Abstract

Infographics (visualizations that present information) can assist clinicians to offer health information to patients with low health literacy in an accessible format. In response, we developed an infographic intervention to enhance clinical, HIV-related communication. This study reports on its feasibility and acceptability at a clinical setting in the Dominican Republic. We conducted in-depth interviews with physicians who administered the intervention and patients who received it. We conducted audio-recorded interviews in Spanish using semi-structured interview guides. Recordings were professionally transcribed verbatim then analyzed using descriptive content analysis. Physician transcripts were deductively coded according to constructs of Bowen et al.’s feasibility framework and patient transcripts were inductively coded. Three physicians and 26 patients participated. Feasibility constructs endorsed by physicians indicated that infographics were easy to use, improved teaching, and could easily be incorporated into their workflow. Coding of patient transcripts identified four categories that indicated the intervention was acceptable and useful, offered feedback regarding effective clinical communication, and recommended improvements to infographics. Taken together, these data indicate our intervention was a feasible and acceptable way to provide clinical, HIV-related information and provide important recommendations for future visualization design as well as effective clinical communication with similar patient populations.

Keywords: Information visualization, clinician-patient communication, patient education, feasibility, nursing informatics

Introduction

Infographics (visualizations that present information) are increasingly used in healthcare to convey complex information in simple, culturally appropriate ways (Bakken et al., 2019; McCrorie et al., 2016). To maximize benefits, infographics have been developed to enhance understanding of risk (Ancker et al., 2006; Garcia-Retamero et al., 2012; Yang, 2020), print materials (Dowse et al., 2014; Gebreyohannes et al., 2019; Monroe et al., 2018), and outcome measures (Bantug et al., 2016; Stonbraker et al., 2020; Turchioe et al., 2019). If, and to what extent, infographics promote clinical communication remains unknown.

Infographics may be particularly useful to convey information to individuals with chronic conditions in resource-constrained settings, such as the Dominican Republic (DR), where patients are more likely to have low health literacy, which contributes to worse health outcomes (Kasemsap, 2017; Mackey et al., 2016). To enhance providers’ ability to offer information persons living with HIV (PLWH) need for effective self-management, we developed an infographic intervention (Stonbraker, Halpern, et al., 2019). This study assessed its clinical feasibility and acceptability.

Materials and methods

Ethical approval

The Columbia University Irving Medical Center Institutional Review Board and the Consejo Nacional de Bioética en Salud ethical review committee (DR) approved this study.

Study setting

The study was conducted at Clínica de Familia La Romana (CFLR), a Dominican health clinic.

Infographic intervention

The intervention, detailed elsewhere (Stonbraker, Halpern, et al., 2019), has 15 laminated infographics (Figure 1) that contain priority HIV-related information (Stonbraker, Richards, et al., 2019) that interventionists use to support clinical conversations.

Figure 1.

Example of intervention infographic that provides tips to support medication adherence, translated to English for this report

Recruitment and training of interventionists

The clinic’s 5 eligible physicians (≥ 2 years in HIV care; offering routine visits to PLWH) were invited to participate and the first 2 who agreed were consented. “Interventionists” attended a training on how to integrate infographics into evidence-based clinical communication (Dawson-Rose et al., 2016).

Patient recruitment

During recruitment (Fall 2018), staff identified and referred eligible PLWH (adults ≥18 years, with a viral load ≥40 copies/mL at any point in the prior year) to the study. Research Assistants obtained informed consent and administered questionnaires, which included the Short Assessment of Health Literacy in Spanish and English (Lee et al., 2010), among other measures.

Longitudinal study

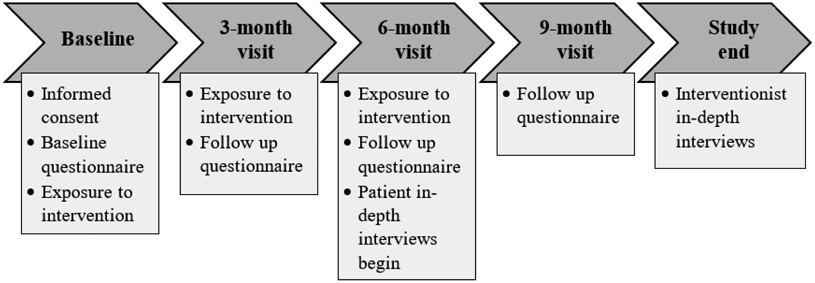

Interviews for this study were part of a longitudinal study (Figure 2), described in detail elsewhere.

