Introduction

Despite being the most expensive in the world, the United States healthcare system continues to lag behind most comparable nations in health outcomes and quality. The IHI Triple Aim is a framework developed by the Institute for Healthcare Improvement that describes an approach to optimizing health system performance. It includes 3 dimensions: improving the patient experience of care (including quality and satisfaction); improving the health of populations; and reducing the per capita cost of health care.1 Fortunately, many states, Including Delaware, have begun investing in a strong primary care infrastructure which has be shown to be a patient-centered, high quality, cost-effective way to achieve these aims.2 Patients with access to a regular primary care physician have lower overall health care costs than those without one, and health outcomes improve.3 Primary care based health systems are associated with lower hospitalizations, less duplication in treatment, more appropriate use of technology, lower Medicare spending, higher quality of care and lower rates of healthcare disparities.3

What is Primary Care?

Put simply, primary care is the first point of contact and foundation of a person’s heath care team. The Institute of Medicine defines primary care as:

“The provision of integrated, accessible health care services by clinicians who are accountable for addressing a large majority of personal health care needs, developing a sustained partnership with patients, and practicing in the context of family and community.”4

The American Academy of Family Physicians describes primary care as a framework centered on patients, coordinated by primary care physicians (Family physicians, Internists and Pediatricians) in collaboration with specialist physicians and non-physician health care providers.

More specifically, AAFP states that “Primary care is that care provided by physicians specifically trained for and skilled in comprehensive first contact and continuing care for persons with any undiagnosed sign, symptom, or health concern (the “undifferentiated” patient) not limited by problem origin (biological, behavioral, or social), organ system, or diagnosis.

Primary care includes health promotion, disease prevention, health maintenance, counseling, patient education, diagnosis and treatment of acute and chronic illnesses in a variety of health care settings (e.g., office, inpatient, critical care, long-term care, home care, day care, etc.).”5

A common misperception is that primary care practices are only valuable for managing basic conditions like the common cold or ankle sprains when, in reality, primary care practices provide the majority of complex visits (indicated by the number of diagnoses managed during a single visit).6 As Americans live longer with growing numbers of on-going medical conditions needing to be managed in a patient-centered, cost-effective way, it will be critical for society to continue investing in and strengthening our primary care foundation.

THE GROWING BURDEN OF CHRONIC DISEASE

What is Chronic Disease?

The U.S. National Center for Health Statistics defines a chronic disease as a medical condition lasting 3 months or more. In general, chronic diseases remain permanently, can be managed once they are present but cannot typically be prevented by vaccines, cured by medication, nor do they spontaneously disappear. Health damaging behaviors including obesity, tobacco use, lack of physical activity, and poor eating habits are major contributors to the leading chronic diseases. The standard list of chronic medical conditions typically includes arthritis, current asthma, cancer, cardiovascular disease, chronic obstructive pulmonary disease, and diabetes, but a number of medical conditions including HIV/AIDS and chronic kidney disease are becoming increasingly prevalent.7

The Rise of Chronic Disease

Over 85% Americans over 65 years of age have at least one chronic health condition. Women in all age groups are more likely than men to have one or more, two or more, or three or more chronic conditions.7 In 2012 about 50% of all adults were living with a chronic medical condition and 25% of those adults carried a diagnosis of more than one.8 133 million Americans were living with at least one chronic condition in 2005. In 2020, this number is expected to grow to 157 million. In 2005, sixty-three million people had multiple chronic illnesses, and that number will reach eighty-one million in 2020.9,10

Chronic Disease in Delaware

Delaware is ranked as the 32nd healthiest state in American’s Health Rankings® 2015 Edition, produced by the United Health Foundation with its partners at the American Public Health Association and Partnership for Prevention. Chronic diseases are the leading causes of death nationally and in Delaware. Cardiovascular disease (including heart disease and stroke) remains the leading cause of death followed by cancer, lung diseases and diabetes.11 Table 1 provides a brief comparison of common chronic disease risk factors for Delaware and the US.

