Abstract

Head and neck squamous carcinoma (HNSCC) is highly infiltrated by immune cells, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and myeloid lineage cells. In the tumor microenvironment, tumor cells orchestrate a highly immunosuppressive microenvironment by secreting immunosuppressive mediators, expressing immune checkpoint ligands, and downregulating human leukocyte antigen expression. In the present study, we aimed to comprehensively profile the immune microenvironment of HNSCC using gene expression data obtained from public database. We calculated enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types based on gene expression data of HNSCC tissues and adjacent non-cancer tissues. Based on these scores, we performed non-supervised clustering and identified three immune signatures—cold, lymphocyte, and myeloid/dendritic cell (DC)—based on the clustering results. We then compared the clinical and biological features of the three signatures. Among HNSCC and non-cancer tissues, human papillomavirus (HPV)-positive HNSCCs exhibited the highest scores in various immune cell types, including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, B cells, plasma cells, basophils, and their subpopulations. Among the three immune signatures, the proportions of HPV-positive tumors, oropharyngeal cancers, early T tumors, and N factor positive cases were significantly higher in the lymphocyte signature than in other signatures. Among the three signatures, the lymphocyte signature showed the longest overall survival (OS), especially in HPV-positive patients, whereas the myeloid/DC signature demonstrated the shortest OS in these patients. Gene set enrichment analysis revealed the upregulation of several pathways related to inflammatory and proinflammatory responses in the lymphocyte signature. The expression of PRF1, IFNG, GZMB, CXCL9, CXCL10, PDCD1, LAG3, CTLA4, HAVCR2, and TIGIT was the highest in the lymphocyte signature. Meanwhile, the expression of PD-1 ligand genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2 was highest in the myeloid/DC signature. Herein, our findings revealed the transcriptomic landscape of the immune microenvironment that closely reflects the clinical and biological significance of HNSCC, indicating that molecular profiling of the immune microenvironment can be employed to develop novel biomarkers and precision immunotherapies for HNSCC.

Subject terms: Immunology, Tumour immunology

Introduction

Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma (HNSCC) is the sixth most common malignant tumor worldwide1,2. In addition to tobacco-derived carcinogens and excessive alcohol consumption, infection with oncogenic strains of human papillomavirus (HPV) has been recognized as a major risk factor for developing HNSCCs, mainly oropharyngeal cancers3,4. Despite ongoing improvements in therapeutic strategies, including surgery, chemotherapy, and radiotherapy, the 5-year survival rate remains 66%. Recently, cancer immunotherapy has been developed as an additional approach for various cancer types, including HNSCC5–7. The programmed cell death 1/programmed cell death ligand 1 (PD-1/PD-L1) axis is a crucial target for immune checkpoint therapies8. In clinical settings, anti-PD-1 antibodies have been widely employed for treating recurrent or metastatic HNSCC; however, survival benefits have been observed in only 20–30% of patients. Accordingly, novel biomarkers have been widely investigated to improve the efficacy of immunotherapies.

In the tumor microenvironment (TME), various stromal cells such as immune cells, fibroblasts, and endothelial cells exist and interact with tumor cells9,10. HSNCC is highly infiltrated by immune cells, including tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes (TILs) and myeloid lineage cells11,12. In the TME of HNSCC, tumor cells reportedly orchestrate a highly immunosuppressive state by secreting immunosuppressive mediators, expressing immune checkpoint ligands, and downregulating human leukocyte antigen expression13,14. These tumor cell behaviors result in the dysfunction and exhaustion of cytotoxic T lymphocytes (CTLs), as well as increased infiltration and activation of immunosuppressive cell types, such as regulatory T cells (Tregs), tumor-associated macrophages, and myeloid-derived suppressor cells (MDSCs)15. As immune checkpoint agents target the interaction between tumor cells and immune cells, a comprehensive analysis of the complex state of the immune microenvironment would be beneficial for developing new biomarkers and precision immunotherapies.

In the present study, we aimed to comprehensively profile the immune microenvironment of HNSCC using gene expression data obtained from public database. We calculated the cell enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types based on RNA-seq data of both HNSCC tissues and adjacent non-cancer tissues. Based on these scores, we performed non-supervised clustering and identified three immune signatures—cold, lymphocyte, and myeloid/dendritic cell (DC)—based on clustering results. Finally, the clinical and biological features of the three signatures were compared.