Figure 2.

Summary of study procedures in the longitudinal study

In-depth interviews

Qualitative Descriptive methodology, a naturalistic approach to understanding poorly understood phenomena by eliciting in-depth descriptions of lived experiences (Colorafi & Evans, 2016; Sandelowski, 2000), guided interviews. SS conducted audio-recorded interviews in Spanish using iteratively developed semi-structured interview guides (Kallio et al., 2016) to explore clinical communication and infographic use (e.g., Did infographics help you communicate with your doctor?). Interventionist interviews confirmed/disconfirmed support for the following constructs of Bowen’s framework to inform feasibility studies (Bowen et al., 2009): acceptability, demand, implementation, practicality, integration, and expansion. Adaptation and limited efficacy - constructs pertaining to future study phases - were omitted. All participants were asked for recommendations to improve infographics.

Data analysis

Two bilingual coders (SS and GF) completed analyses in Spanish using NVivo software (QSR International, 2020). They generated deductive codes to analyze interventionist transcripts by operationalizing Bowen’s framework (Bowen et al., 2009). To analyze patient transcripts, coders inductively generated codes around any text that conveyed meaning. Initially, coders separately coded two transcripts. They then reconciled discrepancies and organized codes into a codebook, then separately coded 5 more transcripts, adding codes as needed. Analysis continued this way until coders analyzed all transcripts. Coders grouped final codes by relevance until categories emerged. SS selected and translated quotes reflective of main findings; GF verified selections and translations.

Strategies to enhance rigor

Numerous strategies addressed main components of qualitative rigor (Guba, 1981). Reviewing emerging findings with participants and study team helped assure credibility; thorough description of participants and exemplar quotes demonstrated data richness and provided context to enable transferability; the use of a codebook addressed data dependability; and audit trails enhanced confirmability (Guba, 1981; Thomas & Magilvy, 2011).

Results

Demographics

The 3 interventionists (one interventionist withdrew before study completion and was replaced) had a mean age of 26.7 years (range 25-30), were female and Dominican. Among patient participants (n=26), the mean age was 42.5 years (range 29-65), 25 (96%) were Dominican, 13 (50%) were female, and they had been living with HIV for a mean of 6.4 years (range 2 weeks – 23 years) at enrollment. Two (8%) had no formal education, 10 (37%) had some/all of primary school, 12 (46%) had some/all of high school, and 2 (8%) had completed some school beyond high school; based on SAHL S&E scores, 9 (35%) were likely have adequate health literacy.

Support for Bowen’s framework

Interventionists provided evidence for intervention feasibility and acceptability through their responses to each of the examined constructs (Table 1).

Table 1.

Summary of interventionists’ perspectives regarding the feasibility of using infographics during clinic visits to enhance clinician-patient communication according to Bowen’s feasibility framework (Bowen et al., 2009).

| Feasibility construct |

Definition | Main findings and corresponding quotes from interventionists |

|---|---|---|

| Acceptability | How the individuals involved with the intervention (both those administering and receiving it) respond to it. | “I like that it [infographic intervention] is a visual medium so that patients can understand about medication, how to take their medication, the side effects, and other things we discuss in a clinic visit.” “For me, using the infographics with new patients, really new who just received the diagnosis, is excellent. And, for the patients who are illiterate, who don’t have any knowledge of writing and letters, the infographics are excellent to show them how to manage their medications and how to take them.” “Yes, [I want to continue using the infographics] I even told them in a meeting that it could be in the future that all of the doctors, especially those working with patients who are newly diagnosed, are able to use the infographics.” |

| Demand | The extent to which the intervention is used, and how it is used among a specific population. | “With the infographics, they [patients] are much more attentive, because they are looking at what you are saying…. Or, they are not on their phone. Because, sadly, many patients these days, when you are speaking to them during a clinic visit, they are on their phone. At least, when you have the infographics, you maintain their attention because they have to look at what you are saying.” “[I liked] that I could interact more with the patient [using infographics] and I could, you know, say to them ‘what color are you seeing?’ as if the patient was more trusting when you ask them, ‘what are you seeing?’ or, ‘what do you not understand of what I am saying?’, like that, [infographics] lead to more communication with the patient.” “In ‘consejería’ (area for sexually transmitted infection counseling), they should really use the infographics, also in adherence counseling.” |