Table 1. Prevalence (in percentage) of Selected Risk Factors: DE vs UC (2008 or 2007)12.

| Risk Factor | DE | US (median) |

|---|---|---|

| Cigarette Smoking | 17.8 | 18.4 |

| Obesity | 27.8 | 26.7 |

| Eat 5 or More Fruits/Veg a day (2007) | 21.4 | 24.4 |

| Recommended Physical activity (2007) | 47.9 | 49.5 |

| Prevalence of Diabetes | 8.3 | 8.3 |

| Prevalence of Current Asthma | 9.6 | 8.8 |

| Ever Had a Heart Attack | 4.5 | 4.2 |

| Told you have Coronary Artery Disease | 4.7 | 4.3 |

The most recent Behavioral Risk Factor Survey showed that, in general, Delawareans fare worse than then average American Diabetes prevalence increased from 4.9% in 1991 to 8.3% in Delaware in 2008. Diabetes prevalence is higher among men than women, and higher among African Americans than among non-Hispanic whites. Obesity prevalence also is higher among men and African Americans, and obesity is a major risk factor for type 2 diabetes. In 2008, 13.6% of Delaware adults reported ever being told by a doctor or health professional that they had or have asthma. Young adults are more likely to report current asthma than older adults. People with low incomes and lower educational levels also are more likely to have current asthma. 4.5% of Delaware adults reported having had, and survived, a heart attack. More men than women report having had a heart attack: 5.6% of men compared to 3.4% of women. There were no statistically significant differences by race or ethnicity; however, people age 65 and older reported by far the highest prevalence at 15.7%. 4.7% of adults in the state reported being told that they have angina or coronary artery disease. Non-Hispanic whites were most likely to report diagnosed coronary artery disease, followed by Hispanics and African Americans. 2.9% of Delaware adults reported having been told they had a stroke, and while there were no statistically significant differences by gender or race, age was once again is a significant factor. While less than 2% of adults under 45 reported having a stroke, 3.3% of adults 55-64 and 8.2% of adults over 65 reported a stroke.

Of note, Delaware’s population is aging more rapidly than the US. Delaware exceeded the national growth rates of 33% for ages 60-84 and 40% for ages 85 or older. From 2000 to 2010-14, the number of people 60-84 years old grew 45% in Delaware, and the number of people 85 or older rose 66%. Younger age groups also grew but more slowly, with 6% growth in people under 20 and 20-39 years old, and 21% in those 40-59. Within Delaware, Sussex County had particularly strong growth in the 85 and older population at 98%, while the City of Wilmington actually lost population in the two youngest age groups.11

The CDC reports that over 85% of all costs of healthcare are related to the treatment of a “chronic medical condition”. The total cost of treating heart disease in 2010 was over 300 billion and over 200 billion for the treatment of diabetes.

Access to Primary Care

Access to health care is critical for a community’s well- being. In Delaware, 10% of residents lacked health insurance in 2014, below the national rate of 16% and below rates in comparable areas. In addition, since the passage of the Affordable Care Act, insurance coverage has expanded. Nearly 25,000 Delaware residents signed up for a qualified health plan on HealthCare.gov between Nov. 15, 2014, and Feb. 15, 2015, or more than half the state’s potential pool of 48,000 people. Of course, having insurance is only part of achieving access. Patients must also have available health care resources.

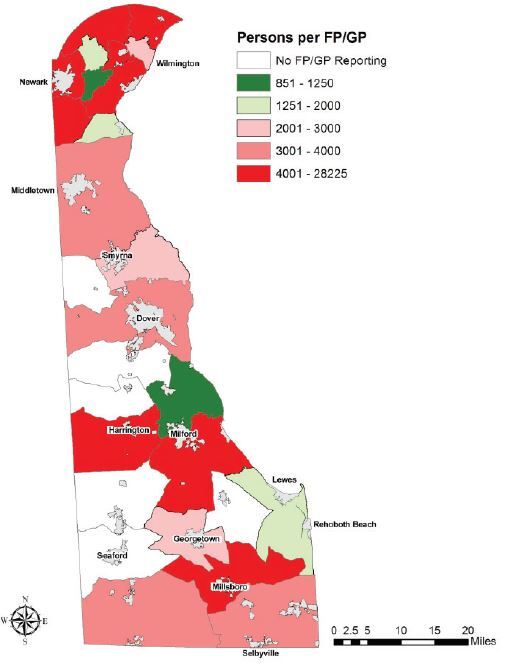

The Division of Public Health’s (DPH) Office of Primary Care (OPC) received a “Primary Care Services Resource Coordination and Development Primary Care Office” (PCO) grant from the federal Health Resources and Services Administration, U.S. Department of Health and Human Services to assess the primary care health needs of Delaware. The report addresses Delaware populations and areas with unmet health care needs, disparities, and access barriers to support designations of health professional shortage areas and the recruitment and retention of primary care providers. Figure 1 shows the distribution of primary care physicians in Delaware. Note these numbers include OB/Gyn as primary care physicians. About 1,271 persons were served by each full-time- equivalent (FTE) primary care physician in 2013. The number of FTE primary care physicians remained unchanged since the last survey in 2010; however, it does not represent a stagnant pool of physicians. There was a slight increase in Kent and New Castle counties and a slight decrease in Sussex County.