Results

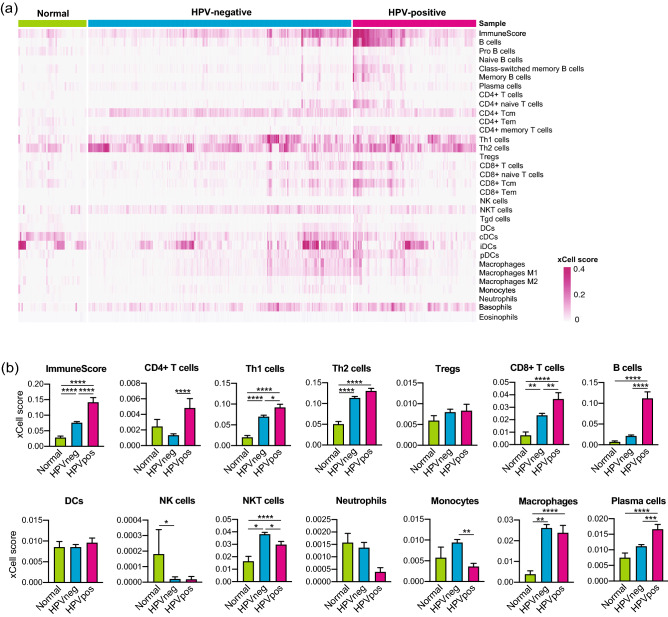

HPV-positive HNSCCs exhibited upregulated enrichment of various immune cells

We calculated the enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types among 520 HNSCCs and 44 normal samples (Fig. 1, Suppl. Fig. 1) in the TCGA cohort. HPV-positive HNSCCs exhibited the highest scores for various immune cell types, including CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, B cells, plasma cells, basophils, as well as their subpopulations. Normal samples exhibited the lowest scores for several cell types. Similarly, we calculated the enrichment scores among 270 HNSCCs in the GSE65858 cohort (Suppl. Fig. 3). In consistent with the TCGA cohort, HPV-positive tumors exhibited higher scores for various immune cell types than HPV-negative tumors.

Figure 1.

Enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types in normal tissues and HNSCCs. (a) Heat map of xCell enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types in 44 normal tissues, 97 HPV-positive HNSCCs, and 423 HPV-negative HNSCCs of TCGA cohort. (b) Bar graphs of enrichment scores of major immune cell types shown in (a). HNSCC Head neck squamous cell carcinoma, HPV Human papillomavirus, HPVneg HPV-negative, HPVpos HPV-positive, DC Dendritic cells. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

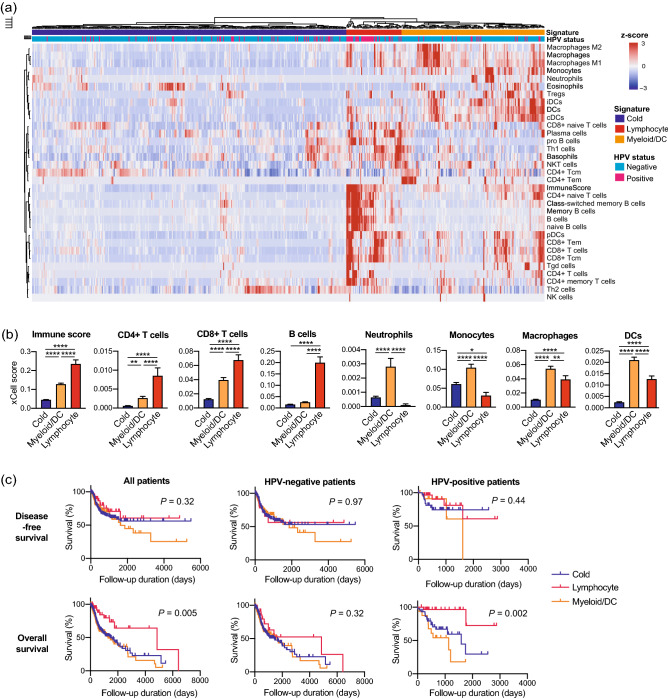

The lymphocyte signature correlated with clinical parameters and better prognosis