| Implementation | Evidence that the intervention can be implemented as intended. | “Yes, you can interact with the infographics without it taking us [doctors] more time. What happens is that it depends how you explain things to the patient that you want them to understand. It is the same as if I grab a pen and paper and I write, ‘you are going to take your medication at night or you are going to take it in the day.’ Instead of starting to write, I am going to take the infographics and I am going to say, ‘look, you are going to take your medication at this time with breakfast or with dinner.’” “Yes, [one difficulty with the infographics] were some patients, for example, who didn’t understand with the images, without the images, not with words, anything that we explained to them.” “I don’t think so [the clinic has to do anything to implement infographics], they just have to train people to use them.” |

| Practicality | The extent to which an intervention can be delivered in a real-world setting (i.e. when time or resources are somehow limited). | “With the infographics, well, I save a lot of time not having to draw things or explaining things with paper and pencil, because I had the images. For me they are excellent, they are excellent because truthfully, it is really something we can work with.” “Well, I communicated better with the patients [when using infographics]. They understood me after I had talked to them about what HIV is, presented to them how to take their medications. It was better communication with the patients. Even more so with the foreign patients, as we had a few.” “I found [the effect on patients] was more positive than negative. They understood better. For example, they understood the difference between CD4 and viral load, where one should be and where the other should be.” |

| Integration | Considers the level of system change required to fully incorporate an intervention or program into the existing one. | “No, [it was not extra work] because at once we started talking to the patient and showing them [the infographics]. No, it’s that a person is not the same when they arrive [with a new diagnosis]. When you see a new patient, you have to take your time, you have to take your time with the patient and answer their questions.” “I think more or less everyone is going to want to use them [infographics] because it is what I am telling you, at the time of us explaining, for example, to a new patient what is CD4 and what is viral load and you have an image, it is going to help us.” “In reality, it is not that much [to implement the intervention], it is simply show the infographics so that everyone [anyone who will use them], explain to them infographic by infographic, what it is that we want them to do with each, and what we want the patient to understand with each infographic.” |

| Expansion | The extent to which the intervention can be expanded beyond the level of the initial study, including to other populations, and settings. | “No, I don’t think [the clinic has to do] anything [to expand the intervention]. Simply train the personnel so that they know what they are going to do with the infographics.” “Yes, [you could use the infographics] in other healthcare centers, of course you could. That would be excellent.” “Yes, [you could use the infographics outside the context of the study], it could be very useful.” |

Note: The adaptation and limited efficacy constructs of Bowen’s recommendations were omitted because they pertain to planned future study phases.

Suggestions to improve infographics

Interventionists indicated infographics should be larger and include thoughtfully selected, brighter colors. For example, “put in the color of happiness, like a rainbow.” Other suggestions included having infographics be tailorable to individual patients, available electronically and for widespread use, including for other health conditions such as diabetes.

Inductive findings

Four main categories emerged from patient transcripts:

1. Benefits of infographics

Participants found infographics beneficial because they enhanced learning/understanding, encouraged medication adherence, and were myth-busting. As one said, “[infographics] taught me what you can and cannot do. There are people that believe if I greet you and give you my hand, I can infect you. They [infographics] taught me that I can greet a person, use the same towel, the same bathroom, and not infect others.”

2. Suggestions to improve infographic designs and clinical use

Participants recommended keeping designs simple, using brighter/bolder colors, and adding more text. Participants also suggested more frequent use, because “if there is follow up, one learns. When they [clinicians] do not follow up and think, ‘no, I already said this and you already know it,’ it could be that I know it, but it could also be when you told me, I had my mind on something else.” Participants recommended expanding use by making infographics digital, posting them in high-traffic areas, having them widely available in the clinic, and similar to physicians, available for other health conditions.”

3. Infographic effect on communication

Overall, participants thought infographics helped with communication. Some simply stated, “yes they help.” Others offered more complete explanations, such as, “yes, [infographics help with communication] because the more you see the images, there are things you don’t know, so they call your attention, which brings communication with the doctor because questions come up.”

4. Characteristics of effective communication

Participants asserted physicians should be trustworthy and “treat people well” by showing respect, interest in patients beyond their condition, having empathy, and being nice. Suggestions to improve communication included using infographics, taking sufficient time for explanations, thoroughly covering important topics, being patient, listening carefully, and confirming understanding. One participant said, “there are people that won’t understand, but they are going to tell you they understood. In that situation, you need to interact with them. Tell them, ‘explain to me why this is or what did you understand?’ like a quiz.” Some opinions of effective communication were contradictory. For example, “my doctor was reprimanding me and that motivates me… these are the doctors that help you, they motivate you to keep going.” Others indicated this type of treatment is not ideal. Additionally, several participants indicated communication should be honest and direct. For example, “we Dominicans think like this, we look for direct communication, it makes it easier to convince a person [to do something].” While some preferred softer communication.