Figure 1.

Distribution of Primary Care Physicians in Delaware (2014)

Overall 72% of physicians reported expecting to remain active in five years; however, that number was only 58% in Kent County. Between 84 percent and 87 percent of primary care physicians reported in 2013 that they were accepting new patients. Despite the appearance of an adequate number of physicians and open panels, patients in Delaware across all 3 counties are waiting longer than in the past for non-emergent appointments. On average, an established patient will wait about 17 days and a new patient will wait 32 days.13

The Evolving Role of the Primary Care Physician

Since 2013, stakeholders across the state have been engaged with the Delaware Center for Health Innovation in securing funding, developing and implementing Delaware’s State Health Innovation Plan. A cornerstone to the plan is supporting primary care practices making the necessary transformations to meet the population’s growing complex chronic health needs.

The Patient Centered Medical Home

The medical home concept originated in 1967 when the American Academy of Pediatrics (AAP) introduced it to describe primary care that is accessible, family-centered, coordinated, comprehensive, continuous, compassionate, and culturally effective.

The definition has evolved yet remains true to the original concept. The Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality (AHRQ), describes the medical home as a model to improve health care in America by transforming how primary care is organized and delivered by encompassing five functions and attributes: comprehensive care, patient-centered, coordinated care, accessible services, quality and safety.14 As insurers began to look at the PCMH model as a reliable way of identifying practices and clinicians providing enhanced services and likely producing improved quality and care coordination, accrediting bodies began providing certifications and recognitions for achieving PCMH status. The most widely recognized PCMH accreditation organizations include the National Committee for Quality Assurance (NCQA) and the Joint Commission. The first Delaware practice, Christiana Care Family Medicine Center in Wilmington, was recognized in 2011 by the NCQA, and since then hundreds of clinicians across the state have been recognized. While the DCHI supports a number of evidence-based models of practice transformation, the core principles of the PCMH are evident. Table 2 lists the 9 essential capabilities of Primary Care practices set forth in the State Innovation model. It is the vision of DCHI that all Delaware primary care practices will exhibit these abilities and be financially supported across all payers including Medicare, Medicaid and commercial programs.

Table 2. Delaware State Innovation Plan 9 Capabilities of Primary Care Practices.

| Panel management | Understanding the health status of the patient panel and setting priorities for outreach and care coordination based on risk. Practices define and identify the highest-risk members of the patient panel. Providers develop and execute on an outreach plan for identified high-risk patients. The practice prioritizes these patients for care coordination, appropriate care interventions, and self-management education. |

|---|---|

| Access improvement | Introducing changes in scheduling, after-hours care, and/or channels for consultation to expand access to care. Providers develop and implement approaches to expanding access to care, and adapt based on identified patient needs and preferences. Approaches to expanding access may include after-hours and same-day appointments, phone consultations with licensed health professionals, and consultation by email, text or other technology. |

| Care management | Proactive care planning and management for high risk patients. Practices identify high-risk patients, develop team-based interventions to deliver appropriate care, coordinate resources external to the practice when necessary, and track progress. Providers use information on patients’ health risks and tailor responses accordingly. |

| Team-based care coordination | Integrating care across providers within the practice, across the referral network, and in the community. Practices identify a multi-disciplinary care team that may include physicians, nurses, medical assistants, pharmacists, social workers, and other clinical staff. Practices coordinate activities and promote communication across the team involved in a patient’s care and integrate specific approaches for this collaboration into their operating model (e.g., by setting up case conferences). Practices also develop systems to coordinate with external stakeholders, such as outpatient specialists, hospitals, emergency rooms and urgent care centers, rehabilitation centers, community resources, and the patient’s support system. Coordination improves care planning, diagnosis and treatment, management through transitions of care, and patient coaching to improve treatment adherence. This capability includes integration of primary care practices with behavioral health providers where possible. |

| Patient engagement | Outreach, health coaching, and medication management. Practices develop a culture centered on understanding and responding to patient needs. Further, practices offer patient engagement tools and self-management programming. Approaches may include patient education, incentives, and/or technology enablement. Practices develop and execute on patient engagement plans focusing on high-risk patients in particular. |