Based on hierarchical clustering results, we segregated 520 HNSCCs in the TCGA cohort into three immune signatures (Fig. 2a). The lymphocyte signature was characterized by the enrichment of CD4+ T cells, CD8+ T cells, B cells, and plasma cells (Fig. 2b, Suppl. Fig. 2). The myeloid/DC signature exhibited enrichment of neutrophils, macrophages, monocytes, DCs, Tregs, and eosinophils (Fig. 2b, Suppl. Fig. 2). Table 1 represents correlations between the immune signatures and clinical parameters. The proportion of HPV-positive patients (59%) was significantly higher in the lymphocyte signature than in other signatures. Regarding primary lesions, the proportion of the oropharynx (50%) was higher in the lymphocyte signature than in other signatures. The proportion of patients with early T factor (63%) was higher in the lymphocyte signature than in other signatures. Furthermore, the proportion of N factor-positive patients (61%) was higher in the lymphocyte signature than in other signatures. No difference was observed between the immune signatures and the M factor/tumor-node-metastasis (TNM) stage. Univariate survival analyses revealed that the lymphocyte signature showed the longest overall survival (OS) among the three signatures, especially in HPV-positive patients (Fig. 2c). The myeloid/DC signature showed the shortest OS among the three signatures in HPV-positive patients. No difference in disease-free survival (DFS) was observed between the immune signatures. Multivariate regression analyses revealed that the lymphocyte signature was an independent prognostic factor for better OS (Table 2).

Figure 2.

The lymphocyte signature correlates with a favorable prognosis. (a) Heat map showing non-supervised hierarchical clustering of 520 HNSCCs of TCGA cohort based on enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types. (b) Bar graphs of enrichment scores upregulated in the lymphocyte signature or myeloid/DC signature. (c) Kaplan–Meier survival curves based on the three immune signatures. Disease-free survival was evaluated in all patients (n = 429), HPV-negative patients (n = 348), and HPV-positive patients (n = 81). Overall survival was evaluated in all patients (n = 495), HPV-negative patients (n = 403), and HPV-positive patients (n = 92). HNSCC Head neck squamous cell carcinoma, HPV Human papillomavirus, DC Dendritic cells. *, P < 0.05; **, P < 0.01; ****, P < 0.0001.

Table 1.

Relationship between immune cell signature and clinical parameters in 520 patients with HNSCC.

| Variables | Immune cell signature | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Cold (n = 319) | Myeloid/DC (n = 145) | Lymphocyte (n = 56) | p value | |

| HPV status | ||||

| Negative | 271 | 129 | 23 | < 0.0001 |

| Positive | 48 | 16 | 33 | |

| Primary lesion | ||||

| Hypopharynx | 6 | 3 | 1 | < 0.0001 |

| Larynx | 86 | 24 | 6 | |

| Oral cavity | 210 | 113 | 28 | |

| Oropharynx | 17 | 5 | 21 | |

| T factor | ||||

| T0-2 | 120 | 55 | 35 | 0.002 |

| T3-4 | 199 | 90 | 21 | |

| N factor | ||||

| Negative | 143 | 57 | 13 | 0.0005 |

| Positive | 165 | 79 | 34 | |

| Unknown | 11 | 9 | 9 | |

| M factor | ||||

| M0 | 307 | 142 | 55 | 0.582 |

| M1 | 3 | 1 | 1 | |

| Unknown | 9 | 2 | 0 | |

| TNM stage | ||||

| I-II | 67 | 33 | 11 | 0.86 |

| III-IV | 252 | 112 | 45 | |

HNSCC Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, HPV Human papillomavirus, TNM Tumor-node-metastasis, DC Dendritic cell.

Table 2.

Univariate and multivariate survival analyses of OS and DFS in HNSCC patients.

| Variables | Disease free survival | Overall survival | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Univariate | Multivariate | Univariate | Multivariate | |||

| p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | p value | HR (95% CI) | p value | |

| HPV status | ||||||

| Negative | 0.027 | 1 | 0.037 | 0.132 | ||

| Positive | 0.566 (0.331–0.967) | |||||

| Primary lesion | ||||||

| Hypopharynx | 0.158 | 0.140 | ||||

| Larynx | ||||||

| Oral cavity | ||||||

| Oropharynx | ||||||

| T factor | ||||||

| T0-2 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.132 | 0.0002 | 1 | 0.016 |

| T3-4 | 1.474 (0.889–2.444) | 1.839 (1.118–3.026) | ||||

| N factor | ||||||

| Negative | 0.06 | 0.037 | 1 | 0.217 | ||

| Positive | 1.267 (0.870–1.846) | |||||

| M factor | ||||||

| M0 | 0.26 | 0.001 | 1 | 0.0005 | ||

| M1 | 6.263 (2.215–17.707) | |||||

| TNM stage | ||||||

| I–II | 0.009 | 1 | 0.254 | 0.009 | 1 | 0.483 |

| III–IV | 1.457 (0.763–2.782) | 0.788 (0.405–1.534) | ||||

| Immune signature | ||||||

| Cold | 0.320 | 0.005 | 1 | |||

| Lymphocyte | 0.362 (0.172–0.763) | 0.008 | ||||

| Myeloid/DC | 1.077 (0.780–1.486) | 0.654 | ||||

DFS Disease free survival, OS Overall survival, HNSCC Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma, HR Hazard ratio, CI Confidence interval, DC Dendritic cell.