Discussion

Our study provides evidence that integrating HIV-related infographics into clinic visits is feasible and acceptable. Findings contribute to the literature on effective infographic design and clinical communication with Latino patients.

Consistent with existing recommendations, participants advocated larger infographics with bright/bold colors representing specific meanings, as color may enhance understandability and cultural appropriateness, especially among Latinos (Katz et al., 2006; Mohan et al., 2013; Stonbraker, Halpern, et al., 2019). Additionally, participants would like infographics for other health conditions, which is an area for future research.

Participants confirmed the utility of several recommended communication strategies (that providers take their time and confirm understanding, etc.) (Lettenmaier et al., 2014); and contributed that infographics can promote clinical communication. Notably, patients want trustworthy providers who treat them well, which should be a given, but too frequently does not occur (Dawson-Rose et al., 2016). Participants’ contradictory opinions of preferred communication styles reiterates that tailoring communication to individuals would augment efficacy. Numerous strategies to help providers communicate are available for widespread use (Berkhof et al., 2011; Elder et al., 2009). Lastly, that our patients and providers shared a common culture emphasizes thoughtful and intentional communication is crucial whether cultural differences are present or not.

This study had limitations. Interventionists were young, female, and volunteered to participate, which limits generalizability. Social desirability bias, common among Latinos (Hopwood et al., 2009), may have augmented positive responses. Regardless, participants indicated the intervention is a feasible and acceptable way to support communication. Future work will include expanding infographics to other conditions and automating them to improve accessibility.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to extend a special thank you to our participants, without whom this work would not have been possible. Also, we would like to thank Ynaliza González, who closely collaborated with us as a Research Assistant throughout the study. Her hard work and dedication to this research was a tremendous asset to our team. The research reported in this publication and the first author were supported by the National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research under Award Number K99NR017829. The mentorship of RS was supported by National Institutes of Health/National Institute of Nursing Research under Award Number K24NR018621. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Footnotes

Declaration of interest

None.

References

- Ancker JS, Senathirajah Y, Kukafka R, & Starren JB (2006). Design features of graphs in health risk communication: A systematic review. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 13(6), 608–618. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bakken S, Arcia A, & Woollen J (2019). Promoting Latino self-management through use of information visualizations: A case study in New York City. Information Services & Use, 39(1-2), 51–58. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bantug ET, Coles T, Smith KC, Snyder CF, Rouette J, & Brundage MD (2016). Graphical displays of patient-reported outcomes (PRO) for use in clinical practice: What makes a pro picture worth a thousand words? Patient Education and Counseling, 99(4), 483–490. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berkhof M, van Rijssen HJ, Schellart AJ, Anema JR, & van der Beek AJ (2011). Effective training strategies for teaching communication skills to physicians: an overview of systematic reviews. Patient Education and Counseling, 84(2), 152–162. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bowen DJ, Kreuter M, Spring B, Cofta-Woerpel L, Linnan L, Weiner D, Bakken S, Kaplan CP, Squiers L, & Fabrizio C (2009). How we design feasibility studies. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 36(5), 452–457. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Colorafi KJ, & Evans B (2016). Qualitative descriptive methods in health science research. HERD: Health Environments Research & Design Journal, 9(4), 16–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dawson-Rose C, Cuca YP, Webel AR, Solís Báez SS, Holzemer WL, Rivero-Méndez M, Sanzero Eller L, Reid P, Johnson MO, Kemppainen J, Reyes D, Nokes K, Nicholas PK, Matshediso E, Mogobe KD, Sabone MB, Ntsayagae EI, Shaibu S, Corless IB, Wantland D, & Lindgren T (2016). Building Trust and Relationships Between Patients and Providers: An Essential Complement to Health Literacy in HIV Care. Journal of the Association of Nurses in AIDS Care, 27(5), 574–584. 10.1016/j.jana.2016.03.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dowse R, Barford K-L, & Browne SH (2014). Simple, illustrated medicines information improves ARV knowledge and patient self-efficacy in limited literacy South African HIV patients. AIDS Care, 26(11), 1400–1406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elder JP, Ayala GX, Parra-Medina D, & Talavera GA (2009). Health communication in the Latino community: issues and approaches. Annual review of public health, 30, 227–251. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Retamero R, Okan Y, & Cokely ET (2012). Using visual aids to improve communication of risks about health: a review. The Scientific World Journal, 2012, 1–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gebreyohannes EA, Bhagavathula AS, Abegaz TM, Abebe TB, Belachew SA, Tegegn HG, & Mansoor SM (2019). The effectiveness of pictogram intervention in the identification and reporting of adverse drug reactions in naïve HIV patients in ethiopia: a cross-sectional study. HIV/AIDS (Auckland, NZ), 11, 9–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Guba EG (1981). Criteria for assessing the trustworthiness of naturalistic inquiries. Ectj, 29(2), 75–91. [Google Scholar]