| Performance management | Using reports to drive improvement and participation in value-based payment models. Practices integrate a performance management approach into their daily operations, building on Delaware’s Common Scorecard. Performance management involves tracking relevant metrics, utilizing performance measurement data to inform, design, and/or improve interventions; and developing a culture of continuous improvement. |

| Business process improvement | Budgeting and financial forecasting, practice efficiency and productivity, and coding and billing. Practices implement business management and financial planning processes required to participate in incentive payment structures and shared savings models. Practices incorporate budgeting and financial forecasting tools to: 1) develop quarterly and annual budgets; 2) forecast resource allocation required to operate during and after transformation; and 3) estimate financial impact of incentive payments. Practices may consider making structural changes in their workflows to ensure efficient, productive team-based care delivery. Practices also adjust billing and coding processes where necessary to support transformation, including reporting requirements for performance measurement on the Common Scorecard. |

| Referral network management | Promoting use of high-value providers and setting expectations for consultations. Practices seek out timely information on providers that are part of their patients’ extended care teams from open sources as well as Delaware stakeholders (e.g., health systems, payers, other practices) to identify providers that deliver care consistent with the goals of the Triple Aim. Practices regularly strengthen the performance of their referral network through a number of approaches that may include, for example, setting clear expectations for partners, and establishing and tracking performance metrics. |

| Health IT enablement | Optimize access and connectivity to clinical and claims data to support coordinated care. To coordinate care, practices use health IT tools, including electronic health records, practice management software, and data from DHIN. Practices effectively interpret data, use health IT as a component of their workflow, and support expansion of the Community Health Record with clinical data. |

Adapted from DCHI Primary Care Practice Transformation White Paper http://www.dehealthinnovation.org/Content/Documents/DCHI/DCHI-Primary-Care-Practice-Transformation.pdf (Accessed 2-19-2017).

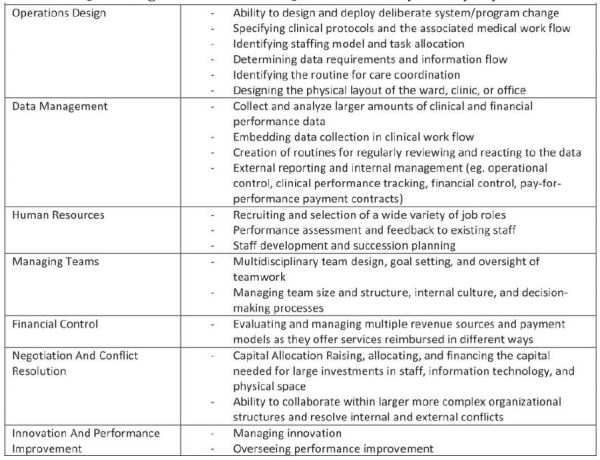

A New Role for Primary Care Physicians

Re-envisioning primary care practices and their role in chronic disease management means a primary care physicians will need a new set of skills. In addition to an expectation of regularly managing increasingly complex patients- multiple medical conditions, extensive medication lists and sizable teams of care providers across specialties and sites, primary care physicians will need an evolving set of leadership and practice management skills. Figure 2 highlights some these expanded duties. An overwhelming list when considered the roles of one physician, but as the lead of a multi-disciplinary team in partnership with the patient, it is possible to re-envision a new model for delivering primary care services.

Figure 2.

Sample Management and Leadership Skills Needed By Primary Physicians

Adapted from Bohmer RM. Managing the new primary care: the new skills that will be needed. Health Aff (Millwood). 2010 May;295:1010-4. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2010.0197.

Primary Care Practice Innovations to Improve Chronic Disease

In addition to re-considering the role of the physicians, the practice will need to evolve to meet the chronic disease management needs. There many models and tools currently available to us which can assist our patients in achieving the best possible outcomes.

Alternate visit models

Many practices are beginning to explore the benefits of group and mini-group visits vs. the traditional one- on-one visit model. One of the greatest advantages to group visits is that they allow for the patients to interact directly with other people who understand what they are going through. This sense of comradery enables the patients to feel less isolated and allows for collaborative goal-setting. Multiple randomized trials studying the effectiveness of the group visit model have shown that group visits show clinically significant improvements in medical, psychological and behavioral outcomes for patients with chronic disease.15

Telehealth visits are another innovation in primary care that have become a useful tool for many providers in managing those with chronic diseases. Many of the services that primary care providers offer their patients do not require a physical examination, such as routine follow up visits, management of medications and labwork, and counseling and educational services. A study conducted in 2014 showed that telehealth visits can provide quality patient centered care while also increasing access for patients to their healthcare providers.16 Telehealth visits allow patients to receive many vital services without having to leave the comfort of their homes which alleviates the stress of getting transportation to and from the physician’s office.