Alternatively, we performed hierarchical clustering of the GSE65858 cohort and confirmed that HNSCCs cases were also divided into three immune signatures (Suppl. Fig. 4a,b). In addition, correlations between the immune signatures and clinical parameters, including HPV status and primary lesions, exhibited same trends as the TCGA cohort (Suppl. Table 1). Although survival analyses showed no significant difference between the immune signatures, the myeloid/DC signature tended to correlate with shorter OS (Suppl. Fig. 4c). Moreover, in HPV-negative patients, the myeloid/DC signature significantly correlated with shorter DFS and OS.

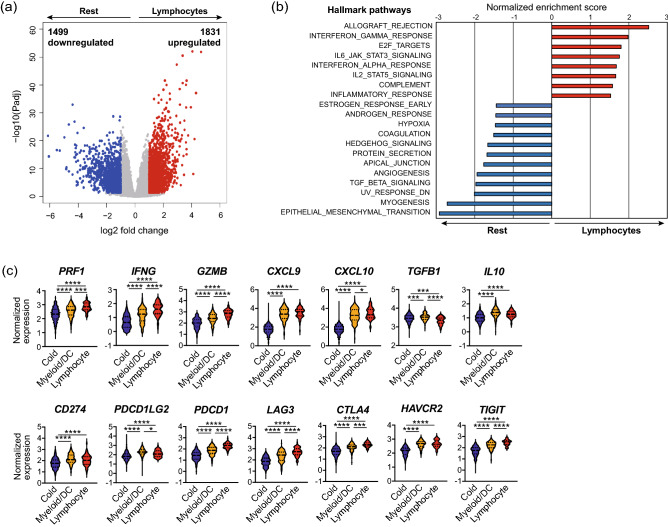

The lymphocyte signature correlated with upregulated inflammatory pathways

Based on these findings, we then focused on the transcriptomic significance of the lymphocyte signature. In the TCGA cohort, 3330 differentially expressed genes (DEGs), including 1831 upregulated and 1499 downregulated genes, were identified in the lymphocyte signature (Fig. 3a, Suppl. Table 2). Additionally, we performed gene set enrichment analysis (GSEA) to identify pathways upregulated in the lymphocyte signature (Fig. 3b). In the lymphocyte signature, 8 hallmark pathways were upregulated, whereas 12 were downregulated (false discovery rate ˂ 0.05). Several pathways associated with inflammatory and proinflammatory responses, such as allograft rejection, interferon (IFN) gamma response, interleukin (IL) 6-Janus kinase (JAK)-signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT) 3 signaling, interferon-alpha response, IL2 STAT5 signaling, and complement, were upregulated in the lymphocyte signature. Meanwhile, several pathways representing malignant features of HNSCCs, including hypoxia, angiogenesis, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β signaling, and epithelial-mesenchymal transition, were downregulated in the lymphocyte signature. Similarly, we also performed GSEA with the GSE65858 cohort, confirming the upregulation of similar pathways in the lymphocyte signature (Suppl. Fig. 5a).

Figure 3.

The lymphocyte signature correlated with activated cytotoxic T cell response. (a) Volcano plot of differentially expressed genes in the lymphocyte signature of TCGA cohort. Red dots represent upregulated genes (Padj < 0.05, log2FC > 1), whereas blue dots represent downregulated genes (Padj < 0.05, log2FC < − 1). (b) Upregulated and downregulated hallmark pathways in the lymphocyte signature obtained by GSEA (FDR < 0.05). (c) Violin plots of normalized expression of immune-related genes. GSEA Gene set enrichment analysis, FDR False discovery rate. *, P < 0.05; ***, P < 0.001; ****, P < 0.0001.

