewhere

Although the terms CEnR and Community-based Participatory Research (CBPR) are used interchangeably, CEnR is an umbrella term which includes CBPR. CBPR includes the community as a full partner in all phases of research and is often considered highest level of CEnR, the holy grail of community engagement. Yet, most researchers are not CBPR researchers and most are not trained in CEnR. Yet, even investigator-driven research can and should embrace the principles and approaches of CEnR in order to improve research translation. A researcher can work with communities to identify outcomes which matter most to them, for example diabetics may care more about amputation rates than hemoglobin A1C blood test results. A researcher may be more successful in disseminating knowledge to the target community using lay language at a certain reading level as opposed to the highly technical jargon-rich language used in scientific journals and meetings. The work of Dr. Dubravcic and colleagues is essential so that children with disabilities can simply participate in risk assessments such as the YRBS which are basically used to take the pulse of risky behavior in teens. Sharing power and engaging the help at any point in the research process makes for better translational research. And translational research, that which applies discovery to improve the human condition, is the real Holy Grail we are all trying to grasp.

CEnR and its relation to Health Equity

Achieving health equity will require community engagement. Since the publication of the seminal report Unequal Treatment in 2003 there has been a steady increase in the volume of research dedicated to identifying and understanding disparities in health outcomes among underserved populations. We have learned through this body of work that disparities are the result of a complex interplay of factors including pressures from social determinants of health environment, individual behavior and the effects of institutionalized racism in the provision of care. The problem is well-documented. However, to translate that body of work into interventions that narrow the gap fundamentally requires the community to inform and guide the development and implementation of programs that will be most effective.

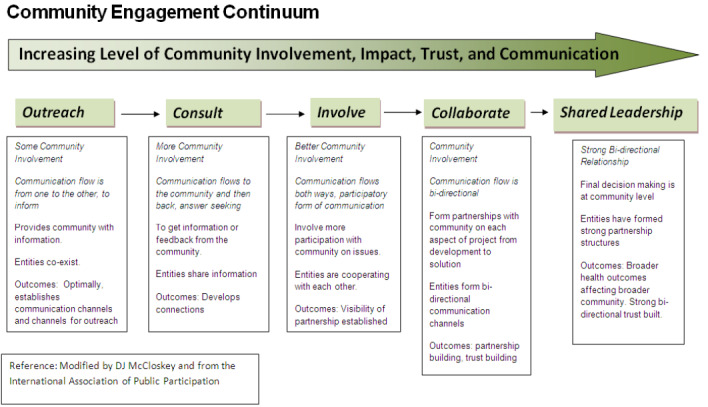

Community participation is specifically effective in ensuring interventions are locally and culturally relevant to a given populations (see Figure 2). Often the underlying causes of patterns that lead to poor health outcomes are rooted in factors that are unique to place or patterns of interaction. Dr. Chen’s work, featured in this issue, focuses on curbing violence in Wilmington; this work is a good example of engaging the community most affected by a problem to solve the problem and highlights the importance of understanding and addressing social determinants of a complex medical issue. As health care systems increasingly use community health workers to engage the community in health care and address the social determinants of health, the role of community health workers has been the subject of a great deal of research. In the work by Medaglio published in this edition, we see how, alongside other institutional supports, community health workers target specific barriers, address SDOH and help individuals to access needed medical resources.

Figure 2.

Community Engagement Continuum (ACCEL: this figure was created with support from an Institutional Development Award (IDeA) from the National Institute of General Medical Sciences of the National Institute of Health under grant number U54–GM 104941 (PI: Binder-Macleod))

Involving the community in research and intervention design leverages cultural norms and social relationships within the community, making what might have been a barrier a stepping stone to sustainable health improvement initiatives. The challenge is to form trusting relationships with community institutions that can be sustained over time, so that health outcomes can be sustained. CEnR recognizes that collaboration and advocacy are needed to address health disparity. A number of challenges make sustaining relationships difficult, including the cyclical nature of grant funding coupled with shrinking public funding for community initiatives. In the end, the road to success in decreasing disparities and making long term sustainable improvements runs through community engagement. Listen to the community voice and switch the old approach. It’s not research on us or advocacy for us, it is research and advocacy with us. Engaging those who bear the burden of a problem not only makes good sense, it makes good science.