Another visit model which has recently increased in popularity is the home visit. It is estimated that house calls increased from 1.4 million in 1999 to 2.3 million in 2009, and are expected to continue to increase in number due to an estimated 70 million Americans who will be over the age of 65 by 2030. Not only can home visits significantly increase patient safety, they foster a deeper trust and connection between provider and patient which will greatly increase the quality of care that the patients receive.17

Direct Primary Care is another type of alternative visit model that has gained popularity recently amongst patients and providers. This alternative to a traditional fee-for-service model allows physicians to charge a monthly flat fee, which covers either all or most primary care services.18 Patients benefit by having increased access to their providers with longer office visits and more individualized attention. Physicians benefit by having decreased practice overhead, no insurance filing as well as decreased patient load and more time spent with each patient.

Disease Management Programs Improving Self-management

Disease management programs are a series of measures designed to improve quality of life and clinical outcomes for patients with chronic illness.19 A good disease management program will reach out to patients in between visits with educational materials, reminders and support. These specific programs utilize a proactive patient centered approach to provide assistance in between provider visits with the ultimate goal of enhancing the patients own self-management of their disease.

Many practices are beginning to use care guides to assist their chronically ill patients. These non-clinical laypeople, are trained to work with patients with chronic illness. Care Guides are able to instruct and motivate patients with aspects of their overall health like nutrition, fitness and stress management. They receive a short period of training in motivational interviewing, behavioral techniques and common chronic diseases. Care guides can offer individualized attention through evidence-based care, which gives patients the autonomy to manage their own diseases more effectively.

Similar to care guides, the role of the health coach in primary care is also beginning to become popular.

The difference between the two positions is that health coaches are typically already part of the clinical staff. Whether they are an MA, a nurse or a Physician Assistant, health coaches also work one-on-one with patients to focus on education and compliance to empower patients and positively affect disease outcomes.

The role of the case manager within primary care can be another beneficial tool for many patients struggling to manage their chronic diseases. Case managers can help educate, motivate and assist with coordinating the care for the most complex of patients, which ultimately can give them the tools they need to manage their own care more successfully.

Health Information Technology

With the ever changing landscape of primary care, the integration of various health information technologies has become a necessary part of managing chronic disease. The electronic health record (EHR), although certainly not without its faults, can be a useful tool for healthcare providers to monitor the quality of care they are providing on a daily basis. Not only does the EHR provide a centralized database where the physician can keep track of their patient panel, it allows physicians to have electronic registries of their chronically ill patients, which can provide reminders about various testing and screening tools that may otherwise be unintentionally overlooked.20

In addition, many EHR’s offer a patient portal feature, which allows patients to schedule appointments, request prescription refills, look at lab and imaging results, and directly message healthcare providers via a secure messaging feature. Although they have been met with mixed reviews both from providers and patients, studies have shown that patient portals increase convenience for patients and allow direct access to providers without the hassle of waiting on the telephone for excessive periods of time.21

When assessing the technological innovations in medicine, it is important not to overlook the usefulness of the smartphone, the tablet and their various applications. A study conducted in 2015 showed that mobile health apps were able to increase access for patients to medical information and provide social support to those dealing with chronic illness.22 The further development of this type of technology has the ability to increase health literacy and give patients the power to manage their chronic diseases in ways that are convenient for them.

Chronic Disease Care: A Partnership between Patients and PCP

Innovation within primary care can strive to ultimately develop a stronger partnership between patients and their primary care physicians. As we allow our patients to access their doctors and their care teams with more ease, we allow them to get real time information offering opportunity to integrate change more quickly. The patients have a sense of empowerment. They feel a sense of ownership of their health and they have a better understanding of what their own role is, how their choices are impacting their health and what they can control themselves. They also feel more dedication from their physician. Our patients and physicians will have a better understanding of one another and where advice, decisions and information is coming from. The importance of shared decision making has long been accepted. We must continue to strive to find the best practices to do this with and for our patients.