The lymphocyte signature correlated with activated cytotoxic T cell response

We investigated the expression of immune-related genes to compare cytotoxic T cell responses across the three immune signatures (Fig. 3c). The lymphocyte signature demonstrated the highest expression of genes related to cytotoxic T cell responses, including PRF1, IFNG, GZMB, CXCL9, and CXCL10. Additionally, the expression of immune checkpoint genes, including PDCD1, LAG3, CTLA4, HAVCR2, and TIGIT, was the highest in the lymphocyte signature. Meanwhile, the expression of PD-1 ligand genes CD274 and PDCD1LG2 was the highest in the myeloid/DC signature, which also revealed the highest expression of immunosuppressive genes, TGFB1 and IL10. Similarly, we confirmed these results in the GSE65858 cohort (Suppl. Fig. 5b).

Discussion

Recent advances in bioinformatics and the accumulation of public genomic databases have enabled the comprehensive genomic characterization of cancers in a large cohort16. In the present study, we elucidated the transcriptomic landscape of the immune microenvironment that closely reflects the clinical and biological significance of HNSCC. Our results suggest that molecular profiling of the immune microenvironment can potentially help develop new biomarkers and precision immunotherapies.

The comparison of immune cell enrichment scores revealed high infiltration of various immune cells into HNSCC tissues, especially in HPV-positive HNSCCs. The scores of various TILs were higher in HNSCCs than in normal tissues. Among TILs, CD8+ T cells are the main subset of CTLs and play vital roles in tumor eradication. CD8+ T cells, as well as their subset CD8+ central memory T cells (Tcm) and CD8+ effector memory T cells (Tem), represented significantly higher scores in HPV-positive HNSCCs than in other groups, indicating a highly activated CTL function in the TME of HPV-positive HNSCCs17,18. Consistent with our results, accumulating evidence suggests that HPV-positive HNSCCs correlate with T cell-enriched TME, increased T cell receptor pathway signaling, activated cytotoxic capacity, and viral antigen-specific CD8+ T cell infiltration into the TME19–21. Additionally, we observed a significant increase in B cell subsets and plasma cells in HPV-positive tumors but not in HPV-negative tumors. Although the significance of B cell infiltration in the TME is not well understood, recent studies have reported the anti-tumor activity of B cells and plasma cells through antigen presentation and antibody production22. A recent study reported the presence of HPV-specific antibody-secreting cells in the TME of HPV-positive tumors23. Moreover, Kim et al. have reported that B cells correlate with longer OS and are activated by radiation and PD-1 blockade therapy24. These findings suggest the potential of B-cell-targeted immunotherapy. Further investigations regarding the specific roles of B cells and plasma cells in the TME are warranted.

Herein, non-supervised clustering of HNSCC cases based on the cell enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types revealed three immune signatures: cold, lymphocyte, and myeloid/DC. The lymphocyte signature correlated with the HPV-positive type, early T factor, positive N factor, and favorable prognosis in the TCGA cohort. Notably, the presence of T cell subsets has been widely investigated in several malignancies25–29. In HNSCC, the presence of TILs in the TME is reportedly considered a favorable prognostic factor30,31. Moreover, Tsujikawa et al. have previously assessed immune cell complexity profiles of 38 HNSCC cases using multiplex immunohistochemistry32. They acquired cell densities of 15 immune cell lineages using image cytometry, followed by normalization and unsupervised hierarchical clustering. Their analysis revealed three immune signatures: lymphoid-inflamed, myeloid-inflamed, and hypo-inflamed. The myeloid-inflamed signature exhibited significantly shorter OS. In addition, the lymphoid-inflamed signature consisted of more HPV-positive HNSCCs than the other signatures. Surprisingly, the results of the present study are consistent with those of their protein expression-based analysis. Although bulk RNA sequencing cannot evaluate the localization of each immune cell in the TME, our results suggest that bulk RNA sequencing-based molecular profiling has the potential to comprehensively profile immune cell complexity of the TME in combination with protein expression-based profiling, such as multiplex IHC. In addition to Tsujikawa’s work, our results of the TCGA cohort revealed that the myeloid/DC signature dramatically correlates with shorter OS in HPV-positive HNSCCs but not in HPV-negative cases. HPV-positive HNSCCs are widely recognized to exhibit a better prognosis than HPV-negative HNSCCs33,34. However, in clinical settings, some HPV-positive HNSCCs present aggressive behavior, resulting in a poor prognosis. Therefore, biomarkers that indicate the aggressive phenotype of HPV-positive HNSCCs are needed. The screening for myeloid-enriched TME has the potential to predict survival and allow precision medicine in HPV-positive HNSCCs.