- Hopwood C, Flato C, Ambwani S, Garland B, & Morey L (2009). A comparison of Latino and Anglo socially desirable responding. Journal of clinical psychology, 65(7), 769–780. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kallio H, Pietilä AM, Johnson M, & Kangasniemi M (2016). Systematic methodological review: developing a framework for a qualitative semi‐structured interview guide. Journal of Advanced Nursing, 72(12), 2954–2965. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kasemsap K (2017). Promoting health literacy in global health care (Handbook of research on healthcare administration and management (pp. 485–506). IGI Global. [Google Scholar]

- Katz MG, Kripalani S, & Weiss BD (2006). Use of pictorial aids in medication instructions: a review of the literature. American journal of health-system pharmacy, 63(23), 2391–2397. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee S, Stucky B, Lee J, Rozier R, & Bender D (2010). Short assessment of health literacy-spanish and english: a comparable test of health literacy for Spanish and English speakers. Health Services Research, 45(4), 1105–1120. 10.1111/j.1475-6773.2010.01119.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lettenmaier C, Kraft JM, Raisanen K, & Serlemitsos E (2014). HIV communication capacity strengthening: a critical review. JAIDS, Journal of Acquired Immune Deficiency Syndromes, 66, S300–S305. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mackey LM, Doody C, Werner EL, & Fullen B (2016). Self-Management Skills in Chronic Disease Management What Role Does Health Literacy Have? Medical Decision Making, 36(6), 741–759. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- McCrorie A, Donnelly C, & McGlade K (2016). Infographics: healthcare communication for the digital age. The Ulster medical journal, 85(2), 71–75. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohan AV, Riley MB, Boyington DR, & Kripalani S (2013). Illustrated medication instructions as a strategy to improve medication management among Latinos: a qualitative analysis. Journal of health psychology, 18(2), 187–197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Monroe A, Pena J, Moore RD, Riekert K, Eakin M, Kripalani S, & Chander G (2018). Randomized controlled trial of a pictorial aid intervention for medication adherence among HIV-positive patients with comorbid diabetes or hypertension. AIDS Care, 30(2), 199–206. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- QSR International (2020). NVivo (released in March 2020). https://www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- Sandelowski M (2000). Focus on research methods-whatever happened to qualitative description? Research in nursing and health, 23(4), 334–340. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonbraker S, Halpern M, Bakken S, & Schnall R (2019). Special Section on Visual Analytics in Healthcare: Developing infographics to facilitate HIV-related patient-provider communication in a limited-resource setting. Applied clinical informatics, 10(4), 597–609. 10.1055/s-0039-1694001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonbraker S, Porras T, & Schnall R (2020). Patient preferences for visualization of longitudinal patient-reported outcomes data. Journal of the American Medical Informatics Association, 27(2), 212–224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stonbraker S, Richards SD, Halpern M, Bakken S, & Schnall R (2019). Priority topics for health education to support HIV self-management in limited-resource settings. Journal of Nursing Scholarship, 51(2), 168–177. 10.1111/jnu.12448 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thomas E, & Magilvy JK (2011). Qualitative rigor or research validity in qualitative research. Journal for specialists in pediatric nursing, 16(2), 151–155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Turchioe MR, Myers A, Isaac S, Baik D, Grossman LV, Ancker JS, & Creber RM (2019). A Systematic Review of Patient-Facing Visualizations of Personal Health Data. Applied clinical informatics, 10(4), 751–770. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yang F (2020). Data Visualization for Health and Risk Communication. In O'Hair DH, O'Hair MJ, Hester EB, & Geegan S (Eds.), The Handbook of Applied Communication Research (pp. 213–232). John Wiley & Sons, Inc. 10.1002/9781119399926.ch13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]