References:

- 1.Improvement, I. f. (2017, 2 19). IHI Triple Aim. Retrieved from http://www.ihi.org/Engage/ Initiatives/TripleAim/Pages/default.aspx

- 2.Innovation, D. C. (2017, 2 19). Retrieved from http://www.dehealthinnovation.org/

- 3.Starfield, B., Shi, L., & Macinko, J. (2005). Contribution of primary care to health systems and health. The Milbank Quarterly, 83(3), 457–502. 10.1111/j.1468-0009.2005.00409.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Medicine, I. O. (1994). SUMMARY. In I. O. Medicine, Defining Primary Care: An Interim Report. Washington, DC: The National Academies Press. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Physicians, A. A. (2017, 2 19). Primary Care Policy. Retrieved from http://www.aafp.org/ about/policies/all/primary-care.html

- 6.Moore, M., Gibbons, C., Cheng, N., Coffman, M., Petterson, S., & Bazemore, A. (2016, August). Complexity of ambulatory care visits of patients with diabetes as reflected by diagnoses per visit. Primary Care Diabetes, 10(4), 281–286. 10.1016/j.pcd.2015.11.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Statistics, C. C. (2017, Feb 19). Percent of U.S. Adults 55 and Over with Chronic Conditions. Retrieved from https://www.cdc.gov/nchs/health_policy/adult_chronic_conditions.htm

- 8.Ward, B. W., Schiller, J. S., & Goodman, R. A. (2014, April 17). Multiple chronic conditions among US adults: A 2012 update. Preventing Chronic Disease, 11, E62. 10.5888/pcd11.130389 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Green, S. W. (2000). Projection of Chronic Illness Prevalence and Cost Inflation. Santa Monica, Calif.: RAND. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bodenheimer, T., Chen, E., & Bennett, H. D. (2009, January-February). Confronting the growing burden of chronic disease: Can the U.S. health care workforce do the job? Health Affairs (Project Hope), 28(1), 64–74. 10.1377/hlthaff.28.1.64 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Statistics, D. C. (2017, 2 19). Delaware Vital Statistics Annual Report 2014. Retrieved from http://dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/hp/2014.html

- 12.DE Health and Social Services. Behavioral Risks in Delaware 2007-2008. Retrieved February 15, 2017, from http://www.dhss.delaware.gov/dhss/dph/dpc/files/brfsreport07-08.pdf

- 13.Care, D. D. (2016, 2). Delaware Primary Care Health Needs Assesment 2015. Retrieved from http://www.dhss.delaware.gov/dph/hsm/files/depchealthneedsassessment2015.pdf

- 14.Quality, A. f. (2017, 2 19). Patient Centered Medical Home Resource Center. Retrieved from Defining PCMH: https://pcmh.ahrq.gov/page/defining-pcmh

- 15.Wong, S. B. (2015). Incorporating Group Medical Visits into Primary Healthcare: Are There Benefits? Healthcare Policy | Politiques de Santé, 11(2), 27-42. doi: doi: [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 16.Heckemann, B., Wolf, A., Ali, L., Sonntag, S. M., & Ekman, I. (2016, March 2). Discovering untapped relationship potential with patients in telehealth: A qualitative interview study. BMJ Open, 6(3), e009750. 10.1136/bmjopen-2015-009750 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Unwin, B. K., & Tatum, P. E., III. (2011, April 15). House calls. American Family Physician, 83(8), 925–938. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Physicians, A. A. (2017, Feb 19). Direct Primary Care. Retrieved from DPC: An Alternative to Fee-for-Service: http://www.aafp.org/practice-management/payment/dpc.html

- 19.Physicians, A. A. (2017, Feb 19). Disease Management. Retrieved from http://www.aafp.org/ about/policies/all/disease-management.html

- 20.Zulman, D. M., Jenchura, E. C., Cohen, D. M., Lewis, E. T., Houston, T. K., & Asch, S. M. (2015, August). How can eHealth technology address challenges related to multimorbidity? Perspectives from patients with multiple chronic conditions. Journal of General Internal Medicine, 30(8), 1063–1070. 10.1007/s11606-015-3222-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kruse, C. S., Argueta, D. A., Lopez, L., & Nair, A. (2015, February 20). Patient and provider attitudes toward the use of patient portals for the management of chronic disease: A systematic review. Journal of Medical Internet Research, 17(2), e40. 10.2196/jmir.3703 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bauer, A. M., Thielke, S. M., Katon, W., Unützer, J., & Areán, P. (2014, September). Aligning health information technologies with effective service delivery models to improve chronic disease care. Preventive Medicine, 66, 167–172. 10.1016/j.ypmed.2014.06.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]