We further focused on the transcriptomic significance of immune signatures. GSEA revealed the upregulation of multiple pathways related to inflammatory and proinflammatory responses, as well as the downregulation of pathways closely related to cancer hallmarks in the lymphocyte signature, as shown in Fig. 3b and Suppl. Fig. 5a. The upregulation of IFN-α responses, IFN-γ, and IL2 STAT5 signaling represents activated CTL responses, consistent with the presence of abundant lymphocytes. Furthermore, the lymphocyte signature showed the highest expression of both cytotoxic response-related genes PRF1, IFNG, GZMB, CXCL9, and CXCL10, and immune checkpoint genes PDCD1, LAG3, CTLA4, HAVCR2, and TIGIT. As these immune checkpoint molecules reportedly function as receptors for T cell inactivation and exhaustion signals, these molecules are abundantly expressed on effector memory T cells and tissue-resident memory T cells, which are activated phenotypes of T cells35–38. Accordingly, PD-1-expressing TILs are reportedly considered a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-positive HNSCCs39. Overall, the lymphocyte signature represented the enrichment of lymphocyte infiltration, activation of CTL functions, and favorable prognosis. As the cost of RNA sequencing has recently decreased, molecular profiling of the immune microenvironment using biopsy tissues may provide an alternative for the initial diagnosis of HNSCCs. However, in bulk RNA sequencing, the localization of immune cells cannot be determined. Dual profiling using both molecular and protein-based profiling would be helpful in comprehensively profiling the complexity of the immune milieu of the TME.

In conclusion, the present study revealed the transcriptomic landscape of the immune microenvironment that closely reflects the clinical and biological significance of HNSCC. Our results suggest that molecular profiling of the immune microenvironment can be employed for developing new biomarkers and precision immunotherapies for HNSCC.

Materials and methods

Acquisition of the cancer genome atlas (TCGA) data

RNA-seq data (Illumina Hiseq RNAseq V2, raw counts, and normalized counts) and clinical data were obtained from TCGA Research Network (TCGA Provisional version updated in 2016, http://cancergenome.nih.gov/). In total, 564 cases, consisting of 44 normal samples, 97 HPV-positive HNSCCs, and 423 HPV-negative HNSCCs, were included. Alternatively, GSE65858 dataset, including microarray data (Illumina HumanHT-12 V4.0 expression beadchip platform) and clinical data, were obtained from the Gene Expression Omnibus (GEO) database. In total, 270 cases, consisting of 73 HPV-positive HNSCCs, 196 HPV-negative HNSCCs, and 1 HPV-unknown HNSCC were included.

Cell type enrichment analysis

We performed cell type enrichment analysis to evaluate the enrichment of 33 immune cell types in both TCGA dataset and GSE65858 dataset using the xCell tool40. Enrichment scores were calculated using the xCell R package, version 1.1.0. The calculated scores were visualized using the pheatmap R package, version 1.10.12. Then, normal and HNSCC tissue scores were compared.

Non-supervised hierarchical clustering of HNSCC samples

HNSCC cases underwent non-supervised hierarchical clustering based on cell enrichment scores of 33 immune cell types. Patients were then divided into three immune signatures—cold, lymphocyte, and myeloid/DC—using the cutree R function based on the clustering results. The three signatures were compared in terms of clinical parameters, including HPV status, primary lesion, T factor, N factor, M factor, TNM stage, DFS, and OS. The three immune signatures were also compared to the normalized gene expression of various immune-related genes.

Differentially expressed gene analysis

In the TCGA cohort, we identified DEGs between the lymphocyte signature group and other signature groups, using the ExperimentHub R package version 1.16.0 and DESeq2 R package version 1.30.0. DEGs were filtered using the threshold |log2FC|≥ 1 and an adjusted p value of < 0.05. Volcano plots were constructed to visualize DEGs using the calibration R package version 1.7.7.

Gene set enrichment analysis

GSEA (GSEA v4, Broad Institute) was performed to identify pathways upregulated in the lymphocyte group when compared with other groups. For each gene set, the normalized enrichment score, p value, and false discovery rate (FDR) q-values were calculated based on the Hallmark pathway database.

Statistical analysis

Data were analyzed using R (version 4.0.3; The R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria) in combination with R studio version 1.3.1093 (R studio, Boston, MA, USA) and GraphPad Prism version 8 (GraphPad Software, San Diego, CA, USA). Student’s t-test and one-way ANOVA with Tukey’s post-hoc test for multiple pairwise testing were employed to compare continuous variables between groups. The Chi-square test for independence and Fisher’s exact test were used for comparing categorical variables. Two-sided p values of < 0.05 were considered statistically significant. Survival curves were calculated using the Kaplan–Meier method and compared using the log-rank test. Multivariate regression analysis was performed using the Cox proportional hazards model. Variables were included in subsequent multivariate analyses when p values were < 0.05 in univariate analyses.

Supplementary Information

Acknowledgements

This work was supported in part by a Grant-in-Aid for Scientific Research (B) 20H03834 (KC), Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists 19K18758 (IM), and Grant-in-Aid for Early-Career Scientists 20K18243 (HT) from the Ministry of Education, Culture, Sports, Science and Technology, Japan. We would like to thank Dr. Yuki Saito and Dr. Koji Ebisumoto for teaching TCGA dataset manipulation, and Dr. Kuniaki Sato for teaching GEO dataset manipulation.

Author contributions

I.M., investigation, software, formal analysis, funding acquisition, writing—initial draft preparation; H.T., conceptualization, methodology, validation, resources, project administration, funding acquisition, writing—review and editing; R.K., methodology, resources, writing—review and editing, visualization; S.I., software, formal analysis; H.T., software, formal analysis; K.C., writing—review and editing, supervision, funding acquisition.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41598-021-95718-9.

References

- 1.Ferlay J, et al. Estimating the global cancer incidence and mortality in 2018: GLOBOCAN sources and methods. Int. J. Cancer. 2019;144:1941–1953. doi: 10.1002/ijc.31937. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bray F, et al. Global cancer statistics 2018: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J. Clin. 2018;68:394–424. doi: 10.3322/caac.21492. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hashibe M, et al. Alcohol drinking in never users of tobacco, cigarette smoking in never drinkers, and the risk of head and neck cancer: Pooled analysis in the International Head and Neck Cancer Epidemiology Consortium. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2007;99:777–789. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djk179. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Mehanna H, et al. Prevalence of human papillomavirus in oropharyngeal and nonoropharyngeal head and neck cancer–systematic review and meta-analysis of trends by time and region. Head Neck. 2013;35:747–755. doi: 10.1002/hed.22015. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Couzin-Frankel J. Breakthrough of the year 2013. Cancer immunotherapy. Science. 2013;342:1432–1433. doi: 10.1126/science.342.6165.1432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ferris RL, et al. Nivolumab for recurrent squamous-cell carcinoma of the head and neck. N. Engl. J. Med. 2016;375:1856–1867. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1602252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Burtness B, et al. Pembrolizumab alone or with chemotherapy versus cetuximab with chemotherapy for recurrent or metastatic squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck (KEYNOTE-048): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 study. Lancet. 2019;394:1915–1928. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32591-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Topalian SL, et al. Safety, activity, and immune correlates of anti-PD-1 antibody in cancer. N. Engl. J. Med. 2012;366:2443–2454. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1200690. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Labani-Motlagh A, Ashja-Mahdavi M, Loskog A. The tumor microenvironment: A milieu hindering and obstructing antitumor immune responses. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:940. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.00940. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Joyce JA. Therapeutic targeting of the tumor microenvironment. Cancer Cell. 2005;7:513–520. doi: 10.1016/j.ccr.2005.05.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Partlová S, et al. Distinct patterns of intratumoral immune cell infiltrates in patients with HPV-associated compared to non-virally induced head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e965570. doi: 10.4161/21624011.2014.965570. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Mandal R, et al. The head and neck cancer immune landscape and its immunotherapeutic implications. JCI Insight. 2016;1:e89829. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.89829. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Tong CC, Kao J, Sikora AG. Recognizing and reversing the immunosuppressive tumor microenvironment of head and neck cancer. Immunol. Res. 2012;54:266–274. doi: 10.1007/s12026-012-8306-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Chen SMY, et al. Tumor immune microenvironment in head and neck cancers. Mol. Carcinog. 2020 doi: 10.1002/mc.23162. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wondergem NE, Nauta IH, Muijlwijk T, Leemans CR, van de Ven R. The immune microenvironment in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma: On subsets and subsites. Curr. Oncol. Rep. 2020;22:81. doi: 10.1007/s11912-020-00938-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Leemans CR, Snijders PJF, Brakenhoff RH, et al. The molecular landscape of head and neck cancer . Nat Rev Cancer . 2018;18:269–282. doi: 10.1038/nrc.2018.11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Principe N, et al. Tumor infiltrating effector memory antigen-specific CD8. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:584423. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.584423. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Liu Q, Sun Z, Chen L. Memory T cells: Strategies for optimizing tumor immunotherapy. Protein Cell. 2020;11:549–564. doi: 10.1007/s13238-020-00707-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lechien JR, et al. HPV involvement in the tumor microenvironment and immune treatment in head and neck squamous cell carcinomas. Cancers (Basel) 2020 doi: 10.3390/cancers12051060. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang J, et al. HPV-positive status associated with inflamed immune microenvironment and improved response to anti-PD-1 therapy in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Sci. Rep. 2019;9:13404. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-49771-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Krishna S, et al. Human papilloma virus specific immunogenicity and dysfunction of CD8. Cancer Res. 2018;78:6159–6170. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-18-0163. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Fridman WH, et al. B cells and cancer: To B or not to B? J. Exp. Med. 2021 doi: 10.1084/jem.20200851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wieland A, et al. Defining HPV-specific B cell responses in patients with head and neck cancer. Nature. 2020 doi: 10.1038/s41586-020-2931-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kim SS, et al. B cells improve overall survival in HPV-associated squamous cell carcinomas and are activated by radiation and PD-1 blockade. Clin. Cancer Res. 2020;26:3345–3359. doi: 10.1158/1078-0432.CCR-19-3211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Chen B, et al. Prognostic value of the common tumour-infiltrating lymphocyte subtypes for patients with non-small cell lung cancer: A meta-analysis. PLoS ONE. 2020;15:e0242173. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0242173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Maibach F, Sadozai H, Seyed Jafari SM, Hunger RE, Schenk M. Tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes and their prognostic value in cutaneous melanoma. Front. Immunol. 2020;11:2105. doi: 10.3389/fimmu.2020.02105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Gao G, Wang Z, Qu X, Zhang Z. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in patients with triple-negative breast cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Cancer. 2020;20:179. doi: 10.1186/s12885-020-6668-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kong JC, et al. Prognostic impact of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in primary and metastatic colorectal cancer: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Dis. Colon Rectum. 2019;62:498–508. doi: 10.1097/DCR.0000000000001332. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Geissler K, et al. Immune signature of tumor infiltrating immune cells in renal cancer. Oncoimmunology. 2015;4:e985082. doi: 10.4161/2162402X.2014.985082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.de Ruiter EJ, Ooft ML, Devriese LA, Willems SM. The prognostic role of tumor infiltrating T-lymphocytes in squamous cell carcinoma of the head and neck: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Oncoimmunology. 2017;6:e1356148. doi: 10.1080/2162402X.2017.1356148. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Spector ME, et al. Prognostic value of tumor-infiltrating lymphocytes in head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. JAMA Otolaryngol. Head Neck Surg. 2019 doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2427. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Tsujikawa T, et al. Quantitative multiplex immunohistochemistry reveals myeloid-inflamed tumor-immune complexity associated with poor prognosis. Cell Rep. 2017;19:203–217. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2017.03.037. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Johnson DE, et al. Head and neck squamous cell carcinoma. Nat. Rev. Dis. Primers. 2020;6:92. doi: 10.1038/s41572-020-00224-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Fakhry C, et al. Improved survival of patients with human papillomavirus-positive head and neck squamous cell carcinoma in a prospective clinical trial. J. Natl. Cancer Inst. 2008;100:261–269. doi: 10.1093/jnci/djn011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kansy BA, et al. PD-1 Status in CD8. Cancer Res. 2017;77:6353–6364. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-16-3167. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Clarke J, et al. Single-cell transcriptomic analysis of tissue-resident memory T cells in human lung cancer. J. Exp. Med. 2019;216:2128–2149. doi: 10.1084/jem.20190249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Savas P, et al. Single-cell profiling of breast cancer T cells reveals a tissue-resident memory subset associated with improved prognosis. Nat. Med. 2018;24:986–993. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0078-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Waki K, et al. PD-1 expression on peripheral blood T-cell subsets correlates with prognosis in non-small cell lung cancer. Cancer Sci. 2014;105:1229–1235. doi: 10.1111/cas.12502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Badoual C, et al. PD-1-expressing tumor-infiltrating T cells are a favorable prognostic biomarker in HPV-associated head and neck cancer. Cancer Res. 2013;73:128–138. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-12-2606. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Aran D, Hu Z, Butte AJ. xCell: Digitally portraying the tissue cellular heterogeneity landscape. Genome Biol. 2017;18:220. doi: 10.1186/s13059-017-1349-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.